Abstract

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 is one of the major drug-metabolizing enzymes. Genetic variants of CYP3A4 with altered activity are one of the factors responsible for interindividual differences in drug metabolism. Azole antifungals competitively inhibit CYP3A4 to cause clinically significant drug-drug interactions. In the present quantitative study, we investigated the inhibitory effects of three azole antifungals (ketoconazole, voriconazole, and fluconazole) on testosterone metabolism by recombinant CYP3A4 genetic variants (CYP3A4.1 (WT), CYP3A4.2, CYP3A4.7, CYP3A4.16, and CYP3A4.18) and compared them with those previously reported for itraconazole. The inhibition constants (Ki) of ketoconazole, voriconazole, and fluconazole for rCYP3A4.1 were 3.6 nM, 3.2 μM, and 18.3 μM, respectively. The Ki values of these azoles for rCYP3A4.16 were 13.9-, 13.6-, and 6.1-fold higher than those for rCYP3A4.1, respectively, whereas the Ki value of itraconazole for rCYP3A4.16 was 0.54-fold of that for rCYP3A4.1. The other genetic variants had similar effects on the Ki values of the three azoles, whereas a very different pattern was seen for itraconazole. In conclusion, itraconazole has unique characteristics that are distinct from those shared by the other azole anti-fungal drugs ketoconazole, voriconazole, and fluconazole with regard to the influence of genetic variations on the inhibition of CYP3A4.

Keywords: CYP3A4, azole antifungals, competitive inhibition, drug-drug interactions, genetic variants

Introduction

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 is a clinically significant oxidative enzyme that is involved in the metabolism of >50% of drugs used in the clinical setting, as well as certain endogenous substances (e.g., steroids) [1]. More than thirty non-synonymous genetic variants of CYP3A4 have been identified to date [2]. In vitro and in vivo studies have shown that the metabolic activity of these genetic variants differs, and such variation is one of the factors responsible for interindividual variability in CYP3A4-mediated drug metabolism [3, 4].

