Abstract

Crisis intervention psychotherapy (CIP) is an underutilized form of therapy that can be offered as a treatment during psychiatric disasters and emergencies, and it may be especially useful during the age of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). CIP is a problem-solving, solution-focused, trauma-informed treatment, utilizing an individual or systemic/family-centered approach. CIP is a brief form of psychotherapy delivered as a companion or follow-up to psychological first aid. Crisis psychotherapy is designed to resolve a crisis and restore daily functioning. CIP can be adapted as a single session for a COVID-19 mental health emergency or for a hotline or as 2 to 20 sessions of treatment with COVID-19 patients and families offered virtually on a psychiatric inpatient unit, through a consultation-liaison service, or in outpatient settings. This article reviews the history of critical incident stress management and the use of its replacement, psychological first aid. The history and core principles of crisis psychotherapy and 8 core elements of treatment are described. The use of digital and virtual technology has enabled the delivery of crisis psychotherapy during the COVID-19 pandemic. A case study of a family impacted by COVID-19 is reported as an illustration. The use of a 6-week timeline, an ecological map, and a problem-solving wheel-and-spoke treatment plan are demonstrated.

KEY WORDS: crisis intervention, crisis psychotherapy, brief psychotherapy, solution-oriented psychiatric emergency treatment

As a result of the last 2 decades, we have a treasure trove of experiences in responding to hurricanes, epidemics, disasters, suicide, violence, intimate partner violence, and traumas of all kinds. Crisis models have been utilized during disasters, emergencies, and traumas by hotlines, police, teachers, school and college counselors, attorneys, rescue workers, clergy, and mental health professionals.

Critical incident stress debriefing (CISD),1 as a single 2-hour group session, with 7 elements, was offered to first responders by health professionals, immediately after a trauma or disaster.1 It is part of critical incident stress management (CISM) which involves a larger array of preincident planning options; immediate postincident group treatments; and educational, training, and policy recommendations.1

Both CISD and CISM, as cohesive treatments, were historically offered by personnel without any mental health training. Both have been discredited as psychotherapeutic treatments, although elements of these programs remain useful. Two meta-analyses of CISD and CISM have shown that: (1) many first responders do not need treatment after exposure to trauma, (2) many first responders get worse when these interventions are received as mandatory treatment, and (3) these interventions have been shown to be ineffective as prevention or treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).2,3

Psychological first aid, the current approach for acute disaster management, is now offered to first responders seeking help.4–6 It is always offered voluntarily, never mandated, and is focused on safety, calming, connectedness, self-efficacy, hope, referral, and follow-up using all available resources. It is provided in a stepwise fashion, to individuals (not in a group format) tailored to each person’s individual needs. As a front-line strategy for mass trauma, variations of psychological first aid are currently used worldwide. They are not intended for delivery by mental health specialists and are not offered as prevention or treatment for PTSD. Data supporting the proven efficacy of psychological first aid are also lacking, so it is considered “evidence-informed” but without proof of effectiveness.5,6

Crisis intervention psychotherapy is typically delivered by trained mental health professionals, often in community mental health settings, and it can be offered after disasters. As psychotherapy, it is a problem-focused, solution-oriented, trauma-informed treatment, utilizing an individual or systemic/family-centered approach.7–9 This brief psychotherapy is designed to resolve the crisis and restore functioning.

Crisis intervention psychotherapy can be easily taught to psychiatrists or other mental health professionals who have psychotherapy expertise. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) does not recommend any crisis-oriented treatment as a core psychotherapy competency or requirement.10 This is not surprising as crisis intervention psychotherapy has not been manualized, nor has it been systematically studied as a potential evidence-based psychotherapy for treating crises. However, since we currently need crisis treatments in the age of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), we can rely on the face validity of this treatment or the “wisdom” of many community mental health settings which have continued to use crisis psychotherapy since the 1960s. “Wisdom toward a common good” is described by Sternberg11 and by Levitt and Piazza-Bonin.12 This concept involves clinicians who have a deep understanding of reality and is based on concern and a psychological understanding of self and others, the ability to take the long-term view of problems, learning from mistakes, intuition, maturity, and the ability to “see-through” complex situations and circumstances.

With the caveat that crisis psychotherapy is a “wisdom-based” treatment with face validity, it can be used for COVID-19 emergencies, on inpatient services, consultation-liaison services, and outpatient services. A recently developed hotline using this model is well described elsewhere.13

This article briefly reviews the history and theory of crisis intervention psychotherapy, defines some of its useful core characteristics, and discusses how this approach can be applied in the age of COVID-19. Crisis intervention psychotherapy can be delivered by trained mental health professionals with psychotherapy expertise and uses tools such as a 6-week timeline, an ecological map, a problem-solving wheel-and-spoke treatment plan, and eclectic psychotherapeutic techniques with an individual and/or systemic focus.14 The application of the crisis psychotherapy approach is illustrated by a clinical case report of a family dealing with a COVID-19 crisis.

