Abstract

Racist policies and inequity are prevalent in society; this includes higher education institutions. Many behavior-analytic training programs have been complicit in omitting cultural humility and antiracist ideas from their curricula and institutional practices. As societal demands for allyship and transformational change increase, programs must rise to the challenge and act as agents of change in our clinical, professional, and personal communities. The current article offers a multitude of strategies for institutions to develop an antiracist and multicultural approach. These recommendations encompass policies that may be promoted at the following levels: (a) in organizational infrastructure and leadership, (b) within curricula and pedagogy, (c) in research, and (d) with faculty, students, and staff.

Keywords: antiracism, antiracist, behavior analysis, cultural competency, diversity, faculty development, graduate training, inclusion, multiculturalism

For centuries, racist policies have governed our institutions, and the ivory tower is not exempt from this (Mosley & Bellamy, 2020). The rise of the Black Lives Matter movement since its inception in 2013 and the demand for transformational change have made these policies and their outcomes impossible to ignore. In order to actualize equity for Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC), it is not enough to say we are “not racist.” Statements such as this are to be complicit with racist policy rather than to ensure policies create equity, and to claim one is not racist allows one to do nothing, reinforcing the status quo’s continuation (Kendi, 2019). Instead, we must focus our efforts on reimagining institutional policies in ways that are antiracist. Among other things, antiracism involves developing policies that reduce racial inequity and produce equal opportunity among racial groups (Kendi, 2019).

An important step in developing antiracist programs is to become educated and teach others on topics of diversity, multicultural competence, and antiracism as a foundation to actively practicing cultural humility. Our field has historically ignored these critical skills, and many practitioners lack training and expertise in working with diverse populations. Accordingly, there are limited structures and very little content on antiracism and multiculturalism within most behavior-analytic training programs (Conners, Johnson, Duarte, Murriky, & Marks, 2019).

The purpose of the current article is to provide potential recommendations for reimagining graduate training programs in behavior analysis. In doing so, we hope to promote antiracist and multicultural approaches to education in our field. In a university setting, antiracist policies can be promoted at all levels, including (a) in the organizational infrastructure and leadership, (b) within curricula and pedagogy, (c) in research, and (d) with faculty, students, and staff. Table 1 presents an overview of antiracism strategies for graduate training programs in behavior analysis across all of these levels.

Table 1.

Antiracism Strategies for Graduate Training Programs in Behavior Analysis

| Category | Strategies |

|---|---|

| Organizational infrastructure & overall process |

Create a mission and vision with antiracism as a core value. Recruit a director of diversity. Delegate the steering committee to enact policy changes. Create initiatives in the strategic plan with systems of accountability. Create campus-wide diversity/antiracism initiative campaigns. Come to a consensus about core values among leadership inspiration. Divest funds from the police and reinvest them in other social programs. |

|

Curricula & pedagogy: Instructor approach & self-awareness |

Self-reflect on attitudes and reactions to diversity-related content. Acknowledge systems of privilege and oppression in education. Bring the experiences of diverse individuals to the forefront. Create space for students to feel comfortable sharing experiences. Evaluate course material to prevent potential alienation. Guide students in navigating the university’s cultural landscape. Counter stereotypes and call out personal privilege. Address barriers to resource accessibility by providing referrals (e.g., writing center, career center). Provide reasonable ancillary support (e.g., meetings, feedback). Be flexible with submission/presentation style. |

|

Curricula & pedagogy: Coursework on antiracism, multiculturalism, & diversity |

Embed antiracism/diversity within all courses in the curriculum. Teach cultural competence, always striving for humility. Use a behavioral approach for addressing bias and racism (e.g., behavior assessment, intervention, monitoring). Emphasize process over content. Establish pedagogical goals at the outset of the course. Be skilled in resolving conflicts and managing emotions/tensions triggered. Ensure participation from all students (e.g., anonymous). Incorporate student goals and desired experiences into the course. Listen, without interruption, to BIPOC experiences. Accept accountability when you make mistakes. |

|

Curricula & pedagogy: Course design & curricular modifications |

Embed diversity content throughout the course (e.g., objectives, lectures, readings, assignments, self-reflection exercises) and ensure the promotion of inclusion. Use class time creatively (e.g., applied activities, role-play, critical thinking, interteaching). Require interaction with different students. Create a syllabus diversity statement. Address the role of social norms in the sustainability of treatment outcomes. |

| Curricula & pedagogy: Practicum |

Teach and practice cultural competence. Have students gain experience with diverse populations. Use reflective exercises about their and others’ experiences. Teach construction of culturally relevant intervention goals. Translate content into the client’s native language. Monitor students’ behavior toward different backgrounds. Shape students’ verbal/nonverbal behavior to improve their therapeutic relationships with clients. Require fieldwork sites and supervisors to sign an acknowledgment of the university’s diversity policy and to agree to offer opportunities for students to practice cultural humility. Ask students to evaluate their training site’s commitment to multiculturalism. Require discussions of cultural variables during case conceptualization presentations. |

| Research |

Report the races/languages of participants and researchers. Conduct research on cultural diversity and/or with more culturally diverse individuals. Overcome mistrust and address concerns of BIPOC. Recognize the role that oppression, privilege, and power may play in the relationship between the researcher and the participants. View culturally diverse research participants as a source of information. Support BIPOC involvement in conducting research. |

| Faculty, staff, & students |

Require continuous trainings in antiracism and diversity. Have BIPOC and White individuals do separate breakout groups (e.g., to discuss relevant and personal issues of marginalization). Create an antiracist culture (e.g., value learning about cultures, listen nonjudgmentally to others’ experiences, provide supportive spaces and platforms for BIPOC to express their feelings). Instill a culture where it is safe to speak up with a system for submitting concerns, and investigate inequitable policies when they are exposed. Involve marginalized individuals in the development and use of assessments to identify areas of marginalization and oppression. Ensure counseling centers have sufficient BIPOC counselors on staff. Have separate diversity committees for faculty, staff, and students. Have faculty and student committees cosponsor some events. |

|

Faculty & staff: Recruitment & hiring |

Recruit and hire more BIPOC faculty and staff. Check the university’s resources/funding related to diversity. Increase community outreach efforts by linking the university with more community organizations. Reach out to and direct job advertisements to diverse groups. Ask faculty to identify individuals from underrepresented groups that they could personally encourage to apply. Include a strong diversity statement, using inclusive language in hiring announcements, and mention inclusive benefits. Provide candidates from underrepresented groups with resources and guidance such as sessions that review employment opportunities, help for the online job application completion process, and connection to local services such as résumé workshops. Train human resources staff to provide welcoming, friendly, and personable services. Create a dual-career program that the human resources department provides by giving job search assistance to applicants’ spouses. Ensure the hiring committee is trained about implicit bias prior to the candidate interviews and evaluation process. Have the hiring committee attend to the demographics of applicants who are suggested for progression from one phase of the hiring process to the next and require a rationale for applicants who are not progressed. Ask applicants to provide their personal diversity statement in application materials, and ask questions related to diversity during candidate interviews. |

|

Faculty & staff: Retention |

Provide equitable salaries related to the position. Outline expectations and the tenure/promotion process during interviews. Provide clear verbal and written feedback on performance evaluations on whether faculty are on track for retention, tenure, and promotion. Pair new faculty with a seasoned faculty mentor. Recognize that teaching evaluations can be biased, especially for faculty teaching antiracist topics. Have opportunities for BIPOC to provide mutual support, share experiences, and engage in social networking with diverse individuals. Recognize and compensate the extra activities of BIPOC or give them more weight during promotion/tenure evaluations. Avoid placing the burden of educating others on diversity on BIPOC. |

