Abstract

The current coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) presents an ongoing medical challenge, as it involves multiple organs, including the cardiovascular system. Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) has been described in the context of COVID-19 in 2 different scenarios: as a direct complication of the infection, and as an indirect outcome secondary to the psychological burden of quarantine and social isolation (ie, stress-induced cardiomyopathy). Confirming the diagnosis of TTS in COVID-19 may be challenging due to the limited use of coronary angiography consistent with the recommended guidelines aimed at minimizing contact with infected individuals. The use of natriuretic peptide as a diagnostic and prognostic marker in this context may not be reliable as this peptide is already elevated in severe cases of COVID-19 regardless of TTS diagnosis. A relatively high incidence of complications has been reported in these cases, probably related to the severity of the underlying infectious disease. Although quarantine-induced stress cardiomyopathy is an unsurprising outcome of the powerful stress resulting from the current pandemic, conflicting results have been reported, and further studies are encouraged to determine the true incidence.

Résumé

La maladie à coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) qui sévit actuellement représente un défi médical continu, car elle touche plusieurs organes, dont l'appareil cardiovasculaire. Le syndrome de Takotsubo a été décrit dans le contexte de la COVID-19 en fonction de deux scénarios différents : en tant que complication directe de l'infection et comme conséquence indirecte secondaire du fardeau psychologique imposé par la quarantaine et l'isolement social (c'est-à-dire une cardiomyopathie induite par le stress). La confirmation du diagnostic de syndrome de Takotsubo dans les cas de COVID-19 peut s'avérer difficile en raison du recours limité à la coronarographie, conformément aux recommandations visant à réduire au minimum les contacts avec les personnes infectées. L'utilisation du peptide natriurétique comme marqueur diagnostique et pronostique dans ce contexte peut ne pas être fiable, car le taux de ce peptide est déjà élevé dans les cas sévères de COVID-19, indépendamment du diagnostic de syndrome de Takotsubo. Une incidence relativement élevée de complications a été signalée dans ces cas, probablement liée à la sévérité de la maladie infectieuse sous-jacente. Bien que la cardiomyopathie de stress provoquée par la quarantaine soit un résultat peu étonnant du stress puissant associé à la pandémie actuelle, des résultats contradictoires ont été rapportés; il serait donc bon de mener des études supplémentaires pour en déterminer la véritable incidence.

Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) is a type of acute reversible cardiac dysfunction that mainly affects postmenopausal women and is usually preceded by a physical or emotional stressor.1, 2, 3 Patients often present with chest pain, electrocardiogram (ECG) changes in the anterior leads, and elevated cardiac biomarkers.2 Typical echocardiographic findings in most cases are basal hypercontractility and apical ballooning, although other less common forms (ie, reverse and median types) have been reported.4,5 For definitive diagnosis, coronary angiography should be performed to exclude obstructive coronary disease. The pathophysiology of TTS is not fully understood, but it is well established that plasma catecholamines and neuropeptides have a central role.6, 7, 8 Key pathways involve coronary endothelial dysfunction, activation of various cytokines, impaired fatty acid metabolism in cardiac tissue, and multi-vessel spasm leading to demand–supply mismatch and myocardial stunning.9,10 TTS has been described as following various physical and emotional stressors such as anger, argument, surgery, natural disasters, grief, happiness, several medications, general anesthesia, and infectious disease.3,11 The novel coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak caused by the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) presents an ongoing challenge with several medical and economic implications. Multiple cardiovascular complications have been described during SARS-CoV-2 infection, including myocardial injury, myocarditis, arrhythmia, and exacerbation of chronic cardiac diseases such as heart failure.12, 13, 14 In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, TTS may be encountered as a complication of the acute infection or as an indirect outcome of quarantine-induced stress (stress-induced cardiomyopathy).

Takotsubo Syndrome as a Direct Complication of COVID-19

The first cases of COVID-19–associated TTS were reported during the acute phase of the infection, with a typical pattern of apical ballooning. Table 1 summarizes the basic characterestics of the cases.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42

Table 1.

Demographic and laboratory characteristics of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) complicated by Takotsubo syndrome (TTS)

| Angiography | ECG | Peak NPs, pg/mL | Peak troponin (T/I), ng/L | LV function, % | PMH | Sex | Age, y | Study (first author) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Negative T in anterior leads | 474 | 170 | 61 | HTN; DM; asthma | F | 67 | Bapat15 |

| N | ST elevation in anterior leads | 8999 | T-775 | 30 | HTN; HPL | M | 74 | Bernardi16 |

| Y | Inferolateral ST segment elevation | 1312 | I-37 | 38 | Gestational HTN | F | 32 | Bhattacharyya17 |

| N | ST elevation in anterior leads | 17,379 | T-176 | 25 | — | F | 76 | Bottiroli18 |

| N | Diffuse ST elevation | 4573 | 526 | 40 | Healthy | M | 49 | Chao19 |

| N | Negative T in precordial leads | 54,000 | I-2410 l | 40 | Non ischemic cardiomyopathy | F | 67 | Dabbagh20 |

