Abstract

A cancer diagnosis requires significant information to facilitate health care decision making, understand management options, and health care system navigation. Patient knowledge deficit can decrease quality of life and health care compliance. Surveys were distributed to attendees of the Mayo Clinic “Living with and Surviving Cancer” patient symposium January 2015. Follow-up survey was sent to participants 3 months after the symposium. Surveys included demographic data and patient-reported disease comprehension, symptom burden, desired information, and quality-of-life assessment.

Demographics:

113 patients completed the pre-intervention survey. Average age was 64.7 years. Disease types included hematologic (N = 50) and solid malignancies (N = 77). Most patients self-reported adequate baseline understanding of their disease (80 %), screening tests (74 %), and monitoring tools (72 %). Lowest knowledge topics were legal issues (13 %) and pain management (35 %).

Pre- and post-analysis:

79 of the initial 113 participants completed both surveys. In the post-symposium setting, durable knowledge impact was noted in disease understanding (pre 80 % vs post 92 %), treatment options (pre 60 % vs post 76 %), nutrition (pre 68 % vs post 84 %), and legal issues (pre 15 % vs post 32 %). Most patients desired increased understanding regarding disease, screening tests, nutrition, and stress and fatigue management. The level of desired information for these topics decreased in the post-symposium setting, statistically significant decrease noted in 4 of 5 topics assessed. Knowledge needs and deficit in cancer care range from disease-specific topics, social stressors, and health care navigation. A cancer patient-centered symposium can improve patient-reported knowledge deficit, with durable responses at 3 months, but patient needs persist.

Keywords: Quality of life, Cancer symposium, Cancer education, Educational intervention, Patient education, Cancer survivorship, Survivorship, Patient knowledge

Introduction

The diagnosis of cancer results in exposure to large amounts of data and requires assimilation of that information to facilitate decision making [1]. The information disclosure can include cancer type, treatment options, and prognosis. Additionally, the medical decision-making process can include concerns of work responsibilities, family relationships, and financial concerns. Most patients with a cancer diagnosis report seeking out cancer-specific information and, compared to individuals without a cancer diagnosis, report a more negative experience during the information-gathering process [2]. Not being able to obtain health information or being unable to fully understand health information can lead to poor medical outcomes [3, 4]. Providing information to patients with a diagnosis of cancer has been shown to be beneficial in terms of patient satisfaction, stress management, improved mood, improved coping ability, and improved communication with patient’s family [5].

The discrepancy between patient knowledge and the level of knowledge they desire, or the level they believe they need, is called knowledge deficit. Patients with cancer demonstrate a significant knowledge deficit. This knowledge deficit persists from diagnosis into post-treatment phase, as one study in long-term cancer survivors reported information needs that were associated with negative-impact mental and physical function [6]. One study in England assessed information preferences in 101 cancer patients; revealed 94 % of patients desired as much information as possible, regardless of the positive or negative nature of the information [7]. While patients demonstrate an individualized desire of information, there is also evidence that the level of knowledge needs can persist over time [8] as cancer status evolves.

Knowledge is important to cancer patients, but much like the hope of cancer treatment in the future, the provision of knowledge to cancer patients should be personalized. Assessing patient knowledge level, sources of information, and desire for additional information may help the health care system identify types and modes of patient information.

The desire to better understand the spectrum of cancer patient knowledge experience prompted this study. We developed a comprehensive patient-centered conference (Living with and Overcoming My Cancer [LWC]: A Mayo Clinic Symposium for Patients and Loved Ones) with 8 hours (h) of general information sessions and 4-h disease-specific breakouts. This study was approved by the Internal Review Board of Mayo Clinic Arizona. Patients agreed to participation through written informed consent. Through voluntary questionnaires, we studied the impact of this cancer symposium on cancer-specific knowledge, information preferences, quality of life, and symptom management among cancer patients.

Methods

Symposium

The patient symposium was composed of a 2-day educational conference including 8 h of general cancer education sessions (topics: immunity, imaging, empowerment, nutrition, survivorship, communication, integrative medicine, and legal concerns) with presenters from medical oncology, pharmacy, nursing, and complementary and integrative medicine (see Table 1). Additionally, a 4-h disease-specific breakout session allowed individuals to participate in disease-specific education (diagnosis, treatment, future directions), as well as a question-and-answer session with physicians specialized in the particular disease (breast cancer, lung cancer, genitourinary cancer, colorectal cancer, melanoma, ovarian and uterine cancer, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, lymphoma, myeloma and amyloidosis, acute leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome, and myeloproliferative neoplasms and pancreatic cancer).

