Introduction

Autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) is not a common disease but with increasing incidence in Asia–Pacific area. Although the etiology and pathogenesis are not completely clear, the disease is the result of loss of autoimmune tolerance in genetically predisposed individuals. AIH is characterized by autoantibodies, hypergammaglobulinemia, and interface hepatitis. Corticosteroids and azathioprine are standard regimens for AIH, which should be started after diagnosis. Alternative therapy should be considered for those who do not respond to standard regimens. End-stage AIH patient could be saved by liver transplantation.

A panel of clinicians discussed the epidemiology, pathology, diverse clinical characteristics and therapy of patients with AIH in the Asia–Pacific region and wrote the draft of this guidance. Particular attention is paid to those characteristics that are different from those of Western patients. Internal discussion and external review were performed before finalizing this guidance.

Epidemiology

AIH is a rare disease with unknown etiology and may affect all ages, genders and ethnic groups worldwide. However, this disease presents with a strong female predominance and geographic variation [1]. As summarized in a recent meta-analysis, the AIH has a global annual incidence of 1.37 per 100,000 (1.11 for female and 0.22 for male) and prevalence 17.44 per 100,000 (12.77 for female and 2.91 for male) [2]. The pooled annual incidence rate in Asian (1.31/100,000) is similar to that in European (1.37/100,000) and American population (1.00/100,000); however, the pooled prevalence rate in Asian (12.99/100,000) is lower than that in European (19.44/100,000) and American population (22.80/100,000) [2]. One possible explanation for this incidence–prevalence discrepancy would be the late onset or diagnosis and shorter survival of the AIH in Asian population [3, 4].

The exceptional case in Asia is Japan, where the point prevalence of AIH in Japan was reported to be 23.90/100,000, comparable to those in Europe and America [5], while a recent study in Japan suggests a peak age of AIH patients in Japan is 60–70 years [5]. Indeed, even within Asia, the reported prevalence of AIH varies greatly. In Korean, a population-based study using the database of the National Health Insurance (which covers 95% of the South Korean population) demonstrates a low average annual incidence and prevalence rate with 1.07 and 4.82 per 100,000 people, respectively [6].

Disparities in prevalence of AIH in different geographical regions may have several explanations. First, genetic factors may play an important role and this can partly explain the higher prevalence rate of AIH in New Zealand than other Asia–Pacific countries, as 83% of the population is of European descent [7]. Second, environmental factors may also play a role in the development of AIH, as supported by a recent study showing biological use was associated with increased incidence of AIH in Iceland [8]. Third, health care system difference and relatively low awareness/recognition of AIH in Asia [4]. Fourth, the methodological differences in term of study design, population selection and database utility, case definition, case finding and ascertainment [2].

Pathogenesis

AIH is caused by a lack of autoimmune tolerance, and the etiology and pathogenesis are not completely clear. With the deepening of AIH-related mechanism research, the pathogenesis of this disease has made some progress. AIH is the result of interactions between genetic susceptibility, predisposing factors, molecular mimicry, autoantigen response, and immunomodulatory defects.

Genetic susceptibility

The etiology of AIH remains elusive, however, both genetic and environmental factors are thought to play a crucial role in the development of the disease. Although there have been no family studies in AIH, many case reports revealed that AIH occurred simultaneously in two or three family members [9]. Epidemiological studies also found a family history of autoimmunity in about 40% of AIH patients, as well as the significantly increased percentage of AIH patients concurrent with extrahepatic autoimmune disorders. These data indicated an important role for a genetic component in the development of AIH [10]. Till now, genetic studies have identified multiple loci influencing the susceptibility to AIH in human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and non-HLA regions. Despite the ethnic differences, HLA-DR3 or -DR4, is the most convincing genetic risk loci for AIH (Table 1) [11, 12]. HLA-DRB1*04:04 and DRB1*04:05 were considered to increase the susceptibility of AIH in the Mexican, Korean, and Japanese populations, while HLA-DRB1*03:01 and DRB1*04:01 have been described as the most significant disease susceptible loci that related to the prognosis of AIH among European and American populations [13]. In contrast, some alleles like DRB1*1501 and DRB1*1302 were demonstrated as protective factors in AIH [14, 15]. HLA B27 and Cw4 had significant association with AIH-1 in Western Indian population [16], while HLA-DRB1*14 indicated high risk of AIH-2 in North India [17]. In addition, more and more non-HLA genes were reported to participate in AIH, such as tumor necrosis factor-receptor superfamily member 6 (TNFRSF6), protein tyrosine phosphatase N22 (PTPN22), vitamin D receptor (VDR) and so on [18–20]. The only genome-wide association study of AIH to date was performed in Caucasians, which suggested association between AIH and variants mapping to Scr homology 2 adaptor protein 3 (SH2B3) and caspase recruitment domain family member 10 (CARD10) gene [21]. In addition, candidate gene association studies have been conducted in AIH, but the results were not consistent across different populations [13, 21, 22].

Table 1.

HLA alleles associated with AIH

| Year | Author | Populations | Type of AIH | Risk loci | Protective loci |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | Seki et al. [23] | Japanese | – | DRB1*04:05 | – |

| 1997 | Strettell et al. [24] | White and of northern European | 1 | DRB1*03:01, DRB1*04:01 | DRB5*01:01, DRB1*15:01 |

| 1997 | Czaja et al. [25] | – | 1 | DRB1*03:01, DRB1*04:01 | – |

| 1998 | Vazquez-Garcia et al. [26] | Mexican (Mestizo) | 1 | DRB1*04:04 | – |

| 1999 | Bittencourt [27] | White, black and Amerindian ancestry | 1 and 2 | DRB1*03, DRB1*13, DRB1*07 | DRB1*03:01 |

| 2003 | Amarapurkar [16] | Western Indian | 1 | B27, Cw4 | – |

| 2005 | Muratori et al. [28] | Italian and Caucasian | 1 and 2 | B8-DR3-DQ2 | – |

| 2006 | Teufel et al. [29] | German | 1 | B8-DR3-DQ2 | – |

| 2006 | Al-Chalabi et al. [30] | British | 1 | B8-DR3/DR4 | – |

| 2006 | Djilali-Saiah et al. [31] | Caucasian | 2 | DQB1 *02:01, | – |

| 2007 | Mdel et al. [32] | Mestizo | 1 | DRB1*03:01, DRB1*13:01 | DQB1*04 |

| 2008 | Lim et al. [33] | Korean | 1 | DRB1*04:05, DQB1*04:01 | |

| 2014 | de Boer et al. [21] | Netherlander, German, and Switzer | 1 | DRB1*03:01, DRB1*04:01 | – |

| 2014 | Umemura et al. [14] | Japanese | 1 | DRB1*04:05, DQB1*04:01 | DRB1*15:01, DQB2*06:02 |

| 2014 | Kaur [17] | North Indian | 2 | DRB1*14 | – |

| 2017 | Oka et al. [15] | Japanese | 1 | DRB1*04:01, DRB1*04:05, DQB1*04:01 | DRB1*13:02 |

AIH is classified into two types (AIH-1 and AIH-2) according to different autoantibodies, which are described in detail in “Laboratory findings”

Potential predisposing factors and destruction of autoimmune tolerance

Environmental factors have also been linked to the pathogenesis of AIH. Exposure to drugs like minocycline and nitrofurantoin, low vitamin D levels and pathogens were known risk factors for AIH [34–37]. Molecular mimicry hypothesis was developed to explain the production of autoantibodies in autoimmune disorders. Exogenous pathogens, such as bacteria or virus, may trigger the production of antibodies and activate immune response [38]. The main target cell of the disease process is the hepatocyte. Certain drugs, including nitrofurantoin, minocycline, oxyphenisatin, methyldopa, diclofenac, interferon α, pemoline, atorvastatin, infliximab and herbal agents, can induce hepatocellular injury that imitate AIH [39]. The frequency of drug-induced AIH among patients with classical AIH is 9%, and most cases present acute onset [40]. Classical AIH is typically continuous after the incriminated agent removal [41], which implies the triggering antigen is constantly renewed or immune regulatory mechanism is permanently impaired [41]. In particular, re-exposure to the offending agent should be avoided indefinitely after recovery. More recently, intestinal microbiota has been suggested to be involved in all types of AIH [42]. For example, alterations in intestinal microbiota were found in AIH, and translocation of a gut microbe to the liver promoted autoimmunity in patients [43, 44]. The enrichment of Veillonella dispar in the steroid-naïve AIH microbiome was correlated with disease severity. Intestinal microbiota may be a useful non-invasive biomarker in all types of autoimmune hepatitis [45].

