Abstract

Summary: Few reports of temporary disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) following neurointerventional procedures, presumably caused by nonionic radiographic contrast medium (CM), exist in the literature. We described such a case in a 72-year-old man presenting with acute subarachnoid hemorrhage, who underwent coil embolization of a ruptured anterior communicating artery complex aneurysm. At the time of his follow-up CT examination, a large amount of iodine was found in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). Because of this experience, the iodine concentration in the CSF of five other patients who also underwent an intracranial endovascular procedure was measured. It was concluded that this increased iodine might have been caused by temporary leakage or breakdown of the BBB. Even if the total amount of CM may not be excessive, the disproportionately high concentration injected into a single vascular territory may pose a unique set of variables increasing the risk of BBB disruption.

Nonionic iodinated contrast medium (CM) is widely used for cerebrospinal angiography and intravascular neurointerventional procedures. The frequency of serious side effects thought to be caused by CM has been reported to be a relatively rare occurrence (1–4). Several clinical cases with minor complications suspected to be related to nonionic CM, however, have been reported previously. CT findings of abnormal enhancement in the cerebral cortex following angiography have been reported; abnormal imaging findings coincide with temporary neurologic deficits attributable to disruption of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and have been thought to be related to the use of nonionic CM (1–3, 5–7).

Case Report

A 72-year-old male patient initially experienced the rapid onset of a severe headache. Over the following day, his headache became progressively more severe, so that the patient presented to an outside hospital. After the diagnosis of subarachnoid hemorrhage was confirmed on the basis of CT findings, the patient was transferred to our hospital (Fig 1A). Routine transfemoral digital subtraction angiography (DSA) was performed. During angiography, a ruptured anterior communicating complex aneurysm was identified. The saccular aneurysm carried a daughter dome, and the aneurysm overall measured 4 × 4 × 7 mm. At the time of diagnosis, the geometry of the aneurysm was judged to be suitable for either surgical or endovascular treatment. Both options were offered to the patient’s family, who chose endovascular treatment consisting of Guglielmi detachable coil (GDC) placement. A 6F cerebral guiding catheter was placed in the left internal carotid artery via a transfemoral approach. The interventional procedure was performed under general anesthesia. Although an intravenous loading bolus of heparin was not administered, all catheters and the introducer sheath were connected with the continuous antegrade heparinized saline flush, with control and monitoring of the activated clotting time used to oversee the amount of administered heparin. We used a total of 260 mL of nonionic CM (Iopamidol 300 mgI/mL; 600–700 mOsm/kg) for both the diagnostic and interventional portions of the procedure over an approximate 4-hour course. Postoperative control angiography showed total occlusion of the aneurysm sac, and the patient’s vital signs remained stable during embolization. The volume of CM (≈180 mL) was administered into the left internal carotid artery; this was the vessel through which the aneurysm was treated. The aneurysm coil embolization was performed under continuous road mapping, and at no point during the procedure was there demonstrated excursion of the microcatheter, coil mass, or microwire outside of the confines of the vascular compartment to imply perforation. Similarly, at no time during the embolization was CM staining appreciated. Immediate postprocedural CT was performed, and this study demonstrated marked enhancement throughout the left cerebral cortex and left basal ganglia, with concordant diffuse swelling of the left cerebral hemisphere (Fig 1B). CT did not demonstrate any appreciable increase in the amount of the subarachnoid hemorrhage. At this time, a lumbar drainage catheter was placed, and a representative sample of the patient’s CSF was obtained and sent for CSF analysis. The CSF was pink in color and did not contain fresh, gloss blood. General anesthesia was ceased, and the patient demonstrated new deficits consisting of right hemiparesis and slight motor aphasia. The diagnosis at this point included BBB disruption due to CM. Follow-up CT was performed approximately 11 hours after the first CT examination, with only residual swelling of the left cerebral hemisphere shown on the new comparison CT scan with interval resolution of the region of high attenuation and enhancement (Fig 1C). The neurologic symptoms resolved in the postprocedural week, and the patient was discharged from our hospital without residual neurologic deficits 2 weeks later.

