Abstract

Racism is now widely recognized as a fundamental cause of health inequalities in the United States. As such, health scholars have rightly turned their attention toward examining the role of structural racism in fostering morbidity and mortality. However, to date, much of the empirical structural racism-health disparities literature limits the operationalization of structural racism to a single domain or orients the construct around a White/Black racial frame. This operationalization approach is incomprehensive and overlooks the heterogeneity of historical and lived experiences among other racial and ethnic groups.

To address this gap, we present a theoretically grounded framework that illuminates core mutually reinforcing domains of structural racism that have stratified opportunities for health in the United States. We catalog instances of structural discrimination that were particularly constraining (or advantageous) to the health of racial and ethnic groups from the late 1400s to present. We then illustrate the utility of this framework by applying it to American Indians or Alaska Natives and discuss the framework’s broader implications for empirical health research. This framework should help future scholars across disciplines as they identify and interrogate important laws, policies, and norms that have differentially constrained opportunities for health among racial and ethnic groups.

Keywords: Structural Racism, Structural Discrimination, Operationalization, Racial/Ethnic, Health

Introduction

Scholarship linking exposure to racism with multiple morbidities and premature mortality has rapidly expanded since the 1990s, such that racism is now widely recognized as a fundamental cause of disease.1 While much literature examines the influence of interpersonal discrimination on health, scholars are now attempting to better capture how racism operates structurally – within and across macro-level systems – to shape morbidity and mortality. Structural racism, however, is a complex construct that operates through many institutions across multiple domains, evolves over time, and manifests differently across racial and ethnic groups. The inherent complexity of structural racism makes operationalization difficult.

A few empirical studies have linked structural racism to stress, physical morbidity, and psychological well-being.2 Most of these studies used a single domain (eg, racial residential segregation) to operationalize structural racism within a Black/White racial hierarchical frame. Efforts to quantify the impact of structural racism on health are commendable. However, continuing to empirically study structural racism and health without first refining the construct in a theoretically grounded, racially and ethnically inclusive way will generate a body of scholarship that does not systematically capture the broad historical and contemporary impacts of structural racism on health in the United States. To address this challenge, we developed a theoretically grounded framework that illuminates core mutually reinforcing domains of structural racism that have stratified opportunities for health in the United States. We catalog instances of structural discrimination that were particularly constraining (or advantageous) to the health of racial and ethnic groups from the late 1400s to present. We then apply this framework to American Indians or Alaska Natives (AI/AN), detailing unique, period-specific policies, laws, and events to illustrate how these domains structure life chances for health among racial and ethnic groups.

In the following sections, we first describe the United States’ racialized social system that shapes racial and ethnic health disparities. Second, we introduce our framework and describe its utility. Third, we discuss the framework’s implications for empirical studies. Fourth, we reiterate the importance of comprehensive operationalization of structural racism in future health disparities research.

Background

Race is the social categorization of people into different groups based on real (eg, phenotypic characteristics) or imagined attributes. Similarly, ethnicity is the social categorization of people into groups based on common attitudes, beliefs, religion, language, and/or cultural “lifestyle.”3 Neither race nor ethnicity are grounded in actual biological distinctions, and both are historically and contextually fluid. Race and ethnicity are fundamental organizing principles of racialized societies with important social consequences for individuals. Racialized societies are economically, socio-politically, culturally, and ideologically structured around a hierarchy of “races,” with the dominant race possessing more power, resources, and opportunities than subordinate racial groups.4,5 While the dominant racial group is incentivized to maintain the established order, subordinate racial groups are motivated to transform (or improve their position within) the hierarchy.5 Racism is an ideology the dominant group employs to justify the assignment and reinforcement of other groups’ positions within a racial hierarchy. Racism can manifest through racial discrimination – exclusion or unjust treatment of groups of people on the basis of race or ethnicity. In the United States (and the greater Euro-Western world), the ideological belief that non-Whites are inferior to Whites shaped the creation and maintenance of racialized norms, and justified physical, emotional, and cultural violence, as well as domination and exploitation of non-White peoples.6