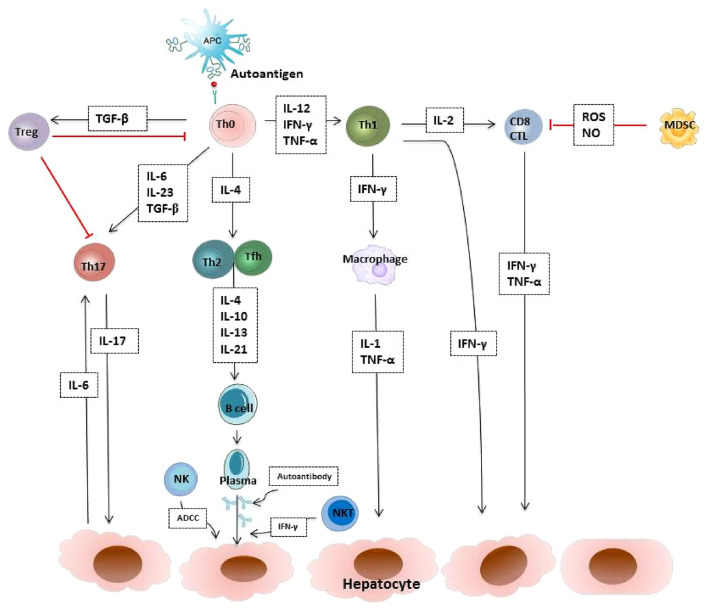

The hypotheses on the pathogenesis of AIH are components of the humoral and cellular immune system. There is a complex nature of immune cells, signaling pathways and their interactions in AIH, including regulatory T cells (Treg cells) loss of self-tolerance, accelerated effector T cells activation, increased autoreactive B cells production and natural killer (NK) cells activity (Fig. 1). Autoantibodies may be useful in identifying targets of disease processes ultimately mediated by T cells. Numerical and functional Treg defects were observed in AIH patients [46–49]. The transfusion of ex vivo expanded Treg cells might be a potential curative approach for AIH. The serum levels of IL-17 and IL-23, as well as the frequency of IL-17+ cells in the liver, were significantly elevated in patients with AIH and associated with increased inflammation and fibrosis. Th17 cells are key effector T cells that regulate the pathogenesis of AIH, via induction of MAPK dependent hepatic IL-6 expression. Blocking the signaling pathway and interrupting the positive feedback loop are potential therapeutic targets for AIH [50]. Recently, myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), a heterogeneous immature myeloid cell population with remarkable immune suppressor function as an important negative feedback mechanism in immune-mediated liver injury. MDSCs have a remarkable ability to suppress T cell responses and regulate innate immunity by modulating cytokine production and interacting with natural killer cells. In autoimmune liver disease, Farnesoid-X-receptor (FXR) activation expanded monocytic MDSCs in liver. FXR activation upregulate the expression of PIR-B by binding PIR-B promoter to enhance the suppressor function of MDSCs [51]. Maintaining the balance between Treg cells, Th17 cells, MDSCs and NKT cells has become the promising strategy of future immune therapy.

Fig.1.

AIH causes a cycle of immune injury to hepatocytes. The immune imbalance between effector T cells, regulatory T cells, B cells, NK cells and MDSCs is a critical reason for autoimmune-mediated liver damage. APC antigen presenting cell, Th T helper cell, CTL cytotoxic T cell, Treg regulatory T cells, Tfh T follicular helper cell, MDSC myeloid-derived suppressor cell, NK cell natural killer cell, ADCC antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity, TGF-β transforming growth factor-β, IFN-γ interferon-γ, TNF-α tumour necrosis factor-α, IL interleukin

Clinical spectrum

AIH has changeable clinical phenotypes and different presentations [11]. The spectrum of initial manifestations ranges from asymptomatic to acute hepatic failure, but the major manifestation is chronic hepatitis [52, 53]. The clinical manifestations of AIH are non-specific [54], around 25% AIH patients are asymptomatic. Asymptomatic patients are generally discovered because of abnormal liver function tests in physical exam. The most common symptoms are sleepiness, fatigue, and general malaise. Hepatomegaly, splenomegaly, ascites and occasional peripheral edema can be observed during physical examination. Because of the insidious onset, nearly 30% of AIH patients demonstrated histological cirrhosis at accession [4, 55]. In some cases, decompensated manifestations could be the initial presentations. The characteristic biochemical features of AIH are the elevated AST and ALT levels, indicating hepatocellular injury. About 10–20% of the patients are asymptomatic and only have elevated serum aminotransferase levels during the physical examination. The risk of progression to cirrhosis in these patients is similar to that in the symptomatic patients. The first onset of AIH can occur in pregnant female or after their childbirth. Therefore, early diagnosis and timely treatment are vital for the safety of both mothers and infants [56].

AIH is usually complicated with autoimmune diseases including Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (10–23%), diabetes mellitus (7–9%), inflammatory bowel disease (2–8%), rheumatoid arthritis (2–5%), Sjögren’s syndrome (1–4%), celiac disease (%3.5) psoriasis (3%) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) (1–2%), and so on [57]. AIH and other autoimmune diseases such as SLE are all independent disease types. Simultaneously present autoimmune diseases shall be treated according to the major disease type, and the dosage of glucocorticoids should be exactly sufficient to control disease activities.

Acute and acute severe AIH

AIH generally has a chronic presentation with serum ALT and/or AST abnormalities, whereas it can also present as an acute/acute severe disease [58]. The clinical features of acute AIH from the Japanese population mainly include elevated ALT and a higher proportion of liver fibrosis [59]. A Japanese nationwide survey found about 10% of AIH cases showed acute hepatitis in histological examinations [60]. Zone 3 necrosis is a histological feature of acute AIH [61]. Recently, the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL) acute on chronic liver failure (ACLF) working party has reported that AIH flare as a cause of ACLF is not uncommon in Asian patients (82/2825 ACLF patients, 2.9%) [62]. When AIH presents acute/acute severe onset, patients may not have high immunoglobulin G (IgG) concentrations and serum autoantibodies to fulfill the IAIHG diagnosis criteria, especially using the simplified criteria [61, 63, 64]. Furthermore, histological features may also be atypical, these AIH patients are likely to be misdiagnosed as cryptogenic hepatitis. Patients with advanced encephalopathy should be considered for liver transplantation promptly [65].

AIH patients with cirrhosis or at liver decompensated stage

About 1/4 of AIH patients are cirrhotic at presentation [4, 66]. Miyake et al. established a model for determining cirrhosis in type I AIH patients. The risk score (≥ 0.20) was estimated to be cirrhotic and the specificity and sensitivity was 83 and 90%, respectively [67]. From 1975 to 2010, Abe et al. found 20.4% of patients with type I AIH (n = 250) were cirrhotic in Japanese population. During the follow-up period, the relapse rate was high in patients who developed cirrhosis [68].

Hepatocellular carcinoma development in AIH does exist and is associated with cirrhosis, although it is less common than other causes of liver diseases [69]. For the cirrhosis subgroup, routine imaging examinations like ultrasound should be done at 6-month intervals to exclude hepatocellular cancer (HCC) [70].

Recommendation

The major manifestation of AIH is chronic hepatitis. It can also present as acute attacks or even acute liver failure. Therefore, AIH should be considered for patients with abnormal liver function of unknown causes.

Pathology

Liver histological examination is essential for the diagnosis and management of AIH. Liver biopsy is prerequisite for the accurate diagnosis of AIH [71–73]. It is also helpful to identify overlap syndromes [overlap of AIH with other diseases, such as primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)], highlight the posible concomitant disease, and exclude other potential cause of liver diseases, such as drug-induced liver injury (DILI). Besides diagnosis, biopsy examination is used to assess fibrosis stage and grade disease severity in AIH. The four-tier grading systems developed for chronic viral hepatitis histological grading and staging systems, such as Metavir [74], can also be used to assess the grading of inflammatory activity and staging of fibrosis in AIH. These factors provide important information on prognosis and may serve to guide treatment decision [75–81]. Furthermore, histological evaluation helps to determine the completeness of the treatment response and appropriate timing for drug withdrawal, because the degrees of necroinflammatory activity and severity of AIH do not often correlate well with transaminase levels [79]. Liver biopsy at diagnosis, therefore, is recommended in all patients with suspected AIH unless there are significant contraindications, and it should be performed prior to stating treatment [12, 39, 66, 72, 73, 79, 82]. The transjugular approach can be used in cases with severe coagulopathy, particularly, in those with acute/fulminant onset of the disease [83–88]. Alternatively, biopsy under mini-laparoscopy can be used and has also been shown to be safe even in cases of advanced coagulopathy [89–91].

In certain circumstance, such as patients with contraindications of liver biopsy, or no transjugular liver biopsy being carried out, non-invasive methods to evaluate stage may be candidates. Growing interest for non-invasive methods for the assessment of fibrosis and inflammation in AIH [92–98]. But at present, non-invasive methods cannot substitute the need of a biopsy, particularly at diagnosis.

Classical histologic features

Interface hepatitis (hepatitis at the junction of the portal tract and hepatic parenchyma, formerly called piecemeal necrosis) with dense lymphocytic or lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates, hepatocellular rosette formation, emperipolesis are representative findings of AIH [71–73, 99, 100]. Plasma cells are typical for AIH and usually found abundant at the interface and throughout the lobule [101–105], but their paucity in the inflammatory infiltrate (34% of cases) does not preclude the diagnosis [82, 99, 106–108]. However, there is no histopathological feature that is pathognomonic of AIH. Other individual histological features such as interface hepatitis, plasma cells, and emperipolesis are also not specific for AIH, and patients with other disease such as DILI, viral or immune-mediated diseases could show similar features [99, 109–119].

