Abstract

Introduction

Weekly formative Review Quizzes are an integral feature of the Georgetown University School of Medicine assessment program. The Quizzes offer students an opportunity to test themselves in a low-stakes setting and then discuss their answers with peers in small groups; faculty are also present to help the groups with difficult problems.

Methods

We conducted a mixed methods study in which we monitored quiz attendance over the course of the first four curricular blocks, deployed a study specific survey, and held focus groups to determine the factors that influenced quiz participation and how students perceived that the quiz contributed to their learning.

Results

We observed that Quiz attendance, while initially robust, dropped steadily over the course of the year. Nearly all students reported that the practice questions along with faculty explanations contributed strongly to their learning. Fewer students felt that discussion with their peers was valuable, but those who valued peer discussion were significantly more likely to attend the quiz in person. The two things cited most often as barriers to quiz attendance were inconvenience and lack of adequate preparation. Many students reported that they saved questions and did not attempt to answer them until they had completed study of that subject.

Discussion

Our results indicate that while there is ample evidence that early review and discussion with peers can contribute to learning, learners do not always recognize the value in this practice.

Keywords: Constructivism, Formative Assessment, Attendance, Mixed methods

Introduction

Formative assessment is a critical part of any programmatic system of assessment, and it is most effective when it is embedded, actionable, ongoing, and timely [1, 2]. The weekly small-group formative Review Quizzes that are a regular feature of the foundational phase of the Georgetown University School of Medicine (GUSOM) Journeys curriculum were designed to meet these criteria [3]. This activity is based on a social constructivist conceptual framework which posits that knowledge is constructed by the learner through social interaction rather than being passively absorbed [4]. The Quiz is taken in person, and students have an opportunity to discuss the questions with peers in small groups. Content experts are also available to answer questions, and detailed explanations are provided. These features are in keeping with best practices in that low-stakes assessments provide meaningful feedback to learners [5], with opportunities for feedback coming from peers and faculty, both in person and in writing. While the quiz was designed to be taken in person, attendance is optional, and students who choose not to attend can access the Quiz questions and answer explanations from peers.

After conducting the Review Quizzes for nearly 2 years, several issues emerged. During the first 7-week curricular block, attendance was very high, and students were observed to participate in lively discussions. However, feedback from faculty indicated that attendance at the sessions fell in subsequent blocks. The social constructivist framework predicts that the critical aspect of the design is group discussion in which students can test their ideas about the material and synthesize their knowledge [4]. However, students’ perception of the contribution of the Review Quiz to their learning may be different than that of the designers’. As recommended by the 2018 Consensus Framework for Good Assessment, we set about to carefully evaluate this aspect of our program of assessment [1]. Herein we describe the results of a mixed methods study of student perceptions of and participation in the Review Quizzes during the first year of the foundational curriculum.

Methods

Quiz Structure. The overall format of the Review Quizzes was designed with input from learners, who felt the quiz would be most useful if they could discuss their answers with peers. The Quiz is delivered in the GUSOM Dahlgren Medical Library second floor Team Based Learning space, where students can sit around tables in their academic families, pre-assigned groups of 10–11 students. In every Review Quiz session, students answer 20–30 multiple-choice questions individually and then discuss their answers with their academic family. Questions reflect the format of our module exams and comprise a mixture of new questions and those from previous years. Some quizzes cover material from the previous week, and others are grouped according to discipline. Faculty answer questions for individual students and groups or hold whole-class wrap-ups at the end of the session.

Study Period, Study Population, and IRB Approval. While the preclinical phase of the GUSOM curriculum includes six academic blocks over the course of three semesters, we focused on the first four blocks comprising the entirety of the first (M1) academic year. This allowed collection of survey and focus group data covering the same curricular period from two student cohorts, those scheduled to graduate in 2022 (M2022) and 2023 (M2023), and weekly attendance data for the M2023 cohort during the 2019–2020 academic year. The study was reviewed and approved by the Georgetown University Institutional Review Board.

Attendance Tracking. During the first three curricular blocks (August 2019 to March 2020), the number of attendees at each weekly quiz was determined by manual head count. During the fourth block (April–June 2020), the campus was closed to in-person activities in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, so the quizzes were held in a virtual format using the Zoom (San Jose, CA, USA) conferencing platform. Attendance was determined by unique Zoom login. Only students who took the quiz during the scheduled quiz period (11:00–12:00 on either Friday or Monday) and stayed for peer discussion were counted as having attended. Attendance was not tracked by student name.

Course Evaluation and Online Survey. Standard module evaluations were administered in New Innovations (Uniontown, OH, USA) for the M2023 cohort. Questions relevant to the Review Quiz were extracted from the larger data set. A study-specific online survey was administered to both study cohorts using the Qualtrics (Seattle, WA, USA) survey tool. It included four sections. Section one asked students to self-report quiz participation in each M1 curricular block. Section two asked students to report their level of agreement on a 5-point Likert scale with a series of statements regarding things that contributed to their quiz attendance and statements about their preferences for quiz structure. Section three asked students to rate different aspects of the quiz on a 5-point Likert scale in terms of how they contributed to their learning. Section four included several free response questions. The survey could be completed in about 10 min and was formatted to fit either a computer screen, smartphone, or tablet. Quiz respondents were recruited by email and Facebook. All quiz responses were anonymous.

