Abstract

Background:

An inflammation-induced imbalance in the kynurenine pathway (KP) has been reported in major depressive disorder (MDD) but the utility of these metabolites as predictive or therapeutic biomarkers of behavioral activation (BA) therapy is unknown.

Methods:

Serum samples were provided by 56 depressed individuals before BA therapy and 29 of these individuals also provided samples after ten weeks of therapy to measure cytokines and KP metabolites. The PROMIS depression scale (PROMIS-D) and the Sheehan Disability Scale were administered weekly and the Beck Depression Inventory was administered pre- and post-therapy. Data were analyzed with linear mixed-effect, general linear, and logistic regression models. The primary outcome for the biomarker analyses was the ratio of kynurenic acid to quinolinic acid (KynA/QA).

Results:

BA decreased depression and disability scores (p’s<0.001, Cohen’s d’s>0.5). KynA/QA significantly increased at post-therapy relative to baseline (p<0.001, d=2.2), an effect driven by a decrease in QA post-therapy (p<0.001, uncorrected, d=3.39). A trend towards a decrease in the ratio of kynurenine to tryptophan (KYN/TRP) was also observed (p=0.054, uncorrected, d=0.78). The change in KynA/QA was nominally associated with the magnitude of change in PROMIS-D scores (p=0.074, Cohen’s f2=0.054). Baseline KynA/QA did not predict response to BA therapy.

Conclusion:

The current findings together with previous research showing that electronconvulsive therapy, escitalopram, and ketamine decrease concentrations of the neurotoxin, QA, raise the possibility that a common therapeutic mechanism underlies diverse forms of anti-depressant treatment but future controlled studies are needed to rest this hypothesis.

1. Introduction

One of the cardinal symptoms of depression is an impaired response to rewarding stimuli, i.e. anhedonia. Behavioral Activation (BA) therapy is a form of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that is designed to shift maladaptive behaviors to increase opportunities for positive reinforcement for the client. The therapist and client work together to develop behavioral activation assignments, i.e. to enhance engagement in key aspects of life that are pleasurable or meaningful (Dimidjian, Barrera, Martell, Munoz, & Lewinsohn, 2011; Martell, Dimidjian, & Herman-Dunn, 2010). BA has been shown to be associated with significant reductions in depressive symptoms, and there is evidence that in the case of severe depression, it may be superior to other forms of therapy (e.g. cognitive therapy) and equivalent to antidepressant medication in efficacy (Butler, Chapman, Forman, & Beck, 2006; Dimidjian et al., 2006). Nevertheless, as in the case of other treatments for depression, 40–50% of patients (Dimidjian et al., 2006) do not respond to BA. Data from the National Health Interview Survey show that approximately nine million Americans receive psychotherapy each year for mental illness (predominantly for depression) at an estimated cost of 7–10 billion dollars (Olfson & Marcus, 2010), and two thirds do not achieve remission after a full course of treatment (DeRubeis et al., 2005; Driessen et al., 2013). Currently, evaluation of who is most/least likely to do well with treatment is based on clinical judgement. Further, evaluation of treatment efficacy is determined primarily by patient self-report. It would be useful to identify predictive or monitoring/therapeutic biomarkers, i.e., biomarkers predictive of treatment outcome or those that change with successful treatment. Such biomarkers could inform personalized medicine approaches as well as future treatment targets, thus potentially helping to reduce healthcare costs and human suffering.

Analytes that quantify an individual’s inflammatory state are natural biomarker candidates for BA because of the tight link between motivational aspects of anhedonia and inflammation. Animal work has demonstrated that experimentally-induced immune system activation produces an altered motivational response that includes anhedonia-like behavior such as reduced sucrose preference (Dantzer, O’Connor, Freund, Johnson, & Kelley, 2008). In humans and non-human primates, administration of cytokines or lipopolysaccharide is associated with decreased striatal dopamine release, disrupted cortico-striatal functional connectivity, blunted striatal responsivity to reward, and symptoms of anhedonia (Capuron et al., 2007; Capuron et al., 2012; Eisenberger et al., 2010; Felger & Treadway, 2017).

Several studies have reported that CBT or cognitive therapy decreases C-reactive protein (CRP) and/or interleukin 6 (IL-6) in depressed patients with medical illnesses or elderly subjects with insomnia (Doering, Cross, Vredevoe, Martinez-Maza, & Cowan, 2007; Irwin et al., 2015; Irwin et al., 2014; Sharpe & Schrieber, 2012; Zabihiyeganeh et al., 2019; Zautra et al., 2008), however this was not observed in a trial of CBT for depressed patients at increased risk of cardiovascular disease (Taylor et al., 2009). Three studies found that CBT reduced IL-6 along with depressive symptoms in patients with primary depression (Gazal et al., 2013; Moore et al., 2013; Moreira et al., 2015) while two other studies reported no change in IL-6 and CRP but decreased expression of inflammatory transcripts such NFKß and TLR-4 (Keri, Szabo, & Kelemen, 2014) and increased IL-10 (Euteneuer et al., 2017) post-treatment. Consistent with the hypothesis that inflammatory markers decrease post-CBT, a course of internet-based CBT for depression was found to decrease the plasma concentrations of several different chemokines although IL-6 and CRP were not measured (Romero-Sanchiz et al., 2020). Partially consistent with these studies, a recent meta-analysis of eight different psycho-social interventions across a range of different diseases concluded that on average these interventions decrease markers of inflammation and that the evidence is most reliable for CBT or multiple-component interventions (Shields, Spahr, & Slavich, 2020). In contrast, minimal attention has been paid to treatment response biomarkers (i.e., biomarkers that predict symptom reduction).

An under-appreciated consequence of inflammatory processes observed in depression is the immune-mediated activation of the kynurenine pathway (KP) (Savitz, 2020). Several inflammatory mediators increase the conversion of tryptophan (TRP) to kynurenine, which is then further metabolized down two principal pathways producing several neuroactive metabolites (Figure S1). In one branch, kynurenine is converted to the NMDA receptor antagonist, kynurenic acid (KynA). In the other principal branch, kynurenine is ultimately metabolized into the neurotoxic NMDA receptor agonist, quinolinic acid (QA) and the energy source, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+). Because activated immune cells require energy, kynurenine is preferentially converted into QA and NAD+ under inflammatory conditions (O’Connor et al., 2009; Zunszain et al., 2012). Nevertheless, because of their neuromodulatory properties activation of the KP is not simply a surrogate marker of inflammation. It also has additional mechanistic effects, modulating a range of physiological processes, including glutamatergic and dopaminergic neurotransmission (Savitz, 2020). The literature generally shows a decrease in KynA and/or an increase in QA in depressed samples relative to controls (Bay-Richter et al., 2015; Doolin et al., 2018; Myint et al., 2007; Savitz, Drevets, Smith, et al., 2015; Savitz, Drevets, Wurfel, et al., 2015; Wurfel et al., 2017) and a lower ratio of KynA to QA is associated with greater symptoms of anhedonia (Savitz, Drevets, Wurfel, et al., 2015). These data raise the possibility that excess QA leads to excitotoxicity, dendritic atrophy, and impaired neuroplasticity (Savitz, 2020). Like many other anti-depressant treatments, psychotherapy has been postulated to enhance neuroplasticity thereby altering information processing and learning (Castren, 2013; Sharpley, 2010). Thus, in theory, CBT interventions could exert their therapeutic effects at least in part via modulation of the KP, and the balance between KynA and QA at baseline could conceivably predict treatment efficacy. However, to our knowledge this hypothesis has never been tested.

