Abstract

Chylothorax is generally seen due to iatrogenic injury to the thoracic duct during thoracic or neck surgery. It can also be encountered secondary to chest trauma either blunt or penetrating. Percutaneous thoracic duct embolisation is an alternative to surgical treatment and is considered an effective and safe minimally invasive treatment option for chylothorax with a success rate of about 80%. We present a case of blunt trauma to the chest with chylothorax, which was successfully managed with transvenous retrograde thoracic duct embolisation.

Keywords: trauma, interventional radiology, general surgery, vascular surgery

Background

The thoracic duct is the largest lymphatic duct in body, that carries 1 to 2 L of chyle per day from 75% of the body area.1 Chylothorax is defined as the leakage of chyle into the pleural cavity. Leakage of chyle is generally secondary to chest trauma either blunt or penetrating, and iatrogenic thoracic duct injury during thoracic or neck surgery.2 Chylothorax leads to loss of amino acids, immunoglobins, fat, vitamins, electrolytes and fluids into the pleural space and can lead to malnutrition, pulmonary complications, immunosuppression, sepsis and death. Though ligation of the thoracic duct is the definitive treatment, surgery is associated with a morbidity of up to 38% in the form of prolonged ventilation, air leak, respiratory failure and atrial fibrillation.3 Recently percutaneous thoracic duct embolisation has been considered an effective and safe minimally invasive treatment option for chylothorax with a success rate of about 80%.4–8 We present a case of traumatic chylothorax, which was successfully managed with retrograde thoracic duct embolisation.

Case presentation

A 50-year-old male patient with a previous unremarkable medical history presented to our trauma centre as a referred case from another hospital with persistent large output (1.5 to 2 L per day) from the intercostal tube drain. Twenty-five days prior to admission to our institution, the patient suffered a road traffic injury and was managed initially at a local hospital. A right-sided 32Fr intercostal tube drain was placed in view of haemothorax. As per the medical records available with the patient, the initial intercostal tube drain output was 500 mL and sanguineous in nature. Intercostal tube drain output gradually increased up to a maximum of 2.5 L per day and its colour turned to cloudy white. Treating doctors suspected a thoracic duct injury with right-sided chylothorax and referred him to our centre for further management.

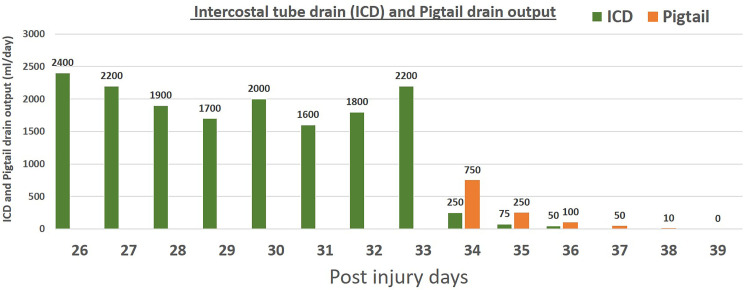

We confirmed the diagnosis of chylothorax by biochemical analysis of the fluid drained from the right thoracic cavity. Initially, we adopted a non-operative management approach which included nil by mouth, intravenous fluids, total parenteral nutrition (TPN) of 2500 kcal per day and a somatostatin analogue (injection octreotide 0.1 mg subcutaneously every 8 hourly). After 2 days of non-operative management, intercostal tube drain output decreased to 1000 mL per day with a change in its colour from cloudy white to serous. But this trend did not continue and the intercostal tube drain output increased again to reach 2200 mL/day by the fifth day of non-operative management. Finally, in view of failed non-operative management the patient was planned for embolisation of the thoracic duct. A repeated contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) scan of the torso revealed loculated fluid collection in the right pleural cavity. The ultrasonography-guided pigtail drain was placed and the collection was drained. The daily output of intercostal tube drain and pigtail drain is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Showing the daily output of intercostal tube drain and pigtail drain.

