Abstract

Analytical performance and efficiency are two pivotal issues for developing an on-site and real-time aptasensor for cadmium (Cd2+) determination. However, suffering from redundant preparations, fabrications, and incubation, most of them fail to well satisfy the requirements. In this work, we found that fluorescence intensity of 6-carboxyfluorescein(FAM)-labeled aptamer (FAM-aptamer) could be remarkably amplified by 3-(N-morpholino)propane sulfonic acid (MOPS), then fell proportionally as Cd2+ concentration introduced. Importantly, the fluorescence variation occurred immediately after addition of Cd2+, and would keep stable for at least 60 min. Based on the discovery, a facile and ultra-efficient aptasensor for Cd2+ determination was successfully developed. The sensing mechanism was confirmed by fluorescence pattern, circular dichroism (CD) and intermolecular interaction related to pKa. Under the optimal conditions, Cd2+ could be determined rapidly from 5 to 4000 ng mL−1. The detection limit (1.92 ng mL−1) was also lower than the concentration limit for drinking water set by WHO and EPA (3 and 5 ng mL−1, respectively). More than a widely used buffer, MOPS was firstly revealed to have fluorescence amplification effect on FAM-aptamer upon a given context. Despite being sensitive to pH, this simple, high-performance and ultra-efficient aptasensor would be practical for on-site and real-time monitoring of Cd2+.

Keywords: aptasensor, cadmium, MOPS, fluorescence, FAM

1. Introduction

Cadmium (Cd2+) is an important heavy metal and widely used in agriculture and industry [1]. However, this element is highly toxic, non-biodegradable, and bio-accumulative, which seriously threatens ecological security and human health [2]. It has been reported that continuous exposure to Cd2+ (even in trace concentration) may cause pathological disorders in entire human body system [3]. To this end, the regulatory guidance for Cd2+ in drinking water has been formulated by World Health Organization (WHO, 3 ng mL−1) and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA, 5 ng mL−1), respectively. In addition, various analytical techniques including electrothermal atomization atomic absorption spectroscopy (ET-AAS) [4,5,6], inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS) [7,8,9,10] and graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrometry (GFAAS) [11,12], have been employed to determine Cd2+ in laboratory. As far as on-site and real-time determination and monitoring of Cd2+ in fields is concerned, the challenge comes as how to develop a convenient method without compromising performance and efficiency.

In recent decades, aptamer-based biosensors, i.e., aptasensors, have achieved substantial attention as robust detection tools. Aptamers are short nucleic acid oligomers selected by SELEX (systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment) [13,14], which in turn enables them to recognize targets sensitively and selectively [15]. They are not only easy to synthesize, modify and store, but possess high affinity, low immunogenicity and toxicity [16]. By coupling those advantages with different signal output techniques, numerous aptasensors have been developed for sensitive detection of cadmium [17,18,19,20,21], lead [22,23,24,25,26], mercury [27,28,29,30], arsenic [31,32], and other heavy metals [33,34]. These aptasensors are accurate and sensitive, but most of them suffer from relatively poor efficiency. Banerjee reported a nanomaterial-based optical probe for sensitive determination of arsenic(III), where a low limit of detection (LOD) of 0.86 ppb was achieved. However, the synthesis and functionalization of the nanomaterial, Fe3O4(core)-Au(shell) nanocomposite, would consume more than 72 h. [35]. Similarly, relatively expensive instruments and toxic chemicals were required for the synthesis of TiO2-g-C3N4 before multistage fabrication of an impedimetric aptasensor [36]. In another case, the time cost for incubation even went up to 19 h for every measurement [19], where efficiency was inevitably lost. For the sake of fitting the aforementioned requirements for on-site and real-time monitoring, it is of paramount importance to develop a simpler and much more efficient aptasensor for Cd2+ determination.

In this work, we found that fluorescence intensity of FAM-aptamer could be remarkably enhanced by MOPS (a widely used buffer in bioassays), then dropped proportionally as a function of Cd2+ concentration introduced. Louder than that, the result obtained spoke the fluorescence variation would occur immediately after addition of Cd2+ into sensing system, and keep stable for at least 60 min. As the preparations for various nanoparticles and reagents, redundant procedures for fabrication and incubation were totally omitted, both performance and efficiency required for on-site and real-time determination of Cd2+ were satisfied perfectly. Based on the fresh discovery, a facile aptasensor for instantaneous determination of Cd2+ was developed and its schematic diagram was presented in Scheme 1.

Scheme 1.

Schematic view of a facile and ultra-efficient aptasensor for instantaneous determination of Cd2+ based on fluorescence amplification effect of MOPS on FAM-aptamer.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Apparatus

The sequence of cadmium-specific aptamer (FAM-aptamer) was derived from its parent [21] by adding five nucleotides and labeling a FAM fluorophore at 3′ end: 5′-GGA CTG TTG TGG TAT TAT TTT TGG TTG TGC AGT CC-FAM−3′. The sequence was synthesized and purified by Sangon Biotech Co. (Shanghai, China). Standard solutions (1000 mg L−1) of Cd2+, Hg2+, and Pb2+ were purchased from Merck Co. (Germany). Other chemicals used in selectivity and recovery study, i.e., compounds with cationic of Ag+, Fe3+, Zn2+, As5+, As3+, Al3+, Ba2+, Sn2+, NH4+, Ca2+, Na+, and K+ were obtained from commercial sources and used without further purification. MOPS was obtained from Sangon Biotech Co. as well.