Focus Groups. Two focus groups were conducted, one for each study cohort. The focus groups were facilitated by a professional from MediaBarn (Arlington, VA, USA). Each group met for approximately 60 min. Guiding questions to direct the groups included “Describe a Review Quiz experience which you feel benefitted your learning,” “How do you decide whether to attend the Review Quiz each week,” and “Describe your ideal Review Quiz format.” Focus group discussions were recorded and transcribed by MediaBarn, and transcripts were returned to the investigators for qualitative framework analysis. Focus group participants were recruited by email and Facebook, and all participants provided informed consent. Focus groups for both cohorts were held in March of 2020 using the Zoom platform. The M2023 cohort focus groups had seven participants, while the M2022 cohort had three. The total size of each cohort was approximately 200, and approximately 20 students from each cohort initially expressed interest in participating. The reduced participation was likely due to the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, as the scheduling of the focus groups corresponded to a time when many students were changing their living arrangements.

Analysis. Statistical analysis of quantitative survey data was performed using MedCalc® free online software (https://www.medcalc.org/index.php). Focus group transcripts and open response survey questions were subjected to qualitative analysis using the framework approach described previously [6]. Stages of analysis were familiarization (reading the transcripts in their entirety), framework/category development (identifying recurrent themes), indexing (tagging statements to various themes), and charting (lifting statements and grouping them according to theme). Initial category development for the M2 focus group transcript was performed independently by both researchers, who then built a standard framework. This framework was applied to the remaining transcript and open response data.

Results

Attendance

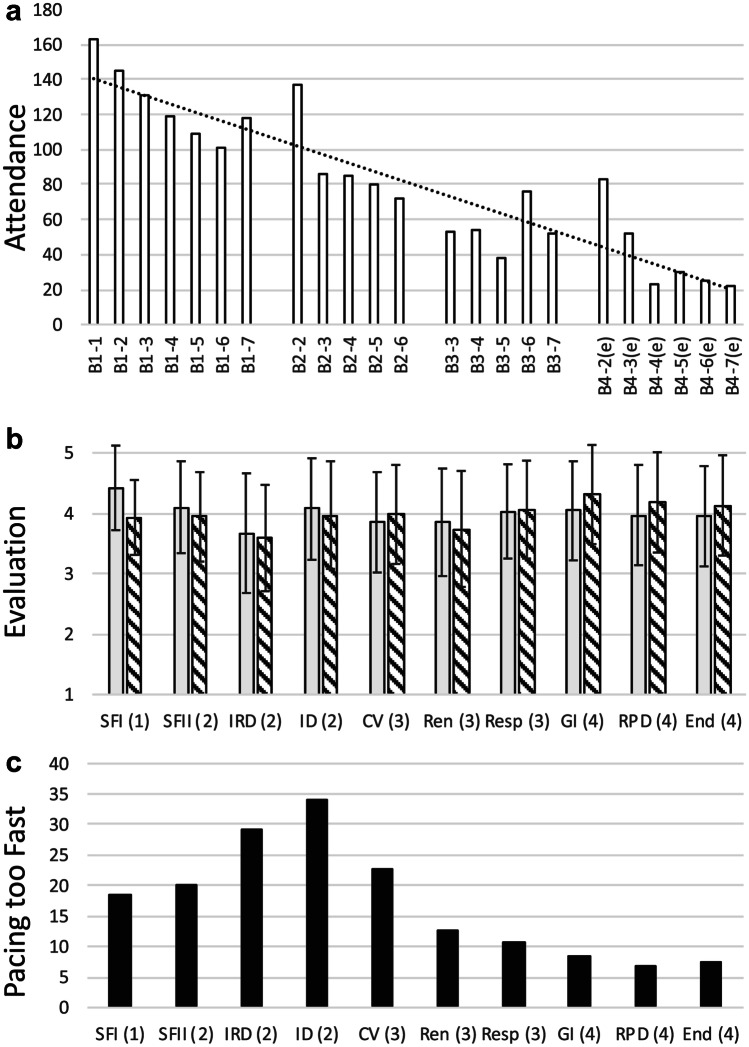

There were 208 students enrolled in the M2023 cohort during the study year. However, due to academic exemptions, only 158 took part in the entirety of the first year curriculum; therefore, the maximum number of students expected to participate in the Review Quiz each week varied from 158 to 208. There was a steady trend of decreasing attendance over the course of the academic year (Fig. 1a), starting with a high of 162 students at the first Review Quiz and dropping to a low of 22 at the last. At the first quiz (B1-1), every student who was responsible for the material presented that week was in attendance. There was a decrease in attendance every week of the block, save for a slight increase during week seven (B1-7), which was a cumulative review quiz held the week before the exams associated with the block. In blocks 2–4, the quiz was moved from Friday at 11:00 to Monday at 11:00. The first quiz of block 2 (B2-2) was relatively well attended, possibly due to a special effort to encourage attendance during a visit from representatives of the International Medical Educators Exchange [7]. The downward trend in attendance continued for the remainder of both blocks 2 and 3. One exception was quiz B3-6. At this Quiz, only students who attended in person were given access to the Quiz answers and explanations. In block 4, the Quiz was moved to a virtual format using the Zoom platform. The first Quiz of the block saw an uptick in attendance, with about 40% of the class participating. However, the remaining Quizzes of the block saw the lowest levels of attendance of the entire year.

