Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Providing financial resources for health services is one of the most important issues in the study of health systems, of which purchasing health services is very essential. The World Health Organization considers strategic purchasing as a key option for improving the performance of health systems. The aim of this study was to identify payment methods for service providers and strategic purchasing strategies in upper middle income countries.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

The present study was conducted in the form of a comparative analysis involving comprehensive surveys from 2000 to 2019, by searching keywords for the objective of the study by the search engines through databases including ProQuest, PubMed, Google Scholar, Irandoc, SID, Magiran, Science Direct, Scopus, ISI Web of Science, EBSCO, and Cochrane.

RESULTS:

A total of five upper middle income countries that used strategic purchases entered the study. Overall, all of them implemented rather similar strategies in terms of strategic purchasing and paying to the providers of the services.

CONCLUSION:

According to the results of this study, per capita payment for primary health-care and outpatient services seems to be the best option for controlling the costs of the health sector, while the appropriate option for the inpatient department is the most common use of diagnosis-related group. The payment method is to control the costs of the inpatient department.

Keywords: Health system, payment method, strategic purchasing, strategy

Introduction

Health systems represent all organizations, institutions, and resources, which carry out the activities to provide, promote, and restore the health services. The ternate objectives of the health systems include the promotion of public health in the area of application, addressing nonmedical expectations but relevant to the public health as well as financial supporting against the inequitable expenditures of health.[1] To meet these objectives, every health system is obliged to do the following four functional performances concordantly: custodianship, investment for supplies and resources, providing health services, as well as financial supporting.[2] Financial supporting is one of the most important functions in all health systems possessing sub-functions of resources collection, risk accumulation, resources management, as well as services purchase.[3,4] Among the issues related to financial supporting, purchasing the health services is one of the most important issues (it is effective due to ensuring the type of the intervention providing, promotion of the system response, and equitability of financial cooperation). In this regard, the World Health Organization (WHO) defines strategic purchasing as a fundamental option for the promotion of the health system performance.[5,6]

Strategic purchasing involves the continuous search to achieve defined methods via decision-making about the type, manner, and from whom the buying should be done to maximize the efficiency of the system performance. In other words, strategic purchasing is defined as the interventions that will increase the system response and optimize the financial balance.[7] On the other hand, strategic purchasing is one of the main elements of promotion of health system performance, which in an ideal condition can potentially raise the efficiency and efficacy, as well as response the system. Furthermore, it has an important role in attaining the objectives of the public health and more extensive goals of social equity in the health-care system.[8]

The WHO, as one of the most high ranking organizations in policy making, has suggested that the movement from mechanisms of the passive purchasing toward strategic purchasing of health-care services confronts with five essential challenges that are known as the five political axes of purchasing including, namely (1) who to buy from? (selecting of suppliers); (2) who to buy for? (ensuring the accessibility of appropriate services for the poor and deprived classes of the society); (3) what to buy? (prioritizing the health-care services); (4) how to pay? (comprehending the concepts and motivations of the payment); and (5) what prices are suitable? (sensible and payable prices).[9,10,11,12]

Among these issues, the methods of payment to the suppliers are important. As these payment methods are some tools for governing and the axes for policymaking, recognition and monitoring of tariffs and methods of payment in health-care systems must be prioritized.[13] If these tariffs and methods of payment are defined based on technical and scientific principles, the subsequent effects would be much more appropriate and influential on the motives and behavior of the procurers and members involved in health-care systems, as well as the costs, quantity and quality of services, and customer satisfaction. Given this background, the present study aims to identify the methods of payment to suppliers of services pertaining to strategic purchasing in countries with moderate to high levels of income. The findings can be exploited by policymakers to aid them in their selection and execution of buying strategies and suitable methods of payment concerning the national health-care system.

Materials and Methods

The present study was conducted in 2019 as a comparative study related to Strategic purchasing and the performance of health-care systems in upper middle income countries. In this study, preferential reported case guidelines for systematic review and meta-analysis (PRISMA) and critical assessment skills program (CASP) were used to evaluate articles. This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Iran University of Medical Sciences with the ethics code IUMS.Rec1396,31507.

