Abstract

Background:

Dust storms and their impacts on health are becoming a major public health issue. The current study examines the health impacts of dust storms around the world to provide an overview of this issue.

Method:

In this systematic review, 140 relevant and authoritative English articles on the impacts of dust storms on health (up to September 2019) were identified and extracted from 28 968 articles using valid keywords from various databases (PubMed, WOS, EMBASE, and Scopus) and multiple screening steps. Selected papers were then qualitatively examined and evaluated. Evaluation results were summarized using an Extraction Table.

Results:

The results of the study are divided into two parts: short and long-term impacts of dust storms. Short-term impacts include mortality, visitation, emergency medical dispatch, hospitalization, increased symptoms, and decreased pulmonary function. Long-term impacts include pregnancy, cognitive difficulties, and birth problems. Additionally, this study shows that dust storms have devastating impacts on health, affecting cardiovascular and respiratory health in particular.

Conclusion:

The findings of this study show that dust storms have significant public health impacts. More attention should be paid to these natural hazards to prepare for, respond to, and mitigate these hazardous events to reduce their negative health impacts.

Registration: PROSPERO registration number CRD42018093325

Keywords: Air quality, desert dust, dust storm, health, PM10

Introduction

Dust storms are natural hazards and the most common sources of natural particles, including very small materials, potential allergens, and pollutants.1-5 Depending on the nature of the source of the dust, these materials and substances may include, quartz, silicon dioxide, oxides of magnesium, calcium, iron, and aluminum6,7 and sometimes a range of organic matter, anthropogenic pollutants, and salts.8 Dust storms carry millions of tons of soil into the air each year from thousands of kilometers away. They can last a few hours or a few days1-5 and distribute a large number of small particles in the air,9,10 increasing the amount of particles above the allowable threshold for human health.11,12 During a dust storm event, the concentration of PM10 (particles with an aerodynamic diameter <10 µm) and PM2.5 (particles with an aerodynamic diameter <2.5 µm) particles are often higher than the normal thresholds recommended by the World Health Organization (PM2.5: 10 µg/m3 annual mean, 25 µg/m3 24-hour mean. PM10: 20 µg/m3 annual mean, 50 µg/m3 24-hour mean).8,13 It can also exceed 6000 µg/m3 in seriously strong dust storms.14 According to the Huffman Classification of dust PM10 range (μg/ m3), in dusty air, light dust storm, dust storm, strong dust storm, and serious strong dust storm days, levels can be between 50 to 200, 200 to 500, 500 to 2000, 2000 to 5000, and >5000, respectively.15

Dust storms are occurring increasingly frequently in many desert areas and arid regions around the world,3 causing extensive damage and emergencies each year.3,16-18 Therefore, dust storms have attracted increasing attention in recent years.16,17,19 Researchers have demonstrated how dust storms affect various aspects of human life.19 The particles in dust storms affect weather conditions, agricultural production, human health, and the ecosystem.20,21 Evidence suggests that mineral aerosols affect cloud formation and precipitation and can reduce the acidity of precipitation.22 Moreover, a high density and diversity of bacteria and plant pollens have been observed during dust storms.23 In addition to endangering the ecosystem, dust storms have direct and indirect impacts on public health and human health.8,20,21,24 Due to their small sizes, almost all dust storm particles, that is, airborne particles (PM) can enter the respiratory tract25; larger particles are often deposited in the upper respiratory tract (nasopharyngeal region, tracheobronchial region), while smaller particles can enter deep lung tissue.26,27 The physical, biological, and chemical properties of these particles can cause disorders in the health of the body,8,24,26 and in addition to the respiratory tract, can damage other systems of the body, including the cerebral, cardiovascular, skin,8,24,26 blood, and immune systems.28,29

Research has indicated that exposure to dust particles, which can remain in the air from hours to days,24 can result in other problems like conjunctivitis, meningitis, and valley fever.24,26,30 In rare cases, it can even lead to death.26,31 Evidence further suggests that frequent exposure to dust storms can lead to increased adverse health effects24,32-37 in people of almost all age groups and genders.3,38,39 People with a history of diabetes, hypertension, cerebrovascular, or pulmonary disease are also at higher risk.40 Many epidemiological studies have determined the health effects of dust storms by comparing outcomes during dust storm periods with outcomes during non-dust storm periods41-43 and by assessing the correlation between dust storms or PM10 exposure and health outcomes.32,44 Many researcher have acknowledged the existence of a significant association between dust exposure and increased morbidity or mortality, but there is no consensus in this regard to date.45 Pérez et al. stated that increased PM during dust storms caused a significant increase in mortality rate in Barcelona.46 Chen et al.,47 Kashima et al.,48 and Delangizan49 also noted that increased PM10 levels during Asian dust storms increased cardiovascular mortality. Some studies have reported that Middle Eastern dust storms can affect inflammation and coagulation markers in young adults,28,29 have adverse effects on pulmonary function,50 and increase the number of asthma patients.51-52 Conversely, some studies have either ruled out the possibility of an increase in mortality or hospitalizations of patients due to dust storm exposure or do not consider the increase to be significant.43,53-55 For example, in studies conducted in Italy,53 Greece,54 Kuwait,43 and Taipei,55 researchers found no significant relationship between dust storms and increased risk of death. Bell,56 Ueda,57 and Min58 also found that dust storms did not significantly increase hospitalizations of asthmatic patients or asthma attacks in Taipei and Japan.56

There are mixed results and a lack of accurate and up-to-date classified data about the health impacts of dust storms on humans around the world. Moreover, the causes of dust storm-related health problems are not yet completely understood.59 Given the importance of the impact of dust storms on human health as well as the increasing evidence of recurring and negative impacts of these storms, and because of the lack of systematic review studies, the current study conducted an extensive review of the current literature on the impacts of dust storms on human health.

Materials and Methods

This systematic review of scientific resources identified articles related to dust storms and related human health outcomes published up to 30 September 2019. PubMed, EMBASE, Scopus, and ISI WoS (Web of Science) databases were searched for articles published in relevant journals from the 28th to the 30th of October, 2019. All peer-reviewed articles from English language journals were discovered in the primary search stage. Citations and references of all relevant articles were examined and searched manually to ensure that all relevant articles were included. The primary search used the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH terms) and keywords: Dust* OR Kosa OR Yellow sand OR Arabian Sand OR Dust Storms AND Mortality OR Disease* OR Morbidity OR Admission* OR Health* OR “Adverse affect” OR affect*.

Executive limitations: The main limitations of the current study were the lack of access to all required databases as well as the lack of access to the full text of some articles which should be obtained by correspondence with the authors of those articles. To resolve this problem, the researchers resorted to using resources from various universities inside and outside the country.

Inclusion criteria: All studies that had the full text available, that used appropriate methods and data, and that calculated the impacts of dust storms on health (eg, odds ratio, relative risk, rate ratio, regression coefficient, percentage change, excess risk, etc. in health indicators following dust storms); those in which dust storm was a major problem and those in which health indicators were analyzed were included in this study without restrictions on the publication date.

Exclusion criteria: Non-English articles, non-research letters to editors, review studies, case reports, case series, specialized articles about microorganisms, animal experiments, in vitro studies, and dust from volcanic or manmade sources like stone mines or stone and cement factories were excluded.

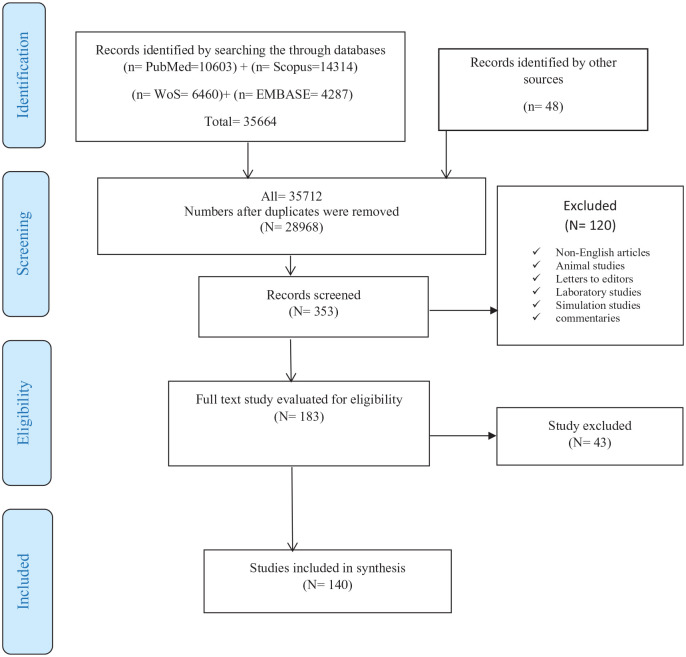

Data collection process: The current study followed the PRISMA guidelines (PRISMA Flow Diagram). EndNote software was used to manage the retrieved articles. After all articles were entered into the software, duplicates were identified and removed. Then, 2 researchers screened the remaining articles separately based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria by reading the titles, abstracts, and keywords. After removing unrelated papers, the full text of the remaining articles were found and attached, and the quality of each paper in a standard format related to the type of study was assessed separately by the 2 researchers using JBI’s critical appraisal tools. In cases of disagreement between the researchers, the third researcher helped to select the most relevant items.

Data extraction: The information required for this study was extracted using a checklist previously reviewed and prepared, which included all the characteristics of the selected articles, including type of article, publication year, first author’s name, location of study, study design/methodology, health effects, PM fraction, and age/gender.

Risk of bias (quality) assessment: For quality assessment of the included papers, the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) checklist was used. The assessment was conducted by 3 independent reviewers. Discrepancies were resolved by 2 other reviewers.

Results

Search results

Out of a total of 35 712 articles searched, 140 articles met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The majority of them were related to ecological, case crossover, and prospective studies; other studies included descriptive, retrospective, and Panel studies and 1 research letter (Table 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

Table 1.

