Abstract

There is a lack of conceptual clarity about the role of delivering private hospital services (DPHS) accompanied by major gaps in evidence. The purpose of this systematic scoping review was to identify and map the available evidence regarding the developing countries to scrutinize the participation of DPHS exclusively in the universal health coverage (UHC) through providing graphical/tabular classifications of the bibliometric information, sources of the records, frequent location, contribution of the private hospital services in the health system, and roles of DPHS in UHC. This study was performed following the published methodological guidance of the Joanna Briggs Institute for the conduct of scoping review, applying some major databases and search engines. In addition, a narrative-thematic synthesis integrated with the systematic analysis using the policy framework of the World Health Organization was employed. The 28 included records in English which met the inclusion criteria were found between 2014 and January 2020. The chronological trend of records was progressive until 2019. India was the most frequent location (12%). China and Sri Lanka on the one end of the spectrum and Somalia along with South Korea from the other end were, respectively, the least and the most contributed countries in terms of DPHS. Overall, 90% of the roles were concerned with UHC goals. Although evidence has revealed inconsistency in the identified roles, a continuous chain of positive or negative effects in the UHC objectives and goals was observed. Some knowledge gaps about the roles, causes of the increasing and decreasing DPHS contribution, and its behaviors around the privatization types and circumstances of the delivery were recommended as prioritized research agendas for evidence-based policymaking in future.

Keywords: Policymaking, private hospitals, universal coverage, universal health

Introduction

Although universal health coverage (UHC)[1] is grounded in public health-care systems, efforts toward UHC cannot ignore the private sector (PS).[2,3] In particular, the provision of hospital services is one economic activity that has the greatest potential for PS involvement in developing countries,[4] and even this sector plays a crucial role in many low-income countries.[5] There is an urgent need to build the capacity of all countries to better manage the PS and mixed health systems to ensure that all providers, whether public and private, effectively contribute to a country's goals for UHC,[6,7] and policymakers must identify and ensure appropriate roles for private providers and health markets toward UHC.[8]

Existing knowledge and statement of the objective

There are a growing appreciation and diagnosis of the role of the PS in the development of better health systems and the improvement of health care worldwide,[9] and also a fair amount of experience has been gained on how to work with the PS in developing countries, however there is no conceptual clarity and sufficient evidence about the role of this sector in health systems,[6,10] particularly in UHC.[11] For example, there are some different kinds of scientific literature about the participation or role of private service delivery that was not in the context of UHC,[4,12,13,14] or did not consider private hospital services (PHS).[15,16]

Furthermore, despite some evidence found on the extracted data of some mapping or scoping studies,[10,17,18] there is a lack of evidence that has scrutinized the contribution of delivering private hospital services (DPHS) in UHC systematically, looking at the UHC objectives and goals. Filling the above-mentioned gaps has aimed this systematic scoping review, to shed light on this to show the interested stakeholders. The objective of the current study was to identify and map the current evidence regarding the participation of DPHS in the UHC journey of the developing countries through providing graphical/tabular classifications of some major information.

Theoretical framework

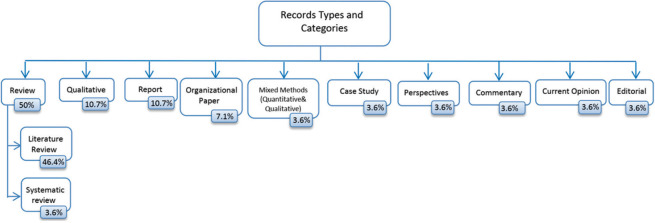

UHC is a set of objectives that health systems pursue, not as a scheme or a particular set of ingredients and settings in the health system.[19] Advancing UHC within the complexity of the health systems requires systems thinking[20] that believes in the evaluation of the effects to describe and to quantify the health outcomes of the interventions as well as its impact on the overall goals/outcomes of the health system.[21] Referring the systems’ perspective in achieving UHC objectives and goals, the World Health Organization's (WHO) approach to the health systems framework[22] [Figure 1] was chosen as a theoretical framework.

Figure 1.

Health system and universal health coverage objectives and goals

Materials and Methods

Study approach

This review was conducted from July to December 2018 and updated in January 2020. We performed a systematic scoping review adopted following the nine-step published methodological guidance of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) for the conduct of scoping reviews,[23] that is congruent and consistent with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist[23,24] accompanied by narrative synthesis integrated with the systematic analysis as knowledge synthesis methods[25,26] to meet the objective.

Research questions

Regarding the guidance, according to the PCC elements[23,27] (Population: Private hospitals, Concept: Service delivery, and Context: UHC in developing countries), four sets of research questions were derived from the objective of the study that is shown in [Table 1].

Table 1.

Research question sets and subsets

| Question sets and subsets | Considerations |

|---|---|

| BRQ | |

| BRQ 1 - Record trend and types: What are the status and the chronological trends of various types of available evidence about the participation of the DPHS in UHC with respect to their various categories, and approaches? This question can be considered as a preliminary exercise prior to the conduct of a systematic review and can be provided a foundation to audiences for a future investigation of a systematic review | Evidence about DPHS dealing with UHC was found and selected [Figure 3]. In the absence of explicit research design in some of the records, the designs were determined by analyzing the circumstances of the information and the activities utilized |

| BRQ 2 - Sources of the records: Which journal/organization contains the largest number of available evidences about the participation of the DPHS in UHC? What is the most specialized journal in the field? The answer to this question helps researchers select appropriate journals for topics and subjects related to DPHS in UHC | The sources of the retrieved records were reported based on the referred journal or corresponding organization |

| CRQ | |

| CRQ - The frequent location: Which country/setting is the most frequent among the geographical coverage of the included records? The answer to this question underlines leading countries or regions related to the participation of the DPHS in UHC to international and national stakeholders | The geographical coverage of the records was searched to find the location that was mentioned empirically around the participation of the DPHS and UHC. Where the document was about a region (a set of countries) and the data were presented as a general conclusion and not separately for each country, the coding was done based on the region |

| PRQ | |

| PRQ - Contribution of the PHS in the health system: How are the contributions of the PHS in the communities’ health systems journey to UHC? What methods or indicators are used to express it? Which method or indicator is more common? This question helps the policy and decision makers to understand the PHS involvement in UHC | In this review, the contributions of the PHS in the health systems were considered %PHB, %PH, and %PHS. It was responded according to available evidence, wherever had been exactly reported |

| CoRQ | |

| CoRQ - Roles of DPHS: What are the roles of DPHS contribution in achieving UHC? How is the relationship between the contribution of DPHS and its role? This question shows the gaps and opportunities for future work | It was attempted to be discovered regarding the theoretical framework which was defined as any positive or negative effect[21] in terms of UHC intermediate objectives and final coverage goals. According to the context of UHC, quality should have been analyzed based on the definition of the WHO framework on integrated people-centered health services,[58] however some of the dimensions of this definition (efficiency and quality) were used in the analysis of the some objectives and goals, thus the classification proposed by Berendes et al.[39] was used to avoid duplication |