| N | Nonspecific ST-T changes | 110 | 9 | 26 | HTN; COPD | F | 59 | Dave21 |

| N | Nonspecific ST-T changes | — | I-4700 | 30 | Healthy | M | 40 | Faqihi22 |

| N | No ST-T changes | BNP-2060 | I-10,090 | 25–30 | Crohn's disease; emphysema | F | 57 | Gomez23 |

| N | ST elevation in anterior leads | 17,800 | I-4250 | — | HTN; HPL; DM; obesity | F | 72 | Kariyanna24 |

| N | No ST-T changes | 35,000 | 503 | 25–30 | HTN; HPL; hypothyroidism | F | 76 | Khalid25 |

| N | Negative T in anterior leads | 9000 | 692 | — | HTN; DM | F | 54 | Manzur-Sandoval26 |

| Y | ST elevation in anterior leads | — | T-1142 | — | HTN | F | 83 | Meyer27 |

| Y | ST elevation in I AVL | — | I-11,020 | 20 | HTN; DM; HPL | F | 58 | Minhas28 |

| Y | Negative T in precordial leads | — | I-1137 | 40 | HTN; DM; obesity | F | 59 | Moderato29 |

| Y | Non specific ST-T changes | — | T-412 | — | HTN; HPL; hydrocephalus | F | 71 | Nguyen30 |

| Y | ST elevation in anterior leads | — | — | Poor | HTN; DM; HPL; CKD | F | 82 | Oyarzabal31 |

| N | Non specific ST-T changes | — | T-610 | — | HTN; DM; AF | M | 65 | Panchal32 |

| Y | Negative T in precordial leads | 1381 | T-70 | 53 | HTN; DM | M | 84 | Pasqualetto33 |

| Y | — | 3000 | T-647 | 30 | HTN | F | 85 | |

| Y | — | 12,586 | T-621 | 42 | HTN; DM | M | 81 | |

| N | T wave inversion in precordial leads | — | I-5318 | 48 | Breast cancer | F | 87 | Roca34 |

| Y | ST elevation in v1-v2 | 512 | T-135 | 43 | Healthy | F | 43 | Sala35 |

| N | Anterior ST elevation | 299 | I-2273 | Poor | HTN; COPD; rheumatoid arthritis | F | 58 | Sang36 |

| N | Negative T in inferolateral leads | — | T-423 | 30 | HTN; DM | F | 67 | Sattar37 |

| Y | ST elevation in inferolateral leads | 790 | 64,000 | — | Benign mediastinal tumor | M | 50 | Solano-López38 |

| Y | ST elevation in inferior leads | — | I-0.015 | 45 | HTN; DM; schizophrenia | M | 52 | Taza39 |

| Y | ST elevation in anterior leads | — | — | Poor | HTN; HPL; COPD | M | 83 | Titi40 |

| N | Negative T in precordial leads | — | T-94000 | 36 | Obesity | F | 59 | Tsao41 |

| Y | Negative T in precordial leads | — | I-454 | 30 | AF | F | 72 | Van Osch42 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; AVL, augmented vector left; CKD, chronic kidney disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DM, diabetes mellitus; ECG, electrocardiogram; F, female; HPL, hyperlipidemia; HTN, hypertension; LV, left ventricle; M, male; N, no; NP, natriuretic peptide; PMH, past medical history; Y, yes; The type of cardiac troponin assay (T/I) is indicated if available

Epidemiology and Presentation

Most of the reported cases were typical TTS characetrized by apical ballooning and basal hypercontractility. Cases of reverse TTS (characterized by hypercontractility of the apical region and basal hypokinesia) have also been reported.22,30,32,35,38 The leading presenting symptom was chest pain with/without dyspnea, and one patient presented with acute ischemic stroke.24 Of note, several cases were diagnosed based on echocardiography and ECG features during investigation of hemodynamic compromise in critically ill patients with no option for history taking. In most cases, TTS was described during the acute phase, although late onset TTS, 16 days after admission, was also reported.18 Several studies aimed to determine the incidence of TTS during COVID-19. Hegde et al. investigated 169 laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 patients; of these, 3 had typical TTS, 2 had reverse TTS, 1 had biventricular TTS, and 1 was defined as having global TTS with apical sparing.43 Giustino et al. documented the echocardiographic features of 118 consecutive COVID-19 patients, and 5 (4.2%) had echocardiographic findings compatible with TTS, 4 of them with typical appearence, and 1 with the reverse variant.44 In another study, Dweck et al. captured echocardiographic findings in 1216 patients with presumed or confirmed COVID-19; of these, 19 (2%) had echocardiographic findings consistent with TTS.45 Based on these studies, the estimated incidence of TTS complicating SARS-CoV-2 infection is 2%-4%, probably with a higher prevalence in critically ill patients, compared to 1%-2% among patients presenting with suspected acute coronary syndrome in the general population.9 Although TTS traditionally predominates in postmenopausal women (about 90%), 30% of the currently reported cases are males. TTS has been previously reported in infectious diseases, mainly in bacterial sepsis, and rarely in the setting of viral infections.46,47 The influenza virus is recognized as one of the viruses most likely to cause TTS during acute infection or following vaccination.48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55 However, the incidence of TTS in the setting of influenza or other viral infections is not known as no studies have been dedicated to investigating the echocardiographic findings in affected patients. Therefore, it would be difficult to determine whether TTS is more prevalent during COVID-19 than other infectious diseases, or whether it is simply more investigated in this setting.

