Abstract

BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: Cholesteatoma is an inflammatory lesion of the temporal bone that uncommonly involves the external auditory canal (EAC). In this large case series, we aimed to define its imaging features and to determine the characteristics most important to its clinical management.

METHODS: Thirteen cases of EAC cholesteatoma (EACC) were retrospectively reviewed. Clinical data were reviewed for the history, presentation, and physical examination findings. High-resolution temporal bone CT scans were examined for a soft-tissue mass in the EAC, erosion of adjacent bone, and bone fragments in the mass. The middle ear cavity, mastoid, facial nerve canal, and tegmen tympani were evaluated for involvement.

RESULTS: Patients presented with otorrhea, otalgia, or hearing loss. Eight cases were spontaneous, and five were postsurgical or post-traumatic. CT imaging in all 13 cases showed a soft-tissue mass with adjacent bone erosion. Intramural bone fragments were identified in seven cases. This mass most often arose inferiorly (n = 8) or posteriorly (n = 8), but it was circumferential in two cases. We noted middle ear extension (n = 5), mastoid involvement (n = 4), facial canal erosion (n = 2), and tegmen tympani dehiscence (n = 1).

CONCLUSION: Temporal bone CT shows EACC as a soft-tissue mass within the EAC, with adjacent bone erosion. Bone fragments may be present within the mass. The cholesteatoma may extend into the mastoid or middle ear, or it may involve the facial nerve canal or tegmen tympani. Recognition of this entity and its possible extension is important because it may influence clinical management.

Acquired cholesteatoma is an inflammatory mass of the petrous temporal bone; it is most commonly encountered in the middle ear cavity. External auditory canal (EAC) cholesteatoma (EACC) is a rare entity with an estimated occurrence of one in 1000 new patients at otolaryngology clinics (1). Patients with EACC typically present with otorrhea and a chronic, dull pain due to the local invasion of squamous tissue into the bony EAC (2). Most cases are spontaneous or occur after surgery or trauma to the auditory canal, though pre-existing ear-canal stenosis or obstruction has also been reported to produce EACC (3). The clinical differential diagnosis covers a range of operative and nonoperative conditions, including neoplasms of the EAC and inflammatory or infective conditions such as keratosis obturans, postinflammatory medial canal fibrosis, and malignant otitis externa. The true extent of EACC may be inapparent on clinical examination. For these reasons, the neuroradiologist may have an important role in the diagnosis and management of these lesions.

The purpose of our study was to define the typical imaging features of EACC at CT. In addition, we wished to determine those features that distinguish EACC from its clinical differential diagnoses or that might substantially alter its management.

Methods

We reviewed the radiologic images and clinical data of 13 cases of EACC. These cases were managed or reviewed at our institution over a 15-year period from 1986 to 2001. All patients underwent a preoperative high-resolution temporal bone CT examination. In 12 of 13 patients, imaging was performed with nonenhanced direct axial and coronal 1-mm sections. These were reconstructed with a bone algorithm and viewed with wide windows (4000 HU), centered at 350 HU. The other patient’s CT examination was performed as a nonenhanced direct axial study with 2-mm sections and coronal reformatted images.

Three neuroradiologists (K.L.S., C.M.G., H.R.H.) evaluated each CT image. The EAC was examined for the presence of a soft-tissue mass and for its location within the canal with respect to the anterior, posterior, superior, or inferior walls. The subjacent bone was assessed for erosion. The soft-tissue mass was examined for the presence of bone fragments. Important landmarks in the petrous temporal bone were then evaluated for their integrity: facial nerve canal, tegmen tympani (roof of the middle ear cavity), and mastoid air cells. In each patient, the clinical data were reviewed with respect to the presenting symptoms and proposed etiology. Specifically, the clinical data collected included information about hearing loss, otorrhea, otalgia, facial nerve function, and history of trauma or previous surgical intervention. Diagnosis of all cases was confirmed at surgery and/or histologic examination of the lesion.

