Abstract

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-specific serum antibody has been correlated to protection of infection and reduction of severe disease, but reinfection is still frequent. In this study, we evaluated RSV-specific serum antibody activity following natural RSV re-infection to examine the longevity of the humoral immune response in adults. Nineteen healthy adult volunteers under sixty-five years of age were enrolled during the 2018–2019 RSV season in Houston, TX. Blood was collected at three study visits. The kinetics of RSV-neutralizing, RSV F site-specific competitive, and RSV-binding antibodies in serum samples were measured by microneutralization and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. Three distinct profiles of RSV-specific antibody kinetics were identified that were consistent with RSV infection status: uninfected, acutely infected, and recently infected. The uninfected group had stable antibody titers for the duration of the study period (185 days). The acutely infected group had lower antibody responses at the beginning of the study, supporting a correlate of infection, followed by a significant antibody response after infection that was maintained for at least 125 days. Unlike the acutely infected group, the recently infected group had a significant precipitous decrease in RSV antibody in only 60 days.This study is the first, to our knowledge, to describe this abrupt loss of RSV-specific antibody in detail. This rapid decline of antibody may present an obstacle for the development of vaccines with lasting protection against RSV, and perhaps other respiratory pathogens. Neutralizing antibody responses were greater to prototypic than contemporaneous RSV strains, regardless of infection status, indicating that original antigenic sin may impact the humoral immune response to new or emerging RSV strains.

Keywords: Neutralizing antibody, competitive antibody, binding antibody, original antigenic sin, vaccine, respiratory viruses

1. Introduction

Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) is the leading cause of childhood acute lower respiratory illness worldwide [1]. RSV is also becoming increasingly appreciated as a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in older adults [2–5]. The development of a successful RSV vaccine is therefore an urgent priority for these populations that are at greatest risk. An incomplete understanding of the correlates of immunity for each of these populations has slowed vaccine development.

An association between RSV neutralizing antibody titers and reduction of severe disease has been established in both young children [6–8] and older adults [9–11]. The main targets of the neutralizing antibody response are the G (attachment) and the F (fusion) proteins, which are surface glycoproteins [12]. Whereas the G protein is highly variable, the F protein is relatively conserved among the two antigenically distinct subtypes, RSV/A and RSV/B [13–15]. The F protein is, therefore, a major target for vaccine development. The F protein mediates fusion between the viral and host membranes and undergoes conformational changes on the surface of the virus between the metastable prefusion form to the stable postfusion form. Six antigenic sites have been identified that are either specific for the prefusion (sites Ø, III, & V), postfusion (site I), or are shared between the two major conformations (sites II & IV). Understanding the kinetics of neutralizing antibodies and how they relate to the repertoire of F site-specific competitive antibodies elicited in response to community-acquired RSV infection will be critical in the design and evaluation of vaccines for the prevention of RSV.

In this report, we describe the kinetics of neutralizing antibodies, F site-specific competitive antibodies, as well as IgA, IgG, and IgM RSV-binding antibodies in healthy adults over an RSV season. We identified three distinct RSV-specific profiles of antibody kinetics that were consistent with an RSV infection status: uninfected, acutely infected, and recently infected. The different antibody profiles identified indicate a subpopulation of people who may not maintain a durable antibody response to vaccines. Our findings furthermore suggest the need for characterizing patient-specific responses to respiratory viral infections, a timely topic.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

Healthy adults (see below for exclusion criteria) were eligible for enrollment into a longitudinal prospective study during the 2018–2019 RSV season in Houston, Texas. Blood samples were collected in CPT and SST tubes at three time points (visits 1, 2, and 3). The CPT blood samples were processed for peripheral blood mononuclear cells to be used for future studies on cellular immunity and the SST tubes were processed for serum for antibody studies. Participants were asked to self-report respiratory symptoms. A mid-turbinate swab sample was collected during any reported acute respiratory illness (ARI) and tested for respiratory viruses in our Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA)-certified molecular diagnostic laboratory.

2.2. Ethics Statement

The institutional review board at Baylor College of Medicine approved the study protocol and written informed consent was obtained from all enrolled participants.

2.3. Enrollment Criteria

Healthy adults (18–64 years old) were enrolled in this study and followed for the duration of a single RSV season. Exclusion criteria consisted of having an acute illness within two weeks prior to enrollment; known pregnancy; immunosuppression as a result of underlying illness; use of oral or parenteral steroids, high-dose inhaled steroids, or other immunosuppressive or cytotoxic agents; active neoplastic disease or history of any hematologic malignancy; acute or chronic condition that would interfere with the evaluation of immune responses; use of experimental vaccines or medications within the month prior to study entry, or expected use of experimental vaccines or blood/blood products prior to study completion.

2.4. RSV-Specific Microneutralization Assay

Heat-inactivated serum samples were analyzed for neutralizing antibodies against prototypic (RSV/A/Tracy and RSV/B/18537) and contemporaneous (RSV/A/Ontario and RSV/B/Buenos Aires) strains in HEp-2 cells using qualified microneutralization assays as previously described [9, 16, 17]. Neutralizing antibody titers were defined as the highest dilution at which there was a ≥ 50% reduction in viral cytopathic effect. Any serum sample resulting in a titer less than the lower limit of detection (LLoD) (2.5 log2) was assigned a value of 2 log2 as described in [18].

2.5. Real-Time Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction

Real-time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (rtRT-PCR) assays were 1-step, singleplex assays performed in our CLIA-certified respiratory virus diagnostic laboratory (CLIA identifier 45D0919666) as previously described [19]. Genomic materials for the following respiratory pathogens were tested: RSV A and B; human rhinovirus (HRV); influenza virus types A. B and C; human coronaviruses (hCoVs) NL-63, HKU1, OC43, and 229E; parainfluenza virus (PIV) types 1, 2, 3 and 4; human metapneumovirus (hMPV); adenovirus; and bocavirus; Mycoplasma pneumoniae; and Bordetella pertussis. The human housekeeping gene (RNase-P) also was included for determining the quality of the respiratory samples.