While racism functions across and within the micro, meso, and macro levels of society, structural racism is the “most important way in which racism shapes health.”4,p.107 Structural racism is a constellation of macro-level systems, social forces, institutions, ideologies, and interactive processes that generate and reinforce inequities among racial and ethnic groups.7 These components are integrated, reciprocally influence each other across multiple domains, and evolve in function and form over time.8 Structural racism can manifest through structural discrimination – institutional practices and policies that explicitly or implicitly differentially impact, or harm, non-dominant groups.9,10 Together, these components generate health disparities by differentially constraining the life chances and choices available to racial and ethnic groups, as well as the flexible resources necessary for the prevention, detection, and treatment of disease.1

A binary (White/Black) schema has historically dominated the framing of racial stratification in the United States,6 but other groups have resided in the United States since its pre-conception (ie, AI/AN). The United States’ racial structure has also continuously evolved across waves of immigration (eg, incorporation of Chinese and Japanese immigrants as Asian Americans). Through intermarriage and close social proximity to those already categorized as White or Black, some groups assimilated into these pre-established racial categories over time11; other pan-ethnic groups were incorporated as new races falling somewhere in between.12 The racial hierarchy will continuously shift as the United States becomes more diverse. Some predict this hierarchy will evolve from a bi-racial to a tri-racial system of Whites, honorary Whites (eg, light-skinned Asians), and collective Blacks (eg, dark-skinned Latinxes).13 While we acknowledge the evolving conceptualization of racial and ethnic groups in the United States, here we utilize the US Office of Management and Budget (OMB)’s racial and ethnic groups formalized in the decennial Census: White, Black or African American, American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, and Hispanic/Latinx as a pan-ethnicity.

Much of the empirical work on structural racism, and the operationalization of structural racism itself, is also oriented around a White/Black racial frame. This framing ignores how racist processes structure the lives and health of other racialized groups. Moreover, the multisystemic nature of structural racism makes it insidious for health. While empirically examining a single domain of structural racism (eg, residential segregation) is beneficial, labeling that single domain as structural racism downplays the existence and treacherous impact of the broader racial system at play.

Whites have remained the dominant racial group in the United States despite the continuous evolution of the definition of race, the form of structural racism, and racialization processes. Structural racism catalyzed initial health disadvantages among non-Whites across several mutually reinforcing domains (eg, housing market, labor market, education system). These disadvantages compounded through generations, fostering durable racial and ethnic disparities in morbidity and mortality observed today. This, and the limited operationalization of structural racism in health scholarship to date, necessitates a more comprehensive strategy for operationalizing structural racism in minority health research that facilitates thinking across the unique socio-historical experiences of all US racial and ethnic groups.