Table 1.

Living with and overcoming cancer conference topics

| Study population | Topic | Questionnaires |

|---|---|---|

| All Participants | Immune System and Cancer Radiologic Imaging The Patient Role Nutrition Cancer Survivorship Bedside Lessons Healthcare Communications Legal, Employment, Insurance Integrative Medicine |

• European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) • Disease Specific Questionnaire • Control Preference Scale • Linear Analog Self-Assessment Score |

| Disease Specific Breakout Sessions | Breast Cancer Lung Cancer Genitourinary Colorectal Melanoma Ovarian and Uterine Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia Lymphoma Myeloma and Amyloidosis Acute Leukemia, Myelodysplastic syndrome, Myeloproliferative Neoplasm Pancreatic Cancer |

|

| Optional Breakout Sessions | Physical Activity Caregivers Resiliency |

Patient Selection

Surveys were distributed to attendees of the Mayo Clinic “Living With and Overcoming My Cancer” patient symposium prior to their arrival in January 2015. Surveys were sent via mail to all registered attendees 1 week prior to the symposium, and additional surveys were available on site before the conference. While many attendees were accompanied by familial or friend support, only individuals diagnosed with a malignancy, currently or previously, were asked to return the questionnaires.

Data Measurement

Surveys included the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30), the control preference scale assessing preference regarding the medical decision-making role, and the linear analog self-assessment score evaluating symptoms experienced in the previous week. Additionally, a questionnaire of 50 questions pertaining to understanding of disease (assessed using response options of not at all, a little, quite a bit, and very much), sources of information, and knowledge desired was developed specifically for this conference based on the conference lecture topics (see Table 1). The survey responses represented patient self-reported understanding, symptom burden and additional knowledge desired.

The level of knowledge reported by patients was termed sufficient, or high, if they endorsed >70 % “quite a bit” or “very much” understanding on a particular topic. The level of knowledge was termed moderate if 50–70 % of respondents endorsed “quite a bit” or “very much” understanding on a particular topic. Similarly, the level of knowledge was termed poor, or lacking, if <50 % of respondents endorsed “quite a bit” or “very much” understanding on a particular topic.

Data Collection

Patients completed this set of questionnaires prior to completion of the symposium. At 3 months, the patients who completed the initial set of questionnaires were sent a follow-up set of questionnaires composed again of the EORTC-QLQ-C30, control preference scale, linear analog self-assessment, and disease-specific knowledge questionnaires.

Data Analysis

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Arizona Institutional Review Board. Changes over time were assessed using McNemar’s tests and paired t tests for categorical and continuous variables, respectively.

Results

Patients

Of the 650 registered attendees, 113 attendees completed the pre-convention survey and 79 of those completed the post-convention survey.

