Abstract

Introduction

Approximately 5-10% of strokes occur in adults of less than 45 years of age. The rising prevalence of stroke risk factors may increase stroke rates in young adults (YA). We aimed to compare risk factors and outcomes of acute ischemic stroke (AIS) among YA.

Methods

Adult hospitalizations for AIS and concurrent risk factors were found in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample database. Weighted analysis using chi-square and multivariable survey logistic regression was performed to evaluate AIS-related outcomes and risk factors among YA (18-45 years) and older patients.

Results

A total of 4,224,924 AIS hospitalizations were identified from 2003 to 2014, out of which 198,378 (4.7%) were YA. Prevalence trend of YA with AIS showed incremental pattern over time (2003: 4.36% to 2014: 4.7%; pTrend<0.0001). In regression analysis, the risk factors associated with AIS in YA were obesity (adjusted odds ratio {aOR}: 2.26; p<0.0001), drug abuse (aOR: 2.56; p<0.0001), history of smoking (aOR: 1.20; p<0.0001), infective endocarditis (aOR: 2.08; p<0.0001), cardiomyopathy (aOR: 2.11; p<0.0001), rheumatic fever (aOR: 4.27; p=0.0014), atrial septal disease (aOR: 2.46; p<0.0001), ventricular septal disease (aOR: 4.99; p<0.0001), HIV infection (aOR: 4.36; p<0.0001), brain tumors (aOR: 7.89; p<0.0001), epilepsy (aOR: 1.43; p<0.0001), end stage renal disease (aOR: 2.19; p<0.0001), systemic lupus erythematous (aOR: 3.76; p<0.0001), polymyositis (aOR: 2.72; p=0.0105), ankylosis spondylosis (aOR: 2.42; p=0.0082), hypercoagulable state (aOR: 4.03; p<0.0001), polyarteritis nodosa (aOR: 5.65; p=0.0004), and fibromuscular dysplasia (aOR: 2.83; p<0.0001).

Conclusion

There is an increasing trend in AIS prevalence over time among YA. Both traditional and non-traditional risk factors suggest that greater awareness is needed, with prevention strategies for AIS among young adults.

Keywords: acute ischemic stroke, risk factors , young adults, nationwide inpatient sample (nis), ischemic cerebrovascular disease, hypercoagulable state, end stage renal disease, hiv, epilepsy, obesity

Introduction

Stroke is the second leading cause of death globally, and although it is most common in the elderly, a significant number of young adults (YA) suffer from it every year [1,2]. The risk of stroke increases with age, but can occur at any age. In 2009, 34% of people hospitalized for stroke were less than 65 years old [3]. Approximately 5-10% of strokes occur in adults <45 years of age [4-8]. Despite considerable improvements in primary prevention, diagnostic workup, and treatment, stroke still remains a major cause of morbidity, serious physical and cognitive long-term disability, and loss in work-related productivity especially when it occurs in the younger population [9,10].

In a systematic review of stroke incidence in YA, the proportion of ischemic strokes ranged between 21.0% and 77.9% in patients under 45 years of age with first-ever stroke [11]. There were 59,077 deaths in YA in the United States from 1989 through 2009 due to stroke, contributing to 2868 deaths per year on average with an average annual mortality rate among YA being 0.93 per 100,000 persons for intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), 1.1 per 100,000 persons for subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH), and 0.70 per 100,000 persons for ischemic stroke [12]. In a single-center study comparing characteristics of stroke between younger and older patients, there were significant differences in risk factors, etiology, and distribution of sex between these groups [13]. Edwards et al. from the Canadian Institute for Health Information Discharge Abstract Database (n = 26,366) described a higher hazard for recurrent stroke at one year (hazard ratio {HR}: 6.8), at five years (HR: 5.1), stroke survivors had higher mortality and morbidity, and patients with TIA had a higher prevalence (31.5%; 1789/5677) of an adverse event within the first five years [14].

Our study aimed to provide estimates on the burden of stroke among YA in the United States. We performed a comprehensive assessment to compare traditional and non-traditional risk factors and ischemic stroke-related mortality, morbidity, discharge disposition, disability, and risk of death among young adults (YA: 18-45 years) vs. old adults (OA: >45 years) between 2003 and 2014.

Materials and methods

Data were obtained from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality's Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) files from January 2003 to December 2014. The NIS is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient care database in the United States and contains discharge-level data provided by states that participate in the HCUP (including a total of 46 states in 2011). This administrative dataset contains data on approximately eight million hospitalizations in 1000 hospitals that were chosen to approximate a 20% stratified sample of all US community hospitals, representing more than 95% of the national population. Discharge weights are provided for each patient discharge record, which helps to obtain national estimates. Each hospitalization is treated as an individual entry in the database and is coded with one principal diagnosis, up to 24 secondary diagnoses, and 15 procedural diagnoses associated with that stay (detailed information on NIS is available at http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nis/nisdde.jsp). The NIS is a de-identified database, so informed consent or IRB approval was not needed for the study. The HCUP Data Use Agreement and training (HCUP-4Q28K90CU) for the data utilized in this study were obtained.

Study population

We used the ninth revision of the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) codes to identify adult patients admitted with a primary diagnosis of AIS (ICD-9-CM codes 433.01, 433.11, 433.21, 433.31, 433.81, 433.91, 434.01, 434.11, 434.91). These codes have been previously validated and are 35% sensitive, 99% specific, with 96% positive predictive value (PPV), and 79% negative predictive value for the diagnosis of ischemic stroke [15]. We used ICD-9-CM codes to identify traditional and non-traditional risk factors. Table 1 lists all ICD-9-CM codes that were used for this study. Age <18 years and admissions with missing data for age, sex, and race were excluded.

Table 1. ICD-9-CM codes used in this analysis.

ICD9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; IHD: ischemic heart diseases; ASD: atrial septal disease; VSD: ventricular septal disease; PDA: patent ductus arteriosus; SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus; CNS: central nervous system; DM: diabetes mellitus; A-fib: atrial fibrillation; Hb SS: homozygous SCD patients; SC/HbC: sickle cell-hemoglobin C; SCD: sickle cell disease

| Disease | ICD9-CM codes nationwide inpatient sample |

| Infective endocarditis | 421.0 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 425.1 Primary CM, 425.20 Obscure cardiomyopathy of Africa, 425.30 Endocardial fibroelastosis, 425.40 Other primary cardiomyopathies, 425.50 Alcoholic cardiomyopathy, 425.70 Nutritional and metabolic cardiomyopathy, 425.80-429.83 Cardiomyopathy in other diseases classified Takotsubo, 425.90, 674.5, 414.8 Secondary cardiomyopathy, unspecified Peripartum cardiomyopathy Ischemic |

| Rheumatic fever | 390, 391.9, 391.1, 391.8, 391.2, 391.0 |

| IHD | 410.00, 410.01, 410.02, 410.10, 410.11, 410.12, 410.20, 410.21, 410.22, 410.30, 410.31, 410.32, 410.40, 410.41, 410.42, 410.50, 410.51, 410.52, 410.60, 410.61, 410.62, 410.70, 410.71, 410.72, 410.80, 410.81, 410.82, 410.90, 410.91, 410.92, CAD: 414.00-414.07, old MI - 412 |

| ASD | 745.5, 745.61 |

| VSD | 745.4 |

| PDA | 747.0 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 714.0, 714.1, 714.2 |

| Ankylosing spondylitis | 720.0 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 696.0 |

| SLE | 710.0 |

| Scleroderma | 701.0 |

| Sjogren’s syndrome | 710.2 |

| Polymyositis | 710.4 |

| Dermatomyositis | 710.3 |

| Hypercoagulable disorders (factor V Leiden mutation, antiphospholipid antibodies, protein S deficiency, antithrombin III deficiency | 286.53, 289.81, 795.79 |

| Polycythemia rubra | 238.4 |

| Pneumonia | Viral - 480.0, 480.1, 480.2, 480.3, 480.8, 480.9, Pneumococcal- 481 Other - bacterial pneumonia- 482.0, 482.1, 482.2, 482.3, Strep - 482.30, 482.31, 482.32, 482.39, Staph - 482.40, 482.41, 482.42, 482.49, Other specified bacteria - 482.81, 482.82, 482.83, 482.84, 482.89, 482.9, 483.0, 483.1, 483.8 486 |

