Abstract

Influenza epidemics remain a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In the current study, we investigated the impact of chronological aging on tryptophan metabolism in response to influenza infection. Examination of metabolites present in plasma collected from critically ill patients, identified tryptophan metabolism as an important metabolic pathway utilized specifically in response to influenza. Using a murine model of influenza infection to further these findings illustrated that there was decreased production of kynurenine in aged lung in an indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1)-dependent manner that was associated with increased inflammatory and diminished regulatory responses. Specifically, within the first seven days of influenza, there was a decrease in kynurenine pathway mediated metabolism of tryptophan, which resulted in a subsequent increase in ketone body catabolism in aged alveolar macrophages. Treatment of aged mice with mitoquinol, a mitochondrial targeted antioxidant, improved mitochondrial function and restored tryptophan metabolism. Taken together, our data provide additional evidence as to why older persons are more susceptible to influenza and suggest a possible therapeutic to improve immunometabolic responses in this population.

Keywords: Influenza, Aging, Lung, Macrophage, Immunometabolism, Mitochondria, Kynurenine, Tryptophan Metabolism

Introduction

Influenza epidemics still remain a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, with highest incidence of hospitalization and death occurring in persons >65 years of age [1]. The kynurenine pathway (KP) of tryptophan metabolism is a highly regulated pathway utilized by the immune system to promote immunosuppression in response to excessive inflammation [2–9]. Kynurenine catabolites, such as quinolinate, are essential for the production of nicotinamide and NAD+ as well as initiate involvement of type 2 T helper cell mediated resolution [7]. In response to heightened levels of cellular stress or energy usage, KP mediated oxidation of tryptophan can renew NAD+ levels [10]. Tryptophan metabolism by the KP is initiated by indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1). IDO1 expression is tightly regulated by the immune system; specifically IDO1 is activated by pro-inflammatory cytokines and inhibited by regulatory, anti-inflammatory cytokines [2, 3, 11–15].

Despite the important role for KP mediated tryptophan metabolism in the initiation and regulation of immune response to influenza, little is known regarding the impact of aging and aging associated changes in mitochondrial stress on this metabolic pathway. In the current study, using plasma collected from critically ill patients, we show that tryptophan metabolism is an important metabolic pathway utilized specifically in response to influenza. Using a murine model of influenza infection to further these findings, our results illustrate decreased production of kynurenine in aged lung that was associated with increased inflammatory and diminished regulatory responses. Reduced IDO1 expression and activity in aged lung and alveolar macrophages corresponded with changes in metabolic gene regulation and the initiation of alternative tryptophan metabolism pathways. Our findings demonstrated that decreased IDO expression was associated with dysregulated mitochondrial gene expression and heightened generation of reactive oxygen species. Treatment of aged mice with mitoquinol, a mitochondrial targeted antioxidant, improved mitochondrial function and restored KP mediated metabolism of tryptophan in alveolar macrophages and resulted in decreased inflammatory cytokine production and cellular recruitment to the aged lung.

Methods

Detailed methods are provided in the Supplementary Material.

Study approval and subjects

This study is an analysis of prospectively collected data from 39 subjects recruited from an ICU cohort from New York Presbyterian Hospital-Weill Cornell Medical Center (NYP-WCMC, IRB:1405015116). Protocols for recruitment, data collection, and sample processing have been described previously [16–20].

Mouse model of influenza

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the animal guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Weill Cornell Medicine (IACUC: 2016–0059). Young (2 months) and aged (18 months) male and female BALB/c mice were purchased from the National Institute on Aging rodent facility (Charles River Laboratories). Influenza viral stock (material #: 10100374, batch #: 4XP170531, EID50 per ml: 1010.3) was purchased from Charles River (Norwich, CT). Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane prior to intranasal instillation with 12.5 PFU of influenza (50μL volume in PBS). Mice received a 100μL volume of PBS or 10–50μg dose of mitoquinol (Cayman Chemical) intraperitoneally starting at day 3 post influenza. Starting at day 0, mice received a daily intraperitoneal injection containing PBS or BMS-986205 (200μM) (Selleck Chemicals).

Statistics

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA). All samples were independent and contained the same sample size for analysis. P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Increased Tryptophan Metabolism in Response to Influenza Infection.

Using a principal component analysis to provide a high-level overview of the dataset, illustrated limited clustering of metabolites in plasma collected from control, influenza A/B positive patients, and patients with other viral infections (OVI) (Figure 1A, patient demographics and PCR confirmed microbiology results Table 1). Focusing on specific biochemical and pathway changes illustrated a distinct metabolic increase in several metabolic pathways, including tryptophan metabolism, that occurred in patients during the course of influenza infection (Figure 1A–B). When compared to influenza A/B samples, there was significantly elevated levels of tryptophan and serotonin present in the plasma of patients with OVI (Figure 1C–D). In contrast, there was a significant increase in kynurenine and kynurenate present in plasma from the influenza A/B groups when compared to control, with significantly higher levels of kynurenate in influenza A/B positive patients (Figure 1E–F). To provide more insight, we evaluated kynurenine levels in plasma samples based on influenza severity (i.e. mild versus severe influenza). Severe influenza was defined as a positive influenza test result combined with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) requiring intubation. While patients with mild symptoms during influenza exhibited an age-associated trend in kynurenine expression, patients that exhibited severe influenza with ARDS had decreasing kynurenine and increasing tryptophan as they age (Supplemental Figure 1A). While these metabolites were also elevated in the OVI, the levels did not reach statistical significance, suggesting that influenza A/B infections cause the strongest inflammatory response. The further breakdown products quinolinate and xanthurenate were also examined, with significantly increased levels of quinolinate present in influenza A/B positive patients (Figure 1G–H).

