Introduction:

Early administration of systemic corticosteroids for asthma exacerbations in children is associated with improved outcomes. Implementation of a new emergency medical services (EMS) protocol guiding the administration of systemic corticosteroids for pediatric patients with asthma exacerbations went into effect in January 2016 in Southwest Ohio. Our SMART aim was to increase the proportion of children receiving systemic prehospital corticosteroids for asthma exacerbations from 0% to 70% over 2 years.

Methods:

Key drivers were derived and tested using multiple plan-do-study-act cycles. Interventions included community EMS outreach and education, improved clarity in the prehospital protocol language, distribution of pocket-sized educational cards, and ongoing individualized EMS agency feedback on protocol adherence. Eligible patients included children age 3–16 years, who were transported by EMS to the pediatric emergency department with diagnoses consistent with asthma exacerbation. Manual chart review assessed eligibility to receive prehospital corticosteroids. Statistical process control charts tracked adherence to corticosteroid recommendations.

Results:

A total of 256 encounters met the criteria for receiving prehospital corticosteroids for pediatric asthma exacerbations between January 1, 2016, and April 30, 2019. Special cause variation was demonstrated following education at high-volume EMS stations, and the centerline shifted to 34%. This shift has been sustained for 28 months.

Conclusion:

Improvement methodology increased prehospital corticosteroid administration for pediatric asthma exacerbations, although we failed to achieve our aim of increasing use to 70%. Many barriers exist in pediatric prehospital protocol implementation, many of which can be improved with quality improvement tools.

INTRODUCTION

Pediatric asthma exacerbations result in over 700,000 visits to the emergency department (ED) annually in the United States.1 Children with moderate-to-severe asthma exacerbations often require extended stays in the ED and hospitalization.1 Corticosteroids are a cornerstone of acute asthma management.2 If administered early, oral corticosteroids reduce ED length of stay, hospitalization rates, and relapse.3–6

Emergency medical service (EMS) personnel treat millions of patients with asthma each year.7 Respiratory distress accounts for at least 14% of all pediatric EMS calls; of these, asthma is the most common diagnosis.8 Prehospital personnel evaluate and treat patients much sooner than hospital staff. The administration of prehospital corticosteroids can result in swifter improvement of pediatric asthma symptoms compared with ED administration. 9

In 2004, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention developed a model protocol for EMS personnel based on the National Asthma Education and Prevention guidelines.7 The protocol stressed the importance of prehospital corticosteroids for patients exhibiting signs of acute asthma exacerbation. In 2014, the National Association of EMS Officials recommended corticosteroids for their evidence-based pediatric asthma guidelines.10

Despite the literature showing improved outcomes for children with asthma receiving oral corticosteroids in the prehospital setting and national EMS guidelines recommending prehospital corticosteroids, EMS providers in our community are not routinely administering corticosteroids to children. Delayed uptake and adherence to pediatric prehospital protocols have been shown in our community and the literature.11 Prior studies have shown the use of multifaceted educational interventions to improve adherence to evidence-based pediatric prehospital protocols.12 The objective of this study was to use quality improvement science to increase adherence to the recommendation for prehospital oral corticosteroid administration for children with asthma exacerbations. Our SMART aim was to increase the proportion of children receiving systemic prehospital corticosteroids for asthma exacerbations from 0% to 70% over 2 years.

METHODS

At our institution, a cross-divisional team of pediatric emergency medicine (PEM) and EMS physicians convened to improve uptake of a new protocol to administer systemic corticosteroids to pediatric asthma patients being transported in Southwest Ohio by EMS providers. ur multidisciplinary team used improvement methodology to improve the uptake of the EMS protocol for the administration of corticosteroids for children 3–16 years of age with asthma exacerbations transported by EMS.

Setting and Context

We conducted this quality improvement initiative at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center (CCHMC), a large urban pediatric tertiary care center with an annual ED volume of approximately 95,000 children. This 600-inpatient bed pediatric institution has a level 1 trauma center responsible for 85%–90% of pediatric admissions from a population base of 2,000,000 people.

