Abstract

This online survey study of US adults characterizes trends in coronavirus vaccine hesitancy and public trust in vaccination before and after COVID-19 vaccine availability in the US.

The development of vaccines showing high efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 has offered a way to protect against the health effects of the virus. Yet national surveys suggest that willingness to vaccinate declined throughout 2020 and may be insufficient to provide population immunity.1,2,3 Public trust in the development of vaccines and the government approval process represents a potential crucial reason for this hesitancy. This study tested changes in trust in vaccination and vaccine hesitancy.

Methods

Participants were from 7 waves of the probability-based Understanding America Study (UAS) of US adults,2,4 conducted between October 14, 2020, and March 29, 2021. The UAS is an internet panel in which panel members are invited to complete questionnaires every 14 to 28 days; internet-connected tablets are provided to households if necessary. The response rate from panel members in this study was 75% to 79% (Supplement).

Participants were asked how likely they were to get vaccinated against the coronavirus and were classed as hesitant (unsure or somewhat/very unlikely to vaccinate) or willing to vaccinate (somewhat likely/very likely to vaccinate or already vaccinated). Participants were also asked to rate how much they trust “the governmental approval process to ensure the COVID-19 vaccine is safe for the public” and “the process in general (not just for COVID-19) to develop safe vaccines for the public” (1 [fully trust] to 4 [do not trust]). Responses to both questions were highly correlated (r = 0.84). Responses were reverse scored and combined to form a single indicator of public trust in vaccination (ranging from 0-6).

Logistic regression analysis with cluster robust SEs followed by the Stata 17 margins postestimation command was used to estimate percentage-point differences in the level of vaccine hesitancy between October 2020 and March 2021, with statistical significance defined as 2-sided P < .05. All analyses incorporated sampling weights to ensure each survey wave remained nationally representative despite missing data owing to nonresponse (Supplement). Participants provided informed consent via the UAS website and data collection was approved by the University of Southern California institutional review board.

Results

In total, 7420 participants provided 42 154 survey responses (mean, 5.7 of 7 waves completed). Estimates of vaccine hesitancy declined significantly by 10.8 percentage points (95% CI, 8.9-12.7), from 46% in October 2020 to 35.2% in March 2021 (Table, Figure). Significant declines in estimates of hesitancy were observed across demographic groups and were largest among Hispanic (15.8 percentage point decrease, from 52.3% to 36.5%) and Black participants (20.9 percentage point decrease, from 63.9% to 43%). In March 2021 hesitancy was high among adults aged 18-39 years (44.1%), those without a degree (42.9%), and households earning $50 000 or less (43.7%).

Table. Changes in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Public Trust in Vaccination Between October 14, 2020, and March 29, 2021, in the Understanding America Study.

| Demographic characteristic | COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, % (95% CI)a,b | Public trust in vaccination, mean (95% CI)c,d | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey wave | Change in hesitancy by March 2021 | Survey wave | Change in trust by March 2021 | ||||

| October 2020 (n = 6016) | March 2021 (n = 6035) | October 2020 (n = 6016) | March 2021 (n = 6035) | ||||

| Overall sample | 46.0 (44.2 to 47.7) | 35.2 (33.4 to 36.9) | −10.8 (−12.7 to −8.9) | 2.6 (2.5 to 2.6) | 3.0 (2.9 to 3.0) | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.5) | |

| Age, y | |||||||

| 18-39 | 50.7 (47.5 to 53.8) | 44.1 (40.8 to 47.3) | −6.6 (−10.1 to −3.2) | 2.4 (2.3 to 2.5) | 2.7 (2.6 to 2.9) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.5) | |

| 40-59 | 49.7 (46.8 to 52.6) | 38.6 (35.6 to 41.6) | −11.1 (−14.2 to −8.0) | 2.4 (2.3 to 2.5) | 2.8 (2.6 to 2.9) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) | |

| ≥60 | 36.2 (33.5 to 39.0) | 21.0 (18.6 to 23.4) | −15.2 (−18.1 to −12.4) | 3.0 (2.9 to 3.1) | 3.5 (3.4 to 3.6) | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.6) | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Men | 39.9 (37.3 to 42.4) | 30.7 (28.2 to 33.2) | −9.3 (−11.9 to −6.4) | 2.8 (2.7 to 2.9) | 3.2 (3.1 to 3.3) | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.5) | |