Investigations

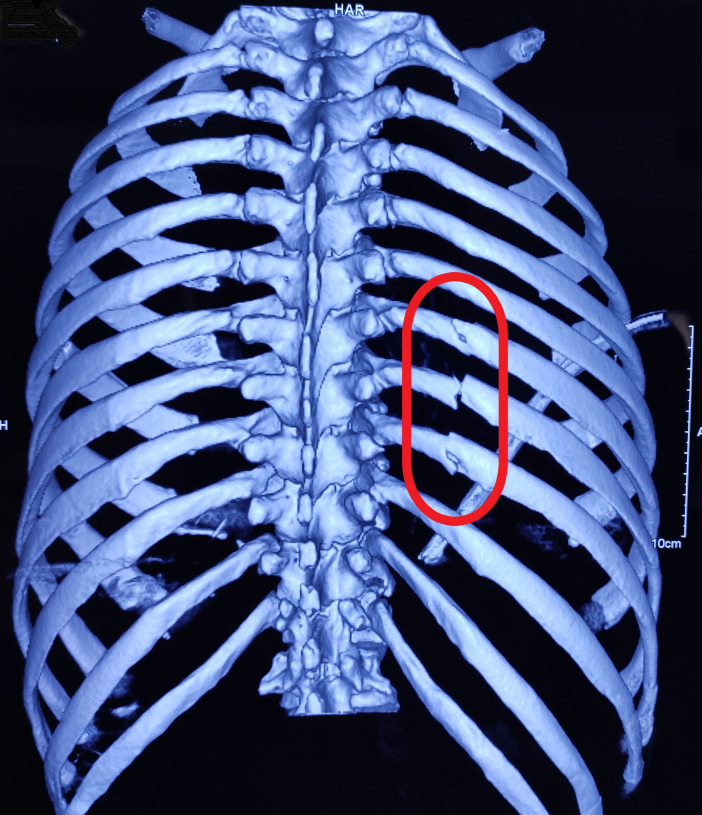

CECT scan of the torso was done which showed fracture of the caput of 7th, 8th and 9th ribs (figure 2) with moderate haemothorax on the right-side, fracture of 4th, 5th and 10th rib on the left-side and grade III liver injury. Biochemical analysis of the fluid drained from the right thoracic cavity revealed; pH 7.54, specific gravity 1.014, cholesterol to triglyceride ratio 0.9, high triglyceride levels of 250 mg/dL and chylomicrons on electrophoresis. Colour of the fluid was milky white.

Figure 2.

CT scan of the chest showing fracture of caput of right-side 7th to 9th ribs (red circle).

Differential diagnosis

The intercostal tube drain output was initially sanguineous in nature indicating haemothorax, later the colour turned to cloudy white. Chylothorax was confirmed by biochemical analysis of the fluid drained from the right thoracic cavity. Pyothorax was ruled out by culture of the fluid from intercostal tube drain.

