Abstract

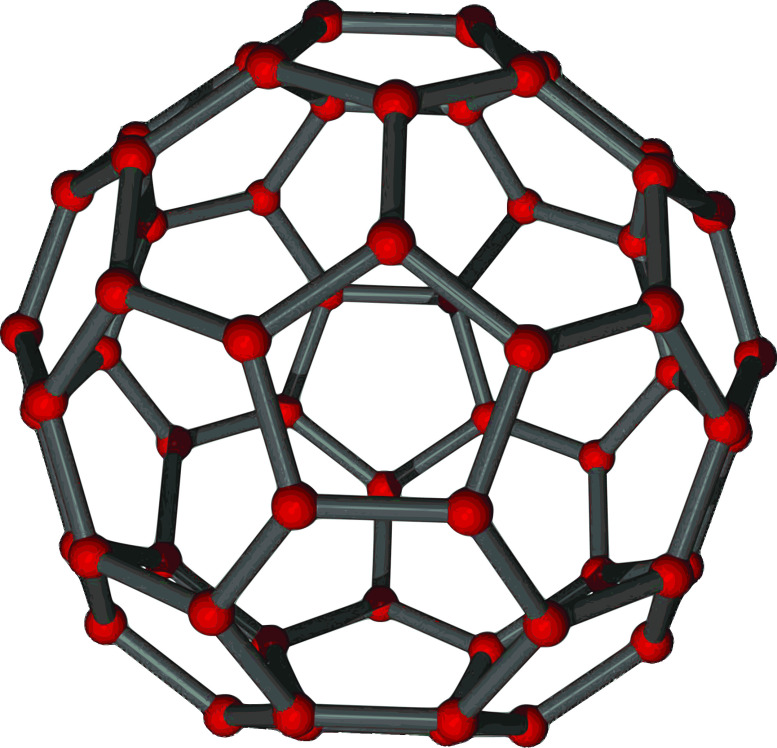

Why do racial inequalities endure despite numerous attempts to expand civil rights in certain sectors? A major reason for this endurance is due to lack of attention to structural racism. Although structural and institutional racism are often conflated, they are not the same. Herein, we provide an analogy of a “bucky ball” (Buckminsterfullerene) to distinguish the two concepts. Structural racism is a system of interconnected institutions that operates with a set of racialized rules that maintain White supremacy. These connections and rules allow racism to reinvent itself into new forms and persist, despite civil rights interventions directed at specific institutions. To illustrate these ideas, we provide examples from the fields of environmental justice, criminal justice, and medicine. Racial inequities in power and health will persist until we redirect our gaze away from specific institutions (and specific individuals), and instead focus on the resilient connections among institutions and their racialized rules.

Keywords: Racism, Inequity, Race/Ethnicity, Disparity, Social Determinants

Introduction

Even those Herculean efforts we hail as successful will produce no more than temporary “peaks of progress,” short-lived victories that slide into irrelevance as racial patterns adapt in ways that maintain White dominance.

-- Derrick Bell1

Bell’s epigraph responds to the question, why have we continually failed to achieve racial equity despite improvements in certain areas of civil rights?1 Racism has never left, but has changed with the times,2 which observers have characterized as “modern racism,”3 the “new Jim Crow,”4 “reinvented racism,”5 and “a more civilized way of killing.”6 One reason for racism’s durability is the focus on interpersonal and institutional racism without a corresponding focus on structural racism,7,8 which we define as the totality of how society is organized to privilege White communities at the expense of non-White racialized communities.9-11

Structural racism is partly maintained by institutional racism, referring to racial inequity perpetuated by organizations, such as banks, hospitals, and governmental agencies. Although structural and institutional racism are often conflated, an analogy from chemistry may help clarify their differences. Buckminsterfullerene (bucky ball) is a molecule of carbon atoms arranged like a soccer ball (Figure 1). It is incredibly strong and stable because forces exerted on a single atom are distributed through the bonds of the entire structure of the molecule. Similarly, a hard kick to a soccer ball momentarily deforms it, but the ball reverts to a sphere. Each societal institution is like a carbon atom, perpetuating institutional racism. Structural racism, then, derives its strength and resilience from the interconnections among institutions, just as Buckminsterfullerene does from the connections among carbon atoms.12,13 While studies of institutional racism focus on single institutions, studies of structural racism must emphasize the connections across multiple institutions, and the system as a whole.9

Figure 1. Buckminsterfullerene.

