Abstract

We taught three children with autism how to respond to abduction lures presented by strangers. We then tested undesirable generalization of the safety response to matched instructions to leave by a familiar adult. Following training, all three participants engaged in the safety response across both strangers and familiar adults. Thus, we evaluated a set of procedures for establishing discriminated responding. Appropriate responding to instructions to leave by strangers versus familiar adults was achieved only after discrimination training. Discriminated responding occurred across a novel setting and maintained across 3 months; however, performance during stimulus generalization probes within community settings was variable.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40617-020-00541-9.

Keywords: Abduction, Behavioral skills training, In situ training, Multiple-exemplar training

The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children (2020) reports that attempted and successful abductions committed by strangers occurred more than 1,300 times in 2019. The consequences of these abductions can be dire, with children with an intellectual disability being particularly susceptible to abuse or exploitation by strangers (Wilson & Brewer, 1992). Unfortunately, research repeatedly shows that children of both typical and atypical development will readily leave with a stranger when lured (Gunby, Carr, & LeBlanc, 2010; Gunby & Rapp, 2014; Johnson et al., 2005). Leaving with a stranger when lured may be particularly problematic for children with autism for whom social deficits characteristic of the disorder, such as a lack of discrimination between strangers and familiar adults, may put them at greater risk for abduction by strangers (Gunby et al., 2010).

The dangers associated with abduction and the apparent willingness of children to leave with strangers have resulted in a growing body of research aimed at addressing these safety issues. One common method for teaching abduction prevention skills includes behavioral skills training (BST), which consists of instructions, modeling, and feedback (Carroll-Rowan & Miltenberger, 1994; Miltenberger & Olsen, 1996; Poche, Brouwer, & Swearingen, 1981). Unfortunately, it is often the case that children of atypical development who have demonstrated acquisition of a target response (e.g., gun safety) during BST have not performed well during generalization tests in novel settings (e.g., Himle, Miltenberger, Flessner, & Gatheridge, 2004), suggesting that participants may not engage in a correct safety response when they encounter real-life dangerous situations.

When BST alone is ineffective, in situ training may be sufficient to achieve generalization across novel settings (e.g., Himle et al., 2004). In situ training differs from typical BST in that feedback and praise are delivered during the naturalistic test probes. However, introducing in situ training into settings designated for generalization probes (e.g., a nearby playground) poses a problem insofar as it does not allow for generalization tests across untrained settings (i.e., first-trial performance). In other words, in this example, once feedback and praise have been delivered during probes at the playground, the playground can no longer be used to evaluate the spread of the effects of training to novel settings. This is important as true tests of generalization require that baselines measures be obtained in that setting prior to any training to be able to compare performance pre- and posttraining. To circumvent this issue while also allowing for a comparison across pre- and posttraining generalization probes, in situ training could be conducted in settings that are different from those designated for generalization probes. For example, rather than introducing in situ training within the playground, in situ training could take place in the waiting room of a doctor’s office or a public cafeteria. In this way, the benefits of in situ training can be maintained while both promoting and allowing for tests of generalization.

A real-life abduction attempt is likely to take place in untrained contexts, so it is important to optimize generalization strategies. One of the most applicable generalization strategies in this case is to train sufficient exemplars (Stokes & Baer, 1977). To train sufficient exemplars, behavior-analytic studies have extended previous research by including features that are more representative of statistics on common characteristics of abductions. Such characteristics include the type of lures presented and the type of locations used during test probes. For example, based on data from interviews with offenders (Elliott, Browne, & Kilcoyne, 1995), most of the behavior-analytic research on teaching abduction prevention skills has included at least four types of commonly reported lures: simple (e.g., “Let’s go for a walk.”), authority (e.g., “Your mom asked me to come get you.”), incentive (e.g., “I have some toys in my car.”), and assistance (e.g., “Can you help me bring this to my car?”). In addition, based on offenders’ self-reports of seeking out victims who are left alone in child-friendly areas such as schools and playgrounds (e.g., Boudreaux, Ary, Mandry, & Mccabe, 2000), recent studies have evaluated generalization across community settings such as schools, grocery stores, recreation centers, and neighborhood streets (Fisher, Burke, & Griffin, 2013; Gunby et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2005). Unfortunately, an important limitation of these studies is that responses to abduction lures were not always tested in settings in which direct training did not take place. In addition, despite statistics stating that 95% of perpetrators of nonfamilial abductions are male (Boudreaux et al., 2000; Hammer et al., 2002), most of the literature has used female confederates to act as strangers (e.g., Gunby et al., 2010; Gunby & Rapp, 2014; cf. Bergstrom, Najdowski, & Tarbox, 2014).

Programming for generalization is undoubtedly important. However, until recently, researchers have not addressed the potential for undesirable generalization of abduction prevention skills. Undesirable generalization is particularly relevant to children with autism, who tend to require direct and systematic teaching to establish proper antecedent control over target skills (e.g., Ingvarsson & Hollobaugh, 2010; Rodriguez, Levesque, Cohrs, & Niemeier, 2017; Shillingsburg, Powell, & Bowen, 2013). Recognizing that the same escape response that would be appropriate if presented with a lure from a civilian stranger would not be appropriate if approached by a police officer, Ledbetter-Cho et al. (2019) probed for undesirable generalization of a recently taught safety response with four children diagnosed with autism. Following mastery of the safety response with civilian strangers, undesirable generalization to police officers was observed with three participants and to a lesser extent for the fourth participant. To address undesirable generalization, Ledbetter-Cho et al. (2019) implemented a five-step discrimination training protocol (referred to as “officer BST”). The protocol consisted of having participants repeat that a police officer was a “safe stranger” and why it is important to leave with them when asked (Step 1); sort and label pictures of people in police uniforms versus civilian clothes into “safe” and “unsafe” strangers, first jointly with the therapist (Step 2), and then independently without prompts (Step 3); watch a video of an appropriate response to a police officer (Step 4), and finally, role-play using BST until mastery (Step 5). The effects of their discrimination training, however, were difficult to interpret due to the need for multiple exposures to discrimination training, variable responding post-discrimination training, the lack of repeated consecutive demonstrations of discriminated responding (mastery) despite previously variable responding, or some combination of these variables. Further, discriminated responding did not maintain at 4 or 10 weeks for two of the three participants for whom maintenance was assessed. Notably, one of the four participants demonstrated discriminated responding across consecutive sessions after only one exposure to discrimination training and maintained discriminated responding after 16 weeks.

One form of undesirable generalization that has not yet been addressed in the literature is the potential for undesirable generalization of abduction prevention skills to familiar adults. This is problematic because an escape response when approached by a familiar adult may further exacerbate social skill deficits that are characteristic of autism. Further, it is possible that, over time, appetitive or neutral consequences associated with leaving with a familiar adult may negatively affect the probability of a child emitting their previously learned abduction prevention response when approached by a stranger. In other words, the probability of emitting an appropriate abduction response in the presence of a stranger may begin to degrade if differential responding has not come under the control of strangers versus familiar adults (similar to the effects of a mixed vs. multiple schedule of reinforcement). That is, children are likely to contact reinforcement for leaving with an adult in general if discriminated control of the conditions under which one should and should not leave with an adult has not been established.