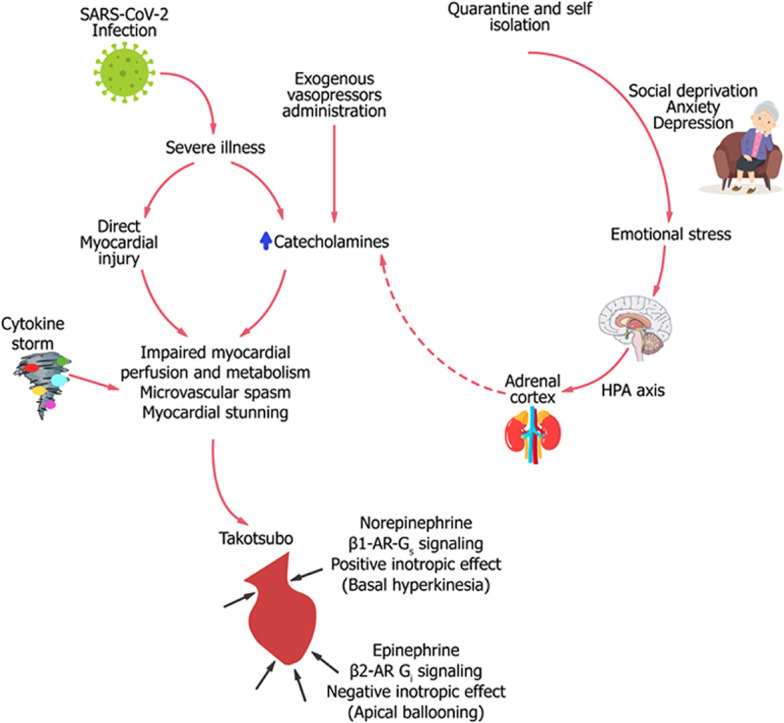

Pathophysiology of TTS During COVID-19

The pathophysiology of TTS is not fully understood, although several mechanisms have been proposed. Catecholamines, cortisol, and natriuretic peptides (NPs) probably play a central role in the development of the specific type of cardiac stunning in the syndrome by mediating several cardiac processes, such as epicardial coronary spasm, microvascular dysfunction, and direct myocyte injury.1,56 Several findings indicate an essential role for catecholamines in TTS, including the high plasma levels in affected patients, and the induction of TTS-like disease following epinephrine or norepinephrin administration.57,58 During catecholamine surge, epinephrine triggers β2-adrenoreceptor in cardiac tissue to switch from Gs to Gi coupling, resulting in apical ballooning.59 Patients with COVID-19 may be exposed to high catecholamine levels secondary to endogenous excretion as a compensatory mechanism to prevent decompensation, and to exogenous intravenous infusion of adrenaline and noreadrenaline used to maintain adequate blood supply in critically ill patients.60 High catecholamine levels might act as a double-edged sword by increasing oxygen demand, and inducing vasospasm and direct myocardial injury. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is another system that is activated in severe COVID-19, with subsequent dysregulations in cortisol and adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) metabolism. During acute illness, activation of the HPA axis, along with reduced metabolism and decreased breakdown of cortisol, contributes to hypercortisolism and hence corticotropin suppression.61 In the study by Tan et al., levels of cortisol were significantly higher in people with COVID-19 than in those without the infection, and survival was halved in people with the highest cortisol levels.62 Whether hypercortisolemia in COVID-19 is a marker of severe inflammation or a leading cause of impaired immunity and vulnerability for complications is not clear yet. The relation between high cortisol levels and TTS is not well established, as TTS has been described in cases of cortisol excess,63 and in cases of secondary adrenal deficiency.64 It is reasonable to assume that activation of the HPA axis during acute illness may mediate TTS by inducing catecholamine secretion. One of the key biomarkers in TTS is N-terminal pro-brain-type natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), which is released following increased ventricular wall stress as part of the neurohormonal activation in the setting of heart failure.65 As in other forms of heart failure, NT-proBNP levels in TTS have been shown to correlate with the severity of left ventricle dysfunction.65 Compared to patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), TTS is associated with higher brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) and lower troponin levels at admission, at peak, and at discharge.66 This unique biomarker profile of a high BNP/troponin ratio provides a reliable parameter to use to differentiate TTS from STEMI, particularly when measured at peak.66 The use of NPs as a diagnostic and prognostic marker in the era of COVID-19 may not be reliable, as NP levels are already elevated in cases of severe COVID-19 regardless of TTS diagnosis.67 Finally, the release of interleukin-6, tumor necrosis factor-α, and other proinflammatory cytokines in severe COVID-19 (known as a cytokine storm) might be accompanied by a catecholamine surge and further contributes to the development of myocardial stunning.68