Figure 1: Increased Tryptophan Metabolism during Influenza.

(A) Principal component analysis grouping of metabolites (colour scheme illustrated in Figure 1 panel). (B) Overview of tryptophan metabolism pathways. (C-H) Scaled intensity of tryptophan metabolites present in control, influenza A:B (Inf A:B), and other viral infection (OVI) patients. (*) P<0.05, (**) P<0.01, (***) P<0.001. Complete methods and statistical analysis included in Supplemental Methods.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

| Variable | Control | Influenza pneumonia | Non-influenza viral pneumonia | p-value |

| n | 15 | 11 | 13 | |

| Age, mean | 63.5 ± 16.3 | 65.1 ± 24.1 | 50.6 ± 21.9 | 0.165 |

| Male (%) | 9 (60.0) | 8 (72.7) | 7 (53.8) | 0.651 |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||

| White | 10 (66.7) | 6 (54.5) | 3 (23.1) | 0.026* |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | |

| Black | 1 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.7) | |

| Hispanic | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (38.5) | |

| Other | 4 (26.7) | 4 (36.4) | 4 (30.8) | |

| BMI, mean (kg/m2) | 31.9 ± 8.8 | 27.2 ± 7.3 | 32.7 ± 10.8 | 0.590 |

| Medical history (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 4 (26.7) | 2 (18.2) | 2 (15.4) | 0.884 |

| COPD | 2 (13.3) | 1 (9.1) | 0 (0) | 0.488 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3 (20.0) | 2 (18.2) | 0 (0) | 0.237 |

| Liver disease | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (7.7) | 0.615 |

| Malignancy | 5 (33.3) | 3 (27.3) | 4 (30.8) | 1.000 |

| Immunosuppression | 2 (13.3) | 4 (36.4) | 2 (15.4) | 0.370 |

| Smoking history | 7 (46.7) | 4 (36.4) | 1 (7.7) | 0.068 |

| Diagnosis (%) | ||||

| Heart failure | 2 (13.3) | 3 (27.3) | 0 (0) | 0.162 |

| Acute respiratory failure | 8 (53.3) | 6 (54.5) | 9 (69.2) | 0.710 |

| SOFA total, mean | 5.7 ± 3.3 | 5.9 ± 4.0 | 5.9 ± 3.4 | 0.992 |

| ICU mortality (%) | 2 (13.3) | 3 (27.3) | 2 (15.4) | 0.646 |

| Intubation (%) | 9 (60.0) | 3 (27.3) | 6 (46.2) | 0.241 |

| Microorganism | ||||

| Control | Influenza | Viral pneumonia | ||

| Influenza A virus | - | 9 (81.8) | - | |

| Influenza B virus | - | 2 (18.2) | - | |

| Rhinovirus / Enterovirus | - | - | 7 (53.8) | |

| Respiratory Syncytial virus | - | - | 2 (15.4) | |

| Adenovirus | - | - | 1 (7.7) | |

| Cytomegalovirus | - | - | 1 (7.7) | |

| Metapneumovirus | - | - | 1 (7.7) | |

| Others | - | - | 1 (7.7) | |

Tryptophan Metabolism is Altered in Aged Lung during Influenza Infection.

In response to influenza, there was cellular infiltration in both young adult (2 months of age) and aged adult (18–20 months of age) murine lung, with marked levels of immune cells infiltrating into the aged lung (Figure 2A). As the course of influenza infection progressed, there was increased inflammation present in the aged lung that corresponded with increased viral titers, morbidity, and mortality (Figure 2A–B, Supplemental Figure 1B–C). Examination of the total bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cell count illustrated significantly increased cellular infiltration in aged lung (Figure 2C). Lung permeability was assessed by intranasal instillation of FITC-dextran. As shown in Figure 2D, there was a significant increase in lung permeability, as illustrated by elevated FITC fluorescence in plasma, in aged lung at baseline as well as in response to influenza. Similarly, there was a significant increase in BAL protein that corresponded with elevated water accumulation in the aged lung during infection (Figure 2E–F). Given the importance of NAD levels in mediating tissue injury, we examined changes in NAD+ expression in young and aged lung tissue. Our results illustrated an age-dependent decrease in NAD+ in lung tissue at baseline and during the course of infection (Figure 2G). When compared to young, there was increased expression of IL6 and IL1β by day 5, with significantly enhanced production by day 7 (Figure 2H–I). Initial expression of resolution cytokines, such as IL10, was detectable in the BAL collected on day 7 post infection, with a significantly higher-level present in BAL isolated from young lung (Figure 2J). We next examined if heightened IL10 expression correlated with increased infiltration of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. When compared to young, despite increased baseline CD4+CD25+ T cell numbers in aged lung, there were significantly decreased number of cells present in aged lung in response to influenza (Figure 2K).

Figure 2: Increased Inflammation and Cellular Infiltration in Aged Murine Lung during Influenza Infection.