Fig. 1.

Attendance and module evaluation data for curricular blocks 1–4 for academic year 2019–2020. a Attendance at the weekly review quiz during each week of blocks 1–4 (B1–B4); (e) Quiz delivered via Zoom rather than in person. b Module evaluation data. Grey bars: rate the overall quality of the weekly review quiz. Striped bars: rate the overall quality of the module. Average and standard deviation are shown. c Module evaluation data, percentage of students rating the pacing of the module as “too fast.” Module abbreviations and number of unique evaluations for each: SFI Scientific Foundations I (n = 186), SFII Scientific Foundations II (n = 171), IRD Immunology/Rheumatology/Dermatology (n = 169), ID Infectious Disease (n = 164), CV Cardiovascular (n = 176), Ren Renal (n = 169), Resp Respiratory (n = 174), GI Gastrointestinal (n = 170), RPD Reproduction (n = 167), Endo Endocrinology (n = 168); the block in which each module occurs is shown in parentheses

Students from both the M2022 and M2023 cohorts were asked to complete an anonymous survey specific to this study in which they self-reported whether and how they made use of the Quiz each academic block. We received completed surveys for 105 students, about 25% of the total study population. Self-reported attendance was consistent with the head count (Table 1), with respondents reporting attending an average of 5.3/7 quizzes during the first academic block, then decreasing steadily to an average of 1.75/6 quizzes in the fourth block. Students reporting that they got the questions from a peer increased from a low of 0.65/7 quizzes in Block 1 to a high of 2.46/5 quizzes in Block 3. During Block 4, the weekly Quiz and explanations were posted on the module Canvas site as a response to the COVID-19 restrictions, which may explain why a smaller number of students reported either attending or getting the Quiz from a peer in that block. Very few survey respondents indicated that they picked up questions and left or did not participate in the Quiz in any way.

Table 1.

Self-reported Quiz participation

| Quiz participation (quizzes/block) | Block 1 | Block 2 | Block 3 | Block 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attended and participated in discussion | 5.30 | 3.95 | 3.01 | 1.75 |

| Picked up questions and left before discussion | 0.35 | 0.68 | 0.56 | 0.30 |

| Did not attend. Got questions from peer | 0.65 | 1.69 | 2.46 | 1.82 |

| Did not attend or get questions | 0.25 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.39 |

| Total number of quizzes | 7 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

Framework Analysis

Focus group transcripts and survey open response answers were subjected to framework analysis as described in “Methods.” The focus groups were smaller than intended most likely due their timing in relation to our emergency transition to a virtual curriculum in response to the global pandemic. However, the framework developed from the transcripts proved adequate to capture the qualitative data gathered from the study-specific survey. Themes and sample responses for each are shown in Table 2. Additional responses are included throughout the “Results” section in conjunction with related quantitative data.

Table 2.

Framework analysis themes and examples

| Theme | Sample quotation |

|---|---|

| Benefits of Quiz | It was really helpful for us to see what [the professor] would emphasize and word things… what they thought was important. (M2022 Focus Group) |

| Usage of Quiz | I really appreciated having the questions when I was studying for finals. (M2023 Survey) |

| Reasons for attendance or non-attendance | Some topics I didn’t feel I needed the quizzes, so I did not go for [those topics]. (M2022 Survey) |

| Friday vs. Monday | Having it on Friday helps because then you’ve realized things you should spend more time on from a few weeks ago that you forgot. (M2023 Focus group) |

| Faculty role in Quiz | One of the missteps was when faculty members felt they had to go through questions with the whole group. (M2022 Focus Group) |

| Frustration with Quiz | Groups would finish early and it became loud and distracting. (M2023 Survey) |

| Suggestions for improvement | Maybe send [questions] out ahead of time so we can read and complete them in a couple minutes and then go over them as a large group faster. (M2022 Survey) |

Factors that Influence Quiz Attendance

The GUSOM Office of Medical Education requests that all students complete a standard, anonymous evaluation for every module at the end of each academic block in which they are asked to rate the quality of various module elements on a 1–5 Likert scale. Respondents’ ratings of the overall quality of the weekly Quizzes for each module varied from a high of 4.41 ± 0.7 to a low of 3.67 ± 0.99 (Fig. 1b). However, there was no relationship between the rating of the overall quality of the weekly Quiz and Quiz attendance (cf. Fig. 1a and b). This was also true when comparing the overall quality of each module (Fig. 1b) with Quiz attendance. Students are also asked to assess the pacing of each module, with the percent of students rating the pacing as “too fast” ranging from a high of 34% to a low of 6.7% (Fig. 1c). Once again there was no relationship between the percent of students rating the pacing of a module as “too fast” and Quiz attendance (cf. Fig. 1a and c).

