Abstract

The present study used data from the American Trends Panel to examine the interplay between the perceived COVID-19 health threat, discriminatory beliefs in medical settings, and psychological distress among Black Americans. We measured psychological distress as an average of five items modified from two established scales and used self-reports of perceived COVID-19 health threat and beliefs about discrimination in medical settings as focal predictors. Ordinary least squares regression was used to examine these relationships. Holding all else constant, we found that perceived COVID-19 health threat and the belief that Black Americans face racial discrimination in medical settings were both positively and significantly associated with higher levels of psychological distress. We also found a significant perceived COVID-19 health threat by belief about discrimination in medical settings interaction in the full model. Future studies should assess how these relationships vary across age groups and over time.

Keywords: Mental health, perceived coronavirus threat, COVID-19, perceived discrimination, sociology of Blacks, discrimination beliefs

The coronavirus outbreak represents a significant social problem in the United States (U.S.). Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that the coronavirus outbreak is responsible for more than nineteen million infections and over 330,000 deaths in the U.S. (CDC COVID Data Tracker n.d.) Research also suggests that the burden of the coronavirus outbreak is unequally distributed across society, as Black Americans face a higher risk of contracting and dying from coronavirus, and are at greater risk of knowing someone who has been hospitalized or died from the coronavirus than non-Black Americans (Kramer and Kramer 2020; Yancy 2020). Not surprisingly, several scholars have argued that the coronavirus outbreak represents a stressful event for Black Americans, leading to mental health problems (Novacek et al. 2020). Given that psychological distress is also a risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality, issues related to the coronavirus outbreak are likely to remain a visible public health concern among Black Americans well into the future.

Scholars of ethnoracial health disparities devote considerable attention to theorizing the mental health implications of the coronavirus outbreak among Black Americans. For example, drawing from critical race theory (CRT) and the stress process model, Laster Pirtle (2020) contends that Black Americans reside in a racist and capitalist society that creates and sustains within-group health disparities through the unequal distribution of perceived threats and social resources. Over time, repeated exposure to racism and other perceived threats overwhelm one’s personal resources, which in turn leads to poorer health. A long tradition of research has examined ethnoracial disparities in perceived threats and shown that Black Americans face greater exposure to interpersonal racism, discrimination, and other perceived threats than their White counterparts (Pratt 2009). Not surprisingly, scholars in this area have both developed measures of stress exposure related to the coronavirus outbreak (Conway, Woodard, and Zubrod 2020) and also find that a greater proportion of Black Americans believe the coronavirus outbreak to be a “major threat” to one’s health relative to non-Black Americans (Pew Research Center 2020). Though important, we are not aware of any published study that examines how a perceived COVID-19 health threat influences mental health among Black Americans. This absence is curious, given the importance of perceived threats in shaping Black Americans’ mental health inequalities (Jackson et al. 2011). This neglect also occurs despite recent evidence that Black Americans are disproportionally affected by the coronavirus outbreak (Egede and Walker 2020).

There are grounds for contending that beliefs regarding racial discrimination are associated with psychological distress among Black Americans and may moderate the possible relationship between perceived COVID-19 health threat and psychological distress. First, CRT scholars have long claimed that racial bias in the healthcare system manifests in clinicians’ opinions, beliefs, behaviours, and attitudes, significantly and disproportionately disadvantage Black Americans (Feagin and Bennefield 2014; Gengler and Jarrell 2015). For instance, research demonstrates that White clinicians hold negative implicit biases towards Black patients (Stepanikova 2012), which “can influence providers’ beliefs about and expectations of patients, independent of other factors” (van Ryn et al. 2006, 497). At the same time, nearly three-quarters of Black Americans believe they encounter racial bias in clinical encounters to an extent or very often (Malat and Hamilton 2006). Second, a growing body of research examines how Black American’s beliefs about racial bias when seeking medical treatment influences their mental health (Chae et al. 2011). Given the high “prevalence” of discrimination in medical settings among Black Americans, anticipatory stress may emerge in the coronavirus pandemic context. As some Black Americans and their family members contract coronavirus, interactions with healthcare providers and the healthcare system become inevitable. Consequentially, when Black Americans enter these medical settings, the stress of potential unfair treatment may induce psychological distress. Moreover, for Black Americans who perceive coronavirus as a threat to their health, discriminatory treatment could exacerbate distress levels.