| Women | 51.8 (49.4 to 54.1) | 39.4 (37.0 to 41.8) | −12.4 (−15.0 to −9.7) | 2.3 (2.3 to 2.4) | 2.7 (2.6 to 2.8) | 0.4 (0.3 to 0.5) | |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 42.4 (40.4 to 44.3) | 34.8 (32.8 to 36.8) | −7.6 (−9.6 to −5.5) | 2.8 (2.7 to 2.8) | 3.1 (3.0 to 3.1) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) | |

| Hispanic | 52.3 (47.0 to 57.5) | 36.4 (31.2 to 41.7) | −15.8 (−21.8 to −9.8) | 2.4 (2.2 to 2.6) | 3.0 (2.7 to 3.2) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.8) | |

| Black | 63.9 (58.7 to 69.2) | 43.0 (37.3 to 48.7) | −20.9 (−27.2 to −14.6) | 1.7 (1.5 to 1.8) | 2.3 (2.1 to 2.5) | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.8) | |

| Othere | 33.7 (26.7 to 40.8) | 20.4 (14.3 to 26.6) | −13.3 (−20.9 to −5.8) | 3.0 (2.8 to 3.2) | 3.5 (3.2 to 3.8) | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.7) | |

| College degree | |||||||

| No | 54.6 (52.3 to 56.8) | 42.9 (40.6 to 45.2) | −11.7 (−14.2 to −9.1) | 2.3 (2.2 to 2.4) | 2.5 (2.5 to 2.6) | 0.2 (0.2 to 0.3) | |

| Yes | 30.5 (27.9 to 33.0) | 20.9 (18.6 to 23.2) | −9.6 (−12.1 to −7.1) | 3.1 (3.0 to 3.2) | 3.8 (3.7 to 3.9) | 0.7 (0.6 to 0.8) | |

| Income, $ | |||||||

| <50 000 | 54.0 (51.3 to 56.6) | 43.7 (40.9 to 46.4) | −10.3 (−13.3 to −7.3) | 2.2 (2.1 to 2.3) | 2.5 (2.4 to 2.6) | 0.3 (0.2 to 0.4) | |

| ≥50 000 | 39.7 (37.5 to 41.9) | 28.2 (26.1 to 30.4) | −11.5 (−13.8 to −9.1) | 2.9 (2.8 to 3.0) | 3.4 (3.3 to 3.5) | 0.5 (0.4 to 0.6) | |

Vaccine hesitancy is defined as being unsure or somewhat or very unlikely to be vaccinated against COVID-19.

Estimates are derived from predicted probabilities calculated after logistic regression with cluster robust SEs.

Public trust in vaccination ranged from 0 (do not trust development/approval processes) to 6 (fully trust development/approval processes).

Estimates are from linear regression with cluster robust SEs.

Race/ethnicity was self-reported by panel members. The other race/ethnicity group includes Asian, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian orother Pacific Islander, which were combined owing to small group sizes.