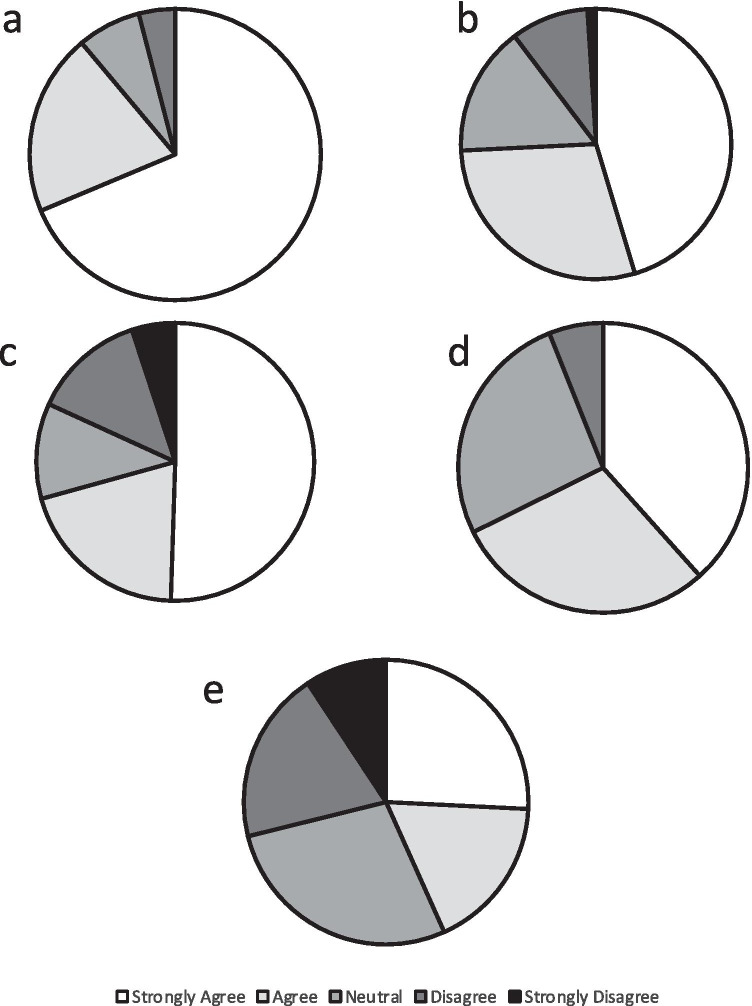

In the anonymous study-specific survey, students were asked a series of questions regarding the factors that influenced whether they attended the Review Quiz. On the survey, nearly all of the respondents (89%) selected “strongly agree” or “agree” to the statement “I am more likely to attend the Review Quiz if the questions reflect the structure and difficulty level of the exam” (Fig. 2a). In agreement with this, qualitative analysis of survey open response and focus group transcripts yielded comments such as “the review questions are very helpful to gauge the level of difficulty of the exam questions at the end of the block, especially for each subject.” About three quarters (74%) strongly agreed/agreed with the statement “I am more likely to attend the Review Quiz if I feel prepared to discuss the material with my peers” (Fig. 2b). Nearly the same number (71%) strongly agreed/agreed that they were more likely to attend the Quiz if they also attended other in-person activities on campus the same day (Fig. 2c). Many focus group and free response comments were aligned with these findings, highlighting both convenience and preparedness as important contributors to quiz attendance. Representative comments included “I commute to campus and it is hard to come to campus when there are no mandatory events on Mondays after the Quizzes,” and “I stopped going because I didn’t feel as prepared for the material and so I got less from the discussions.” About two-thirds of the respondents (67%) strongly agreed/agreed that the presence of faculty at the Quiz was an important contributor to whether or not they attended (Fig. 2d), with one student commenting “a way to increase incentive to go is having a guarantee that professors or clinicians… will be there.”

Fig. 2.

Factors influencing in-person attendance at weekly Review Quiz. Study-specific survey respondent (n = 105) level of agreement with the following statements: a I am more likely to attend a Review Quiz if the questions reflect the structure and difficulty level of the summative exam. b I am more likely to attend the Review Quiz if I feel prepared to discuss the material with my peers. c I am more likely to attend the Review Quiz if I attend the lectures or other on-campus activities held on the same day. d I am more likely to attend a review quiz if faculty will be present to answer questions. e I am more likely to attend a Review Quiz held on Monday than Friday. White, Strongly Agree; Light Grey, Agree; Medium Grey, Neutral; Dark Grey, Disagree; Black, Strongly Disagree

Results were mixed as to whether students were more likely to attend the Quiz based on whether it was held on Friday or Monday, with 44% indicating they were more likely to attend a Quiz on Monday versus Friday, 29% saying they were not more likely to attend a Quiz on Monday versus Friday, and 28% of the respondents being neutral on this question (Fig. 2e). We saw a similar degree of diversity in open response and focus group comments. For example, “I enjoyed Friday Quizzes because you would have the material for the week… it would help me focus over the weekend for my studying” versus “when they changed to Monday it was helpful because you had extra time to prepare for that Quiz.” Overall there was no consensus on whether students preferred having the Quiz at the end or the beginning of the week.

