Key Points

Question

Organ scarcity means few individuals with advanced liver disease receive a liver allograft; are there other common failures in the transplantation process that further impede access to liver transplantation?

Findings

In a national-level cohort study of 34 494 patients with cirrhosis, few were referred for, placed on a waiting list for, or received a liver allograft within 3 years of meeting clinical criteria for transplantation, and most of the deficits occurred at the earlier referral step. Age, comorbidity, and social determinants were associated with low referral, wait-listing, and transplant rates; when documented, medical and psychosocial barriers explained most of the gaps in referral.

Meaning

This study’s findings suggest that separate benchmarks for referral and wait-listing and interventions that target potentially modifiable barriers may have an association with improved access to organ transplants.

This cohort study uses data from the United Network of Organ Sharing to assess the factors associated with referral, wait-listing, and receipt of liver allografts in veterans with end-stage liver disease.

Abstract

Importance

Organ scarcity means few patients with advanced liver disease undergo a transplant, making equitable distribution all the more crucial. Disparities may arise at any stage in the complex process leading up to this curative therapy.

Objective

To examine the rate of and factors associated with referral, wait-listing, and receipt of liver allografts.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study used linked data from comprehensive electronic medical records and the United Network of Organ Sharing. Adult patients with cirrhosis and a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease with addition of sodium score of at least 15 points between October 1, 2011, and December 31, 2017, were included in the study. Patients were from 129 hospitals in the integrated, US Department of Veterans Affairs health care system and were followed up through December 31, 2018. Statistical analyses were performed from April 28, 2020, to January 31, 2021.

Exposures

Sociodemographic (eg, age, insurance, income), clinical (eg, liver disease etiology, severity, comorbidity), and health care facility (eg, complexity, rural or urban, presence of a liver transplant program) factors were evaluated.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Referral, wait-listing, and liver transplantation.

Results

Of the 34 494 patients with cirrhosis (mean [SD] age, 62 [7.7] years; 33 560 men [97.29%]; 22 509 White patients [65.25%]), 1534 (4.45%) were referred, 1035 (3.00%) were wait-listed, and 549 (1.59%) underwent a liver transplant within 3 years of meeting clinical criteria for transplantation. Patient age of 70 years or older was associated with lower rates of referral (hazard ratio [HR], 0.09; 95% CI, 0.06-0.13), wait-listing (HR, 0.07; 95% CI, 0.04-0.12), and transplant (HR, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.04-0.16). Alcohol etiology for liver cirrhosis was associated with lower rates of referral (HR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.33-0.44), wait-listing (HR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.27-0.38), and transplant (HR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.23-0.37). In addition, comorbidity (none vs >1 comorbidity) was associated with lower rates of referral (HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.40-0.56), wait-listing (HR, 0.38; 95% CI, 0.31-0.46), and transplant (HR, 0.28; 95% CI, 0.21-0.38). African American patients were less likely to be referred (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.95) and wait-listed (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.61-0.88). Patients with lower annual income and those seen in facilities in the West were less likely to be referred (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.53-0.93), wait-listed (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.36-0.64), or undergo a transplant (HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.34-0.74). In a review of the medical records for 333 patients who had limited comorbidity but were not referred, organ transplant was considered as a potential option in 176 (52.85%). When documented, medical and psychosocial barriers explained most of the deficits in referral.

Conclusions and Relevance

In this cohort study, few patients with advanced liver disease received referrals, were wait-listed, or underwent a transplant. The greatest deficits occurred at the referral step. Although health systems routinely track rates and disparities for organ transplants among wait-listed patients, extending monitoring to the earlier stages may help improve equity and manage potentially modifiable barriers to transplantation.

Introduction

Liver transplantation offers the best hope for survival in patients with advanced liver disease.1 Unfortunately, organ scarcity means few patients actually receive an allograft.2,3 Therefore, the United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS) created criteria to ensure fair allocation of organs according to greatest clinical need.

Studies done in the US regarding nonclinical factors associated with the process of organ transplantation have mostly examined patients on the UNOS waiting list.4,5,6 Transplantation is the end result of a complex multistep process, starting from initial evaluation and referral to a transplant center. Disparities at these earlier stages may be just as important to fair organ allocation under UNOS selection rules. The few studies that have examined these earlier stages found deficits but were limited to a single center or specific regions.2,7,8 Many factors contribute to the referral and wait-listing process, and we should not expect universal rates. Nonetheless, more comprehensive research focusing on these initial stages may better inform efforts to improve equity in early access to organ transplantation.

Moreover, patient progression through the transplantation process may be affected by factors that are more difficult to measure. Differences in clinicians’ perceptions of the burden of comorbidity, concerns related to social and caregiver support, and expectations for adherence to medical treatments may influence referral decisions. To our knowledge, these factors have not been examined in previous studies.

We used a comprehensive, nationwide data set from the national US Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system combined with data from the UNOS Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) supplemented with targeted chart reviews to examine 3 sequential steps in the liver transplantation process: referral, wait-listing, and transplant.

Methods

This cohort study was approved by the institutional review board for Baylor College of Medicine and Affiliated Hospitals, which waived the need for informed consent owing to the use of preexisting data. This study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline.

Data Sources

We used data from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse, UNOS/OPTN, and patients’ electronic medical records (EMRs). The VA Corporate Data Warehouse includes data on all laboratory tests, pharmacy use, procedure and diagnosis codes, Vital Status, VA fee basis, and Text Integration Utility. Vital Status includes death dates and is more than 97% accurate.9 The VA fee basis includes services rendered outside the VA. Text Integration Utility contains progress notes and reports. The UNOS/OPTN includes data on all donors, wait-listed candidates, and allograft recipients in the US.

Study Cohort

We identified patients with cirrhosis based on 2 or more instances of cirrhosis or complications codes or 1 or more codes with at least 1 filled medication prescription used to treat cirrhosis complications between October 1, 2011, and September 30, 2015.10,11,12 We followed this cohort until December 31, 2017, to identify patients with clinically significant liver dysfunction, defined as a Model for End-Stage Liver Disease with addition of sodium (MELD-Na) score of at least 15 points. Professional societies recommend consideration for liver transplant in patients with a MELD-Na score of at least 15 points.1,13 We selected the date of the first MELD-Na score of at least 15 points as the index date (eMethods 1 in the Supplement).

To select regular users of the VA, we limited the cohort to those with at least 2 outpatient visits within 1 year after meeting the MELD-Na cutoff.14 We excluded patients younger than 18 years or older than 80 years, who underwent a liver transplant, or who were given a referral and/or wait-listed for transplant before the index date (eFigure in the Supplement). We followed our cohort until death or December 31, 2018, whichever came first.

