Abstract

Background

Major depressive disorders have a significant impact on children and adolescents, including on educational and vocational outcomes, interpersonal relationships, and physical and mental health and well‐being. There is an association between major depressive disorder and suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide. Antidepressant medication is used in moderate to severe depression; there is now a range of newer generations of these medications.

Objectives

To investigate, via network meta‐analysis (NMA), the comparative effectiveness and safety of different newer generation antidepressants in children and adolescents with a diagnosed major depressive disorder (MDD) in terms of depression, functioning, suicide‐related outcomes and other adverse outcomes. The impact of age, treatment duration, baseline severity, and pharmaceutical industry funding was investigated on clinician‐rated depression (CDRS‐R) and suicide‐related outcomes.

Search methods

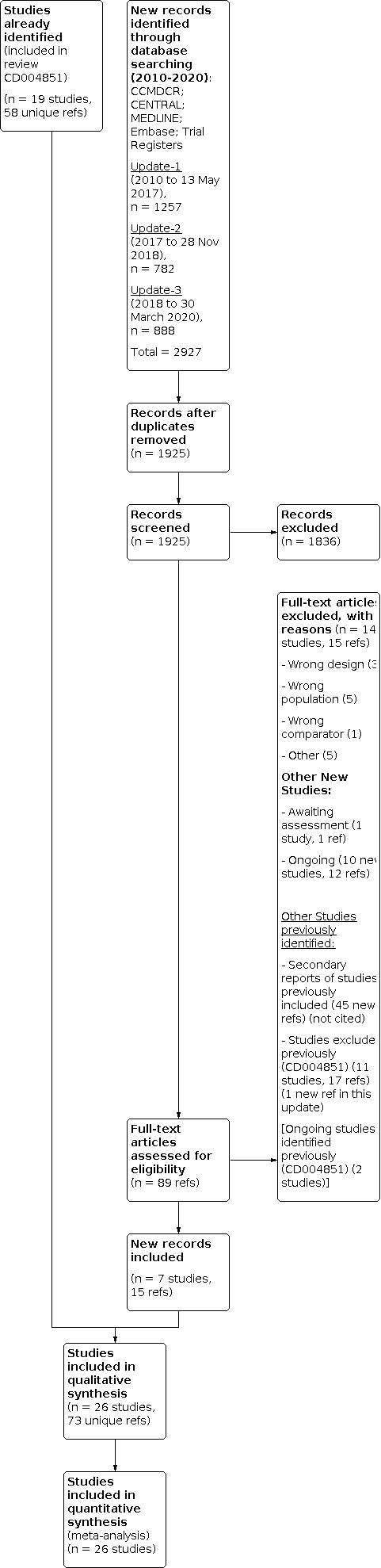

We searched the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Specialised Register, the Cochrane Library (Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR)), together with Ovid Embase, MEDLINE and PsycINFO till March 2020.

Selection criteria

Randomised trials of six to 18 year olds of either sex and any ethnicity with clinically diagnosed major depressive disorder were included. Trials that compared the effectiveness of newer generation antidepressants with each other or with a placebo were included. Newer generation antidepressants included: selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs); norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors; norepinephrine dopamine reuptake inhibitors; norepinephrine dopamine disinhibitors (NDDIs); and tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs).

Data collection and analysis

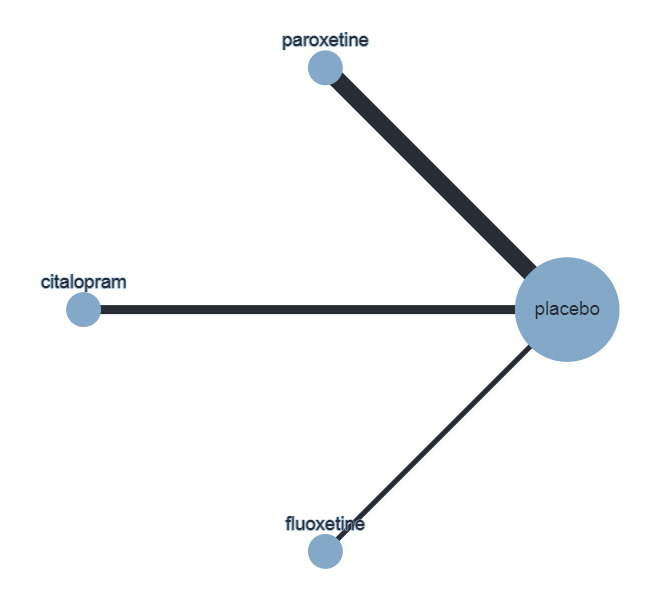

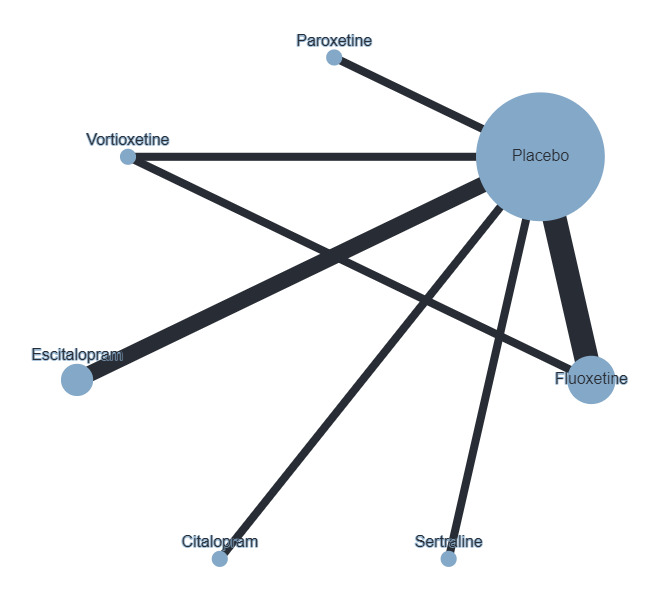

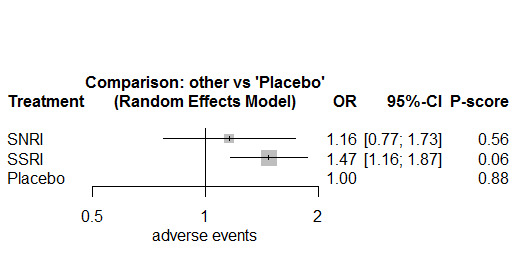

Two reviewers independently screened titles/abstracts and full texts, extracted data, and assessed risk of bias. We analysed dichotomous data as Odds Ratios (ORs), and continuous data as Mean Difference (MD) for the following outcomes: depression symptom severity (clinician rated), response or remission of depression symptoms, depression symptom severity (self‐rated), functioning, suicide related outcomes and overall adverse outcomes. Random‐effects network meta‐analyses were conducted in a frequentist framework using multivariate meta‐analysis. Certainty of evidence was assessed using Confidence in Network Meta‐analysis (CINeMA). We used "informative statements" to standardise the interpretation and description of the results.