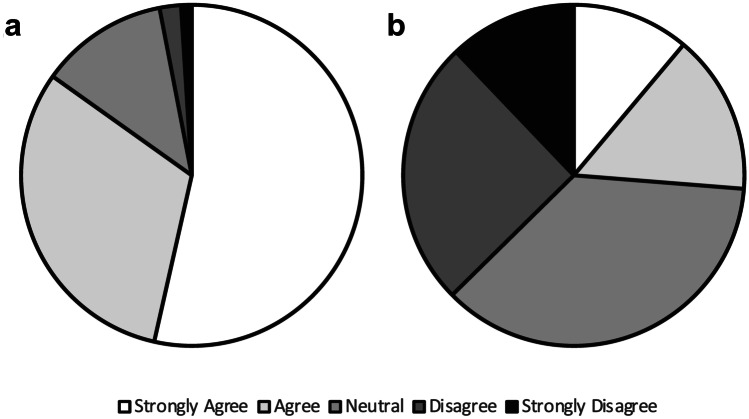

The GUSOM curriculum is presented in a series of systems modules that integrate material from a variety of basic science courses such as biochemistry, immunology, and pathology. Students felt strongly that the Quiz should cover material presented over a defined time period, such as the week preceding the Quiz, rather than being organized by subject matter, with 85% of the respondents strongly agreeing/agreeing with the statement “Review Quizzes should cover material from the previous week” (Fig. 3a). Conversely, only 26% of the respondents strongly agreed/agreed with the statement “Review Quizzes should be organized by course” (Fig. 3b). These results were reflected in comments from focus groups and open response survey questions. One student commented that “I started to not go to quizzes in block three because I felt they weren’t reflective of what we had been learning that previous week,” while another felt there was no reason to attend “if we don't know what material is going to be on it, if it’s material from a month ago.” Another recognized that “the benefit of having them [organized] by week… is that it makes you keep up with the material.”

Fig. 3.

Preference for Quiz format. Study-specific survey respondent (n = 105) level agreement with the following statements: a Review Quizzes should cover material from the previous week (e.g., Mon–Fri for a Mon quiz). b Review Quizzes should be organized by course (e.g., Path one week and Pharm the next). White, Strongly Agree; Light Grey, Agree; Medium Grey, Neutral; Dark Grey, Disagree; Black, Strongly Disagree

