Abstract

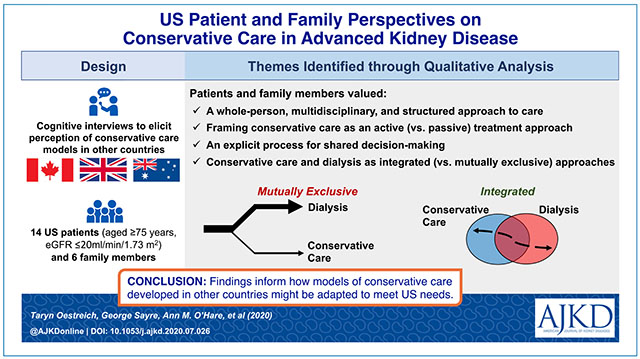

Rationale & Objective:

Little is known about perceptions of conservative care among patients with advanced kidney disease in the United States.

Study Design:

Qualitative study using cognitive interviewing about attitudes regarding conservative care using decision aids on treatments for advanced kidney disease developed outside the United States.

Setting & Participants:

14 patients 75 years or older with advanced kidney disease, defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate ≤ 20 mL/min/1.73 m2 and not receiving maintenance dialysis, and 6 of their family members.

Analytical Approach:

Thematic analysis of participants’ reactions to descriptions of conservative care taken from various clinical care decision aids.

Results:

Participants were mostly White (n = 15) and had at least some college education (n = 16). Four themes emerged from analysis of interviews: (1) core elements of conservative care: aspects of conservative care that were appealing to participants included a whole-person, team-based, and structured approach to care that focused on symptom management, maintaining current lifestyle, and managing health setbacks; (2) importance of how conservative care is framed: participants were more receptive to conservative care when this was framed as an active rather than passive treatment approach and were receptive to statements of uncertainty about future course of illness and prognosis; (3) an explicit approach to shared decision making: participants believed decisions about conservative care and dialysis should address considerations about risk and benefits of treatment options, family and clinician perspectives, and patients’ goals, values, and preferences; and (4) relationship between conservative care and dialysis: although conservative care models outside the United States are generally intended to serve as an alternative to dialysis, participants’ comments implied that they did not see conservative care and dialysis as mutually exclusive.

Limitations:

Themes identified may not generalize to the broader population of US patients with advanced kidney disease and their family members.

Conclusions:

Participants were favorably disposed to a whole-person multidisciplinary approach to conservative care, especially when framed as an active treatment approach. Models of conservative care excluding the possibility of dialysis were less embraced, suggesting that current models will require adaptation to meet the needs of US patients and their families.

PLAIN-LANGUAGE SUMMARY

Conservative care is an important therapeutic option for patients with advanced kidney disease who believe that the burdens of dialysis are not outweighed by its potential benefits. However, efforts in this country to develop conservative options for patients who wish to pursue dialysis have lagged considerably behind those in other countries. In this study, we interviewed older patients with advanced kidney disease but not receiving maintenance dialysis and their family members about their reactions to descriptions of conservative care taken from decision aids developed in other countries. The findings suggest how models of conservative care developed in other countries could be adapted to meet the needs and preferences of US patients and their family members.

Graphical Abstract

Growing recognition of the limits of maintenance dialysis for some groups of patients has led to the emergence of conservative care models for advanced kidney disease in several developed countries outside the United States. Although there is some variation across conservative care models, most focus on “slowing the decline in renal function, active symptom management, advance care planning and the provision of palliative care.”1(p 118) Supportive of this approach, data from some of these programs suggest that survival2–7 and quality of life8–10 for older adults (aged ≥75 years) with significant comorbid conditions may be no worse than for patients treated with dialysis. Compared with patients who are treated with dialysis, those who are managed conservatively also spend less time in health care settings, are less likely to undergo invasive procedures and die in the hospital, and are more likely to receive hospice and palliative care near the end of life.6,11,12

In the United States, dialysis is a powerful default treatment for advanced kidney disease,13,14 and it is relatively uncommon for patients who develop the signs and symptoms of advanced kidney disease not to start dialysis.15 Consistent with this, very few US centers have developed conservative care models16 and most US patients report no knowledge of therapeutic alternatives to dialysis.17,18 Most decision aids for patients with advanced kidney disease either do not mention conservative care or present this as an option of last resort.19–26 The few that explicitly address conservative care were developed in other countries24–27 and may not adequately address the needs of US patients and their families and clinicians.

To inform efforts to develop conservative care models in the United States, we conducted a qualitative study of older US patients with advanced kidney disease and their family members to gain a deeper understanding of their perception of conservative care as described in decision aids developed outside the United States.

Methods

Study Population

We recruited a consecutive sample of English-speaking patients 75 years and older with advanced kidney disease from 3 medical centers in the greater Seattle area between June 2019 and January 2020. Advanced kidney disease was defined as having at least 2 outpatient measurements of estimated glomerular filtration rate ≤ 20 mL/min/1.73 m2 separated by at least 90 days during the previous year. We used a combination of letters and telephone calls to contact eligible patients. During the initial telephone contact, we administered the 6-Item Cognitive Impairment Test screening tool28 to exclude those who screened positive for cognitive impairment. Patients interested in participating in the study were invited but not required to identify a family member (or other close person) who assists them with medical decision making to also take part in the study. Family members underwent similar procedures to screen for cognitive impairment.