Search strategy

To achieve this goal, databases including ISI web of science, PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct, Ovid, Pro Quest, Wiley and Google Scholar was reviewed between 2010 and 2019. The keywords used and the search strategy are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search strategy

| Search Engines and Databases | Google, Google Scholar, PubMed, ProQuest, EBSCO, ISI Web of Science, Scopus, Science Direct, Cochrane, springer (2000 to present) |

| Persians engines | Magiran, Irandoc, Sid |

| Keywords | Strategic OR active OR proactive |

| Purchasing OR contracting OR commissioning OR procurement | |

| Health system* OR healthcare OR health care OR health service* | |

| Payment system* OR payment method* OR payment mechanism* | |

| Argentina OR Angola OR American Samoa OR Algeria OR Albania OR Azerbaijan OR Belarus OR Belize OR Bosnia and Herzegovina OR Botswana OR Brazil OR Bulgaria OR China OR Colombia OR Costa Rica OR Cuba OR Dominica OR Dominican Republic OR Ecuador OR Equatorial Guinea OR Fiji OR Gabon OR Georgia OR Grenada OR Guyana OR Iraq OR Jamaica OR Jordan OR Kazakhstan OR Lebanon OR Libya OR Macedonia OR Malaysia OR Maldives OR Marshall Islands OR Montenegro OR Namibia OR Palau OR Peru OR Romania OR Russian Federation OR Serbia OR South Africa OR St. Lucia OR St. Vincent and the Grenadines OR Suriname OR Thailand OR Turkey OR Turkmenistan OR Venezuela OR Tuvalu OR Mauritania OR Mexico OR Paraguay OR Panama | |

| Upper middle income |

Selection of articles and document

Independent reviewers (MH and EM) screened abstracts and titles for eligibility. When the reviewers felt that the abstract or title was potentially useful, full copies of the article were retrieved and considered for eligibility. If discrepancies occurred between reviewers, the reasons were identified and a final decision was made based on the third reviewer (AJ) agreement. Two authors (MH and EM) assessed the methodological quality and grade of evidence of included studies with the CASP tools. The CASP tools use a systematic approach to appraise different study designs from the following domains: study validity, methodology quality, presentation of results, and external validity and all the items from the checklists were judged with yes (low risk of bias, score 1), no (high risk of bias), or cannot tell (unclear or unknown risk of bias, score (0). Total scores were used to grade the methodological quality of each study assessed (11).

Eligibility criteria

We searched papers that mentioned (1) Strategic purchasing (2) upper middle income countries (3) English or Persian language, (4) perfect structure, (5) Internal article that has been printed in scientific and research journals, and 6) published paper in the year 2010 and after.

Study quality assessment

Quality assessment of the included studies was done using the (CASP) and (ACCODS) tools. The score of quantitative studies ranged from two to nine. The majority of quantitative studies did not provide any ethical statement, study design, sampling, and reflexivity related to the research process.

Results

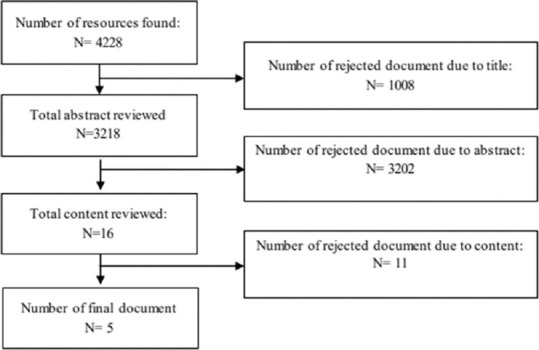

A total of 4228 articles were retrieved according to the search strategy. Five eligible records were selected based on the inclusion criteria [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Article selection flowchart

Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, five countries, including Turkey, Macedonia, Thailand, China, as well as Columbia, which used purchasing strategies, were selected for further investigations.

Table 2 illustrates a strategic purchasing model in the countries with upper middle income

Table 2.

Strategic purchasing in countries with upper middle income

| Country | Source of financing | Proceedings for strategic purchasing (strategic purchasing model) | Service buyer organization | Buyer-supplier segregation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Turkey[14] | Public funding 29.1% tax 43.9% public health insurance Private funding 17.4% out of pocket 9.6% private sector |

Exclusivity of the public sector in the provision of public health services Contracts with the public sector for provision of outpatient and hospitalization services |

Singular SSI |

+ |

| Macedonia[15] | Public funding Tax public health insurance Private funding Out of pocket Out of pocket Insignificant private insurance |

Contracts with public sector | Singular HIF |

+ |

| Thailand[16] | Public funding (77%) Tax Public health insurance Private funding (12.4%) Out of pocket Insignificant private insurance |

Exclusivity of the public sector in provision of public health services Contracts with the public sector for provision of outpatient and hospitalization services |

Multiple CGD SSO NHSO |

+ |

| China[17] | Public funding 30% tax Public health insurance Private funding 34.4% out of pocket Insignificant private insurance |

Exclusivity of the public sector in provision of public health services Contracts with the public sector for provision of outpatient and hospitalization services |

Multiple UEMBI URMBI NRCMS |

+ |

| Columbia[18] | Public funding Central government taxes Public health insurance Municipality taxes Private funding Out of pocket Private insurance |

Exclusivity of the public sector in provision of public health services Contracts with the public sector for provision of outpatient and hospitalization services |

Multiple Municipalities for the unofficial or SR sector Health promoting entities for the official sector |

+ |

SSI=Social security insurance, HIF=Health insurance fund, SR=Subsidy receiving, -

Table 2 shows that the primary source of financing in health systems in the mentioned countries is attributed to the public sector, with the most frequently employed strategy for the provision of public health ascribed to the exclusivity of the public sector for the delivery of services as well as contracts with the public sector for the provision of both outpatient and hospitalization services. The buyer–supplier segregation, as can be seen, has been deployed in all countries. Only two countries had access to individual funds for the purchase of health services, whereas three other countries profit from multiple funds for this purpose.

