Abstract

Understanding mechanisms of resistance to abiraterone, one of the primary drugs approved for the treatment of castration resistant prostate cancer, remains a priority. The organic anion polypeptide 1B3 (OATP1B3, encoded by SLCO1B3) transporter has been shown to transport androgens into prostate cancer cells. In this study we observed and investigated the mechanism of induction of SLCO1B3 by abiraterone. Prostate cancer cells (22Rv1, LNCaP, and VCAP) were treated with anti-androgens and assessed for SLCO1B3 expression by qPCR analysis. Abiraterone treatment increased SLCO1B3 expression in 22Rv1 cells in vitro and in the 22Rv1 xenograft model in vivo. MicroRNA profiling of abiraterone-treated 22Rv1 cells was performed using a NanoString nCounter miRNA panel followed by miRNA target prediction. TargetScan and miRanda prediction tools identified hsa-miR-579-3p as binding to the 3′-untranslated region (3′UTR) of the SLCO1B3. Using dual luciferase reporter assays, we verified that hsa-miR-579-3p indeed binds to the SLCO1B3 3′UTR and significantly inhibited SLCO1B3 reporter activity. Treatment with abiraterone significantly downregulated hsa-miR-579-3p, indicating its potential role in upregulating SLCO1B3 expression. In this study, we demonstrated a novel miRNA-mediated mechanism of abiraterone-induced SLCO1B3 expression, a transporter that is also responsible for driving androgen deprivation therapy resistance. Understanding mechanisms of abiraterone resistance mediated via differential miRNA expression will assist in the identification of potential miRNA biomarkers of treatment resistance and the development of future therapeutics.

Subject terms: Cancer, Cancer therapeutic resistance

Introduction

Androgens and androgen receptor (AR) signaling drive prostate carcinogenesis. While androgen ablation therapy (ADT) has been the cornerstone of treatment for advanced prostate cancer, patients inevitably progress to castrate-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC) despite castrate levels of androgens (serum testosterone < 50 ng/mL). The current treatment armamentarium includes androgen biosynthesis inhibitors (e.g., abiraterone) and AR antagonists (e.g., enzalutamide, apalutamide, and darolutamide) that target persistent androgen production and AR signaling. Although these drugs prolong survival in men with CRPC, resistance eventually ensues; therefore, understanding mechanisms of resistance will facilitate future drug discovery and development.

Multiple groups have demonstrated SLCO1B3 induction in cancerous versus healthy tissue1,2. Our laboratory and others have investigated the role of steroid hormone transporters in modulating intratumoral androgen concentrations that promote CRPC progression1–5. We showed that the organic anion polypeptide 1B3 (OATP1B3) transporter facilitates the diffusion of unconjugated testosterone into cells, and polymorphic variations in the SLCO1B3 gene (encoding OATP1B3) are related to both the progression-free survival of men receiving ADT for hormone-responsive prostate cancer and the overall survival of men with CRPC3,4. We subsequently showed de novo OATP1B3 expression in prostate tumor cells contributes to greater androgen uptake, which is consistent with its role in disease progression1.

Because OATP1B3 is an important predictive marker in men with prostate cancer, it is essential to understand mechanisms governing its de novo expression. Transcriptional regulatory mechanisms for SLCO1B3 expression include the involvement of different transcription factors and is highly dependent on tissue types. The SLCO1B3 promoter can be transactivated by the farneosid X receptor (FXR)6, hepatic nuclear factor-1α7, and STAT56, while the hepatocyte nuclear factor 3β8, and constitutive androstane receptor9 have been reported to repress transcription. Hypoxia-mediated10,11 and epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation10,12–14 can also play a significant role in SLCO1B3 mRNA expression.

The transcriptional regulation of SLCO1B3 in prostatic tissue has not been fully elucidated. We have recently discovered that chetomin is a potent inducer of SLCO1B3 transcription in prostate cancer cells1. Chetomin targets p300 (E1A binding protein), a global transcriptional coactivator, by disrupting the structure of its CH1 domain and precludes its interaction with the hypoxia-inducible factor-1α (HIF-1α) transcription factor. We found that modulation of HIF-1α only modestly increased SLCO1B3 expression, suggesting that expression of SLCO1B3 may occur via a p300-mediated regulatory mechanism1. Previous studies have shown that p300 increases during ADT and that this upregulation is associated with increased tumor growth and progression; conversely, increasing androgens produced a dose-dependent decrease in p300 expression15.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding RNA molecules that function as key post-transcriptional regulators of gene expression by promoting mRNA degradation or translational repression16. The regulation of drug transporters by miRNAs has recently been investigated for the human intestine17. Though little research has involved miRNA in the direct regulation of SLCO1B3 in prostate cancer, SLCO1B3 was found to be negatively correlated with rifampin-induced miRNA expression in hepatocytes18. In addition, FXR and its target genes including SLCO1B3 are regulated by hsa-miR-192, also in hepatocytes19. More broadly, miRNA involvement in prostate cancer initiation, proliferation, progression, and therapeutic resistance has been relatively well described, with thousands of relevant miRNA species characterized. miRNAs have been found to regulate key driving pathways in prostate cancer, such as the AR signaling axis, TMPRSS2-ERG, and PTEN20–23.

In this study, we investigated the effect of the second-generation anti-androgen abiraterone on SLCO1B3 expression. We found that abiraterone stimulated the expression of SLCO1B3 and the mechanism of this effect involved regulation by miRNAs.