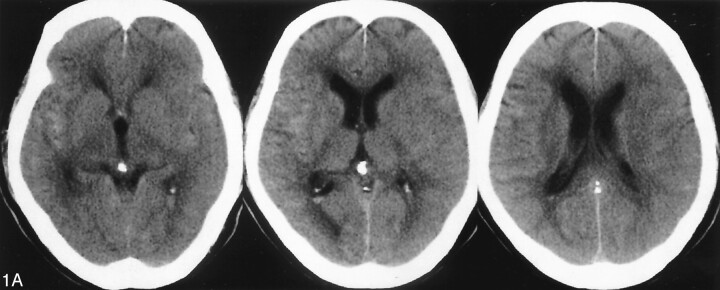

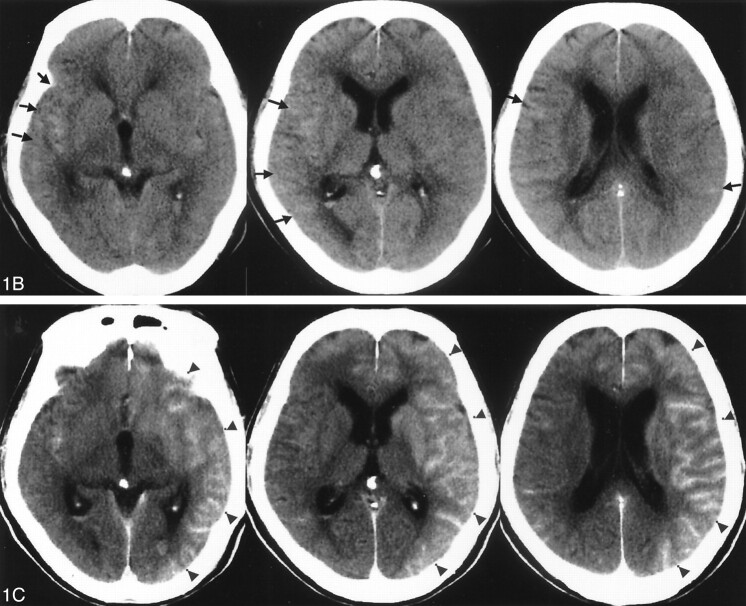

Fig 1.

A 72-year-old man presented with subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to a ruptured anterior communicating artery complex aneurysm. The patient underwent primary endovascular coil treatment of the aneurysm to occlusion.

A, Pretreatment CT scan showing hyperattenuated area mainly in the right Sylvian fissure (arrow).

B, Postprocedural CT scan, obtained 1 hour after the procedure, demonstrating extensive gyriform enhancement of the cerebral cortex, significantly greater on the left (arrowhead).

C, Follow-up CT scan, obtained 11 hours after the procedure, demonstrates resolution of the previously demonstrated gyriform cortical enhancement, with only slight diffuse vasogenic edema shown in the left cortical mantle.

Patients and Methods

We described our single case in which an abnormally increased measured iodine concentration in the CSF was noted. The measurement of the elevated iodine concentration in our patient’s CSF was performed with spectrophotometry, following centrifugation and filtration of the CSF after performing protein removal processing in 0.5 n-perchlorate acid (8, 9). Following our initial experience with the above-described patient, we performed similar iodine concentration assessments with the CSF of four consecutive patients who similarly underwent interventional procedures following subarachnoid hemorrhage (Table).

Patient characteristics

| Case | Age | Sex | Location | H&K Gradea | Fisher’s Groupb | Hctc (%) | Blood Pressured (max/min) | Operation Time (min) | Total Amount of CM (mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 72 | M | AcomA* | 2 | 2 | 39.6 | 140/81 | 140 | 190 |

| 2. | 51 | F | AcomA | 3 | 3 | 35.2 | 115/68 | 184 | 160 |

| 3. | 41 | M | AcomA | 3 | 4 | 34.5 | 120/74 | 170 | 190 |

| 4. | 17 | M | IC-PC** | 5 | 4 | 42.9 | 155/99 | 193 | 220 |

| 5. | 47 | F | AcomA | 4 | 3 | 36.3 | 160/80 | 220 | 180 |

, Hunt & Kosnik classification;

, Fisher’s CT classification;

, Hematocrit;

, Maximum measurement during an operation;

, anterior communicating artery;

, internal carotid artery-posterior communicating artery.