As shown in Table 3, public health services in all countries, except a county, are provided by the public sector and the most common method of payment is per capita that it has been profited from performance-based method for creating motivation. Outpatient services were provided by both governmental and private sectors and per capita payment was the most frequent method of payment. In hospitalization services, like outpatient, the providers are governmental and private sectors and the most common method of payment to hospitals is diagnosis-related group (DRG).

Table 3.

Methods of payment to suppliers of health services in the studied countries

| Country | Public health services | Outpatient services | Hospitalization services | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supplier | Method of payment | Supplier | Method of payment | Supplier | Method of payment | |

| Turkey | Ministry of health, municipalities | Per capita | Governmental | Per capita | Governmental Private | Pension and performance based |

| Macedonia | Private sector | Per capita with remuneration for rural regions | Governmental Private | Total budget and performance based | Governmental Private | + DRG |

| + Conditional budget and fee of service (performance based) | ||||||

| Thailand | Ministry of health | Per capita | Governmental Private | Per capita for two plans and performance based for one plan | Governmental private | + DRG with surplus payment for emergency and expensive services in two insurance plans |

| Per capita, with payment surplus for emergency and expensive services in one plan | ||||||

| China | Ministry of health | Per capita + fee-of-service (performance based) | Governmental Private | Per capita | Governmental Private | DRG |

| Columbia | Ministry of health | Per capita | Governmental Private | Per capita | Governmentalprivate | DRG |

DRG: Diagnosis-related group

Discussion

Strategic purchasing is one of the main components to promote health systems’ performance, which can increase the efficiency and efficacy as well as response in its ideal status[19] and also, it plays an important role to achieve the public health objectives and more supreme goals of social justice in the health system.[20,21] Therefore, in a desired condition, interventions in the health sector, based on the resources management as a unique fund, can be utilized for the purpose of purchasing the health services in the framework of a prioritized system with clear sharing and ensured basic health services delivery as well as reducing the cost of illness risk for the patients.[5]

However, the basic question in this situation is the recognition of the methods of payment to the suppliers. The mentioned payment methods act as a governing tool to lead to policy making. Therefore, one of the highest priorities of the health system is determination and control of the tariffs and methods of payment for health service sector. As long as these tariffs and methods of payment be based on technical and scientific principles, they would have appropriate and efficient impress on the motivation and behavior of the health system actors as well as costs, quantity and quality of the services, and most importantly patient satisfaction.

The primary resources of the public financing in all studied countries involve tax and public health insurance, and the private resources of funding are mainly out-of-pocket payments and private insurance. The strategic purchasing model of all countries was exclusivity public sector in providing health services as well as conventional of public sector to deliver both outpatient and hospitalization services.

The service buyer organization in Turkey and Macedonia is solitary, and they are social services and health insurance fund organizations, respectively,[14,15] but they are numerous in Thailand, China, and Columbia.[16,17,18]

These organizations in Thailand include CGD, SSO, and NHSO; in China involve Urban Employees’ Basic Medical Insurance, URMBI, and NRCMS; and in Columbia are the municipalities for unofficial or subsidy receiving sectors as well as health-promoting entities (EPS) for the official sector. The buyer–supplier segregation has been seen in all countries.

In public service sector, the method of payment to suppliers is carried out by the Ministry of Health in all countries except Macedonia. In addition, the payment method in this sector in all countries is per capita and some countries such as Macedonia and China use different methods such as reward, performance-based method, as well as per capita.

In outpatient service sector, all countries except Turkey, in which the government provide all services, use a combination of both governmental and private sectors for the service providers. The method of payment in this sector, in all countries, is per capita like public services, except Macedonia. The payment method in this country is in the format of total budget and fee for service. In hospitalization service sector, service providers are the combination of both the governmental and private sectors in all the studied countries.

All countries, except Turkey, employed DRG as the method of payment for hospitalization services. Thailand hired DRG in one plan for hospitalization services, with payment surplus used for either extremely expensive or emergency services. In another plan, this country had used per capita along with payment surplus for emergency and expensive services.

In Macedonia, the method of payment in hospitalization services sector is paid using the combination of DRG accompanied with conditional budgets and performance based. Finally, in Turkey, it is paid in the form of salary payment and fee for service to suppliers.

