Abstract

Background:

Health disparities have become apparent since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. When observing racial discrimination in healthcare, self-reported incidences, and perceptions among minority groups in the United States suggest that, the most socioeconomically underrepresented groups will suffer disproportionately in COVID-19 due to synergistic mechanisms. This study reports racially-stratified data regarding the experiences and impacts of different groups availing the healthcare system to identify disparities in outcomes of minority and majority groups in the United States.

Methods:

Studies were identified utilizing PubMed, Embase, CINAHL Plus, and PsycINFO search engines without date and language restrictions. The following keywords were used: Healthcare, raci*, ethnic*, discriminant, hosti*, harass*, insur*, education, income, psychiat*, COVID-19, incidence, mortality, mechanical ventilation. Statistical analysis was conducted in Review Manager (RevMan V.5.4). Unadjusted Odds Ratios, P-values, and 95% confidence intervals were presented.

Results:

Discrimination in the United States is evident among racial groups regarding medical care portraying mental risk behaviors as having serious outcomes in the health of minority groups. The perceived health inequity had a low association to the majority group as compared to the minority group (OR = 0.41; 95% CI = 0.22 to 0.78; P = .007), and the association of mental health problems to the Caucasian-American majority group was low (OR = 0.51; 95% CI = 0.45 to 0.58; P < .001).

Conclusion:

As the pandemic continues into its next stage, efforts should be taken to address the gaps in clinical training and education, and medical practice to avoid the recurring patterns of racial health disparities that become especially prominent in community health emergencies. A standardized tool to assess racial discrimination and inequity will potentially improve pandemic healthcare delivery.

Keywords: race, ethnicity, health disparities, health inequity, discrimination, COVID-19

Introduction

The values, beliefs, and resource allocations within a society are cultivated and nurtured by the dynamic liaison of systems that make up our society, including the justice, healthcare, educational, and political systems. When these systems reinforce discriminatory beliefs and values, it is known as structural racism.1 In 2020, around 40% of the United States population is considered a minority. This group encompasses approximately 17% Hispanics, 12% African-Americans, 5% Asian Americans, while Native Hawaiian, Indian Alaskan, Pacific Islanders, and other racial/ethnic groups comprise the rest.2 In the past, there have been instances like the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis, conducted amongst the African-American men in 1932, that sowed the seeds of distrust. Involuntary federally-funded sterilization performed on minority groups in California until 1979 further compounded this distrust and stirred anger in these communities.3 A report titled “Health, United States, 1983” documents these disparities experienced by African-American communities and other minority Americans.4 This paper aims to shed light on the health disparities during pandemic management while highlighting the lessons learned from COVID-19.

In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) declared a global COVID-19 pandemic, and the world was submerged into a social and economic lockdown. Under these conditions, there have been flare-ups of the Gordian knots of cultural incompetence in social structure and racial discrimination. The shortcomings are reflected by the disproportionately higher incidence of COVID-19 and deaths due to COVID-19 among minority groups5-8 substandard sexual and reproductive health amongst African-American women,9 and poor mental health outcomes in minorities.10 Delineating such disparities and raising awareness enables leaders to come together and address these issues. Fiscella et al10 suggest 5 principle solutions to address disparities in healthcare. In 2003, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) committee came up with a series of reports to discuss these issues and provide plausible, workable solutions.11 Bailey et al1 elaborated that focusing on this structural racism, especially in the healthcare setting, is essential for health equity and social development. Another paper detailed the relevance of cultural competency training for the healthcare workforce, a keystone to bridging the current gaps in healthcare delivery.12

Our study investigates how perceived racial discrimination in minority groups in America correlates with increased risk of severe COVID-19 infection and increased acute and chronic sequelae. This meta-analysis reports racially-stratified data regarding the experiences and impacts of different groups availing the healthcare system and extracts the racial burden of COVID-19 to identify disparities in outcomes of minority and majority groups in the United States.

Methods

This meta-analysis adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Studies were screened utilizing PubMed, Embase, CINAHL Plus, and PsycINFO search engines without date and language restrictions. The search included studies published until October 8, 2020. The primary outcome was to report racially-stratified data regarding experiences and impacts of different racial/ethnic groups in the United States. The secondary outcome was to extrapolate the implications of existing disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic for minority groups in the United States. The search terms are enlisted in Table 1.

