Abstract

Background

The pre-operative systemic inflammatory response (SIR) measured using an acute-phase-protein-based score (modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS)) or the differential white cell count (neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR)) demonstrates prognostic significance following curative resection of colon cancer. We investigate the complementary use of both measures to better stratify outcomes.

Methods

The effect on survival of mGPS and NLR was examined using uni/multivariate analysis (UVA/MVA) in patients undergoing curative surgery for colon cancer. The synergistic effect of these scores in predicting OS/CSS was examined using a Systemic Inflammatory Grade (SIG).

Results

One thousand seven hundred and eight patients with TNM-I–III colon cancer were included. On MVA both mGPS and NLR were significant for OS (HR 1.16/1.21, respectively). Three-year survival stratified by mGPS was 83–58%(TNM-I–III), 87–65%(TNM-II) and 75–49%(TNM-III), and by NLR was 84–62%(TNM-I–III), 88–69%(TNM-II) and 77-49%(TNM-III). When mGPS and NLR were combined to form an overall SIG 0/1/2/3/4, this stratified 3-year OS 88%/84%/76%/65%/60% and CSS 93%/90%/82%/73%/70%, respectively (both p < 0.001). SIG stratified OS 93–68%/82–48% and CSS 97–80%/86–58% in TNM Stage II/III disease, respectively (all p < 0.001).

Conclusions

The present study shows that the pre-operative SIR in patients undergoing curative surgery for colon cancer is best measured using a SIG utilising mGPS and NLR.

Subject terms: Prognostic markers, Colon cancer, Colon cancer

Background

Approximately 1.2 million new cases of colon cancer are diagnosed globally each year with colon cancer accounting for approximately 500,000 deaths annually.1 Within the United Kingdom, TNM Stage II and Stage III disease each account for approximately 25% of new cases at diagnosis.2 Long-term outcomes vary significantly suggesting that estimating prognosis based on overall TNM stage alone is suboptimal.

The presence of an increased pre-operative systemic inflammatory response is a new, well-documented prognostic domain associated with poorer short- and long-term outcomes including overall and cancer-specific survival, both independently and when combined with TNM stage.3–7 Indeed, the pre-operative systemic inflammatory response has been termed as the tip of the cancer iceberg.8 However, to date this approach has been perhaps underutilised in routine clinical practice.

The systemic inflammatory response can be quantified through cumulative scores or composite ratios, either using acute-phase proteins or the differential white cell count. Currently the most common scoring methods are the modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS)9 and neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR). The individual prognostic value of these scores has been summarised in several recent studies including two systematic reviews and meta-analyses.5,10 A further observational study3 that directly compared the use of different composite ratios and cumulative scores found these to be of prognostic value independent of TNM stage in patients undergoing curative surgery for colon cancer.

More recently, a Japanese study11 by Inamoto and co-authors reported the possibility of more accurately stratifying overall, cancer-specific and disease-free survival by combining two different measures of the systemic inflammatory response (GPS and NLR). However, this study was in a relatively small cohort (n = 448) and included both colon and rectal cancers.

While different scoring methods can be utilised separately to quantify prognosis, a combination of scores may provide additional prognostic value in patients undergoing curative resection for colon cancer. The present study aims to evaluate the potential to better stratify survival through the use of both the most common measure of the acute-phase protein response (mGPS) and the most common measure of the differential white cell count (NLR) within a large regional cohort of patients undergoing curative resections for colon cancer.

Methods

The West of Scotland Colorectal Cancer Managed Clinical Network (MCN) maintains a prospectively collected dataset of all patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer in the West of Scotland and contains basic clinicopathological data. This covers four health boards (Ayrshire and Arran, Forth Valley, Lanarkshire and Greater Glasgow and Clyde) and includes almost half of the population of Scotland. Cancer registration data within Scotland is recognised to be of high quality.12,13 These patients are usually followed up for a period of 3–5 years and receive treatment in line with national guidelines.

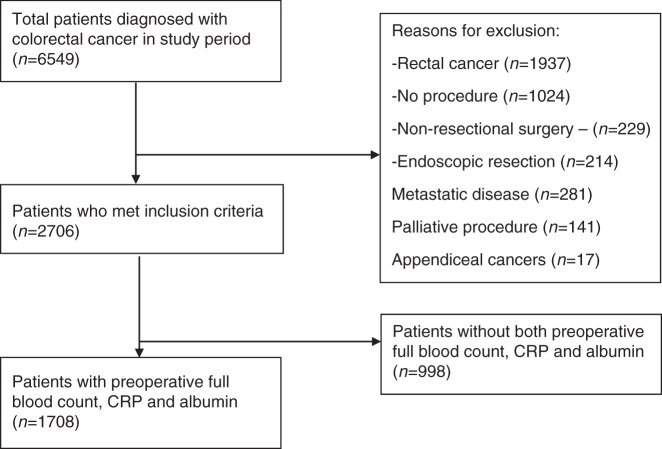

Patients diagnosed with Colon Cancer between January 2011 and December 2014 within the West of Scotland were identified from the MCN database. Patients undergoing curative surgery for either an elective or an emergency diagnosis of TNM Stage I–III colon cancer were included. Emergency presentations were defined as unplanned admissions requiring investigation and definitive treatment within 72 h of hospital admission. Those patients with Stage IV disease, rectal (including rectosigmoid) tumours, patients with macroscopically involved margins (R2 resections) and those patients undergoing local/palliative procedures were excluded. Finally, patients who did not have the laboratory data to calculate a minimum of both the mGPS and NLR were excluded. This is shown diagrammatically in Fig. 1. Survival was updated through data linkage to the National Records of Scotland (NRS) deaths data until the end of 2018.