CRISIS INTERVENTION THEORY

During World War I, Thomas Salmon,15 a British military physician, was asked to evaluate and explain why severe “shell shock” (traumatic neurosis) experienced by French soldiers was producing much less psychological paralysis than in British soldiers. He reported 3 factors that accounted for the French advantage: French soldiers (1) were told that they could expect to recover; (2) received immediate psychological treatment close to the front; and (3) were returned to battle as quickly as possible. These 3 principles—expect recovery, treat immediately in a community (not hospital) environment, and return to daily functioning—became the cornerstone of all modern crisis theories and disaster management strategies.

Eric Lindemann16 applied these principles in his research on the aftermath of the 1942 Boston Coconut Grove fire. At that time, it was the largest loss of American lives in a single nonwar incident. Lindemann learned from survivors that healthy people, dealing with horrific experiences, could develop an emotional crisis of pain, confusion, anxiety, and temporary difficulty in daily functioning, typically lasting 6 weeks. The crisis outcome was related to the severity of the stressor, the personal reactions to the trauma, the effects on the person’s support network of family and friends, and the degree of disruption to the entire community.

Erik Erikson,17 a sociologist, introduced the idea of developmental stages and developmental crises. His 8 stages were seen as normative processes during which age-specific psychological tasks, transitions, and crises were routinely encountered. An inability to successfully negotiate a developmental crisis makes it difficult to progress to the next stage.

Crisis practitioners incorporated Erikson’s idea of developmental milestones, such as adolescence, and included other developmental challenges, such as leaving home for the first time, the midlife crisis, and parents’ “empty nest syndrome.” For many patients, a transition from one life phase to the next, such as marriage, divorce, retirement, or an illness, may bring the potential for a new developmental crisis.

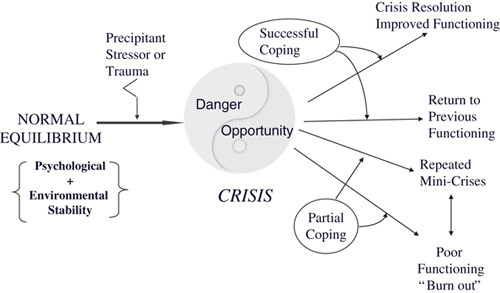

Gerald Caplan18,19 used these ideas in developing crisis treatments that were implemented during and crucial to the community mental health movement in the 1960s and 1970s. He defined the “crisis state” as a brief, personal psychological upheaval, precipitated by a “hazard,” which produced emotional turmoil and disruptions in daily routines. Caplan demonstrated that a crisis implies both “danger and opportunity for growth.” He confirmed that most crises resolve in about 6 weeks, with 4 possible outcomes: (1) improved functioning; (2) return to baseline functioning; (3) repeated mini-crises; or (4) stable but lower levels of functioning (see Fig. 1 for an overview of crisis theory).

FIGURE 1.

Crisis intervention.

Since the development of crisis treatments by these giants, a large group of authors have continued to contribute many stepwise insights and interventions. Aguilera,20 Flannery and Everly,21 Greenstone and Leviton,22 Kanel,23 Roberts,24 Feinstein,7–9 and James and Gilliland,25 all have presented similar models and various elaborations. A recent and comprehensive book about crisis intervention by Cavaiola and Colford26 offers a broad review of most of these models. Readers are referred to Simpson and Feinstein9 for a description of the delivery of crisis intervention in an integrated care environment.

EVALUATING A CRISIS

A comprehensive evaluation of a crisis leading to crisis psychotherapy involves understanding 8 components: (1) the normal equilibrium state; (2) the precipitant, stressor, hazard, or inciting trauma; (3) the individual’s interpretation/meanings of the events; (4) the crisis state; (5) selective history; (6) system of social supports; (7) preexisting personality disorder or other psychiatric condition(s); and (8) use of community resources.8

Normal Equilibrium State

Under normal circumstances, an individual has a homeostatic balance between his or her psychological make-up and environmental supports, which permits stable daily functioning. A balance between the person’s wishes, fears, skills, values, and ideals determines psychological equilibrium. Environmental equilibrium refers to a stable balance among physical needs, interpersonal relationships, other social supports, resources, and community integrity.