Hepatic rosette: a small group of hepatocytes arranged around a small central lumen formation of the hepatocytes forming a pseudoglanular structure [82, 101]

Emperipolesis has been widely described in classical AIH and included in the simplified International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group scoring system (2008) [73, 120]. The presence of emperipolesis indicates a close immune interaction between lymphocytes and hepatocytes, which may subsequently induce hepatocyte apoptosis and has been proposed as an additional mechanism of autoimmune-mediated liver injury in AIH [121].

- Other features of classical AIH

- Giant cell hepatitis

- Pigmented macrophage, Kupffer cell hyperplasia

- Bile duct injury usually mild–moderate (nondestructive cholangitis)

- Endotheliitis, endothelial injury, sinusoidal infiltration

- Granuloma

Histologic features of acute presentation

Centrilobular necrosis (CN) is found in 21.8–100% of AIH patients with acute presentation [61, 101–103, 105, 125–127]. CN has been more frequently found in the acute hepatitis phase (100%) than in the acute exacerbation phase of AIH (42%) [61]. Its prevalence also increases with disease severity [128]. It was more often observed in AIH with an acute presentation than in that with a chronic presentation (53 vs. 17.5–30.7%) [61, 105, 129–131]. Some cases with CN and without or with minimal portal involvement, representing typical acute hepatitis, may progress to classic AIH [127, 132–136]. CN with plasma cell infiltration is useful for supporting the diagnosis of AIH with acute presentations.

Histological features of acute hepatitis, including CN, submassive necrosis and massive necrosis, were present in 12.2–88% cases [58, 61, 102, 127, 128, 137–143].

Other features in AIH with acute presentation:

• Interface hepatitis (66.7–92.3%) [63, 102, 104, 105, 127, 144]

• Hepatic rosette formation (14.6–60.5%) [61, 63, 105, 127, 137, 142, 145]

• End-stage fibrosis (stage 4) (0–33.3%) [58, 104, 126, 141, 144, 146].

• Lobular necrosis/inflammation (73–100%) [103–105, 126, 142, 144]

• Cobblestone appearance of hepatocytes (44.4–82.6%) [101, 142]

Recommendations

Liver biopsy is very important for the diagnosis of AIH, but because there is no specific histological hallmark, an experienced pathologist is needed for the diagnosis. It is recommended to evaluate the degree of inflammatory activity by HAI score. For the difficult cases, communication with the clinicians is necessary.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of AIH is based on the presence of typical clinical, laboratory features (including increased serum immunoglobulin G (IgG)/gamma-globulin levels, presence of autoantibodies), combined with pathological examination, and exclusion of other causes of liver diseases [e.g., chronic viral hepatitis, alcoholic liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), drug-induced liver injury, and Wilson’s disease].

Clinical features

AIH primarily affects females, especially in childhood/teenage years and in middle age [66, 147]. Most of AIH patients has no apparent symptom or only present some non-specific symptoms. The presentation of AIH at onset is variable, ranging from asymptomatic to acute/severe or even fulminant, about one-fourth of AIH patients present with an acute onset, among these patients, some present with the acute exacerbation of chronic AIH, and others present with the true acute AIH without histological findings of chronic liver disease. One-third of patients at diagnosis have already developed cirrhosis due to delay in diagnosis, irrespective of the presence of symptoms.

Laboratory findings

Increased immunoglobulin G/gamma-globulin levels, presence of circulating autoantibodies, and elevation of aminotransferase levels, are the important laboratory characteristics of AIH. Than et al. reported the level of IgG in Singapore Asian and United Kingdom Asian were 16.7–33.3 g/L and 15.5–30.6 g/L, respectively [148]. In Japan, the peak of serum IgG levels in AIH patients ranged from 15 to 20 g/L [149]. In China, Ma’s research group reported the mean IgG levels in classical AIH patients with decompensated cirrhosis were 24.1 g/L ranged from 10.9 to 48.4 g/L, but in the patients with autoantibody-negative AIH, the IgG levels were lower than those in the classical AIH [151, 152]. In serum biochemistry, the AIH patients have a typical hepatitic pattern, included elevation of serum aminotransferases or bilirubin, and normal or only mildly raised serum alkaline phosphatase. Serology is very important to the both diagnosis and classification of AIH, serological tests should be completed in all patients for the definitive diagnosis of AIH. Most of AIH present with one or more significant titers autoantibodies. ANA, smooth muscle antibodies (SMA) and antibodies to kidney microsome-1 (anti-LKM1) are standard autoantibodies. According to the pattern of autoantibodies detected, AIH is classified into two types, ANA and/or SMA antibody characterize type 1 AIH (AIH-1) which accounts almost for 90% of cases, anti-LKM1 and antibodies to liver cytosol type1 (anti-LC1), characterize type 2 AIH (AIH-2). However, these auto-antibodies are not fully AIH specific, as they may also be found in various liver disorders. Although antibodies to soluble liver antigen/liver-pancreas (anti-SLA/LP) are highly specific markers for AIH in both AIH-1 and AIH-2 [153, 154], none was positive for anti-SLA in 154 Japanese patients with type 1 AIH, anti-SLA/LP positivity seems to be unusual in APASL group [155]. The presence of an autoantibody is a common feature of AIH, in acute-onset AIH or corticosteroid-treated AIH, autoantibodies can be absent or loss [156, 157]. It was reported that in Japan, ANA negative or less than 1:40 were seen in 29% of severe or fulminant AIH, and 39% of acute-onset AIH patients [102, 142]. In China, circulating autoantibodies were absent in about 10.2% of AIH patients [152]. The nonstandard autoantibodies, including antibodies to actin (anti-Actin), antibodies to alpha-Actinin (anti-α-Actinin), atypical perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (p-ANCA) and antibodies to asialoglycoprotein receptor (anti-ASGPR), can support or extend the diagnosis of AIH whom the standard biomarkers are insufficient to render a diagnosis. Anti-SLA/LP characterizes type 1 AIH, and anti-LC1 characterizes type 2 AIH.

Histology

Liver histology is important not only in confirming the clinical diagnosis of AIH, but also in differential diagnosis of AIH, it plays a major role in clinical diagnosis scoring systems. The typical histological features of AIH are precisely described in the pathology section of this guidance.

Non-invasive assessment of fibrosis

Although liver biopsy is a golden standard for evaluation of the liver inflammation and fibrosis, it is an invasive and expensive procedure, non-invasive assessment methods are repeatable, inexpensive and well accepted. Several non-invasive laboratories and radiology-based methods have been developed to assess the stage of fibrosis in chronic liver diseases, including AIH.

The FibroTest® [158], the serum AST/platelet ratio index (APRI) [159], the Fibrosis-4 index (FIB-4) [160], and the enhanced liver fibrosis (ELF) test [161], angiotensin-converting enzyme levels [162], neutrophil lymphocyte ratio, mean platelet volume, red cell distribution width [163–165] are possible candidate laboratory markers of hepatic fibrosis in AIH.

Transient elastography (FibroScan) is gradually replacing the liver biopsy as a reliable tool to monitor chronic liver disease, including AIH. In Asia–Pacific region, transient elastography was helpful in predicting significant liver fibrosis in AIH [166, 167].Chinese researchers reported the diagnostic accuracy of FibroScan for detecting of fibrosis in AIH patients. Liver stiffness measurement by FibroScan was superior to other non-invasive markers in assessing the fibrosis of AIH patients, and the optimal cut-off values of liver stiffness measurements was 6.27, 8.18 and 12.67 kPa for stage F2, stage F3 and stage F4, respectively [166]. Transient elastography can be routinely used for noninvasive staging of hepatic fibrosis in AIH patient either in the diagnosis at onset or during the follow-up. Acoustic Radiation Force Impulse (ARFI) elastography could differentiate significant from non-significant liver fibrosis in patients with AIH and this non-invasive method can also be used for monitoring fibrosis progression in AIH [168, 169]

A recent study has evaluated performance of magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) and findings of MRE were strongly correlated with advanced fibrosis stage in AIH [170]. The role of these non-invasive methods is a merit in assessing or monitoring the hepatic fibrosis, treatment response as well as disease outcome.

But hepatic inflammation, necrosis, and swelling can impact liver stiffness, such as excessive hepatocyte apoptosis and necrosis can activate HSCs, and the ongoing fibrogenesis can cause liver stiffness increased, in the concomitance of aminotransferase flares, especially in advanced fibrosis and cirrhotic patients presenting with a clinical pattern of acute hepatitis, non-invasive assessment methods are not reliable instruments.

Diagnostic methods

Revised original diagnostic scoring system of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group (IAIHG) [72]

The revised original scoring system is a diagnostic method to ensure the systematic evaluation of patients [171]. This scoring system was based on 12 clinical components, originally developed as a tool for scientific purposes [172] (Table 2). It can distinguish AIH patients from cryptogenic hepatitis, and for patients suspected of AIH, the revised original Diagnostic scoring system can support the diagnosis by rendering a composite score of corticosteroid treatment response. In Asia–Pacific area, it was reported a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 93% to detect in Japanese AIH patients [173]. Though the revised original diagnostic criteria were incorporated into clinical diagnosis of AIH, it is a very complex score system, and even including a variety of parameters of questionable value, it is difficult for wider applicability in routine clinical practice.