Variable Definitions

Outcomes

Our outcomes were referral, wait-listing, and receipt of a liver allograft. To be considered for liver transplant within the VA, patients undergo an initial evaluation at their home facility. The evaluation and referral information is entered into the EMR using dedicated progress note templates with specific titles. Using the Text Integration Utility tables in the VA Corporate Data Warehouse, we identified referral based on a validated, comprehensive list of specific titles associated with progress notes containing the actual liver transplant referral request (eMethods 2 in the Supplement). We selected the date of the progress note that met our definition as the date of referral.

Using the UNOS/OPTN, we identified all patients who were wait-listed or underwent a liver transplant through December 31, 2018. We obtained all-cause mortality data from the VA Vital Status file.

Clinical Factors

Sociodemographic details included age, sex, race/ethnicity, medical insurance type, priority level, and region. We classified insurance as VA-private, VA-public (Medicare or Medicaid), and only VA insurance. Priority level is a VA-specific variable based on income, disability, and eligibility for government aid.15,16 We categorized region as Northeast, Midwest, Southeast, or West.

We defined cirrhosis etiology and severity. A diagnosis of hepatitis C virus (HCV) was based on any positive HCV ribonucleic acid test,17 and a diagnosis of hepatitis B virus was based on any positive hepatitis B surface antigen.18 A patient had alcohol-related disease if they had 1 or more International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes for alcohol use disorders or an Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT)-C score of at least 4 any time before the index date. We identified nonalcoholic steatohepatitis as the possible etiology for patients without any other cause who had diabetes or a body mass index (calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared) greater than 30 before cirrhosis diagnosis.19 Cirrhosis severity included MELD-Na scores and cirrhosis complications updated over time.11,19 We defined a range of physical and mental health conditions based on the Cirrhosis Comorbidity Index (CirCom) score.20 We ascertained history of depression and anxiety based on validated ICD-9 codes.21

Nonclinical Factors

We assigned each patient to a primary facility, defined as the hospital where they received the majority of their VA care, which was quantified as number of outpatient clinic visits within 1 year of the index date.22,23,24 Facility-level factors included complexity, total number of patients with cirrhosis seen at a facility during the cohort accrual period, whether the facility was a VA liver transplant center, and whether it was in a rural or urban setting. We derived driving distance to the VA transplant center as miles between the VA hospital where the patient received routine care and the closest VA transplant center.25

Structured Medical Record Review

To gain further insights into the reasons for nonreferral, 2 clinicians (F.K. and R.H.) performed a review of the EMRs for a randomly selected sample of nonreferred patients with limited comorbidity (CirCom score of 0 or 1 points), which we defined as a situation in which patients were potentially eligible for referral. We reviewed all progress notes from 5 years before to any time after the index date. We first determined whether organ transplant was considered as a potential treatment option but a decision was made not to formally refer the patient. We then assessed reasons for not referring based on a predefined taxonomy26 and published guidelines1 (eMethods 5 in the Supplement). We also evaluated the patient medical records for evidence of potential contraindications to transplant, even if they were not cited by the treating clinician as a reason for not referring the patient.

Statistical Analysis

We constructed 3 cause-specific Cox proportional hazards regression frailty models for time to referral, wait-listing, and transplant.27,28 For each model, patients entered the model on the index date (MELD-Na ≥15 points) and were followed until referral, wait-listing, transplant (for the 3 corresponding models), death date, or December 31, 2018. We time-updated all clinical factors using 6-month intervals, because most patients with cirrhosis are seen for follow-up biannually. All models accounted for the competing risk of death. We simultaneously modeled data at the patient and hospital levels.29 We used data-based multiple imputation and fit the specified frailty models to the imputed data sets.30,31 We used the Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate to adjust each model for multiple comparisons32 (eMethods 3 and 4 in the Supplement).

Secondary and Subgroup Analyses

In the primary analyses, we included patients who did not have a record of referral within the VA but were nonetheless wait-listed. Furthermore, the model for wait-listing captured the associations of covariates with both referral and wait-listing; the model for time to transplant captured associations with all 3 end points. To examine the 3 sequential steps among patients with continuous VA care and to determine the associations of factors separately for each step, we conducted a nested sequence of models limiting the time to wait-listing and transplant models to patients who were referred and wait-listed within the VA. Patients entered the wait-listing and transplant models at the time of referral (for the wait-listing model) and wait-listing (for the transplant model), respectively. We used the values before the new start time as the baseline value for covariates.

Our cohort had a high burden of comorbidity, which could be a justifiable exception to transplantation. We conducted subgroup analyses in patients with limited comorbidity (CirCom 0 or 1 points). We excluded patients who died within 1 year of index to allow sufficient time for referral. Liver disease could improve over time. We repeated models limited to patients with persistently high MELD-Na (≥15 points through follow-up). MELD-Na data were missing in more than 30% of 6-month follow-up intervals. Therefore, we conducted models in patients with complete information on all covariates. Last, there were several changes in the organ allocation policy during the study duration. We conducted subgroup analyses, stratified by whether patients entered the study cohort (1) before or after the Regional Share 35 (June 2013), which is a policy that allows for regional sharing of livers for patients with a MELD score of 35 points or higher, and (2) before or after revisions to hepatocellular carcinoma exception points (October 2015). We calculated a sample size on the basis of 80% power and the assumption that 50% of patients would have EMR-documented reasons for not being referred, which resulted in a total of 330 records. Significance was set at P > .05, and all P values were 2 sided. Statistical analyses were performed from April 28, 2020, to January 31, 2021. All analyses were conducted by SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc).

Results

Study Population

Of the 34 494 patients with cirrhosis from 129 VA facilities (mean [SD] age, 62 [7.7] years; 33 560 men [97.29%]; 22 509 White patients [65.25%]) included in the cohort, 1534 (4.45%) were referred, 1035 (3.00%) were wait-listed, and 549 (1.59%) underwent a liver transplant within 3 years of meeting clinical criteria for organ transplant (Table 1 and eFigure in the Supplement). Within 1 year of meeting clinical criteria for transplantation, 985 patients (2.86%) were referred, 540 (1.57%) were wait-listed, and 223 (0.65%) underwent an organ transplant (Table 2). A total of 6926 patients (20.08%) had VA-private insurance, 18 006 (52.20%) had VA-Medicare, and 8594 (24.91%) had VA as the only source of medical insurance. A substantial proportion of patients (n = 16 340 [47.37%]) had an annual income below the geographically adjusted income limit or were receiving government aid (as indicated by VA priority 4 or 5).15

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of 34 494 Patients With Cirrhosis .