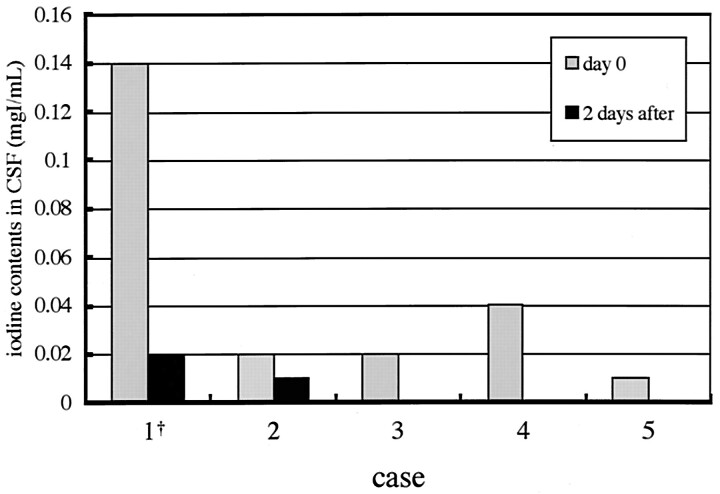

The spectrophotometrically determined iodine content in the CSF of our discussed patient was 0.14 mgI/mL and decreased to 0.02 mgI/mL 2 days later. Following our experience with the described patient, we obtained CSF of four additional patients undergoing uncomplicated coil embolization in our hospital (Table). They did not demonstrate any similar neurologic events or abnormal CT findings postprocedurally, which would have implied BBB alteration. As a result, it was recognized that our above-described patient showed an exceedingly high concentration of CSF iodine when compared with the other four patients (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

The comparison of iodine contents in CSF for the five cases. Patient 1 (†) is the presented case.

Discussion

Following cerebral angiography or cerebroarterial embolization, there have been rare reports of CT findings of abnormal enhancement of the cerebral cortex, in addition to temporary neurologic deficits due to disruption of the BBB related to nonionic CM (5, 6, 10). In the presented patient demonstrating the described hyperattenuating cortical CT abnormality, it was shown that the CSF included a large quantity of iodine. This high concentration of iodine may represent supportive evidence of temporary leakage or breakdown of the BBB, especially when considered in concert with the regionally referable reversible neurologic syndrome that ultimately resolved completely. There was no sign of cerebral ischemia, such as was proved by a recent report that showed no abnormality on diffusion-weighted MR images (1, 2).

According to the previous related literature, such findings have been explained on the basis of temporary disruption of the BBB by hyperosmolality and chemotoxicity of CM (3–21). The alteration of the BBB by the CM can be explained osmotically; it is hypothesized that hypertonic solutions draw water out of the endothelial cells of brain vessels, causing the cells to shrink and separating the tight junctions (14). The severity of the barrier disturbance is questionably related to the chemotoxic action (15). Alternatively, other reports explain the BBB breakdown on the basis of microvascular sludging and possibly arterial spasm (7, 11, 20, 22). In two instances, BBB disruption has been observed in cases performed with hypertonic nonionic CM, with solution of higher viscosity than blood, which is thought to be a consequence of an acute hypertensive episode during angiography (6, 16). Additional contributory variables have been hypothesized; direct administration or overdosage into the carotid arteries in high concentration, associated with an increased CM bolus transit time with a prolonged duration of contact with the endothelium, has been related to disruption of the BBB, with associated severe neurologic side effects (11, 14, 23).