Table 1.

Search Terms.

| Healthcare, raci*, ethnic*, discriminant, hosti*, harass*, insur*, education, income, psychiat*, COVID-19, incidence, mortality, mechanical ventilation. |

Two early-to-mid level researchers (AS and ZS) screened eligible articles that met the inclusion criteria of the analysis by addressing the listed outcomes, with queries resolved through active discussion. Data was tabulated as “sampling procedure, the instrument used, internal validity, timeframe-type of racism exposure, racial/ethnic group, income, educational attainment, health insurance status, and mental health indicator-outcome perceived health inequity” [Supplemental Table 1].

Statistical analysis was conducted in Review Manager (RevMan V.5.4, UK). Unadjusted Odds Ratios (ORs), P-values, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were presented for primary and secondary outcomes. The risk of bias was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), with high quality methodological studies included in the final analysis.

Results

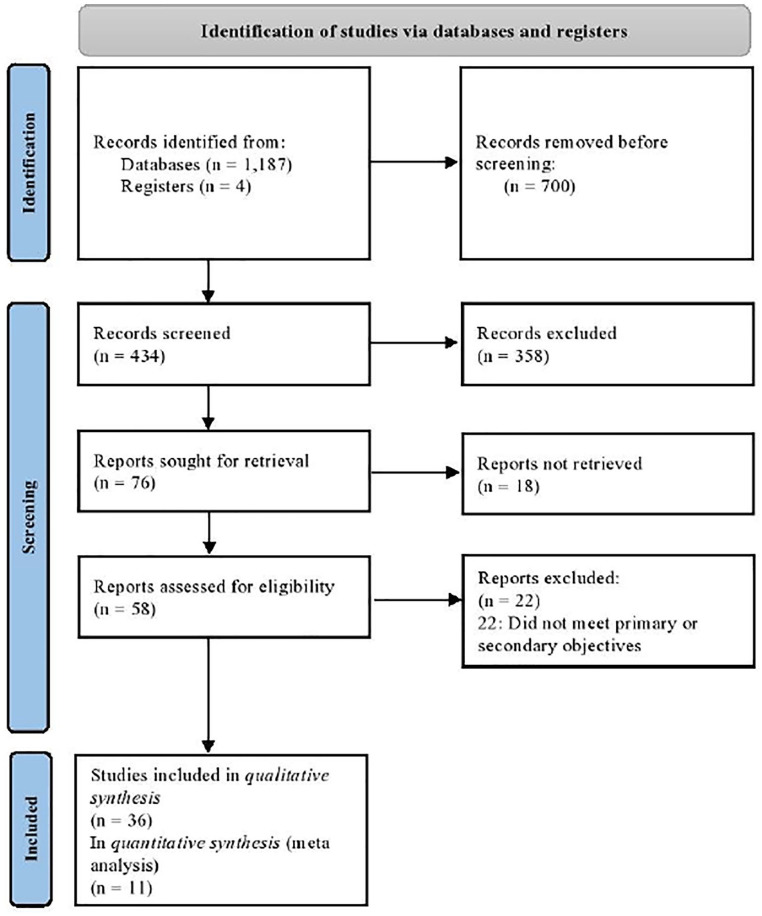

Of the 1191 records identified, a total of 434 were screened, with 58 full-text articles assessed for eligibility. In the qualitative synthesis, 36 records were included, with 11 records sub-analyzed in the meta-analysis (Figure 1). A meta-analysis of 808 851 participants was conducted with 664 399 (82.1%) participants in the majority group and 144 452 (17.9%) in the minority group. All studies (100%) were led in the United States, and 19 (51.4%) studies employed a representative sampling procedure. The characteristics of included studies in the qualitative synthesis are listed in [Supplemental Table 1].

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart.