The current work therefore had two principal aims. The first aim was to determine the effects of BA on serum levels of KP metabolites and their association with an improvement in psychological symptoms. The second main aim was to determine whether KP metabolites predicted treatment response. Based on our prior work in independent samples (Meier et al., 2016; Savitz, Drevets, Wurfel, et al., 2015; Young et al., 2016), the primary outcome variable was KynA/QA. Other KP metabolites and inflammatory markers were secondary and exploratory outcomes. The hypotheses and analysis plan were pre-registered in the Open Science Framework on 11/14/2019 under the title, “Inflammatory Mechanisms and Predictors of Response to Behavioral Activation Therapy for Depression” (https://osf.io/nzf6v).

2. METHODS

Informed Consent

Written, informed consent was obtained from all participants and the study was approved by the Western Institutional Review Board (WIRB). The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. Participants were compensated for their time completing assessments but were not compensated for time spent completing therapy.

Financial Disclosures

Dr. Paulus has received royalties for an article about methamphetamine use disorder from UpToDate. The other authors have no disclosures.

Study Design

The present study combined data collected as part of two larger clinical trials focused on identifying whether neuroimaging and behavioral indices related to approach-avoidance behavior were predictive of treatment response in (1) a non-randomized, unblinded clinical trial in which all enrolled participants had clinically-significant depression and completed BA therapy (ClinicalTrials.gov: #NCT02602340) and (2) a randomized, unblinded clinical trial in which enrolled participants had clinically-significant generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) symptoms and were randomized to complete either BA or exposure-based therapy (Santiago et al., 2020) (ClinicalTrials.gov: # NCT02807480). From the latter study, we only included individuals in the present analysis if they reported elevated depression symptoms as per the first study (i.e. Patient Health Questionnaire-9 [PHQ-9] scores > 9) and if they were randomized to complete BA rather than exposure-based therapy. Other than the symptom severity requirements relating to GAD and depression, the inclusion/exclusion criteria were identical across the two studies. For both studies, participants were recruited from outpatient mental health clinics and the general community through electronic and print advertisements. All participants completed baseline clinical, behavioral, and neurobiological assessments before and after completion of 10 weeks of group-based BA therapy, and then repeated clinical, behavioral, and neurobiological assessments.

Participants

Fifty-six individuals aged 18–55 years were included in the two studies. Participants enrolled in the study focused on depression were required to have clinically-significant depression symptoms, i.e. a score >9 on the PHQ-9. While meeting DSM criteria for major depressive disorder (MDD) was not required for inclusion, 93.4% met criteria for lifetime MDD. Diagnostic criteria were assessed using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI 7.0) (D. V. Sheehan et al., 1998), administered by trained masters or nurse-level research assistants, and supervised by board-certified psychiatrists and licensed clinical psychologists. Participants enrolled in the study focused on GAD were required to have clinically-significant GAD symptoms, i.e., a score >10 on the GAD-7 (and required to score >9 on the PHQ-9 to be included in present analysis). Exclusion criteria for both studies included: (1) suicidal ideation with current intent or plan; (2) history of substance use disorder in the past 6 months; (3) meeting diagnostic criteria for psychotic, bipolar, obsessive-compulsive, or eating disorders; (4) moderate to severe traumatic brain injury or other neurocognitive disorder; (5) severe or unstable medical conditions, including inflammatory and autoimmune disorders (except hypothyroidism); (6) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contraindications, such as metal or metallic devices in the body; (7) non-correctable vision or hearing problems; and (8) current use of antipsychotics or mood stabilizers. Depression or GAD was required to be considered the primary area of concern, though comorbid disorders (e.g., anxiety disorders, PTSD) were not excluded (see Table 1 for prevalence of these comorbidities). Participants reporting current use of antidepressants (n=14) were included as long as the dose had been stable for six weeks prior to enrollment. Participants were excluded if they were concurrently engaged in psychosocial treatments specifically targeting depression or related symptoms. Individuals receiving psychosocial treatments for other symptoms, or treatments that were not specifically targeting depressive symptoms (e.g., ongoing support groups, couples’ therapy) were not excluded. Inclusion/exclusion criteria were designed to decrease potential confounders while also supporting generalizability of results to patient populations in the community.

Table 1.

Demographical and Clinical Characteristics of the Participants.

| Age (mean (SD)) | 33.93 (11.78) |

| Sex = Male (%) | 23 (41.1) |

| Educational attainment (%) | |

| Less than high school education | 2 (3.6) |

| High school or GED | 10 (17.9) |

| Some college, no degree | 20 (35.7) |

| Associate’s degree | 5 (7.2) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 17 (30.4) |

| Master’s degree | 2 (3.6) |

| Doctoral degree | 1 (1.8) |

| Race (%) | |

| Asian American | 1 (1.8) |

| Black or African American | 11 (19.6) |

| Native American | 1 (1.8) |

| Other | 1 (1.8) |

| White | 42 (75.0) |

| Clinical | |

| Baseline PROMIS Depression (mean (SD)) | 61.16 (5.63) |

| Baseline BDI (mean (SD)) | 21.18 (7.94) |

| Baseline SDS (mean (SD)) | 12.80 (6.42) |

| MDD, current episode N (%) | 32 (57.1) |

| MDD lifetime N (%) | 53 (94.6) |

| Panic disorder current N (%) | 2 (3.6) |

| Agoraphobia current N (%) | 10 (17.9) |

| Social anxiety disorder N (%) | 13 (23.2) |

| PTSD current N (%) | 2 (3.6) |

| GAD current N (%) | 28 (50.0) |

| Medications | |

| Antidepressants N (%) | 14 (25.0) |

| SNRI N (%) | 1 (1.8) |

| Atypical N (%) | 7 (12.5) |

| SSRI N (%) | 10 (17.9) |

| Benzodiazepines N (%) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mood Stabilizer N (%) | 0 (0.0) |

GAD = generalized anxiety disorder; PTSD = post-traumatic stress disorder; BDI = Beck Depression Inventory; SDS = Sheehan Disability Scale; SNRI = serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor

Intervention

BA consisted of ten weekly, 90-minute sessions delivered in a group format. Participants were included in one of seven different therapy groups, each of which had a total of 6–10 participants. A structured, group-based BA manual was developed by co-authors RLA and CM (with edits and revisions provided by ANC), informed by previously published BA treatment guides (Martell et al., 2010). Each participant was provided BA self-help materials (Addis & Martell, 2004) to accompany the intervention, as well as “homework” worksheets for monitoring of one’s activities and associated mood (including during behavioral activation exercises) and for helping implement various BA concepts (e.g., monitoring of antecedents, behaviors, and consequences [“ABC”]). Brief descriptions of each intervention are provided below. Fidelity was confirmed via an independent rater for randomly selected sessions (24 of the 70 sessions, or 34%). Further detail concerning the delivery of the interventions, training of therapists, and fidelity ratings are provided in the supplement.

Psychometric Measures

All participants were asked to complete self-report measures at baseline (within six weeks prior to initiating therapy; mean 2.5 weeks), weekly throughout the intervention, and at post-treatment (within six weeks after completing session 10; mean 2.6 weeks). Current analyses focused on clinical assessments administered pre- and post-treatment and weekly during completion of BA and thus are described herein. The National Institute of Health Patient Reported Outcome Information System (PROMIS; (Broderick, DeWitt, Rothrock, Crane, & Forrest, 2013; Cella et al., 2010)) measure of depressive symptoms (PROMIS-D) and the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS; (D.V. Sheehan, Harnett-Sheehan, & Raj, 1996)) were administered at all time points. The SDS measures functional impairment in three major life domains: work, social life/leisure activities, and family life/home responsibilities. The Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II (Aaron T Beck, Steer, Ball, & Ranieri, 1996)), a widely-used 21-item self-report scale was administered at pre- and post-treatment.

Immunophenotyping

A blood sample was obtained from each subject pre- and post-therapy at similar time points as self-report measures. Only individuals who completed BA were asked to provide a post-treatment blood sample. Blood samples were drawn by venipuncture between 7am and 11am. Serum samples were collected with BD Vacutainer serum tubes, processed according to the standard BD Vacutainer protocol, and stored at −80 C.