| Urinary tract infection | 599.0 |

| TB meningitis | 013.00 |

| Tuberculoma | 013.20 |

| Neurosyphilis | 094.0 Tabes dorsalis, 094.1 General paresis, 094.2 Syphilitic meningitis, 094.3 Asymptomatic neurosyphilis, 094.81 Syphilitic encephalitis, 094.82 Syphilitic parkinsonism, 094.83 Syphilitic disseminated, 094.84 Syphilitic optic atrophy, 094.85 Syphilitic retrobulbar neuritis, 094.86 Syphilitic acoustic neuritis, 094.87 Syphilitic ruptured cerebral aneurysm, 094.89 Other specified neurosyphilis, 094.9 Neurosyphilis, unspecified |

| Cryptococcal meningitis | 321.0 |

| Seizure | 345.01 generalized nonconvulsive epilepsy 345.0 nonconvulsive/absence 345.1 Gen convulsion 345.2 Petit mal status 345.3 Grand mal status 345.4 Partial epi w impairment of consciousness 345.5 partial epi w/o impairment of cons 780.3 Convulsion excluding epileptic convulsion & of newborn 780.39 other convulsion 780.31 febrile convulsion 345.6 infantile spasms 345.81 Intractable epilepsy |

| CNS tumors | 191.0, Cerebrum, except lobes and ventricles 191.1, Frontal lobe. 191.2, Temporal lobe 191.3, Parietal lobe. 191.4, Occipital lobe. 191.5, Ventricles, 191.6, Cerebellum, 191.7, Brain stem. 191.8, Other parts of brain, 191.9, Brain unspecified and cranial fossa unspecified. |

| AVM brain | 747.81 |

| Moyamoya | 437.5 |

| Giant cell arteritis | 446.5 |

| PAN | 446.0 |

| Takayasu's disease | 446.7 |

| Thromboangiitis obliterans | 443.1 |

| HIV | 042, V08 |

| Fabry's | 272.7 |

| Fibromuscular dysplasia | 447.8 447.3 |

| Sickle cell disease | 282.60, 282.62 Hb SS with crisis 282.61 Hb SS without crisis 282.63 SC/HbC w/o crisis 282.64 SC/HbC w crisis 282.68 other SCD without crisis 282.69 other SCD with crisis 282.41 Sickle cell-thalassemia without crisis 282.42 Sickle cell-thalassemia with crisis |

| Pregnancy | V22.0, V22.1, V22.2, V23.9 |

| Pregnancy-related conditions/complications | Hyperemesis 643.10, 643.11, 643.13 Preterm labor 644.00, 644.03, 644.10, 644.13, 644.20, 644.21 Antepartum hemorrhage, 641.10, 641.11, 641.13, 641.30, 641.31, 641.33, 641.80, 641.83, 641.90, 641.93 Preeclampsia and gestational hypertension 642.40, 642.41, 642.42, 642.43, 642.44, 642.50, 642.51, 642.52, 642.53, 642.54, 642.60, 642.61, 642.62, 642.63, 642.64, 642.70, 642.71, 642.72, 642.73, 642.74, 642.90, 642.91, 642.92, 642.93, 642.94, diabetes - 648.00, 648.01, 648.02, 648.03, 648.04, 648.80, 648.81, 648.82, 648.83, 648.84, Postpartum hemorrhage 666.00, 666.02, 666.04, 666.10, 666.12, 666.14, 666.20, 666.22, 666.24, 666.30, 666.32, 666.34, Puerperial septic thrombophlebitis: 670.30, 670.32, 670.34 |

| Alcohol | 303.00, 303.01, 303.02, 303.03 303.90, 303.91, 303.92, 303.93 305.0 |

| substance abuse | 305.90, 305.20, 305.21, 305.22, 305.23, 305.30, 305.31, 305.32, 305.33, 305.40, 305.41, 305.42, 305.43 305.50, 305.51, 305.52, 305.53 305.60, 305.61, 305.62, 305.63 305.70, 305.71, 305.72, 305.73 305.80, 305.81, 305.82, 305.83 305.90, 305.91, 305.392, 305.93 |

| Smoking | 305.1, V15.82 |

| Hypertension | 401.0, 401.9, Complications - 402.00, 402.10, 402.90, 403.00, 403.10, 403.90, 404.00, 404.10, 404.90, 404.01, 404.11, 404.91, 404.93, 404.13, 404.93 |

| DM | 250.00, 250.01, 250.02, 250.03, 250.10, 250.11, 250.12, 250.13, 250.20, 250.21, 250.22, 250.23, 250.30, 250.31, 250.32, 250.33, 250.40, 250.41, 250.42, 250.43, 250.50, 250.51, 250.52, 250.53, 250.60, 250.61, 250.62, 250.63, 250.70, 250.71, 250.72, 250.73, |

| A.fib | 427.31 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 272.0, 272.1, 272.2 |

Patient and hospital characteristics

Patient characteristics of interest were age, sex, race, insurance status, and concomitant diagnoses as defined above. The race was defined by white (referent), African American, Hispanic, Asian or Pacific Islander, and Native American. Insurance status was defined by Medicare (referent), Medicaid, Private Insurance, and Other/Self-pay/No charge. We defined the severity of co-morbid conditions using Deyo's modification of the Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) (Table 2).

Table 2. Deyo’s modification of CCI.

ICD9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; CCI: Charlson Comorbidity Index

| Condition | ICD-9-CM codes | Charlson score |

| Myocardial infarction | 410-410.9 | 1 |

| Congestive heart failure | 428-428.9 | 1 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 433.9, 441-441.9, 785.4, V43.4 | 1 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 430-438 | 1 |

| Dementia | 290-290.9 | 1 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 490-496, 500-505, 506.4 | 1 |

| Rheumatologic disease | 710.0, 710.1, 710.4, 714.0-714.2, 714.81, 725 | 1 |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 531-534.9 | 1 |

| Mild liver disease | 571.2, 571.5, 571.6, 571.4 –571.49 | 1 |

| Diabetes | 250-250.3, 250.7 | 1 |

| Diabetes with chronic complications | 250.4-250.6 | 2 |

| Hemiplegia or paraplegia | 344.1, 342-342.9 | 2 |

| Renal disease | 582-582.9, 583-583.7, 585, 586, 588-588.9 | 2 |

| Any malignancy including leukemia and lymphoma | 140-172.9, 174-195.8, 200-208.9 | 2 |

| Moderate or severe liver disease | 572.2-572.8 | 3 |

| Metastatic solid tumor | 196-199.1 | 6 |

| AIDS | 042-044.9 | 6 |

Outcomes

Our primary interest was to compare the prevalence of traditional and non-traditional risk factors of AIS among YA (18-45 years) and OA (>45 years). The secondary interest was to compare outcomes of AIS in YA and OA. The outcomes were all-cause mortality during hospitalization, morbidity (length of stay >10 days {>90th percentile of AIS hospitalization} and discharge to non-home {transfer to short-term hospital, skilled nursing facility, intermediate care facility, or home health care}), discharge disposition (discharge to home vs. non-home), All Patients Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (APR-DRG) risk of mortality, APR-DRG severity of illness (disability), length of stay (LoS), and cost of hospitalization [16]. APR-DRGs were assigned using software developed by 3M Health Information Systems, where score 1 indicates minor loss of function, 2-moderate, 3-major, 4-extreme loss of function or likelihood of death. APR-DRG coding system used in this study to assess the risk of mortality and severity of illness is externally validated. It is a reliable method with accurate and consistent results and is widely used by hospitals, consumers, payers, and regulators [17,18].

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using the weighted survey methods in Statistical Analysis System (SAS) Version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Weighted values of patient-level observations were generated to produce a nationally representative estimate of the entire US population of hospitalized patients. Univariate analysis of differences between categorical variables (including demographics, comorbidities, risk factors, and concurrent conditions) and outcomes was tested using the chi-square test and analysis of differences between continuous variables (LoS and cost of hospitalization) was tested using unpaired student's t-test. Among AIS hospitalizations, the prevalence and mortality trends from 2003 to 2014 for YA and OA were tested and plotted using the Jonckheere trend test.

In order to examine the relationship of age groups (YA vs. OA) with AIS-related risk factors and the relationship of age groups with AIS-related outcomes, we used mixed-effects multivariable survey logistic regression models. The models were weighted and adjusted for demographics (age, sex, race), patient-level hospitalization variables (admission day, primary payer, admission type, median household income category), hospital-level variables (hospital region, teaching versus nonteaching hospital, hospital bed size), comorbidities, traditional and non-traditional risk factors, and CCI in order to estimate the adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Common conditions covered as risk factors and CCIs were adjusted only once in order to avoid over-adjustment. For each model, the c-index was calculated. All statistical tests used were two-sided, and p<0.05 was deemed statistically significant. No statistical power calculation was conducted prior to the study.

Results

We have described prevalence trends and characteristics of AIS. We have also compared demographics, patient and hospital characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes of AIS amongst YA and OA below.