2.6. Definition of RSV Infection

RSV infection was assessed by two accepted methods: serology and rtRT-PCR. Serological-based RSV infection occurred when there was a four-fold or greater rise in neutralizing antibody titers between any two sequential visits detected by one or more of the four RSV qualified microneutralization assays [9, 16, 17]. Volunteers with less than a four-fold change in neutralizing activity over the course of the season were defined as uninfected and those with a four-fold or greater decrease in neutralizing antibody titer by one or more of the RSV microneutralization assays at their second visit were defined as having a recent infection prior to enrollment, indicating we missed their baseline titer prior to their RSV infection. Whereas rtRT-PCR methods are highly specific for defining the timing of the RSV infection, RSV can be largely asymptomatic in healthy younger adults, may shed for only a few days, or may have low viral loads, so serological-based methods can be more sensitive for detection of RSV infection within a distinct period in this population.

2.7. Competitive Antibody Assays to Antigenic Sites of F Protein

Competitive antibody assays were used for four antigenic sites on the F protein. Serum concentrations of D25-competing antibody (site Ø), 131–2A-competing antibody (site I), palivizumab-competing antibody (site II), and 101F-competing antibody (site IV) that compete with biotinylated monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for binding to the respective antigenic site on the RSV F protein were measured as described previously [20, 21]. The mAbs and their sources were D25 and 101F (Cambridge Biologics, LLC, Brookline, MA, USA), palivizumab (MedImmune, LLC, Gaithersburg, MD, USA), and 131–2A (EMD Millipore Corporation, Temecula, CA, USA). A four-parameter logistic regression model was used to calculate the competitive antibody concentrations (μg/mL) that resulted in ≥ 50% inhibition. The LLoD was 1.0 μg/mL for site I, II, and IV competitive antibody assays, and 7.8 μg/mL for site Ø competitive antibody assay. Samples with a concentration below the LLoD were assigned a value of 0.5 and 3.9 μg /mL, respectively, as described in [19].

2.8. Isotype Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

The isotype composition (IgA, IgG, and IgM) of RSV-specific binding antibodies present in serum samples was analyzed for responses against various forms of the RSV F protein: prefusogenic F (Novavax, Bethesda MD), post F (Sinobiological, Chesterbrook, PA, Cat. #11049-V08B), or sucrose-purified RSV/A/Bernett (genotype GA1). Prefusogenic F, post F, or sucrose-purified (sp)RSV (200 ng/mL) was coated onto Immulon 2HB 96-well plates (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) in 100 μL. Human IgA, IgG, or IgM (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) were added in duplicate followed by 2-fold serial dilutions for generating a standard curve on each test plate. Plates were incubated for 18 h at 4°C and subsequently blocked for 1 h with 5% milk (Carnation Instant Nonfat Dry Milk) in 1X KPL at 36°C. Two-fold serial dilutions of serum samples were added, followed by a 1 h incubation at 36°C. Conjugated anti-human IgA, IgG (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), or IgM (Biolegend, San Diego, CA) were pre-absorbed to remove cross reactivity to non-targeted isotypes. Anti-human IgA (HRP-labeled), IgG (biotinylated), or IgM (biotinylated) secondary antibodies were added followed by a 1 h incubation at 36°C. After washing, HRP-conjugated streptavidin (SeraCare Life Sciences, Gaithersburg, MD) was added for an additional hour for plates detecting IgG or IgM. The substrate, 3,3',5,5'-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB, SeraCare Life Sciences, Gaithersburg, MD) was added to IgA, IgG, and IgM ELISAs for 16–18 minutes, and the reaction was stopped with 0.16 M sulfuric acid. The plates were read at 450 nm. Wells without biotinylated secondary antibodies contained 5% milk instead of sera or sera only as negative controls. A four-parameter logistic regression model was used to calculate the binding antibody concentrations (ng/mL). The LLoD was 8 ng/mL for IgA and IgG binding assays and 16 ng/mL for IgM binding assays. Samples with a concentration below the LLoD were assigned a value of 4 and 8 ng/mL, respectively [19].

2.9. Human Metapneumovirus-Specific Microneutralization Assay

Low passage (passage 6) hMPV/A/RLbx was used in the microneutralization assay. hMPV/A/RLbx was originally isolated on March 11, 2002 from a hospitalized child with lower respiratory tract illness. Sanger sequencing was performed on the F gene. The F gene encodes a protein that contains the S101P mutation at the cleavage site, rendering hMPV/A/RLbx trypsin-independent [22], ideal for use in our standard microneutralization assay that is performed for RSV[23].

Heat-inactivated human sera were analyzed for neutralizing antibodies (Nt Ab) against hMPV/A/RLbx in LLC-MK2 cells using an optimized microneutralization assay as previously described for RSV and hMPV with modifications [22–25]. Samples were diluted initially 1:8 and additionally via two-fold serial dilutions. An equal volume of hMPV/A/RLbx was added to each dilution and incubated at 36ºC with 5% CO2 for 1.5 hours. One hundred μL of LLC-MK2 trypsinized cells were added to 96-well plates and placed in the incubator for 6–7 days until the virus positive control wells had reached 100% cytopathic effect. Twenty-four hours later, the plates were fixed with 10% neutral formalin and 0.001% crystal violet. Neutralizing antibody titers were defined as the final dilution at which there was a 50% reduction in viral cytopathic effect. Any sample resulting in a titer <LLoD (2.5 log2) was assigned a value of 2 log2. hMPV infection occurred when there was a four-fold or greater rise in neutralizing antibody titers between any two sequential visits detected by the microneutralization assay and or by rtRT-PCR. Volunteers with less than a four-fold change in neutralizing activity over the course of the season were defined as uninfected and those with a four-fold or greater decrease in neutralizing antibody titer at their second visit were defined as having a recent infection prior to enrollment, indicating we missed their baseline titer prior to their hMPV infection.

2.10. Statistical Analyses

A repeated measures mixed model was performed for each strain to test for differences in the means of log2 transformed GMNAT, isotype-specific binding antibody concentrations (ng/mL), and F site-specific competitive antibody concentrations (μg/mL) among the three groups and three study visits. Pairwise comparisons were performed of the post-estimated mean log-transformed antibody concentrations among the three groups. Statistical significance (with greater than 95% confidence) was indicated for P values ≤ 0.05. No correction was made for multiple comparisons. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated between F site-specific competitive antibody concentrations and each of the RSV/A and RSV/B neutralizing antibody titers. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata 14 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas).

