Abstract

Background:

High antagonistic ability of different Trichoderma species against a diverse range of plant pathogenic fungi has led them to be used as a biological fungicide in agriculture. They can also promote plant growth, fertility, resistance to stress, and absorption of nutrients. They are also opportunistic and symbiotic pathogens, which can lead to the activation of plant defense mechanisms.

Objectives:

The aim of this present study was to investigate possible enhancement of lytic enzymes production and biocontrol activity of T. virens against Rhizoctonia solani through gamma radiation and to find the relationship between changes in lytic enzyme production and antagonistic activity of T. virens.

Material and Methods:

Dual culture conditions were used to evaluate the antagonistic effect of T. virens and its gamma mutants against R. solani. Then, their chitinase and cellulase activities were measured. For more detailed investigation of enzymes, densitometry pattern of the proteins was extracted from the T. virens wild-type and its mutants were obtained via SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Results:

The mutant T.vi M8, T. virens wild-type and mutant T.vi M20 strains showed the maximum antagonistic effects against the pathogen, respectively. Data showed that the mutant T. vi M8 reduced the growth of R. solani by 58 %. The mutants revealed significantly different (p<0.05) protein contents, chitinase and cellulase production (mg.mL-1) and activity (U.mL-1) compared to the wild-type strain. The highest extracellular protein production in the supernatant of chitinase and cellulase TFM was observed for the T.vi M11 and T.vi M17 strains, respectively. The T.vi M12 and wild-type strains secreted chitinase and cellulase significantly more than other strains did. Densitometry of SDS-PAGE gel bands indicated that both the amount and diversity of chitinase related proteins in the selected mutant (T. vi M8) were far higher than those of the wild-type. The diversity of molecular weight of proteins extracted from the T. virens M8 (20 proteins or bands) was very high compared to the wild-type (10 proteins) and mutant T.vi M15 (2 proteins).

Conclusions:

Overall, there was a strong link between the diversity of various chitinase proteins and the antagonistic properties of the mutant M8.

Keywords: Biocontrol, Cellulase, Chitinase, Mutant, Rhizoctonia solani, Trichoderma virens

1. Background

Trichoderma species are known as an effective biological control agent against different plant pathogenic fungi, such as Rhizoctonia solani, Pythium spp. ( 1 ), Macrophomina phaseolina ( 2 ), and Sclerotinia rolfsii ( 3 ). Trichoderma species ability to kill plant pathogenic fungi has led them to be used as a biological fungicide in agriculture ( 4 ). Trichoderma species can also enhance plant growth, fertility, resistance to stress, and absorption of nutrients ( 5 ). In some cases, these fungi are also known as opportunistic and symbiotic pathogens, which can lead to the activation of plant defense mechanisms ( 6 ). Most fungi attacked by T. harzianum have cell walls that contain chitin as a structural backbone and laminarin (ß-1, 3-glucan) as a filling material ( 7 ). T. virens can penetrate into R. solani body and grow extensively within mycelium through destroying the cell wall. This mechanism of action shows that the fungus produces enzymes chitinases and ß-1, 3 glucanases. Further, some other metabolites are produced by T. virens, thus improving enzyme production and activity in such fungi through mutation breeding, may enhance their antagonistic activities ( 8 ). Furthermore, T. viride has a high capability to produce other enzymes involved in detoxification or degradation of different mycotoxins synthesized by the plant pathogens. Finding a suitable Trichoderma strain with high biocontrol and plant growth promoting capabilities is the first step in biological control. In addition to isolation of native strains from different sources, induced gamma radiation mutation is known as one of the widely used methods to enhance the antagonistic potential of Trichoderma fungi. The mutation achieved through gamma rays has resulted in enhanced growth, competition, and sporulation of the fungus simultaneously along with higher expression of the genes associated with increased resistance against R. solani ( 9 ). It has been shown that the biocontrol efficiency of gamma mutants of T. harzianum has also increased dramatically against Sclerotium cepivorum and Sclerotium rolfsii ( 10 ). Marzano et al. showed that the competition between T. harzianum isolate mutated through ultraviolet radiation vs. F. oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici improved via enhancing the tolerance to growth-inhibitory metabolites produced by F. oxysporum ( 11 ). Recent studies have indicated that γ-radiation could affect morphological characteristics such as sporulation of fungus, mycelia colonies shape, color and its growth rate. The mutants had higher inhibitory capability against R. solani ( 12 ). Many studies indicated that γ-mutagenesis could improve production of metabolites and improved biological efficiencies in T. virens ( 13, 14 ). Production of new mutants with greater ability to secrete cellulolytic enzymes compared to the wild-type strain has been achieved by both laboratory and industrial research programs ( 15 , 16 ).

2. Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate possible enhancement of production of lytic enzymes and biocontrol activity of T. virens against R. solani using gamma radiation, and to find the relationship between changes in lytic enzyme production and antagonistic activity of T. virens.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Preparation of T. virens and R. solani

The wild-type T. virens was kindly provided by Yazd Agricultural and Natural Resources Research and Education Centre (infected soils of cucumber). The mutant isolates were prepared in Nuclear Agriculture School, Alborz, Iran ( 14 ). The fungi were maintained on potato dextrose agar (PDA) prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The pathogenic fungus R. solani was obtained from the Microbial collections of Tarbiat Modares University. The fungi were grown at 28±2 °C on potato dextrose agar (PDA) prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions and maintained at 4 °C.