ECG and Laboratory Findings

Common ECG findings in TTS include ST-segment elevation in the precordial leads, anterior T-wave inversion, and QT-interval prolongation. Reciprocal ST-segment depression and Q waves are often absent.2,11 In the current reported cases, QT prolongation was documented in 8 patients (27%), although ECG description was unavailable in 2 cases. However, it should be noted that patients with COVID-19 are already prone to QT prolongation due to concomitant use of proarrythmic drugs such as quinidine and azithromycin. Cardiac troponin and NT-proBNP levels have been reported to be high in severe COVID-19, reflecting myocardial injury and probably excess mortality.12,62 In one study, among 118 patients with laboratory-confirmed COVID-19, those with TTS (5 patients) had higher troponin I and lower BNP levels compared to patients with myocardial injury (defined as a troponin I level ≥0.04 ng/mL) but without TTS.44 As we suggested above, the combination of slight elevation in troponin with excessive NP levels, commonly seen in TTS, is not applicable as a diagnostic tool in the setting of COVID-19.

Diagnostic Challenges

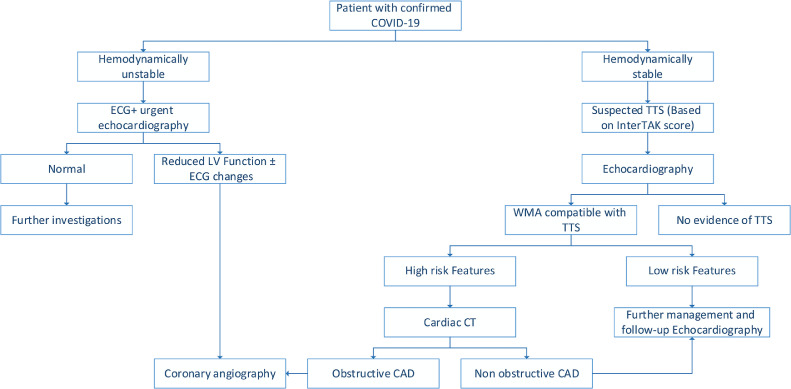

The COVID-19 outbreak necessitates special patient care considerations consistent with the need to minimize physical contact. These considerations make history-taking somehow limited, particularly in critically ill patients. Use of handled echocardiography devices rather than the large machines is recommended to obtain parameters such as left ventricular function, wall motion abnormailities, and valvular pathologies. One of the more sensitive modalities that was shown to detect early subtle myocardial contractility changes and predict mortality in TTS is left ventricular strain echocardiography.69 This modality may help to differentiate TTS from acute coronary syndrome.70 In the COVID-19 setting, Stöbe et al. demonstrated a reduced basal longitudinal strain in 10 of 14 patients (70%) with SARS-CoV-2 infection, a pattern that may be found in reverse TTS.71 However, it should be noted that strain echocardiography is not applicable for routine use during the COVID-19 pandemic, as it is a time-consuming modality. Despite being obligatory for confirming TTS, coronary angiography was performed in only 14 of the reported cases (47%), reflecting the need to minimize physical contact with infected patients. A clinical disgnostic score was developed based on the International Takotsubo Registry (InterTAK) for assessing the probability of TTS. The InterTAK diagnostic score consists of the following 7 variables with and corresponding points: female sex, 25; emotional trigger, 24; physical trigger, 13; absence of ST-segment depression (except in lead aVR), 12; psychiatric disorders, 11; neurologic disorders, 9; and QTc prolongation, 6. Using a cutoff value of 40 score points, sensitivity was 89% and specificity was 91%.72 The InterTAK score was recently proposed as a diagnostic tool during the COVID-19 outbreak.73 Here, we suggest a simplified algorithm for managing COVID-19 patients with suspected TTS (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Suggested algorithm for managing patients with suspected Takotsubo syndrome (TTS) who also have COVID-19. CAD, coronary artery disease; CT, computed tomography; ECG, electrocardiogram; InterTAK, International Takotsubo Registry; LV, left ventricular. WMA, wall motion abnormality.

In unstable patients, ECG, echocardiography, and angiography when indicated are essential for ruling out obstructive coronary artery disease. In stable patients and those with wall motion abnormality consistent with Takotsubo, appropriate management depends on risk profile. When high-risk features are present (ongoing chest pain or dyspnea, episodes of ventricular tachycardia, or extremely elevated NPs), cardiac computed tomography is recommended for assessing the coronary arteries. Observation and follow-up echocardiography seem reasonable in low-risk patients (without the above-mentioned features).