Results

Abiraterone treatment and increased SLCO1B3 expression in prostate cancer cells

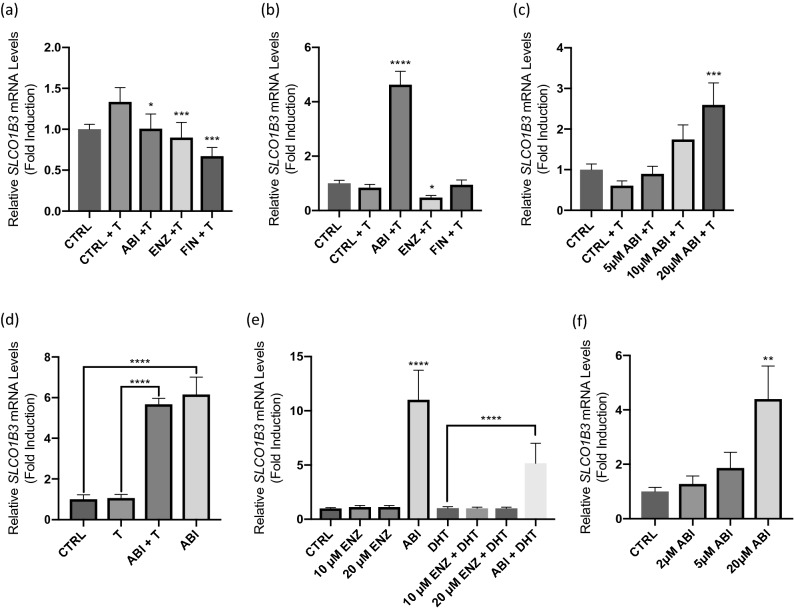

The relationship between p300/CBP and ADT has been characterized in advanced prostate cancer15,24. Since p300-mediates expression of SLCO1B3, we first examined the effect of antiandrogens on SLCO1B3 expression in two well characterized AR-positive prostate cancer cell lines (22Rv1 & LNCaP). Cells were treated with the second-generation antiandrogens abiraterone and enzalutamide, as well as finasteride, for 24 h. In LNCaP cells, abiraterone, enzalutamide and finasteride modestly decreased SLCO1B3 mRNA levels (Fig. 1a). Enzalutamide had a modest effect on transcript levels in 22Rv1 cells (Fig. 1b). Surprisingly, treatment with 20 µM abiraterone produced a significant increase in SLCO1B3 expression in 22Rv1 cells at 24 h (Fig. 1b), and this inhibition was sustained up to 72 h of treatment (Supplementary Fig. S1).

Figure 1.

AR-positive prostate cancer cell lines (LNCaP, 22Rv1, and VCaP) were treated with 1 nM testosterone and three prostate cancer drugs abiraterone (ABI), enzalutamide (ENZ), or finasteride (FIN) for 24 h. RNA was extracted and assessed for changes in SLCO1B3 expression using qPCR. Gene expression was normalized to expression of β-actin. (a) All treatment groups produced a significant reduction in its expression at 72 h in LNCaP Cells. (b) Abiraterone produced a highly significant upregulation of SLCO1B3 in 22Rv1 cells. (c) Concentration-dependent effect of abiraterone (ABI) significantly increased the expression of SLCO1B3. 22Rv1 cells were treated in phenol red-free, charcoal-stripped media with abiraterone (ABI), enzalutamide (ENZ) in the presence or absence of (d) 1 nM testosterone (T) or (e) 1 nM dihydrotestosterone (DHT) for 24 h. 22Rv1 cells were also treated with a higher dose (20 μM) of ENZ to confirm that ENZ treatment has no effect on SLCO1B3 expression. (f) The AR-positive prostate cancer cell line, VCaP, was treated with abiraterone at increasing concentrations for 24 h. ABI increased SLCO1B3 in a dose-dependent manner. RNA was harvested from cells after 24 h of treatment and assessed for changes in SLCO1B3 expression using qPCR analysis. Gene expression was normalized to expression of β-actin. Treatment in AR-negative PC3 cells did not affect SLCO1B3 expression (data not shown). Statistical tests were performed against CRTL + T for A-C. These data are the result of three independent experiments. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001, ****P < 0.00001.

Since a subset of patients is inherently resistant to both abiraterone and enzalutamide due to expression of AR-V725, we next examined the mechanism of abiraterone-induced upregulation of SLCO1B3 expression in 22Rv1 cells as a possible mechanism of resistance since this cell line expresses high levels of endogenous AR-variants (e.g., AR-V7) and exhibits intrinsic resistance to both enzalutamide and abiraterone26,27. When cells were treated with varying concentrations of abiraterone, expression of SLCO1B3 transcript was significantly upregulated in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1c). To investigate whether androgen mediated SLCO1B3 upregulation, we treated 22Rv1 cells in phenol red-free, charcoal-stripped media containing abiraterone in the presence and absence of two androgens, testosterone (T) and dihydrotestosterone (DHT). We found that SLCO1B3 was significantly upregulated by abiraterone regardless of androgen stimulation (Fig. 1d,e). While the abiraterone + DHT treatment appears to have induced SLCO1B3 to a lesser extent than ABI treatment alone, there is not a statistically significant difference in the SLCO1B3 expression levels between two treatment groups. Treatment with T or DHT increased KLK3 mRNA expression (data not shown), indicating androgen stimulation was potent enough to induce AR-dependent gene expression, but neither increased SLCO1B3 expression. We also evaluated whether there may be a dose-dependent effect with enzalutamide on SLCO1B3 transcripts and found that treatment with 10 µM and 20 µM doses of enzalutamide in the presence and absence of DHT did not affect the expression of SLCO1B3 (Fig. 1e).

Since LNCaP cells express the AR-T878A point mutation and 22Rv1 cells express both full-length and a constitutive active AR splice variant (AR-V7), we next determined the effect of abiraterone on the androgen-responsive VCaP cell line, which harbors the wild-type AR and AR-V728. We showed that abiraterone also increased the expression of SLCO1B3 mRNA in VCaP cells in a dose-dependent manner similar to that observed in 22Rv1 cells (Fig. 1f).

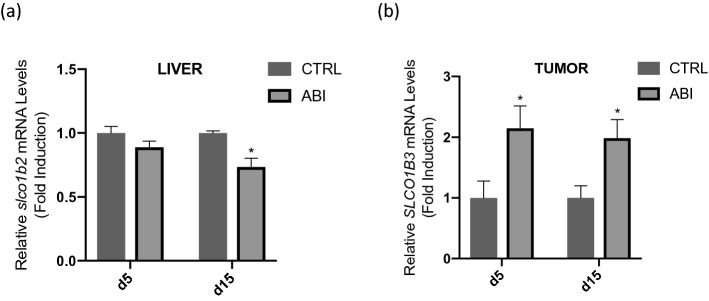

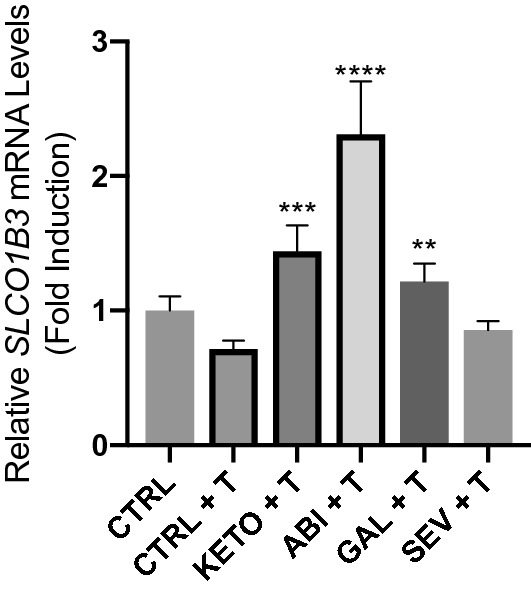

Other CYP17A1 inhibitors upregulate SLCO1B3

Since abiraterone is a potent inhibitor of the cytochrome P450 17A1 enzyme (CYP17), we next determined whether other CYP17A1 inhibitors may also be involved in regulating SLCO1B3 expression. 22Rv1 cells were treated with 20 µM ketoconazole, 10 µM seviteronel, and 10 µM galeterone alongside 20 µM abiraterone to assess whether upregulation of SLCO1B3 is abiraterone-specific, or whether this effect is common to the CYP17A1 inhibitor drug class. All drugs tested (except seviteronel) induced a statistically significant increase in SLCO1B3 transcripts, with abiraterone producing the largest increase of SLCO1B3 expression (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

