Abstract

Background

Although herbal medicines are used by patients with cancer in multiple oncology care settings, the magnitude of herbal medicine use in this context remains unclear. The purpose of this review was to establish the prevalence of herbal medicine use among patients with cancer, across various geographical settings and patient characteristics (age and gender categories).

Methods

Electronic databases that were searched for data published, from January 2000 to January 2020, were Medline (PubMed), Google Scholar, Embase, and African Index Medicus. Eligible studies reporting prevalence estimates of herbal medicine use amongst cancer patients were pooled using random-effects meta-analyses. Studies were grouped by World Bank region and income groups. Subgroup and meta-regression analyses were performed to explore source of heterogeneity.

Results

In total, 155 studies with data for 809,065 participants (53.95% female) met the inclusion criteria. Overall, the pooled prevalence of the use of herbal medicine among patients with cancer was 22% (95% confidence interval (CI): 18%–25%), with the highest prevalence estimates for Africa (40%, 95% CI: 23%–58%) and Asia (28%, 95% CI: 21%–35%). The pooled prevalence estimate was higher across low- and middle-income countries (32%, 95% CI: 23%–42%) and lower across high-income countries (17%, 95% CI: 14%–21%). Higher pooled prevalence estimates were found for adult patients with cancer (22%, 95% CI: 19%–26%) compared with children with cancer (18%, 95% CI: 11%–27%) and for female patients (27%, 95% CI: 19%–35%) compared with males (17%, 95% CI: 1%–47%).

Conclusion

Herbal medicine is used by a large percentage of patients with cancer use. The findings of this review highlight the need for herbal medicine to be integrated in cancer care.

1. Introduction

Cancer is a major global health problem. In 2018, there were an estimated 9.6 million cancer fatalities and 18.1 million newly diagnosed cases [1]. Current trends indicate that the previously predicted increase to 20 million new cases by 2025 is likely to be surpassed [2]. The overall implications of this high rate of new cases of cancer include increased health, economic, and social costs, which will continue to put a burden on the limited resources and weak healthcare systems in poor countries. As a result, herbal (traditional) medicines use in cancer care may be increased in those countries.

Herbal medicine use associated with cancer, including in multiple oncology care settings, remains uncontested [3]. Previous studies have indicated that herbal medicine is the commonest form of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) used by patients with cancer, with increasing use following a cancer diagnosis [4–12]. Furthermore, advances in conventional cancer care have not deterred patients with cancer from using herbal medicines for numerous reasons, including patient- or disease-related factors, cultural and historical factors, geographical or topological factors, and healthcare or system-related factors [11, 13–21].

Several studies have identified and documented the clinical (cancer disease) and individual (demographic) factors associated with the usage of herbal medicine in cancer. Numerous factors have been positively correlated with herbal medicine use in cancer, such as young age, high education level, high-income level, ethnicity, female gender, cancer diagnosis, longer survival period since cancer diagnosis, receiving single or multiple cancer chemotherapies, being married, completion of conventional cancer treatment, having certain cancer symptoms, cancer metastasis, and belonging to specific social groups [22–27]. However, old age, being a child, having cancer comorbidities, place of residence, and the experience of chemotherapeutic side effects are negatively associated with herbal medicine use in cancer [16, 26, 28].

Some herbal medicines possess compounds that are pharmacologically active against cancer cells, and preclinical studies have consistently shown that numerous herbal medicines or herbs have antiapoptotic, anti-inflammatory, cell regenerative, and antioxidant effects on cancer cells. However, the clinical evidence concerning the efficacy of most herbal medicines or specific herbs used in cancer is largely inconclusive [29, 30]. Clinical studies have reported that the use of herbal medicines in cancer lowered the mortality rate hazard ratio of patients with lung cancer (thereby increasing survival), improved patients' quality of life through reducing cancer symptoms and conventional drug side effects (e.g., nausea and vomiting), and had chemopreventive activity against certain cancers [17, 19, 31, 32].

Conversely, observational studies have indicated that concomitant herbal medicines use with antineoplastic drugs may result in drug to herb interaction (at all pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamics levels) and adverse side effects or events [9, 31, 33, 34]. Adverse side effects or events range from minor side effects (e.g., gastrointestinal distress and allergy) to severe organ failure (e.g., hepatotoxicity, nephrotoxicity, bone marrow suppression, and respiratory and cardiac failure) [31, 32, 35–37]. Importantly, the release of antioxidants by herbal medicines is thought to reduce the oxidizing free radicals created by radiotherapy and chemotherapeutic agents against cancer cells, potentially reducing the effectiveness of conventional cancer treatment [24, 38]. Similarly, herbs commonly used in cancer such as St. John's wort and grape juice induce cytochrome isoenzymes (especially CYP3A4), which metabolize most conventional anticancer agents, thereby reducing the efficacy of targeted therapies such as tyrosine kinase inhibitors and anticancer hormonal therapies [31, 32, 38]. St. John's wort, specifically, was found to reduce the levels of plasma irinotecan, docetaxel, and imatinib mesylate antichemotherapeutic agents' concentrations [31]. Additionally, other herbs commonly used in cancer have been found to cause bleeding tendencies following surgery (e.g., ginkgo, garlic), hypoglycemia (e.g., ginseng), and hepatotoxicity (e.g., kava) and possess carcinogenic or negative tumor moderating effects [4, 35, 39]. In addition, heavy metal contamination in some herbal medicines may alter the pharmacokinetic profile of commonly used conventional cancer treatments [24, 38, 40].

Despite the widespread herbal medicines use among cancer patients, associated factors, and potential benefits and risks, the overall pooled prevalence of the use of herbal medicines among patients with cancer remains unclear. Previous systematic reviews focused on cancer used qualitative (narrative synthesis) designs and focused on synthesizing primary data on the use of CAM treatment modalities in general [41–47]. Therefore, we conducted a meta-analysis to explore the prevalence of the use of herbal medicine among patients with cancer across various geographical settings and patient characteristics and synthesized the literature on commonly used herbs in cancer. Understanding the prevalence of herbal medicine use by patients with cancer may help inform and guide healthcare policies geared toward integrating herbal medicines use in cancer care. Ultimately, this will help to improve outcomes for patients with cancer, develop wider public health (community) policies around herbal medicine legislation, and promote investment in education and research about herbal medicines used in cancer.

2. Methods

2.1. Protocol Registration

PROSPERO guidelines were used to develop this study protocol. The study protocol was subsequently registered with the open source foundation (doi: 10.31730/osf.io/cbtpy). The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines are used to report this review' findings (https://www.prisma-statement.org, Supplementary Table 1).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

We synthesized hospital- and population-based studies that reported the prevalence of the use of herbal medicines among patients with cancer (Table 1).

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for included studies.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | Female and male participants of all ages suffering from cancer using herbal medicine(s) with or without any other CAM remedy(s) or conventional remedy(s). | Cancer survivors (recovered) |

| Outcomes | Prevalence of herbal medicine use (either reported or self-reported) Herbs commonly used by patients with cancer |

Prevalence not reported |

| Study design | Cohort studies Cross-sectional studies |

Expert reviews Case-control studies Policy reports Case studies Studies with aggregated CAM data |

| Ethical approval | Studies that were approved by an ethical review body or committee and participants consented to participate. | Lack of ethical approval and participant consent |

| Language | Published in the English language | Published in any other language |

2.3. Information Sources and Search Strategy

We searched PubMed, Google Scholar, Embase, and African Index Medicus for articles published from January 2000 to January 2020. The key search terms words that were used to guide the search included the following: “Cancer” OR “Neoplasm” OR “Tumo∗” OR “Malignancy” AND “Herbs” OR “Herbal medicine” OR “Herbal material” OR “Herbal preparation” AND “Prevalence” OR “Use” OR “Proportion” OR “Percent∗” AND “Observational studies” OR “Cohort” OR “Cross-sectional∗” OR “Survey” OR “Cohort” (Supplementary Table 2). In addition, we manually skimmed the references of published review articles and primary studies to obtain any further eligible studies.

2.4. Data Extraction: Selection and Coding

After obtaining relevant studies (A.J.B), two authors (P.P.N and A.M.S) screened the identified articles' abstracts and titles and determined their eligibility for inclusion in this review, independently. Two authors (J.B.A and A.M.S) independently extracted the data using a standard data extraction form or tool created in Microsoft Excel 2016. Before data were extracted, the data extraction tool was pilot tested with 10 studies. Following the findings of the pilot test, improvements to the data extraction tool were made after reaching consensus with all reviewers. The extracted data included the following: (i) methodological or study characteristics, (ii) herbal medicine definitions or terms used, (iii) the focus of study (herbal medicine only or with other CAM modalities), (iii) use of conventional treatment, (iv) gender distribution, (v) participants' average age, (vi) sample size, (vii) proportion or frequency of herbal medicine use, (viii) herbs used in cancer, and (ix) conclusions. Countries were categorized by continent or world regions and according to World Bank economic indicators (Supplementary Table 3). The authors were able to resolve disagreements during data extraction through consensus.

2.5. Risk of Bias Assessment

Using the risk of bias of nonrandomized studies (RoBINS) tool, three authors (J.B.A, A.M.S, and P.P.N) independently assessed and reported the risk of bias in selected studies [48–50]. The risk of bias was categorized as high, moderate (unclear), and low across the various categories of bias (participation bias, selection bias, and confounder bias) (Supplementary Tables 4 and 5).