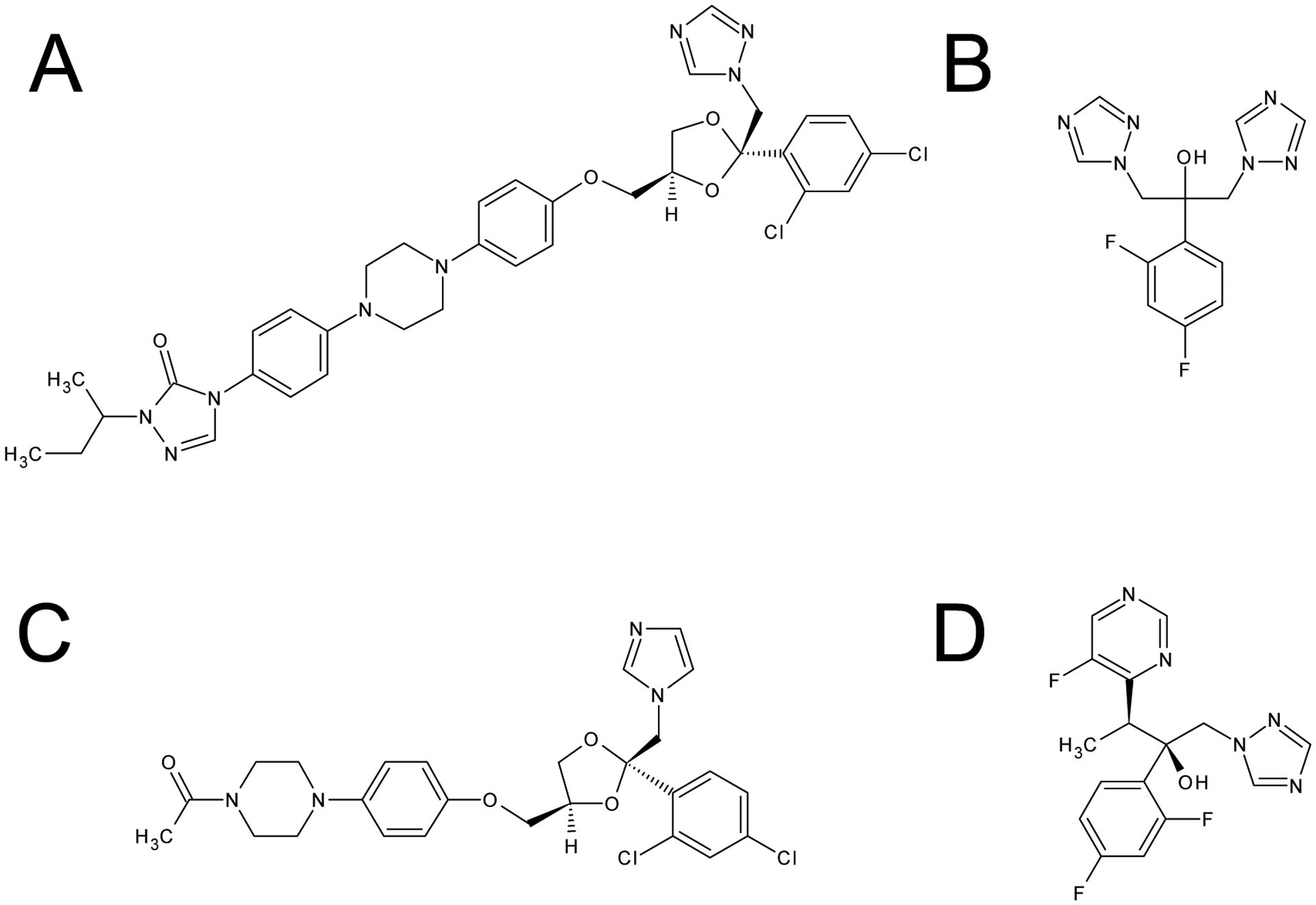

On the other hand, the inhibition of CYP3A4 is one of the major causes of drug-drug interactions (DDI). For example, a variety of important azole antifungals are known to be potent competitive inhibitors of CYP3A4 [5]. Using recombinant human CYP3A4 variants (rCYP3A4.1 (WT), rCYP3A4.2, rCYP3A4.7, rCYP3A4.16, and rCYP3A4.18) expressed in Escherichia coli, we previously found that the inhibitory kinetics of two typical CYP3A4 inhibitors, itraconazole (ITCZ, Figure 1A) and cimetidine, were affected differently by genetic variations in CYP3A4 [6]. ITCZ exhibited lower and higher inhibitory potency against CYP3A4.7 and CYP3A4.16, respectively, compared with its potency against CYP3A4.1, while cimetidine displayed the opposite trend. An in silico docking simulation demonstrated that these differences in the effects of genetic variations could be explained based on the ability of the two inhibitors to access the active site of each CYP3A4 variant, which was affected by conformational changes caused by amino acid substitution(s).

Figure 1.

Structural formulae of azole antifungals

A: itraconazole (ITCZ), B: fluconazole (FCZ), C: ketoconazole (KCZ), D: voriconazole (VCZ)

Among azole antifungals, the order of inhibitory potency towards CYP3A4.1 follows the pattern ketoconazole (KCZ, Figure 1C) > ITCZ > voriconazole (VCZ, Figure 1D) > fluconazole (FCZ, Figure 1B) [5]. However, it remains to be investigated whether this is also the case for other CYP3A4 variants. Although azole nitrogen atoms are considered to play an important role in the interactions between antifungals and the catalytic site of CYP3A4 [7], the roles the non-azole parts of these inhibitors play in such interactions remain unclear.

The aim of this study was to quantitatively evaluate the inhibitory properties of three azole antifungals, KCZ, VCZ, and FCZ, on testosterone (TST) metabolism by CYP3A4 variants (rCYP3A4.1, rCYP3A4.2, rCYP3A4.7, rCYP3A4.16, and rCYP3A4.18) and compare them with those of ITCZ, which were reported previously.