Community fire departments in the Greater Cincinnati region employ many paid part-time staff. The Academy of Medicine of Cincinnati Prehospital Protocol Committee comprises EMS Medical Directors, Emergency Medical Technicians Basics, Emergency Medical Technicians Paramedics, EMS Educators, Pharmacists, and Fire Chiefs. The committee created a unified prehospital protocol for the Greater Cincinnati Ohio region more than 40 years ago. As of 2014, over 70 fire departments have accepted the protocols (most in the Greater Cincinnati region). Each year, old protocols are updated and revised while new protocols are written. The protocols are designed to be both a practical guide for patient treatment and a teaching document. A final rough draft is dispersed in October to obtain pharmacy licenses and instruct EMS personnel to implement modifications. Final revisions occur in December, and protocols go into effect on January 1.13

Background/Preintervention Work

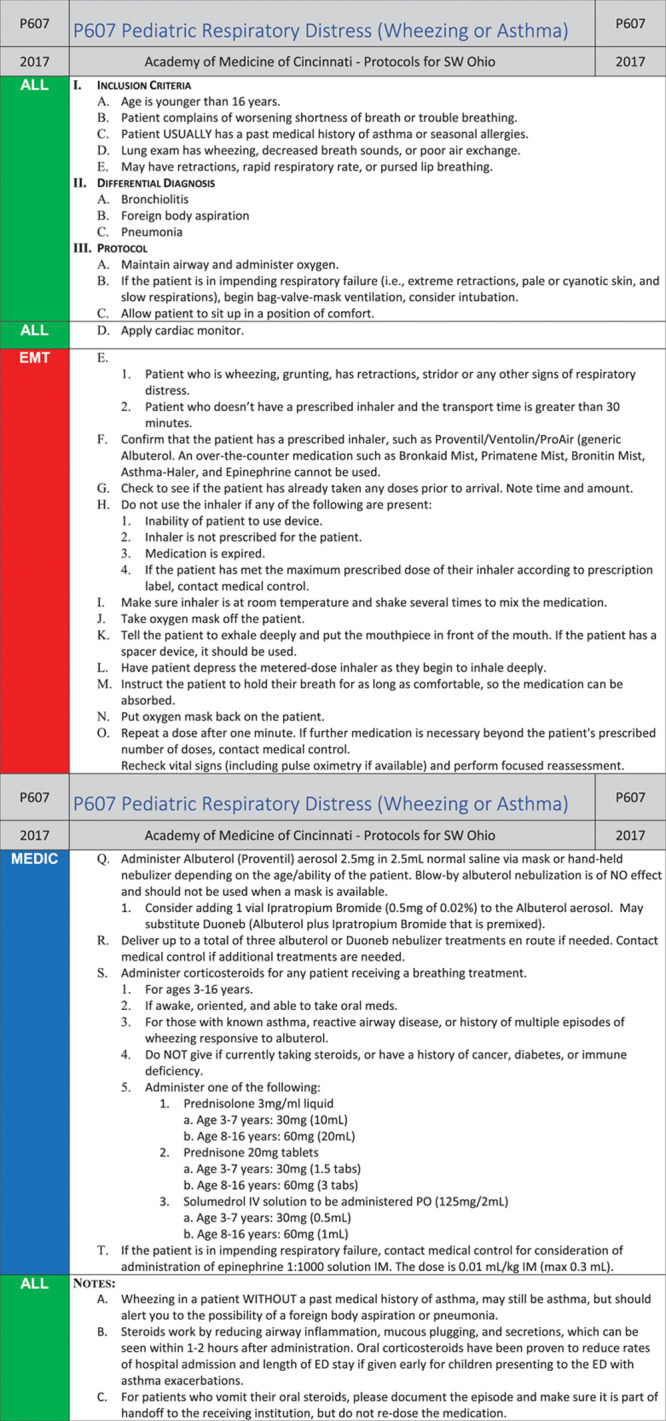

We implemented the prehospital corticosteroid protocol as part of an existing EMS pediatric respiratory distress protocol under the Prehospital Protocol Committee (Fig. 1). The Pediatric Respiratory Distress protocol includes children age 3–16 years with known asthma, reactive airway disease, or a history of multiple episodes of wheezing responsive to albuterol. The protocol excludes children with recent systemic corticosteroid administration or those with a history of cancer, diabetes, or immune deficiency. Those patients could be affected by taking an additional dose of a systemic corticosteroid. The protocol excludes those under 3 years who may have bronchiolitis and patients older than 16 years who may also receive care at an adult facility or community ED. Any patient transported to an adult facility or community ED would not be documented within our electronic medical record.

