Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Summary:

The health care crisis related to the spread of novel coronavirus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) has created new challenges to plastic surgery education, mostly because of the decreased volume of procedures. The plastic surgery program directors in Chicago decided to act and identify ways to promote surgical education through citywide, multi-institutional, systematic clinical case discussions. Although the initiative has no impact on the surgical skill of the trainees, it was welcomed by residents and faculty and promoted clinical core knowledge in plastic surgery and collaboration among the institutions.

The recent crisis in the health care related to the spread of the novel coronavirus (severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2) has created new challenges and barriers to education worldwide.1 Surgical education in general,2,3 and plastic surgery education specifically, have been greatly affected by the obstacles the pandemic has generated. As elective operations have been postponed to prevent unexpected complications4 and increase the availability of ventilators, hospital personnel, and personnel protective equipment (as mandated by the governor of Illinois5), the volume of plastic surgery procedures performed at the academic institutions in Chicago has declined sharply. In response to this decrease in clinical educational opportunities for plastic surgery residents, regional program directors formed the Chicago Academic Plastic Surgery collaborative and decided to act and identify ways to promote surgical education.

APPROACH

A collaboration among the academic plastic surgery programs located in Chicago was pursued. The plastic surgery program directors of Loyola University, Northwestern University, Rush University Medical Center, University of Chicago, and University of Illinois at Chicago met by means of video conference to identify efficient ways of combining available resources and expertise in an effort to create a multi-institutional education clinical practice curriculum for the plastic surgery residents during the period of the coronavirus disease of 2019 (COVID-19) crisis. A mini-Delphi approach was implemented to reach consensus among the panel of program directors.6 The basic concept of the Delphi process has been described in previous publications.7 This study conforms to the Declaration of Helsinki ethical principles for medical research. The study is exempt from institutional review board approval.

CHICAGO ACADEMIC PLASTIC SURGERY CURRICULUM

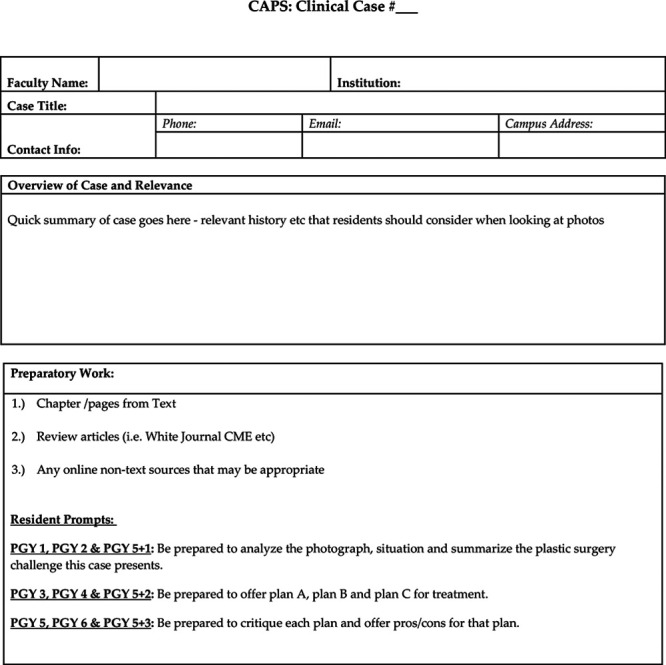

A multi-institutional, case-based, hour-long virtual educational teleconference was developed by Chicago Academic Plastic Surgery faculty for a total of 56 residents (Loyola University, n = 6; Northwestern University, n = 14; Rush University Medical Center, n = 6; University of Chicago, n = 12; and University of Illinois at Chicago, n = 12). All faculty were invited to participate and there was an overwhelming positive response. Students interested in plastic surgery were also welcomed to attend. Two times per week, a specific topic in the field of plastic and reconstructive surgery was chosen and assigned to two faculty moderators from different institutions based on relevant expertise. The two moderators were responsible for identifying an appropriate index case example based on the topic of the week and providing residents a preoperative photograph with a short history and seminal articles related to the topic for the residents to review 48 hours before the conference (Fig. 1). (See Document, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows instructions given to moderators, http://links.lww.com/PRS/E466.)

Fig. 1.