BRQ=Bibliometric research questions, DPHS=Delivering private hospital services, UHC=Universal health coverage, CRQ=Context research questions, PRQ=Population research questions, PHS=Private hospital services, CoRQ=Concept research questions, WHO=World Health Organization, PHB=Private hospital beds, PH=Private hospitals, %PHB=Private hospital beds as a percentage of total hospital beds, %PH=Private hospitals as a percentage of total hospitals, %PHS=Share of private hospital services as a percentage of total hospital services market

Inclusion criteria

Defining the PCC elements for scoping reviews was an important step in developing the inclusion and exclusion criteria[23,27,28] [Table 2] to arrive at a shared understanding. To obtain the comprehensive resources and to find the records which were not indexed in databases, all relevant documents including gray literature were searched.

Table 2.

The population, concept, and context elements definitions, inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Types of sources | |

| The full text of evidence was available | The full text of evidence was not available |

| The evidence was peer-reviewed articles or gray literature (whether empirical or nonempirical, commentary, editorial) | |

| Population | |

| The evidence was about all types of PHS including formal, for-profit, nonprofit, domestic, and international that could be active even inside of governmental hospitals[2] and also in terms of privatization forms was corporatization, outsourcing, PPP, and the full or partial sale of the public[38] | The evidence was about PHS regarding formal entities and traditional healers, PPP for construction, renovation, building alterations, management contract, and also nonformal entities |

| Concept | |

| The evidence pointed to DPHS that service delivery includes effective, safe, and quality personal and nonpersonal health interventions that are provided to those in needs, when and where needed, with minimal waste of resources[21] | The evidence was about the role of the other functions of the health system in UHC |

| Context | |

| The evidence was related to UHC that has been considered as cube proposed by the WHO that provides three interrelated components,[40,59] and in developing countries based on the WESP classifications[60] | The evidence was about universal health insurance or university hospital care. |

| The evidence was related to developed or in transition countries |

PHS=Private hospital services, PPP=Public-private partnership, DPHS=Delivering private hospital services, UHC=Universal health coverage, UHC=University hospital care, WESP=World Economic Situation and Prospects

Search strategy

A three-step search strategy as recommended in JBI guidance[23] was employed after defining the research questions using PCC. Following initial scoping searches of online relevant databases and search engines (PubMed, Embase, and Google Scholar) using MeSH terms, Emtree, and similar studies, a list of the search terms and inclusion criteria were developed. Full searches were then carried out regardless of the time and language limitations. To identify gray literature such as dissertations and reports, some search engines were used [Figure 2], and the search results were sorted by relevance. The inclusion of the search results was continued up to it was explicitly obvious that the listed results were no longer relevant. The reference lists of the identified records were searched and thus backward and forward-searching was also employed. Full details of some search strategies covering search terms are provided in Box 1.

Figure 2.

A flow diagram describing the selection process, reasons for exclusion, and final record number

Box 1.

Some search strategies and search terms for this review

| Search in PubMed through both MeSH terms and manual search: |

| (((((((((((((“Private Sector”[tiab]) OR “private sector”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“Private Sector”[tiab] OR “Private Sectors”[tiab])) OR (“Private Enterprise”[tiab] OR “Private Enterprises”[tiab])) OR (“Public Private Partnerships”[tiab] OR “Public Private Partnership”[tiab])) OR “public private sector partnerships”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“Public Private Sector Partnerships”[tiab] OR “Public Private Sector Partnership”[tiab])) OR (“Public Private Cooperation”[tiab] OR “Public Private Cooperations”[tiab])) OR “public private cooperation”[Title/Abstract]) OR (“public private sector cooperation”[tiab] OR “public private sector cooperations”[tiab])) OR (“Private Hospitals”[tiab] OR “Private Hospital”[tiab])) OR “private hospital”[Title/Abstract])) AND ((((“UHC”[tiab] OR “UHC”[tiab])) OR “UHC”[Title/Abstract]) OR “UHC scheme”[Title/Abstract]) |

| Search in Embase through both Emtree and manual search: |

| (‘private sector’/exp OR ‘private hospital’/exp OR ‘public-private partnership’/exp OR ‘private sector’:ab, ti OR ‘private sectors’:ab, ti OR ‘private hospital’:ab, ti OR ‘private hospitals’:ab, ti OR ‘public private partnership’:ab, ti OR ‘public private partnerships’:ab, ti OR ‘private economy’:ab, ti OR ‘for profit hospital’:ab, ti OR ‘for profit hospitals’:ab, ti OR ‘investor owned hospitals’:ab, ti OR ‘investor owned hospital’:ab, ti OR ‘private clinic’:ab, ti OR ‘private clinics’:ab, ti OR ‘public-private sector partnerships’:ab, ti OR ‘public-private sector partnership’:ab, ti OR ‘private-public collaboration’:ab, ti OR ‘private-public collaborations’:ab, ti OR ‘private-public cooperation’:ab, ti OR ‘private-public cooperations’:ab, ti OR ‘private-public mix’:ab, ti OR ‘private-public mixes’:ab, ti) AND (‘universal health coverage’ OR uhc) |

| Search through SCOPUS: |

| TITLE-ABS-KEY((“private sector” OR “Private Sectors” OR “Private Enterprise” OR “Private Enterprises” OR “Public Private Partnerships” OR “Public Private Partnership” OR “public private sector partnerships” OR “Public Private Sector Partnerships” OR “Public Private Cooperation” OR “Public Private Cooperations” OR “public private sector cooperation” OR “public private sector cooperations” OR “Private Hospitals” OR “Private Hospital”) AND (“universal health coverage” OR “UHC”)) |

UHC = Universal health coverage

Selection of the evidence

All records identified in the search were managed by bibliographic software (EndNote version X8) to remove duplicates and facilitate the reviewing process. According to [Figure 2], the identified records were reviewed at all stages based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria according to the PCC. The judgment about the fitness of records was made by both authors, and any discrepancies were resolved in discussion with each other. The interdisciplinary essence of the retrieved records and the challenges of applying quality criteria across the research paradigms meant that the appraisal of the final included records, which has been classified in Table 3, was confined to considerations of relevance rather than research quality.