Finally, an important consideration when conducting abduction prevention research is the potential negative side effects of training and test probes (Miltenberger & Olsen, 1996). Beck and Miltenberger (2009) found that following their training package, which included in situ training, 50% of the participants’ caregivers reported their child was more scared, cautious, and upset. Moreover, one participant reported having a nightmare regarding an abduction. Other studies have found similar side effects (Carroll-Rowan & Miltenberger, 1994; Gunby & Rapp, 2014; Johnson et al., 2005), highlighting the importance of monitoring potential negative emotional responding during and following training. Toward this end, Johnson et al. (2005) developed a 6-item side effects questionnaire to evaluate changes in a child’s attitude toward strangers and so forth following training, as well as caregivers’ satisfaction with training. These subjective measures might be enhanced by corroborating them with direct measures of the child’s affect when approached by strangers versus familiar adults.

The purpose of our study was twofold. First, because undesirable generalization to familiar adults may occur, particularly with children with autism, we sought to extend the abduction prevention literature by testing the effects of training on responses to matched instructions to leave with strangers versus familiar adults. Second, when undesirable generalization was observed, we sought to evaluate a set of procedures for establishing discriminated responding (cf. Ledbetter-Cho et al., 2019); the sequence of skills was generally designed to gather preliminary data on the effects of less resource-intensive alternatives to training that did not require recruiting multiple confederates. In the process of meeting these objectives, we incorporated several procedural features designed to address limitations of some of the previous research. These included (a) conducting additional trainings (multiple-exemplar training) in settings different from test probes to allow for tests of generalization across the same settings that were evaluated during baseline, (b) including treatment extension test probes within various locations in the community, (c) increasing the ratio of male to female strangers during training and generalization probes to more closely approximate statistics on abductors, and (d) including direct measures of affect during lures to corroborate subjective measures of potential negative side effects of abduction prevention training.

Method

Participants and Settings

Three boys diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder participated. Wilbur (4 years old), Calvin (4 years old), and Theodore (5 years old) each received intensive behavioral intervention services at an early intervention program within a university-based clinic for 10, 6, and 25 hr a week, respectively. On the Verbal Behavior Milestones Assessment and Placement Program (Sundberg, 2008), Calvin and Theodore were primarily Level 2 learners (developmental skill level comparable to a typically developing child aged 18–30 months), and Wilbur was a Level 3 learner (developmental skill level comparable to a typically developing child aged 30–48 months). All participants used short sentences to mand and tact (e.g., could emit five- to seven-word utterances), engaged in reciprocal conversation, followed three-step instructions (similar in length to the target skill), expressively identified at least 20 actions, and did not engage in interfering behavior such as elopement or stereotypy. Participants also engaged in prerequisite skills related to our training such as attending to video models and imitating vocal and motor actions presented in vivo or via video model. Participants were not excluded based on the absence of these prerequisite skills or performance on preassessments (described next); however, we would have likely taught prerequisite skills prior to including children in this study. Despite these relatively substantial repertoires, their caregivers reported concerns regarding their child’s deficits in safety skills. Indeed, the impetus for this study was based on parental concern given recent local reports of an abduction attempt; at the same time parents were hesitant to teach abduction prevention skills given concerns that their child would run away from all adults, undermining the progress made thus far with social skills. Participants had no previous training on stranger safety skills prior to the study.

Sessions took place across various settings within the clinic and surrounding community. Test probes were conducted on the clinic’s indoor playground. BST and discrimination training (Phases 4–6) were conducted in the participants’ common classroom area, which was equipped with tables, chairs, and a variety of toys; Phases 1–3 of discrimination training were conducted at a table in the participants’ typical early intervention instruction area that was partitioned off from the common classroom area. In situ multiple-exemplar training was conducted across four locations: the play area of a second classroom, a playroom, a waiting area, and a lobby check-in area. Generalization probes were conducted on the clinic’s outdoor playground. Community probes were conducted in commercial stores and included a grocery store, Ace Hardware, Target, Walgreens, and Walmart. Community probe locations were chosen based on geographical convenience, as well as the fact that they were places that the families frequented. All settings included at least one familiar adult to whom the participant was supposed to report following a lure from a stranger (hereafter referred to as the reporting adult).

Dependent Variables and Data Collection

As our primary dependent variables, we measured participants’ responding to lures from both (a) strangers and (b) familiar adults. The target response to lures from strangers was derived from previous research on abduction prevention (e.g., Gunby et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2005). Specifically, the experimenter (i.e., the first author) taught each participant a three-step safety response for when a stranger presented a lure: (a) say “no,” (b) run from the area, and (c) report the event to a familiar adult (e.g., the reporting adult). In contrast, the experimenter taught participants a two-step response for when a familiar adult presented a lure: (a) say “OK” and (b) walk with the familiar adult. Observers used the following 5-point coding system to score responses to lures: a 0 was scored if the participant took at least three steps with the confederate; a 1 was scored if the participant did not take at least three steps with the confederate but failed to say “no,” leave the area (i.e., move at least three steps in a direction away from the confederate), or tell a familiar adult; a 2 was scored if the participant said “no” but did not leave the area or tell a familiar adult; a 3 was scored if the participant said “no” and left the area but did not tell a familiar adult; and a 4 was scored if the participant said “no,” left the area, and told a familiar adult. Thus, the target score for the response to lures from strangers was 4, and the target score for the response to lures from familiar adults was 0.

As a secondary measure of potential indirect adverse effects of training, we also collected data on the participants’ affect during the presentation of the lure during sessions in which both observers had an unobstructed view of participants’ faces, which was greater than 90% of sessions. Negative affect was scored if the participant had a scared expression (e.g., eyebrows raised and pulled together with lips horizontally stretched backward or defensive posture with head slightly ticked behind shoulder), began crying, or began trembling at any point during the vocal presentation of the lure. Crying or trembling never occurred in our study. Positive affect was scored if the participant smiled, laughed, or moved toward the confederate at any point during the vocal presentation of the lure. Neutral affect was scored if the participant’s responding did not meet the aforementioned definitions of negative or positive affect. Responses to lures and measures of affect were collected during test, generalization, maintenance, and community probes.

In addition, we collected the percentage of correct responding during BST, in situ multiple-exemplar training, and discrimination training. Target responses during BST included intraverbal responses, expressive identification during videos, and responses to lures during rehearsals (see BST training procedures for the definition of a correct response across BST phases). During in situ multiple-exemplar training, we collected data during rehearsals using the 5-point scale described previously. During discrimination training, target responses included sorting strangers versus familiar adults (Phase 1), expressive identification of the category of strangers versus familiar adults (Phase 2), intraverbal tacts (i.e., describing what to do when approached by the person in the picture; Phase 3), and correct responding during rehearsals according to the 5-point scale described previously (Phases 4–6; see Discrimination Training for the definition of a correct response across discrimination training phases).