Disease hospitalizations

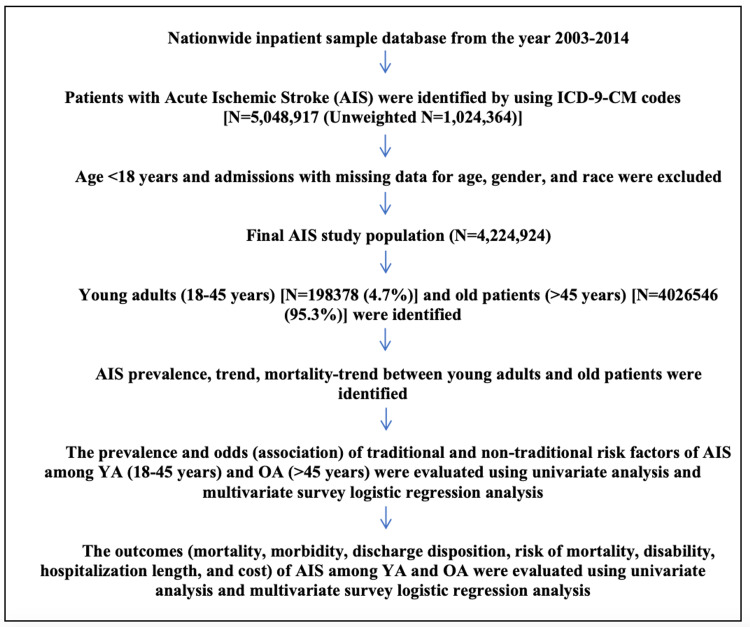

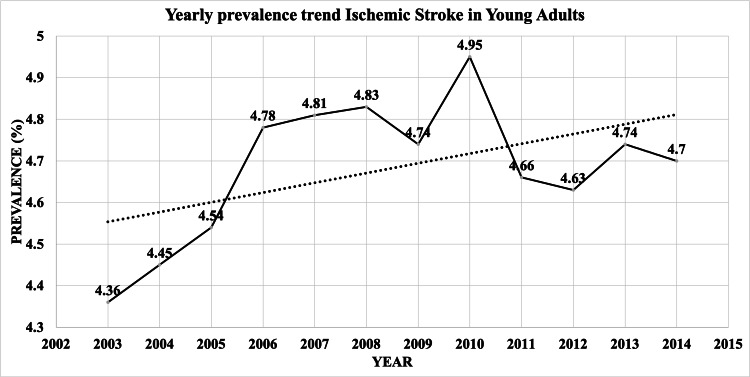

There were 4,224,924 hospitalizations due to AIS from 2003 to 2014 after excluding patients with age <18 years and admissions with missing data for age, sex, and race (Figure 1). Out of 4,224,924 AIS hospitalizations, 198,378 (4.7%) were YA (≤45 years) and 4,026,546 (95.3%) were OA. As shown in Figure 2, the percentage of YA among AIS hospitalizations increased from 4.36% in 2003 to 4.7% in 2014. (pTrend<0.0001)

Figure 1. Flowchart detailing cohort selection and modeling analysis of outcomes.

ICD9-CM: International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification; AIS: acute ischemic stroke; YA: young adults; OA: old adults

Figure 2. Yearly prevalence trend of AIS in Young adults .

AIS: acute ischemic stroke

Demographics, patient and hospital characteristics, and comorbidities

There was a higher proportion of females among OA with AIS than YA (53.1% vs. 48.5%; p<0.0001) (Table 3). There was a higher proportion of African Americans (29.95% vs. 16.14%; p<0.0001) and Hispanics (12.17% vs. 7.35%; p<0.0001) among YA. Utilization of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (6.32% vs. 4.34%; p<0.0001) and endovascular mechanical thrombectomy (1.22% vs. 0.58%; p<0.0001) were higher amongst YA with AIS compared to OA with AIS. OA with AIS had a higher prevalence of current long-term use of aspirin therapy compared to YA (8.79% vs. 5.12%; p<0.0001). Several co-morbidities like chronic blood loss anemia (0.7% vs. 0.45%; p<0.0001), liver disease (1.34% vs. 1.06%; p<0.0001), paralysis (5.48% vs. 3.7%; p<0.0001), psychosis (4.57% vs. 2.91%; p<0.0001) and chronic neurologic disorders (0.88% vs. 0.48%; p<0.0001) were higher among YA than OA.

Table 3. Characteristics of AIS hospitalizations stratified by age group .

Percentage in brackets are column % indicates the direct comparison between young adults vs. older adults among patients with AIS.

*This represents a quartile classification of the estimated median household income of residents in the patient's ZIP code.

**Bedsize of hospital indicates the number of hospital beds which varies depends on hospital location (rural/urban), teaching status (teaching/non-teaching), and region (Northeast/Midwest/Southern/Western).

CMV: cytomegalovirus; CNS: central nervous system; AIS: acute ischemic stroke

| Young adults (18-45 years) | Older adults (>45 years) | Total | p-Value | |

| AIS hospitalizations (%) | 198,378 (4.7) | 4,026,546 (95.3) | 4,224,924 (100) | |

| Demographics of patients | ||||

| Gender (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Female | 96,233 (48.51) | 2,138,020 (53.1) | 2,234,253 (52.88) | |

| Male | 102,145 (51.49) | 1,888,457 (46.9) | 1,990,602 (47.12) | |

| Race (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| White | 104,485 (54.54) | 2,881,643 (73.4) | 2,986,128 (72.53) | |

| African American | 57,382 (29.95) | 633,708 (16.14) | 691,090 (16.78) | |

| Hispanic | 23,310 (12.17) | 288,462 (7.35) | 311,772 (7.57) | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 5158 (2.69) | 103,386 (2.63) | 108,544 (2.64) | |

| Native American | 1233 (0.64) | 18,600 (0.47) | 19,833 (0.48) | |

| Characteristics of patients | ||||

| Median household income category for patient's ZIP code (%)* | <0.0001 | |||

| 0-25th percentile | 66,609 (34.44) | 1,175,425 (29.82) | 1,242,034 (30.04) | |

| 26-50th percentile | 49,480 (25.58) | 1,015,750 (25.77) | 1,065,230 (25.76) | |

| 51-75th percentile | 42.785 (22.12) | 920,665 (23.36) | 963,450 (23.3) | |

| 76-100th percentile | 34,548 (17.86) | 829,372 (21.04) | 863,920 (20.89) | |

| Primary payer (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Medicare | 18,906 (9.56) | 2,804,887 (69.78) | 2,823,793 (66.95) | |

| Medicaid | 46,516 (23.52) | 239,588 (5.96) | 286,104 (6.78) | |

| Private insurance | 87,892 (44.44) | 711,337 (17.7) | 799,229 (18.95) | |

| Other/self-pay/no charge | 44,470 (22.48) | 263,983 (6.57) | 308,453 (7.31) | |

| Admission type (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Non- elective | 190,181 (96.06) | 3,833,377 (95.41) | 4,023,557 (95.44) | |

| Elective | 7806 (3.94) | 184,578 (4.59) | 192,384 (4.56) | |

| Admission day (%) | 0.0018 | |||

| Weekday | 148,268 (74.74) | 2,996,820 (74.43) | 3,145,089 (74.44) | |

| Weekend | 50,110 (25.26) | 1,029,725 (25.57) | 1,079,835 (25.56) | |

| Characteristics of hospitals | ||||

| Bedsize of hospital (%)** | <0.0001 | |||

| Small | 17,009 (8.63) | 481,564 (12.01) | 498,573 (11.85) | |

| Medium | 47,805 (24.26) | 1,030,840 (25.71) | 1,078,644 (25.64) | |

| Large | 132,226 (67.11) | 2,497,587 (62.28) | 2,629,813 (62.51) | |

| Hospital location & teaching status (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Rural | 14,062 (7.14) | 481,027 (12) | 495,089 (11.77) | |

| Urban non-teaching | 72,265 (36.68) | 1,710,411 (42.65) | 1,782,676 (42.37) | |

| Urban teaching | 110,712 (56.19) | 1,818,553 (45.35) | 1,929,265 (45.86) | |

| Hospital region (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Northeast | 37,829 (19.07) | 858,527 (21.32) | 896,356 (21.22) | |

| Midwest | 32,990 (16.63) | 697,196 (17.31) | 730,186 (17.28) | |

| South | 90,734 (45.74) | 1,719,665 (42.71) | 1,810,399 (42.85) | |

| West | 36,826 (18.56) | 751,158 (18.66) | 787,983 (18.65) | |

| Stroke related medications (%) | ||||

| Current long-term use of Aspirin therapy | 10,165 (5.12) | 353,886 (8.79) | 364,051 (8.62) | <0.0001 |

