Abstract

Building on the concept of externalities, we propose an explanation of how multinationals can contribute to the enactment of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals as part of their ordinary investments. First, we suggest grouping the 17 Sustainable Development Goals into six categories based on whether they increase positive externalities – knowledge, wealth, or health – or reduce negative externalities – the overuse of natural resources, harm to social cohesion, or overconsumption. Second, we propose placing these categories within an extended value chain to facilitate their implementation. Third, we argue that multinationals’ internal investments in host-country subsidiaries to improve their competitiveness contribute to addressing externalities in host-country communities, while external investments in host communities to solve underdevelopment generate competitiveness externalities on host-country subsidiaries.

Keywords: externalities, international business, multinationals, grand challenges, Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), sustainability

Résumé

Nous appuyant sur le concept d’externalités, nous proposons une explication de la manière dont les entreprises multinationales peuvent contribuer à l’adoption des objectifs de développement durable des Nations Unies dans le cadre de leurs investissements ordinaires. Premièrement, nous suggérons de regrouper les 17 objectifs de développement durable en six catégories selon qu'ils augmentent les externalités positives - connaissance, richesse ou santé - ou réduisent les externalités négatives - la surutilisation des ressources naturelles, l’atteinte à la cohésion sociale ou la surconsommation. Deuxièmement, nous proposons de placer ces catégories dans une chaîne de valeur étendue pour faciliter leur mise en œuvre. Troisièmement, nous argumentons que les investissements internes des entreprises multinationales dans leurs filiales dans le pays d’accueil, destinés à améliorer la compétitivité de ces dernières, contribuent à lutter contre les externalités dans les communautés du pays d’accueil, tandis que les investissements externes dans ces dernières, destinés à résoudre le sous-développement, génèrent les externalités de compétitivité sur les filiales dans le pays d’accueil.

Resumen

Basándonos en el concepto de externalidad, proponemos una explicación de cómo las multinacionales pueden contribuir a la promulgación de los Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible de las Naciones Unidas como parte de sus inversiones. Primero, sugerimos agrupar los 17 Objetivos de Desarrollo Sostenible en seis categorías basado en si estas aumentan las externalidades positivas -conocimiento, riqueza o salud- o reducen las externalidades negativas -el uso excesivo de recursos naturales, daño a la cohesión social y consumo excesivo. Segundo, proponemos situar estas categorías dentro de una cadena de valor ampliada para facilitar su implementación. Tercero, argumentamos que las inversiones internas de las multinacionales en los países anfitriones de las filiales puede mejorar su competitividad para abordar las externalidades en las comunidades del país anfitrión, mientras que las inversiones externas en comunidades del país anfitrión para resolver el subdesarrollo genera externalidades de competitividad en las filiales del país anfitrión.

Resumo

Com base no conceito de externalidades, propomos uma explicação de como multinacionais podem contribuir para a implementação dos Objetivos de Desenvolvimento Sustentável das Nações Unidas como parte de seus investimentos ordinários. Em primeiro lugar, sugerimos agrupar os 17 Objetivos de Desenvolvimento Sustentável em seis categorias com base em se eles aumentam externalidades positivas - conhecimento, riqueza ou saúde - ou reduzem externalidades negativas – o uso excessivo de recursos naturais, danos à coesão social ou consumo excessivo. Em segundo lugar, propomos colocar essas categorias em uma cadeia de valor estendida para facilitar sua implementação. Em terceiro lugar, argumentamos que investimentos internos de multinacionais em subsidiárias do país anfitrião para melhorar sua competitividade contribuem para abordar as externalidades nas comunidades do país anfitrião, enquanto investimentos externos em comunidades anfitriãs para resolver o subdesenvolvimento geram externalidades de competitividade nas subsidiárias do país anfitrião.

摘要

在外部性概念的基础上, 我们解释了跨国公司如何能够作为其普通投资的 – 部分为联合国可持续发展目标的制定做出贡献。第一, 我们建议根据它们是否增加正外部性 (知识、财富或健康) 或减少负外部性 (自然资源过度使用, 对社会凝聚力的破害或过度消费) 将17个可持续发展目标分为六类。第二, 我们建议将这些类别放在扩展的价值链中以促进其实施。第三, 我们认为, 跨国公司为提高其东道国子公司的竞争力的内部投资有助于解决东道国社区的外部性, 而为解决发展不足对东道国社区的外部投资在东道国子公司中产生竞争力外部性。

At Grupo Nutresa, we understood that sustainability is the framework that encompasses the operation, that there is no profitable growth without integrating environmental or social issues. That’s what makes an organization and its stakeholders gain or lose value. [...] This has been the result of deep discussions because, after all, when you start building your strategy with the SDGs, [you see] they are very intertwined. However, we asked ourselves where we can have a stronger positive influence on the SDGs, and how we really manage to contribute to the global agenda.

Claudia Rivera, Sustainability Director of the Colombian food multinational Grupo Nutresa, interviewed on July 1, 2020

INTRODUCTION

Climate change, extreme poverty, and pandemics are all grand challenges, i.e., large intractable global problems that bedevil the world. The usual attitude in the face of these grand challenges is to ask governments to coordinate their actions and to collaborate in addressing them. This has resulted not only in the creation of intergovernmental organizations like the United Nations or the World Bank but also in programs within these organizations to focus attention on crucial issues. Thus, in 2015, the United Nations adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and established 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) for governments to achieve by 2030. This is considered one of the most effective plans of action to address pressing grand challenges (Kolk, Kourula, & Pisani, 2017; Sachs, Schmidt-Traub, Mazzucato, Messner, Nakicenovic, & Rockström, 2019; Salvia, Leal Filho, Brandli, & Griebeler, 2019; van Zanten & van Tulder, 2018). However, despite the increasing calls for management research to analyze grand challenges (George, Howard-Grenville, Joshi, & Tihanyi, 2016) and critical issues (Tihanyi, 2020), and for international business research to rethink current agendas towards grand challenges (Buckley, Doh, & Benischke, 2017), it is unclear how international business research can contribute to the SDGs, as they are designed as country-level goals for governments to achieve, not as firm-level goals. Although multinationals are increasingly rethinking their objectives and shifting from profit to value maximization (Business Roundtable, 2019) by embracing the SDGs (United Nations Global Compact & Accenture, 2019), implementation is still incomplete (van Zanten & van Tulder, 2018).

Hence, building on the concept of externalities, we propose an explanation of how multinationals can contribute to enacting the United Nations’ SDGs as part of their ordinary investments. Specifically, we introduce three mechanisms for translating the country-level SDGs into firm-level actions. First, we suggest grouping the 17 SDGs into six categories based on whether they increase positive externalities (knowledge, wealth, or health) or reduce negative externalities (the overuse of natural resources, harm to social cohesion, or overconsumption). Second, we propose placing these categories within an extended value chain to facilitate their implementation. Third, we argue that multinationals’ internal investments in host-country subsidiaries to improve their competitiveness contribute to addressing externalities in host-country communities, while external investments in host communities to solve underdevelopment generate competitiveness externalities in host-country subsidiaries.

These arguments contribute to two streams of international business research: corporate sustainability studies and theorization on multinational behavior. First, to the literature on global corporate sustainability, the paper offers a framework for making the SDGs actionable by multinationals. Sustainability is increasingly becoming a crucial topic in international business (Grinstein & Riefler, 2015; Kim & Davis, 2016; Kolk, 2010; Linnenluecke & Griffiths, 2010; Maksimov, Wang, & Yan, 2019; Pinkse & Kolk, 2012; Shapiro, Hobdari, & Oh, 2018; Yakovleva & Vazquez-Brust, 2018). As part of their sustainability efforts, multinationals are increasingly embracing the SDGs in their corporate strategy (Donoher, 2017; Giuliani, Santangelo, & Wettstein, 2016; Witte & Dilyard, 2017), but these are limited actions that commonly focus on reducing negative effects (van Zanten & van Tulder, 2018). We provide a prescriptive framework to help reduce the criticism that the SDGs are too abstract and numerous to elicit focused actions by firms (MacFeely, 2019; van Zanten & van Tulder, 2018), so that multinationals can help create societal value in addition to profit. The prescriptive framework also offers guidance for researchers by providing an explanation of the mechanisms by which the SDGs can be implemented by multinationals through subsidiaries’ investments. The propositions can be tested by future empirical studies analyzing multinational investments and SDGs.