Sample of case submission form.

On the day of the virtual video conference, subgroups of residents organized by their postgraduate level were asked to comment on clinical decisions based on updated information and photographs provided by the moderators. In particular, junior residents, including integrated postgraduate year 1 and 2 and independent year 1 residents, were expected to analyze photographs, describe depicted defects, and identify possible medical and surgical challenges. Midlevel residents, including integrated postgraduate year 3 and 4 and independent YIP II residents, were expected to offer multiple operative options appropriate for the case patient, and comment on surgical techniques. Finally, senior residents consisting of integrated postgraduate year 5 and 6 and independent YIP III residents, were asked to comment on advantages and disadvantages of the methods suggested, materials chosen for reconstruction, and management of complications.

Moderators facilitated discussion and evaluated approaches and pitfalls throughout the process. All residents were required to attend the sessions, unless they had clinical responsibilities, and they were welcome to both ask and answer questions. Special effort was placed to engage as many residents as possible for each case. Finally, the sessions were recorded and made available to the residents for review after the live session.

RECOMMENDATIONS/FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The health care crisis related to COVID-19 has created new challenges for plastic surgery educators and trainees; however, it has also generated some unique opportunities. Trainees were given a rare opportunity of dedicated time for expanding their core knowledge in plastic surgery and performing research. The described Chicago Academic Plastic Surgery initiative focused on promoting the demonstration of the residents’ clinical knowledge. Each resident was able to interact on a weekly basis with residents and expert plastic surgeons from other institutions, promoting collaboration and exchange of opinions. Although this effort has no impact on the surgical skill of the trainees, it was welcomed with excitement by the residents who provided positive feedback to the committee following the completion of the sessions. Faculty members also reported great satisfaction with the process. The positive interaction between faculty members of different academic programs also demonstrates a valuable professional concept of collaboration to the residents—the notion that the rising tide lifts all boats.

We continue to make changes and improve the content and structure of the conference based on well-described quality improvement concepts in plastic surgery.8 As this initiative is expanding, some considerations would be the selection of the most appropriate Web interface used for the video conferences, as charges to the institutions may apply if the number of participants exceeds 100. In addition, we are considering introducing preconference and postconference surveys to evaluate the satisfaction of the residents and faculty with the quality of the discussion and the efficiency of the process. Depending on the results, we may consider continuing the citywide conferences following the lifting of the restrictions enforced by the state, in the post–COVID-19 era. In addition, we are planning to partner with the Illinois Society of Plastic Surgeons to conduct monthly interprogram grand rounds for membership inclusive of all academic plastic surgery program in Illinois and all active members of the Illinois Society of Plastic Surgery.

We recommend similar initiatives for other cities with multiple programs and in partnership with the American Council of Academic Plastic Surgeons and the American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Our experience has shown that expanding and sharing teaching through citywide video conferences are feasible and have been successful in promoting plastic surgery knowledge for our residents.

Footnotes

Related digital media are available in the full-text version of the article on www.PRSJournal.com.

Disclosure: None of the authors has a financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. WHO director-general’s remarks at the media briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- 2.Ahmed H, Allaf M, Elghazaly H. COVID-19 and medical education. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:777–778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sohrabi C, Alsafi Z, O’Neill N, et al. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int J Surg. 2020;76:71–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aminian A, Safari S, Razeghian-Jahromi A, Ghorbani M, Delaney CP. COVID-19 outbreak and surgical practice: Unexpected fatality in perioperative period. Ann Surg. 2020;272:e27–e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Illinois Department of Public Health. COVID-19 elective surgical procedure guidance. Available at: https://www.dph.illinois.gov/topics-services/diseases-and-conditions/diseases-a-z-list/coronavirus/health-care-providers/elective-procedures-guidance. Accessed April 1, 2020.

- 6.Pan SQ, Vega M, Vella AJ, Archer BH, Parlett GR. A mini-Delphi approach: An improvement on single round techniques. Progr Tourism Hosp Res. 1996;2:27–39. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Manage Sci. 1963;9:458–467. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manahan MA, Aston JW, Bello RJ, et al. Establishing a culture of patient safety, quality, and service in plastic surgery: Integrating the fractal model. J Patient Saf. Epublished online ahead of print November 23, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]