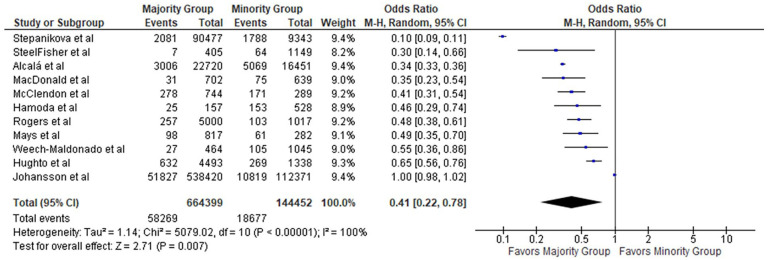

Racial discrimination among different groups in the United States was evident, with minority groups (African-American, American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian American, Hispanic/Latino, Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, Not Specified) portraying significant mental health problems as opposed to the majority group [Supplemental Table 1]. The perceived health inequity had a low association with the majority group compared to the minority group (Odds Ratio = 0.41; 95% confidence interval = 0.22 to 0.78; P = .007) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of perceived health inequity in the majority and minority groups.

The majority group consists of Caucasian-Americans only. The minority group includes African-Americans, American Indians/Alaska Natives, Asian Americans, Hispanics/Latinos, Native Hawaiians/Other Pacific Islanders, or Not Specified.

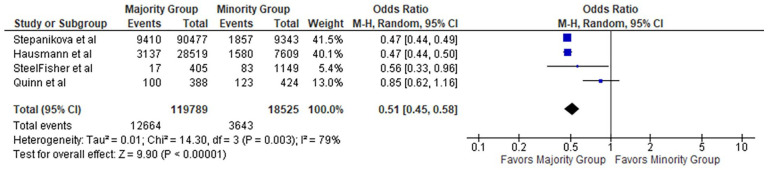

The association of mental health problems to the Caucasian-Americans was determined (Odds Ratio = 0.51; 95% confidence interval = 0.45 to 0.58; P < .001) (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of mental health problems in the majority and minority groups.

Additionally, positive health behaviors had a stronger association with the majority Caucasian-Americans as opposed to the minority group (Odds Ratio = 1.64; 95% confidence interval = 1.55 to 1.74; P < .001) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Forest plot of positive health behaviors in the majority and minority groups.

Discussion

Direct and indirect racism in healthcare is common across a highly heterogeneous sample of studies, and it is impactful in delivering services during and post the pandemic. This is an important underlying mechanism of both direct (patient-related) and indirect (mental health problems, chronic illness care) disparities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings support the need to address disparities in pandemic crisis management while understanding and promoting racial diversity in healthcare settings. Notably, racial demographic data is still scarce, with significant efforts required to report infection and mortality rates, self-perceived inequities, and mental health outcomes.

An Overview of Existent Health Disparities in the National Healthcare System

Existing health disparities have been brought to the forefront with the start of the pandemic. They have only been amplified, as demonstrated by the differential incidence and mortality rates of COVID-19 patients. When observing racial discrimination in healthcare, self-reported incidences and perceptions among minority groups in the United States suggest that the most socioeconomically underrepresented groups will suffer disproportionately in COVID-19 due to synergistic mechanisms. Studies regarding distrust of the system have also shown discrepant data between races.6,13 Certain racial/ethnic groups are affected at population levels due to biological and social factors that influence healthcare access, such as discrepancies in unemployment, income level, insurance, education, and cultural or language barriers.14 A clear example is the gap in life expectancy between races shown by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). However, it has been improving from a gap of 7.6 years in 1970 to 3.8 years in 2010. The gap that exists is worrying and raises further questions regarding the quality of care, morbidity, mortality, and quality of life.15

U.S. counties with a majority of African-American residents have 3 times more infection rates and approximately 6 times higher mortality rates than counties with a majority of Caucasian-Americans.16 Age and population-adjusted deaths in the African-American people were 2 times more than the Caucasian-American population.17 Towns that were composed of minority (African-American and Hispanic) populations were found to have unfavorable outcomes.8

The Syndemic theory identifies that minority groups such as African-American or Native American populations are at increased risk of worse COVID-19 outcomes due to underlying health inequities demonstrated by a higher burden of comorbidities in the African-American community.18 One example is a study showing that Caucasian-Americans received more testing than other minority groups, specifically Hispanic and African-American subjects. However, the latter groups had an elevated prevalence for being optimistic when the final test results were compared.19

COVID-19 Related Inequities and Link to Chronic Medical Conditions

Our meta-analysis found that the majority group (Caucasian-Americans only) had a significantly lower association to perceived health inequities as compared to the minority group (African-Americans, American Indians/Alaska Natives, Asian Americans, Hispanics/Latinos, Native Hawaiians/Other Pacific Islanders, or Not Specified), with an Odds Ratio (OR) of 0.41 (P = .007). Ultimately, racial health inequities are associated with significant economic losses in the health care system, with some estimates stating around $230 billion in reductions possibly due to illness-related lost productivity and/or premature deaths.20 Reducing health inequities will only be possible with a diverse healthcare task force to address the patients’ social risk factors and eliminate barriers in healthcare access and utilization.

