Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The oncology nurse practitioner (ONP) role has evolved since the first ONP competencies were published by the Oncology Nursing Society in 2007. An update was completed in 2019 to reflect the rapidly expanding role.

OBJECTIVES:

The purpose of this article is to describe the process of the ONP competency development and identify potential applications across a variety of oncology settings.

METHODS:

The team performed an extensive literature review of the research about ONP practice across the cancer care continuum. Peer and expert review were conducted to ensure the competencies were comprehensive and relevant.

FINDINGS:

The ONP competencies provide a solid, evidence-based benchmark to standardize the ONP role and practice, thereby ensuring that patients receive the highest-quality cancer care.

Keywords: oncology nurse practitioner, competencies, oncology setting, best practices

nurse practitioners (nps) provide a significant amount of cancer care in the United States. Of the more than 270,000 licensed NPs in the United States, about 3,600 to 4,800 provide cancer care (Bruinooge et al., 2018; Coombs et al., 2019). As a result of the increasing number of patients who receive a cancer diagnosis, oncology NPs (ONPs) have an increased presence across multiple clinical settings (e.g., ambulatory, inpatient, urgent care, survivorship). ONPs make a unique contribution to cancer care, bridging the nursing and medical realms to provide patient-centered care.

Professional associations, such as the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS), support standardized practice by setting quality benchmarks, including competencies, and providing context to nurses’ roles (American Nurses Association, 2014). ONS has defined competencies for nurses in various roles in oncology, including competencies for NPs, clinical nurse specialists, and generalist nurses.

The first competencies for ONPs were published by ONS in 2007. Because the ONP role has evolved continuously since then, the competencies were revised following an NP summit held in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in December 2017. The summit provided a forum for reflection of ONP practice, including a recommendation for revision of the competencies (Mackey et al., 2018).

Process of Competency Development

The ONP competency team convened in January 2019 and included ONPs with clinical expertise in medical oncology, hematology, prevention, wellness, survivorship, clinical trials, and research. The team members provided care in multiple institutions and settings across the United States and included representation from the northeastern, southeastern, southern, midwestern, and western regions. A representative from the Advanced Practitioner Society for Hematology and Oncology (APSHO) joined the team early in the process.

The ONP competency team began with an extensive literature review to identify appropriate research about ONP practice across the cancer care continuum. The search included all relevant literature through January 2019 and used the following keywords: oncology nurse practitioner, clinical practice, education, competence, competency, diagnosis, health care, interventions, prevention, screening, survivorship, scopes and standards, and treatment. Data sources included PubMed®, CINAHL®, Ovid, MEDLINE® on OvidSP, and Google Scholar™. The findings of each article were reviewed, critiqued, and graded for applicability.

Based on the literature search results, the team established classifications for competency categories, using the structure from the ONS publication Oncology Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice (Lubejko & Wilson, 2019). Competency statements that reflected the literature on ONP practice across various geographic and clinical settings were developed. Through a paired review process, team members reviewed and revised statements to establish the initial competencies. The public comment period occurred between April and May 2019, and feedback was provided through a web-based survey tool. Emails were sent to all ONS members who self-identified as an NP or an advanced practice RN. APSHO members were also invited to review by email. Public comment solicitation offered the opportunity to review the competencies and offer comment. Feedback was evaluated by the team and incorporated into the competencies.