All data were collected in vivo by the first author, third author, or both using paper and pencil. Data collectors were present during test probes but hidden from the participants’ view.

Interobserver Agreement

Two trained observers independently (and surreptitiously) scored each participant’s performance during 54% of test probes, 89% of generalization probes, 56% of maintenance probes, and 100% of community probes. One of the observers served as the reporting adult to whom the participant was supposed to report during stranger trials and was therefore visible to the participant. For trials during which the vantage point was blocked or the participant turned away from the second observer, interobserver agreement was not collected. For each test, generalization, maintenance, and community probe, scores were compared and an exact match of scores constituted an agreement. Interobserver agreement was calculated by dividing the number of agreements by the total number of probes and multiplying the quotient by 100. Mean interobserver agreement across participants for participants’ responses to lures was 100% during test, generalization, maintenance, and community probes. Mean interobserver agreement across participants for participants’ affect during lures was 90% (range 0%–100%) during test probes and 100% during generalization, maintenance, and community probes.

A second observer also collected data on 100% of BST sessions, 88% of in situ multiple-exemplar training sessions, and 100% of discrimination training sessions. An agreement was defined as both observers scoring the same response (i.e., correct or incorrect) for a trial. Interobserver agreement was calculated by dividing the number of trials with agreements by the total number of trials in the session, taking the mean across sessions, and multiplying the quotient by 100. Mean interobserver agreement across participants was 100% for BST, in situ multiple-exemplar training, and discrimination training.

Side Effects Questionnaire

Johnson et al. (2005) developed a 6-item questionnaire to evaluate parents’ opinions of the potential indirect effects of training (e.g., fear of strangers or being left alone) and parents’ satisfaction with the outcomes of training (see Supplemental Material 1). We asked parents to complete this same questionnaire following the termination of the study. In addition, as a baseline measure of parents’ opinions of their child’s behavior toward strangers or being left alone, we asked parents to answer a modified version of the first three items of the 6-item questionnaire prior to the start of the study (see Supplemental Material 2).

Design and Procedure

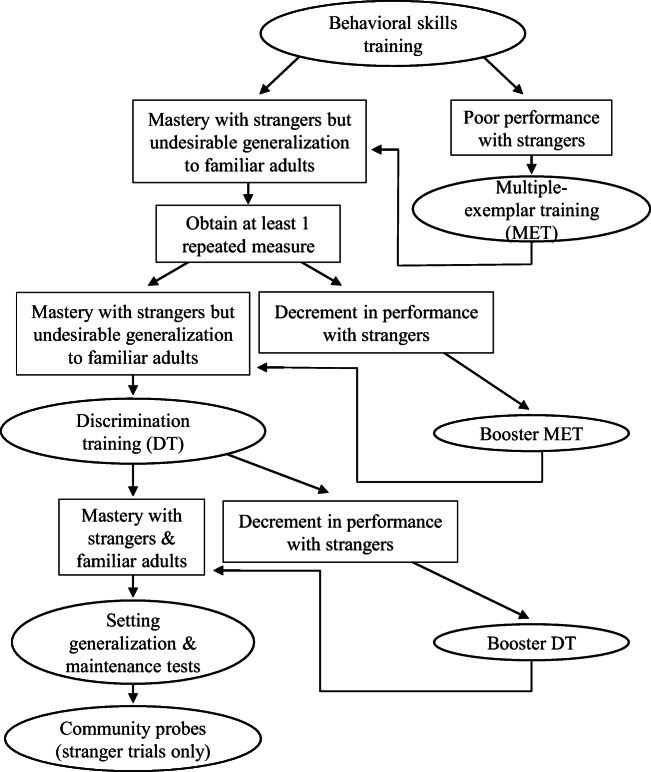

We used a concurrent multiple-probe across-participants design to evaluate the effects of BST, in situ multiple-exemplar training, and discrimination training. A flowchart outlining the conditions under which each training phase was conducted is depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart outlining each phase (ovals) and the patterns of performance that led to them (rectangles)

Confederates

We recruited many staff from our clinic and other clinics in other locations within our building, as well as three individuals not associated with the university, to serve as confederates (18 males and 16 females). The role of the confederate was to present lures during probes and applicable training sessions (described in more detail in what follows). Confederates who wore scrubs in line with a clinic-wide dress-code policy were asked to change into street clothes and remove all materials that identified them as staff members (e.g., badges, walkie-talkies) before the start of a probe or rehearsal (as part of BST, multiple-exemplar training, or discrimination training sessions). Confederates were grouped into one of two categories: individuals who were unfamiliar to the participant (i.e., strangers) and individuals who were familiar to the participant (i.e., familiar adults). The categories to which a confederate was assigned were based on the amount and frequency of previous contact the confederate had with the participant and confirmed via preassessments (described in what follows). For example, for individuals included in the familiar adults category, we identified individuals with whom the participant interacted regularly (e.g., therapist who worked with the child or a clinic supervisor) and with whom the participant had been left alone (or with whom it would be appropriate to leave the participant). Confederate strangers served as confederates up to two times per participant (M = 1.2), with two, three, and three confederates serving as strangers twice across Wilbur, Calvin, and Theodore, respectively. Confederate familiar adults served as confederates up to five times per participant (M = 2.4). We aimed to use at least 75% males during the probes to mirror the relative number of male abductors in the community (Boudreaux, Lord, & Etter, 1999).

Preassessments

We conducted a series of three preassessments to identify which confederates would serve as strangers versus familiar adults. During the sorting task, the experimenter presented the participant with 26 pictures of adults, half of whom were presumed to be strangers based on the experimenter’s knowledge of the participant’s previous contact with that person around the clinic. Pictures depicted individuals from the shoulders up, and features such as the color and type of clothing and hairstyle varied unsystematically across strangers and familiar adults. The experimenter presented a stock photo of a stranger and a photo of herself and labeled each pile as “stranger” or “familiar adult” accordingly. The experimenter then handed the pile of pictures to the participant and said, “Sort.” Praise was provided for correct in-session behavior (e.g., “Good job sitting in your chair.”). No differential consequences were provided for responding during the task. As part of a second and third preassessment, experimenters presented each picture and asked, “Is this person a stranger or a familiar person?” and “What is this person’s name?” respectively. No differential consequences were provided for correct or incorrect responding.

As a conservative means of informing roles, confederates with correspondence across all three preassessments were eligible to be used as strangers or familiar adults during test probes, generalization probes, maintenance probes, multiple-exemplar training, and discrimination training rehearsals. For strangers, we considered a response of “I don’t know” or something equivalent when the participant was asked the person’s name as a measure indicating that they were, indeed, unfamiliar to the participant.