Precipitants or Stressor

A precipitant or a hazard can disturb a person’s normal equilibrium. To determine the precipitants of any crisis, ask: “Why now? What happened? Where? and When?” Crisis theory posits that 25% of precipitants have occurred on the day of initial outreach for treatment; 25% of stressors are events occurring in the past week; and 50% of stressors occurred within the previous 6 weeks.7–9,16

The Social Readjustment Scale lists 43 common life precipitants that may cause a crisis.27 Patients who experience many of these stressors have a 50% chance of suffering with a major medical or psychological problem within 2 years.27 Hobson et al28 revised this scale, with a list of 51 external life stressors that may precipitate a crisis. The top 20 items in this scale are grouped into 5 domains: (1) death and dying; (2) health care issues; (3) stress related to crime and/or the criminal justice system; (4) financial or economic issues; and (5) family stresses. This revised scale includes events ranging in severity from the most stressful #1 to least stressful #51. These stresses include: #1 death of a spouse; #7 divorce; #11 domestic violence or sexual abuse; and #16 surviving a disaster. The scale also includes events that many would consider positive, yet stressful, such as #32 getting married; #42 experiencing a large monetary gain; and #49 retirement. These common stressors represent the events most likely to produce emotional turmoil and a transient inability to adapt, signifying a crisis.

Interpretation of the Meaning of the Stressor

All individuals interpret or add their own meaning to the stressor, based on their psychological history and the multicultural, religious, and ethnic beliefs of their life context. Uncovering the stressors and their meanings often suggests an appropriate problem-solving approach. For example, a suicide attempt in Japanese culture may be honorable, for one who has dishonored his family, while it may be considered a mortal sin if the patient is Catholic. It is important to explore the significance of events (eg, to explore the psychological meaning of an affair, terrifying dreams, fears, panic, etc.).

The Crisis State

A precipitant heralds the crisis or inner turmoil or disorganization, overwhelming a person’s ability to cope and adapt. A crisis signals “Danger” (dysfunction) or “Opportunity” (for successful coping).18,19 A crisis therapist’s primary focus is oriented toward identifying the problem and finding a solution, with the primary goal of restoring daily functioning, while promoting self-care, reducing stress, encouraging the person to avoid substance use, etc. Many people in crisis do not seek help yet may be brought in by others, or the police. Some family members may ask for help for loved ones in crisis or individuals may seek help for a colleague in crisis.

Selective History

Knowledge of a patient’s entire history is often not needed or relevant to help explain and resolve a current crisis. However, taking a patient’s selective history that allows one to relate the current crisis to similar past events may be quite useful to explain and help resolve a current crisis.15 For example, a patient’s selective history and relevant history of significant others (eg, of past trauma, violence, suicide, or substance use, and the circumstances surrounding these past events) may provide valuable clues to understanding a similar current crisis. Discovering anniversaries or resolution of past events that are similar to the current crisis may help in developing a deeper understanding, while also suggesting problem-oriented solutions that have previously worked. Screening for major events from the patient’s history, such as traumas, loss, separations, or deaths, may also provide additional context for treating a current crisis.

Social Systems

Most daily social interactions are local, with family, friends, and work colleagues. These social interactions are enabled by the community resources that provide housing, food, clothing, work, education, finances, and medical care. Our local systems are generally supported by the state, national and, as in the case of COVID-19, international organizations such as the World Health Organization. Our social systems support our entire infrastructure; from roads and airways to our monetary system, and they include legal and constitutional protections. In general, stable social systems at multiple levels tend to provide the greatest buffers against crises and disasters of all types.29

The COVID-19 pandemic has dramatically disrupted our medical services at all levels, leading to death and morbidities with devasting impacts.30–32 The significant mental health impacts of COVID-19 are now emerging. Preliminary evidence suggests that symptoms of anxiety and depression (16% to 28%) and self-reported stress (8%) are common psychological reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic in the general population.32 In addition “insomnia, indignation, worries about their own health and family, sensitivity to social risks, life dissatisfaction, phobias, avoidance, compulsive behavior (handwashing), physical symptoms and social functioning impairment” have been reported.31 People living in crowded environments, those with preexisting medical, psychiatric, or substance use problems, and those who have experienced economic losses are all at increased risk for crises and adverse psychosocial outcomes.30

Health care providers are also particularly vulnerable to emotional distress and crises given their risk of exposure to the virus, concerns about infecting and caring for their loved ones, shortages of personal protective equipment, increased work hours, and involvement in emotionally and ethically fraught resource-allocation decisions and interactions with COVID -19 families.31,32 Researchers have reported that nurses, women, those who are young, front-line health care workers, those working in Wuhan China, and mid-level professionals have all experienced more severe degrees of mental health symptoms than other health care workers.30

In the absence of a medical cure for COVID-19, the global response of quarantine, social isolation, and reduced social contact, leads to reduced access to support from family and friends and increases the risk of domestic violence and child abuse.30 Social isolation causes loneliness and increases the risk for worsening anxiety and depressive symptoms. In addition, social isolation has reduced access to medical care. Digital technology, as discussed below, has enormous potential to mitigate social isolation.

