Preface to the 2019 Eighth Edition

This booklet contains the eighth edition of the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI) that describes the examination (referred to as the International Standards examination) as well as the classification including the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Impairment Scale (AIS). In this edition, substantial revisions have been made in addition to the 2015 update of the 7th edition. (The key changes made in 2015 are found below.1,2) The revisions in this new edition are based not only upon comments, questions, and suggestions from the international community of spinal cord injury (SCI) clinicians and researchers, but also take into account recently available evidence and structured feedback from ISNCSCI training courses.3,4 Due to the space constraints in this booklet, more details and explanations about each of the revisions will be/are separately published as journal articles.

The following is a summary of the revisions included in this booklet.

-

Documentation of non-SCI-related impairments: Most of the questions received by the International Standards Committee over the last few years were related to the correct documentation of non-SCI-related, pre-existing musculoskeletal or neurological problems. Such problems include among others chronic peripheral nerve injuries, acute or chronic pain, or age-related muscle weakness. In particular, age-related impairments represent a growing problem due to the increasing age of acutely injured persons seen in industrial countries.

In the 7th edition of ISNCSCI, the only method for documentation of non-SCI-related impairments is the use of the “5*” grade in the motor exam. However, no such concept exists for documentation of non-SCI-related sensory deficits function. Additionally, guidelines on how to indicate the presence of “5*”s in classification variables such as levels or the AIS are missing.

To address this issue, a general “*” concept applicable to the motor as well as the sensory exam independent from the level of occurrence (above, at, or below the sensory/motor level) is introduced in this edition: In those cases with non-SCI-related impairments, abnormal sensory and/or motor scores should be scored as examined and tagged with an “‘*” to indicate that a non-SCI condition is impacting the examination results. If an examiner tags a score with the “*”, details on the reason for this and how this “*”-tagged score should be handled during the classification process need to be specified in the Comments box. While “*”-tagged scores above the sensory/motor level will in most cases be handled as normal during classification, “*”-tagged scores at or below the motor/sensory level indicating a non-SCI-related impairment superimposed to the deficit caused by the SCI will typically be handled as not normal. Each classification variable such as levels or AIS, which is affected by the “*”-tagged scores, should also be designated with an “*”. By this method, it is clearly indicated that the classification results are based on clinical interpretation of the recorded scores.

The use of the “5*” grade to indicate that the active movement would be considered normal, if an identified inhibiting factor were not present, is not recommended anymore. Instead, the actual result of the motor examination should be noted, tagged with an “*”, and the inhibiting factor together with the information that this score should be treated as normal during classification should be provided in the Comments box.

-

Zone of partial preservation: The definition of the zone of partial preservation (ZPP) has been revised and extended to incomplete lesions with either missing voluntary anal contraction (VAC) or missing sensory function (deep anal pressure [DAP], light touch and pin prick). Besides the added value for clinical communication purposes, new evidence has become available that the ZPP based on this new definition provides a better prognosis of neurological recovery.5 The ZPP definition has been changed as follows:

“Zone of Partial Preservation (ZPP): This term, used only in injuries with absent motor (no VAC) OR sensory function (no DAP, no LT and no PP sensation) in the lowest sacral segment S4–5, refers to those dermatomes and myotomes caudal to the sensory and motor levels with partially preserved functions. The most caudal segments with any sensory or motor function define the extent of the sensory and motor ZPP respectively and are documented as four distinct levels (R-sensory, L-sensory, R-motor, and L-motor).” (p 17)

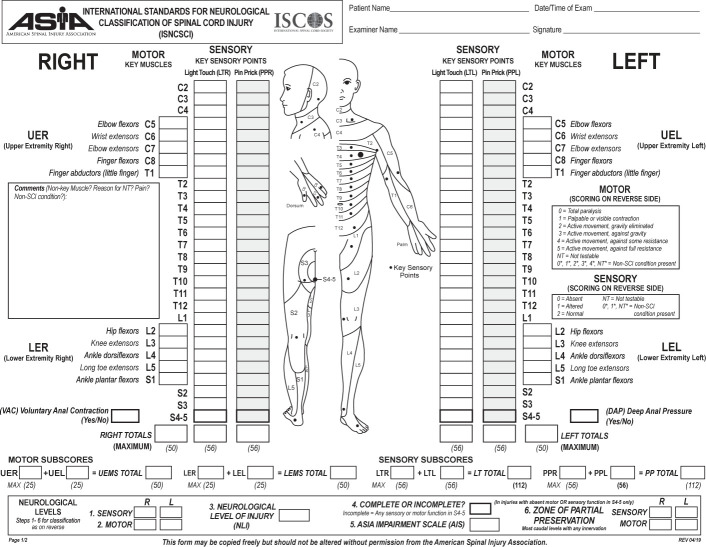

Worksheet: The 2015 worksheet has also been revised and the new 2019 revision added to this booklet. The revised worksheet complies with the new ZPP definition (step 6 in the Steps for Classification on the backside of the worksheet) and with the taxonomy for documentation of non-SCI-related impairments. Additionally, some minor format changes such as alignment of the boxes for the sum scores have been implemented. The format changes introduced in 2013 with grouping of the examination modalities according to the body side were found to result in higher classification accuracies compared to older versions6 and were therefore maintained [see worksheet].

Patterns of incomplete injury: In the 2015 update, clinical syndromes in incomplete lesions were listed at the end of the booklet. The Committee thought to move these syndromes to the introduction to emphasize that these syndromes are not part of the AIS classification itself but represent a rather qualitative description of anatomical patterns of injury that can be observed. (pp. 10–13)

Previous changes of the update to the 7th edition in 2015

In the 2015 update, the following clarifications were made and are listed here as a reference.

Clarifications previously made:

ND (not determinable) should be documented on the worksheet when any component of the scoring and classification cannot be determined (e.g., the sensory level, motor level, and neurological level of injury [NLI], the ASIA Impairment Scale [AIS] grade, or the zone of partial preservation [ZPP]) based upon the examination. For example, if NT (not testable) in the scoring of the examination leads to a non-determinable motor level, sensory level or NLI, or AIS grade, or ZPP, then “ND” should be used with the designation of these parameters on the worksheet. It is strongly recommended that the reason for the NT grade be documented in the Comments box.

Non-key muscle functions: The use of non-key muscle functions has been added in the booklet. This includes the spinal cord levels designated for all non-key muscle functions and the clarification when these muscle functions should be tested. Specifically, if a patient is preliminarily classified as sensory incomplete (sacral sensory sparing [AIS B] where all key muscle functions more than 3 levels below the motor level on each side of the body are graded as zero and there is no voluntary anal contraction [VAC]), then non-key muscle functions more than 3 levels below the motor level on each side of the body should be examined to rule out or rule in a motor incomplete grade (AIS B vs C). This information (e.g., non-key muscle functions present in segment ….) should be placed in the Comments box.

Definition of motor incomplete: The previous definition was worded in a complex manner with the definition being followed by multiple footnotes. This has been clarified to the following: “Motor function is preserved at the most caudal sacral segments on voluntary anal contraction (VAC) OR the patient meets the criteria for sensory incomplete status (sensory function preserved at the most caudal sacral segments [S4–S5] by LT, PP, or DAP) and has some sparing of motor function more than three levels below the ipsilateral motor level on either side of the body.” (p. 36)

Additional terms have been added to the Glossary of the booklet, and the worksheet has been updated specifically for the use of non-key muscle functions.