3. Results

3.1. Demographics, the RSV Season, and Virus Detection

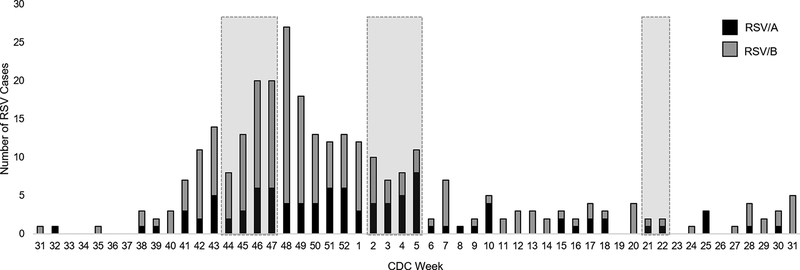

Nineteen adults were enrolled and completed the study (Table 1). The first visit (November 2018) occurred early in the RSV season, the second visit (January 2019) occurred after the peak of the season, and the third visit (May 2019) was at the end of the RSV season (Fig 1). RSV/B viruses accounted for the dominant RSV subtype circulating in the Houston area (Fig 1). During the study, a total of 13 study participants reported an acute respiratory illness (ARI). A mid turbinate nasal swab was collected at time of illness and tested by rtRT-PCR. A respiratory pathogen was identified in 11 of the 13 ARIs, two of which were co-infections (Table 1). None of the 13 reported ARIs tested positive for RSV by this method.

Table 1.

Demographics of enrolled adults by infection statusa.

| Characteristics | Uninfected | Acutely Infected | Recently Infected |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 12 | 4 | 3 |

| Age (yr), mean ± SD | 37.5 ± 11.2 | 40.0 ± 17.3 | 46.3 ± 13.4 |

| 18–34, % (n) | 50.0 (6) | 50.0 (2) | 33.3 (1) |

| 35–49, % (n) | 33.3 (4) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

| 50–64, % (n) | 16.7 (2) | 50.0 (2) | 66.7 (2) |

| Female, % (n) | 58.3 (7) | 50.0 (2) | 33.3 (1) |

| Race, % (n) | |||

| White | 41.6 (5) | 75.0 (2) | 33.3 (1) |

| Black | 16.7 (2) | 25.0 (1) | 0.0 (0) |

| Asian | 33.3 (4) | 0.0 (0) | 66.7 (2) |

| Other | 8.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 0.0 (0) |

| Ethnicity, % (n) | |||

| Hispanic | 8.3 (1) | 0.0 (0) | 33.3 (1) |

| Non-Hispanic | 91.7 (11) | 100.0 (4) | 66.6 (2) |

| Individuals with self-reported ARIb, n (# ARIs) | 8 (10)c | 2 (3)c | 0 (0) |

Infection status was defined by changes in neutralizing antibody titers and includes: uninfected (n = 12), acutely infected (n = 4), and recently infected (n = 3).

No individuals had an acute RSV-positive ARI detected by PCR.

Some individuals reported multiple ARIs during the study duration. cTwo ARIs in the uninfected group were co-viral infections. ARI, acute respiratory illness.

Fig 1. Sampling times during the 2018–2019 RSV season.

Healthy adult volunteers were enrolled in a prospective, observational surveillance study during the 2018–2019 RSV season. Blood was collected at three study visits (shaded boxes) during the early RSV season, after peak RSV season, and late RSV season, based upon RSV surveillance data from Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston, TX, USA. The season is shown by CDC weeks.

3.2. RSV Neutralizing Antibody Titer by Infection Status

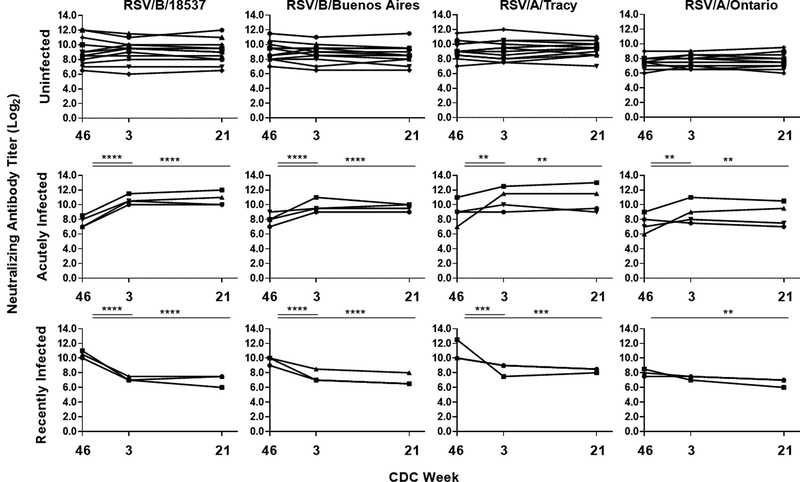

RSV infections were defined by serology, an accepted standard in the field. Three groups were identified based on their neutralizing antibody kinetics: uninfected (n = 12), acutely infected (n = 4), and recently infected (n = 3), as illustrated in Fig 2. The acutely infected group experienced a statistically significant increase in the geometric mean neutralizing antibody titer (GMNAT) by all four microneutralization assays (prototypic viruses: RSV/B/18537 and RSV/A/Tracy and contemporaneous virus: RSV/B/Buenos Aires and RSV/A/Ontario) between the first and second visits. All four individuals had a four-fold or greater rise in neutralizing antibody by at least one of the four microneutralization assays (Supplementary Table 1). The recently infected group had a significant decrease in the GMNAT by all the microneutralization assays except RSV/A/ON between the first and second visits. A four-fold or greater decline in neutralizing antibody titer was detected by at least two of the four microneutralization assays for all individuals in the recently infected group. The uninfected group had a stable GMNAT shown by all four microneutralization assays throughout the three study visits. The GMNAT and fold change for the neutralizing antibody activity by infection status and study visit are shown in Table 2. All four microneutralization assays generated comparable trends in their longitudinal kinetic data, but the RSV/A/ON assay generally resulted in lower fold changes in GMNATs by RSV infection status and study visit (Table 2). The RSV/B microneutralization assays detected the greatest fold changes in neutralizing antibody titers between the first and second visits for the acutely infected and recently infected groups. The older prototypic rather than the contemporaneous strains generated higher neutralizing antibody responses for both RSV/A and RSV/B subtypes (Fig 2 and Table 2).