The fluorescence intensity was recorded by A Microplate Spectro-photometer M200 Pro (Tecan Group Ltd., Männedorf, Switzerland) at room temperature, with an excitation (emission) wavelength of 472 (520) nm and an excitation (emission) bandwidth of 9 (20) nm respectively. A J−1500 circular dichroism (CD) spectrometer (Jasco, Tokyo, Japan) was employed to characterize the steric configuration of FAM-aptamer, scanning from 190 to 300 nm with a bandwidth of 2 nm (200 nm min−1) three times. The response to MOPS was treated as baseline. All the ultrapure water utilized in this work was prepared by a Millipore-MilliQ system (Millipore Inc., Bedford, MA, USA).

2.2. Optimization of Experimental Conditions

Addition order for FAM-aptamer and Cd2+ was investigated. Firstly, 10 μL FAM-aptamer (20 nM, final concentration) was mixed into 230 μL MOPS (10 mM, pH 8.0), followed by addition of 10 μL Cd2+. After interaction, 200 μL from the resulting solution was transferred to a 96-well microplate for fluorescence measurement. The final concentrations of Cd2+ were set at two levels, a low level of 40 ng mL−1 and a high level of 200 ng mL−1. Similarly, assays with reversed addition order for FAM-aptamer and Cd2+ were then conducted as a contrast. According to the order of addition, they were denoted as MOPS + FAM-aptamer + Cd2+ and MOPS + Cd2+ + FAM-aptamer, respectively. Unless mentioned, all assays in this work were performed with a 250 μL sensing system, i.e., 10 μL aqueous sample containing Cd2+ and 10 μL FAM-aptamer mixed in 230 μL MOPS, then followed the same protocol for fluorescence measurement.

For optimization of concentration and pH of MOPS, a two-factor experiment with 5 levels (25 treatments in all) was operated. First, 50 mM MOPS was prepared and then diluted to 0.1, 1.0, 5.0, 10.0, and 20.0 mM with ultrapure water. Subsequently, the pH values of the resulting solutions were adjusted to 6.0, 7.0, 8.0, 9.0, and 10.0 by NaOH (1mM) respectively. Each treatment was marked as concentration * pH, e.g., 0.1 * 8.0 represented the treatment of 0.1 mM MOPS with a pH value of 8.0. Then within a 250 μL sensing system, the assays under different treatments of MOPS, as well as fluorescence measurement were performed in optimal addition order. The final concentrations of FAM-aptamer and Cd2+ were 20 nM and 200 ng mL−1, respectively.

To optimize incubation time, two experiments, i.e., (1) different concentrations of MOPS (1, 5, and 10 mM, pH 9.0) mixed with 20 nM FAM-aptamer and 200 ng mL−1 Cd2+ and (2) 5mM MOPS (pH 9.0) mixed with 20 nM FAM-aptamer and various concentrations of Cd2+ (10, 50, 100, and 200 ng mL−1), were respectively conducted at room temperature and completed by fluorescence measurement.

2.3. Sensitivity and Selectivity of the Sensing System

The sensitivity and selectivity of the sensing system were investigated under optimal conditions. Briefly, in sensitivity test, assays with increasing concentrations of Cd2+ (5–4000 ng mL−1) were performed. On the other hand, the selectivity was evaluated by the performance of sensing system under potential interferences including Pb2+, As5+, As3+, Ba2+, Ca2+, Al3+, Sn2+, NH4+, Na+, K+, Fe2+, and Fe3+.

2.4. Application in Water Samples

A recovery test was first implemented with ultrapure water spiked with multiple ions including Cd2+, Pb2+, Hg2+, As5+, As3+, Na+, K+, Al3+, Fe2+, Sn2+, and NH4+ with various concentrations. The recovery was calculated based on the spiked concentration of Cd2+ and the linear regression equation obtained in Section 2.3. No additional pretreatment was required before a measurement. Furthermore, freshwater samples from a tributary of Huangpu River were collected to assess the feasibility of the aptasensor against a complex matrix by another recovery test. The river water samples were firstly filtered through 0.22 µm membranes after spiking Cd2+, then measured following the protocol.

2.5. Calculation of Fluorescence Quenching and Fluorescence Quenching Efficiency

The fluorescence intensity of samples containing Cd2+ or interferences was recorded as F. F0 was assigned to the fluorescence intensity of a blank containing FAM-aptamer and MOPS only, where 10 μL aqueous sample containing Cd2+ was replaced by 10 μL ultrapure water. Fluorescence quenching (∆F) was defined as the difference between F0 and F, which can be calculated as ∆F = F0 − F; thus, fluorescence quenching efficiency (∆F/F0) can be calculated as ∆F/F0 = (F0 − F)/F0.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sensing Mechanism