| Use of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA) | 12,534 (6.32) | 174,855 (4.34) | 187,388 (4.44) | <0.0001 |

| Use of endovascular mechanical thrombectomy | 2413 (1.22) | 23,411 (0.58) | 25,824 (0.61) | <0.0001 |

| Comorbidities of patients (%) | ||||

| Deficiency anemias | 19,652 (9.94) | 467,108 (11.65) | 486,759 (11.57) | <0.0001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular diseases | 5321 (2.69) | 94,806 (2.37) | 100,127 (2.38) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic blood loss anemia | 1381 (0.7) | 17,913 (0.45) | 19294.6 (0.46) | <0.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 12,425 (6.28) | 578,171 (14.43) | 590,596 (14.04) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 17,442 (8.82) | 602,466 (15.03) | 619,908 (14.74) | <0.0001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 8535 (4.32) | 514,168 (12.83) | 522,703 (12.43) | <0.0001 |

| Liver disease | 2654 (1.34) | 42,508 (1.06) | 45,162 (1.07) | <0.0001 |

| Lymphoma | 632 (0.32) | 20,836 (0.52) | 21,468 (0.51) | <0.0001 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 30,624 (15.49) | 800,738 (19.98) | 831,362 (19.77) | <0.0001 |

| Metastatic cancer | 1116 (0.56) | 58,488 (1.46) | 59,604 (1.42) | <0.0001 |

| Paralysis | 10,826 (5.48) | 148,241 (3.7) | 159,067 (3.78) | <0.0001 |

| Psychoses | 9036 (4.57) | 116,737 (2.91) | 125,774 (2.99) | <0.0001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease excluding bleeding | 25 (0.01) | 1416 (0.04) | 1441 (0.03) | <0.0001 |

| Valvular disease | 13,434 (6.8) | 413,319 (10.31) | 426,752 (10.15) | <0.0001 |

| Weight loss | 3289 (1.66) | 125,944 (3.14) | 129,233 (3.07) | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 3317 (1.68) | 115,370 (2.88) | 118,687 (2.82) | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 14,352 (7.26) | 359,101 (8.96) | 373,453 (8.88) | <0.0001 |

| Coagulopathy | 5614 (2.84) | 110,457 (2.76) | 116,071 (2.76) | 0.0267 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 884 (0.45) | 70,634 (1.76) | 71,518 (1.7) | <0.0001 |

| Depression | 18,818 (9.52) | 370,045 (9.23) | 388,863 (9.25) | <0.0001 |

| Other neurological disorders | 1743 (0.88) | 19,275 (0.48) | 21,018 (0.5) | <0.0001 |

| Concurrent conditions or risk factors (%) | ||||

| Diabetes | 49,279 (24.84) | 1,394,654 (34.64) | 1,443,933 (34.18) | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension (combined uncomplicated and complicated) | 109,951 (55.42) | 3,246,458 (80.63) | 3,356,409 (79.44) | <0.0001 |

| Obesity | 31,797 (16.03) | 306,293 (7.61) | 338,091 (8) | <0.0001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 16,298 (8.22) | 435,347 (10.81) | 451,645 (10.69) | <0.0001 |

| Drug abuse/dependence | 21,714 (10.95) | 67,645 (1.68) | 89,359 (2.12) | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence | 13,067 (6.59) | 149,261 (3.71) | 162,328 (3.84) | <0.0001 |

| Past history of smoking | 9262 (4.67) | 379,316 (9.42) | 388,579 (9.2) | <0.0001 |

| Current tobacco dependence | 61,720 (31.11) | 574,046 (14.26) | 635,766 (15.05) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac diseases | 45,679 (23.03) | 1,896,107 (47.09) | 1,941,786 (45.96) | <0.0001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 17,934 (9.04) | 1,147,546 (28.5) | 1,165,481 (27.59) | <0.0001 |

| Infective endocarditis | 965 (0.49) | 6262 (0.16) | 7227 (0.17) | <0.0001 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 5926 (2.99) | 947,502 (23.53) | 953,428 (22.57) | <0.0001 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 10,203 (5.14) | 144,888 (3.6) | 155,091 (3.67) | <0.0001 |

| Rheumatic fever | 50 (0.03) | 368 (0.01) | 418 (0.01) | <0.0001 |

| Rheumatoid heart disease | 3859 (1.95) | 133,365 (3.31) | 137,224 (3.25) | <0.0001 |

| Atrial septal disease | 15,181 (7.65) | 69,403 (1.72) | 84,584 (2) | <0.0001 |

| Ventricular septal disease | 230 (0.12) | 550 (0.01) | 781 (0.02) | <0.0001 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 37 (0.02) | 249 (0.01) | 286 (0.01) | <0.0001 |

| Infectious diseases | 16,980 (8.56) | 626,884 (15.57) | 643,864 (15.24) | <0.0001 |

| Urinary tract infection | 11,209 (5.65) | 509,319 (12.65) | 520,528 (12.32) | <0.0001 |

| HIV infection | 2425 (1.22) | 5679 (0.14) | 8104 (0.19) | <0.0001 |

| Pneumonia | 4179 (2.11) | 144,646 (3.59) | 148,825 (3.52) | <0.0001 |

| Neurosyphilis | 133 (0.07) | 1857 (0.05) | 1989 (0.05) | <0.0001 |

| CNS tuberculosis | 16 (0.01) | 25 (0) | 41 (0) | <0.0001 |

| Meningitis | 75 (0.04) | 276 (0.01) | 352 (0.01) | <0.0001 |

| CMV encephalitis | 57 (0.03) | 202 (0.01) | 259 (0.01) | <0.0001 |

| Toxoplasmosis | <10 | 0 | <10 | <0.0001 |

| CNS lymphoma | <10 | 84 | 94 | 0.0142 |

| Progressive multifocal encephalopathy | 43 (0.02) | 98 | 141 | <0.0001 |

| Non-infective CNS diseases | 30,110 (15.18) | 618,165 (15.35) | 648,274 (15.34) | 0.0355 |

| Brain tumors | 336 (0.17) | 2442 (0.06) | 2778 (0.07) | <0.0001 |

| Epilepsy | 16,641 (8.39) | 235,995 (5.86) | 252,636 (5.98) | <0.0001 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 3165 (1.6) | 67,054 (1.67) | 70,219 (1.66) | 0.0172 |

| Arterial-venous malformation | 576 (0.29) | 3919 (0.1) | 4496 (0.11) | <0.0001 |

| History of transient ischemic attack | 11,304 (5.7) | 338,425 (8.4) | 349,728 (8.28) | <0.0001 |

| Traumatic brain injury | 217 (0.11) | 7861 (0.2) | 8078 (0.19) | <0.0001 |

| Renal diseases | 19,855 (10.01) | 652,927 (16.22) | 672,783 (15.92) | <0.0001 |

| Chronic kidney diseases | 7427 (3.74) | 342,859 (8.51) | 350,286 (8.29) | <0.0001 |

| Acute renal failure | 9328 (4.7) | 279,229 (6.93) | 288,557 (6.83) | <0.0001 |

| End-stage renal disease | 3787 (1.91) | 61,935 (1.54) | 65,722 (1.56) | <0.0001 |

| Connective tissue diseases | 5121 (2.58) | 79,066 (1.96) | 84,187 (1.99) | <0.0001 |

| Systemic lupus erythematous | 3959 (2) | 14,170 (0.35) | 18,129 (0.43) | <0.0001 |

| Scleroderma | 20 (0.01) | 215 (0.01) | 235 (0.01) | 0.0051 |

| Systemic sclerosis | 230 (0.12) | 3995 (0.1) | 4226 (0.1) | 0.0203 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 1022 (0.51) | 59,416 (1.48) | 60,438 (1.43) | <0.0001 |

| Polymyositis | 60 (0.03) | 770 (0.02) | 830 (0.02) | 0.0007 |

| Dermatomyositis | 25 (0.01) | 394 (0.01) | 419 (0.01) | 0.1855 |

| Ankylosis spondylosis | 91 (0.05) | 971 (0.02) | 1063 (0.03) | <0.0001 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 124 (0.06) | 2469 (0.06) | 2593 (0.06) | 0.8566 |

| Coagulopathy | 9792 (4.94) | 34,353 (0.85) | 44,145 (1.04) | <0.0001 |

| Hypercoagulable state | 9057 (4.57) | 22,625 (0.56) | 31,682 (0.75) | <0.0001 |