A Framework for Operationalizing the Construct of Structural Racism

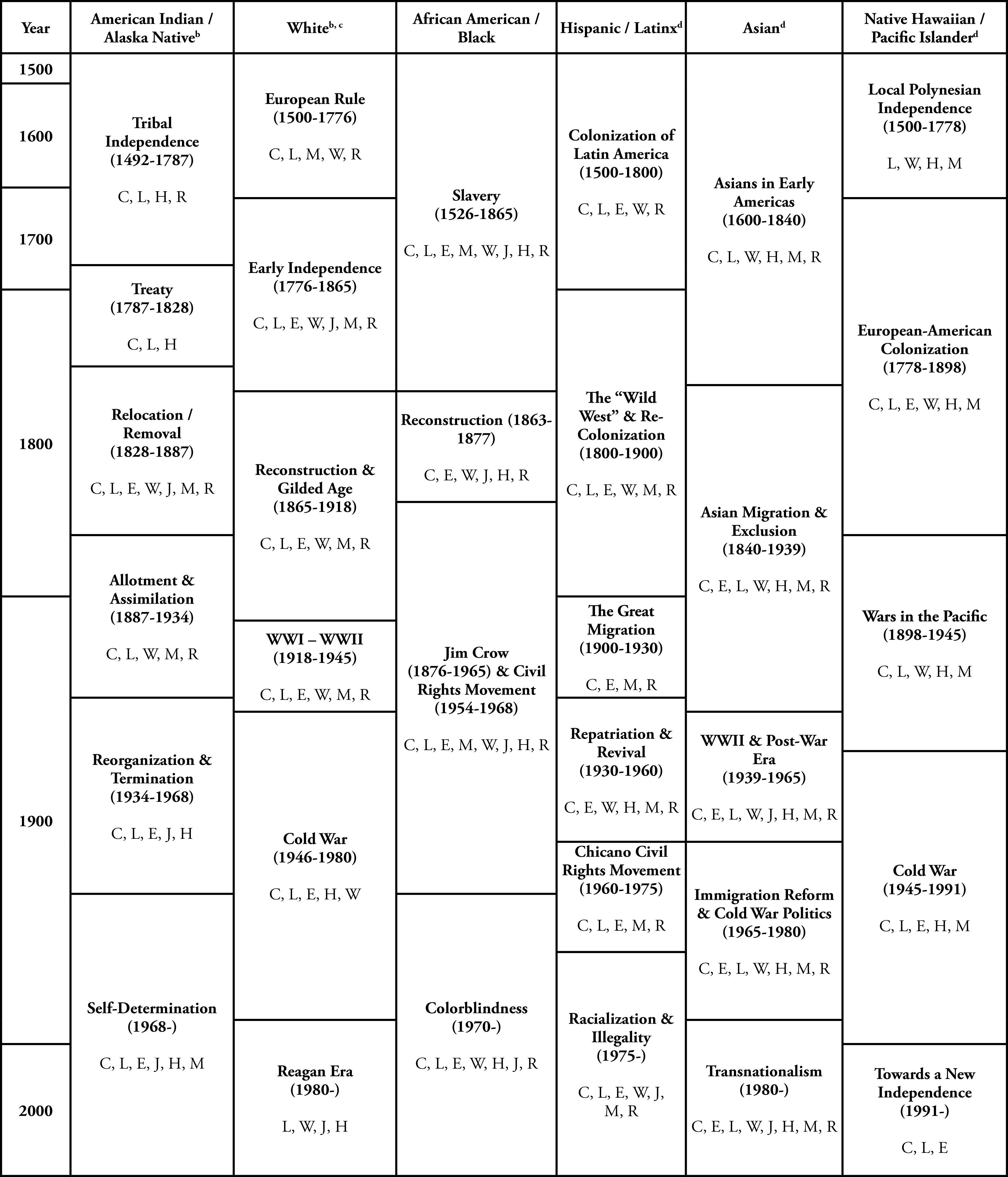

We introduce a theoretically grounded framework that illuminates how racism has operated structurally to stratify opportunities for health across US racial and ethnic groups. We illuminate core mutually reinforcing domains of structural racism by cataloging instances of structural discrimination that were particularly constraining (or advantageous) to the health of racial and ethnic groups from the late 1400s to present (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Framework for operationalizing structural racism for health research in the United States.

a. Enactment or enforcement of racist policy, laws, events, or norms regarding: C, Civil / Political Rights; L, Land / Housing / Neighborhoods; E, Education; W, Jobs / Benefits / Wealth; J, Justice System; H, Health; M, Migration and Movement; and R, Racial Climate.

b. See Figure 2 for additional details for American Indians / Alaskan Natives and Whites.

c. Importantly, the domains listed for Whites primarily represent a structural advantage. Although several European ethnic immigrant groups (eg, Irish, Polish, Jewish, German, etc.) experienced discrimination and unfair treatment upon arrival to the United States, their eventual racialization into the White racial group enabled them to access benefits associated with whiteness earlier than non-White groups.

d. Domains of structural racism differentially affected various ethnic subgroups within and across these eras.

To develop this framework, we searched the Web of Science database between 29 November and 4 December 2019 for literature describing historical or political events with structurally racist implications, or federal or state policies illustrative of structural racism. Our searches generated scholarship focused on the period from 1970 to present. Therefore, we conducted a hand search of academic books describing the history of each OMB racial and ethnic group. We extracted policies, laws, and events with implications for health and wellbeing for inclusion in our framework. Guided by Bailey and colleagues,14 we categorized these policies and events into eight mutually reinforcing domains of structural racism: civil and political rights (including voting rights and citizenship); land / housing (including neighborhoods); education; jobs / benefits / wealth; justice system; health (including health care); migration and movement (including immigration, forced removal, and limited mobility); and racial climate. Each of these domains work together to differentially constrain access to health-protective material resources (eg, nutritious food, clean water, safe shelter), flexible resources (ie, money, knowledge, power, prestige, social networks, freedom)1 and valued societal opportunities, resulting in disparate life chances and health-related choices across racial and ethnic groups.