Conclusion

According to the findings, it seems that per capita payment is the best option for the primary health-care and outpatient services to control the health sector costs, while, in the hospitalization services, the proper method of payment is DRG which is the most common method to control the costs of hospitalization.

For this purpose, it is recommended that in Iran's health system, the payment method of the organizations in the outpatient and hospitalization services has been changed to per capita and DRG, respectively, and for the staffs who provide health-care services, it has been shifted to performance-based method. It is obvious that the use of these methods of payment would not be the only solution; however, by using the world experiences and complementary strategies, an attempt can be made to prevent the potential and possible drawbacks of the mentioned methods.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Institute of Health Research of Iran, Tehran University of Medical Sciences Tehran, Iran (grant number 96-02-163-31507).

References

- 1.World Health Organization the World Health Report 2000. Health System: Improving Performance. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathauer I, Wittenbecher F. Hospital payment systems based on diagnosis-related groups: Experiences in low- and middle-income countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:746–756A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.115931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.González-Block MÁ Alarcón Irigoyen J, Figueroa Lara A, Ibarra Espinosa I, Cortés Llamas N. The strategic purchasing of health services: A big opportunity for the National Universal Health System. Gac Med Mex. 2015;151:278–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joint Learning Network; Mongolia Ministry of Health; World Bank; World Health Organization. Implications for equity, efficiency and universal health Coverage: A report [2015] Washington, DC: World Bank; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ogundeji YK, Bland JM, Sheldon TA. The effectiveness of payment for performance in health care: A meta-analysis and exploration of variation in outcomes. Heal Pol. 2016;120:1141–50. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2016.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silva E, 3rd, McGinty GB, Hughes DR, Duszak R., Jr Traditional payment models in radiology: Historical context for ongoing reform. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13:1171–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2016.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nasiripour AA, Raeissi P, Tabibi SJ, Karimi K. Variables affecting the payment mechanism for strategic purchasing in the indirect health section of Iranian social security organization. Int Bus Res. 2011;4:10328. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mehralian G, Bastani P. Pharmaceutical strategic purchasing: A key to improve access to medicines. Iran J Pharm Res. 2015;14:345–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bastani P, Dinarvand R, SamadBeik M, Pourmohammadi K. Pharmaceutical strategic purchasing requirements in Iran: Price interventions and the related effective factors. J Res Pharm Pract. 2016;5:35–42. doi: 10.4103/2279-042X.176553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bastani P, Mehralian G, Dinarvand R. Resource allocation and purchasing arrangements to improve accessibility of medicines: Evidence from Iran. J Res Pharm Pract. 2015;4:9–17. doi: 10.4103/2279-042X.150045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang H, Wernz C, Hughes DR. Modeling and designing health care payment innovations for medical imaging. Health Care Manag Sci. 2018;21:37–51. doi: 10.1007/s10729-016-9377-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bahadori M, Sadeghifar J, Ravangard R, Salimi M, Mehrabian F. Priority of determinants influencing the behavior of purchasing the capital medical equipments using AHP model. World J Med Sci. 2012;7:131–6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Roodenbeke, Eric. Purchasing Inpatient and Outpatient Care through Hospitals. Health, Nutrition and Population (HNP) discussion paper;. World Bank. Washington, DC. © World Bank: 2004. pp. 1–8. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/13728License: CC BY 3.0 IGO . [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jegers M, Kesteloot K, De Graeve D, Gilles W. A typology for provider payment systems in health care. Heal Pol. 2002;60:255–73. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8510(01)00216-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Honda A, Hanson K, Tangcharoensathien V, Huntington D, McIntyre D. Strategic purchasing– Definition and analytical framework used in the multi- country study. In: Honda A, McIntyre D, Hanson K, Tangcharoensathien V, editors. Strategic Purchasing in China, Indonesia and the Philippines. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Besciu CD. The Romanian healthcare system and financing strategies. Procedia Soc Behav Sci. 2014;149:107–13. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tatar M, Mollahaliloğlu S, Sahin B, Aydin S, Maresso A, Hernández-Quevedo C. Health systems in transition.Turkey. Health Syst Rev. 2011;13:38–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milevska Kostova N, Chichevalieva S, Ponce NA, van Ginneken EV, Winkelmann J. The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia: Health system review. Health Syst Transit. 2017;19:1–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.World Health Organization. The Kingdom of Thailand health system review Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific. 2015;5:5. [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Policies” Asia Pacific Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Health Care Reform; Health Expenditures; Health Systems Plans. 7. Vol. 5. China Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Health systems in transition; [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernando Montenegro Torres and Oscar Bernal Acevedo, Colombia Case Study: The Subsidized Regime of Colombia's National Health Insurance System. Washington DC: The World Bank; 2013. [Google Scholar]