Previous Psychiatric Illness or Personality Disorder

For many patients, there is little correlation between a previous psychiatric illness or personality disorder and their capacity to cope or adapt to an acute crisis or trauma. A person with schizophrenia may be just as capable of handling an acute crisis, such as a fire, as others who do not have a psychiatric disorder. How a patient handles an acute crisis or trauma depends primarily on the variables discussed above, including the precipitant itself, the meaning of the events, the nature of the crisis, the patient’s strengths, coping skills, and ability to adapt, and the effectiveness of the patient’s support network. However, in many cases, a preexisting psychiatric condition (eg, major depression, personality disorder, or addiction) may interfere with coping and the ability to adapt to a new crisis.29 This is especially true with COVID-19 as it is clear that the pandemic does exacerbate preexisting psychiatric conditions.30 Thus, long-standing mental health issues may need to be addressed simultaneously with the acute crisis to bring about a full crisis resolution.

Sequelae of a Crisis or Trauma

Although most patients recover from a crisis within 6 weeks, others can suffer from the sequelae of a trauma or crisis for years. The prognosis after any disaster or trauma depends on 3 groups of factors: pretraumatic, traumatic, and posttraumatic.29 Pretraumatic factors include psychiatric or addiction history, history of child abuse or neglect, physical illness, genetics, coping styles, sex, and culture. Traumatic risk factors include the type, severity, scope, and duration of the trauma or crisis. Posttraumatic risk factors include individual coping, problem-solving style, and availability of support and resources. Recovery is more likely after a less severe trauma or a crisis that is of shorter duration. With regard to the possible long-term outcomes of COVID-19, they are likely to be world-changing and recovery may take years or may never happen in some locations. However, eventually, in many places, a new stability will be achieved, most at a lower level of functioning, but some, as with all crises, may adapt demonstrating an improved level of functioning.

Telemental Health and Crisis

The COVID-19 crisis and global pandemic has highlighted the growing role of digital technology to offer relief, hope, and access to crisis and mental health treatments.33–35

Despite the laments of many clinicians, 2 meta-analyses have documented that telemental health treatment is comparable to in-person services and is particularly advantageous and inexpensive for use with current technologies in isolated communities.34,35 In the era of COVID-19, telemedicine has become an essential service. Digital technologies (eg, Zoom, Google Hangouts, Microsoft Teams) and apps36 can be used for the delivery of psychological first aid, crisis psychotherapy, and other mental health treatments, which collectively can relieve some of the symptoms related to quarantine and social distancing. Worship services and many social events can be conducted in online gatherings. Many workplaces and schools are creating virtual spaces where people can work or learn via video conferencing. The benefits and some of the limitations for the poor and underserved (eg, digital deserts) are clear, while the long-term effects on clinicians and patients (eg, Zoom fatigue; clinician and patient preference; consensus about efficacy; issues of confidentiality) are less clear.33

A likely silver lining is that our increased use and investments in digital health are already transforming health care and improving access.33–36 Digital technology is already offering unprecedented access to high-quality mental health care and it can provide virtual medical care in rural areas and poor or underserved communities that have had little or no access to medical or psychiatric care.33,34 The rapid expansion of the digital world during the COVID-19 pandemic (eg, the explosion in the use of Zoom) may also push the envelope and add some pressure for solving problems related to digital deserts in our rural, poor, and underserved communities.

CRISIS PSYCHOTHERAPY: A COVID-19 CASE

Case Background: John and Mary

John is a 50-year-old medical office manager, married to Amy, a nurse. Shortly after his wife developed respiratory distress and was admitted to the hospital, John called the crisis hotline in a panic.13 Six weeks before this crisis, Amy had discovered John was having an affair with one of his employees. John described his marriage as “two people, living separate lives.” After many arguments and threats of divorce, he became depressed and began drinking heavily. About 4 weeks before Amy was admitted to the hospital, Amy gave John an ultimatum: “go into couples’ therapy or leave.” Two weeks before Amy’s admission, when the governor announced the COVID-19 stay-at-home order, their 2 children, 7 and 10 years old, had to start staying home from school. John began this less than ideal homeschooling with some help from Amy when she was not working. As Amy began working many extra COVID-19 shifts at the hospital, John felt tired and at times overwhelmed, and he became more depressed. With scarce personal protective equipment and working extra shifts, Amy became sick with COVID-19 and quarantined at home. She was admitted to the hospital a day before John’s call to the hotline. John requested and was referred for crisis psychotherapy.

Crisis Intervention Psychotherapy and Cognitive-behavioral Therapies (CBTs)

Crisis psychotherapy is typically brief and intense, lasting 2 to 20 sessions. Often, 6 weeks of psychotherapy is the optimal treatment for the resolution of most acute crises. The frequency of sessions can range from weekly to 2 times per week. Crisis psychotherapy can be conducted as an individual stand-alone treatment or as family, couples, or a systemic intervention therapy with a problem-solving, solution-oriented approach.

Variations of CBT may also be offered concurrently with crisis psychotherapy or alone for treatment of trauma (eg, CBT for trauma, cognitive processing psychotherapy, or eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy), to improve sleep (CBT for insomnia), or to address anxiety, panic, or depression. CBT approaches are most useful for individuals with symptoms or a specific diagnosis, but they are less focused on here-and-now problem-solving of urgent practical issues and less helpful at addressing families, couples, and systemic issues.