Second, for the theorization on multinational behavior, we propose a reconsideration of some of the basic arguments by explicitly incorporating the role of externalities. Despite the importance of externalities in international business (Buckley, 2009; Buckley & Ghauri, 2004), many theoretical models underplay them. A common approach is acknowledging unintended technological spillovers and how multinationals should aim to reduce them despite their positive impact on the host country (Blomström & Kokko, 1998; Cantwell & Piscitello, 2005; Castellani & Zanfei, 2006; Das, 1987). However, large firms and multinationals can facilitate social value creation and the solution of externalities (Cuervo-Cazurra, 2018; Fisman & Khanna, 2004; Rygh, 2019; Sinkovics & Archie-acheampong, 2019). We place externalities, both positive and negative, at the heart of our arguments. On the one hand, we explain how subsidiaries’ investments to improve competitiveness have externalities that contribute to the implementation of SDGs in the host countries. On the other hand, we argue that multinationals’ investments aimed to improve the context and address the SDGs have externalities on the subsidiaries. The explicit inclusion of the generation of positive externalities and the avoidance of negative ones changes predictions on internationalization decisions, helping reinvigorate international business research (Buckley, 2002; Buckley & Lessard, 2005; Peng, 2004) by relaxing some of the assumptions of existing theories regarding value creation in multinationals. Integrating the SDGs within multinationals’ objectives facilitates a move from short-term economic value to long-term sustainable value, and offers a new view of the nexus between business and society in which multinationals become part of the solution to grand challenges rather than contributors to the problems.

ADDRESSING GRAND CHALLENGES: THE SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS

The United Nations has spearheaded the coordination of activities for tackling grand challenges that affect humanity. A significant concerted effort identified the Millennium Development Goals in 2000 at the United Nations Millennium Declaration and established eight goals to achieve by 2015 (United Nations, 2000). The partial success of the Millennium Development Goals in transforming developing countries led to the creation of a more global agenda, the SDGs (Griggs, Stafford-Smith, Gaffney, Rockström, Öhman, Shyamsundar, Steffen, Glaser, Kanie, & Noble, 2013). These were a call to end poverty, improve the lives of all, and protect the planet in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (United Nations, 2015). The SDGs expanded the 8 Millennium Development Goals to 17 goals to be achieved by 2030. The 17 SDGs are (United Nations, 2015): (1) No poverty; (2) Zero hunger; (3) Good health and well-being; (4) Quality education; (5) Gender equality; (6) Clean water and sanitation; (7) Affordable and clean energy; (8) Decent work and economic growth; (9) Industry, innovation, and infrastructure; (10) Reducing inequality; (11) Sustainable cities and communities; (12) Responsible consumption and production; (13) Climate action; (14) Life below water; (15) Life on land; (16) Peace, justice, and strong institutions; and (17) Partnerships for the goals. Unlike the Millennium Development Goals, which mainly targeted developing and underdeveloped countries, the SDGs explicitly call for a more balanced participation from advanced and developing nations, and acknowledge the important role played by the private sector.

Firms’ contribution to the SDG agenda is challenging for two reasons. First, the extensive scope and complexity of the 17 SDGs, 169 targets, and 232 unique indicators easily overwhelm and prevent action (Easterly, 2015; Nilsson, Chisholm, Griggs, Howden-Chapman, McCollum, Messerli, Neumann, Stevance, Visbeck, & Stafford-Smith, 2018). Second, there is a lack of a common understanding of how to operationalize the SDGs by firms because the SDGs are designed as country-level targets. Although the SDG Compass (Global Reporting Initiative, United Nations Global Compact, & World Business Council for Sustainable Development, 2015) and the SDG Action Manager (B Lab & United Nations Global Compact, 2020) provide tools for measuring and reporting on the SDGs, they leave it up to the firms to interpret how to integrate the SDGs into their operations.

Translating the SDGs for International Business: Value Chain, Externalities, and Investments

Hence, we propose a framework to help multinationals implement the SDGs. The framework builds on the concept of externalities as the theoretical driver of the translation of SDGs into multinationals’ actions in three steps: (1) grouping of SDGs by their impact on the positive and negative externalities created by multinationals; (2) positioning of SDGs along the value chain; and (3) identifying how internal and external investments contribute to the SDGs and subsidiaries’ competitiveness.

Grouping the SDGs by their impact on externalities

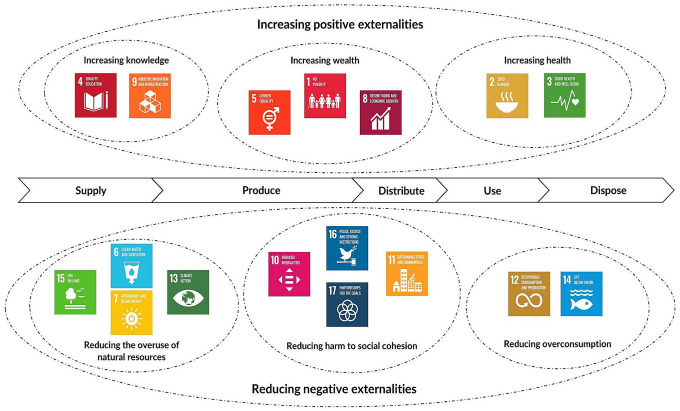

The first element in the framework is the grouping of SDGs into six broad categories depending on whether they enable the development of positive externalities (knowledge, wealth, and health) or help reduce negative externalities (the overuse of natural resources, harm to social cohesion, or overconsumption) as we illustrate in Figure 1. Externalities refer to situations in which third parties unwillingly bear costs or receive benefits from companies’ actions (Ayres & Kneese, 1969; Baumol, 1972). Externalities are classified as positive when third parties receive benefits from firm activities without paying for them; a typical example is technological spillover. Externalities are classified as negative when third parties suffer the costs of firm activities and are uncompensated for such costs; pollution is the classic example. Our conceptualization of externalities in the SDGs modifies the traditional views of reducing negative externalities for fear of punishment or limiting positive externalities for fear of losing advantage discussed in previous research. Multinationals’ efforts in addressing sustainability challenges have been driven by a desire to reduce negative externalities, especially for the environment, and the associated financial punishments and reputational harm in host countries (Jiang, Jung, & Makino, 2020). The technological spillovers of multinationals in host countries through employee mobility, training of suppliers and distributors, and competitive imitation (Blomström & Kokko, 1998; Cantwell & Piscitello, 2005; Castellani & Zanfei, 2006; Kano, 2018) are a form of positive externality, but the usual recommendation is for managers to reduce such positive spillovers (Buckley, 2009; Zhao, 2006).

Figure 1.

Translating SDGs into actionable goals for multinationals to address externalities. Note that the use of the SDG icons is permitted under the United Nations Department of Global Communications (United Nations, 2019).