2.6. Data Analysis and Synthesis

The metaprop command in Stata software (version 12) was used to analyze the data. Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation was used to “stabilize the raw proportions” [51]. The pooled prevalence estimates and their confidence intervals (CI) were computed using the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects model (DL) and Wald method, respectively, based on “the transformed values and their variances” [51]. We inspected the forest plots for heterogeneity and then quantified this using chi-square tests and the I2 statistic. Because of significant heterogeneity (>50%), we explored the possible modifying effects of a number of study-level variables on the overall pooled prevalence of herbal medicine use among patients with cancer based on subgroup and meta-regression analyses [52, 53]. Modifying variables included the following: (i) year of publication (before or after 2010), (ii) study focus (herbal medicine alone vs. herbal medicine with other CAM), (iii) data collection method (researcher-administered vs. self-administered vs. document or record reviews), (iv) country income level (low and middle vs. high income), (v) study setting (hospital vs. community), (vi) study population (adults vs. children), (vii) cancer type (breast vs. prostate vs. hematological vs. others), (viii) region (continent), (ix) World Bank subregion, (x) study design (cross-sectional vs. cohort), and (xi) study country. We evaluated publication bias by inspecting the funnel plot for asymmetry and confirmed it using Egger's regression test [54]. We also reported the weighted pooled prevalence estimates and their 95% CIs. Data related to herbs used by patients with cancer were summarized and described.

3. Results

3.1. Study Selection Flow

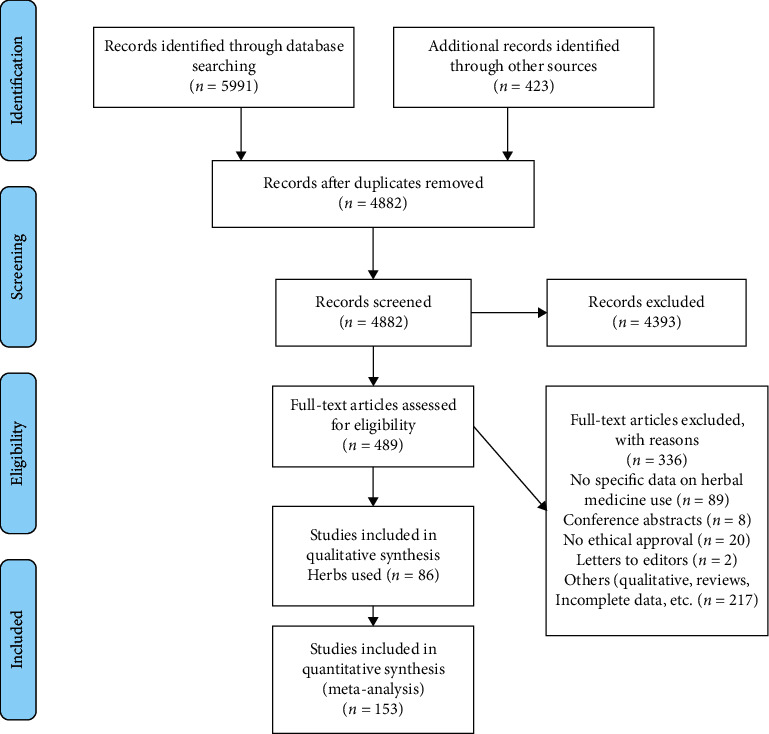

In total, 6414 studies were retrieved from various search engines and databases (Figure 1). After eliminating duplicates, 4882 articles were selected for critical screening of the titles and abstracts. The final meta-analysis included 153 full-text articles that met the inclusion criteria. Eighty-six (86) articles were included in the qualitative synthesis of commonly used herbs by patients with cancer.

Figure 1.

Study selection process based on PRISMA (https://www.prisma-statement.org).

3.2. Study Characteristics

Characteristics of the included studies, which involved 809,065 participants (53.95% female) from 44 countries, are given in Table 2. The average age of the study participants was 50.98 ± 17.39 years, and the average response rate was 76.95% ± 19.78%. The majority of studies were conducted in America (34.19%), Europe (30.32%), and Asia (29.68%). However, based on World Bank subregions, most studies were carried out in Europe and Central Asia (32.92%), North America (30.32%), and East Asia and the Pacific (23.23%). The majority of the included primary research studies were from high-income countries (65.77%), with the US at the top of the list of individual countries (27.10%). Most studies used cross-sectional designs (99.35%), focused on studying herbal medicine as part of other CAM modalities (92.26%), and were conducted in hospital settings (85.81%) among adult populations (83.23%). Most participants were recruited using convenience sampling techniques (63.87%). The most common data collection method was self-administered interviews (52.90%), and the most common cancer type was breast cancer (18.71%).

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies (n = 155).

| Variable | Mean ± standard deviation or n (%) |

|---|---|

| Female (n = 96) | 53.95 ± 14.04 |

| Age, years (n = 86) | 50.98 ± 17.39 |

| Response rate (n = 99) | 76.95 ± 19.78 |

| Study year (10-year block) | |

| 2000–2010 | 80 (51.61) |

| 2010–2020 | 75 (48.39) |

| Region (continent) | |

| America | 53 (34.19) |

| Asia | 46 (29.68) |

| Europe | 47 (30.32) |

| Oceania | 6 (3.87) |

| Africa | 3 (1.94) |

| Subregion (World Bank category) | |

| Europe and Central Asia | 51 (32.92) |

| North America | 47 (30.32) |

| East Asia and Pacific | 36 (23.23) |

| Middle East | 13 (8.39) |

| Latin America and the Caribbean | 5 (3.23) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 3 (1.94) |