Demographics

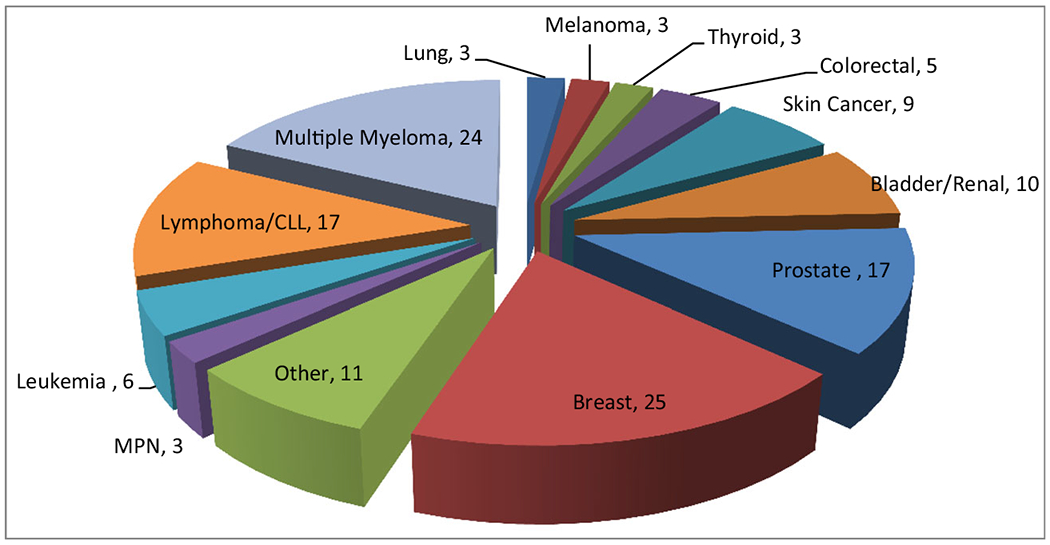

Of the 113 original participants, the mean age was 64.7 years, with a range from 34 to 87. There was a slight female predominance (55.4 %). A third of participants reported attending a cancer symposium previously (37 %) (see Table 2). Disease types represented included hematologic malignancies (N = 50), specifically multiple myeloma (N = 24), lymphoma (N = 17), leukemia (N = 6), myeloproliferative neoplasm/myelodysplastic syndrome (MPN/MDS) (n = 3), and solid tumor malignancies (N = 77) including breast (N = 22), prostate (N = 17), bladder/renal cancer (N = 10), colorectal (N = 5), thyroid (N = 3), lung (N = 3), melanoma (N = 3), and others (N = 11) (see Fig. 1). Some patients reported more than one malignancy (N = 15).

Table 2.

Patient demographics

| Demographic | Pre-intervention participants | Post-intervention participants |

|---|---|---|

| Number of participants | 113 | 79 |

| Age (years, mean) | 64.7 | 65.9 |

| Male gender (%) | 50 (45) | 36 (46) |

| Time since diagnosis | ||

| 6 months–1 year | 15 (13) | 10 (13) |

| 1 year–3 years | 50 (44) | 32 (41) |

| >3 years | 54 (48) | 41 (52) |

| Prior cancer symposium attendance (Yes, %) | 41 (37) | 36 (46) |

| Previous treatment | ||

| Surgery | 65 (58) | 41 (52) |

| Chemotherapy | 70 (62) | 43 (54) |

| Radiation | 40 (35) | 27 (34) |

| Hormonal therapy | 18 (16) | 11 (14) |

| None | 9 (8) | 9 (11) |

| Current treatment | ||

| Surgery | 1 (1) | 11 (1) |

| Chemotherapy | 25 (22) | 19 (24) |

| Radiation | 6 (5) | 3 (4) |

| Hormonal therapy | 14 (12) | 7 (9) |

| None | 51 (45) | 37 (47) |

Fig. 1.

Baseline cancer types represented

Most patients were >1 year from a cancer diagnosis (N = 104). A majority of patients had utilized surgery (n = 65) and chemotherapy (N = 70) for cancer treatment.

Baseline

Knowledge

A majority of patients reported sufficient baseline understanding of their disease (80 %), screening tests (74 %), and monitoring tools (72 %) (see Fig. 2). The lowest knowledge levels reported were topics of pain management (35 %), disease relapse symptoms (45 %), end of life decision making (46 %), fatigue management (48 %), and financial considerations of disease and treatment (49 %). A high level of increased understanding was desired in 4 of the 5 topics assessed (>70 % participants reporting “very much” or “quite a bit”) including disease understanding (77 %), nutrition (64 %), screening tests (81 %), and fatigue management (70 %) while 68 % of participants reported a desire for increased understanding of stress management.

Fig. 2.

Baseline level of knowledge (N = 113)

Health Care Team

Forty-two percent of participants believed that their primary care provider was informed of their oncology plan (N = 48). A majority reported comfort discussing treatment options with the health care team (N = 97). In regards to reporting pain to health care team, 21 % of respondents never reported pain (N = 20); 25 % reported pain “a little” (N = 24); 26 % reported pain “quite a bit” (N = 25); and 27 % reported pain very much (N = 26). If a participant experienced pain but did not report it to the oncology team, it was reportedly due to pain not being severe (N = 49, 43 %), patient being able to handle the pain “on my own” (N = 41, 36 %), a desire to not receive pain medication (N = 21,19%), or pain be expected during cancer treatment (N = 17, 15 %).

Disease Impact

Most patients reported the highest level of stress following diagnosis (N = 76) while the highest level of fatigue was during treatment (N = 56). Attempts to manage stress included exercise (N = 73), spirituality or prayer (N = 65), anxiety medication (N = 24), and met with a psychologist or psychiatrist (N = 17). Similarly, attempts to manage fatigue included exercise (N = 73) and prayer/spirituality (N = 49). Nearly one-third of participants reported no negative financial impact from cancer diagnosis or cancer care (N = 31), with 10 % of respondents reporting a high level of negative financial impact (N = 11).

Symposium Impact at 3 Months

Seventy-nine patients (70 % of respondents) who completed the pre-symposium survey also completed the post-symposium survey. Baseline characteristics were similar for the overall cohort and the sub-group who returned post-symposium surveys.