Table 2.

Revised original diagnostic scoring system of the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group in 1999

| No. | Clinical feature | Score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Female | + 2 | |

| 2 | ALP/AST (or ALT) ratio | ||

| < 1.5 | + 2 | ||

| 1.5–3.0 | 0 | ||

| > 3.0 | − 2 | ||

| 3 | Serum globulin or IgG level above ULN | ||

| > 2.0 | + 3 | ||

| 1.5–2.0 | + 2 | ||

| 1.0–1.5 | + 1 | ||

| < 1.0 | 0 | ||

| 4 | ANA, SMA, or anti-LKM1 | ||

| > 1:80 | + 3 | ||

| 1:80 | + 2 | ||

| 1:40 | + 1 | ||

| < 1:40 | 0 | ||

| AMA positive | − 4 | ||

| 5 | Hepatitis markers | ||

| Positive | − 3 | ||

| Negative | + 3 | ||

| 6 | Hepatotoxic drug exposure | ||

| Positive | − 4 | ||

| Negative | + 1 | ||

| 7 | Average alcohol intake (g/day) | ||

| < 25 | + 2 | ||

| > 60 | − 2 | ||

| 8 | Histologic findings | ||

| Interface hepatitis | + 3 | ||

| Lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate | + 1 | ||

| Rosette formation | + 1 | ||

| None of the above | − 5 | ||

| Biliary changes | − 3 | ||

| Other atypical changes | − 3 | ||

| 9 | Concurrent other immune disease | + 2 | |

| 10 | Other autoantibodies | + 2 | |

| 11 | HLA DRB1*03 or DRB1*04 | + 1 | |

| 12 | Response to corticosteroids | ||

| Complete | + 2 | ||

| Relapse after drug withdrawal | + 3 | ||

| Aggregate score pretreatment | |||

| Definite AIH | > 15 | ||

| Probable AIH | 10–15 | ||

| Aggregate score posttreatment | |||

| Definite AIH | > 17 | ||

| Probable AIH | 12–17 | ||

ALP alkaline phosphatase, AST aspartate aminotransferase, ALT alanine aminotransferase, IgG immunoglobulin G, ULN upper limit of the normal range, HLA human leukocyte antigen, ANA antinuclear antibodies, SMA smooth muscle antibodies, anti-LKM1 antibodies to liver kidney microsome type 1, AMA antimitochondrial antibodies

Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of AIH [174]

To simplify the use of revised original diagnostic scoring system, the IAIHG defined simplified diagnostic criteria for routine clinical practice in 2008. The simplified score system is a reliable and simple tool to establish and exclude the diagnosis of AIH more frequently in liver diseases concurrent with immune manifestations, it was purely meant for clinical purposes [174] (Table 3). The simplified score system has superior specificity and accuracy comparing to the original revised scoring system [174], but only includes four clinical components, and no treatment response in the scoring system, it is generally accepted that simplified score system has a lower sensitivity [175]. However, it is exciting to find that in Asia, the simplified criteria for the diagnosis of AIH has higher sensitivity and specificity than the revised original diagnostic scoring system. In Chinese AIH patients, the sensitivity and specificity were 90 and 95% for the probable AIH, and 62 and 99% for definite AIH [176]. In Japan, the sensitivity and specificity of simplified diagnostic criteria for AIH was 85 and 99%, respectively, in diagnosis of the AIH [173]. In Korea, the diagnostic sensitivity and positive predictive value of the simplified diagnostic criteria were 69.9 and 86.4%, respectively [177]. The simplified criteria are generally useful for the diagnosis of AIH with typical AIH features, but it will be not applicable for patients with atypical features, such as serum IgG levels under the upper normal limit, ANA or SMA titres less than 1:40, and patients with acute hepatitis who need to start immunosuppressive treatment [173]. When the score of the simplified scoring system is lower than 6, the revised scoring system should be considered to further determine whether there is AIH.

Table 3.

Simplified criteria for the diagnosis of AIH

| Clinical feature | Result | Score | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | ANA or SMA | ≥ 1:40 by IIF | + 1 |

| ANA or SMA | ≥ 1:80 by IIF | + 2* | |

| Anti-LKM1 (alternative to ANA and SMA) | ≥ 1:40 by IIF | + 2* | |

| Anti-SLA (alternative to ANA, SMA and anti-LKM1) | Positive | + 2* | |

| 2 | IgG | > UNL | + 1 |

| > 1.1 UNL | + 2 | ||

| 3 | Liver histology | Compatible with (evidence of hepatitis is a necessary condition) | |

| AIH | + 1 | ||

| Typical AIH | + 2 | ||

| Atypical AIH | 0 | ||

| 4 | Absence of viral hepatitis | Yes | + 2 |

| No | 0 | ||

| Total scores | ≥ 6: probable AIH | ||

| ≥ 7: definite AIH |

*Sum of points achieved for all autoantibodies (maximum 2 points)

Diagnosis of AIH-PBC overlap syndrome

“Paris criteria” is the most common and effective method used to diagnosis the AIH-PBC overlap syndrome. It requires at least two of the following three diagnostic criteria for each disease: for diagnosis of PBC: (1) Serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels at least two times the upper limit of normal (ULN) or serum gamma glutamyl transferase (GGT) levels at least five times ULN; (2) Presence of anti-mitochondrial antibodies (AMA); (3) A liver biopsy specimen showing florid bile duct lesions. For AIH, it requires two of the following three diagnostic criteria: (1) Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) activity > 5 times ULN; (2) IgG ≥ 2.0 times ULN and/or positive SMA; (3) Liver biopsy with moderate or severe interface hepatitis [178].

“Paris criteria” is a classic method for diagnosing AIH-PBC overlap syndrome. In China, the specificity of Paris criteria for AIH-PBC overlap syndrome was 100%, but the sensitivity was only 10%. Ma’s research group reported, in Chinese AIH patients when modified the Paris criteria by using a lower threshold, serum IgG levels as ≥ 1.3 ULN, the diagnostic sensitivity and specificity had been improved to 60 and 97%, respectively [179]. Except for Paris criteria, the revised original Diagnostic scoring system of the IAIHG and simplified AIH scoring system have also been applied to determine overlap syndrome, but the former were designed for the diagnosis of AIH with the exclusion of PBC, it was not an optimal diagnostic criteria, as for simplified AIH scoring system, it has been gradually accepted for diagnosing PBC–AIH overlap syndrome, especially in Chinese patients [166].

Diagnosis of AIH-PSC or IgG4-related SC overlap syndrome

AIH-PSC overlap syndrome is regarded as a variant of PSC. It is uncommon, but when PSC patients present some clinical features of AIH, AIH-PSC overlap syndrome need to be excluded. The diagnosis of PSC is based on the alteration of cholestatic enzymes, the typical changes of the biliary tree with multifocal strictures and segmental dilatation by magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) or direct cholangiography (ERCP) [180]. In 2000, Mayo clinic reported the revised AIH scoring system seems to be more precisely for the diagnosis of AIH-PSC [181]. In 2017, Ma’s group reported their data on 148 PSC patients, in these patients, when used the simplified criteria of AIH, 36 AIH-PSC overlap syndrome diagnosis was established, when serum IgG4 level was more than 1.25 ULN, it would be helpful to differential diagnosis IgG4-SC among SC patients [182].

Differential diagnosis of AIH

AIH usually presents with features of acute or chronic hepatitis, and lacks a specific diagnostic method, sometimes it is difficult to differentiate from other causes of liver diseases, such as DILI, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), viral hepatitis, or hereditary metabolic liver diseases et al.

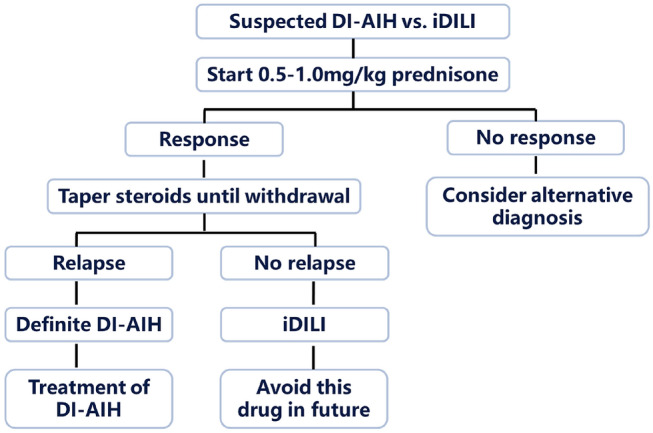

DILI

DILI, especially the idiosyncratic DILI has features similar to those of other liver diseases including AIH. Idiosyncratic DILI can mimic the clinical features of AIH, the circulating autoantibodies and a hypergammaglobulinemia are frequently present in sera, even the hepatic histology demonstrate interface hepatitis with a prominent plasma cell infiltrate. Drug may serve as a trigger for induction of persistent AIH. Distinguishing DILI from AIH can be extremely difficult in these patients, a liver biopsy should be recommended to determine the diagnosis [113]. A response to corticosteroid therapy and a lack of recurrence of symptoms or signs following corticosteroid cessation can distinguish AIH-DILI from idiopathic AIH [183], and support DILI diagnosis.