The current study responds to ongoing calls to integrate CRT into mental health (Brown 2003; Assari and Habibzadeh 2020) by examining the interplay between perceived COVID-19 health threat, beliefs about racial discrimination in medical settings, and psychological distress among Black Americans.Though we are not the first to examine the interrelationships between stress exposure, beliefs about discrimination in medical settings, and mental health, there are critical differences between the present study and prior studies on this topic. First, this study relies on a within-group approach (e.g. differences in mental health among Black Americans based on psychosocial, demographic, and other factors) to illuminate the interplay between the perceived health threat of coronavirus outbreak, beliefs about discrimination in medical settings, and mental health among self-identified Black Americans (Whitfield et al. 2008). Second, we draw on a subsample of Black Americans from a nationally representative sample of adults, who were administered the survey shortly before and after the coronavirus occurred in the U.S. to examine these claims.

Based on prior research, we hypothesize that perceiving the COVID-19 outbreak as a threat to one’s health and believing Black Americans receive inferior treatment in medical settings can be independently associated with higher psychological distress levels. Considering prior research, we tested whether there would be a significant interaction between the perceived COVID-19 health threat and beliefs about racial discrimination in medical settings. We also hypothesized that Black Americans who report that the coronavirus outbreak represented a threat to their health and who believe that Black Americans face worse treatment in medical settings than White Americans would be associated with higher psychological distress levels than Black Americans who do not.

Data

The data examined was derived from the Pew Research Center (PRC)’s American Trends Panel (ATP), a probability-based online survey panel of non-institutionalized adults above the age of 17 in the U.S. Internet users participated in the panel via monthly self-administered web surveys. PRC provided a tablet and internet access to respondents who lacked internet access [for more information regarding ATP, see Additional information on ATP’s construction can be found here: https://www.pewresearch.org/methods/u-s-survey-research/american-trends-panel/]. Though ATP is primarily a public opinion survey, recent innovations render this an ideal dataset to address the current research questions. First, in Wave 43 (January 22–February 5, 2019), the PRC asked panelists to provide detailed answers regarding their views of race relations in the U.S. Second, the ATP included a battery of questions regarding the coronavirus outbreak in Wave 64. The PRC fielded this wave of the ATP shortly after the nation shut down in response to the coronavirus outbreak (March 19–24, 2020). To our knowledge, this is the only nationally representative dataset that covers responses regarding a perceived COVID-19 health threat, beliefs about racial discrimination in medical settings, and mental health among Black Americans. The current study drew on responses from a subsample of self-identified Black Americans from the Wave 43 who also participated in Wave 64 (n = 747) and had no missing values of interest (n = 652).

Dependent variable

Psychological distress

Our outcome, psychological distress, is a summary score based on five questionnaire items in Wave 64 that the ATP adapted from the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder scales. Specifically, the PRC asked ATP panelists how often, in the past seven days, they (1) felt nervous, anxious, or on edge; (2) felt depressed; (3) felt lonely; (4) had trouble sleeping; and (5) felt hopeful about the future. Original response items were placed on a scale that ranged from one (“rarely or none of the time”) to five (“most of the time”). The positive valanced item “felt hopeful about the future”) was reverse-coded and rescaled such that the responses ranged from zero (“rarely or none of the time”) to four (“most of the time”). Following this, we summed the items to produce a psychological distress score reflecting increasing levels of psychological distress within the past seven days (possible range: 0–20; Cronbach’s α = 0.69).

Independent variables

Perceived COVID-19 health threat

One of our focal predictors, perceived COVID-19 health threat, was derived from respondents’ answer to the following question during Wave 64: “How much of a threat, if any, is the coronavirus outbreak for your personal health?” Responses included “a major threat” (1), “minor threat” (2), and “not a threat” (3).

Beliefs about discrimination in medical settings

Beliefs about racial discrimination in medical settings were assessed in Wave 43 by asking respondents: “In general, in our country these days, would you say that Black people are treated less fairly than [W]hite people, [W]hite people are treated less fairly than Black people, or both are treated about equally when seeking medical treatment.” Given sample size issues, we created a dichotomous measure for this measure (1 = believe Black Americans are treated less fairly than Whites in medical settings, 0 = believe Black Americans are not treated less fairly than Whites in medical settings).