The crisis approach also focuses individuals toward mobilizing needed community resources as an aid to solving systemic problems (eg, homelessness, food insecurity, obtaining medical care, dealing with insurance or other health system issues, or dealing with other bureaucracies).

In general, the involvement of a supportive family and other vital social supports in crisis psychotherapy tends to speed recovery. A family can present multiple points of views, assist with problem-solving, provide resources, and help reach out to needed community resources. It is useful to begin crisis psychotherapy with an initial intake phase focused on the “why now?” understanding of the crisis precipitants, and developing a 6-week timeline, ecological map (eco-map), problem formulation, and acute management strategy.

This initial intake phase, which typically may take 1 to 3 sessions, is followed by a mid-treatment phase of working through problems with restoration of coping and adaptation. Therapy continues to a termination phase of at least several sessions. It is useful to plan the total number of sessions in advance from the beginning and to count them down after each session, keeping the urgency of crisis resolution ever present.

Intake

Precipitant and Timeline

Uncovering the precipitant for the crisis should progress to discovering the 6-week time line. John's 6-week timeline is illustrated in Figure 2. An initial conversation during acute crisis psychotherapy typically begins with “How can I help?” and continues with empathic listening and exploration of the patient’s feelings. While listening, it is helpful to emphasize the patient’s strengths37 and focus on the “Why now?” The precipitant of John’s crisis was his fear of his wife Amy’s admission and potential death and his immediate need for childcare. Two-days after contacting the hotline, he began virtual crisis psychotherapy. John’s strengths were emphasized—his good judgment in immediately reaching out for help, and his concern and caring for his wife and children. In general, treatment seeking during COVID-19 is often precipitated by the need to quarantine, social isolation, work stress or loss, and loss of income. Asking about suicide, intimate partner violence, trauma, substance use, and acute medical problems is warranted in most crisis situations. All emerging safety issues should become the primary focus of psychotherapy.

FIGURE 2.

Six-week timeline. COVID-19 indicates Coronavirus Disease 2019.

Eco-map

An eco-map helps both the clinician and the patient gain an overview of all of the social supports and resources that can be mobilized.38 See Figure 3 as an illustration of John’s eco map.Four useful questions can help assess the quality of John’s support network: (1) Who is available to help? (2) Are the potential helpers interested in helping? and (3) Are the potential helpers capable or have the ability to help? (4) What are the digital needs and potential limitations in communication due to COVID-19? Sometimes, due to work or childcare responsibilities, family members may not be available; a support system may be exhausted or burned out and no longer interested in helping; or children or disabled adults may not be capable of caring for the patient. The availability of technology and capabilities to use technology for communication has become essential in the age of COVID-19. John’s ecological map, which was developed early in his treatment, included a genogram of his entire family, other potential resources, and a discussion of his needs and use of digital technology. See Figure 3 for a pictorial representation of the eco-map developed with John and his therapist.

FIGURE 3.

Ecological map.

When a patient is in crisis, the therapist can help mobilize the resources within the patient’s ecological network.38 John’s eco-map revealed that his mother-in-law and perhaps family friends would be needed, available, and competent to assist. John had an iPhone, his children had iPads and computers, while his mother-in-law was technologically inexperienced. After a few weeks, with help from his friends, who had children in the same school, John managed to get his son Peter hooked up with the less than adequate virtual school programing that was just getting underway.

Formulation and Problem Management

Developing a problem-oriented formulation begins by focusing on 1 major problem, and progressing to a list of contributing problems, while also utilizing the information from the eco-map to suggest wheel-and-spoke problem identification and solutions.8 Figure 4 shows the wheel-and-spoke treatment plan John co-created with his therapist. The core problem for John was his wife’s hospitalization. John’s contributing problems and solutions were prioritized in order of their immediacy. All the identified problems are illustrated in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Wheel-and-spoke problem-solving COVID-19 indicates Coronavirus Disease 2019.

Crisis Mid-phase and Working Through

Crisis psychotherapy and problem-solving in the age of COVID-19 includes: (1) determining the patient’s and therapist’s availability and capability of using virtual technology33–35; (2) identifying the patient’s maladaptive defenses and coping styles; (3) identifying and mobilizing the patient’s strengths; (4) helping the patient use adaptive coping styles and problem-solving; (5) developing solutions for problem resolution; and (6) using mental health applications (apps) as additional support.36