This revised (2019) manual will hopefully serve as a readily available and useful reference for clinicians and researchers. An electronic (e) online training program, the International Standards Training e-Learning Program (InSTeP), includes a five-module course designed to enable clinicians to perform accurate and consistent SCI neurological examinations of individuals with SCI.7 These modules include Basic Anatomy; Sensory Examination; Motor Examination; Anorectal Examination; and Scoring, Scaling, and the AIS Classification. InSTeP has been updated to incorporate the changes referred to in this revised booklet. The electronic modules also provide further details and sample cases on the execution of the examination and classification techniques.7 Additional training courses are also available for the performance of the International Standards examination in the pediatric population (WeeSTeP) and the Autonomic Standards e-Program (ASTeP).8,9 It is recommended that the Autonomic Standards assessment form8 be completed as an adjunct to ISNCSCI, although it is not formally a part of it.

The availability of large databases from SCI registries with ISNCSCI datasets, from the acute to the chronic stage, together with validated computer algorithms for scoring those exams10,11 opens new avenues for simulation and validation of any proposed ISNCSCI changes. Over the past 4 years, the International Standards Committee has made intensive use of these tools to derive the revisions in this booklet, using as much evidence as possible. Nevertheless, special care has been taken to maintain backward-compatibility of the new definitions with the 2011 revision and the changes of the 2015 update. In the future, the Committee will continue to use large databases for verification of potential changes in motor level and AIS definitions.

While the full ISNCSCI exam will remain the reference for evaluation and documentation of SCI, the Committee is fully aware that there are circumstances (e.g., initial screening or follow-up in the chronic stage) where a more rapid but more limited exam may be needed. For this purpose, the expedited ISNCSCI exam (E-ISNCSCI) has been developed to determine the NLI and the AIS with the minimum number of steps using the standard ISNCSCI testing procedures. While the E-ISNCSCI is not a part of this booklet, it has been published as a guideline on the ASIA webpage.12 Further work is also proceeding to develop a more in-depth “Research Options” ISNCSCI (RO-ISNCSCI) that, with minimal additions to the exam, should assist researchers in more deeply characterizing persons with SCI and making greater use of data collected within the exam. Both E-ISNCSI and RO-ISNCSCI are designed to be compatible with the standard ISNCSCI exam.

The Committee recognizes that even with the revisions made in this booklet, there will always be some cases of SCI that are challenging to correctly document with ISNCSCI. The Committee will continue to identify issues that need further clarification and investigation and anticipates publishing revisions – if needed – every 2 years. Therefore, correspondence that raises questions, offers constructive criticism, and/or provides new empirical data that are relevant for further refinements and improvements in the reliability and validity of the International Standards is most welcome.

Rüdiger Rupp, PhD

Chair

ASIA and ISCoS International Standards Committee

In addition to this booklet members of the ASIA International Standards Committee have compiled a series of articles on in-depth explanations, cases with classification challenges, guidelines for an expedited and an extended research exam, and other ISNCSCI-rated issues, which will be soon published in a special issue of Spinal Cord.

Introduction

The spinal cord is the major conduit through which motor and sensory information travels between the brain and body. The spinal cord contains longitudinally oriented spinal tracts (white matter) surrounding central areas (gray matter) where most spinal neuronal cell bodies are located. The gray matter is organized into segments comprising sensory and motor neurons. Axons from spinal sensory neurons enter and axons from motor neurons leave the spinal cord via segmental nerves or roots.

In the cervical spine, there are 8 nerve roots. Cervical roots of C1–C7 are named according to the vertebra above which they exit (i.e., C1 exits above the C1 vertebra, just below the skull and C6 nerve roots pass between the C5 and C6 vertebrae) whereas C8 exists between the C7 and T1 vertebrae; as there is no C8 vertebra. The C1 nerve root does not have a sensory component that is tested on the International Standards examination.

The thoracic spine has 12 distinct nerve roots, and the lumbar spine consists of 5 distinct nerve roots that are each named accordingly as they exit below the level of the respective vertebrae. The sacrum consists of 5 embryonic sections that have fused into one bony structure with 5 distinct nerve roots that exit via the sacral foramina. The spinal cord itself ends at approximately the L1–2 vertebral level. The distal most part of the spinal cord is called the conus medullaris. The cauda equina is a cluster of paired (right and left) lumbosacral nerve roots that originate in the region of the conus medullaris and travel down through the thecal sac and exit via the intervertebral foramen below their respective vertebral levels. There may be 0, 1, or 2 coccygeal nerves, but they do not have a role with the International Standards examination in accordance with the ISNCSCI.

Each root receives sensory information from skin areas called dermatomes. Similarly each root innervates a group of muscles called a myotome. While a dermatome usually represents a discrete and contiguous skin area, most roots innervate more than one muscle, and most muscles are innervated by more than one root.

Spinal cord injury (SCI) affects conduction of sensory and motor signals across the site(s) of lesion(s), as well as the autonomic nervous system. By systematically examining the dermatomes and myotomes, as described within this booklet, one can determine the cord segments affected by the SCI. From the International Standards examination, several measures of neurological damage are generated, e.g., Sensory and Motor Levels (on right and left sides), Neurological Level of Injury (NLI), Sensory Scores (Pin Prick and Light Touch), Motor Scores (upper and lower limb), and Zones of Partial Preservation (ZPP). This booklet also describes the ASIA (American Spinal Injury Association) Impairment Scale (AIS) to classify the severity (i.e., completeness) of injury.

This booklet begins with an overview of clinical syndromes in incomplete lesions and basic definitions of common terms used herein. The section that follows describes the recommended International Standards examination, including both sensory and motor components. Subsequent sections cover sensory and motor scores and the AIS classification. For ease of reference, a fold-out summary chart of the recommended examination is included, with a summary of steps used to classify the injury. A full-size version for photocopying and use in patient records has been included as an enclosure and may also be downloaded from the ASIA website (www.asia-spinalinjury.org).

Additional details regarding the examination and e-learning training materials can also be obtained from the website.7 While examining individuals with SCI, the clinician/investigator should also consider evaluating the remaining autonomic functions using the appropriate form.8,9

Patterns of Incomplete Injuries

While not a part of the International Standards examination or AIS classification, the qualitative descriptions of incomplete injury syndromes have previously been described in this booklet and as such have been maintained as part of the introduction.

Central cord syndrome: Central cord syndrome is the most common of the clinical syndromes, often seen in individuals with underlying cervical spondylosis who sustain a hyperextension injury (most commonly from a fall), and may occur with or without fracture and dislocations. This clinically will present as an incomplete injury with greater weakness in the upper limbs than in the lower limbs.

