Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: cell adhesion molecules, cytokines, inflammation, thromboplastin, thrombosis

Objective:

In response to inflammatory insult, endothelial cells express cell adhesion molecules and TF (tissue factor), leading to increased adhesion of leukocytes to the endothelium and activation of coagulation. Enhanced coagulation could further exacerbate inflammation. Identifying key signaling molecule(s) that drive both inflammation and coagulation may help devise effective therapeutic strategies to treat inflammatory and thrombotic disorders. The aim of the current study is to determine the role of Gab2 (Grb2-associated binder2), which is known to play a crucial role in the signaling evoked by growth factors and antigen receptors, in inflammatory signaling pathways and its contribution to vascular dysfunction.

Approach and Results:

WT (wild type) and Gab2-silenced endothelial cells were treated with TNFα (tumor necrosis factor alpha), IL (interleukin)-1β, or lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Activation of key signaling proteins in the inflammatory signaling pathways and expression of cell adhesion molecules, TF, and inflammatory cytokines were analyzed. Gab2−/− and WT littermate mice were challenged with LPS or S pneumoniae (Streptococcus pneumoniae), and parameters of inflammation and activation of coagulation were assessed. Gab2 silencing in endothelial cells markedly attenuated TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, and LPS-induced expression of TF, cell adhesion molecules, and inflammatory cytokines/chemokines. Gab2 silencing suppressed TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, and LPS-induced phosphorylation and ubiquitination of TAK1 (transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1) and activation of MAPKs (mitogen-activated protein kinases) and NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa B). Immunoprecipitation studies revealed that the Src kinase Fyn phosphorylates Gab2. Gab2−/− mice are protected from LPS or S pneumoniae–induced vascular permeability, neutrophil infiltration, thrombin generation, NET formation, cytokine production, and lung injury.

Conclusions:

Our studies identify, for the first time, that Gab2 integrates signaling from multiple inflammatory receptors and regulates vascular inflammation and thrombosis.

Highlights.

Gab2 (Grb2-associated binder2) silencing suppresses the expression of cell adhesion molecules and inflammatory cytokines in endothelial cells in response to various inflammatory stimuli.

Gab2 integrates inflammatory signaling pathways initiated by various inflammatory receptors to a common downstream pathway via activation of TAK1 (transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1).

Gab2 deficiency confers resistance to endotoxin- and bacterial infection–induced vascular injury in mice.

Vascular endothelial cells play a crucial role in mediating inflammation in response to infection and other diseases, including atherosclerosis, sepsis, stroke, diabetes, and inflammatory bowel disease.1 Endothelial cells activated by TNFα (tumor necrosis factor alpha) and IL (interleukin)-1β, which are secreted by activated leukocytes, express CAMs (cell adhesion molecules), mainly ICAM1 (intercellular adhesion molecule 1), VCAM1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule 1), and E-selectin.2,3 Activated endothelial cells also secrete inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-6, IL-8, MCP1 (macrophage chemoattractant protein 1), and RANTES (regulated upon activation, normal T cell expressed and presumably secreted),4,5 and express procoagulant cofactor TF (tissue factor).6,7 Endothelial cell expression of CAMs, cytokines, and chemokines in response to tissue injury and infection plays crucial roles in the recruitment, rolling, and extravasation of leukocytes at the injury site.8 These events, along with the expression of TF, lead to thrombotic disorders, particularly venous thromboembolism.9–11

Inflammatory diseases such as sepsis, inflammatory bowel disease, and rheumatoid arthritis are associated with endothelial activation and increased risk for thrombosis.12–14 Acute inflammation was shown to drive the thrombosis in the animal models of arterial and venous thrombosis by multiple mechanisms, including increased expression of TF, CAMs, and chemokines.15,16 The generation of thrombin further amplifies the endothelial damage and inflammation, which leads to vascular dysfunction.17,18 Therefore, thromboinflammatory stress is considered a crucial event in the pathogenesis of thrombosis associated with inflammatory diseases.19,20 Identification of molecules that regulate both thrombosis and inflammation would help devise new drug targets to treat thrombotic disorders associated with inflammation.

Gab (Grb2-associated binding) proteins are a family of signaling adapter molecules, consisting of Gab1, Gab2 (Grb2-associated binder 2), and Gab3.21 Gab2 is a crucial molecule involved in the signaling of receptors of ILs, antigen complexes, and growth factors.21 Recently, Gab2 was shown to interact with a RANK (receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-Β) receptor—a TNF receptor superfamily—and mediates RANK-induced NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa B) and JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) activation.22 The Gab proteins are tyrosine phosphorylated upon the receptor activation and recruit signaling molecules that contain SH2 domains.21 Gab2 was shown to play a critical role in the progression of several types of cancers, which are known to associate with thrombosis and inflammation.23–26 Gab2 was found to be an Alzheimer disease susceptibility gene and is expressed in pathologically vulnerable regions of the brain.27–29 Gab2-knockout mice displayed reduced IgE receptor activation in mast cells and defects in bone formation.22,30 The loss of Gab2 in mice resulted in osteopetrosis due to defects in osteoclast differentiation.22 Although the mechanism of Gab2-mediated cell signaling,21,31 and its role in many pathophysiological processes, particularly in cancer, allergy, and osteoclastogenesis,22,30,32,33 is well established, the role of Gab2 in the inflammatory signaling is unknown. The current study was undertaken to fill this critical gap and test our hypothesis that Gab2 regulates vascular dysfunction by activating inflammation and coagulation.

Here, we show for the first time that Gab2 is a critical component that integrates the signaling induced by 3 inflammatory receptors, TNFR1 (tumor necrosis factor receptor 1), IL-1R (interleukin-1 receptor), and TLR4 (toll-like receptor 4), to the activation of ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) 1/2, p38 MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), JNK, and NF-κB in endothelial cells. Our studies show that Gab2 is activated by Fyn kinase upon the engagement of ligand to TNFR1, IL-1R, or TLR4. The activated Gab2 binds SHP2 (SH2 containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-2) and PLCγ2 (phospholipase C gamma) and activates TAK1 (transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1)—a central player in proinflammatory signaling pathways. Gab2−/− mice manifest reduced vascular permeability, cytokine production, leukocyte recruitment to the lungs, thrombin generation, and neutrophil extracellular trap formation (NETosis) in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) challenge and S pneumoniae (Streptococcus pneumoniae) pulmonary infection.

Materials and Methods

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Cells

Primary human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were cultured at 37 °C and 5% CO2 in a humidified incubator in the endothelial cell growth basal medium-2 supplemented with 2% fetal bovine serum and growth supplements (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). HUVEC passages between 4 and 8 were used in the present study. Murine brain endothelial cells were isolated from 8- to 10-week-old Gab2−/− mice and WT (wild type) littermate controls using the procedure described in our recent publication.34

Cell Treatments, Immunoprecipitation, and Immunoblotting

Confluent monolayers of HUVECs were treated with TNFα, IL-1β, or LPS, as indicated in Results and Figure Legends. At the end of the treatment period, cells were lysed in ice-cold cell lysis buffer (50 mmol/L HEPES, 2 mmol/L EDTA, 150 mmol/L NaCl, and 1% Triton X-100) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors single-use cocktail (Thermo Fisher). Cell lysates were incubated with the Gab2 polyclonal antibodies (Sigma) overnight at 4 °C. After that, 20 µL of protein A/G agarose beads were added to the reaction mixture and incubated at room temperature for 2 to 3 hours with constant rotation. The immunocomplexes were sedimented by centrifugation at 150g for 8 minutes at 4 °C. The pelleted agarose beads were washed 3× with the cell lysis buffer to remove the unbound material. The bound material was eluted by adding SDS-PAGE sample buffer (25 µL) to the beads and heating the sample at 95 °C for 15 minutes. Where no immunoprecipitation was involved, the cells were lysed directly in the SDS-PAGE sample buffer. An equal amount of protein or volume was subjected to SDS-PAGE and processed for immunoblot analysis to probe specific signaling proteins. The immunoblots were developed with chemiluminescence using Western Lightning Plus HRP substrate (Millipore). Densitometric analysis was performed using the Bio-Rad Chemi XRS system and Image J software.

Mice

Gab2+/− male and female mice, derived from cryo recovery, were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Gab2 heterozygotes were crossed to generate Gab2−/− and WT littermate controls. The 8- to 10-week-old mice, both males and females, were used in the present study.

LPS- or TNFα-Induced Lung Injury and Barrier Permeability

WT and Gab2−/− mice were administered with LPS (E coli [Escherichia coli] O111:B4, 5 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection. Six hours after the LPS challenge, blood was collected via a submandibular vein for isolation of plasma. The animals were euthanized and perfused transcardially with 20 mL of saline. Lung tissues were removed and processed for immunohistochemistry to evaluate immune cell infiltration or tissue extracts for measuring cytokines. For LPS-induced barrier permeability studies, mice were challenged with LPS (E coli O111:B4, 5 mg/kg, i.p.). After 16 hours following LPS administration, the vascular permeability in the lung and other tissues was evaluated as described earlier.35 For LPS-induced inflammation studies, mice were challenged with LPS (E coli O111:B4, 5 mg/kg, i.p.). After 24 hours following LPS administration, the plasma and lung tissues were collected. The thrombin-antithrombin (TAT) levels in the plasma were estimated by ELISA. For TNFα-induced lung injury, mice were administered with TNFα (50 µg/kg b.w) intravenously. Four hours after TNFα injection, mice were euthanized, and lung tissues were harvested as described above. All animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. All studies involving animals were conducted following the animal welfare guidelines outlined in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

S pneumoniae Infection

Mice were infected with S pneumoniae as described previously.36,37 Briefly, S pneumoniae (D39) was grown overnight on blood agar plates. The next day, bacteria were inoculated in 25 mL of Todd-Hewitt broth and cultured for 6 hours or until the bacteria reached the mid-log phase (absorbance at 600 nm 0.5). Bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation and resuspended in PBS to contain 1×109 CFU/mL. Gab2−/− and WT littermate control mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg) and xylazine (5 mg/kg) and infected with S pneumoniae intranasally (2×107 CFU/mouse in 20 µL). Control groups were administered with an equal volume of PBS intranasally.

Measurement of Cytokines

HUVECs were treated with TNFα, IL-1β, LPS, or a control vehicle for 15 hours. MCP1, IL-8, and IL-6 levels in cell supernatants were estimated using ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Lung tissues from mice were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and the frozen tissue was pulverized into powder. The powder was suspended in radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (Millipore) containing protease inhibitors. The tissue lysate was briefly sonicated and centrifuged at 10 000g for 20 minutes at 4 °C. TNFα, IL-6, IL-1β, and MCP1 levels in supernatants were measured using ELISA kits (eBioscience).