Main results

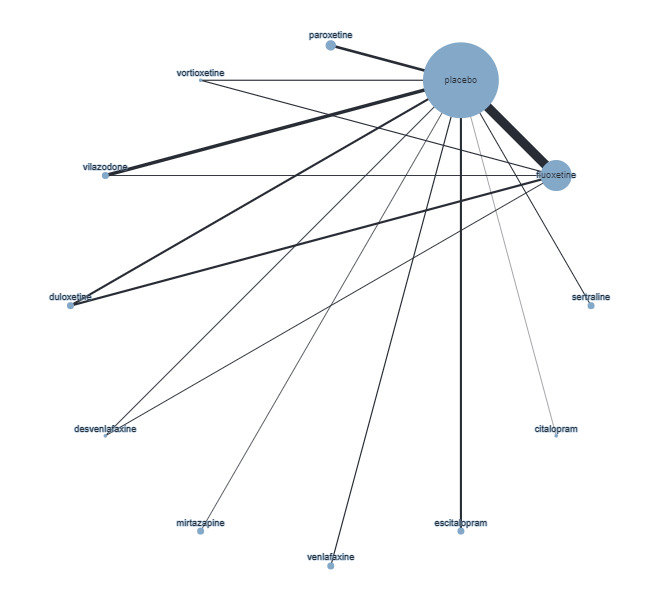

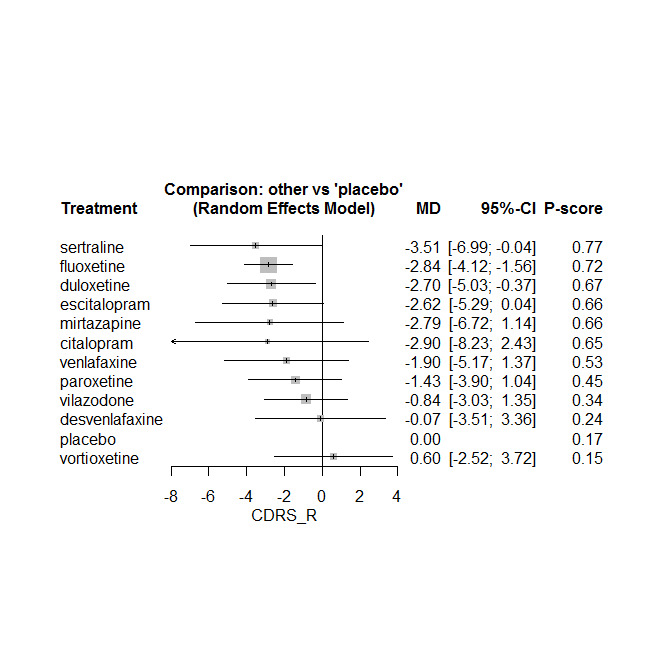

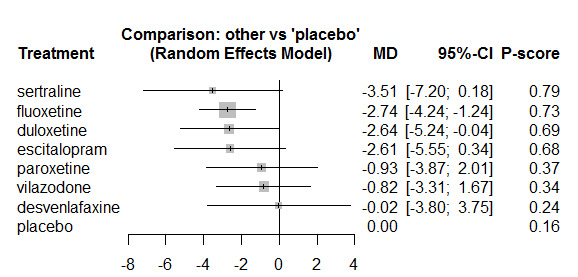

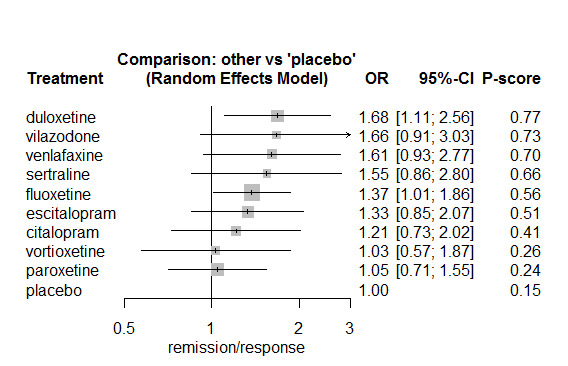

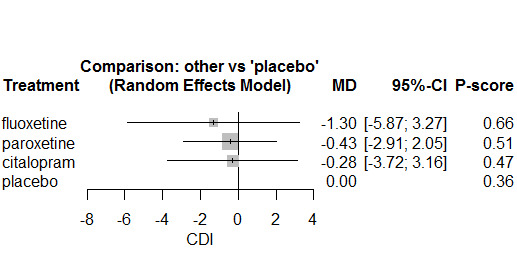

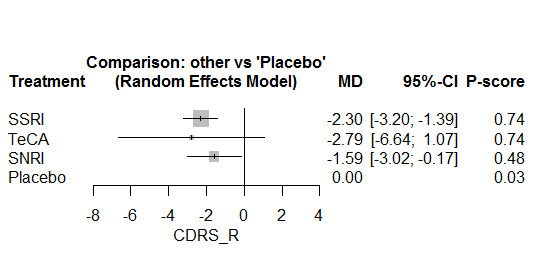

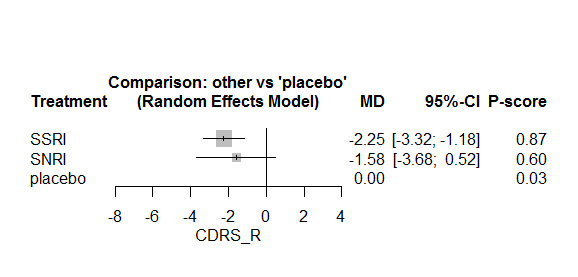

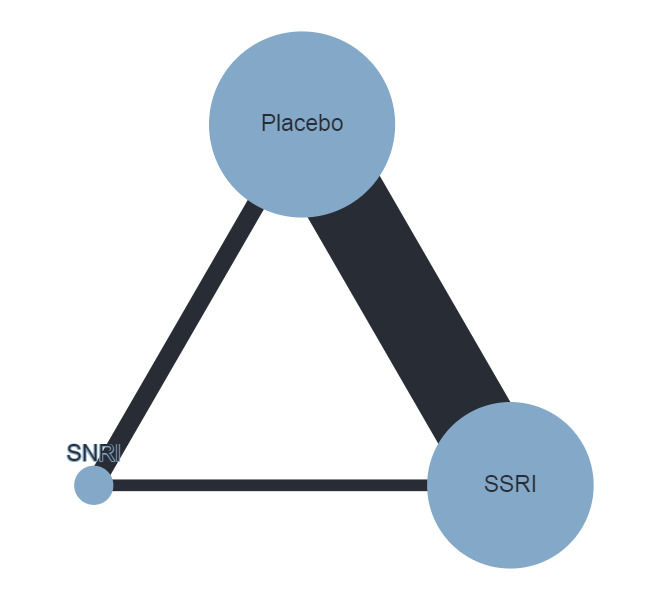

Twenty‐six studies were included. There were no data for the two primary outcomes (depressive disorder established via clinical diagnostic interview and suicide), therefore, the results comprise only secondary outcomes. Most antidepressants may be associated with a "small and unimportant" reduction in depression symptoms on the CDRS‐R scale (range 17 to 113) compared with placebo (high certainty evidence: paroxetine: MD ‐1.43, 95% CI ‐3.90, 1.04; vilazodone: MD ‐0.84, 95% CI ‐3.03, 1.35; desvenlafaxine MD ‐0.07, 95% CI ‐3.51, 3.36; moderate certainty evidence: sertraline: MD ‐3.51, 95% CI ‐6.99, ‐0.04; fluoxetine: MD ‐2.84, 95% CI ‐4.12, ‐1.56; escitalopram: MD ‐2.62, 95% CI ‐5.29, 0.04; low certainty evidence: duloxetine: MD ‐2.70, 95% CI ‐5.03, ‐0.37; vortioxetine: MD 0.60, 95% CI ‐2.52, 3.72; very low certainty evidence for comparisons between other antidepressants and placebo).

There were "small and unimportant" differences between most antidepressants in reduction of depression symptoms (high‐ or moderate‐certainty evidence).

Results were similar across other outcomes of benefit.

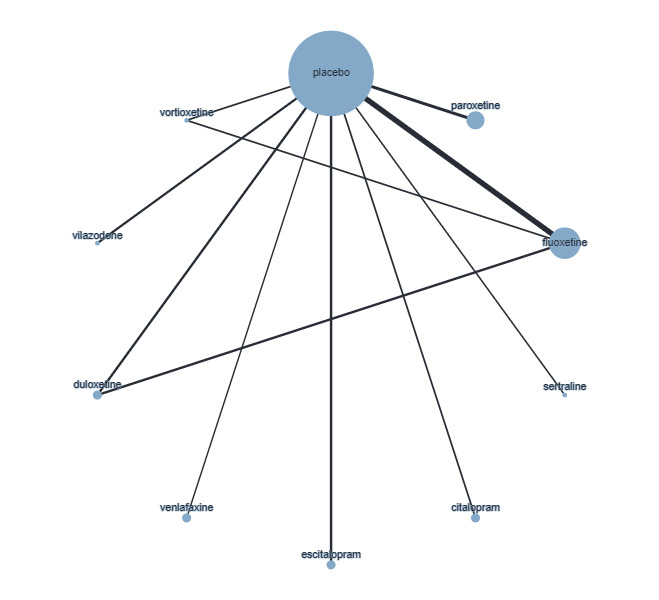

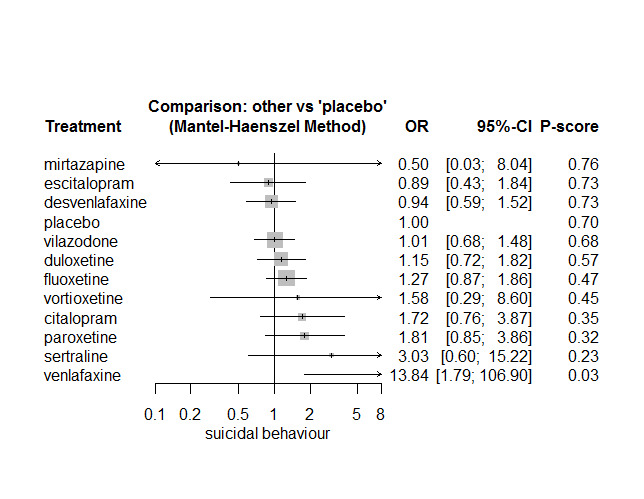

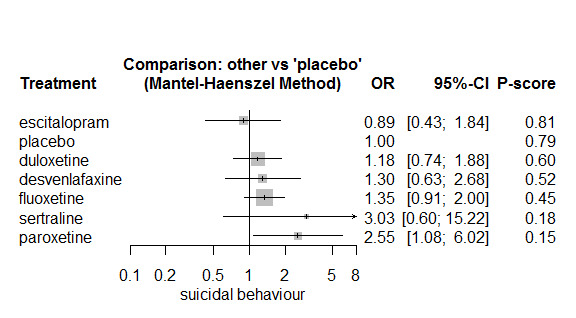

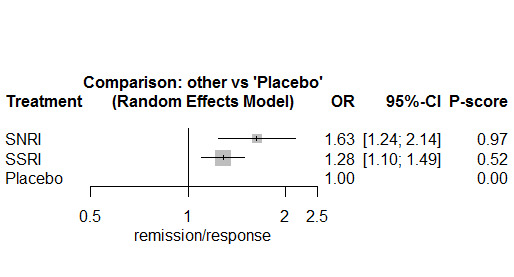

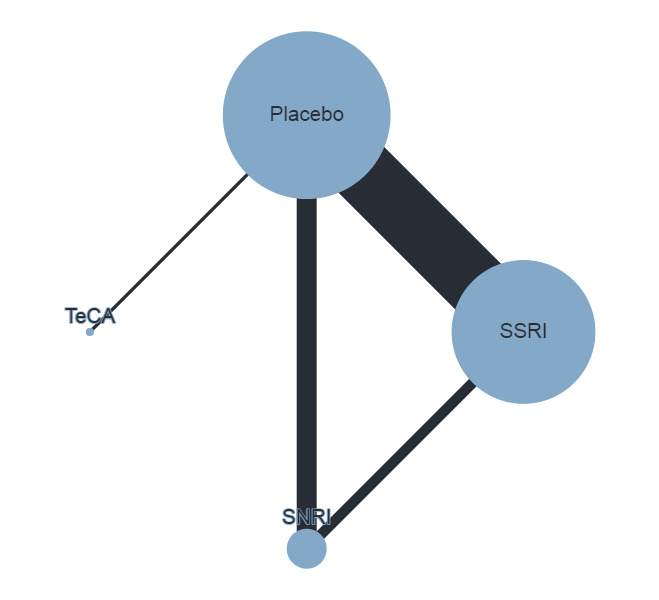

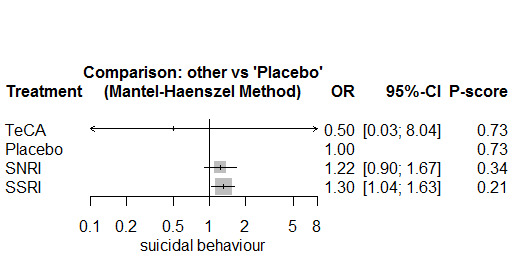

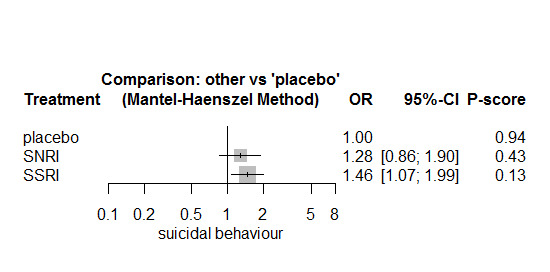

In most studies risk of self‐harm or suicide was an exclusion criterion for the study. Proportions of suicide‐related outcomes were low for most included studies and 95% confidence intervals were wide for all comparisons. The evidence is very uncertain about the effects of mirtazapine (OR 0.50, 95% CI 0.03, 8.04), duloxetine (OR 1.15, 95% CI 0.72, 1.82), vilazodone (OR 1.01, 95% CI 0.68, 1.48), desvenlafaxine (OR 0.94, 95% CI 0.59, 1.52), citalopram (OR 1.72, 95% CI 0.76, 3.87) or vortioxetine (OR 1.58, 95% CI 0.29, 8.60) on suicide‐related outcomes compared with placebo. There is low certainty evidence that escitalopram may "at least slightly" reduce odds of suicide‐related outcomes compared with placebo (OR 0.89, 95% CI 0.43, 1.84). There is low certainty evidence that fluoxetine (OR 1.27, 95% CI 0.87, 1.86), paroxetine (OR 1.81, 95% CI 0.85, 3.86), sertraline (OR 3.03, 95% CI 0.60, 15.22), and venlafaxine (OR 13.84, 95% CI 1.79, 106.90) may "at least slightly" increase odds of suicide‐related outcomes compared with placebo.