Results

Thirteen patients with the diagnosis of EACC were found. Of the 13 patients treated for EACC and imaged with CT, complete clinical records were available in 11 cases, and a partial history, in two. The patients’ ages ranged from 15 to 74 years (mean age, 44 years). Seven were female and six were male. Otorrhea was the presenting clinical symptom in six of 11 patients, hearing loss was found in four patients, and otalgia occurred in three patients. In no patient was an abnormality of facial nerve function noted on clinical examination. Eight cases were considered spontaneous, and five involved a history of surgery (3) or trauma (2). The prior surgeries included tympanoplasty (1) and partial mastoidectomy (2). The two patients with trauma had temporal bone fractures secondary to motor vehicle accidents. All 13 patients had surgical and/or pathologic correlation of EACC.

On evaluation of the CT images, all 13 patients had a soft-tissue attenuating mass and adjacent bone erosion of the EAC (Fig 1). The mass involved more than one wall of the EAC in 12 cases and included circumferential involvement of the canal in two cases. The inferior wall (eight cases) and posterior wall (eight cases) were most commonly involved; however, the lesion could be found in any portion of the EAC. In the spontaneous group, the location of the lesion was similar to that of the postsurgical/post-traumatic group. Small, hyperattenuating bone fragments were seen within the soft-tissue mass in seven cases (Fig 2). The mass extended into the middle ear in five cases (Fig 3). In these cases in which the mass extended into the middle ear cavity and involved both the middle ear and the EAC, the origin of the mass was determined on the basis of imaging and surgical findings. On images, the pattern of growth revealed most lesions to be in the EAC, and erosion of the adjacent EAC bone was observed. Erosion into the mastoid air cells was present in four cases. Two cases had erosion into the facial nerve canal; one involved the tympanic segment and the other involved the mastoid segment of the facial nerve canal. The tegmen tympani was dehiscent in one case, and this finding prompted surgical exploration and repair (Table).

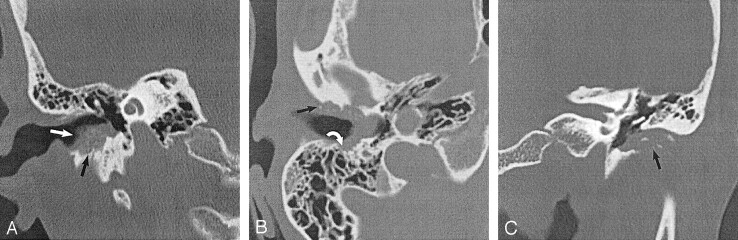

Fig 1.

EACC. Used with permission (24).

A, Coronal temporal bone CT image shows an EACC as a soft-tissue mass in the inferior EAC, with associated erosion of the subjacent bone (arrow). Note the medial bowing of the tympanic membrane in this postsurgical 40-year-old woman with a history of hearing loss.

B, Axial temporal bone CT image in the same patient shows the soft-tissue mass filling the inferior EAC (white arrow), with anterior (black arrow) and posterior EAC erosion. Erosion involving more than one EAC wall is typical.

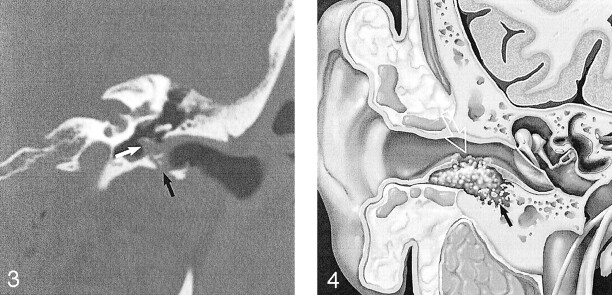

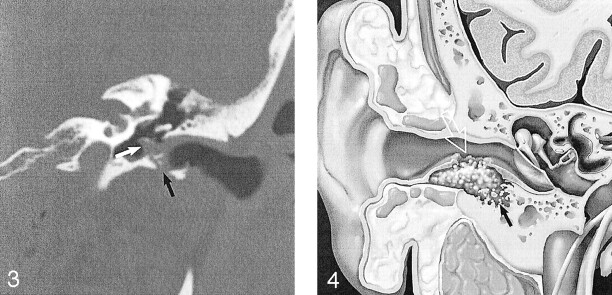

Fig 2.

EACC with intramural bone fragments. Used with permission (24).

A, Coronal temporal bone CT image shows an EACC as a soft-tissue mass in the inferior EAC with intramural bone fragments (white arrow). Erosion of the inferior wall of the EAC (black arrow) is present. Note preservation of the scutum in this 48-year-old woman with otalgia.