NAFLD or concurrence with steatohepatitis

NAFLD has some similar clinical and histological features with AIH. Low titers of autoantibodies (ANA, SMA and/or AMA) and increased γ-globulins, can appear in part of NAFLD patients [184]. In the histological features, lobular inflammation and hepatocyte ballooning can present both in AIH and NAFLD, by using the simplified scoring system for AIH, these features may be misdiagnosed NAFLD as having probable AIH [150] [174]. Furthermore, in the corticosteroid-treated AIH patients, corticosteroid-related side effects, insulin resistance or dyslipidemia can induce the development of fatty liver [66]. Though differential diagnosis of AIH and NAFLD is difficult, the levels of hepatobiliary enzymes (ALT, AST, ALP, GGT) in AIH patients with NAFLD were lower, and the lobular inflammation was less compared to the pure AIH patients [185].

Viral hepatitis or concurrence with viral hepatitis

Acute onset of AIH can present acute viral hepatitis like illness especially in absence of autoantibodies and hypergammaglobulinemia. It is necessary to complete serological testing to exclude hepatophilic virus infection before the diagnosis of definite or probable AIH.

For untreated AIH, acute hepatitis virus A (HAV) and acute hepatitis virus E (HEV) infection are common. Acute HAV infections were higher in treatment-naive pediatric AIH patients. [186], and acute HEV infections were higher in treatment-naive adult AIH patients [187]. For the AIH patient undergoing the conventional immunosuppressive therapy, who has persistent abnormal liver function test results, chronic hepatitis E needs to be excluded, and testing for HEV RNA is recommended [187].

ANA, SMA and anti-LKM-1 are commonly detected in the sera of patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) or chronic hepatitis C(CHC) [188] [189]. Only 0.83% of Chinese AIH patients were infected by HBV. It seems, HBV in Chinese AIH patients is easier to be cleared [190]. In India, ANA and SMA positivity rate in CHB patients were 27.1 and 25.7%, respectively, while in CHC patients, the positivity rate was 26.9, 46.1 and 11.1% for ANA, SMA, and LKM, respectively. HBV infection in Indian may induce AIH type I, and chronic HCV infection usually causes AIH-Type 2 [191]. The diagnosis of AIH is challenging in these patients because of low sensitivity and specify of AIH scoring systems. In these patients, a definitive diagnosis of AIH should be based on a combination of serological profiles, histological findings, scoring systems, treatment response, and outcomes [99, 192]. The resolved HBV can be reactivated during immunosuppressive therapy for AIH, treating HBV before immunosuppressive therapy or closed follow-up during immunosuppressive therapy is vital.

Concurrence with other chronic liver disease

Hereditary metabolic liver disease, such as Wilson disease [193], hemochromatosis [194] can present the features of AIH, and in some AIH patients, laboratory tests showed elevated serum ferritin level, even have a heterozygous C282Y mutation [195].

Concurrence with other autoimmune liver diseases

AIH patients may show the cholestatic biochemical profile, and even present some serological markers of PBC, PSC and IgG4-related cholangitis [182, 196, 197], these made the diagnosis of AIH more difficult. Liver biopsy and biliary tree imaging should be recommended in these AIH patients to highlight the predominant liver disease and choose the appropriate treatment regimens [120].

Guidance

The diagnosis of AIH should be based on the autoantibodies (standard autoantibodies-ANA, SMA and Anti-LKM1), elevated IgG or serum globulin, interface hepatitis, and exclusion of other causes of liver disease.

Circulating autoantibodies can be negative in part of AIH patients, especially whom in acute AIH or during corticosteroid treatment.

Transient elastography can be routinely used for AIH patient either in diagnosis at onset or during the immunosuppressive therapy follow-up.

In Asia–Pacific region, the simplified criteria for the diagnosis of AIH has higher sensitivity and specificity, it can be used to diagnosis AIH, AIH-PBC and AIH-PSC/IgG4-related SC overlap syndromes.

Treatment

Aim

The aim of AIH treatment is to achieve complete biochemical and histological resolution, to suppress inflammatory activity, to prevent fibrosis progression and onset of end-stage events, eventually to prolong survival and improve life quality of patients.

AIH is a chronic and progressive hepatitis, and could promptly progress to cirrhosis if untreated. Several randomized controlled studies were conducted in the 1960s and 1970s [198–202], and a systematic review of these randomized trials was published in 2010 [203]. Among them, Cook et al. conducted a randomized, controlled, prospected clinical trial in patients with active chronic hepatitis between prednisolone monotherapy (15 mg/day) and placebo. After 72 months of observation, three out of 22 patients treated with prednisolone (14%) and 15 out of 27 patients with placebo (56%) had died [198]. The mean value of AST, serum bilirubin and albumin in placebo group was 118 IU/L, 3.8 mg/dL and 3.0 g/dL, respectively, indicating that AIH patients with decompensated cirrhosis have a high mortality, 56% at 6 months, while intervention with prednisolone decreased mortality to 14%. Another placebo-controlled trial was performed by Soloway et al., in which 17 patients with chronic active hepatitis served as a placebo control [200], and again high mortality (41% died up to 3.5 years) was noted. Even without cirrhosis at presentation, AIH patients with bridging necrosis or multilobular necrosis are likely to progress to cirrhosis in a few years if untreated, and long-term prognosis is poor [204, 205].

On the other hand, the natural history of asymptomatic AIH patients with mild laboratory and histological abnormalities remains largely unknown [66]. Feld et al. demonstrated that AIH patients with asymptomatic at presentation, who had lower serum aminotransferase, bilirubin and IgG, had a good prognosis with 80.0% of 10-year survival even though half of these patients received no treatment, while patients with cirrhosis at baseline exhibited poorer 10-year survival (61.9%) [52]. Nevertheless, 80% of the 10-year survival does not appear to be excellent currently since 10-year survival of patients with AIH exceeds 90% [206]. Furthermore, there have been no biomarkers or histological findings to identify “safe” AIH patients who do not require corticosteroids therapy. It should be noted that the mild AIH can progress to severe fibrosis, leading to poor outcomes.

Recent study, however, suggested the long-term outcome of AIH is now excellent if patients are appropriately managed. In a retrospective cohort study in Japan consisting of 203 patients who were treated with immunosuppressive agents, the overall survival was comparable to those of the general population and 10-year survival was more than 90% [206]. Of note, fibrosis staging at baseline and onset type (acute or chronic) was not associated with the prognosis. Therefore, it is important to bring about biochemical resolution with immunosuppressive treatment for achievement of the improved long-term outcome in AIH.

Biochemical resolution is defined as reduction of transaminase and IgG levels to normal. A clinical study from India [207] showed early treatment coincides with favorable long-term prognosis and failure to normalize alanine aminotransferase is a risk factor predicting disease related mortality or transplantation. A retrospective study demonstrated that more than 50% patients who achieved transaminase level below twice ULN still underwent histological progress [208]. On the other hand, it has been justified that escalating IgG levels are also associated with liver inflammatory activity in AIH patients [209]. Therefore, normalization of both transaminase levels and IgG levels have been considered as the markers of complete biochemical remission [66]. A recent clinical investigation in 120 AIH patients suggested that complete biochemical remission is not only a conceivable surrogate marker for histological disease activity as evidenced by liver biopsies, but also a predictor for the promising prognosis, because the resolution of inflammation leads to fibrosis regression [79]. Moreover, patients with a rapid biochemical response at 8 weeks post-therapy also have a lower risk of liver-related death or transplantation [210]. To assist physicians to establish therapy schemes, we advocate to determine efficacy of medications by examining serum alanine transaminase and IgG levels at 6 months after treatment [211].

Besides, psychological comorbidity of patient is another important issue that needs early recognition and prompt intervention. It was reported that a major depressive syndrome and severe symptoms of anxiety were found to be significantly more frequent in AIH patients compared to the general population [212], which contributed to an increased risk of noncompliance to AIH therapy [213].

Indications of treatment

In 2010, the AASLD recommended either of following criteria is absolute indication for corticosteroid treatment [66]: serum ALT/AST level above tenfold ULN, more than fivefold ULN plus serum IgG level more than twice ULN, histological features of bridging necrosis or multilobular necrosis, incapacitating symptoms. In addition, asymptomatic patients with mild laboratory and histological disorder may be considered for treatment. In 2011, the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines proposed treatment in all cases with the serum aminotransferases more than fivefold ULN or serum globulins level at least two times ULN or liver biopsy showing confluent necrosis [39]. In 2015, however, EASL expanded indications to all patients with active AIH [12]. These three guidelines issued at various time reflected the tendency that the treatment threshold was decreasing.