Control variables

Our study controlled for several factors included in Wave 43 that may influence the interplay between perceived COVID-19 health threat, beliefs about racial discrimination in medical settings, and psychological distress. Demographic factors include gender (1 = females, 0 = males), age (18–29 [base category], 30–49, 50–64, and 65 and above), and region of residence (Northeast, Midwest, South [reference group], and West). Economic indicators include degree attainment (high school graduate or less [reference group], some college, and college graduate), and household income ($75,000 and above, $30,000–$74,999, and less than $30,000 [reference group]). Our measure of politics includes party affiliation and political ideology. Party identification is a categorical variable that divides respondents into four groups (Democrat, Republican [reference group], Independent, and Something Else). At the same time, political ideology is an ordinal variable that ranges from “very conservative” (1) to “very liberal” (5).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive characteristics were summarized for the entire sample in Table 1. Given that our dependent variable is continuous, we used ordinary least squares regression. We presented the unstandardized beta coefficients, standard errors, and p-values obtained from these models in Table 2. To examine whether the possible relationship between perceived COVID-19 health threat and psychological distress varies according to beliefs about racial discrimination in medical settings, we also tested an interaction between perceived COVID-19 health threat and beliefs about racial discrimination in medical settings. Sampling weights and design factors were used to account for the survey’s complex study design, and we conducted all analyses in STATA 16.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics, American trends panel (N = 652).

| M/% | S.D. | Min | Max | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychological Distressa | 5.05 | 3.39 | 0 | 15 |

| Perceived COVID-19 health threatb | ||||

| A major threat | 48% | 0 | 1 | |

| A minor threat | 42% | 0 | 1 | |

| No threat at all | 10% | 0 | 1 | |

| Beliefs about Discrimination in Medical Settingsb | ||||

| Black Americans face worse treatment in medical settings than White Americans | 62% | 0 | 1 | |

| Black Americans face the same or better treatment in medical settings than White Americans | 38% | 0 | 1 | |

| Controls | ||||

| Age Groupingsb | ||||

| 18–29 | 15% | 0 | 1 | |

| 30–49 | 40% | 0 | 1 | |

| 50–64 | 34% | 0 | 1 | |

| 65+ | 12% | 0 | 1 | |

| Femaleb | 62% | 0 | 1 | |

| Regionb | ||||

| Northeast | 14% | 0 | 1 | |

| Midwest | 16% | 0 | 1 | |

| South | 61% | 0 | 1 | |

| West | 9% | 0 | 1 | |

| Degree Attainmentb | ||||

| College graduate+ | 29% | 0 | 1 | |

| Some College | 37% | 0 | 1 | |

| H.S. graduate or less | 34% | 0 | 1 | |

| Annual Household Incomeb | ||||

| $75,000 or more | 19% | 0 | 1 | |

| $30,000–$74,999 | 36% | 0 | 1 | |

| Less than $30,000 | 45% | 0 | 1 | |

| Politicsb | ||||

| Republican | 5% | 0 | 1 | |

| Democrat | 67% | 0 | 1 | |

| Independent | 22% | 0 | 1 | |

| Something Else | 6% | 0 | 1 | |

| Political Ideology | 3.11 | .86 | 1 | 5 |

Measured in Wave 64.

Measured in Wave 43.

Table 2.

Unstandardized beta coefficients from linear regression models predicting psychological distress among Black Americans, American Trends Panel (N = 652).

| Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Perceived COVID-19 health threat (Ref: Not a threat) | ||

| A major threat | 1.61*** (.42) | .24 (.68) |

| A minor threat | .37 (.40) | −1.17 (.63) |

| Beliefs about Discrimination in Medical Settings (Ref: White Americans face equal or worse treatment) | ||

| Black Americans face worse treatment in medical settings than Whites | .64* (.27) | −1.47* (.72) |