Brown-Séquard syndrome: Brown Séquard syndrome (historically related to a knife wound) represents a spinal cord hemisection in its pure form, which results in ipsilateral loss of propioception and vibration and motor control at and below the level of lesion, sensory loss of all modalities at the level of the lesion, and contralateral loss of pain and temperature sensation. This specific syndrome in its pure form is rare, more often resulting in a clinical examination with some features of the Brown-Séquard and central cord syndromes. Some refer to this variation as Brown Séquard-plus syndrome.13

Anterior cord syndrome: The anterior cord syndrome is a relatively rare syndrome that historically has been related to a decreased or absent blood supply to the anterior two-thirds of the spinal cord. The dorsal columns are spared, but the corticospinal and spinothalamic tracts are compromised. The clinical symptoms include a loss of motor function, pain sensation, and temperature sensation at and below the injury level with preservation of light touch and joint position sense.

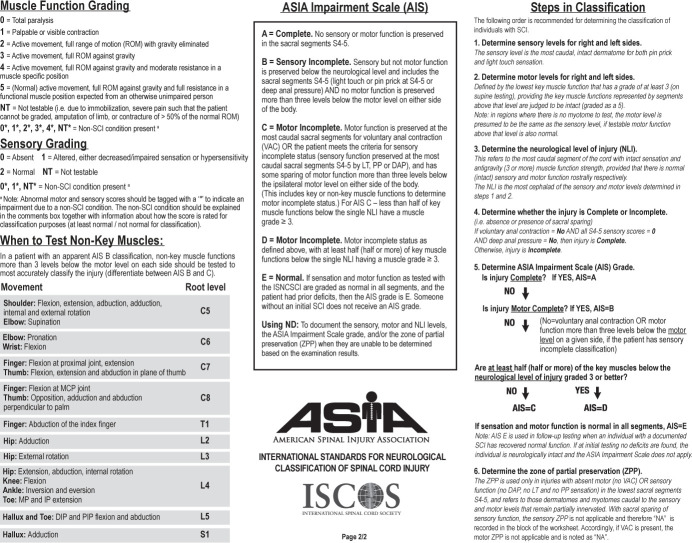

Cauda equina syndrome: Cauda equina syndrome involves the lumbosacral nerve roots of the cauda equina and may spare the spinal cord itself. Injury to the nerve roots, which are, by definition, lower motor neurons, will classically produce a flaccid paralysis of the muscles of the lower limbs (muscles affected depend upon the level of the injury) and areflexic bowel and bladder. All sensory modalities are similarly impaired, and there may be partial or complete loss of sensation. Sacral reflexes (i.e., bulbocavernosus and anal wink) will be absent (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Anatomy of the lumbar-sacral spinal cord

Conus medullaris syndrome: Conus medullaris syndrome may clinically be similar to the cauda equina syndrome, but the injury is more rostral in the cord (L1 and L2 area), relating most commonly to a thoraco-lumbar bony injury (Figure 1). Depending on the level of the lesion, this type of injury may manifest itself with a mixed picture of upper motor neuron (due to conus injury) and lower motor neuron symptoms (due to nerve root injury). In some cases, this may be very difficult to clinically distinguish from a cauda equina injury. Sacral segments may occasionally show preserved reflexes (i.e., bulbocavernosus and anal wink) with higher lesions of the conus medullaris.

Definitions

- Tetraplegia (preferred to “quadriplegia”):

This term refers to impairment or loss of motor and/or sensory function in the cervical segments of the spinal cord due to damage of neural elements within the spinal canal. Tetraplegia results in impairment of function in the arms as well as typically in the trunk, legs, and pelvic organs (i.e., including the four extremities). It does not include brachial plexus lesions or injury to peripheral nerves outside the neural canal.

- Paraplegia:

This term refers to impairment or loss of motor and/or sensory function in the thoracic, lumbar, or sacral (but not cervical) segments of the spinal cord, secondary to damage of neural elements within the spinal canal. With paraplegia, arm functioning is spared, but, depending on the level of injury, the trunk, legs, and pelvic organs may be involved. The term is used in referring to cauda equina and conus medullaris injuries but not to lumbosacral plexus lesions or injury to peripheral nerves outside the neural canal.

- Tetraparesis and paraparesis:

Use of these terms is discouraged, as they describe incomplete lesions imprecisely and incorrectly imply that tetraplegia and paraplegia should only be used for neurologically complete injuries. Instead, the ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS) provides a more precise approach to description of severity (i.e., completeness) of the SCI.

- Dermatome:

This term refers to the area of skin innervated by the sensory axons within each segmental nerve (root).

- Myotome:

This term refers to the collection of muscle fibers innervated by the motor axons within each segmental nerve (root).

- Key muscle functions:

This term refers to the 10 muscle functions that are tested in all patients, and scores from the examination are documented on the worksheet.

- Non-key muscle functions:

This term refers to muscle functions that are not part of the key muscle functions listed on the front side of the worksheet (see pp.28–30). In a patient with an apparent AIS B classification, non-key muscle functions more than 3 levels below the motor level on each side should be tested to most accurately classify the injury (differentiate between AIS B and C). The results should be placed in the Comments box.

- Sensory level:

The sensory level is determined by performing an examination of the key sensory points within each of the 28 dermatomes on each side of the body (right and left) and is the most caudal dermatome with normal function for both pin prick (sharp/dull discrimination) and light touch sensation. This may be different for the right and left sides of the body.

- Motor level:

The motor level (ML) is determined by examining a key muscle function within each of 10 myotomes on each side of the body and is defined by the lowest key muscle function that has a grade of at least 3 (on manual muscle testing [MMT] in the supine position), providing the key muscle functions represented by segments above that level are judged to be intact (graded as a 5 on MMT). This may be different for the right and left sides of the body.

- Neurological level of injury (NLI):

The NLI refers to the most caudal segment of the spinal cord with normal sensory and antigravity motor function on both sides of the body, provided that there is normal (intact) sensory and motor function rostrally. The segments at which normal function is found often differ by side of the body and in terms of sensory and motor testing. Thus, up to four different segments may be identified in determining the neurological level, i.e., R(ight)-sensory, L(eft)-sensory, R-motor, L-motor. The single NLI is the most rostral of these levels.

- Skeletal level:

This term has been used to denote the level at which, by radiographic examination, the greatest vertebral damage is found. The skeletal level is not part of the current ISNCSCI because not all cases of SCI have a bony injury, bony injuries do not consistently correlate with the neurological injury to the spinal cord, and this term cannot be revised to document neurological improvement or deterioration.

- Sensory scores (see summary chart):

This term refers to a numerical summary score of sensory function. There is a maximum total of 56 points each for light touch and pin prick (sharp/dull discrimination) modalities, for a total of 112 points per side of the body. This can reflect the degree of neurological impairment associated with the SCI.

- Motor scores (see summary chart):

This term refers to a numerical summary score of motor function. There is a maximum score of 25 for each extremity, totaling 50 for the upper limbs and 50 for the lower limbs. This score can reflect the degree of motor impairment associated with the SCI.

- Sacral sparing:

The presence of residual preserved neurological function at the most caudal aspect of the cord (S4/S5) as determined by examination of sensory and motor functions. Sensory sacral sparing includes sensation preservation (intact or impaired) at the anal mucocutaneous junction (S4–5 dermatome) on one or both sides for light touch or pin prick or the presence of deep anal pressure (DAP). Motor sacral sparing includes the presence of voluntary contraction of the external anal sphincter upon digital rectal examination.

- Complete injury:

This term is used when there is an absence of any sensory and motor function in the lowest sacral segments (light touch, pin prick at S4–5, DAP, and voluntary anal contraction) (i.e., no “sacral sparing”).