|

Faculty & staff: Advancement |

Ensure an unbiased faculty advancement process by training reviewers on implicit bias. Ensure that the faculty reviewing materials are aware of services that may have affected a faculty’s scholarly activity (e.g., mentoring underrepresented students, serving on diversity committees). Ensure accountability for the university’s mission of inclusive excellence for all faculty. |

|

Faculty & staff: White allyship |

Build supportive relationships with BIPOC, as well as White individuals doing antiracist work. Accept critical feedback when mistakes (e.g., microaggressions) are made or about whether White individuals’ behaviors are aligned with those of an antiracist ally. Ensure BIPOC authors’ work is not overshadowed by one’s own in collaborations. Acknowledge/cite the contributions of BIPOC to a subject matter. Forgo scholarly activity for service related to diversity. Voice concerns regarding policies that create inequality. Commit to understanding how intersectionality plays a role in racism. |

|

Students: Recruitment & admissions |

Increase the recruitment of BIPOC in graduate programs. Implement policies that ensure equity during the admissions process. Use alternatives to the GRE. Offer workshops to BIPOC for completing applications and securing financial aid. |

|

Students: Retention |

Offer mentorship opportunities. Provide tools for academic and professional success. Offer scholarships for BIPOC who demonstrate excellence. |

| Alumni |

Provide continued mentorship of alumni for professional development. Provide opportunities for alumni to mentor current students. Offer social networking opportunities specific to BIPOC. |

Note. BIPOC = Black, Indigenous, and people of color; GRE = Graduate Record Examination.

Organizational Infrastructure and Overall Process

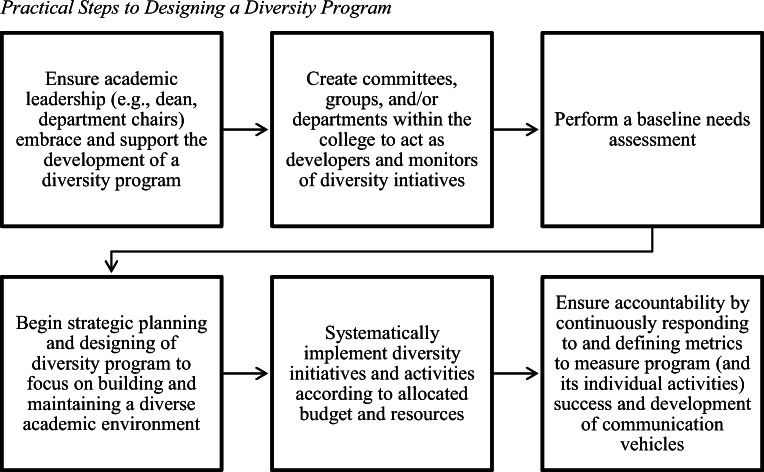

Practical steps can be taken in a university during the process of building multiculturalism, diversity, inclusion, and antiracism (see Figure 1). One step is to have leadership that is supportive of the systemic evaluation of policies and the advancement of new policies (Harper & Hurtado, 2007; Milem, Chang, & Antonio, 2005). For example, some universities have a diversity director who has formed a cabinet with the goal of developing university-wide antiracism policies (Russell, 2019). At the level of individual schools/colleges within the university, the dean, departments, and department chairs must embrace equity among racial groups (Nkansah, Youmans, Agness, & Assemi, 2009). With leadership support, a steering committee could act in the role of policy change agents (Nkansah et al., 2009) at the level of the university, school/college, or both.

Figure 1.

Practical Steps to Designing a Diversity Program. Note. These steps were adapted from Nkansah et al. (2009), who initially designed these steps for colleges/schools of pharmacy.

The antiracist university’s and department’s mission and vision could demonstrate and communicate that diversity and antiracism are core values by including them, for example, in written materials such as handbooks, marketing materials, and websites (Nkansah et al., 2009). These statements provide direction for diversity initiatives (Nkansah et al., 2009). It is helpful for the steering committee to create a strategic plan for addressing racial equity within the organization’s systems and policies (Nkansah et al., 2009). The steering committee must anticipate resistance from others in the university (Kezar, 2007). In addition to giving voice to all members of the academic community, baseline assessment data can help gain support and rationalize the need for a strategic plan (Kezar, 2007), as well as identify what initiatives should be included (Nkansah et al., 2009).

There are multiple goals of a strategic plan, such as (a) developing an understanding of the issues, (b) bringing attention to what differences there are with respect to race in the institution, and (c) creating racial equity (Kezar, 2007). The strategic plan could include the allocation and protection of monetary resources budgeted for initiatives (Pope, Reynolds, & Mueller, 2019). Having clearly defined and measurable goals allows progress to be monitored and provides the feedback and accountability necessary for refining university policies (Nkansah et al., 2009). Likewise, future funding may be made contingent on achieving desired outcomes (Pope et al., 2019). Additionally, campaigns for initiatives and showcasing successes may be helpful for building momentum (Kezar, 2007). Finally, giving entrepreneurial opportunities to faculty, staff, and students may motivate them to come up with new ideas (Williams & Clowney, 2007). For example, some universities have grants individuals can apply for and use toward innovative projects.

For antiracism to be a part of the culture, the leadership will need to inspire administration, faculty, and staff by helping them to come to a consensus about their core values, sort out values conflicts, and ensure that the desired cultural climate is embedded into the way the university’s systems operate (Kezar, 2007). In order to transform the university culture, the entire campus community needs to be engaged (Williams & Clowney, 2007). However, when a university claims to value diversity, the majority of the responsibility should be on the university to be acculturated to the students, rather than the other way around (Lundberg, 2007). This is more likely to increase student engagement (Hinton & Seo, 2013). For these reasons, leadership should attempt to cultivate appreciation, knowledge, and skills related to diversity and inclusion with existing administration, faculty, and staff (Williams & Clowney, 2007). Universities that are serious about this remove individuals from their positions who refuse or fail to meet expectations (Williams & Clowney, 2007). Likewise, universities may choose to divest funds from the police and reinvest them in other programs, such as community safety programs, crisis response teams, mental health counselors, materials that students need, and an equitable justice system (Abdullah, 2020). Overall, accountability is key to driving change (Williams & Clowney, 2007).

Cultural Humility

The field of applied behavior analysis (ABA) has reached an inflection point toward the development of new professionals. The increasing number of diverse clientele necessitates that clinicians demonstrate cultural competence (Fong, Ficklin, & Lee, 2017). It is imperative for graduate schools to have a curriculum that is decolonized and focuses on developing culturally humble students.

Cultural humility involves an individual humbling themselves and submitting to the ideals and practices of another’s culture by actively reminding themselves that they do not know everything (Conners, 2020). As it is used for training professionals in other disciplines such as social work, nursing, and education, Fisher-Borne, Cain, and Martin (2015) explained the framework of cultural humility as a lifelong process that demands accountability for learning and self-reflection at both the individual and institutional levels as it relates to systemic oppression. Culturally humble individuals accept that being culturally competent is a never-ending self-reflective process during which they will make many mistakes (Hook & Watkins Jr., 2015) and that it requires ongoing personal accountability (Fisher-Borne et al., 2015).

A culturally competent individual is one who can consume knowledge about policies, attitudes, traditions, and histories of diverse cultures, and then adequately apply that knowledge in a way that promotes the highest level of equity for corresponding cultures (Betancourt, Green, & Carrillo, 2002). Campinha-Bacote(2002) proposed a model indicating that becoming culturally competent is a continuous process, rather than an outcome, and it requires achieving an equal and intersectional usage of the five constructs of cultural awareness, cultural knowledge, cultural skill, cultural encounters, and cultural desire. Campinha-Bacote(2019) introduced a newer term in the research literature to indicate the integration of cultural competence with cultural humility, called “cultural competemility,” which refers to the concurrent infusion of the five constructs of cultural competence into cultural humility.