| Income (World Bank category) | |

| Low/middle income | 51 (34.23) |

| High income | 98 (65.77) |

| Key individual countries (≥5 studies) | |

| USA | 42 (27.10) |

| Turkey | 18 (11.61) |

| Taiwan | 7 (4.52) |

| UK | 9(5.81) |

| China | 7 (4.52) |

| Germany | 5 (3.23) |

| Malaysia | 5 (3.23) |

| Australia | 5 (3.23) |

| Canada | 5 (3.23) |

| Study design | |

| Cross-sectional/survey | 154 (99.35) |

| Cohort | 1 (0.65) |

| Study type/focus | |

| CAM | 143 (92.26) |

| Herbal medicine only | 12 (7.74) |

| Study setting | |

| Hospital (e.g., cancer clinic, institute, center, unit) | 133 (85.81) |

| Cancer/tumor registry | 6 (3.87) |

| General population (e.g., online) | 16 (10.32) |

| Study population | |

| Adults | 129 (83.23) |

| Children | 23 (14.84) |

| Both | 3 (1.94) |

| Sampling method | |

| Convenience | 99 (63.87) |

| Consecutive | 38 (24.52) |

| Simple random sampling | 13 (8.39) |

| Quota | 1 (0.65) |

| Systematic | 1 (0.65) |

| Stratified | 2 (1.29) |

| Multistage sampling | 1 (0.65) |

| Data collection methods | |

| Self-report/self-administered interview | 82 (52.90) |

| Researcher-administered interview (telephone, in-person) | 59 (38.06) |

| Record/document review | 6 (4.11) |

| Others (mixed, unclear) | 8 (5.17) |

| Cancer type | |

| Breast | 29 (18.71) |

| Prostate | 13 (8.39) |

| Mixed (several types) | 113 (72.90) |

3.3. Overall Pooled Prevalence of Herbal Medicine Use in Cancer by Income and Region

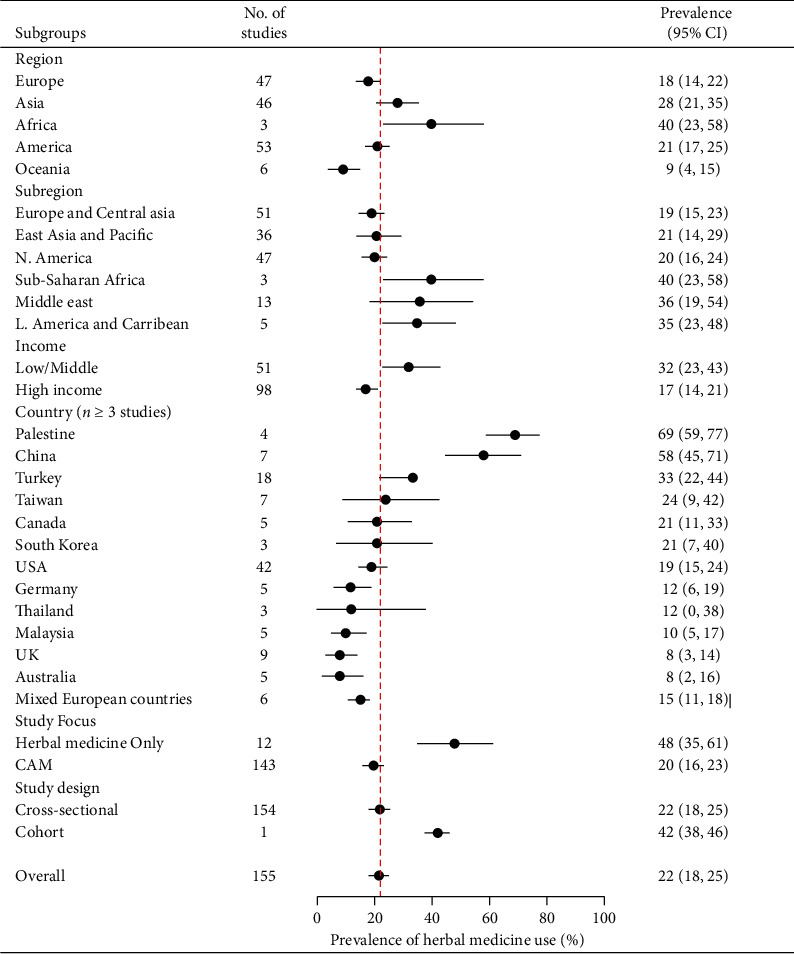

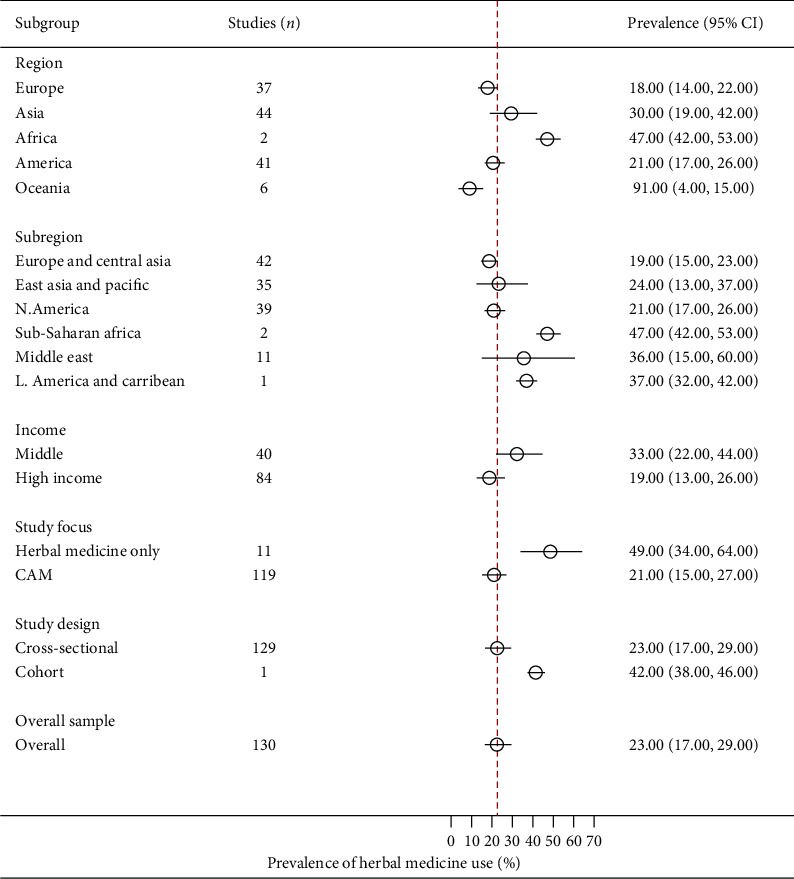

In total, 155 studies reported crude prevalence estimates of herbal medicine use by patients with cancer [3–40, 55–168]. The prevalence estimates ranged from 1% (95% CI: 0%-1%) to 93% (95% CI: 92%-93%). The overall random-effects pooled prevalence of herbal medicine use by patients with cancer was 22% (95% CI: 18%–25%, Figure 2). The I2 statistic was 99.84% (χ2 (df = 154) = 96436.14, P ≤ 0.001), indicating considerable heterogeneity among the included studies. On inspection, the funnel plot was symmetrical, as confirmed by Egger's regression test (P=0.063), indicating the absence of small-study effects (publication bias).

Figure 2.

A summary (subgroup) forest plot on herbal medicine usage in cancer.

In terms of continents, the largest pooled prevalence of herbal medicine use among patients with cancer was found in Africa (40%, 95% CI: 23%–58%) and Asia (28%, 95% CI: 21%–35%, Figure 2). The lowest prevalence was recorded in Oceania (9%, 95% CI: 4%–15%). Analysis by subregion showed the highest prevalence of herbal medicine use among patients with cancer was in sub-Saharan Africa (40%, 95% CI: 23%–58%), followed by the Middle East (36%, 95% CI: 19%–54%), Latin America and the Caribbean (35%, 95% CI: 23%–48%), East Asia and the Pacific (21%, 95% CI: 14%–29%), North America (20%, 95% CI: 16%–24%), and Europe and Central Asia (19%, 95% CI: 15%–23%). Among selected countries (with n ≥ 3 studies), the highest pooled prevalence of herbal medicine use by patients with cancer was in Palestine (69%, 95% CI: 59%–77%, n = 4), followed by China (58%, 95% CI: 45%–71%, n = 7), Turkey (33%, 95% CI: 22%–44%, n = 18), Taiwan (24%, 95% CI: 9%–42%, n = 7), Canada (21%, 95% CI: 11%–33%, n = 5), South Korea (21% 95% CI: 7%–40%, n = 3), the US (19%, 95% CI: 15%–24%, n = 42), mixed European countries (15%, 95% CI: 11%–18%, n = 6), Germany (12%, 95% CI: 6%–19%, n = 5), Thailand (12%, 95% CI: 0%–38%, n = 3), Malaysia (10%, 95% CI: 5%–17%, n = 5), the UK (8%, 95% CI: 3%–14%, n = 9), and Australia (8%, 95% CI: 3%–16%, n = 5). Finally, the pooled prevalence of herbal medicine use in treating cancer was higher among patients from low- and middle-income countries (32%, 95% CI: 23%–42%) compared with high-income countries (17%, 95% CI: 14%–21%).

3.4. Overall Subgroup and Meta-Regression Analyses

We conducted subgroup and meta-regression analyses to investigate the influence of various patient and study characteristics on the overall observed prevalence estimates to explore the heterogeneity observed among the included studies. The subgroup analyses indicated that geographical region (P ≤ 0.001), subregion (P ≤ 0.001), income group (P ≤ 0.001), study focus or type (P ≤ 0.001), study country (P ≤ 0.001), and study design (P ≤ 0.001) had statistically significant moderating effects on the overall pooled prevalence of herbal medicine usage in cancer.

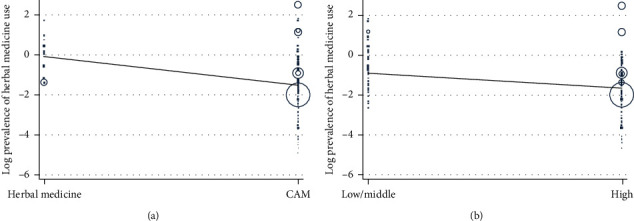

Conversely, in the bivariate meta-regression analysis, only three variables were related to the overall pooled prevalence of usage of herbal medicine by cancer patients. Visual inspection of the scatter plot showed that studies that investigated herbal medicine in conjunction with other CAM modalities in cancer (20%, 95% CI: 16–23%) were more than twice less likely to report a higher pooled prevalence than studies that focused on herbal medicine use alone (48%, 95% CI: 35%–61%; β = −1.47, 95% CI: −2.18 to −0.76; P ≤ 0.001; Figure 3(a)). In addition, studies from high-income countries were less likely to report a high pooled prevalence of herbal medicine use in cancer compared to those from low- and middle-income countries (β = −0.803, 95% CI: −1.23 to −0.38; P ≤ 0.001; Figure 3(b)). However, there was a moderate positive relationship between subregion and pooled prevalence of herbal medicine use in cancer, with certain subregions being more likely than others to report a high prevalence of the use of herbal medicine in cancer (β = 0.134, 95% CI: 0.005–0.264; P=0.043).

Figure 3.

Meta-regression of herbal medicine use by study focus (a) and country income level (b), respectively.