| Age Groupings (Ref: Age 18–29) | ||

| 30–49 | −.32 (.40) | −.38 (.40) |

| 50–64 | −.79 (.41) | −.89* (.41) |

| 65 and above | −1.83*** (.48) | −2.01*** (.48) |

| Female | .34 (.28) | .32 (.27) |

| Region (Ref: South) | ||

| Northeast | .68 (.40) | .69 (.39) |

| Midwest | .10 (.34) | .06 (.34) |

| West | −.04 (.46) | .02 (.47) |

| Degree Attainment (Ref: High School or less) | ||

| College Graduate | −1.11** (.38) | −1.11** (.37) |

| Some College | −.70 (.38) | −.70 (.38) |

| Annual Household Income (Ref: $0–$29,999) | ||

| $75,000 or more | −.94** (.36) | −.90* (.36) |

| $30,000–$74,999 | −.48 (.32) | −.44 (.32) |

| Politics (Ref: Republican) | ||

| Democrat | .58 (.59) | .70 (.57) |

| Independent | .23 (.63) | .29 (.61) |

| Something Else | .82 (.81) | .94 (.79) |

| Political Ideology | −.23 (.15) | −.22 (.15) |

| Interactions | ||

| Major threat × Black Americans face worse treatment in medical settings than Whites | 2.29** (.83) | |

| Minor threat × Black Americans face the same or worse treatment in medical settings than Whites | 2.51** (.79) | |

| Constant | 5.34*** (1.10) | 6.52*** (1.16) |

| R-squared | .14 | .15 |

Standard errors in parentheses,

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

Findings

Table 1 provides summary statistics for respondents in our study. The mean psychological distress score, measured in Wave 64, was 5.04 (standard deviation = 3.39). Nearly half of respondents (48%) viewed the coronavirus outbreak as a “major threat” to their health. In comparison, 42% viewed the coronavirus outbreak as “a minor threat,” and the remaining 10% regarded the coronavirus outbreak as “no threat at all” when asked in Wave 64. Sixty-two percent of respondents believe Black Americans face worse treatment in medical settings than Whites. Fifteen percent of our sample were between the ages of 18–29, while 40% were between 30 and 49, 34% between 50 and 64, and the remaining 12% were aged 65 and above. Sixty-two percent of our respondents are women, and 38% of our sample are men. Sixty-one percent of our responded resided in the South during Wave 43 of the ATP. Twenty-nine percent of respondents reported having at least a college degree in Wave 43. In comparison, 37% of respondents had some college education level, and 34% of respondents reported having a high-school degree or less in Wave 43. Nearly half of our respondents (45%) had an annual household income of less than $30,000 when asked in Wave 43. Most respondents were Democrats, and the mean political ideology score was 2.90 (standard deviation: .86) when asked in Wave 43.

The association between our focal predictors and the dependent variable is shown in Table 2, and findings from the survey-weighted multivariate linear regression models indicated that perceived COVID-19 health threat and beliefs about racial discrimination in medical settings were significantly associated with psychological distress scores. Specifically, holding all else constant, results from Model 1 suggest that respondents who perceived COVID-19 as a major threat to their health (unstandardized beta = 1.61, p < .001) reported higher psychological distress levels relative respondents who did not perceive COVID-19 as not a threat to their personal health. Interestingly, individuals who perceived coronavirus as a minor threat did not differ from those who perceived no threat. Believing Black Americans face worse treatment when seeking medical treatment than Whites (unstandardized beta = .64, p < .05) was significantly associated with higher psychological distress levels.