There is moderate certainty evidence that venlafaxine probably results in an "at least slightly" increased odds of suicide‐related outcomes compared with desvenlafaxine (OR 0.07, 95% CI 0.01, 0.56) and escitalopram (OR 0.06, 95% CI 0.01, 0.56). There was very low certainty evidence regarding other comparisons between antidepressants.

Authors' conclusions

Overall, methodological shortcomings of the randomised trials make it difficult to interpret the findings with regard to the efficacy and safety of newer antidepressant medications. Findings suggest that most newer antidepressants may reduce depression symptoms in a small and unimportant way compared with placebo. Furthermore, there are likely to be small and unimportant differences in the reduction of depression symptoms between the majority of antidepressants. However, our findings reflect the average effects of the antidepressants, and given depression is a heterogeneous condition, some individuals may experience a greater response. Guideline developers and others making recommendations might therefore consider whether a recommendation for the use of newer generation antidepressants is warranted for some individuals in some circumstances. Our findings suggest sertraline, escitalopram, duloxetine, as well as fluoxetine (which is currently the only treatment recommended for first‐line prescribing) could be considered as a first option.

Children and adolescents considered at risk of suicide were frequently excluded from trials, so that we cannot be confident about the effects of these medications for these individuals. If an antidepressant is being considered for an individual, this should be done in consultation with the child/adolescent and their family/caregivers and it remains critical to ensure close monitoring of treatment effects and suicide‐related outcomes (combined suicidal ideation and suicide attempt) in those treated with newer generation antidepressants, given findings that some of these medications may be associated with greater odds of these events. Consideration of psychotherapy, particularly cognitive behavioural therapy, as per guideline recommendations, remains important.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Female; Humans; Male; Antidepressive Agents; Antidepressive Agents/adverse effects; Antidepressive Agents/therapeutic use; Bias; Citalopram; Citalopram/therapeutic use; Depressive Disorder, Major; Depressive Disorder, Major/drug therapy; Depressive Disorder, Major/psychology; Desvenlafaxine Succinate; Desvenlafaxine Succinate/therapeutic use; Duloxetine Hydrochloride; Duloxetine Hydrochloride/therapeutic use; Fluoxetine; Fluoxetine/therapeutic use; Mirtazapine; Mirtazapine/therapeutic use; Paroxetine; Paroxetine/therapeutic use; Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors; Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors/therapeutic use; Sertraline; Sertraline/therapeutic use; Suicidal Ideation; Venlafaxine Hydrochloride; Venlafaxine Hydrochloride/therapeutic use; Vilazodone Hydrochloride; Vilazodone Hydrochloride/therapeutic use; Vortioxetine; Vortioxetine/therapeutic use

Plain language summary

Newer generation antidepressants for depression in children and adolescents: a network meta‐analysis

How well do newer formulations of antidepressants work for children and adolescents with clinical depression?

Children and adolescents (6 to 18 years) with depression (also called ‘major depressive disorder’) experience a range of negative impacts in all areas of their lives and have an increased risk of suicide, suicidal thinking and suicide attempts. Antidepressants have been shown to reduce symptoms of depression, but can also increase the risk of suicide‐related outcomes.

Who will be interested in this research?

The research in this Cochrane Review will interest:

‐ people who decide policy, and influence decisions about the prescription of antidepressant medicines to children and adolescents;

‐ people who prescribe these medicines to children and adolescents;

‐ children and adolescents with depression; and

‐ those who support and care for them (including their parents and caregivers and clinicians who provide treatment).

What did we want to find out?

We wanted to find out how well newer formulations (called ‘new generation’) antidepressants work to improve depression in children and adolescents aged 6 to 18 years. New generation antidepressants are those that have been developed recently. They are sometimes referred to as ‘second‐‘ and ‘third‐generation’ antidepressants; they do not include older formulations (tricyclic antidepressants or monoamine oxidase inhibitors).

We wanted to know how these antidepressants affect:

‐ symptoms of depression;

‐ recovery: no longer meeting diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder;

‐ response or remission: scores on a scale indicating an important reduction in depression or no longer experiencing depression;

‐ ability to function in daily life;

‐ suicide‐related outcomes; and

‐ whether they cause any unwanted effects in children and adolescents.

What did we do?

We searched for studies that tested new generation antidepressants on children or adolescents (or both) who had been diagnosed with a major depressive disorder. We identified 26 such studies. We then assessed the trustworthiness of those studies, and synthesized the findings across the studies.

What does the evidence from the review tell us?

Most newer antidepressants probably reduce depression symptoms better than a placebo (a 'dummy' treatment that does not contain any medicine but looks identical to the medicine being tested). However, the reduction is small and may not be experienced as important by children and adolescents, their parents and caregivers, or clinicians. When different medications are compared against each other, there may be only small and unimportant differences between most of them for the reduction of symptoms.

Our findings reflect what happens on average to individuals, but some individuals may experience a greater response. This might lead to recommendations being made for the use of antidepressants for some individuals in some circumstances. Our findings suggest that sertraline, escitalopram, duloxetine and fluoxetine can be used if medication is being considered.

The impact of medication on depression symptoms should be closely monitored by those prescribing the medication, especially as suicide‐related thinking and behaviour may be increased in those taking these medications. Close monitoring of suicide‐related behaviours is vital in those treated with new generation antidepressants.

What should happen next?

The studies that provided this evidence largely excluded children and adolescents who:

‐ were already thinking about suicide and wanting to take their own lives (i.e. had suicidal ideation);

‐ were self‐harming;

‐ had other mental health conditions; and

‐ had psychosocial difficulties.

Future research should aim to understand the impacts of these medicines in children and adolescents with these problems, who are more typical of those who request clinical services.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Summary of findings table comparing individual antidepressants on clinician‐rated depression symptoms (CDSR‐R).

| BENEFITS | ||||||

| Population: children and/or adolescents with depression | ||||||

| Interventions: new generation antidepressants including SSRIs (e.g. fluoxetine), SNRIs (e.g. duloxetine), and TeCAs (e.g. mirtazapine) | ||||||

| Comparator: other new generation antidepressant | ||||||

| Outcome: clinician‐rated depression symptoms (CDRS‐R) | ||||||

| Setting: primary care, community settings, specialist settings | ||||||

| Anticipated absolute effect (95% CI) | ||||||

|

Total studies: 22 Total participants: 5750 |

MD on CDRS‐R (95% CI) |

Without intervention | With intervention | Certainty of evidence | Ranking (P value) | Interpretation |

| fluoxetine:desvenlafaxine | ‐2.77 (‐6.20, 0.66) | ‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to imprecision2 |

0.72 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| fluoxetine:duloxetine | ‐0.14 (‐2.46, 2.19) | ‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to incoherence4 |

0.67 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| fluoxetine:vilazodone | ‐2.00 (‐4.40, 0.41) | ‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to heterogeneity5 |

0.72 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| fluoxetine:vortioxetine | ‐3.44 (‐6.56, ‐0.33) |

‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias3, heterogeneity5 |

0.72 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| citalopram:desvenlafaxine | ‐2.83 (‐9.16, 3.51) | ‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias1, imprecision,2 |

0.65 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| duloxetine:citalopram | 0.20 (‐5.62, 6.01) |

‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,3 imprecision7 |

0.67 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| escitalopram:citalopram | 0.28 (‐5.68, 6.23) | ‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,3 imprecision7 |

0.66 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| fluoxetine:citalopram | 0.06 (‐5.42, 5.54) | ‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,3 imprecision7 |

0.72 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| mirtazapine:citalopram | 0.11 (‐6.51, 6.73) |

‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,3 imprecision7 |

0.66 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| citalopram:paroxetine | ‐1.47 (‐7.34, 4.40) | ‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision,2 heterogeneity5 |

0.65 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| sertraline:citalopram | ‐0.61 (‐6.97, 5.74) |

‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision7 |

0.77 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| citalopram:venlafaxine | ‐1.00 (‐7.25, 5.25) |

‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,3 imprecision7 |

0.65 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| citalopram:vilazodone | ‐2.06 (‐7.82, 3.70) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision2 |

0.65 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| citalopram:vortioxetine | ‐3.50 (‐9.67, 2.67) |

‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,3 imprecision2 |

0.65 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| duloxetine:desvenlafaxine | ‐2.63 (‐6.68, 1.42) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to imprecision2 |

0.67 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| escitalopram:desvenlafaxine | ‐2.55 (‐6.89, 1.80) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to imprecision2 |

0.66 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| mirtazapine:desvenlafaxine | ‐2.71 (‐7.93, 2.51) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low Due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision2 |

0.66 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| paroxetine:desvenlafaxine | ‐1.35 (‐5.58, 2.87) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to imprecision2 |

0.45 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| sertraline:desvenlafaxine | ‐3.44 (‐8.32, 1.44) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to imprecision2 |

0.77 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| venlafaxine:desvenlafaxine | ‐1.83 (‐6.57, 2.91) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision2 |

0.53 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| vilazodone:desvenlafaxine | ‐0.77 (‐4.80, 3.26) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate Due to heterogeneity5 |