We obtained written informed consent from patients and their family members to participate in the study. Enrolled participants were offered $40 as compensation for time spent participating in the study. The study was approved by the institutional review boards at University of Washington and VA Puget Sound Health Care System.

Participant Characteristics

At enrollment, participants were asked to complete a survey that included questions about their demographic characteristics and knowledge of conservative care and dialysis.

Cognitive Interviews

Given the findings of prior studies indicating that most patients are unaware of conservative care,17,18 conventional exploratory qualitative interviewing is not suitable for gathering empirical information from participants on a phenomenon when the phenomenon is not known to them.29 Therefore, we conducted cognitive interviews with participants to elicit their understanding and receptivity to prepared information on conservative care. Cognitive interviewing is a structured approach to eliciting how participants process information using a series of probing techniques.30 We used think-aloud probes to encourage participants to verbalize how they understood the intent and meaning of the information presented and then asked for further clarification of their thought processes and reactions. We used concurrent probes to explore participants’ reactions after each exchange of information, proactive probes using scripted questions to address anticipated reactions to shared information, and reactive probes to explore unanticipated reactions. Finally, we used retrospective probes to elicit participants’ final reflections on the exercise and any additional needs and preferences for information they might have about conservative care. S.P.Y.W., A.M.O., J.R.C., and G.S. together developed the interview guide (Item S1), which was iteratively refined as interviews were analyzed to improve flow and quality and depth of responses.

Information on conservative care shared during interviews was adapted from publicly available English-language decision aids on the treatment of advanced kidney disease developed outside the United States that include information for conservative care and have been evaluated in research studies (Box 1).27,31–33 We selected information a priori from decision aids that pertained to at least 1 of the following 6 domains: treatment aim, treatment eligibility, treatment outcomes, illness experience, care services, and care structure (Item S2). Because the tone and detail used to describe conservative care varied across decision aids, we selected at least 2 examples of information in each domain from different aids. Information was read aloud and printed out for participants to hear and read in the order as listed in Box 1. Wording used to convey information on conservative care from the original decision aids was adapted to improve readability and accommodate an 8th grade reading level. Additionally, we asked participants about their reactions to the term “conservative care” itself, as well as other common terms used in the literature to describe this approach (ie, “kidney supportive care,” “nondialysis pathway,” “maximal medical management,” and “kidney palliative care”).

Box 1. Information Statements on Conservative Care Used in Cognitive Interviews.

Conservative care does not replace the work of the kidneys. A person’s failing kidneys will keep getting worse.

With conservative care, the kidney disease runs its natural course.

Conservative care keeps a person’s kidney working for as long as the kidney disease allows.

- The goal of conservative care is to help you live well without dialysis. Conservative care involves:

- Treating symptoms

- Preventing or managing medical problems

- Protecting remaining kidney function

- Psychological support

- Social support

- Helping to plan for the future

People who decide to have conservative care often have other medical conditions or are very frail. They often feel that the burden and discomfort caused by dialysis outweigh the benefits of managing the disease.

Conservative care is suitable for all patients.

It is your choice whether to have conservative care or dialysis.

With conservative care, your health will deteriorate so your life expectancy will decrease.

Life expectancy is difficult to predict with conservative care and depends on the state of your kidney function, other health problems, lifestyle, and overall health.

You may have weeks, months, or years with conservative care. Some people will live just as long as they do on dialysis and feel better with conservative care.

You will develop symptoms as your kidney failure gets worse.

Your health care team will treat any symptoms of kidney failure and keep you comfortable.

There are some food and drinks you may need to limit or avoid.

Community resources such as home care can also be accessed for you. You will get specialized support when needed for end-of-life care.

Conservative care includes all other parts of kidney care and support except dialysis.

Apart from medication, there are no regular treatments with conservative care.

You will continue seeing your kidney specialist, who will help manage your symptoms, diet, and medications. It is recommended that every 1-3 months you have a checkup with your health care team to monitor your health. Between visits you can call your team with questions or concerns.

We continued to recruit participants for interviews until no new themes related to conservative care emerged with additional interviews (ie, thematic saturation).34 Because not all enrolled patients identified a family member to participate in the study, thematic saturation was based on emergent themes in patient interviews. Each interview required approximately 1 hour to complete. Either T.O. or S.P.Y.W. completed an in-person interview with each participant, and interviews with patients and their family member were conducted separately. All interviews were audiorecorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analytical Approach