Broadly, scholars can employ this framework as a starting point when operationalizing structural racism to identify existing gaps in our knowledge of structural racism and health. For example, the health impacts of the Justice System (J) post-1980 are currently better documented among Blacks or African Americans and Hispanic/Latinxes than among Asians. Our framework can also facilitate development or identification of period-relevant, group-specific measures of structural racism. For example, a scholar studying the health impacts of school segregation (E) on Blacks or African Americans and Hispanic/Latinxes from the late 1800s-1960s could measure segregation using the number of exclusionary policies based on race or language, respectively, enacted in that period. Moreover, our framework can help situate findings within greater socio-historical contexts. An analysis of references to COVID-19 as the “China Virus” by political leaders, for example, should mention the “perpetual foreigner myth,” an idea that emerged as early as the 1890s and gained prominence in the 1960s (R). Finally, our framework can inform study design. To understand the psychological consequences of atomic bomb testing during the Cold War, scholars could, for example, extract data from hospital records and conduct in-depth interviews with Pacific Islander forced migrants and their descendants (M, L). Scholars can use this framework to examine one or more policies within a single domain in a single period, one or more policies in a single domain across periods, several policies across multiple domains in a single period, or how change in one domain has had intergenerational implications. Moreover, scholars can include multiple racial and ethnic groups to identify patterns of structural racism that impacted health within and across populations.