Materials and Methods

Chemicals and materials

TST, FCZ, and KCZ were purchased from Nacalai Tesque Inc. (Kyoto, Japan), Wako Pure Chemical Industries Ltd (Osaka, Japan), and Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO), respectively. VFEND (200 mg, a VCZ injection solution) was purchased from Pfizer (New York, NY, USA). Hydrocortisone and 6β-hydroxytestosterone (6β-OH TST) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and SPI-Bio Bertin Pharma (Bretonneux, France), respectively. The E. coli membrane fractions of CYP3A4.1, CYP3A4.2, CYP3A4.7, CYP3A4.16, and CYP3A4.18 were prepared as described previously [8]. All other reagents were of reagent or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade and were obtained commercially.

Study of the inhibitory effects of azole antifungals on CYP3A4 variants

The CYP3A4 membrane fraction (0.0125 nmol P450/mL) was preincubated at 37 °C for 10 min in 300 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) containing TST (final concentration: 10–500 μM) as a substrate, EDTA (0.1 mM), and either FCZ (10–500 μM), KCZ (3–300 nM), or VCZ (3–300 μM) as a competitive inhibitor. The reaction was initiated by adding an NADPH-generating system (0.2 mM NADPH, 5 mM glucose-6-phosphate, 0.5 mM NADP+, 1 unit/mL glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, and 3 mM MgCl2). The final volume of the reaction mixture was 500 μL. After incubation for 20 min, the reaction was terminated by adding 500 μL ice-cold methanol containing 18.4 μM hydrocortisone as an internal standard. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was centrifuged at 4 °C, and the concentration of 6β-OH TST in the supernatant was determined using the HPLC-UV method described below. TST was dissolved in the buffer using both ethanol and methanol. FCZ and KCZ were dissolved in the buffer using ethanol and methanol, respectively. The final concentrations of ethanol and methanol in the reaction buffer did not exceed 1% and 2.5%, respectively.

Determination of the 6β-OH TST concentration using the HPLC-UV method

The HPLC-UV system consisted of a pump (LC-20AD), UV detector (SPD-20A) (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan), and octadecylsilane reversed-phase column (Cosmosil, 5C18-AR-II or 5C18-MS-II, 4.6 mm ×150 mm, Nacalai Tesque). The column temperature was set at 45 °C. The mobile phase was composed of 43% or 45% (v/v) methanol, at a flow rate of 2.0 mL/min. The detection wavelength was set at 254 nm. The concentration of 6β-OH TST was determined from the area of the relevant peak using hydrocortisone as an internal standard.

Calculation of kinetic parameters

Equation 1 was fitt to sets of metabolic rates at all inhibitor concentrations and various substrate concentrations using a non-linear least-squares method and the MLAB software (Civilized Software Inc., Bethesda, MD, USA) to calculate the following kinetic parameters: the logarithm of the Michaelis constant (ln Km), the maximum reaction rate (Vmax, i.e. kcat), and the logarithm of the inhibitory constant (ln Ki).

| equation 1 |

Statistical analysis

The order (from largest to smallest) of the Ki values for the five examined variants was compared among the inhibitors, and a Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was calculated. Furthermore, the correlation between the order of the inhibitor Ki values and that of Km values of the five variants for TST metabolism was assessed in the same manner. The significance of differences between the Ki and Km values for the CYP3A4 variants was determined by analysis of variance, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, using SPSS software (version 25; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Comparison of metabolic kinetics among CYP3A4 variants

The kinetic parameters of the CYP3A4 variants are shown in Table 1. The Vmax (i.e. kcat)values of CYP3A4.16 and CYP3A4.18 were significantly lower and higher than that of the WT, respectively. The Km values of all variants were higher than that of the WT. In particular, the Km value of CYP3A4.16 was almost 7-fold higher than that of the WT. The “intrinsic clearance” (Vmax/Km, i.e. specificity constant) values of CYP3A4.7 and CYP3A4.16 were significantly lower than that of the WT enzyme.

Table 1.