0.34 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| desvenlafaxine:vortioxetine | ‐0.68 (‐5.22, 3.87) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision2 |

0.24 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| duloxetine: escitalopram | ‐0.08 (‐3.62, 3.46) |

‐ | ‐ | High | 0.67 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| duloxetine:mirtazapine | 0.08 (‐4.49, 4.65) |

‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,1heterogeneity6 |

0.67 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| duloxetine:paroxetine | ‐1.27 (‐4.67, 2.12) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to heterogeneity5 |

0.67 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| sertraline:duloxetine | ‐0.81 (‐4.99, 3.37) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to heterogeneity5 |

0.77 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| duloxetine:venlafaxine | ‐0.80 (‐4.82, 3.21) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1heterogeneity5 |

0.67 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| duloxetine:vilazodone | ‐1.86 (‐5.01, 1.29) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to imprecision2 |

0.67 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| duloxetine:vortioxetine | ‐3.30 (‐7.09, 0.48) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision2 |

0.67 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| fluoxetine:escitalopram | ‐0.22 (‐3.18, 2.74) |

‐ | ‐ | High | 0.72 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| escitalopram:mirtazapine | 0.17 (‐4.58, 4.92) |

‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,1heterogeneity6 |

0.66 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| escitalopram:paroxetine | ‐1.19 (‐4.83, 2.44) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to heterogeneity5 |

0.66 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| sertraline:escitalopram | ‐0.89 (‐5.27, 3.48) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to imprecision2 |

0.77 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| escitalopram:venlafaxine | ‐0.72 (‐4.94, 3.50) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1heterogeneity5 |

0.66 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| escitalopram:vilazodone | ‐1.78 (‐5.23, 1.67) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to imprecision2 |

0.66 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| escitalopram:vortioxetine | ‐3.22 (‐7.32, 0.88) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision2 |

0.66 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| fluoxetine:mirtazapine | ‐0.05 (‐4.19, 4.08) |

‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,1heterogeneity6 |

0.72 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| fluoxetine:paroxetine | ‐1.41 (‐4.20, 1.37) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to heterogeneity5 |

0.72 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| sertraline:fluoxetine | ‐0.67 (‐4.37, 3.03) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to heterogeneity5 |

0.77 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| fluoxetine:venlafaxine | ‐0.94 (‐4.45, 2.57) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1heterogeneity5 |

0.72 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| mirtazapine:paroxetine | ‐1.36 (‐6.00, 3.28) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision2 |

0.66 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| sertraline:mirtazapine | ‐0.73 (‐5.97, 4.52) |

‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision,2 heterogeneity5 |

0.77 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| mirtazapine:venlafaxine | ‐0.89 (‐6.00, 4.23) |

‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,3 imprecision,2 heterogeneity5 |

0.66 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| mirtazapine:vilazodone | ‐1.94 (‐6.44, 2.56) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision2 |

0.66 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| mirtazapine:vortioxetine | ‐3.39 (‐8.41, 1.63) |

‐ | ‐ |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,3 imprecision2 |

0.66 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| sertraline:paroxetine | ‐2.09 (‐6.35, 2.17) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to imprecision2 |

0.77 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| venlafaxine:paroxetine | ‐0.47 (‐4.57, 3.62) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1heterogeneity5 |

0.53 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| paroxetine:vilazodone | ‐0.58 (‐3.89, 2.72) |

‐ | ‐ | High | 0.45 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| paroxetine:vortioxetine | ‐2.03 (‐6.01, 1.95) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision2 |

0.45 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| sertraline:venlafaxine | ‐1.61 (‐6.38, 3.15) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision2 |

0.77 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| sertraline:vilazodone | ‐2.67 (‐6.78, 1.43) |

‐ | ‐ |

Moderate due to imprecision2 |

0.77 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| sertraline:vortioxetine | ‐4.12 (‐8.78, 0.55) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision2 |

0.77 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| venlafaxine:vilazodone | ‐1.06 (‐4.99, 2.88) |

‐ | ‐ |

Low due to within‐study bias,1heterogeneity5 |

0.53 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R |

| venlafaxine:vortioxetine | ‐2.50 (‐7.02, 2.02) |

Very Low due to within‐study bias,3 imprecision2 |

0.53 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R | ||

| vilazodone:vortioxetine | ‐1.44 (‐5.21, 2.32) |

Low due to within‐study bias,1 imprecision2 |

0.34 | We proposed an equivalence range of ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R | ||

MD = mean difference, CI = confidence interval, PI = prediction interval

1. studies were at moderate risk of bias based on weighted average percentage contribution to effect estimate

2. 95% CI crossed equivalence range (MD ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R)

3. studies were at high risk of bias based on weighted average percentage contribution to effect estimate

4. potential inconsistency between direct and indirect evidence (but inconclusive due to limited direct evidence)

5. 95% PI crossed equivalence range (MD ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R)

6. 95% PI crossed equivalence range in both directions (MD ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R)

7. 95% CI crossed equivalence range in both directions (MD ‐5, 5 points on the CDRS‐R)

Summary of findings 2. Summary of findings table comparing individual antidepressants on suicidal behaviour.

| HARMS | ||||||

| Population: children and/or adolescents with depression | ||||||

| Interventions: new generation antidepressants including SSRIs (e.g. fluoxetine), SNRIs (e.g. duloxetine), and TeCAs (e.g. mirtazapine ) | ||||||

| Comparator: placebo or other new generation antidepressant | ||||||

| Outcome: suicidal behaviour according to the Columbia Classification system, e.g. suicidal ideation, suicide attempt | ||||||

| Setting: primary care, community settings, specialist settings | ||||||

| Anticipated Absolute effects (95% CI) | ||||||

|

Total studies: 21 RCTs Total participants: 6413 |

Assumed comparator risk per 1000 | Corresponding intervention risk per 1000 |

Relative effect: OR (95% CI) |

Certainty of evidence | Ranking (P value) | Interpretation |

| desvenlafaxine:fluoxetine | 82.6 | 62.47 (38.11, 102.61) |

0.74 (0.44, 1.27) |

Low due to imprecision1 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| duloxetine:fluoxetine | 82.6 | 74.96 (48.82,114.77) |

0.9 (0.57,1.44) |

Very Low due to imprecision, 1incoherence8 |

0.57 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| vilazodone:fluoxetine | 82.6 | 67.19 (39.77, 109.81) |

0.8 (0.46,1.37) |

Very low due to imprecision,1and within‐study bias2 |

0.68 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| fluoxetine:vortioxetine | 16.2 | 13.00 (2.46,64.54) |

0.8 (0.15,4.19) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias3 |

0.47 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| desvenlafaxine:citalopram | 70.1 | 39.81 (15.58,96.08) |

0.55 (0.21,1.41) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| duloxetine:citalopram | 70.1 | 48.08 (19.22,113.60) |

0.67 (0.26,1.7) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.57 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| escitalopram:citalopram | 70.1 | 37.72 (12.65, 104.02) |

0.52 (0.17,1.54) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| fluoxetine:citalopram | 70.1 | 52.84 (22.12, 120.06) |

0.74 (0.30,1.81) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.47 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| mirtazapine:citalopram | 70.1 | 21.39 (1.51, 283.94) |

0.29 (0.02,5.26) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias3 |

0.76 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| citalopram:paroxetine | 26.9 | 25.59 (8.50, 73.98) |

0.95 (0.31,2.89) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.35 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| citalopram:sertraline | 31.7 | 18.32 (2.94, 101.48) |

0.57 (0.09,3.45) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.35 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| citalopram:venlafaxine | 70.7 | 9.05 (0.76, 78.52) |

0.12 (0.01,1.12) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias3 |

0.35 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| vilazodone:citalopram | 70.1 | 42.58 (17.77, 97.92) |

0.59 (0.24,1.44) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias3 |

0.68 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| vortioxetine:citalopram | 70.1 | 64.86 (10.44, 312.51) |

0.92 (0.14,6.03) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.45 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| desvenlafaxine:duloxetine | 134.5 | 113.03 (64.00, 194.12) |

0.82 (0.44,1.55) |

Low due to imprecision1 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| escitalopram:desvenlafaxine | 127.45 | 120.73 (55.20,246.53) |

0.94 (0.4,2.24) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| mirtazapine:desvenlafaxine | 127.45 | 71.85 (4.36, 564.11) |

0.53 (0.03,8.86) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.76 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| desvenlafaxine:paroxetine | 26.9 | 14.17 (5.77,34.17) |

0.52 (0.21,1.28) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| desvenlafaxine:sertraline | 31.7 | 10.05 (1.96,51.84) |

0.31 (0.06,1.67) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| desvenlafaxine:venlafaxine | 70.7 | 5.30 (0.76, 40.86) |

0.07 (0.01,0.56) |

Moderate due to within‐study bias2 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| desvenlafaxine:vilazodone | 167.7 | 159.24 (93.18, 257.37) |

0.94 (0.51,1.72) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| desvenlafaxine:vortioxetine | 16.2 | 9.78 (1.81, 52.87) |

0.6 (0.11,3.39) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| escitalopram:duloxetine | 134.5 | 108.11 (48.78, 222.36) |

0.78 (0.33,1.84) |

Low due to imprecision1 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| mirtazapine:duloxetine | 134.5 | 62.64 (4.64,531.49) |

0.43 (0.03,7.30) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.76 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| duloxetine:paroxetine | 26.9 | 17.12 (7.14, 40.83) |

0.63 (0.26,1.54) |

Low due to imprecision1 |

0.57 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| duloxetine:sertraline | 31.7 | 12.29 (2.29, 62.03) |

0.38 (0.07,2.02) |

Low due to imprecision1 |

0.57 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| duloxetine:venlafaxine | 70.7 | 6.05 (0.76, 48.50) |

0.08 (0.01,0.67) |

Low due to within‐study bias2 and heterogeneity4 |

0.57 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| vilazodone:duloxetine | 134.5 | 120.30 (69.41,200.13) |

0.88 (0.48,1.61) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.68 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| duloxetine:vortioxetine | 16.2 | 11.72 (2.14,62.23) |

0.72 (0.13,4.03) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.57 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| escitalopram:fluoxetine | 82.6 | 59.29 (27.15, 125.23) |