Published studies on adverse health effects of dust storms.

| Reference | First author and year | Study location | Population (age, gender) | PM Fraction | Study design/methodology | Health outcomes | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All-cause mortality | |||||||

| Al et al.86 | Al et al. (2018) | Gaziantep/Turkey | Older than 16 years | PM10 | Retrospective study/GAM | Mortality of cardiovascular diseases | Congestive cardiac failure Mortality, OR 0.95 (0.81–1.11) Acute coronary syndrome mortality, OR 0.40 (0.31–0.50) |

| Al-Taiar and Thalib43 | Al-Taiar and Thalib (2014) | Kuwait | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series, GAM | All-causes, respiratory, cardiovascular Mortality | Respiratory mortality, RR 0.96 (0.88–1.04) Cardiovascular mortality, RR 0.98 (0.96–1.012) All-cause mortality, RR 0.99 (0.97–1.00) |

| Chan and Ng38 | Chan and Ng (2011) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/conditional logistic regression models | Non-accidental, respiratory, cardiovascular, deaths | Non-accidental deaths, OR 1.019 (1.003–1.035) Above 65 years old, OR 1.025 (1.006–1.044) Cardiovascular deaths, OR 1.045 (1.0011–1.081) Respiratory deaths, OR 0.988 (1.038–0.941) |

| Chen et al.39 | Chen et al. (2004) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/tests of student | Daily mortality | Respiratory disease, RR 7.66% Total deaths, RR 4.92% Circulatory diseases, RR 2.59% |

| Crooks et al.3 | Crooks et al. (2016) | National/United States | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/conditional logistic regression models | Daily non-accidental mortality | Non-accidental mortality 7.4% (p = 0.011) Lag2,3 6.7% (p = 0.018) Lags0–5 2.7% (p = 0.023) |

| Díaz et al.68 | Díaz et al. (2017) | Spain: 9 region | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Longitudinal ecological time series/GAM | Daily mortality | Daily mortality values South-west, 21.20 (20.81–21.59) p < 0.05 South-east, 20.16 (19.88–20.45) p < 0.05 Canary Islands, 17.93 (17.60–18.26) p < 0.05 |

| Diaz et al.69 | Diaz et al. (2012) | Madrid (Spain) | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover design/Poisson regression model | Case-specific mortality | Respiratory death, IR 3.34% (0.36, 6.41) Circulatory causes, IR 4.19% (1.34, 7.13) |

| Hwang et al.70 | Hwang et al. (2004) | Seoul, Korea | All ages/ all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series / GAM | Daily non accidental deaths | Non accidental deaths, 1.7% (1.6 5.3) Aged 65 years and older, 2.2% (3.5 8.3) Cardiovascular and respiratory, 4.1% ( 3.8 12.6) |

| Jimenez et al.71 | Jimenez et al. (2010) | Madrid (Spain) | Elderly | PM10, PM2.5 or PM10–2.5 | Ecological time series/Poisson regression models | Mortality | PM10

Total mortality, lag3 1.02 (1.01–1.04) Circulatory, lag3 1.04 (1.01–1.06) Respiratory, lag1 1.03 (1.00–1.06) |

| Johnston et al.72 | Johnston et al. (2011) | Sydney, Australia | All ages/ all gender | PM10 | Case crossover /conditional logistic regression model | Non-accidental mortality | Non-accidental mortality, lag3, OR 1.16 (1.03–1.30) |

| Kashima et al.73 | Kashima et al. (2016) | South Korea and Japan | >65 years old/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time-series analyses/specific Poisson regression models | Cause-specific mortality | All-cause mortality, lag0 RR 1.003 (1.001 1.005) lag1, 1.001 (1.000 1.003) Cerebrovascular disease, lag1 RR: 1.006 (1.000 1.011) |

| Kashima et al.48 | Kashima et al. (2012) | Western Japan | Aged 65 or above l | SPM | Ecological multi-city time-series analysis/Poisson regression models | Daily all-cause or cause-specific mortality | Heart disease, 0.6 (0.1 1.1) Ischemic heart disease, 0.8 (0.1 1.6) Arrhythmia, 2.1 (0.3 3.9) Pneumonia mortality, 0.5 (0.2 0.8) |

| Khaniabadi et al.87 | Khaniabadi et al. (2017) | Ilam (Iran) | – | PM10 | Ecological time series/air Q model | Respiratory mortality | Respiratory Mortality 7.3 (4.9 19.5) |

| Kim et al.74 | Kim et al. (2012) | Seoul, Korea | General population/all gender | – | Ecological time-series/Poisson regression analyses | All-cause/cardiovascular mortality | The relative risk of total mortality for general population and over 75 years old increased on dusty days |

| Kwon et al.83 | Kwon et al. (2002) | Seoul, Korea | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series/GLM with Poisson regression | Non accidental deaths | All causes, RR 1.7% (1.6, 5.3) Persons aged 65 years older, RR 2.2% (3.5, 8.3) Cardiovascular and respiratory death, RR 4.1% (3.8, 12.6) |

| Lee et al.55 | Lee et al. (2014) | (Seoul, Korea; Taipei, Taiwan, Kitakyushu, Japan) | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time-series using/GAM with Quasi-Poisson distribution | Mortality | Seoul: Under 65 years old (lag2: 4.44%, lag3: 5%, and lag4: 4.39%) Kitakyushu: Respiratory mortality (lag2: 18.82%) Total non-accidental mortality (lag0: −2.77%, lag1: -3.24%) Taipei: Over 65 years old (lag0: −3.35%, lag1: −3.29%) Respiratory mortality (lag0: −10.62%, lag1: −9.67%) |

| Lee et al.75 | Lee et al. (2013) | Seven metropolitan cities of Korea | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time-series/GAM with Quasi-Poisson regressions | Mortality | Lag0

Cardiovascular, 2.91% (0.13, 5.77) Male: 2.74% (0.74, 4.77) Lag2 <65 years, 2.52% (0.06, 5.04) Male 2.4% (0.43, 4.4) Lag3 <65 years, lag3 2.49% (0.07, 4.97) Total non-accidental: 1.57% (0.11, 3.06) Male: 2.24% (0.28, 4.0) <65 years: 2.43% (0.01, 4.91) lag5 cardiovascular: 3.7% (0.93, 6.54) |

| Lee et al.76 | Lee et al. (2007) | Seoul, Korea | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time-series, GAM | Mortality | Total death, IR 0.7 (0.2, 1.3) |

| Mallone et al.84 | Mallone et al. (2011) | Rome, Italy | ⩾35 years/all gender | PM2.5, PM2.5–10, and PM10 | Case-crossover/Poisson regression model | Mortality | PM2.5–10 Cardiac mortality, lag 0–2, IR 9.73 (4.25–15.49) Circulatory system, lag 0–2, IR 7.93 (3.20 12.88) PM10 Cardiac mortality, lag 0–2, IR 9.55 (3.81–15.61%) |

| Perez et al.46 | Perez et al. (2008) | Barcelona (Spain) | All ages/all gender | PM2.5 and PM10-2.5 | Case crossover/linear regression | Daily Mortality | PM10-2.5

Daily mortality, Lag1, OR 1.084 (1.015, 1.158) |

| Perez et al.85 | Perez et al. (2012) | Barcelona (Spain) | All ages/all gender | PM1, PM2.5 and PM10 | Case–crossover/conditional logistic regression | Cause-specific mortality | PM10-2.5 OR Cardiovascular mortality, (lag1) 1.085 (1.01 1.15) p < 0.05 Respiratory mortality, (lag 2) 1.109 (0.978, 1.257) p < 0.1 PM2.5-1 OR Cardiovascular mortality, (lag1) 1.074 (0.998, 1.156) p < 0.1 |

| Renzi et al.77 | Renzi et al. (2018) | Sicily, Italy | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time-series/Poisson conditional regression model | Mortality | Non-accidental mortality, (lag0–5) IR 3.8% (3.2, 4.4) Cardiovascular, IR 4.5% (3.8, 5.3) Respiratory IR 6.3% (5.4, 7.2) |

| Pirsaheb et al.50 | Pirsaheb et al. (2016) | Kermanshah, Iran | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Descriptive studies/spearman test | Death from cardiovascular and respiratory disease | Increased dust concentrations increase the risk of cardiovascular mortality |

| Schwartz et al.88 | Schwartz et al. (1999) | Six United States. cities | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological/GAM with Poisson regression | Mortality | Mortality, RR 0.99 (0.81–1.22) |

| Sajani et al.53 | Sajani et al. (2011) | Emilia-Romagna (Italy) | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case crossover/conditional logistic regression | Mortality | Respiratory mortality, OR 22.0 (4.0–43.1) Natural, OR 1.04 (0.99–1.09) Cardiovascular mortality, OR 1.04 (0.96–1.12) |

| Stafoggia et al.78 | Stafoggia et al. (2016) | Southern European cities-Spain, France, Italy, Greece | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/Poisson regression models | Mortality | Natural mortality lag0–1, IR 0.65% (0.24–1.06) |

| Shahsavani et al.79 | Shahsavani et al. (2019) | Tehran and Ahvaz, IRAN | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case crossover/conditional Poisson regression models | Mortality | Daily mortality 3.28 (2.42–4.15) |

| Tobias et al.80 | Tobias et al. (2011) | Madrid (Spain) | All ages/all gender | PM2.5 and PM10–2.5 | Case-crossover/conditional logistic regression models | Mortality | PM10–2.5