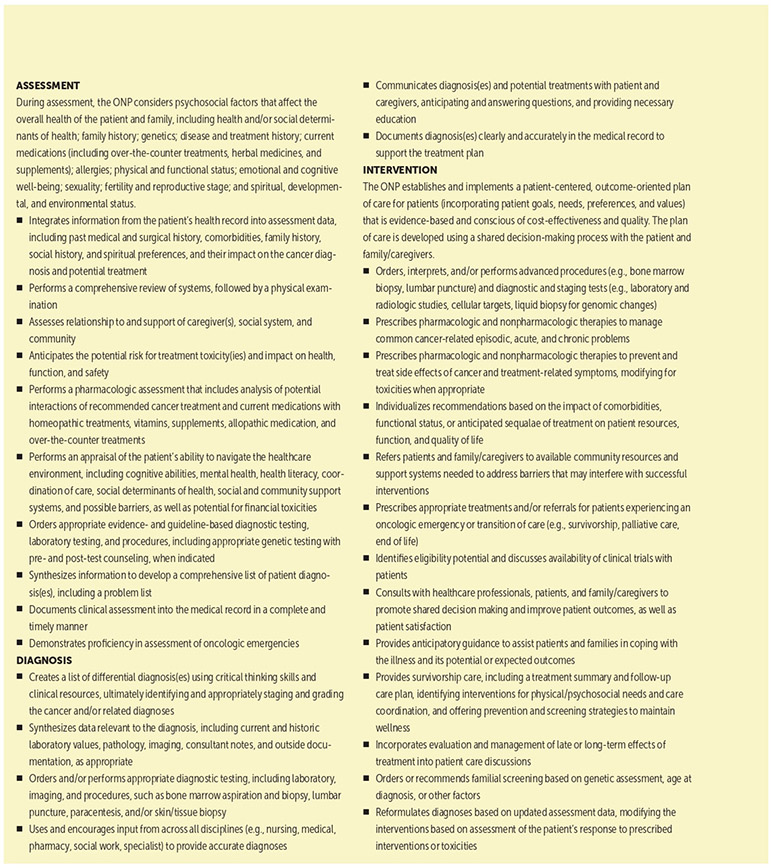

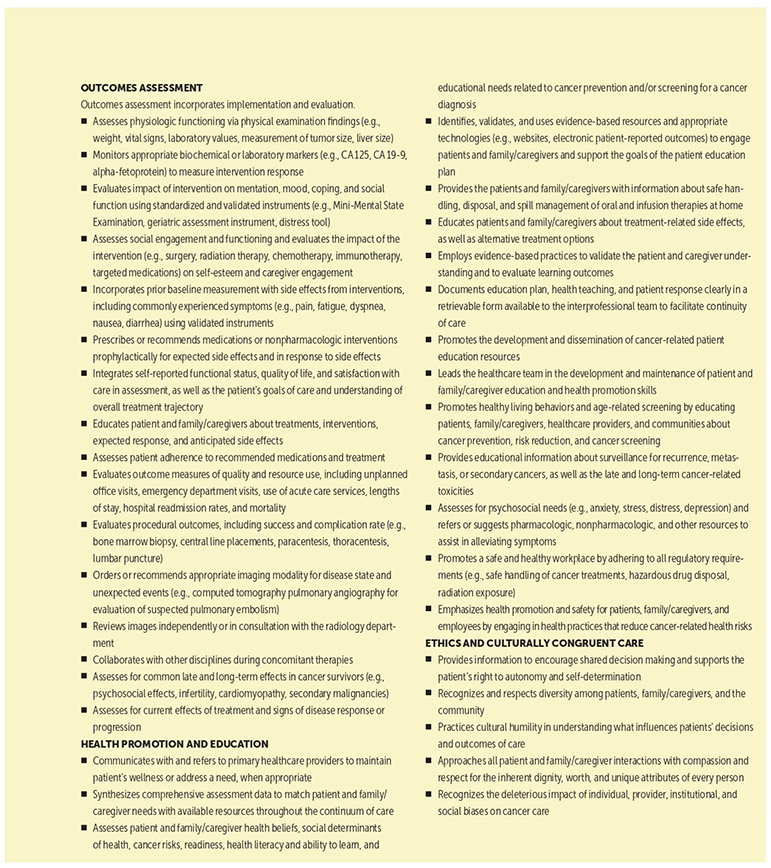

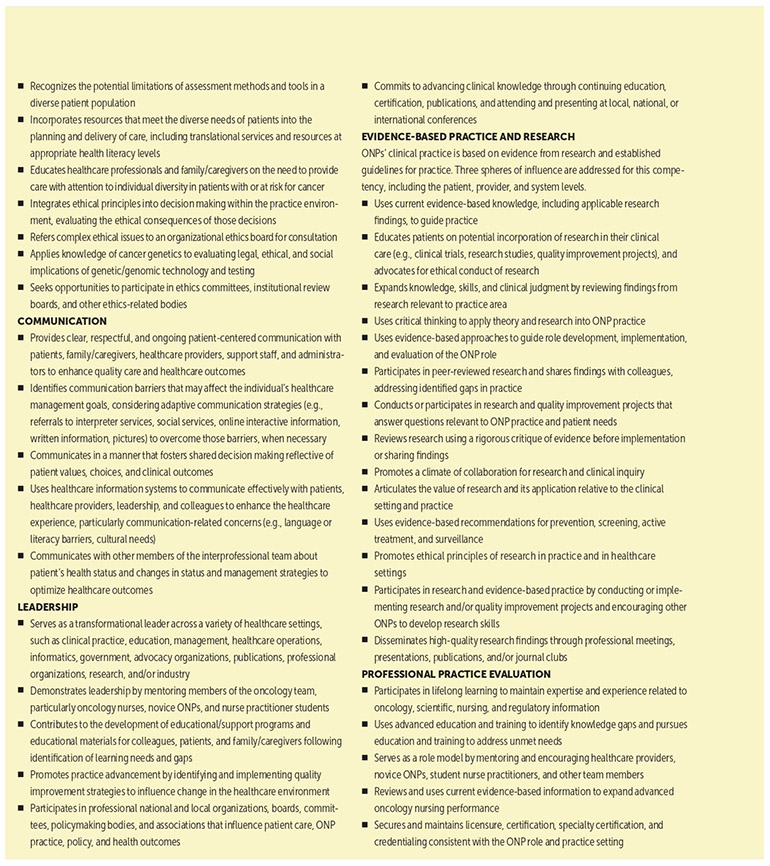

A second content review was conducted by five clinical experts within the field of ONP practice. These experts were selected for their experience and were asked to comment on the appropriateness, clarity, completeness, and flow of the overall competencies. Additional edits, based on their responses, were made; the final competencies consisted of 12 categories and 121 competencies (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. ONP COMPETENCIES.

ONP—oncology nurse practitioner

Note. From “Oncology Nurse Practitioner Competencies 2019,” by Oncology Nursing Society, 2019 (https://bit.ly/2z2j3EY). Copyright 2019 by Oncology Nursing Society. Reprinted with permission.