0.7 (0.31,1.59) |

Low due to imprecision1 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| mirtazapine:escitalopram | 49.25 | 28.19 (1.55, 339.44) |

0.56 (0.03,9.92) |

Very low due to imprecision,1 and within‐study bias2 |

0.76 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| escitalopram:paroxetine | 26.9 | 13.36 (4.68,37.52) |

0.49 (0.17,1.41) |

Low due to imprecision1 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| escitalopram:sertraline | 31.7 | 9.40 (1.63, 53.31) |

0.29 (0.05,1.72) |

Low due to imprecision1 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| escitalopram:venlafaxine | 70.7 | 4.54 (0.76,40.86) |

0.06 (0.01,0.56) |

Moderate due to within‐study bias2 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| escitalopram:vilazodone | 167.7 | 150.61 (72.86, 288.25) |

0.88 (0.39,2.01) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| escitalopram:vortioxetine | 16.2 | 9.14 (1.48, 55.38) |

0.56 (0.09,3.56) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| mirtazapine:fluoxetine | 82.6 | 33.92 (1.80, 369.54) |

0.39 (0.02,6.51) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.76 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| fluoxetine:paroxetine | 26.9 | 18.98 (8.22, 43.37) |

0.7 (0.3,1.64) |

Low due to imprecision1 |

0.47 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| fluoxetine:sertraline | 31.7 | 13.56 (2.61,66.90) |

0.42 (0.08,2.19) |

Low due to imprecision1 |

0.47 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| fluoxetine:venlafaxine | 70.7 | 6.80 (0.76, 52.62) |

0.09 (0.01,0.73) |

Very Low due to within‐study bias2 and heterogeneity5 |

0.47 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| mirtazapine:paroxetine | 26.9 | 7.68 (0.55, 119.94) |

0.28 (0.02,4.93) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.76 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| mirtazapine:sertraline | 31.7 | 5.21 (0.33, 118.09) |

0.16 (0.01,4.09) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.76 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| mirtazapine:venlafaxine | 70.7 | 3.03 (0.76, 79.81) |

0.04 (0.01,1.14) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias3 |

0.76 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| mirtazapine:vilazodone | 167.7 | 89.86 (6.01, 622.67) |

0.49 (0.03,8.19) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias3 |

0.76 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| mirtazapine:vortioxetine | 16.2 | 5.08 (0.16,118.84) |

0.31 (0.01,8.19) |

Very Low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.76 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| paroxetine:sertraline | 31.7 | 19.26 (3.26, 103.86) |

0.6 (0.1,3.54) |

Low due to imprecision1 |

0.32 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| paroxetine:venlafaxine | 70.7 | 9.79 (0.76,81.09) |

0.13 (0.01,1.16) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.32 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| vilazodone:paroxetine | 26.9 | 15.24 (6.59, 34.95) |

0.56 (0.24,1.31) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.68 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| vortioxetine:paroxetine | 26.9 | 23.49 (3.86, 134.05) |

0.87 (0.14,5.6) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.45 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| sertraline:venlafaxine | 70.7 | 16.46 (1.52,183.80) |

0.22 (0.02,2.96) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.23 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| vilazodone:sertraline | 31.7 | 10.69 (1.96, 54.19) |

0.33 (0.06,1.75) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.68 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| vortioxetine:sertraline | 31.7 | 16.74 (1.63,150.46) |

0.52 (0.05,5.41) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.45 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| vilazodone:venlafaxine | 70.7 | 5.30 (0.76, 42.26) |

0.07 (0.01,0.58) |

Low due to within‐study bias3 |

0.68 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| vortioxetine:venlafaxine | 70.7 | 8.30 (0.76,110.33) |

0.11 (0.01,1.63) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.45 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| vilazodone:vortioxetine | 16.2 | 10.43 (1.81, 56.40) |

0.64 (0.11,3.63) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.68 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| citalopram:placebo | 37.3 | 62.48 (28.60, 130.39) |

1.72 (0.76, 3.87) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias3 |

0.35 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| desvenlafaxine:placebo | 37.3 | 35.14 (22.35, 55.62) |

0.94 (0.59, 1.52) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| duloxetine:placebo | 37.3 | 42.66 (27.14, 65.87) |

1.15 (0.72, 1.82) |

Very low due to imprecision,1 and incoherence6 |

0.57 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| escitalopram:placebo | 37.3 | 33.33 (16.39, 66.55) |

0.89 (0.43, 1.84) |

Low due to imprecision1 |

0.73 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| fluoxetine:placebo | 37.3 | 46.90 (32.61, 67.22) |

1.27 (0.87, 1.86) |

Low due to heterogeneity,4 imprecision7 |

0.47 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| mirtazapine:placebo | 37.3 | 19.00 (1.16, 237.52) |

0.50 (0.03, 8.04) |

Very low due to imprecision,1and within‐study bias3 |

0.76 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| paroxetine:placebo | 37.3 | 65.53 (31.88, 130.10) |

1.81 (0.85, 3.86) |

Low due to imprecision1 |

0.32 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| sertraline:placebo | 37.3 | 105.06 (22.72, 370.95) |

3.03 (0.60, 15.22) |

Low due to imprecision1 |

0.23 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| venlafaxine:placebo | 37.3 | 349.06 (64.86, 805.52) |

13.84 (1.79, 106.90) |

Low due to within‐study bias3 |

0.03 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| vilazodone:placebo | 37.3 | 37.66 (25.67, 54.23) |

1.01 (0.68, 1.48) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias3 |

0.68 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

| vortioxetine:placebo | 37.3 | 57.69 (11.11, 249.93) |

1.58 (0.29, 8.60) |

Very low due to imprecision1, and within‐study bias2 |

0.45 | equivalence range from OR 0.90, 1.12 |

CI = confidence interval, PI = prediction interval, OR = odds ratio

1. 95% CI crossed equivalence range (OR = 0.90, 1.12) in both directions

2. studies were at moderate risk of bias based on weighted average percentage contribution to effect estimate

3. studies were at high risk of bias based on weighted average percentage contribution to effect estimate

4. 95% PI crossed equivalence range (OR = 0.90, 1.12)

5. 95% PI crossed equivalence range (OR = 0.90, 1.12) in both directions

6. minor differences between direct and indirect evidence

7. 95% CI crossed equivalence range (OR = 0.90, 1,12)

8. minor differences between direct and indirect evidence

Background

Description of the condition

'Major depression' is a category of mental health disorder within both of the two major international classification systems: the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM‐5) of the American Psychological Association (APA 2013); and the International Classification of Diseases from the World Health Organisation (WHO 1992; WHO 2019). According to the DSM‐5, the core features of major depression are persistent low mood and loss of enjoyment in once‐pleasurable activities, which are accompanied by a range of other symptoms including weight or appetite changes, inability to sleep or sleeping too much, psychomotor agitation or retardation (feeling restless, sluggish, loss of energy), inappropriate guilt or feelings of worthlessness, poor concentration and thoughts of death or suicide (APA 2000; APA 2013). Criteria differences for children and adolescents include the presence of irritability as an alternative to a depressed mood, in acknowledgement that depression in this age group often features irritability and can be characterised by mood fluctuations that are highly dependent on — or reactive to — circumstances (Thapar 2012). It has also been noted that depression in this age group can be characterised by comorbid anxiety, school refusal, social withdrawal, unexplained physical symptoms, decline in academic performance, substance misuse and behaviour problems (Thapar 2012; Maughan 2013). The presence of other psychiatric disorders is also common (Angold 1999; Maughan 2013).

Meta‐analytic estimates of prevalence of depression suggest rates of 2.8% (95% confidence interval (CI) 1.8 to 3.8) in children, and 5.7% (95% CI 5.1% to 6.3%) in adolescents (Costello 2006). By the age of 19 years, around 25% of adolescents are estimated to have experienced a depressive episode (Lewinsohn 1998; Kessler 2001), and one longitudinal study of a general population sample showed that by the age of 30, 53% of people in the cohort had experienced a major depressive episode at some point over their lifetime since the age of five years (Rhode 2013). Overall, these data indicate that many people across the lifespan are affected by depression. Approximately 25% of cases of the onset of major depression has occurred by the age of 19 years (Kessler 2005). During adolescence, twice as many girls as boys experience depression (Hyde 2008). Previous studies, including both community‐ and clinic‐based longitudinal cohort and case‐control studies have shown that in those experiencing adolescent‐onset depression, there is a high risk of a recurrence of depression in adulthood (Harrington 1990; Lewinsohn 1998; Weissman 1999; Dunn 2006; Fergusson 2007).

The impact of depression can be significant. In a large study of adults with depression who were being treated in a clinic setting, the earlier the age of onset, the more likely were there to be social and occupational difficulties, poor quality of life, and greater physical and mental health problems, more episodes of depression over their lifetime and more attempts of suicide (Zisook 2007). These types of impacts have again been shown in a prospective population‐based cohort study showing that children and adolescents who experienced depression had significantly increased odds of poor educational outcome, mental health and substance use problems, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, criminal convictions, teenage parenthood, physical health problems, untimely death, and social isolation, even when childhood adversity such as the experience of abuse and the presence of psychiatric disorder as a young adult were controlled for (Copeland 2015). A review by Cash 2009 summarised various studies examining the association between depression and suicide and suicide attempt (for example, psychological autopsy studies summarised in this review) showed that approximately 60% of young people who die by suicide had a diagnosis of depression at the time of their death, and that 40% to 80% of adolescents who attempt suicide have depression (Cash 2009). Early longitudinal studies, summarised in this same review (Cash 2009), showed that up to 32% of children and adolescents with depression who were followed through to late adolescence and up to the age of 31 years attempted suicide, and between 2.5% and 3.3% had died by suicide (Cash 2009). A longitudinal study of a large birth cohort has shown that the more depressive episodes experienced in adolescence and young adulthood, the worse the outcomes in adulthood in terms of suicidal ideation and attempts, depression, anxiety, welfare dependence and unemployment (Fergusson 2007). Overall, it has been estimated that depression causes more disability for young people (aged 10 to 24 years in the 2004 WHO Global Burden of Disease study) than any other illness (Gore 2011).