Each increase of 10 μg/m3 of PM10–2.5 increased Total mortality, 2.8% (P = 0.01) |

| Wang and Lin81 | Wang and Lin (2015) | Metropolitan Taipei | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series/distributed lag non-linear model | Mortality | All-cause mortality lag0-5, RR 1.10 (1.04–1.17) Elders 1.10 (1.02–1.18) Elderly circulatory Mortality lag0-5, RR 1.21 (1.02–1.44) |

| Samoli et al.54 | Samoli et al. (2011) | Athens, Greece | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series/Poisson regression models | Mortality | Mortality 0.71% (0.40 0.99) |

| Neophytou et al.82 | Neophytou et al. (2013) | Nicosia, Cyprus | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time-series/GAM | Mortality | Total nom accidental, IR 0.13% (1.03, 1.30) Cardiovascular mortality, IR 2.43 (0.53–4.37) Respiratory mortality, IR 0.79 (4.69, 3.28) |

| Goto et al.60 | Goto et al. (2010) | Western Japan | All ages/all gender | – | Ecological time-series/Spearman’s rank correlation | Bronchial asthma mortality | Asthma mortality (r = 0.268, n = 8, P > 0.05) |

| Achilleos et al.41 | Achilleos et al. (2019) | Kuwait | All ages/all gender | Poor visibility (AOD >0.4) | Ecological time-series/generalized additive model (GAM)/Poisson regression models | Mortality | Rate ratio: 1.02, (1.00–1.04) |

| Emergency dispatch or air medical retrieval service | |||||||

| Holyoak et al.90 | Holyoak et al. (2011) | Queensland, Australia | – | – | Ecological retrospective review/simple t-test | Air medical retrieval service for respiratory and injury cases | Respiratory cases 62.5% increased Injury cases 13.3% increased |

| Aghababaeian et al.42 | Aghababaeian et al. (2019) | Iran/dezful | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time-series /GAM | Emergency dispatch of cardiovascular, respiratory and traffic accident missions | RR of Emergency dispatch Lag2 1.008 (1.001–1.016)/female/18–60 years/>60 years Lag3 1.008 (1.00 1.01) Lag4 1.008 (1.00–1.01) Lag5 1.008 (1.00–1.01) Lag6 1.007 (1.00–1.01) Lag7 1.006 (1.000–1.01) Lag0-7 1.06 (1.01–1.12) Lag0-14 1.09 (1.01–1.17) >60 years 1.28 (1.08–1.52) Cardiovascular Problems Lag0-14 1.33 (1.17–1.50) Respiratory problems Lag0-14 1.13 (0.93–1.38) Traffic Accident Trauma Lag0-14 1.03 (0.94–1.13) |

| Kashima et al.89 | Kashima et al. (2014) | Okayama, Japan | Elderly people | SPM | Ecological time-series/Poisson regression with GAM | Emergency ambulance calls | All causes, Lag 0 1.009 (1.002–1.017) Cardiovascular, lag0-3 1.02 (1.00–1.03) Cardiovascular, Lag0 1.016 (1.001–1.032) Cerebrovascular, Lag0 1.028 (1.007–1.049) Pulmonary, Lag0 1.005 (0.986–1.025) |

| Ueda et al.61 | Ueda et al. (2012) | Nagasaki, Japan | All ages/all gender | SPM | Case-crossover/conditional logistic regression | Emergency ambulance dispatches | All causes lag0–3 12.1% (2.3–22.9) Cardiovascular diseases 20.8% (3.5–40.9) |

| Visits | |||||||

| Akpinar-Elci et al.137 | Akpinar-Elci et al. (2015) | Grenada, Caribbean | All ages/all gender | – | Ecological/regression analysis | Asthma visits | Asthma (R2 = 0.036, p < 0.001) |

| Cadelis et al.138 | Cadelis et al. (2014) | Guadeloupe (Caribbean) | Children/all gender | PM10, PM2.5-10 | Case-crossover/t-test and Mann-Whitney | Visits of children due to asthmatic conditions | PM10

Lag0 IR 9.1% (7.1–11.1) Lag0–1 IR 5.1% (1.8–7.7) PM2.5–10 Lag0 IR 4.5% (3.3–5) Lag0–1 IR: 4.7% (2.5–6.5) |

| Carlsen et al.142 | Carlsen et al. (2015) | Reykjavík, Iceland | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time-series study/generalized additive regression model | Emergency hospital visits | Emergency hospital visits 5.8% (p = 0.02) |

| Chan et al.143 | Chan et al. (2008) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time-series/Poisson regression model and paired t-test | Emergency visits | Cardiovascular visits 1.5 (0.3–2.6) Ischemic heart diseases visits 0.7 (0.1–1.4) Cerebrovascular visits 0.7 (0.1–1.3) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) visits 0.9 (0.1–1.7) |

| Chien et al.144 | Chien et al. (2014) | Taipei, Taiwan | Children | PM10 | Ecological studies/structural additive regression modeling | Conjunctivitis clinic visits | Conjunctivitis visits Preschool children 1.48% (0.79, 2.17) Schoolchildren. 9.48% (9.03, 9.93) |

| Chien et al.146 | Chien et al. (2012) | Taipei, Taiwan | Children | PM10 | Ecological/STAR model and autoregressive correlation | Respiratory diseases visits | Respiratory visits Preschool children 2.54% (2.43, 2.66) Schoolchildren 5.03% (4.87, 5.20) |

| Hefflin et al.147 | Hefflin et al. (1994) | Washington, United States | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological/multivariable analysis using generalized estimating equations | Emergency room visits for respiratory disorders | Daily number of emergency visits for bronchitis, IR 3.5% Daily Number of emergency room visits, IR 4.5% |

| Lin et al.148 | Lin et al. (2016) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series/DLNM | Emergency room visits | All causes visits, RR 1.10 (1.07, 1.13) Respiratory visits, RR 1.14 (1.08, 1.21) |

| Liu and Liao149 | Liu and Liao (2017) | Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM2.5 | Case-crossover/conditional logistic regression | Emergency visits | Cardiovascular, OR 2.92 (1.22–5.08) Respiratory, OR 1.86 (1.30–2.91) |

| Merrifield et al.141 | Merrifield et al. (2013) | Sydney, Australia | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time-series/distributed-lag Poisson generalized models | Emergency visits | Asthma visits, RR 1.23, (p < 0.01) All visits, R 1.04, (p < 0.01) Respiratory visits, RR 1.20, (p < 0.01) Cardiovascular visits, RR 0.91, (p = 0.09) |

| Nakamura et al.139 | Nakamura et al. (2016) | Nagasaki, Japan | children aged 0–15 years/all gender | SPM | Case-crossover/conditional logistic models | Pediatric emergency visits for respiratory diseases | School children Bronchial asthma visits, lag3 OR 1.83 (1.212–2.786) Lag4 1.829 (CI, 1.179–2.806) Preschool children Respiratory visit, lag0, OR 1.244 (1.128–1.373) Lag day 1, OR 1.314 (1.189–1.452) Lag day 2, OR 1.273 (1.152–1.408) |

| Park et al.62 | Park et al. (2015) | Chuncheon, Gangwon-do, Korea | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological retrospective study/Poisson regression model | Hospital visits for airway diseases | Asthma visits, RR 1.10 (P < 0.05) COPD visits, RR 1.29 (P < 0.05) |

| Wang et al.63 | Wang et al. (2016) | Minqin, China | All ages/all gender | – | Ecological time series/generated regression model | Pulmonary tuberculosis (PTB) visits | PTB visits, R2 = 0.685 |

| Park et al.140 | Park et al. (2016) | Seoul and Incheon, Korea | 11–20, 51–70 and 490 years/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/T-tests and Poisson regression model | Asthma exacerbation | Asthma related visits Lag0, RR 0.96 (0.95–0.98) Lag1, RR 1.27 (1.25–1.29) Lag2, RR 1.12 (1.10–1.14) Lag3, RR 1.25 (1.23–1.26) Lag4, RR 1.13(1.12–1.15) Lag5, RR 1.06 (1.04–1.07) Lag6, RR 0.82 (0.81–0.81) |

| Yu et al.12 | Yu et al. (2012) | Taipei (Taiwan) | Children | PM10 | Ecological studies/STAR model/generalized additive mode | Children’s respiratory health risks | All children Lag0 −3.66 Lag1 −2.05 Lag2 1.78 Lag3 2.40 Lag4 0.66 Lag5 1.74 Lag6 −1.01 Lag7 2.26 |

| Yang145 | Yang (2006) | Taipe, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/Poisson regression model | Conjunctivitis visit | Lag0 RR 1.02 (0.88–7.99) Lag1 RR 0.99 (0.86–7.46) Lag2 RR 0.95 (0.83–6.93) Lag3 RR 0.97 (0.85–7.11) Lag4 RR 1.11 (0.97–9.41) Lag5 RR 0.95 (0.84–6.86) |

| Lorentzou et al.122 | Lorentzou et al. (2019) | Heraklion in Crete Island, Greece | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological retrospective analysis/one-way ANOVA and Pearson Correlation | Emergency department visits | Correlation All cases 0.313 p = 0.128 Allergy cases 0.929 p = 0.000 Dyspnea cases 0.464 p = 0.041 |

| Trianti et al.52 | Trianti et al. (2017) | Athens, Greece | Aged 18 years and Upper/all gender |

PM10 | Ecological study/mixed Poisson model | Respiratory morbidity/emergency room visits | Respiratory visits, IR 1.95% (0.02, 3.91) Asthma visits, IR 38% (p < 0.001) COPD visits, IR 57% (p < 0.001) Respiratory infections visits, IR 60% (p < 0.001) |

| Yang et al.150 | Yang et al. (2015) | Wuwei, China | All ages/ all gender | PM2.5 | Ecological time-series/GAM | Respiratory and cardiovascular outpatient visits | Respiratory outpatient Male, RR 1.217 (1.08, 1.606) Female, RR 1.175 (1.025, 1.347) Cardiovascular outpatient Male, RR 1.146 (1.056, 1.243) Female, RR 1.105 (1.017, 1.201) |

| Long-term health effects | |||||||

| Altindag et al.32 | Altindag et al. (2017) | Korea | Infant | PM10 | Cohort/linear regression models | Birth weight, a binary indicator of low birthweight, gestation, premature birth, and fetal growth | Birth Weight, _0.232 (P = 0.10) Low birth weight, 0.0001 (P = 0.000) Gestation −0.001 (P = 0.001) Prematurity, 0.0001 (P = 0.000) Growth, −0.005 (P = 0.003) |

| Dadvand et al.169 | Dadvand et al. (2011) | Barcelona/Spain | Pregnant woman | PM10 | Cohort/linear regression models-logistic regression model | Pregnancy complications | Birth weight −2.1 (−5.8, 1.7) Gestation 0.5 (0.4, 0.6) Preeclampsia 0.98 (0.91, 1.07) |

| Li et al.33 | Li et al. (2018) | Between northern and southern China. | Aged 10–15 years, all gender | – | Cohort/fixed-effect model | Children’s cognitive function | Reduction in word scores, 0.20 (0.06, 0.35) Reduction in mathematics scores 0.18 (0.10, 0.25) |

| Viel et al.34 | Viel et al. (2019) | Guadeloupe (French West Indies) | 909 pregnant women | PM10 | Cohort/multivariate logistic regression models | Preterm births | OR 1.40, (1.08–1.81) |

| Tong et al.36 | Tong et al. (2017) | Southwestern United States | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Research letter/correlation coefficient | Valley fever | Correlation coefficient Maricopa, 0.51 Pima, 0.36–0.41 |

| Ma et al.44 | Ma et al. (2017) | Western China | All ages/ all gender | TSP, PM10 | Ecological time series/Pearson correlation coefficient | Measles incidence | The correlation coefficient for TSP Entire Lanzhou city, 0.291 Downtown Lanzhou, 0.346 The correlation coefficient for PM10 Entire Lanzhou city, 0.260 Downtown Lanzhou, 0.342 Dust events, Excess measles Zhangye, 39.1 (17.3–87.6) Lanzhou, 149.9 (7.1–413.4) Jiuquan, 31.3 (20.6–63.5) |

| Hospitalization or admission | |||||||

| Aili and Oanh91 | Aili and Oanh (2015) | China/Taklimakan Desert | All ages/all gender | TSP | Ecological time series/GAM | Daily number of outpatients Daily number of inpatients |