The effect of CYP inhibitors on SLCO1B3 expression. 22Rv1 cells were treated with four CYP17 inhibitors, ketoconazole (Keto), abiraterone (ABI), galeterone (GAL), or seviteronel (SEV), in media supplemented with 1 nM testosterone for 24 h. Cells were treated with ketoconazole and abiraterone at a concentration of 20 µM and galeterone and seviteronel at a dose of 10 µM based on precedents set for in vitro experiments in previous publications. RNA was extracted and assessed for changes in SLCO1B3 expression using qPCR. Gene expression was normalized to expression of β-actin. All CYP17 inhibitors but seviteronel produced statistically significant induction of SLCO1B3 in 22Rv1 cells. Statistical tests were performed against CRTL + T. Data represent three independent experiments with triplicate measurements. **P < 0.001, ***P < 0.0001, ****P < 0.00001.

Abiraterone upregulates expression of tumor SLCO1B3 in a 22Rv1 mouse xenograft model

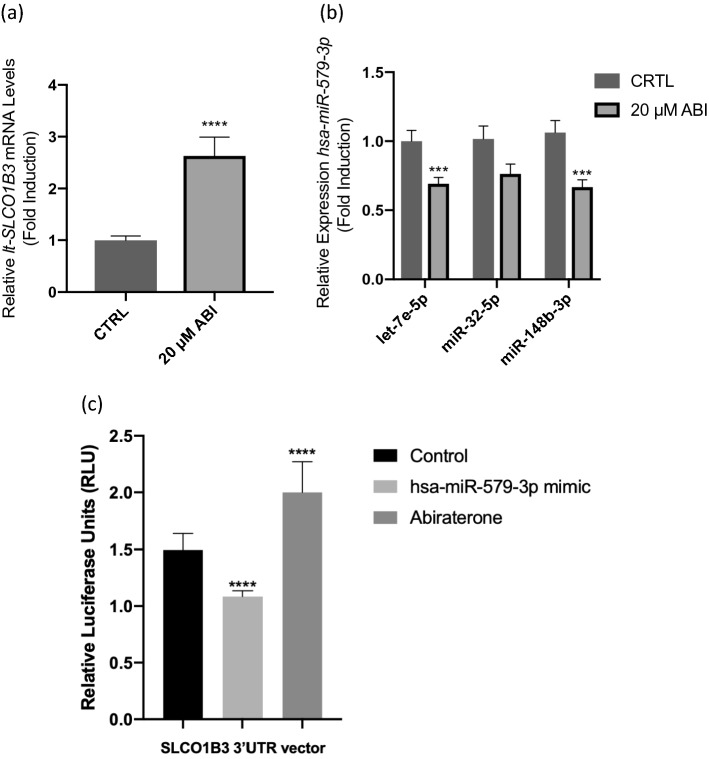

To assess whether abiraterone could upregulate SLCO1B3 in vivo, we treated mice bearing 22Rv1 xenografts with abiraterone acetate or vehicle control for either 5 or 15 days. As anticipated abiraterone treatment did not reduce the growth of 22Rv1 xenografts (data not shown), consistent with previous studies26,29. After 5 days of abiraterone acetate treatment, tumors were excised and digested to measure mRNA transcripts. Abiraterone-treated tumors exhibited a 2.5-fold increase in SLCO1B3 mRNA expression when compared with vehicle control (p < 0.05) (Fig. 3a). After 15 days of treatment, abiraterone-treated mice had a similar upregulation of SLCO1B3 (p < 0.05) when compared with control mice treated with vehicle control. Levels of slco1b2 (the mouse analogue of human SLCO1B3) in the livers of the mice were modestly decreased at day 15 of treatment (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Mice bearing 22Rv1 prostate cancer xenografts were treated with abiraterone acetate (AA) at 5 mmol/kg/day or vehicle control (95% safflower oil, 5% benzyl alcohol) via intraperitoneal injection every day for either (a) 5 or (b) 15 days. RNA was extracted from harvested tumor or liver tissue and reverse transcribed for analysis by qPCR. Gene expression was normalized to expression of β-actin. Significant upregulation of SLCO1B3 was observed at both time points. Mouse livers were assessed for changes in slco1b2 (the mouse analogue of human SLCO1B3) expression. While AA treatment induced a statistically significant decrease in mouse liver slco1b2 expression, the magnitude of the change was small and may not reflect how SLCO1B3 expression in a human liver would be affected by AA treatment. *P < 0.05.