Maladaptive Defenses, Coping, and Adaptive Problem-solving

Crisis resolution can be facilitated by evaluating the patient’s maladaptive defenses and coping styles while suggesting strengths that could be used to expedite more adaptive solutions.7,8 Table 1 presents a list of maladaptive and adaptive coping styles. John’s fears of his wife dying and the need to manage the home, childcare, and school demands in her absence initially took center stage. These problems required practical solutions, such as finding out how to communicate with the hospital and verifying Amy’s insurance and how to speak with Amy’s physician, arrange childcare, and setting up homeschooling. John also needed help in psychotherapy with managing his angst about not being able to visit or even speak with Amy. He also needed to arrange for regular childcare with his mother-in-law. He also eventually needed additional help from friends in setting up “virtual school” for his children. Phone calls continued to be the mainstay of all communication with Amy and his mother-in-law. It was not until 5 days after her admission that Amy was well enough to speak with John by phone. It took a week until the hospital had set up iPads for Amy and other quarantined patients, until John was finally able to see Amy. This contact was what he needed to be reassured of her immediate survival and likely recovery. After Amy had been hospitalized for 2 weeks, it was clear that her recovery was progressing. John struggled to talk with Amy about his feelings of guilt for having had an affair, something she initially refused to discuss. Gradually, in psychotherapy, he began to understand his previous denial of long-standing marital problems and his conflict-avoidant coping style. John recognized that he rarely expressed any dissatisfaction or anger with Amy. He realized that his affair was an angry but passive-aggressive way of expressing fury with Amy. He felt Amy had been too controlling and was not listening or responding to his needs. His long-standing marital dissatisfaction was exacerbated by Amy’s unavailability when she began having to take on additional COVID-19 work shifts. During this middle phase of his psychotherapy, John reported that, at the start of the couple’s therapy (4 weeks before Amy’s hospitalization), he had felt ashamed about the affair and suicidal. He recognized that his excessive drinking made him feel embarrassed and even more depressed. By taking a selective history, the crisis therapist uncovered the fact that John’s father was an alcoholic who had multiple affairs. His father had committed suicide after his mother’s discovery of a third affair and her demand for a divorce. John had turned 50 earlier this year and was having an anniversary reaction; unconsciously reliving the loneliness and anger he had felt at the time of his father’s death. He was also missing his father. His needs and insecurities were further amplified by Amy’s “total COVID-19 unavailability” both before and after she was hospitalized. In addition to worrying about Amy, John felt inadequate as a father, overwhelmed with these new childcare demands and feeling useless as a homeschool teacher. The therapist supported John’s strengths for rational decision-making, emphasizing his courage in addressing his marital problems and his efforts to take care of his children. He encouraged John’s self-care and efforts to reach out to his mother-in-law and friends. John also agreed to contact his primary care doctor for evaluation and possibly medications for his insomnia, depression, and urges to drink. His therapist also asked John to explore online access to AA meetings and to begin to exercise again. The psychotherapist also recommended that, between sessions, John might use one or several phone applications (apps). These apps included: Quit That! to help him stop drinking; PTSD Coach if he was bothered by intrusive memories of his father’s suicide and Amy’s potential fatality; I Mood Journal to monitor his depression and anxiety; and Breathe2Relax for stress management.36,39 Table 2 presents a list of evidence-based apps.

TABLE 1.

Coping Styles

| Maladaptive coping styles |

| Use of alcohol or drugs |

| Feeling overwhelmed, developing panic, anxiety, or depression |

| Deceptive, antisocial: use of dishonesty, lying, cheating, or stealing to resolve a crisis |

| Suicidal: using threats of suicide or suicide attempts to cause someone to solve a problem |

| Violence: using threats or actual violence to establish control and solve a problem |

| Avoidance or denial: failure to confront or acknowledge a problem |

| Somatization; displaying physical symptoms as a method of expressing emotions |

| Impulsive: unpredictable or impulsive responses, without anticipation of possible consequences or outcomes |

| Random, chaotic: nonproductive and an extreme form of trial and error with an impulsive style; often seen in prolonged traumatic or psychotic states |

| Adaptive coping styles |

| Intuitive: using imagination, feelings, and perceptions to solve a problem |

| Logical, rational: carefully reasoned in a logical and deductive style |

| Trial and error: exploring solutions (eg, if one fails, modifying and engaging in another) |

| Help-seeking: gathering information and then proceeding |

| Self-care: pursuing wellness through nutrition, exercise, stress management, or sleep hygiene |

| Wait and see: allowing time or circumstance to determine the outcome |

| Action-oriented: taking action to immediately rectify the problem |

| Contemplation: quietly thinking over the problem before acting |

| Spiritual: prayer or asking for direction |

| Emotional: using emotions, such as sadness or anger, to direct problem-solving |

| Directing, controlling oneself, or directing others to solve a problem |

| Manipulative: using various manipulative styles to resolve the crisis |

TABLE 2.