3.5. Specific Pooled Prevalence by Study Subpopulation

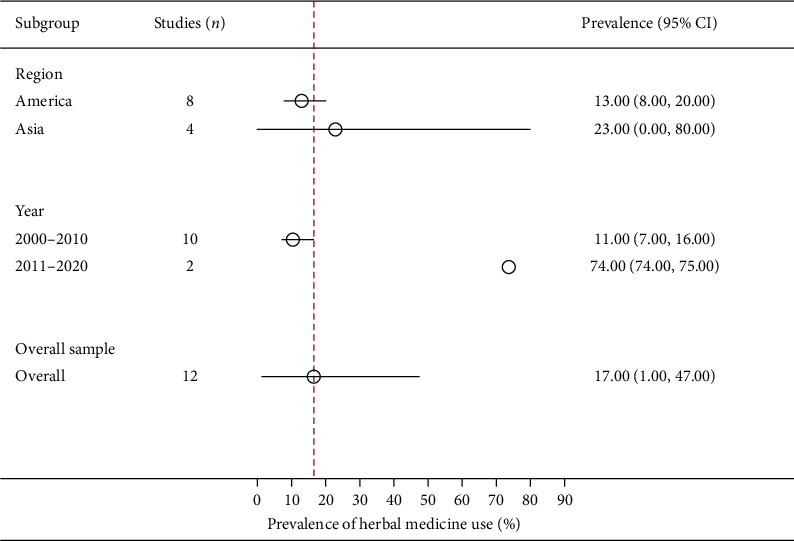

3.5.1. Pooled Prevalence of Herbal Medicine Use by Children with Cancer

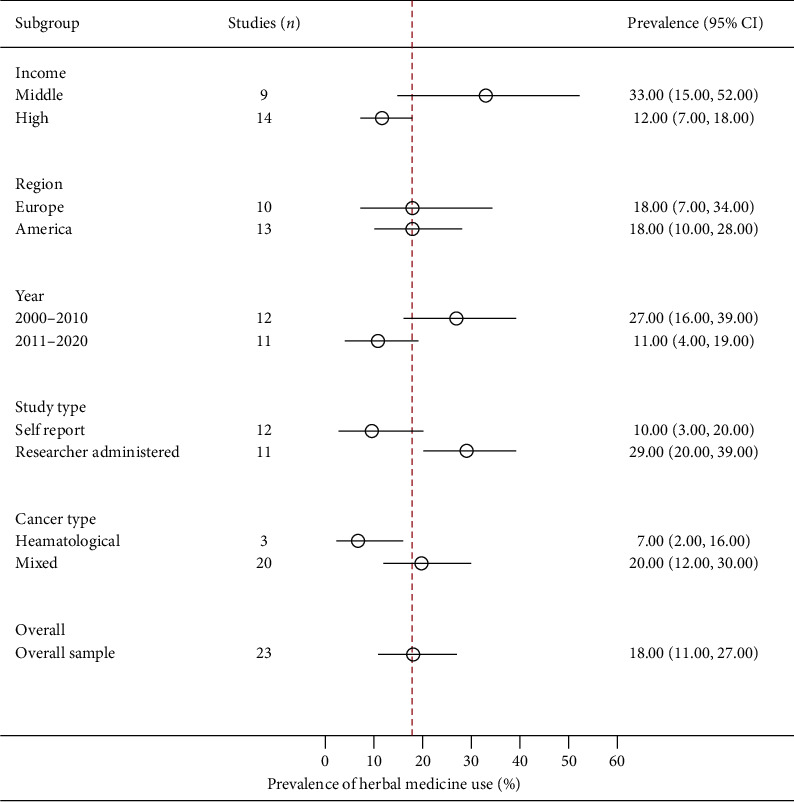

In total, the crude prevalence estimates of herbal medicine use by children with cancer was reported by 23 studies [30, 37, 40, 63, 82, 102, 106, 108, 118, 119, 121, 126, 132–135, 137, 143, 146, 151, 157, 165]. The prevalence estimates ranged from 1% (95% CI: 0%–5%) to 71% (95% CI: 61%–79%). With one exception, these studies were conducted in America and Europe. The overall random-effects pooled prevalence of herbal medicine use by children with cancer was 18% (95% CI: 11%–27%; Figure 4). The I2 statistic was 95.75% (χ2 (df = 22) = 517.11; P ≤ 0.001), suggesting considerable heterogeneity among the included studies. Egger's regression test confirmed that the funnel plot was asymmetrical (P ≤ 0.001), raising the possibility of small-study effects (publication bias).

Figure 4.

A summary (subgroup) forest plot on herbal medicine usage among children with cancer.

Across income groups, low- and middle-income countries (33%, 95% CI: 16%–52%) were more likely to have a high prevalence of herbal medicine use by children with cancer than high-income countries (12%, 95% CI: 7%–18%). In terms of continents, Europe (18%, 95% CI: 7%–34%) and America (18%, 95% CI: 10%–28%) had a similar prevalence of herbal medicine use by children with cancer. Children with hematological cancers (7%, 95% CI: 2%–16%) were less likely to report the use of herbal medicine in cancer than those with all other cancer types combined (20%, 95% CI: 12%–30%).

Subgroup analyses indicated that the income group (P=0.02), data collection method (P=0.01), type of cancer (P=0.03), and study period (P=0.02) had significant moderating effects on the pooled prevalence of the use of herbal medicine in cancer. However, the meta-regression analysis showed that only three variables were statistically significant moderators of the pooled prevalence of herbal medicine usage in cancer. The income group was negatively related to the pooled prevalence of usage of herbal medicine in cancer, with studies from high-income countries less likely to report a high prevalence of the use of herbal medicine by children with cancer than those from low- and middle-income countries (β = −1.263 95% CI: −2.317395 to −0.208673; P=0.021). In addition, the use of herbal medicine was less likely to be reported in studies conducted between 2011 and 2020 (11%, 95% CI: 4%–19%) than those conducted between 2000 and 2010 (27%, 95% CI: 16%–39%; β = −1.19, 95% CI: −2.22 to −0.15; P=0.027). However, studies that used researcher-administered data collection instruments (29%, 95% CI: 20%–39%) tended to report a high pooled prevalence of herbal medicine use by children with cancer than those that were self-administered (10%, 95% CI: 3%–20%; β = 1.38967, 95% CI: 0.418–2.36; P=0.007).

3.5.2. Pooled Prevalence of Herbal Medicine Use by Adult Patients with Cancer

Overall, 130 studies (that met the eligibility criteria) were incorporated in the meta-analysis of the prevalence of herbal medicine usage by adult patients with cancer [3–12, 14–29, 31–36, 38, 39, 55–59, 61, 62, 64–81, 83–101, 103–105, 107, 109–117, 120, 122–125, 127–131, 134, 136, 138–142, 144, 145, 147–150, 152–156, 158–164, 166–168]. The lowest crude prevalence was 1% (95% CI: 0%–1%) and the highest was 86% (95% CI: 78%–92%).

The random-effects pooled prevalence of the usage of herbal medicine by adults with cancer was 23% (95% CI: 17%–29%; Figure 5). The I2 statistic was 99.96% (χ2 (df = 129) = 309703.50; P ≤ 0.001), demonstrating considerable heterogeneity among the included studies. The funnel plot was symmetrical as confirmed by Egger's regression test (P=0.220), suggesting there were no small-study effects (publication bias).

Figure 5.

A summary (subgroup) forest plot on herbal medicine usage among adult patients with cancer.

The highest pooled prevalence of the usage of herbal medicine in adults with cancer was in Africa (47%, 95% CI: 42%–53%), followed by Asia (30%, 95% CI: 19%–42%), America (21%, 95% CI: 17%–26%), Europe (18%, 95% CI: 14%–22%), and Oceania (9%, 95% CI: 4%–15%). In terms of subregions, the highest prevalence of herbal medicine use among adults with cancer was in sub-Saharan Africa (47%, 95% CI: 42%–53%), followed by the Middle East (36%, 95% CI: 15%–60%), East Asia and the Pacific (24%, 95% CI: 13%–37%), North America (21%, 95% CI: 17%–26%), and Europe and Central Asia (19%, 95% CI: 15%–23%). Across income groups, adults with cancer from low- and middle-income countries (33%, 95% CI: 22%–44%) were more likely to report a high prevalence of herbal medicine than those in high-income countries (19%, 95% CI: 13%–26%).

The subgroup analyses indicated that study country (P ≤ 0.001), study focus (P ≤ 0.001), study region (P ≤ 0.001), study design (P ≤ 0.001), income group (P=0.02), and study subregion (P ≤ 0.001) were statistically significant moderators of the pooled prevalence of herbal medicine usage by adults with cancer. However, bivariate meta-regression revealed that only study focus and income group had negative relationships with the pooled prevalence. Studies that focused on herbal medicine along with other CAM modalities (21%, 95% CI: 15%–27%; β = −1.506, 95% CI: −2.25 to −0.76; P ≤ 0.001) and those from high-income countries (β = −0.75, 95% CI: −1.23 to −0.27; P=0.002) were less likely to report a high pooled prevalence of herbal medicine use in adults with cancer than studies that focused on herbal medicine alone (49%, 95% CI: 34%–64%) and were from low- and middle-income countries.

3.6. Specific Pooled Prevalence by Gender

3.6.1. Pooled Prevalence of Herbal Medicine Use by Male Patients with Cancer

Twelve studies reported crude prevalence estimates of the use of herbal medicine among male patients with cancer [71, 76, 88, 90, 97, 101, 112–114, 152, 161, 167]. All of these studies were conducted among patients with prostate cancer in the Americas and Asia. The crude prevalence ranged from 1% (95% CI: 0%–7%) to 76% (95% CI: 75%–76%). The overall random-effects pooled prevalence of the use of herbal medicine by male patients with cancer was 17% (95% CI: 1%–47%; Figure 6). The I2 statistic was 99.98% (χ2 (df = 22) = 44251.66; P ≤ 0.001), representing significant heterogeneity among the included studies. The funnel plot was symmetrical as confirmed by Egger's regression test (P=0.064), indicating the absence of small-study effects (publication bias).

Figure 6.

A summary (subgroup) forest plot on herbal medicine usage among male patients with cancer.

The continent of Asia (23%, 95% CI: 0%–80%) had a higher prevalence of the male patients with cancer who used herbal medicine compared with America (13%, 95% CI: 8%–20%). Subgroup analyses indicated that only the study period (P ≤ 0.001) had a statistically significant moderating effect on the overall pooled prevalence of the use of herbal medicine among male patients with cancer. Contrariwise, the meta-regression analysis showed that this relationship was weak, with studies conducted between 2011 and 2020 (74%, 95% CI: 74%–75%) more likely to report a high prevalence of the use of herbal medicine by male patients with cancer than those conducted between 2000 and 2010 (11%, 95% CI: 7%–16%; β = 2.06, 95% CI: −0.002 to 4.13; P=0.050).