Further, there are underlying practices common across institutions, which we term racialized rules, just as the carbon atoms and atomic bonds in Buckminsterfullerene all operate with the same chemical rules. These explicit and implicit rules refer to the norms, principles, and regulations that govern the behavior of individuals and organizations that reinforce racial hierarchies. Our institutions may oversee seemingly different aspects of American life, but the racialized rules create similarities across institutions that facilitate their symbiotic interconnectedness.

Inter-Institutional Connections

Inter-institutional connections facilitate cooperation to maintain structural White supremacy.12 Residential segregation and environmental pollution provide an example of the bonds among different institutions. The United States has always been a racially segregated society14,15 and neighborhood racial composition continues to be a primary determinant of the location of industrial polluters.12,16 Both segregation and the unequal distribution of pollution have been state sponsored through race-based zoning, with assistance from private entities through restrictive covenants, banking practices, and real estate steering.17-21

Exclusionary land zoning practices help determine home cost and location, prohibit multi-family housing or requiring minimum home and lot size, and exclude poor and non-White families from certain areas of the city. Land use zoning dictates whether land is used for housing, public parks, or industrial facilities, for example, distributing resources like parks and burdens like polluting facilities to different neighborhoods.

One might expect that cities without zoning policies would be more racially integrated and would show environmental equity. Houston, for example, has never been zoned. However, compared with the zoned city of Dallas, Houston is similar in its segregation of home value, lot sizes, multi-family housing, and race/ethnicity,22 and has also disproportionately burdened non-White families with pollution. The work of one institution, local government, was shifted to private industry, but the effect of racial inequity remains.18,22

Institutional cooperation also shows in the regulation of marijuana possession and distribution. Racialized criminalization of marijuana use was a way to control immigration from Mexico as early as the 1930s.23 The narrative changed in 1972 when National Commission on Marijuana and Drug Use reported that usage was high among White and wealthy students, with White men more likely than others to be arrested.24 States softened punishments and marijuana came under the purview of social and health services. The narrative changed again with the War on Drugs, which reprised marijuana as a criminal justice issue. Arrests related to marijuana possession increased dramatically, disproportionately for Black men.25 The narrative continues to evolve now that marijuana is a commodity. In Colorado, Black men were still twice as likely to be arrested for marijuana possession compared with White men.26 Yet, the marijuana business, dominated by White men, generates annual revenue of $1.8 billion.27 Thus, marijuana is controlled by economic interests for White residents and the criminal justice system for Black residents. With each shift in narrative, a new institution would come to regulate race and marijuana, from criminal justice, to health and human services, to business and agriculture.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed how institutions operate together to disproportionately burden non-White Americans.28-32 Our interconnected institutions have established a system of racially unequal vulnerability to COVID-19. Residential, educational, and occupational segregation and the unequal resource investment have ensured that non-White Americans are disproportionately living in under-resourced neighborhoods with under-resourced schools, and working in front-line, essential, yet precarious occupations.33 Upon this socially driven, morbidity-related vulnerability, COVID-19 testing has been less available for areas with large proportions of non-White families,34 increasing transmission risk. Further, social distancing measures can themselves be deadly, as show in this quote:

“[B]lack men have to pick their poison — risk their lives (and the lives of others) to Covid-19 by not wearing a mask [or] risk their lives to police officers who see them as suspicious while wearing a mask.”35

The impact of this population health shock will likely reverberate in racial/ethnic inequities for generations, not only due to the unequal long-term impact of the economic downturn, but also due to the transition to online education and workplaces. The use of online learning assumes equity in technology, food security, and stable job schedules and flexibility for family members who can support remote learning. The racial inequity of each of these factors will compound the existing inequities in educational quality. Because systems of racial inequity are replicated and reinforced across the sectors of education, labor, and health, it will be particularly challenging to address the resulting health inequities resulting from this single pandemic.

Racialized Rules

Racialized rules, embedded in everyday practice across institutions, serve to maintain the racial hierarchy while appearing neutral on their surface. Consider the way in which race groups are commonly ordered in publications with White listed first (Table 1). Races are not sorted by population size, in alphabetical order, or by time of settlement in the United States. The most plausible reason for having the White category first is that they are the default, normal reference group from which to consider all others, based on unwritten norms on how to represent race in research.