Treatment

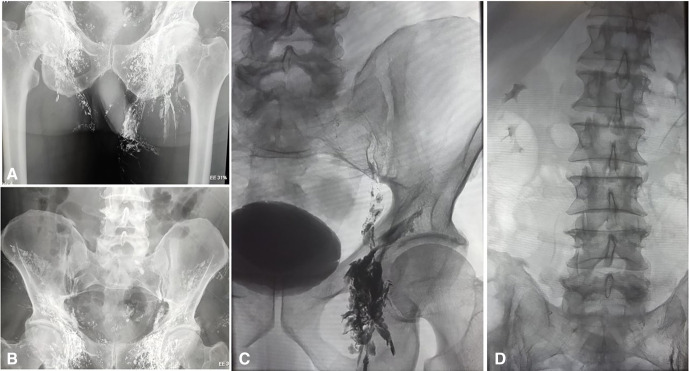

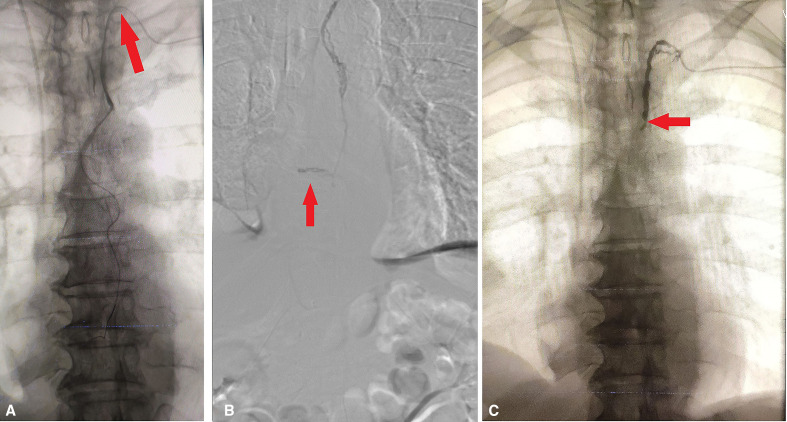

In the angiography suite, the patient was put in the supine position, bilateral inguinal areas and left arm and neck were painted and draped. Lipiodol (poppy seed oil used as a radio-opaque contrast agent, Guerbet, France) was injected in bilateral inguinal lymph nodes at the junction of cortex and medulla under ultrasonography and fluoroscopic guidance. The lymphangiography was done to follow the passage of the lipiodol into the inguinal, iliac and retroperitoneal lymph nodes over 4 hours (figure 3). Even after 4 hours, cisterna chyli did not opacify, hence we resorted to doing retrograde cannulation of the thoracic duct through the left brachial vein. The left brachial vein was punctured under ultrasonography guidance followed by cannulation of the thoracic duct in a retrograde manner, at the junction of the left internal jugular vein and left subclavian vein, using a 5Fr angiographic catheter (Cook, Bloomington, Indiana, USA) and 0.032” Terumo guidewire (TERUMO, Tokyo, Japan) under fluoroscopic guidance (figure 4A). A 2.7F coaxial microcatheter system with 0.018” wire (Progreat, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) was used for access into the thoracic duct. The thoracic duct injury was confirmed with leakage of iohexol, a contrast medium (Omnipaque, GE Healthcare, Bengaluru, India) (figure 4B), which was followed by embolisation of leak site as well as thoracic duct using 0.4 mL of 30% n-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate glue (Endocryl; Samarth Life Sciences, Mumbai, India). Post embolisation there was no further contrast leak identified (figure 4C).

Figure 3.

Lymphangiography following the passage of lipiodol into inguinal lymph nodes (A), iliac lymph nodes (B) and retroperitoneal lymph nodes (C and D)

Figure 4.

Angiography showing (A) cannulation of the thoracic duct (red arrow), (B) thoracic duct injury with extravasation of contrast (red arrow), (C) after thoracic duct embolisation no contrast leak was found (red arrow).

Outcome and follow-up

On the first day after the procedure, intercostal tube drain output was 250 mL which gradually decreased further and was nil on fourth day after the procedure. The intercostal tube drain was removed on fourth day of the procedure and the pigtail drain was removed on sixth day after the procedure. The total hospital stay was 2 weeks. He is on regular follow-up and doing well at 12 months of follow-up.

Discussion

According to Brescia9 the chylothorax was first described in 1633. Chylothorax is most commonly iatrogenic and 80% of thoracic duct injuries occur during surgeries such as pneumonectomy or oesophagectomy.2 Less commonly, thoracic trauma also causes thoracic duct injury leading to chylothorax. Various possible mechanisms contributing to such an injury in blunt thoracic trauma can be categorised as (1) shearing of the right diaphragmatic crus leading to shearing of the thoracic duct, (2) flexion and hyperextension of the thoracic spine especially in young patients causing stretching of the thoracic duct beyond its limits leading to its rupture and (iii) fractures of thoracic vertebrae or ribs in the dorsal aspect of chest may also cause thoracic duct injury directly.10 11 In our case, the cause of thoracic duct injury was possibly due to fractures of the caput of right-sided 7th, 8th and 9th ribs lying in immediate relation to thoracic duct.

There is generally a latency period of 2–7 days between the time of injury and onset of clinical evidence of chylothorax, provided the injury is not a major one.12 In our case, chyle started appearing in the drain from third day of injury. Milano et al13 have given two possible explanations for this delayed presentation. First, the chyle slowly collects in the posterior mediastinum until it ruptures and gets collected in either side of the pleural cavity depending on the level of injury. Second, since there occurs an interruption in the normal diet of a patient after trauma, the initial production of chyle is less, which causes a delay in the recognition of chylothorax.

Chylothorax is almost always an incidental finding and presents most often as pleural effusion that is indistinguishable from haemothorax on standard chest X-ray. Confirmation of the diagnosis of chylothorax can be made by doing biochemical analysis of pleural fluid: specific gravity ≥1.012, triglycerides >100 mg/dL, cholesterol to triglyceride ratio <1 and electrophoresis showing chylomicrons. Management of chylothorax is broadly divided into three types: non-operative management, non-operative intervention and operative management.