B, Axial temporal bone CT image in the same patient as in A shows erosion of the anterior (black arrow) and posterior (white arrow) walls of the EAC. Note the involvement of the mastoid air cells (white arrow), which requires this patient to undergo a partial radical mastoidectomy.

C, Coronal temporal bone CT image shows a soft-tissue mass filling the EAC, with associated erosion of the inferior EAC (arrow). Note the intramural bone fragments. The middle ear cavity is preserved in this 74-year-old man with otorrhea.

Fig 3.

EACC with extension into the middle ear cavity. Coronal temporal bone CT shows a soft-tissue mass in the EAC, with inferior wall erosion (black arrow) and intramural bone fragments. There is extension beyond the tympanic membrane into the middle ear cavity (white arrow). Note preservation of the facial nerve canal and scutum in this 45-year-old man with otorrhea and hearing loss. Used with permission (24).

CT findings of EACC

| Finding | Number |

|---|---|

| Soft tissue mass | 13 |

| Bone erosions | 13 |

| Position of erosion* | |

| Inferior | 8 |

| Posterior | 8 |

| Anterior | 5 |

| Superior | 2 |

| Circumferential | 2 |

| Associated findings | |

| Bony fragments | 7 |

| Middle ear extension | 5 |

| VIIn canal involvement | 2 |

| Tegmen dehiscence | 1 |

| Mastoid involvement | 4 |

May involve more than one wall of the EAC.

Discussion

A cholesteatoma is a cystic structure lined by keratinizing stratified squamous epithelium with associated periostitis and bone erosion, which is most commonly found in the middle ear cavity. Middle ear cholesteatomas may be congenital or acquired, but approximately 98% are acquired (4). Although cholesteatomas are found almost exclusively in the middle ear and mastoid, in rare cases they occur in the EAC. The estimated incidence of EACC is 0.1–0.5% of all otologic patients (1). Although EACC is rare, recognizing it as a distinct entity is important because its management is notably different from that of its clinical differential diagnoses. We attempted to determine the features of EACC that distinguish it from its clinical differential diagnoses, including neoplasms of the EAC, keratosis obturans, postinflammatory medial canal fibrosis, and necrotizing (malignant) otitis externa. In addition, the imaging characteristics important for the surgical management of EACC are identified and presented.

The exact etiology of EACC is unclear (2, 5, 6). Most cases are spontaneous or occur after surgery and/or trauma in the auditory canal, although ear canal stenosis or obstruction has also been described as a causative factor (3). In our series, EACC was more commonly spontaneous in nature, but it developed after surgery (3) or trauma (2) to the ear canal in five of 14 cases. Postoperative EACC may result from entrapment of squamous epithelial debris during the healing process (7, 8). Trauma, either canal skin lacerations or canal-wall fractures, may isolate the squamous epithelium or cause stenosis of the canal; either of these events could lead to EACC (7).

Normal epithelial migration from the tympanic membrane and EAC is an important self-cleansing property of the outer ear. Epithelial migration carries the keratin debris laterally outward from the tympanic membrane for removal (9). Spontaneous EACC has been described as a disease of the elderly due to the loss of normal migration in aging epithelium of the canal wall (3, 9). In our series of 13 patients the average age was 44 years, and the average age of our spontaneous group was 43 years; this observation suggested that an aging epithelium alone may not fully account for this lesion. Another pathophysiologic hypothesis suggests that accumulation of keratin debris induces changes of cellular proliferation in the EAC (10). Other authors described a lower than average migratory rate of epithelium in the inferior wall of the ear canal in cases of EACC. This finding suggests the cause of EACC may be partly related to abnormal epithelial migration, which leads to the local accumulation of squamous epithelium that can evolve into an EACC. In addition, the decreased migratory rate is thought to be related to a poor blood supply (9).