| Characteristic | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sociodemographic characteristics | |

| Age group, y | |

| ≤54 | 5064 (14.68) |

| 55 to 59 | 6905 (20.02) |

| 60 to 64 | 10 178 (29.51) |

| 65 to 69 | 7890 (22.87) |

| 70 to 74 | 2849 (8.26) |

| ≥75 | 1608 (4.66) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 33 560 (97.29) |

| Female | 934 (2.71) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| White | 22 509 (65.25) |

| African American | 6748 (19.56) |

| Hispanic | 2161 (6.26) |

| Othera | 857 (2.48) |

| Missing | 2219 (6.43) |

| Insurance | |

| VA-private | 6926 (20.08) |

| VA-Medicare | 18 006 (52.20) |

| VA-Medicaid | 968 (2.81) |

| VA only | 8594 (24.91) |

| Region | |

| Northeast | 4304 (12.48) |

| Midwest | 6560 (19.02) |

| Southeast | 15 834 (45.90) |

| West | 7796 (22.60) |

| Priority statusb | |

| 1-3 | 13 616 (39.17) |

| 4-5 | 16 340 (47.37) |

| 6-8 | 4451 (12.90) |

| Missing | 87 (0.25) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Cirrhosis etiology | |

| HCV alone | 4275 (12.39) |

| Alcohol alone | 12 547 (36.37) |

| HCV and alcohol | 9829 (28.49) |

| Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis | 5668 (16.43) |

| Other etiologies | 2175 (6.31) |

| MELD-Na score | |

| 15-19 | 23 880 (69.23) |

| 20-24 | 6927 (20.08) |

| 25-29 | 1826 (5.29) |

| ≥30 | 1861 (5.40) |

| Cirrhosis complications | |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 13 163 (38.16) |

| Ascites | 16 290 (47.23) |

| Varices | 11 774 (34.13) |

| HCC | 5472 (15.86) |

| Comorbidity (CirCom score)c | |

| 0 | 7409 (21.48) |

| 1 + 0 | 9717 (28.17) |

| 1 + 1 | 6936 (20.11) |

| ≥3 | 10 432 (30.24) |

| Depression | 14 822 (42.97) |

| Anxiety | 6179 (17.91) |

| Facility characteristics | |

| Complexity level | |

| Low/medium complexity | 5410 (15.68) |

| High complexity | 29 084 (84.32) |

| Facility cirrhosis volumed | |

| Low | 2320 (6.73) |

| Medium | 5465 (15.84) |

| Medium-high | 9449 (27.39) |

| High | 17 260 (50.04) |

| Transplant center | |

| No | 31 550 (91.47) |

| Yes | 2944 (8.53) |

| Urban/rural | |

| Urban | 22 537 (65.34) |

| Rural | 11 716 (33.97) |

| Missing | 241 (0.70) |

| Distance to closest transplant center, mi | |

| <200 | 11 865 (34.40) |

| 200-499 | 13 808 (40.03) |

| ≥500 | 8821 (25.57) |

Abbreviations: CirCom, Cirrhosis Comorbidity Index; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; MELD-Na, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease with addition of sodium; VA, Veterans Affairs.

Other includes Asian, Native American, and Hawaiian or Pacific Islander.

Priority status15: 1-3, varying degrees of disability; 4, catastrophically disabled or receiving home benefits; 5, annual income below the VA pension benefits national income threshold or receiving Medicaid or VA pension; 6, World War I or different combat exposures; 7-8, income above the national income threshold or those who agree to pay copay.

CirCom: medical records of patients with the following most recent inpatient or outpatient diagnoses given in the 5 years before index date were obtained: nonmetastatic cancer, metastatic cancer, hematologic cancer, substance abuse other than alcoholism, epilepsy, acute myocardial infarction, heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and chronic kidney disease. CirCom score was calculated by the algorithm by Jepsen et al.20

Facility volume: low (≤25th percentile, 118-396 patients); medium (>25th to ≤50th percentile, 397-683 patients); medium-high (>50th to ≤75th percentile, 686-1054 patients); high (>75th percentile, 1201-2641 patients).

Table 2. Rate of Referral, Placement on Waiting List, and Receipt of Transplant (N = 34 494).

| Outcome | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| 1-y Outcome | |

| Referrala | 985 (2.86) |

| Waiting list | 540 (1.57) |

| Transplant | 223 (0.65) |

| Death | 11 533 (33.43) |

| 3-y Outcome | |

| Referral | 1534 (4.44) |

| Waiting list | 1035 (3.00) |

| Transplant | 549 (1.59) |

| Death | 19 441 (56.36) |

| Overall | |

| Referral | 1736 (5.03) |

| Waiting list | 1186 (3.44) |

| Transplant | 683 (1.98) |

| Death | 23 472 (68.05) |

Abbreviation: VA, Veterans Affairs.

Referral captures referrals within the VA. The end points are not mutually exclusive.

Most patients had HCV or alcohol-related cirrhosis (4275 [12.39%] had HCV alone, 12 547 [36.37%] had alcohol-related cirrhosis alone, and 9829 [28.49%] had both HCV and alcohol-related cirrhosis). More than 30% had a MELD-Na score greater than or equal to 20 points (20-24 points, 6927 patients [20.08%]; 25-29 points, 1826 [5.29%]; and ≥30 points, 1861 [5.40%]), indicating advanced liver disease, 16 290 (47.23%) had ascites, 13 163 (38.16%) had hepatic encephalopathy, and 5472 (15.86%) had hepatocellular carcinoma. In total, 19 699 (57.11%) had a history of drug or alcohol abuse, 11 066 (32.08%) had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 5742 (16.65%) had heart failure, and 17 368 (50.35%) had multiple comorbidities. Most patients were treated in high-complexity (29 084 [84.32%]), medium-high–volume (9449 [27.39%]) or high-volume (17 260 [50.04%]), and urban (22 537 [65.34%]) settings; only 2944 patients (8.53%) received routine care from a VA transplant center.

Factors Associated With Referral, Wait-listing, and Liver Transplant

Compared with patients with cirrhosis caused by HCV, those with cirrhosis attributed to alcohol were less likely to be referred (hazard ratio [HR], 0.38; 95% CI, 0.33-0.44), wait-listed (HR, 0.32; 95% CI, 0.27-0.38), or undergo a transplant (HR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.23-0.37) (Table 3). Patients with higher MELD-Na scores (ie, greater than 30 points) were more likely to be referred (HR, 1.87; 95% CI, 1.57-2.23), wait-listed (HR, 1.43; 95% CI, 1.12-1.81), and undergo an organ transplant (HR, 1.91; 95% CI, 1.42-2.57), and patients with the presence of cirrhosis complications (eg, hepatic encephalopathy etiology) were more likely to be referred (HR, 2.18; 95% CI, 1.96-2.42), wait-listed (HR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.86-2.39), and to undergo an organ transplant (HR, 2.14; 95% CI, 1.81-2.53). Compared with patients with no comorbidity (CirCom score of 0 points), those with 1 minor comorbidity (CirCom score of 1 point) had a 24% lower likelihood of referral (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.68-0.85), 37% lower likelihood of wait-listing (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.54-0.72), and 43% lower likelihood of undergoing a transplant (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.47-0.68); those with more than 1 comorbidity or a single serious comorbidity (CirCom 1 + 1 point) had a 53% lower likelihood of referral (CirCom 1 + 1 HR, 0.47; 95% CI, 0.40-0.56). Depression was also associated with a lower likelihood of referral (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.73-0.91) and wait-listing (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.98).