Non-operative management

Non-operative management consists of pleural fluid drainage by intercostal tube drain placement, nil per mouth, intravenous fluids, TPN, a diet including medium-chain triglycerides and somatostatin and its analogues. If the daily output of chyle is low (<500 mL/day), non-operative management may be effective and may seal the leak in 27% to 100% of patients. High output (>1 L/day) chylothorax poorly responds to non-operative management and demands other modalities of treatment. Selle et al concluded that if the daily output of chyle exceeds more than 1500 mL in adults or 100 mL per year of age in children for 5 days or when the daily output of chyle has not diminished for 2 weeks of non-operative management, operative intervention is indicated.14 15 Other authors have also recommended surgery if 2 weeks of non-operative management fails.9 16

Non-operative intervention

Lymphangiography and thoracic duct embolisation have high efficacy and a favourable safety profile. It is an attractive alternative to surgical ligation of the thoracic duct.17 18 The intranodal lymphangiography with thoracic duct embolisation has a technical and clinical success rate of 100% and 87%, respectively.7 The introduction of ultrasonography-guided intranodal lymphangiography for thoracic duct embolisation provided an excellent alternative to pedal lymphangiography.6 19 It promised relative technical ease and less procedural time, as the groin nodes are superficial and easily identifiable on ultrasonography. In the present case, lipiodol was injected in bilateral inguinal lymph nodes under ultrasonography and fluoroscopic guidance. The passage of lipiodol into the inguinal, iliac and retroperitoneal lymph nodes was followed over 4 hours. However, cisterna chyli did not opacify and hence retrograde cannulation of the thoracic duct through the left brachial vein was done. This procedure results in rapid, effective and long-lasting resolution of symptomatic chyle leak. Deployment of the coils and n-butyl cyanoacrylate glue during the thoracic duct embolisation occludes the thoracic duct effectively than the coil alone. The benefits of using both coils and glue had been validated by the results of a series of 109 patients, which also shows higher failure rates when the coil was used alone.5 In the present case, thoracic duct embolisation was successfully done by using n-butyl cyanoacrylate glue only. The thoracic duct embolisation can lead to contralateral chylothorax due to thoracic duct injury, or intraperitoneal bleeding in patients with coagulopathy. Delayed complications like chronic diarrhoea, lower extremity and abdominal swelling have also been reported in patients who had undergone thoracic duct embolisation.20 These chronic complications suggest that physiological alterations related to pressure changes in lymphatic channels may contribute to protein-losing gut enteropathy and the pedal lymphangiography, disrupts peripheral lymphatics and result in extremity oedema. These complications are also common after surgical ligation of the thoracic duct.

Transvenous retrograde cannulation

Retrograde transvenous thoracic duct embolisation was first described by Mittleider et al.21 In contrast to antegrade thoracic duct embolisation, there are only a few cases reported on retrograde transvenous thoracic duct embolisation.21–24 With the retrograde transvenous approach the introducer sheath is placed in the left basilic vein of the upper arm, the left brachial vein or the right femoral vein.25 The thoracic duct is entered at the junction of the internal jugular vein and subclavian vein.25 The catheter is introduced into the thoracic duct and the site of leak is identified prior to embolisation. The termination point of the thoracic duct can have various locations such as the internal jugular vein, jugulo-subclavian angle or subclavian vein and is generally located within 2 cm of the jugulo-subclavian angle.26

Retrograde transvenous thoracic duct embolisation may be technically challenging as it requires retrograde intubation of the lymphovenous junction with the ostial valve. However, this approach is safe, less invasive and does not require any special instrument and can be done under local anesthesia. Gahide and Sam27 had faced several points of resistance while cannulating the thoracic duct. As per their report whenever a point of resistance was faced, the patient was asked to take a deep breath and the microcatheter was pushed further. This technique greatly helped the progression of the microcatheter and the cisterna chyli was reached within a matter of minutes. They hypothesised that the negative thoracic pressure induced by inhalation opens the thoracic duct as it does with the venous system. Kariya et al22 studied the transvenous retrograde thoracic ductography in a series of 13 patients. They divided the thoracic duct into the thoracic part and the cervical part. The thoracic part runs in the caudal thoracic cavity from the level of intersection with the brachiocephalic vein and the cervical part runs in the cervical area from the level of intersection with the brachiocephalic vein to the vein on the cranial side. With respect to the shape of the cervical part, simple type was defined as the presence of at least one prominent thoracic duct and the plexiform type was defined as the cervical part having a plexiform configuration without any prominent duct. Transvenous ductography was successful in 8 (61.5%) out of 13 patients. The success rate was 80% with the simple type and 0% with the plexiform type. In the present case, transvenous retrograde cannulation and thoracic duct embolisation were done successfully without any complication. Overall efficacy of retrograde thoracic duct embolisation is not known as there is limited literature present to date. Further studies with more patients are needed to check the efficacy of this route of thoracic duct embolisation.