Young adult (2 months of age) and aged adult (18 months of age) mice were infected with 12.5 PFU of influenza (A/Puerto Rico/8/1934, H1N1) (PR8). Lung tissue was collected at baseline and at days 3, 5, and 7 post infection. (A) Lung tissue histology post H&E staining was examined during the course of infection. (B) Viral titers and (C) total cell number was assessed in BAL. (D) Mice were instilled with 3 mg/ml of FITC-dextran and relative FITC fluorescence in plasma was assessed during the course of influenza. (E) Protein concentration was assessed in young and aged BAL. Lung tissue was collected at select time points of infection and (F) wet to dry ratio of lung tissue and (G) NAD+ levels were evaluated. Production of IL6 (H), IL1β (I), and IL10 (J) were assessed in BAL collected during influenza. (K) BAL was isolated and CD4+CD25+ T cells were enriched from BAL collected on day 7 post influenza and cell numbers were quantified. Student’s t-test: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, and ****P<0.0001. Similar results were obtained from at least three independent experiments, with N=10 per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

We observed that metabolic profiles of young and aged lung samples cluster separately at baseline as well as during influenza (Figure 3A). Focusing on the biochemical and pathway changes in the profiles, illustrated an important role for kynurenine and tryptophan metabolism in modulating immune responses in the lung in response to influenza (Figure 3B). Specifically, kynurenine was increasingly elevated over time in lung isolated from both young and aged adult mice, with significantly higher levels being detected in the young lung at day 7 post infection (Figure 3C). While levels of kynurenate were similar in young and aged lung, the kynurenine catabolite, quinolinate, was augmented in young lung at later time points of influenza infection (Figure 3D–E). There was an increase in the presence of tryptophan in the aged lung, with significantly higher levels present at day 7 of influenza infection (Figure 3F). Increased expression of downstream tryptophan metabolites, indoleacetate and indolepropionate, were also detected in aged lung at later time points of infection (Figure 3G–H).

Figure 3: Tryptophan Metabolism is Altered in Aged Lung during Influenza Infection.

Young adult (2 months of age) and aged adult (18 months of age) mice were infected with 12.5 PFU of influenza (A/Puerto Rico/8/1934, H1N1) (PR8). Lung tissue was collected at baseline and at days 3, 5, and 7 post infection. (A) Principal component analysis of metabolites present in young and aged adult lung during influenza infection. Young adult samples (circles, grey hue) and aged adult (squares, grey hue). (B) Tryptophan metabolic pathway and downstream metabolites. Comparison of kynurenine (C), kynurenate (D), quinolinate (E), tryptophan (F), indoleacetate (G), and indolepropionate (H) present in young and aged lung. Student’s t-test: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, and ****P<0.0001. Similar results were obtained from at least three independent experiments, with N=10 per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

We next examined if changes in IDO1 expression and activity in aged lung might underlie changes in tryptophan metabolism in response to influenza. In response to influenza, there was significantly reduced IDO1 specific activity at days 5 and 7 post infection in both lung and BAL collected from aged adult mice (Figure 4A–B). Levels of kynurenine in lung and BAL illustrated a similar phenotype in aged mice, with significantly higher levels at baseline that decline during the course of influenza infection (Figure 4C–D). A corresponding increase in tryptophan was also present in aged lung and BAL, with significantly increased expression at days 5 and 7 post infection (Figure 4E–F).

Figure 4: IDO1 expression and activity is altered in aged lung during influenza infection.

Young adult (2 months of age) and aged adult (18 months of age) mice were infected with 12.5 PFU of influenza (A/Puerto Rico/8/1934, H1N1) (PR8). Lung tissue or BAL was collected at baseline and at days 3, 5, and 7 post infection. Specific activity of IDO1 was quantified in lung homogenates (A) and BAL (B) in response to influenza. Changes in kynurenine (C-D) and tryptophan (E-F) production were examined in lung homogenates and BAL collected from control and influenza infected mice by ELISA. Student’s t-test: *P<0.05, **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, and ****P<0.0001. Similar results were obtained from at least three independent experiments, with N=10 per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

IDO1 inhibition in young macrophages and lung contribute to increased IL6 expression and inflammation during infection.

To elucidate the importance of IDO1 for influenza mediated production of inflammatory cytokines, such as IL6, we examined the impact of several IDO1 inhibitors on modulating IL6 production by young BMDM in response to LPS or poly I:C stimulation. In response to stimulation with LPS (24 hours) there was a significant increase in IL6 production by young BMDM treated with IDO1 inhibitors BMS-986205, 1-methyl-DL-tryptophan, NLG919, and IDO-1 inhibitor (Supplemental Figure 2A). In response to poly I:C stimulation (24 hours), there was a significant increase in IL6 production by young BMDM treated with IDO1 inhibitors BMS-986205, NLG919, and IDO-1 inhibitor (Supplemental Figure 2B). Based on these results, we chose to further examine the impact of IDO1 inhibition using the irreversible inhibitor, BMS-986205. Treatment of young BMDM with BMS-986205 resulted in a significant decrease in IDO1 protein expression and activity, which corresponded with increased IL6 production (Supplemental Figure 2C–E). Daily in vivo treatment of young adult mice with BMS-986205 resulted in increased cellular infiltration and marked changes in the lung that corresponded with significant weight loss and increased viral titers (Figure 5A–D). In response to BMS-986205, there was a significant increase in cells present in the BAL that corresponded with decreased IDO1 activity in lung and alveolar macrophage populations and significantly augmented levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL6, and decreased production of pro-resolution cytokines, such as IL10 (Figure 5E–I).