Clinical Course and Outcomes

Major complications and outcomes are provided in Table 2. About 60% of the patients were on inotropic or ventilatory support. Mechanical circulatory support (venous–venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) was provided in only one patient.19 Thromboembolic events occured in 2 cases,16,24 arrhythmia in another 2 cases,37,41 and shock in 7 cases.18,21,22,24,25,28,32 Given that sepsis and cytokine storm accompany the clinical course of severe COVID-19, it might be difficult to separate the hemodynamic effects of the underlying sepsis from TTS. Thromboembolic (venous and arterial) events have been reported in COVID-19, particularly in severe cases. In one large registry, major arterial or venous thromboembolic events occured in 35.3% of COVID-19 patients admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU), and in 2.6% of hospitalized non-ICU patients, and symptomatic venous thromboembolism was documented in 27% and 2.2% of ICU and non-ICU patients respectively.74 Septic shock with the need for vasopressors has been reported in about 70% of COVID-19 patients admitted to an ICU.75,76 Despite the fact that TTS is described mainly in severe COVID-19, complete recovery was observed in 24 of the cases (80%). The treatment of TTS in COVID-19 should not be different from the usual management of TTS, with emphasis on the underlying disease. Because angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) was recognized early in the pandemic as a potential receptor for SARS-CoV-2 entry, the use of ACE inhibitors was postulated to cause deleterious effects in affected patients. However, recent trial results do not support the routine discontinuation of these drugs among patients with mild or moderate COVID-19.77 For this reason, the use of ACE inhibitors and beta blockers in TTS in the setting of COVID-19 seems to be reasonable when indicated.

Table 2.

Clinical course and outcomes

| Outcome | Mechanical ventilation | Mechanical circulatory support | Inotropic support | Complications | Study (first author) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Recovery | Y | N | Y | QT prolongation | Bapat15 |

| Recovery | N | N | Y | LV thrombi | Bernardi16 |

| Recovery | N | N | N | — | Bhattacharyya17 |

| Recovery | Y | N | Y | Shock | Bottiroli18 |

| Recovery | Y | V-V ECMO | Y | QT prolongation | Chao19 |

| Recovery | N | N | N | — | Dabbagh20 |

| Death | Y | N | Y | Shock | Dave21 |

| Recovery | Y | N | Y | Shock | Faqihi22 |

| Recovery | Y | N | Y | QT prolongation | Gomez23 |

| Death | N | N | Y | Shock, acute ischemic stroke | Kariyanna24 |

| Recovery | Y | N | Y | Shock | Khalid25 |

| Recovery | Y | N | Y | QT prolongation | Manzur-Sandoval26 |

| Recovery | N | N | N | — | Meyer27 |

| Recovery | N | N | Y | Shock | Minhas28 |

| Recovery | N | N | N | QT prolongation | Moderato29 |

| Recovery | Y | N | N | QT prolongation | Nguyen30 |

| Recovery | N | N | N | — | Oyarzabal31 |

| Death | Y | N | Y | Shock | Panchal32 |

| Recovery | N | N | N | QT prolongation | Pasqualetto33 |

| Death | Y | N | Y | — | |

| Recovery | N | N | N | — | |

| Recovery | N | N | N | — | Roca34 |

| Recovery | N | N | N | — | Sala35 |

| Death | Y | N | Y | — | Sang36 |

| Recovery | N | N | N | Atrial fibrillation | Sattar37 |

| Recovery | N | N | N | — | Solano-López38 |

| Recovery | N | N | N | — | Taza39 |

| Death | Y | N | Y | — | Titi40 |

| Recovery | Y | N | Y | Ventricular tachycardia | Tsao41 |

| Recovery | Y | N | N | QT prolongation | Van Osch42 |

LV, left ventricle; N, no; V-V ECMO, venous–venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; Y, yes.

Quarantine-Induced TTS

Another scenario in which TTS may be encountered in the COVID-19 era is related to the subsequent increase in mental stress, particularly during quarantine and self-isolation. People in quarantine report a high prevalence of depression, stress, insomnia, and anxiety, brought on by the long duration of quarantine, fear of infection, frustration, and inadequate supplies.78 The fact that many of the self-isolated individuals are elderly (with quarantining intended to protect themselves from the disease) may directly affect the incidence of TTS, as it predominantly affects elderly women. Three retrospective studies aimed to evaluate the changes in TTS incidence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Delmas et al. reported no increase in the incidence from March 1 to April 15, 2020 compared to the same period in previous years (5 patients vs 4-8 patients).79 In another single-centre study in Lombardy during the pandemic peak in Italy, 11 patients were diagnosed as having TTS from February to May 2020, compared to 3 cases during the same months of 2019.80 Finally, the study by Jabri et al.81 demonstrated a higher TTS incidence among patients admitted with suspected acute coronary syndrome between March 1 and April 30, 2020, with a total of 20 (7.8%), compared to the corresponding timeline in pre-pandemic years (5-12 patients; proportion range: 1.5%-1.8%) The difference in the results between the studies may be related to differences in quarantine policies, the social status of the study population, length of the study period, and the effect of the pandemic on the particular region (eg, Lombardy was a region with one of the worst COVID-19–related situations in Italy). It is reasonable to assume that the mental stress resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and its medical, social, and economic implications may constitute a potential trigger for TTS. Further registries are needed to determine the true change in incidence of TTS during the current pandemic.