Tissue Sectioning, Immunohistochemistry, and Immunofluorescence Microscopy

Lung tissues were inflated and fixed with Excel fixative (Stat Lab, McKinney, TX) and processed for embedding in paraffin. Thin tissue sections (5 μm) were cut, deparaffinized, and rehydrated in the graded alcohols. The antigen retrieval was done by boiling tissue sections for 15 minutes in a 10-mmol/L citrate buffer (pH 6.0). Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched by incubating tissue sections with 3% hydrogen peroxide. After blocking the tissue sections with antibody diluent containing background reducing components (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), they were incubated with control IgG or rat anti-Ly6G (5 µg/mL), overnight at 4 °C. The sections were then incubated with biotin-labeled secondary antibodies (1:500), followed by ultrasensitive streptavidin-HRP (1:500; Sigma), and developed using AEC-hydrogen peroxide substrate solution. The sections were counterstained and mounted and visualized, and photomicrographs were captured with an Olympus BX41 microscope. For immunofluorescence studies, tissue sections were incubated with control IgG or goat anti-mouse MPO (myeloperoxidase) antibody (5 µg/mL) and rabbit anti-mouse citrullinated-histone H3 antibody (5 µg/mL) overnight at 4 °C. The sections were then incubated with Hoechst 33342, AF488-donkey anti-goat IgG, and AF647-donkey anti-rabbit IgG antibodies for 1 hour. After washing the sections, the sections were mounted in a Fluoro-gel mounting medium (Electron Microscopy Sciences), visualized, and imaged using LSM510 Zeiss confocal microscope.

Data Analysis

All experiments were repeated ≥3× independently. Data shown were either representative images or the mean±SD. In animal studies, 5 to 10 mice/group were randomly assigned. We compared male and female animal data separately and found no noticeable differences between the two groups. Therefore, the data from males and females were pooled in a group for statistical analysis. The distribution of the data was analyzed by Shapiro-Wilk or Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Since the data passed the normality test, we have analyzed the statistical significance using 1-way ANOVA or Student t test, as appropriate. GraphPad Prism, version 8.4.1, software was used for data analysis.

Results

Gab2 Silencing Inhibits TNFα-Induced, IL-1β–Induced, and LPS-Induced Activation of Endothelial Cells and Secretion of Inflammatory Mediators

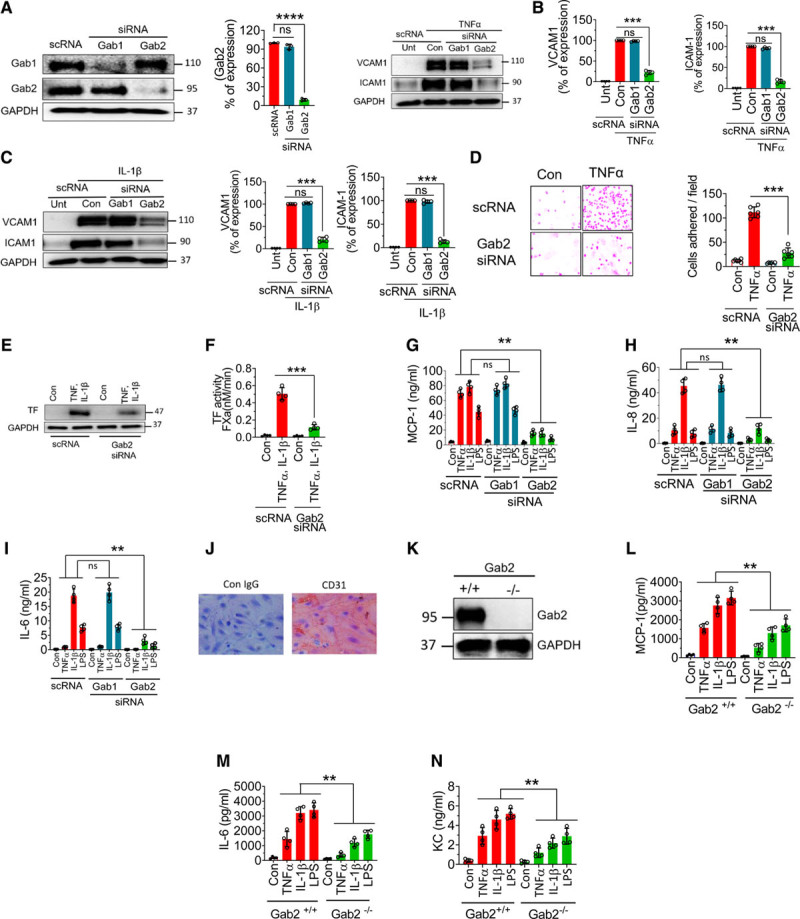

To investigate the role of Gabs in endothelial inflammation, we specifically knocked down the expression of Gab1 or Gab2 by using isoform-specific siRNAs. As shown in Figure 1A, Gab1 silencing specifically depleted Gab1 protein but not Gab2. Similarly, Gab2 silencing blocked Gab2 expression by about 90% and had no effect on Gab1 expression. Gab2 silencing significantly (P<0.001) attenuated TNFα-induced VCAM1 and ICAM1 expression in endothelial cells, whereas Gab1 silencing had no effect on TNFα-induced expression of ICAM1 or VCAM1 (Figure 1B). Similarly, Gab2, but not Gab1, silencing markedly reduced IL-1β–induced VCAM1 and ICAM1 expression (Figure 1C). Next, we analyzed the functional significance of Gab2 by silencing the Gab2 in endothelial cells and examining the adhesion of monocytes to the activated endothelium. Monocyte adhesion to activated endothelial cells is markedly reduced upon Gab2 silencing (Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Gab2 (Grb2-associated binder2) silencing or deficiency inhibits TNFα (tumor necrosis factor alpha)-induced, IL (interleukin)-1β–induced, or lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced proinflammatory responses in endothelial cells. A, Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were transfected with 200 nmol/L scrambled siRNA (scRNA), Gab1 (Grb2-associated binder 1), or Gab2 siRNA. After 48 h, the transfected cells were analyzed for the expression of Gab1 and Gab2 proteins by immunoblot analysis. Band intensities were quantified by densitometry, and these data are shown in the right. B and C, Gab1 or Gab2 silenced cells were treated with TNFα (10 ng/mL; B) or IL-1β (10 ng/mL; C) for 6 h. The cell lysates were analyzed for VCAM1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule 1) and ICAM1 (intercellular adhesion molecule 1) protein levels by immunoblot analysis. The blots shown on the left were representative. Band intensities were quantified by densitometry, and these data are shown in the right. D, HUVECs transfected with scrambled siRNA or Gab2 siRNA were treated with TNFα (10 ng/mL) for 6 h and then incubated with THP1 monocytic cells (5×105/mL). After 30 min, the nonadherent THP-1 cells were removed, and HUVEC monolayers were washed with serum-free medium. The adherent cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature for 30 min. The cells were stained using crystal violet dye. The adherent cells were visualized under a bright-field microscope at ×20 magnification. The images in the left depict representative images. The number of cells adhered/field was determined by counting multiple fields in ≥3 experiments performed independently and averaging them per field (right). E and F, HUVECs transfected with scrambled siRNA or Gab2 siRNA were treated with TNFα and IL-1β (10 ng/mL each) for 6 h, and TF (tissue factor) expression was analyzed by immunoblotting (E) or functional activity (F). TF functional activity was measured by adding FVIIa (10 nmol/L) and substrate factor X (175 nmol/L) to the cells in a calcium-containing buffer and measuring the amount of FXa generated at 5 min. G–I, HUVECs were transfected with scrambled, Gab1, or Gab2 siRNA. After 48 h, the transfected cells were treated with TNFα (10 ng/mL), IL-1β (10 ng/mL), or LPS (500 ng/mL) for 15 h. The supernatants were collected, and the levels of MCP1 (macrophage chemoattractant protein 1; G), IL-8 (H), and IL-6 (I) were measured in ELISA. J, Brain endothelial cells isolated from Gab2−/− mice were stained with endothelial marker CD31 (cluster of differentiation). K, Immunoblot showing the complete absence of Gab2 in the brain endothelial cells from Gab2−/− mice. L and M, Mouse brain endothelial cells isolated from Gab2−/− or WT (wild type) littermate control mice were serum starved overnight and treated with TNFα (20 ng/mL), IL-1β (20 ng/mL), or LPS (1 µg/mL) for 15 h. The supernatants were collected and assayed for MCP-1 (L), IL-6 (M), and KC (keratinocyte-derived chemokine, the mouse ortholog of human interleukin-8; N) levels in ELISA. For data shown in A through D, Student t test was used to calculate statistically significant differences. For others, 1-way ANOVA was used to compare the data of experimental groups, and Tukey post hoc multiple comparison test was used to obtain statistical significance between the two groups. ns indicates no statistically significant difference. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001.

Proinflammatory mediators induce TF expression in endothelial cells, which triggers the activation of the coagulation cascade and contributes to inflammation.38 As expected, unperturbed endothelial cells did not express TF, whereas TNFα+IL-1β treatment induced robust expression of TF (Figure 1E). Gab2 silencing markedly reduced TNFα+IL-1β–induced expression of TF in endothelial cells (Figure 1E). Measurement of TF activity showed that TNFα+IL-1β treatment increased cell surface TF activity by >20-fold over unstimulated cells, and Gab2 silencing reduced the TNFα+IL-1β–induced TF activity by about 80% (Figure 1F).

Next, we investigated the role of Gab2 in cytokine- and LPS-induced expression of inflammatory mediators, such as MCP1, IL-8, and IL-6. All 3 agonists, TNFα, IL-1β, and LPS, markedly induced the expression of MCP1, IL-8, and IL-6 but to varying extents (Figure 1G through 1I). Gab2 silencing resulted in about ≥80% reduction in TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, or LPS-induced expression of MCP1, IL-8, and IL-6. In contrast to Gab2 silencing, Gab1 silencing had no effect on TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, or LPS-induced expression of MCP1, IL-8, or IL-6 (Figure 1G through 1I). The above studies indicate that Gab2 plays a critical role in transmitting the TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, and LPS-induced cell signaling and cytokine secretion. To strengthen the above finding, we used primary brain microvascular endothelial cells isolated from Gab2−/− mice and WT littermate controls. The isolated endothelial cells appeared to be homogenous as all the cells expressed endothelial cell–specific marker CD31 (cluster of differentiation; Figure 1J). As expected, endothelial cell–isolated Gab2−/− mice were completely devoid of the Gab2 protein (Figure 1K). All 3 agonists, TNFα, IL-1β, and LPS, markedly increased the secretion of MCP1, IL-6, and KC (the murine IL-8 homolog) in WT murine endothelial cells. However, the increased expression of MCP1, IL-6, and KC was significantly (P<0.01) lower in Gab2−/− cells compared with WT cells in response to inflammatory stimuli (Figure 1L through 1N).

In additional experiments, we assessed LPS-induced cytokine elaboration in peritoneal macrophages isolated from Gab2−/− and WT mice. We found a modest decrease in the LPS-induced IL-6 secretion in the macrophages of Gab2−/− mice compared with WT mice (Figure I in the Data Supplement).