Operative management

The thoracic duct can be ligated directly via video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery or open surgery. It is consistently located on the right-side of descending thoracic aorta, extending from the diaphragmatic aortic hiatus to the T8 vertebral body. In cases where the leak cannot be identified, it is ligated just proximal to the aortic hiatus, providing the highest success rate for controlling chylothorax.28 The efficacy of operative management ranges from 67% to 100% (table 1). The reported cases of thoracic duct injury and chylothorax in the last few decades are shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Reported cases of thoracic duct injury and chylothorax in literature

| S. No. | Author | Year | Number of patients | Cause of thoracic duct injury | Management | Success rate (%) |

| 1 | Orringer et al29 | 1988 | 11 | Traumatic | Thoracic duct ligation | 100 |

| 2 | Bolger et al30 | 1991 | 3 | Traumatic | Dietary restrictions, drainage and TPN | 50 |

| 3 | Bolger et al30 | 1991 | 3 | Traumatic | Thoracic duct ligation | 61 |

| 4 | Marts et al31 | 1992 | 23 | Traumatic | Dietary restrictions, drainage and TPN | 79 |

| 5 | Marts et al31 | 1992 | 6 | Traumatic | Conservative therapy failed →thoracic duct ligation | 67 |

| 6 | Cerfolio et al3 | 1996 | 47 | Traumatic | Dietary restrictions, drainage and TPN | 27.7 |

| 7 | Cerfolio et al3 | 1996 | 47 | Traumatic | Dietary restrictions, drainage and TPN/thoracic duct ligation ± pleurodesis | 91.2 |

| 8 | Dugue et al32 | 1998 | 14 | Traumatic | Dietary restrictions, drainage and TPN | 100 |

| 9 | Dugue et al32 | 1998 | 9 | Traumatic | Thoracic duct ligation | 77.8 |

| 10 | Merigliano et al33 | 1999 | 11 | Traumatic | Chylous drainage, dietary restrictions, drainage and TPN | 36.4 |

| 11 | Merigliano et al33 | 1999 | 15 | Traumatic | Thoracic duct ligation | 93.3 |

| 12 | Cope17 | 2004 | 60 | Traumatic | Lymphography/percutaneous embolisation | 65 |

| 13 | Boffa et al8 | 2008 | 21 | Traumatic/non- traumatic | Lymphography/percutaneous embolisation | 100 |

| 14 | Paul et al34 | 2009 | 22 | Traumatic | Thoracic duct ligation | 95 |

| 15 | Alejandre et al7 | 2009 | 43 | Non-traumatic | Bipedal lymphangiography/ percutaneous embolisation | 51 |

| 16 | Itkin et al5 | 2010 | 109 | Traumatic | Lymphangiography/percutaneous embolisation | 90 |

| 17 | Marcon et al18 | 2011 | 90 | Traumatic/non-traumatic | Lymphangiography/percutaneous embolisation | 69 |

| 18 | Nadolski and Itkin6 | 2012 | 6 | Traumatic/non-traumatic | Lymphangiography/percutaneous embolisation | 83.3 |

| 19 | Kumar et al35 | 2013 | 3 | Traumatic | Chylous drainage, dietary restrictions, drainage and TPN, octreotide | 100 |

| 20 | Parvinian et al36 | 2014 | 1 | Traumatic | Lymphography/percutaneous embolisation | 100 |

| 21 | Mohamed et al37 | 2017 | 1 | Traumatic | Dietary restrictions, drainage and TPN | 100 |

| 22 | Kariya et al22 | 2018 | 13 | Non-traumatic | Transvenous retrograde thoracic duct embolisation | 61.5 |

| 23 | Brown et al38 | 2018 | 1 | Traumatic | Thoracic duct ligation | 100 |

| 24 | Gahide and Sam27 | 2020 | 1 | Non-traumatic | Transvenous retrograde thoracic duct embolisation | 100 |

TPN, total parenteral nutrition.