Fig. 1. Case selection.

Flow chart of case selection including inclusion/exclusion criteria.

Socioeconomic deprivation has been stratified using the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD). Tumours were staged using the TNM classification system. When appropriate blood results were available, the pre-operative systemic inflammatory response was calculated using the modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS) and neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as shown in Table 1. NLR was classified as 0 (NLR < 3), 1 (NLR 3–5) or 2 (NLR > 5). Pre-operative blood results were regarded as the most recent set of pre-operative blood results, in the case of elective patients within 1 month prior to surgery and in the case of emergency patients from admission to hospital. Patients were considered to have received adjuvant chemotherapy if adjuvant therapy was commenced regardless of chemotherapeutic agent/dose/number of cycles received. Overall survival was calculated from the date of surgery until date of death of any cause. Cancer-specific survival was defined as the time from date of surgery until date of death due to recurrent/metastatic colon cancer. A death was considered a result of Colon Cancer if this was the primary cause of death on the death certificate in accordance with rules set out by the World Health Organisation.14 All patients were followed up for a minimum of 3 years following surgery.

Table 1.

Measurements of the systemic inflammatory response (SIR)—mGPS, NLR, SIG.

| mGPS | Score |

| C-reactive protein ≤ 10 | 0 |

| C-reactive protein > 10 and albumin ≥ 35 | 1 |

| C-reactive protein > 10 and albumin < 35 | 2 |

| NLR | |

| NLR < 3 | 0 |

| NLR 3–5 | 1 |

| NLR > 5 | 2 |

| Systemic Inflammatory Grade (SIG) | |

| SIG 0 | mGPS 0 and NLR < 3 |

| SIG 1 |

mGPS 0 and NLR 3–5 or mGPS 1 and NLR < 3 |

| SIG 2 |

mGPS 0 and NLR > 5 or mGPS 2 and NLR < 3 or mGPS 1 and NLR 3–5 |

| SIG 3 |

mGPS 1 and NLR > 5 or mGPS 2 and NLR 3–5 |

| SIG 4 | mGPS 2 and NLR > 5 |

mGPS modified Glasgow Prognostic Score, NLR neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio, SIG Systemic Inflammatory Grade.

Ethical approval was granted for this project from the Public Benefit and Privacy Panel (NHS Scotland) for Health and Social Care (PBPP) and Caldicott Guardian Approval.

Statistical analysis

The relationship between clinicopathological characteristics including measurements of the systemic inflammatory response and overall or cancer-specific survival was examined using Cox’s proportional hazards model to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs). Variables with a p-value of <0.1 on univariate analysis were entered into a multivariate model using the backwards conditional method in which variables with a significance of p < 0.10 were removed from the model in a stepwise fashion. The association between co-variates with more than two levels and overall survival were visually inspected using Kaplan–Meier curves confirming linearity with overall survival therefore analysis using categorical co-variates was not carried out.

Three-year overall and cancer-specific survival was carried out using a life table approach and results were displayed as percentage 3-year survival and percentage standard error. Where there were fewer than 10 patients in a group survival analysis was not carried out due to potential inaccuracies resulting from small sample size. On survival analysis, statistical significance was calculated using the log rank test. Outcomes have been displayed graphically using a Kaplan–Meier curve.

Statistical analysis was carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows Version 25 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York, USA). For survival stratified by SIG, a p-value of <0.01 was considered significant due to the number of statistical comparisons.

Results

All patients

As shown in Fig. 1, 6549 patients were identified who had been diagnosed with colorectal cancer in the West of Scotland from January 2011 to December 2014, 2706 of whom had underwent a curative resection for TNM Stage I–III colon cancer. After exclusion of those patients who had insufficient pre-operative blood tests carried out to calculate both the modified Glasgow Prognostic Score (mGPS) and neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR), 1708 patients remained who were included in this study.

The majority of patients were aged >65 (70%), presented electively (76%) and underwent an R0 resection (97%) for node negative (TNM-I–II) disease (61%). 58%/19%/23% of patients had a pre-operative mGPS of 0/1/2 and 45%/31%/24% of patients had a pre-operative NLR of <3/3–5/>5, respectively. The median follow-up between date of surgery and death of death/censoring was 58 months (range 0–95 months). When only survivors were included, the median follow-up was 70 months (range 43–95 months). Sixty-two patients (4%) died within 30 days of surgery. After exclusion of postoperative deaths there were 588 deaths during follow-up of which 59% were cancer related.

Survival analysis

Survival analysis is shown in Table 2. On univariate analysis: age, site, mode of presentation, ASA, TNM Stage, margin involvement, adjuvant chemotherapy administration, smoking status, mGPS, NLR (all p < 0.001) and SIMD classification (p = 0.007) were associated with overall survival. When those factors significant on univariate analysis were entered into the multivariate model: age, ASA, TNM Stage, margin involvement, adjuvant chemotherapy, smoking status, NLR, (all p < 0.001) mGPS (p = 0.011) and mode of presentation (p = 0.017) remained significant for overall survival. It was of particular interest that both mGPS and NLR retained independent significance.