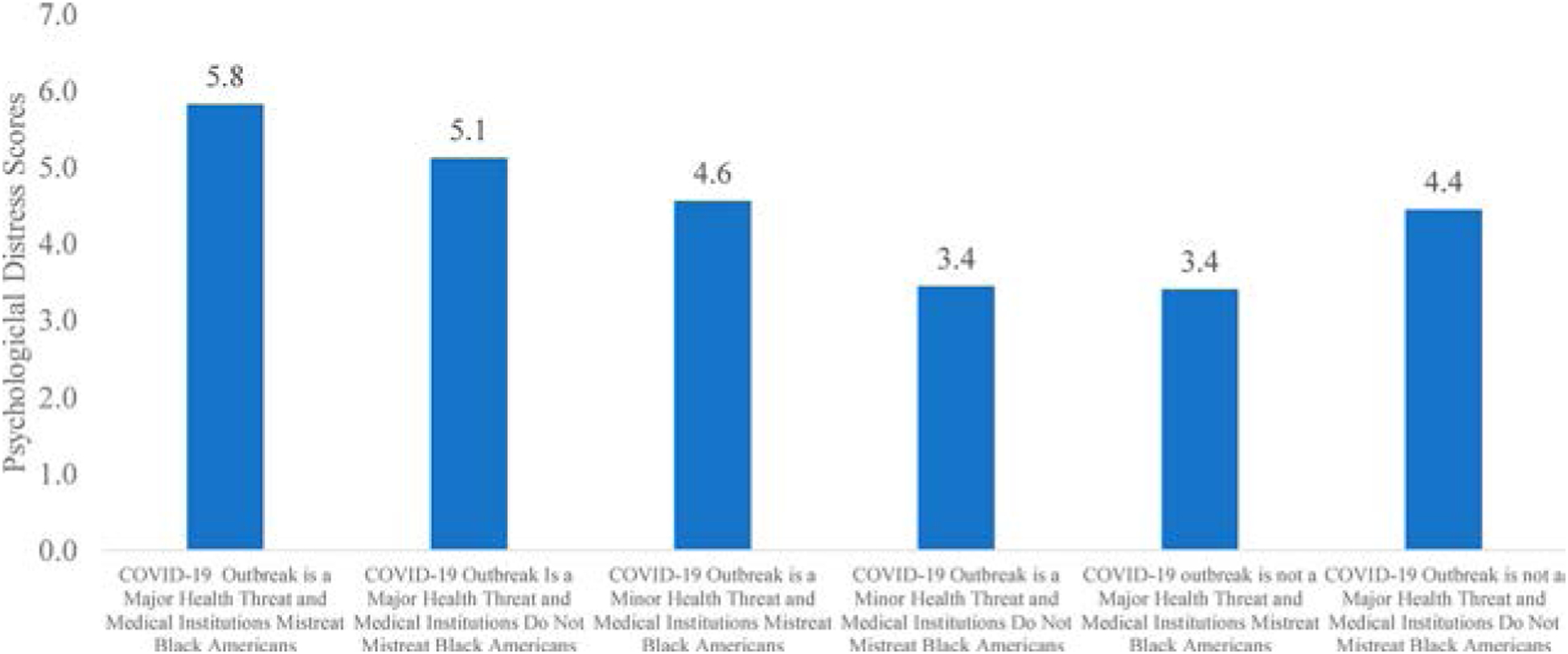

In Model 2, we used interaction terms to test whether beliefs about racial discrimination in medical settings moderated the association between perceived COVID-19 health threat and psychological distress. Results from these interaction terms revealed a significant conditional relationship between perceived COVID-19 health threat, beliefs about racial discrimination in medical settings, and psychological distress. Specifically, psychological distress levels were higher for respondents who reported that the COVID-19 outbreak represented a major (unstandardized beta = 2.29, p < .01) or minor threat (unstandardized beta = 2.51, p < .001) to their health and believed that Black Americans were treated poorly than Whites when seeking medical treatment relative to those who did not.

Figure 1 provides a visual depiction of the statistical interactions. Respondents who reported coronavirus as a major threat and believed in discrimination against Black Americans in medical settings experienced the highest distress (Mean: 5.8) followed by the major threat and no discrimination in medical settings respondents (Mean: 5.1). Furthermore, 30% of respondents perceived both a major coronavirus threat and discrimination against Black Americans in medical settings. Therefore, it is clear that a substantial proportion of Black Americans are distressed by the ongoing coronavirus threat combined with anticipatory stress of unfair treatment in the healthcare system.

Figure 1.

Psychological distress by perceived COVID-19 health threat and beliefs about discrimination in medical settings.

Discussion

A long tradition of research has shown that perceived threats and beliefs about discrimination in medical settings are risk factors for poorer mental health among Black Americans (Pearlin 1999). Though important, we are unaware of previous research examining the interplay between perceived COVID-19 health threat, discrimination in medical settings, and psychological distress among Black Americans (Chowkwanyun and Reed 2020). This empirical void is curious, given the disproportionate impact of the coronavirus outbreak on Black Americans (Yancy 2020). Moreover, this absence in the literature persists despite ongoing evidence that issues related to the coronavirus outbreak will remain a critical social problem among Black Americans for some time to come (Webb Hooper et al. 2020). To address this gap, we drew on a subsample of Black Americans from a probability-based online survey panel representative of the U.S. adult population to assess the interplay between perceived COVID-19 health threat, beliefs about discrimination in medical settings, and psychological distress. Our findings suggest that perceiving the coronavirus outbreak as a major threat to one’s health and beliefs about racial bias in medical settings are associated with increased psychological distress among Black Americans.