Recent data shows that the life expectancy of African Americans has increased, with a 25% reduction in mortality over 17 years, especially in older adults (65 years or older).21 Despite recent improvements in life expectancy in African Americans, it is found that younger African Americans are prone to certain diseases earlier in life leading to premature death, and long-term illness, which may remain asymptomatic. However, health inequities due to financial and social problems are more frequently seen in minority groups than in the Caucasian-American population. The statement may be corroborated by a report, which finds that African American adults often do not visit doctors due to financial issues, suggesting socioeconomic barriers contributing to health disparities.21

In the United States, the African-American population reports a higher incidence of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, HIV, obesity, and asthma than the Caucasian-American population.22 Hence, a higher incidence of COVID-19-associated morbidity and mortality in African-American communities are per the previously seen trends.8,22,23 To assess the principle cause of COVID-19-related inequities, and further formulate a causal link with the findings of our meta-analysis, it is necessary to analyze the underlying comorbid conditions and socio-economic conditions to unfavorable outcomes.24 Further steps include shedding light to the discrepancies in COVID-19 hospitalization and death rates by race and ethnicity in the United States, and across the globe.25,26

Vaccination Decisions and Way Forward Amid Racial/Social Disparities

Vaccination rates have a direct effect on the achievable herd immunity. For this reason, understanding, and addressing vaccine hesitancy in any population is crucial during the pandemic pandemic. Quinn et al27 noted in their 3 Cs (complacency, Convenience, and Confidence) study that racial differences in vaccination rates were due to trust, confidence and barriers in cost. In their study, Freimuth et al28 observed that the role of racial differences in vaccine decisions include poverty, lack of insurance status, psychosocial predictors such as demographics, barriers to access, vaccine attitudes, and explored lack of trust as well. While mapping on geographic information systems, Hall et al29 also observed that there were extensive disparities amongst African Americans, Hispanics, rural communities and those in the low socioeconomic strata for inactivated influenza vaccine (IIV). Educational and appointment reminder interventions may improve vaccine uptake amongst the minority in the United States.30 In another study, the authors detail the importance of one-on one discussion to build trust, create awareness, and increase uptake of vaccination amongst the minority group.31 It is important to emphasize the central role policies and vaccine rationing play in ensuring that disadvantaged communities are given precedence during country-wide vaccination measures.

The Need for a Robust and Guiding Framework on Health Equity

The pandemic has highlighted the deep-rooted systemic inequities and health disparities that many minority groups face, as demonstrated by the increased morbidity and mortality burden from COVID-19.32 These gaps must be addressed and reduced to mitigate the potentially destructive long-term effects due to overwhelming the fragile systems of these communities.33-35 A robust and guiding framework focusing on health equity is crucial upon entering different phases of the COVID-19 pandemic—as progress is made toward finding and administering a definitive preventative cure across populations. Inspiration for such a framework can be drawn from government initiatives such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Strategies for Reducing Health Disparities Report 2016, the Healthy People 2030 Initiative, and the CDC COVID-19 Response Health Equity Strategy.34-36 In these reports, the focus is on specific community engagement (such as racial minorities, rural areas, those with disabilities, and homeless populations) and extending additional resources to these areas while implementing policies and systems to ensure equitable care. Recommendations for healthcare workers include the following:

Utilize verified programs to decrease inequalities and help develop equal opportunities for health,

Collaborate with organizations to create financial and social conditions that improve the standard of health beginning from childhood,

Connect more people to healthcare professionals so that regular health checkup is increased,

Train healthcare providers in mitigating any ethnic/racial differences to increase trust and interaction among patients and healthcare workers.