In neurointerventional procedures, the CM is injected frequently into a single vessel. As such, even if the total amount of CM is not excessive, these respective injections may be a causative factor in BBB disruption. It is clear that the analysis of BBB breakdown is complex, multifactorial, and clinically significant. The challenge in more fully explaining the variable contributions to BBB breakdown may therefore hinge, to a large degree, on carefully controlled experimental studies.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the colleagues of Nippon-Schering, Osaka, Japan, for their help with preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Mentzel HJ, Blume J, Malich A, et al. Cortical blindness after contrast-enhanced CT: complication in a patient with diabetes insipidus. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2003;24:1114–1116 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Velden J, Milz P, Winkler F, et al. Nonionic contrast neurotoxicity after coronary angiography mimicking subarachnoid hemorrhage. Eur Neurol 2003;49:249–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sticherling C, Berkfield J, Auch-Schwelk W, Lanfermann H. Transient bilateral cortical blindness after coronary angiography. Lancet 1998;351:570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Earnest FIV, Forbes G, Sandok BA, et al. Complications of cerebral angiography: prospective assessment of risk. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1983;4:1191–1197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Numaguchi Y, Fleming MS, Hasuo K, et al. Blood-brain barrier disruption due to cerebral arteriography: CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1984;8:936–939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Okazaki H, Tanaka K, Shishido T, et al. Case report: disruption of the blood-brain barrier caused by nonionic contrast medium used abdominal angiography: CT demonstration. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1989;13:893–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Horowitz NH, Wener L. Temporary cortical blindness following angiography. J Neurosurg 1974;40:583–586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Matsuda I, Handa J, Handa H, et al. The measurement of extravascular iodine in contrast enhancement on computed tomography. Progr Comput Tomogr 1980;2:21–24 [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kan M, Kashiwagi H, Terao T, et al. Determination of iodaxamic acid (BC-17) in biological material. J Takeda Res Lab 1974;33:87–95 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuhn MJ, Burk TJ, Powell FC. Unilateral cerebral cortical and basal ganglia enhancement following overdosage of nonionic contrast media. Comput Med Imag Graph 1995;19:307–311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Junk L, Marshall WH. Fatal brain edema after contrast-agent overdose. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1986;7:522–525 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sage MR. The blood-brain barrier: a phenomenon of increasing importance to the imaging clinician. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1982;138:887–898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Junck L, Marshall WH. Neurotoxicity of radiological agents. Ann Neurol 1983;13:469–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rapoport SI, Thompson HK, Bidinger JM. Equi-osmoral opening of the blood-brain barrier in the rabbit by different contrast media. Acta Radiol (Stockh) 1974;15:21–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Salvesen S, Nilsen PL, Holtermann H. Effect of calcium and magnesium ions on the systemic and local toxicities of the n-methylgulucamine (meglumine) salts of metrizoic acid (Isopaque). Acta Radiol 1967;270:180–193 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whisson CC, Wilson AJ, Evill CA, Sage MR. The effect of intracarotid nonionic contrast media on the blood-brain barrier in acute hypertension. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1994;15:95–100 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lentos G. Cortical blindness due to osmotic disruption of the blood-brain barrier by angiographic contrast material: CT and MRI studies. Neurology 1989;39:567–571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Wispelarer JF, Trigaux JP, Van Beers B, Gillard C. Cortical and CSF hyperdensity after iodinated contrast medium overdose: CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1992;16:998–1003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levey AI, Weiss H, Yu R, et al. Seizures following myelography with iopamidol. Ann Neurol 1988;23:397–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakai Y, Hyodo A, Okazaki M, et al. Transient cortical blindness and convulsion mimicking a hemorrhagic complication during embolization of the cerebellar AVM. Neurol Med Chir 1999;27:249–253 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johansson BB. Hypertension and the blood-brain barrier. In: Neuwelt EA, ed. Implications of the blood-brain barrier and its manipulation. Vol. 2 New York: Plenum;1989. :289–410 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson A, Stewart G, Wood A, Gillespie JE. Transient global amnesia and cortical blindness after vertebral angiography: further evidence for the role of arterial spasm. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1995;16:955–959 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.d’Avella D, Cicciarello R, Albiero F, et al. Effect of intracarotid injection of iopamidol on local cerebral glucose utilization in rat brain. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1989;10:797–801 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]