Table 1. American Community Survey 5-year estimates, 2019, by race. Race alone or in combination with one or more other races.

| Total population | N |

| White | 244,597,669 |

| Black or African American | 45,612,523 |

| American Indian and Alaska Native | 5,643,919 |

| Asian | 21,408,058 |

| Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander | 1,399,393 |

| Some other race | 17,859,236> |

These norms are replicated elsewhere, such as computer algorithms that replicate racial and gender biases.36-38 Further, race correction factors, with their blatantly racist histories,39,40 are another example of racialized rules. In medicine, it is common to include a numerical weight when assessing clinical values to glomerular filtration rates (eGFR), spirometry readings, and other biomarkers.41 The presumption is that the clinical values of Black Americans differ from the values established for White and all other racial/ethnic groups. Such adjustments create inequities in access to care,42 reinforce essentialist (biological) ideas of race, and uphold the racial hierarchy by assuming that White patients constitute the reference population, and by implication, that Black patients are deviant.41

Actuarial science also uses these correction factors to predict estimates for life expectancies and future earnings. These estimates are then used by life insurance companies and even the court system. Consider the case where a judge had to rule on damages awarded to a child disabled due to lead paint,43 and the award was based on estimates of future earnings. The defendant’s attorney argued that the award should be less than half of the requested amount because the child was Latino and, according to actuarial projections, had lower earning potential than a White child. Racialized adjustments are common, with about 45% of forensic economists saying they would use race-specific data to estimate losses for a child’s death.44 Racialized adjustment perpetuates inequity because it literally devalues the lives of non-White Americans.44

Future Directions

Developing effective policies and interventions to address racial inequities in health requires an empirical literature that characterizes the nature of structural racism. We must carefully delineate institutional from structural racism and accelerate research on both. However, the greatest area for growth surrounds structural racism. To move this work forward, empirical work must focus on the ways in which social institutions are interconnected, reinforce one another’s actions, and shift the work of inequity from one institution to another. To build this literature, we provide several broad recommendations.

Research on race and health should be built on frameworks that explicitly outline the link between structural racism and health.7,9,45 These frameworks dictate that racism is more than interpersonal discrimination, but ubiquitous and systemic, permeating all institutions to create our racially hierarchical social structure with its resilient inter-institutional bonds.8,46 Empirically testing these frameworks will require innovative data, modeling approaches, and proper interpretation of race variables. We do not mean to say that all research must empirically study structural racism. Rather, we urge the field to consider that regardless of the measures or the specific hypothesis being tested, structural racism is the fundamental driver that underlies racial inequities.

A literature that transforms health equity will be driven by a research community that is diverse in background and experience. Our experiences inform who we are and what we see. This premise means that the research questions we ask, how we interpret the literature, and our basic ideas about the link between racial group membership and health are all limited by our personal biases.47,48 This means that science on inequality should accelerate when scholars from disadvantaged backgrounds are encouraged to trust and build their perspectives, rather than solely rely on research informed primarily by White perspectives.46-48 Because racialized rules are common knowledge, they are difficult to see. It is for this reason that scholars with critical viewpoints are needed. They can more easily spot hidden rules so that we can amend or eliminate them.

Finally, all work on race and health must be interdisciplinary. Health inequities have not subsided despite decades of research and interventions on health behaviors, health care access, and health insurance. We need to further integrate the work from fields such as ethnic studies. Further, we recommend the integration of knowledge from humanists who can inform our frameworks on structural racism. For example, philosophers Charles Mills49 and Achilles Mbembe6 provide us with an underlying understanding of the ways in which our broader society operates with regard to race. Similarly, historians provide us with information indicating that contemporary features of structural racism are not unfortunate happenstances, but the result of explicit racial policies to exclude non-White Americans.17,50,51 By fully integrating knowledge from other disciplines, we can create stronger frameworks on structural racism to understand how health inequities persist over historical time.52,53

In addition to these broad recommendations, we provide several specific ideas with respect to the measures and modeling approaches and encourage scrutiny of racialized rules. Indeed, the growth of administrative data has made it possible to create innovative and interdisciplinary measures of structural racism that include reflect numerous institutions. Previous work has focused on metropolitan and neighborhood racial residential segregation54 and immigration and criminal justice policies,55 including the negative spillover effects of these policies.56,57

Efforts currently underway are creating indices that reflect the multi-institutional nature of structural racism (similar to that which was created for structural sexism58). While these indices do not allow for direct tests of the bonds among institutions, the inclusion of measures that reflect multiple institutions implies that different institutions are operating at different times and places, and that it is the collection of the whole that matters for health inequities. We caution, however, that the use of macro-level measures does not mitigate the need for an explicit framework of structural racism.59

We also recommend expanding our modeling approaches to reflect the interconnected ways in which institutions operate. We can begin by estimating interactions between measures that reflect different institutions. Moreover, the study of interconnections lends itself naturally to complex systems analysis, including social network analysis and spatial network analysis.60,61 This research could include the study of formal contracts and policies across institutions, of people who sit on executive boards in multiple institutions, and the exchange of information, money, and other resources across institutions.62 Some studies have examined interconnections among groups that are promoting hate speech (eg, skinheads and neo-Nazis), but these studies could go further by connecting these groups to more formal institutions that support them indirectly, and ultimately, trace these connections back to health.