Kinetic parameters of TST metabolism by CYP3A4 variants

| Variants | Vmax | Km | Vmax/Km | Ratio of Vmax/Km to WT |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nmol/min/nmol P450 | μM | |||

| CYP3A4.1 | 9.67 (6.37–13.0) | 37.8 (30.2–47.4) | 0.275 (0.137–0.413) | (1) |

| CYP3A4.2 | 10.3 (8.46–12.1) | 51.9* (41.2–65.2) | 0.202 (0.151–0.252) | 0.73 |

| CYP3A4.7 | 8.29 (5.35–11.2) | 82.1* (65.5–103) | 0.107* (0.0554–0.159) | 0.39 |

| CYP3A4.16 | 4.38* (1.60–7.16) | 260* (168–402) | 0.0153* (0.00569–0.0250) | 0.056 |

| CYP3A4.18 | 13.2* (8.81–17.6) | 43.3 (32.9–57.0) | 0.323 (0.173–0.473) | 1.17 |

n=14; Vmax, Vmax/Km : arithmetic mean (−1 SD ~+1 SD), Km : geometric mean (−1 SD ~ +1 SD)

p<0.05 vs. CYP3A4.1

Comparison of the inhibitory potency of azole antifungals among CYP3A4 variants

All of the tested inhibitors (FCZ, KCZ, and VCZ) inhibited CYP3A4 activity in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 2). The Ki values of FCZ for CYP3A4.7, CYP3A4.16, and CYP3A4.18 were significantly higher than that for the WT (i.e., FCZ exhibited weaker inhibitory potency against the variants; Table 2). In particular, the Ki value for CYP3A4.16 was >6-fold higher than that for the WT enzyme. With regard to KCZ, its Ki values for CYP3A4.2, CYP3A4.7, and CYP3A4.18 were comparable to that for the WT enzyme, while its Ki value for CYP3A4.16 was significantly higher (14-fold) than that for the WT. Similarly, the Ki values of VCZ for all variants were higher than that for the WT, and its Ki value for CYP3A4.16 was markedly increased (also 14-fold higher than that for the WT; Table 2).

Figure 2.

The effects of azole antifungals on TST metabolism by CYP3A4.1 (A: FCZ, B: KCZ, C: VCZ)

The concentration of TST was set at 10–500 μM. Data are shown as the mean ± S.D. (n=5)

Table 2.

Inhibitory kinetic parameters of azole antifungals for CYP3A4 variants

| Variants | Ki | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FCZ (μM) | Ratio | KCZ (nM) | Ratio | VCZ (μM) | Ratio | ITCZ (nM)† | Ratio | |

| CYP3A4.1 | 18.3 (16.5–20.2) | (1) | 3.60 (2.89–4.47) | (1) | 3.24 (2.75–3.82) | (1) | 76 (45.1–129) | (1) |

| CYP3A4.2 | 24.7 (17.3–35.3) | 1.35 | 4.07 (2.94–5.64) | 1.13 | 5.95* (5.19–6.83) | 1.84 | 45 (30.7–65.7) | 0.59 |

| CYP3A4.7 | 56.7* (52.2–61.5) | 3.10 | 4.13 (3.11–5.48) | 1.15 | 9.08* (8.44–9.78) | 2.80 | 180* (146–219) | 2.37 |

| CYP3A4.16 | 112* (97.0–131) | 6.12 | 49.8* (26.2–94.7) | 13.9 | 44.1* (29.7–65.4) | 13.6 | 41 (17.1–99.8) | 0.54 |

| CYP3A4.18 | 28.5* (26.9–30.3) | 1.56 | 4.50 (3.73–5.43) | 1.25 | 4.86 (3.83–6.16) | 1.50 | 82 (54.1–133) | 1.08 |

Correlations between the order of inhibitory potency (Ki values) between azole antifungals

The order of Ki values among CYP3A4 variants was compared between pairs of inhibitors, and a correlation coefficient was calculated for each pair (Table 3). In the comparison between VCZ and FCZ, it was found that the two inhibitors exhibited similar Ki value orders, resulting in a correlation coefficient (rs) of 0.9. Good correlations in the Ki value order were also observed between KCZ and VCZ and between KCZ and FCZ (rs 0.7 and 0.9, respectively). However, the Ki value order of ITCZ did not display good correlations with those of the other three azoles (rs −0.3 to −0.1). In the comparison of the order of the Km values for TST among the variants, good correlations with the order of Ki values were observed for both FCZ and VCZ (rs 0.98 and 1.0, respectively). However, ITCZ did not exhibit any such correlation (rs 0.09).

Table 3.