Fig. 1.

Pediatric respiratory distress prehospital protocol.

Age-based dosing was developed in conjunction with our PEM pharmacist to give a dose of 1–2 mg/kg for 3 different corticosteroids available to most EMS providers in the Southwest Ohio region: prednisone, methylprednisolone (IV for PO formulation), and prednisolone. Dexamethasone is not available to most EMS providers in our region, so we did not include it in the protocol despite its use at CCHMC. To assist with dosing and administration by EMS providers, we provided dosing parameters for 2 age groups (3–7 and 8–16 y) for each corticosteroid available, with units provided in milligrams, milliliters, and tablets.

The Academy of Medicine Prehospital Protocol Committee of Southwest Ohio approved the protocol, and education occurred per the Prehospital Protocol Committee standardized education in the fall of 2015. The protocol went into effect on January 1, 2016.

The CCHMC Institutional Review Board evaluated the project and determined that it did not meet the definition of human subjects’ research.

Interventions:

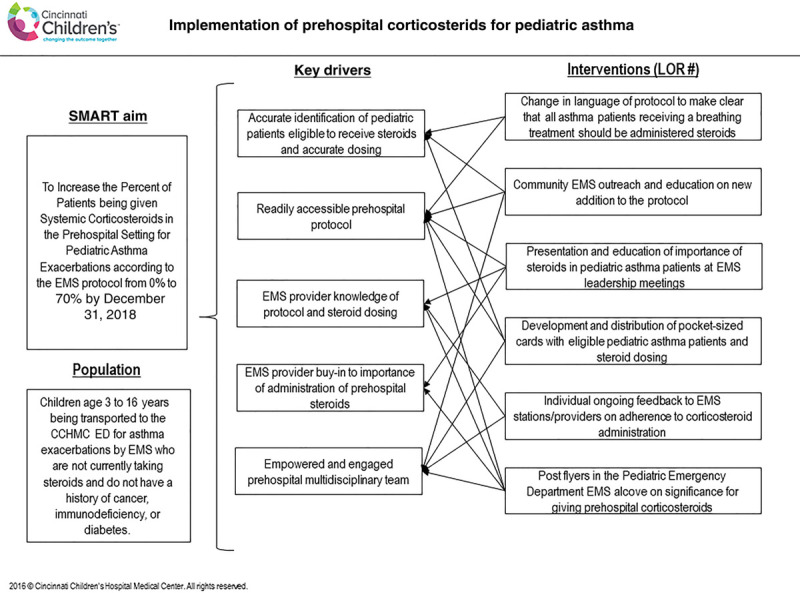

A team of PEM physicians, EMS physicians, EMS providers, and an emergency medicine pharmacist met to construct a key driver diagram making explicit their theory for improvement (Fig. 2). Throughout the study, the team iteratively revised drivers and interventions. They evaluated process failures through process review, analyzed feedback from frontline staff, and analyzed learnings from plan-do-study-act cycles. The team used multiple plan-do-study-act cycles to target key drivers to increase prehospital corticosteroid administration to pediatric asthma patients. Interventions are listed in the key driver diagram (Fig. 2) and discussed in detail below.

Fig. 2.

Key driver diagram.

Intervention 1. Community EMS Outreach and Education on the New Addition to the Protocol (March 01, 2016–November 25, 2016)

There is a standardized education process in place by the Southwest Ohio Prehospital Protocol Committee. New protocols and changes to existing protocols are developed and finalized between January and September of each year. The team developed a PowerPoint presentation, including all protocol changes, in September 2015, and disseminated the education in October 2015. All EMS providers are required to educate themselves on the protocol changes between the months of October and December. EMS leaders from each firehouse are responsible for discussing the protocol changes to ensure EMS provider exposure and education. Despite this standard educational delivery, there was minimal adoption of the protocol change, which prompted our team to explore additional EMS providers’ education opportunities.

In addition to the standardized education completed through the Prehospital Protocol Committee, our team provided education by PEM physicians to EMS providers. PEM fellows provided education to EMS providers at approximately 10 fire departments throughout the community in March–May 2016. The team created handouts, encouraging corticosteroid administration to pediatric asthma patients, and disseminated materials to all Cincinnati Fire and Colerain Township Fire Departments (the 2 largest fire departments in Southwest Ohio).