Our primary goal was to shed light on the mental health-related consequences of perceived COVID-19 health threat among Black Americans. Consistent with prior research, we observed that perceiving the coronavirus as a major (but not minor) threat to one’s health was associated with higher psychological distress levels among Black Americans. These associations were independent of differences in sociodemographic and political factors. Because respondents who believed the coronavirus threat was a minor threat to their health were statistically indistinguishable from those who did not, there was a clear threshold in the association between perceived COVID-19 health threat and psychological distress.

Our secondary goal was to examine how beliefs about racial discrimination in medical settings relate to psychological distress among Black Americans and assess whether these beliefs about discrimination exacerbated the relationship between perceived COVID-19 health threat and psychological distress. Findings revealed that Black Americans who perceived the coronavirus outbreak as a significant threat to their health and believed in discrimination in medical settings are especially at risk for elevated distress levels. Furthermore, even respondents who only perceived the coronavirus outbreak as a minor threat experienced heightened distress if they also believed that Black Americans receive poorer service in medical settings. The awareness of discrimination in medical settings, combined with perceived COVID-19 health threat, are sources of compounded distress. Though our measures are perceptual, they are rooted in empirical realities; perhaps, more importantly, these beliefs have psychological ramifications.(Egede and Walker 2020) Black Americans must navigate the contemporary sociopolitical context marked by a pandemic, racial unrest, and ongoing racial disparities in health and healthcare. These compounded co-occurring stressors, in turn, appear to impose a greater psychological tax on Black Americans than if only one of these stressors were operant.

Scholars of racial health disparities have not systematically examined the interplay between perceived COVID-19 health threat, beliefs about discrimination in medical settings, and mental health among Black Americans.(Khazanchi, Evans, and Marcelin 2020) Thus, knowledge on the mechanisms that might explain our observed interrelationships examined in this study is lacking. Laster Pirtle (2020) argues that neighbourhood conditions (e.g. census-based or self-assessed measures of neighbourhood characteristics) play an essential role in shaping health disparities during the coronavirus outbreak. Prior research has uncovered links between poorer neighbourhood contexts and perceived threats, beliefs about discrimination, and mental health among Blacks Americans. Therefore, neighbourhood contexts may be a potential mechanism through which perceived COVID-19 health threat and beliefs about racial discrimination in medical settings might have influenced psychological distress levels among Black Americans. Research also suggests that older Black Americans are disproportionally are most affected by COVID-19 stressors, morbidity, and mortality (Chatters, Taylor, and Taylor 2020). Therefore, future work should examine how the interplay between perceived COVID-19 health threat, beliefs about discrimination, and health among older Blacks.

We acknowledge there are dimensions of the current study that warrant comment. Given that the PRC has not consistently included psychological distress measures in panel data, we cannot make inferences about causality between our variables of interest or assess whether these relationships vary over time. Our measures of psychological distress are derived from established, well-validated measures. However, the PRC adjusted the response options in these measures to the past week, which limited our ability to capture the highly dynamic course of the coronavirus outbreak. Nevertheless, this study has some important strengths. We rely on data from a nationally representative sample of adults that contains both a measure of perceived COVID-19 health threat, beliefs about racial discrimination in medical settings, and psychological distress. Though limited, the measure of psychological distress used in this study suggests it has sufficient internal reliability. To date, we are not aware of any nationally representative dataset with a sufficient number of Black Americans, nor a rich set of psychosocial and attitudinal measurements that were also administered before and shortly after the coronavirus outbreak.

The coronavirus outbreak represents a significant social problem in the United States and will usher in many health challenges facing Black Americans. This examination spotlighted the importance of the perceived threats and beliefs about discrimination in shaping Black Americans’ psychological distress levels.(Novacek et al. 2020; Poteat et al. 2020) Moreover, our findings highlight the need to create policy-based interventions that offset this outbreak’s health-related consequences and severely affect Black Americans’ quality of life.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Assari S, and Habibzadeh P. 2020. “The COVID-19 Emergency Response Should Include a Mental Health Component.” Archives of Iranian Medicine 23 (4): 281–282. doi: 10.34172/aim.2020.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TN 2003. “Critical Race Theory Speaks to the Sociology of Mental Health: Mental Health Problems Produced by Racial Stratification.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44 (3): 292. doi: 10.2307/1519780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC COVID Data Tracker. n.d. Retrieved December 12, 2020, from https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#cases_casesper100klast7days.