IL-6, TNF, and IFNγ were quantified blind to visit with a V-PLEX Panel from Meso Scale Diagnostics with a lowest level of quantification (LLOQ) of 0.07 pg/mL, 0.02 pg/mL, and 0.12 pg/mL, respectively. Samples were run in duplicate with intra-assay coefficients of variation (CV) of 7.28%, 2.15%, and 4.43%, respectively. IL1-RA was measured with a solid-state ELISA (R&D Systems) with an LLOQ of 31.2 pg/mL and a CV of 2.44%. No samples were below detectable limit. Concentrations of tryptophan (TRP), kynurenine, kynurenic acid (KynA), 3-hydroxykynurenine (3HK), and quinolinic acid (QA) were measured blind to visit by Charles River Laboratories. The serum metabolite concentrations were determined by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) with tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS) detection using their standard protocols. The lowest level of quantification and intra-assay percentage of coefficient of variation for each of the kynurenine pathway metabolites were as follows: TRP: 3 μM, 1.4%; kynurenine: 0.225 μM, 1.6%; KynA: 7.5 nM, 6.6%; 3HK: 5 nM, 3.9%, and QA: 50 nM and 8.6%. Five KynA samples were below detectible limit (< LLOQ). These concentrations were imputed as 90% of LLOQ.

Statistics

For hypotheses that involved repeated measures (Hypotheses 1–4), we used linear mixed-effects models with therapy groups and subjects nested within each therapy group as random effects, plus first-order autocorrelation (AR1) correlation structure to capture within-group subject dependency (LMM), and estimated parameters using restricted maximum likelihood estimation (REML) method. With our sample size, REML was shown to have coverage probability at or above 0.95 nominal level (Finch, 2017). For analyses with binary outcomes (Hypothesis 5), general linear mixed models (GLMM) were implemented with the post-intervention measure as the outcome and the pre-intervention measure as an independent variable (fixed-effect) and therapy groups as a random effect. For all analyses, age, sex, BMI, and their possible combinations were tested as covariates using Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) and the model with the minimum BIC score was chosen.

Hypothesis 1:

BA will decrease symptoms of depression and disability.

The primary outcome was the PROMIS-D and the secondary outcomes were the SDS and BDI. Weekly measures of PROMIS-D and SDS scores were analyzed by LMM with time as a fixed-effect of interest (random effects as described above). BDI scores were collected at pre- and post-BA and were analyzed by LMM using the same fixed and random effects with two levels in the time variable. For PROMIS-D, p=0.05 was considered significant. For SDS and BDI, p=0.025 was considered significant. No covariates were selected for PROMIS-D and SDS models based on BIC. For BDI, sex was included as a covariate.

Hypothesis 2:

BA will result in an increase in protective kynurenine metabolites and/or a reduction in inflammatory metabolites from baseline to post-treatment.

KP metabolites and inflammatory markers pre- and post-BA were analyzed by LMM with two levels in the time variable as a fixed-effect of interest (random effects as described above). For KynA/QA, p=0.05 was considered significant and no covariates were included based on BIC. For all other markers the false positive rate (FDR) was controlled at 5% level using Benjamini-Hochberg’s procedure.

Hypothesis 3:

An improvement in symptoms of depression with BA will be associated with the change in KP metabolites and inflammatory markers.

PROMIS-D, BDI, and SDS scores were used as response variables in LMMs using (a) post-vs-pre-BA percent changes in metabolite levels, (b) time, (c) changes in metabolite by time interactions and (d) where applicable, age, sex, and/or BMI as fixed-effects, and random effects as decribed above. For KynA/QA, p=0.05 was considered significant. For all other markers the false positive rate (FDR) was controlled at 5% level using Benjamini-Hochberg’s procedure.

Hypothesis 4:

Reduced serum concentrations of protective KP metabolites and/or elevated inflammatory metabolites at baseline will predict the efficacy of BA.

PROMIS-D, BDI, and SDS scores were used as response variables in LMMs using (a) pre-BA metabolite levels, (b) time, (c) pre-BA metabolite by time interactions and (d) where applicable, age, sex, and/or BMI as fixed-effects and random effects as decribed above. For KynA/QA, p=0.05 was considered significant. For all other markers the false positive rate (FDR) was controlled at 5% level using Benjamini-Hochberg’s procedure.

Hypothesis 5:

Reduced serum concentrations of protective KP metabolites and/or elevated inflammatory metabolites at baseline will predict lack of response to BA for depression. Response was defined as a reliable change index (RCI) from baseline in the PROMIS-D surpassing 1.96 (Zahra & Hedge, 2010). The RCI was calculated using the formula sqrt(2*(SEPROMIS-D^2)), where SEPROMIS-D was defined as (SD(PROMIS-Dtime1)*sqrt(1-RELPROMIS-D). The test-retest reliability of PROMIS-D (RELPROMIS-D = 0.71) was identified by averaging the results of previous studies (Bartlett et al., 2015; Bernstein et al., 2018; Deyo et al., 2015; Hitchon et al., 2019; Pilkonis et al., 2014; Yount et al., 2016). The test-retest reliability for the BDI-II was based on psychometric data provided in the corresponding manual (A.T. Beck, Steer, & Brown, 1996), i.e. RELBDI=0.92. Response status based on RCI was used as the binary outcome variable in a GLMM logistic regression, with the normalized baseline KP metabolite or cytokine concentration as the predictor variable and inclusion of covariates determined via BIC as fixed effects, and therapy groups as a random effect. For KynA/QA, p=0.05 was considered significant. For all other markers an FDR correction was employed.