Table 3.

Contributions of evidence on the participation of the delivering private hospital services in universal health coverage (sorted by time)

| Authors/reference | Title | Year | Type of review | Contributions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMRO[10] | Analysis of the private health sector in countries of the Eastern Mediterranean: an exploring unfamiliar territory | 2014 | Report | Presents information on trends in privatization and implications for the private health sector Display the current status of the private health sector in countries of the region Discusses challenges and gaps in relation to the private health sector |

| Mackintosh et al.[8] | What is private sector? understanding private provision in the health systems of LMICs | 2016 | Report | Proposed a set of metrics to identify the structure and dynamics of private provision in their particular mixed health systems, and to identify the consequences of specific structures, the drivers of change, and levers available to improve efficiency and outcomes |

| Montagu and Goodman[32] | Prohibit, constrain, encourage, or purchase: how should we engage with the private health-care sector? | 2016 | Systematic review | Reviewed the evidence for the effectiveness and limitations of such private sector interventions in LMICs |

| McPake and Hanson[56] | Managing the public-private mix to achieve UHC | 2016 | Review | Extrapolated and discussed main messages from the papers to inform policy and research agendas in the context of global and country-level efforts to secure UHC in LMICs |

| Tsevelvaanchig et al.[49] | Role of emerging private hospitals in a post-Soviet mixed health system: a mixed-methods comparative study of private and public hospital inpatient care in Mongolia | 2017 | Mixed-methods approach of quantitative and qualitative techniques | Identified the geographical distribution of private hospital admissions Showed the main types of private inpatient services delivered by private hospitals, in comparison with public hospitals Highlighted reasons for the urban concentration of private hospital admissions Identified conditions that do not require hospitalization and root causes |

| Gele et al.[35] | Beneficiaries of conflict: a qualitative study of people’s trust in the private health-care system in Mogadishu, Somalia | 2017 | Qualitative | Explored the accessibility to, as well as people’s trust in, the private sector |

| Sean et al.[53] | Organizing health coverage goals of the private sector to support universal | 2017 | Report | Highlighted success stories: SHOPS Plus examined six diverse countries (Japan, The Philippines, Indonesia, Brazil, Germany, and South Africa) that have successfully organized private providers to identify lessons on strengthening their voice, improving quality of care, and expanding their access to revenue opportunities |

| Maurya et al.[46] | Horses for courses: moving India toward UHC through targeted policy design | 2017 | Current opinion | Presented information on health system and policy options for universal coverage Investigated challenges of replicating high-performing primary health-care systems nationally Reviewed experience of purchasing care in social health insurance programs and improving the effectiveness of Shi programs |

| Zaidi et al.[17] | Expanding access to health care in South Asia | 2017 | Review | Present recent proliferation of policy initiatives Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India |

| Alami[54] | Health financing systems, health equity, and UHC in Arab countries*** | 2017 | Literature review | Placed the region in an international context, benchmarking reform efforts against the experiences of developing countries in working toward UHC |

| Zodpey and Farooqui[45] | UHC in India: Progress achieved and the way forward | 2018 | Editorial | Suggested the way forward for UHC in India |

| Makinde et al.[61] | Distribution of health facilities in Nigeria: Implications and options for UHC | 2018 | Review | Reviewed the geographic and sectoral distribution of health facilities in Nigeria Discussed implications on the UHC strategy selected |

| Tangcharoensathien et al.[62] | Health systems development in Thailand: A solid platform for successful implementation of UHC | 2018 | Review | Presented successful implementation of UHC in Thailand |

| Kwon[36] | Advancing UHC: What developing countries can learn from the Korean experience? | 2018 | Organizational paper study series | Presented Korean experience in advancing UHC |

| EMRO[43] | Private sector engagement for advancing UHC | 2018 | Organizational paper | Presented the current state of the private health sector in the EMR Explained why engagement with the private health sector in service delivery is necessary Proposed a framework for action for effective engagement with the private health sector to move toward UHC The framework for the analysis of the private health sector followed the conceptual framework of the six-health system building blocks |

| Lu and Chiang[51] | Developing an adequate supply of health services: Taiwan’s path to UHC | 2018 | Review | Analyzed how Taiwan historically built up the supply of health services that made achieving UHC possible Identified four key strategies adopted in the health service sector development |

| Tsevelvaanchig et al.[48] | Regulating the profit of private health-care providers toward UHC: A qualitative study of legal and organizational framework in Mongolia | 2018 | Qualitative | Maps the current regulatory architecture for private health care in Mongolia Explored its role for improving accessibility, affordability, and quality of private care and identified gaps in policy design and implementation |

| Chapman and Dharmaratne[34] | Sri Lanka and the possibilities of achieving UHC in a poor country | 2019 | Review | Identify factors enabling Sri Lanka to progress toward UHC Presented Sri Lanka’s health-care challenges |

| Erdenee et al.[47] | Mongolian health sector strategic master plan (2006-2015): A foundation for achieving UHC | 2019 | Review | Analyzed changes in the health sector toward achieving UHC based on relevant literature, government documents, and framework analysis Investigated how the basic principles of UHC were incorporated and reflected in Mongolia’s health sector strategic master plan |

| Zhu et al.[33] | Analysis of strategies to attract and retain rural health workers in Cambodia, China, and Vietnam and context influencing their outcomes | 2019 | Qualitative | Described the strategies supporting rural health worker attraction and retention in Cambodia, China, and Viet Nam and explored the context influencing their outcomes |

| Clarke et al.[2] | The private sector and UHC | 2019 | Perspectives | Suggested approaches to managing, and where appropriate, engaging the private sector as part of e?orts to achieve UHC |

| Cowley and Chu[37] | Comparison of private sector hospital involvement for UHC in the Western Pacific Region | 2019 | Commentary | Summarized the growth of private hospitals in China, Viet Nam, and Lao PDR according to some UHC attributes such as quality, accountability, equity, and efficiency Concludes with potential action steps for increasing the contribution of the private hospital sector toward attaining UHC in these three countries |