Respiratory outpatients, RR 1.01 (1.00–1.02) Respiratory inpatients, RR 0.99 (0.99–1.00) Digestion outpatients, RR 1.005 (0.99–1.01) Digestion inpatients, RR 1.001 (0.999–1.002) Circulatory outpatients, RR 1.010 (1.003–1.016) Circulatory inpatients, RR 1.001 (0.999–1.002) Gynecology outpatients, RR 1.008 (1.002–1.014) Gynecology inpatients, RR 0.999 (0.997–1.001) Pediatrics outpatients, RR 1.010 (1.002–1.018) Pediatrics Inpatients, RR 1.001 (0.999–1.002) ENT outpatients, RR, 1.007 (1.002–1.012) ENT inpatients, RR, 1.002 (0.998–1.004) |

| Al et al.86 | Al et al. (2018) | Gaziantep/Turkey | Older than 16 years | PM10 | Retrospective study/GAM | Morbidity of cardiovascular diseases admitted to emergency department | Congestive cardiac failure admission, OR 1.003 (0.972–1.036) Hospitalization, OR 2.209 (2.069–2.359) Acute coronary syndrome admission, OR 1.150 (1.135–1.166) Hospitalization, OR 1.304 (1.273–1.336) |

| Alangari et al.126 | Alangari et al. (2015) | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | Children 2–12 years | PM10 | Ecological/correlation coefficient | Patient presented to the emergency department (ED) with acute asthma | Acute asthma, r = –0.14, (P = 0.45) Admission rate, r = −0.08, (P = 0.65) |

| Alessandrini et al.92 | Alessandrini et al. (2013) | Rome, Italy | Less than 14 years or 35 years or more | PM2.5, PM2.5-10

and PM10 |

Ecological time-series/GAM | Respiratory, cardiac and cerebrovascular hospitalizations | PM2.5

Cardiac diseases, lag0–1 2.41 (−0.21, 5.09) Cerebrovascular diseases, lag0 −2.14 (−4.73, 0.53) Respiratory diseases, lag0–5 −0.52 (−5.33, 4.53) Respiratory diseases0–14 −2.14 (−9.09, 5.35) PM2.5–10 (IR) Cardiac diseases, lag0–1 3.93 (1.58, 6.34) Cerebrovascular diseases, lag0 1.68 (−0.70, 4.11) Respiratory Diseases, lag0–5 4.77 (−0.57, 10.40) Respiratory diseases lag0–14 −1.20 (−8.52, 6.71) PM10 Cardiac diseases, lag0–1 3.37 (1.11, 5.68) Cerebrovascular diseases, lag0 2.64 (0.06, 5.29) Respiratory Diseases, lag0–5 3.59 (0.18, 7.12) Respiratory diseases, lag0–14 −0.04 (−4.64, 4.78) |

| Al-Hemoud et al.93 | Al-Hemoud et al. (2018) | Kuwait | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series/GAM | Daily morbidity | Bronchial asthma, r = 0.292 Respiratory infection Lower, r = 0.737 upper, r = 0.839 |

| Al-Taiar51 | Al-Taiar (2012) | Kuwait | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series generalized/GAM |

Daily emergency admissions due to asthma and respiratory causes | Asthma admission, RR 1.07 (1.02–1.12) Respiratory admission, RR 1.06 (1.04–1.08) |

| Barnett127 | Barnett (2012) | Brisbane, Australia | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series/Poisson regression model | Emergency admissions to hospital | Emergency admissions 39% (5, 81%) |

| Bell et al.56 | Bell et al. (2008) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time-series/Poisson time-series model | Cause-specific hospital admissions | Ischemic heart disease, Lag2 16.17 (1.17, 33.39) |

| Chan et al.135 | Chan et al. (2018) | Nationwide/Taiwan | All ages/all gender | Total atmospheric PM | Ecological time-series/autoregressive model-ARMAX regression | Diabetes hospitalization | Diabetes lag1 27.41 (p = 0.04) |

| Chen and Yang94 | Chen and Yang (2005) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/tests of student | Daily hospital admissions for cardiovascular disease (CVD) | CVD, lag1 RR (3.65%) P > 0.05 |

| Cheng et al.119 | Cheng et al. (2008) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/Poisson regression models | Daily pneumonia hospital admissions | Pneumonia admissions lag0 RR 1.03 (0.98–1.08) lag1 RR 1.04 (1.00–1.09) lag2 RR 1.04 (0.99–1.09) lag3 RR 1.03 (0.99–1.08) |

| Chiu et al.121 | Chiu et al. (2008) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/Poisson regression models | COPD admissions | COPD, Lag3, RR 1.057; (0.982–1.138) |

| Dong et al.59 | Dong et al. (2007) | large cities of Korea | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological/correlation coefficients | Hospitalization | Seoul 0.652 Busan 0.377 Daegu 0.681 Incheon 0.736 Kwangju 0.481 Daejeon 0.652 Uisan 0.702 Jeju-do 0.129 |

| Ebenstein et al.107 | Ebenstein et al. (2015) | Israel, Jerusalem and Tel Aviv | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological/IV methodology/Poisson regression approach | Respiratory hospital admissions | Respiratory admissions IR 0.8% COPD 0.01 (0.003) Asthma 0.008 (0.003) Respiratory abnormalities 0.006 (0.002) |

| Ebrahimi et al.92 | Ebrahimi et al. (2014) | Sanandaj, Iran | All ages/ all gender | PM10 | Ecological/Pearson’s correlation coefficient, linear regression model | Emergency admissions for cardiovascular and respiratory diseases | Cardiovascular 0.48 (P < 0.05) Respiratory patients 0.19 (P > 0.05) |

| Ebrahimi et al.64 | Geravandi et al. (2017) | Ahvaz/Iran | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological/non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test/correlation coefficients | Hospital admissions for Respiratory diseases | Respiratory diseases (r = 0.53) |

| Grineski et al.11 | Grineski et al. (2011) | El Paso, Texas, United Stats | All ages/all gender | PM2.5 | Case-crossover/-conditional logistic regression | Hospital admissions for Asthma and Acute bronchitis | Asthma 1.11 (0.96–1.28) All ages 1.23 (0.99–1.55) |

| Kamouchi et al.131 | Kamouchi et al. (2012) | Fukuoka, Japan | 20 years and older/all gender | – | Case-crossover/conditional logistic regression | Ischemic stroke | Overall///AtherothromboticZ D7 lag0–1, OR 1.07 0.93–1.23///1.44 1.08–1.91 lag0–2, OR 1.04 0.97–1.18///1.48 1.14–1.93 lag0–3, OR 1.02 0.90–1.15///1.37 1.06–1.76 lag0–4, OR 1.02 0.90–1.14///1.35 1.06–1.73 lag0–5, OR 1.02 0.91–1.15///1.35 1.06–1.72 |

| Kanatani et al.115 | Kanatani et al. (2010) | Toyama, Japan | Children | – | Case-crossover/generalized estimating equations logistic and Conditional logistic regression | Asthma hospitalization | OR 1.88 (1.04–3.41; P 5 0.037) |

| Kang et al.120 | Kang et al. (2012) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series/Kruskal–Wallis test/auto-regressive integrated moving average (ARIMA) method | Pneumonia hospitalization | Pneumonia admissions (P = 0.001) |

| Kang et al.132 | Kang et al. (2013) | Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM | Ecological time series/ARIMA method (auto-regressive integrated moving average) | Stroke hospitalization | Stroke admissions (239.6), post-DS days (249.2) (p < 0.001) |

| Kashima et al.40 | Kashima et al. (2017) | Okayama, Japan | Elderly | SPM | Case-crossover/conditional logistic regression analyses | Susceptibility of the elderly to disease | Respiratory OR: 1.09 (1.00, 1.19) Cardiovascular OR: 0.99 (0.97, 1.01) Cerebrovascular OR: 1.15 (1.01, 1.31) |

| Khaniabadi et al.87 | Khaniabadi et al. (2017) | Khorramabad (Iran) | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series/AirQ model | Hospitalizations for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | COPD, ER, 7.3% (4.9, 19.5) |

| Khaniabadi et al.95 | Khaniabadi et al. (2017) | Ilam, Iran | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series/AirQ model | Cardiovascular and respiratory admissions | Respiratory diseases 4.7% (3.2–6.7%) Cardiovascular diseases, 4.2% (2.6–5.8%) |

| Ko et al.136 | Ko et al. (2016) | Fukuok- western Japan | Men, Women ratio 30,15 Age, 49.6 ± 22.7 | – | Cohort design/t-test | Acute conjunctivitis | Conjunctivitis scores P < 0.05 |