These modeling approaches can be used to examine the complexity within different and across components of institutions. For example, police officers may feel empowered to discriminate against non-White community members in part because the courts often rule in their favor. And as the case of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study reminds us, it was not long ago that medicine worked hand-in-hand with law enforcement to perpetuate racial inequities. Indeed, the issue of medical repatriation, which involves the deportation of undocumented immigrants, compels us to remain constantly vigilant of the role that medicine plays in social inequalities.63 Thus, research on policing should also be accompanied with simultaneous research on the courts and medicine. A key aspect of such research is to document how the institutions work together, focusing not only on formal transagency policies, but also on the informal day-to-day operations across these institutions.

We have argued that racialized rules help normalize and systematize racial inequity. Research should uncover the many invisible rules that are evident, so as to more systematically interrogate them, and ultimately, shatter the structure of inequality. This includes the presentation of data that implicitly sorts racial groups by importance, and the presumption that a White comparison group is needed in research. These everyday practices, although seemingly slight and mundane, accumulate to reinforce the racial hierarchy and perpetuate health inequities.

We can also examine racial correction factors and racialized algorithms, documenting and teaching about their usage and history as is done by the Mount Sinai Ichan School of Medicine.64 We must critically evaluate the utility of these adjustments, and either eliminate them or replace them with more accurate and precise non-racial correction factors, as has been done recently at the University of Washington School of Medicine with regard to glomerular filtration rate estimates.65 Similarly, we can evaluate how the banning of race adjustment in court settlements, as has been done recently in California via Proposition SB-41, may improve social and health inequities.

For too long, research on racial inequities has emphasized lower levels of analyses, and viewed individuals and institutions acting in isolation.7 By focusing our attention toward the broader structure of racism, and breaking the bonds of the bucky ball, we may make new strides in building health equity.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jennifer Alvidrez and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback. This article is based on a presentation on 5/22/17 at the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities meeting on Structural Racism/Discrimination – Impact on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Rockville, Maryland. We are grateful to the California Center for Population Research at UCLA (CCPR) for general support. CCPR receives population research infrastructure funding (P2CHD041022) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD).

References

- 1.Bell D. Faces at the Bottom of the Well: The Permanence of Racism. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Krieger N. Methods for the scientific study of discrimination and health: an ecosocial approach. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):936-944. 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300544 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pettigrew TF. The nature of modern racism in the United States. Rev Int Psychol Soc. 1989;2(3):291. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander M. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York, NY: The New Press; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.López IH. Dog Whistle Politics: How Coded Racial Appeals Have Reinvented Racism and Wrecked the Middle Class. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mbembé J-A, Meintjes L. Necropolitics. Public Cult. 2003;15(1):11-40. 10.1215/08992363-15-1-11 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gee GC, Ford CL. Structural racism and health inequities: old issues, new directions. Du Bois Rev. 2011;8(1):115-132. 10.1017/S1742058X11000130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):105-125. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonilla-Silva E. Rethinking racism: toward a structural interpretation. Am Sociol Rev. 1997;62(3):465-480. 10.2307/2657316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones CP. Levels of racism: a theoretic framework and a gardener’s tale. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(8):1212-1215. 10.2105/AJPH.90.8.1212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ray V. A Theory of racialized organizations. Am Sociol Rev. 2019;84(1):26-53. 10.1177/0003122418822335 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reskin B. The race discrimination system. Annu Rev Sociol. 2012;38(1):17-35. 10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145508 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Massey DS, Denton NA. American Apartheid: Segregation and the Making of the Underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Logan TD, Parman JM. The national rise in residential segregation. J Econ Hist. 2017;77(1):127-170. 10.1017/S0022050717000079 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bullard RD, Mohai P, Saha R, Wright B. Toxic Wastes and Race at Twenty: 1987-2007. Cleveland, OH: United Church of Christ & Witness Ministries; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothstein R. The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How our Government Segregated America. New York, London: Liveright Publishing Corporation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bullard RD. The legacy of American apartheid and environmental racism. St John’s Journal of Legal Commentary. 1993;(2):445- 474. https://scholarship.law.stjohns.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1460&context=jcred