Figure 5: IDO1 inhibition in young macrophages and lung contribute to increased IL6 expression and inflammation during influenza infection.

(A) Young adult (2 months of age) mice were infected with 12.5 PFU of influenza (A/Puerto Rico/8/1934, H1N1) (PR8). Starting at day 0, mice received a daily intraperitoneal injection containing PBS or BMS-986205 (200μM). Lung tissue or BAL was collected at baseline and at days 3 and 5 post infection. (B) Lung tissue histology post H&E staining was examined during the course of infection. (C) Change in weight was assessed during the first 5 days of infection. (D) Viral titers were assessed in BAL at day 5 post infection. (E) Total cell numbers were assessed in BAL. IDO1 specific activity was assessed in (F) lung homogenates and (G) alveolar macrophages in response to treatment with BMS-986205. Production of IL6 (H) and IL10 (I) were assessed in BAL collected during influenza. Student’s t-test: **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, and ****P<0.0001. Similar results were obtained from at least three independent experiments, with N=10 per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

Age-associated mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to changes in IDO1 expression and KP mediated metabolism of tryptophan.

As shown in Figure 6A, when compared to young, there was reduced Ido1 mRNA expression in aged lung at baseline and during the course of influenza infection. Interestingly, there was augmented expression of other metabolic pathways, such as betaine-homocysteine methyltransferase (Bhmt), which catalyzes the conversion of homocysteine to methionine, and succinyl-CoA:3-ketoacid coenzyme A transferase 2A (Oxct2a), a key enzyme for ketone body catabolism, in aged lung by day 7 post influenza (Figure 6A, Supplemental Table 1). When compared to young, there was also diminished Ido1 mRNA expression in aged alveolar macrophages during the course of influenza infection (Figure 6B, Supplemental Table 1). Decreased kynurenine 3-monooxygenase (Kmo) and nitric oxide synthase 2 (Nos2) mRNA expression, which was associated with augmented Oxct2a mRNA expression, was observed in aged alveolar macrophages by day 7 of influenza infection (Figure 6B, Supplemental Table 1). As mitochondria play an intricate role in modulating metabolic processes, we next examined how different components of the mitochondria might respond to energy demands of the host during influenza infection. During influenza infection, there were distinct changes in gene regulation in both young and aged lung, with decreased gene expression in aged lung by day 7 of infection (Figure 6C and Supplemental Table 2). Recent work has illustrated that kynurenine can bind to aryl hydrocarbon receptor and result in heightened kynurenine activity [21]. Interestingly, in aged lung by day 7 of influenza, there was upregulated expression of AhR interacting protein (Aip), a protein shown to stabilize and enhance AhR function, which corresponded with declining levels of kynurenine [22] (Figure 6C, Supplemental Table 2).

Figure 6: Age-associated mitochondrial dysfunction contributes to changes in IDO1 expression and KP mediated metabolism of tryptophan.

Young adult (2 months of age) and aged adult (18 months of age) mice were infected with 12.5 PFU of influenza (A/Puerto Rico/8/1934, H1N1). Lung tissue or BAL cells were collected at baseline and during infection from young, aged, and aged treated with mitoquinol (50μM) starting at day 3 post infection. (A, D) Gene expression of Ahcy, Bhmt, Ido1, Oxct2a, Srm, and Tph2 were assessed in lung on days 3, 5, and 7 post infection and were relative to uninfected control and normalized to β-actin (please see data is presented in Table 2). (B, E) Gene expression of Cdo1, Ido1, Kmo, Nos2, and Oxct2a were examined in BAL cells collected on days 3, 5, and 7 post infection and were relative to uninfected control and normalized to β-actin (please see data is presented in Table 2). (C) Mitochondrial gene expression was assessed by real time PCR using lung tissue collected on days 3, 5, and 7 post infection and were relative to uninfected control and normalized to β-actin (please see data is presented in Supplemental Table 2). Similar results were obtained from at least three independent experiments.

Given these findings, we evaluated the impact of mitochondrial targeted antioxidants, mitoTEMPO-L (MTL), Trolox, and mitoquinol, on IL6 production by LPS stimulated BMDM. There was a significant reduction of IL6 at both 4 and 24 hours in aged, mitoquinol treated BMDM (Supplemental Figure 3A). Further, in response to treatment of aged BMDM with mitoquinol, there was a significant increase in IDO1 expression, increased ratio of kynurenine to tryptophan post stimulation with LPS and poly I:C, and a corresponding decrease in IL6 production (Supplemental Figure 3B–D). Based on these findings, we treated aged mice with daily injections of mitoquinol (50μM/mouse/day) starting at a time point when clinical manifestations of influenza were detectable in aged mice (day 3 post infection) (Supplemental Figure 4A). In response to mitoquinol, there was a marked decrease in weight loss and decreased viral titers (Supplemental Figure 4B–C). Further, mitoquinol treatment dramatically impacted mitochondrial gene expression in aged lung on day 7 post influenza (Figure 6C, Supplemental Table 2). Specifically, mitoquinol treatment resulted in decreased expression of Aip (Figure 6C, Supplemental Table 2). Superoxide formation in alveolar macrophages isolated from lung at select time points during influenza was also decreased in response to mitoquinol treatment (Supplemental Figure 4D). In response to daily treatment with mitoquinol there was a significant decrease in Bhmt and Oxct2a mRNA that was associated with increased IDO1 mRNA expression in aged lung by day 7 post influenza (Figure 6D, Supplemental Table 2). Examination of metabolic gene expression in aged alveolar macrophages at days 5 and 7 post influenza infection, illustrated a decrease in Oxct2a mRNA and a corresponding increase in Ido1 and Kmo mRNA expression (Figure 6E, Supplemental Table 2).