Standards created by the Multicultural Alliance for Behavior Analysis in 2013 laid out proposed areas of development for culturally competent behavior analysts (Fong & Tanaka, 2013). In general, these standards center on self-awareness, ethics and values, cross-cultural application, diverse work environments, and language diversity (Conners, 2020). Additional suggestions include confronting cultural bias, understanding cultural identity, and developing both an interpersonal and personal awareness of the intersection of culture and treatment methods (Fong, Catagnus, Brodhead, Quigley, & Field, 2016).

Clinicians must first evaluate their own cultural influence, the historical impact of that influence, and how their cultural upbringing evokes their overt and covert behavioral patterns, especially as it relates to others (Dennison et al., 2019) to practice cultural humility. They must become aware of faulty information about their and others’ cultures (Funchess, 2014) and create self-management programs to establish culturally humble repertoires (Wright, 2019). Once clinicians develop the skills to tact their own and others’ cultural contingencies, they may be better equipped to rise to the challenge of providing appropriate services to individuals of another culture, given the cultural overlap. With awareness and acceptance of their own level of competence, clinicians should seek out antiracist information independently, without placing the burden of training on BIPOC (Fong & Tanaka, 2013).

Curricula and Pedagogy

Instructor Approach and Self-Awareness

Faculty within the institution must adopt pedagogical approaches that promote cultural humility and antiracist ideas. Foremost, gaining insight into their personal attitudes toward diversity-related content inside and beyond the classroom (Hinton & Seo, 2013) will identify areas in which faculty need continued training, and serve as a catalyst to initiate efforts to recognize systems of privilege and oppression and develop pedagogy that brings the experiences of diverse individuals to the forefront of the educational experience. Instructors must recognize the diverse cultural backgrounds of their students and consider the potential contribution of incorporating the viewpoints of BIPOC to the overall educational quality of the class (Benuto, Casas, & O’Donohue, 2018). They must take great care to reflect on their own teaching methods to prevent potential alienation in the communication of course material and create a classroom environment where all students feel comfortable (Hinton & Seo, 2013). For example, when students share their experiences with racial and ethnic tensions, they must be made to feel comfortable to disclose their perspectives. As another example, when international students share experiences from their home countries that might be different from what the behavior-analytic ethics code finds acceptable (e.g., accepting gifts, dual relationships), instructors should use it as an opportunity to draw attention to the code’s shortcomings with respect to cultural understanding and ensure that students are made to feel comfortable in sharing these stories. These efforts to decolonize curricula and pedagogy are necessary and may be achieved by directly countering stereotypes, calling out personal privileges or experiences with marginalization, and inviting students to do the same, thereby directly challenging Western educational pedagogy (Kishimoto & Mwangi, 2009; St. Clair & Kishimoto, 2010).

To improve their relationships and establish trust with students, faculty may provide guidance to students for navigating the cultural landscape of the university (Hinton & Seo, 2013). For first-generation college students, a university education is highly valued, but as a result of structural barriers and students’ limited exposure to their availability, the resources necessary for success might be sparse (Hinton & Seo, 2013). The department chair or program director should ensure that individual faculty are aware of these barriers to accessibility (e.g., through quarterly or annual training), and communicate the availability of resources and support systems in multiple ways (e.g., emails, class announcements, faculty referrals) to ensure that all students are set up for success. This may include connecting students with university resources such as the career center or writing center or providing mentorship. It is possible that BIPOC students’ awareness that they are supported may facilitate their persistence and help-seeking behaviors. While upholding equitable standards of academic excellence and driving all students toward the same level of achievement (Hinton & Seo, 2013), faculty must focus on the safety and humanization of BIPOC individuals. Programs often make the mistake of focusing on the growth and enlightenment of White students; that is White supremacy, not antiracism (Oluo, 2019).

By investing in various levels of support for students, faculty will be able to identify cultural connections between the course material and the student body, and this will demonstrate to students that their presence in the classroom is of value to the program and to the field of behavior analysis (Hinton & Seo, 2013). BIPOC students may also require additional support on assignments (Fuentes, Zelaya, & Madsen, in press) due to systemic barriers (e.g., lack of resources, traditional syllabi favoring content that allows White students to interact with the content more easily than BIPOC) that have been placed on them throughout their educational history. Thus, instructors are encouraged to provide resources, reasonable ancillary support (e.g., review of additional drafts, one-on-one meetings, detailed feedback on both style and content), and flexibility in style (e.g., presentation formats, oral or written communication) to ensure equity and that gaps in students’ learning styles and communication repertoires do not interfere with their ability to demonstrate their understanding of the course’s content. Maintaining flexibility is a critical step in the decolonization of classrooms, as it indicates that the instructor accepts students’ individual styles, wherein submitted assignments and presentations look different from standard templates while nonetheless demonstrating competency and meeting all content requirements.

Coursework on Antiracism, Multiculturalism, and Diversity

Behavior-analytic graduate training programs may consider adding one or more introductory courses on antiracism, multiculturalism, diversity, and inclusion (Russell, 2019; St. Clair & Kishimoto, 2010; Williams & Clowney, 2007; Wright, 2019) and having this content be continuously embedded within every course in the curriculum. These courses build an understanding of critical concepts such as race, ethnicity, culture, and identity, while highlighting the realities of discrimination, privilege, and prejudice institutionally, and throughout everyday encounters (St. Clair & Kishimoto, 2010). Such courses can also acknowledge BIPOC who contributed to foundational theoretical perspectives but were never appropriately credited, as well as incorporate material into the coursework that centers the voices of marginalized and oppressed individuals. Intentionally focusing study on such topics advances the strength of the program by necessitating considerations for addressing emerging challenges and dynamics in socially relevant environments (Williams & Clowney, 2007). Additionally, these courses should consider approaches utilized in related fields that have additional expertise in addressing these topics. For example, the Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs (CACREP) requires that their accredited programs have an objective to “reflect current knowledge and projected needs concerning counseling practice in a multicultural and pluralistic society” (CACREP, 2015, p. 9).

St. Clair and Kishimoto (2010) explained that teaching antiracism falls along a continuum, and the topic cannot effectively be covered in one semester because students need time to process what they have learned. They described a three-level system composed of (a) delivering information, concepts, and vocabulary on current racial issues; (b) teaching students the skills and tools needed to analyze racism; and (c) creating opportunities for students to apply this analysis and commit to change while recognizing that dismantling and interrupting racism is a lifelong endeavor (St. Clair & Kishimoto, 2010). Self-reflection, as described by Wright (2019), may also be an important component to include in coursework on cultural humility. Specifically, Wright described the self-reflection component of cultural humility as a three-step self-management process, composed of developing a clear definition of a goal related to a practice, collecting and analyzing data on whether the goal is being met, and establishing consequences to create accountability. For example, to ensure institutional accountability, one would first create an operational definition for a goal, such as providing equitable and nondiscriminatory access to services to individuals of all socioeconomic statuses, races, and ethnicities. Then data would be collected to identify whether the goal is being met. Finally, consequences would be in place to ensure accountability, and data related to the goal could be publicly provided in staff meetings and organizational reports, resulting in positive reinforcement for meeting the goal or punishment (i.e., being perceived as discriminatory) for not meeting the goal (Wright, 2019).

One step that instructors can take to ensure a positive educational environment is establishing pedagogical goals at the outset of the course (Wagner, 2005). This includes emphasizing that the course will deconstruct normative notions and focus on diverse viewpoints of the same issue, unsettle what is “known” in order to challenge individuals’ understanding of their traditional frames of reference, and disrupt “us versus them” dichotomous thinking. It also includes recognizing that the process will be difficult for everyone, including the instructor. To ensure the participation of BIPOC who might otherwise remain silent, instructors may establish an expectation for participation (Wagner, 2005), and to ensure that students do not feel singled out in the process, instructors should consider requiring anonymized participation (e.g., online polls, sharing perspectives on flash cards that are redistributed to other students for a response). Additionally, the instructor may share power with the class by soliciting feedback from students about what they would like to gain from the course and incorporating these topics throughout the content (Wagner, 2005). This will allow the instructor to better understand the starting point for each student and elucidate students’ expectations for the course (Wagner, 2005).