| Yip et al.[50] | 10 years of health-care reform in China: Progress and gaps in UHC | 2019 | Review | Reviewed progress and gaps in UHC in China |

| Danaei et al.[55] | Iran in transition | 2019 | Review | Presented transition trends and lessons learned from the Islamic Republic of Iran |

| Titoria and Mohandas[44] | A glance on PPP: An opportunity for developing nations to achieve UHC | 2019 | Review | Showed the necessity of PPP and related challenges in India |

| Stewart and Wolvaardt[63] | Hospital management and health policy - A South African perspective | 2019 | Review | Addressed policy evolution and current policy issues that are ended to the need for UHC, hospital management in South Africa |

| Khoonthaweelapphon Woraset[42] | The liberalization of Thailand medical services industry: Case study between Thailand and South Korea | 2019 | Thesis-case study | Focused on the examination of the medical service industry in Thailand and South Korea |

| Asbu et al.[52] | Determinants of hospital efficiency: Insights from the literature | 2020 | Literature Review | Reviewed the literature on hospital efficiency and its determinants |

***Arab countries here refer to Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, Iraq, Yemen, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. WHO=World Health Organization, EMRO=Eastern Mediterranean Region Office of WHO, LMICs=Low-income and middle-income countries, EMR=Eastern Mediterranean Region, Lao PDR=Lao People’s Democratic Republic, PPP=Public-private partnership

Data extraction, synthesis, and analysis

Adopting the narrative synthesis as a systematic and transparent approach,[29] after further familiarization with the data, data coding was undertaken in the following three phases: deduction, induction, and verification. In the deduction phase, the framework method following Gale et al. model was selected as a systematic and flexible approach, particularly in multi-disciplinary research teams where not all members have experience of qualitative data analysis.[30] Accordingly, the retrieved data were coded using the WHO policy framework,[22] knowing that the significance of systematically tracking the progress in attaining UHC was highlighted in the 2013 World Health Report.[31]

For the induction phase, the free code was dedicated to the messages extracted from the records which allow new themes to emerge inductively. The coding project was refined through constant comparative analysis, whereby the coded concepts were certified, modified, unified, and/or added to through several replications of analysis. Throughout this process, a team approach was employed to minimize individual bias associated with multiple analysts involved in coding and interpreting data. In that case, both authors undertook to validate coding decisions and discuss emerging themes. Finally, the data were searched for patterns across the themes, categories, and codes in different settings (rural and urban areas…) and forms of privatization. Findings were synthesized quantitatively (using frequencies) and qualitatively (thematic analysis) using Excel.

Results

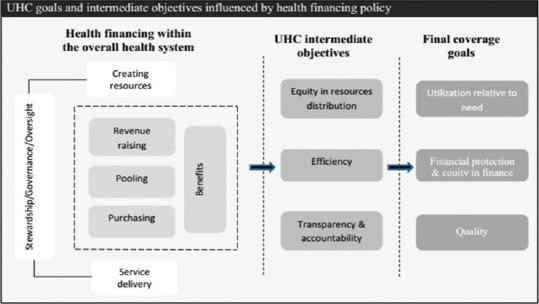

The electronic databases and search engines identified 1420 records. After screening, 28 records [Figure 3] were eligible for inclusion in this review. The findings were classified based on each research question and then were illustrated as tabular or visual representations.

Figure 3.

Included record types and sub-categories related to each type

Bibliometric Research Questions

Record trends and types

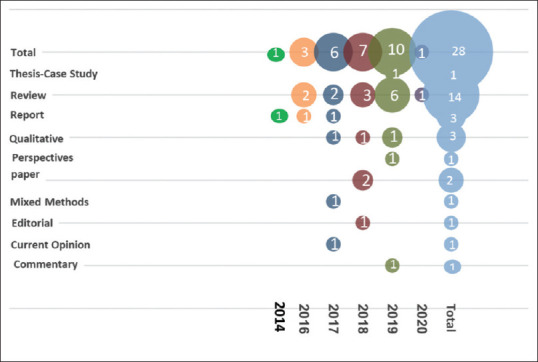

All the included records were in English. Figure 4 demonstrates the chronological trend from 2014 to January 2020 that peaked in 2019 (36%). The trend was progressive until 2019. The classifications of the records according to their contributions [Table 3 and Figure 3] show that half of the record type was review articles in that only one of them[32] was a systematic review.

Figure 4.

Bubble plot of record methods per year

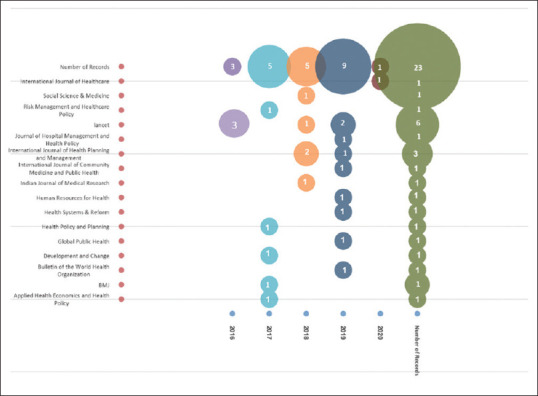

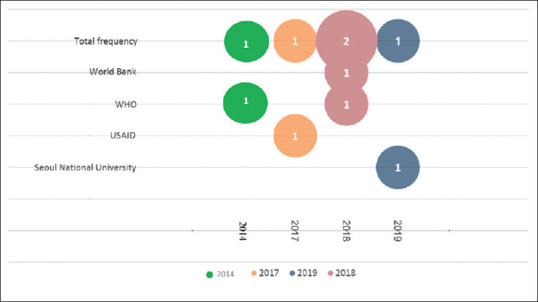

Sources of the records

Figures 5 and 6 show that the 28 selected records were published in 16 journals (82%) and produced by four organizations (18%). It was also revealed that 81% of the journals are indexed in the Web of Science.

Figure 5.

Bubble plot of journals per year

Figure 6.

Bubble plot of corresponding organizations per year

Context Research Questions

The frequent location

The 19 locations identified in the included records are listed in Table 4 with respect to their frequency. It is shown that among all the selected records, India is the most frequent location (12%).

Table 4.