In line with our results, we found a strong association of positive health behaviors to Caucasian Americans as opposed to the delineated minority groups with an Odds Ratio (OR) of 1.64 (P < .001). Committing to addressing vital underlying mental and physical conditions (indirect) and patient-care (direct) disparities in response to COVID-19 is incredibly important. These actions will further necessary progress toward the fundamental concept of health equity.

Limitations

Our study had certain limitations during interpreting the results due to the heterogeneity of included studies and a diversity set of instrumentations used to report these findings. A comparison of results could not be made for all minor ethnic and racial group due to varied definitions of minority groups in the studies. While certain minority groups may have a higher impact in terms of disparities, these findings were not be possible to demonstrate. The sampling procedure and meta-analysis had weaknesses too. While it may be evident that race and ethnicity are complex constructs, we have conducted an in-depth analysis of numerous studies and connected these outcomes to quantitatively tested biological and mental health outcomes. However, not all variables could be statistically compared, thus leading to a qualitative synthesis of non-quantifiable outcomes [Supplemental Table 1].

Conclusion

Underlying racial disparities place minority groups at greater risk of severe COVID-19 infection. Better explained as acute-on-chronic sequelae, COVID-19 has demarcated the long-standing health disparities faced by various minority groups in America. Within the context of utilizing public health resources, healthcare professionals should make informed efforts to target these minority groups, including testing, contract tracing, data surveillance, and vaccine administration. Sustainable mechanisms to support vulnerable minority populations require long-term, systemic solutions such as investment in community health services and promotion of cultural competence and awareness in hospital settings to address the high rates of perceived discrimination among minority groups in these settings. In addition, a standardized tool to assess racial discrimination in scholarly publishing will potentially improve healthcare delivery. As the pandemic continues into its next stage, efforts should be taken to address the gaps in clinical training and education, and medical practice to avoid the recurring patterns of racial health disparities that become especially prominent in community health emergencies.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpc-10.1177_21501327211018354 for Understanding and Promoting Racial Diversity in Healthcare Settings to Address Disparities in Pandemic Crisis Management by Azza Sarfraz, Zouina Sarfraz, Alanna Barrios, Kuchalambal Agadi, Sindhu Thevuthasan, Krunal Pandav, Manish KC, Muzna Sarfraz, Pedram Rad and George Michel in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Azza Sarfraz  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8206-5745

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8206-5745

Zouina Sarfraz  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5132-7455

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5132-7455

Alanna Barrios  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8332-8682

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8332-8682

Krunal Pandav  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5451-7115

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5451-7115

Manish KC  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1693-6068

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1693-6068

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389:1453-1463. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30569-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. The Office of Minority Health. Black/African American- The Office of Minority Health. 2021. https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=3&lvlid=61

- 3. Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Knowledge of the Tuskegee study and its impact on the willingness to participate in medical research studies. J Natl Med Assoc. 2000;92:563-572. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. (U.S.) NC for HS, Research. NC for HS. Health, United States. 1983; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138511. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seoane L. Hospitalization and mortality among black patients and white patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2534-2543. doi: 10.1056/nejmsa2011686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Millett GA, Jones AT, Benkeser D, et al. Assessing differential impacts of COVID-19 on black communities. Ann Epidemiol. 2020;47:37-44 doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wadhera RK, Wadhera P, Gaba P, et al. Variation in COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths across New York City Boroughs. JAMA. 2020;323:2192-2195. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.7197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Prather C, Fuller TR, Jeffries WL, et al. Racism, African American women, and their sexual and reproductive health: a review of historical and contemporary evidence and implications for health equity. Heal Equity. 2018;2:249-259. doi: 10.1089/heq.2017.0045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fiscella K, Franks P, Gold MR, Clancy CM. Inequality in quality: addressing socioeconomic, racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Am Med Assoc. 2000;283:2579-2584. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gibbons MC. A historical overview of health disparities and the potential of eHealth solutions. J Med Internet Res. 2005;7:e50. doi: 10.2196/jmir.7.5.e50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jongen C, McCalman J, Bainbridge R. Health workforce cultural competency interventions: a systematic scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18:232 doi: 10.1186/s12913-018-3001-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Alderwick H, Gottlieb LM. Meanings and misunderstandings: a social determinants of health lexicon for health care systems. Milbank Q. 2019;97:407-419. doi: 10.1111/1468-0009.12390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Szczepura A. Access to health care for ethnic minority populations. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:141-147. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2004.026237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kochanek KD, Arias E, Anderson RN. How did cause of death contribute to racial differences in life expectancy in the United States in 2010? NCHS Data Brief. 2013;125:1-8. doi: 10.13016/3g98-57kb [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. COVID-19 Racial Data Transparency. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Health N. covid-19 deaths by race-ethnicity. 2020. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/imm/covid-19-deaths-race-ethnicity-04082020-1.pdf