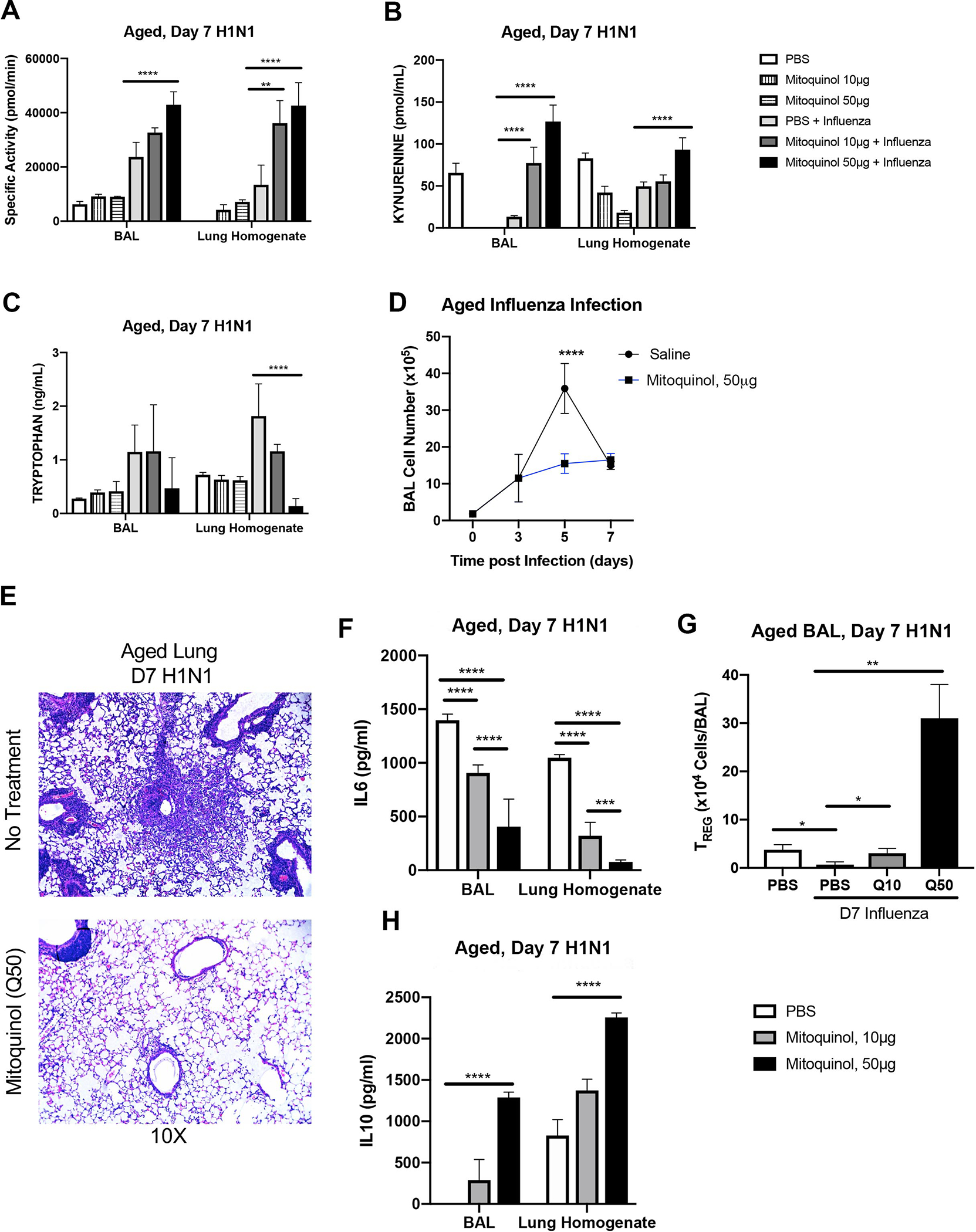

In response to different doses of mitoquinol, we detected increased IDO1 specific activity, which corresponded with significantly heightened kynurenine and reduced tryptophan production (Figure 7A–C). Daily treatment with mitoquinol decreased cellular infiltration and inflammation in the aged lung (Figure 7D–E). Further, at day 7 post influenza, there was a significant reduction of IL6 expression in BAL and lung homogenates collected from mitoquinol treated mice (Figure 7F). Further, in response to daily treatment with mitoquinol, there was a dose dependent increase in the number of CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells, which corresponded with increasing levels of IL10 production in aged lung by day 7 post influenza (Figure 7G–H).

Figure 7: Treatment with mitoquinol, a mitochondrial targeted antioxidant, improves mitochondrial dysfunction and kynurenine pathway mediated tryptophan metabolism during influenza infection.