3. RESULTS

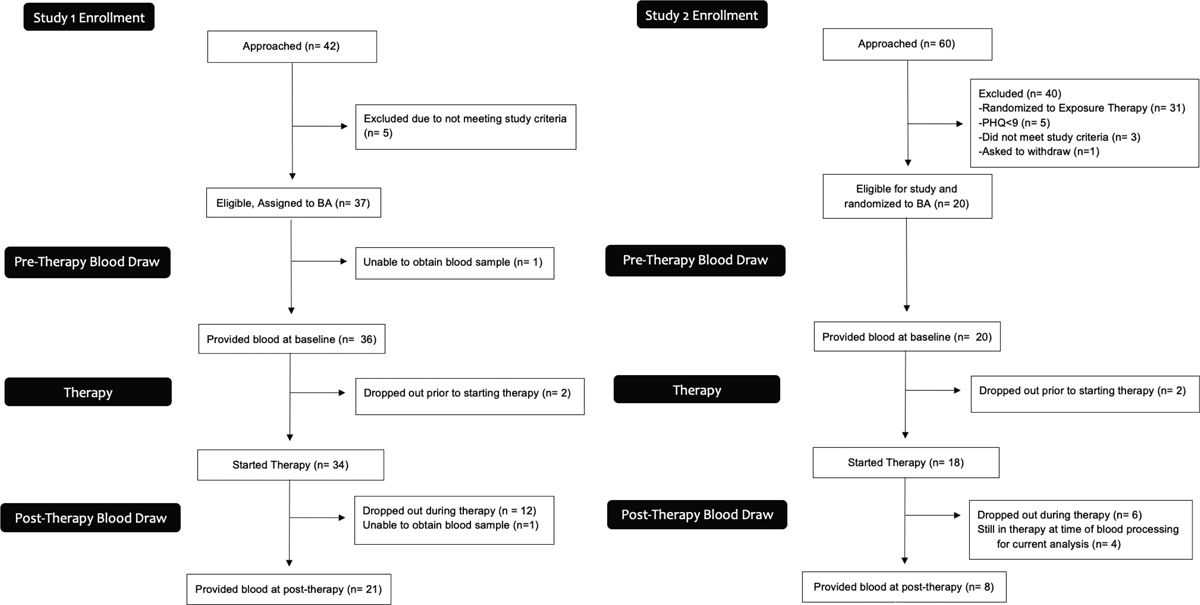

As part of the larger clinical study, blood samples were available for 56 individuals prior to beginning BA, and of the 33 individuals that completed therapy, 29 had blood samples collected (Figure 1). Eleven out of 33 subjects (33%) were classified as responders based on the RCI for PROMIS-D and 18/33 (55%) based on the BDI RCI. Inter-correlations between the biomarkers and clinical-rating scales for both pre and post-therapy visits are shown in Figure S2. As expected, Kyn/TRP a surrogate marker of KP activation was significantly correlated with QA at both the pre- (r=0.78, p<0.001) and post-therapy (r=0.58, p=0.001) visits. Similarly, QA and 3-HK were significantly correlated at both pre- (r=0.57, p<0.001) and post-therapy (r=0.54, p=0.002) visits. IL1-RA, but not TNF and IL-6, was significantly correlated with QA at the pre-therapy (r=0.28, p=0.040) but not the post-therapy visit (r=0.29, p=0.121). SDS scores but not depression scores were inversely associated with KYN/TRP (r=−0.36, p=0.007) and QA (r=−0.30, p=0.025) levels at baseline but not post-therapy (KYN/TRP: r=−0.23, p=0.238; QA: r=−0.26, p=0.167).

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram for each sub-study showing participants approached/enrolled as of 02/02/2018, with added information concerning the number who completed the blood draw and reasons for not completing the blood draw.

Hypothesis 1:

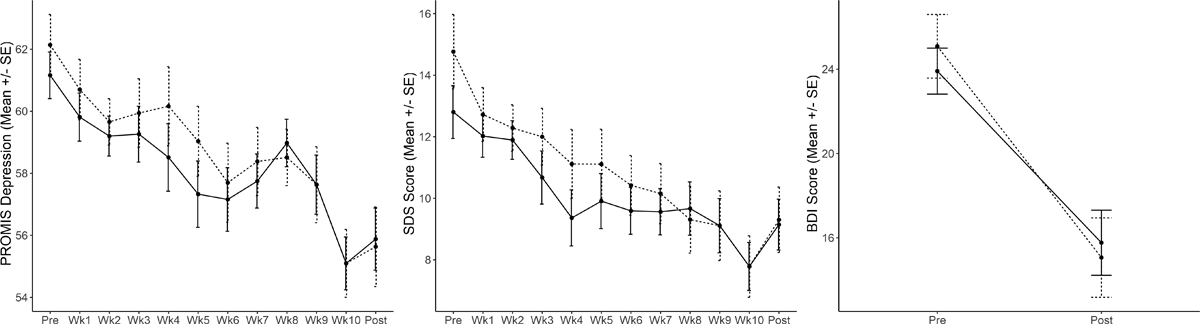

There was a significant main effect of time with decreases in PROMIS-D (F11, 352 = 4.1, p<0.001, Cohen’s d=0.62 for pre-post changes), BDI (F1, 33 = 22.1, p<0.001, d=1.64) and SDS (F11, 354 = 3.2, p<0.001, d=0.52) scores at the post-therapy visit (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mean change in PROMIS-Depression (left panel), Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS; middle panel), and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI, right panel) scores (y-axis) over the 10-week course of BA therapy (x-axis). The error bars represent the standard error of the means. Solid and dashed lines represent all participants (n = 56) and particpants who completed at least 7 BA therapy sessions (n = 34), respectively.

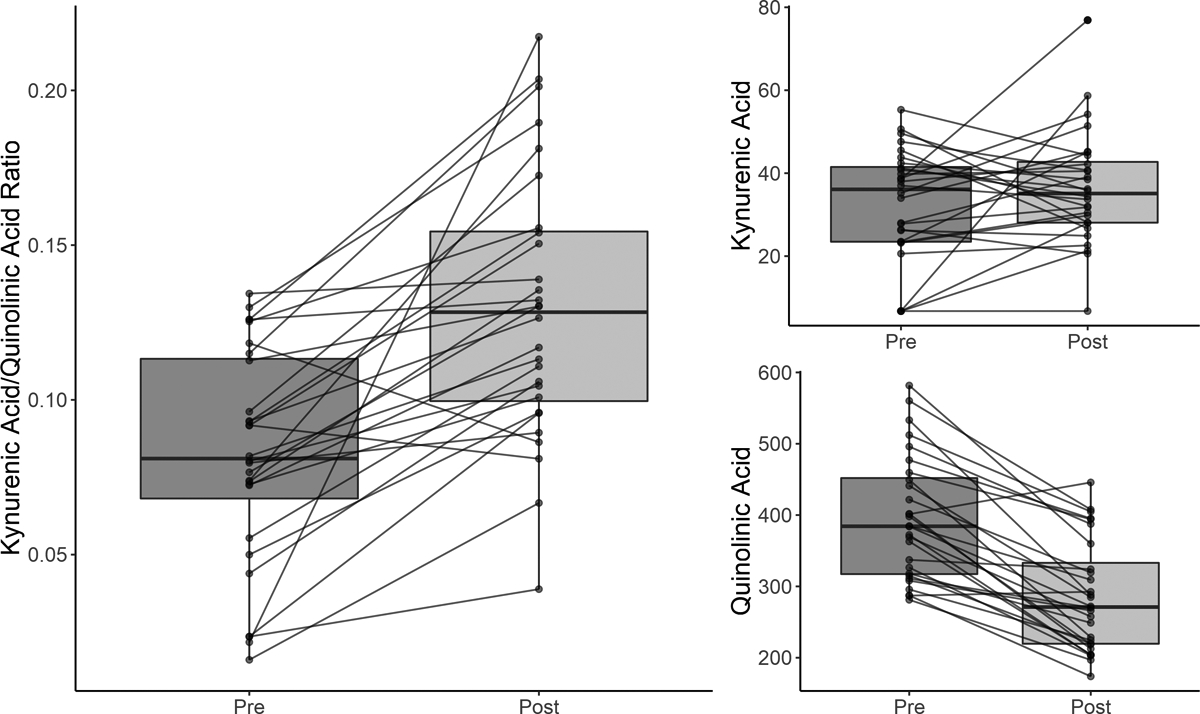

Hypothesis 2:

There was a significant increase in KynA/QA post therapy relative to baseline (F1, 27 = 32.9, p<0.001, d=2.2, Figure 3). Secondary analyses showed that the effect was driven by a decrease in QA post therapy (F1, 27 = 77.6, Benjamini-Hochberg corrected p<0.001, d=3.39). A nominal decrease over time was also observed for KYN/TRP (F1, 27 = 4.1, p=0.054, uncorrected, Benjamini-Hochberg corrected p=0.322, d=0.78). There were no significant changes in cytokine concentrations.

Figure 3.

Box and whisker plots showing the distribution of kynurenic acid to quinolinic acid ratios (KynA/QA) (left panel), KynA (top right panel), and QA (bottom right panel) concentrations pre-therapy and post-therapy. The solid line represents the median serum concentration. The boxes above and below the median represent the 50th-75th percentiles and the 25–50th percentiles of the scores, respectively. The vertical line (whisker) indicates the distribution of scores within 1.5 times of the interquartile range. The change in concentration pre-therapy to post-therapy is shown for each individual participant with a solid line.