| Polycythemia vera | 784 (0.4) | 11,921 (0.3) | 12,705 (0.3) | <0.0001 |

| Vasculitis | 222 (0.11) | 6278 (0.16) | 6500 (0.15) | <0.0001 |

| Giant cell arteritis | 30 (0.01) | 5576 (0.14) | 5605 (0.13) | <0.0001 |

| Polyarteritis nodosa | 47 (0.02) | 288 (0.01) | 335 (0.01) | <0.0001 |

| Takayasu disease | 85 (0.04) | 166 (0) | 250 (0.01) | <0.0001 |

| Thromboangiitis obliterans | 66 (0.03) | 248 (0.01) | 314 (0.01) | <0.0001 |

| Amyloidosis | 19 (0.01) | 3957 (0.1) | 3976 (0.09) | <0.0001 |

| Sickle cell disease | 894 (0.45) | 1772 (0.04) | 2666 (0.06) | <0.0001 |

| Moya-moya | 1270 (0.64) | 1020 (0.03) | 2291 (0.05) | <0.0001 |

| Fibromuscular dysplasia | 560 (0.28) | 2957 (0.07) | 3517 (0.08) | <0.0001 |

Primary outcome

The prevalence of obesity (16.03% vs. 7.61%; p<0.0001), drug abuse (10.95% vs. 1.68%; p<0.0001), alcohol abuse (6.59% vs. 3.71%; p<0.0001), tobacco dependence (31.11% vs. 14.26%; p<0.0001), cardiomyopathy (5.14% vs. 3.6%; p<0.0001), atrial septal disease (7.56% vs. 1.72%; p<0.0001), epilepsy (8.39% vs. 5.36%; p<0.0001), and hypercoagulable state (4.57% vs. 0.56%; p<0.0001) were higher among YA in compare to OA.

The OA with AIS had higher prevalence of diabetes (34.64% vs. 24.84%; p<0.0001), hypertension (80.63% vs. 55.42%; p<0.0001), hypercholesterolemia/triglyceridemia (10.81% vs. 8.22%; p<0.0001) history of smoking (9.42% vs. 4.67%; p<0.0001), ischemic heart disease (28.5% vs. 9.04%; p<0.0001), atrial fibrillation (23.53% vs. 2.99%; p<0.0001), rheumatoid heart disease (3.31% vs. 1.95%; p<0.0001), urinary tract infection (12.65% vs. 5.65%; p<0.0001), pneumonia (3.59% vs. 2.11%; p<0.0001), history of transient ischemic attack (8.4% vs. 5.7%; p<0.0001), chronic kidney diseases (8.51% vs. 3.74%; p<0.0001), and acute renal failure (6.93% vs. 4.7%; p<0.0001).

Multivariable regression model derivation for the age-group specific risk factors

Table 4 shows multivariable models evaluating the odds of risk factors of AIS among YA and OA population. The obesity (aOR: 2.26; p<0.0001), drug abuse (aOR: 2.56; p<0.0001), past history of smoking (aOR: 1.20; p<0.0001), infective endocarditis (aOR: 2.08; p<0.0001), cardiomyopathy (aOR: 2.11; p<0.0001), rheumatic fever (aOR: 4.27; p=0.0014), atrial septal disease (aOR: 2.46; p<0.0001), ventricular septal disease (aOR: 4.99; p<0.0001), HIV infection (aOR: 4.36; p<0.0001), brain tumors (aOR: 7.89; p<0.0001), epilepsy (aOR: 1.43; p<0.0001), arterial-venous malformation (aOR: 1.81; p<0.0001), end-stage renal disease (aOR: 2.19; p<0.0001), systemic lupus erythematous (aOR: 3.76; p<0.0001), polymyositis (aOR: 2.72; p=0.0105), ankylosis spondylosis (aOR: 2.42; p=0.0082), hypercoagulable state (aOR: 4.03; p<0.0001), polyarteritis nodosa (aOR: 5.65; p=0.0004), and fibromuscular dysplasia (aOR: 2.83; p<0.0001) were significantly associated with YA population with AIS.

Table 4. Traditional and non-traditional risk factors of AIS among young adults in comparison to old adults .

aOR: adjusted odds ratio; CI: confidence interval; UL: upper limit, LL: lower limit; CNS: central nervous system; AIS: acute ischemic stroke

| Association of risk factors with young adults | Association of risk factors with old adults | |||||

| aOR | 95% CI (LL-UL) | p-Value | aOR | 95% CI (LL-UL) | p-Value | |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | Reference | <0.0001 | Reference | <0.0001 | ||

| Male | 0.89 | 0.87-0.91 | 1.12 | 1.09-1.15 | ||

| Race | ||||||

| White | Reference | <0.0001 | <0.0001 | |||

| African American | 1.53 | 1.48-1.57 | 0.66 | 0.64-0.68 | ||

| Hispanic | 1.47 | 1.42-1.53 | 0.68 | 0.65-0.71 | ||

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 1.08 | 1.00-1.16 | 0.93 | 0.87-1.00 | ||

| Native American | 1.27 | 1.08-1.48 | 0.79 | 0.67-0.93 | ||

| Median household income category for patient's ZIP code | ||||||

| 0-25th percentile | Reference | 0.0002 | Reference | 0.0002 | ||

| 26-50th percentile | 1.05 | 1.02-1.08 | 0.96 | 0.93-0.99 | ||

| 51-75th percentile | 1.01 | 0.98-1.04 | 0.99 | 0.96-1.03 | ||

| 76-100th percentile | 0.97 | 0.93-1.01 | 1.03 | 1.00-1.07 | ||

| Primary Payer | ||||||

| Medicare | Reference | <0.0001 | Reference | <0.0001 | ||

| Medicaid | 15.69 | 14.99-16.42 | 0.06 | 0.06-0.07 | ||

| Private insurance | 11.10 | 10.69-11.53 | 0.06 | 0.09-0.09 | ||

| Other/self-pay/no charge | 13.70 | 13.11-14.32 | 0.07 | 0.07-0.08 | ||

| Admission type | ||||||

| Non-elective | Reference | 0.0003 | Reference | 0.0003 | ||

| Elective | 0.90 | 0.84-0.95 | 1.12 | 1.05-1.19 | ||

| Admission day | ||||||

| Weekday | Reference | 0.1418 | Reference | 0.1418 | ||

| Weekend | 0.98 | 0.95-1.01 | 1.02 | 0.99-1.05 | ||

| Bedsize of hospital | ||||||

| Small | Reference | <0.0001 | Reference | <0.0001 | ||

| Medium | 1.16 | 1.11-1.21 | 0.86 | 0.82-0.90 | ||

| Large | 1.25 | 1.20-1.30 | 0.80 | 0.77-0.78 | ||

| Hospital location & teaching status | ||||||

| Rural | Reference | <0.0001 | Reference | <0.0001 | ||

| Urban non-teaching | 1.16 | 1.11-1.20 | 0.86 | 0.82-0.90 | ||

| Urban teaching | 1.34 | 1.28-1.41 | 0.74 | 0.71-0.78 | ||

| Hospital region | ||||||

| Northeast | Reference | <0.0001 | Reference | <0.0001 | ||

| Midwest | 1.16 | 1.11-1.20 | 0.87 | 0.83-0.90 | ||

| South | 1.12 | 1.09-1.16 | 0.89 | 0.86-0.92 | ||

| West | 1.02 | 0.98-1.06 | 0.98 | 0.94-1.02 | ||

| Concurrent conditions and risk factors | ||||||

| Diabetes | 0.71 | 0.69-0.74 | <0.0001 | 1.40 | 1.36-1.45 | <0.0001 |

| Hypertension | 0.32 | 0.32-0.33 | <0.0001 | 3.09 | 3.01-3.17 | <0.0001 |

| Obesity | 2.26 | 2.18-2.34 | <0.0001 | 0.44 | 0.43-0.46 | <0.0001 |

| Hypercholesterolemia/triglyceridemia | 0.80 | 0.77-0.84 | <0.0001 | 1.24 | 1.19-1.30 | <0.0001 |

| Drug abuse | 2.56 | 2.44-2.68 | <0.0001 | 0.39 | 0.37-0.41 | <0.0001 |

| Alcohol abuse | 0.75 | 0.71-0.78 | <0.0001 | 1.34 | 1.28-1.41 | <0.0001 |

| Past history of smoking | 1.20 | 1.17-1.24 | <0.0001 | 0.83 | 0.81-0.86 | <0.0001 |

| Current tobacco dependence | 0.64 | 0.61-0.67 | <0.0001 | 1.56 | 1.48-1.65 | <0.0001 |