3.2. Antagonistic Activity of Wild-type and Mutant T. virens Strains Against R. solani Under In Vitro Conditions

The antagonistic activity of T. virens strains against R. solani was determined using dual culture technique. Mycelia discs (5 mm diameter) were cut out from actively growing pure cultures of all strains (T. virens and R. solani strains) on PDA at 28 ˚C for 3 days and placed on the opposite sides of 100 mm petri plates containing PDA. The plates were incubated in darkness at 28 ˚C. The growth of the pathogen was measured after 3 days, and mycelia growth inhibition percentage were calculated, following the formula: I % = (1-Cn/ Co) ×100. Cn refers to the average colony diameter of pathogen in the presence of the antagonist and Co denotes the average colony diameter of control.

3.3. Plant Pathogen Cell Wall Preparation

The R. solani cell wall powder was produced according to the method of Elad et al. ( 18 ) with some modifications. The R. solani strain was inoculated into 250 mL flasks containing 50 mL of PDB and incubated at 28 ˚C for 7 days. The mycelia were filtered, washed thoroughly with autoclaved distilled water, and homogenized with a homogenizer, for 5 min at the highest speed. The mycelium suspension was centrifuged at 4500 g for 7 min at 4 ˚C and washed twice with sterile saline solution ( 14 ). The pellet was collected and lyophilized. The dry cell wall of the pathogen was used as substrate for the production of degrading enzymes.

3.4. Cell Wall Degrading Enzymes Production

The wild-type and mutant strains of T. virens were cultured in MYG (Malt extract, Yeast extract, Glucose) agar medium at 28 ˚C for 7 days ( 18 ). The spore suspensions were prepared from seven-day-old cultures in a sterile saline solution (1×107 spores.mL-1). The spores were pelleted through centrifugation at 4500×g for 10 min, and washed twice with a sterile saline solution. The seed cultures were produced in Trichoderma complete medium (TCM) ( 14 ). The medium pH was adjusted to 4.8 and supplemented with 0.3% w/v of glucose. The cultures were prepared in a volume of 50 ml of TCM in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks and were shaken at 180 rpm at 28 ˚C for 24 h. Specifically, 1 mL of spore suspension was inoculated in each flask.

The grown mycelia were collected and transferred to 50 ml of Trichoderma fermentation medium (TFM) for inducing enzyme production ( 14 ). For cellulase production, the medium was supplemented with 0.5% w/v of Phosphoric Acid Swollen cellulose (PASC) and adjusted to pH 4.8. For chitinase production, the medium was supplemented with 0.5% (w/v) of colloidal chitin, with pH adjusted to 5.5. The growth conditions were as described previously ( 19 ). In addition, the dry cell wall of R. solani was used as an inducer substrate for producing degrading enzymes against the pathogen. Triplicate flasks were harvested after 48 h. Trichoderma fermentation medium (TFM) was centrifuged for 7 min at 4500 ×g at 4 ˚C and used for protein plus extracellular enzyme activity estimation ( 14 ).

3.5. Estimation of Protein

After 48 h fermentation, the Bradford’s dye binding method was used for estimating the protein content in the TFM supernatant ( 20 ). Bovine serum albumin (BSA) was considered as a standard protein.

3.6. Estimation Chitinase and Cellulase Activity

The chitinase assay was estimated by the method of Zeilinger et al. ( 21 ). One unit chitinase activity is the amount of enzyme producing 1 μmoL of N-acetyl- glucosamine from the chitin source in the reaction mixture/mL/h under standard conditions. Overall, the cellulase activity of the samples was determined by the method of Shahbazi et al. ( 14 ). For the filter paper activity (FPase) assay, the Whatman no.1 strips were used as the substrate. Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) was used to measure CMCase or endoglucanase activity. The amount of released sugar was assayed via the dinitrosalicylic acid (DNS) method using glucose as the standard. The release of glucose molecules from substrates was considered as quantitative criteria for avicelase activity by the DNS method with glucose as the standard. The International Unit (IU) of activity is defined as the amount of enzyme releasing l μmoL of glucose per hour in a standard assay ( 14 ).

3.7. Electrophoresis and Molecular Size Determination

The molecular weight of the proteins was determined by SDS-PAGE with a 4% (stacking) and 12.5% (separating) polyacrylamide gel based on Laemmli ( 22 ). The gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R-250 in methanol-acetic acid-water (5:1:4, v/v), and decolorized in methanol-acetic acid-water (1:1:8, v/v) (14, 18).The densitometry zymogram pattern of the proteins extracted from the T. virens wild-type and mutant strains were provided by Gel-Pro (Ver.6) and analyzed using one-dimensional gel analysis software: Core Laboratory Image Quantification Software (CLIQS).

3.8. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed with three replications, based on a completely randomized design. The experimental data were subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a Duncan’s test. Significance was defined at p<0.05. The SPSS (developer 13) program was used for all statistical analyses.