Our team’s PEM physicians visited the 2 busiest firehouses for pediatric transports to discuss corticosteroid adherence and importance (November 2016). Our team deemed this discussion necessary, given the initial low adherence to the new EMS protocol in early 2016. Our team hypothesized that personalized education to the EMS providers by PEM physicians would improve adherence through EMS provider recognition of the importance of the protocol change and answer any questions around challenges to the protocol change and/or administration of oral corticosteroids to pediatric patients.

Intervention 2. Presentation and Education on the Importance of Corticosteroids in Pediatric Asthma Patients at EMS Leadership Meetings (June 6, 2016–September 30, 2017)

As we anticipated that initial uptake of the protocol might be poor, additional education sessions were conducted at EMS lieutenant meetings to encourage all EMS providers to administer corticosteroids to children with asthma. Presentations were given at multidisciplinary EMS meetings in Southwest Ohio to stress the importance of the protocol changes. In the fall of 2017, we discussed barriers around adherence to pediatric protocols at the Pediatric Emergency Care Coordinator conference. EMS providers voiced a lack of confidence and unease with the administration of oral medications to pediatric patients. Once we identified this potential barrier to adherence, the team designed and disseminated education on administering oral medications to pediatric patients by educating fire department chiefs and handouts to fire departments (2017). Last, the Cincinnati Fire Department published an article in their newsletter on low adherence to the protocol. It stressed the importance of prehospital corticosteroid administration for pediatric asthma patients in the fall of 2017.

Intervention 3. Development and Distribution of Pocket-sized Cards with Eligible Pediatric Asthma Patients and Corticosteroid Dosing (December 1, 2016)

Educational resource cards were created and dispersed for EMS providers outlining inclusion criteria and corticosteroid dosing for pediatric patients. The team distributed these cards, placing them in pediatric EMS bags, giving them to EMS leaders to disperse to agencies, and providing them to EMS fire departments during education (2017). CCHMC provides pediatric EMS bags for EMS providers in our catchment area containing pediatric-specific equipment. The educational resource cards were point-of-care educational tools easily accessible for EMS providers, rather than looking through the EMS protocol book.

Intervention 4. Improved Clarity in the Language of the EMS Pediatric Respiratory Distress Protocol (January 1, 2017)

After implementing the protocol change, early data collection demonstrated very few asthma patients receiving prehospital systemic corticosteroids, despite standardized protocol education completed by each fire department. In January 2017, we changed the prehospital protocol language to improve clarity and state that “any child receiving a breathing treatment should also be given oral corticosteroids,” in hopes of improving adherence to the protocol.

Intervention 5. Individual Ongoing Feedback to EMS Stations/Providers on Adherence to Corticosteroids Administration (October 1, 2017–October 31, 2017)

In 2017, individualized station feedback on protocol adherence was given to EMS leaders at approximately 30 fire departments to encourage improvement through negative agency recognition and pride. Most fire departments had a protocol adherence to oral corticosteroids for pediatric asthma patients less than 50% of total eligible patients transported. Agency pride through individualized recognition, either negatively or positively, has had a prior impact on increasing adherence to protocols and/or research studies.

Intervention 6. Post Flyers in the Pediatric ED EMS Cubicle on the Importance of Giving Prehospital Corticosteroids. (December 1, 2017–January 30, 2018)

We posted flyers in the pediatric ED EMS cubicle on the importance of administering prehospital corticosteroids to children with asthma. Also, handouts and educational cards were placed in the cubicle for EMS providers to obtain and use.

Study of the Interventions

The team compiled data from the electronic medical record between January 1, 2016, and April 30, 2019, to identify eligible visits by children 3–16 years of age transported to the PED for an asthma exacerbation. We identified relevant cases using date, transportation method, and ICD-10 code of asthma exacerbation (J45.X). The primary author (L.R.) then reviewed EMS run sheets identified by ICD-10 code using a standardized chart review process. This review aimed to identify any potentially eligible patients evaluated in the ED for asthma exacerbation and transported by EMS.

The investigative group performed a chart review every 3 months to evaluate the effect of the interventions performed and determine the next steps. Education was an iterative process, with it being revised and delivered in different settings based on evaluating the intervention’s impact.