Description of the intervention

Antidepressant medication is recommended for those children and adolescents with moderate to severe depression when there has been an inadequate response to psychotherapy (NICE 2019). While it is recommended that antidepressant treatment should happen alongside concurrent psychotherapy, provision is also made for antidepressant monotherapy (NICE 2019). Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), the mainstay of treatment in the past, have not been shown to be an effective pharmacological treatment for depression in young people (Weller 2000; Hazell 2002). This has meant that newer generation antidepressants have been increasingly used over the last 20 years (Vitiello 2006; John 2016), with initial studies suggesting they were well tolerated (Cooper 1988). Reviews of efficacy have shown modest effects of these antidepressants over the last two decades (e.g. Hetrick 2007; Hetrick 2012; Locher 2017) and have also raised concerns about the increased risk of suicide attempt and suicidal ideation (collectively referred to as suicide‐related behaviour; Dubicka 2006; Hammad 2006; Hetrick 2007; Hetrick 2012).

This review has included second and third generation antidepressants, which together are referred to as 'newer generation' antidepressants. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are sometimes referred to as 'second generation' antidepressants. In addition to SSRIs, several other classes of antidepressants are now being used, including selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs), norepinephrine‐dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), norepinephrine‐dopamine disinhibitors (NDDIs) and tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs). These newer additional classes are sometimes referred to as 'third generation' antidepressants. Rather than being a homogenous group based on mechanisms of action, however, third generation antidepressants are classed together because they are modified versions of first and second generation antidepressants (Olver 2001).

How the intervention might work

Depressive symptoms were first linked to an underlying depletion in monoamines, notably serotonin, noradrenaline and possibly dopamine in the central nervous system over 50 years ago, with evidence that monoamine‐depleting medications could precipitate depressive symptoms, while agents that increase their levels in the brain have been shown to alleviate depressive symptoms (Delgado 2000). In line with the recommendations for adults, SSRIs are considered first‐line treatment for adolescents, partly because the noradrenergic system matures later than the serotonergic system, potentially explaining observed differences in response to antidepressants by children and adolescents compared with adults (Cousins 2015).

Most antidepressant medications target monoamine transmitter function (Harmer 2017), with increases in synaptic concentrations of serotonin and noradrenaline, although the onset of the chemical effect, which is within hours, is much faster than the clinical effect, which can take days or weeks. The delayed onset of action of the medications has led to research in the following three main areas (Harmer 2017).

1. Neurochemical theories

Initial research focused on the down‐regulation of post‐synaptic β‐adrenoceptors by first generation tricyclic and monoamine oxidase inhibitor antidepressants. With the advent of SSRIs, researchers focused on the initial inhibition of the reuptake of serotonin (5‐hydroxytryptamine, or 5‐HT) (Lenox 2008) which was shown, over time, to reduce sensitivity of 5‐HT auto‐receptors and was postulated to be linked to the delayed clinical effect (Castrén 2005).

2. Neuroplasticity theories

A greater understanding of pathways that regulate neuronal function has led to research that moves beyond the impact on receptor function to a greater focus on intracellular mechanisms, gene expression and protein translation as possible mediators of antidepressant action. Neuroplasticity, or the ability of the nervous system to react and adapt to environmental stimuli, appears to underpin both depression and the action of antidepressants. Synaptic plasticity is reduced by chronic stress, with a reduction in the number and function of synapses particularly in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus. Stress also decreases the formation of neurons in the hippocampus. Depressive disorder is associated with a decrease in volume in key areas in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus (Price 2010; MacQueen 2011). Brain‐derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) is postulated to be a transducer of some of these effects (Björkholm 2016). BDNF has been shown to play a key role in the formation and survival of neurons and to increase synaptic plasticity. It has been shown to be decreased in 'stress in animal' studies and in post‐mortem studies of humans with depression. Longer‐term use of SSRIs has been shown to increase BDNF expression, to increase synaptic plasticity and to block stress‐related synaptic deficits (Castrén 2014; Castrén 2017).

3. Cognitive neuropsychological approaches

A negative affective bias, with differential attention to negative rather than positive stimuli, has been shown to be related to depressive symptoms. Antidepressant medications have been shown to decrease the negative attentional bias; for example, SSRIs reduce the response to negative facial expressions in the amygdala, both in the short and long term (Murphy 2009). It is postulated that the later impact on depressive symptoms may be dependent on an interaction with the environment, so that habitual negative responses to cues in the environment are re‐learnt within a more positive cognitive frame. Links between these processes and synaptic plasticity remain unclear (Harmer 2017).

Recent research on rapidly acting antidepressants such as ketamine has lent weight to some of the neurochemical and neuroplasticity theories (Harmer 2017). However, it is important to recognise that while there is progress in understanding the underlying mechanisms of antidepressant medications, further elucidation is needed. Integrating the work from different schools of thought will be needed to develop new and more effective treatments.

Why it is important to do this review

Evidence‐based guideline‐recommended treatments for depression in young people include psychotherapy (cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT)) as well as SSRIs (fluoxetine, in the first instance) (e.g. AACAP 2007; McDermott 2011; Cheung 2018; NICE 2019). The modest effects of all guideline‐recommended treatments has been the focus of many reviews over the last two decades (e.g. Weersing 2006; Weisz 2006; Locher 2017), including the Cochrane Review of antidepressants for children and adolescents (Hetrick 2007; Hetrick 2012). However, concerns about the increased risk of suicide, suicide attempt and suicidal ideation (collectively referred to as suicide‐related behaviour) for those administered SSRIs were first raised in 2003 (Healy 2003). Meta‐analyses examining the risks of suicide‐related behaviour have shown a consistent and modest increased risk for those taking SSRIs compared with placebo (Dubicka 2006; Hammad 2006). The evidence about these risks has led to action by regulatory bodies: the Committee on Safety of Medicines/Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (CSM/MHRA) in the UK (CSM 2004; MHRA 2014), the European Medicines Agency (EMA 2005), and the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA 2018) have all cautioned practitioners on the use of SSRIs in children and adolescents, including an FDA 'black box' warning label issued on 14 September 2004, which notifies healthcare providers of this evidence of an increased risk of suicide‐related behaviour (FDA 2018). The impact of these actions by regulatory bodies and reactions to it in the media is unclear, with some early evidence of reduced prescriptions (Gibbons 2007; Lu 2014) and more recent evidence suggesting ongoing increases in antidepressant prescribing (Plöderl 2019; Whitely 2020).

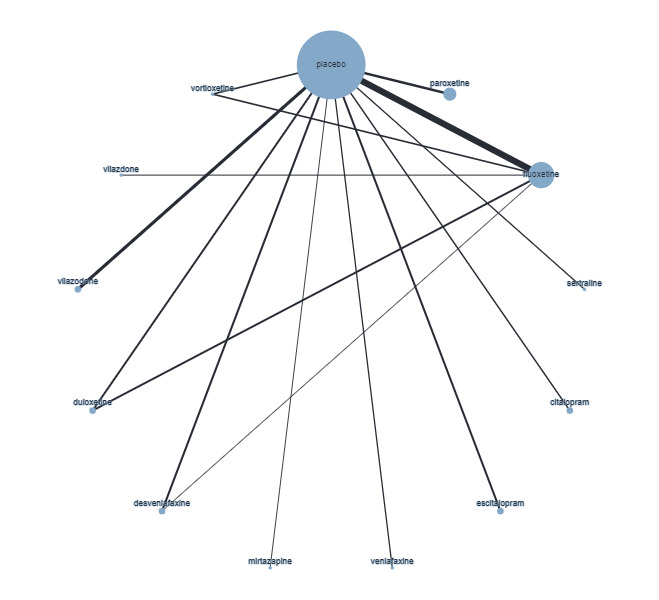

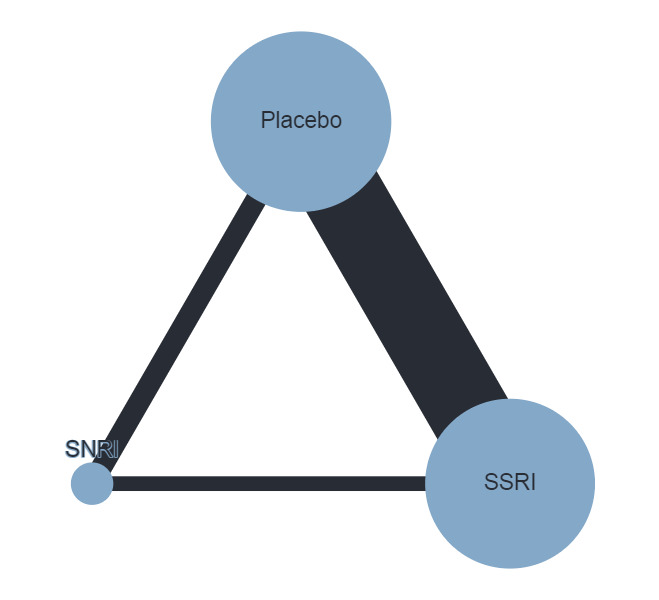

The use of medications, and in particular fluoxetine, is still recommended in guidelines (AACAP 2007; NICE 2019); however, continuing concerns about the efficacy and safety of these treatments warrant an update to the Hetrick 2007 and Hetrick 2012 Cochrane Reviews of antidepressants for children and adolescents, ensuring the inclusion of trials of all recently available newer generation antidepressants, and investigating, using network meta‐analysis (NMA), comparative effectiveness and safety outcomes. NMA combines all available direct and indirect evidence on relative intervention effects to allow effect estimates for all comparisons, even when head‐to‐head trials are not available, as is the case for this class of medications for child and adolescent depression.

Objectives

To investigate, via network meta‐analysis (NMA), the comparative effectiveness and safety of different newer generation antidepressants in children and adolescents with a diagnosed major depressive disorder (MDD). Specific objectives, in order of priority, are to:

estimate the relative effects of newer generation antidepressants compared with placebo and with each other, on depression, functioning, suicide‐related outcomes and other adverse outcomes;

estimate the relative ranking of the included newer generation antidepressants for the outcomes of depression, functioning, suicide‐related outcomes and other adverse outcomes; and,

examine whether the relative effects on clinician‐rated depression symptoms and suicide‐related outcomes estimated in objectives 1 and 2 are modified by age, treatment duration, baseline severity and pharmaceutical industry funding of the antidepressant under evaluation.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

All variants of randomised trials (RTs) were eligible for inclusion in the review (e.g. individually randomised, cross‐over, cluster trials). However, we only included the first period data (if possible) in cross‐over trials in which there was less than one week's washout because, in this circumstance, there is a serious risk of carry‐over effects arising from the effects of the first‐period antidepressant persisting into subsequent period(s) (Hosenbocus 2011). We did not include trials in which the treatment assignment was decided through a deterministic method, such as alternate days of the week. Similarly, non‐randomised designs to examine the effects of antidepressants on adverse effects were not included. No language restrictions were used. We included both published and unpublished trial data and reports.