Table 3. Association Between Clinical and Nonclinical Factors and Referral, Waiting List, and Transplant; Results of Multivariable Analyses (N = 34 494).

| Variable | Referral (N = 1736) | Waiting list (N = 1186) | Transplant (N = 683) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P valuea | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P valuea | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P valuea | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||||

| Cirrhosis etiology | ||||||

| HCV alone | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Alcohol alone | 0.38 (0.33-0.44) | <.001 | 0.32 (0.27-0.38) | <.001 | 0.30 (0.23-0.37) | <.001 |

| HCV and alcohol | 0.55 (0.48-0.63) | <.001 | 0.52 (0.44-0.61) | <.001 | 0.59 (0.47-0.73) | <.001 |

| NASH | 0.91 (0.77-1.06) | .29 | 0.76 (0.64-0.92) | .006 | 0.91 (0.72-1.15) | .56 |

| Other | 0.73 (0.58-0.92) | .01 | 0.67 (0.51-0.87) | .005 | 0.65 (0.46-0.93) | .03 |

| MELD-Na score | ||||||

| <20 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 20-24 | 1.56 (1.38-1.77) | <.001 | 1.41 (1.22-1.64) | <.001 | 1.45 (1.18-1.78) | .001 |

| 25-29 | 1.62 (1.39-1.88) | <.001 | 1.68 (1.40-2.01) | <.001 | 1.97 (1.56-2.49) | <.001 |

| ≥30 | 1.87 (1.57-2.23) | <.001 | 1.43 (1.12-1.81) | .006 | 1.91 (1.42-2.57) | <.001 |

| Cirrhosis complications | ||||||

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 2.18 (1.96-2.42) | <.001 | 2.11 (1.86-2.39) | <.001 | 2.14 (1.81-2.53) | <.001 |

| Ascites | 2.13 (1.86-2.43) | <.001 | 1.95 (1.67-2.28) | <.001 | 2.28 (1.84-2.82) | <.001 |

| Varices | 2.38 (2.11-2.68) | <.001 | 1.95 (1.70-2.25) | <.001 | 1.62 (1.34-1.96) | <.001 |

| HCC | 1.74 (1.56-1.94) | <.001 | 1.63 (1.43-1.86) | <.001 | 1.96 (1.66-2.33) | <.001 |

| CirCom score | ||||||

| 0 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 1 + 0 | 0.76 (0.68-0.86) | <.001 | 0.63 (0.54-0.72) | <.001 | 0.57 (0.47-0.68) | <.001 |

| 1 + 1 | 0.47 (0.40-0.56) | <.001 | 0.38 (0.31-0.46) | <.001 | 0.28 (0.21-0.38) | <.001 |

| ≥3 | 0.53 (0.46-0.62) | <.001 | 0.36 (0.30-0.44) | <.001 | 0.31 (0.24-0.40) | <.001 |

| Depression | 0.82 (0.73-0.91) | <.001 | 0.86 (0.75-0.98) | .03 | 0.88 (0.74-1.05) | .23 |

| Anxiety | 0.98 (0.85-1.13) | .77 | 0.90 (0.75-1.07) | .31 | 0.87 (0.69-1.11) | .38 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age group, y | ||||||

| ≤54 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 55 to 59 | 0.79 (0.69-0.91) | .002 | 0.74 (0.62-0.87) | .001 | 0.73 (0.59-0.92) | .01 |

| 60 to 64 | 0.73 (0.64-0.84) | <.001 | 0.63 (0.54-0.74) | <.001 | 0.66 (0.54-0.82) | <.001 |

| 65 to 69 | 0.46 (0.39-0.55) | <.001 | 0.48 (0.40-0.58) | <.001 | 0.48 (0.37-0.62) | <.001 |

| ≥70 | 0.09 (0.06-0.13) | <.001 | 0.07 (0.04-0.12) | <.001 | 0.08 (0.04-0.16) | <.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Male | 0.84 (0.65-1.09) | .27 | 0.84 (0.62-1.15) | .35 | 1.36 (0.82-2.25) | .33 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| White | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| African American | 0.82 (0.70-0.95) | .02 | 0.73 (0.61-0.88) | .002 | 0.78 (0.62-0.98) | .05 |

| Hispanic | 1.16 (0.96-1.41) | .19 | 0.98 (0.76-1.27) | .93 | 0.96 (0.69-1.33) | .87 |

| Other | 1.09 (0.82-1.45) | .64 | 1.00 (0.69-1.44) | .99 | 1.01 (0.61-1.67) | .96 |

| Priority status | ||||||

| 6-8 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 1-3 | 1.02 (0.88-1.18) | .79 | 0.86 (0.73-1.01) | .103 | 0.76 (0.61-0.93) | .02 |

| 4-5 | 0.81 (0.70-0.94) | .009 | 0.67 (0.57-0.79) | <.001 | 0.65 (0.53-0.80) | <.001 |

| Insurance status | ||||||

| VA-private | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| VA-Medicare | 0.98 (0.87-1.11) | .77 | 0.87 (0.76-1.00) | .07 | 0.83 (0.69-0.99) | .05 |

| VA-Medicaid | 0.71 (0.51-0.97) | .05 | 0.43 (0.28-0.66) | .000 | 0.45 (0.25-0.80) | .01 |

| VA only | 0.76 (0.66-0.88) | .001 | 0.41 (0.34-0.50) | <.001 | 0.30 (0.22-0.39) | <.001 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Midwest | 0.96 (0.73-1.25) | .77 | 0.85 (0.65-1.11) | .31 | 0.99 (0.70-1.40) | .96 |

| Southeast | 0.89 (0.70-1.14) | .45 | 0.67 (0.53-0.86) | .002 | 0.88 (0.65-1.21) | .55 |

| West | 0.70 (0.53-0.93) | .02 | 0.48 (0.36-0.64) | <.001 | 0.50 (0.34-0.74) | .001 |

| Facility characteristics | ||||||

| Complexity level | ||||||

| Low/medium complexity | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| High complexity | 1.06 (0.79-1.41) | .77 | 1.12 (0.83-1.51) | .54 | 0.90 (0.61-1.34) | .68 |

| Cirrhosis volume | ||||||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Medium | 0.81 (0.60-1.08) | .22 | 0.83 (0.60-1.15) | .34 | 0.88 (0.57-1.35) | .66 |