AIH is characterized as a fluctuating and unpredictable inflammation in liver, which leads to end-stage liver diseases, cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma [52, 53, 214]. Therefore, suppression of hepatic inflammation is pivotal to prevent disease progression and improve prognosis [215–217]. Given serum aminotransferases as faithful surrogate markers for hepatic inflammation, it is recommended that all patients with elevated serum aminotransferases should receive treatment [218]. But still a fraction of patients display inflammatory activity on liver histology despite normal aminotransferases [79, 209]. Among them, elevated IgG levels can also reflect ongoing inflammatory activity [209]. Besides, transient elastography is regarded as an applicable non-invasive tool to assess liver inflammatory edema and fibrosis with a high accuracy and repeatability [97, 98]. Finally, liver biopsy is an efficacious strategy to evaluate histological inflammation and fibrosis albeit concomitant risks of sampling error and severe complications [219]. If patients in spontaneous remission cannot accept liver biopsy, the monitoring must be closely followed up every 3–6 months [12]. In sum, patients whose manifestations fulfill either of following criteria—increased IgG levels, enhanced liver stiffness, abnormal histological activity—should be considered for treatment.

Standard treatment

Standard treatment modalities

The 5-year survival rate of 82% in patients treated with steroids compared to 32% in untreated patients highlighted the efficacy of steroids therapy, because it was proved to suppress inflammation and improve liver biochemical abnormalities [220]. Another clinical investigation demonstrated 57% (13/23) patients avoided liver transplantation as a result of the response to corticosteroid-based therapy [221]. The current immunosuppressive treatment modality mostly originates from the studies published in the 1970s [198–200]. An influential comparison study was performed between prednisone monotherapy, azathioprine monotherapy, combination therapy and placebo. There was a mortality benefit from prednisone monotherapy or combination therapy when compared to placebo (6 vs 7 vs 41%). These two regimes had also similar beneficial effects from histological, biochemical and clinical profiles, but the combination regime was associated with fewer side effects than prednisolone monotherapy (10 vs 44%). On the other hand, azathioprine monotherapy resulted in a higher mortality (36%) and more adverse events (30%) compared to prednisone monotherapy [200]. Thus, the combination therapy of prednisone and azathioprine acted as the frontline regimen.

In 2010, AASLD guidelines [66] suggested starting treatment with prednisone alone (60 mg daily) or with a lower dose of prednisone (30 mg daily) plus azathioprine (50 mg daily), then tapering down over 4 weeks to 20 mg daily which is further continued to reduce until treatment endpoint. Based on BSG guidelines in 2011 [39], 30 mg daily of prednisone is introduced and 5–10 mg daily is maintained in the end. EASL clinical practice guidelines recommended the proposed dose of prednisone in initiating at 60 mg/day and reducing to 20 mg over 6 weeks combined with azathioprine of 1–2 mg/kg [12]. Since the rapid biochemical response is predictive of a low frequency of fibrosis progression and a decreased mortality [222], a retrospective study from Turkey showed starting prednisolone dose of 40 mg daily and tapering over 9 weeks in partnership with azathioprine were more favorable compared to the initial 30 mg daily with a faster dose reduction protocol in 3-month biochemical response (69.2 vs. 43.8%, p = 0.031) and 12-month overall survival (100 vs. 87.5%, p = 0.048), but not 6- and 12-month biochemical response (79.5 vs. 59.4%, p = 0.065 and 89.5 vs. 80.6%, p = 0.30), and relapse ratio (35.9 vs. 50%, p = 0.23). Meanwhile, no severe prednisolone-related side effects were identified in either group [223] (Table 4). A nationwide survey in 1292 Japanese patients revealed the initial and maintenance dosage of prednisolone that most patients took were 30–40 mg daily and 5–7.5 mg daily, accounting for 39 and 50.6%, respectively [149]. The evidence from China suggested that HLA-DR4 is the predominant disease-susceptible gene and clinical manifestations of those patients are milder, a lower initial dose with 0.5–1 mg/kg daily of prednisone can achieve a satisfactory response [1]. A meta-analysis of 25 studies containing 3305 patients, demonstrated that 60 mg/day or 1 mg/kg/day of glucocorticoid achieved higher levels of biochemical remission, yet also caused more side effects incidence compared with the low dose (40–50 mg/day or 0.5 mg/kg/day) group (79 vs. 72% and 42 vs. 39%, respectively) [224]. A recent European multi-center study showed that overall remission induction rates after 6 months of therapy were similar in patients treated with either high- or low-dose (≥ 0.50 vs. < 0.50 mg/kg/day, respectively) prednisone and advocated an initial low dose prednisone for the treatment of AIH [225]. And the starting dosage could be further lowered to 20 mg daily if incorporation with azathioprine 50–150 mg daily. Indeed, we prefer 50 mg daily for azathioprine to prevent its adverse effects in Asian population empirically. On the other hand, we also encourage to start it until 2 weeks after usage of prednisone to confirm steroid responsiveness, because the discontinuation rate of azathioprine could reach 15% in the first year of treatment [226]. Taken all together, we proposed the treatment regimen is dependent on the severity of disease. The treatment protocol is shown in Table 4 if fulfilling either of the following criteria: serum ALT/AST level above tenfold ULN, more than fivefold ULN plus serum IgG level more than twice ULN, histological features of bridging necrosis or multilobular necrosis, incapacitating symptoms. Otherwise, relatively low-dosage regimens modality is a better treatment option for the patients with mild disease behavior (Table 4).

Table 4.

Treatment regimen for AIH patients

| Combination therapy | Monotherapy | |

|---|---|---|

| Prednisone | Azathioprine | Prednisone |

| 20 mg daily × 2 weeks | 50–150 mg daily | 30–40 mg daily × 2 weeks |

| 15 mg daily × 2 weeks | 25–30 mg daily × 2 weeks | |

| 10 mg daily × 4 weeks | 20–25 mg daily × 4 weeks | |

| 5 mg daily maintenance | Tapering till to 5 mg daily maintenance | |

Side effects

Almost half of AIH patients present cosmetic changes or obesity after the usage of steroids [227]. Severe, but less frequent steroid side effects include osteoporosis, diabetes mellitus, cataract, psychosis and hypertension [66]. It was reported that diabetes mellitus occurs in 15–20% of treated AIH patients and the morbidity of hypertension, psychosis, cataract, vertebral collapse related to osteoporosis is between 5 and 10% [199, 200]. To prevent or treat osteoporosis, periodic dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) scanning and medical therapy, including supplemental calcium, vitamin D and bisphosphonates, are essential for patients who receive long-term steroid therapy [228]. Side effects occur mostly at dose more than 20 mg daily for more than 18 months and resulted in therapy termination in 15% patients. Therefore, supplementation with azathioprine is warranted to reduce onset of steroids specific adverse events [203]. On the other hand, a recent study demonstrated corticosteroid use is strongly associated with impaired health-related quality of life in AIH patients independently of steroid type, dose and biochemical remission status. This highlights novel corticosteroid-free therapy approaches are required to circumvent corticosteroid-related side effects in AIH [229]. On top of this, a retrospectively collected data on 476 patients suggested a low-dose prednisone (0.1–5.0 mg/day) increased the odds of fractures whereas higher doses (> 5.0 mg/day) increased the odds of cataracts and diabetes. Thus, even low doses of corticosteroids frequently lead to substantial adverse events arguing against the assumption that adverse events are prevented by administering low doses [230].

The most common side effect of azathioprine is bone marrow suppression. Thus, it should be avoided in patients with severe pretreatment cytopenia (white blood cell counts below 2.5 × 109/L or platelet counts below 50 × 109/L) and testing for the genetic polymorphism of two azathioprine-based catabolic enzymes, thiopurine methyltransferase (TPMT) and NUDT15, should be encouraged before treatment. In the Caucasian population, approximately 11 and 0.3% presented heterozygous and homozygous TPMT variant, respectively [231]. In contrast, an investigation on prevalence of TPMT polymorphism from 126 Indian patients found only 4.77% patients carrying heterozygous alteration and none bearing homozygous mutation [232], as with Chinese and Japanese patients [233, 234]. In search of other factors contributing to the higher incidence of adverse reactions in Asian patients [235], p.Arg139Cys mutation in NUDT15 was firstly reported to associate with azathioprine-induced early leukopenia in Koreans [236]. Then, recent evidences suggested that it was detectable in 4.4–10.5% of the populations from Asian countries [237–239]. For homozygous TPMT or NUDT15 variation with low concentration of enzyme, azathioprine should be contraindicated, because it will lead to severe cytopenic and septic complications. For heterozygous mutation, it should begin at a lower dose with monitoring of white cell count during treatment [66, 240, 241]. Another possible complication of long-term treatment with azathioprine is the development of malignancies at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day [242]. Moreover, azathioprine has its own profile of toxic effects, such as nausea, vomiting, rashes, pancreatitis and hepatotoxicity [243, 244]. Thus, EASL recommended that it should be introduced after 2 weeks of prednisone alone to distinguish between azathioprine-induced hepatotoxicity and nonresponse to prednisone particularly in cirrhotic and jaundiced patients [245]. Of note, its side effects more commonly take place in cirrhotic patients. About 5% of patients develop one manifestation such as arthralgias, fever, rash or abdominal pain which might require prompt discontinuation [246]. Long-term azathioprine therapy in a large number of pregnant female were found no increase in the risk of low birth weight or teratogenicity [247]. Therefore, azathioprine was approved to continue throughout pregnancy by 2019 AASLD guidelines [248]. Moreover, it is regarded safe for breastfeeding although small amount of metabolite can be quantified in breastmilk [249].