Conclusion

TTS may be encountered in COVID-19 as a complication of the infection, or secondary to the overwhelming stress. The high rates of complications reported may be related to the undelying severe infection and not directly to the cardiomyopathy. Diagnosis may be challenging in this era, as biomarkers are not reliable for this purpose, and coronary angiography is often avoided. We suggest performing echocardiography in patients with COVID-19, using handheld devices to minimize contact with infected patients. The use of coronary angiography may be appropriate in high-risk patients with ongoing chest pain or dyspnea, episodes of ventricular tachycardia, or extremely elevated NP levels. Otherwise, routine management and repeated echocardiography are recommended, as most reported cases exhibited full cardiac function recovery. Treatment of TTS should be based on managing the underlying disease. The use of ACE inhibitors is appropriate when indicated, as these medications were shown to be safe among COVID-19 patients. Stress-induced Takotsubo is likely a reasonable consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic, due to the accompanying stress of self-isolation and quarantine, but large studies from various countries are needed to determine the trend in TTS incidence worldwide.

Funding Sources

The authors have no funding sources to declare.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Footnotes

Ethics Statement: The research reported in this paper adhered to general ethical guidelines.

See page 5 for disclosure information.

References

- 1.Wittstein IS, Thiemann DR, Lima JA, et al. Neurohumoral features of myocardial stunning due to sudden emotional stress. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:539–548. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tmplin C, Ghadri JR, Diekmann J, et al. Clinical features and outcomes of takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:929–938. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyon AR, Bossone E, Schneider B, et al. Current state of knowledge on Takotsubo syndrome: a position statement from the Taskforce on Takotsubo Syndrome of the Heart Failure Association of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur J Heart Fail. 2016;18:8–27. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ghadri JR, Wittstein IS, Prasad A, et al. International expert consensus document on takotsubo syndrome (part i): clinical characteristics, diagnostic criteria, and pathophysiology. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:2032–2046. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medina de Chazal H, Del Buono MG, Keyser-Marcus L, et al. Stress cardiomyopathy diagnosis and treatment: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72:1955–1971. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson HM, Cheyne L, Brown PAJ, et al. Characterization of the myocardial inflammatory response in acute stress-induced (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2018;3:766–778. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Randhawa MS, Dhillon AS, Taylor HC, Sun Z, Desai MY. Diagnostic utility of cardiac biomarkers in discriminating Takotsubo cardiomyopathy from acute myocardial infarction. J Card Fail. 2014;20:377. e25-31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pelliccia F, Kaski JC, Crea F, Camici PG. Pathophysiology of takotsubo syndrome. Circulation. 2017;135:2426–2441. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.027121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akashi YJ, Nef HM, Lyon AR. Epidemiology and pathophysiology of Takotsubo syndrome. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2015;12:387–397. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pelliccia F, Greco C, Vitale C, et al. Takotsubo syndrome (stress cardiomyopathy): an intriguing clinical condition in search of its identity. Am J Med. 2014;127:699–704. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kato K, Lyon AR, Ghadri JR, Templin C. Takotsubo syndrome: aetiology, presentation and treatment. Heart. 2017;103:1461–1469. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2016-309783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sandoval Y, Januzzi JL, Jr, Jaffe AS. Cardiac troponin for assessment of myocardial injury in COVID-19: JACC review topic of the week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:1244–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.06.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giustino G, Pinney SP, Lala A, et al. Coronavirus and cardiovascular disease, myocardial injury, and arrhythmia: JACC focus seminar. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:2011–2023. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.08.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madjid M, Safavi-Naeini P, Solomon SD, Vardeny O. Potential effects of coronaviruses on the cardiovascular system: a review. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5:831–840. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.1286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bapat A, Maan A, Heist EK. Stress-induced cardiomyopathy secondary to COVID-19. Case Rep Cardiol. 2020;2020 doi: 10.1155/2020/8842150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bernardi N, Calvi E, Cimino G, et al. COVID-19 pneumonia, takotsubo syndrome, and left ventricle thrombi. JACC Case Rep. 2020;2:1359–1364. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bhattacharyya PJ, Attri PK, Farooqui W. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in early term pregnancy: a rare cardiac complication of SARS-CoV-2 infection. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-239104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bottiroli M, De Caria D, Belli O, et al. Takotsubo syndrome as a complication in a critically ill COVID-19 patient. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7:4297–4300. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chao CJ, DeValeria PA, Sen A, et al. Reversible cardiac dysfunction in severe COVID-19 infection, mechanisms and case report. Echocardiography. 2020;37:1465–1469. doi: 10.1111/echo.14807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dabbagh MF, Aurora L, D'Souza P, et al. Cardiac tamponade secondary to COVID-19. JACC Case Rep. 2020;2:1326–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dave S, Thibodeau JT, Styrvoky K, Bhatt SH. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a coronavirus disease-2019-positive patient: a case report. A A Pract. 2020;14:e01304. doi: 10.1213/XAA.0000000000001304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Faqihi F, Alharthy A, Alshaya R, et al. Reverse takotsubo cardiomyopathy in fulminant COVID-19 associated with cytokine release syndrome and resolution following therapeutic plasma exchange: a case-report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2020;20:389. doi: 10.1186/s12872-020-01665-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gomez JMD, Nair G, Nanavaty P, et al. COVID-19-associated takotsubo cardiomyopathy. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-236811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kariyanna PT, Chandrakumar HP, Jayarangaiah A, et al. Apical takotsubo cardiomyopathy in a COVID-19 patient presenting with stroke: a case report and pathophysiologic insights. Am J Med Case Rep. 2020;8:350–357. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khalid Y, Dasu N, Dasu K. A case of novel coronavirus (COVID-19)-induced viral myocarditis mimicking a Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. HeartRhythm Case Rep. 2020;6:473–476. doi: 10.1016/j.hrcr.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manzur-Sandoval D, Carmona-Levario P, García-Cruz E. Giant inverted T waves in a patient with COVID-19 infection. Ann Emerg Med. 2021;77:264–267. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.07.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer P, Degrauwe S, Delden CV, Ghadri JR, Templin C. Typical takotsubo syndrome triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1860. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Minhas AS, Scheel P, Garibaldi B, et al. Takotsubo syndrome in the setting of COVID-19. JACC Case Rep. 2020;2:1321–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moderato L, Monello A, Lazzeroni D, et al. Sindrome Takotsubo in corso di polmonite da SARS-CoV-2: una possibile complicanza cardiovascolare [Takotsubo syndrome during SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia: a possible cardiovascular complication] G Ital Cardiol (Rome) 2020;21:417–420. doi: 10.1714/3359.33323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nguyen D, Nguyen T, De Bels D, Castro Rodriguez J. A case of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy with COVID 19. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;21:1052. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeaa152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Oyarzabal L, Gómez-Hospital JA, Comin-Colet J. Tako-tsubo syndrome associated with COVID-19. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed) 2020;73:846. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2020.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Panchal A, Kyvernitakis A, Biederman R. An interesting case of COVID-19 induced reversed takotsubo cardiomyopathy and insight on cardiac biomarkers. Cureus. 2020;12:e11296. doi: 10.7759/cureus.11296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pasqualetto MC, Secco E, Nizzetto M, et al. Stress cardiomyopathy in COVID-19 disease. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7 doi: 10.12890/2020_001718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roca E, Lombardi C, Campana M, et al. Takotsubo syndrome associated with COVID-19. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. 2020;7 doi: 10.12890/2020_001665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sala S, Peretto G, Gramegna M, et al. Acute myocarditis presenting as a reverse Tako-Tsubo syndrome in a patient with SARS-CoV-2 respiratory infection. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1861–1862. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sang CJ, 3rd, Heindl B, Von Mering G, et al. Stress-induced cardiomyopathy precipitated by COVID-19 and influenza A coinfection. JACC Case Rep. 2020;2:1356–1358. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.05.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sattar Y, Connerney M, Ullah W, et al. COVID-19 presenting as takotsubo cardiomyopathy complicated with atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2020;29 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcha.2020.100580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solano-López J, Sánchez-Recalde A, Zamorano JL. SARS-CoV-2, a novel virus with an unusual cardiac feature: inverted takotsubo syndrome. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:3106. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Taza F, Zulty M, Kanwal A, Grove D. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy triggered by SARS-CoV-2 infection in a critically ill patient. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-236561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Titi L, Magnanimi E, Mancone M, et al. Fatal Takotsubo syndrome in critical COVID-19 related pneumonia. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2020;51 doi: 10.1016/j.carpath.2020.107314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsao CW, Strom JB, Chang JD, Manning WJ. COVID-19-associated stress (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;13 doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.120.011222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.van Osch D, Asselbergs FW, Teske AJ. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in COVID-19: a case report. Haemodynamic and therapeutic considerations. Eur Heart J Case Rep. 2020;4:1–6. doi: 10.1093/ehjcr/ytaa271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hegde S, Khan R, Zordok M, Maysky M. Characteristics and outcome of patients with COVID-19 complicated by Takotsubo cardiomyopathy: case series with literature review. Open Heart. 2020;7 doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2020-001360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Giustino G, Croft LB, Oates CP, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:628–629. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dweck MR, Bularga A, Hahn RT, et al. Global evaluation of echocardiography in patients with COVID-19. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;21:949–958. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeaa178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.De Giorgi A, Fabbian F, Pala M, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and acute infectious diseases: a mini-review of case reports. Angiology. 2015;66:257–261. doi: 10.1177/0003319714523673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cappelletti S, Ciallella C, Aromatario M, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy and sepsis. Angiology. 2017;68:288–303. doi: 10.1177/0003319716653886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lozano A, Bastante T, Salamanca J, et al. Tako-tsubo cardiomyopathy triggered by influenza A virus infection. Int J Cardiol. 2014;174:e52–e53. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Buzon J, Roignot O, Lemoine S, et al. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy triggered by influenza A virus. Intern Med. 2015;54:2017–2019. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.54.3606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Elikowski W, Małek-Elikowska M, Lisiecka M, Trypuć Z. Mozer-Lisewska I. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy triggered by influenza B. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2018;45:67–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Golfeyz S, Kobayashi T, Aoi S, Harrington M. Possible association of influenza A infection and reverse takotsubo syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2018;11 doi: 10.1136/bcr-2018-226289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nakamura M, Nakagaito M, Hori M, Ueno H, Kinugawa K. A case of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy with cardiogenic shock after influenza infection successfully recovered by IMPELLA support. J Artif Organs. 