Positioning the SDGs in the value chain

The second element for translating the country-level SDGs into concrete actions for multinationals is the value chain. The value chain is an economics-based framework that classifies firms’ activities into two main types (Porter, 1985): primary activities that directly enable the creation of value and secondary activities that support the primary activities. The primary activities were originally organized along an input–output chain as inbound logistics, operations, outbound logistics, marketing and sales, and service (Porter, 1985). The value chain has been refined and extended over time to incorporate the life cycle of products and services (Klöpffer, 1997). One of these refinements is the extended producer responsibility (Atasu & Subramanian, 2012) that suggests five activities: supply, produce, distribute, use, and dispose. Hence, in Figure 1, we position the 17 SDGs along this extended value chain. We propose connecting the SDGs related to increasing knowledge to the supply and production activities: those linked to increasing wealth to the production and distribution activities; SDGs related to increasing health to the distribution, use, and disposal activities; SDGs associated with reducing the overuse of natural resources to the supply and production activities; those connected with reducing harm to social cohesion to the production, distribution, and use activities; and goals related to reducing overconsumption to the use and disposal activities. This approach clarifies the primary actions and investments that multinationals can take to address each goal.

Identifying internal and external investments that contribute to the SDGs

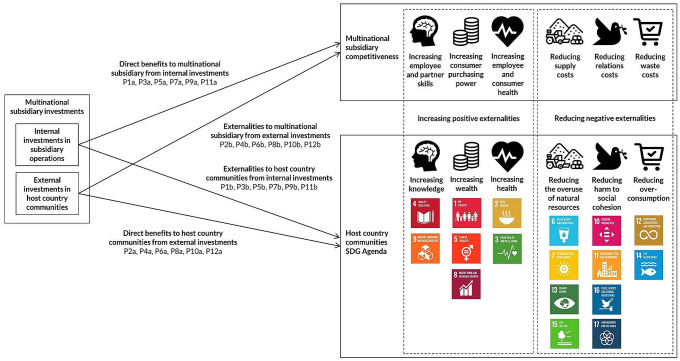

The third element of the framework is analyzing the multinationals’ internal and external investments in host countries that enable the achievement of SDGs. We classify multinational investments into internal and external based on where they are made. On the one hand, internal investments are those made by the host-country subsidiary in primary stakeholders, i.e., stakeholders that have an explicit contractual relationship with the firm, like employees, suppliers, and distributors. We propose that these internal investments generate direct benefits for the multinational and have the potential to indirectly strengthen positive externalities or to reduce negative externalities in host-country communities, thus contributing to the SDG agenda. On the other hand, multinational external investments are those implemented in the host-country communities targeting secondary stakeholders, i.e., stakeholders that lack an explicit contractual relationship with the firm, such as local communities, the public at large, and interest groups; these investments are commonly made in collaboration with governments, non-governmental organizations, and transnational institutions. These external investments are designed to address externalities and directly contribute to the host-country SDG agenda as well as indirectly benefit multinationals.

Figure 2 summarizes the resulting framework and propositions. We first discuss how investments can contribute to positive externalities and then how they address negative externalities. In each case, we discuss the internal and external investments and illustrate the ideas with an extended example.

Figure 2.

Multinational subsidiary investments and host-country communities SDG agenda. Note that the use of the SDG icons is permitted under the United Nations Department of Global Communications (United Nations, 2019). Use of the six icons representing each of the externalities is permitted by the Noun Project under a Creative Commons license.

Multinationals’ Investments that Address the SDGs to Increase Positive Externalities

We first argue that multinationals can design their investments and activities to contribute to the implementation of SDGs that strengthen positive externalities. Although appealing, this idea appears to counter theoretical arguments for limiting the firm’s positive externalities to protect advantage or separating investments with high positive externalities from the firm’s operations.

First, some scholars recommend that multinationals in host countries limit positive externalities in technology. Multinationals commonly bring more sophisticated technologies and innovations to the host country that eventually become diffused among local companies through unintended spillovers (Blomström & Kokko, 1998; Blomström, Kokko, & Mucchielli, 2003). Hence, multinationals’ managers may design mechanisms that limit such diffusion to others because it undermines competitive advantage (Buckley, 2009; Zhao, 2006). Some of these mechanisms involve, for example, mitigating the investments provided to suppliers and distributors so that they do not upgrade their capabilities and become eventual competitors (Perri, Andersson, Nell, & Santangelo, 2013), reasserting their strategic power to keep control over partners (Kano, 2018); establishing non-compete contracts that prevent employees from joining competitors for some time after leaving the firm to reduce spillovers via employee mobility (Aydinliyim, 2020; Garber, 2013; Nandkumar & Srikanth, 2016); or building complexity and secrecy into the operation to reduce imitation (de Faria & Sofka, 2010).

Second, multinationals typically invest in corporate social responsibility separately from the firms’ core value chain activities, especially in the form of corporate philanthropy (Ite, 2004; Shah, 2013). A common corporate social responsibility approach is to invest in impactful activities in local communities in collaboration with not-for-profit organizations, because the latter have expertise in addressing local needs that multinationals lack (Dahan, Doh, Oetzel, & Yaziji, 2010; Husted, 2003; Lev, Petrovits, & Radhakrishnan, 2010; Newenham-Kahindi, 2011; Teegen, Doh, & Vachani, 2004). These corporate social responsibility investments are usually separate from the activities of the company and managed independently from the firm’s operations. In some cases, they are funded from the budget of the firm’s foundation rather than from the general budget, since they are conceived as charitable contributions rather than investments (Husted, 2003; Lev et al., 2010). Multinationals report these investments in their corporate social responsibility reports, describing the actions and investments undertaken, the partner organizations with which they collaborate, and the apparent successes. Although many of these investments have substantial positive externalities, they are conceived and run separately from the company operations.

We propose integrating the SDGs within the value chain framework, thereby changing attitudes towards positive externalities and how to invest to achieve them. Managers of multinationals can rethink how their internal investments improve local communities, aiming to expand and diffuse the positive externalities to the community. They can also redesign investments with a high impact on positive spillovers as an integral part of the firm’s activities. In this way, investments in the multinationals’ operations are evaluated in terms of the benefits provided to the multinational and the positive externalities that such investments bring to local communities (Rygh, 2019). This may lead multinationals to overinvest to facilitate the multiplier effect of the investments on the host-country population. Such investments may not generate an immediate financial return, but instead provide benefits in the long run through increased reputation and more robust social contracts with local communities that support future profitability.

To enable this investment, we propose grouping the SDGs that are likely to promote positive externalities into three main themes: increasing knowledge, increasing wealth, and increasing health. We suggest these groupings from the analysis of each of the goals and their similarity in the overarching topic.

Multinationals’ investments to increase knowledge

Multinationals are well placed to have large positive externalities in creating knowledge in the host countries where they operate; their main source of advantage is their superior ability to create, transfer, and apply knowledge across countries (Kogut & Zander, 1993). This knowledge generation and dissemination can foster positive externalities for SDG 4 “Quality education: Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all”, and SDG 9 “Industry, innovation, and infrastructure: Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization and foster innovation.” Addressing these goals is important. There are 57 million primary-age children out of school and 103 million youth who lack basic literacy skills, and more than 60% of them are female (United Nations Development Programme, 2020a). Four billion people do not have internet access, and 90% are in the developing world (United Nations Development Programme, 2020b).

Internal investments in knowledge capabilities in subsidiaries not only benefit a firm’s competitiveness but can also be designed to have large positive externalities in the community and help achieve the SDGs. From a strategic standpoint, multinationals benefit more immediately from internal investments by working with more educated business partners and employees. Investments in knowledge capabilities in host-country subsidiaries can result not only in increasing labor productivity, income, value-added, and competitiveness within a supply chain (Birkinshaw, Hood, & Jonsson, 1998; Strotmann, Volkert, & Schmidt, 2019) but also in scaling-up their operations by securing sufficient local talent and improving talent management costs (Winthrop, Bulloch, Bhatt, & Wood, 2013). Investments in educating and training local value chain partners help improve their innovation capabilities and productivity (Kano, 2018; Wei & Liu, 2006), as well as enhance their morale and retention (Farndale, Scullion, & Sparrow, 2010; Reiche, 2008). At the same time, when multinationals build local human capital through employee training programs, and these highly skilled individuals may move to domestic firms or start their own business, thus creating positive knowledge spillovers (Fosfuri, Motta, & Rønde, 2001; Gershenberg, 1987). The co-development of innovation with suppliers can help the multinational obtain better services from them (Dyer, 2000). Their upgraded capabilities enable suppliers and distributors to serve other companies and train their own suppliers and distributors about superior management practices, thus further contributing to responsible innovation, education, and industry development.