Competency Application

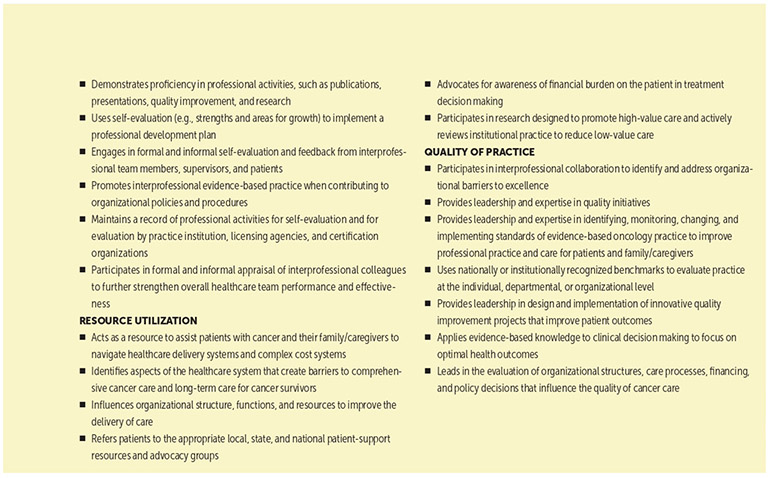

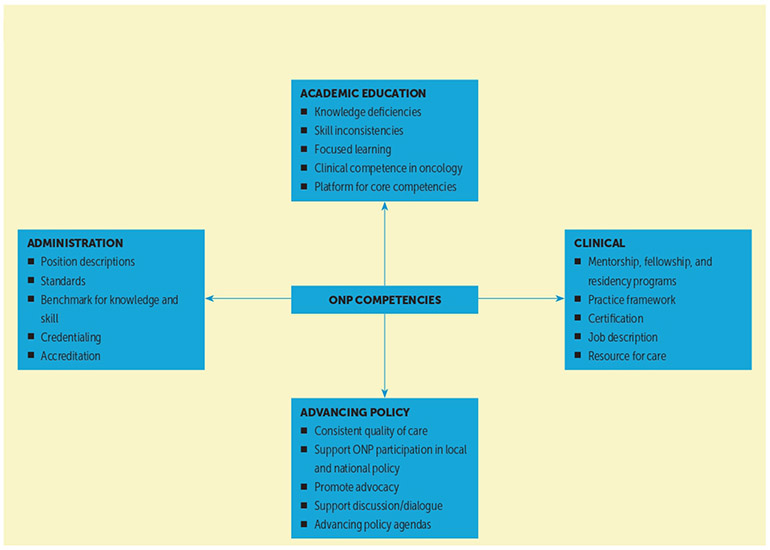

National associations and regulatory bodies have established requirements for NP practice (American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 2019; National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties, 2017; National Organization of Nurse Practitioners & American Association of Colleges of Nursing, 2016). These ONP competencies provide a detailed description of ONP practice that is applicable across a variety of settings, including education, clinical practice, administration, and healthcare policy (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. ONP COMPETENCIES: APPLICABLE DOMAINS FOR PRACTICE.