- 18. WHO. Draft Landscape and Tracker of COVID-19 Candidate Vaccines. WHO; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rentsch CT, Kidwai-Khan F, Tate JP, et al. Covid-19 by race and ethnicity: a national cohort study of 6 million United States Veterans. medRxiv. 2020. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.12.20099135 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Laveist T, Gaskin D, Richard P. Estimating the economic burden of racial health inequalities in the United States. Int J Heal Serv. 2011;41:231-238. doi: 10.2190/HS.41.2.c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Centers for Diseas Control and Prevention. African American Health Creating Equal Opportunities for Health Problem: Young African Americans are Living with Diseases more Common at Older Ages. CDC Vital Signs; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 22. National Center for Health Statistics (US). Health, United States, 2015: With Special Feature on Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Hyattsv Natl Cent Heal Stat; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Pan D, Sze S, Minhas JS, et al. The impact of ethnicity on clinical outcomes in COVID-19: a systematic review. EClinical Medicine. Published online June 03, 2020. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chowkwanyun M, Reed AL. Racial health disparities and Covid-19 — caution and context. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:201-203. doi: 10.1056/nejmp2012910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed Coronavirus Disease 2019 — COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1–30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:458-464. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Owen WF, Carmona R, Pomeroy C. Failing another national stress test on health disparities. JAMA. 2020;323:1905-1906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Quinn S, Jamison A, Musa D, Hilyard K, Freimuth V. Exploring the continuum of vaccine hesitancy between African American and white adults: results of a qualitative study. PLoS Curr. 2016;8:17-18. doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.3e4a5ea39d8620494e2a2c874a3c4201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Freimuth VS, Jamison AM, An J, Hancock GR, Quinn SC. Determinants of trust in the flu vaccine for African Americans and Whites. Soc Sci Med. 2017;193:70-79. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.10.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hall LL, Xu L, Mahmud SM, Puckrein GA, Thommes EW, Chit A. A map of racial and ethnic disparities in influenza vaccine uptake in the medicare fee-for-service program. Adv Ther. 2020;37:2224-2235. doi: 10.1007/s12325-020-01324-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lott BE, Okusanya BO, Anderson EJ, et al. Interventions to increase uptake of Human Papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in minority populations: a systematic review. Prev Med Reports. 2020;19:101163. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2020.101163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Srivastava A, Dempsey A, Galitsky A, Fahimi M, Huang L. Parental awareness and utilization of meningococcal serogroup B vaccines in the United States. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1109. doi: 10.1186/s12889-020-09181-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Van Dorn A, Cooney RE, Sabin ML. COVID-19 exacerbating inequalities in the US. Lancet. 2020;395:1243-1244. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30893-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ivers LC, Walton DA. COVID-19: global health equity in pandemic response. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2020;102:1149-1150. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.20-0260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Health Disparities & Inequalities Report (CHDIR) - Minority Health - CDC. CDC Health Disparities & Inequalities Report (CHDIR). [Google Scholar]

- 35. CDC. Communities, Schools, Workplaces, & Events. Centers Dis Control Prev; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Healthy People 2030 Framwork. HealthyPeople.gov; 2018. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-jpc-10.1177_21501327211018354 for Understanding and Promoting Racial Diversity in Healthcare Settings to Address Disparities in Pandemic Crisis Management by Azza Sarfraz, Zouina Sarfraz, Alanna Barrios, Kuchalambal Agadi, Sindhu Thevuthasan, Krunal Pandav, Manish KC, Muzna Sarfraz, Pedram Rad and George Michel in Journal of Primary Care & Community Health