Abiraterone-induced overexpression of SLCO1B3 is mediated by miRNA expression

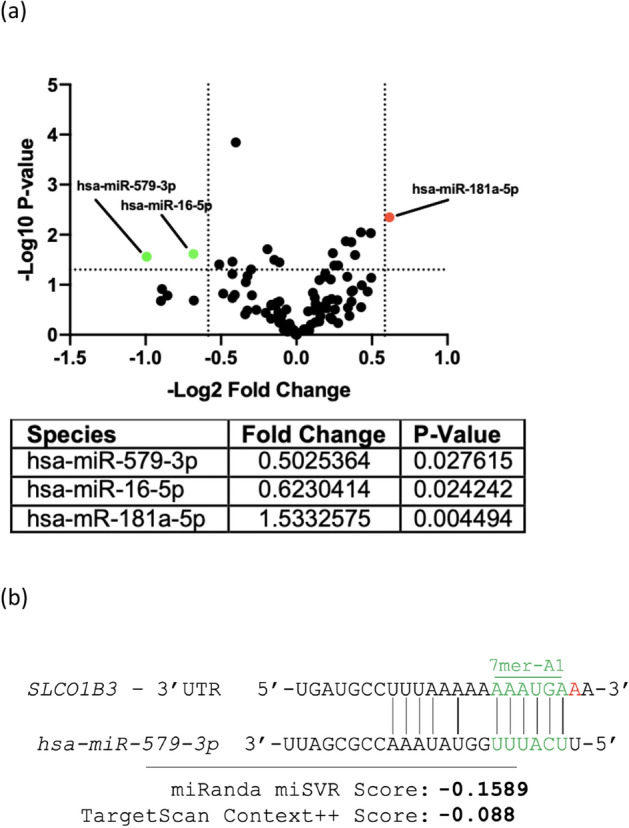

We have previously demonstrated that the liver-type SLCO1B3 (lt-SLCO1B3) was predominantly overexpressed in prostate tumor tissues1. We next determined whether abiraterone-induced SLCO1B3 mRNA expression occurred at the promoter level. Analysis of the SLCO1B3 promoter (containing the full-length 1492 bp upstream promoter from the transcription start site) characterized by luciferase reporter assays showed no cis-regulatory response to abiraterone treatment (Supplementary Fig. S2). We therefore hypothesized that the mechanism driving abiraterone-induced upregulation of SLCO1B3 was post-transcriptional, likely mediated by miRNA. To investigate the relationship between miRNA and lt-SLCO1B3 expression, we profiled the miRNA transcriptome of 22Rv1 cells treated with 20 µM abiraterone for 24 h, using the NanoString nCounter Human v3 miRNA panel. This assay rapidly and efficiently profiles 800 highly curated human miRNAs. We chose this hybridization-based nucleic acid counting method to avoid amplification biases, at the expense of resolving low-abundance miRNA species. Three miRNA species hsa-miR-579-3p, hsa-miR-16-5p, and hsa-mir-181a-5p were identified as significantly differentially expressed, demonstrating greater than 1.5-fold change (P<0.05) (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. S3).

Figure 4.

To investigate the relationship between miRNA and lt-SLCO1B3 expression, we profiled the miRNA transcriptome of cells treated with abiraterone using NanoString. (a) Differentially expressed miRNA species above 1.5-fold change and P < 0.05 in an unpaired Student’s T-test were selected for further analysis. (b) miRNA–mRNA binding prediction programs miRanda and TargetScan identified binding between hsa-miR-579-3p and SLCO1B3. Images show binding of hsa-miR-579-3p to the promoter of SLCO1B3 using TargetScan and miRanda.

To predict miRNA species with stable expression under abiraterone treatment, globally normalized counts from the NanoString panel were input in RefFinder, a program which aggregates stability-ranking programs BestKeeper, NormFinder, Genorm, and the comparative ∆-Ct method by taking the geometric mean of each program’s generated rankings. Hsa-let-7e-5p, hsa-miR-32-5p, and hsa-miR-148b-3p were predicted to be the most stable potential reference genes (Table 1). Stability of these reference genes was validated by qPCR analysis. As it was ranked as most stable by RefFinder, hsa-let-7e-5p was selected as the reference species against which the selected miRNA species would be measured, although use of hsa-miR-32-5p and hsa-miR-148b-3p provided similar results.

Table 1.

RefFinder ranking of miRNA Species.

| Rank | miRNA species | Delta CT | BestKeeper | NormFinder | Genorm | Geomean of ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | hsa-let-7e-5p | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1.41 |

| 2 | hsa-miR-32-5p | 2 | 1 | 1 | 21 | 2.55 |

| 3 | hsa-miR-148b-3p | 3 | 3 | 3 | 22 | 4.94 |

| 4 | hsa-miR-592 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 23 | 7 |

| 5 | hsa-miR-361-5p | 4 | 4 | 7 | 23 | 7.12 |

| 6 | hsa-miR-582-5p | 6 | 7 | 10 | 25 | 10.12 |

| 7 | hsa-miR-9-5p | 8 | 11 | 6 | 26 | 10.82 |

| 8 | hsa-miR-99a-5p | 11 | 10 | 9 | 27 | 12.79 |

| 9 | hsa-miR-98-5p | 7 | 9 | 14 | 36 | 13.35 |

| 10 | hsa-miR-22-3p | 9 | 6 | 16 | 36 | 13.37 |

MiRNA species identified as significantly differentially expressed by the NanoString panel were then screened by TargetScan3.030 and miRanda software31, miRNA-mRNA binding domain alignment programs. Only hsa-miR-579-3p was predicted by TargetScan and miRanda to bind to the 3′-UTR of the lt-SLCO1B3 transcript (Fig. 4b). The Context++ score generated by TargetScan7.2 is output from a model incorporating 14 miRNA-binding parameters and is reflective of the probability and extent to which an miRNA species will repress expression of a given mRNA target30. The Context++ score of − 0.088 given to the hsa-miR-579-3p/SLCO1B3-3′UTR is in the 92nd percentile for predicted SLCO1B3 3′UTR-binding miRNA species. The miRanda program is a machine learning-based predictive binding algorithm, and the calculated score of − 0.1589 reflects an approximate 40–50% probability that hsa-miR-579-3p represses transcript level of SLCO1B3 to the extent which we have observed, which is approximately 30–50%32.

The effects of abiraterone treatment on the expression of lt-SLCO1B3 and hsa-miR-579-3p in the samples processed for NanoString analysis were further validated by qPCR. Recapitulating the NanoString results, qPCR analysis found hsa-miR-579-3p miRNA expression to be reduced and lt-SLCO1B3 mRNA expression increased following abiraterone treatment (Fig. 5a,b). This is consistent with miRNA-mediated repression of lt-SLCO1B3. Using luciferase reporter system, we further demonstrated that hsa-miR-579-3p indeed binds to the SLCO1B3 3′UTR by cloning this sequence into a psiCHECK-2 vector, containing the renilla and continuously expressed firefly luciferase reporter gene. Next, we performed co-transfections of the psiCHECK-2-SLCO1B3 3′UTR plasmid (or empty vector plasmid) together with the hsa-miR-579-3p mimic or nonspecific mimic (negative control) in 22Rv1 cells followed by assaying for luciferase activity. Dual-luciferase reporter assay verified that SLCO1B3 is a target gene of hsa-miR-579-3p as our data demonstrated a significant decrease in luciferase reporter activity when cells were treated with the hsa-miR-579-3p mimic in comparison to the negative control (Fig. 5c), indicating that hsa-miR-579-3p directly targets SLCO1B3 by binding to its 3′UTR. We also showed that no significant difference was observed in cells transfected with a psiCHECK-2 vector lacking the 3′-UTR, further confirming the specific hsa-miR-579-3p binding interaction with the 3′UTR of SLCO1B3 (Supplementary Fig. S4). Luciferase activity was recovered and further increased in cells transfected with the psiCHECK-2-SLCO1B3 3′ UTR plasmid and treated with abiraterone as compared to the vehicle DMSO treated control, demonstrating that abiraterone treatment decreased hsa-miR-579-3p miRNA expression, resulting in increased SLCO1B3 reporter activity (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. S4). These results directly support our findings from both NanoString and qPCR analyses that hsa-miR-579-3p binds to the SLCO1B3 3′UTR and provide additional evidence for a mechanism of abiraterone-induced SLCO1B3 expression mediated by hsa-miR-579-3p.