- Incomplete injury:

This term is used when there is preservation of any sensory and/or motor function below the neurological level that includes the lowest sacral segments S4–5 (i.e., presence of “sacral sparing”).

- Zone of partial preservation (ZPP):

This term, used only in injuries with absent motor (no VAC) OR sensory function (no DAP, no LT, and no PP sensation) in the lowest sacral segment S4–5, refers to those dermatomes and myotomes caudal to the sensory and motor levels with partially preserved functions. The most caudal segment with some sensory and/or motor function defines the extent of the sensory or motor ZPP respectively and are documented as four distinct levels (R-sensory, L-sensory, R-motor, and L-motor).

- Not determinable (ND):

This term is used on the worksheet when trying to document the sensory, motor, and NLI levels, the AIS grade, or ZPP when they cannot be determined based upon the examination results. For example, if NT (not testable) is used in the scoring for the examination, and the motor, sensory, or NLI, AIS grade, or ZPP cannot be determined in a specific case based upon this, then ND should be used for the designation of the levels and AIS grade on the worksheet. It is strongly recommended that the reason for the NT grade be documented in the Comments box.

Neurological Examination

Introduction

The International Standards examination used for neurological classification has two components (sensory and motor), which are separately described below. These elements are used in determining the sensory/motor/neurological levels, in generating scores to characterize sensory/motor functioning, and in determining completeness of the injury. The examination does not represent a comprehensive neurological examination for a patient with SCI, as it does not include elements that are not used for determining classification, such as deep tendon reflexes, etc. Although more precise measurements of sensory and motor function are available, the current examination uses common clinical measures that can be performed with minimal equipment (safety pin and cotton wisp) and in virtually any clinical setting and phase of care.

The examination should be performed with the patient in the supine position (except for the rectal examination that can be performed sidelying) to allow for a valid comparison of scores throughout the phases of care. Initially if there is spinal instability, without orthotic stabilization, the patient should be log-rolled (so there is no twisting of the spinal column) on their side to complete the anorectal exam, or alternatively an abbreviated exam can be performed in the supine position.

When the patient is not fully testable

When a key sensory point or key muscle function is not testable for any reason, (i.e., because of a cast, burn, amputation, or if the patient is unable to appreciate sensation on the face), the examiner should record “NT” (not testable) instead of a numeric score. In such cases, sensory and motor scores for the affected side of the body, as well as total sensory and motor scores, cannot be generated at that point in treatment. Further, when associated injuries (e.g., traumatic brain injury, brachial plexus injury, limb fracture, etc.) interfere with completion of the examination, the neurological level should still be determined as accurately as possible.14 However, obtaining the sensory/motor scores and ASIA Impairment Scale grades may be deferred to later examinations.

Sensory examination — required elements

The required portion of the sensory examination is completed through the testing of a key point in each of the 28 dermatomes (from C2 to S4–5) on the right and left sides of the body15 that can be readily located in relation to bony anatomical landmarks. At each of these key points, two aspects of sensation are examined: light touch and pin prick (sharp-dull discrimination).

Appreciation of light touch and pin prick sensation at each of the key points is separately scored on a 3-point scale, with comparison to the sensation on the patients’ cheek as a normal frame of reference:

0 = Absent

1 = Altered (impaired or partial appreciation, including hyperaesthesia)

2 = Normal or intact (similar as on the cheek)

NT = Not testable

0*, 1*, NT* = Non-SCI condition present

Abnormal scores including NT (i.e., 0, 1, NT) should be tagged with an “*” to indicate that this score is impacted by a non-SCI condition (e.g., brachial plexus lesion, limb amputation) or confounding factors such as skin burn, pain, limb swelling. The non-SCI condition should be explained in the Comments box together with information about how the score is rated for classification purposes. If the non-SCI condition is clearly above the sensory level, the tagged scores should be rated as normal or intact for classification. If the non-SCI condition is superimposed on the SCI, which is the case at or below the sensory level, the classification should be performed on the basis of the examined scores and all other possible scores greater than the examined score except normal. Any classification parameter that has been determined based on an examiner’s assumption should also be tagged with the “*”.

Light touch sensation is tested with a tapered wisp of cotton stroked once across an area not to exceed 1 cm of skin with the eyes closed or vision blocked.

Pin prick sensation (sharp/dull discrimination) is performed with a disposable safety pin that is stretched apart to allow testing on both ends; using the pointed end to test for sharp and the rounded end of the pin for dull. In testing for pin prick appreciation, the examiner must determine if the patient can correctly and reliably discriminate between sharp and dull sensation at each key sensory point. If in doubt, 8 out of 10 correct answers are suggested as a standard for accuracy, as this reduces the probability of correct guessing to less than 5%. The inability to distinguish between dull and sharp sensation (as well as no feeling when being touched by the pin) is graded as 0.

A grade of 1 for pin prick is given when sharp/dull sensation is altered. In this case, the patient reliably distinguishes between the sharp and dull ends of the pin but states that the intensity of sharpness is different in the key sensory point than the feeling of sharpness on the face. The intensity may be greater or lesser than the feeling on the face.