Hypothesis 3:

The magnitude of the increase in KynA/QA post-therapy was nominally associated with the corresponding decrease in PROMIS-D (F11,218=1.7, p=0.074, Cohen’s f2 = 0.054) but not BDI (F1,26=0.4, p=0.552) or SDS (F11,220=1.0, p=0.450) scores. Secondary analyses indicated that a greater decrease in IL-1RA post-therapy was nominally associated with a greater reduction in PROMIS-D (F11,218=1.8, p=0.057, uncorrected, Cohen’s f2=0.082), but not BDI (F1,26=1.4, p=0.251, uncorrected) or SDS (F11,220=0.3, p=0.976, uncorrected) scores.

Hypothesis 4:

Baseline levels of KynA/QA did not significantly predict the change in PROMIS-D (F11, 330=0.9, p=0.540, uncorrected), BDI (F1, 31=0.1, p=0.733, uncorrected), or SDS (F11, 332=0.6, p=0.866, uncorrected) scores over time. No individual KP metabolites or cytokines predicted the magnitude of the change in clinical-scale scores pre- vs. post-therapy in secondary analyses.

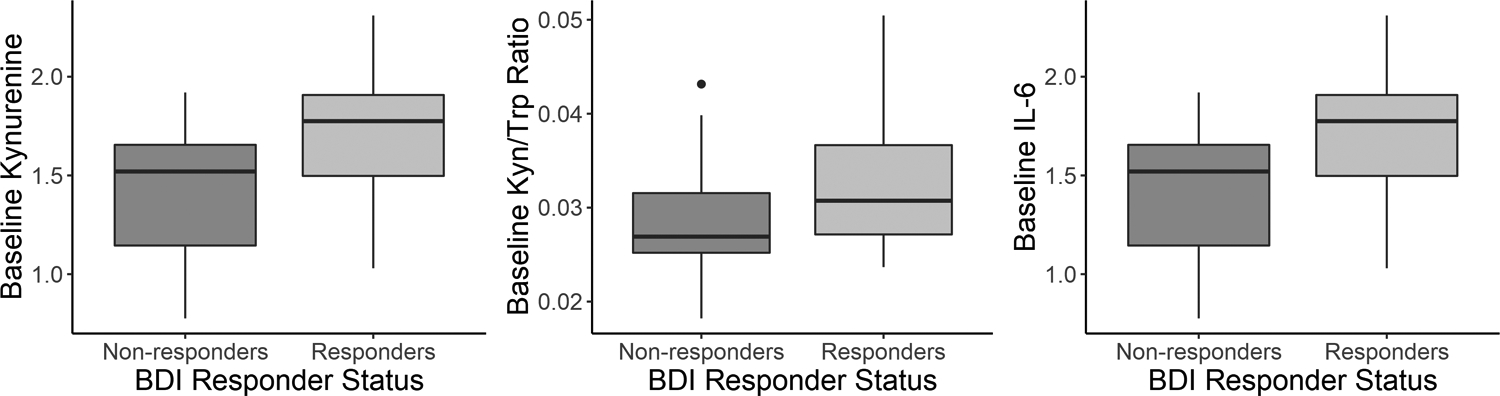

Hypothesis 5:

Baseline KynA/QA did not predict response status to BA as measured by PROMIS Depression or BDI. Exploratory analyses showed that treatment responders as defined by the BDI had nominally higher baseline concentrations of KYN (OR=52.36, 95%CI: 0.89–3089, p=0.057, uncorrected), Kyn/Trp (OR=8.80, 95%CI: 1.15–67.22, p=0.036, uncorrected), and IL-6 (OR=4.05, 95%CI: 1.13–14.56, p=0.032, uncorrected) compared to non-responders (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Box and whisker plots showing the difference in baseline (pre-therapy) concentrations of kynurenine (left panel), kynurenine to tryptophan (Kyn/Trp, middle panel), and interleukin-6 (IL-6, right panel) between responders and non-responders to therapy defined on the basis of the reliable change index (RCI) for the BDI.

4. DISCUSSION

This study aimed to determine the effects of BA on serum levels of KP metabolites and their association with an improvement in depressive symptoms. First, consistent with our hypothesis, there was a highly significant increase in the primary outcome, KynA/QA, at the post-therapy visit compared to baseline. Second, the increase in KynA/QA was nominally associated with the magnitude of the reduction in PROMIS-D (but not BDI) scores over the course of therapy. The increase in KynA/QA at the post-therapy visit was driven by a decrease in QA. QA is thought to produce neurotoxic effects via multiple different mechanisms, including NMDA receptor-induced excitotoxicity, the generation of reactive oxygen species, disruption of the blood brain barrier, destabilization of the cellular cytoskeleton, increasing tau phosphorylation, disruption of autophagy, and the induction of a proinflammatory response in astrocytes (Guillemin, 2012). Under inflammatory conditions, metabolism of KYN down the QA pathway is favored because QA is metabolized into NAD+, a cellular energy source needed by activated immune cells (Savitz, 2020). Consistent with this model, QA was positively correlated – albeit modestly - with IL-1RA at baseline. Similarly, the first step of the KP, i.e. the conversion of TRP to KYN by the enzyme, indoleamine dioxygenase (IDO) is also increased by inflammation. KYN/TRP is considered to be a surrogate marker of IDO activity and was modestly correlated with TNF at baseline. Thus, the post-therapy decreases in QA and KYN/TRP may be due to a partial resolution of inflammation in participants receiving therapy.

In line with the inflammatory model of depression, decreases in KynA and/or increases in peripheral QA concentrations are commonly reported in depressed populations compared with healthy controls (Savitz, 2020). Further, post-treatment shifts in the metabolic balance between the KynA and QA branches of the KP have been reported in three different conventional treatments for depression as well as exercise, which also has anti-depressant effects (Mura, Moro, Patten, & Carta, 2014). First, escitalopram increased circulating concentrations of KynA/QA, an effect driven by a decrease in QA (Halaris et al., 2015). There were no treatment-associated changes in seven inflammatory cytokines as well as CRP. Second, three studies have demonstrated that response to ketamine is associated with either an increase in KynA or a decrease in QA. Relative to non-responders, ketamine responders displayed increased KynA as well as KynA/KYN from 24 hours after the first infusion until at least two weeks after the initiation of treatment (Zhou et al., 2018). Similarly, ketamine treatment increased KynA (but not KynA/QA) concentrations and decreased QA/Kyn (but not QA) concentrations within three days of infusion in patients with treatment-resistant bipolar disorder (Kadriu et al., 2019). In a third study, ketamine was shown to reduce QA production by microglia in mice and further, in depressed patients, a reduction in QA after treatment was associated with an improvement in depressive symptoms (Verdonk et al., 2019). Third, two weeks of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) resulted in a significant increase in plasma KynA/QA, an effect driven by a decrease in QA (Schwieler et al., 2016). Similar to the current study, ECT had no effect on the concentrations of four different cytokines. Fourth, endurance exercise increased plasma concentrations of KynA and KynA/QA in healthy volunteers (Schlittler et al., 2016). The above data, taken together with the results of the current study, raise the possibility that the KP may be a common mechanistic pathway underlying the therapeutic efficacy of diverse anti-depressant treatments.

This common pathway may involve neuroplasticity, i.e. the activity-dependent modification of the structure and function of neural circuitry. There is a salient overlap in the molecular changes induced by anti-depressant treatments and the mechanisms of neuroplasticity (Pittenger & Duman, 2008). These molecular mechanisms include alterations in glutamatergic neurotransmission via changes to NMDA receptors which are essential mediators of activity-dependent synaptic plasticity (Paoletti, Bellone, & Zhou, 2013). Conceivably, the balance between the NMDA receptor antagonist, KynA, and the NMDA receptor agonist, QA, may modulate synaptic plasticity (Savitz, 2020). If a normalization of the KP is a therapeutic mechanism common to diverse therapies, the KP could be a potential treatment target. Indeed several treatments targeting the KP are under development (Savitz, 2020). Further, identifying psychotherapeutic interventions that have maximal impact on the KP may help to increase efficacy of BA. For instance, identifying specific BA exercises that more meaningfully engage the reward circuitry and impact QA (e.g., physical versus social activities, etc.) or identifying strategies to optimize the impact of BA exercises on neuroplasticity (i.e., enhance the consolidation of reward learning through post-activity processing) could theoretically help to fine-tune the psychotherapeutic intervention. Conceivably, synergistic effects could also be obtained by combining therapies that target the KP, for instance combining BA with one or more of the treatment modalities mentioned above.