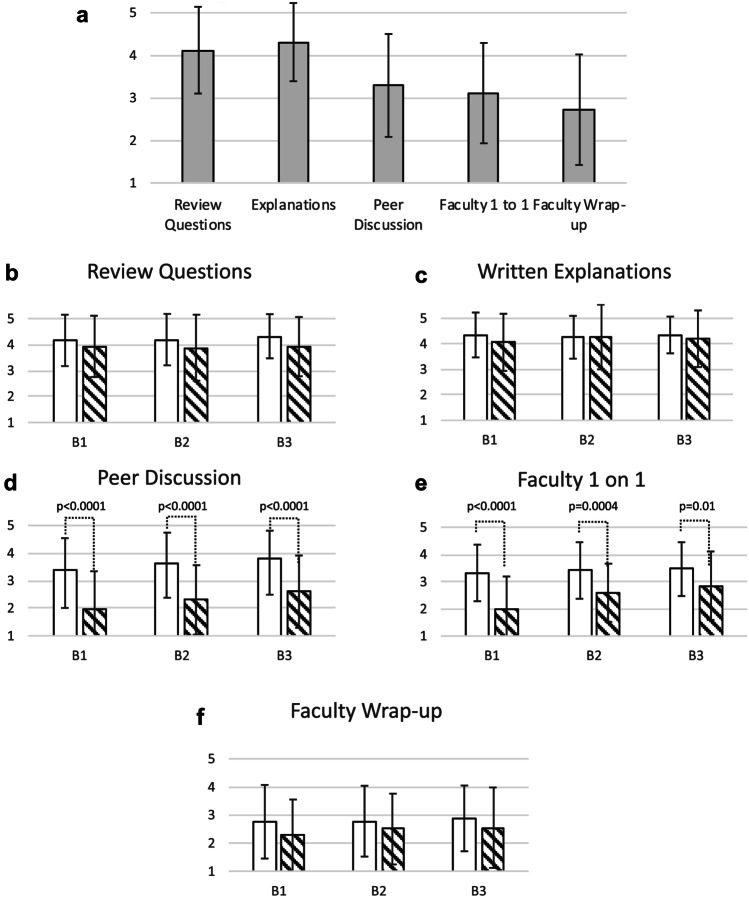

Students Perceptions of How the Quiz Contributed to Their Learning

Students were asked to indicate on a scale of 1–5 how much different aspects of the Quiz contributed to their learning, with 5 being “very strongly contributed” and 1 being “did not contribute.” Respondents as a whole felt that both the Quiz questions (4.12 ± 1.0) and the written explanations provided by faculty (4.31 ± 0.9) strongly or very strongly contributed to their learning (Fig. 4a). Discussion with peers (3.29 ± 1.2) and faculty one-on-one or small group discussion (3.11 ± 1.2) were found to contribute to learning. There was less enthusiasm for faculty “wrap-up” sessions involving the whole class (2.72 ± 1.3), with respondents as a whole feeling this fell somewhere between “contributed” and “marginally contributed” to their learning. Qualitative responses from the survey and focus groups indicated that some students felt the room in which the Quiz was held was not well-suited to faculty wrap-ups for the class as a whole.

Fig. 4.

Perceptions of how Quiz elements contribute to learning. a Average and standard deviation of ratings from all survey respondents (n = 105). b–f Comparative analysis of perceived value of each Quiz element between high-attenders (white bars) and low-attenders (striped bars). Unpaired Student’s t-test was used to compare groups; all values for t, p, and n are provided in Table 3

We next divided survey respondents into bins of “high attenders” who reported attending five or more Quizzes per block and “low attenders” who reported attending two or fewer Quizzes per block, to see if the two groups differed in what aspects of the Quiz they felt contributed to their learning. The binning analysis was only performed for blocks 1–3, due to the unplanned change to the virtual Quiz format in block 4 and the overall low attendance in that block. High attenders from blocks 1–3 were significantly more likely to value discussion with peers and one-on-one and small group discussion with faculty (Fig. 4d and e; Table 3). Analysis of free response questions indicated that some students stopped attending because others in their group were not attending. Other students expressed frustration if they were the only one in their group who was prepared for the quiz. Both high- and low-attenders valued the Quiz questions and written explanations, with no significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 4b and c). There was also no significant difference between high- and low-attenders with regard to the value they placed on whole class wrap-up sessions (Fig. 4f). Qualitative analysis of the survey free response questions and focus group transcripts was in agreement with the quantitative data. Many students commented that they valued the Quiz questions and written explanations in particular. Multiple students stated that rather than completing the Quiz on the day it was given, they saved the question for review just prior to the exam.

Table 3.

Quiz elements valued by high- versus low-attenders

| Block 1 | Block 2 | Block 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| High attenders | n = 78 | n = 55 | n = 37 |

| Low attenders | n = 21 | n = 39 | n = 56 |

| Review questions |

t = 0.889 p = 0.376 |

t = 1.321 p = 0.189 |

t = 1.938 p = 0.0557 |

| Explanations |

t = 1.239 p = 0.219 |

t = 0.046 p = 0.9.64 |

t = 0.791 p = 0.431 |

| Peer discussion |

t = 4.829 p < 0.0001 |

t = 5.44 p < 0.0001 |

t = 4.640 p < 0.0001 |

| Faculty 1 on 1 |

t = 4.908 p < 0.0001 |

t = 3.694 p = 0.0004 |

t = 2.610 p = 0.0106 |

| Faculty wrap-up |

t = 1.497 p = 0.138 |

t = 1.053 p = 0.295 |

t = 1.220 p = 0.226 |

Discussion

The weekly formative Review Quiz is a regular feature of the preclinical curriculum at GUSOM. It was designed based on a social constructivist framework to correspond to best practices in formative assessment [1, 4, 5]. In studying how students made use of the Quiz over the course of the first academic year, several things stood out. First of all, in-person Quiz participation decreased steadily over the course of the year, from 100% attendance at the first Quiz to about 11% attendance at the last. The decrease in attendance was independent of how students evaluated the quality of the Quiz, the quality of the module in which the Quiz was embedded, and the pacing of the curriculum. Despite an earlier poll indicating that a plurality of students would prefer that Quizzes be held on Mondays rather than Fridays, we saw no increase in attendance for Quizzes held on Mondays. Students cited inconvenience and lack of preparation as important barriers to their attendance. While nearly all of the students felt that the Quiz questions and written explanations provided by faculty strongly contributed to their learning, fewer felt like discussion with peers was a contributory factor. Critically, students who valued peer discussion were significantly more likely to attend the Quiz in person.

The majority of study participants reported that they are more likely to attend the Quiz if they also participated in other on-campus activities that day, and many open response answers cited inconvenience in timing or location as a barrier to quiz attendance. The Quiz takes place at a consistent time in each curricular block. There are no mandatory learning sessions scheduled for those days, and all lectures in the preclinical curriculum are recorded. Students who rely primarily on recorded lectures for their learning may have reduced incentive to commute to campus solely for the purpose of attending the Quiz in person. One caveat to this is our observation in the final curricular block of the M1 year, during which the Quiz was conducted entirely over Zoom. The downward trend in attendance continued during this block, which indicated that most students chose not to participate synchronously even though this did not require driving to campus. Holding the Quiz in a virtual environment was not part of the original study design and only came about because of disruption of the 2019–2020 academic year due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, it offered an interesting variable to our analysis. Would students be more likely to participate in the Quiz synchronously if they could do it from their own homes? The answer was no. While there were members of the class who reported general connectivity issues, there is no reason to believe this was a significant barrier for a large number of students. All students were able to take the module exams electronically at the end of the block, indicating that their connectivity would have been adequate to participate in the Quiz. One way to address the issue of inconvenience is to hold the Quiz on days when other mandatory in-person activities such as team based learning are scheduled. However, our observation that attendance dropped even when students could participate from home suggests that convenience is not the only, or even the primary, factor driving lack of in-person participation.