We used an inductive approach to thematic analysis of interview transcripts to allow for identification of emergent concepts present in the source data.35 T.O. and S.P.Y.W. independently reviewed each transcript to identify emergent themes reflecting the reactions of participants to information about conservative care. Transcripts were reviewed individually line by line and individual responses to each statement on conservative care were examined across subjects. The 2 authors convened at regular intervals to review coded transcripts to appraise the thoroughness in observations, differences in interpretation of transcripts, and proximity to thematic saturation. J.R.C. and G.S. also participated in interval reviews of transcripts and codes with T.O. and S.P.Y.W. to refine theme definitions. After the transcripts were coded, T.O. and S.P.Y.W. examined all the codes and their associated statements to identify relationships between codes and merge related codes into larger thematic categories. Dominant themes were selected based on the consistency with which they emerged from most or all interviews.36 Analytical memos were recorded throughout our contact with the data to capture our thinking process and flow of ideas as they arose. All authors participated in iteratively refining the final thematic schema and interpretation of exemplar quotations from transcripts. The backgrounds of the study team members in nephrology (S.P.Y.W. and A.M.O.), health education (T.O.), bioethics (S.P.Y.W. and J.R.C.), palliative care (J.R.C.), and psychology (G.S.) supported the breadth and depth of data interpretation.34 We used Atlas.ti, version 8, to annotate transcripts and organize codes and memos.

Results

We sent recruitment letters to 60 patients, of whom we were able to reach 37 by telephone to discuss the study. Of these, 15 did not wish to participate in the study, 8 screened positive for cognitive impairment and were therefore ineligible to participate, and 14 consented to participate. Of those who consented, 6 identified a family member or other close person who could be contacted, all of whom consented to participate in the study. The characteristics of enrolled participants are presented in Table 1. Most (n = 12) had not heard of conservative care before participating in this study.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Study Participants

| Patients (n = 14) | Close Persons (n = 6) | |

|---|---|---|

| Female sex | 4 | 4 |

| Age, y | 79 ± 7 | 71 ± 12 |

| Race | ||

| White | 11 | 4 |

| Black | 1 | 0 |

| Asian | 1 | 2 |

| Other | 1 | 0 |

| Highest educational attainment | ||

| Any high school | 4 | 0 |

| Any college | 4 | 5 |

| Any graduate school | 6 | 1 |

| Employment status | ||

| Working | 1 | 2 |

| Retired | 13 | 4 |

| Marital status | ||

| Spouse/live-in partner | 10 | 6 |

| Single, widowed, divorced | 4 | 0 |

| Relationship to patient | ||

| Spouse/live-in partner | NA | 5 |

| Adult child | NA | 1 |

| Household annual income | ||

| <$25,000 | 4 | 2 |

| $25,00-$50,000 | 3 | 1 |

| $50,000-$70,000 | 2 | 1 |

| >$75,000 | 2 | 2 |

| Decline to respond | 3 | 0 |

| Self-rated health | ||

| Excellent | 1 | 0 |

| Very good | 2 | 3 |

| Good | 6 | 2 |

| Fair | 4 | 1 |

| Poor | 1 | 0 |

| Have you ever heard of the following? | ||

| Dialysis | 14 | 6 |

| Conservative care | 5 | 3 |

Note: Values given are numbers of patients, except for age, which is given as mean ± standard deviation.

From thematic analysis of cognitive interviews, 4 prominent themes emerged reflecting participants’ responses to information about conservative care: (1) core elements of conservative care, (2) importance of how conservative care is framed, (3) an explicit process to shared decision making, and (4) relationship between conservative care and dialysis. Exemplar quotations from interviews illustrating themes are provided in Boxes 2 to 5.

Box 2. Theme 1: Core Elements of Conservative Care.

Quote 1a: “The idea of keeping a person’s kidneys working for as long as the disease allows, I really like that. And I’d like to learn to live as well as I can without dialysis … I’m actually fairly well-educated, self-educated about kidney disease. I’ve even taken a couple of classes at the [dialysis center], I kind of figured out that I know as much as I can about kidney disease … There might be a huge change in knowledge.” (17)

Quote 1b: “It’s a full spectrum program … That you’re broadly concerned with me as a whole person, a holistic approach … It’s what I wanted to hear.” (3)

Quote 1c: That’s the most positive statement I’ve heard so far … That my health care team will continue to follow me no matter where on the spectrum we go. (1)

Quote 1d: It’s a little bit melancholy … What it’s saying is there’s really nothing that can be done … that you’re on your own … Tennyson, “may there no moaning of the bar, when I put out to sea. ” (5)

Quote 1e: I guess I would like to know how they treat symptoms of kidney failure. I don’t know what the symptoms are, so I don’t know how they treat them. (2)

Quote 1f: There’s still some details that are missing … Is there any way of forecasting or determining how long you might live with this process? That’d be good input. (7)

Quote 1g: When you have these ongoing critical care things, it is comforting to have something you can control and help the process—at least not make it any worse, for sure. This has been a concern of mine—doing my part. (19)

Quote 1h: Let me lead as close to type of lifestyle as I would have if I didn’t have health issues going on—just allowing me to do what I can as long as I can is a form of support for me. And, just having people around me that care and do whatever they can for me. (19)

Quote 1i: There’s always some slight fear that things can go wrong … I think it’s always in the background … There are always obstacles in life, but if you hit them one at a time, don’t let them o verwhelm you, you don’t let the bastards get you down. (18)

Note: Study ID is given in parentheses.

Box 5. Theme 4: Relationship Between Conservative Care and Dialysis.