There were three other secondary findings of interest. First, baseline KynA/QA did not significantly predict reponse to BA as predicted (hypotheses 4 and 5). The absence of a significant therapeutic response biomarker for BA in this study is unfortunately consistent with much of the literature which shows a robust effect of several psychological interventions on immune parameters (Shields et al., 2020) but few instances in which these baseline immune parameters are reported to be predictive of treatment outcome. Second, the magnitude of the decrease in IL-1RA concentrations post-therapy was nominally associated with the magnitude of the decrease in PROMIS-D (but not BDI) scores (hypothesis 3) although this result was not significant after FDR correction. IL-1RA (as well as several other cytokines) were reported to be decreased after 12 weeks of psychotherapy although the decrease in IL-1RA was not related to the improvement in symptoms (Dahl et al., 2016). Because IL-1RA inhibits the activities of IL-1β, IL-1RA is generally increased by IL-1β and is therefore usually considered to be a surrogate marker of IL-1β concentration (Bartfai et al., 2007). IL-1β is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that has been reported to be elevated in some MDD populations (Howren, Lamkin, & Suls, 2009) but whose concentration in the blood is generally too low to measure reliabily. Given our hypothesis that changes in neuroplasticity may underlie the anti-depressant effects of various therapeutic interventions, it is potentially noteworthy that IL-1β has been shown to modulate neuroplasticity in several animal models (Lynch, 2015; Patterson, 2015). It is unclear why the PROMIS-D would be more sensitive to the change in IL-1RA than the BDI but one possibility is that the two scales are weighted differently in terms of the symptoms that they measure. Alternatively, because the PROMIS-D was administered at every session whereas that BDI was only administered pre-and-post therapy, differences in the statistical models may have accounted for the discrepant results. Another secondary finding was that higher baseline concentrations of Kyn/TRP and IL-6 were present in responders vs. non-responders defined by the BDI (hypothesis 5). It is unclear if this result is robust since it did not survive FDR correction and it was not observed when response vs. non-response was defined on the basis of the PROMIS-D or when response was considered as a continuous variable (hypothesis 4). Nevertheless, there are isolated reports in the literature of higher concentrations of IL-6 in responders vs. non-responders to SSRIs (Yoshimura et al., 2013) and ECT (Kruse et al., 2018) and therefore these results may be worthwhile following up in future studies.

The current study has several limitations. First, since this was a naturalistic study without a placebo control group we cannot determine if the reduction in QA is consequence of BA, per se, or whether it is due to reductions in depressive symptoms due to non-specific factors such as placebo-effects, natural fluctuations in mood, or possible indirect effects of BA on the KP such as changes in diet, exercise or sleep. Second, a dedicated anhedonia scale was not included. Given the close link between inflammation and anhedonia, it is possible that anhedonic symptoms would be most sensitive to changes in inflammation. Third, KP metabolites and inflammatory cytokines were measured in serum and not the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Nevertheless, KYN and TRP are known to cross the blood brain barrier and there is some evidence that QA also has this capacity (Heyes & Morrison, 1997). This may explain the significant correlations between KYN/TRP (r=0.77), and QA (r=0.55) concentrations in the blood and CSF reported in a recent study of depressed patients (Haroon et al., 2020). Fourth, although there are known sex differences in immune function (Klein & Flanagan, 2016) and the KP (de Bie, Lim, & Guillemin, 2016; Meier et al., 2018), this study was not adequately powered to detect such effects. Fifth, given that we focused our analysis on one pre-registered primary outcome (KYNA/QA), this variable was not corrected for multiple comparisons (though secondary outcomes were). Larger studies could be useful for performing confirmatory analyses and exploratory investigations of a wider range of immune markers. Lastly, BA was conducted via a manualized, group therapy. While the level of symptom decrease observed here is similar to what has been reported in previous studies delivering BA as individual therapy (Dimidjian et al., 2006), the generalizability of findings in different formats cannot be determined.

In sum, the principal finding of the current study was a significant post-therapy increase in the neuroprotective index, KynA/QA that was driven by a robust decrease in circulating QA concentrations. This result is consistent with prior reports of escitalopram, ketamine, ECT, and exercise-induced increases in KynA/QA, and raises the possibility that changes in the KP may contribute to the efficacy of several different treatments for depression. Future controlled studies are needed to test this hypothesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the research participants and wish to acknowledge the contributions of Brenda Davis, Debbie Neal, Chibing Tan, and Ashlee Rempel from the laboratory of TKT at the University of Oklahoma Integrative Immunology Center towards the transport, processing and handling of all blood samples as well as the measurement of cytokines. We thank Dr. Ruth Hermann-Dunn for her work in conducting fidelity ratings for therapy sessions.

Funding

This work was supported by the William K. Warren Foundation, the National Institute of Mental Health (K23MH108707; R21MH113871), and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (P20GM121312).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Paulus has received royalties for an article about methamphetamine use disorder from UpToDate. The other authors have no disclosures.