Duration of treatment

Most of AIH patients respond well to frontline regimen and achieve biochemical normalization [222, 250, 251]. But relapse after treatment withdrawal becomes a major issue. One study of 30 patients who had been in remission for between 1.5 and 9 years suggested only three remained improvement in 1 year after treatment withdrawal, and ultimately all relapsed [252]. Other studies showed that 50–90% of patients relapsed after 3-year post-discontinuation [253, 254]. A clinical study from Turkey also pointed out relapse is very frequent and only 4.2% patients were off immunosuppressive treatment finally [223]. Another study suggested that normal liver biochemistry (ALT levels less than half the ULN and IgG levels not higher than 12 g/L at the time of treatment withdrawal) can predict success rates of permanent immunosuppressive withdrawal. However, these results need to be validated further [255]. Because most of the reports underlined relapse is quite common after treatment discontinuation and current immunosuppressive therapy only represses inflammation temporarily and the histological improvement lags greatly behind lab test improvement, most patients need the long-term treatment except cirrhosis and significant fibrosis because they will bring forth more severe side effects [256]. As encountering a public health emergency, the telehealth system is as effective and useful in the management of AIH as in regular time [257].

Regarding the previous criteria about treatment endpoint, AASLD guidelines [66] mentioned the termination of treatment might be considered after at least 2-year course only for the patients with biochemical and histological normalization. BSG guidelines [39] proposed re-biopsy is advisable in 1–2 years after serum transaminases normalization. Even histological remission presents, maintenance strategy still needs to be implemented. EASL guidelines [12] recommended that treatment should proceed for at least three years and for at least 2 years after complete normalization of serum transaminases and IgG levels. For patients with severe manifestation and low tolerance to treatment, a liver biopsy before treatment withdrawal should be performed. These guidelines collectively suggested the criteria of treatment endpoint should be stringent. Therefore, we propose the treatment withdrawal can be taken into consideration only in the context of complete biochemical remission for at least 2 years [12] or histological examination shows a alleviated histological disease activity (HAI > 3), is achieved [12, 209], because histological examination is more accurate to evaluate the real status quo in liver and predict fibrosis progression and relapse.

During the course of treatment, efficacy parameters need to be monitored as shown in Table 5. If either serum aminotransferases or IgG titers cannot improve, the prednisone dose should maintain in conditions of below 20 mg daily as a stand-alone therapy. Notably, transient elastography can be used to measure the liver stiffness reflective of the severity of inflammatory edema or fibrosis [12]. Furthermore, the likelihood of HCC development calls for periodic workup of abdominal ultrasonography and tumor markers [70].

Table 5.

Treatment efficacy monitoring program

| Variable | Induction therapy | Maintenance therapy |

|---|---|---|

| Liver biochemistry | Every 1–3 months | Every 6 months–1 year |

| Serum IgG | Every 1–3 months | Every 6 months–1 year |

| Serum autoantibodies | Every 3 months | Every 6 months–1 year |

| HCC-associated tumor markers | Every 6 months | |

| Abdominal ultrasonography | Every 1 year | |

| Transient elastography | Every 1 year | |

| Liver biopsy | Non-response, incomplete response, before the treatment withdrawal | |

Management to difficult-to-treat patients

A lack of a reduction of transaminases by more than 25% in 2 weeks or a worsening of coagulation markers or bilirubin levels should be characterized as non-response [12]. In this case, three possibilities need to be excluded, i.e., non-compliance, analogous diseases with AIH, such as viral hepatitis, Wilson’s disease, NASH, DILI, PSC or PBC, and the concomitant cholestatic syndrome that may be refractory to the original treatment. Liver biopsy might favor to distinguish following reconfirmation of adherence. For AIH patients with non-response, dosage of prednisolone and azathioprine should be increased or alternative medications should be implemented [258]. One strategy is to increase the dosage of prednisone to 60 mg daily or increase the azathioprine dosage to up to 150 mg daily in combination with prednisone 30 mg daily for 2 weeks [66]. In concurrent regimen, 6-TGN, the metabolite of azathioprine, should be measured regularly to evaluate patient’s compliance and avoid toxicity [259].

For AIH patients with incomplete response, if any effort to normalize transaminases is not achievable, it should be adjusted to maintain transaminase level below threefold greater than upper limit of normal to reduce the likelihood of aggressive interface hepatitis and progression of the disease [260].

It is estimated that 10–15% of patients on standard therapy discontinued treatment due to intolerable side effects [261]. For patients with drug intolerance, alternative treatment strategies can be applied. For patients with intolerance of steroid induced side effects, a shift to budesonide with 6 mg daily or higher doses of azathioprine (2 mg/kg) may be applicable; or an alternation to Mycophenolate Mofetil (MMF) with 2 g daily and subsequent tapering of steroids is also feasible in conditions of restriction of azathioprine dose due to drug toxicity or side effects [262]. For patients intolerant to azathioprine, MMF with 2 g daily tends to be preferable. 6-MP is another consideration for patients with obvious azathioprine intolerance or other second-line nonsteroidal regimens can also be tried in this case [246].

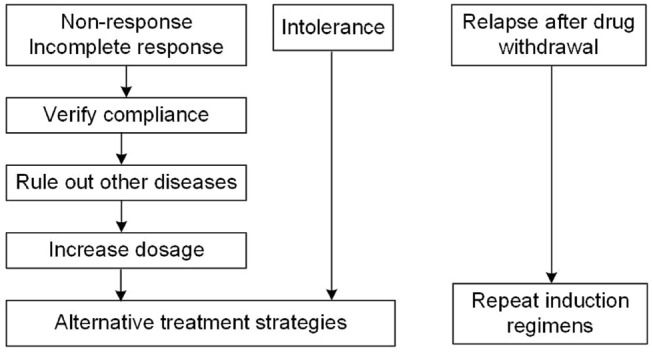

Disease relapse is defined as transaminase levels rising abnormally after remission [263]. As mentioned above, it is very common after treatment withdrawal in AIH patients. In this regard, prednisone and azathioprine doses are required similar to primary induction regimen [264]. The summarized treatment strategy to difficult-to-treat patients is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Treatment strategy to difficult-to-treat patients with AIH

Management to special types of AIH

Acute presentation

Combination therapy with prednisone and azathioprine can result in clinical and laboratory improvement in 68–75% of patients with acute presentations, but the use of prednisone in acute severe-AIH, which is defined as an acute presentation of the illness (less than half year between symptom onset and presentation) and an INR ≥ 1.5 in absence of cirrhosis, remains controversial, because there are not identified and evident benefits [126, 265]. Given the urgency of inflammation and limitation of donor livers, patients should be considered for a trial of prednisolone (≥ 1 mg/kg) at the earliest opportunity [12, 64], although higher levels of bilirubin (> 10 mg/dL) and a MELD score (> 28.5), as well as an elevated INR value (> 2.46) are poor response markers to prednisolone therapy [137, 266]. A retrospective study in 22 Chinese AIH cases found younger age and earlier glucocorticoids administration are beneficial factors for survival [267]. In the midst of treatment, the risk of infections needs the administration of prophylactic antibiotics and antifungal agents, although it remains questionable whether the sepsis impairs the outcome of treated patients [268]. Those who lack improvement of serum bilirubin and MELD score after 2 weeks of prednisolone treatment should consider other therapeutic methods, particularly liver transplantation [151, 269–271]. The initial median dose of 60 vs. 40 mg/day induced comparable response from two clinical trials. This suggests that moderate corticosteroid dosing may be sufficient for treatment. Moreover, a similar number of treated patients developed sepsis in both studies (20 vs. 26%) [221, 266]. Thus, we recommend prednisolone (40 mg daily) could be applied for 2 weeks initially in acute severe-AIH context.

The utility of steroid in flare of chronic AIH remains to be a further investigation. A recent study from the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the (APASL) Research Consortium (AARC) indicates that AIH patients with acute-on-chronic liver failure (ACLF) received treatment with prednisolone (40 mg daily) for 1 month followed by a tapering dose, leading to shorter ICU stay (1.5 vs. 4 days, p < 0.0001) and improved 90-day survival (75 vs. 48.1%, p = 0.02), yet indistinguishable incidence of sepsis in contrast with untreated patients. Patients with advanced age, severe liver disease (MELD > 27), hepatic encephalopathy or fibrosis grade above F3, however, exhibited unfavorable effects to prednisolone therapy [62]. Patients with liver failure should consider liver transplantation.

Decompensated cirrhosis

Prednisolone is appropriate for AIH patients at the decompensated cirrhosis stage. In the corticosteroid-treated group, 62.5% (40/64) patients were reversed to the compensated state [151]. Two Chinese clinical investigations [272, 273] demonstrated the efficacy of initial immunosuppressive treatment in AIH patients with cirrhosis is comparable to that in those without cirrhosis. Cirrhotic patients untreated by immunosuppressive therapy have poor long-term outcomes. Due to impaired liver metabolic function at cirrhosis, prednisolone is preferable for the advanced cirrhosis stage. However, the benefits should be counterbalanced with the high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding and infection, and adjunctive therapies, such as antacids and sympatholytic nonselective beta-blockers should be applied [151, 274]. On the other hand, there are a few studies [275, 276] which have shown liver fibrosis is an independent predictor of non-response to corticosteroids. HCC incidence is another concern for cirrhotic patients. According to statistics, the morbidity for HCC in patients with AIH was 3.06 per 1000 patients, whereas the incidence of HCC in cirrhotic patients at AIH diagnosis was 10.07 per 1000 patients. However, it is still less common than that reported for patients with cirrhosis from hepatitis B, hepatitis C, or primary biliary cholangitis [69, 277]. Thus, ultrasound and tumor markers examinations should be conducted more frequently [70].