Test Probes

Test probes were conducted both prior to and following BST, in situ multiple-exemplar training, and discrimination training. During test probes, a confederate approached the participant, presented one of four types of lures, and waited 10 s. The types of lures were based on previous research (e.g., Gunby & Rapp, 2014; Ledbetter-Cho et al., 2016; Poche et al., 1981) and included simple (e.g., “Do you want to go for a walk with me?”), authority (e.g., “Miss [child’s clinical therapist’s name] told me to come get you. Let’s go.”), assistance (e.g., “Can you help me bring these things to my car?”), and incentive (e.g., “Do you want to come play with some toys I have in my car?”) lures. Based on a parent’s request, Wilbur’s incentive lure during a community probe included a reference to his highly preferred item (i.e., cars). The type of lure presented was randomized in blocks of four across both confederate strangers and familiar adults. The order of stranger versus familiar adult probes was randomized. During test probes, no feedback or differential consequences were provided following responding. However, if the participant reported the abduction attempt, the familiar adult thanked the participant (i.e., “OK, thanks for telling me.”), regardless of whether it was a stranger or familiar adult probe. If the participant began to walk with the confederate, the confederate walked with the participant for 10 steps and then made an excuse to leave the child (e.g., “Never mind, we can go for a walk later.”).

To ensure that the therapist leaving the child did not serve as a discriminative stimulus for an abduction attempt, therapists were asked to regularly bring the participant to the indoor or outdoor playground and leave them for a short period during the participant’s regularly scheduled early intervention appointments. Specifically, the therapist provided an excuse to leave the participant (e.g., “I am going to get a drink of water.”), walked away from the participant, and covertly monitored the participant for 20–30 s from a nearby area out of the participant’s view. Other individuals, including the reporting adult, were sometimes present (albeit occupied at a distance) in the playground. During this time, the participant was not approached by a stranger or familiar adult, and no data were collected on participants’ responding.

The first posttraining test probe was conducted within 1 day of completing training across all trainings and participants, except for Calvin’s first post-discrimination training test probe, which was conducted 10 days following training. The time between test probes within any given phase was typically between 1 and 4 days, except when additional measures were obtained prior to moving (or planning to move) to discrimination training, in accordance with the concurrent multiple-probe design.

BST

Like previous research on teaching abduction prevention skills, we began with a BST program that was aimed at teaching children what to do when lured by a stranger. Also, like previous research, our BST program did not cover content related to being approached by a familiar adult. We did not cover this content in order to assess the effects of typical abduction prevention BST content (that includes strangers only) on undesirable generalization to familiar adults.

During the instruction portion of training, the experimenter (a) told the participant what to do if a stranger approached and provided a lure and (b) reviewed each of the four types of lures included in the current study. The experimenter then asked, “What do you do if a stranger walks up to you and tries to get you to leave?” A correct answer was scored if the participant said, “Say ‘no,’ run away, and tell a friend.” Contingent on a correct answer, praise was provided. If the participant did not respond within 5 s or provided an incorrect response, the experimenter provided a vocal model. The experimenter then re-presented the question until the participant correctly responded without a prompt.

During the modeling portion of training, we presented five video models for each of the four lures (i.e., 20 videos). Each of the safety responses (0–4) was modeled in each of the videos (e.g., saying “no,” leaving the area, but not reporting to a familiar adult), resulting in one exemplar and four nonexemplars of what to do when lured by a stranger. The order of presentation was randomized across participants. Each video depicted the experimenter acting as a child (i.e., playing on the floor with toys) and the third author acting as the reporting adult. A male who was unknown to the participants acted as the stranger. Participants were informed of the actors’ roles prior to starting the video. During the video, the experimenter played with a toy in a secluded play area while the reporting adult acted occupied in the background. The stranger entered the play area and provided one of the four lures previously described, and the experimenter, who was acting as a child in the video, engaged in one of the five safety responses corresponding with a score of 0, 1, 2, 3, or 4 on the 5-point scale. After viewing a video, the experimenter asked, “Did she say ‘no,’ run away, and tell a friend?” Contingent on a correct answer within 5 s (i.e., “yes” or “no”), the experimenter provided descriptive praise. Contingent on an incorrect answer, the experimenter prompted the correct answer and then re-presented the question until the participant correctly answered without a prompt. After the participant answered independently to all five videos, the experimenter initiated the modeling portion of training for the next lure. After the participant answered independently for all four lures, we initiated the rehearsal and feedback portion of BST.

During the rehearsal and feedback portion, the participant was told that the experimenter was going to act as a stranger. The experimenter then left the classroom area, leaving the participant and the reporting adult in the room (as in test probes). The experimenter then entered the room, presented a lure, and waited 10 s for a response. Contingent on a safety response of 4 (i.e., saying “no,” running away, and telling a familiar adult), the experimenter provided descriptive praise and ended the session. Contingent on an incorrect response (i.e., a safety response of 0–3), the reporting adult prompted the correct response by providing a vocal model and physical guidance. The experimenter then re-presented the lure until the participant correctly responded without a prompt.

This progression through instructions, video modeling, and rehearsal was repeated until the participant achieved independent responding during the first trial of the rehearsal portion (i.e., until re-presentation of trials was not needed). This process was repeated for all four lures (i.e., five videos per lure). Each session (consisting of one lure each) lasted approximately 10–20 min. BST was completed within 1–2 days across all participants.

In Situ Multiple-Exemplar Training

We implemented in situ multiple-exemplar training for two of the three participants for whom BST was insufficient. The procedures were identical to the test probes with the following exceptions. First, in situ multiple-exemplar training sessions were conducted in one of four novel locations. Second, sessions were conducted with strangers only. Third, sessions were conducted until the mastery criterion was met with female strangers before introducing male strangers. This latter modification was done for convenience purposes based on the relative availability of females versus males. Finally, differential consequences were provided for correct and incorrect responding. Specifically, contingent on a correct response, both the experimenter and reporting adult provided high-quality descriptive praise. Contingent on an incorrect response, the experimenter or reporting adult prompted the correct response by providing a vocal model and physical guidance. Following an incorrect response, the area was reset (i.e., the confederate stranger left, and the participant’s therapist returned) and the trial was re-presented. Trials were re-presented until the participant responded correctly to the stranger’s lure without prompting. The mastery criterion included independent correct responding on the first opportunity across two consecutive locations with two consecutive female strangers and then again across two consecutive locations with two consecutive male strangers. We used the same scoring system for in situ multiple-exemplar training and test probes. Contingent on a score of less than 4 during post-in situ multiple-exemplar training test probes with strangers, in situ multiple-exemplar training was reinitiated and continued until the mastery criterion was met again. This only occurred once for Theodore. In situ multiple-exemplar training (including booster training for Theodore) was completed within 6–10 days.