The frequency of the contributed countries

| Location/year | 2014 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | Total frequency of countries | Proportion (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| India | 2 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 12 | ||

| LMICs | 3 | 3 | 9 | ||||

| China | 3 | 3 | 9 | ||||

| Mongolia | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 9 | ||

| South Africa | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |||

| South Korea | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |||

| Thailand | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |||

| Viet Nam | 2 | 2 | 6 | ||||

| EMRO | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |||

| Arab countries | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Bangladesh | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Cambodia | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| The Islamic Republic of Iran | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Nigeria | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Somalia | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Pakistan | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Sri Lanka | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Taiwan | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Lao PDR | 1 | 1 | 3 | ||||

| Total frequency of countries | 1 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 14 | 34 | 100 |

| Number of records | 1 | 3 | 8 | 6 | 8 | 24 | 100 |

| Number of participating countries | 1 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 11 | 19 | 100 |

Population Research Questions

Contribution of the private hospital services in the health system

According to Table 5, the contribution of the DPHS was identified in 31 countries in that 80.6% of them were reported based on the %PHB and 22.6% of them were reported based on the %PHS. In addition, DPHS in 16% of the countries was stated based on the %PH, and in 9.7% of them, it was explicitly stated dominate. China[33] and Sri Lanka with dominant public hospitals[34] were the least contributed and Somalia[35] and South Korea[36,37] with the vast majority of private hospitals were the most contributed. No categories were found based on privatization types.

Table 5.

Contribution of the private hospital services

| Country | %PHB | %PH | Dominant/low/lack of public/private hospital contribution | %PHS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bahrain | 18[10] | |||

| China | 21.7[37] | 56.4[37] | Public is dominant[33] | |

| Djibouti | 22[10] | |||

| Egypt | 25[10] | |||

| India | 49[46] | 62 of inpatient visits,[45] almost 60% of hospitalized patients[46] | ||

| Iraq | 7[10] | |||

| The Islamic Republic of Iran | 13[10] | Almost 16% of inpatient services[55] | ||

| Jordan | 33[10,54] | |||

| Kuwait | 15[10] | |||

| Lao PDR | 7.9[37] | |||

| Lebanon | 82[54] | |||

| Libya | 9[10] | |||

| Mongolia | 20[48,49] | 18% of secondary and tertiary level admissions[49] | ||

| Morocco | 27[10] | |||

| Nigeria | 76 of Nigeria’s secondary medical facilities[61] | |||

| Oman | 6[10] | |||

| Pakistan | 16[10] | |||

| Palestine | 18[10] | |||

| Saudi Arabia | 23[10] | |||

| South Africa | 83[63] | Private is dominant[53] | 90% of admissions[63] | |

| Somalia | Health care is overwhelmingly provided by private providers[35] | |||

| South Korea | >90[36] | Private is dominant[37] | ||

| Sri Lanka | Public is dominant[34] | |||

| Sudan | 9[10] | |||

| Syrian Arab Republic | 28[10] | |||

| Taiwan | 71.60[51] | |||

| Thailand | 19[62] | 11.3% of admissions[62] | ||

| Tunisia | 22[54] | |||

| The United Arab Emirates | 26[10] | |||

| Viet Nam | 5.6[37] | 13.7[37] | 4% of inpatient services[33] | |

| Yemen | 70[54] |

%PHB=Private hospital beds as a percentage of total hospital beds, %PH=Private hospitals as a percentage of total hospitals, %PHS=Share of private hospital services as a percentage of total hospital services market

Concept Research Questions

Roles of delivering private hospital services

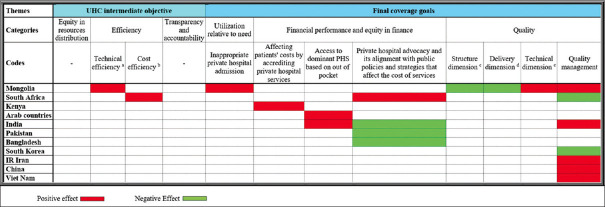

As shown in Figure 7 some categories are defined in following: (a) Technical efficiency is the optimal use of available resources; (b) cost efficiency covers the financial input only. Therefore, input price information is needed to measure it;[38] (c) the quality in terms of structure involves availability and condition of health facilities, defined equipment, material, supplies, and drug; (d) service quality, including responsiveness of staff and often measured by patient satisfaction; (e) technical quality, incorporating the competence of providers and their adherence to clinical guidelines.[39] Regarding equity in resource distribution, no data were available on the contribution of the private hospital costs to total hospitalization costs and indicators, reflecting the improvement or deterioration of justice based on people's needs. There was also no data on the role of DPHS in terms of transparency and accountability. The highest number of the identified roles among 11 countries was observed in records related to Mongolia. Overall, 90% of the roles were concerned with UHC goals, and 65% of the roles were identified as negative effects. In addition, it was seen that Mongolia, India, and South Africa experienced both positive and negative roles.

Figure 7.

Matrix of the roles

Discussion

Identifying and mapping the current literature with respect to the assigned research questions showed several main points that are discussed here briefly.

Bibliometric Research Questions

Record trends and types

The significant increase of the records in 2019, presumably reflects the efforts, interest, and will of the low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) on PS participation in the countries’ health systems in the consequence of the WHO 2018 meeting of Astana, and also the United Nations 2019 high-level meeting on UHC. There was at least one record in all years that have dealt with DPHS in a framework-oriented manner. Although the findings related to DPHS were limited and did not cover all parts of our analysis framework, these findings can confirm the fact that countries should determine the progress of their PHS toward UHC with a framework, not merely monitor PHS via three dimensions of UHC[40,41] and celebrate filling the cube.

Sources of the records

The Lancet which published 26.1% of all the journal articles was the most specialized journal in the field. Furthermore, the findings revealed that both academic and international organizations, respectively, with 20%[42] and 60%[10,36,43] of records contributed in the knowledge synthesis of this field.

Context Research Questions

The frequent location

Coverage of 12% of the overall geographical context by India[17,44,45,46] might indicate that as this country has almost a fifth of the world's population, naturally, a high number of records arise from very diverse health needs based on its cultural, socio-economic, and ethnic diversity.[44] Despite the high frequency in India, a large number of codes in response to research questions regarding population, and concept, came up from Mongolia, due to its three articles[47,48,49] that were exactly concerned with the role of PHS in UHC. The growing body of evidence in recent years might indicate that a considerable tendency in evidence production was initiated about some locations as follows: LMICs, China, and Mongolia.