- 19.Wacquant L. Deadly symbiosis: when ghetto and prison meet and mesh. Punishm Soc. 2001;3(1):95-133. 10.1177/14624740122228276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothwell JT. Racial enclaves and density zoning: the institutionalized segregation of racial minorities in the United States. Am Law Econ Rev. 2011;13(1):290-358. 10.1093/aler/ahq015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maantay J. Zoning law, health, and environmental justice: what’s the connection? J Law Med Ethics. 2002;30(4):572-593. 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2002.tb00427.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berry C. Land use regulation and residential segregation: does zoning matter? Am Law Econ Rev. 2001;3(2):251-274. 10.1093/aler/3.2.251 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galliher JF, Walker A. The puzzle of the social origins of the marihuana tax act of 1937. Soc Probl. 1977;24(3):367-376. 10.2307/800089 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shafer RP. Marihuana: A Signal of Misunderstanding; the Official Report of the National Commission on Marihuana and Drug Abuse. New York, NY: New American Library; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 25.United States Bureau of Justice . Drugs and Crime Facts. Last accessed Jan 6, 2021 from https://www.bjs.gov/content/dcf/enforce.cfm.

- 26.American Civil Liberties Union . The War on Marijuana in Black and White. New York, NY: American Civil Liberties Union; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colorado Department of Revenue . Marijuana sales reports. 2019. [Webpage]. Last accessed January 5, 2021 from https://www.colorado.gov/pacific/revenue/colorado-marijuana-sales-reports.

- 28.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID-19 in Racial and Ethnic Minority Groups. 2020; Last accessed January 5, 2021 from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html.

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Provisional Death Counts for Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19): Weekly State-Specific Data Updates [Website]. 2020. Last accessed January 5, 2021 from https://data.cdc.gov/NCHS/Provisional-Death-Counts-for-Coronavirus-Disease-C/pj7m-y5uh.

- 30.Kaiser Family Foundation . COVID-19 cases by race/ethnicity [Website]. 2020. Last accessed January 5, 2021 from https://bit.ly/3nrJfN6

- 31.Devastating COVID-19 rate disparities ripping through Pacific Islander communities in the United States. [Press Release] Pacific Islander Center of Primary Care Excellence, 04/07/20 2020. Last accessed January 10, 2021 from https://mk0picopce2kx432grq5.kinstacdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2020_0424-PICOPCE-COVID19-Press-Release.pdf

- 32.Gravelee C. Racism, not genetics, explains why Black Americans are dying of COVID-19. [Blog post] Scientific American. June 7, 2020. Last accessed January 6, 2021 from https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/voices/racism-not-genetics-explains-why-black-americans-are-dying-of-covid-19/

- 33.Gould E, Wilson V. Black workers face two of the most lethal preexisting conditions for coronavirus—racism and economic inequality. [Press Release] June 1, 2020. Last accessed January 6, 2021 from https://www.epi.org/publication/black-workers-covid/

- 34.Kim SR, Vann M, Bronner L, Manthey G. Which cities have the biggest racial gaps in COVID-19 testing access? [Blog Post] July 22, 2020. Last accessed January 11, 2021 from https://fivethirtyeight.com/features/white-neighborhoods-have-more-access-to-covid-19-testing-sites/.

- 35.Cineas F. Senators are demanding a solution to police stopping black men for wearing — and not wearing — masks. [Blog Post] April 22, 2020. Last accessed January 10, 2021 from https://www.vox.com/2020/4/22/21230999/black-men-wearing-masks-police-bias-harris-booker-senate