| Medium-high | 0.85 (0.59-1.22) | .46 | 1.01 (0.69-1.49) | .96 | 1.37 (0.82-2.26) | .33 |

| High | 0.73 (0.50-1.05) | .13 | 0.88 (0.60-1.30) | .58 | 0.97 (0.58-1.62) | .95 |

| Transplant center | ||||||

| Yes | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| No | 0.72 (0.51-1.02) | .10 | 0.76 (0.55-1.05) | .13 | 0.67 (0.44-1.01) | .08 |

| Urban/rural | ||||||

| Urban | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Rural | 1.16 (1.04-1.29) | .01 | 1.05 (0.92-1.19) | .54 | 0.99 (0.83-1.17) | .94 |

| Distance to closest transplant center, mi | ||||||

| <200 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 200-499 | 0.89 (0.77-1.04) | .19 | 0.92 (0.78-1.09) | .40 | 0.92 (0.74-1.14) | .55 |

| ≥500 | 0.95 (0.78-1.14) | .64 | 0.94 (0.76-1.16) | .62 | 0.92 (0.69-1.22) | .66 |

Abbreviations: CirCom, Cirrhosis Comorbidity Index; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HR, hazard ratio; MELD-Na, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease with addition of sodium score; NA, not applicable; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; VA, Veterans Affairs.

False discovery rate–adjusted P value.

Older age was associated with a lower probability of referral, wait-listing, and transplantation. Few patients older than 70 years were referred (HR, 0.09; 95% CI, 0.06-0.13), were wait-listed (HR, 0.07; 95% CI, 0.04-0.12), or underwent a transplant (HR, 0.08; 95% CI, 0.04-0.16). African American patients were 18% less likely to be referred (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.70-0.95) and 27% less likely to be wait-listed (HR, 0.73; 95% CI, 0.61-0.88) than White patients. Patients in the higher poverty levels (priority status 4 and 5) and those with VA-only insurance were less likely to meet all 3 outcomes, although the magnitude of associations was stronger for wait-listing (HR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.57-0.79 and HR, 0.41; 95% CI, 0.34-0.50, respectively) and transplantation outcomes (HR, 0.65, 95% CI, 0.53-0.80 and HR, 0.30; 95% CI, 0.22-0.39, respectively). Patients in the West had a significantly lower probability of being referred (HR, 0.70; 95% CI, 0.53-0.93), being wait-listed (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.36-0.64), and undergoing a transplant (HR, 0.50; 95% CI, 0.34-0.74) than patients seen in the Northeast.

Sensitivity Analyses

In the nested models (Table 4), there were no statistically significant associations between cirrhosis severity and wait-listing (among referred patients) or undergoing a transplant (among wait-listed patients). There were no statistically significant differences in wait-listing or undergoing a transplant by race/ethnicity, once referred. Comorbidity was associated with the probability of wait-listing (CirCom score ≥3 points, adjusted HR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.44-0.72) but not undergoing a transplant. Disparities by other social factors and region persisted for wait-listing. Patients who did not seek their regular care from a facility with a VA liver transplant center had a 54% lower probability of being wait-listed than patients who were treated in transplant centers (HR, 0.46; 95% CI, 0.31-0.68), once referred. The associations of clinical and nonclinical factors in other subgroups were similar to those for the primary analyses (eTables 1-6 in the Supplement).

Table 4. Association Between Clinical and Nonclinical Factors and Waiting List (n = 1736) and Transplant (n = 801).

| Variable | Waiting list (n = 801) among referred patients (n = 1736) | Transplants (n = 440) among patients who were referred and placed on waiting list (n = 801) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P valuea | Adjusted HR (95% CI) | P valuea | |

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Cirrhosis etiology | ||||

| HCV alone | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Alcohol alone | 0.65 (0.52-0.81) | .001 | 0.70 (0.51-0.96) | .24 |

| HCV and alcohol | 0.74 (0.60-0.92) | .02 | 1.03 (0.78-1.35) | .90 |

| NASH | 0.69 (0.55-0.87) | .01 | 1.55 (1.13-2.12) | .14 |

| Other | 0.97 (0.69-1.36) | .98 | 0.93 (0.58-1.50) | .90 |

| MELD-Na score | ||||

| <20 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 20-24 | 1.01 (0.83-1.23) | .98 | 0.80 (0.60-1.06) | .38 |

| 25-29 | 1.04 (0.83-1.29) | .94 | 0.64 (0.47-0.88) | .14 |

| ≥30 | 0.70 (0.51-0.97) | .08 | 0.70 (0.46-1.06) | .37 |

| Cirrhosis complications | ||||

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 1.14 (0.97-1.34) | .22 | 1.06 (0.85-1.33) | .90 |

| Ascites | 1.17 (0.95-1.43) | .24 | 1.44 (1.02-2.02) | .24 |

| Varices | 0.89 (0.76-1.03) | .23 | 0.85 (0.67-1.08) | .43 |

| HCC | 0.79 (0.67-0.94) | .03 | 1.03 (0.82-1.28) | .90 |

| CirCom score | ||||

| 0 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 1 + 0 | 0.85 (0.71-1.01) | .15 | 1.09 (0.82-1.45) | .90 |

| 1 + 1 | 0.81 (0.62-1.05) | .21 | 0.94 (0.65-1.35) | .90 |

| ≥3 | 0.56 (0.44-0.72) | <.001 | 1.35 (1.03-1.77) | .24 |

| Depression | 1.02 (0.86-1.21) | .97 | 0.83 (0.66-1.05) | .38 |

| Anxiety | 0.91 (0.72-1.14) | .54 | 1.12 (0.82-1.53) | .90 |

| Sociodemographic characteristics | ||||

| Age group, y | ||||

| ≤54 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 55-59 | 0.77 (0.61-0.96) | .05 | 0.91 (0.66-1.26) | .90 |

| 60-64 | 0.77 (0.62-0.96) | .05 | 0.98 (0.73-1.32) | .95 |

| 65-70 | 0.75 (0.59-0.95) | .05 | 0.72 (0.51-1.02) | .31 |

| >70 | 0.47 (0.24-0.91) | .06 | 0.65 (0.25-1.67) | .73 |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Male | 1.40 (0.91-2.17) | .23 | 1.56 (0.79-3.08) | .48 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| African American | 1.01 (0.80-1.27) | .98 | 1.26 (0.93-1.72) | .38 |

| Hispanic | 0.85 (0.63-1.16) | .46 | 0.89 (0.58-1.38) | .90 |

| Other | 1.25 (0.80-1.94) | .46 | 0.89 (0.49-1.63) | .90 |

| Priority status | ||||

| 6-8 | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| 1-3 | 0.71 (0.57-0.88) | .008 | 0.95 (0.71-1.26) | .90 |