Courses on antiracism and cultural humility must also emphasize process over content (Wagner, 2005), in that the process through which the content is analyzed stays consistent, whereas the instructional material (i.e., content) is tailored to the unique experiences of the students. The process for teaching such a course involves resolving conflict and managing emotional responses and tensions triggered by difficult conversations, as well as teaching basic conflict-resolution skills (Wagner, 2005). Presumably, to be good at this, the instructor would need to pay close attention to students’ nonverbal behaviors (e.g., body language, facial expressions, engagement in conversation, tone of voice) during difficult discussions in order to appropriately facilitate self-reflection, humility, and positive regard for one another’s experiences and perspectives.

Another point of consideration is the approach that White educators use when teaching antiracism and diversity-based courses. It is essential for White instructors to listen to BIPOC experiences without interruption and with acceptance, as well as hold themselves accountable in their communication (Utt & Tochluk, 2020). It is inevitable that instructors will make mistakes that may reduce trust and harm the student–teacher relationship, and so it is imperative that instructors maintain accountability in such situations by apologizing, learning from their mistakes, and committing to doing better (Utt & Tochluk, 2020).

Course Design and Curricular Modifications

When designing behavior-analytic curricula, instructors are encouraged to embed multiculturalism and diversity content into multiple aspects of their courses, including course objectives, lectures, readings, and assignments (Fuentes et al., in press; Pope et al., 2019). Instructors are encouraged to rethink how they teach and to use class time creatively (Hinton & Seo, 2013). For example, instructors could consider forgoing the traditional classroom lecture by carefully selecting course readings and assignments to be completed prior to class so that class time may be fully utilized for experiential and applied activities that incorporate students’ perspectives. Instructors may encourage students to interact with different students (Hinton & Seo, 2013) in an effort to increase opportunities for collaboration. This should be done with full consideration for individual students’ needs (e.g., planning for factors related to neurodiversity, mental health, social anxiety, or microaggressions experienced by BIPOC) and only after having created a classroom space where all students feel safe and comfortable interacting with one another. Instructors are further encouraged to use critical-thinking activities, interteaching, role-play scenarios, or other active-responding instructional techniques. Specifically, instructors might include prompts that allow students to share their diverse experiences or use vignettes that incorporate the need for a culturally competent approach. Instructors could also use instructional tools and strategies such as self-reflection exercises and cultural immersion activities throughout academic and clinical coursework to increase students’ awareness of their own biases, as well as those implicit in the field of ABA (Beaulieu, Addington, & Almeida, 2019; Conners et al., 2019). For example, instructors may incorporate assessments such as the Diversity Self-Assessment Tool (Montgomery, 2001) or the Multicultural Sensitivity Scale (Jibaja-Rusth, Kingery, Holcomb, Buckner, & Pruitt, 1994) as self-evaluation tools for themselves, staff, and students to better examine their understanding of diversity and multicultural sensitivity. The Georgetown University National Center for Cultural Competence (n.d.) provides a more comprehensive list of diversity assessment tools.

Another strategy for improving diversity and equity within courses is to include a diversity statement in all syllabi to indicate equity and diversity as guiding philosophies for coursework, the academic program, and the institution. Such a statement is important because it promotes accountability by requiring instructors to take action to ensure diverse and equitable approaches are incorporated into coursework and pedagogy (Gershfeld Litvak & Rue, 2020). Moreover, syllabi should be evaluated regarding whether content, such as readings, promotes inclusion and is accessible for all students (Fuentes et al., in press). For example, traditional syllabi may implicitly favor content that enables White students to have an easier experience with the content compared to BIPOC. Effective instructors use carefully selected course readings that are relevant to all students in the class and that demonstrate the utility of cultural sensitivity in behavior-analytic service provision. The use of such content facilitates relevant dialogue to increase students’ self-awareness and verbal repertoires for engaging with such content (Benuto et al., 2018). Creating these learning experiences may allow students to engage in difficult dialogue that may produce paradigm-shifting experiences (Pope et al., 2019). These course activities enhance a student’s professional and interpersonal skills and are more likely to help them produce meaningful therapeutic relationships once they enter the clinical realm. Specifically, instructors could ensure that real-life applications of conceptual and academic content use experiences with culturally diverse populations (Hinton & Seo, 2013).

To further promote cultural humility, clinical courses on behavioral assessment and intervention must be intentionally designed to recognize and address the role of differing social norms in the sustainability of treatment outcomes. For example, these courses could use a multitude of examples from various cultures to ensure that students learn to make culturally attuned clinical decisions (Wang, Kang, Ramirez, & Tarbox, 2019). Common areas of skill acquisition programs in which cultural competency is relevant include teaching nonverbal social behaviors (e.g., eye contact, facial expressions, greetings, touching others, personal space), teaching verbal behavior (e.g., form of greetings, sentence structure, conversations with elders vs. peers), and self-care skills (e.g., showering, toileting, dressing). However, clinicians should also avoid assuming that families from a given cultural background abide by specific cultural rules. An example of this would be pairing a Spanish-speaking clinician with a Spanish-speaking client and starting intervention without determining if their dialects are the same (Gershfeld Litvak & Rue, 2020). Instead, clinicians should provide a platform for families to state the cultural considerations they would like to be addressed (Gershfeld Litvak & Rue, 2020).

Practicum

The role of the practicum is to teach students to apply what is taught in the classroom to their work with clients. Thus, one goal of the practicum is to teach students to be good clinicians, and presumably, good clinicians are culturally competent and demonstrate cultural humility. Teaching and practicing cultural humility during practicum courses are crucial for ensuring effective clinical service delivery. For example, culture may influence stigmatization of diagnoses, whether services are sought out, the type of services requested, the presence or absence of support systems, and family dynamics during the provision of services (Fong et al., 2017).

One strategy for practicum courses is to require students to gain supervised clinical experience with diverse populations (Conners et al., 2019). Specifically, activities that require students to reflect on clients’ and their own cultural background and characteristics, to select culturally sensitive assessments, and to subsequently share their cultural encounters in group supervision settings could be required (Conners et al., 2019). One assessment that has already been adjusted for culture includes the Culturally Informed Functional Assessment Interview, which is used to bridge the gap between clients and their clinicians who have different cultural backgrounds (Tanaka-Matsumi, Seiden, & Lam, 1996). Effective supervisors create spaces where trainees are comfortable discussing cultural experiences (Conners et al., 2019).

Practicum courses can teach students to reflect on how culture plays a role in individualized interventions. For example, clinicians should be knowledgeable of cultural contingencies within their clients’ community (Tanaka-Matsumi et al., 1996) so that they can use this information to make intervention goals that are culturally relevant. Culture should also be considered in the development of individualized caregiver training (Conners et al., 2019). When possible, behavior-analytic content can be translated into the family’s native language to support treatment implementation (Conners et al., 2019), and the intervention should conform to the language of the client, as the inability to communicate often leads to problem behaviors. Actively seeking bilingual translators or supervisors early in the intake process can increase rapport between the clinician and the caregivers and ensures needs are being accurately communicated and met (Dennison et al., 2019). This also includes Black clinicians using African American Vernacular English to communicate with families who use this language (Lyiscott, 2018).