Population Research Questions

Contribution of the private hospital services in the health system

Mapping the results showed that %PHB was a more common index and can be considered as a rational and conventional index to analyze and interpret the extent of PHS contribution because, as a witness to this claim, when private hospitals in South Korea are dominant and are being a full UHC partner,[37] %PH was reported more than 90%.[36] At the same time, %PH of China was stated as 56.4%,[37] whereas public hospitals in China were reported dominant[33] because China's private hospitals are smaller than public hospitals and most private hospitals cannot compete with the scale of large public tertiary hospitals.[33,50] It should be noted that although in the cases of Lao PDR and Viet Nam %PHB and %PH are reported from the private for-profit sector, this did not affect our classifications of the results because of the reported low %PHS of the Viet Nam.

In addition, %PHB definitely depends on the context of the countries because it was seen that the extent of DPHS contribution encountered different barriers or drivers in many countries. For example, in the EMR, the %PHB in high-income countries and middle-income countries, respectively, ranged from 6% to 22% and 7% to 83%.[43] Similarly, it is adopted allowing both public and private medical service providers of Thailand to operate freely in the market,[42] while in Taiwan,[51] there is no such category that classifies for-profit versus nonprofit in hospital ownership in the government laws. Furthermore, the public–private partnership (PPP) policy in the hospital sector of Viet Nam has led to a surge in the number of hospital beds that reside within or are co-located with public beds but operated on a commercial basis.[50] Therefore, it is important and recommended for future researches identifying and analyzing the causes of the increasing and decreasing DPHS contribution in UHC, and providing policy options regarding their role in achieving UHC.

Concept Research Questions

Roles of delivering private hospital services

Mongolian evidence on the utilization relative to need indicated negative effects on UHC in terms of hospital admission system that does not depend on clinical decision-making alone and plays an important role in this effect.[49] The available evidence about efficiency, does not support the popular belief that private ownership of hospitals results in greater efficiency,[37] Asbu and Masri also found contradictory results even between private for-profit hospitals and private non-for-profit hospitals.[52]

Our findings about financial protection and equity in finance indicated heterogeneity. Although patients’ costs were affected negatively by accrediting private hospital services, dominant PHS as well as private hospital advocacy, and its alignment with public policies and strategies,[32,53,54] the last reason can affect the cost of services positively, according to the successful experiences of Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India.[17]

About quality, although the evidence pointed to the heterogeneous effects of DPHS in achieving this goal, it has positive effects on structure (infrastructure and technology) and delivery (accountability) dimensions of quality.[47] In addition to these dimensions, the data from Iran, China, Vietnam, and India[37,55,56] confirmed the finding that the quality of DPHS in most countries, particularly LMICs, is suboptimal.[20]

It is important to keep in mind two realities. First, the findings demonstrated that the sequence between achieving objectives and achieving subsequent goals. Accordingly, the behaviors caused by the interactions between DPHS and other functions in the health system of both Mongolia and South Africa,[49,53] were affected efficiency negatively. As a result, likewise, the corresponding goals – utilization relative to need, and financial performance and equity in finance – were affected negatively too. Furthermore, nonoptimal use of available resources that illustrated inefficiency in Mongolia, consequently affected the quality positively in terms of the structure and delivery dimensions.

Because improvement in health-care delivery requires a deliberate focus on the quality of health services, which involves providing effective, safe, people-centered care that is timely, equitable, integrated, and efficient,[20] the continuous chain of effects observed in Mongolia confirms its negative quality management caused by previous objectives and quality subcategories. However, the evidence about the positive effect in terms of quality in South Africa is scarce and needs further researches in future.

Second, in conjunction with the relationship between the contribution of PHS to UHC and its roles, evidence indicated some heterogeneous findings such that South Korea[37] and Sri Lanka,[34] respectively, with dominant private and public hospitals were successful countries in approaching UHC, although Sri Lanka is no longer providing good health at a low cost.[34] Probably, the role is also dependent on countries’ policy implementation and the emerging behaviors related to DPHS. Hence, national policy analysis aimed at evidence-based policymaking is suggested.

The systematic scrutinization of the role of the DPHS exclusively in UHC through related WHO framework is the strength of this study that makes it possible to provide clear and tangible knowledge for the audience. Furthermore, this review was subjected to several limitations, including, (a) this study started in 2018 and after its update in early 2020, the time spent on its preparation and publishing lasted nearly half a year. Therefore, the records related to after the last update were not included because we had already reached the results and prepared the logical, diagrammatic, and tabular forms; and (b) the quality assessment of the included records was not conducted because of two reasons: (1) unlike the systematic reviews, scoping reviews provide an overview of the existing evidence, regardless of quality,[23,57] and (2) we did not want to miss any efforts in the context of this review.

Conclusions and Implications for Research and Practice

Although evidence has revealed inconsistency in the identified roles that inherently depend on the individual country's context, a continuous chain of positive or negative effects in objectives and goals was observed. This can be a noteworthy lesson to address the audiences such as international and national-level or academic and professional stakeholders, health policy and decision makers, legislators, or communities’ representatives because ignoring the role of private hospitals in national efforts toward UHC is not a rational option, rather now, precisely the time is to change DPHS policies and strategies to help world transformation toward a healthier world.

Following the international targeted meetings in the context of UHC which had been held in recent years, there is room for improvement of the available evidence to make informed policies in the UHC movement. Hence, given the observed knowledge gaps about roles (in terms of “equity in resource distribution”, “transparency and accountability”), causes of the increasing and decreasing contribution of the DPHS, and its behaviors, also regarding the lack of any comparative classifications of the identified roles in conjunction with the privatization types and circumstance of delivery, these areas are recommended as prioritized research agendas to strengthen the evidence-based policymaking in the future.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgment

Sincere thanks to Hamid Ravaghi, the Associate Professor of Health Policy and Management in Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, and the regional advisor for hospital care and management in WHO/EMRO because the topic of this review was adapted through the health policy seminar – a course in the doctoral program of health policy held by him.

We would like to thank Daniel Molinuevo, one of the research managers at the Social Policies Unit of European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions (Eurofound) for notifying us about the publication of a report in future and allowing us to contact Florien M. Kruse, one of the co-authors of the Eurofound report on hospital services, who continues to work in this area, and thanks to Florien M. Kruse, Ph. D. Candidate on IQ healthcare at Radboud University Medical Centre (Radboudumc), The Netherlands, for some technical guidance in the forward-searching step.