Young adult (2 months of age) and aged adult (18 months of age) mice were infected with 12.5 PFU of influenza (A/Puerto Rico/8/1934, H1N1). Lung tissue, BAL, and BAL cells were collected at baseline and during infection from young, aged, and aged treated with mitoquinol (10 or 50μM) starting at day 3 post infection. IDO1 specific activity (A), kynurenine (B), and tryptophan (C) were assessed in aged adult mice in response to mitoquinol treatment during influenza infection. (D) Total cell number was assessed in BAL. (E) Lung tissue histology post H&E staining was examined during the course of infection. (F) IL6 production was assessed by ELISA. (G) BAL was isolated and CD4+CD25+ T cells were enriched from BAL collected from PBS and mitoquinol treated lung on day 7 post influenza and cell numbers were quantified. (H) IL10 production was assessed by ELISA. Student’s t-test: **P<0.01, ***P<0.001, and ****P<0.0001. Similar results were obtained from at least three independent experiments with N=10 per group. Data are expressed as the mean ± SD.

Discussion

In the current study, we investigated the impact of chronological aging on tryptophan metabolism in response to influenza infection. Examination of metabolites present in human plasma, identified tryptophan metabolism as an important metabolic pathway utilized in response to influenza. Our results expand upon these findings and illustrate decreased production of kynurenine in aged lung in response to influenza was associated with increased inflammatory and diminished regulatory responses. Reduced IDO1 activity in aged lung and alveolar macrophages corresponded with changes in metabolic gene regulation and the initiation of alternative tryptophan metabolism pathways. Our findings also demonstrated that decreased IDO1 expression was due to dysregulated mitochondrial gene expression and heightened generation of ROS, as treatment with mitoquinol improved mitochondrial function and restored KP mediated tryptophan metabolism. Taken together, our data provide additional evidence as to why older persons are more susceptible to influenza.

Using a murine model of infection, there was an increase in kynurenine in both young and aged lung starting at day 3 and continued to increase by day 5. These findings are in agreement with previous influenza studies investigating the metabolic responses in young adult mice [23]. However, by day 7, kynurenine levels were only heightened in young lung, with levels remaining unchanged in the aged lung. While kynurenine was produced by an inflammatory process, it has an anti-inflammatory function, often serving as a brake on the immune response. Downstream metabolites, such as quinolinate, play an important role in replenishing NAD+ levels to meet host energy demands in response to heightened cellular stress during influenza infection. Decreased KP mediated tryptophan metabolism and production of quinolinate in aged lung corresponded with impaired NAD+ replenishment and an inability to meet host energy demands. As tryptophan metabolism is a negative feedback metabolism, an inefficacy of aged alveolar macrophages to utilize this metabolic pathway would result in decreased NAD+ replenishment and increased inflammation. Interestingly, kynurenine levels appeared to be higher in the older animals at baseline but increased more dramatically in the young animals following infection. Previous work has illustrated that chronic low-grade inflammation can result in elevated levels of circulating kynurenine [24]. Therefore, it may be possible that the increased presence of inflammatory cytokines in aged hosts may have a significant impact on baseline kynurenine levels and resulting in changes in tryptophan metabolism in response to pathogenic stimuli.

During the course of influenza infection, there was a metabolic shift in aged lung and alveolar macrophages. When compared to young, there was an increase in succinyl-coA: 3-ketoacid coenzyme A transferase 2A (Oxct2a), a key enzyme for ketone body catabolism, which corresponded with diminished mitochondrial gene expression. Our results illustrate that treatment with a mitochondrial targeted antioxidant improved mitochondrial gene regulation and diminished Oxct2a expression in aged lung and alveolar macrophages. Based on these findings, during the course of influenza, when there is decreased glycolytic ATP production, to meet host energy demands, there may be a change in metabolic gene expression, which may reflect increased ketone body catabolism. In the context of heightened cellular stress and energy deficiency that occurs in response to influenza, macrophage utilization of ketone bodies may help to regulate TCA cycle flux, modulate pyruvate-derived gluconeogenesis, and serve as an alternative source of ATP [25]. Metabolic reprogramming of macrophages in response to influenza highlights an age associated impact on the phenotypic characteristics that may impact not only the antimicrobial properties, but also influence dysregulated tissue repair and remodelling.

Our current results illustrate that daily administration of mitoquinol to aged adult mice improves IDO1 mediated metabolism of tryptophan to kynurenine; thereby, improving host innate immune responses and decreasing morbidity and mortality during the course of influenza. It is well appreciated that ROS signalling plays a key role in the initiation of innate immune responses during influenza, however overly heightened ROS production can result in excessive immune responses and have a deleterious impact on host tissue systems. Designed as a lipophilic molecule bearing a cation moiety, mitoquinol can pass directly through the mitochondrial membrane to increase the mitochondrial antioxidant capacity and decrease mitochondrial oxidative damage [26]. Further, mitoquinol can function as an antioxidant to prevent lipid peroxidation-induced apoptosis and protect mitochondria from oxidative damage [27]. Mitoquinol has been previously shown to be efficacious in reducing mitochondrial oxidative damage in multiple diseases, such as sepsis, fatty liver disease, and Alzheimer’s disease [27, 28]. Future work will need to be performed to understand the exact mechanistic pathways that are altered in response to mitoquinol treatment and if therapeutic administration of mitoquinol in additional pulmonary viral infection models will also prove to be efficacious.