Types of participants

Participant characteristics

Trials involving children and adolescents aged six to 18 years old of either sex and any ethnicity were included. Trials where both adults and children/adolescents were treated were eligible for inclusion, as long as data on the children/adolescents were available separately or by obtaining data from the trial authors where randomisation was maintained; however, no such trials were included.

Diagnosis

Trials that focused on the acute phase treatment of clinically diagnosed major depressive disorder (MDD) were included.

Trials that adopted any standardised diagnostic criteria to define participants suffering from an acute phase unipolar depressive disorder were included. Accepted diagnostic criteria included DSM‐III (APA 1980), DSM‐III‐R (APA 1987), DSM‐IV (APA 1994), DSM‐IV‐TR (APA 2000), DSM‐5 (APA 2013) or ICD‐9 or ICD‐10 (WHO 1992; WHO 2019).

Trials that focused on treatment‐resistant depression, including those where participants were receiving treatment to prevent relapse following a depressive episode (that is, where participants were not depressed at study entry), were excluded.

Trials involving people described as 'at risk of suicide' or with dysthymia or other affective disorders such as panic disorder have been included in this review as long as participants met criteria for major depression as stated above.

Comorbidities

Trials that included participants with comorbid conditions secondary to a depressive disorder were included in this review.

Setting

In this review, studies conducted in primary care and community‐based settings, or in secondary or specialist settings, including inpatient settings, and including referrals as well as volunteers, have been included. Similarly, studies focused on specific populations, for example, school refusal or suicide risk, were also eligible for inclusion if the participants all met the criteria for major depression.

Types of interventions

We developed criteria for inclusion in consideration of the transitivity assumption, such that there was sufficient clinical and methodological comparability across the planned comparisons in this NMA. All included interventions are part of the same broad class and therefore have been considered to be legitimate alternatives (i.e. they are equally likely and able to be randomised).

Trials that compared the effectiveness of newer generation antidepressants with each other or with a placebo have been included. The antidepressants formed the 'decision set' of treatments — that is, the treatments that are of direct interest for clinical decision‐making. The 'supplementary set' of treatments included placebo and no treatment. Although understanding the effectiveness of these treatments is not directly relevant to clinical practice, since many of the trials compare antidepressants to placebo, their inclusion in the network provides important indirect evidence that helps evaluate clinically relevant medications (i.e. the 'decision set') with greater precision (Hetrick 2012).

The antidepressants included in this review are those consistent with the medications included in the equivalent Cochrane Common Mental Disorders (CCMD) Group Meta‐Analysis of New Generation Antidepressants (MANGA) reviews for adult depressive disorders (Cipriani 2005; Cipriani 2007; Imperadore 2007; Nosè 2007; Nakagawa 2009; Cipriani 2009a; Cipriani 2009b; Churchill 2010; Cipriani 2010; Guaiana 2010; Omori 2010; Watanabe 2011). The set of antidepressants, grouped according to class, included:

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs): fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, sertraline, paroxetine, escitalopram, citalopram, alaproclate, vilazodone, vortioxetine;

selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs): venlafaxine, duloxetine, desvenlafaxine, milnacipran, levomilnacipran, edivoxetine;

norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs): reboxetine;

norepinephrine dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs): bupropion;

norepinephrine dopamine disinhibitors (NDDIs): agomelatine;

tetracyclic antidepressants (TeCAs): mirtazapine.

We applied no restrictions on the dose or pattern of administration of included antidepressants. The antidepressants have been grouped for the syntheses to ensure a high degree of similarity within a group (node), in terms of the class, specific antidepressant and dose.

Trials where newer‐generation antidepressants were used in combination with a co‐intervention (e.g. the YoDA‐C trial where fluoxetine and CBT were compared with placebo and CBT; Davey 2019) were not eligible for inclusion. Trials with multiple comparison arms have been included but only data from relevant treatment arms has been extracted (e.g. the Treatment for Adolescent Depression‐TADS trial; TADS 2004).

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1. Depressive disorder according to DSM or ICD criteria and established by a clinician conducting a structured or semi‐structured diagnostic interview such as the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Aged Children, Present Episode Version (K‐SADS‐P) (Chambers 1985). We chose this as the most robust approach to establishing the resolution of a depressive episode.

2. Death by suicide established via recording of this adverse outcome within the trial period or by medical record or direct inquiry with appropriate contact person at follow‐up.

Secondary outcomes

1. Efficacy outcomes

1.1 Depression symptom severity (clinician‐rated) using the Children's Depression Rating Scale (CDRS‐R)

The CDRS‐R was adapted for children and adolescents from the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM‐D), a tool validated and commonly used in adult populations (Brooks 2001). Early reviews indicated that both the CDRS‐R and HAM‐D have good reliability and validity (Brooks 2001). The Montgomery‐Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) was also based on the HAM‐D but designed to better assess sensitivity to change. It was not, however, designed specifically for children and adolescents (Brooks 2001). More recent evidence suggests that the psychometric properties of the CDRS mean its ability to meaningfully measure depression severity may be limited (Stallwood 2021). Nevertheless, this outcome was chosen due to its consistency of use across trials (the most commonly used tool in the previous version of this review (Appendix 1)).

1.2. Remission or response as defined by trialists

Response and remission are separate constructs for which distinct consensus definitions (related to a severity‐based and temporal criterion) have been agreed: response is an initial improvement of symptoms, usually after treatment initiation and usually attributable to the treatment. After three weeks of minimal symptoms, a patient can be said to have entered remission (Frank 1991; Rush 2006), As published specifically in relation to children and adolescents, response has been defined as there being no symptoms or a significant reduction in depressive symptoms for at least two weeks and remission as a period of at least two weeks and more than two months with no or few depressive symptoms (Birmaher 2007).

While these constructs are distinct, the way they are defined and operationalised is inconsistent across trials in this field. Typically, 'remission' and 'response' are defined by dichotomising a continuous measure of clinician‐rated depression symptoms. The labelling of remission and response varied across trials in the previous versions of this review (Hetrick 2007; Hetrick 2012), with the labelling being different even though the cut‐points were the same. In the previous versions of this review, for consistency across trials, we chose the most commonly reported cut‐point: CDRS‐R less than or equal to 28, which was generally referred to as 'remission'. When 'remission' was not reported, we used 'response', if available. An exception to this rule was: if remission was only available from observed case (OC) data but response data were available from 'last‐observation‐carried‐forward' (LOCF) data, we used response data (see 'Dealing with missing data'). We have taken the same approach in this review. We have chosen to include both continuous and dichotomised measures of clinician‐rated depression symptoms, since there are advantages and disadvantages to each. Responder analyses (based on the dichotomised continuous outcomes) are well known to be problematic (Kieser 2004), with arbitrariness in the choice of cut‐point, loss of power resulting from the dichotomisation (Altman 2006), and difficulties in interpretation (as outlined above). However, synthesising continuous outcomes is not without its difficulties. The scales used to measure depression symptoms vary across trials: there is inconsistency in the analytical methods employed (e.g. analyses of change scores, regression models), which can preclude the use of the standardised mean difference; and there are also interpretational difficulties.

1.3 Depression symptom severity ‒ self‐rated (on standardised, validated, reliable depression rating scales)

The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)/Children's Depression Inventory (CDI) were the most commonly used across trials in Hetrick 2012, the previous version of this review, and ranked the highest in the hierarchy (see Appendix 1); therefore, we have undertaken meta‐analyses of this outcome measured by either scale (BDI for preference if both are used), with results based on other scales reported in tables.

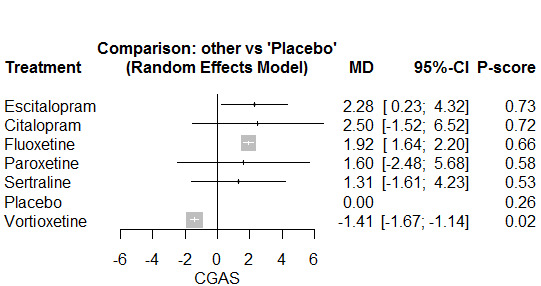

1.4 Functioning (on standardised, validated, reliable global functioning rating scales)

The Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) was the most commonly used in the previous version of this review and, therefore, has been used for meta‐analyses of this outcome, with results based on other scales reported in tables.

2. Suicide‐related outcomes

Where possible, we have chosen data based on the definitions used in the FDA review using the Columbia Classification system, e.g. suicidal ideation, suicide attempt (Hammad 2004), based on the previous version of this review.

3. Overall adverse outcomes

Experience of any adverse event.

Timing of outcome assessment

Our primary outcome was measured post‐intervention (i.e. at completion of the treatment). We have chosen this follow‐up time (post‐intervention) based on our previous review (Hetrick 2012), where all trials primarily measured the post‐intervention outcomes. However, recognising that longer‐term time frames are clinically more meaningful for antidepressant treatments, we have also collected all available outcomes and classified them into short‐term (one to six months) and long‐term (> six months) follow‐up categories. Where multiple outcomes per category were available, we selected the outcome with the longest follow‐up (e.g. in the short‐term category, outcomes measured at six months were selected in preference to outcomes at three months).

Search methods for identification of studies

We identified eligible studies (RCTs) of antidepressants for depression in children and adolescents from the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders Controlled Trials Register (CCMDCTR; all years to 2016) (Appendix 2).

Electronic searches

We conducted supplementary searches on the following bibliographic databases using relevant subject headings (controlled vocabularies) and search syntax, appropriate for each resource (Appendix 3):

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; Issue 3 of 12, 2020) in the Cochrane Library;

MEDLINE Ovid (2016 to March 30, 2020);

Embase Ovid (2016 to 2020 Week 13);

PsycINFO Ovid (2016 to March Week 4 2020).

No restrictions on language or publication status were applied to the searches.

3. International registries

International trial registries via the World Health Organization's trials portal (ICTRP) and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched to identify unpublished or ongoing studies.