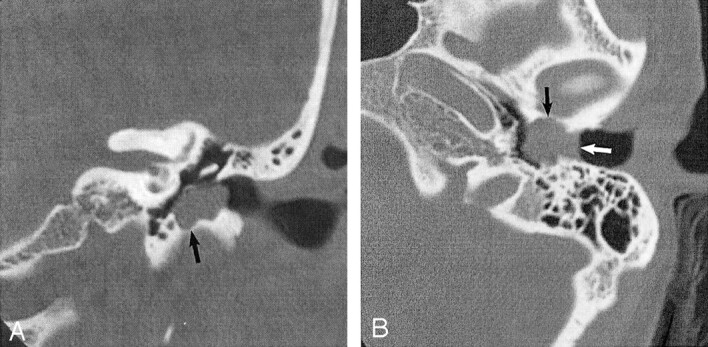

Imaging can be valuable in evaluation of EACC. However, the CT appearance of EACC is not well described in the literature. In fact, the terms keratosis obturans and EACC have often been used interchangeably (2, 11). With high-resolution temporal bone CT examination, EACC is most commonly seen as an EAC soft-tissue mass with associated bone erosion and intramural bone fragments (Fig 4). The bone erosion adjacent to the soft-tissue mass may be smooth, similar to a middle ear cholesteatoma; however, the erosion may be irregular secondary to the necrotic bone and periostitis (4). Usually, the inferior and/or posterior walls are involved (2, 12). It is important to evaluate for extension into the middle ear cavity and for integrity of the facial nerve canal, tegmen tympani, and mastoid air cells, because these features may change the surgical management. In our patient population, preoperative knowledge of facial nerve canal involvement was helpful in planning the surgical approach and in considering the use of intraoperative facial nerve monitoring. In addition, when the mastoid was involved, patients underwent a modified radical mastoidectomy to prevent the formation of an EAC-to-mastoid fistula. Also, imaging studies often reveal a mass that is considerably than that expected on clinical examination, and additional presurgical planning may be required (12, 13).

Fig 4.

Illustration of the EACC shows erosion of bone, which leaves behind intramural bone fragments (solid arrow). Note the mucosal disruption (open arrow), seen on otologic examination. Used with permission (25).

Patients with EACC usually present with otorrhea and a chronic, dull pain; less commonly, they present with hearing loss (1–3, 14). The results of our clinical review generally agreed with these characteristics, but four of our patients with EACC presented with a conductive hearing loss. This unusual hearing loss may be related to occlusion of the external canal by the plug of cholesteatoma debris (1, 2). Conductive hearing loss was described in a case report of a giant cholesteatoma of the EAC (15). The otorrhea is thought to be related to an associated localized infection by a variety of organisms, most commonly Pseudomonas aeruginosa. If very large, EACC may result in facial nerve paresis (15).

Gross pathologic analysis of EACC demonstrates extensive erosion of the bony EAC by a wide-mouthed stratified squamous keratinizing epithelial sac with a localized periostitis and sequestration of bone. The tympanic membrane is typically normal (5, 6, 16). The interface between the EACC and the bone is erosive. This erosion is thought to be related to proteolytic enzymes along the margin of the lesion produced within the cyst lining; these weaken the bone and result in periostitis and sequestration of bone. The erosion could also be partly related to the accumulation of keratin debris, which traps moisture and results in a bacterial infection that can cause ulceration of the epithelial layer and granulation tissue formation in patients who have a superimposed infection (16).

Treatment options include conservative medical therapy with frequent cleaning and debridement of the keratin debris and sequestered bone, if the entire extent of the bone erosion can be visualized and if the patient has no chronic pain (2). This procedure rarely requires general anesthesia. If the lesion does not extend into the mastoid cavity, more extensive surgery is rarely indicated. If these simple measures are inadequate to control pain and discharge, a postauricular approach may be used for more adequate debridement, canalplasty, and, usually, split-thickness skin grafting to cover the canal defect (12). When the mastoid air cells are invaded, a modified radical mastoidectomy may be indicated, with the tympanic membrane and ossicles left intact (2, 5). Spontaneous EACC is usually treated with periodic cleanings as an office procedure, whereas cases occurring as a complication of previous surgery or trauma more often violate the middle ear cavity and commonly require surgical treatment (8). Surgical treatment has been successful in relieving pain and in resolving chronic drainage (1, 2, 5, 6).

On otoscopic examination, EACC can be difficult to distinguish from other inflammatory, infective, or neoplastic processes of the EAC; examples of these include keratosis obturans, postinflammatory medial canal fibrosis, malignant otitis externa, and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). Keratosis obturans is the most closely related condition and the one most difficult to distinguish. In fact, keratosis obturans was previously considered to represent the same disease process as EACC (2). Because EACC may require surgical intervention, whereas keratosis obturans is managed medically, distinguishing these entities is important (2, 5, 6).