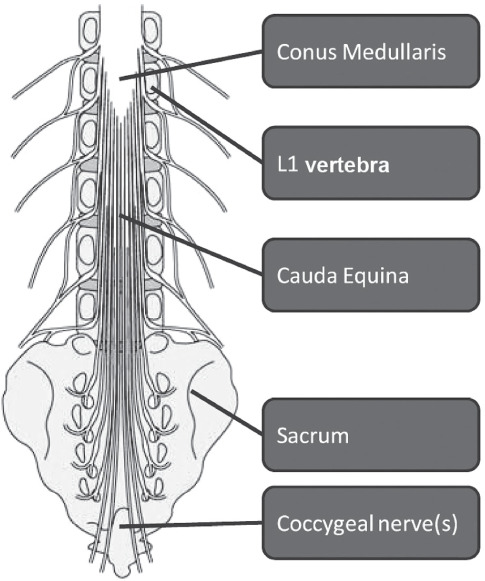

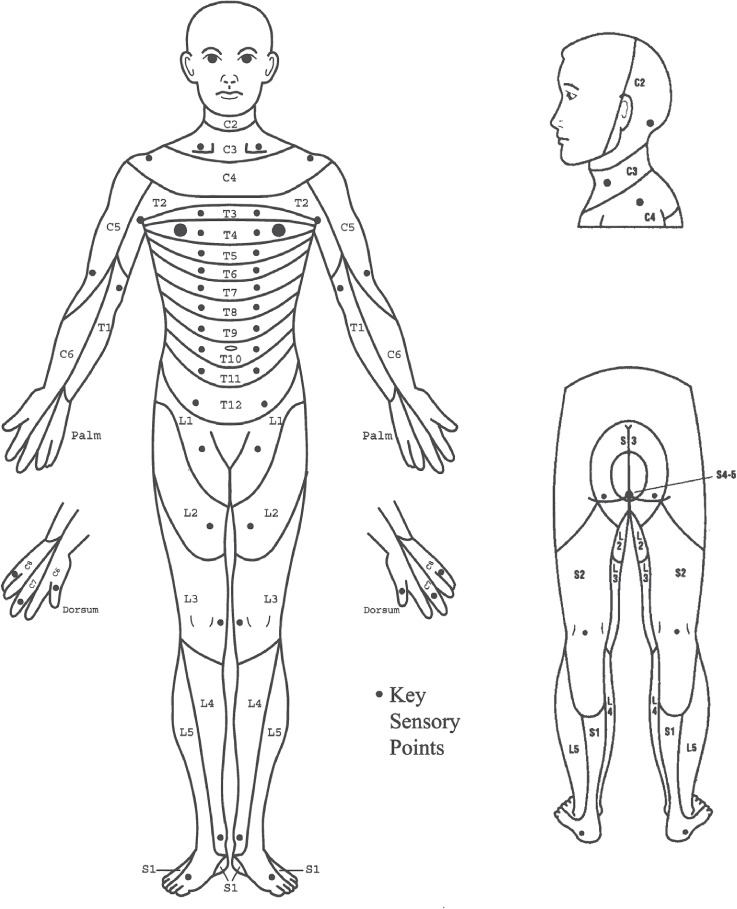

The following key points are to be tested bilaterally for sensitivity from C2-S4/5 dermatomes (see Figure 2 and diagram on the fold-out summary chart):

Figure 2:

Key sensory points

-

C2 -

At least 1 cm lateral to the occipital protuberance (alternatively 3 cm behind the ear)

-

C3 -

Supraclavicular fossa (posterior to the clavicle) and at the midclavicular line

-

C4 -

Over the acromioclavicular joint

-

C5 -

Lateral (radial) side of the antecubital fossa (just proximal to elbow crease)

-

C6 -

Thumb, dorsal surface, proximal phalanx

-

C7 -

Middle finger, dorsal surface, proximal phalanx

-

C8 -

Little finger, dorsal surface, proximal phalanx

-

T1 -

Medial (ulnar) side of the antecubital) fossa, just proximal to the medial epicondyle of the humerus

-

T2 -

Apex of the axilla

-

T3 -

Midclavicular line and the third intercostal space (IS) found by palpating the anterior chest to locate the third rib and the corresponding IS below it.*

-

T4 -

Fourth IS (nipple line) at the midclavicular line

-

T5 -

Midclavicular line and the fifth IS (midway between T4 and T6)

-

T6 -

Midclavicular line and the sixth IS (level of xiphisternum)

-

T7 -

Midclavicular line and the seventh IS (midway between T6 and T8)

-

T8 -

Midclavicular line and the eighth IS (midway between T6 and TI0)

-

T9 -

Midclavicular line and the ninth IS (midway between T8 and T10)

-

T10 -

Midclavicular line and the tenth IS (umbilicus)

-

T11 -

Midclavicular line and the eleventh IS (midway between T10 and Tl2)

-

T12 -

Midclavicular line and the mid-point of the inguinal ligament

-

L1 -

Midway distance between the key sensory points for Tl2 and L2

-

L2 -

On the anterior-medial thigh at the midpoint drawn connecting the midpoint of inguinal ligament (T12) and the medial femoral condyle

-

L3 -

Medial femoral condyle above the knee

-

L4 -

Medial malleolus

-

L5 -

Dorsum of the foot at the third metatarsal phalangeal joint

-

S1 -

Lateral heel (calcaneus)

-

S2 -

Mid-point of the popliteal fossa

-

S3 -

Ischial tuberosity or infragluteal fold

-

S4–5 -

Perianal area less than 1 cm lateral to the mucocutaneous junction (taken as one level)

Deep anal pressure (DAP): DAP awareness is examined through insertion of the examiner‘s index finger and application of gentle pressure to the anorectal wall (innervated by the somatosensory components of the pudendal nerve S4/5). Alternatively, pressure can be applied by using the thumb to gently squeeze the anus against the inserted index finger. Consistently perceived pressure should be graded as being present or absent (i.e., enter YES or NO on the worksheet). Any reproducible pressure sensation felt in the anal area during this part of the exam signifies that the patient has a sensory incomplete lesion. In patients who have light touch or pin prick sensation at S4–5, evaluation of DAP is not required as the patient already has a designation for a sensory incomplete injury. The rectal examination is still required, however, to test for motor sparing (i.e., voluntary anal sphincter contraction) in the lowest sacral segments.

Sensory examination — optional elements

For purposes of the SCI evaluation, the following aspects of sensory function are considered as optional: joint movement appreciation and position sense, and awareness of deep pressure/deep pain. (Note: there is no specific portion for this to be recorded on the worksheet except for the comments section.) Joint movement appreciation and position sense are graded using the same sensory scale provided (absent, impaired, normal). A grade of 0 (absent) indicates the patient is unable to correctly report joint movement on large movements of the joint. A grade of 1 (impaired) indicates the patient is able to consistently report joint movement with 8 of 10 correct answers, but only on large movements of the joint, and is unable to consistently report small movements of the joint. A 2 (normal) indicates the patient is able to consistently report joint movement with 8 out of 10 correct answers on both small (approximately 10° of motion) and large movements of the joint. Joints that can be tested include the interphalangeal (IP) joint of the thumb, the proximal IP joint of the little finger, the wrist, the IP joint of the great toe, the ankle, and the knee.

Deep pressure appreciation of the limbs (applying firm pressure to the skin for 3–5 seconds at different locations of the wrist, fingers, ankles, and toes) can be tested for patients in whom light touch and pin prick modalities are graded as 0 (absent). Because this test is electively performed in the absence of light touch and pin prick sensation, it is graded as either a 0 for absent or 1 for present in reference to firm pressure, using the index finger or thumb, to the chin.

Motor examination — required elements

The required portion of the motor examination is completed through the testing of key muscle functions corresponding to 10 paired myotomes (C5-T1 and L2-S1) (see later discussion). It is recommended that each key muscle function should be examined in a rostral-caudal sequence, utilizing standard supine positioning and stabilization of the individual muscles being tested. Improper positioning and stabilization can lead to substitution by other muscles and will not accurately reflect the muscle function being graded.

The strength of each muscle function is graded on a 6-point scale.16–18

0 = Total paralysis

1 = Palpable or visible contraction

2 = Active movement, full range of motion (ROM) with gravity eliminated

3 = Active movement, full ROM against gravity

4 = Active movement, full ROM against moderate resistance in a muscle specific position

5 = (Normal) active movement, full ROM against full resistance in a muscle-specific position expected from an otherwise unimpaired person

NT = Not testable (i.e., due to immobilization, severe pain such that the patient cannot be graded, amputation of limb, or contracture of >50% of the range of motion)

0,* 1,* 2,* 3,* 4,* NT* = Non-SCI condition present

In cases of a muscle function whose ROM is limited by a contracture, if the patient exhibits >50% of the normal range, then the muscle function can be graded through its available range with the same 0 to 5 scale. If the ROM is limited to <50% of the normal ROM, NT should be documented.

Abnormal scores including NT (i.e., 0–4, NT) should be tagged with an “*” to indicate that the score is impacted by a non-SCI condition (e.g., brachial plexus lesion, limb amputation) or confounding factors such as disuse or musculoskeletal pain. The non-SCI condition should be explained in the Comments box together with information about how the score is rated for classification purposes. If the non-SCI condition is clearly above the motor level, the tagged scores should be rated as normal or intact for classification. If the non-SCI condition is superimposed on the SCI, which is the case at or below the motor level, the classification should be performed on the basis of the examined scores and all other possible scores greater than the examined score except normal. Any classification parameter that has been determined based on an examiner’s assumption should also be tagged with the “*”.