Fig 2. Kinetics of RSV neutralizing antibody titers of individual study participants.

Neutralizing antibody titer was measured by microneutralization assays to prototypic (RSV/B/18537 and RSV/A/Tracy) and contemporaneous (RSV/B/Buenos Aires and RSV/A/Ontario) RSV strains at three study visits over the course of the 2018–2019 RSV season by infection status. Infection status includes: uninfected (n = 12), acutely infected (n = 4), and recently infected (n = 3). Neutralizing antibody is expressed in log2. The lower limit of detection is 2.5 log2. Each line represents one subject. Significant pairwise comparisons in post-estimated GMNAT (shown in Supplemental Table 2) between visits within each group are indicated as: *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001.

Table 2:

Neutralizing antibody responses to RSV by infection statusa

| GMNAT log2 (95% CI) | Fold Change | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RSV/B/18537 | 1st Visit | 2nd Visit | 3rd Visit | Visit 1 to 2 | Visit 1 to 3 | Visit 2 to 3 |

| Uninfected | 9.1 (7.9–10.2) | 9.1 (8.1–10.1) | 9.0 (8.0–10.0) | 1.05 | 0.97 | −1.08 |

| Acutely Infected | 7.6 (6.4–8.8) | 10.6 (9.6–11.6) | 10.8 (9.2–12.3) | 8.08 | 8.70 | 1.08 |

| Recently Infected | 10.5 (9.3–11.7) | 7.2 (6.4–7.9) | 7.0 (4.8–9.2) | −10.05 | −11.55 | −1.15 |

| RSV/B/Buenos Aires | ||||||

| Uninfected | 9.0 (8.2–9.8) | 8.8 (8.0–9.6) | 8.7 (7.8–9.5) | 1.16 | 1.3 | −1.13 |

| Acutely Infected | 8.0 (6.7–9.3) | 9.8 (8.4–11.1) | 9.6 (8.9–10.4) | 3.37 | 3.13 | −1.08 |

| Recently Infected | 9.7 (8.2–11.1) | 7.5 (5.3–9.7) | 7.0 (4.8–9.2) | −4.55 | −6.45 | −1.42 |

| RSV/A/Tracy | ||||||

| Uninfected | 9.2 (8.4–9.9) | 9.2 (8.3–10.1) | 9.3 (8.6–10.0) | 1.01 | 1.1 | 1.08 |

| Acutely Infected | 9.0 (6.4–11.6) | 10.8 (8.3–13.2) | 10.8 (7.8–13.7) | 3.43 | 3.35 | −1.02 |

| Recently Infected | 10.8 (7.2–14.4) | 8.5 (6.3–10.7) | 8.3 (7.6–9.1) | −4.93 | −5.43 | −1.1 |

| RSV/A/Ontario | ||||||

| Uninfected | 7.5 (7.0–8.0) | 7.6 (7.1–8.2) | 7.6 (7.0–8.3) | 1.09 | 1.07 | −1.01 |

| Acutely Infected | 7.5 (5.4–9.6) | 8.9 (6.4–11.3) | 8.6 (6.0–11.3) | 2.57 | 2.13 | −1.21 |

| Recently Infected | 8.0 (6.8–9.2) | 7.3 (6.6–8.1) | 6.7 (5.2–8.1) | −1.58 | −2.53 | −1.6 |

Geometric mean neutralizing antibody titers (log2) and fold change for each group of volunteers to prototypic (RSV/B/18537 and RSV/A/Tracy) and contemporaneous (RSV/B/Buenos Aires and RSV/A/Ontario) isolates.

Infection status was defined by either an RSV-positive acute respiratory illness or changes in neutralizing antibody titers and includes: uninfected (n = 12), acutely infected (n = 4), and recently infected (n = 3). Fold change in neutralizing antibody titer between study visits is shown. GMNAT, geometric mean neutralizing antibody titer; CI, confidence interval.

Geometric mean neutralizing antibody titers (log2) and fold change for each group of volunteers to prototypic (RSV/B/18537 and RSV/A/Tracy) and contemporaneous (RSV/B/Buenos Aires and RSV/A/Ontario) isolates. aInfection status was defined by either an RSV-positive acute respiratory illness or changes in neutralizing antibody titers and includes: uninfected (n = 12), acutely infected (n = 4), and recently infected (n = 3). Fold change in neutralizing antibody titer between study visits is shown. GMNAT, geometric mean neutralizing antibody titer; CI, confidence interval.

The acutely infected group had an RSV/B GMNAT that trended lower at the first study visit than individuals who remained uninfected. At the second visit, acutely infected volunteers had an increase in GMNAT response that ranged from 2.5- to 8-fold, depending on the RSV isolate used in the microneutralization assay. In contrast, the volunteers that had a recent infection at the time of enrollment had a precipitous drop in GMNAT at the second visit ranging from 1.6- to 10-fold. Even though a drop in neutralizing antibody activity was observed in the recently infected group, the peak GMNAT of both those acutely and recently infected were similar. At the third study visit, the GMNAT for all three groups were unchanged from their second study visit.