Measures

The primary process measure was the proportion of eligible patients who received prehospital corticosteroids. This measure’s numerator was any visit where the patient received a systemic corticosteroid in the prehospital setting. The denominator was any visit where a pediatric asthma patient was transported by EMS and eligible to receive prehospital corticosteroids. This measure was tracked overtime on a statistical process control chart to evaluate the impact of the described interventions’ impact.

Analysis

The team constructed a p-chart to track the proportion of eligible encounters during which a pediatric asthma patient transported by EMS to the CCHMC ED received prehospital systemic corticosteroids. Data were organized into groups of 10 for display, given the small number of encounters and variable arrival patterns. Statistical process control rules identified special cause variation.14

RESULTS

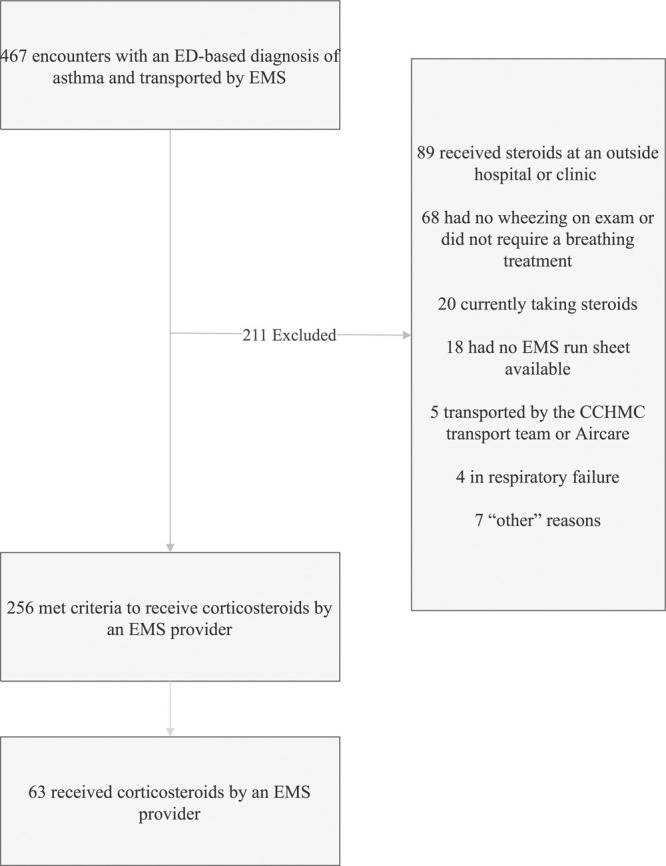

We evaluated 467 EMS transports between January 1, 2016, and April 30, 2019, with an ED-based diagnosis of asthma. We excluded 211 for the following reasons: received corticosteroids at an outside hospital or clinic (89), had no wheezing on exam or did not require a breathing treatment (68), currently taking steroids (20), no EMS run sheet available (18), transported by the critical care transport team or by helicopter (5), patient in respiratory failure (4), or other reason (7) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Flowchart.

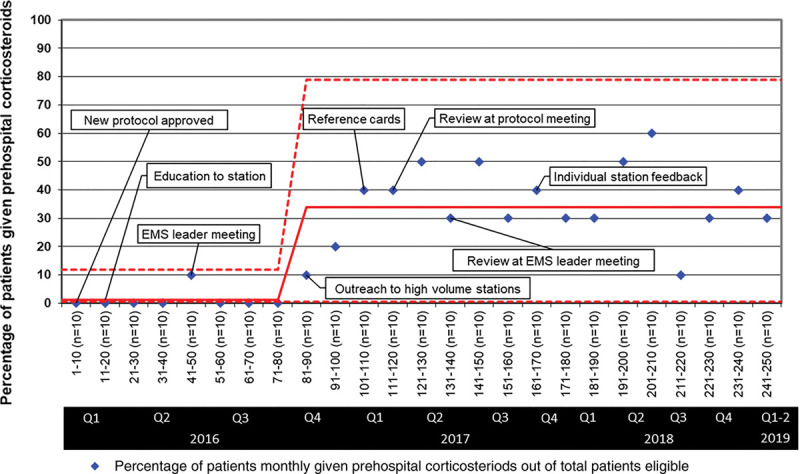

Following education to high-volume EMS stations, the team shifted the centerline from 0% to 34% based on established rules for special cause variation (Fig. 4). This shift occurred 12 months after the protocol was implemented and has remained at this level for 28 months. Interventions are annotated on the p-chart to make the team’s theory behind the improvement clear.