The following muscles are examined (bilaterally) and graded using the scale defined. The muscles were chosen because of their consistency for being innervated by the segments indicated, with innervation from at least two spinal segments, each muscle having functional significance, and adequately accessible and easily isolated to examination in the supine position.

-

C5 -

Elbow flexors (biceps, brachialis)

-

C6 -

Wrist extensors (extensor carpi radialis longus and brevis)

-

C7 -

Elbow extensors (triceps)

-

C8 -

Finger flexors (flexor digitorum profundus) to the middle finger

-

T1 -

Small finger abductors (abductor digiti minimi)

-

L2 -

Hip flexors (iliopsoas)

-

L3 -

Knee extensors (quadriceps)

-

L4 -

Ankle dorsiflexors (tibialis anterior)

-

L5 -

Long toe extensors (extensor hallucis longus)

-

S1 -

Ankle plantar flexors (gastrocnemius, soleus)

When testing for grade 4 or 5 strength, the following specific positions should be used. Please refer to the InSTeP training or the muscle function testing downloads for details for grades 0 to 3 testing.7

-

C5 -

Elbow flexed at 90°, arm at the patient’s side and forearm supinated

-

C6 -

Wrist in full extension

-

C7 -

Shoulder is neutral rotation, adducted, and in 90° of flexion with elbow in 45° of flexion

-

C8 -

Full flexed position of the distal phalanx with the proximal finger joints stabilized in an extended position

-

T1 -

Full abducted position of fingers

-

L2 -

Hip flexed to 90°

-

L3 -

Knee flexed to 15°

-

L4 -

Full dorsiflexed position of ankle

-

L5 -

First toe fully extended

-

S1 -

Hip in neutral rotation, neutral flexion/extension, and neutral abduction/adduction; the knee is fully extended; and the ankle in full plantarflexion

In a patient with a potentially unstable spine, care must be taken when performing any manual muscle testing. When examining a patient with a suspected acute traumatic injury below the T8 level, the hip should not be allowed to actively or passively flex beyond 90° due to the increased kyphotic stress placed on the lumbar spine. Examination should be performed isometrically and unilaterally, so that the contralateral hip remains extended to stabilize the pelvis.

Voluntary anal contraction (VAC): The external anal sphincter (innervated by the somatic motor components of the pudendal nerve from S2–4) should be tested on the basis of reproducible voluntary contractions of the anal sphincter muscles around the examiner’s finger inserted into the rectum and graded as being present or absent (i.e., enter YES or NO on the worksheet). The instruction to the patient should be “squeeze my finger as if to hold back a bowel movement.” If there is VAC present, then the patient has a motor incomplete injury. Care should be taken to distinguish VAC from reflex anal contraction; if contraction can be produced only with Valsalva maneuver, it may be indicative of reflex contraction and should be scored as absent.

Motor examination — non-key muscle functions

Non-key muscle functions refer to muscle functions that are not part of the 10 key muscle functions listed on the worksheet that are examined in all cases. While these muscle functions are not used in determining motor levels or scores, the International Standards allows non-key muscle functions to determine motor incomplete status; AIS B versus C (see later discussion). In a patient with an apparent AIS B classification, non-key muscle functions more than 3 levels below the motor level on each side should be tested to most accurately classify the injury (differentiate between AIS B and C). The results should be documented in the Comments box on the worksheet.

Non-key muscle function levels were chosen after reviewing multiple key reference sources for myotomal distributions followed by external review. From these, the most rostral (proximal) innervation of muscles that usually performs that activity was chosen.2 Functional movements were included in the table as opposed to specific muscles to remove the potential difficult task of determining which of the possible muscles that can provide that function is active in each individual case.

Non-key muscle functions

| Movement | Root level |

|---|---|

| Shoulder: Flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, internal and external rotation Elbow: Supination | C5 |

| Elbow: Pronation Wrist: Flexion | C6 |

| Finger: Flexion at proximal joint, extension Thumb: Flexion, extension and abduction in plane of thumb | C7 |

| Finger: Flexion at metacarpophalangeal joint Thumb: Opposition, adduction, and abduction perpendicular to palm | C8 |

| Finger: Abduction of little finger | T1 |

| Hip: Adduction | L2 |

| Hip: External rotation | L3 |

| Hip: Extension, abduction, internal rotation Knee: Flexion Ankle: Inversion and eversion Toe: Metacarpophalangeal and interphalangeal extension | L4 |

| Hallux and toe: Distal interphalangeal and proximal interphalangeal flexion and abduction | L5 |

| Hallux: Adduction | S1 |

Sensory and Motor Scores/Levels

Sensory level

The sensory level is the most caudal, intact dermatome for both pin prick and light touch sensation. This is determined by a grade of 2 (normal/intact) in all dermatomes beginning with C2 and extending caudally to the first segment that has a score of less than 2 for either light touch or pin prick. The intact dermatome level located immediately above the first dermatome level with impaired or absent light touch or pin prick sensation is designated as the sensory level. Since the right and left sides may differ, the sensory level should be determined for each side. Testing will generate up to four sensory levels per dermatome: R-pin prick, R-light touch, L-pin prick, L-light touch. For a single sensory level, the most rostral of all is taken.

If sensation is abnormal at C2 and intact on the face, the sensory level should be designated as C1. If sensation is intact on one side (or both) for light touch and pin prick at all dermatomes C2 through S4–S5, the sensory level for that side should be recorded as “INT” that indicates intact, rather than as S5.

If the sensory level is determined based on assumptions of an examiner (replacement of “*”-tagged sensory scores by assumed scores during classification), then the level should be marked with an “*”.

Sensory scores

Required testing generates scores for each dermatome for pin prick and light touch that can be summed across dermatomes and sides of body to generate two summary sensory scores: pin prick and light touch. Normal sensation for each modality is reflected in a score of 2. A score of 2 for each of the 28 key sensory points tested on each side of the body would result in a maximum score of 56 for pin prick, 56 for light touch, and a total of 112. The sensory score cannot be calculated if any required key sensory point is not tested. The sensory scores provide a means of numerically documenting changes in sensory function.

Motor level

The motor level is determined by examining the key muscle functions within each of 10 myotomes and is defined by the lowest key muscle function that has a grade of at least 3 (on supine MMT), providing the key muscle functions represented by segments above that level are judged to be intact (graded as a 5). This can be different for the right and left side of the body. A single motor level would be the more rostral of the two.

If the motor level is determined based on assumptions of an examiner (replacement of “*”-tagged sensory scores by assumed scores during classification), then the level should be marked with an “*”.