Figure 5.

Abiraterone induces overexpression of lt-SLCO1B3 while suppressing hsa-miR-579-5p expression. Effects of abiraterone treatment on the expression of (a) lt-SLCO1B3 and (b) hsa-miR-579-3p in the samples processed for NanoString analysis were validated by qPCR analysis. As expected hsa-miR-579-3p expression was reduced and lt-SLCO1B3 expression was increased following abiraterone treatment, consistent with miRNA-transcript repression. (c) hsa-miR-579-3p directly binds to SLCO1B3 3′UTR. Co-transfection of 22Rv1 cells was performed with the 3′UTR reporter plasmid (or vector control plasmid) and hsa-miR-579-3p mimic (or negative control mimic) for 24 h followed by luciferase reporter assays. The assay revealed a significant decrease in SLCO1B3 reporter activity in the presence of the mimic. 22Rv1 cells were also transfected with the 3′UTR plasmid (or vector control plasmid) followed by treatment with 20 µM Abiraterone (or vehicle DMSO control) for 24 h. Abiraterone treatment resulted in an increase in SLCO1B3 luciferase reporter activity. No significant change was observed in the vector control plasmid lacking the 3′UTR (see Supplementary Fig. S4). These data are the results of three independent experiments performed in triplicates. ***P < 0.005, ****P < 0.0001.

Discussion

We have shown that abiraterone, one of the most commonly prescribed drugs for CRPC, induces a significant upregulation of SLCO1B3 transcripts in 22Rv1 and VCaP cells and in mice bearing 22Rv1 tumor xenografts. Expression levels of total-SLCO1B3 expression increase with abiraterone treatment in a dose-dependent manner in both 22Rv1 and VCaP cells. We demonstrated that abiraterone-mediated increase in SLCO1B3 transcripts occurred independently of androgen stimulation, consistent with our finding that abiraterone treatment in the androgen-independent PC3 cell line had no effect on SLCO1B3 expression (data not shown). We have previously shown that PC3 cells have higher endogenous expression of SLCO1B3 than 22Rv1 cells1 and have low level expressions of the CYP17A1 enzyme; therefore, these cells may not be as responsive to the effect of abiraterone treatment33.

We further demonstrated that other CYP17A1 inhibitors (abiraterone, ketoconazole, and galeterone) can upregulate SLCO1B3 transcripts. Abiraterone, ketoconazole, and galeterone inhibit both 17a-hydroxylase and 17,20-lyase of CYP17A1 whereas seviteronel has selective inhibition of 17,20-lyase over 17a-hydroxylase34,35. Whether 17,20-lyase selectivity or potency can explain why seviteronel does not affect SLCO1B3 remains to be determined36.

We showed that the mechanism of abiraterone-induced SLCO1B3 expression is regulated by miRNAs (hsa-miR-579-3p, hsa-miR-16-5p, and hsa-mir-181a-5p). We used two different miRNA target prediction tools to determine which of the three miRNAs interact with SLCO1B3. Using this computational approach, we predicted binding of hsa-miR-579-3p to the 3′-UTR of the SLCO1B3. Validation experiments were subsequently performed to confirm the NanoString data and revealed that the increase in abiraterone-mediated SLCO1B3 transcripts correlated with a decrease in expression of hsa-miR-579-3p, as verified with luciferase reporter assays demonstrating the binding of hsa-miR-579-3p to the SLCO1B3 3′UTR. Hsa-miR-579-3p has previously been shown to be downregulated in exosomes secreted by prostate cancer cells under hypoxic conditions, and is otherwise implicated in tumorigenesis in multiple other cell types via modulation of oncogenic kinase signaling pathways, such as PI3K, BRAF, RAS, and AKT37–40.

Previous studies have reported that SLCO1B3 can be regulated by miRNAs. In a study evaluating membrane drug transporters and miRNA gene expression changes mediated by rifampin treatment in hepatocytes, SLCO1B3 expression was reduced after rifampin treatment and negatively correlated with rifampin-induced hsa-miR-92a expression18. In addition, hsa-miR-192 was found to inhibit FXR, a known regulator of SLCO1B3, which in turn, suppressed SLCO1B3 expression19,41.

A recent study by Zedan et al. found hsa-miR-141-3p and hsa-miR-375-3p to be of clinical significance in predicting the outcome of patients treated with abiraterone. The study findings were based on analysis of a pre-selected group of five miRNAs that came from a literature review rather than using a global miRNA profiling approach like NanoString; thus, this may explain the discrepancy in their results, in addition to patient heterogeneity and exposure to prior treatment regimens42. Our inability to detect significant differential expression of these species is likely due to the difference in model systems, where we used an in vitro cell line model (a limitation of our study) rather than patient samples. Future studies using clinical samples would be needed to confirm whether hsa-miR-579-3p can be identified in patients treated with abiraterone and to correlate this observation with SLCO1B3 expression. It also remains to be determined the effect of abiraterone-induced SLCO1B3 expression on tissue abiraterone levels since the drug has been hypothesized to be an SLCO substrate43. Our study is further limited by the use of 22Rv1 cells with intrinsic resistance to abiraterone; future studies should examine the effect of miRNA-mediated SLCO1B3 expression in cell lines with acquired resistance to the drug as well as subsequent transport of substrates.

Our study identified two miRNAs, hsa-miR-16-5p and hsa-mir-181a-5p, that were differentially regulated by abiraterone treatment. Both miRNAs have previously been identified as potential diagnostic and therapeutic biomarkers for prostate cancer44–49. Interestingly, hsa-miR-181a-5p is known to suppress GRP78 in 22Rv1 cells50. GRP78, coordinates with SIAH2 to degrade AR-V751. Induction of hsa-miR-181a-5p could therefore be another miRNA-mediated mechanism of resistance against abiraterone. Therefore, while these two miRNAs may not be involved in regulating SLCO1B3 as a potential mechanism for abiraterone resistance, they may contribute to the overall abiraterone resistance mechanism and future studies are warranted to investigate their relevance.

In summary, we have shown that CYP17 inhibitors can stimulate the expression of SLCO1B3, the known testosterone uptake transporter. We demonstrated that the mechanism of abiraterone-induced SLCO1B3 expression is mediated by the miRNA, hsa-miR-579-3p. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a mechanism of resistance of abiraterone treatment attributed to miRNA regulation in controlling the expression of OATP1B3, an androgen transporter that has been implicated in driving the resistance to ADT through the mechanism of increasing uptake of residual androgens into prostate tumors. In addition, hsa-miR-579-3p may serve as a potential therapeutic biomarker for abiraterone resistance.