| Ischemic heart disease | 0.46 | 0.44-0.47 | <0.0001 | 2.20 | 2.11-2.28 | <0.0001 |

| Infective endocarditis | 2.08 | 1.67-2.58 | <0.0001 | 0.48 | 0.39-0.60 | <0.0001 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 0.24 | 0.23-0.26 | <0.0001 | 4.18 | 3.93-4.45 | <0.0001 |

| Cardiomyopathy | 2.11 | 1.99-2.24 | <0.0001 | 0.47 | 0.45-0.50 | <0.0001 |

| Rheumatic fever | 4.27 | 1.76-10.36 | 0.0014 | 0.23 | 0.10-0.57 | 0.0014 |

| Rheumatoid heart disease | 0.86 | 0.78-0.95 | 0.0027 | 1.16 | 1.05-1.28 | 0.0027 |

| Atrial septal disease | 2.46 | 2.34-2.58 | <0.0001 | 0.41 | 0.39-0.43 | <0.0001 |

| Ventricular septal disease | 4.99 | 3.09-8.05 | <0.0001 | 0.20 | 0.12-0.32 | <0.0001 |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | 1.37 | 0.59-3.19 | 0.4681 | 0.73 | 0.31-1.70 | 0.4681 |

| Urinary tract infection | 0.64 | 0.61-0.67 | <0.0001 | 1.56 | 1.49-1.64 | <0.0001 |

| HIV infection | 4.36 | 3.62-5.26 | <0.0001 | 0.23 | 0.19-0.28 | <0.0001 |

| Pneumonia | 0.80 | 0.73-0.87 | <0.0001 | 1.26 | 1.16-1.37 | <0.0001 |

| Neurosyphilis | 0.62 | 0.38-1.00 | 0.0487 | 1.62 | 1.00-2.60 | 0.0487 |

| Meningitis | 1.93 | 0.84-4.45 | 0.1223 | 0.52 | 0.23-1.19 | 0.1223 |

| CNS lymphoma | 1.55 | 0.29-8.42 | 0.6096 | 0.64 | 0.12-3.49 | 0.6096 |

| Brain tumors | 7.89 | 5.48-11.36 | <0.0001 | 0.13 | 0.09-0.18 | <0.0001 |

| Epilepsy | 1.43 | 1.37-1.50 | <0.0001 | 0.70 | 0.67-0.73 | <0.0001 |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 0.98 | 0.89-1.08 | 0.6444 | 1.02 | 0.93-1.13 | 0.6444 |

| Arterial-venous malformation | 1.81 | 1.43-2.28 | <0.0001 | 0.55 | 0.44-0.70 | <0.0001 |

| History of transient ischemic attack | 0.82 | 0.78-0.87 | <0.0001 | 1.21 | 1.16-1.28 | <0.0001 |

| Traumatic brain injury | 0.70 | 0.50-0.97 | 0.0328 | 1.43 | 1.03-2.00 | 0.0328 |

| Chronic kidney diseases | 0.63 | 0.57-0.71 | <0.0001 | 1.58 | 1.42-1.75 | <0.0001 |

| Acute renal failure | 0.84 | 0.79-0.89 | <0.0001 | 1.19 | 1.12-1.26 | <0.0001 |

| End-stage renal disease | 2.19 | 1.92-2.51 | <0.0001 | 0.46 | 0.40-0.52 | <0.0001 |

| Systemic lupus erythematous | 3.76 | 2.99-4.73 | <0.0001 | 0.27 | 0.21-0.34 | <0.0001 |

| Scleroderma | 2.25 | 0.50-10.18 | 0.2937 | 0.45 | 0.10-2.02 | 0.2937 |

| Systemic sclerosis | 1.18 | 0.79-1.77 | 0.4183 | 0.85 | 0.57-1.27 | 0.4183 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 0.44 | 0.34-0.56 | <0.0001 | 2.29 | 1.79-2.93 | <0.0001 |

| Polymyositis | 2.72 | 1.26-4.69 | 0.0105 | 0.37 | 0.17-0.79 | 0.0105 |

| Dermatomyositis | 1.06 | 0.39-2.91 | 0.9061 | 0.94 | 0.34-2.58 | 0.9061 |

| Ankylosis spondylosis | 2.42 | 1.26-4.69 | 0.0082 | 0.41 | 0.21-0.80 | 0.0082 |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 1.10 | 0.69-1.76 | 0.6998 | 0.91 | 0.57-1.46 | 0.6998 |

| Hypercoagulable state | 4.03 | 3.72-4.36 | <0.0001 | 0.25 | 0.23-0.27 | <0.0001 |

| Polycythemia vera | 1.10 | 0.91-1.33 | 0.3335 | 0.91 | 0.75-1.10 | 0.3335 |

| Giant cell arteritis | 0.24 | 0.11-0.54 | 0.0004 | 4.11 | 1.87-9.03 | 0.0004 |

| Polyarteritis nodosa | 5.65 | 2.16-14.81 | 0.0004 | 0.18 | 0.07-0.46 | 0.0004 |

| Thromboangiitis obliterans | 1.86 | 0.83-4.15 | 0.1304 | 0.54 | 0.24-1.20 | 0.1304 |

| Amyloidosis | 0.11 | 0.04-0.31 | <0.0001 | 9.09 | 3.25-25.39 | <0.0001 |

| Fibromuscular dysplasia | 2.83 | 2.20-3.65 | <0.0001 | 0.35 | 0.27-0.45 | <0.0001 |

| Comorbidities of patients | ||||||

| Deficiency anemias | 1.15 | 1.11-1.20 | <0.0001 | 0.87 | 0.83-0.90 | <0.0001 |

| Rheumatoid arthritis/collagen vascular diseases | 0.96 | 0.77-1.19 | 0.6861 | 1.05 | 0.84-1.30 | 0.6861 |

| Chronic blood loss anemia | 1.82 | 1.56-2.13 | <0.0001 | 0.55 | 0.47-0.64 | <0.0001 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.86 | 0.81-0.91 | <0.0001 | 1.17 | 1.11-1.23 | <0.0001 |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 0.73 | 0.70-0.76 | <0.0001 | 1.37 | 1.32-1.44 | <0.0001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 0.55 | 0.52-0.58 | <0.0001 | 1.83 | 1.73-1.93 | <0.0001 |

| Liver disease | 0.76 | 0.68-0.85 | <0.0001 | 1.32 | 1.18-1.47 | <0.0001 |

| Lymphoma | 0.81 | 0.65-0.99 | 0.0410 | 1.24 | 1.01-1.53 | 0.0410 |

| Fluid and electrolyte disorders | 0.91 | 0.88-0.95 | <0.0001 | 1.09 | 1.06-1.13 | <0.0001 |

| Metastatic cancer | 0.38 | 0.32-0.45 | <0.0001 | 2.63 | 2.23-3.12 | <0.0001 |

| Paralysis | 1.45 | 1.36-1.53 | <0.0001 | 0.69 | 0.65-0.73 | <0.0001 |

| Psychoses | 1.48 | 1.39-1.57 | <0.0001 | 0.68 | 0.64-0.72 | <0.0001 |

| Peptic ulcer disease excluding bleeding | 0.43 | 0.16-1.17 | 0.0984 | 2.35 | 0.85-6.45 | 0.0984 |

| Valvular disease | 1.08 | 1.02-1.14 | 0.0090 | 0.93 | 0.88-0.98 | 0.0090 |

| Weight loss | 0.65 | 0.59-0.71 | <0.0001 | 1.55 | 1.41-1.70 | <0.0001 |

| Pulmonary circulation disorders | 0.90 | 0.82-0.99 | 0.0273 | 1.11 | 1.01-1.23 | 0.0273 |

| Coagulopathy | 1.05 | 0.97-1.13 | 0.2226 | 0.95 | 0.88-1.03 | 0.2226 |

| Solid tumor without metastasis | 0.22 | 0.18-0.26 | <0.0001 | 4.65 | 3.81-5.68 | <0.0001 |

| Depression | 1.14 | 1.09-1.19 | <0.0001 | 0.88 | 0.84-0.92 | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1.18 | 1.13-1.24 | <0.0001 | 0.84 | 0.81-0.88 | <0.0001 |

| Other neurological disorders | 1.25 | 1.08-1.44 | 0.0028 | 0.80 | 0.69-0.93 | 0.0028 |

| Deyo-Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) | 0.94 | 0.93-0.95 | <0.0001 | 1.06 | 1.05-1.08 | <0.0001 |

| c-Index | 0.898 | 0.898 | ||||

The odds of having diabetes (aOR: 1.40; p<0.0001), hypertension (aOR: 3.09; p<0.0001), hypercholesterolemia/triglyceridemia (aOR: 1.24; p<0.0001), alcohol abuse (aOR: 1.34; p<0.0001), current tobacco dependence (aOR: 1.56; p<0.0001), ischemic heart disease (aOR: 2.20; p<0.0001), atrial fibrillation (aOR: 4.18; p<0.0001), rheumatoid heart disease (aOR: 1.16; p=0.0027), urinary tract infection (aOR: 1.56; p<0.0001), pneumonia (aOR: 1.26; p<0.0001), history of transient ischemic attack (aOR: 1.21; p<0.0001), traumatic brain injury (aOR: 1.43; p=0.0328), chronic kidney diseases (aOR: 1.58; p<0.0001), acute renal failure (aOR: 1.19; p<0.0001), rheumatoid arthritis (aOR: 2.29; p<0.0001), giant cell arteritis (aOR: 4.11; p=0.0004), amyloidosis (aOR: 9.09; p<0.0001), solid tumor without metastasis (aOR: 4.65; p<0.0001) and with metastasis (aOR: 2.63; p<0.0001) were significantly higher among OA patients admitted with AIS. The c statistic was 0.898 (>0.5) which indicate good models.