Additionally, a skilled clinician takes the extra time to listen and acknowledge the disparities a family may express and seeks to overcome the sociocultural differences between them and the family (Dennison et al., 2019). Oftentimes, this can include asking specifically whether their training programs interfere with anything in regard to their client’s culture. In doing so, a clinician recognizes that some behaviors perceived as inappropriate by them may be appropriate behaviors in their client’s environment (Beaulieu et al., 2019). For example, toileting, eating, and sleeping routines tend to vary by culture (Parry-Cruwys, 2020).

Supervisors could monitor students’ behavior toward individuals of different backgrounds and provide guidance to help shape students’ verbal and nonverbal behavior to improve therapeutic relationships (Conners et al., 2019). Because supervisors will need to train their staff in cross-cultural practice and given that most behavior analysts have received very little training in working with populations from diverse backgrounds (Beaulieu et al., 2019), they must identify and engage in opportunities to learn about multiculturalism to become better equipped to carry out their responsibilities. Supervisors should seek out training in order to be in compliance with Codes 5.01 and 5.04 of the ethical code of the Behavior Analyst Certification Board (BACB). This includes supervisory competence and designing effective supervision and training (BACB, 2018).

Practicum courses could require that off-site supervisors sign an agreement to acknowledge the university’s diversity policy and engage in exercises that highlight the role of multicultural variables in clinical service provision within their supervision of the student. In addition, students could be asked to evaluate their training site’s commitment and implementation of culturally responsive interventions, clinical training, and supervisory practices; these data could be used by the university’s clinical training program to determine the continuation of a relationship with each external practicum site or a need for remediation. These measures would promote accountability within the behavior-analytic service delivery community. To complement on-site experiences, faculty who are teaching practicum courses could proactively promote the value of cultural humility by requiring that students incorporate discussions of diversity and culture-specific variables throughout all case conceptualization presentations within their clinical training coursework.

Research

Diversity in research is not simply understudied; its necessity for consideration is generally up for debate (Li, Wallace, Ehrhardt, & Poling, 2017). In fact, cultural information such as race/ethnicity and linguistic information has been found to be reported in only 3%–10.7% of studies published in behavioral journals (Beaulieu et al., 2019; Brodhead, Durán, & Bloom, 2014; Li et al., 2017). These low percentages indicate a general consensus to a colorblind-like approach to conducting research. Leaving these studies colorblind can not only interfere with external validity but also uphold and promote racist tactics, leading to an overall medical apartheid on BIPOC (Washington, 2006). The medical apartheid on BIPOC individuals describes the stark difference in the way medical treatment is given to BIPOC and White individuals. It demonstrates racism’s two-faced effect on medical experimentation and treatment, which leads to BIPOC receiving less or inconsistent treatment based on faulty experimental conclusions and the belief that BIPOC are inferior (Washington, 2006). With this in mind, researchers should report the races of and languages used by participants. Likewise, the races of the researchers may also be reported. Reporting the races of the researchers and participants recognizes the power and privilege researchers may hold over the study’s participants (Pope et al., 2019).

Graduate programs can strive for some research to be focused on issues of cultural diversity and/or be conducted with more culturally diverse individuals (Pope et al., 2019). Although programs may have greater access to more affluent communities, researchers need to consciously choose to create equity within a study over opportunities of pragmatism (Li et al., 2017). This includes venturing outside of their immediate environment to include a wider range of participants in their research studies. This is increasingly difficult due to the rightful mistrust BIPOC have of the research community. For example, some Black individuals are aware that Black children are more likely to be used in more harmful studies than therapeutic ones or ones with less invasive methods (Washington, 2006). One way for researchers to overcome this mistrust is to be open to hearing the concerns of BIPOC and willing to acknowledge past mistakes of research (Washington, 2006). Another way is to abide by the BACB’s ethical code with increased sensitivity, communication, and openness, especially in regard to appropriate informed consent (Code 9.03), by providing constant reminders of the right to drop out of the study (BACB, 2018).

Once BIPOC consent to participate, researchers should consider their learning histories (Li et al., 2017), as they may have a history of oppression that could interfere with independent variables or contribute to results. For example, if the purpose of a research study is to explore different methods to teach participants to ask for help from authoritative figures, the history of oppression between certain authoritative figures (i.e., police officers) and BIPOC may contribute to results. Additionally, researchers should recognize the role that oppression, privilege, and power may play in the relationship between the researcher and the participants (Pope et al., 2019). Students should be taught to consider research participants as a source of information (Pope et al., 2019), not a “colorless” element or data point. Open-ended indirect assessments can be used to gather information from participants about aspects that could create limitations to a study so that the researcher may be better informed and work to actively adjust research methods (Beaulieu et al., 2019). Finally, graduate schools need to support BIPOC students’ involvement in research, as the benefits of doing so can potentially open the doors to student retention and increased admissions of BIPOC.

Faculty, Staff, and Students

In the movement toward an antiracist program, campus-wide training efforts on social justice can be implemented (Pope et al., 2019). For instance, all faculty, staff, and students can complete a training on antiracism. For one example, see the 6-hr online training by the Diversity and Resiliency Institute of El Paso (2020). An online training of this sort could be required to be completed by all students in one of their first semester courses or during an orientation, as well as by all newly hired faculty and staff. However, training in diversity-related competencies should be ongoing (Nkansah et al., 2009). Thus, to continue training for faculty and staff, there could be an ongoing monthly training series on the topics of antiracism and diversity during faculty/staff meetings or a standalone workshop series. Faculty will need continued training on how to improve culturally competent pedagogy (Hinton & Seo, 2013). Both faculty and staff can receive continued training in multicultural competence (Pope et al., 2019) and bias training (Russell, Brock, & Rudisill, 2019). During portions of the training, it can be helpful for BIPOC and White individuals to have separate breakout groups so that they can discuss the issues relevant to how they have personally been racialized and socialized (St. Clair & Kishimoto, 2010). For students to receive continued training, it will be helpful to incorporate some of the ideas mentioned earlier in the Curricula and Pedagogy sections of the current article within their day-to-day coursework.

In addition to faculty, staff, and students learning about antiracism, the institution's culture can instill a sense of embracing others’ differences. In American society, the White experience is dominantly viewed as the “normal” experience (Melaku & Beeman, 2020), and faculty, staff, and students are often expected to put their unique and diverse experiences aside in order to “fit in” with the White culture (Moore, 2007). An antiracist culture desires to learn about the cultures and experiences of others and listens nonjudgmentally with curiosity and openness. When BIPOC express feelings of being marginalized or oppressed, they are given a platform to be heard. This is counter to what happens in a White hegemonic environment, where BIPOC often feel that when they voice their concerns, they are silenced (Melaku & Beeman, 2020). For example, in some cases when a faculty member voices a concern about policies, they are thought by other colleagues and administration to be noncollegial or conflict ridden. In such cases, rather than the policies in question being investigated, the victims are blamed. This is problematic, as it often pushes BIPOC faculty out of academia (Stockdill & Danico, 2012), and it may presumably cause BIPOC to feel as though they must remain silent until promoted or tenured.

One way to create a culture where it is safe to speak up is to model and practice voicing concerns while also allowing there to be spaces and methods for doing so. For example, in faculty meetings, all faculty need to feel that it is appropriate for them to voice their concerns about potential inequalities in order to contribute to the meaningful dismantling of racist policies (Stockdill & Danico, 2012). Likewise, in a classroom setting, the faculty can ask students to also speak up. For those faculty, staff, and students who do not feel comfortable voicing their concerns publicly, there can be private ways to express concerns. For example, the program could have a system in place for students, faculty, and staff to submit their concerns to the diversity chair or committee, which includes the option of an anonymous submission. There should be accountability for the administration to follow up on such submissions in a way that creates fairness and equity. Another way to convey that voices want to be heard is for the university leadership to administer campus assessments that identify areas in which individuals feel there is marginalization and oppression (Pope et al., 2019). Furthermore, marginalized individuals could even be involved in the development of such campus assessments (Pope et al., 2019). Assessments of this sort could be conducted via anonymous surveys and focus being able to have a voice is necessary for the overall wellness of BIPOC, access to wellness in other capacities can occur as well. One example is to ensure the campus counseling center and/or other spaces that are supposed to provide care will not cause harm to students, staff, or faculty of marginalized identities who need those services. For example, the counseling center should have sufficient counselors of color on staff who are mindful of culture and intersectionality (Mosley & Bellamy, 2020). Additionally, there are benefits to having spaces such as regular meetings to share experiences with one another in order for individuals to provide support and mentorship. For example, faculty who have such spaces are more likely to be retained and promoted (Rockquemore & Laszloffy, 2008). BIPOC faculty, staff, and students might like to have these opportunities to connect with others experiencing similar racial issues.