3.3. RSV F Site-Specific Competitive Antibody Concentrations by Infection Status

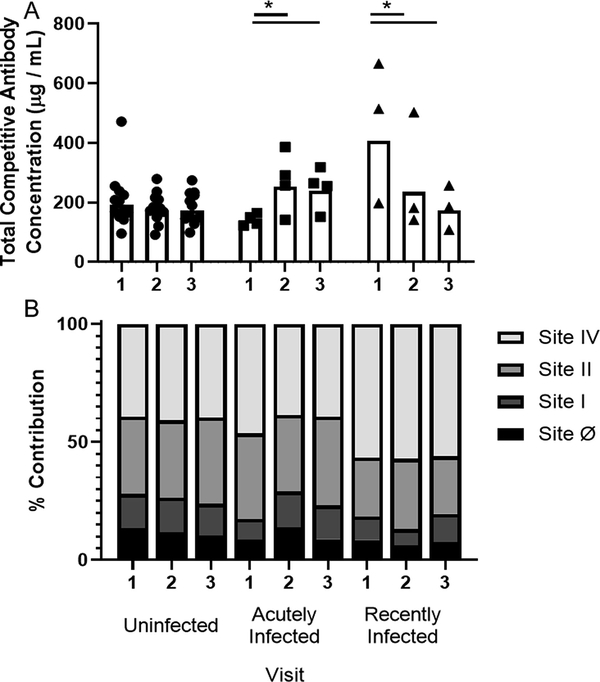

We tested the composition of the neutralizing antibody activity using site-specific competitive antibody ELISAs toward sites Ø, I, II, and IV of the F protein. The total site-specific competitive antibody geometric mean concentrations (CA-GMC) of each group followed similar patterns to the observed kinetics of the neutralizing antibody response (Fig 3A and Supplementary Fig 1). Volunteers that remained uninfected had a stable total CA-GMC over the course of the RSV season. Acutely infected volunteers started the season with approximately 20% less total CA-GMC than volunteers that remained uninfected. The acutely infected group had a significant increase in total CA-GMC at the second study visit. The recently infected group had an approximately two-fold higher total CA-GMC at the first visit compared to the uninfected group, which was driven primarily by responses towards site IV. At the third visit, the total CA-GMC levels from the recently infected group declined to levels similar to those of the uninfected group.

Fig 3. Site-specific competitive antibody responses.

Four antigenic site-specific competitive antibody assays were used to measure serum concentrations of antibody that compete with biotinylated mAbs for binding to their respective antigenic site on the RSV fusion protein as described previously20,21. Monoclonal antibodies used include: D25 (site Ø), 131–2A (site I), palivizumab (site II), and 101F (site IV). Shown are (A) total geometric mean concentrations (CA-GMC), or (B) percent of each RSV antigenic site-specific CA-GMC (μg/mL) to the total CA-GMC (μg/mL) responses by infection status. Infection status includes: uninfected (n = 12), acutely infected (n = 4), and recently infected (n = 3). Significant pairwise comparisons in post-estimated CA-GMC of each group are indicated (*P ≤ 0.05).

To facilitate comparison among the four antigenic sites, we show the mean percent contribution of each in Fig 3B and Supplementary Fig. 2. The uninfected group had a stable contribution by the four site-specific competitive antibodies over the course of the season, with the proportion of sites II and IV competitive antibodies being two-fold and three-fold higher than the proportion of competitive antibodies to site Ø and I, respectively. The acutely infected group had a significant increase in the proportion of competitive antibody to site I and a significant decrease to site IV at study visits 2 and 3. The recently infected group percent contribution by the site-specific competitive antibodies were stable except for those that targeted the post-fusion site, site I.

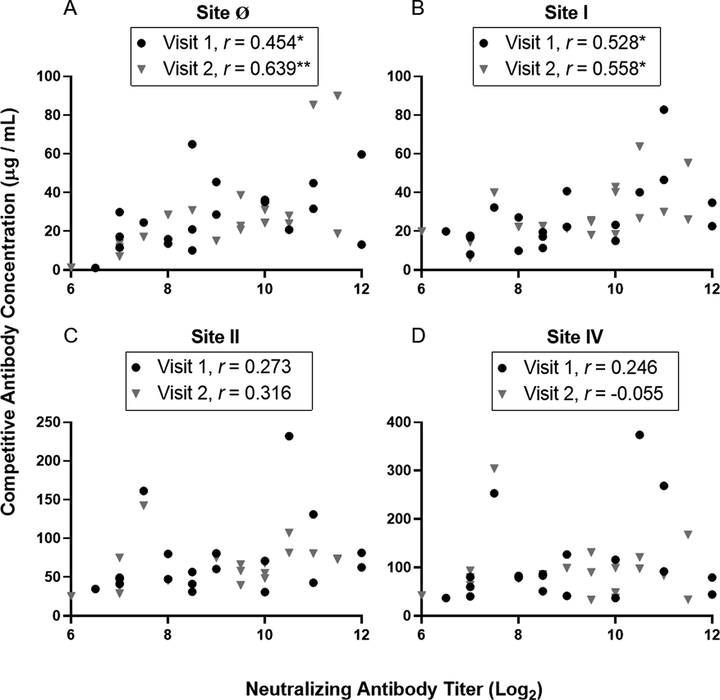

3.4. Correlation of RSV F Site-Specific Competitive Antibodies and Neutralizing Antibodies

The RSV F site-specific competitive antibody concentration was compared to the RSV-specific neutralizing antibody titers (Fig 4). Results to RSV/B/18537 and RSV/A/ON are shown representing the strongest and weakest correlations (Fig 4 and Supplementary Fig. 3). Both site Ø and site I competitive antibody concentrations strongly correlated with RSV/B/18537 neutralizing antibody titers across all three study visits. Site II competitive antibody concentrations only correlated with neutralizing antibody titers at the third study visit and site IV competitive antibody concentrations did not correlate with neutralizing antibody titers at any of the three study visits (data not shown).

Fig 4. Correlation of RSV antigenic site-specific competitive antibody concentrations and neutralizing antibody titers to RSV/B/18537 at study visits 1 and 2.

Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to measure the strength of the linear association between the neutralizing antibody titer to RSV/B/18537 and competitive antibody concentrations to (A) site Ø, (B) site I, (C) site II, (D) site IV (n = 19). Significant correlations are indicated (*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01).