In current work, an interesting discovery that stood out was the fluorescence amplification effect of MOPS on FAM-aptamer, followed by a proportional decrease in fluorescence intensity as the concentration of Cd2+ added subsequently. As the results shown in Figure 1a, FAM-aptamer released feeble fluorescence with an intensity around 400, and MOPS showed almost no fluorescence in absence of FAM-aptamer and Cd2+. However, a significantly stronger fluorescence could be recorded when FAM-aptamer and MOPS were mixed. The fluorescence intensity was enhanced by more than 22 times and mounted up beyond 9000. No previous study was reported on this phenomenon. We speculated that there were probably two reasons. On one hand, it was obvious that the 3′ end of FAM-aptamer was complementary to its 5′ end. The FAM-aptamer in random coil status might be inclined to self-stack by base pairing without buffer, enabling chances to weaken and even screen the fluorescence to a certain extent. On the other hand, MOPS also offered microenvironment for protonation and deprotonation while dispersing FAM-aptamer homogeneously as a buffer. The resulting charged microspecies of FAM interacted with deprotonated MOPS through electrostatic force and hydrogen bond (mainly resulting from N and O atoms), enabling energy transfer induced by electric dipoles and then fluorescence enhancement. Afterwards, with addition of 200 ng mL−1 Cd2+, the fluorescence of system dropped dramatically to around 3000. This could be ascribed to the specific recognition of FAM-aptamer to Cd2+. Since Cd2+ was added in the aforementioned system, the FAM-aptamer disengaged themselves from the interaction with MOPS and was induced to form a stem-loop structure (partial hybridization by six base-pairs) to bind Cd2+ with higher affinity simultaneously [37]. This formation prevented MOPS from approaching FAM fluorophore by steric effect, leading to reduced energy transfer and weak fluorescence. This resulting fluorescence pattern demonstrated the feasibility of the proposed method. Based on the fluorescence variation proportional to Cd2+ concentration added, a facile and sensitive aptasensor for Cd2+ determination was successfully developed. The schematic was displayed in Scheme 1. MOPS has been reported to own surfactant-like effect [38,39] and be able to inhibit catalytic activity [40]. The fresh discovery in current work, that was fluorescence amplification effect on FAM-aptamer, further advanced our knowledge of MOPS more than a widely used buffer.

Figure 1.

(a) Fluorescence emission spectra of FAM-aptamer, MOPS, MOPS + FAM-aptamer, and MOPS + FAM-aptamer + Cd2+ (FAM-aptamer, 20 nM; MOPS, 5mM, pH 9.0; Cd2+, 200 ng mL−1). (b) CD spectra of the FAM-aptamer (500 nM) in the absence and presence of 100 ng mL−1 Cd2+.

Then, CD measurements were applied to investigate the conformational alteration of FAM-aptamer in presence of Cd2+. As shown in Figure 1b, the FAM-aptamer presented a negative peak around 250 nm and a positive peak at 275 nm, which was in accordance with the spectra of previous study [21]. After introduction of 100 ng mL−1 Cd2+, the negative peak decreased while an enhanced positive peak around 275 nm was observed, indicating the binding of FAM-aptamer to Cd2+ through conformation change.

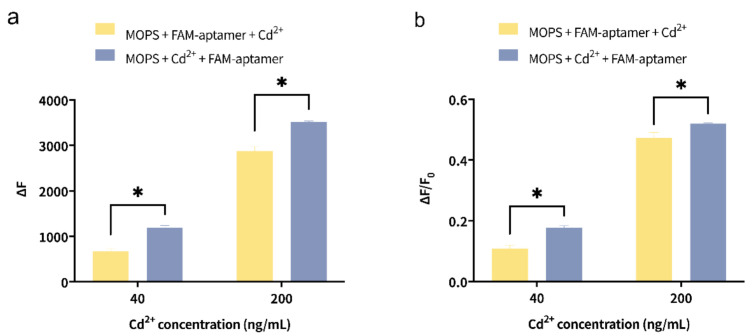

3.2. Optimization of Addition Order

There were two interactions within this sensing system, i.e., the specific recognition of FAM-aptamer to Cd2+ and fluorescent amplification of MOPS on FAM-aptamer. As FAM-aptamer was involved in both two interactions, the optimization of addition order was of significance.

As the results shown in Figure 2, ∆F and ∆F/F0 of MOPS + Cd2+ + FAM-aptamer were significantly higher than that of MOPS + FAM-aptamer + Cd2+ (p < 0.05) upon both low and high concentration of Cd2+. This could be explained as follows. When FAM-aptamer was firstly mixed into MOPS, they dispersed homogeneously at the very beginning, followed by interaction to initiate energy transfer. Therefore, prior to binding Cd2+ added subsequently, they needed to disengage themselves from the interaction. In other words, the interaction between FAM-aptamer and MOPS retarded the specific recognition of FAM-aptamer to Cd2+ in the addition order of MOPS + FAM-aptamer + Cd2+. However, there was insufficient evidence to support the interaction between MOPS and Cd2+ by now. Due to higher affinity to Cd2+, it would be easier for FAM-aptamer to bind Cd2+ if Cd2+ was added before FAM-aptamer. Hence the addition order of MOPS + Cd2+ + FAM-aptamer was adopted in following assays.

Figure 2.

Effect of addition order on (a) fluorescence quenching (∆F) and on (b) fluorescence quenching efficiency (∆F/F0). * indicates significant difference (p < 0.05, n ≥ 3).

3.3. Optimization of Concentration and pH of MOPS

As a key component to the sensing system, the effects of concentration and pH of MOPS on fluorescence quenching were simultaneously factored into overall investigation, and then plotted as two heatmaps (Figure 3a,b). For this assay, the pH of MOPS seemed to be more significant. On one hand, FAM was reported to be pH sensitive [41]. On the other hand, the pH directly determined the degree of protonation and deprotonation, then influenced energy transfer. Therefore, to further understand the effect, the pKa values of both FAM and MOPS were involved and evaluated with Marvin Sketch software (Figure 3c,e) [42].