Discrimination Training

Undesirable generalization of the stranger response was observed during familiar adult probes, so we initiated discrimination training. Discrimination training consisted of six phases: sorting by category (Phase 1), expressive identification of category (Phase 2), intraverbal tact of action (Phase 3), rehearsal with pictures (Phase 4), rehearsal with female confederates (Phase 5), and rehearsal with male confederates (Phase 6). Phases 1, 2, and 3 consisted of tabletop instruction, and Phases 4, 5, and 6 consisted of rehearsal and feedback. Whereas the preassessment stimuli included pictures of staff to determine which staff would participate as stranger versus familiar adult confederates, in Phases 1–4 of discrimination training, the stranger stimuli included the authors’ friends and family who lived in different states, and the familiar adult stimuli included the participants’ adult family members with whom their parents confirmed it would be appropriate for them to leave. Prior to the start of discrimination training, the experimenter described what the participant should do when presented with a lure from a stranger versus a familiar adult. During Phase 1, the experimenter placed the written words “stranger” and “familiar” on the table while vocally labeling them, shuffled the 24 pictures of strangers and familiar adults, handed the pile of pictures to the participant, and said, “Sort.” During Phases 2 and 3, the experimenter held up each of the 24 pictures, one at a time, and asked, “Is this person a stranger or a familiar person?” (Phase 2) or “What do you say and do if this person walks up to you?” (Phase 3). A correct response for Phases 1 and 2 was defined as the proper sorting or labeling of the category for each picture (i.e., 24 trials). A correct intraverbal tact response for Phase 3 was “Say ‘no,’ run away, and tell a friend” for stranger trials and “Say ‘OK’ and walk with them” for familiar adult trials (also 24 trials). For Phases 1–3, contingent on a correct response, the experimenter provided praise. Contingent on an incorrect response or no response within 5 s of the discriminative stimulus, the experimenter provided a model (Phase 1) or vocal prompt (Phases 2 and 3) and then re-presented the trial until the participant responded correctly to the discriminative stimulus without prompting. The criterion for moving from one phase to the next was one session at 100% correct responding or two consecutive sessions above 91% correct responding.

Phases 4, 5, and 6 were conducted in the play area of the participants’ typical early intervention classroom. Like the rehearsal portion of BST, the experimenter left the room, which contained at least one adult (i.e., the reporting adult) who was in the participant’s view but appeared occupied. For Phase 4, the 24 pictures were divided into three sets; each set consisted of four strangers and four familiar adults for a total of eight trials per session. We divided the pictures into sets to be able to test for generalization across sets. During each trial, the experimenter entered the classroom with one of the pictures in front of her face and presented a lure. Contingent on a correct response, the experimenter and reporting adult provided praise. Contingent on an incorrect response or no response within 10 s of the lure, the reporting adult approached the child, provided a vocal prompt, and then physically guided the correct response. The criterion for moving from one phase to the next was 100% correct responding for one set.

Phases 5 and 6 were identical to Phase 4 except that a confederate stranger or familiar adult entered the room and presented the lure. Phase 5 included confederate females, and Phase 6 included confederate males. Each session consisted of one stranger trial and one familiar adult trial. For two participants (Calvin and Theodore), a differential observing response (DOR) was added to Phase 5 following two consecutive sessions of 0% correct responding. For the DOR, the confederate entered the room and presented the lure. The reporting adult stood next to the participant and immediately asked the participant (while pointing to the confederate), “Is (s)he a stranger or familiar person?” If the participant incorrectly labeled the confederate, the reporting adult vocally prompted the correct DOR. The confederate then re-presented the lure contingent on a correct DOR. Following two consecutive sessions with 100% correct DORs, as well as 100% correct responding following the lure, we removed the DOR. Once the DOR was removed, the criterion for moving from Phase 5 to Phase 6 or Phase 6 to post-discrimination training test probes was two consecutive sessions with 100% correct responding. If the participant did not score a 4 during stranger test or generalization probes and a 0 during familiar adult test or generalization probes, discrimination training was reinitiated using the same mastery criteria. This occurred once for Calvin. Discrimination training sessions (including booster training for Calvin) were conducted multiple times per week, with the first three phases being completed within 1 day. The total duration of discrimination training ranged from 3 weeks to 5 months across participants.

Generalization (Setting) and Maintenance Probes

Following mastery levels during test probes, we conducted a generalization probe in a different setting (i.e., the clinic’s outdoor playground). Despite efforts to minimize the time between probes, generalization probes were conducted within 3 (Wilbur), 6 and 17 (Calvin), and 8 (Theodore) days of the previous test probe. Following one session at mastery within the generalization setting, we conducted maintenance probes at 2 weeks, 1 month, and 3 months. Maintenance probes were conducted in the same setting as the test probes (i.e., the indoor playground). Procedures for generalization and maintenance probes were identical to those of test probes.

Community Probes

Following maintenance probes, we conducted community probes (e.g., Target, Ace Hardware) but with strangers only. The parent served as the reporting adult for all community probes. During the community probe, the experimenter communicated with the parent via text to identify their location so that the experimenter could remain inconspicuous and to prompt the parent when to provide an excuse to briefly leave their child alone. The parent then told their child where they would be (e.g., “I will be right back. I am going to go around the corner for just a second.”). Once the parent was out of the participant’s view, the confederate approached the participant. Following a correct response, the experimenter made herself visible and provided high-quality praise. Following an incorrect response, the experimenter approached, provided a vocal model, and physically guided the correct response. Following a prompted correct response, the participant was debriefed to mitigate any potential negative emotional side effects (e.g., “Good job saying ‘no’ and running away and telling Mommy. We were just practicing! This is my friend, [stranger’s name].”).