Role of SHP2 and Akt in Gab2-Mediated Endothelial Inflammation

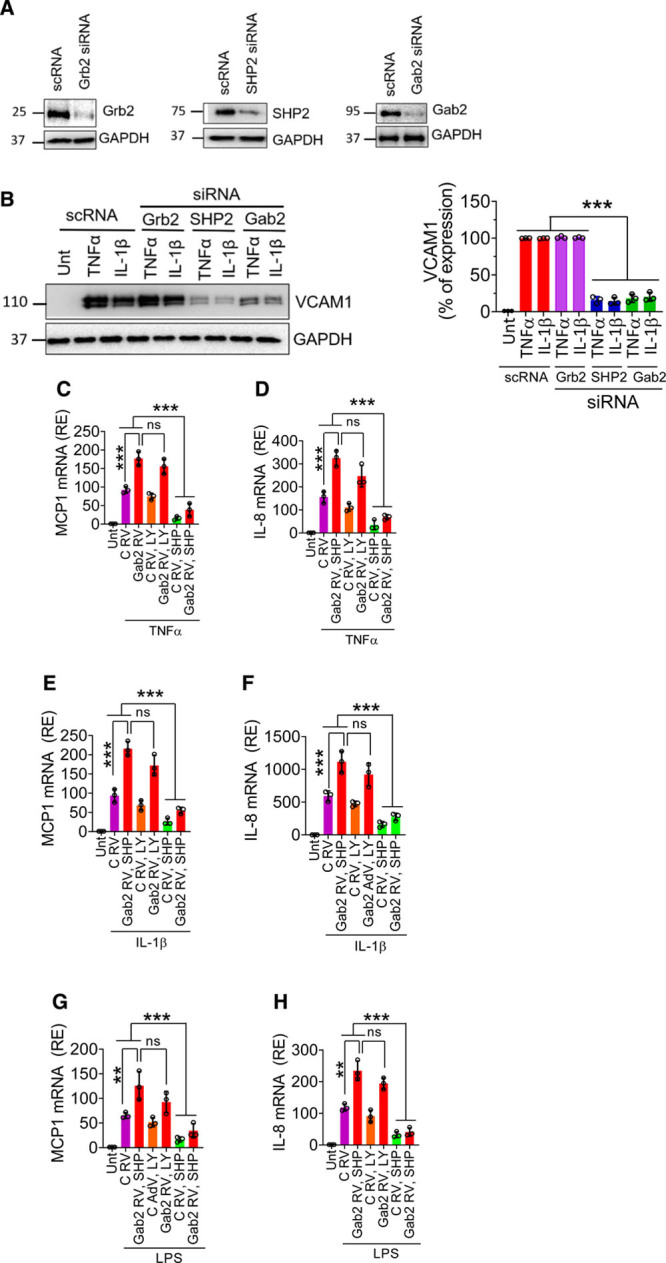

Gab2 was known to transmit downstream signaling via interaction with Grb2, p85, and SHP2.21 Akt (protein kinase B) and SHP2 play a key role in cytokine-induced endothelial inflammation.39–42 Therefore, we investigated whether Gab2 activates endothelial cells via SHP2 or Akt. We silenced the expression of Grb2, SHP2, and Gab2 in the endothelial cells using specific siRNA. The immunoblots show that the siRNA markedly depleted the Grb2, SHP2, and Gab2 (Figure 2A). As expected, HUVECs treated with TNFα or IL-1β significantly (P<0.001) upregulated the expression of VCAM1. Grb2 knockdown did not affect the agonist-induced VCAM1 expression, whereas SHP2 or Gab2 silencing markedly suppressed the VCAM1 expression (Figure 2B). In further studies, to determine the role of Akt and SHP2 in Gab2-mediated signaling, we have overexpressed Gab2 using retrovirus in the endothelial cells, and the cells were treated with specific inhibitors for PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase; LY294002) or SHP2 (SHP099) before stimulating them with TNFα, IL-1β, or LPS. Infection of endothelial cells with Gab2 retrovirus significantly (P<0.001) upregulated the TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, or LPS-induced expression of MCP1 and IL-8, compared with the control virus infection (Figure 2C through 2H). More importantly, SHP2, and not PI3K inhibition, markedly reduced Gab2-mediated enhanced expression of MCP1 and IL-8 in endothelial cells stimulated with TNFα, IL-1β, or LPS (Figure 2C through 2H). These data strongly suggest that Gab2 transmits proinflammatory signaling via SHP2, independent of Akt.

Figure 2.

The involvement of Grb2 (growth factor receptor-bound protein 2), PI3K (phosphoinositide 3-kinase), or SHP2 (SH2 containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-2) in Gab2 (Grb2-associated binder2)-mediated inflammatory signaling. A, Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were transfected with 200 nmol/L scrambled, Grb2, SHP2, or Gab2 siRNA for 48 h. The gene silencing was confirmed by immunoblotting. B, The transfected cells were treated with TNFα (tumor necrosis factor alpha), IL (interleukin)-1β (10 ng/mL), or lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 500 ng/mL) for 6 h. VCAM1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule 1) expression was analyzed by immunoblot analysis. Band intensities were quantified by densitometry, and the quantified data are shown in the right. C–H, HUVECs were left untreated (Unt), infected with control (C RV) or Gab2 retrovirus (Gab2 RV) were treated with LY294002 (5 µmol/L, LY) or SHP099 (0.5 µmol/L, SHP) for 1 h. Then, the cells were treated with TNFα (C and D), IL-1β (E and F), or LPS (G and H) for 6 h. The total RNA was extracted from the cells and MCP1 (macrophage chemoattractant protein 1; C, E, and G), IL-8 (D, F, and H) mRNA expression levels were measured by qRT-PCR. Results were expressed as relative expression (RE) to the control. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the data of experimental groups; Tukey post hoc multiple comparison test was used to obtain statistical significance. ns indicates no statistically significant difference. ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001.

Gab2 Silencing Blocks TNFα- and IL-1β–Induced Activation of ERK1/2, p38 MAPK, JNK, and NF-κB

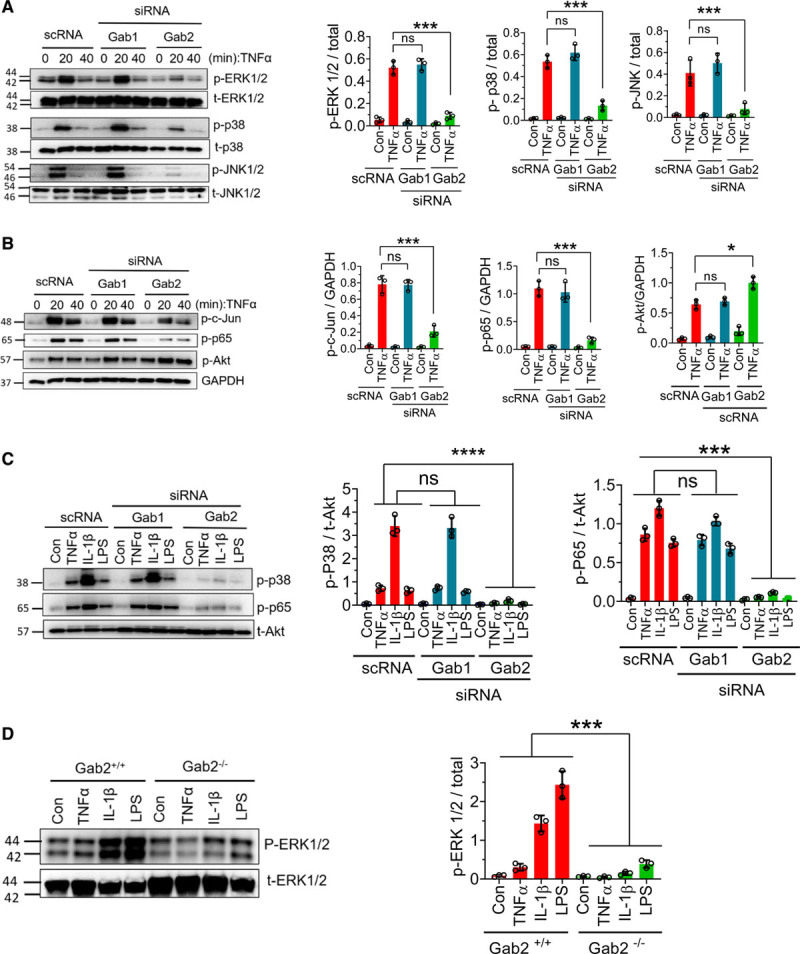

TNFα, IL-1β, and LPS are known to activate MAPKs and NF-κB pathways and transmit their signaling to the nucleus for inflammatory gene expression. To elucidate the potential mechanism by which Gab2 regulates endothelial cell inflammation, we first investigated the effect of Gab2 silencing on TNFα-induced activation of various signaling pathways. As expected, TNFα induced the activation of MAPK signaling molecules—ERK1/2, p38, and JNK1/2 (Figure 3A). Activation of these signaling molecules was robust at 20 minutes following TNFα treatment but comes down to base levels by 40 minutes (Figure 3A). Gab2 silencing blocked the TNFα-induced phosphorylation of ERK1/2, p38, and JNK1/2, as well as the downstream activation of transcription factors c-jun and NF-κB (p65; Figure 3A and 3B). Gab1 silencing had no detectable effect on TNFα-induced activation MAPKs, c-jun, or NF-κB (Figure 3A and 3B). Interestingly, Gab2 silencing modestly but significantly (P<0.05) increased the TNFα-induced Akt activation in endothelial cells (Figure 3B).

Figure 3.

Gab2 (Grb2-associated binder2) silencing blocks TNFα (tumor necrosis factor alpha)-induced, IL (interleukin)-1β–induced, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced signaling in the endothelial cells. A and B, Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) transfected with Gab1 (Grb2-associated binder 1) or Gab2 siRNA or scrambled siRNA (scRNA) were serum starved overnight and treated with TNFα (10 ng/mL) for the indicated times. The cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis to probe for the phosphorylated (p) ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase) 1/2, JNK (c-Jun N-terminal kinase) 1/2, p38, Akt (protein kinase B), c-Jun, and NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa B; p65) using phospho-specific antibodies. Immunoblots were also probed for total (t) ERK1/2, p38, JNK1/2, or GAPDH for loading controls. Band intensities at the 20 min time point were quantified by densitometry, and these data are shown in the right. C, HUVECs transfected with Gab1 or Gab2 siRNA or scrambled siRNA were treated with TNFα (10 ng/mL), IL-1β (10 ng/mL), or LPS (500 ng/mL) for 30 min. The cell lysates were analyzed for the activation of p38 and NF-κB (p65) by immunoblot analysis. Band intensities were quantified by densitometry, and these data are shown in the right. D, Mouse brain endothelial cells isolated from Gab2−/− or WT (wild type) littermate control mice (Gab2+/+) were serum starved overnight and treated with TNFα (20 ng/mL), IL-1β (20 ng/mL), or LPS (1 µg/mL) for 30 min. The cell lysates were evaluated for the phosphorylation of ERK1/2 by immunoblot analysis. Band intensities were quantified by densitometry, and the quantified data are shown in the right. Student t test was used to calculate statistically significant differences for data shown in A and B. For others, 1-way ANOVA was used to compare the data of experimental groups, and Tukey post hoc multiple comparison test was used to obtain statistical significance between the two groups. ns indicates no statistically significant difference. ***P<0.001. Con indicates control vehicle.

Next, we investigated whether Gab2 also plays a role in IL-1β–induced and LPS-induced activation of p38 and NF-kB in endothelial cells. IL-1β was more potent than TNFα and LPS in inducing the activation of p38 and NF-kB. Similar to the data obtained with TNFα stimulus, Gab1 silencing did not affect IL-1β–induced or LPS-induced activation of p38 and NF-kB, whereas Gab2 silencing completely attenuated their activation (Figure 3C).

In additional studies, we used brain endothelial cells isolated from Gab2−/− mice and WT littermate controls to confirm the role of Gab2 in MAPK signaling. IL-1β or LPS treatment induced the robust activation of ERK in endothelial cells isolated from WT mice but not Gab2−/− mice (Figure 3D).