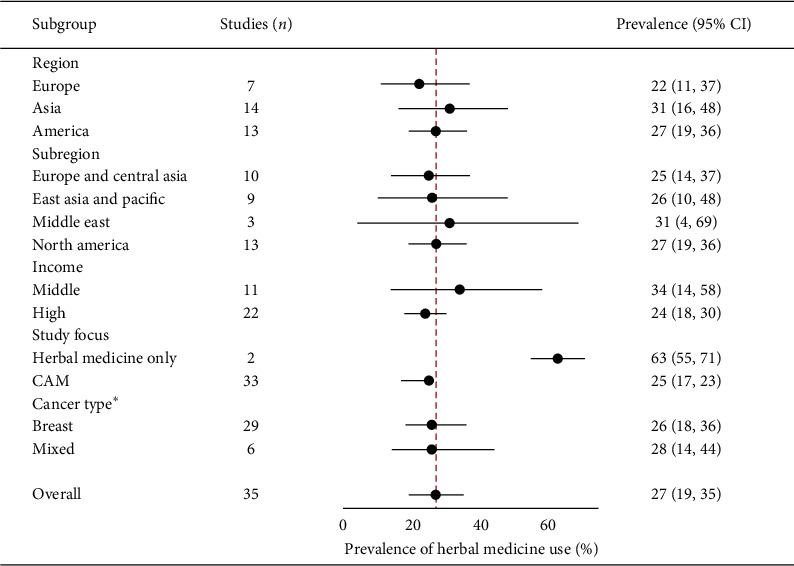

3.6.2. Pooled Prevalence of Herbal Medicine Use by Female Patients with Cancer

The prevalence of herbal medicine usage in female patients with cancer was reported in 35 studies [9, 10, 18, 24, 27, 28, 38, 55, 61, 64, 73, 83–85, 87, 90, 93, 95, 100, 110, 115, 123, 125, 138, 141, 145, 147, 149, 154, 155, 159, 163, 164, 166, 168]. With one exception, these studies were conducted in Asia, America, and Europe. The lowest prevalence of female patients with cancer using herbal medicine was 3% (95% CI: 2%–5%) and the highest was 85% (95% CI: 82%–87%). The random-effects pooled prevalence of the usage of herbal medicine by female patients with cancer was 27% (95% CI: 19%–35%; Figure 7). The I2 statistic was 99.63% (χ2 (df = 34) = 9133.34; P ≤ 0.001) reflecting considerable heterogeneity among the included studies. The funnel plot was symmetrical as confirmed by Egger's regression test (P=0.967P=0.967), indicating the absence of small-study effects (publication bias).

Figure 7.

A summary (subgroup) forest plot on herbal medicine usage among female patients with cancer.

Among continents, the highest prevalence of the use of herbal medicine by female cancer patients was in Asia (31%, 95% CI: 16%–48%) followed by America (27%, 95% CI: 19%–36%) and Europe (22%, 95% CI: 11%–37%). The Middle East subregion (31%, 95% CI: 4%–69%) had the highest prevalence of the use of herbal medicine by female patients with cancer, followed by North America (27%, 95% CI: 19%–36%), East Asia and the Pacific (26%, 95% CI: 10%–48%), and Europe and Central Asia (25%, 95% CI: 14%–37%). A higher pooled prevalence of herbal medicine usage among female patients was recorded in low- and middle-income countries (34%, 95% CI: 14%–58%) compared with high-income countries (24%, 95% CI: 18%–30%). Similarly, studies involving patients with other cancers combined (28%, 95% CI: 14%–44%) tended to report a higher prevalence of herbal medicine usage among female patients with cancer than studies that focused on breast cancer alone (26%, 95% CI: 18%–36%).

The subgroup analysis showed that the study focus (P ≤ 0.001) and study region (P ≤ 0.001) had a statistically significant moderating effect on the overall pooled prevalence of the use of herbal medicine among female patients with cancer. However, in the meta-regression analysis, only study focus had a weak negative relationship with the pooled prevalence of herbal medicine use in cancer. Studies that focused on herbal medicine along with other CAM modalities (25%, 95% CI: 17%–33%; β = −1.634, 95% CI: −3.49–0.220; P=0.082; Figure 7) were less likely to have a high pooled prevalence than studies that focused on herbal medicine use in cancer alone (63%, 95% CI: 55%–71%).

3.7. Herbs Used and Reported by Patients with Cancer

In total, 86 studies reported herbs most commonly used in cancer, which included the following: evening primrose (Oenothera biennis), Echinacea (Echinacea purpurea), garlic (Allium sativum), stinging nettle (Urtica dioica), garden thyme (Thymus vulgaris), black cumin (Nigella sativa), green tea (Camellia sinensis), ginseng (Panax ginseng), ginger (Zingiber officinale), flaxseed (Linum usitatissimum), myrtle (Myrtus communis), ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba), aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis), St. John's wort (Hypericum perforatum), Essiac (containing four herbs: sorrel, slippery elm, Turkey rhubarb, and burdock), garden sage (Salvia officinalis), rosehip (Rosa canina), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), turmeric (Curcuma longa), peppermint (Mentha piperita), Sabah snake grass (Clinacanthus nutans), kava kava (Piper methysticum), chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla), mistletoe (Viscum album), soy products (Glycine max), wild Hedyotis diffusa, barbed skullcap (Scutellaria barbata), noni (Morinda citrifolia), grape seed extract (Vitis vinifera), grapefruit (Citrus paradisi), milk thistle (Silybum marianum), French lavender (Lavendula stoechas), senna (Cassia acutifolia), licorice root (Glycyrrhiza glabra), cinnamon (Cinnamonum zeylanicum), snakehead (Chana striata), blackberry (Rubus caesius), saw palmetto (Serenoa repens), and wormwood (Artemisia absinthium). Other herbs that were less commonly used but reported by patients with cancer are listed in Supplementary Table 6.

4. Discussion

It has become increasingly common to base healthcare decision-making on information obtained from evidence-based medicine. Previously, this information was obtained from systematic reviews of interventional studies. However, this evidence is now also being acquired from systematic reviews of observational studies. The present review investigated the prevalence of the herbal medicine use among patients with cancer to inform and guide the development of healthcare policies concerning integrating herbal medicine in clinical cancer care.

This review suggested that a large estimated percentage of cancer patients use herbal medicine, especially during conventional treatment. The overall pooled prevalence of herbal medicine usage by patients with cancer was 22% (95% CI: 18%–25%), which means approximately one in five patients with cancer used herbal medicine(s) following a cancer diagnosis. This finding was consistent with the literature, where herbal medicine was reported as the leading form of CAM used in cancer [4–6, 8, 11, 12, 114]. This review also found that Africa and Asia had the highest pooled prevalence of the usage herbal medicine in cancer, with the lowest prevalence recorded in Oceania. Similarly, a larger percentage of patients with cancer from low- and middle-income countries used herbal medicine compared with those from high-income countries. This trend was repeated across specific subpopulations of children, adults, and female patients with cancer. The variation in prevalence across regions may be explained by variances in geographical characteristics (i.e., conditions that make some herbs easily available), cultural beliefs and attitudes, and liberalized or low regulation of herbal medicines [18–20, 31, 79, 131, 139, 162]. Conversely, the high herbal medicine usage in low- and middle-income countries might possibly be because of the low income levels, which may mean that patients with cancer are unable to pay for conventional cancer care (financial constraints) and or due to deeply rooted cultural practices related or favorable to use of herbal medicines. For example, as shown in this study, Asian countries such as South Korea and Taiwan, despite having the conditions and economic power to receive high-quality conventional therapies, patients from these countries still continue to use herbal medicine while accepting conventional therapies. Above all, high-income countries (of North America and Europe) where most studies included in this review were conducted do not possess a specialized or deeply ingrained traditional medicine use culture compared to countries of Asia and Africa.

The findings of this review suggested that compared to children (with cancer), adult patients with cancer were more likely to use herbal medicine, although this difference was not statistically significant. This variance in prevalence may be related to adults having more freedom to use herbal medicine than children who generally depend on their parents to access such products [106]. However, given the physiological nature of children (i.e., immaturity of organs such as the liver) and the potential risks of herbal medicine for children as reported in previous studies, parents need to make informed decisions based on evidence-based information before administering herbal medicine to their children to protect children from possible harmful effects [37].

We also found that more female patients with cancer compared to their male counterparts used herbal medicine. However, the pooled prevalence of the use of herbal medicine by male patients with cancer was from studies conducted among patients with prostate cancer; therefore, that reported prevalence best represents herbal medicine usage among patients with prostate cancer. Similarly, most studies that focused on female patients with cancer included patients with breast cancer, although the use of herbal medicine was higher in breast cancer than prostate cancer. These gender-based findings concur with previous literature, where the use of herbal medicine in cancer was related to being female, with women more likely to use herbal medicine as a primary mode of healthcare than men [22, 23, 138].

Finally, this review revealed several herbs commonly used in cancer, some with proven evidence of beneficial effects (anticancer effects) and others with potential risks (harmful side effects and drug interactions) to patients. Those with possible detrimental effects to patients included garlic, ginseng, kava, and St. John's wort [31, 32, 35]. Given that most of the studies that reported use of those herbs were conducted among cancer patients who were receiving conventional cancer therapies, clinicians (oncologists) should ask about herbal medicine use during their routine care of such patients.

4.1. Implications and Recommendations

Regardless of variation in the level of herbal medicine regulatory frameworks in different countries across the world, the high percentage of the usage of herbal medicine reported by this study calls for some form of integration of herbal medicine into cancer care. Healthcare providers must be at the center of this integration. The lack of sufficient clinical evidence should not be a deterrent to this integration, although health practitioners at all levels of patient care should routinely ask about, offer, and document evidence-based advice to patients with cancer on the safety and possible benefits of herbs and herb-drug interactions. Routine discussion of these issues during cancer screening, treatment, and follow-up may help to improve patient care outcomes. However, to equip health workers with evolving evidence on herbal medicines used in cancer, health educators need to continue incorporating knowledge about herbal medicines in oncological care training curricula and also develop programs geared toward understanding, evaluating, and validating herbal medicine use in cancer. In the short-term, health managers could develop short courses or refresher training for in-service healthcare workers on herbal medicines used in cancer to improve their knowledge on this subject.