Results

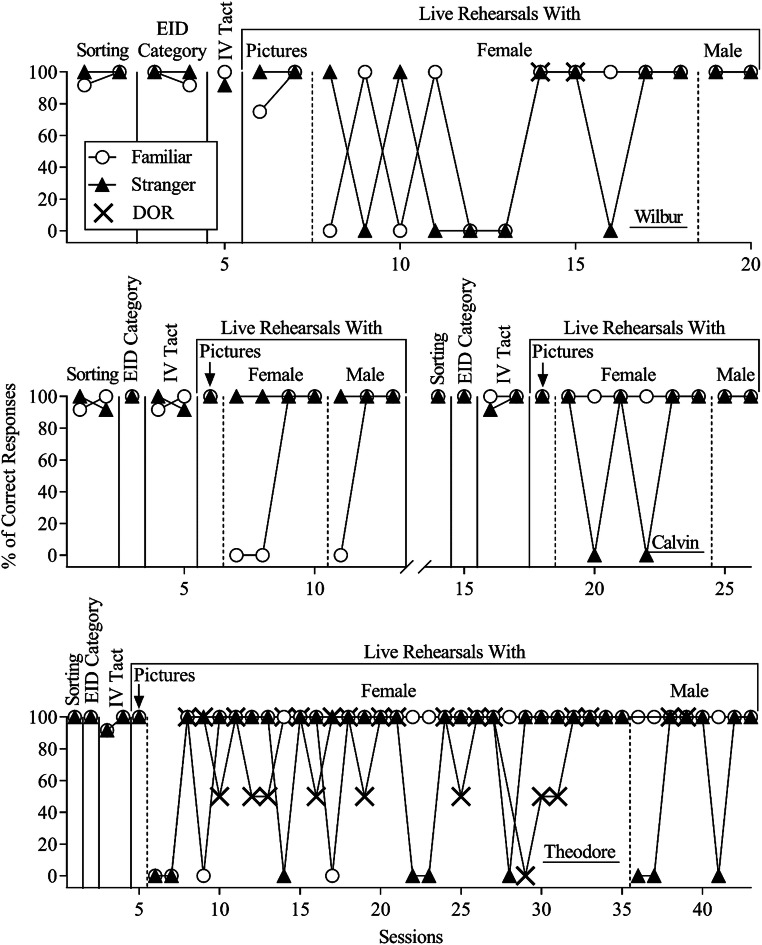

Figure 2 illustrates participants’ responses to lures during test, generalization, maintenance, and community probes. During baseline, participants’ safety scores were 0 (went with confederate) across both strangers and familiar adults, with the exception of a stranger generalization probe for Wilbur in which he scored a 1 (did not go with the confederate but failed to say “no,” run away, or report to an adult).

Fig. 2.

Safety rating score for Wilbur, Calvin, and Theodore. Note. The target safety score toward strangers (depicted by the triangles) was 4, and the target safety score toward familiar adults (depicted by the circles) was 0. Gray data points indicate the trial was conducted in a novel location. Maintenance probes were conducted at 2 weeks, 1 month, and 3 months. BST = behavioral skills training; DT = discrimination training; MET = in situ multiple-exemplar training; Gen = generalization

Only one of the three participants’ (i.e., Wilbur) responses to strangers increased to the desired score of 4 following BST. Because BST alone did not increase appropriate responding to strangers for Calvin and Theodore, we implemented in situ multiple-exemplar training for these participants. Posttraining measures showed that in situ multiple-exemplar training resulted in desirable performance during stranger test probes. For Theodore, the safety score decreased to 2 after an unplanned 9-week absence. Thus, we conducted a booster in situ multiple-exemplar training session, after which the safety score increased to 4 across three consecutive stranger and familiar adult test probes. Anytime there was an effect of BST (Wilbur) or in situ multiple-exemplar training (Calvin and Theodore) during stranger probes, undesirable generalization of the lure response also occurred across familiar adults. Thus, we moved to discrimination training, after which we observed immediate discriminated responding across strangers and familiar adults with perfect scores of 4 and 0, respectively, in at least the first session post-discrimination training for all participants.

Next, we conducted generalization probes. Discriminated responding generalized for all participants except Calvin, who left with the confederate during both stranger and familiar adult generalization probes (i.e., score of 0). However, after booster discrimination training, Calvin engaged in discriminated responding across both test and generalization probes. All three participants maintained perfect discriminated responding across 2-week, 1-month, and 3-month maintenance probes. Patterns of responding varied across participants for community probes. Wilbur initially scored a 2, followed by two consecutive probes with a score of 4. Calvin initially attempted to go with the stranger during his first community probe (score of 0) but then scored a 4 during the next community probe. During a third community probe in the front yard of his home, a neighbor interrupted the probe, believing the abduction to be real (data are not displayed due to the lack of an opportunity to complete the target response). Following this probe at home, Calvin’s mother decided to terminate further community probes. Theodore’s first community probe score was a 4 but then decreased to a score of 1 for three probes. We were unable to conduct additional community probes due to scheduling difficulties. We did not observe systematic differences in responding across the types of lures for any of our participants across phases.

Affect

We also collected data on affect. Calvin and Theodore did not display negative affect during any pre- or postteaching test probes. Wilbur displayed negative affect during two postteaching test probes (i.e., two of the three community probes) compared to zero times prior to any teaching.

BST and In Situ Multiple-Exemplar Training

During BST, we collected data on the number of re-presentations prior to meeting criteria for independent responding across each type of lure for each component (i.e., instructions, modeling, and rehearsal; data are available upon request). For Wilbur, only one re-presentation was needed throughout BST. For Calvin, 21 re-presentations were needed across all three components, and Theodore needed 6 re-presentations to gain independent responding across all three components.

For in situ multiple-exemplar training, we also collected the number of re-presentations needed to gain independent responding (data are available upon request). Wilbur did not require any re-presentations, whereas Calvin required two re-presentations. During the first phase of in situ multiple-exemplar training, Theodore required one re-presentation; he required two re-presentations during the second phase.

Discrimination Training

Responding during discrimination training is depicted in Fig. 3. All three participants quickly progressed through Phases 1–4, meeting the mastery criterion within one or two sessions. During Phase 5 (rehearsals with females), Calvin met the mastery criterion within four sessions. By contrast, Wilbur and Theodore did not meet the mastery criterion until after a brief phase in which a DOR was prompted. During Phase 6, all participants met the mastery criterion within two to four sessions, without the inclusion of a DOR. Calvin’s progression through his second round of discrimination training was similar to his first round, except that a few more sessions were required before Calvin met the mastery criterion during rehearsals with females.

Fig. 3.

Percentage of correct responding across various phases of discrimination training for Wilbur, Calvin, and Theodore. Note. Triangles and circles represent responding toward strangers and familiar adults, respectively. Break lines on the x-axis indicate where test probes were conducted prior to booster discrimination training. Differential observing response (DOR) data are only depicted for those sessions in which a DOR was used. EID = expressive identification; IV = intraverbal

Side Effects Questionnaire

All three participants’ caregivers completed the side effects questionnaire prior to training (see Table 1). However, only Wilbur’s and Calvin’s caregivers completed the questionnaire posttraining. Prior to the study, caregivers for two participants reported that they were “concerned,” and one caregiver reported that she was “extremely concerned” that their child would be abducted or presented with a lure from a stranger in the natural environment. Caregiver ratings prior to training suggested that participants did not have reservations across any of the three measures (i.e., leaving parents, going outside or being alone, or around issues of strangers or personal safety). The posttraining questionnaire asked caregivers to rate their child’s behavior relative to their behavior prior to the start of the study. Wilbur’s caregiver rated his behavior following the study as “a little more scared” across each of the three categories. By contrast, for Calvin, there seemed to be a mild adverse effect of training (i.e., “a little more scared”) with respect to only one of the three categories (i.e., upset).

Table 1.