Evidence-based Mental Health Applications (Apps)

| PTSD Coach: Created by the VA’s National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). This app offers a self-assessment for PTSD, opportunities to find support, develop positive self-talk, and anger management. Free |

| Mood Kit: Uses cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and provides users with over 200 different mood improvement activities. One-time small fee |

| Mayo Clinic Anxiety Coach: Used to reduce a wide variety of fears and worries from extreme shyness to obsessions and compulsions. Makes a list of feared activities, and then guides the person through mastering them, one by one. Free |

| What’s Up: uses cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and acceptance commitment therapy methods to help one cope with depression, anxiety, stress, and more. Free |

| I Mood Journal: Records mood and symptoms, sleep, medications, and energy cycles. One-time small fee |

| Quit That! Helps with habits or addictions, drinking alcohol, smoking, taking drugs. Tracks usage and monitors progress. Free |

| Lifesum: Resource for healthy living. Users can set personal goals (eg, eating, exercise, healthier living). Free |

| CBT-I Coach: Helps alleviate insomnia or sleep problems. Learn about sleep, develop positive sleep routines, and improve one’s sleep environment. From the VA’s National Center for PTSD, Stanford School of Medicine, US Department of Defense’s National Center for Telehealth and Technology. Free |

| Breathe2Relax: Decreases the body’s “fight-or-flight” stress response by teaching diaphragmatic breathing. Free |

| Calm: Guided meditations for stress and anxiety; provides sleep stories, breathing programs, and relaxing music. Monthly fee |

| Headspace: Learn and practice mindfulness and meditation. Hundreds of meditations on everything from stress and anxiety to sleep and focus. Moderate monthly fees |

| Talkspace: One can text messages to a trained professional as needed and receive daily responses. Depression and anxiety focused. Significant weekly fees |

Termination

Fortunately, by the fourth week of John’s treatment, Amy had recovered enough to return home. During the sixth week of John’s treatment, when Amy was mostly recovered, the couple re-engaged with their couples therapist for 3 intense telemental health couple sessions. They made some strides to reconnect, both greatly relieved by her survival. They began working together in the care and some additional homeschooling of their children. Amy verbalized her anger over his affair, stating she remained unsure if she could ever trust him again. John was remorseful. The couple agreed they would continue their ongoing work with their couples therapist. John felt that crisis psychotherapy was no longer needed. Upon termination of the crisis psychotherapy, a 12-step self-help crisis resolution strategy (Table 3) was reviewed with John to be used should a new crisis emerge.

TABLE 3.

Crisis Resolution Strategy

| 1. Recognize early warning signs of a crisis: fear, panic, confusion, disorganization, intrusive thoughts, flashbacks/nightmares, self-defeating actions |

| 2. Expect recovery from an acute trauma/crisis within 6 wk; most crises will stabilize or resolve |

| 3. For counselors, normalize that somatic or psychiatric symptoms are common in a crisis, as are disturbances in usual daily routines |

| 4. Discuss problems, symptoms, or dysfunction with family, trusted friends, and other professionals |

| 5. Identify the crisis precipitants (eg, internal/external events) and develop the 6-week timeline |

| 6. Develop the ecological map. List people/organizations in the support system; Who can help? |

| 7. Focus on one main crisis. List the contributing problems. Set the priority and sequence for what needs to change |

| 8. Develop 1 solution per problem |

| 9. Review current coping styles; explore other adaptive coping styles (Table 1) |

| 10. Implement the plan, using new coping styles and use apps, if helpful (Table 2) |

| 11. Follow-up on referrals |

| 12. Assess results. Has problem been resolved? If yes, go to step #1 and tackle new symptom or problem. If no, seek professional help |

CONCLUSIONS

Crisis psychotherapy is a brief solution-focused treatment that may be of particular use during the COVID-19 pandemic and the impending wave of mental health needs associated. It has face validity as a brief, versatile, eclectic (individual or family-focused), solution-oriented, and trauma-informed treatment, which emphasizes the patient’s strengths, problem-solving, restoration of effective coping, adaptation, and use of community and other resources to facilitate a return to daily functioning. Crisis psychotherapy can be adapted during COVID-19 for a single session in an emergency room or for use on a hotline.13 It is also brief psychotherapy (2 to 20 sessions) for COVID-19 patients in crises while on general hospital service, psychiatric inpatient unit, consultation-liaison service, or in an outpatient setting. This article was written to describe this underutilized form of psychotherapy in the hope that others may find this approach valuable during the COVID-19 pandemic and as a coherent and practical form of psychotherapy to be used as a treatment in many other kinds of mental health crises.