We summarize these arguments in the following propositions:

Proposition 1a:

Multinational knowledge investments in a host-country subsidiary (e.g., implementing educational and training programs for employees, transferring technology to suppliers and distributors) have a positive impact on the subsidiary’s competitiveness (more educated employees and more innovative business partners).

Proposition 1b:

Multinational knowledge investments in a host-country subsidiary (e.g., implementing educational and training programs for employees, transferring technology to suppliers and distributors) create positive education externalities that contribute to the host-country SDG agenda [increasing local education (SDG 4) and innovativeness (SDG 9)].

External knowledge investments designed to develop a local community’s knowledge base and contribute to the SDGs can also benefit the multinational. Multinationals work with selective external partners, such as local non-governmental organizations, governmental agencies, or other civil society organizations, and support their efforts to increase knowledge by donating funds for investments in education. To establish the most beneficial educational programs, multinationals usually engage with local partners to identify the primary educational deficiencies in the region and how to tackle them, collaborating in building schools and other educational infrastructure, such as scholarship programs in the host country (Eweje, 2006). Such investments also have a positive knowledge spillover for the firm, since well-educated and innovative local communities will be more sophisticated and innovative business partners and employees for the firm. The external investments in innovation can also boost current employees’ commitment as they see themselves working for a firm that supports local communities (Brammer, Millington, & Rayton, 2007).

We therefore present the following propositions:

Proposition 2a:

Multinational knowledge investments in host-country communities (e.g., building local educational infrastructure, granting scholarships in local communities) have a positive impact on the host-country SDG agenda [increasing local education (SDG 4) and innovativeness (SDG 9)].

Proposition 2b:

Multinational knowledge investments in host-country communities (e.g., building local educational infrastructure, granting scholarships in local communities) generate positive education externalities for the subsidiary (securing future access to qualified talent, increasing employee motivation and commitment).

An illustration of a multinational engaged in increasing knowledge externalities globally is the Spanish financial services company, BBVA, which is the second-largest bank in Spain and among the top 50 largest in the world, with a strong presence in Latin America. BBVA sees “education to be the best vehicle for bringing the age of opportunity to even the most vulnerable” (BBVA, 2019a), and has invested in international social educational programs that have benefitted more than 2.3 million people worldwide.

One of the internal investments used by BBVA to increase knowledge is the Hope Fund program in Chile. Hope Fund trains and supports BBVA’s clients who are already microentrepreneurs and need financial support, assisting more than 120,000 clients by 2020. BBVA also has an extensive digital training system, the Campus BBVA platform. This online training platform became especially valuable during the first 48 days of the COVID-19 confinement, where the platform saw a 450% jump in digital training with more than 1.2 million hours completed (BBVA, 2020). These programs have the potential to increase BBVA’s competitiveness in its host-country operations by improving its employees’ and business partners’ knowledge skills and, therefore, its firm performance.

BBVA also engages in external investments in local communities devoted to education access, education quality, and financial education. On education access, BBVA provides scholarships to children, young people, and adults who would otherwise not have access to education. Since 2007, their Kids Ahead scholarship program to facilitate access for boys and girls in vulnerable situations has granted more than 720,000 scholarships in Mexico, Colombia, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela. On education quality, BBVA promotes social innovation in education and builds on teachers’ skills by delivering training initiatives, knowledge-building, increasing visibility, creating networks, and developing free audiovisual pedagogical content for families and teachers worldwide. For instance, BBVA’s Entrepreneurship School in Colombia has provided financial education to more than 190,000 students and 1090 teachers from 420 schools (BBVA, 2019b). In terms of fostering innovation, BBVA has also pledged investments, most of them towards accelerating digital transformation. Based on these external investments, BBVA expects to contribute to the SDG agenda by increasing local knowledge, as stated in their Pledge 2025 (BBVA, 2018).

To manage all these programs successfully and to increase positive impact, BBVA often collaborates with business associations, foundations, non-governmental organizations, local governments, and even other multinationals, like the Spanish telecommunications multinational Telefonica. For example, in Mexico, BBVA launched a collaboration with the local startup, Openpay, which offered a wide range of payment solutions and advanced online functionalities to shops and retailers, and was subsequently acquired by BBVA. Such innovation–collaboration programs aim to contribute to the SDG agenda by increasing innovation and generating positive knowledge spillovers for the multinational, when the company can access more educated and innovative talent, which enhances the subsidiary’s competitiveness.

Multinationals’ investments to increase wealth

Multinationals, as large organizations operating and controlling resources across borders, can increase wealth that will reduce inequalities in their host countries. Three interconnected SDGs relate to the positive externality of increasing wealth: SDG 1 “No Poverty: End poverty in all its forms everywhere;” SDG 5 “Gender equality: Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls;” and SDG 8 “Decent work and economic growth: Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all.” These three SDGs are interconnected. Job opportunities tackle poverty directly, especially among women, who in 2020 still have not reached economic equality anywhere globally and, therefore, are more likely to be poor (Oxfam, 2020). Gender seems to exacerbate inequality. By 2014, 143 countries included gender equality in their Constitution, but 52 countries did not (United Nations, 2018), and, by 2018, working women were still making 20% less than men worldwide (Belser, Vazquez-Alvarez, & Xu, 2018). Although the world has made significant progress in reducing extreme poverty – i.e., people living on less than USD1.90 a day – from 1.9 billion people or 36% of the world’s population in 1990 to 734 million or 10% in 2015, the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic reversed this trend and extreme poverty has risen, and almost half of the world population still lives on less than USD5.5 a day or USD2000 a year (World Bank, 2020).

Multinationals’ internal investments in subsidiaries, such as implementing local hiring programs that provide decent work conditions and benefits, can help the subsidiaries be more competitive while contributing to societal advancement. Multinationals can embrace a diverse workforce in terms of gender and ethnicity (Ferner, Almond, & Colling, 2005), improving working conditions in their host-country operations and among business partners across their global value chains, where they exercise indirect control. Multinationals can also prevent irresponsible practices, such as child exploitation (Kolk & van Tulder, 2004), sweatshop conditions (Radin & Calkins, 2006), or modern slavery (Burmester, Michailova, & Stringer, 2019), by forbidding them as part of their supply contracts and enforcing such contractual agreements in their global value chains. By taking an extended social responsibility view in their own operations and those of their business partners, multinationals can invest in training and require local value chain partners to ensure decent work conditions across their entire supply chain. These investments have large positive externalities on work conditions as suppliers and distributors improve their own standards and help spread improved work practices to their own suppliers. Furthermore, multinational internal investments to increase wealth can also be attained by focusing on the poorest segments of society, the base of the pyramid (London & Hart, 2004; Prahalad, 2005), and innovating improved and more affordable products by, for example, customizing them to the local needs (Prahalad & Hammond, 2002). These investments can have positive externalities by providing better quality products and services (e.g., smartphones and the internet) to poor communities who can use these to upgrade their work abilities and skills, such as financial literacy and savings (Chibba, 2009).