Table 2.

The effect of clinicopathological factors including the pre-operative systemic inflammatory response (measured by both mGPS and NLR) on overall survival—UVA and MVA (30-day mortality included).

| Variable | Number of patients (n).Total.(Breakdown) | UVA | MVA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | ||

| Age (<65/65–74/>74) | n = 1708 (518/567/623) | 1.69 (1.52–1.87) | <0.001 | 1.31 (1.15–1.49) | <0.001 |

| Sex (male/female) | n = 1708 (876/832) | 0.93 (0.80–1.09) | 0.374 | — | — |

| Site (right/left) | n = 1691 (906/785) | 0.72 (0.62–0.84) | <0.001 | — | 0.786 |

| SIMD classification (1/2/3/4/5) | n = 1708 (498/366/310/258/276) | 0.93 (0.88–0.98) | 0.007 | — | 0.502 |

| Mode of presentation (ēlective/emergency) | n = 1708 (1297/411) | 2.10 (1.79–2.47) | <0.001 | 1.29 (1.05–1.59) | 0.017 |

| ASA (1/2/3/4/5) | n = 1623 (132/848/561/80/2) | 1.93 (1.72–2.15) | <0.001 | 1.48 (1.29–1.69) | <0.001 |

| TNM stage (1/2/3) | n = 1708 (291/757/660) | 1.74 (1.54–1.95 | <0.001 | 1.82 (1.56–2.13) | <0.001 |

| Margin involvement (negative/positive) | n = 1695 (1641/54) | 3.23 (2.42–4.57) | <0.001 | 2.50 (1.75–3.56) | <0.001 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy (yes/no) | n = 1701 (1156/545) | 0.64 (0.54–0.77) | <0.001 | 0.55 (0.43–0.70) | <0.001 |

| Smoking (non-smoker/ex-smoker/smoker) | n = 1596 (756/607/233) | 1.23 (1.10–1.37) | <0.001 | 1.19 (1.05–1.35) | 0.006 |

| mGPS (0/1/2) | n = 1708 (991/330/387) | 1.59 (1.46–1.74) | <0.001 | 1.16 (1.04–1.30) | 0.011 |

| NLR (<3/3–5/>5) | n = 1708 (774/525/409) | 1.55 (1.41–1.70) | <0.001 | 1.21 (1.08–1.36) | 0.001 |

SIMD Scottish Index of Multiple Derivation, ASA American Society of Anaesthetists Grade, mGPS modified Glasgow prognostic Score, NLR neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio.

The individual and complementary use of mGPS and NLR in stratifying 3-year overall survival in both the whole cohort of patients and when subclassified into individual TNM stages is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Three-year overall survival displayed as percentage survival and percentage standard error stratified by mGPS and NLR in all TNM Stages (3a), TNM Stage II (3b) and TNM Stage III (3c) colon cancer.

| (a)—All TNM stages | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLR < 3 | NLR 3–5 | NLR > 5 | Total | p | |||||

| n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | ||

| mGPS 0 | 571 | 87% (SE 1%) | 300 | 82% (SE 2%) | 120 | 72% (SE 4%) | 991 | 83% (SE 1%) | <0.001 |

| mGPS 1 | 111 | 84% (SE 3%) | 115 | 77% (SE 4%) | 104 | 64% (SE 5%) | 330 | 75% (SE 2%) | 0.009 |

| mGPS 2 | 92 | 68% (SE 5%) | 110 | 58% (SE 5%) | 185 | 54% (SE 4%) | 387 | 58% (SE 3%) | 0.006 |

| Total | 774 | 84% (SE 1%) | 525 | 76% (se 2%) | 409 | 62% (SE 2%) | |||

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.001 | |||||||

| (b)—TNM stage II disease | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLR < 3 | NLR 3–5 | NLR > 5 | Total | p | |||||

| n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | ||

| mGPS 0 | 209 | 91% (SE 2%) | 139 | 83% (SE 3%) | 60 | 77% (SE 5%) | 408 | 87% (SE 2%) | 0.018 |

| mGPS 1 | 45 | 91% (SE 4%) | 46 | 85% (SE 5%) | 46 | 78% (SE 6%) | 137 | 85% (SE 3%) | 0.248 |

| mGPS 2 | 54 | 72% (SE 6%) | 62 | 65% (SE 6%) | 96 | 60% (SE 5%) | 212 | 65% (SE 3%) | 0.021 |

| Total | 308 | 88% (SE 2%) | 247 | 79% (SE 3%) | 202 | 69% (SE 3%) | |||

| p = 0.031 | p = 0.011 | p = 0.004 | |||||||

| (c)—TNM stage III disease | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NLR < 3 | NLR 3–5 | NLR > 5 | Total | p | |||||

| n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | ||

| mGPS 0 | 198 | 80% (SE 3%) | 103 | 70% (SE 5%) | 38 | 58% (SE 8%) | 339 | 75% (SE 2%) | 0.005 |

| mGPS 1 | 54 | 76% (SE 6%) | 51 | 67% (SE 7%) | 54 | 50% (SE 7%) | 159 | 64% (SE 4%) | 0.034 |

| mGPS 2 | 34 | 62% (SE 8%) | 43 | 49% (SE 8%) | 85 | 44% (SE 5%) | 162 | 49% (SE 4%) | 0.348 |

| Total | 286 | 77% (SE 2%) | 197 | 64% (SE 3%) | 177 | 49% (SE 4%) | |||

| p = 0.014 | p = 0.010 | p = 0.276 | |||||||

Results displayed at % 3-year survival and % Standard error.

mGPS modified Glasgow Prognostic Score, NLR neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio, n number of patients.