Durable Knowledge Response

A durable response was noted regarding level of patient-reported knowledge. An improvement in 15 of 18 topics assessed for knowledge level was seen (see Fig. 3). Statistical improvement was noted in reports of “quite a bit” or “very much” understanding nutrition (pre N = 49, 68 %, post N = 66, 84 %, p value = <0.05); treatment options (pre N = 47, 60 %, post N = 60, 76 %, p value < 0.05); and disease understanding (pre N = 62, 80 %, post N = 71, 92 %, p value = <0.05). Statistical improvement was noted in knowledge of legal issues regarding disease and treatment (pre N = 11, 15 %, post 24, 32 %, p value = <0.05).

Fig. 3.

Patient Reported Knowledge Improvement at Three Months

Improved knowledge in the post-symposium setting demonstrated by the increased level of understanding from low (<50 % respondents endorsing very much or quite a bit understanding) to moderate, or from moderate level of knowledge (50–70 % respondents endorsing very much or quite a bit understanding) to sufficient (>70 %), though not statistically significant. The two topics that demonstrated an improvement from low level of knowledge to moderate were disease risk factors (pre N = 49 %, post N = 56 %, p value 0.56) and disease relapse symptoms (pre N = 45 %, post N = 54 %, p value 0.27). Topics that demonstrated an improvement from moderate level of knowledge to sufficient included recurrence monitoring (pre N = 62 %, post N =72 %, p value 0.19), stress management (pre N = 60 %, post N = 71 %, p value = 0.12), and treatment options and nutrition both of which improved by a significant amount (p value < 0.05).

Knowledge Deficit

The post-symposium data demonstrated decreased desire for each of the five topics assessed regarding desired information delivery. In the pre-symposium setting, 54 (72 %) participants reported “quite a bit” or “very much” desire for increased understanding of managing fatigue, while in the post-symposium setting, this number decreased to 42 (54 %) (p value <0.05). Significant decrease in the level of desire for additional information or understanding was reported in four of the five topics assessed: stress management (post 51%, pre 65 %, p value <0.05), nutrition (post 70 %, pre 84 %, p value <0.05), and disease screening tests (post 54 %, pre 72 %, p value <0.05). There was no significant difference between the pre- and post-symposium desire for increased disease information (post 70 %, pre 77 %, p value 0.48) (see Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Knowledge deficit in the pre- and post-symposium setting

Symptoms and Quality of Life

The change in the linear analog self-assessment score demonstrated no significant difference in the pre- and post-symposium patient reports. Similarly, there was no significant difference in functioning of patients pre- or post-symposium based on EORTC. There was a significant improvement in reported appetite loss (mean change 5.5, p value 0.03).

Discussion

We identified the unique opportunity that a live patient-centered cancer conference can provide to a broad population of cancer patients with respect to self-reported knowledge level and knowledge needs. This 2-day symposium, utilizing a combination of general sessions and smaller disease-specific breakout sessions, provided a wide range of topics from diagnosis and treatment, to health care navigation and legal resources and end-of-life care. This study demonstrates a moderate to high level of patient knowledge of a majority of the topics assessed. The topics found to have the least level of knowledge at baseline can be described as directly related to disease, such as symptom management (pain or fatigue), or indirectly related to disease, such as financial or legal considerations of disease or making end-of-life decisions.

The topics with the highest level of knowledge reported at baseline can be described as directly related to disease including monitoring tools, screening tests, and the disease itself. It is likely that these are the topics most frequently discussed between patient and health care professional. Additionally, these topics remain fairly constant from diagnosis through treatment, meaning the type of surveillance laboratory or imaging study remains consistent. This suggests that health care providers likely devote most of the patient encounter to discussing the specific disease and the results of the monitoring tools, either labs or imaging. The other aspects of cancer care are likely discussed less consistently, such as nutrition, treatment options, or symptom management, and likely reflect the patient’s physical exam or particular questions. This highlights the complexity of cancer care and the limitations that physicians have to provide comprehensive cancer information. There is a need to strengthen existing networks of allied health providers and to broaden the distribution of information to patients and families. Additionally, there is a need to create novel methods of health care information delivery to augment the limitations of time and expertise for various health care team members. This patient-centered cancer care conference appears to be a novel method of health care information delivery.

When the information needs are not met by the health care provider, patients seek additional resources. The Internet is a major source of cancer-related information, with one study indicating 54 % of patients with head and neck cancer acquiring information regarding treatment and health maintenance from online sources [9]. One study classified the Internet impact on cancer care for patients as providing an avenue for communication, creating or identifying community, providing disease and health-related content, and connecting to opportunities for e-commerce [10].