4. Results

4.1. Antagonistic Activity of T. virens Strains Against R. solani in Dual Culture

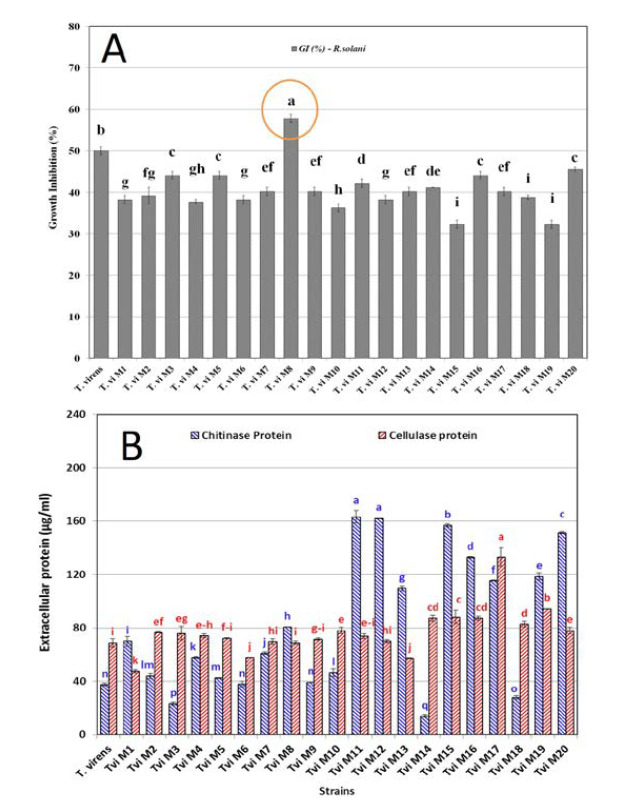

The macroscopic observations during dual culture of T. virens against R. solani showed that the antagonistic mechanisms of the fungus included parasitism and antibiosis. The results revealed a significant difference in growth inhibition percentage of R. solani colonies. On the other hand, the isolates T.vi M8, T.vi wild-type and T.vi M20 showed maximum antagonistic activity against R. solani, respectively (Fig.1A). T.vi M8 reduced the growth of R. solani by 58 %.

Figure 1.

A) The efficiency of the wild-type and mutant T. virens strains in growth inhibition of R. solani after 3 days’ incubation in dual culture assay B) Extracellular protein production of T. virens after 48 hours fermentation in TFM medium.

4.2. Estimating the Chitinase and Cellulase Protein Production

The concentration of extracellular protein produced by different T. virens strains enzyme complexes was determined via the dye binding method of Bradford. The results are shown in Figure 1B. The highest extracellular protein production in the supernatant of chitinase TFM belonged to the strains T.vi M11, T.vi M12, T.vi M15 and T.vi M20, respectively. The supernatant of cellulase TFM of T.vi M17, T.vi M19 and T.vi M15, had the highest extracellular protein production, respectively. The results showed that protein production in both chitinase and cellulase TFM (µg.ml-1) for all mutants had a significant difference at the level of p<0.05 compared to the with wild-type strain.

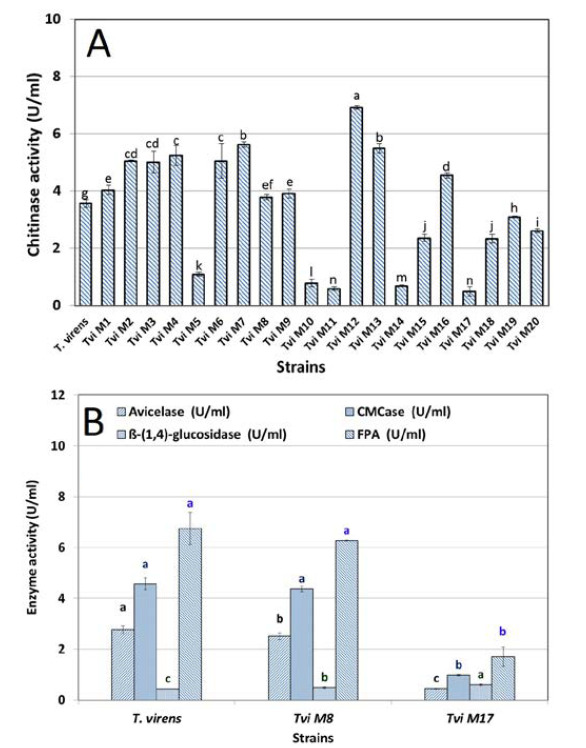

The results of chitinase activity assay of the wild-type and mutant strains are shown in Figure 2A. These results indicate variations in the activity of 20 selected mutants. The chitinase activity in the mutants was significantly different ( p<0.05) compared to the wild-type T. virens strains. The enzyme activity of some mutants was higher than that of the wild strain, while other isolates revealed lower activity. Generally, the chitinase activity of the studied T. virens isolates was affected by gamma radiation. T.vi M12 secreted significantly more chitinase than the wild-type and other mutant strains did. In addition, T.vi M8 showed no high difference with wild- type regarding to the chitinase activity.

Figure 2.

A) The chitinase activity (U.ml-1) of wiled-type (T. virens) and mutant (Tvi M -M ) strains in TFM supernatant after 48 h incubation at 180 rpm and 28 ˚C. B) Cellulase (Endo- and Exo-glucanase) enzyme activity of the wild-type and mutant T. virens strains (Tvi M8 and Tvi M17) in TFM supernatant after 48 h incubation at 180 rpm and 28 ˚C

The cellulase enzyme activity (Endo- and Exo- glucanase) of the mutant and wild-type strains TFM supplemented with colloidal cellulose as a substrate were investigated. Figure. 2B depicts the production of endo- and exo-glucanase by mutant strain T. vi M8 compared to T.vi M17 and the wild-type strains. In the case of exo-glucanase (U.ml-1), the results showed that T.vi M8 and wild-type strain were not different from each other. On the other hand, T.vi M17 had the lowest activity of exo-glucanase. The highest avicelase activity was obtained 2.3 U.ml-1 for the wild-type strain. The CMCase activity did not show any significant difference between the mutant and wild-type strains (2.2 U.ml-1).