Quote 4a: “We’re talking about not care as oppose[d] to care through dialysis and I have a tendency to be black and white.” (20)

Quote 4b: “It sort of says that things will go as they are. I see my doctor every 3 months and my kidney specialist. So nothing changes there. Pretty much the same care as I’m getting now. Just a continuation of what I’m currently experiencing, which is fine. It’s just a confirmation.” (7)

Quote 4c: It indicates to me that I have to make a choice between conservative care and dialysis, that I cannot have both. I think they work together, I would think. I don’t know why they’re separating it out. (3)

Quote 4d: These things are something with conservative care, you do all of this before you need the dialysis. (12)

Quote 4e: Hypothetically, suppose one is going down the road with conservative care, one can say, “What’s this all about? I want to live, and if I change over, it’s going to make me live a little longer, let’s go for it.” It makes you think that not everything is cut and dry. (5)

Quote 4f: I like that best if one was voting … The “nondialysis pathway” I think says it all. (2)

Quote 4g: [Conservative care] seems to describe it well. Sort of consistent with having some sort of orthopedic issue and treating it with exercise and massage and heat and ice as oppose[d] to surgery … I like the term ‘conservative care.’ Being anything but a conservative politically, I know what conservative means. I drink conservatively. I drive relatively conservatively. (18)

Quote 4h: [Kidney supportive care] needs to be defined … I think the layperson is going to go, “what does that mean?” (4)

Quote 4i: [Maximal medical management]? No. It dices, it slices, but wait! It chops! (3)

Quote 4j: [A friend] was on palliative care that was trying to keep her as comfortable as possible until she died. So, “palliative care” has a very negative connotation in my mind. (20)

Note: Study ID is given in parentheses.

Theme 1: Core Elements of Conservative Care

On hearing about conservative care during interviews, participants were generally open to learning more (Box 2, quote 1 a). Among the different aspects of conservative care that we shared with participants, most appealing were approaches that described a “whole-person” (quote 1b) and team-based approach to care (quote 1c). Also appealing were continuity, regularity, accessibility, and reliability of care from their health care team. However, the absence of a structured approach to care raised concerns about abandonment among participants and being left to fend for one’s self (quote 1d). Most participants desired specific information about what symptoms might occur as their illness progressed (quote 1e) and how long one could expect to live with conservative care (quote 1f). A focus on what could be done for kidney disease gave participants a sense of control and opportunity to shape the course of their disease and outcomes (quote 1g). Several participants added that strategies to maintain their current lifestyle (quote 1h) and manage health setbacks (quote 1i) would also be useful.

Theme 2: Importance of How Conservative Care Is Framed

Most participants appeared sensitive to not only what but also how information on kidney disease and conservative care was presented. To most participants, descriptions of conservative care as a passive treatment approach in which declining health was expected were viewed negatively (Box 3, quote 2a) and understood by participants as equivalent to “doing nothing” (quote 2b). Conversely, framing conservative care as an active approach to care intended to delay disease progression and help patients live well without dialysis offered hope (quote 2c), relief from the prospect of dialysis (quote 2d), and affirmation that they were “fighting” to stay alive (quote 2e). Participants were generally wary of definitive statements about the expected course of illness and outcomes of treatment. For instance, several patients shared personal stories of how their kidney function had made small improvements contrary to the predictions of their nephrologists (quote 2f). Life expectancy was also perceived as something that could not be predicted with any precision (quote 2g). However, statements that acknowledged the challenges of prognostication were regarded as candid and forthcoming (quote 2h). For some participants, a measure of uncertainty about prognosis offered hope for a favorable outcome (quote 2i).

Box 3. Theme 2: The Importance of How Conservative Care Is Framed.

Quote 2a: “It says my health is going to deteriorate. If I have kidney disease, my health is going to continue to deteriorate whether I have conservative care or not … Why are you pointing out that my health will deteriorate? I have kidney disease … It came across as negative. ” (3)

Quote 2b: “So you’re just waiting to die? It doesn’t sit well with me.” (12)

Quote 2c: What it’s for, to treat the symptoms and preventing or managing medical problems that might result from damaged kidney function, protecting remaining kidney function. Help a person live well without dialysis … That statement makes me feel positive, kind of anticipating maybe a good outcome … I felt good about it … It gives you hope. (4)

Quote 2d: Sounds like a good plan—dialysis isn’t on it, for one. (14)

Quote 2e: I think treatment is diet, exercise, continued support from other people. I mean those are all things that are treatments … That makes the difference between life and death as far as I’m concerned … I will do whatever it takes for me to continue. (1)

Quote 2f: I understand what it is trying to say that failing kidneys can get worse, but I just proved that it doesn’t have to be because I’m up to [an eGFR of] 16 now, from 7 originally. (19)

Quote 2g: So many things can go wrong … From a philosophical standpoint, it’s just as well that life expectancy is difficult to predict. (18)

Quote 2h: It’s on the informative side. It’s telling you that even though you can’t predict what’s going to happen, the outcome will still be the outcome … It’s pretty matter of fact. (16)

Quote 2i: Conservative care isn’t just giving up … A little bit more of a hopeful feeling, that conservative care is an option—it may or may not curtail life expectancy, but you may feel better. (17)

Note: Study ID is given in parentheses.