4. Searches already completed

We had already conducted searches up to October 2011 for other direct comparison reviews (Hetrick 2007; Hetrick 2012) (Appendix 4).

Searching other resources

Grey literature

We searched sources of grey literature including theses, clinical guidelines and reports from regulatory agencies.

Handsearching

Conference abstracts for the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry were searched (2003 to 2005) for the original review. For this update, we now searched for these via Embase.

Reference lists

We checked the reference lists of all included studies and relevant systematic reviews to identify additional studies missed from the original electronic searches (for example unpublished or in‐press citations).

Correspondence

We contacted trialists and subject experts for information on unpublished or ongoing studies or to request additional trial data.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

We considered trials from the previous reviews to already be included (Hetrick 2007; Hetrick 2012); they had been independently screened for inclusion by two review authors (MS and GC). For trials identified from the updated search, two of five review authors (PB, AB, SH, CM, GC) independently assessed the titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria.

Where a title or abstract appeared to describe a trial eligible for inclusion, we obtained the full article to assess whether it met the inclusion criteria. Where peer‐reviewed academic publications of trials were not available, the process was to obtain the trial registry report and then identify further reports that were available on this basis. Pairs of review authors resolved disagreements in screening decisions at each stage of screening through discussion, or if necessary by consultation with a third review author. We have reported the reasons for exclusion of trials in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' section.

Data extraction and management

For the 2012 update of the review, two review authors (SH and GC) independently extracted information on each trial, including 'Risk of bias' criteria, details about the trial and outcome data.

For this version of the review, two of five review authors (AB, PB, CM, GC, VS) independently extracted information on newly included trials, including 'Risk of bias' criteria and details of participants, interventions, comparisons, potential effect modifiers (see Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity), outcomes and results. A third review author (SH or NM) resolved disagreements. Where there were multiple reports on one trial and discrepancies between these, we typically relied on the clinical trial reports but would resolve these by discussion between those authors extracting the data. We have reported trial characteristics in the 'Characteristics of included studies' tables. These data formed the basis for discussing the internal and external validity (directness) of results.

When estimates of treatment effect or standard errors were not directly reported, we calculated these, where possible, through algebraic manipulation of available statistics (e.g. means, confidence interval limits, exact P values).

For the previous versions of the review we decided post hoc to extract suicide‐related outcomes from the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) rather than from the individual trial reports retrieved in the search. The MHRA has produced a web‐based report (www.mhra.gov.uk) that summarises the results of the majority of the trials included in the original review (Hetrick 2007). We used two additional reports: one on suicide‐related outcomes (Hammad 2004); and one on trial characteristics (Dubitsky 2004). These gave details of outcomes for 25 SSRI trials, both based on data submitted to the FDA. For this review, we again used data from these reports of suicide‐related outcomes, where it was available; and where it was not, we extracted data from the trial reports using, where possible, outcomes with a similar definition of 'suicide‐related', as defined in the above stated reports.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

In the original review (Hetrick 2007), we assessed the risk of bias of the included randomised trials using the quality of trials ratings devised by Moncrieff and colleagues (Moncrieff 2001). For the 2012 update, we used the first version of Cochrane's 'Risk‐of‐bias' tool and have again used this version for this update (Higgins 2009).

We assessed the following domains:

Random sequence generation

Allocation concealment

Blinding of participants and personnel

Blinding of outcome assessment

Incomplete outcome data

Selective outcome reporting

Other bias

We judged each domain as having a 'high', 'low' or 'unclear risk of bias' and have provided a supporting quotation from the study report together with a justification for our judgement in the 'Risk of bias' table. We considered blinding separately for different outcomes, where necessary (e.g. the risk of bias resulting from unblinded outcome assessment for an objective outcome, such as 'death by suicide', may differ from a subjective outcome, such as self‐reported depression). Where information on risk of bias related to unpublished data or correspondence with a trialist, we noted this in the 'Risk of bias' table. We classified the overall risk of bias for each trial into three categories based on all domains except 'Other'. These categories are: 'low risk of bias', where all domains are judged to be at a low risk of bias; 'some concerns', where at least one domain is rated at an unclear risk of bias and all other domains are rated at a low risk of bias; and 'high risk of bias', where at least one domain is rated at a high risk of bias.

Two of five review authors (AB, CM, VS, GC, SH) independently assessed the risk of bias for each trial newly included in this update. We resolved any uncertainties or disagreements by discussion or by involving another author (JM or NM).

Measures of treatment effect

Relative treatment effects

Dichotomous data

For dichotomous outcomes, we measured treatment effects using odds ratios (ORs) (e.g. remission rates and adverse effects, measured as a count of any adverse event).

Continuous data

For continuous outcomes (such as clinician‐rated depression symptom severity), we use the mean difference (MD). In the majority of trials, multiple linear regression models were fitted, and ‘covariate‐adjusted’ estimates of treatment effects from these models were reported (often as least square means or least square mean differences) (Hetrick 2007; Hetrick 2012). These models adjusted for varying factors such as age, sex, investigator site and baseline of the outcome. We had not planned and did not use the standardised mean difference (SMD) (often used where the same outcome domain is measured across trials, but using different measurement scales) because of the inconsistency in the analytical methods employed across trials (e.g. analyses of final values, change scores and regression models).

Relative treatment rankings

We estimated P‐scores (Rucker 2015), which measure the certainty that a particular treatment is more effective than competing treatments.

Unit of analysis issues

Cluster‐randomised trials

No cluster‐RCTs were included. If they had been, but had not appropriately adjusted for the correlation between participant outcomes within clusters, we would have contacted trial authors to obtain an estimate of the intra‐cluster correlation (ICC), or imputed the ICC using estimates from the other included trials or from similar external trials. We would have inflated the reported standard errors by the square root of the design effect, using the estimated/imputed ICC (Higgins 2019), and undertaken sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the combined intervention effects to assumptions regarding the ICCs.

Cross‐over trials

No cross‐over trials were included. If we had included cross‐over trials, and the appropriate data from a paired analysis were not available and we could not obtain them from trial authors, we would have imputed missing statistics (e.g. missing standard deviation, correlation) using data available from other trials included within the meta‐analysis, or trials outside the meta‐analysis (Elbourne 2002; Higgins 2019). We would have used sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the pooled treatment effect to assumptions made regarding missing statistics.

Studies with multiple treatment groups

We undertook adjustment for multi‐arm trials in the network meta‐analyses using standard methods that account for between‐arm correlations using multivariate meta‐regression models (White 2012).

Dealing with missing data

In the original and 2012 review (Hetrick 2007; Hetrick 2012), we sought additional data from the principal authors and pharmaceutical companies of trials (the latter approached by the Cochrane Common Mental Disorders group on our behalf, who also approached the National Institutes for Mental Health (NIMH) in the case of the Treatment for Adolescent Depression Study; March 2004) where the data were missing, or were in a form unsuitable for meta‐analysis. We also searched the pharmaceutical company websites for additional data on included trials.

In the original and 2012 review (Hetrick 2007; Hetrick 2012), most trials used the 'last‐observation‐carried‐forward' (LOCF) method of data imputation for the majority of outcomes: that is, the last observed value for a participant lost to follow‐up was assigned as the follow‐up value. We chose to pool LOCF data and other data derived via newer imputation methods like Mixed Effect Model Repeated Measure (rather than mix LOCF and OC data) but also undertook sensitivity analysis using OC data, where available. We have used the same approach in this review because estimates of treatment effect based on either LOCF or OC data can result in serious bias (Sterne 2009).

We contacted investigators or study sponsors in order to verify key study characteristics and obtain missing numerical outcome data, where necessary and possible (e.g. when a study was identified as abstract only). We documented all correspondence with trialists and reported which trialists responded.

As was our approach in the previous reviews (Hetrick 2007; Hetrick 2012), where least squares means and their standard errors were reported from regression models by treatment group, but no contrast between groups was reported, we estimated the variance of the treatment effect by summing the square of the standard errors in each treatment group. There may be some inaccuracy in this approach when there is imbalance in the covariates being adjusted for.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed inconsistency between direct and indirect sources of evidence in several steps. First, we assessed the distribution of potential effect modifiers across treatment comparisons based on an examination of participant, intervention and methodological characteristics. Second, we conducted a global test of inconsistency using the design‐by‐treatment interaction model (Higgins 2012). Third, where there was evidence of potential inconsistency, we investigated this using side splitting in netmeta in R (Rucker 2012).

For each network, we assumed a common between‐trial heterogeneity variance of the relative treatment effects for every treatment comparison. We reported these variance estimates.

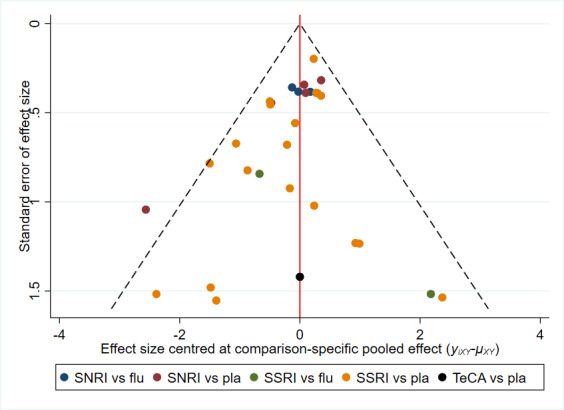

Assessment of reporting biases

There is currently no tool available to assess the risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis. However, a framework has been proposed in which an assessment is made for each comparison regarding i) the risk and potential impact of missing results from studies (termed 'known‐unknowns'), and ii) the risk of missing studies (termed 'unknown‐unknowns') (Page 2019). We have used this framework to guide our assessments of whether there was 'undetected' or 'suspected' reporting bias for each of the comparisons in our GRADE assessment ('Summary of findings' tables).

In assessing i), we have considered our 'Risk of bias' judgement for the 'selective outcome reporting' domain since in the first version of the 'Risk of bias' tool (Higgins 2009), this captures not only selective reporting of results, but also missing results (i.e. arising from non‐reporting of outcomes or incomplete reporting of results for inclusion in a meta‐analysis). For ii), we have considered qualitative signals; and used statistical methods to visualise and model the impact of small‐study effects. As a qualitative signal, we considered the potential for reporting bias (specifically lag‐time bias) for any newly developed antidepressants that have only been evaluated in a small number of trials (Page 2019).