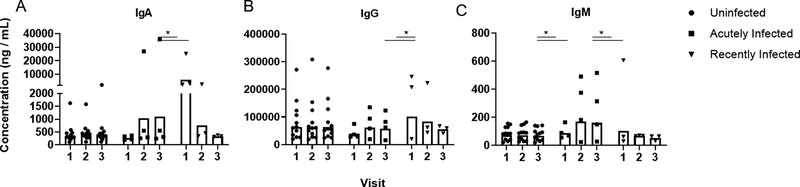

3.5. RSV Binding Antibody Concentration by Infection Status

Using RSV-binding antibody assays, we further explored the changes of neutralizing antibody activity in the acutely infected and recently infected groups. The isotype composition of binding antibody to the prefusogenic conformation of F, which is used in an RSV-F vaccine (Novavax, Bethesda, MD), as well as to post F and sucrose-purified RSV was assessed (Fig 5 and Supplementary Fig. 3). IgA, IgG, and IgM binding activity against the three forms of F protein generated similar trends in their longitudinal kinetic data by RSV infection status. IgA and IgM responses were similar to those for IgG except that there was larger variability in the responses from individuals within each group (Fig 5). The levels of anti-RSV binding IgG mimicked the neutralizing antibody response. Uninfected individuals had a stable response throughout the season. Acutely infected individuals had two-fold less binding antibody at the first visit compared to uninfected individuals, which then trended higher after infection, similar to levels of uninfected volunteers. Finally, the recently infected individuals had two-fold higher levels of binding antibody at the first visit that returned to similar levels as uninfected individuals.

Fig 5. RSV-specific binding antibody to prefusogenic F protein.

The geometric mean concentration of the isotype composition (A) IgG, (B) IgA, and (C) IgM of RSV-specific binding antibodies present in serum samples was analyzed for responses against the prefusogenic form of the F protein (Novavax, Bethesda, MD) by infection status. Infection status includes: uninfected (n = 12), acutely infected (n = 4), and recently infected (n = 3). Significant differences in the geometric mean concentrations of each group are indicated (*P ≤ 0.05).

3.6. hMPV-Specific Neutralizing Antibody Titer

To test whether the rapid loss in antibody titer observed in the recently infected RSV group was RSV-specific or a consequence of deficits in overall immunoglobulin levels of these individuals, we evaluated the neutralizing antibody titers to a different respiratory pathogen, hMPV, over the duration of the study (Supp Fig 5). We detected four acute hMPV infections by serology, one of which was also detected by rtRT-PCR (data not shown). Two hMPV infections occurred between the first two study visits and two occurred later in the respiratory season between the second and third study visits. Three of the hMPV infections were identified in individuals who were in the uninfected RSV group, and the fourth was an individual in the recently infected RSV group. One individual in the acutely infected RSV group had a four-fold drop in hMPV neutralizing antibody titers between the first and second study visit, consistent with a recent hMPV infection prior to enrollment. hMPV GMNATs were comparable for all three RSV infection status groups (data not shown).

Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the kinetics of functional and binding antibodies to RSV in healthy adults. We identified three distinct RSV-specific antibody profiles over the course of the 2018–2019 RSV season: uninfected, acutely infected, and recently infected. While the antibody profile of the acutely infected group was consistent with previous studies on the antibody response to RSV infection, the rapid decline in both the functional and binding RSV-specific antibody titers in the latter group was unexpected.

Volunteers who had serologic evidence of RSV infection had lower functional and binding RSV-specific antibody activity at enrollment, consistent with a correlate of infection as seen in previous studies [9, 11]. In their subsequent visit 60 days later, significant rises in the GMNAT were detected by all four microneutralization assays. The greatest fold rises were detected with RSV/B/18537 and RSV/B/BA microneutralization assays. This trend is consistent with RSV surveillance data that indicated that it was predominately an RSV/B outbreak in Houston, TX. In contrast to the recently infected group, the functional and binding RSV-specific antibody titers remained stable over the subsequent 125 days without any significant changes except for a significant decrease in the competitive antibody concentration to site Ø. The serologic antibody responses observed in these healthy adults are consistent with the serologic responses observed in RSV-confirmed infections in hematopoietic stem cell transplant adults [16, 17]. The observed antibody response kinetics are also consistent with that of natural infection in healthy adults and in vaccinated children in which antibody responses decayed back to baseline within 16 months at a rate of 0.2 log2 per 30 days [16, 26].

Although infection profiles were assigned by microneutralization responses (and not through rtRT-PCR), the recently infected group was unique in having a precipitous drop in antibody activity within a short period after the first study visit by all assays tested. Individuals with a recent infection likely encountered RSV early in the 2018 winter outbreak and prior to study enrollment. Our finding that recently infected study participants and those with acute infections had similar GMNAT peak responses indicates that the recently infected volunteers were able to generate high levels of functional antibodies but were not able to maintain those levels over prolonged periods like the acutely infected individuals could. An inability to sustain high levels of functional antibodies after a recent infection would likely place these adults at increased risk for reinfection.

A previous study reported an individual who had two documented RSV infections within a single RSV season [26]. Similar to what we observed here, this individual experienced a precipitous drop (> four-fold) in neutralizing antibody titers following both infection events. In addition, all individuals in the RSV recently infected group maintained or had significant rises in hMPV neutralizing antibody titers, indicating the observed rapid loss of antibody was RSV-specific and not due to a sample quality issue nor was a consequence of unknown physiological conditions affecting overall immunoglobulin levels. Interestingly, one individual with an acute RSV infection experienced rapid hMPV antibody loss, indicating that an inability to maintain antibodies may occur for hMPV as well. The underlying immune mechanism of this phenomenon warrants further investigation [27].

The prototypic RSV/B/18537 (GB1 genotype) and RSV/A/Tracy (GA1 genotype) microneutralization assays detected greater fold-changes in neutralizing antibody activity compared to their contemporaneous counterparts. As the viral inoculum used is equal among all four microneutralization assays, this was a relatively unexpected result. One potential explanation is that the lower fold changes observed with the newer genotypes might be due to original antigenic sin, which implies that the first RSV infection impacts the subsequent antibody responses to RSV re-infections [28]. The contemporaneous genotypes RSV/B/Buenos Aires and RSV/A/Ontario did not arise as the dominant circulating genotypes until approximately 2004 and 2012, respectively [29, 30]. As all children have had their primary RSV infection by the age of three [31], all the adults in this study would have had their first encounter with RSV before 1997. It is therefore likely that the RSV they first encountered more closely reflected the prototypic rather than contemporaneous RSV genotypes. The concept of original antigenic sin impacting antibody responses has been well established for other viral pathogens, such as influenza and dengue [32, 33]. Better understanding the role original antigenic sin plays in RSV reinfections will be fundamentally important in RSV vaccine development. A vaccine formulated to stimulate antibody diversification across genotypes could fortify the vaccine efficacy upon the emergence of new dominant strains.