Within the whole patient cohort (Table 3a), when overall survival was stratified using mGPS 3-year survival ranged from 83% (mGPS 0) to 58% (mGPS 2). When NLR was used it ranged from 84% (NLR < 3) to 62% (NLR > 5). When a combination of mGPS/NLR was used overall survival ranged from 87% (mGPS 0, NLR < 3) to 54% (mGPS 2, NLR > 5). When NLR < 3 was stratified by mGPS (0/1/2) (n = 571/111/92), 3-year survival was 87%/84%/68% (p < 0.001), for NLR 3–5 (n = 300/115/92) was 82%/77%/68% (p < 0.001) and for NLR > 5 (n = 120/104/185) was 72%/64%/54% (p = 0.001).

Within the TNM Stage I cohort (Supplementary Table 1), when overall survival was stratified using mGPS 3-year survival ranged from 91% (mGPS 1) to 77% (mGPS 2). When NLR was used it ranged from 94% (NLR 3–5) to 87% (NLR > 5). Due to small numbers (n < 10) within groups it was not possible to stratify overall survival through combined use of mGPS and NLR.

Within the TNM Stage II cohort (Table 3b), when overall survival was stratified using mGPS 3-year survival ranged from 87% (mGPS 0) to 65% (mGPS 2). When NLR was used it ranged from 88% (NLR < 3) to 69% (NLR > 5). When a combination of mGPS/NLR was used overall survival ranged from 91% (mGPS 0, NLR < 3) to 60% (mGPS 2, NLR > 5). When NLR < 3 was stratified by mGPS (0/1/2) (n = 209/45/54), 3-year survival was 91%/91%/72% (p = 0.031), for NLR 3–5 (n = 139/46/62) was 83%/85%/65% (p = 0.011) and for NLR > 5 (n = 60/46/96) was 77%/78%/60% (p = 0.004).

Within the TNM Stage III cohort (Table 3c), when overall survival was stratified using mGPS 3-year survival ranged from 75% (mGPS 0) to 49% (mGPS 2). When NLR was used it ranged from 77% (NLR < 3) to 49% (NLR > 5). When a combination of mGPS/NLR was used overall survival ranged from 80% (mGPS 0, NLR < 3) to 44% (mGPS 2, NLR > 5). When NLR < 3 was stratified by mGPS (0/1/2) (n = 198/54/34), 3-year survival was 80%/76%/62% (p = 0.014), for NLR 3–5 (n = 103/51/43) was 70%/67%/49% (p = 0.010) and for NLR > 5 (n = 38/54/85) was 58%/50%/44% (p = 0.276).

Creation of systemic inflammatory grade (SIG)

Within the present study NLR has been stratified into <3, 3–5 and >5 and assigned a respective score of 0/1/2 and mGPS 0/1/2. When mGPS (0–2) and NLR (0–2) were added cumulatively to form a combined SIG this classified patients into 5 grades from 0–4 (Table 1). Both mGPS and NLR had similar hazard ratios (mGPS-HR 1.16, 95% CI 1.04–1.30 and NLR-HR 1.21, 95% CI 1.08–1.36) and therefore had a similar contribution to the prognostic value of the SIG. When both overall and cancer-specific survival were stratified by a combination of either SIG and mGPS or SIG and NLR, only SIG retained independent significance.