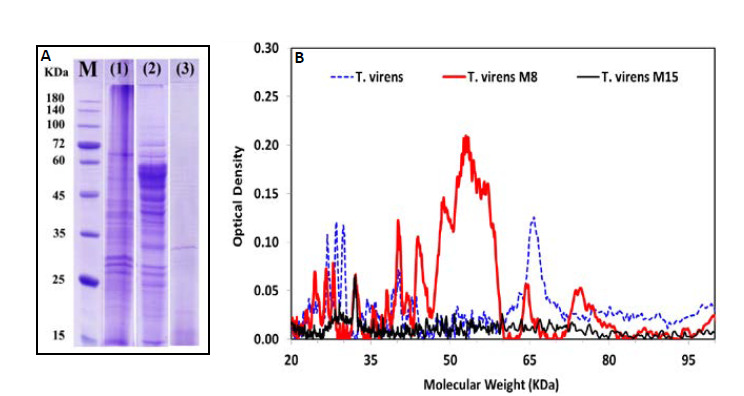

4.4. Electrophoresis and Molecular Size Determination

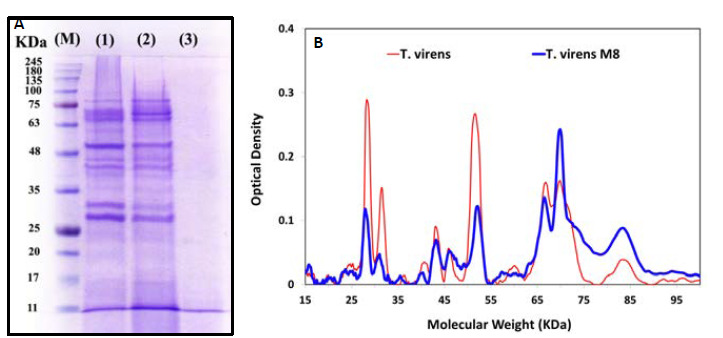

Figure 3 displays the electrophoresis patterns obtained by SDS- PAGE analysis of precipitated cell-free TFM supernatants and densitometry pattern of proteins extracted from the wild-type and mutant strains T.vi M8 as powerful antagonists and T.vi M15 as a weak one . The SDS-PAGE analysis of the crude proteins indicated the presence of different protein bands within the range of 10.5-245 KDa. Both the amount and diversity of chitinase related proteins in the cell free TFM supernatant of mutant T.vi M8 were higher as compared to the wild-type and mutant T.vi M15. The densitometry of protein bands showed that the diversity of molecular weight of proteins extracted from the T. viM8 (20 bands of proteins) was very high compared to the wild-type (10 bands) and mutant T.vi M15 strains (2bands).

Figure 3.

The profile of chitinase enzyme proteins (A) and densitometry zymogram pattern of proteins extracted (B) from the T. virens wildtype and two mutant strains by Gel–Pro (Ver.6): marker (M) Prestain Protein Ladder (CinnaGenTM PR901641); (1) (T. virens wild-type); (2) (T. virens M8) and (3) (T. virens M15).

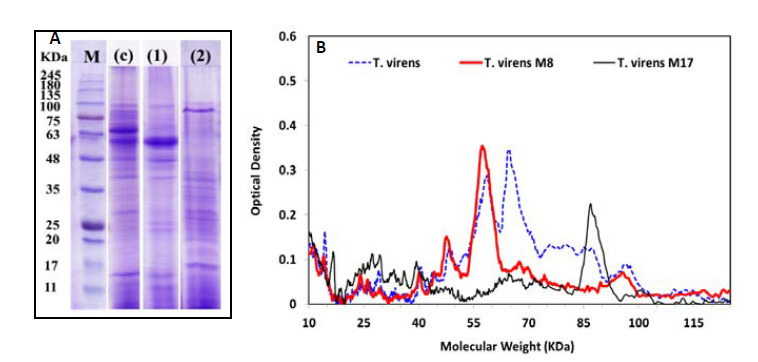

Extracellular cellulase protein profiles of mutant strains in the supernatant of TFM were assessed using SDS- PAGE with the results shown in Figure 4. Two sharp bands at molecular weights 64 and 58KDa in the protein profiles of T. virens wild-type were related to enzymes Cel 7A (CBH I) and Cel 6A (CBH II), respectively. The densitometry pattern of proteins showed a sharp band (38.1%) with a molecular weight of 58 KDa in T. virens M8 which is very heavier than that of the wild-type strain (14.3%).

Figure 4.

The profile of cellulase (A) and densitometry of protein pattern (B) extracted from the T. virens wild-type and two mutant strains by Gel–Pro (Ver.6): marker (M) Pre-stained Protein Ladder (CinnaGenTM PR901641); (c) (T. virens wild-type); (2) (T. virens M8) and (3) (T. virens M17).

4.5. Production of Cell Wall Degrading Enzymes Against R. solani

The selected antagonist mutant (T.vi M8) and the wildtype strain produced and secreted various cell wall degrading enzymes when grown in the TFM media containing R. solani cell wall as the carbon source. There were differing patterns in the cell wall degrading enzyme production by various strains during mycoparasitism at 48 h incubation with pathogen cell wall (Fig. 5). The results showed that there is a difference between some enzymes or proteins produced by the mutant and wild-type strains, when fermented in the presence of the cell wall of the pathogen R. solani (Table 1). The extracellular protein in the T. vi M8 (537.46 μg.ml-1) was significantly higher than that in the wild-type strain (478.5 μg.ml-1). In addition, T. vi M8 produced more active hyphal wall degradation enzymes (10.63 U.ml-1) compared to the wild-type strain (9.14U.mL1) when the enzyme production was induced by R. solani cell wall in the fermentation broth.

Figure 5.

The profile of proteins (A) and densitometry of protein pattern (B) secreted into the culture supernatants of T. virens: Number of 1, 2 and 3 for culture supernatants fermented with wild-type strain, mutant strain and non-inoculated culture supernatants fermentation media, respectively. “M” indicates a molecular weight marker.

Table 1.