Patients with keratosis obturans present with acute, severe otalgia and a conductive hearing loss. Rarely, patients have associated otorrhea (3, 5, 14). Additionally, keratosis obturans generally occurs in a younger age group, it is often bilateral, and it has a definite relationship to bronchiectasis and sinusitis (2, 14). CT imaging of keratosis obturans typically demonstrates a soft-tissue plug in the bilateral EACs, without focal bone erosion of the canals (4, 14). If the canal is widened, the bone walls appear smooth, without bone fragments visible on the CT image. Imaging is rarely performed for diagnosis. Keratosis obturans pathologically appears as a dense plug of keratin debris with associated hyperplasia of the underlying epithelium, chronic inflammation of the subepithelial tissues, and a generalized widening of the bony canal (5, 6). Thus, it is the bone erosion that distinguishes EACC from keratosis obturans (2). The literature suggests that keratosis obturans is characterized by generalized canal widening, whereas EACC most often involves at least the inferior wall (1, 5, 13). We found that the EACC lesion most often involves multiple walls of the EAC, with the posterior and inferior segments most commonly affected. Circumferential involvement was also fairly common; thus, this characteristic is not conclusive in differentiating keratosis obturans and EACC.

Postinflammatory medial canal fibrosis is a distinct entity characterized by the formation of fibrous tissue in the medial bone external auditory meatus. Other terms for this lesion are acquired medial canal fibrosis, postinflammatory acquired atresia of the EAC, and postinflammatory medial meatal fibrosis (17–19). Most cases occur after chronic otitis externa and/or media or as a complication of ear surgery. On otologic examination, partial or complete fibrous obliteration of the medial part of the EAC occurs. The diagnosis is established on the basis of the history and clinical examination and audiometric findings. Imaging is usually not performed for diagnosis. Surgical management is the treatment of choice. Interestingly, EACC has been described in association with postinflammatory medial canal fibrosis in rare cases (17, 18).

Malignant otitis externa, also known as necrotizing external otitis, is a severe infectious disease involving the EAC and adjacent soft tissues; it may involve the skull base. The disease classically occurs in elderly patients with diabetes mellitus. Most cases are caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Patients typically present with severe otalgia, otorrhea, and persistent granulation tissue along the inferior aspect of the EAC at the bone-cartilage junction (4, 11, 16). The diagnosis is generally based on clinical examination findings, recovery of the offending organism, the presence of granulation tissue in the EAC, and abnormal laboratory and imaging results (20). The best imaging approach is controversial. Technetium-99m or citrate gallium-67 single photon emission CT (SPECT) have been reported to be the most sensitive studies for the initial identification of the disease (21, 22). CT has also been touted as the imaging study of choice (20, 23). CT imaging shows cortical bone erosion or an abnormality in the soft tissues beneath the temporal bone, with obliteration of the normal fat planes in the subtemporal area. Images of this disease may be indistinguishable from those of a malignancy (11, 23).

Malignant tumors of the EAC are relatively rare, with SCC being the most frequently encountered. These tumors are primarily a disease of the elderly. SCC may begin in the EAC; arise from the pinna; or, in rare cases, originate in the middle ear cavity. Secondary involvement of the EAC from regional tumor extension is much more common that primary neoplasia of the EAC. Early lesions may be mistaken for benign processes, both clinically and radiologically. Additionally, given the often-irregular bone erosion of EACC, SCC may be impossible to differentiate from EACC with imaging alone (4).

In this series, we attempted to show that the imaging features of EACC are characterized by the same pattern of a soft-tissue mass, with associated bone erosion and sequestration of bone, as seen on clinical and pathologic examination. Our findings agree with those of previous reports in that EACC is often more extensive than that suggested by the clinical findings (12). Notably, erosion may involve the middle ear cavity and the facial nerve canal (7). If the EACC extent is underestimated, the potential to cause substantial morbidity may result if the surgeon becomes disoriented during the surgical resection. Smaller lesions without middle ear, facial nerve, or mastoid involvement can be managed conservatively with frequent clinic visits for debridement rather than operative removal; however, this treatment option is often more suitable for keratosis obturans than for EACC (1, 5, 6).