| 4-5 | 0.63 (0.51-0.78) | <.001 | 1.05 (0.79-1.39) | .90 |

| Insurance status | ||||

| VA-private | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| VA-Medicare | 0.91 (0.76-1.09) | .46 | 0.81 (0.64-1.02) | .34 |

| VA-Medicaid | 0.37 (0.18-0.73) | .01 | 0.96 (0.40-2.29) | .95 |

| VA only | 0.76 (0.60-0.95) | .05 | 0.79 (0.56-1.10) | .42 |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Midwest | 0.98 (0.70-1.38) | .98 | 0.90 (0.59-1.38) | .90 |

| Southeast | 0.59 (0.43-0.81) | .007 | 1.11 (0.76-1.61) | .90 |

| West | 0.40 (0.28-0.59) | <.001 | 1.01 (0.63-1.63) | .95 |

| Facility characteristics | ||||

| Complexity level | ||||

| Low/medium complexity | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| High complexity | 1.00 (0.67-1.48) | .99 | 0.54 (0.31-0.95) | .24 |

| Cirrhosis volume | ||||

| Low | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Medium | 1.18 (0.77-1.79) | .59 | 1.17 (0.65-2.09) | .90 |

| Medium-high | 1.42 (0.87-2.33) | .27 | 2.05 (1.00-4.21) | .28 |

| High | 1.30 (0.79-2.13) | .46 | 1.45 (0.71-2.99) | .66 |

| Transplant center | ||||

| Yes | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| No | 0.46 (0.31-0.68) | .001 | 0.69 (0.43-1.09) | .38 |

| Urban/rural | ||||

| Urban | 1 [Reference] | NA | 1 [Reference] | NA |

| Rural | 0.94 (0.80-1.11) | .59 | 0.96 (0.77-1.20) | .90 |

| Distance to closest transplant center, mi | ||||

| <200 | 1 [Reference] | NA | [1 [Reference] | NA |

| 200-499 | 0.97 (0.79-1.20) | .95 | 0.97 (0.74-1.28) | .90 |

| ≥500 | 1.01 (0.76-1.33) | .98 | 0.83 (0.57-1.20) | .66 |

Abbreviations: CirCom, Cirrhosis Comorbidity Index; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HR, hazard ratio; MELD-Na, Model for End-Stage Liver Disease with addition of sodium score; NA, not applicable; NASH, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis; VA, Veterans Affairs.

Nested models: false discovery rate–adjusted P value.

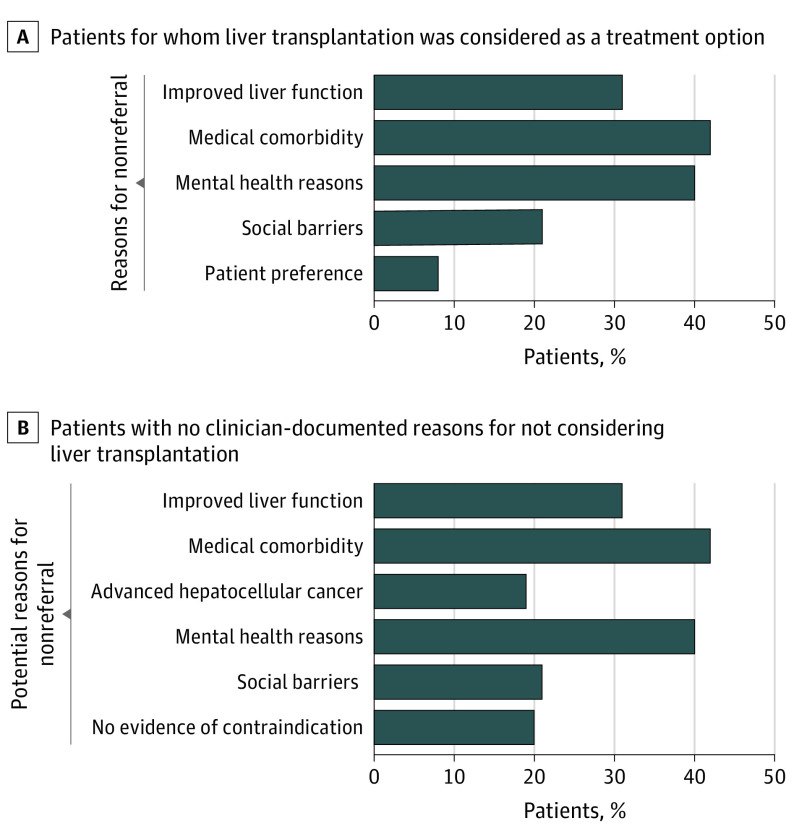

Reasons for Nonreferral Based on Medical Record Review

We reviewed the EMRs of 333 patients. Transplantation was mentioned as a potential treatment option in the EMR for 176 patients (53%) (Figure). Among 179 patients who were not referred, the most commonly cited medical reasons for nonreferral were improvement in liver function (33 patients [18%]), advanced hepatocellular carcinoma (25 patients [14%]), and age or comorbidity (17 patients [10%]). Concerns related to nonadherence to treatment recommendations were common. Ongoing alcohol use was cited in 68 patients (38%), and 30 patients (17%) had social reasons for nonreferral. Patient preference was documented in 14 patients (8%). A total of 63 patients (35%) had more than 1 reason. The most common combination included instances in which patients had medical comorbidity and mental health as well as social barriers.

Figure. Reasons for Nonreferral Among Patients in Whom Liver Transplant Was Considered as a Treatment Option (A) and Among Patients Without Clinician-Documented Reasons for Not Considering Liver Transplant (B).

We also examined reasons for nonreferral among 157 patients (47%) without any mention of transplantation by the treating clinician. Potential relative contraindications included improvement in liver dysfunction (48 of 157 patients [31%]), medical comorbidity (66 patients [42%]), alcohol or illicit drug use (63 patients [40%]), and social or contextual reasons (33 patients [21%]). In total, 33 of 157 patients (21%) did not have any evidence of contraindications to transplantation.

Discussion

Using data from a large cohort of patients with cirrhosis, we found that 1.6% underwent a liver transplant within 3 years of meeting clinical criteria. Even after being wait-listed, 42% did not receive an allograft. Although concerning, our results were similar to those of studies of other non-VA systems.2,3 Donor organ scarcity is the main reason for low access to organ transplant. However, rates of eventual organ transplant represent only a part of the overall picture. We found that the most common gaps were in the earlier steps of the complex transplantation process; 95% of patients with cirrhosis were not referred, and of those referred, approximately 40% were not wait-listed. These findings suggest that, in order to improve access to organ transplant, health care systems should consider tracking the full process.