Regarding gender equality, i.e., the equal treatment of women and men in the workplace (Eden & Gupta, 2017), multinationals also have an opportunity to empower women within their host-country subsidiaries. Gender inequality is a “wicked problem,” as it is systemic, ambiguous, complex, and conflictual, and it needs public–private partnerships to be addressed successfully (Eden & Wagstaff, 2021). Multinationals can ensure equal benefits by actively promoting their female employees to leadership positions in subsidiaries, even when equality might not be the norm in the host country, helping them access a qualified and underutilized workforce that supports their success (Siegel, Pyun, & Cheon, 2019). Increased gender equality can improve organizational performance (Hoogendoorn, Oosterbeek, & van Praag 2013; Roh & Kim, 2016) and overall global growth (Woetzel, Madgavkar, Ellingrud, Labaye, Devillard, Kutcher, Manyika, Dobbs, & Krishnan, 2015). It also has large externalities in the local communities, as women’s empowerment, combined with gender-equality policies, contributes to economic development (Duflo, 2012). All these internal wealth investments benefit the firm through positive externalities by growing the market while increasing local stakeholders’ purchasing power, especially individual consumers in emerging countries, contributing to SDGs 1, 5, and 8.

In line with these arguments, we propose:

Proposition 3a:

Multinational wealth investments in a host-country subsidiary (e.g., sponsoring equal opportunity programs, using decent work conditions among value chain partners in the host countries) have a positive impact on the subsidiary’s competitiveness (increasing the purchasing power of the local consumer base).

Proposition 3b:

Multinational wealth investments in a host-country subsidiary (e.g., sponsoring equal opportunity programs, using decent work conditions among value chain partners in the host countries) generate positive wealth externalities that contribute to the host-country SDG agenda [reducing poverty (SDG 1), fostering gender equality (SDG 5), and promoting decent work and sustainable economic growth (SDG 8)].

Engaging in external investments to increase wealth in host-country communities is likely to advance the SDG agenda and generate positive externalities for multinationals at the same time. To address economic inequalities in local communities, multinationals can consider partnering with other organizations, such as local governments, non-profits, and international non-governmental organizations (VanSandt & Sud, 2012). Such partnerships can provide a better understanding of the local communities’ main deficiencies (Calton, Werhane, Hartman, & Bevan, 2013), so that multinationals can formulate effective external investment options that have the potential to increase wealth and to foster local development. Multinationals can, for example, provide resources and training programs for their entrepreneurial efforts and support local agencies’ development investments in poor communities to enable development (Eweje, 2006). To promote gender equality, multinationals can also provide training programs specifically designed for women-owned local businesses, and potentially integrate these local businesses within their value chain as local suppliers (Eden & Wagstaff, 2021). Such investments will have a positive impact on local communities but can also generate positive externalities for the subsidiary operations, when wealthier locals are able to become entrepreneurs and potential value chain partners for the multinational and some become final consumers of the firm’s products and services. They can also help attract investors who are interested in funding firms with a robust social investment ethos.

We summarize these arguments in the following propositions:

Proposition 4a:

Multinational wealth investments in host-country communities (e.g., investing in entrepreneurship projects focused on poor consumers, implementing women’s entrepreneurship programs in the host countries) have a positive impact on the host-country SDG agenda [reducing poverty (SDG 1), fostering gender equality (SDG 5), and promoting decent work and sustainable economic growth (SDG 8)].

Proposition 4b:

Multinational wealth investments in host-country communities (e.g., investing in entrepreneurship projects focused on poor consumers, implementing women’s entrepreneurship programs in the host countries) create positive wealth externalities for the subsidiary (securing future competitive local value chain partners and wealthier consumers).

An example of multinational devoting resources to increase wealth is Careem, an Emirati-based ride-hailing service provider. Since being established in 2012, the company has expanded into 15 Middle Eastern, Northern African, and South Asian countries; in 2019, it was acquired by the US competitor Uber. Careem’s core mission is “to simplify and improve the lives of people and build an awesome organization that inspires” (Careem, 2012), particularly focused on developing countries’ quality of living, and its internal strategy is designed in light of the SDGs and the United Nations Women Empowerment principles. Sanam Ahmed, Director of People Engagement at Careem’s subsidiary in Pakistan, indicated in an October 1, 2020 interview that “the beauty of Careem is that our entire purpose and values were already automatically aligned with the SDGs.”

Since its creation, Careem has engaged in internal investments through its human resource practices that promote diversity, flexible working hours, and extended parental leaves, thereby expanding local community job opportunities in their host countries. For example, Careem employs female drivers in countries in which there is a large gender opportunity gap, including Pakistan, Egypt, and Jordan. In 2018, upon women gaining the legal ability to drive in Saudi Arabia, Careem immediately hired female drivers, attracting thousands of applicants. By empowering women and providing them with job opportunities, Careem helps the families of their female employees and stimulates structural change towards more gender-egalitarian societies, addressing SDG 5 and SDG 1. As 70% of Careem’s riders are women, the introduction of female drivers demonstrated their commitment to customer satisfaction. By providing more secure mobility options in host countries for female clients, Careem furthers their brand loyalty and awareness and widens their client base. Careem’s job opportunities for women also contribute to SDG 8 on decent work by investing, for example, in work-life benefits for their drivers while providing them with career development and education opportunities.

Careem also invests externally to increase local wealth. In the UAE, Careem partnered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) to offer clients the opportunity to add AED3, equivalent to USD0.82, to their trip fare. Over USD350,000 has been raised to support over 300 refugee families through the UNHCR’s cash assistance program (Rung & Fomichenko, 2019), thus contributing directly to SDG 1 on poverty. These external investments contribute to local SDG advancement and have positive externalities for Careem’s ability to engage with their clients further and build its reputation as a sustainable firm that attracts repeat business.

Multinationals’ investments to increase health

Both global and local health issues are central to multinationals’ activities because multinationals often address health problems (Ahen, 2019). Multinational investments in host countries can contribute to not only shaping healthier lifestyles but also to creating living environments that help their stakeholders remain healthy (Salcito, Singer, Weiss, Winkler, Krieger, Wielga, & Utzinger, 2014). These investments advance two health-related SDGs. First, SDG 2 “Zero hunger: End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture.” There are still 690 million people, or 8.9% of the world population, who lack consistent access to food, up by 60 million in 5 years (United Nations, 2020a). Second, SDG 3 “Good health and well-being: Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.” A 31-year gap exists between the countries with the shortest and longest life expectancies, and at least 400 million people remain without healthcare protection (United Nations Development Programme, 2020c).

Internal investments by multinationals in host-country subsidiaries can provide major health-related contributions for their operations as well as for local communities. Multinationals can provide healthcare benefits and wellness programs to their employees (van Tulder, van Wijk, & Kolk, 2009), and extend the same benefits to employees’ families, especially their children, in host countries where a basic public healthcare system is deficient or non-existent. Such investments can help multinationals maintain a healthier and more committed workforce as well as retain and attract better employees (Maurer, 2014). This is not only important in emerging countries but also in advanced economies where part-time employees are rarely offered health insurance (Hartman, Rubin, & Dhanda, 2007). Moreover, multinationals can run training programs for procurement teams, suppliers, and other employees to strengthen knowledge and best practice in health and safety. For instance, multinationals can develop programs to assess the use of hazardous materials and to substitute such materials with safer alternatives within supply chains to ensure worker safety and engagement across their global value chains (Rondinelli & Berry, 2000a, b). Investments in occupational health and safety can help multinationals to not only better manage corporate image and reputational risk but also to increase supplier productivity, while creating positive externalities in the improvement of health in local communities where these suppliers operate. Companies can also collaborate with their upstream value chain suppliers, e.g., local farmers, by transferring best sustainable farm practices so that their operations increase yield and market appeal (Gold, Hahn, & Seuring, 2013), helping them to provide better produce to the multinational and improve the capacities of the local communities.