Concerns about adequate preparation were also frequently cited as reasons for lack of Quiz attendance, and a majority of study participants stated they were more likely to attend if they felt prepared. This at first seems at odds with the observation that there was no relationship between module pacing and Quiz attendance. The Quizzes in blocks 3 and 4 were poorly attended despite the fact that the modules in these blocks had the same or more appropriate pacing than those in blocks 1 and 2, as perceived by the students. It is possible that students adjusted their own pacing by decreasing participation in non-mandatory activities such as the Quiz. Several lines of evidence suggest the answer is more complicated than that. When asked how the Quiz should be organized, students showed a strong preference for organization based on calendar date (85%) rather than by subject (26%). The preclinical curriculum consists of discrete systems modules (e.g., renal and gastrointestinal) which integrate material from longitudinal disciplinary courses (e.g., pathology and pharmacology). Every learning session is tagged by module and course (e.g., a pathology lecture in a renal module), and it has a specific time slot on the calendar. The exams at the end of each academic block are organized by module; thus, students may put primacy on the module rather than the course designation when organizing their studying. During the first academic block, all Quiz material was organized by date, with each Quiz covering learning sessions from the previous week. In subsequent blocks, Quizzes were often organized by course, so a Monday Quiz might include all of the immunology and pharmacology material from the past several weeks but not the pathology presented during those weeks. Despite an effort to make clear what courses were covered on each Quiz, many students in their open response questions cited this as a source of confusion and frustration. Thus, they may have felt unprepared for the quizzes not because the pacing was too fast but because they were not sure what would be on the Quiz. The issue could be addressed by developing a consistent policy dictating what material will be included on each Quiz.

How do students value the quiz in terms of their learning? Nearly all study participants valued the quiz questions and the detailed written explanations provided by faculty, and they felt strongly that questions should reflect the structure of the exam. This was true whether or not respondents regularly participated in the Quiz in person, which may explain why they would rate the Quiz as being of high quality despite the fact that they did not attend. However, only a subset of study participants felt peer discussion contributed to their learning, and these students were significantly more likely to participate in the Quiz in person. Thus, perceptions of the value of peer interaction may be the most important determinant of whether a student actively participates in the Quiz or simply uses the questions as part of an individual study plan. These results are in keeping with those of Cong et al. who examined students attitudes towards online formative assessments in Physiology and found that students valued practice questions and input from faculty more than feedback from their peers [8], and White et al. who found that students did not fully appreciate the value of collaborative learning [9]. In addition, Lutze-Mann and Kumar found that formative assessment lectures which featured explanations from faculty but de-emphasized peer interaction were very popular with learners [10]. The incorporation of peer discussion groups into the curriculum builds a sense of community among learners, promotes collaboration, and provides multiple advantages in terms of learning outcomes [11, 12]. It is critical to make students aware of the advantages of peer collaboration so that they can make best use of curricular opportunities.

Seen in a larger context, our results indicate that students’ views on what contributes to their learning influence how they interact with the curriculum. Decreased student attendance at non-mandatory lectures and learning activities has been observed at many medical schools. As reported by the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) Medical School Year Two Questionnaire 2018 All Schools Summary Report [13], “fewer than half (43.7%) reported having attended in-person pre-clerkship courses or lectures at their medical school ‘Most of the time’ (31.9%) or ‘Often’ (11.8%).” Various studies on how lecture attendance affects learning outcomes have yielded mixed results, and this is complicated further when lectures are recorded and can be viewed asynchronously at a time of the student’s choosing [14–16]. Students who do not attend in-person activities can choose to customize their learning by accessing a variety of resources without impacting performance on assessments [17]. Lamb et al. found that students will attend optional “recommended” activities if they feel it benefits their learning [18], but that they resent being forced to attend activities that they do not feel benefit them. Developmentally, medical students may be considered adult learners [19]. Thus, based on Knowles’ concept of andragogy [20], they are motivated to direct their own learning, and they want to know how each aspect of their learning will specifically benefit them. They also bring many years of learning habits that have brought them previous success, and they apply these to the new environment of medical school. Indeed, students with high self-efficacy are less likely to attend optional activities but still perform well on assessments [16, 21]. However, there is also ample data to demonstrate that even with the best of intentions learners do not always make choices that most benefit their learning. For example, in group work, many students express a preference for working with friends rather than assigned groups, but assigned groups lead to better learning outcomes [9, 12]. In our study, several students professed to save the Quiz questions for review until right before the exam, despite evidence that recall based study in which formative questions are used throughout the learning process leads to the best performance on assessments [1, 2, 5, 22].