There are several limitations in our study. First, the study had a small sample size. Although we identified three significantly distinct antibody responses, there may in fact be more ways people respond immunologically to RSV than we captured. Second, although we did not have a baseline antibody titer for the recently infected group, their responses were unique because of the precipitous drop in both functional and binding antibody activity. Third, no positive RSV infections were identified through rtRT-PCR from self-reported ARI over the course of the study. Because RSV infection is largely asymptomatic in healthy adults, can shed for only a few days, and can result in low viral loads, the serological-based methods, which are more sensitive than PCR methods for detection of RSV infection in this population, are likely sufficient to indicate RSV infection [9, 34]. Fourth, this study focused only on serum antibody responses. Mucosal antibody responses, particularly IgA, play a protective role against RSV infection and severe disease [35]. Therefore, future studies should also include evaluating mucosal samples for RSV-specific antibody responses. Finally, although this is one of few studies to assess F site-specific antibody responses, especially in healthy adults, we did not have accurate competitive antibody assays assess the contribution of the remaining two pre-F specific sites, site III and V. Thus, their contribution to the neutralizing antibody activity was not determined.

In conclusion, we have described three distinct antibody kinetic profiles in healthy adults over one RSV season. Our prospective cohort study indicates that as many as 16% of adults may not be able to maintain high levels of neutralizing antibody for sufficient periods of time. This unexpected and rapid loss of antibody in the recently infected group may prove to be a hurdle for vaccine development and it will be important to consider this group in the design of future vaccine trials. Finally, our data suggest that original antigenic sin might be influencing the RSV genotype-specific neutralizing antibody response. A better understanding of why some individuals are unable to maintain high levels of antibody or respond effectively to contemporaneous RSV genotypes will be useful in developing vaccines that can overcome these host immune deficits.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Serum antibody activity to natural RSV re-infection was studied in healthy adults.

Three distinct profiles of RSV-specific antibody kinetics were identified: uninfected, acutely infected, recently infected.

The recently infected group had an abrupt loss of RSV-specific antibody in only 60 days. Neutralizing antibody responses were greater to prototypic rather than contemporaneous RSVstrains.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Novavax (Bethesda, MD) for providing prefusogenic F protein for assay development. A preliminary version of these results was presented at the 5th Respiratory Syncytial Virus Vaccine for the World Conference in 2019.

Funding

Funding was from discretionary funds from PAP and BEG, and NIH grant R01GM115501 to LZ.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Potential conflicts of interest