Spearman’s correlation coefficients for the order of Ki or Km values among the five variants

| Inhibitors (order of Ki values) | Substrate (order of Km values) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inhibitors | FCZ | KCZ | VCZ | ITCZ | TST |

| FCZ | 0.9 | 0.9 | −0.1 | 0.98 | |

| KCZ | 0.7 | −0.2 | 0.49 | ||

| VCZ | −0.3 | 1.0 | |||

| ITCZ | 0.09 | ||||

Discussion

In order to assess the risk of an individual to drug interactions with azole antifungals involving CYP3A4 inhibition, which can lead to severe clinical outcomes [9–12], it is crucial to quantitatively investigate the inhibitory kinetics of such interactions for both the WT enzyme and the variants. The present study provides clinically useful information about the inhibitory potency of azole antifungals against major CYP3A4 genetic variants.

The order of inhibitory potency against CYP3A4.1 was in the order KCZ > VCZ > FCZ (Table 2). KCZ exhibited almost 1,000-fold more potent inhibition than the other three inhibitors. These findings are consistent with the findings of a previous study by Zhang [5], which showed that the order of inhibitory potency was KCZ > ITCZ > VCZ > FCZ. It has been reported that two molecules of KCZ bind to the catalytic site in parallel, but opposite directions [13]. In addition, it has been reported that the hydrogen bonds between the two molecules of KCZ and Ser119 and Arg372, which are close to a heme moiety, and the π-π interaction between the chlorobenzyl ring of KCZ and Phe304 contribute to stabilizing the CYP3A4-KCZ complex [13]. These three amino acid residues are conserved in all of the CYP3A4 variants investigated in this study. Therefore, our finding that KCZ displayed more potent inhibition than other azole antifungals that lack a chlorobenzyl ring, regardless of genetic mutations in CYP3A4, are quite plausible.

The order of the Ki values for the CYP3A4 variants was similar for all three azole antifungals, with rs values of 0.7–0.9 seen for each pair of azole antifungals (Table 3). As the nitrogen atom of the azole moiety binds to the heme molecule of CYP3A4 and the structures located near the azole are similar in all three antifungals, it is reasonable to conclude that their Ki values were influenced similarly by non-synonymous mutations.

In a comparison of the effects of genetic variations in CYP3A4 on the order of inhibitory potency between ITCZ (based on our previous findings) and FCZ, VCZ, and KCZ, a different pattern for ITCZ was seen than for the other three inhibitors. One possible explanation for these differences is that ITCZ is structurally bulkier than the others so it may access the heme iron in a different way from the other inhibitors (Figure 1A). This indicates that the inhibitory potency of inhibitors, even within the same structural group, can be affected differently by genetic polymorphisms in enzymes. Therefore, the inhibitory potency of an inhibitor against a certain variant of an enzyme cannot be estimated accurately based on its inhibitory potency against the WT form, even if data for structurally similar inhibitors are available. In order to quantitatively estimate the extent of DDI for each individual, the inhibitory potency of each inhibitor against the variant of the target enzyme that the subject bears should be determined experimentally.

The effects of genetic variations in CYP3A4 on the order of Km values for TST metabolism also exhibited a good correlation with the order of Ki values for FCZ and VCZ (rs 0.98 and 1.0, respectively), but this was not the case for ITCZ (rs 0.09). Regarding the interaction with the CYP3A4 molecule, TST might share more binding site(s) or moieties with FCZ and VCZ than with ITCZ.

In the present study, although we compared inhibitory potency among CYP3A4 variants using the Ki values obtained from the inhibition study, we do not know the structural basis of our findings. The crystal structures of CYP3A4 variants have not been determined, so the nature of the binding of substrates/inhibitors to CYP3A4 remains unknown. The results of the current study may be explained or accurately predicted by further investigations involving in silico docking simulations and/or actual X-ray crystal structure analysis.

Conclusion

In this study, KCZ, VCZ, and FCZ inhibited the enzymatic activity of five CYP3A4 variants with different potencies. The order of inhibitory potency against the CYP3A4 variants was similar among these three azoles but different from that of ITCZ. As genetic variations affect the inhibitory kinetics of inhibitors differently, even within the same structural group, inhibitory kinetics should be determined experimentally, at least for major variants, in order to enable the personalized prediction of the extent of DDI.