Comparison of extracellular protein production, Total chitinase, N-acethyl glucose aminidase, exoglucanase, endoglucanase, β-glucosidase and total cellulase activity (U.ml-1) of T. virens mutants in TFM supernatant supplemented with R. solani hyphal wall powder after 48 h incubation at 180 rpm and 28 ˚C.

| T. virens | T. vi M8 | |

|---|---|---|

| Extracellular protein (µg.ml-1) | 478.50 ± 33.21 | 537.46 ± 33.33 |

| Total chitinase (U.ml-1) | 5.86 ± 1.15 | 6.13 ± 1.03 |

| N-acethyl glucose aminidase (U.ml-1) | 0.08 ± 0.02 | 0.09 ± 0.02 |

| Exo-glucanase (U.ml-1) | 2.39 ± 0.33 | 2.06 ± 0.14 |

| Endoglucanase (U.ml-1) | 3.92 ± 0.36 | 3.92 ± 0.82 |

| ß-glucanase (U.ml-1) | 0.06 ±0.01 | 0.07 ± 0.01 |

| Total cellulase (U.ml-1) | 1.81 ± 0.11 | 1.79 ±0.23 |

| Hyphal wall degradation enzymes activity (U.ml-1) | 9.14 ± 0.42 | 10.63 ± 0.41 |

5. Discussion

Enzymes such as chitinases, cellulases and glucanases are considered as the most important enzymes against plant pathogens ( 23 ). In this regard, chitinolytic enzymes of T. harzianum have been purified and characterized ( 24 ). Additionally, the chitinase activity of T. viride strains has been studied under in vitro conditions ( 25 ). It was previously reported that T. harzianum produce different cellulolytic enzymes ( 26 ). The lytic enzymes, such as chitinases and cellulases, may take part simultaneously in antibiosis and parasitism process. In this regard, Elad et al. ( 18 ) demonstrated hyphal penetration by Trichoderma spp., mediated by enzyme activity. In addition, T. harzianum was able to parasitize R. solani hyphae by producing chitinase ( 27 ). According to the antagonistic results in dual culture, it could be concluded that an increase in the amount of degrading enzymes such as chitinase and cellulase enzymes alone cannot result in higher antagonistic activity of T. virens mutants against pathogenic fungi. Since various factors may interfere with the result, determining the extracellular protein concentration is not always simple ( 28 ). Trichoderma spp. are known for their ability to produce extracellular proteins and enzymes that degrade cellulose and chitin. Different strains of them also produce more than 100 different metabolites with antibiotic activities ( 29 ). Specifically, three main factors affect these measurements. Initially, the presence of non-protein components in the enzymatic solution and/ or reaction medium can be a source of error if they interfere with the results of the quantitative method. Secondly, each protein dosage method is based on a different quantification and identification principle. Finally, other non-chitinase proteins in the enzyme mixture may affect the interpretation of the specific activity results. Such differences are also because different enzymes have different primary structures, alongside different degrees of glycosylation. Thus, these factors are reflected in the response of the proteins from wild-type and mutant strains of T. virens.

Since fungal cell walls are composed mainly of chitin and β-1, 3-glucans embedded in a matrix of amorphous material ( 23 ), successful wall degradation requires the activity of more than one enzyme. Sivan and Chet ( 28 ) mentioned that a coordinated action of polysaccharides, lipases, and proteases is necessary in antibiosis. The present investigation demonstrated that T. virens mutant M8 had highest antagonistic activity against R. solani. The data revealed that γ-radiation altered the genetic makeup of T. virens and greatly enhanced its biocontrol capability as reflected by increasing the inhibition zone and reducing R. solani growth after treatment with T.vi M8 compared to the parental strain of T. virens. These results may confirm that the mutation can increase antagonistic traits of the selected mutants against R. solani. In summary, the results showed that antibiosis by producing volatile compounds, antibiotic metabolites, and/or extracellular enzymes might contribute to the inhibitory effects of T. virens or its selected mutants against R. solani. As noted, one of the antibiosis components is the production of degrading enzymes in antagonistic fungi, including T. virens. Detection of changes in the production profile of these enzymes in a mutant form with the best inhibitory potential for pathogen growth is significant, which we continued to address.