One way for regular meetings to occur among one another is through the establishment of department diversity committees. Diversity committees that have clearly defined goals and objectives can help institutionalize diversity practices (Leon & Williams, 2016). It may be appropriate to have separate diversity committees for each group: faculty, staff, and students. A faculty diversity committee could address topics related to curriculum and pedagogical issues, whereas a student diversity committee (with a faculty advisor selected by the students) might address students’ concerns related to diversity issues within the graduate training program. Various activities that a diversity committee might conduct include providing continued education about topics of diversity, leading a book/journal club, establishing support groups for BIPOC, establishing a mentorship program for faculty/students, creating networking opportunities for underrepresented individuals, troubleshooting racial incidents, creating strategies to evaluate the effectiveness of antiracism actions, and arranging activities centered on activism such as protesting, writing letters, mass petitions, and calling elected officials. Faculty and student committees may even cosponsor some events, and staff could also be called upon to be involved in some efforts, depending on what is relevant to each population.

Faculty and Staff

Recruitment and Hiring

Policies can be established to improve the experience of faculty and staff in university settings. This can begin with recruiting and hiring more BIPOC to fill faculty and staff positions. In 2017, BIPOC made up only 17% of full-time professors and 28% of full-time assistant professors in higher education (National Center for Education Statistics, 2019). Diversification of faculty and staff in ABA programs is needed and should be done at a level that is visible and provides a meaningful representation (Pope et al., 2019). Hiring only one BIPOC faculty member is considered tokenism and should be avoided (McKinley & Brayboy, 2003).

Before beginning the recruitment process, it may be helpful to know the university’s initiatives for diversity. For example, funds or other resources may be available from the provost’s office or the diversity office that can be used for recruitment (Russell et al., 2019). One way to reach BIPOC during recruiting efforts is to increase community outreach efforts by linking the university with more community organizations (Jackson, O’Callaghan, & Leon, 2014). In the field of ABA, universities can reach out to the Black Applied Behavior Analysts, the Latino Association for Behavior Analysis, the Association for Behavior Analysis International’s (ABAI) special interest group (SIG) on culture and diversity, and diversity SIGs that are a part of state and local chapters of ABAI to let them know about available faculty and staff positions. Job advertisements can also be placed through the BACB’s email service, posted in ABAI’s career center, posted through the Association for Professional Behavior Analysts’ website, posted on the websites of state chapters of ABAI, posted on social media, and sent via Listservs. Another way to diversify the applicant pool includes asking faculty to identify individuals from underrepresented groups that they could personally encourage to apply (Russell et al., 2019). Additionally, aspects of the hiring announcement may encourage individuals from diverse backgrounds to apply, such as including a strong diversity statement, using inclusive language in the announcement, and mentioning inclusive benefits (e.g., related to childcare and parental leave; Russell et al., 2019).

Some universities’ human resources departments make efforts to diversify faculty and staff by providing candidates from underrepresented groups with resources and guidance, such as employment sessions that review employment opportunities, help with the online job application process, and information about local services such as career workshops that provide tips for writing an effective résumé (Jackson et al., 2014) and cover letter, as well as sharpening job interviewing skills. Human resources departments also train staff who provide such services to be welcoming, friendly, and personable to all applicants (Jackson et al., 2014). There may even be a dual-career program provided by the human resources department to assist applicants’ spouses with their job search (Jackson et al., 2014). When hiring faculty and staff, it is paramount that the hiring committee avoid bias. This can be done in various ways such as ensuring the hiring committee is trained about implicit bias prior to the candidate interview and evaluation process. Some universities’ human resources departments offer such training to hiring committees (Russell et al., 2019). Perhaps objective screening tools that do not use biased language could be developed for hiring committees to use for evaluating applicants. Furthermore, it may be helpful for the hiring committee to attend to the demographics of applicants who are suggested for progression from one phase of the hiring process to the next and to require a rationale for applicants who are not progressing (Russell et al., 2019). In order to identify whether applicants will support the program’s commitment to diversity, applicants can be asked to provide their own diversity statement in their application materials, and questions related to diversity can be included during interviews of candidates.

Retention

After faculty and staff are hired, many variables can be considered in their retention. For example, salaries for BIPOC are lower than for White individuals (Jackson et al., 2014; Jackson & O’Callaghan, 2009). Instead, salaries could be related to the position and the same for every person in that position regardless of race. In addition, new faculty should be provided with the faculty handbook and any other policies that exist in the department (Russell et al., 2019). The expectations with respect to teaching, scholarship, and service should be outlined during the candidate’s interview process and again at each annual evaluation (Russell et al., 2019). Pairing new faculty with a seasoned faculty mentor with similar academic or personal interests can help improve retention (Kosoko-Lasaki, Sonnino, & Voytko, 2006), and mentors can help orient new faculty to the university’s expectations and process for retention, tenure, and promotion (Vasquez et al., 2006). Recognition that student teaching evaluations can be influenced by biases, such as those relevant to the faculty’s attributes of diversity, the student’s perception of the importance of the course topic to their career plans, and comparison of the current course with previously taken courses, should also be ensured (Falkoff, 2018; Lilienfeld, 2016). Furthermore, faculty who choose to teach about antiracist topics, such as White privilege and White supremacy, will need to be supported by the administration if their teaching evaluation scores are lower due to tackling these challenging topics. Allowing faculty the opportunity to provide a narrative of their accomplishments and goals related to teaching, scholarship, and service with their annual evaluations may help negate implicit bias (Russell et al., 2019). It is also informative for faculty to be given clear written feedback about whether their performance is on track to receive future tenure and/or promotion (Russell et al., 2019).

It can be helpful for the retention of BIPOC to provide opportunities for obtaining mutual support, sharing experiences with one another, and engaging in social networking with diverse individuals (Turner, González, & Wood, 2008). In order to retain faculty who are committed to social justice, it is essential that manifestations of inequality are decoded in the university program (Stockdill & Danico, 2012). Furthermore, it should be noted that BIPOC faculty have a lot more stressors and responsibilities than White faculty, which can take a physical and emotional toll (McKinley & Brayboy, 2003). For example, in addition to having the same responsibilities as White faculty, such as teaching courses, publishing manuscripts, and providing service, BIPOC faculty are often additionally burdened with being expected to be the barometer for the guilt of White individuals, mentor BIPOC and White antiracist students, serve on a diversity committee, teach diversity courses, and train faculty on diversity. Unfortunately, these additional tasks and the costs associated with them tend to go unnoticed (McKinley & Brayboy, 2003).

BIPOC faculty should not be expected to take on this level of emotional labor. Yet BIPOC faculty who choose not to perform such expected activities may create a false image that they are not team players and are instead troublemakers (McKinley & Brayboy, 2003), and they may be viewed as “race traitors” by other BIPOC faculty and students (McKinley & Brayboy, 2003). In order to retain BIPOC faculty, it is important that these duties not be the burden of BIPOC faculty only (Mosley & Bellamy, 2020). These duties should be recognized in categories of service, and BIPOC should be able to avoid being involved in other committees or types of service if they are performing in these roles of advancing diversity in the university. If these duties cannot be recognized as activities that can count under service, then faculty who do these extra tasks should be compensated for them. Such duties can adversely impact the tenure and promotion of BIPOC faculty by taking up time they could be using to publish and engage in other types of service (Fogg, 2003), thus these activities should also potentially be given more weight during promotion and tenure evaluations.