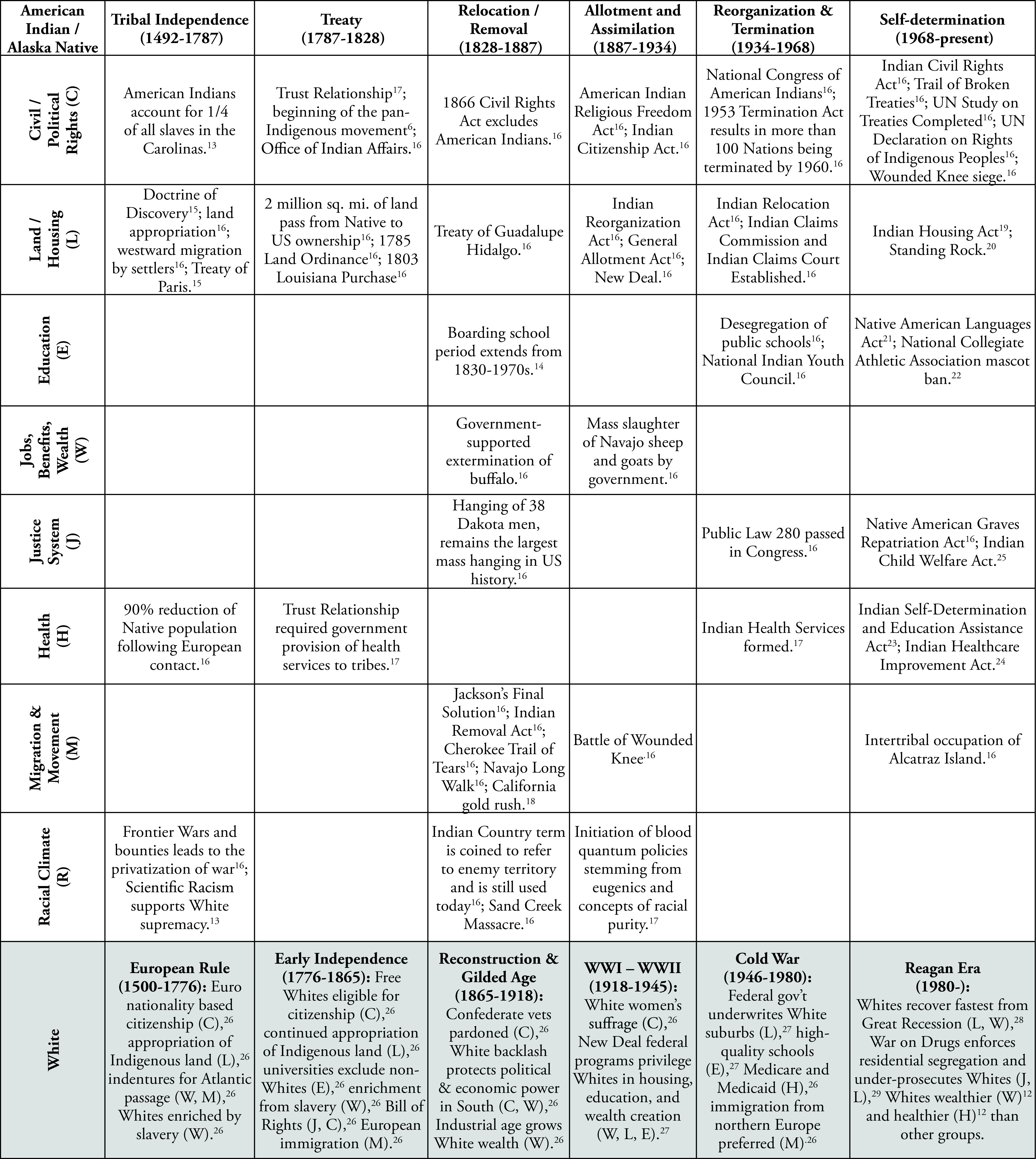

While outlining all of the structurally racist policies, laws, and events for each racial and ethnic group in Figure 1 is beyond the scope of this article, we illustrate the utility of our framework by applying it to AI/AN as compared with Whites (Figure 2). We expanded each era of racism for AI/AN, listing period-specific structural policies and events across each of the eight domains. We then use Figure 2 to enrich our understanding of the COVID-19 health crisis currently unfolding in the Navajo Nation.

Figure 2. Operationalization of structural racism for health of American Indians / Alaska Natives (vs Whites).

Systemic racism underlies the high COVID-19 transmission and mortality observed on the Navajo reservation. To make way for White settlers, the US Cavalry forcefully relocated the Diné (Navajo) from their traditional homelands in Arizona to internment camps in New Mexico from 1863-1866; thousands died during this “Long Walk” (M). The 1868 Treaty of Fort Sumner (L) adversely impacted the physical and mental health of the Navajo through losses of traditional ecological knowledge, food and trade systems, and wealth, and forced the Navajo to rely on the US government for food and other resources15 with implications that continue to reverberate today. The 1938 Mineral Development Act (W), which enabled the leasing of reservation land for mining, increased residents’ exposure to toxins and exacerbated wealth inequality within and outside of the reservation. Simultaneously, the 1930s Livestock Reduction Program (W) limited traditional familial wealth by reducing the number of livestock a family could own.15

Structural racism enacted across generations in the form of forced migration, lost traditional knowledge, and wealth extraction increased the Navajo’s vulnerability to COVID-19. Today, a significant proportion of reservation residents live in food deserts and lack water, electricity, and broadband (W). Structural racism begets poverty,1 which has made COVID-19 prevention strategies (eg, frequent hand-washing, sheltering in place, remote work/schooling) a challenge for the Navajo, while traditional multigenerational households render social distancing impractical.16 Structural racism restricts access to resources necessary to avoid disease.1 Historically poor access to nutritious food contributed to high prevalence of diabetes, heart disease, and kidney disease (H) in the Navajo population, increasing the risk of death from COVID-19.17 Moreover, the underfunded and understaffed Indian Health Service (H), combined with distrust of medical and public health systems among the Navajo (H, R) have contributed to low COVID-19 testing rates and insufficient treatment for those who contract COVID-19 on the reservation. Employing our framework to analyze the impact of COVID-19 on the Navajo reservation reveals that high COVID-19 transmission and mortality on the Navajo reservation is not by chance; centuries of structural racism created the conditions for COVID-19 to thrive.

Framework Implications for Empirical Study

The underlying motivation for this work is to encourage health scholars to improve operationalization of structural racism by:

1) acknowledging the domain(s) under study as part of a broader multi-dimensional system of structural racism;

2) expanding scholarship to include non-White and non-Black racialized groups; and

3) assessing structural racism in specific context for all racial and/or ethnic group(s) under study. This approach can guide development of a literature that illuminates similarities and differences in the development of structural heath (dis)advantage between racial and ethnic groups across generations.

We list additional implications of this framework for empirical study below:

1) Social constructs (eg, education, wealth, neighborhoods, etc.) may not operate equivalently as health-related exposures across racial and ethnic groups and may therefore warrant different operationalizations. Moreover, different racial and ethnic groups have different historical-evolutionary timelines. For example, the temporal gap between the provision of legal protections and social programs first to Whites and then to non-White groups (Figure 1) represents a “structural advantage.” Scholars should explicitly study favorable morbidity and mortality outcomes observed among White individuals, families, and communities in contrast to non-White groups through this lens. Quantitative scholars should also consider whether between-group and/or race-stratified statistical models are most appropriate when studying structural racism and health.