Patient’s perspective.

I had a road traffic accident and was initially managed in another hospital and then referred as a case of chest trauma to the trauma centre with a plastic tube on the right side of my chest. Every day 1.5 to 2 litres of milky white fluid was coming through this tube. I was told that reports of my investigations were suggestive of injury to a duct inside my chest which carries this milky white fluid from my tummy and other organs to my heart. There were also fractures of three bones on the right side and three bones on the left side of my chest. There was also an injury in the organ called liver in the right upper part of my tummy. After doctors blocked the duct, fluid coming from my right side of chest decreased dramatically. There was no drainage after three days of the procedure and my tube was removed. I am very happy now and want to thank all my doctors.

Learning points.

Intranodal lymphangiography is a feasible technique to opacify the lymphatic system to perform thoracic duct embolisation.

Thoracic duct embolisation is a well tolerated and efficacious treatment for traumatic chylothorax with a better result than surgical ligation.

Transvenous retrograde cannulation is a safe and minimally invasive technique.

Footnotes

Contributors: PMUDD was involved in the treatment, data collection and in the writing of the case report. PP was involved in writing the discussion and making the tables and treatment. SK combined all the data, figures, tables and discussion to write the final article and involved in treatment. SG was involved in the treatment and critical analysis of the data as well as the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Skandalakis JE, Skandalakis LJ, Skandalakis PN. Anatomy of the lymphatics. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2007;16:1–16. 10.1016/j.soc.2006.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nair SK, Petko M, Hayward MP. Aetiology and management of chylothorax in adults. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2007;32:362–9. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cerfolio RJ, Allen MS, Deschamps C, et al. Postoperative chylothorax. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1996;112:1361–6. 10.1016/S0022-5223(96)70152-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cope C. Diagnosis and treatment of postoperative chyle leakage via percutaneous transabdominal catheterization of the cisterna chyli: a preliminary study. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1998;9:727–34. 10.1016/S1051-0443(98)70382-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Itkin M, Kucharczuk JC, Kwak A, et al. Nonoperative thoracic duct embolization for traumatic thoracic duct leak: experience in 109 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2010;139:584–90. 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.11.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nadolski GJ, Itkin M. Feasibility of ultrasound-guided intranodal lymphangiogram for thoracic duct embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2012;23:613–6. 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.01.078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alejandre-Lafont E, Krompiec C, Rau WS, et al. Effectiveness of therapeutic lymphography on lymphatic leakage. Acta Radiol 2011;52:305–11. 10.1258/ar.2010.090356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boffa DJ, Sands MJ, Rice TW, et al. A critical evaluation of a percutaneous diagnostic and treatment strategy for chylothorax after thoracic surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2008;33:435–9. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.11.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brescia MA. Chylothorax: report of case in infant. Arch. Pediat 1941;58:345. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Townshend AP, Speake W, Brooks A. Chylothorax. BMJ Case Rep 2009;2009. 10.1136/bcr.01.2009.1417. [Epub ahead of print: 12 May 2009]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dulchavsky SA, Ledgerwood AM, Lucas CE. Management of chylothorax after blunt chest trauma. J Trauma 1988;28:1400–1. 10.1097/00005373-198809000-00018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ikonomidis JS, Boulanger BR, Brenneman FD. Chylothorax after blunt chest trauma: a report of 2 cases. Can J Surg 1997;40:135. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Milano S, Maroldi R, Vezzoli G, et al. Chylothorax after blunt chest trauma: an unusual case with a long latent period. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1994;42:187–90. 10.1055/s-2007-1016485 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mikroulis D, Didilis V, Bitzikas G, et al. Octreotide in the treatment of chylothorax. Chest 2002;121:2079–80. 10.1378/chest.121.6.2079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Selle JG, Snyder WH, Schreiber JT. Chylothorax: indications for surgery. Ann Surg 1973;177:245–9. 10.1097/00000658-197302000-00022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar S, Kumar A, Pawar DK. Thoracoscopic management of thoracic duct injury: is there a place for conservatism? J Postgrad Med 2004;50:57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cope C. Management of chylothorax via percutaneous embolization. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2004;10:311–4. 10.1097/01.mcp.0000127903.45446.6d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcon F, Irani K, Aquino T, et al. Percutaneous treatment of thoracic duct injuries. Surg Endosc 2011;25:2844–8. 10.1007/s00464-011-1629-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rajebi MR, Chaudry G, Padua HM, et al. Intranodal lymphangiography: feasibility and preliminary experience in children. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2011;22:1300–5. 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laslett D, Trerotola SO, Itkin M. Delayed complications following technically successful thoracic duct embolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2012;23:76–9. 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mittleider D, Dykes TA, Cicuto KP, et al. Retrograde cannulation of the thoracic duct and embolization of the cisterna chyli in the treatment of chylous ascites. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2008;19:285–90. 10.1016/j.jvir.2007.10.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kariya S, Nakatani M, Ueno Y, et al. Transvenous retrograde thoracic ductography: initial experience with 13 consecutive cases. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2018;41:406–14. 10.1007/s00270-017-1814-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koike Y, Hirai C, Nishimura J-ichi, et al. Percutaneous transvenous embolization of the thoracic duct in the treatment of chylothorax in two patients. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2013;24:135–7. 10.1016/j.jvir.2012.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arslan B, Masrani A, Tasse JC, et al. Superselective retrograde lymphatic duct embolization for management of postoperative lymphatic leak. Diagn Interv Radiol 2017;23:379–80. 10.5152/dir.2017.16514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Inoue M, Nakatsuka S, Yashiro H, et al. Lymphatic intervention for various types of lymphorrhea: access and treatment. Radiographics 2016;36:2199–211. 10.1148/rg.2016160053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phang K, Bowman M, Phillips A, et al. Review of thoracic duct anatomical variations and clinical implications. Clin Anat 2014;27:637–44. 10.1002/ca.22337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gahide G, Sam K. Antegrade or retrograde approach for thoracic duct embolization? inhalation may be part of the answer. CVIR Endovasc 2020;3:1–2. 10.1186/s42155-020-00139-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lampson RS. Traumatic chylothorax; a review of the literature and report of a case treated by mediastinal ligation of the thoracic duct. J Thorac Surg 1948;17:778–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Orringer MB, Bluett M, Deeb GM. Aggressive treatment of chylothorax complicating transhiatal esophagectomy without thoracotomy. Surgery 1988;104:720–6. 10.1016/S0003-4975(10)61342-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bolger C, Walsh TN, Tanner WA, et al. Chylothorax after oesophagectomy. Br J Surg 2005;78:587–8. 10.1002/bjs.1800780521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marts BC, Naunheim KS, Fiore AC, et al. Conservative versus surgical management of chylothorax. Am J Surg 1992;164:532–5. 10.1016/S0002-9610(05)81195-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dugue L, Sauvanet A, Farges O, et al. Output of chyle as an indicator of treatment for chylothorax complicating oesophagectomy. Br J Surg 1998;85:1147–9. 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1998.00819.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Merigliano S, Molena D, Ruol A, et al. Chylothorax complicating esophagectomy for cancer: a plea for early thoracic duct ligation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000;119:453–7. 10.1016/S0022-5223(00)70123-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paul S, Altorki NK, Port JL, et al. Surgical management of chylothorax. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;57:226–8. 10.1055/s-0029-1185457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumar S, Mishra B, Krishna A, et al. Nonoperative management of traumatic chylothorax. Indian J Surg 2013;75:465–8. 10.1007/s12262-012-0798-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parvinian A, Mohan GC, Gaba RC, et al. Ultrasound-Guided intranodal lymphangiography followed by thoracic duct embolization for treatment of postoperative bilateral chylothorax. Head Neck 2014;36:E21–4. 10.1002/hed.23425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohamed M, Alshenawy W, Kegarise C, et al. Bilateral chylothorax due to blunt trauma without radiographic evidence of traumatic injury. Clin Pract Cases Emerg Med 2017;1:111–4. 10.5811/cpcem.2016.12.32937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown SR, Fernandez C, Bertellotti R, et al. Blunt rupture of the thoracic duct after severe thoracic trauma. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2018;3:e000183. 10.1136/tsaco-2018-000183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]