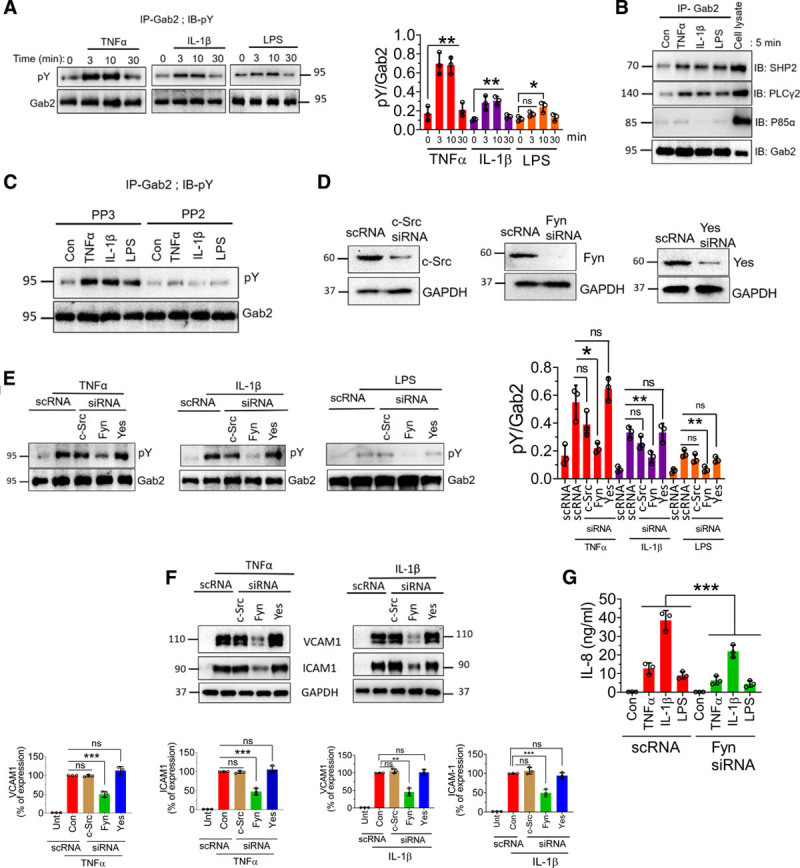

TNFα, IL-1β, and LPS Induce Fyn Kinase–Mediated Phosphorylation of Gab2

The interactions of Gab2 with other signaling molecules are dependent on its phosphorylation status.43,44 Growth factors and other agonists induce Gab2 phosphorylation at multiple tyrosine residues, which induce association of several SH2 domain–containing proteins, such as Grb2, SHP2, PLCγ2, and P85α, to Gab2 to initiate the signaling.23,45 Therefore, we investigated whether TNFα, IL-1β, or LPS induces the phosphorylation of Gab2. All 3 agonists induced the phosphorylation of Gab2 (Figure 4A). TNFα-induced Gab2 tyrosine phosphorylation was evident as early as 3 minutes. The phosphorylation was stable up to 10 minutes and returned to the basal level by 30 minutes (Figure 4A). The pattern of IL-1β–induced and LPS-induced phosphorylation of Gab2 was similar to that of TNFα, but they phosphorylated Gab2 to a lower extent (Figure 4A). Next, we analyzed the association of Gab2 with its interacting partners SHP2, PLCγ2, and P85α following stimulation of endothelial cells with TNFα, IL-1β, or LPS. All 3 agonists induced a notable increase in the association of SHP2, PLCγ, but not P85α, with Gab2 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

TNFα (tumor necrosis factor alpha), IL (interleukin)-1β, and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) induce the phosphorylation of Gab2 (Grb2-associated binder2) and association of Gab2 with its interacting partners, SHP2 (SH2 containing protein tyrosine phosphatase-2) and PLCγ (phospholipiase C gamma). A, Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were treated with TNFα (10 ng/mL), IL-1β (10 ng/mL), or LPS (500 ng/mL) for the indicated times. The cells were lysed in the radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease inhibitors. Gab2 was immunoprecipitated (IP) using the Gab2 polyclonal antibody, followed by protein A/G agarose bead pull-down. The Gab2 immunoprecipitates were subjected to immunoblot analysis (IB) and probed with a phosphotyrosine (pY)-specific monoclonal antibody to evaluate the phosphorylation of Gab2. Band intensities were quantified by densitometry, and these data are shown in the right. B, HUVECs were treated with the TNFα (10 ng/mL), IL-1β (10 ng/mL), LPS (500 ng/mL), or a control vehicle for 5 min. The Gab2 was immunoprecipitated, and the immunoprecipitates were probed for SHP2, PLCγ, or P85α by immunoblot analysis using specific monoclonal antibodies against SHP2, PLCγ, or P85α. C, HUVECs were incubated with Src inhibitor PP2 (10 µmol/L) or its inactive analog PP3 (10 µmol/L) for 1 h. Then, the cells were treated with the agonists for 5 min. The Gab2 was immunoprecipitated and probed with a pY monoclonal antibody to evaluate the tyrosine phosphorylation of Gab2. D, HUVECs were transfected with 200 nmol/L of scrambled siRNA (scRNA) or siRNA specific for c-Src, Fyn, or Yes. After 48 h, the cell lysates were harvested and probed for expression of c-Src (cellular Src), Fyn, or Yes in immunoblot analysis. E, HUVECs transfected with a scrambled siRNA or siRNA specific for c-Src, Fyn, or Yes were treated with TNFα (10 ng/mL), IL-1β (10 ng/mL), or LPS (500 ng/mL) for 5 min. Gab2 was immunoprecipitated and probed for tyrosine phosphorylation using the pY monoclonal antibody in immunoblot analysis. Band intensities were quantified by densitometry, and these data are shown in the right. F, HUVECs transfected with scRNA, c-Src, Fyn, or Yes siRNA were treated with TNFα (10 ng/mL) and IL-1β (10 ng/mL) for 6 h. VCAM1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule 1) and ICAM1 (intercellular adhesion molecule 1) levels were analyzed by immunoblotting, and band intensities were quantified by densitometry, and these data are shown in the bottom. G, HUVECs transfected with scRNA or Fyn siRNA were treated with TNFα (10 ng/mL), IL-1β (10 ng/mL), or LPS (500 ng/mL) overnight, and IL-8 levels in cell supernatants were determined in ELISA. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the data of experimental groups; Tukey post hoc multiple comparison test was used to obtain statistical significance. ns indicates no statistically significant difference. ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05. Con indicates control; and Unt, untreated.

Several Src kinases have been implicated in the phosphorylation of Gab2, including c-Src, Fyn, and Yes.46–48 Therefore, we next investigated which Src kinase is responsible for TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, or LPS-induced phosphorylation of Gab2. In the first set of experiments, we treated HUVEC with an Src kinase inhibitor, PP2, or an inactive analog, PP3. Treatment of HUVEC with PP2 completely abrogated the TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, or LPS-induced phosphorylation of Gab2 (Figure 4C). Inactive analog PP3 failed to diminish TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, or LPS-induced phosphorylation of Gab2 (Figure 4C). To identify specific Src kinase involved in the phosphorylation of Gab2, we specifically knocked down the expression of c-Src, Fyn, or Yes in endothelial cells using specific siRNAs and then stimulated the cells with TNFα, IL-1β, or LPS. Silencing of c-Src, Fyn, and Yes depleted the protein expression of the respective Src kinase (Figure 4D). Analysis of Gab2 phosphorylation revealed that Fyn, but not c-Src or Yes, knockdown inhibited the TNFα-induced Gab2 phosphorylation (Figure 4E). Similar results were observed with IL-1β or LPS stimulation (Figure 4E).

Next, we investigated whether the knockdown of Fyn, which inhibited Gab2 phosphorylation, diminishes the inflammatory signaling, as observed in Gab2 knockdown endothelial cells. As shown in Figure 4F and 4G, the silencing of Fyn, but not c-Src or Yes, significantly suppressed the TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, or LPS-induced VCAM1, ICAM1, and IL-8 expression in endothelial cells. These results provide direct evidence that the Fyn-Gab2 axis regulates proinflammatory signaling in endothelial cells.

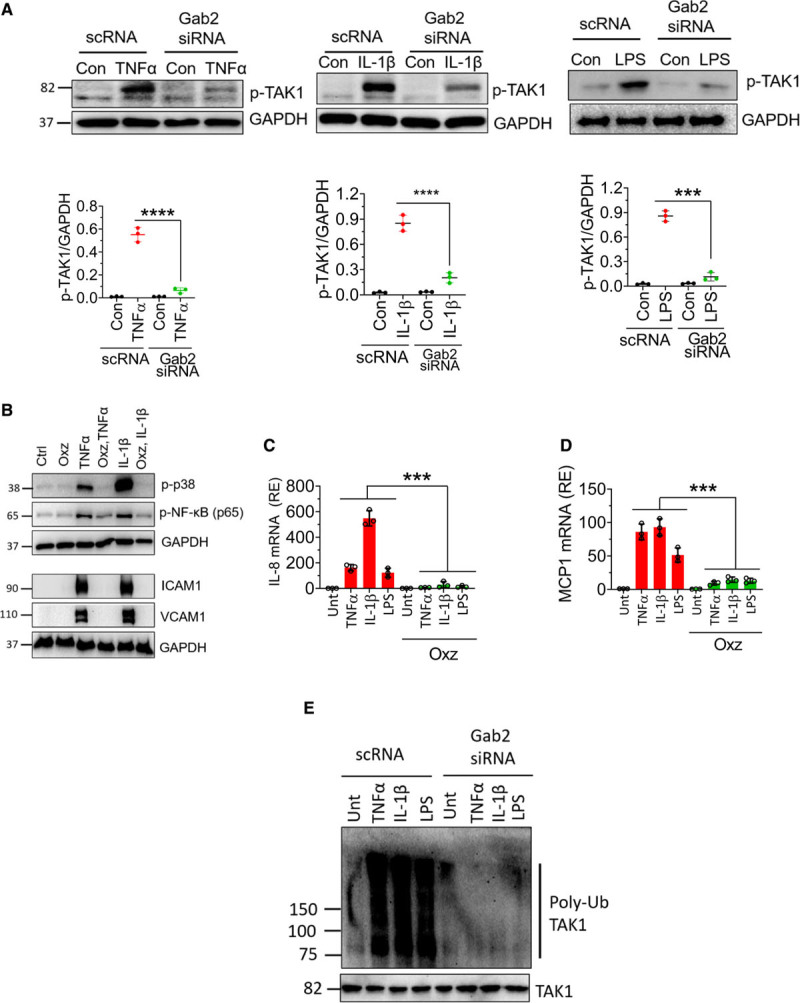

Gab2 Silencing Inhibits Phosphorylation and Ubiquitination of TAK1

It is well established that all 3 stimuli, that is, TNFα, IL-1β, and LPS, induce the activation of TAK1.49 TAK1 is known to activate MAPKs and NF-κB.49,50 Therefore, Gab2 may regulate TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, and LPS-induced cell signaling through modulation of TAK1. To investigate this, we evaluated the phosphorylation of TAK1. All 3 agonists, TNFα, IL-1β, and LPS, increased TAK1 phosphorylation in endothelial cells (Figure 5A). Gab2 silencing markedly reduced TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, or LPS-induced TAK1 activation (Figure 5A). To confirm the observation that inhibition of TAK1 activation in Gab2-silenced endothelial cells is responsible for attenuation of inflammatory signaling, HUVECs were treated with a TAK1 inhibitor, oxozeaenol, before activating the cells with TNFα or IL-1β. Oxozeaenol treatment completely inhibited TNFα- or IL-1β–induced activation of p38 MAPK and NF-κB activation (Figure 5B). The expression of VCAM1 and ICAM1 was also completely suppressed in HUVECs treated with oxozeaenol. Next, we analyzed the chemokine expression of cells treated with TNFα, IL-1β, or LPS in the presence or absence of oxozeaenol. Oxozeaenol treatment markedly reduced TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, and LPS-induced MCP-1 and IL-8 production in endothelial cells (Figure 5C and 5D). It is pertinent to note here that oxozeaenol treatment had no effect on cell viability as assessed in MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide) and trypan blue exclusion assays (data not shown). Overall, the above data confirm that TAK1 plays a predominant role in the proinflammatory cytokine-induced inflammatory gene expression.