Management to special populations

Pregnancy

The maternal complication rate during the pregnancy of mother with AIH is 38%, wherein prematurity is mainly due to withholding from adequate treatment [278]. Therefore, pregnant patients with AIH need to receive continuous treatment to reduce the risk of flare and hepatic decompensation [279]. The use of prednisone is regarded as safe for pregnant female and fetal after a case–control study revealed no association with neonatal cleft lip by US National Birth Defects Prevention [280]. Meanwhile, azathioprine therapy in fertile young adults did not amplify the risk of preterm birth and teratogenicity [248]. Thus, sustained prednisone and/or azathioprine therapy is necessary to reduce the odds of flare and maternal complications. Noticeably, flares are three times more prevalent after delivery [281], which underscore the need for closer monitoring and follow-up of patients.

Children

In the time of diagnosis, more than 50% of children will have evidence of cirrhosis, and the milder forms of disease are scanty. This requires initiation of early treatment following diagnosis [282, 283]. In children, the recommended treatment protocol is similar to that of adults, but a higher steroid dose is warranted due to the more grievous disease course [282, 283]. Starting dose of prednisone at 1–2 mg/kg daily and early administration of azathioprine (1–2 mg/kg daily) is preferred unless contraindications exist [284]. Meanwhile, the treatment duration is more likely to maintain in the long term because the relapse rate is 46% in adults and 80% in children patients after drug withdrawal in satisfaction of the remission criterion for more than 2 years. Furthermore, longstanding biochemical remission is possible in 20% of children with type 1 AIH, but scarce in children with type 2 AIH [100]. In a Turkish study of 47 children, corticosteroid was started at 2 mg/kg daily, then was reduced gradually at 3.6 ± 2.8 months. Maintenance therapy with oral low-dose corticosteroid (5 mg daily) and azathioprine (2–2.5 mg/kg daily) determined that 37 patients (88%) achieved a CR, and 3 patients (9.4%) relapsed at 8, 12, and 48 months [242].

Elderly

Elderly patients are more likely to maintain remission than younger patients after treatment, but treatment in the elderly should be based on the strict criteria due to drug-related side effects, particularly under high dose of prednisone [285]. Benefits from treatment of old patients with mild disease activity are negligible, because 10-year survival has been reported to range from 67 to 90% even without treatment [214]. However, AIH manifests as a fluctuating inflammation which is bound to result in cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Therefore, management of patients with mild disease activity is optional with a dependency on comprehensive balance between all risks and benefits. For those untreated patients, monitoring should be closely carried out to measure transaminases and serum IgG every 3 months [12]. Elderly patients with liver failure or hepatocellular carcinoma should seek for liver transplantation if they have good functional status and no significant comorbidities [286].

Guidance on treatment

The aim of AIH treatment is to achieve complete biochemical and histological resolution to prevent further progression of disease.

All patients with elevated serum aminotransferases, increased IgG levels, enhanced liver stiffness or abnormal histological activity should be considered for treatment.

The initial dose of prednisone should be 30–40 mg daily or 20 mg daily along with 50–150 mg daily of azathioprine.

Periodic DEXA scanning and supplementation of Vitamin D and adequate calcium should be recommended to all patients receiving steroid therapy.

Incorporation with azathioprine is warranted to reduce onset of steroids specific adverse events.

Bone marrow suppression need be noticed in the patients treated with azathioprine, among which the evaluation of TPMT polymorphism is recommended before treatment.

Treatment with prednisone and/or azathioprine therapy is necessary to be maintained during pregnancy.

Because underlined relapse is quite common after treatment discontinuation, most patients need the long-term treatment. Only patients in spontaneous remission may not require therapy but must be closely followed up.

Liver biochemistry, serum IgG, autoantibodies, HCC associated tumor markers, abdominal ultrasonography and transient elastography need to be monitored regularly during the course of treatment.

Liver biopsy might favor the differential diagnoses for AIH patients with non-response.

For patients with drug intolerance, alternative treatment strategies can be applied, such as budesonide, MMF and 6-MP.

Prednisone and azathioprine doses are required similar to primary induction regimen upon the treatment of disease relapse.

Acute severe-AIH patients should be considered for prednisolone (40 mg daily) treatment for 2 weeks initially. The failure to respond would be a cut-off point to withdraw this therapy.

AIH patients with ACLF received treatment with prednisolone (40 mg daily) for 1 month followed by a tapering dose, leading to shorter ICU stay and improved 90-day survival.

The efficacy of initial immunosuppressive treatment in AIH patients with cirrhosis is comparable to that in those without cirrhosis.

A higher starting dose of prednisone at 1–2 mg/kg daily and early administration of azathioprine (1–2 mg/kg daily) are preferred in children with AIH due to the more grievous disease course.

Elderly patients are more likely to maintain remission than younger patients after treatment, but treatment should be based on the strict criteria because of drug-related side effects.

The alternative treatment of AIH

Not all patients respond to conventional treatment with prednisone and azathioprine, and those who do respond may develop side effects related to the treatment or relapse after drug withdrawal. Suboptimal responses in patients with AIH include treatment failure, incomplete response, drug toxicity and relapse after treatment withdrawal [218]. While there is consensus on the ideal first-line therapies for AIH, there is little agreement regarding the treatment of patients with suboptimal responses [12]. The AASLD [66] suggests that failure to conventional therapy should be initially managed with high doses of prednisone before considering other therapies. EASL considers, although the alternative treatments are widely used, RCT trials are lacking. All of them were performed by experience [12]. Tacrolimus and prednisone acquired the highest average rate of improvement in aminotransferases level (94.3%), whereas the average improvement rates in cyclosporine and prednisone, budesonide and mycophenolate, prednisone are 91.3, 85.5, and 78.7%, respectively. The respond rate of the aminotransferases ranges between 78.7 and 94.3% [287].

Budesonide

Budesonide is the second generation of corticosteroid, has an affinity 15 times than that of prednisone. It can be used as first-line and alternative treatment. Oral budesonide has a relatively high concentration in the hepatic cell before elimination, thus obviously reducing the systemic side effect [288]. A decreased liver function presents as lowered albumin, elevated bilirubin, and lowered prothrombin time and results in a higher systemic budesonide concentration. In the presence of portal hypertension and portocaval shunting, as seen in cirrhosis, the systemic concentration of budesonide is even higher. Cirrhotic patients were excluded, because the first pass hepatic extraction of budesonide may be reduced in cirrhosis due to portosystemic shunting [218]. A retrospective study of Iman Zandieh et al. [288] included nine patients of AIH, the indications for budesonide were adverse side effects of prednisone in two patients, noncompliance with prednisone and azathioprine in one patient and intolerance to azathioprine resulting in prednisone dependence in the remaining six patients. Patients were treated in doses ranging from 9 mg daily to 3 mg every other day for 24 weeks to 8 years. Seven of nine patients had a complete response (CR), defined as sustained normalization of the aminotransferase levels. The side effect involves abdominal pain, weight gain, acne, hair loss and Cushing face, only occurred in cirrhotic patients, because the metabolism of liver decrease [289]. In non-cirrhotic patients, moon-face, acne, hirsute are most frequent seen [290]. In a 6-month, prospective, double-blind, randomized, active-controlled, multicenter, phase IIb trial of patients with AIH without evidence of cirrhosis, patients were given budesonide (3 mg, three times daily or twice daily) or prednisone (40 mg/day, tapered to 10 mg/day), with azathioprine at the same time (1–2 mg/kg/day). The primary endpoint (complete biochemical remission, defined as normal serum levels of AST and ALT, without predefined steroid-specific side effects) was achieved in 47/100 patients given budesonide (47.0%) and in 19/103 patients given prednisone (18.4%). For non-cirrhotic patients, the corticosteroid-induced side effect of budesonide obviously rare than pre [291], so the budesonide is suitable for those treatment-naïve, non-cirrhotic, without complex diseases, who are also in high risk of corticosteroid-induced side effect [291–293]. Although budesonide is an attractive treatment strategy for AIH patients without cirrhosis, caution is advised for persistent, vague symptoms which could reflect adrenal insufficiency. Simultaneous intake of other drugs affecting CYP3A4 should be taken into account and should better be avoided [294]. Study shows that the remission rate of budesonide/AZA is higher than that of prednisone/AZA, budesonide in combination with AZA may be appropriate treatment for patients without findings of advanced liver disease [276]. However, budesonide/AZA as frontline therapy in adults with AIH requires additional large-scale studies with a longer duration of follow-up histology and a focus on dose–response [295]. Budesonide is also useful in maintenance [218], but for those who resist or on-respond to pre, budesonide may not be effective, for they share the same mechanism [218, 296].

Mycophenolate mofetil (MMF)