Advancement

An unbiased faculty advancement process that occurs through the tenure and promotion review is important for the retention of BIPOC faculty. There are various strategies related to tenure and promotion that can help exemplify inclusive excellence. For one, the tenure and promotion process should be clearly outlined and communicated to faculty upon being hired. This may include providing information regarding timelines for submission, materials to include in the dossier, and the process of the review (Russell et al., 2019). BIPOC faculty up for review can be provided with support as they prepare their materials (Russell et al., 2019). Faculty who will be reviewing materials should be trained in advance on implicit bias and how it may affect their evaluation of their peers (Russell et al., 2019). They can also be reminded to be aware of service that may have affected a faculty’s scholarly activity, such as mentoring underrepresented students, serving on diversity committees, and so forth (Russell et al., 2019). Perhaps, more value can be placed on service that is in the area of diversity and antiracism (Mosley & Bellamy, 2020). Faculty and staff can be held accountable for the university’s mission of inclusive excellence by including within their evaluations ongoing measurement and goals outlining their involvement with institutional diversity (Nkansah et al., 2009).

White Allyship

During the development of an antiracist identity, it is crucial for faculty and staff to build relationships both to provide support and to receive critical feedback when mistakes, such as microaggressions, are made. BIPOC are most equipped to provide feedback about whether individuals’ behaviors are in line with those of an antiracist ally (Matias, 2013). White individuals should also seek the support of other White individuals when doing the work of antiracism, as they serve a significant role in one another’s development (Utt & Tochluk, 2020). White scholars who collaborate with BIPOC should ensure that their work is not overshadowing that of BIPOC authors and that they are acknowledging the contributions of BIPOC to the subject matter by citing them (Wagner, 2005). White faculty can also forgo some activities (e.g., manuscript preparation) for service related to diversity, such as starting an antiracism coalition in the university (Mosley & Bellamy, 2020).

White faculty can voice to administration and at faculty meetings their concerns about policies that create inequality (Stockdill & Danico, 2012). It can be easy for White individuals to choose to be complicit with policies that disproportionately impact BIPOC negatively whenever they want; however, BIPOC do not have this luxury. Therefore, it is crucial that White individuals continue their work on antiracism beyond the academy and remain grounded in the current issues that BIPOC face (Wagner, 2005). Likewise, White individuals will need to commit themselves to understanding how intersectionality (how one’s various identities of race, gender, and sexual orientation interact) plays a role in racism (see Crenshaw, 1990, for more on intersectionality).

Students

Negative experiences in higher education can have dire consequences for BIPOC students, which is reflected in the poor graduation rates of this population (Hinton & Seo, 2013). Factors that contribute to negative experiences include the university showing little support for BIPOC students, a mismatch between the learning-style preferences of African American students and teaching styles, the use of cultural codes to communicate information, racial stereotyping, and a tenuous racial climate (Rovai, Gallien Jr., & Wighting, 2005). Various policies that can be put into place in an attempt to elevate the experiences of BIPOC in university settings are outlined in the sections that follow.

Recruitment and Admissions

This can begin with recruitment efforts. Graduate programs in ABA need to increase the recruitment of BIPOC. Specifically, recruitment efforts can be put toward attracting international students, reaching out to ABA-based agencies (Wang et al., 2019), marketing in spaces that BIPOC occupy, creating scholarships for BIPOC, and so on. A graduate program that has a greater number of BIPOC students can lead to those students recruiting other BIPOC students, which also feeds into the development of more future BIPOC faculty (Maton, Kohout, Wicherski, Leary, & Vinokurov, 2006). Thus, this strategy can ultimately increase the recruitment and retention of both future BIPOC students and faculty (Maton et al., 2006).

Once students have been recruited and are in the application process, various policies can be put into place to ensure equity during the admissions process. For example, because the Graduate Record Examination (GRE) has been found to have little predictive validity (Morrison & Morrison, 1995), the requirement of applicants to have taken the GRE could be eliminated. Given that individuals who pay for a GRE test preparation course are promised by test preparation sites to score 200 points higher on the GRE than those who do not take a test preparation course, it seems plausible that the GRE does not identify intellectual strength, but instead identifies those who have the awareness and resources to take a test preparation course (Kendi, 2019). An alternative method for assessment during admissions could be to ask candidates to submit a portfolio or written assignment. Candidates could also be asked to write an essay during an in-person interview when given a writing prompt. Other strategies could also be put into place to help applicants, such as the university offering workshops to BIPOC to assist them with completing their applications. Such workshops could address details related to admission criteria (e.g., what types of letters of recommendation would be better to get, what the program is looking for in the statement of purpose, what to do if the applicant’s grades are not ideal), and help with securing financial aid (Russell, 2019).

Retention

After students are admitted, the concern becomes retention and graduation. In order to help retain BIPOC students, recommendations made earlier in this article, such as ensuring their voices are heard and giving them spaces and resources for wellness, are relevant. Additional ideas include having a Center for BIPOC Student Success (Abdullah, 2020) or a mentorship program (Stockdill & Danico, 2012) for BIPOC that gives them the tools they will need to be successful in the program (e.g., priming, tips for writing, study groups, access to senior students in the program, BIPOC student support groups). Such a center or program could also provide scholarships for BIPOC who demonstrate excellence in the areas of academics and social service (Abdullah, 2020).

Alumni

Even after students have graduated, a university program that truly values its BIPOC students will make efforts to cultivate a culture of togetherness by providing support for alumni through continued mentorship for professional development, social networking opportunities, and the sharing of information (Russell, 2019). Additionally, alumni may be interested in serving as mentors to some of the program’s current graduate students.

Conclusion

Racist policies continue to dominate in the academy, yet there are systemic transformations that can occur within this setting to dismantle racism and move toward equity for BIPOC. The current article sought to bring to light how behavior-analytic graduate training programs could be reimagined to accomplish these goals. There are many viable strategies that graduate training programs in behavior analysis can use to (a) organize the structure of the program and leadership; (b) infuse antiracist and multicultural ideals into curricula, pedagogy, and research; (c) recruit and retain more BIPOC faculty, staff, and students; and (d) train all faculty, staff, and students in cultural competence and humility.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding the information reported in this article.

Ethical approval

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal participants performed by any of the authors.

Funding

No funding has been provided for this research.

Informed consent

No informed consent was needed in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abdullah, M. (2020). Demands to make Black Lives Matter at Cal State LA and build a freedom campus. https://campaigns.organizefor.org/petitions/demands-to-make-black-lives-matter-at-cal-state-la-and-build-a-freedom-campus

- Beaulieu L, Addington J, Almeida D. Behavior analysts’ training and practices regarding cultural diversity: The case for culturally competent care. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(3):557–575. doi: 10.1007/s40617-018-00313-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behavior Analyst Certification Board. (2018). Professional and ethical compliance code for behavior analysts. https://www.bacb.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/BACB-Compliance-Code-english_190318.pdf

- Benuto, L. T., Casas, J., & O’Donohue, W. T. (2018). Training culturally competent psychologists: A systematic review of the training outcome literature. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 12(3), 125–134. 10.1037/tep0000190.