Figure 5.

Gab2 (Grb2-associated binder2) silencing inhibits TAK1 (transforming growth factor beta-activated kinase 1) phosphorylation and ubiquitination, and TAK1 inhibition suppresses Gab2-dependent endothelial activation. A, Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) transfected with Gab2 siRNA or scrambled siRNA (scRNA) were serum starved overnight and treated with TNFα (tumor necrosis factor alpha; 10 ng/mL), IL (interleukin)-1β (10 ng/mL), or lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 500 ng/mL) for 5 min. The cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis to probe for the phosphorylation of TAK1 using phospho-specific antibodies. Band intensities were quantified by densitometry, and these data are shown in the bottom. B, HUVECs were incubated with TAK inhibitor oxozeaenol (Oxz; 10 µmol/L) or DMSO vehicle for 1 h in the serum-free medium. Then, the cells were treated with TNFα or IL-1β for 30 min or 6 h. The cell lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis to probe for the activation of p38 MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase) and NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa B) and the expression of VCAM1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule 1) and ICAM1 (intercellular adhesion molecule 1). C and D, HUVECs were treated with Oxz (10 µmol/L) or DMSO vehicle for 1 h in the serum-free medium. Then, the cells were treated with TNFα, IL-1β, or LPS for 6 h. The total RNA was extracted from the cells and IL-8 (C), MCP1 (macrophage chemoattractant protein 1; D) mRNA expression was measured by qRT-PCR. Results were expressed as relative expression to the control. E, HUVECs transfected with Gab2 siRNA or scrambled siRNA (scRNA) were serum starved overnight and treated with TNFα (10 ng/mL), IL-1β (10 ng/mL), or LPS (500 ng/mL) for 5 min. The cells were lysed in the radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing protease inhibitors. TAK1 in cell homogenates was immunoprecipitated using the TAK1 monoclonal antibody. The TAK1 immunoprecipitates were probed with a ubiquitin-specific monoclonal antibody to evaluate the ubiquitination of TAK1. The Student t test was used to calculate statistical significance for the data shown in A. In C and D, One-way ANOVA with Tukey post hoc multiple comparison test was used to obtain statistical significance. ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001. Con or ctrl indicate control vehicle treated; p-TAK1, phosphor-TAK1; and Unt, untreated.

The ubiquitination of TAK1 was essential for MAPK and NF-κB activation. Therefore, we next investigated whether Gab2 regulates the ubiquitination of TAK1 during TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, or LPS-induced cell signaling. All 3 agonists induced the ubiquitination of TAK1 in endothelial cells. Gab2 silencing completely inhibited the TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, or LPS-induced ubiquitination of TAK1 (Figure 5E). In controls, cells incubated with scrambled siRNA did not affect TAK1 ubiquitination. Overall, the above data suggest that TAK1 is an upstream effector of MAPK and NF-κB and Gab2 modulates the cytokine signaling in endothelial cells at the upstream of TAK1 activation.

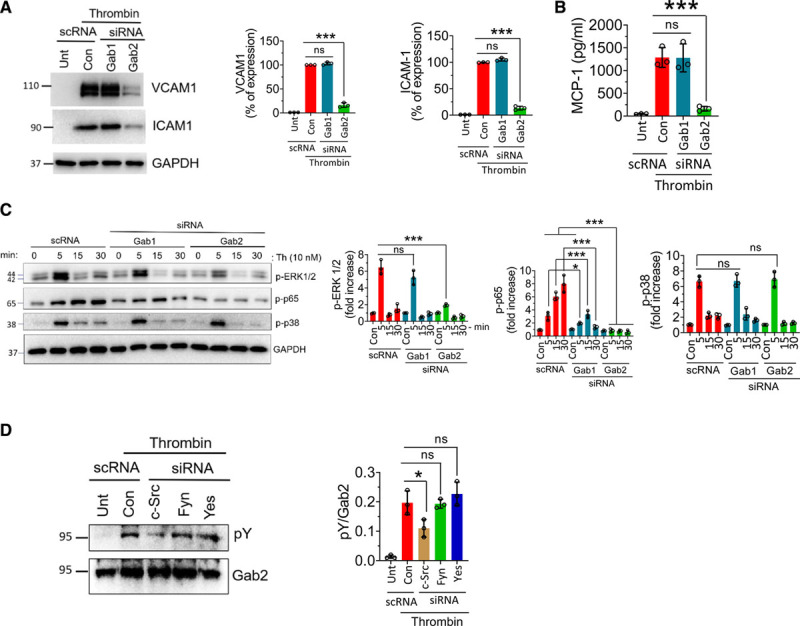

Gab2 Silencing Blocks Thrombin-Induced Cell Signaling and Inflammation in Endothelial Cells

Thrombin is a pluripotent proinflammatory factor that upregulates CAMs and chemokines in the endothelial cells.17,51 To determine the role of Gabs in thrombin-induced signaling, we silenced Gab1 or Gab2 and activated the endothelial cells with thrombin. Thrombin treatment upregulated the expression of VCAM1, ICAM1, and MCP1 (Figure 6A and 6B). Gab2 silencing significantly attenuated the thrombin-induced expression of CAMs and MCP1 (Figure 6A and 6B). Thrombin robustly activated ERK 1/2 and p38 MAPK in 5 minutes, and the levels of activated ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK returned to base levels at 15 minutes (Figure 6C). Gab2, and not Gab1, silencing suppressed the activation of ERK. Interestingly, neither Gab1 nor Gab2 silencing inhibited thrombin-induced p38 MAPK activation (Figure 6C). Thrombin persistently activated NF-κB from 5 to 30 minutes. Gab2 silencing completely suppressed thrombin-induced activation of NF-κB, whereas Gab1 silencing showed a significant decrease in the NF-κB activation (Figure 6C).

Figure 6.

Gab2 (Grb2-associated binder2) silencing suppresses thrombin-induced signaling and inflammation in endothelial cells. A, Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were transfected with 200 nmol/L scrambled siRNA (scRNA), Gab1, or Gab2 siRNA. After 48 h, the cells were treated with thrombin (10 nmol/L) for 6 h. The cell lysates were analyzed for VCAM1 (vascular cell adhesion molecule 1) and ICAM1 (intercellular adhesion molecule 1) protein levels by immunoblot analysis. Band intensities were quantified by densitometry, and these data are shown in the right. B, HUVECs transfected with scrambled, Gab1, or Gab2 siRNA were treated with thrombin for 6 h, and the MCP-1 (macrophage chemoattractant protein 1) levels were analyzed in the cell supernatants by ELISA. C, HUVECs transfected with Gab1 or Gab2 siRNA were treated with thrombin for indicated time points, and the activation of ERK (extracellular signal-regulated kinase), p38 MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), and NF-κB (nuclear factor kappa B) was analyzed by immunoblot analysis using antibodies that recognize phosphorylated (p) ERK, p38, or p65. Band intensities were quantified by densitometry, and these data are shown in the right. D, HUVECs were transfected with a scrambled siRNA or siRNA specific for c-Src (cellular Src), Fyn, or Yes. After 48 h, the cells were treated with thrombin for 5 min. Gab2 was immunoprecipitated and probed for tyrosine phosphorylation using the pY monoclonal antibody in immunoblot analysis. Band intensities were quantified by densitometry, and these data are shown in the right. Data were representative of 3 independent experiments with similar results. One-way ANOVA was used to compare the data of experimental groups, Tukey post hoc multiple comparison test was used to obtain statistical significance. ns indicates no statistically significant difference. ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05. Con indicates control; and Unt, untreated.

We next investigated whether thrombin induces the phosphorylation of Gab2. Thrombin was found to induce the phosphorylation of Gab2 (Figure 6D). Unlike to that observed in TNFα- and IL-1β–treated endothelial cells, c-Src, and not Fyn, knockdown significantly inhibited the thrombin-induced Gab2 phosphorylation (Figure 6D).

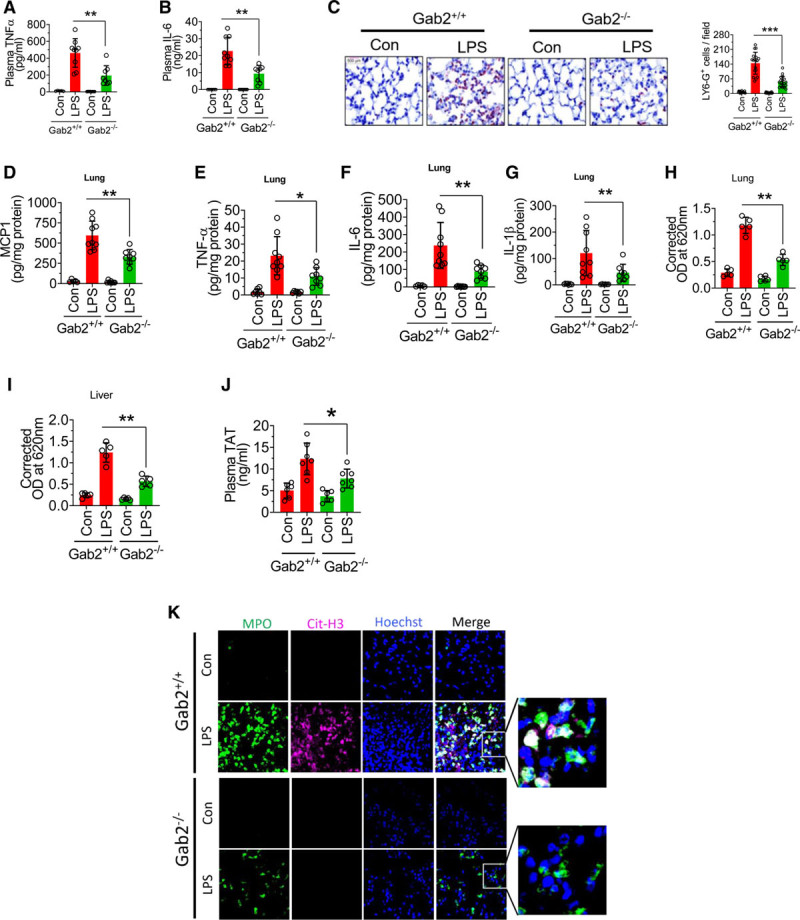

Gab2−/− Mice Are Resistant to LPS-Induced Lung Injury and Coagulation

To determine the significance of the role of Gab2 in inflammatory signaling in vivo, Gab2−/− and WT littermate controls were challenged with LPS, and the levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the systemic circulation were measured. LPS administration to WT mice markedly increased the levels of TNFα and IL-6 in the plasma compared with mice administered with a control vehicle. Gab2 deficiency attenuated the marked increase in TNFα and IL-6 levels in the plasma of mice challenged with LPS (Figure 7A and 7B). Analysis of neutrophil infiltration in the lung tissues showed that LPS markedly increased neutrophil infiltration in the lung tissues of WT mice, whereas Gab2 deficiency significantly (P<0.001) reduced the number of neutrophils infiltrated into the lungs in response to LPS administration (Figure 7C). Gab2 deficiency also significantly (P<0.01) reduced LPS-induced increased levels of TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and MCP1 in the lung tissues (Figure 7D through 7G). LPS-induced systemic inflammation leads to increased vascular permeability. Therefore, we next investigated whether Gab2 deficiency protects mice against LPS-induced vascular permeability. LPS treatment increased the vascular permeability in WT mice lungs by about 4-fold. LPS-induced vascular leakage was significantly (P<0.001) lower in Gab2−/− mice lungs (Figure 7H). Similar results were observed in the liver tissue (Figure 7I).