Materials and methods

Cell culture

All prostate cancer cell lines (CWR22Rv1, LNCaP, PC3, and VCaP) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Cell culture reagents were obtained from Gibco/Thermo Fisher Scientific (Gaithersburgh, MD), unless otherwise specified. The 22Rv1 and LNCaP cell lines were maintained in phenol red-free RPMI 1640 Medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Atlanta Biologicals, Flowery Branch, GA), 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 units/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B. For all experiments involving addition of steroid hormone, cells were plated in maintenance media, then medium was replaced with RPMI Medium 1640 supplemented with 10% charcoal stripped FBS (all other media components remained unchanged) for approximately 7 h before treatment. PC3 cells were cultured in F-12K Nutrient Mixture medium (Gibco), and VCaP cells were maintained and treated in DMEM Medium (Gibco) supplemented with 10% FBS, 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 units/mL streptomycin, and 0.25 μg/mL amphotericin B.

Reagents

Abiraterone and enzalutamide were purchased from Selleckchem (Houston, TX). Galeterone, finasteride, and ketoconazole were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). VT-646 (seviteronel) was ordered from Chemscene (Monmouth Junction, NJ). Abiraterone acetate for xenograft studies was purchased from Medkoo Biosciences (Morrisville, NC). All drugs were dissolved in DMSO, aliquoted and stored at − 80 °C. Testosterone (Sigma) was dissolved in ethanol and DHT (Steraloids Inc., Newport, RI) was dissolved in DMSO.

Semiquantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction

22RV1 and LNCaP cells were plated in 6-well dishes in maintenance media the day before treatment. Cells were serum-starved approximately 7 h prior to treatment and then incubated with the treatment medium for 24 h or 72 h. Total RNA was extracted from cells using the QIAshredder and RNeasy mini kits (Qiagen) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Extracted RNA was then assessed for purity using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Molecular Devices) and all samples were diluted to a concentration of 80 ng/µL in RNase-free water. Using 12 µL of each of these stocks, cDNA was synthesized using the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System for RT PCR (Thermofisher) as per the manufacturer’s protocol.

The RT PCR reaction yields 30 µL of cDNA reaction product. Two microliters of this cDNA was amplified by qPCR using the following TaqMan probes: SLCO1B3 (Hs00251986_m1, Applied Biosystems), LT-SLCO1B3 (Hs01127179_mH, Applied Biosystems). For each qPCR reaction, 2 µL of cDNA was mixed with 10 µL of Taqman Gene Expression Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), 7 µL of RNAse-free water, and 1 µL of the respective Taqman qPCR primer. Semiquantitative Real-Time Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR) was performed using an Applied Biosystems StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR system with StepOne Software. Each qPCR reaction was run in triplicate and gene expression was normalized to expression of β-actin. Fold-change in gene expression was calculated using the ΔΔCt method as described in the SABiosciences 2009 RT2 Profiler PCR Array System User Manual (SABiosciences, Frederick, MD).

Prostate cancer xenograft study

Six-week old, male, severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) mice were obtained from the NCI-Frederick Animal Production Area. 22Rv1 cells were cultured in maintenance media and harvested when they reached 80% confluency. Cells were washed with sterile phosphate buffered saline (Gibco) and approximately 6 million cells were injected subcutaneously into the rear flank of each SCID mouse. Mice were monitored and weighed daily. When tumor volumes reached ~ 200–250 mm3, animals were randomized into two groups of control vs treatment (n = 5). Each group was treated daily with intraperitoneal (i.p.) bolus injections of either the drug vehicle (95% safflower oil, 5% benzyl alcohol) or abiraterone acetate (0.5 mmol/kg) for either 5 or 15 consecutive days52. Tumor measurements used to calculate tumor volume (tumor volume = tumor length*tumor width*tumor height*π/6) were taken three days per week and mice were weighed daily. Mouse livers and tumors were excised on either day 5 or day 15 of treatment, and harvested tissue samples were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for subsequent gene expression analysis.

To analyze gene expression in the liver and tumor tissues, tissue was thawed on ice and an approximately 30 mg section was shaved off using a scalpel. This section was placed in a bead homogenizer tube with 600 µL of buffer RLT (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) and homogenized for roughly 30 s (BeadBug Benchtop Homogenizer, Benchmark Scientific). After the tissue was homogenized in lysis buffer, an equal (600 µL) volume of 70% alcohol was added to the tube and mixed gently to precipitate RNA. Then, 700 µL of the precipitated RNA mixture was transferred to an RNeasy Mini spin column (Qiagen) and the RNA extraction proceeded according to the RNeasy Mini Kit protocol (Qiagen). RNA was reverse-transcribed to cDNA and used for qPCR analysis using Mouse ACTB (4352663, Applied Biosciences) and slco1b2 (Mm00451510_m1, Applied Biosystems) probes. qPCR and data analysis were performed as previously described.

The National Cancer Institute (NCI) is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AAALAC) International and follows the Public Health Service (PHS) Policy for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Animal care was provided in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The study protocol was approved by the NCI Animal Care and Use Committee. This study was carried out in compliance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

miRNA analysis

miRNA extraction

22Rv1 cells were homogenized using a QIAshredder kit (Qiagen Cat#: 79654) and total RNA was extracted from the homogenate with a miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen Cat#: 217004) following manufacturer protocols. RNA was quantified for normalization using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific).

miRNA profiling

Total RNA was prepared for and profiled using the nCounter Human v3 miRNA Panel (NanoString Technologies) on the nCounter Analysis System (NanoString Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA was loaded at 100 ng per sample, hybridizations were 17–22 h long, and counts were gathered by scanning on HIGH mode for 280 fields of view per sample. Normalization and analysis of the NanoString panel data were performed using nSolver Software (NanoString Technologies). Base threshold was set to 20 counts. Global count normalization was performed using the geometric mean method as described in the nCounter Expression Data Analysis Guide (NanoString Technologies MAN-C0011-02). Linear ratio of normalized miRNA panel values was calculated by dividing the geometric mean of each experimental group by the geometric mean of the control, following the method described in the Gene Expression Data Analysis Guidelines (NanoString Technologies MAN-C0011-04). For each miRNA species, Log2 of each abiraterone and vehicle control value divided by the geometric mean of the vehicle control was calculated. The paired Student’s t-test was used to identify significant change in miRNA ratio. The Log2 fold-change values were plotted against the − Log10 of the P-value for each miRNA species to generate the volcano plot.

miRNA qPCR

MiRNA relative expression was quantified with TaqMan Advanced miRNA assays (Thermofisher). Normalized NanoString panel data, containing the top 100 most highly expressed species, was input into RefFinder53 to identify relatively highly expressed stable reference miRNA species: hsa-let-7e-5p, hsa-miR-32-5p, and hsa-miR-148b-3p. cDNA synthesis was performed using the Taqman Advanced miRNA Synthesis Kit (Thermofisher, Cat#: A28007) following the manufacturers protocol with a 10 ng total RNA input. qPCR was performed following manufacturer’s instructions using TaqMan Fast Advanced MasterMix (Thermofisher Cat#: 4444556) and Taqman Advanced miRNA Assays: hsa-let-7e-5p (Cat#: 478579_miR), hsa-miR-32-5p (Cat#: 478026_miR), hsa-miR-148b-3p (Cat#: 477824_miR), and hsa-miR-579-3p (Cat#: 479059_miR). Relative miRNA expression was calculated using the 2−∆∆Ct method, comparing hsa-miR-579-3p Ct to the corresponding mean of the stable reference miRNA species.