Caregiver ratings on side effects questionnaire pre- and posttraining

| Questionnaire item | Wilbur | Calvin | Theodore | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Scared: afraid to leave parents | Neutral | A little more scared | Neutral | Neutral | Very interested | |

| Cautious: hesitant to gooutside or be alone | Somewhat interested | A little more scared | Somewhat interested | Neutral | Very interested | |

| Upset: concerned about the issueof strangers, personal safety, etc. | Neutral | A little more scared | Somewhat indifferent | A little more scared | Indifferent | |

Note. Caregiver ratings for posttraining scores were not returned for Theodore

Discussion

Our results support previous research that suggests that BST alone may not be effective at teaching abduction prevention skills across all participants. The desired performance during stranger test probes (score of 4) was observed following BST for only one of our three participants. Unlike other studies (e.g., Gunby et al., 2010) in which at least some increase in responding (score of 3 or 4) was observed across all participants, the two participants in our study for whom BST was ineffective (Calvin and Theodore) left with the stranger (score of 0), suggesting that BST had no effect on these participants’ responding during test probes.

When BST is ineffective, previous studies have typically included in situ training in which feedback is provided immediately following an error that occurs during test probes (e.g., Beck & Miltenberger, 2009). Rather than provide feedback within the setting reserved for test or generalization probes, we conducted in situ multiple-exemplar training in four novel settings that were not included in probes. In this way, we maintained pre- and posttraining comparison measures in the test and generalization settings for experimental purposes. In situ multiple-exemplar training resulted in a score of 4 during stranger probes for both participants. Perfect responding during tests in novel settings has important practical implications in that a real abduction lure is likely to occur in untrained contexts. In general, our study replicates previous findings showing that additional teaching strategies such as in situ training may be necessary to obtain the desired performance. Our study also extends previous abduction prevention research by demonstrating that conducting in situ training in separate novel settings can result in generalized performance.

Given that children with autism often engage in undesirable generalization of skills (e.g., Rodriguez et al., 2017), a primary aim of our study was to test the effects of typical BST and in situ multiple-exemplar training on the responses of children with autism to requests to leave by familiar adults. Prior to discrimination training, all participants’ responding during familiar test probes covaried with responding during stranger probes. That is, the effects of BST (Wilbur) or in situ multiple-exemplar training (Calvin and Theodore) spread to familiar adults. These results are similar to Ledbetter-Cho et al. (2019), who showed undesirable generalization of the safety response to police officers (i.e., “safe strangers”) with at least three of their four participants.

In our study, undesirable generalization occurred despite participants’ ability to sort pictures of strangers versus familiar adults in our preassessments. Indeed, data from our discrimination training (Fig. 3) suggest that the ability to sort pictures of strangers versus familiar adults (Phase 1), expressively identify whether a person depicted in a picture is a stranger or familiar adult (Phase 2), or state what they should do when presented with a picture of a stranger or familiar adult (Phase 3) had no impact on how participants performed during rehearsals (Phase 5). In fact, it seems plausible that the skills targeted in Phases 1–3 were already within participants’ repertoires given that they immediately reached the mastery criterion during these phases. In other words, knowing the difference between strangers and familiar adults or being able to state what to do if approached by a stranger or familiar adult does not appear to increase the likelihood that participants will perform well during rehearsals with confederates. These results are consistent with studies that have shown that being able to tact the conditions under which a response should occur is insufficient for teaching children how to behave when presented with those same conditions (e.g., Peters & Thompson, 2015), underscoring the need to go beyond curricula that solely teach and test the verbal elements of a target safety skill. Still, research is needed to evaluate the degree to which related verbal skills (e.g., expressive identification of category, intraverbal tact) facilitate correct performance during live rehearsals. For example, it is possible that the intraverbal tact (stating what they should do when approached by a stranger versus familiar adult) may be taught as a covert problem-solving strategy (Axe, Phelan, & Irwin, 2019) for children who are able to follow self-instructions. Although our participants had relatively advanced listener repertoires, we did not obtain any formal data on their ability to serve as their own listener or engage in say–do correspondence (e.g., Lima & Abreu-Rodrigues, 2010).

We included Phase 4 of discrimination training as a preliminary evaluation of alternatives to including real-life confederates, given the practical challenges of recruiting and scheduling numerous confederates for both training and probe phases. However, the ability to perform well during rehearsals in which the experimenter entered the room and presented a lure with a picture of a stranger versus familiar adult in front of her face (Phase 4) did not result in desirable performance with confederates in Phase 5 in which there were live rehearsals with feedback with strangers and familiar adults. Instead, participants required feedback or the addition of a DOR to reach the mastery criterion. By contrast, once the mastery criterion was met across all phases of discrimination training, all participants engaged in perfect discriminated responding during the first test probe, although Calvin’s performance subsequently decreased in the following two sessions. Future research might evaluate the necessary and sufficient conditions of discrimination training, as well as other methods of addressing the practical challenges described previously (e.g., virtual reality).

We also evaluated performance across an additional generalization setting during generalization probes (i.e., the outdoor playground). Two of three participants engaged in perfect discriminated responding during generalization probes; Calvin did not engage in discriminated responding across generalization probes until after booster discrimination training. These results maintained for all participants for up to 3 months. By contrast, performance during community probes (strangers only) was more variable. Because community probes occurred after maintenance probes and were often delayed due to weather or scheduling conflicts (e.g., coordinating with parents, confederates, and informing the store’s staff), the time between the last maintenance probe and the community probes ranged from the same day to 3.25 months for Wilbur, 3 weeks to 1 month for Calvin, and 3 weeks to 3 months for Theodore. Thus, it is difficult to determine whether scores of less than 4 were due, at least in part, to the amount of time that had elapsed since training, the relatively larger difference in setting characteristics, or both. Given these variables and the importance of obtaining generalization, we provided in situ feedback during community probes. Because each community probe occurred in a novel setting, we were able to maintain some measure of generalization. However, conclusions regarding generalization to community settings must remain tentative, as we did not obtain baseline measures of performance in these settings prior to training. Community probes are further limited in that we did not test participants’ performance with familiar adults.

To enhance external validity, we identified features reported to be representative of real-life abduction, such as the types of lures and settings, and incorporated these features into both our testing and training conditions. We also addressed limitations of previous research by increasing the ratio of male to female confederates (cf. Bergstrom et al., 2014). To increase the likelihood of obtaining generalization, we primarily leveraged Stokes and Baer’s (1977) generalization strategy of training sufficient exemplars (e.g., multiple-exemplar training across settings). Future research should continue to design the testing and training conditions based on statistics of real-life abductions, as well as maintain adequate tests of generalization. For example, although we tried to match statistics on real-life perpetrators by increasing the ratio of males to females (i.e., over 75% of our confederates during probes were males), almost all of our confederates were white and between the ages of 20 and 35.