Figure 7.

Gab2 (Grb2-associated binder2)−/− mice were resistant to lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced systemic inflammation. Gab2−/− and WT (wild type) littermate control mice (Gab2+/+) were administered with LPS (5 mg/kg body weight) intraperitoneally. Six hours following LPS administration, blood was collected via submandibular vein puncture. TNFα (tumor necrosis factor alpha; A) and IL (interleukin)-6 (B) levels in plasma were measured by ELISA. C, The lung tissue sections were immunostained with neutrophil marker LY-6G. The sections were visualized under ×40 magnification. The number of LY-6G–positive cells were counted at 3 randomly chosen areas covering the entire sections of 6 different mice. Left, Representative images of tissue sections stained with LY-6G. Right, Count of LY-6G–stained cells/field. D–G, The lung tissue lysates were assayed for MCP-1 (D), TNFα (E), IL-6 (F), or IL-1β (G) using ELISA. H and I, Gab2−/− and WT littermate control mice were administered with LPS (5 mg/kg b.w) i.p. After 16 h, 100 µL of 1% Evans blue dye was injected into the mice via intravenously. After 1 h, the mice were euthanized, perfused transcardially with saline. Lung and liver tissues were collected, and Evans blue dye associated with the lungs (H) and the liver (I) was measured as the index for vascular permeability. J and K, Gab2−/− and WT littermate control mice (Gab2+/+) were administered with LPS (5 mg/kg b.w) i.p. Twenty-four hours following LPS administration, blood was collected via submandibular vein puncture and lung tissues were harvested. Plasma thrombin-antithrombin levels were measured by ELISA (J). The lung tissue sections were immunostained for MPO (myeloperoxidase; green) and citrullinated-histone H3 (Cit-H3; magenta). DNA was stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue; K). The sections were visualized under ×63 magnification. Student t test was used to calculate statistical significant differences. ****P<0.0001, ***P<0.001, **P<0.01, *P<0.05. Con indicates control vehicle; and OD, optical density.

LPS-induced inflammation triggers the activation of coagulation and thrombin generation.14,52 Therefore, we measured TAT generation as a marker of coagulation activation. Analysis of TAT levels in the plasma showed that LPS significantly elevated TAT levels in both WT and Gab2−/− mice over their respective control vehicle treatments. However, the increase in TAT levels in LPS-administered Gab2−/− mice was significantly lower compared with LPS-administered WT mice (Figure 7J).

In additional studies, we investigated the effect of Gab2 deficiency on LPS-induced NETosis. LPS treatment markedly induced citrullination of histones in neutrophils, a characteristic marker of NETs, in the lung tissues of WT mice (Figure 7K). LPS-induced NETs formation was markedly lower in Gab2−/− mice (Figure 7K). Overall, the above data suggest that Gab2 plays a crucial role in neutrophil infiltration and triggers coagulation and inflammation in endotoxemia.

Gab2−/− Mice Are Protected From TNFα-Induced Lung Injury

Our in vitro studies suggest that Gab2 integrates signaling evoked by both LPS and TNFα. From the above studies, it is difficult to distinguish whether the reduction in LPS-induced inflammation observed in Gab2−/− mice is due to attenuation of LPS-induced signaling, TNFα-induced signaling, or both as LPS induces the expression of TNFα. To investigate the direct role of Gab2 in the TNFα-induced signaling in vivo, Gab2−/− mice and WT littermate controls were administered with TNFα. The lung tissue sections were immunostained to assess neutrophil infiltration into the lungs. Like LPS, the administration of TNFα into WT mice induced neutrophil infiltration into the lungs, as evidenced by increased Ly-6G–positive cells in the lung tissue sections (Figure IIA in the Data Supplement). The neutrophil infiltration was significantly (P<0.001) blunted in the Gab2−/− mice (Figure IIA in the Data Supplement). Consistent with the neutrophil infiltration, we found a marked increase in MCP1 levels in the lung tissue of TNFα-administered WT mice. MCP1 levels were significantly (P<0.01) lower in Gab2−/− mice challenged with TNFα (Figure IIB in the Data Supplement). The above data suggest that Gab2 deficiency protects against TNFα-induced inflammation and lung injury.

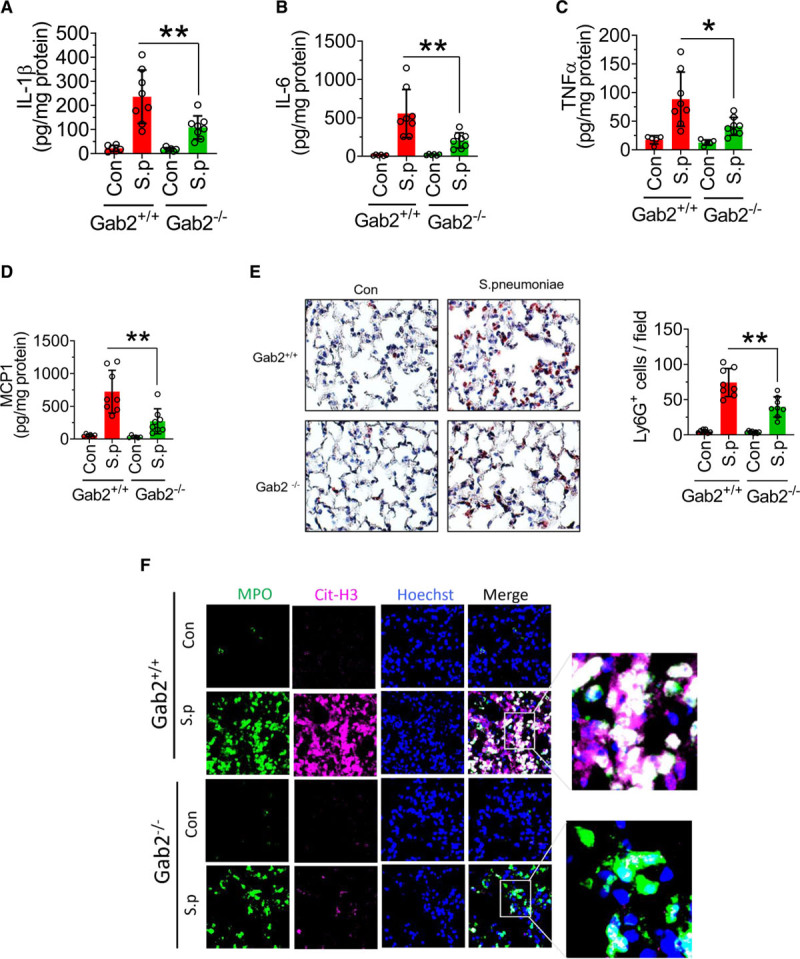

Gab2−/− Mice Are Protected From S pneumoniae–Induced Lung Injury

To determine the role of Gab2 in bacterial infection–induced acute lung injury, Gab2−/− and WT littermate control mice were infected with S pneumoniae. S pneumoniae infection markedly elevated the levels of TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and MCP1 in the lung tissues of WT mice compared with mice administered with a control vehicle (Figure 8A through 8D). Gab2 deficiency significantly attenuated S pneumoniae–induced TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and MCP-1 levels in the lungs (Figure 8A through 8D). Analysis of neutrophil infiltration in the lung tissues showed that S pneumoniae infection markedly increased neutrophil infiltration in the lung tissues of WT mice, whereas Gab2 deficiency significantly (P<0.001) reduced the number of neutrophils infiltrated into the lungs (Figure 8E). Furthermore, S pneumoniae infection elevated the citrullination of histones in the MPO+ leukocytes in WT mice, suggesting an increased NET formation (Figure 8F). The bacteria-induced NET formation was attenuated in Gab2−/− mice (Figure 8F).

Figure 8.

Gab2 (Grb2-associated binder2)−/− mice were protected from Spneumoniae (Streptococcus pneumoniae) infection–induced lung inflammation and injury. A–D, Gab2−/− and WT (wild type) littermate control mice (Gab2+/+) were intranasally infected with S pneumoniae (2×107 cfu/mouse). Twenty-four hours following the infection, the lung tissues were collected, and lung tissue homogenates were assayed for IL (interleukin)-1β (A), IL-6 (B), TNFα (tumor necrosis factor alpha; C), or MCP-1 (macrophage chemoattractant protein 1; D) by ELISA. E, The lung tissue sections were immunostained with neutrophil marker LY-6G. The sections were visualized under ×40 magnification. The number of LY-6G–positive cells was counted at multiple randomly chosen areas covering the entire section of 4 different mice. Left, Representative images of tissue sections stained with LY-6G. Right, Count of LY-6G–stained cells/field. F, The lung tissue sections were immunostained for MPO (myeloperoxidase; green) and citrullinated-histone H3 (Cit-H3; magenta). DNA was stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). The sections were visualized under ×63 magnification. Student t test was used to calculate statistically significant differences. *P<0.05, **P<0.01. Con indicates control vehicle-treated; and S.p, S. pneumoniae-infected.

Discussion

The current study unveils a novel and critical role of Gab2 in mediating TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, and LPS-induced proinflammatory signaling. The data presented in the article show that Gab2 silencing in endothelial cells blocks TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, and LPS-induced activation of MAPKs and NF-κB and expression of CAMs, TF, cytokines, and chemokines. Consistent with the data obtained in cell model systems that Gab2 plays a critical role in endothelial cell inflammation, Gab2−/− mice were found to be resistant to the LPS-,TNFα-, or bacterial infection–induced inflammation and vascular leakage. These studies are the first to document that Gab2 plays a central role in mediating TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, and LPS-induced inflammatory signaling.

Leukocyte adhesion to the endothelium and their recruitment into the tissues is an essential and multistep process of inflammation. β1- and β2-integrins, LFA-1 (lymphocyte function-associated antigen 1; CD11a/CD18), Mac-1 (macrophage-1 antigen; CD11b/CD18), and VLA4 (very late antigen 4; CD49d/CD29) on leukocytes interact with their counter ligands, such as ICAM1 or VCAM1, on endothelial cells.53–55 VCAM1 facilitates the adhesion of monocytes via VLA4, whereas ICAM1 serves as a binding site for LFA-1 and Mac-1 on monocytes and neutrophils.55 In the current study, we found that Gab2 silencing in endothelial cells markedly suppressed the expression of both VCAM1 and ICAM1. The reduced expression of VCAM1 and ICAM1 in Gab2-silenced endothelial cells is likely to be responsible for reduced adhesion of monocytic cells to endothelial cell monolayer in vitro and lower neutrophil infiltration into the lungs in Gab2−/− mice in vivo in the present study. At present, it is unknown whether Gab2 deficiency alters the expression of CAMs on leukocytes and whether this contributes to reduced neutrophil infiltration observed in Gab2−/− mice.