Conclusion

EACC is a rare entity with characteristic imaging and clinical features. A soft-tissue attenuating mass in the EAC with erosion of adjacent bone defines the CT presentation of an EACC. Bone fragments are often present within the mass. The EACC may exhibit features including deep extension into the middle ear, mastoid, facial nerve canal, or the tegmen tympani. These findings may be unrecognized at clinical examination. These features may influence the clinical and surgical management of EACC.

Footnotes

Presented at the 39th annual meeting of the American Society of Neuroradiology Meeting, Boston, MA, May, 2001.

References

- 1.Anthony PF, Anthony WP. Surgical treatment of external auditory canal cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope 1982;92:70–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piepergerdes MC, Kramer BM, Behnke EE. Keratosis obturans and external auditory canal cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope 1980;90:383–391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Holt JJ. Ear canal cholesteatoma. Laryngoscope 1992;102:608–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Swartz JD, Harnsberger HR. The external auditory canal. In: Imaging of the Temporal Bone. 3rd ed. New York: Thieme;1998. :16–46

- 5.Shire JR, Donegan JO. Cholesteatoma of the external auditory canal and keratosis obturans. Am J Otol 1986;7:361–364 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naiberg J, Berger G, Hawke M. The pathologic features of keratosis obturans and cholesteatoma of the external auditory canal. Arch Otolaryngol 1984;110:690–693 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin DW, Selesnick SH, Parisier SC. External auditory canal cholesteatoma with erosion into the mastoid. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1999;121:298–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graham MD, Larouere MJ. Miscellaneous external auditory canal problems. In: Brackmann DE, Shelton C, Arriaga MA, eds. Otologic Surgery. Philadelphia: WB Saunders;1994. :64–68

- 9.Makino K, Amatsu M. Epithelial migration on the tympanic membrane and external canal. Arch Otorhinolaryngol 1986;243:39–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park K, Chun YM, Park HJ, Lee YD. Immunohistochemical study of cell proliferation using BrdU labeling on tympanic membrane, external auditory canal and induced cholesteatoma in Mongolian gerbils. Acta Otolaryngol 1999;119:874–879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chakeres DW, Kapila A, LaMasters D. Soft-tissue abnormalities of the external auditory canal: subject review of CT findings. Radiology 1985;156:105–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garin P, Degols JC, Delos M. External auditory canal cholesteatoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1997;123:62–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Malcolm PN, Francis IS, Wareing MJ, Cox TC. CT appearances of external ear canal cholesteatoma. Br J Radiol 1997;70:959–960 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tran LP, Grundfast KM, Selesnick SH. Benign lesions of the external auditory canal. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1996;29:807–825 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sapci T, Ugur G, Karavus A, et. al. Giant cholesteatoma of the external auditory canal. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 1997;106:471–473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Applebaum EL, Duff BE. Ear and temporal bone, I: clinical considerations for non-neoplastic lesions of the ear and temporal bone. In: Fu YS, Wenig BM, Abemayor E, Wenig BL, eds. Head and Neck Pathology with Clinical Correlations. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone;2001. :668–678

- 17.El-Sayed Y. Acquired medial canal fibrosis. J Laryngol and Otol 1998;112:145–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker BC, Tos M. Postinflammatory acquired atresia of the external auditory canal: treatment and results of surgery over 27 years. Laryngoscope 1998;108:903–907 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slattery WH, Sadat P. Post-inflammatory medial canal fibrosis. Am J Otol 1997;18:294–297 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grandis JR, Curtin HD, Yu VL. Necrotizing (malignant) external otitis: prospective comparison of CT and MR imaging in diagnosis and follow-up. Radiology 1995;196:499–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mendelson DS, Som PM, Mendelson MH, Parisier SC. Malignant external otitis: the role of computed tomography and radionuclides in evaluation. Radiology 1983;149:745–749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stokkel MP, Takes RP, van Eck-Smit BL, Baatenburg de Jong RJ. The value of quantitative gallium-67 single-photon emission tomography in the clinical management of malignant external otitis. Eur J Nucl Med 1997;24:1429–1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Curtin HD, Wolfe P, May M. Malignant external otitis: CT evaluation. Radiology 1982;145:383–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harnsberger HR. Head and Neck Digital Teaching File. Copyright 2002, Electronic Medical Education Resource Group

- 25.Harnsberger HR. Head and Neck Image Archive. Accessed March2002. . Advanced Medical Imaging Reference Systems, Salt Lake City, UT