2019;22:330–333. doi: 10.1007/s10047-019-01112-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Faircloth EL, Memon S. Stressing out from the flu: a case of influenza A-associated transient cardiomyopathy. Cureus. 2019;11:e4918. doi: 10.7759/cureus.4918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Singh K, Marinelli T, Horowitz JD. Takotsubo cardiomyopathy after anti-influenza vaccination: catecholaminergic effects of immune system. Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31:1627. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2013.06.039. e1-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Santoro F, Ieva R, Ferraretti A, et al. Tako-Tsubo cardiomyopathy after influenza vaccination. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:e51–e52. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2013.03.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wittstein IS. The sympathetic nervous system in the pathogenesis of takotsubo syndrome. Heart Fail Clin. 2016;12:485–498. doi: 10.1016/j.hfc.2016.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Abraham J, Mudd JO, Kapur NK, et al. Stress cardiomyopathy after intravenous administration of catecholamines and beta-receptor agonists. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53:1320–1325. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kido K, Guglin M. Drug-induced takotsubo cardiomyopathy. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2017;22:552–563. doi: 10.1177/1074248417708618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Paur H, Wright PT, Sikkel MB, et al. High levels of circulating epinephrine trigger apical cardiodepression in a β2-adrenergic receptor/Gi-dependent manner: a new model of Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2012;126:697–706. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.111591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gubbi S, Nazari MA, Taieb D, Klubo-Gwiezdzinska J, Pacak K. Catecholamine physiology and its implications in patients with COVID-19. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:978–986. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30342-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boonen E, Vervenne H, Meersseman P, et al. Reduced cortisol metabolism during critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1477–1488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tan T, Khoo B, Mills EG, et al. Association between high serum total cortisol concentrations and mortality from COVID-19. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8:659–660. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30216-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wickboldt N, Pache JC, Dietrich PY, et al. Takotsubo syndrome secondary to adrenal adenocarcinoma: cortisol as a possible culprit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:1061–1062. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.186.10.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sakihara S, Kageyama K, Nigawara T, Kidani Y, Suda T. Ampulla (takotsubo) cardiomyopathy caused by secondary adrenal insufficiency in ACTH isolated deficiency. Endocr J. 2007;54:631–636. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k07-012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nguyen TH, Neil CJ, Sverdlov AL, et al. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic protein levels in takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:1316–1321. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Doyen D, Moceri P, Chiche O, et al. Cardiac biomarkers in Takotsubo cardiomyopathy. Int J Cardiol. 2014;174 doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gao L, Jiang D, Wen XS, et al. Prognostic value of NT-proBNP in patients with severe COVID-19. Respir Res. 2020;21:83. doi: 10.1186/s12931-020-01352-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Staedtke V, Bai RY, Kim K, et al. Disruption of a self-amplifying catecholamine loop reduces cytokine release syndrome. Nature. 2018;564:273–277. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0774-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Alashi A, Isaza N, Faulx J, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of patients with takotsubo syndrome: incremental prognostic value of baseline left ventricular systolic function. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.120.016537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dias A, Franco E, Rubio M, et al. Usefulness of left ventricular strain analysis in patients with takotsubo syndrome during acute phase. Echocardiography. 2018;35:179–183. doi: 10.1111/echo.13762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stöbe S, Richter S, Seige M, et al. Echocardiographic characteristics of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020;109:1549–1566. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01727-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ghadri JR, Cammann VL, Jurisic S, et al. A novel clinical score (InterTAK diagnostic score) to differentiate takotsubo syndrome from acute coronary syndrome: results from the International Takotsubo Registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1036–1042. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Reper PA, Oguz F, Henrie J, Horlait G. Takotsubo syndrome associated with COVID-19: and the InterTAK diagnosis score? JACC Case Rep. 2020;2:1835. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccas.2020.07.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bikdeli B, Madhavan MV, Jimenez D, et al. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75:2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Arentz M, Yim E, Klaff L, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of 21 critically ill patients with COVID-19 in Washington State. JAMA. 2020;323:1612–1614. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, et al. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region—case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2012–2022. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2004500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lopes RD, Macedo AVS, de Barros E, Silva PGM, et al. Effect of discontinuing vs continuing angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin ii receptor blockers on days alive and out of the hospital in patients admitted with COVID-19: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2021;325:254–264. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.25864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395:912–920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Delmas C, Bouisset F, Lairez O. COVID-19 pandemic: no increase of takotsubo syndrome occurrence despite high-stress conditions. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7:2143–2145. doi: 10.1002/ehf2.12871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Barbieri L, Galli F, Conconi B, et al. Takotsubo syndrome in COVID-19 era: Is psychological distress the key? J Psychosom Res. 2021;140 doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Jabri A, Kalra A, Kumar A, et al. Incidence of stress cardiomyopathy during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.14780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]