Theme 3: An Explicit Approach to Shared Decision Making

All participants saw value in an explicit statement highlighting having conservative care and dialysis as active choices (Box 4, quote 3a). Patients who were learning about the option of conservative care for the first time were surprised to learn that their current care regimen had been a tacit choice (quote 3b). Until the possibility was presented in one of the statements on conservative care, some participants remarked that they had not previously considered the possibility that the burdens of dialysis might outweigh the benefits (quote 3c), which could be validating for those who did not want to pursue dialysis (quote 3d). At the same time, all participants recognized the inherent complexity of decisions about conservative care and dialysis and cited that other factors, such as the influence of family members (quote 3e) and nephrologists’ recommendations (quote 3f), might weigh into decision making. This decision was also viewed as inherently tied to their comfort with mortality (quote 3g), fear of loss (quote 3h), and personal values and preferences near the end of life (quote 3i). One participant expressed that directly addressing end-of-life care, while potentially uncomfortable, might prompt participants to seek more information regarding this care (quote 3j).

Box 4. Theme 3: Explicit Process to Decision Making.

Quote 3a: “Even though I know that it’s my choice, what care I want, for it to come right and say that it’s a person’s choice whether to do this, I like that.” (11)

Quote 3b: “I realize that I’m following a regimen of care that I had no idea was a choice that I was making, and I had no idea that there were specific things that I could ask about or follow. I think it’s knowledge that I never had before, and it’s certainly valuable knowledge.” (1)

Quote 3c: I’d never given any thought to the possibility that dialysis may cause more discomfort and one would feel like it’s not worth it. (20)

Quote 3d: I’m satisfied with the way things are going. I’ve avoided dialysis. Dialysis doesn’t really do anything, it just compensates. Dialysis doesn’t really improve anything. (9)

Quote 3e: It’s telling you it’s very straightforward in the choices there and you decide how you want to do this. Will it be carried forward? If you’ve got other folks that are involved in that decision making, are they going to take your wishes and carry it forward? (16)

Quote 3f: It’s a chance either way. But looking at it from both sides, again, I’d have to talk with the doctor about it, but I’d prefer to take the one without going on dialysis, if possible. (8)

Quote 3g: Going to die a natural death, that’s all it is … It don’t bother me. Just a fact of life, that’s my way of thinking … Not worried about dying, that’s the least of my worries. (10)

Quote 3h: We are very happy that we are not going to have to deal with dialysis. It’s not just how close we came to dialysis but how close we came to death … That’s kind of a scary thought… We’ve been together 55 years …I told her one day, “I’m glad you are feeling better. I wasn’t prepared to lose you yet. ” (20)

Quote 3i: Home care would be an absolute last resort because I would not want my remaining loved ones to remember our home that we enjoyed as the place where all this bad stuff happened in my health … I know hospitals can be cold, sometimes literally, but if I were suffering, I don’t want my husband to remember when he looks at that—my bed or my chair or whatever—to have such strong memories in a negative way. (19)

Quote 3j: With conservative care, assuming that conservative care has been chosen and it is advanced renal failure, they’re going to need some of these other things—hospice … they’re going to need home care and the caregiver is going to need respite care … Even though, hospice care, they’re going to say, “isn’t that end-of-life stuff?” Well, yeah…If it is in black-and-white, it might bring up or persuade, encourage, cause the person to ask further questions … It just puts the onus on the patient, caregivers and/or family to ask questions at the appointments. To say, “what else can we be doing? What else should we be doing?” (4)

Note: Study ID is given in parentheses.

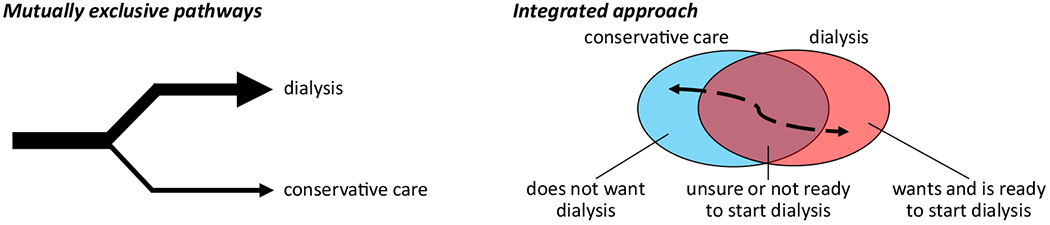

Theme 4: Relationship Between Conservative Care and Dialysis

Participants varied in terms of how they conceived of conservative care in relation to dialysis and broader approaches to kidney disease care. Although a few participants seemed comfortable with the notion of conservative care as an alternative to dialysis (Box 5, quote 4a), comments from other participants suggested that they did not see these care options as necessarily mutually exclusive (quote 4b). Comments from some participants implied that they saw conservative care as something that could be potentially supplemental (quote 4c) or preparatory to dialysis (quote 4d) and thought that there should be flexibility to start dialysis if personal goals and circumstances changed over time (quote 4e).