We are grateful to Joseph Kutzin, coordinator in the Health Financing Policy Department of the WHO, for helping us to find some inaccessible references in the backward-searching step, and also thanks to Sajad Delavari, the Assistant Professor of Health Policy, Human Resources Research Center, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, Iran, for the constructive comment he provided to the final draft of this review.63

References

- 1.Frenk J, Gómez-Dantés O. Health systems in Latin America: The search for universal health coverage. Arch Med Res. 2018;49:79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.arcmed.2018.06.002. doi:10.1016/j.arcmed.2018.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clarke D, Doerr S, Hunter M, Schmets G, Soucat A, Paviza A. The private sector and universal health coverage. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97:434–5. doi: 10.2471/BLT.18.225540. doi:10.2471/blt.18.225540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Elders Foundation. Universal Health Coverage: Position paper. 2019. [Last accessed on 2019 September 28]. Available from: https://theelders.org/sites/default/files/final-uhc-position-paper-for-web.pdf .

- 4.Russo G. The role of the private sector in health services: Lessons for ASEAN. Asean Econ Bull. 1994;11(2):190–211. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Awoke MA, Negin J, Moller J, Farell P, Yawson AE, Biritwum RB, et al. Predictors of public and private healthcare utilization and associated health system responsiveness among older adults in Ghana. Glob Health Action. 2017;10:1301723. doi: 10.1080/16549716.2017.1301723. doi:10.1080/16549716.2017.1301723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization. The Private Sector, Universal Health Coverage and Primary Health Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Last accessed on 2019 Oct 20]. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/iris/restricted/handle/10665/312248 . [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costanza R, Fioramonti L, Kubiszewski I. The UN Sustainable Development Goals and the dynamics of well-being. Front Ecol Environ. 2016;14:59. doi.org/10.1002/fee.1231. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackintosh M, Channon A, Karan A, Selvaraj S, Cavagnero E, Zhao H. What is the private sector? Understanding private provision in the health systems of low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet. 2016;388:596–605. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00342-1. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00342-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bishai D, Sachathep K. The role of the private sector in health systems. Health Policy Plan. 2015;30(Suppl 1):i1. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czv004. doi:10.1093/heapol/czv004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Analysis of the Private Health Sector in Countries of the Eastern Mediterranean: Exploring Unfamiliar Territory. Cairo: World Health Organization. Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tourani S, Malmoon Z, Zaboli R, Jafari M, Nemati A. Training needs assessment of nursing managers for achieving university health coverage. J Educ Health Promot. 2020;9:139. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_114_20. doi:10.4103/jehp.jehp_114_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weldemariam T, Bayray A. Role of private health sector in provision of quality health service in developing countries: Does the private health sector contribute to achieve health-related MDGs? A systematic review. Res Rev. 2015;5:7–13. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Green A. The role of non-governmental organizations and the private sector in the provision of health care in developing countries. Int J Health Plann Manage. 1987;2:37–58. doi:10.1002/hpm.4740020106. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanson K, Berman P. Private health care provision in developing countries: A preliminary analysis of levels and composition. Health Policy Plan. 1998;13:195–211. doi: 10.1093/heapol/13.3.195. 10.1093/heapol/13.3.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoong J, Burger N, Spreng C, Sood N. Private sector participation and health system performance in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zwi AB, Brugha R, Smith E. Private health care in developing countries: If it is to work, it must start from what users need. BMJ. 2001;323:463–4. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7311.463. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7311.463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zaidi S, Saligram P, Ahmed S, Sonderp E, Sheikh K. Expanding access to healthcare in South Asia. BMJ. 2017;357:j1645. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j1645. doi:10.1136/bmj.j1645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zaidi S, Riaz A, Taver A, Mukhi A, Khan LA. Role and Contribution of Private Sector in Moving Towards Universal Health Coverage in the Eastern Mediterranean Region. 2012. [Last accessed on 2018 Aug 20]. Available from: http://ecommons.aku.edu/pakistan_fs_mc_chs_chs/193 .

- 19.Kutzin J. Health financing for universal coverage and health system performance: Concepts and implications for policy. Bull World Health Organ. 2013;91:602–11. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.113985. doi:10.2471/BLT.12.113985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Health Organization, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, and the World Bank. Delivering Quality Health Services: A Global Imperative for Universal Health Coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Savigny D, Adam T, editors. World Health Organization; 2009. Systems Thinking for Health Systems Strengthening: Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Policy Framework. World Health Organization Website. [Last accessed on 2019 May 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/health_financing/policy-framework/en/

- 23.Aromataris EM. Joanna Briggs Institute; 2017. [Last accessed on 2018 Dec 20]. Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer's Manual. Available from: https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O'Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850. doi:10.7326/M18-0850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kastner M, Tricco AC, Soobiah C, Lillie E, Perrier L, Horsley T, et al. What is the most appropriate knowledge synthesis method to conduct a review? Protocol for a scoping review. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2012;12:114. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-114. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-12-114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Antman EM, Lau J, Kupelnick B, Mosteller F, Chalmers TC. A comparison of results of meta-analyses of randomized control trials and recommendations of clinical experts. Treatments for myocardial infarction. JAMA. 1992;268:240–8. doi:10.1001/jama.1992.03490020088036. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peters MD, Godfrey CM, Khalil H, McInerney P, Parker D, Soares CB. Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13:141–6. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050. doi: 10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munn Z, Peters MD, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mays N, Pope C, Popay J. Systematically reviewing qualitative and quantitative evidence to inform management and policy-making in the health field. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(Suppl 1):6–20. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308576. doi:10.1258/1355819054308576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gale NK, Heath G, Cameron E, Rashid S, Redwood S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2013;13:117. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-13-117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2013: Research for Universal Health Coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Montagu D, Goodman C. Prohibit, constrain, encourage, or purchase: How should we engage with the private health-care sector? Lancet. 2016;388:613–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30242-2. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)30242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu A, Tang S, Thu NTH, Supheap L, Liu X. Analysis of strategies to attract and retain rural health workers in Cambodia, China, and Vietnam and context influencing their outcomes. Hum Resour Health. 2019;17:2. doi: 10.1186/s12960-018-0340-6. doi:10.1186/s12960-018-0340-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chapman AR, Dharmaratne SD. Sri Lanka and the possibilities of achieving universal health coverage in a poor country. Glob Public Health. 2019;14:271–83. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2018.1501080. doi:10.1080/17441692.2018.1501080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gele AA, Ahmed MY, Kour P, Moallim SA, Salad AM, Kumar B. Beneficiaries of conflict: A qualitative study of people's trust in the private health care system in Mogadishu, Somalia. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2017;10:127–35. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S136170. doi:10.2147/rmhp.s136170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kwon S. Universal Health Care Coverage Series No. 33. Washington, DC: World Bank Group; 2018. Advancing Universal Health Coverage: What Developing Countries Can Learn from the Korean Experience? [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cowley P, Chu A. Comparison of private sector hospital involvement for UHC in the western pacific region. Health Syst Reform. 2019;5:59–65. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2018.1545511. doi:10.1080/23288604.2018.1545511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Conditions. Delivering Hospital Services: A Greater Role for the Private Sector? Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Berendes S, Heywood P, Oliver S, Garner P. Quality of private and public ambulatory health care in low and middle income countries: Systematic review of comparative studies. PLoS Med. 2011;8:e1000433. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000433. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2010-Health Systems Financing: The Path to Universal Coverage. Geneva: 2010. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 20]. Available from: http://www.who.int/whr/en/index.html . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Evans DB, Saksena P, Elovainio R, Boerma T. Measuring Progress Towards Universal Coverage. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Khoonthaweelapphon Woraset. The Liberalization of Thailand Medical Services Industry-Case Study between Thailand and South Korea, Master's thesis of International Commerce. Graduate School of International Studies, Seoul National University. 2019. [Last accessed on 2019 Oct 11]. Available from: http://hdl.handle.net/10371/150912 .