Ethics Statement

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

REFERENCES

- Addis ME, & Martell CR (2004). Overcoming depression one step at a time: The new behavioral activation approach to getting your life back: New Harbinger Publications, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Bartfai T, Sanchez-Alavez M, Andell-Jonsson S, Schultzberg M, Vezzani A, Danielsson E, & Conti B (2007). Interleukin-1 system in CNS stress: seizures, fever, and neurotrauma. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1113, 173–177. doi: 10.1196/annals.1391.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett SJ, Orbai AM, Duncan T, DeLeon E, Ruffing V, Clegg-Smith K, & Bingham CO 3rd. (2015). Reliability and Validity of Selected PROMIS Measures in People with Rheumatoid Arthritis. PLoS One, 10(9), e0138543. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bay-Richter C, Linderholm KR, Lim CK, Samuelsson M, Traskman-Bendz L, Guillemin GJ, … Brundin L (2015). A role for inflammatory metabolites as modulators of the glutamate N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor in depression and suicidality. Brain Behavior, and Immunity, 43, 110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.07.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, Ball R, & Ranieri WF (1996). Comparison of Beck Depression Inventories-IA and-II in psychiatric outpatients. Journal of personality assessment, 67(3), 588–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Beck Depression Inventory Manual, 2nd Ed. San Antonio: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein CN, Zhang L, Lix LM, Graff LA, Walker JR, Fisk JD, … Managing the Effects of Immune-mediated Inflammatory, D. (2018). The Validity and Reliability of Screening Measures for Depression and Anxiety Disorders in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflammatory Bowel Disease, 24(9), 1867–1875. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izy068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broderick JE, DeWitt EM, Rothrock N, Crane PK, & Forrest CB (2013). Advances in patient-reported outcomes: The NIH PROMIS measures. eGEMS, 1(1), 1015. doi: 10.13063/2327-9214.1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler AC, Chapman JE, Forman EM, & Beck AT (2006). The empirical status of cognitive-behavioral therapy: a review of meta-analyses. Clinical psychology review, 26(1), 17–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capuron L, Pagnoni G, Demetrashvili MF, Lawson DH, Fornwalt FB, Woolwine B, … Miller AH (2007). Basal ganglia hypermetabolism and symptoms of fatigue during interferon-alpha therapy. Neuropsychopharmacology, 32(11), 2384–2392. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301362 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capuron L, Pagnoni G, Drake DF, Woolwine BJ, Spivey JR, Crowe RJ, … Miller AH (2012). Dopaminergic mechanisms of reduced basal ganglia responses to hedonic reward during interferon alfa administration. Archives of General Psychiatry, 69(10), 1044–1053. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castren E (2013). Neuronal network plasticity and recovery from depression. JAMA psychiatry, 70(9), 983–989. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, Yount S, … Group, P. C. (2010). The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005–2008. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 63(11), 1179–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl J, Ormstad H, Aass HC, Sandvik L, Malt UF, & Andreassen OA (2016). Recovery from major depressive disorder episode after non-pharmacological treatment is associated with normalized cytokine levels. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 134(1), 40–47. doi: 10.1111/acps.12576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, & Kelley KW (2008). From inflammation to sickness and depression: when the immune system subjugates the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 9(1), 46–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bie J, Lim CK, & Guillemin GJ (2016). Progesterone Alters Kynurenine Pathway Activation in IFN-gamma-Activated Macrophages - Relevance for Neuroinflammatory Diseases. International journal of tryptophan research : IJTR, 9, 89–93. doi: 10.4137/IJTR.S40332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeRubeis RJ, Hollon SD, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Young PR, Salomon RM, … Gallop R (2005). Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62(4), 409–416. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.4.409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo RA, Ramsey K, Buckley DI, Michaels L, Kobus A, Eckstrom E, … Morris C (2015). Performance of a Patient Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Short Form in Older Adults with Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain. Pain Medicine, 17(2), 314–324. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnv046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Barrera M Jr., Martell C, Munoz RF, & Lewinsohn PM (2011). The origins and current status of behavioral activation treatments for depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 7, 1–38. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032210-104535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimidjian S, Hollon SD, Dobson KS, Schmaling KB, Kohlenberg RJ, Addis ME, … Jacobson NS (2006). Randomized trial of behavioral activation, cognitive therapy, and antidepressant medication in the acute treatment of adults with major depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(4), 658–670. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.4.658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doering LV, Cross R, Vredevoe D, Martinez-Maza O, & Cowan MJ (2007). Infection, depression, and immunity in women after coronary artery bypass: a pilot study of cognitive behavioral therapy. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine, 13(3), 18–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doolin K, Allers KA, Pleiner S, Liesener A, Farrell C, Tozzi L, … O’Keane V (2018). Altered tryptophan catabolite concentrations in major depressive disorder and associated changes in hippocampal subfield volumes. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 95, 8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Driessen E, Van HL, Don FJ, Peen J, Kool S, Westra D, … Dekker JJ (2013). The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychodynamic therapy in the outpatient treatment of major depression: a randomized clinical trial. The American journal of psychiatry, 170(9), 1041–1050. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12070899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI, Berkman ET, Inagaki TK, Rameson LT, Mashal NM, & Irwin MR (2010). Inflammation-induced anhedonia: endotoxin reduces ventral striatum responses to reward. Biological Psychiatry, 68(8), 748–754. doi:S0006–3223(10)00599–8 [pii] 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euteneuer F, Dannehl K, Del Rey A, Engler H, Schedlowski M, & Rief W (2017). Immunological effects of behavioral activation with exercise in major depression: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Translational psychiatry, 7(5), e1132. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felger JC, & Treadway MT (2017). Inflammation Effects on Motivation and Motor Activity: Role of Dopamine. Neuropsychopharmacology, 42(1), 216–241. doi: 10.1038/npp.2016.143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch H (2017). Multilevel modeling in the presence of outliers: A comparison of robust estimation methods. Psicologia, 38, 57–92. [Google Scholar]