According to densitometry pattern of proteins, there was a strong link between the diversity of various chitinase proteins and the antagonistic properties of the mutant M8, not merely the amount or activity of proteins. This study confirms that, although chitinase is generally considered as a critical enzyme for mycoparasitism since chitin is the most abundant component in many fungal cell walls, other lytic enzymes and metabolites may also be involved in the complete degradation of fungal cell walls ( 7 ). Di Pietro et al. (32) showed that the antifungal activity of the chitinase was synergistically enhanced when combined with gliotoxin produced by T. virens. Cellulase complexes secreted by Trichoderma species trigger ISR in plants such as tobacco, lima bean and corn, by promoting the up-regulation of ethylene (ET) or jasmonate (JA) pathways, through a concentration- dependent pattern resulting in the response ( 33 ). Trichoderma concentration in the roots and their interactions affect this response ( 34 ). However, the mechanism through which the Trichoderma cellulase- like macromolecules were produced and induced ISR in plants has still remained unclear. Interestingly, induced systemic resistance initiated by both pathogens and plant growth-promoting microbes (PGPR) such as Trichoderma ( 35 ). The results of the study showed that there is a difference between some enzymes or proteins produced by the strains, when fermented in the presence of the cell wall of the pathogen. Most of the biological control agents are known to produce chitinase and β-1, 3-glucanase enzymes which could degrade the cell wall leading to the lysis of hyphae of the pathogen ( 36 ). The pathogen cell wall and chitin induce nag1 gene, but it is only triggered when there is contact with the pathogen ( 6 , 37 ). The mutant M8 showed greater enzyme production and activity compared to the wild-type strain when incubated with R. solani cell wall substrate. This could be due to the fact that gamma mutation modifies some genes thus particularly affecting cell wall decomposition ( 38 ). The protein banding pattern of T. vi M8 (Figure 5, lane 1 & 2) contained several major proteins within the molecular weight of 25-100 KDa. It was previously reported that Trichoderma produce different β-1, 3-glucanases with molecular weights of 17, 31, 36, 67, 74, 75, 78, and 110 KDa ( 37 ). A sharp band was observed in the molecular weight of 31 and 67 KDa for T. vi M8 which were probably were related to β-1, 3-glucanases enzyme ( 37 , 39 ). The difference in the molecular weight of β-1, 3 glucanases was not new as the molecular mass of β-glucanase appears to vary between species ( 40 ) as well as within species ( 41 ). The difference between catalytic activities of isozymes or subunits of β-glucanase of Trichoderma spp. has been reported previously. Several factors may cause the isozymes to have been listed as anomalous migration of protein on SDS-PAGE gels ( 42 ), type of growth substrate, type of reaction, and method of purification ( 43 ). However, activation of the specific gene was a major factor influencing the number of protein bands on SDS-PAGE. Haran and other ( 44 ) showed that, depending on the strain, the chitinolytic system of T. harzianum may have five to seven enzymes. In the strain T. harzianum TM, this system includes four endochitinases (52, 42, 33, and 31 kDa), two β- (1, 4)-N-acetylglucosaminidases (102 and 73 kDa), and one exochitinase (40 kDa). Two 1, 4-β-N- acetylglucoaminidase have been reported to be excreted by T. harzianum. Ulhoa and Peberdy ( 45 ) described the purification of these from T. harzianum, whose native molecular mass was estimated to be 118 KDa through gel filtration, while this value was 66 KDa through SDS-PAGE. Thus, it is suggested that the active form was a homodimer. Haran and others (44) reported a 102 KDa N-acetylglucoaminidase (CHIT 102) which was expressed by T. harzianum strain TM grown on chitin as the sole carbon source. It was assumed that it is essentially the same enzyme described by Ulhoa and Peberdy ( 45 ) with different estimates of its molecular mass suggested to be the result of the different procedures used. The other 1, 4-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase, purified from T. harzianum strain Pl, was estimated to be 72 kDa and had a pI of 4.6 ( 20 ). Haran and other ( 44 ) reported a 73 KD aglucosaminidase (CHIT 73) which was expressed and excreted when T. harzianum strain TM was grown on chitin as the sole carbon source, but was not detected when the fungus was grown on glucose. The activity of CHIT 73 was found to be heat-stable. N-acetyl glucoaminidase enzymes were observed with the molecular weight 69 KDa for T. virens wild-type and T. vi M8 in SDS-PAGE profiles. In addition, the enzyme bands with molecular weights of 52 and 42 kDa were found in both profiles of T. vi M8 and wild- type of T. virens belonging to the chitinase enzyme. Based on densitometry results, in terms of frequency of chitinase with the molecular weight of 42 kDa, there was no significant difference between the parent and mutant samples. However, in the mutant isolate, the frequency of enzyme 1, 4-β-N-acetylglucosaminidase with the molecular weight of 69 kDa was almost twice as large as that of the parent.

6. Conclusion

Mutation and screening of Trichoderma species can increase amounts of antagonistic factors such as some lytic enzymes and their antagonistic traits ( 46 , 47 , 48 ). These extracellular enzymes are induced during interactions between Trichoderma spp. and cell-wall materials of phytopathogenic fungi. Recently, some studies have been well carried out to explore the role of proteolytic enzymes ( 49 ) β-1, 3-glucanolytic enzymes ( 50 ) and chitinase ( 51 ). However, although there are many factors that determine the behavior of a biocontrol agent such as T. virens ( 30 ), it is undeniably important and crucial that all these factors should ultimately lead to an increase in its efficacy against pathogenic pathogens. In other words, the antagonistic and inhibitory activity of these fungi against plant pathogenic microorganism of R. solani is more important. As a result, the antagonistic function of the T. virens isolates against R. solani was considered as the main criterion in the screening of the mutants and the data interpretation. In this study, the antagonistic activity in dual culture, amount and activity of cell wall degrading enzymes such as chitinase and cellulases were evaluated and attempts were made to determine the relationship between antagonism and enzymatic properties especially chitinase amount and its activity. The results revealed that mutant T. vi M8 had the highest inhibitory against R. solani in dual culture. T. virens mutated through gamma rays resulted in enhanced growth, competition, and sporulation of the fungus concurrent with the elevated expression of genes associated with increased resistance to R.solani ( 9 ). Contrary to the assumption that the increase in antagonistic activity should be accompanied by an increase in the amount and activity of enzymes such as chitinase and cellulose ( 52 ), this study found that this assumption is not always correct. Nevertheless, note that other morphological and physiological traits and metabolites may be involved in the complete degradation of fungal cell walls ( 7 ). Chitinase is generally considered as a critical enzyme for mycoparasitism as chitin is the most abundant component in many fungal cell walls. On the other hand, in this study, the densitometry zymogram pattern showed that both the amount and diversity of chitinase related proteins in the selected mutant were far higher than those of the wild type. The diversity of molecular weight of proteins extracted from the T. virensM8 (20 proteins or bands) was very high as compared to that of the wild-type (10 proteins) and mutant T.vi M15 (2 proteins). In other words, according to these data, there is a strong link between the diversity of various chitinase proteins and the antagonistic properties of the mutant M8, not merely the amount or activity of proteins.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported by grants from the Radiation Application Research School (Project No. A88A099), Nuclear Science and Technology Research Institute (NSTRI), Atomic Energy organization of IRAN (AEOI).