TNFR1-induced inflammation and cytokine synthesis in endothelial cells is mediated by the concerted action of PI3K, NF-κB, ERK, JNK, and p38 MAPK pathways.56 TNFR1 is coupled to these downstream pathways through TRAFs, particularly TRAF2.57,58 Similarly, TRAF6 mediates the TLR4/IL-1R–induced MAPK/NF-κB activation.50 Overall, the existing literature indicates that a diverse set of signaling molecules regulate upstream signaling events of TNFR1 and TLR4/IL-1R pathways, but they all converge downstream at TAK1 activation.49,59 Our present data identify that the molecular adapter protein Gab2 functions as a master regulatory switch that converges various upstream signaling events initiated by different inflammatory stimuli to a common downstream signaling before TAK1 activation.

TAK1 is thought to be the master kinase that activates both MAPK and NF-κB signaling cascades.50 TAK1 is activated by binding to the ubiquitin polymers that are generated by the TNFR1/TRAF2/RIP1 (receptor-interacting protein 1) or TLR4/IL-1R/TRAF6 signaling complexes.49 It had been demonstrated that Lys63-linked polyubiquitination at Lys158 was essential for its own kinase activation and its ability to mediate downstream signal transduction pathways in response to TNFα and IL-1β stimulation.60 Sorrentino et al61 showed that TGF induces TAK1 activation via TRAF6-mediated Lys63-linked TAK1 polyubiquitination at the Lys34 residue. In agreement with these studies, in the current study, we found that TAK1 was ubiquitinated upon TNFα, IL-1β, or LPS treatments in endothelial cells. Gab2 silencing completely inhibited the TAK1 ubiquitination indicating that Gab2 is essential for ubiquitination and activation of TAK1. Currently, we do not know the precise mechanism by which Gab2 regulates TAK1 activation. Further studies are needed to determine the molecular mechanism of Gab2-mediated ubiquitination of TAK1.

Upon stimulation, Gab2 protein becomes tyrosine phosphorylated and acts as a molecular bridge between the epidermal growth factor or IL-2/IL-15–activated receptor complexes and the downstream signaling molecules.21 In line with these studies, we found that activation of inflammatory TNFR1, IL-1R, or TLR4 signaling pathways leads to tyrosine phosphorylation of Gab2 in endothelial cells. The Src kinases, Fyn, Lyn, Syc, and Yes, were implicated in the phosphorylation of Gab2.46,48,62 Furthermore, activation of Src kinases was also linked to the TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, and LPS-induced cell signaling, vascular barrier permeability, and inflammation in the endothelial cells.63–66 Until now, there were no links established between the activation of TNFR1, IL-1R, and TLR4, and Gab2 phosphorylation. Our current study is the first to report that activation of TNFR1, IL-1R, and TLR4 leads to tyrosine phosphorylation of Gab2. Our studies identify Fyn kinase is responsible for Gab2 phosphorylation in endothelial cells following stimulation with TNFα, IL-1β, or LPS. Previous studies showed that Fyn was recruited to the lipid rafts following TNFR1 activation.67 Fyn silencing was shown to inhibit TNFα- or LPS-induced barrier permeability in the endothelial cells.63,64 Recent studies demonstrated that Src-induced caveolin-1 phosphorylation was essential for TLR4 signaling in endothelial cells and LPS-induced lung injury and sepsis.65 More importantly, Fyn but not Lyn kinase deficiency protects mice during nephritis and arthritis.68 Fyn deficiency also protects macrophage accumulation and adipose inflammation and improves insulin sensitivity in mice.69,70 Although the above studies demonstrate the essential role of Src kinases during acute inflammation, the downstream signaling molecules that transmit the signaling were unknown. Our data identify the important role of the Src kinase in mediating TNFα, IL-1β, or LPS signaling through the activation of Gab2. We provide direct evidence that the Fyn-Gab2 axis mediates the TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, and LPS-induced proinflammatory effects in the vascular endothelium.

A plethora of evidence suggests that growth factors, ILs, and antigen receptors activate the PI3K/Akt pathway via Gab2.21,71 Gab2 was known to interact with the p85 subunit of PI3K.30 Given the importance of Akt in the TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, and LPS-induced signaling and inflammatory gene expression,72 we expected that Gab2 silencing inhibits Akt activation in endothelial cells. Contrary to our expectation, Gab2 silencing did not affect TNFα-induced, IL-1β–induced, or LPS-induced activation of Akt. Consistent with the data that Gab2 does not regulate Akt activation, we found no interaction of p85—a regulatory subunit of PI3K—with the activated Gab2, whereas other binding proteins, SHP2 and PLCγ, readily bound to Gab2. Furthermore, PI3K-specific inhibitor showed no significant decrease in the chemokine expression induced by TNFα and IL-1β. These studies underscore that Gab2 activates TAK1 independent of Akt.

Consistent with the data obtained in the endothelial cell model system, Gab2−/− mice were less susceptible to endotoxin- or bacterial infection–induced cytokine secretion, neutrophil infiltration, NET formation, and lung injury. However, the use of global Gab2-deficient mice in the present study does not allow us to conclude that the observed protective effects seen in Gab2−/− mice in vivo are due to the loss of Gab2-mediated inflammatory signaling in endothelial cells. Published studies suggest that Gab2 is expressed by macrophages, and Gab2/SHP2/PI3K-mediated signaling substantially contributes to cytokine secretion and phagocytosis in these cells.31 It is possible that concerted loss of Gab2-mediated signaling in both endothelial cells and leukocytes may likely be responsible for the reduced lung injury in Gab2−/− mice. However, endothelial cells play a predominant role in the tissue injury by orchestrating aberrant neutrophil recruitment through the expression of CAMs, chemokine secretion and opening of cellular junctions, and increase in the vascular permeability.2,73 Therefore, it is likely that the loss of Gab2-mediated inflammatory signaling in endothelial cells contributes to the overall phenotype of Gab2−/− mice in endotoxemia or S pneumoniae infection.

Interestingly, our in vivo studies also showed that Gab2 deficiency markedly attenuated NETosis. At present, it is unknown whether the reduced NETosis observed in Gab2−/− mice is the result of the loss of Gab2 signaling in neutrophils, endothelial cells, or other cell types. Activation of endothelial cells was shown to induce NETosis.74 It is possible that reduced NETosis observed in Gab2−/− mice may be due to reduced endothelial cell inflammation in these mice.

The vascular alterations due to the expression of CAMs, TF, and recruitment of leukocytes into the vessel wall contribute to the pathogenesis of stroke and neurological disorders.75–77 Mutations on Gab2 or overexpression of Gab2 was shown to correlate to the neuropathology of Alzheimer disease.27–29 The single-nucleotide polymorphism of Gab2 single-nucleotide polymorphism rs2373115 confers susceptibility to Alzheimer disease.28,78–80 Data from animal models and patients of neurological diseases strongly indicate that vascular complications, such as increased vascular permeability, fibrin deposition, and leukocyte recruitment, precede the onset of the disease.81–83 The molecular connection between the expression of Gab2 and the incidence of the above diseases remains unclear. It is possible that Gab2-mediated endothelial dysfunction may play a role in the above disorders.

In conclusion, we report that Gab2 is a molecular adapter that couples TNFR1/IL-1R/TLR4 to downstream signaling pathways required for inflammatory gene expression. Loss of Gab2 results in markedly reduced TNFR1/IL-1R/TLR4-induced expression of CAMs, TF, cytokines, and chemokines in endothelial cells in vitro and protects against LPS- and S pneumoniae–induced inflammation. Our in vitro data in endothelial cells support the concept that endothelial Gab2-mediated cell signaling in vivo plays a crucial role in inflammation and lung injury through the elevation of CAMs, chemokine secretion, vascular permeability, and neutrophil recruitment into the tissues. However, future studies involving cell-specific Gab2 knockout mice are necessary to define the contribution of endothelial- and other cell type–specific Gab2 signaling in inflammation, NETosis, activation of coagulation, and the lung injury. Our data identify for the first time that Gab2 is a key mediator of TNFR1/IL-1R/TLR4-induced inflammatory signaling in endothelial cells. Targeting Gab2 could be an attractive and novel strategy to treat inflammatory and thrombotic complications.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to Dr Benjamin Neel (NYU School of Medicine) for providing a retroviral construct expressing Gab2 (Grb2-associated binder2). V. Kondreddy performed most of the experiments described in this article, analyzed the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. J. Magisetty performed experiments related to peritoneal macrophages. S. Keshava performed the experiments related to immunofluorescence microscopy. L.V.M. Rao and U.R. Pendurthi contributed to the study design, reviewed the data, and wrote the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final version of the manuscript and approved its submission to the publication.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute HL107483 and HL120455, and endowment funds from The Dr and Mrs James Vaughn Professorship in Biomedical Research to L.V.M. Rao.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Akt

- protein kinase B

- CAM

- cell adhesion molecule

- ERK

- extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- Gab2

- Grb2-associated binder 2

- HUVEC

- human umbilical vein endothelial cell

- ICAM1

- intercellular adhesion molecule 1

- IL

- interleukin

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MCP1

- macrophage chemoattractant protein 1

- MPO

- myeloperoxidase

- NETosis

- neutrophil extracellular trap formation

- NF-κB

- nuclear factor kappa B

- TAT

- thrombin-antithrombin

- TF

- tissue factor

- TNFα

- tumor necrosis factor alpha

- VCAM1

- vascular cell adhesion molecule 1

- WT

- wild-type

The Data Supplement is available with this article at https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/suppl/10.1161/ATVBAHA.121.316153.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 2004.

Contributor Information

Vijay Kondreddy, Email: vijay.kondreddy@uthct.edu.

Jhansi Magisetty, Email: Jhansi.Magisetty@uthct.edu.

Shiva Keshava, Email: shivakeshava.gaddam@uthct.edu.