Secondary outcomes

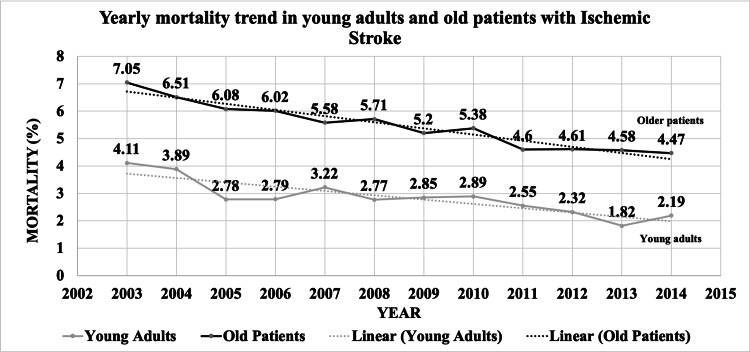

Table 5 includes outcomes of AIS hospitalizations, comparing YA to OA. The all-cause in-hospital mortality (2.73% vs. 5.33; p<0.0001), morbidity (7.15% vs. 7.73; p<0.0001), major/extreme loss of function (30.7% vs. 37.21%; p<0.0001), and major/extreme likelihood of death (13.43% vs. 21.62%; p<0.0001) were lower among YA than OA AIS hospitalizations. YA AIS hospitalizations had a higher prevalence of discharge to home (64.59% vs. 36.15%; p<0.0001) than OA. The trend of all-cause in-hospital mortality in YA decreased from 4.11% in 2003 to 2.19% in 2014 (pTrend<0.0001) and decreased from 7.05% in 2003 to 4.47% in 2014 (P-Trend<0.0001) in OA AIS hospitalizations (Figure 3). Mean length of stay (5.6 days vs. 5.4 days; p<0.0001) and total cost of hospitalization were higher ($47,365 vs. $37,669; p<0.0001) in YA AIS hospitalizations than OA AIS hospitalizations (Table 5).

Table 5. Univariate analysis of outcomes among young vs. old adults with AIS hospitalizations.

Percentage in brackets are column % indicates the direct comparison between YA vs. old patients among patients with AIS.

*Morbidity = length of stay >10 days (>90th percentile of AIS hospitalization) and discharge to non-home (transfer to short-term hospital, skilled nursing facility, intermediate care facility, or home health care).

APR-DRG: All Patients Refined Diagnosis Related Groups; SNF: skilled nursing facility; ICF: intermediate care facility; SE: standard error; AIS: acute ischemic stroke

| Acute ischemic stroke hospitalizations | ||||

| Young adults (18-45 years) | Older adults (>45-years) | Total | p-Value | |

| All-cause in-hospital mortality (%) | 5410 (2.73) | 214,154 (5.33) | 219,564 (5.21) | <0.0001 |

| Morbidity* (%) | 13,781 (7.15) | 294,109 (7.33) | 307,890 (7.70) | <0.0001 |

| Discharge disposition (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Routine/home | 121,623 (64.59) | 1,364,958 (36.15) | 1,486,581 (37.5) | |

| Transfer to short-term hospital | 9593 (5.09) | 117,357 (3.11) | 126,950 (3.2) | |

| Transfer to SNF/ICF/another type of facility | 42,160 (22.39) | 1,772,822 (46.95) | 1,814,981 (45.79) | |

| Home health care | 14,913 (7.92) | 520,542 (13.79) | 535,455 (13.51) | |

| Total discharge other than home (%) | 66,666 (35.41) | 2,410,720 (63.85) | 2,477,386 (62.5) | |

| APR-DRG severity/ loss of function (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Minor loss of function | 34,616 (18.02) | 425,141 (11.22) | 459,756 (11.55) | |

| Moderate loss of function | 98,510 (51.28) | 1,953,248 (51.56) | 2,051,758 (51.55) | |

| Major loss of function | 47,274 (24.61) | 1,173,725 (30.99) | 1,220,999 (30.68) | |

| Extreme loss of function | 11,687 (6.08) | 235,835 (6.23) | 247,522 (6.22) | |

| Total major/extreme loss of function (%) | 58,961 (30.7) | 1,409,560 (37.21) | 1,468,522 (36.9) | <0.0001 |

| APR-DRG risk mortality (%) | <0.0001 | |||

| Minor likelihood of death | 123,776 (64.44) | 1,171,879 (30.94) | 1,295,655 (32.55) | |

| Moderate likelihood of death | 42,510 (22.13) | 1,797,239 (47.45) | 1,839,749 (46.22) | |

| Major likelihood of death | 16,590 (8.64) | 617,641 (16.31) | 634,231 (15.94) | |

| Extreme likelihood of death | 9210 (4.79) | 201,191 (5.31) | 210,401 (5.29) | |

| Total major/extreme likelihood of death (%) | 25,800 (13.43) | 818,832 (21.62) | 844,632 (21.22) | <0.0001 |

| Length of stay (mean) ± SE (days) | 5.6 ± 0.04 | 5.4 ± 0.01 | <0.0001 | |

| Cost of hospitalization (mean) ± SE ($) | 47,365 ± 347 | 37,669 ± 58 | <0.0001 | |

Figure 3. Yearly mortality trend in young adults and old adults with AIS.

AIS: acute ischemic stroke

Regression model derivation for the outcomes of YA

Table 6 includes multivariable regression analysis to predict outcomes of AIS among YA and OA population. All-cause in-hospital mortality (aOR: 0.56; 95%CI: 0.52-0.60), morbidity (aOR: 0.87; 95%CI: 0.83-0.91), discharge disposition to non-home (aOR: 0.60; 95%CI: 0.58-0.61), and major/extreme likelihood of death (aOR: 0.83; 95%CI: 0.81-0.86) were lower among YA than OA admitted with AIS with the c-statistic of 0.672, 0.690, 0.722, and 0.713, respectively (>0.5) which indicate good fit.

Table 6. Multivariable analysis of outcomes among young vs. old adults with AIS hospitalizations.

All models are adjusted for demographics (age, gender, race), patient-level hospitalization variables (admission day, primary payer, admission type, median household income category), hospital-level variables (hospital region, teaching versus nonteaching hospital, hospital bed size), comorbidities and risk factors like hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, obesity, current smoking status, ex-smoker, drug abuse, alcohol abuse, and Charlson Comorbidity Index.

*Morbidity = length of stay >10 days (>90th percentile of AIS hospitalization) and discharge to non-home (transfer to short term hospital, skilled nursing facility, intermediate care facility, or home health care)

APR-DRG: All Patients Refined Diagnosis Related Groups; AIS: acute ischemic stroke

| Odds ratio | 95% confidence interval | p-Value | c-Index | |

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||

| All-cause in-hospital mortality in young adults (reference: older adults) | ||||

| 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.60 | <0.0001 | 0.672 |

| Morbidity in young adults (reference: older adults)* | ||||

| 0.87 | 0.83 | 0.91 | <0.0001 | 0.690 |

| Discharge disposition to non-home in young adults (reference: older adults) | ||||

| 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.61 | <0.0001 | 0.722 |

| APR-DRG major/extreme loss of function in young adults (reference: older adults) | ||||

| 1.02 | 0.998 | 1.05 | 0.0672 | 0.730 |

| APR-DRG major/extreme risk of death in young adults (reference: older adults) | ||||

| 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.86 | <0.0001 | 0.713 |

Discussion

We performed a population-based retrospective analysis of the nationally-representative NIS database to identify adult AIS hospitalizations and risk factors. Stroke in YA has been observed to be uncommon, and cerebrovascular disease reaches peak incidence later in life [19]. This observation has been confirmed in our study as we identified only 4.7% YA AIS hospitalizations, while 95.3% of hospitalizations were in patients who were 45 years or older. Thus, stroke is not a common health condition among YA. However, for those YA who do suffer a stroke, it is a considerable cause of morbidity and has an impact on the loss of work productivity in these patients [9]. Despite the small number of YA who suffer from stroke, we found an increasing prevalence among YA with AIS. From 2003 to 2014, hospitalizations for AIS in young adults increased from 4.36% to 4.70%. This stands in contrast to previous reports of stable rates of stroke incidence and decreasing rates of stroke hospitalization among adults [9]. A possible reason for this seemingly increasing incidence could be due to rising rates of stroke risk factors, including obesity, hypertension, diabetes, tobacco, and alcohol use [9].