References

- 1.Maisuria KM, Patel ST. Seed germinability, root and shoot length and vigor indexof soybean as influenced by rhizosphere fungi. Karnataka J Agric Sci. 2009; 22:1120–1122. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Larralde-Corona CP, Santiago-Mena MR, Sifuentes Rincón AM, Rodríguez-Luna IC, MA, Shirai K, Narváez- Zapata JA. Biocontrol potentialand polyphasic characterization of novel native Trichoderma strains against Macrophomina phaseolina isolated from sorghum and common bean. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2008;80:67–177. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suraiya Y, Sabiha S, Adhikary SK, Nusrat J, Sanzida R, Imranur Rahman MD. In vitro evaluation of Trichoderma harzianum (Rifai.) against some soil and seed borne fungi of economic importance. IOSR-JAVS. 2014;7(7):33–37. doi: 10.9790/2380-07723337. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma M, Brar SK, Tyagi RD, Surampalli RY, Valero JR. Antagonistic fungi, Trichoderma spp. : panoply of biological control. Biochem Eng j. 2007;37:1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2007.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Souza JT, Bailey BA, Pomella AWV, Erbe EF, Murphy CA, Bae Het al. Colonization of cacao seedlings by Trichoderma stromaticum, a mycoparasite of the witches’ broom pathogen, and its influence on plant growth and resistance. Biol Control. 2008;46:36–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2008.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harman GE, Howel CR, Viterbo A, Chet I, Lorito M. Trichoderma species-Opportunistic, avirulent plant symbionts. Nat. Rev Microbiol 2004;2:43–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peberdy JF. Fungal cell walls - a review. In: Kuhn PJ, Trinci APJ, Jung MJ, Goosey MW, Editors. Biochemistry of cell walls and membranes in fungi. Springer-Verlag, Berlin. 1990. pp.5- 30. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-74215-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ghasemi S, Safaie N, Shahbazi S and Askari H. Enhancement of Lytic Enzymes Activity and Antagonistic Traits of Trichoderma harzianum Using γ-Radiation Induced Mutation. J Agr Sci Tech. 2019; 21(4):1035–1048*. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mukherjee PK, Latha J, Hadar R, Horwitz BA. TmkA a mitogen- activated protein kinase of Trichoderma virens, is involved in biocontrol properties and repression of conidiation in the dark. Eukaryotic Cell. 2003;2(3):446–455. doi: 10.1128/EC.2.3.446-455.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coventry E, Noble R, Mead A, Marin FR, Perez JA, Whips JM. Allium White Rot Suppression with Composts and Trichoderma viride in Relation to Sclerotia Viability. Phytopathology. 2006;96(9):1009–1021. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-96-1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marzano M, Gallo A, Altomare C. Improvement of biocontrol efficacy of Trichoderma harzianum vs. Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici through UV-induced tolerance to fusaric acid. Biol Control. 2013;67(3):397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2013.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mohamadi AS, Shahbazi S, Askari H. Investigation of γ-radiation on morphological Characteristics and antagonist potential of Trichoderma viride against Rhizoctonia solani. Biol Control. 2014;34(3):324–334. doi: 10.15171/ijb.1224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rey MD, Benítez J. Improved antifungal activity of a mutant of Trichoderma harzianum CECT 2413, which produces more extracellular proteins. Appl Microbial Biotechnol. 2001;55:604– 608. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1538-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shahbazi S, Ispareh K, Karimi M, H, Ebrahimi MA. Gamma and UV radiation induced mutagenesis in Trichoderma reesei to enhance cellulases enzyme activity. Intl J Farm & Sci. 2014:543–554. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Atalla RH, Hackney JM, Uhlin I and Thompson NS. Hemicelluloses asstructure regolatores in the aggregation of native cellulose. Int j Biol Macromol. 1998;15:109–112. doi: 10.1016/0141-8130(93)90007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barr BK, Hsieh YL, Ganem B and Wilson DB. Identification of Two Functionally Different Classes of Exocellulases. Biochemistry. 1996;35:586–592. doi: 10.1021/bi9520388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elad Y, Chet I, Henis Y. Degradation of plant pathogenic fungi by Trichoderma harzianum. Can J Microbiol. 1982;28:719– 725. doi: 10.1139/m82-110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elad Y, Chet I, Boyle P, Henis Y. Parasitism of Trichoderma spp. on Rhizoctonia solani and Sclerotium rolfsii Scanning electron microscopy and fluorescence microscopy. Phytopathology. 1983;73:85–88. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-73-85. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shahbazi S, AhariMostafavi H, Ebrahimi MA, Askari H, Mirmajlessi M, Karimi M. Enhancement of Chitinase Gene Activity In Mutated Trichoderma harzianum via Gamma Radiation. CropBiotech. 2013;5:33–40. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive for the quantification of microgram of protein utilizing the principle of protein- dye binding. Anal biochem. 1976;72:248–258. doi: 10.1006/abio.1976.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zeilinger S, Galhaup C, Payer K, Woo S, Mach R, Fekete Csaba L, Lorito M, Kubicek CP. Chitinase gene expression during mycoparasitic interactions of Trichoderma harzianum with its host. Fungal Genet Biol. 1999;26:131–140. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1998.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structure proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chet I, Baker R. Isolation and biological potential of Trichoderma hamatum from soil naturally suppressive of Rhizoctonia solani. Phytopathology. 1981;71:268–290. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-71-286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lorito M, Harman GE. Chitinolytic enzymes produced by Trichoderma harzianum: antifungal activity of purified endochitinase and chitobiosidase. Phytopathology. 1993;83(3):302–307. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-83-302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Domsch KH, Gams W, Anderson T-W. Trichoderma. Compendium of Soil fungi. Academic Press. 1980;1:795–709. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Petenbauer CK, Heidenreich E. Effect of benomyl and benomyl resistance on cellulase formation by Trichoderma reesei and Trichoderma harzianum. Can J Microbiol. 1992;38:1292–1297. doi: 10.1139/m92-213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benhamou N, Chet I. Hyphal interaction between Trichoderma harzianum and Rhizoctonia solani: ultrastructure and gold chemistry of the mycoparasitic process. Phytopathology. 