ONP—oncology nurse practitioner

Education

The ONP competencies define oncology practice and may be used by academic centers to train students in advanced practice programs in the complex world of oncology. The number of cancer survivors is expected to reach 22.1 million by the year 2030 (Miller et al., 2019), and many current nursing trainees will care for a patient with cancer at some point during their career. The ONP competencies provide direction for educators and students outside an oncology setting and provide an outline of responsibilities for patient care in their practice settings.

Competency-based education is equally effective in didactic and self-learning approaches. The identified needs of the learner have proven educational outcomes and have shifted the approach to competency-based education. It is important to recognize the role of the preceptor in the success of competency-based curricula (Schumacher & Risco, 2017). Competency-based education is learner-centered in that outcomes are specified and clearly delineated to support the learner’s success. Given the assortment of individual differences in performance, educators can use these competencies to help evaluate advancement through the educational program.

Academic centers with an ONP fellowship program (or those developing a program) may use the competencies to obtain a pre– and post–fellowship program assessment. A set of guiding principles provides direction for the program curriculum. It is essential that NP graduates have the expected competencies to move into the practice world, regardless of setting. Providing an educationally sound pathway that is competency-based helps to ensure that NPs are providing exceptional care at the top of their level.

Clinical Practice

ONP competencies are best integrated within a clinical practice setting. Building on the core competencies for all NPs (National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties, 2017), the ONP competencies outline the specialized responsibilities of entry-level ONPs caring for patients with cancer across a variety of clinical settings, including acute and ambulatory care. As a member of the interprofessional team, ONPs can define their roles and responsibilities in clinical practice.

The competencies form the basis of the ONP job description, quantifying the skills and basic knowledge necessary for a practicing ONP pursuing employment in oncology by providing a standardized guide for expectations and requirements of a role. For novice ONPs, the competencies will provide a practice framework for which to design educational and clinical practice opportunities, knowledge, and skills to care for a variety of patient populations during their orientation program. Preceptors for ONPs can use the competencies as a training guide as they work with new ONPs to identify goals. Similarly, experienced ONPs can use the competencies to prioritize future educational oncology programs and to guide those pursuing specialty certification as an NP in oncology.

The ONP competencies may be used by NPs in other specialty care areas to improve care delivery. Although the ONP competencies are written for a specialty, they can be used to identify gaps in learning related to many patient needs. All NPs may encounter patients with a diagnosis of cancer who are experiencing side effects of their disease or treatment, including oncologic emergencies, necessitating prompt recognition and early intervention. NPs with an understanding of the impact of cancer and associated treatments on other comorbidities can ensure patient safety and optimal outcomes. Patients with cancer are often seen within a primary care setting.

Primary care providers offer ongoing survivorship care to patients with cancer (Nekhlyudov et al., 2017). These primary care providers require knowledge about cancer assessment and diagnosis, as well as intervention skills related to long-term and late presenting side effects of cancer treatments. All NPs, regardless of specialization or setting, play an important role in cancer screening and early detection. Advances in genetics and genomics and their implication on screening, diagnosis, and treatment require advanced knowledge for all NPs on the genetic implications of cancer and hereditary-based cancer syndromes, as well as an ability to perform general risk assessment and provide appropriate referrals.

Administration

ONP competencies may also be used as part of the credentialing and privileging processes specific to institutional onboarding. Credentialing is defined as “the process of obtaining, verifying, and assessing the qualifications of a practitioner to provide care or services in or for a health care organization” (Joint Commission, 2012, p. 1), whereas privileging is “the process whereby the specific scope and content of the patient care services (that is clinical privileges) are authorized for a health care practitioner by a health care organization, based on an evaluation of the individual’s credentials and performance” (Joint Commission, 2012, p. 1). The ONP competencies establish a basis for the knowledge and skills required of an ONP in caring for people with cancer. They can also be used by interprofessional committees associated with institutions who are charged with revising their prior standardized procedures and protocols.