Further considerations for motor level determination

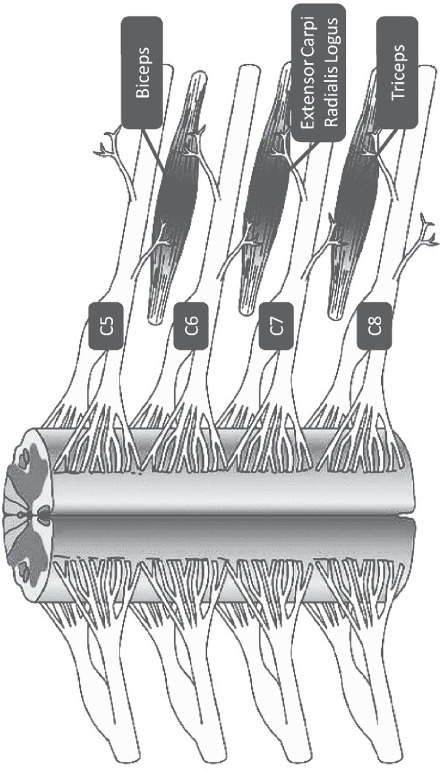

Just as each segmental nerve (root) innervates more than one muscle, most muscles are innervated by more than one nerve segment (usually two segments; see Figure 3). Therefore, the assigning of one muscle or one muscle group (i.e., the key muscle function) to represent a single spinal nerve segment is a simplification, used with the understanding that in any muscle the presence of innervation by one segment and the absence of innervation by the other segment will result in a weakened muscle.

Figure 3:

Schematic depiction of innervation of each three key muscles by two nerve segments

By convention, if a muscle function has at least a grade of 3, it is considered to have intact innervation by the more rostral of the innervating segments. In determining the motor level, the next most rostral key muscle function must test as 5, since it is assumed that the muscle(s) will have both of its two innervating segments intact. For example, if no activity is found in the C7 key muscle function and the C6 muscle function is graded as 3, then the motor level for the tested side of the body is C6, providing the C5 muscle function is graded 5.

The examiner’s judgment is relied upon to determine whether an abnormal muscle function (less than 5) may in fact be stronger (up to normal = 5). This may occur when full effort from the patient is inhibited by factors such as pain, positioning, and hypertonicity or when weakness is judged to be due to disuse. If any of these or other factors impede standardized muscle testing, the muscle function should be graded as not testable (NT). However, if these factors do not prevent the patient from performing a forceful contraction and the examiner’s best judgment is that the muscle function would test differently if these factors are not present, the examined score should be tagged with an “*” and explained in the Comments box.

For those myotomes that are not clinically testable by a manual muscle exam (i.e., C1 to C4, T2 to L1, and S2 to S5), the motor level is presumed to be the same as the sensory level if testable motor function above (rostral to) that level is normal as well. Examples will help clarify.

-

Example 1:

If the sensory level is C4, and there is no C5 motor function strength (or strength graded <3), the motor level is C4.

-

Example 2:

If the sensory level is C4, with the C5 key muscle function strength graded as ≥3, the motor level would be C5 because the strength at C5 is at least 3 with the muscle function above considered normal. Presumably if there was a C4 key muscle function, it would be graded as normal since the sensation at C4 is intact.

-

Example 3:

If the sensory level is C3, with the C5 key muscle function strength graded as ≥3, the motor level is C3. This is because the motor level presumably at C4 is not considered normal (since the C4 dermatome is not normal), and the rule of all levels rostral needing to be intact is not met.

Similar rules apply in the lower extremity where L2 is the first key muscle function. L2 can only be considered a motor level if sensation at L1 and more rostral is intact.

-

Example 4:

If all upper limb key muscle functions are intact, with intact sensation to T6, the sensory level as well as the motor level are recorded as T6.

-

Example 5:

In the case similar to example 4, but the T1 muscle function graded a 3 or 4 instead of a 5 while T6 is still the sensory level, the motor level is T1, as all the muscles above the T6 level cannot be considered normal.

Motor scores

The required motor testing generates two motor grades per paired myotome: right and left. As indicated on the worksheet, these scores are then summed across myotomes and sides of body to generate a single motor score each for the upper and for the lower limbs. The motor score provides a means of numerically documenting changes in motor function. Normal strength is assigned a grade of 5 for each muscle function. A score of 5 for each of the five key muscle functions of the upper extremity would result in a maximum score of 25 for each extremity, totaling 50 for the upper limbs. The same is true for the five key muscle functions of the lower extremity, totaling a maximum score of 50 for the lower limbs. The motor score cannot be calculated if any required muscle function is not tested.

Although historically a total motor score of 100 for all extremities was calculated, for the last decade it has not been recommended to add the upper limb and lower limb scores together. Examination of the metric properties of the motor score indicates that it should be separated into two scales, one composed of the 10 upper limb muscle functions, and one of the 10 lower limb muscle functions, with a maximum score of 50 each.19

Neurological level of injury (NLI)

The NLI refers to the most caudal segment of the cord with intact sensation and antigravity muscle function strength, provided that there is normal (intact) sensory and motor function rostrally.

The sensory and motor levels are determined for the right and left side, based upon the examination findings for the key sensory points and key muscle functions. Therefore, four separate levels are possible: a right sensory level, left sensory level, right motor level, and a left motor level. The single NLI is the most rostral of these four levels and is used during the classification process. In cases such as this, however, it is recommended that each of these segments be separately recorded since a single NLI may be misleading from a functional standpoint if the sensory level is rostral to the motor level.

If any sensory or motor level is determined based on assumptions of an examiner (tagged with an “*”), then the neurological level should also be marked with an “*”.

ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS) (Modified from Frankel)20–23

Injuries are classified in general terms of being neurologically “complete” or “incomplete” based upon the sacral sparing definition. “Sacral sparing” refers to the presence of sensory or motor function in the most caudal sacral segments as determined by the examination (i.e., preservation of light touch or pin prick sensation at the S4–5 dermatome, DAP, or VAC). A complete injury is defined as the absence of sacral sparing (i.e., sensory and motor function in the lowest sacral segments, S4–5), whereas an incomplete injury is defined as the presence of sacral sparing.

The following ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS) designation is used in grading the degree of impairment:

A = Complete. No sensory or motor function is preserved in the sacral segments S4–S5.

B = Sensory Incomplete. Sensory but not motor function is preserved at the most caudal sacral segments S4–S5 AND no motor function is preserved more than three levels below the motor level on either side of the body.

C = Motor Incomplete. Motor function is preserved at the most caudal sacral segments on voluntary anal contraction (VAC) OR the patient meets the criteria for sensory incomplete status (sensory function preserved at the most caudal sacral segments (S4–S5) by LT, PP, or DAP), with sparing of motor function more than three levels below the motor level on either side of the body. This includes key or non-key muscle functions more than three levels below the motor level to determine motor incomplete status. For AIS C, less than half of key muscle functions below the single NLI have a muscle grade ≥ 3.

D = Motor Incomplete. Motor incomplete status as defined above, with at least half (half or more) of key muscle functions below the single NLI having a muscle grade ≥ 3.

E = Normal. If sensation and motor function as tested with the ISNCSCI are graded as normal in all segments and the patient had prior deficits, then the AIS grade is E. Someone without an SCI does not receive an AIS grade.

Note: When assessing the extent of motor sparing below the level for distinguishing between AIS B and C, the motor level on each side is used; whereas to differentiate between AIS C and D (based on proportion of key muscle functions with strength grade 3 or greater), the single neurological level (NLI) is used.