Figure 3.

Interactive effect of concentration and pH of MOPS on (a) fluorescence quenching (∆F) and (b) fluorescence quenching efficiency (∆F/F0). (c) MOPS molecule with pKa values of O and N sites and (d) distribution of its major charged microspecies upon varied pH. (e) FAM fluorophore molecule with pKa values of O sites and (f) distribution of its charged microspecies upon varied pH.

As shown in Figure 3a, ∆F was mostly less than 500 when pH ≤ 7, which could be explained from the aspect of pKa and pH. Figure 3c indicated the pKa of O and N site in MOPS was ~−0.96 and ~6.88, respectively. When pH ≤ 7, autoprotolysis of MOPS dominated and the resulting microspecies (I) (Figure 3d) was simultaneously positively charged on N site and negatively charged on O site. The strong intermolecular electrostatic adsorption led to self-aggregation of MOPS and less interaction with FAM fluorophore. Although a treatment like 0.1*6 presented excellent performance in ∆F/F0 in this area, its low ∆F was easily distracted by background noise or interferences, then failed to determine Cd2+ accurately. While pH lay in the range from 8 to 10, the ∆F/F0 increased firstly and then decreased as increasing concentration of MOPS at a certain pH. Upon all the treatments here, the treatment of 5.0*9.0 stood out with the highest ∆F and a ∆F/F0 exceeding 0.67 (Figure 3a,b). As shown in Figure 3d,f, the majority of MOPS deprotonated to microspecies (II) while three different deprotonated forms of FAM coexisted at this stage. This phenomenon demonstrated that fluorescence variation of the electric dipole-induced energy transfer was mainly affected by microspecies (II) of MOPS and microspecies (III) of FAM, the most abundant deprotonated form at pH 9.0. We reasoned the energy transfer intensity was like a game of electrostatic force, hydrogen bond, and steric effect. The stronger the hydrogen bond, the tighter the adsorption, accompanying by more intense steric effect and electrostatic repulsion. The appropriate deprotonation degree of three O sites in microspecies (III) of FAM could tune this game to the best performance in energy transfer. Finally, given that the formation of cadmium hydroxyl might confuse the determination of Cd2+, the treatments upon pH > 10 were ruled out [43]. In summary, 5 mM MOPS with pH 9.0 was selected and used in following assays.

3.4. Optimization of Incubation Time

In order to achieve the best performance and efficiency of the proposed aptasensor, experiments were conducted to optimize incubation time. The results obtained were summarized in Figure 4. First of all, the highest ∆F/F0 value under the treatment of 5 mM MOPS (pH 9.0) further supported the conclusion in Section 3.3 (Figure 4a). However, the most striking finding was ∆F/F0 value almost remained constant from the very beginning and would keep stable for 60 min at least (Figure 4b). These results demonstrated the remarkable long-term stability of the aptasensor. Louder than that, it spoke that the high-performance sensing could be instantly accomplished, suggesting the aforementioned goal of on-site and real-time determination could be well achieved with this robust aptasensor.

Figure 4.

Stability of fluorescence quenching efficiency (∆F/F0) in time scale under (a) different concentrations of MOPS (1, 5, and 10 mM, pH 9.0) mixed with 20 nM FAM-aptamer and 200 ng mL−1 Cd2+, and under (b) 5mM MOPS (pH 9.0) mixed with 20 nM FAM-aptamer and various concentrations of Cd2+(10, 50, 100, and 200 ng mL−1) at room temperature. (n ≥ 3).

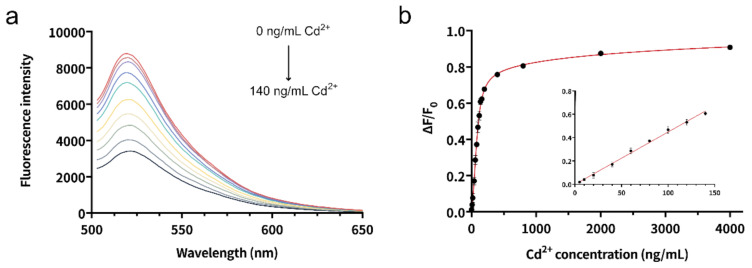

3.5. Sensitivity

Under the optimal experimental conditions, the analytical performance of the aptasensor was investigated. At first, the sensitivity was evaluated by adding increasing concentrations of Cd2+ into sensing system. As depicted in Figure 5a, the fluorescence intensities of the aptasensor decreased gradually as a function of Cd2+ concentrations added. The ∆F/F0 was plotted against Cd2+ concentration from 5 to 4000 ng mL−1 (Figure 5b), and the inset presented a good linear relationship upon the concentration range of 5 to 140 ng mL−1. The obtained linear regression equation was shown below:

| ∆F/F0 = 0.0045C − 0.0015 (R2 = 0.996) |

Figure 5.

(a) Fluorescence emission spectra of the aptasensor on exposure to 0, 5, 10, 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120, and 140 ng mL−1 Cd2+. (b) Calibration curves of the aptasensor for Cd2+ determination. (Insert) Initial linear responses in the range of 5−140 ng mL−1 Cd2+. (n ≥ 4).

C: Cd2+ concentration; R2: correlation coefficient.