When asked about nomenclature for conservative care, participants stated that the term nondialysis made clearest the distinction between conservative care and dialysis (quote 4f), and the term conservative care could also be easily understood as a nonaggressive approach to kidney disease when compared with dialysis (quote 4g). Other terms were understood as less precise in defining conservative care or distinguishing it from dialysis. While the term kidney supportive care was viewed favorably as encompassing the different aspects of care described in statements, participants also perceived this term to be too broad (quote 4h). The term maximal medical management seemed somewhat excessive to participants (quote 4i). When asked about the term palliative care, participants who had heard of the term believed it to be associated with end-of-life care (quote 4j).

Discussion

When we spoke with older US patients with advanced kidney disease and their family members about their impressions of conservative care in other countries as described in available decision aids, we found that some but not all aspects of conservative models developed outside the United States were acceptable to them. Participants in this study were generally favorably disposed to the whole-person multidisciplinary approach to care that is inherent to these models, were more open to conservative care when framed as an active versus passive treatment approach, desired an explicit process to shared decision making about conservative care and dialysis, and tended not to see why conservative care and dialysis should be mutually exclusive treatment options.

Our findings provide novel insights into not only what aspects of conservative care are desired by US patients and their family members but also how conservative care might be presented in a relevant and compassionate way to members of this population. Prior qualitative studies of US nephrologists indicate that many view conservative care as akin to “giving up” and believe that dialysis offers “hope” and “optimism.”37,38 Our findings suggest that patients and family members do not necessarily share these views. We found that whether conservative care is regarded positively or negatively by patients and family members likely depends on how conservative care is framed. Participants in this study favored conservative care when described as an active, whole-person, team-based, and structured approach to caring for patients with advanced kidney disease that might enable patients to avoid initiating dialysis, maintain their current health status, and prepare for foreseeable health setbacks. Although nephrologists might worry about the difficulty with predicting survival and future course of illness,39 the patients and family members with whom we spoke were accepting of uncertainty and viewed this as an opportunity to shape the course and outcome of their kidney disease. These findings seem to resonate with those of other qualitative studies indicating that patients draw hope in having some control over their illness40 and feel powerlessness and resignation when told that dialysis is the only recourse for their kidney disease.39

In the United States, care for patients with advanced kidney disease largely focuses on preparing for dialysis.41 By comparison, other developed countries have established dedicated conservative care programs to support patients who do not want to undergo dialysis.42–47 Distinct conservative care programs can be advantageous because of their streamlined efforts to ensure that patients’ goals and preferences are honored in health systems in which initiation of dialysis is the norm.14,16,48 In most cases, these models are intended as an alternative to dialysis and generally only accept patients who have decided not to pursue dialysis.

Nonetheless, our study findings raise questions about whether developing separate care pathways for conservative care and dialysis as found in other countries would optimally meet the needs of US patients and families (Figure 1). When provided with information about conservative care, most participants in this study did not see why conservative care and dialysis should be mutually exclusive and questioned the need to choose between the 2 treatment options. Instead, they saw potential benefit in integrating conservative care and dialysis in the treatment of advanced kidney disease with conservative care possibly serving as first-line treatment with the choice of initiating dialysis if their goals and circumstances were to change. This conceptualization of conservative care among participants in this study is fundamentally different, if not at odds with the dominant mindset among clinicians in this country favoring dialysis as the standard treatment for advanced kidney disease.37,38,49 Rather than serving as a treatment of last resort, this broader conceptualization of conservative care as envisioned by the participants in this study could appeal to a much larger population of patients with advanced kidney disease among whom some choose not to start dialysis, some wish to delay this for as long as possible, and some are not ready or unable to make a decision about dialysis until late in the course of illness.13,14

Figure 1.

Models of care for advanced kidney disease. Different models include those in which conservative care and dialysis are mutually exclusive treatment pathways and conservative care and dialysis are integrated approaches as described by patients and family members in the current study.

Our study has several limitations. First, our study may have limited generalizability. We included a relatively small number of participants who were recruited from a single geographic region and reported having relatively good health despite advanced kidney disease. Most participants in this study were White and their perception of conservative care may differ from those of other racial and ethnic groups, among whom forgoing dialysis may be less acceptable.50,51 The findings also reflect the viewpoints of older patients with advanced kidney disease and may not represent those of younger patients for whom the decision not to pursue dialysis is relatively unusual.15

Second, we did not collect information about patients’ kidney disease trajectory, which might influence their perception of their treatment options for advanced kidney disease, including conservative care.

Third, although the themes presented emerged from both patient and family member interviews, thematic saturation was based on only patient interviews. Therefore, our findings are not exhaustive of relevant themes related to perspectives on conservative care held by family members of patients with advanced kidney disease. Further, family members who participated in this study were exclusively patients’ spouses and their perspectives may not reflect those of adult children or other close persons who may also have important roles in decision making for treatment of advanced kidney disease.

Fourth, our findings reflect perceptions held by patients and family members who were mostly unfamiliar with conservative care before participating in the study. Furthermore, perceptions were based on descriptions of conservative care presented in available decision aids and may not reflect actual practice. We also do not know whether participants’ perceptions of conservative care were shared by their clinicians. Future work is needed to determine whether an approach to conservative care designed with these perceptions in mind would prove feasible and acceptable to patients, their family members, and clinicians, as well as effective in improving shared decision making for treatment of advanced kidney disease and outcomes for patients.