1993;83:1062–1071. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-83-1062. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sivan A, Chet I. Degradation of fungal cell wall by lytic enzymes of Trichoderma harzianum. J Gen Microbiol. 1989;135:675– 682. doi: 10.1099/00221287-135-3-675. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaia DAM, Zaia CTBV, Lichtig J. Determination of total protein via spectrophotometer: advantages and disadvantages of existing methods. Quim Nova. 1998;21(6):787–793. doi: 10.1590/s0100-40421998000600020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sivasithamparam K, Ghisalberti EL. Secondary metabolism in Trichoderma and Gliocladium. In: Kubicek CP, Harman GE, editors. Trichoderma and Gliocladium. Taylor and Francis, London, 1998.pp139-191 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gusakov AV. Alternatives to Trichoderma reesei in biofuel production. Trends Biotechnol. 2011;29:419–425. doi: 10.1016/J.TIBTECH.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Di Pietro A, Lorito M, Hayes CK, Broadway RM, Harman GE. Endochitinase from Gliocladium virens: Isolation, characterization and synergistic antifungal activity in combination with gliotoxin. Phytopathol. 1993;83:308–313. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-83-308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hermosa MR, grondona I, Iturriaga JM, Diaz C, Castro E, Monte E et al. Molecular characterization and Identification of biocontrol isolate of Trichoderma spp. App. Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:1890–1898. doi: 10.1128/AEM.66.5.1890-1898.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Segarra G. Proteome, salicylic acid, and jasmonic acid changes in cucumber plants inoculated with Trichoderma asperellum strain T34. Proteomics. 2007;7:3943–3952. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200700173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Djonovic S, Pozo MJ, Dangott LJ, Howell CR. Sm1, a proteinaceous elicitor secreted by the biocontrol fungus Trichoderma virens induces plant defense responses and systemic resistance. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2006;19:838– 853. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-19-0838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sangle UR, Bambawale OM. New strains of Trichoderma spp. strongly antagonistic against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. sesami. J Mycol Plant Pathol. 2004;34(1):107–109. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lorito M, Harman CK, Di Pietro A. Purification, characterization and synergistic activity of a glucans 1, 3-beta glucosidase and an N-acetylglucosaminidase from Trichoderma harzianum. Phytopathol. 1994;84:398–405. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-84-398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dana M, Mejias R, Mach RL, Benitez T, Pintor-Toro JA, Kubicek CP. Regulation of chitinase 33 (chit33) gene expression in Trichoderma harzianum. Curr Genet. 2001;38:335–342. doi: 10.1007/s002940000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Noronha EF, Ulhoa CJ. Characterization of a 29-kDa L-1, 3-glucanase from Trichoderma harzianum. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2000;183(1):119–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2000.tb08944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nobe K, Sakai Y, Nobe H, Takashima J, Paul RJ, Momose K. Enhancement effect under high glucose conditions on U46619- induced spontaneous phasic contraction in mouse portal vein. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:1129–1142. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.040964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pitson SM, Seviour RJ, McDougall BM. Noncellulolytic fungal L-glucanases: their physiology and regulation. Enzyme Microb Technol. 1993;15:178–192. doi: 10.1016/0141-0229(93)90136-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mrsa V, Klebl F, Tanner W. Purification and characterization of the Saccbaromyces cerevisiae Bg12 gene product, a cell wall endo-β-1, 3-glucanase. J Bacteriol. 1993; l75: 2102–2106. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.7.2102-2106.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amano Y, Masahiro S, Kazutosi N, Eiichi H, Takahisa K. Fine substrate Specificities of Four Exo-Type Cellulases Produced by Aspergillus niger, Trichoderma reesei, and Irpexlacteus on (1→3), (1→4)-β-D-Glucans and Xyloglucan. J Biochem. 1996;120(6):1123–1129. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haran S, Schickler H, Oppenheim A, Chet I. Differential expression of Trichoderma harzianum chitinases during mycoparasitism. Phytopathology. 1996;86:980–985. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-86-980. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ulhoa CJ, Peberdy JF. Regulation of chitinase synthesis in Trichoderma harzianum. J Gen Microbiol. 1991;137:2163–2169. doi: 10.1099/00221287-137-9-2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jun H, Bing Y, Keying Z, Xuemei D, Daiwen C. Strain improvement of Trichoderma reesei Rut C-30 for increased cellulase production. Indian J Microbiol. 2009;49:188–195. doi: 10.1007/s12088-009-0030-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J, Zhang G, Wang W and Dongzhi W. Enhanced Cellulase Production in Trichoderma Reesei RUT C30 via Constitution of Minimal Transcriptional Activators. Microb Cell Fact. 2018 ;17(1):75. doi: 10.1186/s12934-018-0926-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Silva J. A novel Trichoderma reesei mutant RP698 with enhanced cellulase production. Braz J Microbiol. 2020;51:537–545. doi: 10.1007/s42770-019-00167-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kredics L, Antal Z, Szekeres A, Hatvani L, ManczingerL,Vagvolgyi C, Nagy E. Extracellular proteases of Trichoderma species. A review. Acta Microbiol Immunol Hung. 2005;52:169–184. doi: 10.1556/AMicr.52.2005.2.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kubicek CP. Molecular biology of biocontrol Trichoderma. in: Aurora, DK, editor. fungal biotechnology in agricultural, food, and environmental applications. Marcel Dekker, New York, 2004;p.135-145 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoell LA, Klemsdal SS, Vaaje-Koistad G, Hom SJ, Eijsink VGH. Over expression and characterization of a novel chitinase from Trichoderma atroviride strain PI. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005;1748:180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jong-Min Baek Charles R, Howell C, Kenerley M. The role of an extracellular chitinase from Trichoderma virens Gv29-8 in the biocontrol of Rhizoctonia solani. Curr Genet. 1999;35:41– 50. doi: 10.1007/s002940050431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]