2) This framework also provides a starting point for qualitative and mixed-methods scholars interested in broadening our knowledge of the historical and sociocultural determinants of population health. For example, reproductive health scholars could triangulate analyses of historical documents with the collection and analyses of in-depth interviews and quantitative surveys to empirically link high maternal mortality among Black or African American women to the era of slavery.

3) Scholars’ ability to empirically apply this framework rests on the quality of available data. Collecting data on race and ethnicity as a single ethno-racial variable (eg, “White/Black/Hispanic/Other”) can mask important heterogeneity in the effects of racist laws, policies, and norms on the health of racial and ethnic groups. When possible, data collectors should ask separate questions for race, ethnicity, nativity, and year of immigration, and be attentive to the differential health impacts of structural racism based on the intersections of these ethno-racial variables (eg, third-generation Chinese Americans vs first-generation Hmong Americans). Those conducting secondary data analysis should note the limitations of single ethno-racial variables in their analyses and interpretation of results.

4) We encourage scholars to frame contemporary health disparities as the cumulative impact of centuries of systemic exclusion from legal protections, and restricted access to opportunities and resources that are protective of health. We also encourage health scholars to explicitly acknowledge that White supremacy exists and contributes to the health advantages observed among Whites in the framing of their research.

5) While this framework is specific to structural racism and race structures, it interacts with other axes of oppression such as gender, class, sexuality, and disability.3Thus, the health impacts of structurally racist laws, policies, and norms likely vary within racial and ethnic groups (eg, Black Latinx men and women vs White Latinx men and women). Intersectional approaches should aid future empirical work on the health impacts of structural racism.

6) Health scholars should consider structural racism as not just the enactment of policies, laws, and norms that systematically disadvantage one racial group over another, but also the failure to implement and enforce laws, policies, and norms that mitigate and/or reverse racist harms enacted in the past.

Limitations

This framework is not without limitations. First, we organized our literature search and framework around the US OMB standards for data on race and ethnicity, which commonly guide racial and ethnic data collection in the United States. These categories, however, can mask important disparities within groups and exclude oppressed racialized groups (eg, Middle Eastern Americans). Moreover, we refer to the Indigenous people of the unceded territory of the continental United States and Alaska as American Indian or Alaska Native (AI/AN), in keeping with the OMB convention. However, whenever possible, Indigenous peoples should be referred to by specific tribes. The “AI/AN” category encompasses more than 570 federally recognized tribes, state recognized tribes, and unrecognized tribes. The unique geographic, historical, and sociopolitical experiences of these tribes are impossible to illuminate in a single figure; therefore, Figure 2 presents policies and events that impacted AI/AN as a whole. Researchers studying specific tribal nations are encouraged to use the framework to also identify tribe-specific events and policies. Similarly, the listed domains of structural racism in Figure 1 do not equally apply to all ethnicities within the Black or African American, Hispanic/Latinx, Asian, or Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander groups. International politics, immigration, and changing forms of the racial hierarchy within and across eras resulted in differential effects of structurally racist policies on ethnic subgroups. Scholars interested in how structural racism affects these groups should consider the heterogeneity within the US OMB racial and ethnic categories. Second, the eight domains of structural racism identified here may not hold the same meaning for all racial and ethnic groups. For example, while AI/AN were forced to relocate, free movement of Blacks or African Americans was severely restricted during the periods of slavery and Jim Crow. Third, the policies, laws, and norms captured in Figure 2 are not necessarily the sole structurally racist factors operating during those periods. Fourth, we noted a general lack of published literature regarding the effects of structural racism on Asian Americans, Native Pacific Islanders, and Native Hawaiians. This gap merits further population-specific research.