| Kojima et al.98 | Kojima et al. (2017) | Kumamoto, Japan | 20 years of age or older/all gender | PM2.5 | Case-crossover/conditional logistic regression model | Acute myocardial infarction (AMI) | AMI OR, 1.46 (1.09–1.95) Non ST-segment OR 2.03 (1.30–3.15) |

| Lai and Cheng109 | Lai and Cheng (2008) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-control/Z test | Respiratory admissions | Elderly RR 3.44; (0.03–380.1) All age RR 1.04; (0.30–3.16) Pre-school RR, 1.01 (0.26–3.89) |

| Lee and Lee117 | Lee and Lee (2014) | Seoul, Korea | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series patterns/paired t-test | Daily asthma patients | Lag0, 3.79 p = 0.4 Lag1, 4.85 p = 0.3 Lag2, 11.02 p = 0.1 Lag3, 15.46 p = 0.06 Lag4, 18.05 p = 0.03 Lag5, 17.76 p = 0.02 Lag6, 18.18 p = 0.01 |

| Lorentzou et al.122 | Lorentzou et al. (2019) | Heraklion in Crete Island, Greece | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological/one-way ANOVA and Pearson correlation | COPD morbidity | COPD exacerbations, 3.0 (0.8–5.2) Dyspnea admissions, 0.71 (p = 0.001) COPD admissions, 0.813 p = 0.000 |

| Matsukawa et al.99 | Matsukawa et al. (2014) | Fukuoka, Japan | Patients aged ⩾20 years/all gender | SPM | Case-crossover/conditional logistic regression model | Incidence of acute myocardial infarction | AMI Lag4 OR 1.33 (1.05–1.69) Lag0-4 OR 1.20 (1.02–1.40) |

| Menendez et al.128 | Menendez et al. (2017) | Gran Canaria, Spain | Adults (age 14–80 years) and >80/all gender | PM10 | Epidemiological survey/(ANOVA) and Spearman correlation coefficients (ρ) | Health condition of the allergic population |

ρ (p-values) Pneumony 0.2 (0.5) Asthma 0.8 (0.0) COPD 0.0 (1.0) |

| Meng and Lu96 | Meng and Lu (2007) | Minqin, China | All ages/all gender | – | Ecological time-series/GAM | Daily hospitalization for respiratory and cardiovascular diseases | Respiratory hospitalization, lag3 RR Male 1.14 (1.01–1.29) Female 1.18 (1.00–1.41) Respiratory infection, Male, RR 1.28 (1.04–1.59 Pneumonia, Lag6 Males, RR 1.17 (1.00–1.38) Hypertension, Lag3 Males, RR 1.30 (1.03, 1.64) |

| Middleton et al.97 | Middleton et al. (2008) | Nicosia, Cyprus | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time-series/GAM | Respiratory and cardiovascular morbidity | All-cause 4.8% (0.7, 9.0) Cardiovascular 10.4% (−4.7, 27.9) |

| Nakamura et al.103 | Nakamura et al. (2015) | All-Japan | All ages/all gender | SPM | Case-crossover/conditional logistic models | Out-of-hospital cardiac arrests | Cardiac arrests, lag1 OR Model 1 1.00 (0.97–1.19) Model 2 1.08 (0.97–1.20) |

| Nastos, et al.104 | Nastos, et al. (2011) | Crete Island, Greece | All ages/all gender | – | Ecological time series-HYSPLIT 4 model of air resources laboratory of NOAA | Cardiovascular and respiratory syndromes | Respiratory five-fold increased Cardiovascular didn’t increased significant |

| Pirsaheb et al.50 | Pirsaheb et al. (2016) | Kermanshah, Iran | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological/regression | Respiratory disease | Respiratory infection P ⩽ 0.05 Chronic pulmonary disease P ⩽ 0.05 COPD P > 0.05 Angina P > 0.05 Asthma P > 0.05 |

| Prospero et al.129 | Prospero et al. (2008) | Caribbean | Aged 18 years and under/all gender |

– | Ecological time series/Mann–Whitney rank-sum test, two-tailed | Pediatric asthma | Pediatric asthma, P > 0.05 |

| Radmanesh et al.133 | Radmanesh et al. (2019) | Abadan, Iran | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological studies/Pearson coefficient | Hospital admission for cerebral ischemic attack, epilepsy and headaches | Cerebral ischemic attack, r: 0.113 p = 0.3 Epilepsy, r: 0.492 p = 0.03 Headaches, r: 0.009 p = 0.9 |

| Reyes et al.110 | Reyes et al. (2014) | Madrid (Spain) | All ages/all gender | PM10-2.5 | Ecological time series/conditional logistic regression model | Hospital admissions | Respiratory admissions, Lag7 RR 1.031 (1.002 1.060) |

| Rutherford, et al.118 | Rutherford, et al. (1999) | Brisbane, Australia | All ages/all gender | TSP | Cross sectional/paired two-tailed t-tests | Impact on asthma severity | Asthma severity, P ⩽ 0.05 In General P > 0.05 |

| Stafoggia et al.78 | Stafoggia et al. (2016) | Southern European cities-Spain, France, Italy, Greece | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/”Poisson regression models | Hospital admissions | Admissions, IR Cardiovascular, age ⩾15 0.32 (–0.24, 0.89) Respiratory, age ⩾15 0.70 (–0.45, 1.87) Respiratory, age 0–14 2.47 (0.22, 4.77) |

| Tam et al.101 | Tam et al. (2012) | Hong Kong | All ages/all gender | PM10-2.5 | Case-crossover/t-test/Poisson regression model | Daily emergency admissions for cardiovascular diseases | PM10–2.5 Ischemic heart disease, RR 1.04 (1.00, 1.08) |

| Tao et al.111 | Tao et al. (2012) | Lanzhou, China | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological/Poisson regression model into GAM model | Respiratory diseases admissions | Respiratory hospitalizations, RR Male, 1.148 P > 0.05 Female 1.144 P > 0.05 |

| Teng et al.100 | Teng et al. (2016) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series/autoregressive with exogenous variables model | Daily acute myocardial infarction hospital admissions | AMI hospitalizations, 3.2 more |

| Thalib and Al-Taiar51 | Thalib and Al-Taiar (2012) | Kuwait | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series study/GAM | Asthma admissions | Asthma, RR 1.07 (1.02–1.12) Respiratory admission, RR 1.06 (1.04–1.08) |

| Ueda et al.57 | Ueda et al. (2010) | Fukuoka, Japan | children under 12 years of age/all gender | SPM | Case-crossover/conditional logistic regression | Hospitalization for asthma | Asthma hospitalization, lag2,3 OR 1.041 (1.013–1.070) |

| Vodonos et al.123 | Vodonos et al. (2014) | Be’er Sheva, Israel | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series/GAM | Hospitalizations due to exacerbation of COPD | COPD exacerbation: IR 1.16 (p < 0.001) |

| Vodonos et al.2 | Vodonos et al. (2015) | Be’er Sheva, Israel | Above 18 years old/all gender | PM10 | Case crossover/GAM | Cardiovascular Morbidity | Acute coronary syndrome (lag1); OR = 1.007 (1.002–1.012). |

| Wang et al.113 | Wang et al. (2014) | Taiwan, | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time series/ARIMAX regression model | Asthma admissions | Asthma, Lag1-3 average of 17–20 (p < 0.05) more hospitalized |

| Wang et al.125 | Wang et al. (2015) | Minqin County, China | Above 40 years old/all gender | – | Case-control/comparison/Student’s t test | Human respiratory system | Chronic rhinitis, OR 3.14 (1.77–5.55) Chronic bronchitis, OR 2.46 (1.42–4.28) Chronic cough, OR 1.78 (1.24–2.56) |

| Watanabe et al.114 | Watanabe et al. (2014) | Western Japan | Aged À18 years old/all gender | SPM | Descriptive/telephone survey/t-test. Multiple regression analysis | Worsening asthma | Worsening asthma 11–22% Pulmonary function of asthma patients −0.367 p = 0.003 |

| Yang et al.134 | Yang et al. (2005) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/Poisson regression model | Stroke admissions | Hemorrhagic stroke, Lag3 RR 1.15 (1.01–10.10) |

| Yang et al.102 | Yang et al. (2009) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/Poisson regression model | Hospital admissions for congestive heart failure | CHF, Lag1 RR 1.114 (0.993–1.250) |

| Yang et al.116 | Yang et al. (2005) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover studies/Poisson regression model | Daily admissions for asthma | Asthma lag2 8% (p > 0.05) |

| Al et al.86 | Al et al. (2018) | Gaziantep, Turkey | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Retrospective study/GAM | Cardiovascular diseases admitted to ED | Cardiac failure, OR Admission 1.003 (0.972–1.036) P = 0.833 Hospitalization 2.209 (2.069–2.359) P = 0.001 |

| Gyan et al.112 | Gyan et al. (2005) | Caribbean island of Trinidad | Patients aged 15 years and under | – | Ecological/Poisson regression model | Pediatric asthma accident and emergency admissions | Admission rate increased 7.8–9.25 |

| Bennett et al.105 | Bennett et al. (2006) | Lower Fraser Valley, British Columbia, Canada | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Ecological time-series/Chi-squared | Hospital admissions | hospitalizations Respiratory 0.89, χ2 = 0.71 Cardiac 0.91, χ2 = 0.54) |

| Cheng et al.65 | Cheng et al. (2008) | Taipei, Taiwan | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/Poisson regression model | Daily pneumonia hospital admissions | Pneumonia admissions, RR 1.032 (0.980–1.086) Lag1 1.049 (1.002–1.098) Lag2 1.044 (0.999–1.092) Lag3 1.037 (0.993–1.084) |

| Wilson et al.124 | Wilson et al. (2012) | Hong Kong | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/Poisson regression model | Daily emergency admissions for respiratory diseases | COPD, lag2 RR 1.05 (1.01–1.09) |

| Wiggs et al.130 | Wiggs et al. (2003) | Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan | Children/all gender | PM10 | Ecological | Respiratory health | Decreased the rate of respiratory health problems |