Factors that influence access and utilization of cancer-related information include race, ethnicity, and age. Race and ethnicity can influence access to, exposure to, and utilization of medical information [1, 11] and lead to lower levels of cancer knowledge [12, 13]. In addition to ethnicity, one study in elderly cancer patients demonstrated education level and cognitive status as independent factors in survival [14], which likely impacts socioeconomic status which can impact overall survival, but also demonstrates that ability to seek, assimilate, and utilize health information in the complex cancer care system may impact survival. In addition to investigating the information needs and knowledge levels of cancer patients in general, the health care system must continue to identify personal as well as population-specific information needs and challenges.

Interestingly, even when this study’s participants reported a high level of understanding in a particular topic, the desire for increased understanding in that topic was higher. This suggests that cancer care is complicated for patients, and even when patients feel they understand a part of it, there remains a concern that there is more to learn. In some ways, some patients appear to have an unquenchable thirst of knowledge. These may be the patients that self-select to go to a patient-centered symposium, but it also likely represents a portion of the population that seeks to be informed and capable to make decisions. As physicians remain limited by time, and expertise in the spectrum of cancer care delivery, we must identify effective modes of providing information and reassurance to patients seeking to gain and to improve their knowledge.

One limitation of this study is the data assessed and evaluated patient-reported knowledge level and needs, which does not necessarily correlate with a consistent ability to make health care decisions. This study did not seek to correlate patient-reported knowledge level to a quantitative assessment of disease comprehension, though this would be an interesting topic for future studies. Another limitation of this study is the potential for a patient selection bias as individuals who choose to participate in a patient-centered symposium are, by definition, seeking information and may have a higher desire for information than a more general cancer patient population. Additionally, as registration for the symposium required an enrollment fee, the studied patient population may demonstrate higher socioeconomic means than a more general cancer population. Similarly, a 2-day course may not be practical for many patients, based on transportation, employment status, or caregiver needs. Another limitation is the heterogeneous nature of the study population, including any cancer type, any time since diagnosis, and any treatment history, which may contribute to the lack of symptom or quality of life improvement at 3 months due to the fact that cancer status was not controlled.

This study demonstrated that cancer patients who report at least a moderate level of knowledge continue to report high information needs, indicating a high knowledge deficit. The knowledge deficit in cancer can persist despite attempts to improve patient education. This study illustrates the ability to improve both patient-reported knowledge and knowledge deficit with a patient-centered cancer symposium.

Acknowledgments

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Internal Review Board.

Footnotes

Preliminary data presented as Abstract Only at 20th Congress of European Hematology Association Annual Meeting, Vienna, Austria, June 2015

Study presented at American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting Orlando, Florida, USA December 2015

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimers There are no financial disclosures, conflicts of interest, and/or acknowledgements from the authors, and/or no funding sources for the manuscript.

References

- 1.Polacek GN, Ramos MC, Ferrer RL (2007) Patient Educ Couns 65:158–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roach AR, Lykins EL, Gochett CG, Brechting EH, Graue LO, Andrykowski MA (2009) J Cancer Educ : Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ 24:73–79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baker DW, Wolf MS, Feinglass J, Thompson JA, Gazmararian JA, Huang J (2007) Arch Intern Med 167:1503–1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dewalt DA, Pignone MP (2005) Am Fam Physician 72:387–388 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Degner LF, Davison BJ, Sloan JA, Mueller B (1998) J Nurs Meas 6:137–153 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beckjord EB, Arora NK, McLaughlin W, Oakley-Girvan I, Hamilton AS, Hesse BW (2008) J Cancer Survivorship: Res Pract 2:179–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fallowfield L, Ford S, Lewis S (1995) Psycho-Oncology 4:197–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison DE, Galloway S, Graydon JE, Palmer-Wickham S (1999) Rich-van der Bij L. Patient Educ Couns 38:217–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rogers SN, Rozek A, Aleyaasin N, Promod P, Lowe D (2012) Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg 50:208–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eysenbach G (2003) CA Cancer J Clin 53:356–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA (2004) Am J Public Health 94:2084–2090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gany F, Yogendran L, Massie D, Ramirez J, Lee T et al. (2013) J Cancer Educ: Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ 28:165–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Costas-Muniz R, Sen R, Leng J, Aragones A, Ramirez J, Gany F (2013) J Cancer Educ: Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ 28:458–465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Goodwin JS, Samet JM, Hunt WC (1996) J Natl Cancer Inst 88: 1031–1038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]