Lastly, multinationals can also improve health by customizing their products and services to serve their local consumers better. For instance, they can help combat hunger and malnutrition by making their products more affordable, while enriching their products with macro- and micronutrients, especially in regions where the population lacks such nutrients (Alexander, Yach, & Mensah, 2011; Yach, 2008). Such investments in products benefit multinationals from increased sales and profits in those regions where they provide affordable and healthy products and have large positive externalities in the health of the population. Thus, internal investments by the host-country subsidiary to improve its ability to compete also help achieve SDGs 2 and 3 in host-country communities.

Based on these arguments, we present the following propositions:

Proposition 5a:

Multinational health investments in a host-country subsidiary (e.g., providing healthcare benefits to their local value chain partners, designing more nutritional and affordable products for local consumers) have a positive impact on the subsidiary’s competitiveness (healthier workforce and consumer base).

Proposition 5b:

Multinational health investments in a host-country subsidiary (e.g., providing healthcare benefits to their local value chain partners, designing more nutritional and affordable products for local consumers) create positive health externalities that contribute to the host-country’s SDG agenda [reducing hunger (SDG 2) and improving local health (SDG 3)].

As part of external investment, multinationals can collaborate with local governments to address healthcare infrastructure deficiencies. They can invest in building hospitals and offering training programs to healthcare workers (Outreville, 2007). These investments enable host-country subsidiaries to build strong relationships with local government authorities and civil society in host countries and to reduce the potential discrimination that can create a liability of foreignness (Zaheer, 1995). Multinationals’ foreign direct investments can support local farmers’ access to land, which ensures access to food and increases food security in the host countries (Santangelo, 2018). Such investments may help multinationals gain market access for farmers in rural areas of developing countries. In a similar vein, multinationals can run food assistance programs to enhance food security in local communities struggling to secure daily meals for all their members (Yach, Feldman, Bradley, & Khan, 2010). Multinationals can also invest in providing subsidized fertilizer, certified seed, crop protection products, farm power, and rural transportation infrastructures to improve food security in local communities (Uduji & Okolo-Obasi, 2017). Lastly, companies may fund local non-profit or non-governmental organizations that work towards enhancing agricultural productivity and nutritious foods as part of the cross-sector collaboration. In turn, such collaboration may help host-country subsidiaries understand the nutritional conditions in their host countries and design products that better serve them, while firms can define the appropriate local strategies and establish product portfolios that will promote healthier diets while they increase sales and consumer awareness (Pant & Ramachandran, 2017).

Our arguments are encapsulated in the following propositions:

Proposition 6a:

Multinational health investments in host-country communities (e.g., building local hospitals and medical centers and providing food assistance and healthcare education programs to local people) have a positive impact on the host-country SDG agenda [improved community health by reducing hunger (SDG 2) and local health (SDG 3)].

Proposition 6b:

Multinational health investments in host-country communities (e.g., building local hospitals and medical centers and providing food assistance and healthcare education programs to local people) create positive health externalities for the host-country subsidiary (securing future access to a healthier workforce and consumer base).

Unilever, the British–Dutch consumer goods multinational, shows how a multinational not only contributes to improving health in host-country communities but also benefits from making investments consistent with the SDG agenda. For Unilever, “the SDGs are a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to create a better world” (Unilever, 2015). Based on its global scale and reach, Unilever invests internally in a global employee health program, Lamplighter, to improve the nutrition, fitness, and mental resilience of its employees. The program includes health risk appraisals alongside exercise, nutrition, and mental resilience to help employees improve their health and well-being. In 2019, there were 81,000 Unilever employees in 75 countries, including China and India, who were enrolled in the program, which has helped improve employees' health while enhancing productivity and reducing healthcare costs. Moreover, Unilever invested €85 million to launch the Unilever Foods Innovation Center at Wageningen University in the Netherlands. The Center works on developing more plant-based ingredients and meat alternatives, nutritious foods, and sustainable food packaging, which has paved the road to improved sustainable food production systems and resilient agricultural practices (SDG 2) and reduced illness from non-communicable diseases (SDG 3). In the remarks of Unilever’s former CEO, Paul Polman, during his talk at New York University on October 8, 2020, “burnt-out people are not going to fix a burnt-out planet.”

Unilever also undertakes external health investments in local communities. It runs several health programs for handwashing, safe drinking water, sanitation, oral health, self-esteem, and skin-healing to ensure a lasting change in the hygiene of people across the globe (Unilever, 2020). For example, Lifebuoy, Unilever’s hygiene soap brand, has implemented one of the world’s most extensive handwashing programs, and has designed and piloted mobile technology that has been found to change handwashing behavior. The campaign increased the frequency of handwashing with soap by 50% among participants exposed to the campaign. Another Lifebuoy program is Mobile Doctarni, which is aimed at reaching women in rural areas in India, providing mothers with free, easily accessible advice about their child’s health. In 2019, Unilever announced a partnership between Lifebuoy and a non-governmental organization, The Power of Nutrition, to reach 2.7 million mothers in India through Mobile Doctarni. As part of the partnership, Unilever is targeted to create a model of Mobile Doctarni that can be replicated in other locations. The Lifebuoy program addresses diseases linked to sanitation and water, which is key to contributing to the host-country SDG agenda by improving health in the local communities as well as among Unilever’s employee and consumer base.

Multinationals’ Investments that Address the SDGs to Reduce Negative Externalities

We also propose that multinationals can design investments that reduce the negative externalities created from their activities and contribute to achieving the SDGs. Multinationals, like any other company, have the potential to generate negative externalities in host countries where they operate as a result of their normal production and distribution activities (Meyer, 2004). We are not referring to the competitive effects of crowding out local competitors as a result of the higher competitiveness of the subsidiaries (Spencer, 2008), but to the pollution and waste generated from manufacturing, or the environmental degradation for companies in natural resources. The usual way to address these negative externalities is for the government to establish regulations that prohibit certain activities, such as dumping toxic waste, increase the cost of the negative externalities by requiring cleanup, force companies to compensate those harmed, or redesign property rights to align incentives (Arrow, 1969; Coase, 1960; Laffont, 1993). Such management of negative externalities through regulation has limitations because, in many countries, governments do not have the appropriate rules in place or are ineffective in the implementation of regulations and the prosecution of misbehavior (Geddes, 1994; Khanna & Palepu, 2010; Migdal, 1988).

Multinationals may want to reduce negative externalities voluntarily. They can adopt non-state market-driven standards to reduce the regulatory sanctions that are imposed for harming local communities (Cashore, 2002; Christmann & Taylor, 2002; King & Lenox, 2000). This also allows the company to avoid breaking the social contract with local communities and to prevent eliciting negative reactions to their operations and future expansions. Negative externalities can lead firms to collaborate with others to establish self-regulation and to reduce external pressures (Barnett & King, 2008). This view of addressing negative externalities to prevent harm to the multinationals’ operations and reputation is the traditional approach that should be rethought.

An alternative to this traditional approach is a more proactive one in which the multinational aims to build its competitive advantage based on its ability to curtail negative externalities. By implementing superior standards in comparison to domestic competitors in the avoidance of negative externalities (King & Shaver, 2001), the multinational can be perceived as a better company by host governments and citizens, facilitating its innovativeness and the sale of its products (Husted & Allen, 2007). Preventing negative externalities can also be a way for the company to attract better employees, especially educated, younger ones who seem to be more concerned about the impact of companies on society (Collier & Esteban, 2007). This second proactive approach to the management of negative externalities is the one that we follow in this article. We argue for the integration of the SDGs within segments of the value chain in which multinationals tend to have a negative impact. In this way, they can reconsider how their investments may reduce negative externalities on local communities. By incorporating the impact of negative externalities into their decision-making, multinationals can benefit from the avoidance of costly fines in the future and by differentiating themselves from competitors by embracing superior standards.