Construction of SLCO1B3 3′UTR luciferase reporter plasmid and reporter assays

The SLCO1B3 3′UTR was synthesized with flanking NotI and XhoI restriction sites in a pUC57 vector by GENEWIZ, Inc (South Plainfield, NJ). The synthesized sequence was then cloned into complementary restriction sites in a psiCHECK-2 vector, which contains both renilla and firefly luciferase reporter genes (Promega, CAT#: C8021). The constructed plasmid was sequenced to verify successful cloning.

22Rv1 cells were seeded in a 96-well dish for 24 h before transfection with 100 ng of psiCHECK-2 empty vector or 3′UTR plasmid using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Cat#: 11668019). The following day, cells were treated with 20 µM abiraterone (SelleckChem, Cat#: S1123) or vehicle control (0.4% DMSO) (Sigma Aldrich). After a 24-h treatment period, samples were lysed and assayed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, Cat#: E1910) per manufacturer’s protocol. Raw luminescence was measured for Renilla and firefly reporters using SpectraMax iD3 (Molecular Devices). For microRNA mimic treated samples, cells were instead co-transfected for 24 h with the psiCHECK-2 plasmid or empty vector and 1 pmol of hsa-miR-579-3p miRvana mimic or negative control (Life Technologies, Cat#: 4464066) before performing the reporter assay.

Statistical considerations

The Mann–Whitney U test was performed to test for differences in gene expression when multiple different drug treatments were performed. To assess the significance drug treatment gradients and drug class effects, Dunnett’s multiple comparison test was performed. Mann–Whitney U test was used to determine significance of changes in relative expression levels of hsa-miR-579-3p. All comparisons were conducted using GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Prism version 6.00, GraphPad Software, La Jolla CA).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Tristan M. Sissung for his helpful comments and suggestions. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organization imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Author contributions

D.K.P., C.H.C, and W.D.F. designed and supervised the study and provided research materials and resources. R.H.B., E.M.M., J.D.S., K.Y.L., E.N.R, C.H.C. developed methodologies. R.H.B., E.M.M., J.D.S., K.Y.L., E.N.R. conducted experiments and validated results. R.H.B., E.M.M., K.Y.L., C.H.C. performed data analysis. R.H.B., E.M.M., and C.H.C. wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, US (ZIA BC 010453).

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-90143-4.