Fig. 4.

P-chart.

DISCUSSION

Summary and Interpretation

Variability exists in the management of children who are transported by EMS with an asthma exacerbation. Standardized protocols can improve EMS management of patients, but uptake of these protocols across EMS agencies can be varied and slow. Improvement methodology increased the proportion of encounters in which children were receiving systemic corticosteroids by an EMS provider.

Education to local high-volume EMS agencies, individualized feedback on adherence to corticosteroid administration, and an educational resource card were optimal interventions to increase guideline-adherent management. The foundation of early improvement is low-reliability interventions, such as education. These foundational interventions are required before a higher level of reliability interventions can be added.15

We did not achieve our SMART aim of increasing adherence to prehospital corticosteroid administration for children with asthma exacerbations to 70%. Numerous barriers exist to optimum adherence to available prehospital protocols. Carey et al11 described enablers and barriers to EMS provider protocol adherence and changes in EMS practices. They document paramedic-identified enablers and barriers to prehospital pediatric seizure management, differentiating between systems-level and provider-level.11 Systems-level enablers of protocol adherence included point-of-care decision support tools, the availability of multiple dosing routes for medication administration, and medical direction availability.11 Systems-level barriers to protocol adherence included protocol ambiguity, paramedic uncertainty regarding aspects of the protocol, equipment barriers, and lack of specific training. Provider-level barriers to protocol adherence included paramedic concerns around side effects from medication administration, dosing errors due to provider fatigue, inaccurate methods of weight estimation, and provider perceptions about medication effectiveness.11

Proposed solutions to overcome systems-level barriers include standard dosing, specific pediatric management training, and providing pediatric-specific equipment.11 Our team provided standard age-based corticosteroid dosing of multiple routes for administration, preventing dosing errors through inaccurate pediatric weight estimation methods. Our study utilized EMS agency outreach and education to demonstrate the benefits of systemic corticosteroids for pediatric asthma care. Education was an iterative process, with it being revised and delivered in different settings. We provided individualized EMS agency feedback regarding the numbers of asthma patients who received eligible corticosteroids based on the protocol. Most agencies’ adherence numbers were strikingly low, which most likely affected agency recognition and organizational pride negatively. Despite the standardized protocol committee educational process, initial adherence to new pediatric protocols has historically been low and taken time to improve. Our study team targeted the 2 agencies with the most pediatric asthma transports to educate the importance of the protocol changes. The centerline shift occurred in association with this intervention.

Numerous factors were present that could decrease the likelihood of protocol adherence, many of which can be mitigated through addressing solutions to provider-level barriers. During our educational sessions and outreach to high-volume fire departments, EMS providers voiced concerns about corticosteroid effectiveness and side effects. We addressed this concern through EMS providers and EMS leaders’ education to further educate their staff on the importance of prehospital steroid administration for children. During the Pediatric Educator Care Coordinator conference, EMS providers voiced concerns over the lack of clear benefit of systemic corticosteroids in pediatric asthma exacerbations and a lack of confidence describing the benefit to caregivers. Lack of confidence in administering oral medications to children was another problem, as most EMS providers in our region do not routinely administer oral medications to children. Our team worked to overcome this barrier through education and disbursement of handouts with various ways to administer oral medications to children.

Strengths

This quality improvement initiative improved adherence to a protocol for systemic corticosteroids for pediatric asthma in the prehospital setting. The clinical setting was a tertiary care pediatric ED staffed by PEM providers. Our team and collaborators provided education on the protocol change to PEM physicians, EMS providers, EMS educators, and EMS leaders. The variety of EMS agencies and fire departments and the variability in the care providers’ backgrounds speak to this study’s generalizability. CCHMC is the only tertiary care center for children in Cincinnati, Ohio. Therefore, nearly all children transported by EMS are referred to this center.

Limitations

This study occurred at one large pediatric institution and geographic location; therefore, the generalizability of our interventions is unknown. The team used ED-based ICD-10 billing codes for asthma exacerbation to obtain encounters that may have met the criteria to be transported by EMS and receive prehospital corticosteroids. Children with asthma exacerbations can have different ED billing diagnosis codes such as respiratory distress, difficulty breathing, upper respiratory infection, lower respiratory infection, respiratory failure, hypoxia, etc., that would have been missed in our study, leading to underreporting, thus skewing results.