The LOD was estimated as 1.92 ng mL−1 (3σ/slope), which was lower than the maximum concentration limit set by WHO (3 ng mL−1) and EPA (5 ng mL−1), respectively. Moreover, a comparison of existing aptamer-based methods for Cd2+ determination was conducted (Table 1). The table showed that in most cases, efficiency was severely limited by incubation beyond hours, even if time cost for preparations of nanoparticles and multistage fabrication procedures were not yet included. With current aptasensor, however, incubation was needless, curtailing the total time cost dramatically. Given its simplicity and near-perfect performance in efficiency, a comparable LOD with other approaches was acceptable. These results not only revealed the superior efficiency of the aptasensor, but also demonstrated its promising future for real-time monitoring of Cd2+ in fields.

Table 1.

Comparison of different aptamer-based approaches for Cd2+ determination.

| Approaches | Linear Range (ng mL−1) | LOD (ng mL−1) | Incubation Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorimetry | 1.12–44.8 | 0.52 | 65 min | [21] |

| 1–400 | 1 | 80 min | [44] | |

| 0.056–22.48, 33.72–112.41 | 0.017 | 105 min | [45] | |

| 1.12 × 10−3–112 | 1.12 × 10−3 | >150 min | [46] | |

| 5–100 | 2.4 | 50 min | [47] | |

| Electrochemistry | 0.1–1000 | 0.05 | >45 min | [48] |

| 28–112 | 10.3 | >19 h | [19] | |

| Glucometer | 2.24 × 10−3–22.4 | 5.6 × 10−4 | 180 min | [17] |

| Fluorometry | 0–112 | 4.48 | 30 min | [20] |

| 100–105 | 0.038 | 20 min | [49] | |

| 0.81–22.4, 22.4–560 | 0.24 | 30 min | [18] | |

| 1.12–224.82 | 0.34 | 70 min | [50] | |

| 5–140 | 1.92 | <1 min | This work |

3.6. Selectivity

The selectivity of the method was evaluated by recording the response of the aptasensor towards other potential interfering ions in absence and presence of Cd2+, respectively. Due to high affinity to Cd2+, the other ions could hardly induce the disengagement of FAM-aptamer from MOPS despite their excessively high concentrations. Figure 6 showed all other ions had ∆F/F0 lower than 0.2, while the ∆F/F0 for Cd2+ approached 0.7. After the introduction of Cd2+ to the above individual ion sensing system and the mixture, the sharply enhanced ∆F/F0 confirmed the high selectivity of the aptasensor for Cd2+.

Figure 6.

Selectivity of the aptasensor towards other potential interfering ions in absence and presence of Cd2+. The concentration of Cd2+ was 200 ng mL−1, and that of all other ions was 400 ng mL−1. (n ≥ 3).

Furthermore, it was reported that K+, Na+, and Pb2+ could induce a G-rich ssDNA to form a structure of G-quartet (or G-quadruplex), then significantly quenched the fluorescence of fluorophore [51]. The significant differences here basically neutralized the concerns about G-quadruplex, as well as the concerns about distraction of metal ions-directed fluorescence quenching [52].

3.7. Reproducibility

As the merits of simplicity and robustness that the system possessed, the reproducibility was well guaranteed by nature. It was evaluated by 10 assays within 200 ng mL−1 Cd2+ under identical conditions. The ∆F/F0 value obtained with a relative standard deviation (RSD) of 0.74% totally eliminated the concerns over reproducibility.

3.8. Determination of Cd2+ in Water Samples

The feasibility of the current aptasensor was evaluated by Cd2+ determination in several spiked ultrapure water samples containing various concentrations of Cd2+ and other interfering ions. As the results exhibited below (Table 2), the recoveries with the artificial samples ranged from 96.79% to 105.22% with RSD values of 0.64% to 3.12%, indicating its good analytical performance against interfering ions.

Table 2.

Determination of Cd2+ in artificial water samples (n ≥ 3).

| Spiked (ng mL−1) |

Interfering Ions (ng mL−1) |

Found (ng mL−1) |

Recovery (%) |

RSD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | Pb2+ (10), Hg2+ (10), As5+ (10), As3+ (10), Na+ (10), K+ (10), Al3+ (10), Fe2+ (10), Sn2+ (10), NH4+ (10) |

9.68 | 96.79 | 2.36 |

| 50 | Hg2+ (50), As5+ (50), As3+ (50), Na+ (50), K+ (50), Al3+ (50), Fe2+ (50), Sn2+ (50), NH4+ (50) |

48.43 | 96.85 | 3.12 |

| 100 | Pb2+ (100), As5+ (100), As3+ (100), Na+ (100), K+ (100), Al3+ (100), Fe2+(100), Sn2+ (100), NH4+ (100) |

105.22 | 105.22 | 0.64 |

Note: the numbers in parentheses after each ion show the final concentration of the ions added.

Environmental samples were generally more complicated, where a variety of both organic and inorganic interferences beyond the aforementioned ions existed. To further assess the practicability of the aptasensor against a complex matrix, freshwater samples from a tributary of Huangpu River were collected for another recovery test. While the fluorescence signal was slightly distracted by various interferences in river water, the recoveries ranging from 91.29% to 107.74% with RSD values of 4.80% to 7.94% was still good and acceptable (Table 3).

Table 3.