Many risk factors among YA are traditional and modifiable, so screening and treatment are possible. These include obesity, drug abuse, history of smoking, infective endocarditis, cardiomyopathy, rheumatic fever, atrial septal disease, ventricular septal disease, HIV infection, and epilepsy. Some of the non-traditional risk factors like arterial-venous malformation, brain tumors, end-stage renal disease, systemic lupus erythematosus, polymyositis, ankylosis spondylosis, hypercoagulable state, polyarteritis nodosa, and fibromuscular dysplasia are significantly associated with YA with AIS.

Notably, in our study, all-cause in-hospital mortality was lower among YA. The prevalence rate of in-hospital mortality decreased from 2003 to 2014 (YA: 4.11% to 2.19% and OA: 7.05% to 4.47%), similar to Lee et al. (1998: 7.0% to 2007: 5.4%; p<0.0001) [20]. A possible explanation for this could be more effective treatment guidelines and strategies when presenting to the hospital. Young people may still be participating in high-risk factors that can lead to an increase in AIS hospitalizations, as shown in our study; however, treatment may have improved, with a concomitant decrease in mortality. Our study also indicated that YA with AIS hospitalizations had a lower chance of morbidity, discharge to short/long-term care, and the likelihood of death. YA and OA AIS hospitalizations had a similar mean LoS. However, the cost of hospitalizations was higher in YA ($47365 vs. $37669, p<0.0001). Stroke is thus an important cause of morbidity in young patients, and although having a small prevalence in the population, it affects hospitalization costs and dramatic impacts on quality of life in survivors. YA are also associated with higher long-term cumulative mortality due to stroke compared to the general population [21]. Stroke causes numerous physical and cognitive problems, long-term consequences, and work-related productivity losses especially in younger populations [21].

A major strength of this study was the findings that were nationally representative for the United States. However, there are limitations to this study. AIS was analyzed as a whole, rather than by identifying AIS patients according to subtype or by comparing other types of stroke. Perhaps, YA with AIS hospitalizations were due to a certain cause or presented as a subtype of AIS; however, this could not be elicited through this study. Additionally, being a retrospective study, we have associations between certain concurrent diagnoses and co-morbidities and AIS, yet we do not know if there is a temporal relationship between the two. We have evaluated in-hospital outcomes and do not have post-discharge records of these patients. Likewise, we are missing other details like stroke location, NIH Stroke Scale, concurrent medication use, the severity of risk factors, etc.

Conclusions

AIS has been shown to be an uncommon problem in YA with better outcomes; however, with the rising prevalence trend of AIS over the past decade in young populations, prevention and treatment strategies need to be examined. Young adults have modifiable risk factors such as obesity, drug and smoking abuse, and heart conditions that can be screened. Besides that, non-traditional risk factors suggest that more awareness and prevention strategies can be targeted to the YA population. Further studies should be done to test whether modifying these factors lowers stroke risk in the young population or to determine if awareness campaigns differ based on the age of the patient targeted.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Health Care Utilization Project (HCUP) issued approval N/A. The data has been taken from Nationwide Inpatient Sample, which is a deidentified database from “Health Care Utilization Project (HCUP)” sponsored by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, so informed consent or IRB approval was not needed for the study. The relevant ethical oversight and HCUP Data Use Agreement (HCUP-4Q28K90CU) were obtained by Urvish Patel for the data used in this study

Animal Ethics

Animal subjects: All authors have confirmed that this study did not involve animal subjects or tissue.

References

- 1.Mortality in the United States, 2013. Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Xu J, Arias E. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25549183/ NCHS Data Brief. 2014:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heart disease and stroke statistics-2016 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. Circulation. 2016;133:38–360. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hospitalization for stroke in U.S. hospitals, 1989-2009. Hall MJ, Levant S, DeFrances CJ. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22617404/ NCHS Data Brief. 2012:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Analysis of 1008 consecutive patients aged 15 to 49 with first-ever ischemic stroke: the Helsinki young stroke registry. Putaala J, Metso AJ, Metso TM, et al. Stroke. 2009;40:1195–1203. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.529883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ischemic stroke in young adults. Experience in 329 patients enrolled in the Iowa Registry of stroke in young adults. Adams HP Jr, Kappelle LJ, Biller J, Gordon DL, Love BB, Gomez F, Heffner M. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:491–495. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540290081021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerebral infarction in young adults: the Baltimore-Washington Cooperative young stroke study. Kittner SJ, Stern BJ, Wozniak M, et al. Neurology. 1998;50:890–894. doi: 10.1212/wnl.50.4.890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stroke in the young in the northern Manhattan stroke study. Jacobs BS, Boden-Albala B, Lin IF, Sacco RL. Stroke. 2002;33:2789–2793. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000038988.64376.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Incidence and short-term outcome of cerebral infarction in young adults in western Norway. Naess H, Nyland HI, Thomassen L, Aarseth J, Nyland G, Myhr KM. Stroke. 2002;33:2105–2108. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000023888.43488.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trends in stroke hospitalizations and associated risk factors among children and young adults, 1995-2008. George MG, Tong X, Kuklina EV, Labarthe DR. Ann Neurol. 2011;70:713–721. doi: 10.1002/ana.22539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and strokes in younger adults. George MG, Tong X, Bowman BA. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74:695–703. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.0020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strokes in young adults: epidemiology and prevention. Smajlović D. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2015;11:157–164. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S53203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deaths from stroke in US young adults, 1989-2009. Poisson SN, Glidden D, Johnston SC, Fullerton HJ. Neurology. 2014;83:2110–2115. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000001042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Comparison between ischemic stroke patients <50 years and ≥50 years admitted to a single centre: the Bergen stroke study. Fromm A, Waje-Andreassen U, Thomassen L, Naess H. Stroke Res Treat. 2011;2011:183256. doi: 10.4061/2011/183256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Long-term morbidity and mortality in patients without early complications after stroke or transient ischemic attack. Edwards JD, Kapral MK, Fang J, Swartz RH. CMAJ. 2017;189:954–961. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.161142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Accuracy of ICD-9-CM codes for identifying cardiovascular and stroke risk factors. Birman-Deych E, Waterman AD, Yan Y, Nilasena DS, Radford MJ, Gage BF. Med Care. 2005;43:480–485. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000160417.39497.a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perioperative stroke, in-hospital mortality, and postoperative morbidity following transcatheter aortic valve implantation: a nationwide study. Thirumala PD, Nguyen FD, Mehta A, et al. J Clin Neurol. 2017;13:351–358. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2017.13.4.351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Validation of the All Patient Refined Diagnosis Related Group (APR-DRG) risk of mortality and severity of illness modifiers as a measure of perioperative risk. McCormick PJ, Lin HM, Deiner SG, Levin MA. J Med Syst. 2018;42:81. doi: 10.1007/s10916-018-0936-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Use of the All Patient Refined-Diagnosis Related Group (APR-DRG) risk of mortality score as a severity adjustor in the medical ICU. Baram D, Daroowalla F, Garcia R, et al. Clin Med Circ Respirat Pulm Med. 2008;2:19–25. doi: 10.4137/ccrpm.s544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brain infarction in young men. Burns RJ, Blumbergs PC, Sage MR. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/550958/ Clin Exp Neurol. 1979;16:69–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trends in the hospitalization of ischemic stroke in the United States, 1998-2007. Lee LK, Bateman BT, Wang S, Schumacher HC, Pile-Spellman J, Saposnik G. Int J Stroke. 2012;7:195–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2011.00700.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ischaemic stroke in young adults: risk factors and long-term consequences. Maaijwee NA, Rutten-Jacobs LC, Schaapsmeerders P, van Dijk EJ, de Leeuw FE. Nat Rev Neurol. 2014;10:315–325. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2014.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]