References

- 1.Sissung TM, et al. Differential expression of OATP1B3 mediates unconjugated testosterone influx. Mol. Cancer Res. 2017;15:1096–1105. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-16-0477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wright JL, et al. Expression of SLCO transport genes in castration-resistant prostate cancer and impact of genetic variation in SLCO1B3 and SLCO2B1 on prostate cancer outcomes. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2011;20:619–627. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hamada A, et al. Effect of SLCO1B3 haplotype on testosterone transport and clinical outcome in Caucasian patients with androgen-independent prostatic cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:3312–3318. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharifi N, et al. A polymorphism in a transporter of testosterone is a determinant of androgen independence in prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2008;102:617–621. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2008.07629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang M, et al. SLCO2B1 and SLCO1B3 may determine time to progression for patients receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011;29:2565–2573. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood M, et al. Hormonal regulation of hepatic organic anion transporting polypeptides. Mol. Pharmacol. 2005;68:218–225. doi: 10.1124/mol.104.010371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jung D, et al. Characterization of the human OATP-C (SLC21A6) gene promoter and regulation of liver-specific OATP genes by hepatocyte nuclear factor 1 alpha. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:37206–37214. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vavricka SR, et al. The human organic anion transporting polypeptide 8 (SLCO1B3) gene is transcriptionally repressed by hepatocyte nuclear factor 3beta in hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Hepatol. 2004;40:212–218. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jigorel E, Le Vee M, Boursier-Neyret C, Parmentier Y, Fardel O. Differential regulation of sinusoidal and canalicular hepatic drug transporter expression by xenobiotics activating drug-sensing receptors in primary human hepatocytes. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2006;34:1756–1763. doi: 10.1124/dmd.106.010033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han S, Kim K, Thakkar N, Kim D, Lee W. Role of hypoxia inducible factor-1alpha in the regulation of the cancer-specific variant of organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B3 (OATP1B3), in colon and pancreatic cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013;86:816–823. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ramachandran A, et al. An in vivo hypoxia metagene identifies the novel hypoxia inducible factor target gene SLCO1B3. Eur. J. Cancer. 2013;49:1741–1751. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2012.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ichihara S, et al. DNA methylation profiles of organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B3 in cancer cell lines. Pharm. Res. 2010;27:510–516. doi: 10.1007/s11095-010-0064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imai S, et al. Epigenetic regulation of organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B3 in cancer cell lines. Pharm. Res. 2013;30:2880–2890. doi: 10.1007/s11095-013-1117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Furihata T, Sun Y, Chiba K. Cancer-type organic anion transporting polypeptide 1B3: Current knowledge of the gene structure, expression profile, functional implications and future perspectives. Curr. Drug Metab. 2015;16:474–485. doi: 10.2174/1389200216666150812142715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heemers HV, et al. Androgen deprivation increases p300 expression in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3422–3430. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hausser J, Zavolan M. Identification and consequences of miRNA-target interactions-beyond repression of gene expression. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2014;15:599–612. doi: 10.1038/nrg3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruckmueller H, et al. Clinically relevant multidrug transporters are regulated by microRNAs along the human intestine. Mol. Pharm. 2017;14:2245–2253. doi: 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.7b00076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benson EA, et al. Rifampin regulation of drug transporters gene expression and the association of microRNAs in human hepatocytes. Front. Pharmacol. 2016;7:111. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2016.00111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krattinger R, et al. microRNA-192 suppresses the expression of the farnesoid X receptor. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2016;310:G1044–G1051. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00297.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ganapathy K, et al. Multifaceted function of microRNA-299-3p fosters an antitumor environment through modulation of androgen receptor and VEGFA signaling pathways in prostate cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:5167. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-62038-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim J, Wu L, Zhao JC, Jin HJ, Yu J. TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions induce prostate tumorigenesis by modulating microRNA miR-200c. Oncogene. 2014;33:5183–5192. doi: 10.1038/onc.2013.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lu J, Mu X, Yin Q, Hu K. miR-106a contributes to prostate carcinoma progression through PTEN. Oncol. Lett. 2019;17:1327–1332. doi: 10.3892/ol.2018.9697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nip H, et al. Oncogenic microRNA-4534 regulates PTEN pathway in prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:68371–68384. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Comuzzi B, et al. The androgen receptor co-activator CBP is up-regulated following androgen withdrawal and is highly expressed in advanced prostate cancer. J. Pathol. 2004;204:159–166. doi: 10.1002/path.1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Antonarakis ES, et al. AR-V7 and resistance to enzalutamide and abiraterone in prostate cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014;371:1028–1038. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu C, Armstrong C, Zhu Y, Lou W, Gao AC. Niclosamide enhances abiraterone treatment via inhibition of androgen receptor variants in castration resistant prostate cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:32210–32220. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.8493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lombard AP, et al. Intra versus inter cross-resistance determines treatment sequence between taxane and AR-targeting therapies in advanced prostate cancer. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2018;17:2197–2205. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-17-1269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.van Bokhoven A, et al. Molecular characterization of human prostate carcinoma cell lines. Prostate. 2003;57:205–225. doi: 10.1002/pros.10290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ylitalo EB, et al. Marked response to cabazitaxel in prostate cancer xenografts expressing androgen receptor variant 7 and reversion of acquired resistance by anti-androgens. Prostate. 2020;80:214–224. doi: 10.1002/pros.23935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife. 2015 doi: 10.7554/eLife.05005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Betel D, Wilson M, Gabow A, Marks DS, Sander C. The microRNAorg resource: targets and expression. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D149–D153. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Betel D, Koppal A, Agius P, Sander C, Leslie C. Comprehensive modeling of microRNA targets predicts functional non-conserved and non-canonical sites. Genome Biol. 2010;11:R90. doi: 10.1186/gb-2010-11-8-r90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Giatromanolaki A, et al. CYP17A1 and androgen-receptor expression in prostate carcinoma tissues and cancer cell lines. Curr. Urol. 2019;13:157–165. doi: 10.1159/000499276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xiao F, Yang M, Xu Y, Vongsangnak W. Comparisons of prostate cancer inhibitors abiraterone and TOK-001 binding with CYP17A1 through molecular dynamics. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2015;13:520–527. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alex AB, Pal SK, Agarwal N. CYP17 inhibitors in prostate cancer: Latest evidence and clinical potential. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2016;8:267–275. doi: 10.1177/1758834016642370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Petrunak EM, Rogers SA, Aube J, Scott EE. Structural and functional evaluation of clinically relevant inhibitors of steroidogenic cytochrome P450 17A1. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2017;45:635–645. doi: 10.1124/dmd.117.075317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wu RR, Zhong Q, Liu HF, Liu SB. Role of miR-579-3p in the development of squamous cell lung carcinoma and the regulatory mechanisms. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2019;23:9464–9470. doi: 10.26355/eurrev_201911_19440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Angius A, et al. MicroRNA-425-5p expression affects BRAF/RAS/MAPK pathways in colorectal cancers. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2019;16:1480–1491. doi: 10.7150/ijms.35269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalhori MR, Irani S, Soleimani M, Arefian E, Kouhkan F. The effect of miR-579 on the PI3K/AKT pathway in human glioblastoma PTEN mutant cell lines. J. Cell Biochem. 2019;120:16760–16774. doi: 10.1002/jcb.28935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X, et al. Targeting signal-transducer-and-activator-of-transcription 3 sensitizes human cutaneous melanoma cells to BRAF inhibitor. Cancer Biomark. 2018;23:67–77. doi: 10.3233/CBM-181365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ohtsuka H, et al. Farnesoid X receptor, hepatocyte nuclear factors 1alpha and 3beta are essential for transcriptional activation of the liver-specific organic anion transporter-2 gene. J. Gastroenterol. 2006;41:369–377. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1784-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zedan AH, Osther PJS, Assenholt J, Madsen JS, Hansen TF. Circulating miR-141 and miR-375 are associated with treatment outcome in metastatic castration resistant prostate cancer. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:227. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57101-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mostaghel EA, et al. Association of tissue abiraterone levels and SLCO genotype with intraprostatic steroids and pathologic response in men with high-risk localized prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2017;23:4592–4601. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fredsoe J, et al. Profiling of circulating microRNAs in prostate cancer reveals diagnostic biomarker potential. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020 doi: 10.3390/diagnostics10040188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang F, et al. microRNA-16-5p enhances radiosensitivity through modulating Cyclin D1/E1-pRb-E2F1 pathway in prostate cancer cells. J. Cell Physiol. 2019;234:13182–13190. doi: 10.1002/jcp.27989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Akbayir S, Muslu N, Erden S, Bozlu M. Diagnostic value of microRNAs in prostate cancer patients with prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels between 2, and 10 ng/mL. Turk. J. Urol. 2016;42:247–255. doi: 10.5152/tud.2016.52463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shen H, et al. miR-181a-5p is downregulated and inhibits proliferation and the cell cycle in prostate cancer. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2018;11:3969–3976. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhiping C, et al. MiR-181a promotes epithelial to mesenchymal transition of prostate cancer cells by targeting TGIF2. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2017;21:4835–4843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li Y, et al. miR-181a-5p inhibits cancer cell migration and angiogenesis via downregulation of matrix metalloproteinase-14. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2674–2685. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Su SF, et al. miR-30d, miR-181a and miR-199a-5p cooperatively suppress the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone and signaling regulator GRP78 in cancer. Oncogene. 2013;32:4694–4701. doi: 10.1038/onc.2012.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liao Y, et al. Targeting GRP78-dependent AR-V7 protein degradation overcomes castration-resistance in prostate cancer therapy. Theranostics. 2020;10:3366–3381. doi: 10.7150/thno.41849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Z, et al. Conversion of abiraterone to D4A drives anti-tumour activity in prostate cancer. Nature. 2015;523:347–351. doi: 10.1038/nature14406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xie F, Xiao P, Chen D, Xu L, Zhang B. miRDeepFinder: A miRNA analysis tool for deep sequencing of plant small RNAs. Plant Mol. Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11103-012-9885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.