It is important to note that IDO1 expression by epithelial cells and fibroblasts can also influence regulatory responses at the site of inflammation [29, 30]. Recent work has illustrated that expression of IDO in lung parenchyma can inhibit acute lethal pulmonary inflammation [31]. Specifically, the production of kynurenine by lung epithelial cells as well as alveolar macrophages can suppress inflammatory activities within the lung [31]. In agreement with these findings, when young adult mice were treated with IDO1 inhibitor, BMS-986205, there was a significant increase in inflammation and heightened lung injury during influenza infection. It is plausible, that in the absence of IDO1 activity and diminished kynurenine production, there is an inability of epithelial and alveolar macrophages to inhibit inflammation, resulting in increased morbidity and mortality during influenza. Previous work has illustrated that IDO1-deficient and 1-methyltryptophan treated mice are protected from morbidity during influenza A infection [4]. It is important to note that these studies examined the impact of IDO1 deficiency in young mice and it is possible that compensatory pathways may contribute to protection during influenza. Our data in young adult mice using BMS-986205 also illustrated an increase in morbidity during infection. We believe that this is due to the potent and selective IDO1 inhibitory properties of this compound when compared to 1-methyltryptophan, which has been shown to not induce effective in vivo IDO inhibition due to decreased potency and similar plasma concentrations of tryptophan post treatment [32]. While our current work focused on alveolar macrophages, future studies will need to investigate the contribution of epithelial cell production of kynurenine during influenza and the impact of aging on these responses.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Iuliano AD, Roguski KM, Chang HH, Muscatello DJ, Palekar R, Tempia S, Cohen C, Gran JM, Schanzer D, Cowling BJ, Wu P, Kyncl J, Ang LW, Park M, Redlberger-Fritz M, Yu H, Espenhain L, Krishnan A, Emukule G, van Asten L, Pereira da Silva S, Aungkulanon S, Buchholz U, Widdowson MA, Bresee JS, Global Seasonal Influenza-associated Mortality Collaborator N. Estimates of global seasonal influenza-associated respiratory mortality: a modelling study. Lancet 2018: 391(10127): 1285–1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaelings L, Soderholm S, Bugai A, Fu Y, Nandania J, Schepens B, Lorey MB, Tynell J, Vande Ginste L, Le Goffic R, Miller MS, Kuisma M, Marjomaki V, De Brabander J, Matikainen S, Nyman TA, Bamford DH, Saelens X, Julkunen I, Paavilainen H, Hukkanen V, Velagapudi V, Kainov DE. Regulation of kynurenine biosynthesis during influenza virus infection. FEBS J 2017: 284(2): 222–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fox JM, Sage LK, Huang L, Barber J, Klonowski KD, Mellor AL, Tompkins SM, Tripp RA. Inhibition of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase enhances the T-cell response to influenza virus infection. J Gen Virol 2013: 94(Pt 7): 1451–1461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang L, Li L, Klonowski KD, Tompkins SM, Tripp RA, Mellor AL. Induction and role of indoleamine 2,3 dioxygenase in mouse models of influenza a virus infection. PLoS One 2013: 8(6): e66546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taylor MW, Feng GS. Relationship between interferon-gamma, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase, and tryptophan catabolism. FASEB J 1991: 5(11): 2516–2522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frumento G, Rotondo R, Tonetti M, Damonte G, Benatti U, Ferrara GB. Tryptophan-derived catabolites are responsible for inhibition of T and natural killer cell proliferation induced by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. J Exp Med 2002: 196(4): 459–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fallarino F, Grohmann U, Vacca C, Bianchi R, Orabona C, Spreca A, Fioretti MC, Puccetti P. T cell apoptosis by tryptophan catabolism. Cell Death Differ 2002: 9(10): 1069–1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belladonna ML, Puccetti P, Orabona C, Fallarino F, Vacca C, Volpi C, Gizzi S, Pallotta MT, Fioretti MC, Grohmann U. Immunosuppression via tryptophan catabolism: the role of kynurenine pathway enzymes. Transplantation 2007: 84(1 Suppl): S17–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mezrich JD, Fechner JH, Zhang X, Johnson BP, Burlingham WJ, Bradfield CA. An interaction between kynurenine and the aryl hydrocarbon receptor can generate regulatory T cells. J Immunol 2010: 185(6): 3190–3198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grant RS, Passey R, Matanovic G, Smythe G, Kapoor V. Evidence for increased de novo synthesis of NAD in immune-activated RAW264.7 macrophages: a self-protective mechanism? Arch Biochem Biophys 1999: 372(1): 1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen W, Liang X, Peterson AJ, Munn DH, Blazar BR. The indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase pathway is essential for human plasmacytoid dendritic cell-induced adaptive T regulatory cell generation. J Immunol 2008: 181(8): 5396–5404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jurgens B, Hainz U, Fuchs D, Felzmann T, Heitger A. Interferon-gamma-triggered indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase competence in human monocyte-derived dendritic cells induces regulatory activity in allogeneic T cells. Blood 2009: 114(15): 3235–3243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Robinson CM, Hale PT, Carlin JM. The role of IFN-gamma and TNF-alpha-responsive regulatory elements in the synergistic induction of indoleamine dioxygenase. J Interferon