Determination of Cd2+ in environmental water samples (n ≥ 3)

| Background (ng mL−1) |

Spiked (ng mL−1) |

Found (ng mL−1) |

Recovery (%) | RSD (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.02 | 10 | 9.15 | 91.29 | 7.94 |

| 50 | 53.89 | 107.74 | 4.80 | |

| 100 | 97.55 | 97.53 | 5.07 |

The results obtained here with artificial and environmental water samples not only demonstrated robustness in anti-interference of the aptasensor, but also substantiated its promising application in fields.

4. Conclusions

In summary, a facile aptasensor for instantaneous determination of Cd2+ was developed based on the fluorescence amplification effect of MOPS on FAM-aptamer. Under the optimal conditions, Cd2+ could be determined from 5 to 4000 ng mL−1 in a matter of seconds. The detection limit of 1.92 ng mL−1 was significantly lower than the maximum concentration limit for drinking water set by WHO (3 ng mL−1) and EPA (5 ng mL−1). The primary advantages of the aptasensor lay in its ultra-efficiency and simplicity. Since unnecessary preparation of nanoparticles, redundant fabrication procedures, and incubation time were totally omitted, the execution efficiency (both at lab and in field) had been pushed to a new level by current system, demonstrating its great potential for real-time and on-site applicability. Interestingly, MOPS was reported to have fluorescence amplification effect on FAM-aptamer in a given context, advancing our knowledge of MOPS more than a widely used buffer. Although the system possessed the aforementioned merits, there were still some limitations existing. The performance was sensitive to pH, of which should be taken care. Its availability could be further improved if integration into a portable device was realized. Lastly, instead of “signal-off” strategy, a “signal-on” aptasensor would be more favorable, where the signal increased with the increasing concentration of target. Continuous endeavors would be made to push that development.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.L. (Yitong Lu), P.Z.; Data curation: J.D. and X.Z.; Formal analysis: Y.L. (Yang Liu), and D.Z. (Dongwei Zhang); Funding acquisition: P.Z.; Investigation: Y.L. (Yang Liu); Methodology: Y.L. (Yang Liu), D.Z. (Dongwei Zhang), and J.D.; Project administration: X.Y. and D.Z. (Dan Zhang); Resources: X.Z.; Supervision: D.Z. (Dan Zhang), Y.L. (Yitong Lu), and P.Z.; Validation: D.Z. (Dongwei Zhang); Writing—original draft: Y.L. (Yang Liu); Writing—review and editing: Y.L. (Yang Liu), and K.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFD0800807), Shanghai Agriculture Applied Technology Development Program, China (Grant No. T20180413) and Shanghai “Project of Science and Technology Innovation Action” for Agriculture, China (Grant No. 20392001000).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Guo Y., Zhang Y., Shao H., Wang Z., Wang X., Jiang X. Label-free colorimetric detection of cadmium ions in rice samples using gold nanoparticles. Anal. Chem. 2014;86:8530–8534. doi: 10.1021/ac502461r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Movaghgharnezhad S., Mirabi A., Toosi M.R., Rad A.S. Synthesis of cellulose nanofibers functionalized by dithiooxamide for preconcentration and determination of trace amounts of Cd(II) ions in water samples. Cellulose. 2020;27:8885–8898. doi: 10.1007/s10570-020-03388-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Priya T., Dhanalakshmi N., Thennarasu S., Thinakaran N. Ultra sensitive detection of Cd (II) using reduced graphene oxide/carboxymethyl cellulose/glutathione modified electrode. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018;197:366–374. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ashrafzadeh Afshar E., Taher M.A., Fazelirad H. Ultra-trace determination of thallium(I) using a nanocomposite consisting of magnetite, halloysite nanotubes and dibenzo−18-crown−6 for preconcentration prior to its quantitation by ET-AAS. Microchim. Acta. 2017;184:791–797. doi: 10.1007/s00604-016-2040-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Junior M.M., Silva L.O., Leao D.J., Ferreira S.L. Analytical strategies for determination of cadmium in Brazilian vinegar samples using ET AAS. Food Chem. 2014;160:209–213. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.03.090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Alvarez M.A., Carrillo G. Simultaneous determination of arsenic, cadmium, copper, chromium, nickel, lead and thallium in total digested sediment samples and available fractions by electrothermal atomization atomic absorption spectroscopy (ET AAS) Talanta. 2012;97:505–512. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang M., Ma H., Chi Q., Li Q., Li M., Zhang H., Li C., Fang H. A monolithic copolymer prepared from N-(4-vinyl)-benzyl iminodiacetic acid, divinylbenzene and N,N’-methylene bisacrylamide for preconcentration of cadmium(II) and cobalt(II) from biological samples prior to their determination by ICP-MS. Microchim. Acta. 2019;186:537. doi: 10.1007/s00604-019-3656-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li Y., Guo W., Hu Z., Jin L., Hu S., Guo Q. Method Development for Direct Multielement Quantification by LA-ICP-MS in Food Samples. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2019;67:935–942. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b05479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang N., Shen K., Yang X., Li Z., Zhou T., Zhang Y., Sheng Q., Zheng J. Simultaneous determination of arsenic, cadmium and lead in plant foods by ICP-MS combined with automated focused infrared ashing and cold trap. Food Chem. 2018;264:462–470. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.05.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nunes M.A., Voss M., Corazza G., Flores E.M., Dressler V.L. External calibration strategy for trace element quantification in botanical samples by LA-ICP-MS using filter paper. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2016;905:51–57. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2015.11.