Donor organ scarcity has engendered widespread agreement about the importance of equitable allocation by prioritizing those with the greatest immediate need (severe liver disease) and those who will benefit most (fewer contraindications).1 We found that less severe liver disease was indeed associated with lower rates of referral and wait-listing. We also found that medical and psychosocial comorbidity explained most instances of underreferral (Figure). Our results showed that although missed or delayed referrals were a barrier to organ transplant, a larger underlying challenge was support for and treatment of these often modifiable conditions.

Comorbidity did not fully explain low rates of referral and wait-listing, however. We also found several nonclinical factors associated with progression through the transplant process. Referral and wait-listing rates were the lowest for patients with the highest poverty levels. We also found that African American patients were less likely to be referred and wait-listed; longer time to referral accounted for much of the overall difference in wait-listing (Table 4). The VA is an integrated system with a strong emphasis on equal access to care. Because patients with cirrhosis are disproportionately impoverished and underinsured, these disparities may be more pronounced in patients who are treated in health care systems outside the VA.

System factors also contributed to disparities. We found that patients who received care at a facility without a transplant program were less likely to be wait-listed after referral. Transplant centers with multidisciplinary teams can better manage multiple barriers—including alcohol and social problems—to successfully transition patients from referral to wait-listing. Patients treated in facilities with transplant programs may have greater access to these services. Patients living in the Northeast had a significant advantage over their regional counterparts. Most of the VA transplant programs are located in the Northeast. These differences might improve with implementation of the VA MISSION Act, or Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks, that further expands access to care for veterans.

Factors associated with referral were different than those associated with placement on the waiting list or undergoing transplant in the nested models. Cirrhosis severity and comorbidity were associated with referral but not with wait-listing or transplant once referred. Most of the disparities by social factors, region, and place of care were related to lower rates of wait-listing after referral.

Limitations

Our study has limitations. Because this was an observational study, we could not draw causal inferences. Our study included mostly men with HCV or alcohol-related cirrhosis. The VA transplant programs rely on a national centralized referral process before assignment to individual regional transplant centers, further limiting generalizability to nonveterans. However, the integrated nature of the VA system is what allowed for the national longitudinal tracking of patients through the transplant process. Our data set did not capture transplant referrals that occurred outside the VA, and we might have missed some instances of referral. However, referral, wait-listing, and transplant rates were similar to those reported in a single center or regional analysis.2,7,8 Our primary analyses for wait-listing and transplant, although more inclusive, captured associations from the preceding steps. We created nested models to parse out associations at each sequential step, although these models were limited to patients referred within the VA, resulting in a potential selection bias. However, we believe these 2 approaches were complementary and support the overall findings. We examined a wide variety of factors and used time-updated values. MELD-Na data were missing in more than 30% of 6-month follow-up intervals. There were probably also other unmeasured and changing factors influencing clinicians’ decisions. To partially address this issue, we used medical record reviews to better understand the reasons for nonreferral. Future studies should focus on these dynamic factors.

Conclusions

Results of this cohort study suggest that few patients with advanced liver disease received referrals, were wait-listed, or underwent transplant, with the fewest patients at the referral step. Our study underscores the complexity of decision-making regarding referral and waiting list evaluation for liver transplant in patients with cirrhosis and multiple comorbidities. We have previously described the importance of taking an integrative approach to treatment planning,33 and clinicians who provide liver care can learn from similar cost-effective collaborative care models in other conditions.34,35,36

Although health systems routinely track rates and disparities for organ transplants among patients on waiting lists, results suggest that extending monitoring to the earlier stages could help improve equity and manage potentially modifiable barriers to transplantation.

eMethods 1. MELD-Na Score Calculation

eMethods 2. Ascertainment of Referral

eMethods 3. Handling Missing Data

eMethods 4. Frailty Models

eMethods 5. Taxonomy Used to Guide Abstraction of Reasons for Nonreferral

eTable 1. Association Between Clinical and Clinical-Patient Factors and Referral, Wait-Listing and Transplantation in Patients with Limited Comorbidity (CirCom 0 or 1).

eTable 2. Association Between Clinical and Clinical-Patient Factors and Referral, Wait-Listing and Transplantation in Patients Who Survived for >12 Months Following Meeting MELD-Na Criteria

eTable 3. Association Between Clinical and Clinical-Patient Factors and Referral, Wait-Listing and Transplantation in Patients With Persistently High MELD-Na (>15) Throughout Follow-Up

eTable 4. Association Between Clinical and Clinical-Patient Factors and Referral, Wait-Listing and Transplantation in Patients With Complete Data on all Covariates

eTable 5. Association Between Clinical and Clinical-Patient Factors and Referral, Wait-Listing and Transplantation in Patients Who Entered the Study Cohort Before vs After the Implementation of Organ Allocation Policy (Regional Share 35) in June 2013

eTable 6. Association Between Clinical and Clinical-Patient Factors and Referral, Wait-Listing and Transplantation in Patients Who Entered the Study Cohort Before vs After Revisions to Awarding Hepatocellular Cancer Exception Points (October 2015)

eFigure. Cohort Selection

References

- 1.Martin P, DiMartini A, Feng S, Brown R Jr, Fallon M. Evaluation for liver transplantation in adults: 2013 practice guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the American Society of Transplantation. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):1144-1165. doi: 10.1002/hep.26972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryce CL, Angus DC, Arnold RM, et al. Sociodemographic differences in early access to liver transplantation services. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(9):2092-2101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02737.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim WR, Lake JR, Smith JM, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2017 annual data report: liver. Am J Transplant. 2019;19(suppl 2):184-283. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axelrod DA, Guidinger MK, Finlayson S, et al. Rates of solid-organ wait-listing, transplantation, and survival among residents of rural and urban areas. JAMA. 2008;299(2):202-207. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moylan CA, Brady CW, Johnson JL, Smith AD, Tuttle-Newhall JE, Muir AJ. Disparities in liver transplantation before and after introduction of the MELD score. JAMA. 2008;300(20):2371-2378. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mindikoglu AL, Emre SH, Magder LS. Impact of estimated liver volume and liver weight on gender disparity in liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2013;19(1):89-95. doi: 10.1002/lt.23553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mazumder NR, Celaj S, Atiemo K, et al. Liver-related mortality is similar among men and women with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2020;73(5):1072-1081. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2020.04.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barritt AS IV, Telloni SA, Potter CW, Gerber DA, Hayashi PH. Local access to subspecialty care influences the chance of receiving a liver transplant. Liver Transpl. 2013;19(4):377-382. doi: 10.1002/lt.23588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sohn MW, Arnold N, Maynard C, Hynes DM. Accuracy and completeness of mortality data in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Popul Health Metr. 2006;4:2. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-4-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaplan DE, Dai F, Aytaman A, et al. ; VOCAL Study Group . Development and performance of an algorithm to estimate the Child-Turcotte-Pugh score from a national electronic healthcare database. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(13):2333-1341.e1, 6. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Buchanan P, et al. The quality of care provided to patients with cirrhosis and ascites in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Gastroenterology. 2012;143(1):70-77. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.03.038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kanwal F, Taylor TJ, Kramer JR, et al. Development, validation, and evaluation of a simple machine learning model to predict cirrhosis mortality. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2023780. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.23780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kanwal F, Tapper EB, Ho C, et al. Development of quality measures in cirrhosis by the Practice Metrics Committee of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology. 2019;69(4):1787-1797. doi: 10.1002/hep.30489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katz IR, McCarthy JF, Ignacio RV, Kemp J. Suicide among veterans in 16 states, 2005 to 2008: comparisons between utilizers and nonutilizers of Veterans Health Administration (VHA) services based on data from the National Death Index, the National Violent Death Reporting System, and VHA administrative records. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(suppl 1):S105-S110. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paying for Senior Care. VA priority groups qualifications . Caring, LLC. Updated May 2012. Accessed October 20, 2020. https://www.payingforseniorcare.com/veterans/veterans_priority_groups