Cytokine Res 2005: 25(1): 20–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hassanain HH, Chon SY, Gupta SL. Differential regulation of human indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase gene expression by interferons-gamma and -alpha. Analysis of the regulatory region of the gene and identification of an interferon-gamma-inducible DNA-binding factor. J Biol Chem 1993: 268(7): 5077–5084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaves AC, Ceravolo IP, Gomes JA, Zani CL, Romanha AJ, Gazzinelli RT. IL-4 and IL-13 regulate the induction of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase activity and the control of Toxoplasma gondii replication in human fibroblasts activated with IFN-gamma. Eur J Immunol 2001: 31(2): 333–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma KC, Schenck EJ, Siempos II, Cloonan SM, Finkelsztein EJ, Pabon MA, Oromendia C, Ballman KV, Baron RM, Fredenburgh LE, Higuera A, Lee JY, Chung CR, Jeon K, Yang JH, Howrylak JA, Huh JW, Suh GY, Choi AM. Circulating RIPK3 levels are associated with mortality and organ failure during critical illness. JCI Insight 2018: 3(13). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finkelsztein EJ, Jones DS, Ma KC, Pabon MA, Delgado T, Nakahira K, Arbo JE, Berlin DA, Schenck EJ, Choi AM, Siempos, II. Comparison of qSOFA and SIRS for predicting adverse outcomes of patients with suspicion of sepsis outside the intensive care unit. Crit Care 2017: 21(1): 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dolinay T, Kim YS, Howrylak J, Hunninghake GM, An CH, Fredenburgh L, Massaro AF, Rogers A, Gazourian L, Nakahira K, Haspel JA, Landazury R, Eppanapally S, Christie JD, Meyer NJ, Ware LB, Christiani DC, Ryter SW, Baron RM, Choi AM. Inflammasome-regulated cytokines are critical mediators of acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012: 185(11): 1225–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park J, Pabon M, Choi AMK, Siempos II, Fredenburgh LE, Baron RM, Jeon K, Chung CR, Yang JH, Park CM, Suh GY. Plasma surfactant protein-D as a diagnostic biomarker for acute respiratory distress syndrome: validation in US and Korean cohorts. BMC Pulm Med 2017: 17(1): 204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schenck EJ, Ma KC, Price DR, Nicholson T, Oromendia C, Gentzler ER, Sanchez E, Baron RM, Fredenburgh LE, Huh JW, Siempos II, Choi AM. Circulating cell death biomarker TRAIL is associated with increased organ dysfunction in sepsis. JCI Insight 2019: 4(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seok SH, Ma ZX, Feltenberger JB, Chen H, Chen H, Scarlett C, Lin Z, Satyshur KA, Cortopassi M, Jefcoate CR, Ge Y, Tang W, Bradfield CA, Xing Y. Trace derivatives of kynurenine potently activate the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR). J Biol Chem 2018: 293(6): 1994–2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bell DR, Poland A. Binding of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) to AhR-interacting protein. The role of hsp90. J Biol Chem 2000: 275(46): 36407–36414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chandler JD, Hu X, Ko EJ, Park S, Lee YT, Orr M, Fernandes J, Uppal K, Kang SM, Jones DP, Go YM. Metabolic pathways of lung inflammation revealed by high-resolution metabolomics (HRM) of H1N1 influenza virus infection in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 2016: 311(5): R906–R916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dantzer R Role of the Kynurenine Metabolism Pathway in Inflammation-Induced Depression: Preclinical Approaches. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2017: 31: 117–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newman JC, Verdin E. Ketone bodies as signaling metabolites. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2014: 25(1): 42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kelso GF, Porteous CM, Coulter CV, Hughes G, Porteous WK, Ledgerwood EC, Smith RA, Murphy MP. Selective targeting of a redox-active ubiquinone to mitochondria within cells: antioxidant and antiapoptotic properties. J Biol Chem 2001: 276(7): 4588–4596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gane EJ, Weilert F, Orr DW, Keogh GF, Gibson M, Lockhart MM, Frampton CM, Taylor KM, Smith RA, Murphy MP. The mitochondria-targeted anti-oxidant mitoquinone decreases liver damage in a phase II study of hepatitis C patients. Liver Int 2010: 30(7): 1019–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith RA, Hartley RC, Murphy MP. Mitochondria-targeted small molecule therapeutics and probes. Antioxid Redox Signal 2011: 15(12): 3021–3038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Aldajani WA, Salazar F, Sewell HF, Knox A, Ghaemmaghami AM. Expression and regulation of immune-modulatory enzyme indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) by human airway epithelial cells and its effect on T cell activation. Oncotarget 2016: 7(36): 57606–57617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curran TA, Jalili RB, Farrokhi A, Ghahary A. IDO expressing fibroblasts promote the expansion of antigen specific regulatory T cells. Immunobiology 2014: 219(1): 17–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee SM, Park HY, Suh YS, Yoon EH, Kim J, Jang WH, Lee WS, Park SG, Choi IW, Choi I, Kang SW, Yun H, Teshima T, Kwon B, Seo SK. Inhibition of acute lethal pulmonary inflammation by the IDO-AhR pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017: 114(29): E5881–E5890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gunther J, Dabritz J, Wirthgen E. Limitations and Off-Target Effects of Tryptophan-Related IDO Inhibitors in Cancer Treatment. Front Immunol 2019: 10: 1801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.