In addition, policy makers at national governmental and international levels, such as drug authorities and health ministries, should incorporate and update new evidence regarding herbal medicine into oncology treatment guidelines, standard operating procedures, patient charts or electronic medical records, and pharmacopeias. This will assist healthcare workers to document herbal medicine practices in clinical care, which will subsequently promote clinical research on herbal medicine use in cancer.

As evidence regarding herbal medicine continues to evolve, policy makers in countries that regulate herbal medicine as dietary supplements or do not regulate herbal medicine at all need to update, review, or change their herbal medicine regulatory frameworks (either entirely or on a case-by-case basis) to protect patients with cancer from possible harmful effects posed by some herbs. In addition, as the media and other informal sources of information on herbal medicine are responsible for the high use of herbal medicine by cancer patients, oncology care centers and policy makers could create official websites or other media platforms with authentic and updated information on commonly or locally available herbal medicines to counter the misinformation from other sources. These platforms may be communicated to patients during routine cancer care. Importantly, these platforms should encourage patients to always seek advice regarding their specific circumstances from a qualified healthcare professional.

Successful integration of herbal medicine into cancer care either as an alternative form of medicine or alongside cancer medicine requires further high-quality multidisciplinary research on herbal medicines used in cancer, which requires research funding. Therefore, policy makers need to advocate, fundraise, and allocate resources for cancer research concerning herbal medicine use. For example, the lack of funding for research on herbal medicines may explain the relatively few published studies on herbal medicine in cancer, especially in Africa and South America, as observed in this study. In addition, it is important to note that in this study, we were unable to conduct a meta-analysis of the usage of herbal medicine in cancer across many other patients' characteristics due to inconsistent study variables. Therefore, it is necessary to develop a standardized survey tool customizable to various patients with cancer and settings to measure herbal medicine use in cancer. Such a tool will allow comprehensive systematic reviews to be conducted on this subject. It is also necessary to conduct more herbal medicine-specific observational research in cancer to obtain extensive statistics on the extent of herbal medicine usage in cancer across the world.

4.2. Limitations and Strengths of This Study

In terms of the quality of included studies, we rated the majority of studies as having a moderate to high risk of bias, which might have led to over- or underestimation of the pooled prevalence of herbal medicine use reported in this study. This was expected given that nearly all studies used cross-sectional designs. However, the majority of the included studies had moderately large sample sizes and high response rates. Second, there was a high proportion of heterogeneity (between-study heterogeneity) associated with the estimated pooled prevalence(s) reported in this study. However, this was minimized through estimating the pooled prevalence using a random-effects model and performing extensive subgroup and meta-regression analyses. Third, we acknowledge the limited number of studies from sub-Saharan Africa, and the pooled estimate from the few available studies might be overestimated. However, this provides an opportunity for further research on usage of herbal medicine among patients with cancer in Africa. Fourth, we only included studies published in the English language (thus missing studies published in other languages, particularly from the Francophone or Portuguese speaking countries) and did not include grey literature (dissertations or conference abstracts), which might have affected the outcomes (pooled prevalence rates) reported. Nonetheless, based on examination of the funnel plots and use of Egger's test of funnel plot asymmetry, no evidence of small-study effects (publication bias) was observed (found) across a sample of primary studies included in this study; therefore, the results of this review are unlikely to reflect bias. The majority of the included primary studies were prospective, and sufficient time was invested in these studies, making their results somewhat reliable. Finally, this study provides a strong point of reference for future studies, as it is one of the first reviews to be conducted on the prevalence of the use of herbal medicine amongst cancer patients.

5. Conclusion

This systematic review shows that a large percentage of patients with cancer use herbal medicine, especially those from low- and middle-income countries. In addition, larger percentages of adult patients with cancer (compared with children) and female patients with cancer (compared with males) used herbal medicine. In summary, there is need for additional epidemiological investigations exploring herbal medicine integration into cancer care especially for low- and middle-income countries.

Acknowledgments

The Pharm Biotechnology and Traditional Medicine Center of Excellence (PHARMBIOTRAC) at Mbarara University of Science and Technology provided library and Internet services to support this study.

Data Availability

The data used to support the findings of this study are included within the article and will be available online after publication of the article.

Disclosure

PHARMBIOTRAC did not participate in the conceptualization and design of the study, data extraction, analysis, writing, or submission of this article for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors' Contributions

John Baptist Asiimwe, Prakash B. Nagendrappa, Esther C. Atukunda, Mauda M. Kamatenesi, Grace Nambozi, Casim U. Tolo, Patrick E. Ogwang, Ahmed M. Sarki were involved in concept and proposal development and edited and reviewed the study. Asiimwe John Baptist and Ahmed M. Sarki wrote the original draft. John Baptist Asiimwe, Ahmed M. Sarki, and Prakash B. Nagendrappa extracted and analyzed data.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data to this article are submitted together with the manuscript and are available online.