In addition, the competencies can be used as a part of the performance evaluation process for novice and experienced ONPs to standardize the expectations of the role and provide clarity for evaluation purposes. The ONP competencies may be used as guidelines to develop a position description for an ONP in general, or for oncology practices that have not previously employed an ONP but would like to incorporate one into their practice. Administrators may be able to use the competencies as a benchmark to assess ONP knowledge and skills related to patient-reported outcomes (e.g., symptom management), patient experience, or other measurable patient outcomes (e.g., length of stay, hospital readmissions). The competencies can be used as a foundation for developing specific competencies for a unique oncology department or practice that uses ONPs. Similarly, administrators may use the competencies as a resource to develop a rubric to help clarify performance expectations of new or experienced ONPs, which may decrease confusion regarding the ONP role and help new ONPs transition into practice. The competencies can also be used as a part of the accreditation process for Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) or Magnet, in that administrators may state that all ONPs have met the basic ONS-established ONP competencies to practice at their facility.

Advancing Policy

The Institute of Medicine’s (IOM’s) 2010 report The Future of Nursing: Leading Change, Advancing Health recognized the valuable contribution of NPs within the evolving healthcare environment. The report also suggested that to provide the best care to patients, all healthcare providers should practice to the fullest extent of their education and training (IOM, 2010). The ONP competencies are written to support ONPs across the range of sites and levels of expertise, focusing on the provision of high-value care. Multiple organizations, including CMS and third-party payers, have adopted a reimbursement system that incentivized providing high-quality, value-based care with proven outcomes, shifting previous goals of volume of care toward value of care provided (American Society of Clinical Oncology, 2016). This shifting focus is driven, in part, by the cost of health care. In 2017, about 18% of the gross domestic product was spent on health care, and some of the largest expenditures in health care are hospital care, for 33% of total cost, followed by physician and clinical services, at 20% of total cost (CMS, 2018). The potential to affect policy will increase, given that cancer continues to be a leading cause of death for adults in the United States (Siegel et al., 2019).

The ONP competencies support improved patient outcomes by ensuring consistent quality of care with patients at the center of cancer care delivery. The current healthcare system is rapidly evolving, with ONPs well positioned to increase the magnitude of their contribution to high-quality, cost-effective care (Mason et al., 2013; Nevidjon et al., 2010). Because healthcare policies affect patients, clinicians, and resource allocation, ONPs can and should participate in local and national policy discussions. ONS recognizes the need for quality care throughout the cancer care continuum, as well as the necessity to have current clinic practice reflected within the ONP competencies. These competencies are written to address the needs of patients with cancer and emphasize the importance of ONPs providing safe and high-quality care. The ONP competencies promote patient advocacy by supporting shared decision making among providers, patients, and their families. An additional function of the competencies is to ensure that ONPs approach individual treatment decision discussions with cultural humility and respect for the treatment decision process. The nursing profession has been recognized as one of the most, if not the most, trusted professions by the public for the past 17 years (Brusie, 2020). Because of this trust, nurses, and specifically ONPs, should use their voices in guiding national policy agendas to promote patient care needs today and in the future.

In addition to supporting excellent, high-value patient care, the ONP competencies may also be used to support discussion of legislative policies. The ONP competencies can be used to encourage meaningful dialogue in states seeking legislative changes for regulating NP practice. This expansion is consistent with the IOM goals, as well as with the overall goal of all clinicians: to provide all patients with cancer with access to high-quality cancer care.

Conclusion

Oncology care is complex and becoming increasingly more so because of multiple treatment options and emerging technologies available. ONPs make a unique contribution to cancer care, bridging the nursing and medical realms to provide patient-centered care. The intent of the ONP competencies was to create standardized quality care across a variety of practice and geographic settings, which is essential to the delivery of high-quality clinical cancer care. They can and should be used in the educational and administrative settings to maximize training programs to meet the growing demands of patients in the 21st century, as well as ONP professionals. The ONP competencies can be used when advocating for patients within the legislative and national healthcare policy realm, ensuring that equitable treatment options are available to all patients who need them. The updated ONP competencies will enhance the ability of ONPs to provide quality cancer care and provide much-needed definition of the current role. Recognizing that the ONP role is complicated by federal regulations and scope of practice variability from state to state, as well as educational and institutional differences, these competencies provide a solid, evidence-based benchmark to standardize the role and practice of ONPs.

IMPLICATIONS FOR PRACTICE.

Standardize oncology nurse practitioner (ONP) practice competencies to ensure that all patients receive the highest-quality cancer care.

Provide the framework for the ONP role and responsibilities within an interprofessional cancer care team.