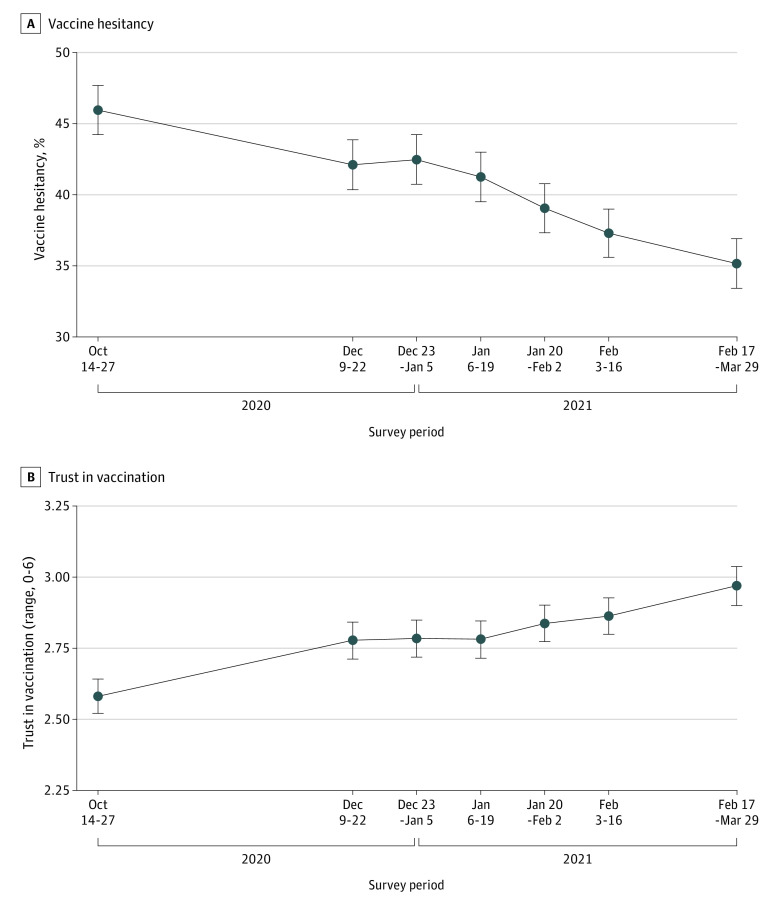

Figure. Changes in COVID-19 Vaccine Hesitancy and Public Trust in Vaccination Across 7 Waves of the Understanding America Study Conducted Between October 14, 2020, and March 29, 2021.

Based on an analysis of 42 154 observations on 7420 participants; error bars indicate 95% CIs. Vaccine hesitancy is defined as being unsure or somewhat or very unlikely to be vaccinated against COVID-19. Public trust in vaccination ranges from 0 (do not trust development/approval processes) to 6 (fully trust processes). Details of survey date ranges are provided in the Supplement.

Estimates of public trust in vaccination were low across all demographic groups in October 2020 (1.7 to 3.1 on a 0-6 scale) and increased significantly across all groups by March 2021 (Table). The largest increases were reported by Black and Hispanic participants (0.6-point increase) and those with a college degree (0.7-point increase).

Discussion

After increased reluctance to vaccinate in 2020,1,2,3 this nationally representative study showed a longitudinal decline in reported vaccine hesitancy in late 2020 and early 2021. Reduced hesitancy occurred in tandem with the regulatory approval of COVID-19 vaccines and rollout of mass vaccination programs. A significant decline in vaccine hesitancy was reported across all demographic groups, especially Black and Hispanic participants. This decrease is important because COVID-19 vaccine acceptance has been particularly low among these groups, who have experienced a disproportionate burden of severe illness and death because of COVID-19.3,5,6 Declines in hesitancy were reported alongside an increase in public trust in vaccine development and the governmental approval process.

Despite these gains, in March 2021 estimates of vaccine hesitancy remained high, especially among young adults and Black and low socioeconomic status participants. Further steps are needed to build public trust, extend outreach and educational programs, and increase vaccination opportunities to ensure high levels of vaccination uptake.

The study is limited by the low UAS panel recruitment rate, participation by community-dwelling adults comfortable completing internet-based surveys in English or Spanish, and reliance on self-reported measures.

Section Editor: Jody W. Zylke, MD, Deputy Editor.

eMethods. Details of survey recruitment rate and survey weights

eTable. Survey dates and panel member response rates for survey waves

References

- 1.Daly M, Robinson E. Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 in the US: representative longitudinal evidence from April to October 2020. Am J Prev Med. 2021;60(6):766-773. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.01.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Szilagyi PG, Thomas K, Shah MD, et al. National trends in the US public’s likelihood of getting a COVID-19 vaccine—April 1 to December 8, 2020. JAMA. 2020;325(4):396-398. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.26419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson E, Jones A, Lesser I, Daly M. International estimates of intended uptake and refusal of COVID-19 vaccines: a rapid systematic review and meta-analysis of large nationally representative samples. Vaccine. 2021;39(15):2024-2034. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.02.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kapteyn A, Angrisani M, Bennett D, et al. Tracking the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the lives of American households. Surv Res Methods. 2020;14(2):179-186. doi: 10.18148/srm/2020.v14i2.7737 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lopez L III, Hart LH III, Katz MH. Racial and ethnic health disparities related to COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(8):719-720. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.26443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gold JAW, Rossen LM, Ahmad FB, et al. Race, ethnicity, and age trends in persons who died from COVID-19—United States, May–August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(42):1517-1521. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6942e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMethods. Details of survey recruitment rate and survey weights

eTable. Survey dates and panel member response rates for survey waves