References

- 1.Bray F., Ferlay J., Soerjomataram I., Siegel R. L., Torre L. A., Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2018;68(6):394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2014. World Cancer Report. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peltzer K., Pengpid S. The use of herbal medicines among chronic disease patients in Thailand: a cross-sectional survey. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2019;12:573–582. doi: 10.2147/jmdh.s212953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yarney J., Donkor A., Opoku S. Y., et al. Characteristics of users and implications for the use of complementary and alternative medicine in Ghanaian cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy and chemotherapy: a cross- sectional study. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;13(16):2–9. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-13-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yalcin S., Hurmuz P., McQuinn L., Naing A. Prevalence of complementary medicine use in patients with cancer: a Turkish comprehensive cancer center experience. Journal of Global Oncology. 2018;4(4):1–6. doi: 10.1200/jgo.2016.008896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oyunchimeg B., Hwang J. H., Ahmed M., Choi S., Han D. Complementary and alternative medicine use among patients with cancer in Mongolia: a National hospital survey. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2017;17(1):p. 58. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1576-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tas F., Ustuner Z., Can G., et al. The prevalence and determinants of the use of complementary and alternative medicine in adult Turkish cancer patients. Acta Oncologica. 2005;44(2):161–167. doi: 10.1080/02841860510007549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cilingir D., Gursoy A., Hintistan A. P. S., Nural N. Complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer patients in Northeastern Turkey. PONTE International Scientific Researchs Journal. 2017;73(9) doi: 10.21506/j.ponte.2017.9.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molassiotis A., Scott J. A., Kearney N., et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in breast cancer patients in Europe. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2006;14(3):260–267. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0883-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin Y. H., Chiu J. H. Use of Chinese medicine by women with breast cancer: a nationwide cross-sectional study in Taiwan. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2011;19(3):137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2011.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jang A., Kang D. H., Kim D. U. Complementary and alternative medicine use and its association with emotional status and quality of life in patients with a solid tumor: a cross-sectional study. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2017;23(5):362–369. doi: 10.1089/acm.2016.0289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kucukoner M., Bilge Z., Isikdogan A., Kaplan M. A., Inal A., Urakci Z. Complementary and alternative medicine usage in cancer patients in southeast of Turkey. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines. 2012;10(1):21–25. doi: 10.4314/ajtcam.v10i1.4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ali-Shtayeh M. S., Jamous R. M., Jamous R. M. Herbal preparation use by patients suffering from cancer in Palestine. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2011;17(4):235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kocasli S., Demircan Z. Herbal product use by the cancer patients in both the pre and post surgery periods and during chemotherapy. African Journal of Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicines. 2017;14(2):325–333. doi: 10.21010/ajtcam.v14i2.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Afifi F. U., Wazaify M., Jabr M., Treish E. The use of herbal preparations as complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in a sample of patients with cancer in Jordan. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2010;16(4):208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen G., Qiao T. T., Ding H., et al. Use of Chinese herbal medicine therapies in comprehensive hospitals in central China: a parallel survey in cancer patients and clinicians. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology. 2015;35(6):808–814. doi: 10.1007/s11596-015-1511-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuo Y.-T., Chang T.-T., Muo C.-H., et al. Use of complementary traditional Chinese medicines by adult cancer patients in Taiwan: a nationwide population-based study. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2017;17(2):531–541. doi: 10.1177/1534735417716302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nazik E., Nazik H., Api M., Kale A., Aksu M. Complementary and alternative medicine use by gynecologic oncology patients in Turkey. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2012;13(1):21–25. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.1.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Molassiotis A., Fernandez-Ortega P., Pud D., et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use in colorectal cancer patients in seven European countries. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2005;13(4):251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tarhan O., Muslu U., Somali I., et al. An analysis of the use of complementary and alternative therapies in patients with breast cancer. Breast Care. 2009;4(5):301–307. doi: 10.1159/000240988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yildiz I., Ozguroglu M., Toptas T., Turna H., Sen F., Yildiz M. Patterns of complementary and alternative medicine use among Turkish cancer patients. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2013;16(4):383–390. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Damery S., Gratus C., Grieve R., et al. The use of herbal medicines by people with cancer: a cross-sectional survey. British Journal of Cancer. 2011;104(6):927–933. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ali-Shtayeh M. S., Jamous R. M., Salameh N. M., Jamous R. M., Hamadeh A. M. Complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer patients in Palestine with special reference to safety-related concerns. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2016;187:104–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen Z., Gu K., Zheng Y., Zheng W., Lu W., Shu X. O. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among Chinese women with breast cancer. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2008;14(8):1049–1055. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rausch Osian S., Leal A. D., Allmer C., et al. Widespread use of complementary and alternative medicine among non-Hodgkin lymphoma survivors. Leukemia & Lymphoma. 2015;56(2):434–439. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2014.916803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bazrafshani M. S., Khandani B. K., Pardakhty A., et al. The prevalence and predictors of using herbal medicines among Iranian cancer patients. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2019;35:368–373. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cui Y., Shu X., Gao Y., et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by Chinese women with breast cancer. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2004;85:263–270. doi: 10.1023/b:brea.0000025422.26148.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pedersen C. G., Christensen S., Jensen A. B., Zachariae R. Prevalence, socio-demographic and clinical predictors of post-diagnostic utilisation of different types of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in a nationwide cohort of Danish women treated for primary breast cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2009;45(18):3172–3181. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu T. G., Xiong S. Q., Yan Y., Zhu H., Yi C. Use of Chinese herb medicine in cancer patients: a survey in southwestern China. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/769042.769042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karadeniz C., Pinarli F. G., Oguz A., Gursel T., Canter B. Complementary/alternative medicine use in a pediatric oncology unit in Turkey. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2007;48(5):540–543. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jermini M., Dubois J., Rodondi P. Y., et al. Complementary medicine use during cancer treatment and potential herb-drug interactions from a cross-sectional study in an academic centre. Scientific Reports. 2019;9(1):p. 5078. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-41532-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dhanoa A., Yong T. L., Yeap S. J. L., Lee I. S. L., Singh V. A. Complementary and alternative medicine use amongst Malaysian orthopaedic oncology patients. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2014;14(404) doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyodo I., Amano N., Eguchi K., et al. Nationwide survey on complementary and alternative medicine in cancer patients in Japan. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(12):2645–2654. doi: 10.1200/jco.2005.04.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bahall M. Prevalence, patterns, and perceived value of complementary and alternative medicine among cancer patients: a cross-sectional, descriptive study. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2017;17(1):p. 345. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1853-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Abuelgasim K. A., Alsharhan Y., Alenzi T., Alhazzani A., Ali Y. Z., Jazieh A. R. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with cancer: a cross-sectional survey in Saudi Arabia. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2018;18(1):p. 88. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2150-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chrystal K., Allan S., Forgeson G., Isaacs R. The use of complementary/alternative medicine by cancer patients in a New Zealand regional cancer treatment centr. The New Zealand Medical Journal. 2003;116(1168) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gozum S., Arikan D., Buyukavci M. Complementary and alternative medicine use in pediatric oncology patients in Eastern Turkey. Cancer Nursing. 2007;30(1) doi: 10.1097/00002820-200701000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naja F., Fadel R. A., Alameddine M., et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use and its association with quality of life among Lebanese breast cancer patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015;15:p. 444. doi: 10.1186/s12906-015-0969-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kust D., Samija I., Maric-Brozic J., et al. Use of alternative and complementary medicine in patients with malignant diseases in high-volume cancer center and future aspects. Acta Clinica Croatica. 2016;55(4):585–592. doi: 10.20471/acc.2016.55.04.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gomez-Martinez R., Tlacuilo-Parra A., Garibaldi-Covarrubias R. Use of complementary and alternative medicine in children with cancer in occidental, Mexico. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2007;49(6):820–823. doi: 10.1002/pbc.21101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bishop F., Rea A., Lewith H., et al. Complementary medicine use by men with prostate cancer: a systematic review of prevalence studies. Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases. 2011;14(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2010.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Diorio C., Lam C. G., Ladas E. J., et al. Global use of traditional and complementary medicine in childhood cancer: a systematic review. Journal of Global Oncology. 2017;3(6):791–800. doi: 10.1200/jgo.2016.005587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ernst E. The prevalence of complementary/alternative medicine in cancer: a systematic review. Cancer: Interdisciplinary International Journal of the American Cancer Society. 1998;83(4):777–782. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19980815)83:4<777::aid-cncr22>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Horneber M., Bueschel G., Dennert G., Less D., Ritter E., Zwahlen M. How many cancer patients use complementary and alternative medicine: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2012;11(3):187–203. doi: 10.1177/1534735411423920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Keene M. R., Heslop I. M., Sabesan S. S., Glass B. D. Complementary and alternative medicine use in cancer: a systematic review. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice. 2019;35:33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2019.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verhoef M. J., Balneaves L. G., Boon H. S., Vroegindewey A. Reasons for and characteristics associated with complementary and alternative medicine use among adult cancer patients: a systematic review. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2005;4(4):274–286. doi: 10.1177/1534735405282361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wanchai A., Armer J. M., Stewart B. R. Complementary and alternative medicine use among women with breast cancer: a systematic review. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2010;14(4) doi: 10.1188/10.cjon.e45-e55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schünemann H. J., Cuello C., Akl E. A., et al. GRADE guidelines: 18. How ROBINS-I and other tools to assess risk of bias in nonrandomized studies should be used to rate the certainty of a body of evidence. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2019;111:105–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jüni P., Loke Y., Pigott T., et al. Risk of Bias in Non-randomized Studies of Interventions (ROBINS-I): Detailed Guidance. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sterne J. A., Hernán M. A., Reeves B. C., et al. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355 doi: 10.1136/bmj.i4919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nyaga V. N., Arbyn M., Aerts M. Metaprop: a Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Archives of Public Health. 2014;72(1):p. 39. doi: 10.1186/2049-3258-72-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ryan R. Heterogeneity and Subgroup Analyses in Cochrane Consumers and Communication Review Group Reviews: Planning the Analysis at Protocol Stage Heterogeneity. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Higgins J. P., Thomas J., Chandler J., et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Palmer T. M., Sterne J. A. C., Newton H. J., Cox N. J. Meta-analysis in stata: an updated collection from the stata. Journal. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 55.Albabtain H., Alwhaibi M., Alburaikan K., Asiri Y. Quality of life and complementary and alternative medicine use among women with breast cancer. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal. 2018;26(3):416–421. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2017.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Algier L. A., Hanoglu Z., Ozden G., Kara F. The use of complementary and alternative (non-conventional) medicine in cancer patients in Turkey. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2005;9(2):138–146. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Al-Naggar R. A., Bobryshev Y. V., Abdulghani M., Rammohan S., Osman M. T., Kadir S. Y. K. Complementary/alternative medicine use among cancer patients in Malaysia. World Journal of Medical Sciences. 2013;8(2):157–164. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anderson J. G., Taylor A. G. Use of complementary therapies for cancer symptom management: results of the 2007 National Health Interview Survey. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2012;18(3):235–241. doi: 10.1089/acm.2011.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arthur K., Belliard J. C., Hardin S. B., Knecht K., Chen C. S., Montgomery S. Reasons to use and disclose use of complementary medicine use-an insight from cancer patients. Cancer and Clinical Oncolog. 2013;2(2):81–92. doi: 10.5539/cco.v2n2p81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Arush M. W. B., Geva H., Ofir R., Mashiach T., Uziel R., Dashkovsky Z. Prevalence and characteristics of complementary medicine used by pediatric cancer patients in a mixed western and middle-eastern population. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2006;28(3):141–146. doi: 10.1097/01.mph.0000210404.74427.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ashikaga T., Bosompra K., O’Brien P., Nelson L. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by breast cancer patients: prevalence, patterns and communication with physicians. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2002;10(7):542–548. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aydin Avci I., Koc Z., Saglam Z. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by patients with cancer in northern Turkey: analysis of cost and satisfaction. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2012;21(5-6):677–688. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ball S. D., Kertesz D., Moyer-Mileur L. J. Dietary supplement use is prevalent among children with a chronic illness. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2005;105(1):78–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Balneaves L. G., Bottorff J. L., Hislop G. T., Herbert C. Levels of commitment: exploring complementary therapy use by women with breast cancer. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2006;12(5) doi: 10.1089/acm.2006.12.459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bauml J., Langer C. J., Evans T., Garland S. N., Desai K., Mao J. J. Does perceived control predict complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use among patients with lung cancer? a cross-sectional survey. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014;22(9):2465–2472. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2220-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Berretta M., Pepa C. D., Tralongo P., et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in cancer patients: an Italian multicenter survey. Oncotarget. 2017;8(15):24401–24414. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.14224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bismark R. S., Chen H., Dy G. K., Gage-Bouchard E. A., Mahoney M. C. Complementary and alternative medicine use among patients with thoracic malignancies. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014;22(7):1857–1866. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bonacchi A., Fazzi L., Toccafondi A., et al. Use and perceived benefits of complementary therapies by cancer patients receiving conventional treatment in Italy. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2014;47(1):26–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Can G., Erol O., Aydiner A., Topuz E. Quality of life and complementary and alternative medicine use among cancer patients in Turkey. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2009;13(4):287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2009.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Catt S., Fallowfield L., Langridge C. What non-prescription treatments do UK women with breast cancer use? European Journal of Cancer Care. 2006;15(3):279–285. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2006.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chan J. M., Elkin E. P., Silva S. J., Broering J. M., Latini D. M., Carroll P. R. Total and specific complementary and alternative medicine use in a large cohort of men with prostate cancer. Urology. 2005;66(6):1223–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chao T. H., Fu P. K., Chang C. H., et al. Prescription patterns of Chinese herbal products for post-surgery colon cancer patients in Taiwan. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2014;155(1):702–708. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chui P. L., Abdullah K. L., Wong L. P., Taib N. A. Prayer-for-health and complementary alternative medicine use among Malaysian breast cancer patients during chemotherapy. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2014;14:p. 425. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-14-425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Corner J., Yardley J., Maher E. J., et al. Patterns of complementary and alternative medicine use among patients undergoing cancer treatment. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2009;18(3):271–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.2007.00911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Davis G. E., Bryson C. L., Yueh B., McDonell M. B., Micek M. A., Fihn S. D. Treatment delay associated with alternative medicine use among veterans with head and neck cancer. Head & Neck. 2006;28(10):926–931. doi: 10.1002/hed.20420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eng J., Ramsum D., Verhoef M., Guns E., Davison J., Gallagher R. A population-based survey of complementary and alternative medicine use in men recently diagnosed with prostate cancer. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2003;2(3):212–216. doi: 10.1177/1534735403256207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Engdal S., Steinsbekk A., Klepp O., Nilsen O. G. Herbal use among cancer patients during palliative or curative chemotherapy treatment in Norway. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2008;16(7):763–769. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Erku D. A. Complementary and alternative medicine use and its association with quality of life among cancer patients receiving chemotherapy in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/2809875.2809875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ezeome E. R., Anarado A. N. Use of complementary and alternative medicine by cancer patients at the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu, Nigeria. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2007;7:p. 28. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Farooqui M., Hassali M. A., Shatar A. K., et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicines among Malaysian cancer patients: a descriptive study. Journal of Traditional and Complementary Medicine. 2016;6(4):321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcme.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ferro M. A., Leis A., Doll R., Chiu L., Chung M., Barroetavena M. C. The impact of acculturation on the use of traditional Chinese medicine in newly diagnosed Chinese cancer patients. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2007;15(8):985–992. doi: 10.1007/s00520-007-0285-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Genc R. E., Senol S., Turgay A. S., Kantar M. Complementary and alternative medicine used by pediatric patients with cancer in Western Turkey. Oncology Nursing Forum. 2009;36(3):E159–E64. doi: 10.1188/09.onf.e159-e164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Greenlee H., Kwan M. L., Ergas I. J., et al. Complementary and alternative therapy use before and after breast cancer diagnosis: the pathways study. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2009;117(3):653–665. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0315-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Greenlee H., Neugut A. I., Falci L., et al. Association between complementary and alternative medicine use and breast cancer chemotherapy initiation: the breast cancer quality of care (BQUAL) study. JAMA Oncology. 2016;2(9):1170–1176. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.0685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gross A. M., Liu Q., Bauer-Wu S. Prevalence and predictors of complementary therapy use in advanced-stage breast cancer patients. Journal of Oncology Practice. 2007;3(6):292–295. doi: 10.1200/jop.0762001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Guethlin C., Walach H., Naumann J., Bartsch H. H., Rostock M. Characteristics of cancer patients using homeopathy compared with those in conventional care: a cross-sectional study. Annals of Oncology. 2010;21(5):1094–1099. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gulluoglu B. M., Cingi A., Cakir T., Barlas A. Patients in northwestern Turkey prefer herbs as complementary medicine after breast cancer diagnosis. Breast Care. 2008;3(4):269–273. doi: 10.1159/000144045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hall J. D., Bissonette E. A., Boyd J. C., Theodorescu D. Motivations and influences on the use of complementary medicine in patients with localized prostate cancer treated with curative intent: results of a pilot study. BJU International. 2003;91(7):603–607. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2003.04181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hann D., Allen S., Ciambrone D., Shah A. Use of complementary therapies during chemotherapy: influence of patients’ satisfaction with treatment decision making and the treating oncologist. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2006;5(3):224–231. doi: 10.1177/1534735406291494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hann D. M., Baker F., Roberts C. S., et al. Use of complementary therapies among breast and prostate cancer patients during treatment: a multisite study. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2005;4(4):294–300. doi: 10.1177/1534735405282109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Huebner J., Micke O., Muecke R., et al. User rate of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) of patients visiting a counseling facility for CAM of a German comprehensive cancer center. Anticancer Research. 2014;34:943–948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hunter D., Oates R., Gawthrop J., Bishop M., Gill S. Complementary and alternative medicine use and disclosure amongst Australian radiotherapy patients. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2014;22(6):1571–1578. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hwang J. H., Kim W. Y., Ahmed M., Choi S., Kim J., Han D. W. The use of complementary and alternative medicine by Korean breast cancer women: is it associated with severity of symptoms? Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015;2015 doi: 10.1155/2015/182475.182475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Inanc N., Sahin H., Cicek B., Tasc S. Use of herbs or vitamin/mineral supplements by patients with cancer in Kayseri, Turkey. Cancer Nursing. 2006;29(1):17–20. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200601000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jaradat N. A., Shawahna R., Eid A. M., Al-Ramahi R., Asma M. K., Zaid A. N. Herbal remedies use by breast cancer patients in the West Bank of Palestine. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 2016;178:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2015.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Johannessen H., Von Bornemann Hjelmborg J., Pasquarelli E., Fiorentini G., Di Costanzo F., Miccinesi G. Prevalence in the use of complementary medicine among cancer patients in Tuscany, Italy. Tumori Journal. 2018;94(3):406–410. doi: 10.1177/030089160809400318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jones H. A., Metz J. M., Devine P., Hahn S. M., Whittington R. Rates of unconventional medical therapy use in patients with prostate cancer: standard history versus directed questions. Adult Urology. 2002;59:272–276. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(01)01491-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Judson P. L., Abdallah R., Xiong Y., Ebbert J., Lancaster J. M. Complementary and alternative medicine use in individuals presenting for care at a comprehensive cancer center. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2017;16(1):96–103. doi: 10.1177/1534735416660384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kakai H., Maskarinec G., Shumay D. M., Tatsumura Y., Tasaki K. Ethnic differences in choices of health information by cancer patients using complementary and alternative medicine: an exploratory study with correspondence analysis. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56:851–862. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00086-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kang E., Yang E. J., Kim S. M., et al. Complementary and alternative medicine use and assessment of quality of life in Korean breast cancer patients: a descriptive study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012;20(3):461–473. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1094-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kao G. D., Devine P. Use of complementary health practices by prostate carcinoma patients undergoing radiation therapy. Cancer and Clinical Oncolog. 2000;88(3):615–619. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(20000201)88:3<615::aid-cncr18>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kelly K. M., Jacobson J. S., Kennedy D. D., Braudt S. M., Mallick M., Weiner M. A. Use of unconventional therapies by children with cancer at an urban medical center. Journal of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology. 2000;22(5):412–416. doi: 10.1097/00043426-200009000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kelly M. K., Jacobson J. S., Kennedy D. D., Braudt S. M., Mallick M., Weiner M. A. Types of alternative medicine used by patients with breast, colon, or prostate cancer: predictors, motives, and costs. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2002;8(4):477–485. doi: 10.1089/107555302760253676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kessel K. A., Lettner S., Kessel C., et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine (cam) as part of the oncological treatment: survey about patients’ attitude towards CAM in a University-based oncology center in Germany. PLoS One. 2016;11(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0165801.e0165801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Klafke N., Eliott J. A., Wittert G. A., Olver I. N. Prevalence and predictors of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by men in Australian cancer outpatient services. Annals of Oncology. 2012;23(6):1571–1578. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Koc Z., Tural E., Gudek E. Determining complementary and alternative medicine methods used by paediatric haematology-oncology patients. Journal of Nursing and Healthcare of Chronic Illness. 2011;3(4):361–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-9824.2011.01108.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kristoffersen A. E., Stub T., Broderstad A. R., Hansen A. H. Use of traditional and complementary medicine among Norwegian cancer patients in the seventh survey of the Tromso study. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2019;19(1):p. 341. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2762-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Ladas E. J., Rivas S., Ndao D., et al. Use of traditional and complementary/alternative medicine (TCAM) in children with cancer in Guatemala. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2014;61(4):687–692. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lam Y. C., Cheng C. W., Peng H., Law C. K., Huang X., Bian Z. Cancer patients’ attitudes towards Chinese medicine: a Hong Kong survey. Chinese Medicine. 2009;4:p. 25. doi: 10.1186/1749-8546-4-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lee M. M., Lin S. S., Wrensch M. R., Adler S. R., Eisenberg D. Alternative therapies used by women with breast cancer in four ethnic populations. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(1):42–47. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.1.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Leng J. C., Gany F. Traditional Chinese medicine use among Chinese immigrant cancer patients. Journal of Cancer Education. 2014;29(1):56–61. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0542-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lin Y. H., Chen K. K., Chiu J. H. Prevalence, patterns, and costs of Chinese medicine use among prostate cancer patients: a population-based study in Taiwan. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2010;9(1):16–23. doi: 10.1177/1534735409359073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lin Y. H., Chen K. K., Chiu J. H. Trends in Chinese medicine use among prostate cancer patients under national health insurance in Taiwan: 1996–2008. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2011;10(4):317–327. doi: 10.1177/1534735410392576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lin Y. H., Chen K. K., Chiu J. H. Coprescription of Chinese herbal medicine and western medications among prostate cancer patients: a population-based study in Taiwan. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2012;2012 doi: 10.1155/2012/147015.147015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Link A. R., Gammon M. D., Jacobson J. S., et al. Use of self-care and practitioner-based forms of complementary and alternative medicine before and after a diagnosis of breast cancer. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/301549.301549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Loquai C., Dechent D., Garzarolli M., et al. Use of complementary and alternative medicine: a multicenter cross-sectional study in 1089 melanoma patients. European Journal of Cancer. 2017;71:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Luo Q., Asher G. N. Complementary and alternative medicine use at a comprehensive cancer center. Integrative Cancer Therapies. 2017;16(1):104–109. doi: 10.1177/1534735416643384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]