Conclusion

We outline a framework for operationalizing structural racism as it relates to health disparities research in the United States. Carefully considering the experiences of different racial and ethnic populations across time is important for generating a literature that captures the varying effects of structural racism on health both historically and today. The framework presented here should help future scholars across disciplines identify and question important laws, policies, and norms that have differentially constrained opportunities for health across racial and ethnic groups.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Robert A. Hummer for his thoughtful feedback on this commentary. This work was supported by the Population Research Infrastructure Program (P2CHD050924), the Population Research Training Grant (T32HD007168) and the Interdisciplinary Training in Life Course Research Training Grant (T32HD091058) awarded to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Additionally, this work was supported by the Biostatistics for Research in Environmental Health Training Grant (T32ES007018) awarded to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Phelan JC, Link BG. Is racism a fundamental cause of inequalities in health? Annu Rev Sociol. 2015;41(1):311-330. 10.1146/annurev-soc-073014-112305 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Groos M, Wallace M, Hardeman R, Theall KP. Measuring inequity: a systematic review of methods used to quantify structural racism. J Health Dispar Res Pract. 2018;11(2):13. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/jhdrp/vol11/iss2/13 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Omi M, Winant H. Racial Formation in the United States. 3rd ed. New York, NY: Routledge; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams DR, Lawrence JA, Davis BA. Racism and health: evidence and needed research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2019;40(1):105-125. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040218-043750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonilla-Silva E. Rethinking racism: toward a structural interpretation. Am Sociol Rev. 1997;62(3):465-480. 10.2307/2657316 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mills CW. The Racial Contract. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Powell JA. Structural Racism: Building upon the Insights of John Calmore. N C LAW Rev. 2008;86(3):791. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reskin B. The race discrimination system. Annu Rev Sociol. 2012;38(1):17-35. 10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145508 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pincus F. Discrimination comes in many forms: individual, institutional, and structural. Am Behav Sci. 1996;40(2):186-194. 10.1177/0002764296040002009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Link BG, Schomerus G. Public attitudes regarding individual and structural discrimination: two sides of the same coin? Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:60-66. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j. socscimed.2013.11.014 PMID:24507911 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Yancey G. Who Is White? Latinos, Asians, and the New Black/Nonblack Divide. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien E. The Racial Middle; Latinos and Asian Americans Living beyond the Racial Divide. New York: NYU Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonilla-Silva E, Dietrich DR. The Latin Americanization of Racial Stratification in the U.S. In: Hall RE, ed. Racism in the 21st Century: An Empirical Analysis of Skin Color. New York, NY: Springer New York; 2008:151-170, 10.1007/978-0-387-79098-5_9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(10077):1453-1463. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunbar-Ortiz R. An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States. Boston: Beacon Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kovich H. Rural Matters - Coronavirus and the Navajo Nation. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(2):105-107. 10.1056/NEJMp2012114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sequist TD. The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color. N Engl J Med Catalyst. July, 2020. https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/ CAT.20.0370

- 18.Hine DC, Hine WC, Harrold S. The African-American Odyssey. Vol I. 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilkins DE, Lomawaima TK. Uneven Ground: American Indian Sovereignty and Federal Law. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cerasano HE. The Indian Health Service: barriers to health care and strategies for improvement. Georget J Poverty Law Policy. 2017;24(3):421-439. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Native American Rights Fund . Trigger Points: Current State of Research on History, Impacts, and Healing Related to the United States’ Indian Industrial/Boarding School Policy. Boulder, Colorado: Native American Rights Fund; 2019:1-104. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lindsay BC. Murder State: California’s Native American Genocide, 1846-1873. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press; 2012. https://doi.org/ 10.2307/j. ctt1d9nqs3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Title II: Assisted Housing for Indians and Alaska Natives. Public Law 100-358. Statute 102 676, Code 42 U.S.C. 1437aa. June 29, 1988.

- 24.McCollum Letter Urges Greater Army Corps Consultation with Standing Rock Sioux on Dakota Access Pipeline. Press Release. September 14, 2016. Last accessed December 14, 2020 from https://mccollum.house.gov/press-release/mccollum-urges-further-army-corps-consultation-standing-rock-sioux-dakota-access

- 25.Warhol L. Creating official language policy from local practice: the example of the Native American Languages Act 1990/1992. Lang Policy. 2012;11(3):235-252. 10.1007/s10993-012-9248-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Staurowsky EJ. “You know, we are all Indian”: exploring white power and privilege in reactions to the NCAA Native American mascot policy. J Sport Soc Issues. 2007;31(1):61-76. 10.1177/0193723506296825 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cunningham PJ. Access to care in the Indian Health Service. Health Aff (Millwood). 1993;12(3):224-233. 10.1377/hlthaff.12.3.224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Indian Health Care Improvement Act, 25 U.S.C. 1601-1672. Last accessed December 14, 2020 from https://www.ihs.gov/ihcia/

- 29.Eliassen M. Indian Child Welfare Act. In: Cousins LH, ed. Encyclopedia of Human Services and Diversity. Vol 1. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 2014:701-702. [Google Scholar]