In this qualitative study, older US patients with advanced kidney disease and their family members found many aspects of conservative care models as implemented outside the United States to be appealing but had difficulty with the notion of conservative care and dialysis as mutually exclusive care models. Collectively, our findings suggest that models of conservative care developed in other countries will likely require adaptation to meet the needs and preferences of US patients and their family members.

Acknowledgments

Support:

This work was funded by the National Palliative Care Research Center. The funder had no role in study design; data collection, analysis, or reporting; or the decision to submit for publication.

Acknowledgements:

We thank Whitney Showalter for assistance with study coordination.

Financial Disclosure:

Dr Wong receives research funding from the National Institutes of Health, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, and the VA National Center for Ethics in Health Care, none of which pose a financial conflict of interest with respect to this work. The remaining authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

Supplementary File (PDF)

Item S1: Interview guide.

Item S2: Domains of conservative care.

References

- 1.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guidelines for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2012;3(1):1–163. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murtagh FE, Marsh JE, Donohoe P, Ekbal NJ, Sheerin NS, Harris FE. Dialysis or not? A comparative survival study of patients over 75 years with chronic kidney disease stage 5. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22(7):1955–1962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith C, Da Silva-Gane M, Chandna S, Warwicker P, Greenwood R, Farrington K. Choosing not to dialyse: evaluation of planned non-dialytic management in a cohort of patients with end-stage renal failure. Nephron Clin Pract. 2003;95(2): c40–c46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chandna SM, Da Silva-Gane M, Marshall C, Warwicker P, Greenwood RN, Farrington K. Survival of elderly patients with stage 5 CKD: comparison of conservative management and renal replacement therapy. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2011;26(5):1608–1614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Verberne WR, Geers AB, Jellema WT, Vincent HH, van Delden JJ, Bos WJ. Comparative survival among older adults with advanced kidney disease managed conservatively versus with dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016; 11 (4):633–640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shum CK, Tam KF, Chak WL, Chan TC, Mak YF, Chau KF. Outcomes in older adults with stage 5 chronic kidney disease: comparison of peritoneal dialysis and conservative management. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2014;69(3):308–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rouveure AC, Bonnefoy M, Laville M. [Conservative treatment, hemodialysis or peritoneal dialysis for elderly patients: the choice of treatment does not influence the survival]. Nephrol Ther. 2016;12(1):32–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Da Silva-Gane M, Wellsted D, Greenshields H, Norton S, Chandna SM, Farrington K. Quality of life and survival in patients with advanced kidney failure managed conservatively or by dialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012;7(12):2002–2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yong DS, Kwok AO, Wong DM, Suen MH, Chen WT, Tse DM. Symptom burden and quality of life in end-stage renal disease: a study of 179 patients on dialysis and palliative care. Palliat Med. 2009;23(2):111–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seow YY, Cheung YB, Qu LM, Yee AC. Trajectory of quality of life for poor prognosis stage 5D chronic kidney disease with and without dialysis. Am J Nephrol. 2013;37(3):231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carson RC, Juszczak M, Davenport A, Burns A. Is maximum conservative management an equivalent treatment option to dialysis for elderly patients with significant comorbid disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2009;4(10):1611–1619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hussain JA, Mooney A, Russon L. Comparison of survival analysis and palliative care involvement in patients aged over 70 years choosing conservative management or renal replacement therapy in advanced chronic kidney disease. Palliat Med. 2013;27(9):829–839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wong SP, Vig EK, Taylor JS, et al. Timing of initiation of maintenance dialysis: a qualitative analysis of the electronic medical records of a national cohort of patients from the Department of Veterans Affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(2):228–235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong SPY, McFarland LV, Liu CF, Laundry RJ, Hebert PL, O’Hare AM. Care practices for patients with advanced kidney disease who forgo maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2019; 179(3):305–313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong SP, Hebert PL, Laundry RJ, et al. Decisions about renal replacement therapy in patients with advanced kidney disease in the US Department of Veterans Affairs, 2000-2011. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2016;11 (10):1825–1833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong SPY, Boyapati S, Engelberg RA, Thorsteinsdottir B, Taylor JS, O’Hare AM. Experiences of US nephrologists in the delivery of conservative care to patients with advanced kidney disease: a national qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(2):167–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song MK, Lin FC, Gilet CA, Arnold RM, Bridgman JC, Ward SE. Patient perspectives on informed decision-making surrounding dialysis initiation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28(11):2815–2823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Davison SN. End-of-life care preferences and needs: perceptions of patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5(2):195–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis JL, Davison SN. Hard choices, better outcomes: a review of shared decision-making and patient decision aids around dialysis initiation and conservative kidney management. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 2017;26(3):205–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Medical Education Institute. My life, my dialysis choice. Published 2016. Accessed December 8, 2018, https://mydialysischoice.org/#mi4y-yyy.

- 21.US Healthwise. Kidney failure: what type of dialysis should I have?. Published 2015. Accessed December 8, 2018, https://www.healthwise.net/ohridecisionaid/Print/PrintTableOfContents.aspx?docId=tb1248§ionId=zx3710.