- 43.World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Eastern Mediterranean. Regional Committee for the Eastern Mediterranean Sixty-fifth session-Provisional Agenda Item 4(e): Private Sector Engagement for Advancing Universal Health Coverage. 2018. [Last accessed on 2019 Nov 19]. Available from: http://applications.emro.who.int/docs/RC_Technical_Papers_2018_8_20546_EN.pdf .

- 44.Titoria R, Mohandas A. A glance on public private partnership: An opportunity for developing nations to achieve universal health coverage. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2019;6:1353–7. doi:10.18203/2394-6040.ijcmph20190640. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zodpey S, Farooqui HH. Universal health coverage in India: Progress achieved & the way forward. Indian J Med Res. 2018;147:327–9. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_616_18. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_616_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maurya D, Virani A, Rajasulochana S. Horses for courses: Moving India towards universal health coverage through targeted policy design. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. 2017;15:733–44. doi: 10.1007/s40258-017-0358-2. doi:10.1007/s40258-017-0358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Erdenee O, Narula IS, Yamazaki C, Kameo S, Koyama H. Mongolian health sector strategic master plan (2006-2015): A foundation for achieving universal health coverage. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2019;34:e314–26. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2651. doi:10.1002/hpm.2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tsevelvaanchig U, Narula IS, Gouda H, Hill PS. Regulating the for-profit private healthcare providers towards universal health coverage: A qualitative study of legal and organizational framework in Mongolia. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2018;33:185–201. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2417. doi:10.1002/hpm.2417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tsevelvaanchig U, Gouda H, Baker P, Hill PS. Role of emerging private hospitals in a post-Soviet mixed health system: A mixed methods comparative study of private and public hospital inpatient care in Mongolia. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32:476–86. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czw157. doi:10.1093/heapol/czw157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yip W, Fu H, Chen AT, Zhai T, Jian W, Xu R, et al. 10 years of health-care reform in China: Progress and gaps in Universal Health Coverage. Lancet. 2019;394:1192–204. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32136-1. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32136-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu JR, Chiang TL. Developing an adequate supply of health services: Taiwan's path to Universal Health Coverage. Soc Sci Med. 2018;198:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.017. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Asbu EZ, Masri MD, Al Naboulsi M. Determinants of hospital efficiency: A literature review? International Journal of Healthcare, 2020;6(2):44–53. doi: 10.5430/ijh.v6n2p44. doi:10.5430/ijh.v6n2p44. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sean CN, Sparks S, and Nelson G Organizing the Private Sector to Support Universal Health Coverage Goals. Sustaining Health Outcomes through the Private Sector Plus Project. Bethesda, MD: Abt Associates; 2017. [Last accessed on 2019 Nov 19]. Available from: https://www.shopsplusproject.org/resource-center/organizing-private-sector-support-universal-health-coverage-goals . [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alami R. Health financing systems, health equity and universal health coverage in Arab countries. Dev Change. 2017;48:146–79. doi:10.1111/dech.12290. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Danaei G, Farzadfar F, Kelishadi R, Rashidian A, Rouhani OM, Ahmadnia S, et al. Iran in transition. Lancet. 2019;393:1984–2005. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33197-0. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33197-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McPake B, Hanson K. Managing the public-private mix to achieve universal health coverage. Lancet. 2016;388:622–30. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)00344-5. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)00344-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Doosty F, Maleki MR, Yarmohammadian MH. An investigation on workload indicator of staffing need: A scoping review. J Edu Health Promot. 2019;8(1):22. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_220_18. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_220_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.World Health Organization. Handbook for National Quality Policy and Strategy: A Practical Approach for Developing Policy and Strategy to Improve Quality of Care. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pearson M, Colombo F, Murakami Y, James C Universal Health Coverage and Health Outcomes. Final Report for the G7 Health Ministerial Meeting, Paris. 2016. [Last accessed on 2019 Nov 19]. Available from: https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Universal-Health-Coverage-and-Health-Outcomes-OECD-G7-Health-Ministerial-2016.pdf .

- 60.United Nations. World Economic Situation and Prospects 2020. New York: United Nations; 2020. [Last accessed on 2019 Nov 19]. Available from: https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/wesp2020_en.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 61.Makinde OA, Sule A, Ayankogbe O, Boone D. Distribution of health facilities in Nigeria: Implications and options for Universal Health Coverage. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2018;33:e1179–92. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2603. doi:10.1002/hpm.2603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tangcharoensathien V, Witthayapipopsakul W, Panichkriangkrai W, Patcharanarumol W, Mills A. Health systems development in Thailand: A solid platform for successful implementation of universal health coverage. Lancet. 2018;391:1205, 23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30198-3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30198-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stewart J, Wolvaardt G. Hospital management and health policy – A South African perspective. J Hosp Manag Health Policy. 2019;3(14) doi: 10.21037/jhmhp. 2019.06.01. [Google Scholar]