Three-year overall/cancer-specific survival stratified by SIG

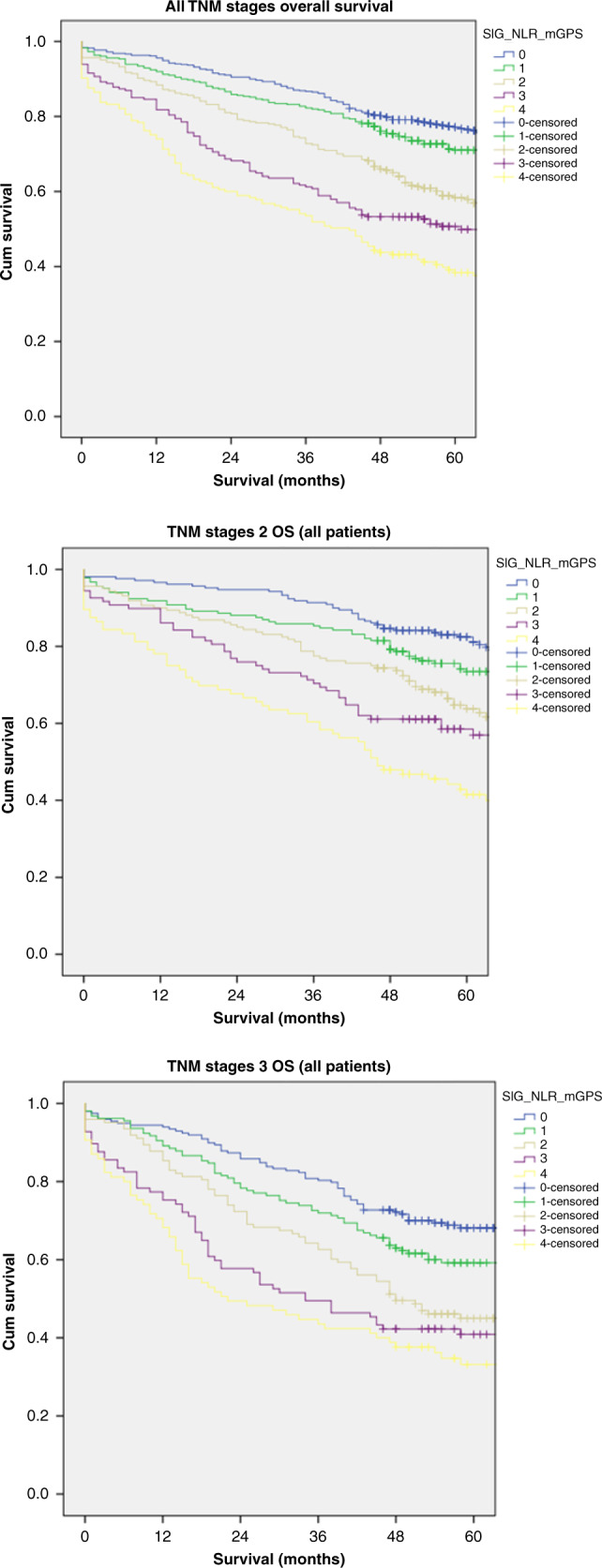

Three-year overall and cancer-specific survival for the combined cohort of patients and for each TNM Stage (I–III) stratified by SIG is shown in Table 4 and Supplementary Table 2. Within the whole cohort (Table 4), for SIG 0/1/2/3/4 3-year OS was 8%/84%/76%/65%/60% and CSS was 93%/90%/82%/73%/70%. For TNM Stage I disease (Supplementary Table 2) less than 10 TNM Stage I patients had either SIG 3 or 4 therefore survival analysis was not carried out for these groups. Within TNM Stage II colon cancer (Table 4), for SIG 0/1/2/3/4 3-year OS was 93%/87%/81%/75%/68% and CSS was 97%/96%/87%/86%/80%. Within TNM Stage III colon cancer (Table 4), for SIG 0/1/2/3/4 3-year OS was 82%/73%/65%/53%/48% and CSS was 86%/80%/69%/58%/58%. Similar results as shown in Table 4 were seen within the elective subgroup. Overall survival in all Stages and in TNM Stage II/III disease stratified by SIG is shown graphically in Fig. 2.

Table 4.

Three-year overall/cancer-specific displayed as percentage survival and percentage standard error (30-day mortality excluded) for each TNM stage stratified by SIG in both all patient and elective patient cohorts.

| All patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS | All patients (TNM-I–III) | TNM-II | TNM-III | |||

| SIG | n | % 3-yr OS (% SE) | n | % 3-yr OS (% SE) | n | % 3-yr OS (% SE) |

| 0 | 562 | 88% (SE 1%) | 205 | 93% (SE 2%) | 194 | 82% (SE 3%) |

| 1 | 404 | 84% (SE 2%) | 180 | 87% (SE 2%) | 154 | 73% (SE 4%) |

| 2 | 313 | 76% (SE 2%) | 153 | 81% (SE 3%) | 118 | 65% (SE 4%) |

| 3 | 201 | 65% (SE 3%) | 102 | 75% (SE 4%) | 90 | 53% (SE 5%) |

| 4 | 166 | 60% (SE 4%) | 85 | 68% (SE 5%) | 77 | 48% (SE 6%) |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||

| CSS | All patients (TNM-I–III) | TNM-II | TNM-III | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIG | n | % 3-yr OS (% SE) | n | % 3-yr OS (% SE) | n | % 3-yr OS (% SE) |

| 0 | 562 | 93% (SE 1%) | 205 | 97% (SE 1%) | 194 | 86% (SE 3%) |

| 1 | 404 | 90% (SE 2%) | 180 | 96% (SE 2%) | 154 | 80% (SE 3%) |

| 2 | 313 | 82% (SE 2%) | 153 | 87% (SE 3%) | 118 | 69% (SE 4%) |

| 3 | 201 | 73% (SE 3%) | 102 | 86% (SE 4%) | 90 | 58% (SE 5%) |

| 4 | 166 | 70% (SE 4%) | 85 | 80% (SE 5%) | 77 | 58% (SE 6%) |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||

| Elective patients | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OS | All patients (TNM-I–III) | TNM-II | TNM-III | |||

| SIG | n | % 3-yr OS (% SE) | n | % 3-yr OS (% SE) | n | % 3-yr OS (% SE) |

| 0 | 525 | 89% (SE 1%) | 188 | 93% (SE 2%) | 176 | 85% (SE 3%) |

| 1 | 341 | 84% (SE 2%) | 149 | 89% (SE 3%) | 124 | 73% (SE 4%) |

| 2 | 227 | 78% (SE 3%) | 111 | 84% (SE 3%) | 79 | 66% (SE 5%) |

| 3 | 97 | 66% (SE 5%) | 47 | 72% (SE 7%) | 43 | 56% (SE 8%) |

| 4 | 78 | 58% (SE 6%) | 40 | 65% (SE 8%) | 35 | 46% (SE 8%) |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||