Describe ONP clinical practice across various settings, including clinical practice, academics, administration, and healthcare policy.

Contributor Information

Lorinda A. Coombs, College of Nursing at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Kimberly Noonan, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, MA.

Fedricker Diane Barber, University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Heather Thompson Mackey, Elsevier Clinical Solutions; Cancer Prevention and Wellness at Novant Health Oncology Specialists in Winston-Salem, NC.

Mary E. Peterson, LiveStrong Cancer Institute at Dell Medical School at the University of Texas at Austin.

Tamika Turner, Franciscan Physician Alliance Hematology Oncology Specialists in Indianapolis, IN.

Kristine B. LeFebvre, Oncology Nursing Society in Pittsburgh, PA.

REFERENCES

- American Association of Nurse Practitioners. (2019). NP fact sheet. https://www.aanp.org/about/all-about-nps/np-fact-sheet

- American Nurses Association. (2014, November 12). Professional role competence. https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/nursing-excellence/official-position-statements/id/professional-role-competence

- American Society of Clinical Oncology, (2016). The state of cancer care in America. 2016: A report by the American Society of Clinical Oncology. Journal of Oncology Practice, 12(4). 339–383. 10.1200/JOP.2015.010462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruinooge SS, Pickard TA, Vogel W, Hanley A, Schenkel C, Garrett-Mayer E … Williams SF (2018). Understanding the role of advanced practice providers in oncology in the United States. Journal of Oncology Practice, 14(9), e518–e532. 10.1200/JOP.18.00181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brusie C (2020). Nurses ranked most honest profession 18 years in a row. https://nurse.org/articles/nursing-ranked-most-honest-profession [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2018). National health expenditure data: Historical. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical

- Coombs LA, Max W, Kolevska T, Tonner C, & Stephens C (2019). Nurse practitioners and physician assistants: An underestimated workforce for older adults with cancer. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(7), 1489–1494. 10.1111/jgs.15931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2010). The future of nursing: Leading change, advancing health. https://www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports/2010/The-Future-of-Nursing-Leading-Change-Advancing-Health.aspx

- Joint Commission. (2012, March 25). Credentialing and privileging: Implementing a process. https://www.jointcommission.org/resources/news-and-multimedia/blogs/ambulatory-buzz/2012/03/guest-blogger-virginia-mccollum-credentialing-and-privilegingimplementing-a-process

- Lubejko BG, & Wilson BJ (2019). Oncology nursing: Scope and standards of practice. Oncology Nursing Society. [Google Scholar]

- Mackey H, Noonan, K, Kennedy Sheldon L, Singer M, & Turner T (2018). Oncology nurse practitioner role: Recommendations from the Oncology Nursing Society’s Nurse Practitioner Summit. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing, 22(5), 516–521. 10.1188/18.CJON.516-522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason H, DeRubeis MB, Foster JC, Taylor JMG, & Worden FP (2013). Outcomes evaluation of a weekly nurse practitioner-managed symptom management clinic for patients with head and neck cancer treated with chemoradiotherapy. Oncology Nursing Forum. 40(6), 581–586. 10.1188/13.ONF.40-06AP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller KD, Nogueira L, Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Alfano CM, … Siegel RL (2019). Cancer treatment and survivorship statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 69(5), 363–385. 10.3322/caac.21565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Organization of Nurse Practitioner Faculties. (2017). Nurse practitioner core competencies content. https://www.nonpf.org/resource/resmgr/competencies/2017_NPCoreComps_with_Curric.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- National Organization of Nurse Practitioners & American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2016). Adult-gerontology acute care and primary care NP competencies. https://bit.ly/35CtM5j

- Nekhlyudov L, O’Malley DM & Hudson SV (2017). Integrating primary care providers in the care of cancer survivors: Gaps in evidence and future opportunities. Lancet Oncology, 15(1). e30–e38. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)30570-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevidjon B, Rieger P, Miller Murphy C, Rosenzweig MQ, McCorkle MR, & Baileys K (2010). Filling the gap: Development of the oncology nurse practitioner workforce. Journal of Oncology Practice, 6(1). 2–6. 10.1200/JOP.091072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher G, & Risco K (2017). Competency-based nurse practitioner education: An overview for the preceptor. Journal of the Nurse Practitioner, 13(9), 596–602. 10.1016/j.nurpra.2017.07.020 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, & Jemal A (2019). Cancer statistics, 2019. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 69(1), 7–34. 10.3322/caac.21551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]