Our affect measures and results from the side effect questionnaire suggest that there might be some adverse side effects of abduction prevention training. Throughout the course of our study, we made sure to program trips to the test and generalization probe settings in which the participants’ therapist briefly left and then returned without the child being approached by a confederate or presented with a lure. As suggested by Johnson et al. (2005), it is possible that a richer schedule of these trips may have reduced potential negative side effects. Another approach may be to teach children the conditions under which they should be wary of strangers. As finer discriminations are taught, the conditions under which negative affect occurs may correspondingly decrease. In other words, a fear reaction to strangers may be appropriate and age typical under some conditions but not others. For example, Ledbetter-Cho et al. (2019) evaluated, and others such as Gunby and Rapp (2014) have discussed, another form of undesirable generalization that may occur following abduction prevention training, in which a stranger who presents no threat appropriately greets the child or initiates conversation. Saying no, running away, and telling an adult under these conditions may be socially stigmatizing and counter to the social skills goals of children with autism. These potential issues highlight both the complexity and importance of identifying and teaching the appropriate skills and the conditions under which they should be emitted. Related to the current study, caregivers may prefer that the child notify someone before they leave with a familiar adult who was not the adult they arrived with. For example, when another familiar adult is present, the appropriate response may be to first say, “OK, let me tell/ask [reporting adult].” Social validity measures from stakeholders should help guide target responses.

Finally, future research might evaluate how discrimination training could be incorporated into other safety skills training (e.g., gun safety, seeking assistance when lost) in meaningful ways and whether doing so can help promote long-term maintenance. Teaching children how to respond when instructed to leave by a stranger versus a familiar adult may be important for maintaining treatment effects after children inevitably contact reinforcement for leaving with a familiar adult. However, neither the effects of contacting reinforcement for leaving with a familiar adult on maintenance of abduction prevention skills nor the effects of discrimination training on long-term maintenance of abduction prevention skills have been empirically evaluated.

Supplementary Information

(DOCX 34 kb)

(DOCX 36 kb)

Acknowledgments

Author Note

All data for this study were collected by Megan Leveque-Wolfe and Jessica Niemeier-Beck, under the supervision and guidance of Nicole Rodriguez. We thank the wonderful staff in the Early Intervention, Virtual Care, Severe Behavior, and Pediatric Feeding Programs for volunteering their time to serve as confederates.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Authors’ Contributions

All data for this study were collected by Megan Leveque-Wolfe and Jessica Niemeier-Beck, under the supervision and guidance of Nicole Rodriguez .

Funding

Internal funding from the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Chancellor’s Office provided partial support for this research.

Data Availability

Data are available from the corresponding author by request.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

All authors declare they have no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent to Participate

University institutional review board approval was obtained, and informed consent was obtained from the parents of all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Axe JB, Phelan SH, Irwin CL. Empirical evaluations of Skinner’s analysis of problem solving. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2019;35:39–56. doi: 10.1007/s40616-018-0103-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck KV, Miltenberger RG. Evaluation of a commercially available program and in situ training by parents to teach abduction-prevention skills to children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2009;42:761–772. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2009.42-761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom R, Najdowski AC, Tarbox J. A systematic replication of teaching children with autism to respond appropriately to lures from strangers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2014;47:861–865. doi: 10.1002/jaba.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreaux ED, Ary RD, Mandry CV, Mccabe B. Determinants of patient satisfaction in a large, municipal ED: The role of demographic variables, visit characteristics, and patient perceptions. American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2000;18(4):394–400. doi: 10.1053/ajem.2000.7316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudreaux MC, Lord WD, Etter SE. Child abduction: An overview of current and historical perspectives. Child Maltreatment. 1999;5(1):63–71. doi: 10.1177/1077559500005001008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll-Rowan, L., & Miltenberger, R. (1994). A comparison of procedures for teaching abduction prevention to preschoolers. Education and Treatment of Children, 17(2), 113–129.

- Elliott M, Browne K, Kilcoyne J. Child sexual abuse prevention: What offenders tell us. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1995;19(5):579–594. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(95)00017-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher MH, Burke MM, Griffin MM. Teaching young adults with disabilities to respond appropriately to lures from strangers. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2013;46:528–533. doi: 10.1002/jaba.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunby KV, Carr JE, LeBlanc LA. Teaching abduction prevention skills to children with autism. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:107–112. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunby KV, Rapp JT. The use of behavioral skills training and in situ feedback to protect children with autism from abduction lures. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2014;47:856–860. doi: 10.1002/jaba.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammer, H., Finkelhor, D., & Sedlak, A. J. (2002). Children abducted by family members: National estimates and characteristics (Juvenile Justice Bulletin No. NCJ196466). Washington, DC: Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention.

- Himle MB, Miltenberger RG, Flessner C, Gatheridge B. Teaching safety skills to children to prevent gun play. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2004;37:1–9. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2004.37-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingvarsson ET, Hollobaugh T. Acquisition of intraverbal behavior: Teaching children with autism to mand for answers to questions. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:1–17. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson BM, Miltenberger RG, Egemo-Helm K, Jostad CM, Flessner C, Gatheridge B. Evaluation of behavioral skills training for teaching abduction-prevention skills to young children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2005;38:67–78. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2005.26-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledbetter-Cho K, Lang R, Davenport K, Moore M, Lee A, O’Reilly M, Falcomata T. Behavioral skills training to improve the abduction-prevention skills of children with autism. Behavior Analysis in Practice. 2016;9:266–270. doi: 10.1007/s40617-016-0128-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledbetter-Cho, K., Lang, R., Lee, A., Murphy, C., Davenport, K., Kirkpatrick, M., et al. (2019). Teaching children with autism abduction-prevention skills may result in overgeneralization of the target response. Behavior Modification. 10.1177/0145445519865165. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lima EJ, Abreu-Rodrigues J. Verbal mediating responses: Effects on generalization of say-do correspondence and noncorrespondence. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2010;43:411–424. doi: 10.1901/jaba.2010.43-411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miltenberger R, Olsen L. Abduction prevention training: A review of findings and issues for future research. Education and Treatment of Children. 1996;19(1):69–82. [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Missing and Exploited Children. (2020). Nonfamily abductions and attempts. Retrieved October 20, 2020, from https://www.missingkids.org/theissues/nonfamily.

- Peters LC, Thompson RH. Teaching children with autism to respond to conversation partners’ interest. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2015;48:544–562. doi: 10.1002/jaba.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poche C, Brouwer R, Swearingen M. Teaching self-protection to young children. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1981;14:169–175. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1981.14-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez NM, Levesque MA, Cohrs VL, Niemeier JJ. Teaching children with autism to request help with difficult tasks. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2017;50:717–732. doi: 10.1002/jaba.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shillingsburg MA, Powell NM, Bowen CN. Teaching children with autism spectrum disorders to mand for the removal of stimuli that prevent access to preferred items. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. 2013;29:51–57. doi: 10.1007/bf03393123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes TF, Baer DM. An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 1977;10:349–367. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1977.10-349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundberg ML. Verbal behavior milestones assessment and placement program. Concord, CA: AVB; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson C, Brewer N. The incidence of criminal victimisation of individuals with an intellectual disability. Australian Psychologist. 1992;27(2):114–117. doi: 10.1080/00050069208257591. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 34 kb)

(DOCX 36 kb)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available from the corresponding author by request.