Acknowledgements:

This study was supported in part by JSPS Kakenhi Grant Numbers 15K08596 and 18K06758 [to H.O.] and United States National Institutes of Health grant R01 GM118122 [to F.P.G.].

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

None

References

- [1].Murayama N, Nakamura T, Saeki M, Soyama A, Saito Y, Sai K, Ishida S, Nakajima O, Itoda M, Ohno Y, Ozawa S, Sawada J. CYP3A4 Gene polymorphisms influence testosterone 6β-hydroxylation. Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetics, 2002; 17(2); 150–156. 10.2133/dmpk.17.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.The Human Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Allele Nomenclature Committee Web Site (PharmVar, Pharmacogene Variation Consortium), https://www.pharmvar.org/gene/CYP3A4 [accessed 19 April 2020]

- [3].Miyazaki M, Nakamura K, Fujita Y, Guengerich FP, Horiuchi R, Yamamoto K. Defective activity of recombinant cytochromes P450 3A4.2 and 3A4.16 in oxidation of midazolam, nifedipine, and testosterone. Drug Metab Dispos, 2008; 36; 2287–2291. 10.1124/dmd.108.021816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hu YF, Tu JH, Tan ZR, Liu ZQ, Zhou G, He J, Wang D, Zhou HH. Association of CYP3A4*18B polymorphisms with the pharmacokinetics of cyclosporine in healthy subjects. Xenobiotica, 2007; 37(3); 315–327. 10.1080/00498250601149206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Zhang S, Pillai VC, Mada SR, Strom S, Venkataramanan R. Effect of voriconazole and other azole antifungal agents on CYP3A activity and metabolism of tacrolimus in human liver microsomes. Xenobiotica, 2012; 42(5); 409–416. 10.3109/00498254.2011.631224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Akiyoshi T, Saito T, Murase S, Miyazaki M, Murayama N, Yamazaki H, Guengerich FP, Nakamura K, Yamamoto K, Ohtani H. Comparison of the inhibitory profiles of itraconazole and cimetidine in cytochrome P450 3A4 genetic variants. Drug Metab Dispos, 2011; 39(4); 724–728. 10.1124/dmd.110.036780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Vanden Bossche H, Marichal P, Gorrens J, Coene MC, Willemsens G, Bellens D, Roels I, Moereels H, Janssen PA. Biochemical approaches to selective antifungal activity. Focus on azole antifungals. Mycoses, 1989; 32(1); 35–52. 10.1111/j.1439-0507.1989.tb02293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Gillam EM, Baba T, Kim BR, Ohmori S, Guengerich FP. Expression of modified human Cytochrome P450 3A4 in Escherichia coli and purification and reconstitution of the enzyme. Arch. Biochem. Biophys, 1993; 305; 123–131. 10.1006/abbi.1993.1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Monahan BP, Ferguson CL, Killeavy ES, Lloyd BK, Troy J, Cantilena LR Jr. Torsades de pointes occurring in association with terfenadine use. J. Am. Med. Assoc, 1990; 264(21); 2788–2790. 10.1001/jama.1990.03450210088038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mueck W, Kubitza D, Becka M. Co-administration of rivaroxaban with drugs that share its elimination pathways: pharmacokinetic effects in healthy subjects. Br. J. Clin. Pharmaco.l, 2013; 76(3); 455–466. 10.1111/bcp.12075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lees RS, Lees AM. Rhabdomyolysis from the coadministration of lovastatin and the antifungal agent itraconazole. N. Eng. J. Med, 1995; 333; 664–665. 10.1056/NEJM199509073331015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Varhe A, Olkkola KT, Neuvonen PJ. Effect of fluconazole dose on the extent of fluconazole-triazolam interaction. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol, 1996; 42(4); 465–470. 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1996.tb00009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ekroos M, and Sjögren T (2006) Structural basis for ligand promiscuity in cytochrome P450 3A4. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103, 13682–13687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Sevrioukova IF, Poulos TL. Understanding the mechanism of cytochrome P450 3A4: Recent advances and remaining problems. Dalton Transactions, 2013; 42(9); 3116–3126. 10.1039/C2DT31833D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]