- Chae DH, Nuru-Jeter AM, Lincoln KD, and Francis DD. 2011. “Conceptualizing Racial Disparities in Health: Advancement of a Socio-Psychobiological Approach.” Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race 8 (1): 63–77. doi: 10.1017/S1742058X11000166. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor HO, and Taylor RJ. 2020. “Older Black Americans During COVID-19: Race and Age Double Jeopardy.” Health Education & Behavior 47 (6): 855–860. doi: 10.1177/1090198120965513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowkwanyun M, and Reed AL. 2020. “Racial Health Disparities and Covid-19: Caution and Context.” New England Journal of Medicine 383 (3): 201–203. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2012910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway LG, Woodard SR, and Zubrod A. 2020. Social Psychological Measurements of COVID-19: Coronavirus Perceived Threat, Government Response, Impacts, and Experiences Questionnaires [Preprint]. PsyArXiv. doi:. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Egede LE, and Walker RJ. 2020. “Structural Racism, Social Risk Factors, and Covid-19: A Dangerous Convergence for Black Americans.” New England Journal of Medicine 383 (12): e77. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2023616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feagin J, and Bennefield Z. 2014. “Systemic Racism and U.S. Health Care.” Social Science & Medicine 103: 7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gengler AM, and Jarrell MV. 2015. “What Difference Does Difference Make? The Persistence of Inequalities in Healthcare Delivery: The Persistence of Inequalities in Healthcare Delivery.” Sociology Compass 9 (8): 718–730. doi: 10.1111/soc4.12286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Hudson D, Kershaw K, Mezuk B, Rafferty J, and Tuttle KK. 2011. “Discrimination, Chronic Stress, and Mortality Among Black Americans: A Life Course Framework.” In International Handbook of Adult Mortality, 311–328. Dordrecht: Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-90-481-9996-9_15 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khazanchi R, Evans CT, and Marcelin JR. 2020. “Racism, Not Race, Drives Inequity Across the COVID-19 Continuum.” JAMA Network Open 3 (9): e2019933. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer A, and Kramer KZ. 2020. “The Potential Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Occupational Status, Work from Home, and Occupational Mobility.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 119. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laster Pirtle WN 2020. “Racial Capitalism: A Fundamental Cause of Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Pandemic Inequities in the United States.” Health Education & Behavior 47 (4): 504–508. doi: 10.1177/1090198120922942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malat J, and Hamilton MA. 2006. “Preference for Same-Race Health Care Providers and Perceptions of Interpersonal Discrimination in Health Care.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 47 (2): 173–187. doi: 10.1177/002214650604700206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novacek DM, Hampton-Anderson JN, Ebor MT, Loeb TB, and Wyatt GE. 2020. “Mental Health Ramifications of the COVID-19 Pandemic for Black Americans: Clinical and Research Recommendations.” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy 12 (5): 449–451. doi: 10.1037/tra0000796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI 1999. “The Stress Process Revisited.” In Handbook of the Sociology of Mental Health, edited by Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, and Bierman A, 395–415. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2020. U.S. Public Sees Multiple Threats From the Coronavirus - and Concerns are Growing. Washington, D.C: Pew Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Poteat T, Millett GA, Nelson LE, and Beyrer C. 2020. “Understanding COVID-19 Risks and Vulnerabilities among Black Communities in America: The Lethal Force of Syndemics.” Annals of Epidemiology 47: 1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stepanikova I 2012. “Racial-Ethnic Biases, Time Pressure, and Medical Decisions.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 53 (3): 329–343. doi: 10.1177/0022146512445807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ryn M, Burgess D, Malat J, and Griffin J. 2006. “Physicians’ Perceptions of Patients’ Social and Behavioral Characteristics and Race Disparities in Treatment Recommendations for Men With Coronary Artery Disease.” American Journal of Public Health 96 (2): 351–357. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield KE, Allaire JC, Belue R, and Edwards CL. 2008. “Are Comparisons the Answer to Understanding Behavioral Aspects of Aging in Racial and Ethnic Groups?” The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 63 (5): P301–P308. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.5.P301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb Hooper M, Napoles AM, & Perez-Stable EJ. 2020. “COVID-19 and Racial/Ethnic Disparities.” JAMA 323 (24): 2466–2467. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy CW 2020. “COVID-19 and African Americans.” JAMA 323 (19): 1891. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]