References

- 1.Pober JS, Sessa WC. Evolving functions of endothelial cells in inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:803–815. doi: 10.1038/nri2171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nourshargh S, Alon R. Leukocyte migration into inflamed tissues. Immunity. 2014;41:694–707. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kondreddy V, Wang J, Keshava S, Esmon CT, Rao LVM, Pendurthi UR. Factor VIIa induces anti-inflammatory signaling via EPCR and PAR1. Blood. 2018;131:2379–2392. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-10-813527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Surmi BK, Hasty AH. The role of chemokines in recruitment of immune cells to the artery wall and adipose tissue. Vascul Pharmacol. 2010;52:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.vph.2009.12.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Øynebråten I, Bakke O, Brandtzaeg P, Johansen FE, Haraldsen G. Rapid chemokine secretion from endothelial cells originates from 2 distinct compartments. Blood. 2004;104:314–320. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams JC, Mackman N. Tissue factor in disease and health. Front Biosci. 2012;E4:358–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Osterud B, Bjorklid E. Tissue factor in blood cells and endothelial cells. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2012;4:289–299. doi: 10.2741/376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Langer HF, Chavakis T. Leukocyte-endothelial interactions in inflammation. J Cell Mol Med. 2009;13:1211–1220. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00811.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schulz C, Engelmann B, Massberg S. Crossroads of coagulation and innate immunity: the case of deep vein thrombosis. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11(suppl 1):233–241. doi: 10.1111/jth.12261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Branchford BR, Carpenter SL. The role of inflammation in venous thromboembolism. Front Pediatr. 2018;6:142. doi: 10.3389/fped.2018.00142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Budnik I, Brill A. Immune factors in deep vein thrombosis initiation. Trends Immunol. 2018;39:610–623. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2018.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ocak G, Vossen CY, Verduijn M, Dekker FW, Rosendaal FR, Cannegieter SC, Lijfering WM. Risk of venous thrombosis in patients with major illnesses: results from the MEGA study. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:116–123. doi: 10.1111/jth.12043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SC, Schneeweiss S, Liu J, Solomon DH. Risk of venous thromboembolism in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2013;65:1600–1607. doi: 10.1002/acr.22039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simmons J, Pittet JF. The coagulopathy of acute sepsis. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2015;28:227–236. doi: 10.1097/ACO.0000000000000163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esmon CT. The impact of the inflammatory response on coagulation. Thromb Res. 2004;114:321–327. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2004.06.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anyanwu AC, Kanthi Y, Fukase K, Liao H, Mimura T, Desch KC, Gruca M, Kaskar S, Sheikh-Aden H, Chi L, et al. Tuning the thromboinflammatory response to venous flow interruption by the ectonucleotidase CD39. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019;39:e118–e129. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.119.312407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Popović M, Smiljanić K, Dobutović B, Syrovets T, Simmet T, Isenović ER. Thrombin and vascular inflammation. Mol Cell Biochem. 2012;359:301–313. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-1024-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cate Ht, Hemker HC. Thrombin generation and atherothrombosis: what does the evidence indicate? J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5:e003553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Meyer SF, Denorme F, Langhauser F, Geuss E, Fluri F, Kleinschnitz C. Thromboinflammation in stroke brain damage. Stroke. 2016;47:1165–1172. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.011238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Irving PM, Pasi KJ, Rampton DS. Thrombosis and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:617–628. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00154-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishida K, Hirano T. The role of Gab family scaffolding adapter proteins in the signal transduction of cytokine and growth factor receptors. Cancer Sci. 2003;94:1029–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01396.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wada T, Nakashima T, Oliveira-dos-Santos AJ, Gasser J, Hara H, Schett G, Penninger JM. The molecular scaffold Gab2 is a crucial component of RANK signaling and osteoclastogenesis. Nat Med. 2005;11:394–399. doi: 10.1038/nm1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adams SJ, Aydin IT, Celebi JT. GAB2–a scaffolding protein in cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:1265–1270. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-12-0352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sattler M, Mohi MG, Pride YB, Quinnan LR, Malouf NA, Podar K, Gesbert F, Iwasaki H, Li S, Van Etten RA, et al. Critical role for Gab2 in transformation by BCR/ABL. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:479–492. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00074-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Franco AT, Corken A, Ware J. Platelets at the interface of thrombosis, inflammation, and cancer. Blood. 2015;126:582–588. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-531582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cantrell R, Palumbo JS. The thrombin-inflammation axis in cancer progression. Thromb Res. 2020;191(suppl 1):S117–S122. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(20)30408-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schjeide BM, Hooli B, Parkinson M, Hogan MF, DiVito J, Mullin K, Blacker D, Tanzi RE, Bertram L. GAB2 as an Alzheimer disease susceptibility gene: follow-up of genomewide association results. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:250–254. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reiman EM, Webster JA, Myers AJ, Hardy J, Dunckley T, Zismann VL, Joshipura KD, Pearson JV, Hu-Lince D, Huentelman MJ, et al. GAB2 alleles modify Alzheimer’s risk in APOE epsilon4 carriers. Neuron. 2007;54:713–720. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.05.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ikram MA, Liu F, Oostra BA, Hofman A, van Duijn CM, Breteler MM. The GAB2 gene and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease: replication and meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:995–999. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gu H, Saito K, Klaman LD, Shen J, Fleming T, Wang Y, Pratt JC, Lin G, Lim B, Kinet JP, et al. Essential role for Gab2 in the allergic response. Nature. 2001;412:186–190. doi: 10.1038/35084076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gu H, Neel BG. The “Gab” in signal transduction. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:122–130. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(03)00002-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding CB, Yu WN, Feng JH, Luo JM. Structure and function of Gab2 and its role in cancer (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:4007–4014. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2015.3951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vaughan TY, Verma S, Bunting KD. Grb2-associated binding (Gab) proteins in hematopoietic and immune cell biology. Am J Blood Res. 2011;1:130–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kondreddy V, Pendurthi UR, Xu X, Griffin JH, Rao LVM. FVIIa (Factor VIIa) induces biased cytoprotective signaling in mice through the cleavage of PAR (Protease-Activated Receptor)-1 at canonical Arg41 (Arginine41) site. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2020;40:1275–1288. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.120.314244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sen P, Gopalakrishnan R, Kothari H, Keshava S, Clark CA, Esmon CT, Pendurthi UR, Rao LV. Factor VIIa bound to endothelial cell protein C receptor activates protease activated receptor-1 and mediates cell signaling and barrier protection. Blood. 2011;117:3199–3208. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-310706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Warszawska JM, Gawish R, Sharif O, Sigel S, Doninger B, Lakovits K, Mesteri I, Nairz M, Boon L, Spiel A, et al. Lipocalin 2 deactivates macrophages and worsens pneumococcal pneumonia outcomes. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3363–3372. doi: 10.1172/JCI67911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parker D, Martin FJ, Soong G, Harfenist BS, Aguilar JL, Ratner AJ, Fitzgerald KA, Schindler C, Prince A. Streptococcus pneumoniae DNA initiates type I interferon signaling in the respiratory tract. mBio. 2011;2:e00016–e00011. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00016-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Witkowski M, Landmesser U, Rauch U. Tissue factor as a link between inflammation and coagulation. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2016;26:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2015.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Di Lorenzo A, Fernández-Hernando C, Cirino G, Sessa WC. Akt1 is critical for acute inflammation and histamine-mediated vascular leakage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:14552–14557. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904073106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mukai Y, Rikitake Y, Shiojima I, Wolfrum S, Satoh M, Takeshita K, Hiroi Y, Salomone S, Kim HH, Benjamin LE, et al. Decreased vascular lesion formation in mice with inducible endothelial-specific expression of protein kinase Akt. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:334–343. doi: 10.1172/JCI26223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Giri H, Muthuramu I, Dhar M, Rathnakumar K, Ram U, Dixit M. Protein tyrosine phosphatase SHP2 mediates chronic insulin-induced endothelial inflammation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:1943–1950. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.239251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.You M, Flick LM, Yu D, Feng GS. Modulation of the nuclear factor kappa B pathway by Shp-2 tyrosine phosphatase in mediating the induction of interleukin (IL)-6 by IL-1 or tumor necrosis factor. J Exp Med. 2001;193:101–110. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.1.101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crouin C, Arnaud M, Gesbert F, Camonis J, Bertoglio J. A yeast two-hybrid study of human p97/Gab2 interactions with its SH2 domain-containing binding partners. FEBS Lett. 2001;495:148–153. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02373-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu Y, Jenkins B, Shin JL, Rohrschneider LR. Scaffolding protein Gab2 mediates differentiation signaling downstream of Fms receptor tyrosine kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:3047–3056. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.9.3047-3056.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gu H, Pratt JC, Burakoff SJ, Neel BG. Cloning of p97/Gab2, the major SHP2-binding protein in hematopoietic cells, reveals a novel pathway for cytokine-induced gene activation. Mol Cell. 1998;2:729–740. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80288-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu J, Meng F, Lu H, Kong L, Bornmann W, Peng Z, Talpaz M, Donato NJ. Lyn regulates BCR-ABL and Gab2 tyrosine phosphorylation and c-Cbl protein stability in imatinib-resistant chronic myelogenous leukemia cells. Blood. 2008;111:3821–3829. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-109330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yu M, Lowell CA, Neel BG, Gu H. Scaffolding adapter Grb2-associated binder 2 requires Syk to transmit signals from FcepsilonRI. J Immunol. 2006;176:2421–2429. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Parravicini V, Gadina M, Kovarova M, Odom S, Gonzalez-Espinosa C, Furumoto Y, Saitoh S, Samelson LE, O’Shea JJ, Rivera J. Fyn kinase initiates complementary signals required for IgE-dependent mast cell degranulation. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:741–748. doi: 10.1038/ni817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Newton K, Dixit VM. Signaling in innate immunity and inflammation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4:a006049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang C, Deng L, Hong M, Akkaraju GR, Inoue J, Chen ZJ. TAK1 is a ubiquitin-dependent kinase of MKK and IKK. Nature. 2001;412:346–351. doi: 10.1038/35085597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Foley JH, Conway EM. Cross talk pathways between coagulation and inflammation. Circ Res. 2016;118:1392–1408. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.306853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pawlinski R, Mackman N. Cellular sources of tissue factor in endotoxemia and sepsis. Thromb Res. 2010;125(suppl 1):S70–S73. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2010.01.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gahmberg CG. Leukocyte adhesion: CD11/CD18 integrins and intercellular adhesion molecules. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1997;9:643–650. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(97)80117-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Plow EF, Haas TA, Zhang L, Loftus J, Smith JW. Ligand binding to integrins. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21785–21788. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R000003200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muller WA. Leukocyte-endothelial cell interactions in the inflammatory response. Lab Invest. 2002;82:521–533. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Adhikari A, Xu M, Chen ZJ. Ubiquitin-mediated activation of TAK1 and IKK. Oncogene. 2007;26:3214–3226. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hsu H, Shu HB, Pan MG, Goeddel DV. TRADD-TRAF2 and TRADD-FADD interactions define two distinct TNF receptor 1 signal transduction pathways. Cell. 1996;84:299–308. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80984-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park YC, Ye H, Hsia C, Segal D, Rich RL, Liou HC, Myszka DG, Wu H. A novel mechanism of TRAF signaling revealed by structural and functional analyses of the TRADD-TRAF2 interaction. Cell. 2000;101:777–787. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80889-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liu T, Zhang L, Joo D, Sun S-C. Nf-κb signaling in inflammation. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2017;2:17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fan Y, Yu Y, Shi Y, Sun W, Xie M, Ge N, Mao R, Chang A, Xu G, Schneider MD, et al. Lysine 63-linked polyubiquitination of TAK1 at lysine 158 is required for tumor necrosis factor alpha- and interleukin-1beta-induced IKK/NF-kappaB and JNK/AP-1 activation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:5347–5360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.076976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sorrentino A, Thakur N, Grimsby S, Marcusson A, von Bulow V, Schuster N, Zhang S, Heldin CH, Landström M. The type I TGF-beta receptor engages TRAF6 to activate TAK1 in a receptor kinase-independent manner. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1199–1207. doi: 10.1038/ncb1780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu QS, Robinson LJ, Roginskaya V, Corey SJ. G-CSF-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of Gab2 is Lyn kinase dependent and associated with enhanced Akt and differentiative, not proliferative, responses. Blood. 2004;103:3305–3312. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Angelini DJ, Hyun S-W, Grigoryev DN, Garg P, Gong P, Singh IS, Passaniti A, Hasday JD, Goldblum SE. Tnf-α increases tyrosine phosphorylation of vascular endothelial cadherin and opens the paracellular pathway through fyn activation in human lung endothelia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;291:L1232–L1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]