Conclusions

In summary, students report that the weekly formative Review Quiz adds value in terms of their learning and consistently report that it is of high quality. However, only some students value the peer interaction component of the Quiz, and these students are more likely to attend the Quiz on a regular basis. Our study indicates that students’ beliefs about what contributes to their learning must be taken into account when designing a programmatic system of formative assessment. Going forward, it will be important to continue to provide opportunities for peer interaction on Quiz material for students who feel this benefits their learning. For learners who prefer to interact with the Quiz individually, we will need to emphasize the benefits of using the questions as to guide their study throughout the block, rather than saving them until their preparation for summative assessments is complete. By offering flexibility, the Review Quiz can best meet the needs of our diverse body of learners.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Carrie Chen (GUSOM) for her help in developing this research question, Dr. Ming-Jung Ho for critical reading of the manuscript, and the Georgetown Center for Innovation and Leadership in Education for support of scholarly work in education. Thank you also to Heather Gay from MediaBarn for conducting the focus groups.

Funding

This project was supported by a CIRCLE grant made to Dr. J.M. Jones by the GUSOM Office of the Dean for Medical Education.

Declarations

Ethical Approval

This project was reviewed and approved by the Georgetown University Institutional Review Board.

Informed Consent

All study participants provided informed consent.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Norcini J, Anderson MB, Bollela V, et al. 2018 consensus framework for good assessment. Med Teach. 2018;40:1102–1109. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1500016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konopasek L, Norcini J, Krupat E. Focusing on the formative: building an assessment system aimed at student growth and development. Acad Med. 2016;91:1492–1497. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malhotra JV. Charting a new course for future physicians. Georgetown Health Magazine. 2016; :10–16.

- 4.Palincsar AS. Social constructivist perspectives on teaching and learning. Annu Rev Psychol. 1998;49:345–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Der Vleuten CPM, Schuwirth LWT, Driessen EW, Govaerts MJB, Heeneman S. Twelve tips for programmatic assessment. Med Teach. 2014;37:641–646. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.973388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cate Oten, Mann K, McCrorie P, Ponzer S, Snell L, Steinert Y. Faculty development through international exchange: the IMEX initiative. Med Teach. 2014;36:591–595. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.899685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cong X, Zhang Y, Xu H, et al. Perspective: a questionnaire study. Adv Physiol Educ. 2020;44:726. doi: 10.1152/advan.00067.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White C, Bradley E, Martindale J, et al. Why are medical students ‘checking out’ of active learning in a new curriculum? Med Educ. 2014;48:315. doi: 10.1111/medu.12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lutze-Mann L, Kumar R. The formative assessment lecture: Enhancing student engagement. Med Educ. 2013;47:526–527. doi: 10.1111/medu.12162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corden R. Group discussion and the importance of a shared perspective: learning from collaborative research. Qual Res. 2001;1:347–367. doi: 10.1177/146879410100100305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hudson S. Effective teaching methods. Journal of Instructional Research. 2015;4:90–93. doi: 10.9743/JIR.2015.12. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Association of American Medical Colleges. Medical School Year Two Questionnaire: 2018 All Schools Summary Report. March 2019.

- 14.Eisen D, Schupp C, Isseroff R, Ibrahimi O, Ledo L, Armstrong AW. Does class attendance matter? Results from a second-year medical school dermatology cohort study. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54:807–816. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoyo LM, Yang CY, Larsen AR. Relationship of medical student lecture attendance with course, clerkship, and licensing exam scores. Medical Science Educator. 2020;30:1123–1129. doi: 10.1007/s40670-020-01022-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kauffman CA, Derazin M, Asmar A, Kibble JD. Relationship between classroom attendance and examination performance in a second-year medical pathophysiology class. Adv Physiol Educ. 2018;42:593–598. doi: 10.1152/advan.00123.2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horton DM, Wiederman SD, Saint DA. Assessment outcome is weakly correlated with lecture attendance: Influence of learning style and use of alternative materials. Adv Physiol Educ. 2012;36:108–115. doi: 10.1152/advan.00111.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamb S, Chow C, Lindsley J, et al. Learning from failure: How eliminating required attendance sparked the beginning of a medical school transformation. Perspectives on medical education. 2020;9:314–317. doi: 10.1007/s40037-020-00615-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Misch DA. Andragogy and medical education: are medical students internally motivated to learn? Adv Health Sci Edu Theory Pract. 2002;7:153–160. doi: 10.1023/A:1015790318032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knowles MS, Holton III EF, Swanson RA. The adult learner: the definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Routledge, 2014.

- 21.Stegers-Jager KM, Cohen-Schotanus J, Themmen APN. Motivation, learning strategies, participation and medical school performance. Med Educ. 2012;46:678–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Karpicke JD, Roediger HL. The critical importance of retrieval for learning. Science (American Association for the Advancement of Science) 2008;319:966–968. doi: 10.1126/science.1152408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]