| CSS | All patients (TNM-I–III) | TNM-II | TNM-III | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIG | n | % 3-yr OS (% SE) | n | % 3-yr OS (% SE) | n | % 3-yr OS (% SE) |

| 0 | 525 | 94% (SE 1%) | 188 | 97% (SE 1%) | 176 | 88% (SE 2%) |

| 1 | 341 | 91% (SE 2%) | 149 | 97% (SE 1%) | 124 | 80% (SE 4%) |

| 2 | 227 | 85% (SE 2%) | 111 | 91% (SE 3%) | 79 | 70% (SE 5%) |

| 3 | 97 | 77% (SE 4%) | 47 | 89% (SE 5%) | 43 | 61% (SE 8%) |

| 4 | 78 | 74% (SE 5%) | 40 | 81% (SE 7%) | 35 | 63% (SE 9%) |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | ||||

OS overall survival, CSS cancer-specific survival, SIG Systemic Inflammatory Grade, n number of patients, %3-year OS/CSS percentage 3-year overall/cancer-specific survival, %SE percentage standard error.

Fig. 2. Overall survival stratified by Systemic Inflammatory Grade.

Overall survival stratified by Systemic Inflammatory Grade (0-4) in all TNM Stages (Top), TNM Stage II disease (Middle) and TNM Stage III disease (bottom).

T4N0 and T(any)N2 disease are often considered to be associated with poor long-term survival. The utility of SIG in stratifying each of these is shown in Table 5. For T4N0 disease 3-year OS (including 30-day mortality) was 91%/80%/68%/68%/51% (p < 0.001) for SIG 0/1/2/3/4 (n = 35/46/57/53/49), respectively, and 3-year CSS (including 30-day mortality) for SIG 0/1/2/3/4 was 91%/80%/68%/68%/51% (p = 0.022). Three-year OS/CSS stratified by SIG after exclusion of 30-day mortality is shown in Table 5. For T(any)N2 disease 3-year OS (including 30-day mortality) was 67%/52%/57%/35%/28% (p < 0.001) for SIG 0/1/2/3/4 (n = 64/48/53/49/36), respectively, and 3-year CSS was 72%/56%/60%/37%/38% (p < 0.001) for SIG 0/1/2/3/4, respectively. Three-year OS/CSS stratified by SIG after exclusion of 30-day mortality is shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Three-year overall/cancer-specific survival displayed as percentage survival and percentage standard error (with and without 30-day mortality excluded) stratified by Systemic Inflammatory Grade for patients with T4N0 and T(any)N2 disease.

| T4N0 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIG | OS (inc 30-day mortality) | CSS (inc 30-day mortality) | OS (exc 30-day mortality) | CSS (Exc 30-day mortality) | ||||

| n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | n | %3 yr CSS (%SE) | n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | n | %3 yr CSS (%SE) | |

| 0 | 35 | 91% (SE 5%) | 35 | 94% (SE 4%) | 35 | 91% (SE 5%) | 35 | 94% (SE 4%) |

| 1 | 46 | 80% (SE 6%) | 46 | 88% (SE 5%) | 45 | 82% (SE 6%) | 45 | 90% (SE 5%) |

| 2 | 57 | 68% (SE 6%) | 57 | 73% (SE 6%) | 54 | 72% (SE 6%) | 54 | 76% (SE 6%) |

| 3 | 53 | 68% (SE 6%) | 53 | 80% (SE 6%) | 52 | 69% (SE 6%) | 52 | 82% (SE 5%) |

| 4 | 49 | 51% (SE 7%) | 49 | 61% (SE 7%) | 42 | 60% (SE 8%) | 42 | 69% (SE 7%) |

| p < 0.001 | p = 0.022 | p = 0.009 | p = 0.167 | |||||

| T(any)N2 | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIG | OS (inc 30-day mortality) | CSS (inc 30-day mortality) | OS (exc 30-day mortality) | CSS (exc 30-day mortality) | ||||

| n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | n | %3 yr CSS (%SE) | n | %3 yr OS (%SE) | n | %3 yr CSS (%SE) | |

| 0 | 64 | 67% (SE 6%) | 64 | 72% (SE 6%) | 64 | 67% (SE 6%) | 64 | 72% (SE 6%) |

| 1 | 48 | 52% (SE 7%) | 48 | 56% (SE 7%) | 47 | 53% (SE 7%) | 47 | 56% (SE 7%) |

| 2 | 53 | 57% (SE 7%) | 53 | 60% (SE 7%) | 51 | 59% (SE 7%) | 51 | 63% (SE 7%) |

| 3 | 49 | 35% (SE 7%) | 49 | 37% (SE 7%) | 46 | 37% (SE 7%) | 46 | 39% (SE 7%) |

| 4 | 36 | 28% (SE 7%) | 36 | 38% (SE 8%) | 32 | 31% (SE 8%) | 32 | 40% (SE 9%) |

| p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p < 0.001 | p = 0.002 | |||||

OS overall survival, CSS cancer-specific survival, 3-year OS/CSS 3-year overall/cancer-specific survival, SE percentage standard error.

Discussion

The results of the present study show that survival following curative surgery for colon cancer can be stratified using the SIG. Both mGPS and NLR were independently associated with overall survival after adjusting for other common clinicopathological factors and on this basis these scores were combined to form SIG. This SIG simply and effectively stratified overall and cancer-specific survival in the all TNM Stage and in the TNM Stage II and Stage III cohorts and was superior to mGPS or NLR alone in predicting overall and cancer-specific survival.