- 16.Wang L, Porter B, Maynard C, et al. Predicting risk of hospitalization or death among patients receiving primary care in the Veterans Health Administration. Med Care. 2013;51(4):368-373. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31827da95a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kanwal F, Kramer JR, Ilyas J, Duan Z, El-Serag HB. HCV genotype 3 is associated with an increased risk of cirrhosis and hepatocellular cancer in a national sample of U.S. veterans with HCV. Hepatology. 2014;60(1):98-105. doi: 10.1002/hep.27095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kruse RL, Kramer JR, Tyson GL, et al. Clinical outcomes of hepatitis B virus coinfection in a United States cohort of hepatitis C virus-infected patients. Hepatology. 2014;60(6):1871-1878. doi: 10.1002/hep.27337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beste LA, Leipertz SL, Green PK, Dominitz JA, Ross D, Ioannou GN. Trends in burden of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma by underlying liver disease in US veterans, 2001-2013. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(6):1471-1482.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.07.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jepsen P, Vilstrup H, Lash TL. Development and validation of a comorbidity scoring system for patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):147-156. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Frayne SM, Miller DR, Sharkansky EJ, et al. Using administrative data to identify mental illness: what approach is best? Am J Med Qual. 2010;25(1):42-50. doi: 10.1177/1062860609346347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanwal F, Hoang T, Chrusciel T, et al. Association between facility characteristics and the process of care delivered to patients with hepatitis C virus infection. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(2):273-281. doi: 10.1007/s10620-013-2773-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groeneveld PW, Medvedeva EL, Walker L, Segal AG, Menno DM, Epstein AJ. Association between spending and survival of chronic heart failure across veterans affairs medical centers. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(7):e197238. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.7238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bynum JP, Bernal-Delgado E, Gottlieb D, Fisher E. Assigning ambulatory patients and their physicians to hospitals: a method for obtaining population-based provider performance measurements. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(1 pt 1):45-62. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00633.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goldberg DS, French B, Forde KA, et al. Association of distance from a transplant center with access to waitlist placement, receipt of liver transplantation, and survival among US veterans. JAMA. 2014;311(12):1234-1243. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steinman MA, Patil S, Kamat P, Peterson C, Knight SJ. A taxonomy of reasons for not prescribing guideline-recommended medications for patients with heart failure. Am J Geriatr Pharmacother. 2010;8(6):583-594. doi: 10.1016/S1543-5946(10)80007-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalbfleisch JD, Prentice R. . The Statistical Analysis of Failure Time Data. 2nd ed. Wiley Online Library: John Wiley & Sons; 2002. doi: 10.1002/9781118032985 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haller B, Schmidt G, Ulm K. Applying competing risks regression models: an overview. Lifetime Data Anal. 2013;19(1):33-58. doi: 10.1007/s10985-012-9230-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorfine M, Hsu L. Frailty-based competing risks model for multivariate survival data. Biometrics. 2011;67(2):415-426. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-0420.2010.01470.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Van Buuren S, Brand JPL, Groothuis-Oudshoorn CGM, Rubin DB. Fully conditional specification in multivariate imputation. J Stat Comput Simul. 2006;76(12):1049-1064. doi: 10.1080/10629360600810434 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moons KG, Donders RA, Stijnen T, Harrell FE Jr. Using the outcome for imputation of missing predictor values was preferred. J Clin Epidemiol. 2006;59(10):1092-1101. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.01.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y.. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Series B Methodol. 1995;57(1):289-300. doi: 10.1111/j.2517-6161.1995.tb02031.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Naik AD, Arney J, Clark JA, et al. Integrated model for patient-centered advanced liver disease care. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;18(5):1015-1024. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2019.07.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Watkins KE, Ober AJ, Lamp K, et al. Collaborative care for opioid and alcohol use disorders in primary care: the SUMMIT randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(10):1480-1488. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.3947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bekelman DB, Allen LA, McBryde CF, et al. Effect of a collaborative care intervention vs usual care on health status of patients with chronic heart failure: the CASA randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(4):511-519. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.8667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanwal F, Pyne JM, Tavakoli-Tabasi S, et al. A randomized trial of off-site collaborative care for depression in chronic hepatitis C virus. Health Serv Res. 2018;53(4):2547-2566. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods 1. MELD-Na Score Calculation

eMethods 2. Ascertainment of Referral

eMethods 3. Handling Missing Data

eMethods 4. Frailty Models

eMethods 5. Taxonomy Used to Guide Abstraction of Reasons for Nonreferral

eTable 1. Association Between Clinical and Clinical-Patient Factors and Referral, Wait-Listing and Transplantation in Patients with Limited Comorbidity (CirCom 0 or 1).

eTable 2. Association Between Clinical and Clinical-Patient Factors and Referral, Wait-Listing and Transplantation in Patients Who Survived for >12 Months Following Meeting MELD-Na Criteria

eTable 3. Association Between Clinical and Clinical-Patient Factors and Referral, Wait-Listing and Transplantation in Patients With Persistently High MELD-Na (>15) Throughout Follow-Up

eTable 4. Association Between Clinical and Clinical-Patient Factors and Referral, Wait-Listing and Transplantation in Patients With Complete Data on all Covariates

eTable 5. Association Between Clinical and Clinical-Patient Factors and Referral, Wait-Listing and Transplantation in Patients Who Entered the Study Cohort Before vs After the Implementation of Organ Allocation Policy (Regional Share 35) in June 2013

eTable 6. Association Between Clinical and Clinical-Patient Factors and Referral, Wait-Listing and Transplantation in Patients Who Entered the Study Cohort Before vs After Revisions to Awarding Hepatocellular Cancer Exception Points (October 2015)

eFigure. Cohort Selection