- 36.Noble SU. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York, NY: NYU Press; 2018. 10.2307/j.ctt1pwt9w5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajkomar A, Hardt M, Howell MD, Corrado G, Chin MH. Ensuring fairness in machine learning to advance health equity. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(12):866-872. 10.7326/M18-1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Obermeyer Z, Powers B, Vogeli C, Mullainathan S. Dissecting racial bias in an algorithm used to manage the health of populations. Science. 2019;366(6464):447- 453. https://doi.org/ 10.1126/science. aax2342 PMID:31649194 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 39.Braun L. Breathing Race into the Machine: The Surprising Career of the Spirometer from Plantation to Genetics. Minneapolis, MN: U of Minnesota Press; 2014. 10.5749/minnesota/9780816683574.001.0001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gee GC, Ro MJ, Rimoin AW. Seven reasons to care about racism and covid-19 and seven things to do to stop it. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(7):954-955. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305712 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305712 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vyas DA, Eisenstein LG, Jones DS. Hidden in plain sight – reconsidering the use of race correction in clinical algorithms. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(9):874-882. 10.1056/NEJMms2004740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eneanya ND, Yang W, Reese PP. Reconsidering the consequences of using race to estimate kidney function. JAMA. 2019;322(2):113-114. 10.1001/jama.2019.5774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soffen K. In person-injury cases, race and gender can be weighed in assessing future losses. Washington Post. October 25, 2016. Last accessed January 11, 2021 from https://wapo.st/35zqK3c

- 44.Brookshire ML, Luthy MR, Slesnick FLA. 2009 survey of forensic economists: their methods, estimates, and perspectives. J Forensic Economics. 2009;21(1):5-34. 10.5085/0898-5510-21.1.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hicken MT, Kravitz-Wirtz N, Durkee M, Jackson JS. Racial inequalities in health: Framing future research. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:11-18. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j. socscimed.2017.12.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 46.Ford CL, Airhihenbuwa CO. The public health critical race methodology: praxis for antiracism research. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(8):1390-1398. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lawrence CR. The word and the river: pedagogy as scholarship as struggle. South Calif Law Rev. 1991;65:2231-2298. https://bit.ly/3bGa7Gy. Accessed January 11, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Feagin JR. The White Racial Frame: Centuries of Racial Framing and Counter-Framing. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge; 2013. 10.4324/9780203076828 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mills CW. The Racial Contract. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press; 2014. 10.7591/9780801471353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones MS. Birthright Citizens: a History of Race and Rights in Antebellum America. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; 2018. 10.1017/9781316577165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Molina N. How Race is Made in America: Immigration, Citizenship, and the Historical Power of Racial Scripts. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gee GC, Hing A, Mohammed S, Tabor DC, Williams DR. Racism and the life course: taking time seriously. Am J Public Health. 2019;109(S1):S43-S47. 10.2105/AJPH.2018.304766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gee GC, Walsemann KM, Brondolo E. A life course perspective on how racism may be related to health inequities. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):967-974. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kershaw KN, Robinson WR, Gordon-Larsen P, et al. Association of changes in neighborhood-level racial residential segregation with changes in blood pressure among Black adults: the CARDIA Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(7):996-1002. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morey BN, Gee GC, Muennig P, Hatzenbuehler ML. Community-level prejudice and mortality among immigrant groups. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:56-66. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Novak NL, Geronimus AT, Martinez-Cardoso AM. Change in birth outcomes among infants born to Latina mothers after a major immigration raid. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46(3):839-849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wildeman C. Imprisonment and Infant Mortality. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Homan P. Structural sexism and health in the united states: a new perspective on health inequality and the gender system. Am Sociol Rev. 2019;84(3):486-516. 10.1177/0003122419848723 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hicken MT, Kravitz-Wirtz N, Durkee M, Jackson JS. Racial inequalities in health: framing future research. Soc Sci Med. 2018;199:11-18. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j. socscimed.2017.12.027 PMID:29325781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.El-Sayed AM, Galea S, eds.. Systems Science and Population Health. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2017. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/acprof:o so/9780190492397.001.0001 [DOI]

- 61.Kaplan GA, Roux AVD, Simon CP, Galea S. Growing Inequality: Bridging Complex Systems, Population Health, and Health Disparities. Washington, DC: Westphalia Press; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klein A. Slipping racism into the mainstream: A theory of information laundering. Commun Theory. 2012;22(4):427-448. 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2012.01415.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kuczewski M. Can medical repatriation be ethical? Establishing best practices. Am J Bioeth. 2012;12(9):1-5. 10.1080/15265161.2012.692433 10.1080/15265161.2012.692433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Leisman S, Karani, Reena. Can Math Be Racist? A Review of the Systemic Racism Inherent in EGFR and PFT Calculations. SGIM Forum 2020. Last accessed January 6, 2021 from https://connect.sgim.org/sgimforum/viewdocument/can-math-be-racist-a-review-of-the.

- 65.University of Washington . UW Medicine to exclude race from calculation of eGFR (measure of kidney function). [Press Release]. May 29, 2020. Last accessed January 11, 2021 from https://medicine.uw.edu/news/ uw-medicine-exclude-race-calculation-egfr-measure-kidney-function