Consequently, we propose SDG groupings linked to reducing negative externalities into three main themes: the overuse of natural resources, harm to social cohesion, and overconsumption. We now examine each of the themes and their relationship to the SDGs in turn. Figure 1 illustrates these groups.

Multinationals’ investments to reduce the overuse of natural resources

The overuse of natural resources at an unchecked rate has led to direct negative externalities related to the depletion and degradation of renewable and non-renewable resources, such as water, fertile soils, and forests. Natural resource exploitation generates a vast resource deficit, such that at least 1.5 Earths would be needed to regenerate the natural resources that humans use (World Wide Fund for Nature, 2014). The overuse of natural resources has also resulted in indirect negative externalities, like water, air, and soil pollution, and climate change caused by the increasing concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere. Resource extraction and processing contribute to half of all greenhouse gas emissions worldwide and about 90% of biodiversity loss (United Nations Environment Programme, 2019). As a result of human activity, global temperature has increased by 2.0 degrees Fahrenheit since 1880, and sea levels have risen by eight inches in the last century (NASA, 2020).

Multinationals can be part of the solution by incorporating their impact on natural resources into their decision-making processes. We propose that multinational efforts at reducing the overuse of natural resources can foster positive change to achieve four interconnected SDGs: SDG 6 “Clean water and sanitation: Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all;” SGD 7 “Affordable and clean energy: Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all;” SDG 13 “Climate action: Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts;” and SDG 15 “Life on land: Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss.”

Multinationals can direct their host-country subsidiaries to mitigate the excessive use of natural resources. Host-country subsidiaries can consider upgrading operations, technology, and processes across their subsidiary operational sites to reduce the amount of virgin natural resources required to manufacture products (Hills & Welford, 2005; Marcon, de Medeiros, & Ribeiro, 2017). Multinationals can also assist subsidiaries and suppliers in host countries with improving energy efficiency and increasing renewable energy use to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions at operational sites (Eskeland & Harrison, 2003; Kolk & Pinkse, 2008). Multinationals can invest in enhancing resource management practices by identifying subsidiary and supplier operational sites exposed to risks associated with natural resource shortages and climate-related hazards and by assessing their resource management strategies in the context of local communities (D’Amato, Wan, Li, Rekola, & Toppinen, 2018). These internal investments can benefit multinationals by reducing operational costs and environmental regulatory compliance costs in host countries while reducing their overall environmental footprint. In turn, such internal investments can reduce negative externalities associated with the overuse of natural resources in host communities, helping them to improve their use while preserving natural resources so that they can be used in a sustainable manner that contributes to the present and future economic development of their host communities (Hilborn, Walters, & Ludwig, 1995). In this way, the internal investments can help the host-country subsidiary and concurrently contribute to the solution of the SDGs, including water withdrawal (SDG 6), fossil fuel usage (SDG 7), greenhouse gas emissions and climate-related natural disasters (SDG 13), and harm to land, forests, and territorial ecosystems (SDG 15).

These ideas support the following propositions:

Proposition 7a:

Multinational investments to reduce the overuse of natural resources in a host-country subsidiary (e.g., reducing the use of virgin natural resources, transitioning toward renewable energy usage) have a positive impact on the subsidiary’s competitiveness (reducing operational and environmental regulatory compliance costs).

Proposition 7b:

Multinational investments to reduce the overuse of natural resources in a host-country subsidiary (e.g., reducing the use of virgin natural resources, transitioning toward renewable energy usage) mitigate negative externalities from the overuse of natural resources that contribute to the host-country SDG agenda [reducing water withdrawal (SDG 6), reducing fossil fuel usage (SDG 7), reducing greenhouse gas emissions and climate-related natural disasters (SDG 13), and reducing harm to land, forests, and territorial ecosystems (SDG 15)].

Multinational external investments also have the potential to tackle the negative externalities generated by the excessive use of natural resources in host-country communities and indirectly help the competitiveness of host-country subsidiaries. Multinationals can invest in infrastructure in underserved host countries to enhance water or energy access (Akter, Fu, Bremermann, Rosa, Nattrodt, Väätänen, Teplov, & Khairullina, 2017), to restore polluted soil or waters for local community members, and to offer training programs to local entrepreneurs devoted to supplying renewable energy in the host-country communities. They can partner with local communities to ensure that investments in water infrastructure are successful by building local capacity to manage infrastructure (Nwankwo, Phillips, & Tracey, 2007). These external investments can mitigate unequal access to clean water (SDG 6) and energy (SDG 7), greenhouse gas emissions (SDG 13), and degraded land and soil (SDG 15). Sequentially, these external investments can also benefit subsidiaries by ensuring future natural resource availability and quality to avoid disruption to their manufacturing and distribution networks in the host country (Bass & Chakrabarty, 2014). Also, partnerships with local communities can serve as knowledge platforms for local sustainability issues related to the overuse of natural resources, especially where these are essential for their upstream value chain operations (Boiral & Heras-Saizarbitoria, 2017).

The following propositions summarize these ideas:

Proposition 8a:

Multinational investments to reduce the overuse of natural resources in host-country communities (e.g., building infrastructure to improve water and energy access, offering renewable energy training programs to local entrepreneurs) have a positive impact on the host-country SDG agenda [mitigating unequal access to clean water (SDG 6), mitigating unequal access to energy (SDG 7), mitigating greenhouse gas emissions (SDG 13), and mitigating degraded land and soil (SDG 15)].

Proposition 8b:

Multinational investments to reduce the overuse of natural resources in host-country communities (e.g., building infrastructure to improve water and energy access, offering renewable energy training programs to local entrepreneurs) reduce negative externalities for the host-country subsidiary (securing future access to natural resources, avoiding disruption in their local manufacturing and distribution networks).

Schneider Electric, a French multinational providing energy and digital automation solutions with operations in over 100 countries, illustrates how multinationals can reinvent themselves to reduce negative externalities in the overuse of natural resources and contribute to host-country SDG agendas. Established in 1836 with iron, steel, and armament operations, it divested from steel and focused on electricity in the 1980s and 1990s. By 2010, the company refocused on smart grid applications to become a pioneer in digitalization and renewables to increase efficiency and sustainability in businesses, buildings, and cities. Nicolas Plain, SDG Transformation Leader at Schneider Electric, emphasized, on September 4, 2020, that “the SDGs are extremely important for all our core operations because they help us not to forget any potential side effects that our projects create in society.”

Schneider Electric has made vast internal investments in developing technologies and solutions supporting the more efficient and sustainable use of natural resources in their operations. By 2020, 80% of their energy needs were satisfied with renewables at all their sites, and they expect to be a 100% renewable energy company and achieve a net-zero carbon impact in all subsidiary operations by 2030. To achieve this, the company has invested in photovoltaic roofs and solar microgrids across their worldwide sites (e.g., India, Thailand, France, and the US) and assisted subsidiaries in purchasing renewable energy, as in the case of the 2019 Power Purchasing Agreement signed for their facilities in Mexico (Schneider Electric, 2020a). For example, the photovoltaic roof installed in 2017 on its manufacturing facility in Gujarat, India, covers more than 50% of its energy needs, thereby reducing energy costs by 20–25% and greenhouse emissions by 1,018 tons of CO2 annually (the equivalent of planting 50,000 trees). Schneider has also developed applications such as EcoStruxure for more efficient use of energy, water, land, and minerals in industrial processes, which also cut operational costs and increased productivity and revenue, not only in their operations but also among their value chain partners. One example is the digital energy efficiency systems installed in their Mumbai Smart Distribution Center, which is expected to save 10–12% in energy and to enhance logistics efficiency by 5% (Schneider Electric, 2020b).