The prognostic value of either mGPS or NLR has been extensively reported within the literature in operable and non-operable cancer.5,15 To date, the combined prognostic value of mGPS and NLR have been reported in two studies. The first of these by Inamoto and co-authors11 reported that in 450 patients undergoing surgery for colorectal cancer, GPS and NLR had independent prognostic value. The second by McSorley and co-authors16 reported that in a cohort of 300 patients undergoing surgery for esophagogastric tumours, mGPS and NLR had complimentary value. The present study, within a cohort of 1700 patients undergoing curative surgery for colon cancer externally validates the independent prognostic value of mGPS and NLR and furthermore combines these into an overall SIG. It was of interest that both mGPS and NLR were similar in terms of hazard ratios for association with overall survival and therefore had a similar contribution to the prognostic value of the SIG. On MVA for a combination of either SIG and mGPS or SIG and NLR, only SIG remained independently significant. The biological rational for combining mGPS and NLR is clear since they represent the response of two different organ systems to the development of a Systemic Inflammatory Response. Therefore, SIG is a simple, objective measure of SIR that has prognostic value in Gastrointestinal Cancer.

The importance of the tumour-host immune/inflammatory response is increasingly recognised.17 Although complex, the processes involved provides several potential therapeutic targets to improve cancer outcomes however this creates a need to optimise stratification of the systemic inflammatory response. We have shown that the SIG has utility in stratifying survival in TNM Stage II and III disease and in two further disease stages recognised as high risk—T4N0 and T(any)N2.

In particular, the objective stratification of TNM Stage II patients with colon cancer is of interest. In the screening era the proportion of non-metastatic patients presenting with TNM stage I–II disease has increased from 57 to 65% (p < 0.001).18 It is hypothesised that this will increase further due to increased screening uptake through introduction of the faecal immunochemical testing (FIT). The optimal management of TNM Stage II colon cancer is less clear than other disease stages. While the role for adjuvant chemotherapy in TNM Stage III disease is well established, those patients with TNM Stage II disease are subcategorised as high or low risk based on the presence of a variety of clinicopathological features with high-risk patients being considered for chemotherapy.19 The evidence regarding chemotherapy within these Stage II patients is more limited, nevertheless some trials including the QUASAR trial20 have reported improved survival outcomes with adjuvant chemotherapy in Stage II colon cancer. The pre-operative systemic inflammatory response is not currently regarded as one of these high-risk features. However, the present work points to clinical utility of SIG and may provide an opportunity to improve outcomes through more targeted use of adjuvant therapy.

The present study has several limitations. Not all patients had both mGPS and NLR available and this may introduce bias into the present analysis. For example, it may be speculated that patients with more risk factors such as infections or chronic inflammatory diseases were more likely to have mGPS and NLR laboratory values. However, more than 60% of the eligible colon cancer patients had both pre-operative mGPS and NLR available to calculate SIG (n = 1708) and therefore confirms their independent prognostic value and the clinical utility of SIG. Moreover, the present study cohort is the largest to date that has evaluated the combined prognostic value of mGPS and NLR. Within the literature, the optimal normal threshold for NLR remains uncertain. For the purposes of this study the neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio was subdivided into <3/3–5/>5 as 3 and 5 were the most common cut off values identified in a previous meta-analysis.5 Finally, it seems likely that as seen in TNM Stage II/III disease, SIG also has utility in TNM Stage I disease. However, due to the lesser systemic inflammatory response observed within the TNM Stage I cohort and overall excellent prognosis within TNM Stage I disease the present study was underpowered to reliably assess this.

Further work is required to study the effect on survival of the pre-operative systemic inflammatory response measured by SIG within TNM Stage II disease when adjusted for current high-risk features. The analysis of SIG within randomised trials in patients with colon cancer, particularly regarding adjuvant chemotherapy in TNM Stage II disease would be of interest. While a previous meta-analysis10 examined the role of systemic inflammation-based scores in randomised clinical trials of colon cancer it included only those patients with metastatic disease. Within pancreatic cancer, an international consensus statement21 recommends a minimum dataset for those patients undergoing systemic treatment for advanced disease. This includes the components required for SIG and its equivalent in colon cancer would be useful.

Based on both the results of the present study and those within the published literature the pre-operative systemic inflammatory response should be measured through the use of a SIG incorporating both mGPS and NLR. The interactions between SIG and outcomes in TNM Stage IV disease remains of interest. Although not included in the present study, TNM Stage IV disease represents a significantly different disease process than TNM-I–III colon cancer with different treatment strategies and outcomes it would be of interest in future work. Additionally, the efficacy of adjuvant chemotherapy within different SIGs would be of interest in future studies as the relevant data to examine this was not available within the present dataset.

In conclusion, the present study confirms the potential to optimise stratification of long-term outcomes following curative surgery for colon cancer through the calculation of the modified Glasgow Prognostic Score and the Neutrophil-Lymphocyte Ratio to create an overall SIG. This is important, not only in providing patients with clinically relevant prognostic information but particularly within TNM Stage II disease to identify high-risk patients who may benefit from adjuvant therapy following curative surgery.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

A.G.—designing the work, acquiring data, data interpretation and drafting the manuscript. D.C.M.M.—conceiving and designing the work, interpreting the results and revising the manuscript. J-.P.—interpreting the results and revising the manuscript. D.M.—interpreting the results and revising the manuscript. P.H.—interpreting the results and revising the manuscript. C.R.—interpreting the results and revising the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of this work and agree to be accountable for all aspects of this work.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was granted for this project from the Public Benefit and Privacy Panel (NHS Scotland) for Health and Social Care (PBPP) and Caldicott Guardian Approval.