| Pulmonary function | |||||||

| Hong et al.162 | Hong et al. (2010) | Seoul, Korea | Children/all gender | PM2.5 and PM10 | Prospective/linear mixed-effects mode | Pulmonary function of school children | PM2.5 (P > 0.05) PM10 (P > 0.05) |

| Kurai et al.157 | Kurai et al. (2017) | Yonago, Tottori, western Japan | School children/adults | PM2.5 | Descriptive/longitudinal /Linear mixed models | Respiratory function | Lag0, −1.76 (−3.30, −0.21) Lag0–1, −1.54 (−2.84, −0.25) Lag0–2, −1.05 (−2.21, 0.11) Lag0–3, −1.09 (−2.18, −0.01) |

| Watanabe et al.161 | Watanabe et al. (2016) | western Japan | Schoolchildren | SPM | A panel study/linear mixed models | Pulmonary function | Peak expiratory flow (PEF) −3.62 (−4.66, −2.59) |

| Watanabe et al.66 | Watanabe et al. (2015) | western Japan | Schoolchildren | SPM | Longitudinal follow-up study/linear mixed models | Pulmonary function | PEF 2012 −8.17 (−11.40, −4.93) 2013 −1.17 (−4.07, 1.74) |

| Yoo et al.160 | Yoo et al. (2008) | Seoul, Korea | Children | PM10 | Prospective/Pearson correlation tests/paired t-test | Respiratory symptoms and peak expiratory flow | PEF decreased (p < 0.05) |

| Watanabe et al.158 | Watanabe et al. (2016) | Western Japan | Aged 18 years | SPM | Panel study/linear mixed models | Pulmonary function | PEF, in allergic patients with Asthma _16.3 (_32.9, 0.4) P = 0.06 Rhinitis _7.0 (_19.5, 5.5) P = 0.27 Conjunctivitis _3.9 (_38.8, 30.9) P = 0.83 Dermatitis _5.6 (_21.3, 10.2) P = 0.49 Food allergy 0.4 (_23.3, 23.9) P = 0.98) |

| Watanabe et al.159 | Watanabe et al. (2015) | Western Japan | Aged >18 years | SPM | Panel study study/linear regression analysis | Pulmonary function in adult with asthma | PEF 0.01 ( −0.62, 0.11) |

| Park et al.163 | Park et al. (2005) | Incheon, Korea | Ages of 16 and 75 years/ all gender | PM10 | Cohort/t-test/GAM with Poisson log-linear regression | Peak expiratory flow rates and respiratory symptoms of asthmatics | PEF 1.05 (0.89–1.24) |

| O’Hara et al.166 | O’Hara et al. (2001) | Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan | Children aged 7 to 11 | PM10 | Cross-sectional survey/multivariate regression model | Lung function | There was an inverse relationship between dust event and Lung function |

| Other impacts | |||||||

| Lee et al.168 | Lee et al. (2019) | Korean national | All ages/all gender | PM10 | Case-crossover/conditional logistic regression | Risk of suicide | Suicide risk, 13.1% (4.5–22.4) P = 0.002 |

| Soy et al.106 | Soy et al. (2016) | Mardin, Turkey | All gender/18 to 65 years | PM10 | Prospective study/pairs t-test | Quality of life(QoL) in patients with or without asthma | QoL, AR 2.5-fold higher SF-36, AR 1.9-fold higher |

| Islam et al.167 | Islam et al. (2019) | Saudi Arabia | All ages/all gender | – | Ecological/panel regression models | Road traffic accidents | P ⩽ 0.05 |

| Mu et al.117 | Mu et al. (2010) | Choyr City, Mongolia | 44.2 ± 17.3/all gender | – | Cross-sectional/student’s t-test/multiple regression analysis | Health-related Quality of Life | Decreased HRQL P < 0.05 |

| Sing and symptom | |||||||

| Higashi et al.151 | Higashi et al. (2014) | Japan | Aged 23–84 years all gender |

PM2.5 | Panel study/logistic regression with a generalized estimating equation | Daily cough occurrence in patients with chronic cough | Grade 1, 1.111 (0.995, 1.239) Grade 2, 1.171 (1.006, 1.363) Grade 3, 1.357 (1.029, 1.788) Grade 4, 1.414 (0.983, 2.036) |

| Higashi et al.152 | Higashi et al. (2014) | Kanazawa, Japan | Between 23 and 84 | TSP | Cohort study, McNamara’s test | Cough and allergic symptoms in adult with chronic cough | Cough p = 0.02 |

| Watanabe et al.67 | Watanabe et al. (2012) | Japan | Age 63.4 ± 15.2/all gender | SPM | Descriptive telephone survey/multivariate logistic regression analysis | Lower respiratory tract symptoms in asthma patients | Exacerbation 4% Unaffected 48% |

| Otani et al.153 | Otani et al. (2011) | Yonago, Japan | all gender/mean age of 36.2 ± 12.5 years | SPM | Ecological Time-series/t test/Pearson’s correlation coefficient | Daily symptoms | All symptoms (p = 0.020) Skin symptom (p < 0.001) |

| Onishi et al.154 | Onishi et al. (2012) | Yonago, Japan | All gender/mean age-SD: 36.2–12.5 years | SPM | Prospective/Wilcoxon’s rank test | Symptom nasal/ocular/respiratory/throat /skin symptoms | All symptom increased |

| Mu et al.35 | Mu et al. (2011) | Mongolia | 35–44/all gender | – | Descriptive studies/cross-sectional study/multiple logistic regression analysis | Eye and respiratory system symptoms | Itchy eye P = 0.3 Bloodshot eye P = 0.02 Lacrimation P = 0.001 Respiratory system P > 0.05 |

| Majbauddin et al.155 | Majbauddin et al. (2016) | Yonago, Japan | Mean age of 33.57 ± 1/all gender | SPM | Prospective web-based survey/student’s t-test | Daily symptoms | Ocular, r = 0.47 (P < 0.01) Nasal, r = 0.61 (P < 0.001) Skin, r = 0.445 (P < 0.05) |

| Kanatani et al.164 | Kanatani et al. (2016) | Kyoto, Tottori, Toyama, Japan | Pregnant women | SPM | Observational study/Cohort/conditional logistic regression analysis | Allergic symptoms | Allergic symptoms, OR 1.10 (1.04–1.18) |

| Yoo et al.160 | Yoo et al. (2008) | Seoul, Korea | Children | PM10 | Prospective/Pearson correlation tests/paired t-test | Respiratory symptoms in children with mild asthma | Cough 42.9 ± 20.8 (p < 0.05) Runny/stuffed nose 53.8 ± 19.2 (p < 0.05) Sore throat 24.2 ± 13.5 (p < 0.05) Eye irritation 24.5 ± 18.1 (p < 0.05) Limited physical activity 16.2 ± 12.5 Nocturnal awakening 15.7 ± 14.1 Shortness of breath 20.1 ± 13.8 (p < 0.05) Wheeze 16.7 ± 7.1 (p < 0.05) |

| Watanabe et al.159 | Watanabe et al. (2015) | Western Japan | Aged >18 years | SPM | Panel study/linear regression analysis | Respiratory symptoms in adult patients with asthma | All symptom 0.04 (0.03, 0.05) |

| Park et al.163 | Park et al. (2005) | Incheon, Korea | Ages of 16 and 75 years/all gender | PM10 | Prospective study/t-test/GAM with Poisson log-linear regression | Respiratory symptoms of asthmatics | Nighttime symptoms RR 1.05 (0.99–1.17) |

| O’Hara et al.166 | O’Hara et al. (2001) | Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan | Children aged 7 to 11 | PM10 | Descriptive studies/cross-sectional survey/multivariate regression model | Respiratory symptoms and lung function | There is an apparent inverse relationship between total dust exposure and respiratory health |

| Watanabe et al.165 | Watanabe et al. (2011) | Western Japan | At least 18 years old | SPM | Cross-sectional telephone survey/multivariate logistic regression analysis | Worsening asthma | Aggravated lower respiratory tract symptoms in asthma patients |

| Meo et al.156 | Meo et al. (2013) | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | Age 28.6 ± 3.14 years/ all gender | – | Descriptive studies /Chi square test | General health complaints | OR Wheeze 4.18 (2.36–7.41) Cough 4.13 (2.28–7.46) Acute asthmatic attack 6.7 (4.09–10.99) Psychological disturbances 3.72 (2.48–5.57) Eye irritation/redness 7.89 (4.4–14.16) Headache 4.17 (2.8–6.2) Body ache 1.24 (0.82–1.88) Sleep disturbance 4.16 (2.77–6.22) Runny nose 31.9 (14.33–70.96) |

Abbreviations: ρ, Spearman correlation coefficients; AOD, aerosol optical depth; AMI, acute myocardial infarction; ACS acute coronary syndrome; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; GAM, generalized additive model; IHD; ischemic heart diseases; IR, increase risk; OR, odds ratio; PM, particulate matter; PM10, particles less than 10 μm in aerodynamic diameter; PM2.5, particles less than 2.5 μm in aerodynamic diameter; PM2.5-10, particles with an aerodynamic diameter >2.5 µm and <10 µm; PTB, pulmonary tuberculosis; QoL, quality of life; RR, relative risk; SPM, suspended particulate matter; TSP, total suspended particulate.

The current results showed that most data analyses investigated the effects of dust storms on health and used the generalized additive model (GAM) with nonlinear Poisson regression method to analyze the data in ecological and case-crossover studies.

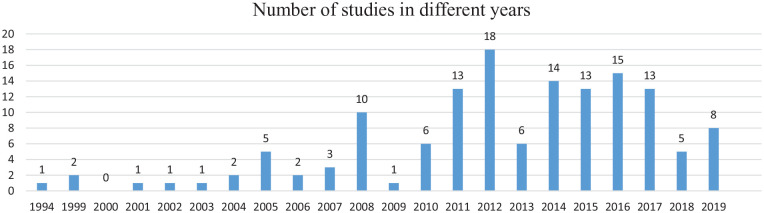

Furthermore, most studies on the impact of dust storms on health were performed within the last decade (Chart 1).

Chart 1.

Number of studies of the impact of dust storms on health in different years.