- Gazal M, Souza LD, Fucolo BA, Wiener CD, Silva RA, Pinheiro RT, … Kaster MP (2013). The impact of cognitive behavioral therapy on IL-6 levels in unmedicated women experiencing the first episode of depression: a pilot study. Psychiatry Research, 209(3), 742–745. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2013.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemin GJ (2012). Quinolinic acid, the inescapable neurotoxin. The FEBS journal, 279(8), 1356–1365. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2012.08485.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halaris A, Myint AM, Savant V, Meresh E, Lim E, Guillemin G, … Sinacore J (2015). Does escitalopram reduce neurotoxicity in major depression? Journal of Psychiatric Research, 66–67, 118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2015.04.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haroon E, Welle JR, Woolwine BJ, Goldsmith DR, Baer W, Patel T, … Miller AH (2020). Associations among peripheral and central kynurenine pathway metabolites and inflammation in depression. Neuropsychopharmacology, 45(6), 998–1007. doi: 10.1038/s41386-020-0607-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyes MP, & Morrison PF (1997). Quantification of local de novo synthesis versus blood contributions to quinolinic acid concentrations in brain and systemic tissues. Journal of Neurochemistry, 68(1), 280–288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchon CA, Zhang L, Peschken CA, Lix LM, Graff LA, Fisk JD, … Marrie R (2019). The validity and reliability of screening measures for depression and anxiety disorders in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Research (Hoboken). doi: 10.1002/acr.24011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howren MB, Lamkin DM, & Suls J (2009). Associations of depression with C-reactive protein, IL-1, and IL-6: a meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 71(2), 171–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Breen EC, Witarama T, Carrillo C, Sadeghi N, … Cole S (2015). Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Tai Chi Reverse Cellular and Genomic Markers of Inflammation in Late-Life Insomnia: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Biological Psychiatry, 78(10), 721–729. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin MR, Olmstead R, Carrillo C, Sadeghi N, Breen EC, Witarama T, … Nicassio P (2014). Cognitive behavioral therapy vs. Tai Chi for late life insomnia and inflammatory risk: a randomized controlled comparative efficacy trial. Sleep, 37(9), 1543–1552. doi: 10.5665/sleep.4008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadriu B, Farmer CA, Yuan P, Park LT, Deng ZD, Moaddel R, … Zarate CA Jr. (2019). The kynurenine pathway and bipolar disorder: intersection of the monoaminergic and glutamatergic systems and immune response. Molecular Psychiatry. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0589-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keri S, Szabo C, & Kelemen O (2014). Expression of Toll-Like Receptors in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and response to cognitive-behavioral therapy in major depressive disorder. Brain Behavior and Immunity, 40, 235–243. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2014.03.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein SL, & Flanagan KL (2016). Sex differences in immune responses. Nature Reviews Immunology, 16(10), 626–638. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse JL, Congdon E, Olmstead R, Njau S, Breen EC, Narr KL, … Irwin MR (2018). Inflammation and Improvement of Depression Following Electroconvulsive Therapy in Treatment-Resistant Depression. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 79(2). doi: 10.4088/JCP.17m11597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch MA (2015). Neuroinflammatory changes negatively impact on LTP: A focus on IL-1beta. Brain Research, 1621, 197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2014.08.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martell CR, Dimidjian S, & Herman-Dunn R (2010). Behavioral activation for depression: A clinician’s guide: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meier TB, Drevets WC, Teague TK, Wurfel BE, Mueller SC, Bodurka J, … Savitz J (2018). Kynurenic acid is reduced in females and oral contraceptive users: Implications for depression. Brain Behavior, and Immunity, 67, 59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier TB, Drevets WC, Wurfel BE, Ford BN, Morris HM, Victor TA, … Savitz J (2016). Relationship between neurotoxic kynurenine metabolites and reductions in right medial prefrontal cortical thickness in major depressive disorder. Brain Behavior, and Immunity, 53, 39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore RC, Chattillion EA, Ceglowski J, Ho J, von Kanel R, Mills PJ, … Mausbach BT (2013). A randomized clinical trial of Behavioral Activation (BA) therapy for improving psychological and physical health in dementia caregivers: results of the Pleasant Events Program (PEP). Behavioral Research and Therapy, 51(10), 623–632. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2013.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira FP, Cardoso Tde A, Mondin TC, Souza LD, Silva R, Jansen K, … Wiener CD (2015). The effect of proinflammatory cytokines in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Journal of Neuroimmunology, 285, 143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.06.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mura G, Moro MF, Patten SB, & Carta MG (2014). Exercise as an add-on strategy for the treatment of major depressive disorder: a systematic review. CNS Spectrums, 19(6), 496–508. doi: 10.1017/S1092852913000953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myint AM, Kim YK, Verkerk R, Scharpe S, Steinbusch H, & Leonard B (2007). Kynurenine pathway in major depression: evidence of impaired neuroprotection. Journal of Affective Disorders, 98(1–2), 143–151. doi:S0165–0327(06)00323–5 [pii] 10.1016/j.jad.2006.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor JC, Lawson MA, Andre C, Moreau M, Lestage J, Castanon N, … Dantzer R (2009). Lipopolysaccharide-induced depressive-like behavior is mediated by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activation in mice. Molecular Psychiatry, 14(5), 511–522. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olfson M, & Marcus SC (2010). National trends in outpatient psychotherapy. American Journal of Psychiatry, 167(12), 1456–1463. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10040570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paoletti P, Bellone C, & Zhou Q (2013). NMDA receptor subunit diversity: impact on receptor properties, synaptic plasticity and disease. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 14(6), 383–400. doi: 10.1038/nrn3504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson SL (2015). Immune dysregulation and cognitive vulnerability in the aging brain: Interactions of microglia, IL-1beta, BDNF and synaptic plasticity. Neuropharmacology, 96(Pt A), 11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2014.12.020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilkonis PA, Yu L, Dodds NE, Johnston KL, Maihoefer CC, & Lawrence SM (2014). Validation of the depression item bank from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) in a three-month observational study. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 56, 112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2014.05.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pittenger C, & Duman RS (2008). Stress, depression, and neuroplasticity: a convergence of mechanisms. Neuropsychopharmacology, 33(1), 88–109. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romero-Sanchiz P, Nogueira-Arjona R, Araos P, Serrano A, Barrios V, Argente J, … Fonseca FR (2020). Variation in chemokines plasma concentrations in primary care depressed patients associated with Internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy. Scientific reports, 10(1), 1078. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-57967-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago J, Akeman E, Kirlic N, Clausen AN, Cosgrove KT, McDermott TJ, … Aupperle RL (2020). Protocol for a randomized controlled trial examining multilevel prediction of response to behavioral activation and exposure-based therapy for generalized anxiety disorder. Trials, 21(1), 17. doi: 10.1186/s13063-019-3802-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz J (2020). The kynurenine pathway: a finger in every pie. Molecular Psychiatry, 25(1), 131–147. doi: 10.1038/s41380-019-0414-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz J, Drevets WC, Smith CM, Victor TA, Wurfel BE, Bellgowan PS, … Dantzer R (2015). Putative neuroprotective and neurotoxic kynurenine pathway metabolites are associated with hippocampal and amygdalar volumes in subjects with major depressive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology, 40(2), 463–471. doi: 10.1038/npp.2014.194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savitz J, Drevets WC, Wurfel BE, Ford BN, Bellgowan PS, Victor TA, … Dantzer R (2015). Reduction of kynurenic acid to quinolinic acid ratio in both the depressed and remitted phases of major depressive disorder. Brain Behavior, and Immunity, 46, 55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2015.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlittler M, Goiny M, Agudelo LZ, Venckunas T, Brazaitis M, Skurvydas A, … Andersson DC (2016). Endurance exercise increases skeletal muscle kynurenine aminotransferases and plasma kynurenic acid in humans. American Journal Physiology Cell Physiology, 310(10), C836–840. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00053.2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwieler L, Samuelsson M, Frye MA, Bhat M, Schuppe-Koistinen I, Jungholm O, … Erhardt S (2016). Electroconvulsive therapy suppresses the neurotoxic branch of the kynurenine pathway in treatment-resistant depressed patients. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 13(1), 51. doi: 10.1186/s12974-016-0517-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpe L, & Schrieber L (2012). A blind randomized controlled trial of cognitive versus behavioral versus cognitive-behavioral therapy for patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Psychotherapy and psychosomatics, 81(3), 145–152. doi: 10.1159/000332334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharpley CF (2010). A review of the neurobiological effects of psychotherapy for depression. Psychotherapy (Chic), 47(4), 603–615. doi: 10.1037/a0021177 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, & Raj BA (1996). The measurement of disability. International Clinical Psychopharmacology, 11, 89–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, … Dunbar GC (1998). The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59 Suppl 20, 22–33;quiz 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shields GS, Spahr CM, & Slavich GM (2020). Psychosocial Interventions and Immune System Function: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA psychiatry. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.0431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor CB, Conrad A, Wilhelm FH, Strachowski D, Khaylis A, Neri E, … Spiegel D (2009). Does improving mood in depressed patients alter factors that may affect cardiovascular disease risk? Journal of Psychiatric Research, 43(16), 1246–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdonk F, Petit AC, Abdel-Ahad P, Vinckier F, Jouvion G, de Maricourt P, … Gaillard R (2019). Microglial production of quinolinic acid as a target and a biomarker of the antidepressant effect of ketamine. Brain Behavior, and Immunity, 81, 361–373. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wurfel BE, Drevets WC, Bliss SA, McMillin JR, Suzuki H, Ford BN, … Savitz JB (2017). Serum kynurenic acid is reduced in affective psychosis. Translational psychiatry, 7(5), e1115. doi: 10.1038/tp.2017.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura R, Hori H, Ikenouchi-Sugita A, Umene-Nakano W, Katsuki A, Atake K, & Nakamura J (2013). Plasma levels of interleukin-6 and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor response in patients with major depressive disorder. Human Psychopharmacology, 28(5), 466–470. doi: 10.1002/hup.2333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young KD, Drevets WC, Dantzer R, Teague TK, Bodurka J, & Savitz J (2016). Kynurenine pathway metabolites are associated with hippocampal activity during autobiographical memory recall in patients with depression. Brain Behavior, and Immunity, 56, 335–342. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2016.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yount SE, Beaumont JL, Chen SY, Kaiser K, Wortman K, Van Brunt DL, … Cella D (2016). Health-Related Quality of Life in Patients with Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. Lung, 194(2), 227–234. doi: 10.1007/s00408-016-9850-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabihiyeganeh M, Vafaee Afshar S, Amini Kadijani A, Jafari D, Bagherifard A, Janbozorgi M, … Mirzaei A (2019). The effect of cognitive behavioral therapy on the circulating proinflammatory cytokines of fibromyalgia patients: A pilot controlled clinical trial. General Hospital Psychiatry, 57, 23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2019.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahra D, & Hedge C (2010). The reliable change index: Why isn’t it more popular in academic psychology? Psychology Postgraduate Affairs Group Quarterly, 76, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Zautra AJ, Davis MC, Reich JW, Nicassario P, Tennen H, Finan P, … Irwin MR (2008). Comparison of cognitive behavioral and mindfulness meditation interventions on adaptation to rheumatoid arthritis for patients with and without history of recurrent depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76(3), 408–421. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.3.408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Y, Zheng W, Liu W, Wang C, Zhan Y, Li H, … Ning Y (2018). Antidepressant effect of repeated ketamine administration on kynurenine pathway metabolites in patients with unipolar and bipolar depression. Brain Behavior, and Immunity, 74, 205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2018.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zunszain PA, Anacker C, Cattaneo A, Choudhury S, Musaelyan K, Myint AM, … Pariante CM (2012). Interleukin-1beta: a new regulator of the kynurenine pathway affecting human hippocampal neurogenesis. Neuropsychopharmacology : official publication of the American College of Neuropsychopharmacology, 37(4), 939–949. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.