Data availability

Data are available on request.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Funding information

Nil to declare.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41416-021-01308-x.

References

- 1.Bray, F., Ferlay, J., Soerjomataram, I., Siegel, R. L., Torre, L. A. & Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin.68, 394–424 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Cancer Research UK. Bowel cancer incidence statistics. https://www.cancerresearchuk.org./health-professional/cancer-statistics/statistics-by-cancer-type/bowel-cancer/incidence. Accessed Nov 2020.

- 3.Dolan RD, McSorley ST, Park JH, Watt DG, Roxburgh CS, Horgan PG, et al. The prognostic value of systemic inflammation in patients undergoing surgery for colon cancer: comparison of composite ratios and cumulative scores. Br. J. Cancer. 2018;119:40–51. doi: 10.1038/s41416-018-0095-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park JH, Ishizuka M, McSorley ST, Kubota K, Roxburgh CSD, Nagata H, et al. Staging the tumor and staging the host: a two centre, two country comparison of systemic inflammatory responses of patients undergoing resection of primary operable colorectal cancer. Am. J. Surg. 2018;216:458–464. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.08.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dolan RD, Lim J, McSorley ST, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. The role of the systemic inflammatory response in predicting outcomes in patients with operable cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:16717. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16955-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park JH, Watt DG, Roxburgh CS, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. Colorectal cancer, systemic inflammation, and outcome: staging the tumor and staging the host. Ann. Surg. 2016;263:326–336. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park JH, Fuglestad AJ, Kostner AH, Oliwa A, Graham J, Horgan PG, et al. Systemic inflammation and outcome in 2295 patients with stage I-III colorectal cancer from Scotland and Norway: first results from the ScotScan Colorectal Cancer Group. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2020;27:2784–2794. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-08268-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McAllister SS, Weinberg RA. The tumour-induced systemic environment as a critical regulator of cancer progression and metastasis. Nat. Cell Biol. 2014;16:717–727. doi: 10.1038/ncb3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McMillan DC. The systemic inflammation-based Glasgow Prognostic Score: a decade of experience in patients with cancer. Cancer Treat. Rev. 2013;39:534–540. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dolan RD, Laird BJA, Horgan PG, McMillan DC. The prognostic value of the systemic inflammatory response in randomised clinical trials in cancer: a systematic review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2018;132:130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2018.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inamoto S, Kawada K, Okamura R, Hida K, Sakai Y. Prognostic impact of the combination of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and Glasgow prognostic score in colorectal cancer: a retrospective cohort study. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2019;34:1303–1315. doi: 10.1007/s00384-019-03316-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brewster D, Muir C, Crichton J. Registration of colorectal cancer in Scotland: an assessment of data accuracy based on review of medical records. Public Health. 1995;109:285–292. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3506(95)80206-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brewster DH, Stockton D, Harvey J, Mackay M. Reliability of cancer registration data in Scotland, 1997. Eur. J. Cancer. 2002;38:414–417. doi: 10.1016/S0959-8049(01)00385-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ScotPHO. Classification of deaths—Public Health Information for Scotland. https://www.scotpho.org.uk/publications/overview-of-key-data-sources/scottish-national-data-schemes/deaths. (2020)

- 15.Dolan RD, McSorley ST, Horgan PG, Laird B, McMillan DC. The role of the systemic inflammatory response in predicting outcomes in patients with advanced inoperable cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017;116:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McSorley, S. T., Lau, H. Y. N., McIntosh, D., Forshaw, M. J., McMillan, D. C. & Crumley, A. B. Staging the tumor and staging the host: pretreatment combined neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and modified Glasgow Prognostic Score is associated with overall survival in patients with esophagogastric cancers undergoing treatment with curative intent. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 28, 722–731 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Diakos CI, Charles KA, McMillan DC, Clarke SJ. Cancer-related inflammation and treatment effectiveness. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:e493–e503. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70263-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mansouri D, McMillan DC, Crearie C, Morrison DS, Crighton EM, Horgan PG. Temporal trends in mode, site and stage of presentation with the introduction of colorectal cancer screening: a decade of experience from the West of Scotland. Br. J. Cancer. 2015;113:556–561. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kannarkatt J, Joseph J, Kurniali PC, Al-Janadi A, Hrinczenko B. Adjuvant chemotherapy for stage II colon cancer: a clinical dilemma. J. Oncol. Pract. 2017;13:233–241. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.017210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Quasar Collaborative G, Gray R, Barnwell J, McConkey C, Hills RK, Williams NS, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy versus observation in patients with colorectal cancer: a randomised study. Lancet. 2007;370:2020–2029. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61866-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ter Veer E, van Rijssen LB, Besselink MG, Mali RMA, Berlin JD, Boeck S, et al. Consensus statement on mandatory measurements in pancreatic cancer trials (COMM-PACT) for systemic treatment of unresectable disease. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:e151–e160. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30098-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on request.