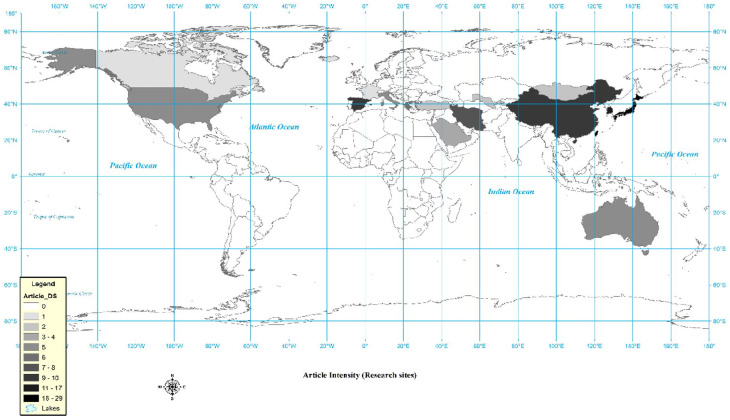

Most health and dust storm studies included in this study were undertaken in Japan (n = 29; 20.71%), Taiwan (n = 25; 17.85%), Korea (n = 16; 11.42%), China (n = 10; 7.14%), Spain (n = 9; 6.42%), and Iran (n = 8; 5.71%), respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Locations of dust storms and health impact research, 1994–2019.

In this review, the following adverse health effects of dust storms emerged as important:

Non-accidental death (mortality due to respiratory, cardiovascular, or cerebrovascular disease);

Emergency medical dispatch, hospitalization or admission, and hospital visits due to respiratory or cardiovascular diseases;

Daily symptoms such as nasopharyngeal, skin, or ocular symptoms, and decreased pulmonary function Table 1).

The current analysis indicated that the effects of dust storms on health can be divided into 2 general sections: short- and long-term effects. Short-term effects have been defined herein as human health problems that occurred during or immediately after a dust storm, and long-term effects are defined as human health problems that occurred after a long exposure to several periods of dust storms.

Short-Term Health Effects

The short-term effects included all-cause mortality, emergency dispatch or air medical retrieval service, hospitalization or admission, healthcare visits, daily symptoms, decreased pulmonary function, and other problems.

Mortality

Thirty-three articles from almost all regions discussed mortality due to dust storms by means of different health problems, such as increased total non-accidental deaths,3,38,39,41,46,53-55,68-82 cardiovascular deaths,3,38,39,48,50,53,70,74,77,82-85 mortality due to acute coronary syndrome (ACS),3,70,81,86 and respiratory mortality.48,53,55,77,87 Some studies reported, however, that the number of cases was not increased significantly for all-causes,43,88 respiratory,38,43 cardiovascular,43 or cerebrovascular mortality.69 Neophytou et al.82 in Nicosia reported that associations for respiratory mortality was −0.79 (−4.69, 3.28) on dust storm days. Lee et al.55 in Taipei found that dust storms have a protective effect on non-accidental deaths, respiratory deaths, and death in people >65 years of age.

Emergency dispatch or air medical retrieval service

Four articles discussed the emergency medical services required due to dust storm, focusing on different health problems. This review observed an increased relative risk of all medical emergency dispatches and a significant increase in cardiovascular dispatches,42 increased daily ambulance calls due to respiratory, cardiovascular, and all causes,89 and an increase in emergency dispatches due to cardiovascular, respiratory, injury and all causes.90

Hospitalization or admission

Sixty-two articles from almost all regions discussed hospitalization or admission due to dust storms by means of different health problems or diseases. The results indicated that in many studies, dust storms were associated with an increased risk of hospital admission due to cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and respiratory diseases, among others.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) hospitalizations or admissions

In relation to cardiovascular diseases and the effect of dust storms, 17 studies stated that dust storms can increase: (1) the risk of circulatory outpatients and inpatients91; (2) odds ratio of admission and hospitalization due to congestive cardiac failure86 and acute coronary syndrome2,86; (3) effects on cardiac diseases92; (4) risk of CVD hospitalization or admission40,78,93-97; (5) emergency admissions for CVD92; (6) the impacts on acute myocardial infarction (AMI)98-100; (7) emergency hospital admissions for ischemic heart diseases (IHD)101; (8) hospital admissions for congestive heart failure (CHF)102; and (9) inpatient hospitalization due to cardiac failure.86 However, some studies reported non-significant results, such as no association between dust storms and out-of-hospital cardiac arrests103 and no significant changes in admissions concerning cardiovascular syndromes.104 Also, some reported no significant association between increased dust particles and angina.50 Bennett et al.105 reported that the dust storms were not associated with an excess of CVD hospitalizations.

Respiratory disease hospitalizations or admissions

Regarding respiratory diseases related to dust storms, 35 studies stated that dust storms can increase the risk of respiratory outpatients,91 respiratory disease hospitalizations or admissions,11,40,43,51,57,78,92,93,96,104,106-114 cases of bronchial asthma,93 asthma-related hospitalizations or admissions,51,57,112-116 cases of aggravated asthma disease,117,118 daily pneumonia admissions,119,120 hospital admissions for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),50,87,121-123 emergency hospital admissions for COPD,124 emergency admissions for respiratory diseases,92 admitted patients suffering from respiratory infection,50 and the prevalence of chronic bronchitis, cough, and rhinitis.125

Surprisingly, several studies did not find any link between dust storms and negative health outcomes, such as no significant effect on asthma exacerbations in Riyadh,126 no significant change in the risk of emergency admission in dust events,127 and no association between sandstorms and risk of hospital admission for asthma or pneumonia patients.56 Moreover, some studies reported no statistically significant relationship between increased dust levels and pulmonary function, allergic disease, emergency admission, or drug use128; no significant relationship between increased risk of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, and angina and increased concentration of dust storms50,129; And no excess risk of respiratory hospitalizations.105 Only two studies found a decrease in respiratory problems after dust storms, like a decreased risk of respiratory inpatients in Taklimakan Desert,91 and a lower rate of respiration problems among children in areas with higher levels of dust deposition as reported by Wiggs et al.130

Cerebrovascular diseases hospitalizations or admissions

Regarding the correlation between cerebrovascular diseases and dust storms, 6 studies stated that dust storms can increase the risk of cerebrovascular diseases,40,92 the incidence of athero-thrombotic brain infarction,131 stroke admission rates,132 hospital admissions for epilepsy problems, cerebral ischemic attacks, and various types of headaches,133 and daily intracerebral hemorrhagic (ICH) stroke admissions.134 Bell et al.,56 however, reported that sandstorms have no significant relationship with the risk of admission to cerebrovascular patients. Moreover, Yang et al.134 stated that there is no significant association between the risk of ischemic stroke and dust storms.

Other diseases hospitalizations or admissions

Aili et al.91 reported that the risk of digestion outpatients and inpatients, gynecology outpatients, pediatrics outpatients and inpatients, and ENT outpatients and inpatients was increased during dust storms. Chan et al.135 also stated that dust storms were significantly associated with diabetes admissions for females. Furthermore, Ko et al.137 stated that dust storms can increase the risk of conjunctivitis.

Healthcare visits

Nineteen articles studied the daily number of healthcare visits due to dust storms for different health problems. Except for 1 article, all others reported that dust storms are associated with an increased daily number of healthcare visits due to asthma-related health problems137-141 cardiac, respiratory, and stroke diagnoses,142 emergency healthcare visits for IHD, CVD, and COPD,143 conjunctivitis clinic visits,144,145 children clinic visits for respiratory problems,139,146 healthcare visits for respiratory diseases,52,139,146,147 healthcare visits for all causes, circulatory, and respiratory diseases,148 and for cardiovascular and respiratory problems.149,150 Lorentzou et al.122 also reported a large increase in emergency visits related to dyspnea during dust storms; however, no clinically significant increase was observed in the total number of emergency visits.

Daily symptoms

Twenty articles studied the daily symptoms resulting from dust storms. In 2 studies, Higashi et al.151,152 showed the effects of Kosa on cough. Otani et al.153 found that the scores for symptoms (nasopharyngeal, ocular, respiratory, and skin) were significantly higher when related to dust storms. Onishi et al.154 reported that all symptoms (nasal, ocular, respiratory, throat, and skin) increased after exposure to dust storms. Mu et al.35 also reported that an increased risk of eye lacrimation occurrence is associated with dust events. Majbauddin et al.155 reported a positive correlation between the increased concentration of dust storms and ocular, nasal, and skin symptoms. Similarly Meo et al.156 observed that sandstorms can increase complaints of sleep and psychological disturbances as well as other problems like eye irritation, cough, wheeze, headache, and runny nose.

Pulmonary function

Nine articles discussed pulmonary function in relation to dust storms, and the evidence is conflicting. Kurai et al.,157 Watanabe et al.,158,159 Yoo et al.160 and Watanabe et al.161 all found that dust storms have a significant, negative effect on pulmonary function. Other studies, including Hong et al.,162 Watanabe et al.159 and Park et al.163 found no significant relationship between pulmonary function and dust storms. Kanatani et al. found that dust storms can increase the risk of allergic symptoms in pregnant women.164 Yoo et al.,160 reported a significant increase in respiratory symptoms during dust storms, and Watanabe et al.159 reported that sand and dust storms are significantly associated with respiratory symptoms. Moreover, Park et al.163 reported a relationship between nighttime symptoms and particular matter levels during dust storms. Watanabe et al.165 also stated that dust storms worsen respiratory symptoms in asthmatic patients, but some studies like O’Hara et al.166 reported that pulmonary function was better in children who were more exposed to dust storms than in those with low exposure to dust.

Other impacts

Some articles explored the relationship of dust storms with road traffic accidents, risk of suicide, placental abruption, and health-related quality of life. Islam et al.167 found that sandstorms and the number of vehicles were significantly responsible for road traffic accidents. Soy et al.106 reported that dust storms can have adverse effects on the quality of life of patients with asthma and allergies. Mu et al.117 reported that dust storms can decrease health-related quality of life in everyone exposed to them. Lee et al.168 reported that exposure to dust storms was associated with an increased risk of suicide (13.1%; p = 0.002).