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paixao L.B., Brandao G.C., Araujo R.G.O., Korn M.G.A. Assessment of cadmium and lead in commercial coconut water and industrialized coconut milk employing HR-CS GF AAS. Food Chem. 2019;284:259–263. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.12.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dos Santos J.M., Quinaia S.P., Felsner M.L. Fast and direct analysis of Cr, Cd and Pb in brown sugar by GF AAS. Food Chem. 2018;260:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.03.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuerk C., Gold L. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science. 1990;249:505–510. doi: 10.1126/science.2200121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellington A.D., Szostak J.W. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature. 1990;346:818–822. doi: 10.1038/346818a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yuce M., Ullah N., Budak H. Trends in aptamer selection methods and applications. Analyst. 2015;140:5379–5399. doi: 10.1039/C5AN00954E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu C., Li L., Wang Z., Irfan M., Qu F. Recent advances of aptasensors for exosomes detection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020;160:112213. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2020.112213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeng L., Gong J., Rong P., Liu C., Chen J. A portable and quantitative biosensor for cadmium detection using glucometer as the point-of-use device. Talanta. 2019;198:412–416. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2019.02.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu Y.F., Wang Y.S., Zhou B., Yu J.H., Peng L.L., Huang Y.Q., Li X.J., Chen S.H., Tang X., Wang X.F. A multifunctional fluorescent aptamer probe for highly sensitive and selective detection of cadmium(II) Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017;409:4951–4958. doi: 10.1007/s00216-017-0436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lotfi Zadeh Zhad H.R., Rodríguez Torres Y.M., Lai R.Y. A reagentless and reusable electrochemical aptamer-based sensor for rapid detection of Cd(II) J. Electroanal. Chem. 2017;803:89–94. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2017.09.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang H., Cheng H., Wang J., Xu L., Chen H., Pei R. Selection and characterization of DNA aptamers for the development of light-up biosensor to detect Cd(II) Talanta. 2016;154:498–503. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2016.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu Y., Zhan S., Wang L., Zhou P. Selection of a DNA aptamer for cadmium detection based on cationic polymer mediated aggregation of gold nanoparticles. Analyst. 2014;139:1550–1561. doi: 10.1039/C3AN02117C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Solra M., Bala R., Wangoo N., Soni G.K., Kumar M., Sharma R.K. Optical pico-biosensing of lead using plasmonic gold nanoparticles and a cationic peptide-based aptasensor. Chem. Commun. 2019;56:289–292. doi: 10.1039/C9CC07407D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao Q., Feng J., Li J., Feng M., Huang S. A label-free and ultrasensitive electrochemical aptasensor for lead(II) using a N,P dual-doped carbon dot-chitosan composite as a signal-enhancing platform and thionine as a signaling molecule. Analyst. 2018;143:4764–4773. doi: 10.1039/C8AN00994E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ding J., Liu Y., Zhang D., Yu M., Zhan X., Zhang D., Zhou P. An electrochemical aptasensor based on gold@polypyrrole composites for detection of lead ions. Microchim. Acta. 2018;185:545. doi: 10.1007/s00604-018-3068-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen Y., Li H.H., Gao T., Zhang T.T., Xu L.J., Wang B., Wang J.N., Pei R.J. Selection of DNA aptamers for the development of light-up biosensor to detect Pb(II) Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2018;254:214–221. doi: 10.1016/j.snb.2017.07.068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yuan M., Song Z.H., Fei J.Y., Wang X.L., Xu F., Cao H., Yu J.S. Aptasensor for lead(II) based on the use of a quartz crystal microbalance modified with gold nanoparticles. Microchim. Acta. 2017;184:1397–1403. doi: 10.1007/s00604-017-2135-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sharifi A., Hallaj R., Bahar S., Babamiri B. Indirect determination of mercury(II) by using magnetic nanoparticles, CdS quantum dots and mercury(II)-binding aptamers, and quantitation of released CdS by graphite furnace AAS. Microchim. Acta. 2020;187:91. doi: 10.1007/s00604-019-4029-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ning Y., Hu J., Wei K., He G., Wu T., Lu F. Fluorometric determination of mercury(II) via a graphene oxide-based assay using exonuclease III-assisted signal amplification and thymidine-Hg(II)-thymidine interaction. Microchim. Acta. 2019;186:216. doi: 10.1007/s00604-019-3332-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Berlina A.N., Zherdev A.V., Dzantiev B.B. Progress in rapid optical assays for heavy metal ions based on the use of nanoparticles and receptor molecules. Microchim. Acta. 2019;186:172. doi: 10.1007/s00604-018-3168-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang H., Zhang Y., Ma H., Ren X., Wang Y., Zhang Y., Wei Q. Electrochemical DNA probe for Hg2+ detection based on a triple-helix DNA and Multistage Signal Amplification Strategy. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016;86:907–912. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2016.07.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cui L., Wu J., Ju H. Label-free signal-on aptasensor for sensitive electrochemical detection of arsenite. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2016;79:861–865. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu Y., Liu L., Zhan S., Wang F., Zhou P. Ultrasensitive aptamer biosensor for arsenic(III) detection in aqueous solution based on surfactant-induced aggregation of gold nanoparticles. Analyst. 