Regarding external investments in host-country communities, since 2012, Schneider Electric has installed Villaya solar water pumps to supply drinking water to off-grid communities in India and several African countries (Schneider Electric, 2020c). The company has developed the Schneider Electric Energy Access program to target 350 million people without energy access in India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Indonesia, and the Philippines, and to provide new solutions for off-grid energy access for communities in Asia and Africa (Schneider Electric, 2020c). Schneider Electric has supplied Villaya Agri-Business multi-energy power stations to provide solar electricity and heat for irrigation, lighting, fish farming, and agricultural transformation, benefiting 100,000 people in African communities and 30,000 female farmers in Asian communities. As of 2019, through their Access to Energy Training & Entrepreneurship Program, more than 400,000 underprivileged people have already benefited from the foundation’s training programs in energy management and renewable energies (Schneider Electric, 2020c). Further, the company has provided technical solar energy training to female entrepreneurs in Mali, Senegal, and Niger. Lastly, Schneider Electric joined the Global Footprint Network to partner for recycling and reuse, and to promote using resources in a way that respects the Earth’s ability to replenish them. Such investments have subsequently strengthened Schneider’s license to operate in its host countries, while receiving global reputation awards, such as being among the World’s Most Admired Companies in 2018 and 2019 (Fortune, 2020).

Multinationals’ investments to reduce harm to social cohesion

Social cohesion, which is vital to the well-being of a country, refers to both the absence of social conflict and the presence of social bonds and institutions that resolve conflict as well as civil society organizations that bridge social divisions (Kawachi & Berkman, 2000). The SDGs can help achieve social cohesion by providing a clear, alternative basis for controlling conflict and violence, the fundamental challenge of any society (North, Wallis, Webb, & Weingast, 2012). Many developing countries control violence and conflict by limiting access to the economic and political sectors to the ruling elites (North, Wallis, & Weingast, 2009). As a result, elites obtain rents through their control of access to a country’s economic and political life in return for abstaining from the use of violence (North et al., 2009). The SDGs provide a different vision of reducing social tension and threats to social cohesion through an open society, which reduces inequality, fosters inclusion, and works through partnerships. Hence, social cohesion, as the reduction of social conflict and the strengthening of social bonds and peaceful conflict resolution, is related to four SDGs: SDG 10 “Reducing inequality: Reduce inequality within and among countries;” SDG 11 “Sustainable cities and communities: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable;” SDG 16 “Peace, justice, and strong institutions: Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels;” and SDG 17 “Partnerships for the goals: Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development.” Reducing inequality and fostering sustainable, inclusive communities is key to alleviating social conflict, while developing just and strong institutions through partnerships helps to generate strong social bonds and to resolve conflict peacefully. According to the United Nations (2020b), corrupt practices and tax evasion due to weak institutions foster inequality, amounting to USD1.26 trillion per year in underdeveloped countries. If this money were used to help the poor, it would push the income of people with less than USD1.25 a day to above USD1.25 for at least six years (United Nations, 2020b).

Multinationals’ internal investments can help reduce barriers to social cohesion by deliberately opening access to non-elites in host-country subsidiaries. For example, companies can employ well-qualified candidates, including the clients of the patronage networks of elites, ensuring that the best candidates are hired rather than showing favoritism, which may be preferred in the host country (Allès, 2012; Donaldson & Dunfee, 1994). Multinationals can also invest in controlling corrupt practices in subsidiaries and business partners to promote the rule of law in host countries (see a review in Cuervo-Cazurra, 2016). Such internal investments in ethical practices produce advantages for multinationals in assuring that companies hire the most qualified employees and work with the most competitive value chain partners. At the same time, these investments create positive demonstration effects for the society at large, as employees and partners learn best practices from multinationals that adhere to high ethical standards and transmit them to their host-country context (Fisher, 2004; Inkeles, 1975; James, 1987). Hence, these investments can reduce negative externalities generated by social conflict (Gonzalez, Layrisse, & Lozano, 2012). As a result, these internal investments help address relative income inequality (SDG 10), exclusionary development of cities and communities (SDG 11), bribery and corruption (SDG 16), and harm to implementing partnerships for effective capacity-building in host countries (SDG 17).

Thus, we formulate the following propositions:

Proposition 9a:

Multinational investments to reduce harm to social cohesion in a host-country subsidiary (e.g., widening access to employment, refraining from corruption) have a positive impact on the subsidiary’s competitiveness (gaining more qualified and competitive value chain partners).

Proposition 9b:

Multinational investments to reduce harm to social cohesion in a host-country subsidiary (e.g., widening access to employment, refraining from corruption) mitigate negative externalities that harm social cohesion that contribute to the host-country SDG agenda [reducing inequality (SDG 10), making cities and human settlements more inclusive (SDG 11), promoting peaceful and inclusive societies (SDG 16) and strengthening partnerships for sustainability (SDG 17)].

Multinationals can also reduce harm to social cohesion by making external investments in host-country communities that facilitate the reduction of negative externalities while contributing to the host-country subsidiaries’ competitiveness. Partnering with grassroots non-governmental organizations is more likely to help the disadvantaged and to improve social cohesion, because they are “people doing real work, not just talking” (Spires, 2012). When partnering with elite non-governmental organizations rather than grassroots ones, multinationals can unwittingly contribute to sustaining elites and their privileges, thus reducing social cohesion (Spires, 2011). Multinationals can also target training externally, beyond their employees, to socially disadvantaged groups, such as ex-guerrilla fighters and former drug traffickers, to contribute to the reinsertion of these groups into society (Gonzalez et al., 2012). Such externally focused training reduces social conflict in host countries. These external investments can reduce barriers to participation in economic activities (SDG 10), obstacles to representation and voice for the underserved population in cities and communities (SDG 11), conflict and violence (SDG 16), and ineffective public–private and civil society collaborations (SDG 17). External investments also generate positive externalities for the firm that benefits from a more peaceful society, which is more attractive for potential employees and business partners, spurring greater creativity and innovation (Florida, 2002, 2003). By increasing the quality of life for employees and stakeholders located in host countries, multinationals are better able to alleviate the social unrest that negatively affects their business activities in those regions.

We summarize these ideas in the following propositions:

Proposition 10a:

Multinational investments to reduce harm to social cohesion in host-country communities (e.g., partnering with grassroots non-governmental organizations, providing training to socially disadvantaged groups) have a positive impact on the host-country SDG agenda [reducing inequality (SDG 10), making cities and settlements more inclusive (SDG 11), promoting peaceful and inclusive societies (SDG 16), and strengthening partnerships for sustainable development (SDG 17)].

Proposition 10b:

Multinational investments to reduce harm to social cohesion in host-country communities (e.g., partnering with grassroots non-governmental organizations, providing training to socially disadvantaged groups) reduce negative externalities for the host-country subsidiary (reducing social unrest, thus attracting potential employees and business partners to more peaceful areas).

The case of a Mexican multinational, Coca-Cola Femsa, illustrates how firms can help reduce harm to social cohesion through internal and external investments. Coca-Cola Femsa is the largest bottler and distributor of Coca-Cola products in Latin America, and a subsidiary of the US firm Coca-Cola. In its 2019 sustainability report (Femsa, 2019), the firm describes initiatives to be a more diverse and inclusive workplace by actively employing people without regard to disability, gender, sexual orientation, culture, or age. They note how this diversity and inclusion policy seeks to benefit the work environment of the entire firm, including in host-country locations. Such internal investments are likely to boost employee morale and productivity as well as mitigate negative externalities engendered by social conflict by reducing unequal employment opportunity (SDG 10), exclusionary cities and communities (SDG 11), discriminatory hiring practices (SDG 16), and barriers to implementing effective capacity-building in host countries (SDG 17).