Long-Term Health Effects

Six articles discussed the long-term adverse health effects caused by dust storms by means of different outcomes, like reduced birth weight, baby’s birth weight <2.5 Kg, gestation/gestational age >37 weeks and premature birth,32 and decreased cognitive function in children.33 Preterm births34 were correlated with Valley fever incidences36 and increased spring measles incidence.44 Only one article was observed to indicate no significant effect of desert dust storms on pregnancy consequences.169

Discussion

In this study, the majority of valid scientific databases were searched to find articles and studies related to the health effects of dust storms. Other similar studies have used fewer scientific databases in their search. The final number of articles included in this study is higher than that in all previous studies.24,26 The current results showed that the model most used to evaluate the health effects of dust storms was the GAM method. In this regards, Ramsay 2003 stated, “Such methods eliminate the need to specify a parametric form for secular trends and allow a greater degree of robustness against model misspecification.”170 The results of the current study also showed that most dust storm studies have been carried out in Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea, which may be due to the large number of dust storms occurring in Northeast Asia. This area is exposed to yellow dust storms caused by strong winds on the Loos Plateau and the Gobi and Talkmanistan Deserts, and as yellow dust storms became so prevalent in that area within the last two decades, researchers in the area have studied their health effects.152,171

The review results showed that most studies around the world confirm the adverse effects of dust storms on health. The relevant health problems were categorized into long-term and short-term impacts. Few studies were found that focused on the long-term impacts of dust storms on human and public health; however, those studies found showed that dust storms may increase the risks for problems in pregnancy and childbirth, children’s cognitive problems, and infectious diseases. In line with the risks of birth as well as cognitive problems in children, animal studies have shown that the fetal brain is easily exposed to air pollutants, because in the human fetus, the blood-brain barrier has not yet developed; therefore, the fetal brain is exposed to pollutants and is sensitive to blood changes caused by them.1-3 Furthermore, new research on humans has shown that environmental pollutants can possibly create inflammation, oxidative stress, and vascular damage to the fetal brain after passing through the placenta.4-7 Researchers have studied the effects of PM from dust storms on maternal health during pregnancy and birth problems, and they refer to variations in maternal host-defense mechanisms, maternal-placental exchanges, oxidative pathways, and endocrine dysfunction as possible causes of these problems.8 Ultimately, the evidence from infectious diseases shows that pathogenic microorganisms are abundant in dust storms,9 and dust storms can spread these microorganisms over a large area. Therefore, it can be argued that microorganisms that are suspended or attached to dust particles can be transferred from one part to another and may induce infectious diseases at various destinations by dust storms.10,11 More studies have been conducted on the short-term impacts of dust storms. The majority of these studies indicate the effects of dust storms on important body systems, including the cardiovascular, respiratory and cerebral systems, which lead to the increased incidence of clinical symptoms and severity of symptoms; increased emergency visits, ambulance dispatches, and hospitalizations or admissions; decreased lung capacity; and eventually death.

Most studies show that dust storms increase the risk of cardiovascular problems, the number of cardiovascular emergency medical dispatches, cardiovascular visits, the number of cardiovascular symptoms among patients referring to the hospital, cardiovascular admissions or hospitalizations, and deaths due to cardiovascular disease. Although the exact mechanism for the effects of dust storms on heart problems has not yet been determined,12 studies show that fine particles in dust storms can enter lung tissue and the bloodstream through chemical interactions,13 causing a thrombolytic and inflammatory process and the secretion of cytokines in the body.14,15 Moreover, the toxicity of some of these substances in the body reduces the contractibility of the heart, increases vasoconstriction, and increases blood pressure.14,18-20 Therefore, the above cases may confirm the effects of dust storms on cardiovascular health.

The results of the current study showed that according to most articles, the risk of death following respiratory problems; the risk of admission and hospitalization due to respiratory disorders like pneumonia, asthma, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and other respiratory problems; respiratory symptoms; and healthcare visits associated with dust storms have increased. Other results showed that dust storms reduce lung capacity and function.

The results of studies have shown that 1 mechanism of dust storms is that small particulates in dust storms are likely to trigger an innate immune response by T-lymphocytes in the body and respiratory system, which can cause chronic inflammation and advanced COPD.22-25 PM can also play a significant role in respiratory oxidative stress, increase pulmonary inflammation, increase atopic responses and Immunoglobulin E production in respiratory problems (especially asthma), and exacerbate symptoms.26 Another mechanism that may cause respiratory illnesses following a dust storm is the presence of pathogens such as microorganisms and fungi37 as well as some minerals such as silica in some of these storms. These particles enter the airway after dust storms and exacerbate the disease or cause respiratory problems in people at risk.22 For example, neutrophilic pulmonary inflammation may be caused by bacterial and fungal debris in dust particles to which individuals are exposed. Some of this debris includes lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a cell wall glycolipid of gram-negative bacteria, and β-glucan, which is the most important constituent of the fungal wall. Both of them are clearly observed in dust storms along with dust particles.22,38,39 Although the precise mechanisms for pneumonia are yet to be found, some studies have suggested that high amounts of particles in dust storms can cause oxidative stress, induce inflammation, increase blood clotting, disrupt defense cells, and cause immune system fluctuations, ultimately inducing alveolar inflammation and exacerbating lung disease.3,40,41

In 2009, Calderon Garosia stated that pollutants in dust storms can cause problems such as cardiovascular, respiratory, liver, and skin toxicity through systemic inflammation42 and may induce a pre-inflammatory systemic response in cytokines, which may disrupt the HPA axis and ultimately cause mood swings and psychological problems, including suicidal thoughts.42-44 In addition, chemical components found in dust storms can enter the brain through the mucosa and olfactory system.42 After entering the nervous system, they may accumulate in the anterior cortex of the brain and cause problems in emotional regulation and impulse control.45 Some researchers also suggest that some mechanisms are associated with placental abruption due to dust storms, such as microbiological and chemical substances in dust storms that induce an inflammatory response in the body.46,47 Inflammation and ischemia increase the risk of decidual bleeding, followed by hematoma formation and placental abruption.48,49 There is also some speculation that as lipopolysaccharide has been found in Asian dust storms, the activity of this endotoxin in the body may lead to premature birth due to chorioamnionitis, which is also associated with placental abruption.50,51

The current review shows that some studies have also linked dust storms with some other health problems, such as increased road accidents, increased suicide risk, increased premature placental abruption, ocular problems, and reduced quality of life. These issues could be further studied in areas prone to dust storms. Islam11 stated that the reduced field of vision, the lack of dust storm warning systems, and traffic due to dust and sand storms can be considered as reasons for the recent increase in number of road accidents. Dust particulates in these storms can also cause acute ocular problems such as tears and conjunctivitis in people due to their inflammatory effects.52 I In terms of the quality of life, Mu53 stated that an increase in health problems and clinical symptoms that are associated with allergens and ocular problems such as conjunctivitis dust storms reduce the quality of life.

Despite all the significant effects of dust storms on health, this review found some studies that presented no significant association between dust storms and health problems including all-cause and respiratory mortality,43,88 cardiovascular,103-105 cerebral,134 and respiratory problems.127-129 Moreover, some studies reported that dust storms may have a protective effect against non-accidental and respiratory death55 and other pulmonary problems.91,130,166

However, O’Hara stated that although the lack of matching of exposed and non-exposed groups in nutritional, economic, and social problems may play a role in the insignificance of the effects of dust storms on health, the chemical and physical nature of the particles in dust storms are of more importance than their total amounts.55,166 Differences in the chemical and physical nature of particulate matters may cause different health outcomes in varying regions.55 Another reason for the difference may be the use of rapid early warning systems in some countries. Lee justified the protective effects of dust storms on death, stating that in Taipei, a complex rapid early warning system is used for dust storms, and the use of this system may produce protective effects of dust storms on mortality.55 Finally, almost all of the reviewed articles reported on a group of diseases or deaths that were studied, while dust storms may not affect all diseases and deaths.22 This may be another reason for these differing results.

Conclusion

This systematic review presents an accurate and comprehensive study of all aspects of human health in relation to dust storms. For the first time in the world, this in-depth and unique study was conducted to summarize the short-term and long-term effects of dust storms. To date, this amount of reliable data on this issue has never been investigated. As the results showed, despite the short-term effects dust storms have on human health (including adverse effects on the respiratory, skin, ocular, cardiovascular, and cerebral systems as well as increased mortality and morbidity) that may occur immediately after each dust storm, the frequency of dust storms in an area is also an important factor. In addition to exacerbating short-term health effects, they may also cause long-term health effects, which may include health problems for pregnant mothers, fetuses and infants, in the cognitive function of children, and increases in some infectious diseases. Therefore, as climate change and drought have caused this phenomenon to endanger the lives of many people around the world, and as the health and well-being of people is a main priority in any country, it is recommended that more studies be conducted in countries exposed to dust storms to examine the health effects of these storms in order to better understand the mechanisms through which dust storms impact human and public health and to develop a better strategy for preparing for, preventing, and mitigating the destructive effects of these storms.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Institute for School of public health and Environmental Research (IER) of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS), for supported current study.

Footnotes

Funding:The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study is a part of PhD dissertation and was funded and supported by School of public health and Center for air pollution research (CAPR), institute for environmental research (IER), Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, Grant No: 98-03-46-43717.

Declaration of conflicting interests:The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Author Contributions: “HA and AOT designed the study; HA collected the data; HA and AOT analyzed and interpreted the data. HA, AOT, A Ardalan, MA, MY, CS and A Asgary prepared the manuscript. All authors contributed to the drafting and final review of the manuscript. The author (s) read and approved the final manuscript.”

Ethical Approval: Current study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Tehran University of Medical Sciences (TUMS) Ethics Code: IR.TUMS.SPH.REC.1399.004, and also all methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

ORCID iD: Hamidreza Aghababaeian  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3339-5507

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3339-5507

References

- 1. Shao Y, Wyrwoll K-H, Chappell A, et al. Dust cycle: an emerging core theme in Earth system science. Aeolian Res. 2011;2(4):181-204. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Vodonos A, Friger M, Katra I, et al. Individual effect modifiers of dust exposure effect on cardiovascular morbidity. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0137714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]