If the AIS is determined based on assumptions of an examiner (replacement of “*”-tagged sensory scores by assumed scores during classification), then the AIS should be marked with an “*”. There might be cases where the AIS classification is not impacted by the examiner’s assumptions (e.g., AIS A with “*”-tagged scores rostral to S4–5).

Zone of partial preservation (ZPP)

The ZPP is used only in injuries with absent motor (no VAC) or sensory function (no DAP, no LT, and no PP sensation) in the lowest sacral segments S4–5 and refers to those dermatomes and myotomes caudal to the sensory and motor levels with partially preserved functions. The most caudal segment with some sensory or motor function defines the extent of the sensory or motor ZPP, respectively, and should be recorded for the right and left sides and for sensory and motor function. A single segment (not a range of segments) is designated on the worksheet for each of these. For example, if the right sensory level is C5, and some sensation extends from C6 through C8, then “C8” is recorded in the right sensory ZPP block on the worksheet. If there are no segments with partially preserved functions below a motor or sensory level, then the motor or sensory level should be entered in the box for the ZPP on the worksheet.

Note that motor function does NOT follow sensory function in recording ZPP, but rather the caudal extent of the motor ZPP must be based on the presence of voluntary muscle contraction below the motor level. In a case where the motor, sensory, and therefore NLI is T4, with sparing of some sensation at the left T6 dermatome, T6 should be entered for the left sensory ZPP, but the box for motor ZPP should remain T4.

Non-key muscles are generally not included in the ZPP. However, when the most caudal non-key muscle function is used for AIS C classification, the associated root level should be recorded as motor ZPP.

In case of missing DAP, but present PP or LT sensation on a given side, the sensory ZPP on this side is not applicable and therefore “NA” is recorded in the block on the worksheet. If DAP is present, the sensory ZPPs of both sides are not applicable. Accordingly, if VAC is present, the motor ZPP on both sides are not applicable and are noted as “NA”.

If the sensory or motor ZPP is determined based on assumptions of an examiner (replacement of “*”-tagged sensory scores by assumed scores during classification), then the ZPP should be marked with an “*”.

Documenting a level and AIS grade when NT has been documented

When NT (not testable) has been documented for a particular motor or sensory score, there are times when sensory, motor, and neurological levels of injury, as well as the ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS) grade cannot be determine.11 In such cases, “ND” (not determinable) should be documented on the worksheet. As mentioned previously, it is strongly recommended to document the reason for the NT grade in the Comments box. In case scenarios, however, where the NT does not impact the determination of these levels or AIS grade, they can be documented on the worksheet.14

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following members of the International Standards Committee: Randal Betz, MD, William Donovan, MD, Andrei Krassioukov, MD, PhD, Mary Jane Mulcahey, OT, PhD, and John Steeves, PhD.

Footnotes

*An alternative way of locating T3 is by palpating the manubriosternal joint, which is at the level of the second rib. At that point, move slightly lateral to palpate the second rib and continue to move in a caudal direction to locate rib three and the corresponding intercostal space just below it.

References

- 1.American Spinal Injury Association International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Atlanta, GA: ASIA; updated 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirshblum S, Waring W., 3rd Updates for the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2014;25(3):505–517. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu N, Zhou MW, Krassioukov AV, Biering-Sørensen F. Training effectiveness when teaching the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI) to medical students. Spinal Cord. 2013;51(10):768–771. doi: 10.1038/sc.2013.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuld C, Wiese J, Franz S, Putz C, et al. Effect of formal training in scaling, scoring and classification of the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury. Spinal Cord. 2013;51(4):282–288. doi: 10.1038/sc.2012.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schuld C, Franz S, Weidner N, Kirshblum S, Tansey K, Rupp R. Increasing the clinical value of the zones of partial preservation — A quantitative comparison of a new definition rule applicable also in incomplete lesions. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2018;24(Suppl 1):120–121. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schuld C, et al. International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury: impact of the revised worksheet (revision 02/13) on classification performance. J Spinal Cord Med. 2016;39(5):504–512. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2016.1180831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. www.asialearningcenter.com.

- 8.International Standards to Document Remaining Autonomic Function After Spinal Cord Injury. Atlanta, GA: American Spinal Injury Association; 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krassioukov A, Biering-Sørensen F, Donovan W, Kennelly M, Kirshblum S, Krogh K, Alexander MS, Vogel L, Wecht J, Autonomic Standards Committee of the American Spinal Injury Association/International Spinal Cord Society International Standards to document remaining Autonomic Function after Spinal Cord Injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2012 Jul;35(4):201–210. doi: 10.1179/1079026812Z.00000000054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walden K, Bélanger LM, Biering-Sørensen F, Burns SP, Echeverria E, Kirshblum S, et al. Development and validation of a computerized algorithm for International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury (ISNCSCI) Spinal Cord. 2016;54(3):197–203. doi: 10.1038/sc.2015.137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuld C, Wiese J, Hug A, Putz C, van Hedel HJA, Spiess MR, et al. Computer implementation of the International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury for consistent and efficient derivation of its subscores including handling of data from not testable segments. J Neurotrauma. 2012;29:453–461. doi: 10.1089/neu.2011.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. http://asia-spinalinjury.org.

- 13.Roth EJ, Park T, Pang T, Yarkony GM, Lee MY. Traumatic cervical Brown Sequard and Brown-Sequard plus syndromes: the spectrum of presentations and outcomes. Paraplegia. 1991;29:582–589. doi: 10.1038/sc.1991.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirshblum SC, Biering-Sørensen F, Betz R, Burns S, et al. International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury: cases with classification challenges. J Spinal Cord Med. 2014;37(2):120–127. doi: 10.1179/2045772314Y.0000000196. Erratum in: J Spinal Cord Med 2014;37(4):481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Austin GM. The Spinal Cord Basic Aspects and Surgical Considerations. 2nd ed. Springfield, IL: Thomas; 1972. p. 762. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Medical Research Council, Nerve Injuries Committee; University of Edinburgh, Department of Surgery Aids to Investigation of Peripheral Nerve Injuries. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office; 1943. Medical Research Council Memorandum no. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brunnstrom F, Dennen M. Round table on muscle testing; Annual Conference of American Physical Therapy Association, Federation of Crippled and Disabled, Inc; New York. 1931. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Daniels L, Worthingham C. Muscle Testing Techniques of Manual Examination. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marino R, Graves D. Metric properties of the ASIA motor score: subscales improve correlation with functional activities. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(11):1804–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2004.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frankel HL, Hancock DO, Hyslop G, et al. The value of postural reduction in the initial management of closed injuries of the spine with paraplegia and tetraplegia. Paraplegia. 1969;7(3):179–192. doi: 10.1038/sc.1969.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Spinal Injury Association International Standards for Neurological Classification of Spinal Cord Injury revised 2000. Atlanta, GA: ASIA; reprinted 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tator CH, Rowed DW, Schwartz ML, editors. Sunnybrook Cord Injury Scales for Assessing Neurological Injury and Neurological Recovery in Early Management of Acute Spinal Cord Injury. New York: Raven Press; 1982. p. 7. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waters RL, Adkins RH, Yakura JS. Definition of complete spinal cord injury. Paraplegia. 1991;9:573–581. doi: 10.1038/sc.1991.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]