- 22.Kidney Research UK. Yorkshire Dialysis Decision Aid. Published 2014. Accessed December 8, 2018, https://www.kidneyresearchuk.org/file/health-information/kr-decision-aid-colour.pdf.

- 23.Ameling JM, Auguste P, Ephraim PL, et al. Development of a decision aid in inform patients’ and families’ renal replacement therapy selection decisions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ottawa Hospital. Shared end-stage renal patients - decision making. Published 2013. Accessed December 8, 2018, https://decisionaid.ohri.ca/AZsearch.php?criteria=dialysis.

- 25.Kidney Health Australia. My Kidneys, My Choice decision aid. Published 2013. Accessed December 8, 2018, https://kidney.org.au/cms_uploads/docs/mykidneymychoice.pdf.

- 26.Alberta Health Services. Published 2016. Accessed December 8, 2018. http://www.ckmcare.com/Resources/Details/PDA

- 27.Fortnum D, Grennan K, Smolonogov T. End-stage kidney disease patient evaluation of the Australian ‘My Kidneys, My Choice’ decision aid. Clin Kidney J. 2015;8(4):469–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Upadhyaya AK, Rajagopal M, Gale TM. The Six Item Cognitive Impairment Test (6-CIT) as a screening test for dementia: a comparison with Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE). Curr Aging Sci. 2010;3(2):138–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kvale S Interviews: An Introduction to Qualitative Research Interviewing. SAGE Publications; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willis GB. Cognitive Interviewing: A Tool for Improving Questionnaire Design. Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Winterbottom AE, Gavaruzzi T, Mooney A, et al. Patient acceptability of the Yorkshire Dialysis Decision AID (YODDA) Booklet: a prospective non-randomized comparison study across 6 predialysis services. Perit Dial Int. 2016;36:374–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Murray AM, Taylor-Kluke B, Page N. Implementing patient decision support tools and processes: the Shared End-Stage Renal Patients Decision Making (SHERPA-DM) Project. CAANT J. 2015;25(2):15–16. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davison SN, Tupala B, Wasylynuk BA, Siu V, Sinnarajah A, Triscott J. Recommendations for the care of patients receiving conservative kidney management: focus on management of CKD and symptoms. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2019; 14(4):626–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Oualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284(3):357–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braun V, Clark AM. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Gual Res Psychol. 2006;3:77–101. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ryan GW, Bernard HR. Techniques to identify themes. Field Methods. 2003; 15(1):85–109. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ladin K, Pandya R, Kannam A, et al. Discussing conservative management with older patients with CKD: an interview study of nephrologists. Am J Kidney Dis. 2018;71 (5):627–635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grubbs V, Tuot DS, Powe NR, O’Donoghue D, Chesla CA. System-level barriers and facilitators for foregoing or withdrawing dialysis: a qualitative study of nephrologists in the United States and England. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;70(5):602–610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schell JO, Patel UD, Steinhauser KE, Ammarell N, Tulsky JA. Discussions of the kidney disease trajectory by elderly patients and nephrologists: a qualitative study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;59(4):495–503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davison SN, Simpson C. Hope and advance care planning in patients with end stage renal disease: qualitative interview study. BMJ. 2006;333(7574):886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI clinical practice guideline for hemodialysis adequacy: 2015 update. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;66(5):884–930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Okamoto I, Tonkin-Crine S, Rayner H, et al. Conservative care for ESRD in the United Kingdom: a national survey. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(1):120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown MA, Collett GK, Josland EA, Foote C, Li Q, Brennan FP. CKD in elderly patients managed without dialysis: survival, symptoms, and quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015; 10(2) :260–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Teruel JL, Burguera Vion V, Gomis Couto A, et al. Choosing conservative therapy in chronic kidney disease. Nefrologίa. 2015;35(3):273–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kwok W-H, Yong S-P, Kwok O-L. Outcomes in elderly patients with end-stage renal disease: comparison of renal replacement therapy and conservative management. Hong Kong J Nephrol. 2016;19:42–56. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kamar FB, Tam-Tham H, Thomas C. A description of advanced chronic kidney disease patients in a major urban center receiving conservative care. Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2017;4:2054358117718538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan C-H, Noble H, Lo S-H, Kwan T-H, Lee S-L, Sze W-K. Palliative care for patients with end-stage renal disease: experiences from Hong Kong. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2007;13(7):310–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tonkin-Crine S, Okamoto I, Leydon GM, et al. Understanding by older patients of dialysis and conservative management for chronic kidney failure. Am J Kidney Dis. 2015;65(3):443–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Swetz KM, Thorsteindottir B, Feely MA, Parsi K. Balancing evidence-based medicine, justice in health care, and the technological imperative: a unique role for the palliative medicine clinician. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(4):390–391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Karlin J, Chesla CA, Grubbs V. Dialysis or death: qualitative study of older patients’ and their families’ understanding of kidney failure treatment options in a US public hospital setting. Kidney Med. 2019;1 (3):124–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kurella Tamura M, Goldstein MK, Perez-Stable JE. Preferences for dialysis withdrawal and engagement in advance care planning within a diverse sample of dialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2010;25(1):237–242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]