The study team also provided individual feedback to EMS stations approximately 1 year after the protocol went into effect. CCHMC receives patients from over 70 different EMS agencies and fire departments. The study team collected data for 1 year to have enough patient encounters to give approximately 30 EMS agencies feedback regarding their protocol adherence to corticosteroid administration. Unfortunately, it was not feasible to identify the failure of corticosteroid administration in near real-time to provide feedback to EMS providers. This deficiency is a limitation of the study because delayed feedback is less impactful.

Data regarding postimplementation adherence to the guideline is only available for 28 months. It is unclear whether our team can sustain increased adherence in the future. Retrospective chart review is subject to bias due to inaccurate or incomplete data, which we attempted to mitigate with a standard process for the reviews. Last, we do not currently have the sample size to power an analysis of clinical outcomes. We feel that our focus on the improvement strategy for implementing this EMS protocol was critical to address the poor adherence to pediatric prehospital protocol changes.

CONCLUSIONS

Adherence to a prehospital pediatric protocol change recommending systemic corticosteroids for pediatric asthma exacerbations increased after a multidisciplinary quality improvement initiative. Multiple key drivers have sustained this initiative, including a readily accessible prehospital protocol, EMS provider knowledge of the protocol, easy age-based corticosteroid dosing with multiple options and routes, and an empowered, engaged multidisciplinary team. In addition to increasing protocol adherence through a higher level of reliability interventions, the next steps for this initiative include analyzing hospital outcome measures for prehospital systemic corticosteroid administration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We want to acknowledge Michelle Barrett, our talented PEM pharmacist, and The Southwest Ohio Prehospital Protocol Committee.

Footnotes

To cite: Riney LC, Schwartz H, Kurowski EM, Collett L, Florin TA. Improving Administration of Prehospital Corticosteroids for Pediatric Asthma. Pediatr Qual Saf 2021;6:e410.

Published online May 19, 2021

Disclosure The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akinbami LJ, Moorman JE, Liu X. Asthma prevalence, health care use, and mortality: United States, 2005-2009. Natl Health Stat Report. 2011;1–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. United States Department of Health and Human Services; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhogal SK, McGillivray D, Bourbeau J, et al. Early administration of systemic corticosteroids reduces hospital admission rates for children with moderate and severe asthma exacerbation. Ann Emerg Med. 2012; 60:84–91.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zemek R, Plint A, Osmond MH, et al. Triage nurse initiation of corticosteroids in pediatric asthma is associated with improved emergency department efficiency. Pediatrics. 2012; 129:671–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scarfone RJ, Fuchs SM, Nager AL, et al. Controlled trial of oral prednisone in the emergency department treatment of children with acute asthma. Pediatrics. 1993; 92:513–518. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tal A, Levy N, Bearman JE. Methylprednisolone therapy for acute asthma in infants and toddlers: a controlled clinical trial. Pediatrics. 1990; 86:350–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camargo CA. A model protocol for emergency medical services management of asthma exacerbations. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006; 10:418–429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Drayna PC, Browne LR, Guse CE, et al. Prehospital pediatric care: opportunities for training, treatment, and research. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2015; 19:441–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nassif A, Ostermayer DG, Hoang KB, et al. Implementation of a prehospital protocol change for asthmatic children. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018; 22:457–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.NASEMSO Medical Directors Council. National Model Clinical EMS Guidelines: Bronchospasm. Version 2.2. National Association of State EMS Officials; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carey JM, Studnek JR, Browne LR, et al. Paramedic-identified enablers of and barriers to pediatric seizure management: a multicenter, qualitative study. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2019; 23:870–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Marino MC, Ostermayer DG, Mondragon JA, et al. Improving prehospital protocol adherence using bundled educational interventions. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2018; 22:361–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Southwest Ohio Protocol Committee. Hamilton County (OH) Fire Chiefs Association. Hamilton County Emergency Medical Services (EMS). 2016. Available at http://www.hamiltoncountyfirechiefs.com/emergency-medical-service.html. Accessed October 1, 2015.

- 14.Provost LP, Murray S. The Health Care Data Guide: Learning from Data for Improvement. Jossey-Bass; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nolan T, Resar R, Haraden C, et al. Improving the Reliability of Healthcare: Innovation Series. Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2004. [Google Scholar]