- Betancourt, J. R., Green, A. R., & Carrillo, J. E. (2002). Cultural competence in healthcare: Emerging frameworks and practical approaches. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/sites/default/files/documents/___media_files_publications_fund_report_2002_oct_cultural_competence_in_health_care__emerging_frameworks_and_practical_approaches_betancourt_culturalcompetence_576_pdf.pdf

- Brodhead MT, Durán L, Bloom SE. Cultural and linguistic diversity in recent verbal behavior research on individuals with disabilities: A review and implications for research and practice. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2014;30(1):75–86. doi: 10.1007/s40616-014-0009-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campinha-Bacote J. The process of cultural competence in the delivery of healthcare services: A model of care. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2002;13(3):181–184. doi: 10.1177/10459602013003003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campinha-Bacote, J. (2019). Cultural competemility: A paradigm shift in the cultural competence versus cultural humility debate—Part I. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 24(1). 10.3912/OJIN.Vol24No01PPT20.

- Conners B, Johnson A, Duarte J, Murriky R, Marks K. Future directions of training and fieldwork in diversity issues in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(4):767–776. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00349-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conners, B. M. (2020). An introduction to multiculturalism and diversity issues in the field of applied behavior analysis. In B. M. Conners & S. T. Capell (Eds.), Multiculturalism and diversity in applied behavior analysis: Bridging theory and application (pp. 1–3). Routledge. 10.4324/9780429263873-1.

- Council for Accreditation of Counseling and Related Educational Programs. (2015). The 2016 standards. https://www.cacrep.org/for-programs/2016-cacrep-standards/

- Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review. 1990;43(6):1241–2199. doi: 10.2307/1229039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dennison A, Lund EM, Brodhead MT, Mejia L, Armenta A, Leal J. Delivering home-supported applied behavior analysis therapies to culturally and linguistically diverse families. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2019;12(4):887–898. doi: 10.1007/s40617-019-00374-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diversity and Resiliency Institute of El Paso. (2020). Anti-racism training. https://www.driep.org/anti-racism-training.

- Falkoff, M. (2018, April). Why we must stop relying on student ratings of teaching. Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/why-we-must-stop-relying-on-student-ratings-of-teaching/

- Fisher-Borne, M., Cain, J. M., & Martin, S. L. (2015). From mastery to accountability: Cultural humility as an alternative to cultural competence. Social Work Education, 34(2), 165–181. 10.1080/02615479.2014.977244.

- Fogg, P. (2003, December). So many committees, so little time. Chronicle of Higher Education, 50(17), A14. http://archive.advance.uci.edu/media/So%20Many%20Committees,%20So%20Little%20Time.pdf

- Fong EH, Catagnus RM, Brodhead MT, Quigley S, Field S. Developing the cultural awareness skills of behavior analysts. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9(1):84–94. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0111-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fong, E. H., Ficklin, S., & Lee, H. Y. (2017). Increasing cultural understanding and diversity in applied behavior analysis. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice, 17(2), 103–113. 10.1037/bar0000076. [DOI]

- Fong EH, Tanaka S. Multicultural alliance of behavior analysis standards for cultural competence in behavior analysis. International Journal of Behavioral Consultation and Therapy. 2013;8(2):17–19. doi: 10.1037/h0100970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, M. A., Zelaya, D. G., & Madsen, J. W. (in press). Rethinking the course syllabus: Considerations for promoting equity, diversity and inclusion. Teaching of Psychology.

- Funchess, M. (2014, October). Implicit bias: How it affects us and how we push through [Video]. TED Conferences. https://tedxflourcity.com/?q=speaker/2014/melanie-funchess

- Georgetown University National Center for Cultural Competence. (n.d.). Self-assessments. https://nccc.georgetown.edu/assessments/

- Gershfeld Litvak, S., & Rue, H. (2020). Creating a culturally competent clinical practice. In B. M. Conners & S. T. Capell (Eds.), Multiculturalism and diversity in applied behavior analysis: Bridging theory and application (pp. 123–134). Abingdon: Routledge.

- Harper SR, Hurtado S. Nine themes in campus racial climates and implications for institutional transformation. New Directions for Student Services. 2007;120:7–24. doi: 10.1002/ss.254. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, D., & Seo, B. I. (2013). Culturally relevant pedagogy and its implications for retaining minority students in predominantly White institutions (PWIs). In D. M. Callejo Perez & J. Ode (Eds.), The stewardship of higher education: Re-imagining the role of education and wellness on community impact (pp. 133–148). Sense Publishers. 10.1007/978-94-6209-368-3_8

- Hook JN, Watkins CE., Jr Cultural humility: The cornerstone of positive contact with culturally different individuals and groups? American Psychologist. 2015;70(7):661–662. doi: 10.1037/a0038965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JFL, O’Callaghan EM. What do we know about glass ceiling effects? A taxonomy and critical review to inform higher education research. Research in Higher Education. 2009;50(5):460–482. doi: 10.1007/s11162-009-9128-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, J. F. L., O’Callaghan, E. M., & Leon, R. A. (2014). Measuring glass ceiling effects in higher education: Opportunities and challenges: New directions for institutional research. John Wiley & Sons.

- Jibaja-Rusth ML, Kingery P, Holcomb JD, Buckner WP, Pruitt BE. Development of a Multicultural Sensitivity Scale. Journal of Health Education. 1994;25(6):350–357. doi: 10.1080/10556699.1994.10603060. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kendi, I. X. (2019). How to be an antiracist. One World.

- Kezar AJ. Tools for a time and place: Phased leadership strategies to institutionalize a diversity agenda. Review of Higher Education. 2007;30(4):413–439. doi: 10.1353/rhe.2007.0025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kishimoto, K., & Mwangi, M. (2009) Critiquing the rhetoric of “safety” in feminist pedagogy: Women of color offering an account of ourselves. Feminist Teacher,19(2), 87–102. 10.1353/ftr.0.0044.

- Kosoko-Lasaki O, Sonnino RE, Voytko ML. Mentoring for women and underrepresented minority faculty and students: Experience at two institutions of higher education. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98(9):1449–1459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon RA, Williams DA. Contingencies for success: Examining diversity committees in higher education. Innovative Higher Education. 2016;41(5):395–410. doi: 10.1007/s10755-016-9357-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li A, Wallace L, Ehrhardt KE, Poling A. Reporting participant characteristics in intervention articles published in five behavior-analytic journals, 2013–2015. Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice. 2017;17(1):84–91. doi: 10.1037/bar0000071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lilienfeld, E. (2016, June). How student evaluations are skewed against women and minority professors. The Century Foundation. https://tcf.org/content/commentary/student-evaluations-skewed-women-minority-professors/?agreed=1

- Lundberg CA. Student involvement and institutional commitment to diversity as predictors of Native American student learning. Journal of College Student Development. 2007;48:405–416. doi: 10.1353/csd.2007.0039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyiscott, J. (2018, April). Why English class is silencing students of color [Video]. TED Conferences. https://www.ted.com/talks/jamila_lyiscott_why_english_class_is_silencing_students_of_color

- Matias CE. Check yo’self before you wreck yo’self and our kids: Counterstories from culturally responsive White teachers? . . . To culturally responsive White teachers! Interdisciplinary Journal of Teaching and Learning. 2013;3(2):68–81. [Google Scholar]

- Maton, K. I., Kohout, J. L., Wicherski, M., Leary, G. E., & Vinokurov, A. (2006). Minority students of color and the psychology graduate pipeline: Disquieting and encouraging trends, 1989–2003. American Psychologist, 61(2), 117–131. 10.1037/0003-066X.61.2.117. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McKinley B, Brayboy J. The implementation of diversity in predominantly White colleges and universities. Journal of Black Studies. 2003;34(1):72–86. doi: 10.1177/0021934703253679. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melaku, T. M., & Beeman, A. (2020, June 25). Academia isn’t a safe haven for conversations about race and racism. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2020/06/academia-isnt-a-safe-haven-for-conversations-about-race-and-racism