Footnotes

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mitchell JT. Bowers CA, Beidel DC, Marks MR. Critical incident stress management: a comprehensive, integrative, systematic, and multi-component program for supporting first responder psychological health. Mental Health Intervention and Treatment of First Responders and Emergency Workers. Hershey, PA: IGI Global; 2020:103–128. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rose SC, Bisson J, Churchill R, et al. Psychological debriefing for preventing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;2:CD000560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. van Emmerik AAP, Kamphuis JH, Hulsbosch AM, et al. Single-session debriefing after psychological trauma: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2002;360:766–771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Vernberg EM, Steinberg AM, Jacobs AK, et al. Innovations in disaster mental health: psychological first aid. Prof Psychol Res Pr. 2008;39:381–388. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Forbes D, Lewis V, Varker T, et al. Psychological first aid following trauma: implementation and evaluation framework for high-risk organizations. Psychiatry. 2011;74:224–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fox JH, Burkle FM, Jr, Bass J, et al. The effectiveness of psychological first aid as a disaster intervention tool: research analysis of peer-reviewed literature from 1990-2010. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2012;6:247–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Feinstein RE, Snavely A. Rakel RE, Rakel DP. Crisis intervention, trauma, and intimate partner violence. Textbook of Family Medicine, 8th edition. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2011:1022–1036. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feinstein RE, Collins E. Rakel R, Rakel D. Crisis intervention, trauma & disasters. Textbook of Family Medicine, 9th edition. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders Company; 2015:1062–1073. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simpson S, Feinstein RE. Crisis intervention in integrated care. In: Feinstein RE, Connelly JV, Feinstein MS, editors. Integrated Behavioral Health & Primary Care. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2017:497–513. [Google Scholar]

- 10. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). Psychiatry Milestones: Patient Care 4 (p. 4). Psychotherapy. Chicago, IL: ACGME; March 2020 Revision. Available at: www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/PsychiatryMilestones2.0.pdf?ver=2020-03-10-152105-537. Accessed September 20, 2020.

- 11. Sternberg RJ. Wisdom: Its Nature, Origins, and Development. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Levitt HM, Piazza-Bonin E. Wisdom and psychotherapy: studying expert therapists’ clinical wisdom to explicate common processes. Psychother Res. 2014;26:31–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Feinstein RE, Kotara S, Jones B, et al. A health care workers mental health crisis line in the age of COVID-19. J Depress Anxiety. 2020;37:822–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yager J, Feinstein RE. Tools for practical psychotherapy: a transtheoretical collection (or interventions which have, at least, worked for us). J Psychiatr Pract. 2017;23:60–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Salmon T. War neurosis (“shell shock”). Milit Surg. 1917;41:674–693. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lindemann E. Symptomatology and management of acute grief. Am J Psychiatry. 1944;101:141–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Erickson E. Childhood and Society, 2nd edition. New York, NY: Norton Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Caplan G. An Approach to Community Mental Health. Orlando, FL: Grune & Stratton; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Caplan G. Principles of Preventative Psychiatry. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Aguilera DC. Crisis Intervention: Theory and Methodology. St Louis, MO: Mosby-Year Book; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Flannery RB, Jr, Everly GS, Jr. Crisis intervention: a review. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2000;2:119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Greenstone JL, Leviton SC. Elements of Crisis Intervention: Crises and How to Respond to Them. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kanel K. A Guide to Crisis Intervention, 2nd edition. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Roberts AR, . Crisis Intervention Handbook: Assessment, Treatment, and Research. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25. James RK, Gilliland BE. Crisis Intervention Strategies, 8th edition. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cavaiola AA, Colford JE. Crisis Intervention: A Practical Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holmes TH, Rahe RH. The Social Readjustment Rating Scale. J Psychosom Res. 1967;11:213–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hobson CJ, Kamen J, Szostek J, et al. Stressful life events: a revision and update of the Social Readjustment Rating Scale. Int J Stress Manag. 1998;5:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 29. McFarlane AC, Williams R. Mental health services required after disasters: learning from the lasting effects of disasters. Depress Res Treat. 2012;2012:970194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Talevi D, Valentina S, Margherita C, et al. Mental health outcomes of the COVID-19 pandemic. Riv Psichiatr. 2020;55:137–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rajkumar RP. COVID-19 and mental health: a review of the existing literature. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;52:102066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the COVID-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:510–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Torous J, Myrick KJ, Rauseo-Ricupero N, et al. Digital mental health and COVID-19: using technology today to accelerate the curve on access and quality tomorrow. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7:18848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Langarizadeh M, Tabatabaei MS, Tavakol K, et al. Telemental health care, an effective alternative to conventional mental care: a systematic review. Acta Inform Med. 2017;25:240–246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Sensenig DJ. Utilizing what we know about tele-mental health in tele-financial planning: a systematic literature review. J Financial Plan. 2020;33:48–58. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Marshall JM, Dunstan DA, Bartik W. The digital psychiatrist: in search of evidence-based apps for anxiety and depression. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:831. 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hootz T, Mykota DB, Fauchoux L. Strength-based crisis programming: evaluating the process of care. Eval Program Plann. 2016;54:50–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Greene RR. Green RR. Ecological perspective; an eclectic theoretical framework for social work practice. Human Behavior Theory and Social Work Practice, 3rd edition. New York, NY: Routledge; 2017:199–236. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bakker D, Kazantzis N, Rickwood D, et al. Mental health smartphone apps: review and evidence-based recommendations for future developments. JMIR Ment Health. 2016;3:e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]