2012;137:4171–4178. doi: 10.1039/c2an35711a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu Y.F., Wang Y.S., Zhou B., Huang Y.Q., Li X.J., Chen S.H., Wang X.F., Tang X. Ultrasensitive detection of Ag(I) based on the conformational switching of a multifunctional aptamer probe induced by silver(I) Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2018;189:190–194. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2017.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou W., Ding J., Liu J. 2-Aminopurine-modified DNA homopolymers for robust and sensitive detection of mercury and silver. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2017;87:171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2016.08.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Banerjee S., Kumar N.P., Srinivas A., Roy S. Core-shell Fe3O4@Au nanocomposite as dual-functional optical probe and potential removal system for arsenic (III) from Water. J. Hazard Mater. 2019;375:216–223. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.04.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Song J., Huang M., Jiang N., Zheng S., Mu T., Meng L., Liu Y., Liu J., Chen G. Ultrasensitive detection of amoxicillin by TiO2-g-C3N4@AuNPs impedimetric aptasensor: Fabrication, optimization, and mechanism. J. Hazard Mater. 2020;391:122024. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.122024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu Y., Zhang D., Ding J., Hayat K., Yang X., Zhan X., Zhang D., Lu Y., Zhou P. Label-Free and Sensitive Determination of Cadmium Ions Using a Ti-Modified Co3O4-Based Electrochemical Aptasensor. Biosensors. 2020;10:195. doi: 10.3390/bios10120195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang S., Zhang G., Chen Q., Zhou J., Wu Z. Sensing of cocaine using polarized optical microscopy by exploiting the conformational changes of an aptamer at the water/liquid crystal interface. Microchim. Acta. 2019;186:724. doi: 10.1007/s00604-019-3855-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiao F., Tan H., Wu Y., Liao S., Wu Z., Shen G., Yu R. A novel logic gate based on liquid-crystals responding to the DNA conformational transition. Analyst. 2016;141:2870–2873. doi: 10.1039/C6AN00504G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chang Y., Liu M., Liu J. Highly Selective Fluorescent Sensing of Phosphite through Recovery of Poisoned Nickel Oxide Nanozyme. Anal. Chem. 2020;92:3118–3124. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang X., Servos M.R., Liu J. Instantaneous and quantitative functionalization of gold nanoparticles with thiolated DNA using a pH-assisted and surfactant-free route. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:7266–7269. doi: 10.1021/ja3014055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang X., Fan X., Wang Y., Lei F., Li L., Liu J., Wu P. Highly Stable Colorimetric Sensing by Assembly of Gold Nanoparticles with SYBR Green I: From Charge Screening to Charge Neutralization. Anal. Chem. 2020;92:1455–1462. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b04660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y., Zhang Z., Yin D., Li J., Xie R., Yang W. Turn-on fluorescent InP nanoprobe for detection of cadmium ions with high selectivity and sensitivity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2013;5:9709–9713. doi: 10.1021/am402768w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu L., Liang J., Wang Y., Ren S., Wu J., Zhou H., Gao Z. Highly Selective, Aptamer-Based, Ultrasensitive Nanogold Colorimetric Smartphone Readout for Detection of Cd(II) Molecules. 2019;24:2745. doi: 10.3390/molecules24152745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhou B., Chen Y.T., Yang X.Y., Wang Y.S., Hu X.J., Suo Q.L. An Ultrasensitive Colorimetric Strategy for Detection of Cadmium Based on the Peroxidase-like Activity of G-Quadruplex-Cd(II) Specific Aptamer. Anal. Sci. 2019;35:277–282. doi: 10.2116/analsci.18P248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhou D.H., Wu W., Li Q., Pan J.F., Chen J.H. A label-free and enzyme-free aptasensor for visual Cd2+ detection based on split DNAzyme fragments. Anal. Methods. 2019;11:3546–3551. doi: 10.1039/C9AY00822E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang J., Wang J., Zhou P., Tao H., Wang X., Wu Y. Oligonucleotide-induced regulation of the oxidase-mimicking activity of octahedral Mn3O4 nanoparticles for colorimetric detection of heavy metals. Microchim. Acta. 2020;187:99. doi: 10.1007/s00604-019-4069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y., Ran G., Lu G., Ni X., Liu D., Sun J., Xie C., Yao D., Bai W. Highly Sensitive Label-Free Electrochemical Aptasensor Based on Screen-Printed Electrode for Detection of Cadmium(II) Ions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2019;166:B449–B455. doi: 10.1149/2.0991906jes. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Luan Y.X., Lu A.X., Chen J.Y., Fu H.L., Xu L. A Label-Free Aptamer-Based Fluorescent Assay for Cadmium Detection. Appl. Sci. Basel. 2016;6:432. doi: 10.3390/app6120432. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhou B., Yang X.Y., Wang Y.S., Yi J.C., Zeng Z., Zhang H., Chen Y.T., Hu X.J., Suo Q.L. Label-free fluorescent aptasensor of Cd2+ detection based on the conformational switching of aptamer probe and SYBR green I. Microchem. J. 2019;144:377–382. doi: 10.1016/j.microc.2018.09.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang W., Jin Y., Zhao Y., Yue X., Zhang C. Single-labeled hairpin probe for highly specific and sensitive detection of lead(II) based on the fluorescence quenching of deoxyguanosine and G-quartet. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2013;41:137–142. doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2012.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li W., Zhang Z., Zhou W., Liu J. Kinetic Discrimination of Metal Ions Using DNA for Highly Sensitive and Selective Cr3+ Detection. ACS Sens. 2017;2:663–669. doi: 10.1021/acssensors.7b00115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.