All authors: No reported conflicts. All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Shi T, McAllister DA, O’Brien KL, Simoes EAF, Madhi SA, Gessner BD et al. Global, regional, and national disease burden estimates of acute lower respiratory infections due to respiratory syncytial virus in young children in 2015: a systematic review and modelling study. Lancet. 2017; 390: 946–58. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30938-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Shi T, Arnott A, Semogas I, Falsey AR, Openshaw P, Wedzicha JA et al. The etiological role of common respiratory viruses in acute respiratory infections in older adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2019. 10.1093/infdis/jiy662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Shi T, Denouel A, Tietjen AK, Campbell I, Moran E, Li X et al. Global disease burden estimates of respiratory syncytial virus-associated acute respiratory infection in older adults in 2015: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect Dis. 2019. 10.1093/infdis/jiz059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Matias G, Taylor R, Haguinet F, Schuck-Paim C, Lustig R, Shinde V. Estimates of hospitalization attributable to influenza and RSV in the US during 1997-2009, by age and risk status. BMC Public Health 2017; 17(1):271. 10.1186/s12889-017-4177-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Branche AR, Falsey AR. Respiratory syncytial virus infection in older adults: an under-recognized problem. Drugs Aging. 2015; 32(4):261–9. 10.1007/s40266-015-0258-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Piedra PA, Jewell AM, Cron SG, Atmar RL, Paul Glezen W. Correlates of immunity to respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)-associated hospitalization: establishment of minimum protective threshold levels of serum neutralizing antibodies. Vaccine. 2003; 21(24):3479–82. 10.1016/S0264-410X(03)00355-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Stensballe LG, Ravn H, Kristensen K, Agerskov K, Meakins T, Aaby P et al. Respiratory syncytial virus neutralizing antibodies in cord blood, respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization, and recurrent wheeze. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009; 123(2):398–403. 10.1016/j.jaci.2008.10.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Piedra PA, Hause AM, Aideyan L. Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV): neutralizing antibody, a correlate of immune protection. In: Tripp RA, Jorquera PA, eds. Human Respiratory Syncytial Virus: Springer; New York: 2016; 1442: 77–91. 10.1007/978-1-4939-3687-8_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Luchsinger V, Piedra PA, Ruiz M, Zunino E, Martínez MA, Machado C et al. Role of neutralizing antibodies in adults with community-acquired pneumonia by respiratory syncytial virus. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2012; 54(7):905–12. 10.1093/cid/cir955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Terrosi C, Di Genova G, Martorelli B, Valentini M, Cusi MG. Humoral immunity to respiratory syncytial virus in young and elderly adults. Epidemiol Infect 2009; 137(12):1684–6. 10.1017/S0950268809002593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Lee FE-H, Walsh EE, Falsey AR, Betts RF, Treanor JJ. Experimental infection of humans with A2 respiratory syncytial virus. Antiviral Res 2004; 63(3):191–6. 10.1016/j.antiviral.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].McLellan JS, Ray WC, Peeples ME. Structure and function of respiratory syncytial virus surface glycoproteins. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2013; 372:83–104. 10.1007/978-3-642-38919-1_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tapia LI, Shaw CA, Aideyan LO, Jewell AM Dawson BC Haq TR et al. Gene sequence variability of the three surface proteins of human respiratory syncytial virus (HRSV) in Texas. PloS One. 2014; 9(3):e90786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Hause AM, Henke DM, Avadhanula V, Shaw CA, Tapia LI, Piedra PA. Sequence variability of the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) fusion gene among contemporary and historical genotypes of RSV/A and RSV/B. PloS One 2017; 12(4):e0175792. 10.1371/journal.pone.0175792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Tan L, Coenjaerts FEJ, Houspie L, Viveen MC, van Bleek GM, Wiertz EJ et al. The comparative genomics of human respiratory syncytial virus subgroups A and B: genetic variability and molecular evolutionary dynamics. J Virol. 2013; 87(14):8213–26. 10.1128/JVI.03278-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Piedra PA, Grace S, Jewell A, Spinelli S, Bunting D, Hogerman DA et al. Purified fusion protein vaccine protects against lower respiratory tract illness during respiratory syncytial virus season in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1996; 15(1):23–31. 10.1097/00006454-199601000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Piedra PA, Wyde PR, Castleman WL, Ambrose MW, Jewell AM, Speelman DJ et al. Enhanced pulmonary pathology associated with the use of formalin-inactivated respiratory syncytial virus vaccine in cotton rats is not a unique viral phenomenon. Vaccine. 1993; 11(14):1415–23. 10.1016/0264-410X(93)90170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Singh A, Maichle R, Lee SE. On the computation of a 95% upper confidence limit of the unknown population mean based upon data sets with below detection limit observations. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; EPA/600/R-06/022, 2006. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Hause AM, Avadhanula V, Maccato ML, Pinell PM, Bond N, Santarcangelo P et al. A cross-sectional surveillance study of the frequency and etiology of acute respiratory illness among pregnant women. J Infect Dis. 2018; 218(4):528–35. 10.1093/infdis/jiy167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Ye X, Iwuchukwu OP, Avadhanula V, Aideyan LO, McBride TJ, Ferlic-Stark LL et al. Comparison of palivizumab-like antibody binding to different conformations of the RSV F protein in RSV-infected adult hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. J Infect Dis. 2018; 217(8):1247–56. 10.1093/infdis/jiy026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Ye X, Iwuchukwu OP, Avadhanula V, Aideyan LO, McBride TJ, Ferlic-Stark LL et al. Antigenic site-specific competitive antibody responses to the fusion protein of respiratory syncytial virus were associated with viral clearance in hematopoietic cell transplantation adults. Front Immunol. 2019; 10:706. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Schickli JH, Kaur J, Ulbrandt N, Spaete RR, and Tang RS. An S101P Substitution in the Putative Cleavage Motif of the Human Metapneumovirus Fusion Protein Is a Major Determinant for Trypsin-Independent Growth in Vero Cells and Does Not Alter Tissue Tropism in Hamsters. J Virol 2005;79(16):10678–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Piedra PA, Cron SG, Jewell A, Hamblett N, McBride R, Palacio MA, Ginsberg R, Oermann CM, Hiatt PW, Purified Fusion Protein Vaccine Study Group. Immunogenicity of a new purified fusion protein vaccine to respiratory syncytial virus: a multi-center trial in children with cystic fibrosis. Vaccine, 2003; 21:2448–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Wyde PR, Chetty SN, Jewell AM, Schoonover SL, Piedra PA. Development of a cotton rat-human metapneumovirus (hMPV) model for identifying and evaluating potential hMPV antivirals and vaccines. Antiviral Res, 2005; 66:57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Garcia DF, Hiatt PW, Jewell A, Schoonover SL, Cron SG, Riggs M, Grace S, Oermann CM, Piedra PA. Human metapneumovirus and respiratory syncytial virus infections in older children with cystic fibrosis. Ped Pul 2007;42:66–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Falsey AR, Singh HK, Walsh EE. Serum antibody decay in adults following natural respiratory syncytial virus infection. J Med Virol. 2006; 78(11):1493–7. 10.1002/jmv.20724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chen Y, Zuiani A, Fischinger S, Mullur J, Atyeo C, Travers M et al. Quick COVID-19 Healers Sustain Anti-SARS-CoV-2 Antibody Production. Cell. 2020. Nov 3;183(6):1496–1507.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.051. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Vatti A, Monsalve DM, Pacheco Y, Chang C, Anaya J-M, Gershwin ME. Original antigenic sin: A comprehensive review. J Autoimmun. 2017; 83:12–21. 10.1016/j.jaut.2017.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Avadhanula V, Chemaly RF, Shah DP, Ghantoji SS, Azzi JM, Aideyan LO et al. Infection with novel respiratory syncytial virus genotype Ontario (ON1) in adult hematopoietic cell transplant recipients, Texas, 2011-2013. J Infect Dis. 2015; 211(4):582–9. 10.1093/infdis/jiu473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Trento A, Galiano M, Videla C, Carballal G, García-Barreno B, Melero JA et al. Major changes in the G protein of human respiratory syncytial virus isolates introduced by a duplication of 60 nucleotides. J Gen Virol. 2003; 84(11):3115–20. 10.1099/vir.0.19357-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Glezen WP, Taber LH, Frank AL, Kasel JA. Risk of primary infection and reinfection with respiratory syncytial virus. Am J Dis Child. 1986;140(6):543–6. 10.1001/archpedi.1986.02140200053026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Zhang A, Stacey HD, Mullarkey CE, Miller MS. Original antigenic sin: How first exposure shapes lifelong anti-influenza virus immune responses. J Immunol. 2019; 202(2):335–40. 10.4049/jimmunol.1801149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rothman AL. Immunity to dengue virus: a tale of original antigenic sin and tropical cytokine storms. Nat Rev Immunol 2011; 11(8):532–43. 10.1038/nri3014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Moreira LP, Watanabe ASA, Camargo CN, Melchior TB, Granato C, Bellei N. Respiratory syncytial virus evaluation among asymptomatic and symptomatic subjects in a university hospital in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in the period of 2009-2013. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2018; 12(3):326–30. 10.1111/irv.12518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Habibi MS, Jozwik A, Makris S, Dunning J, Paras A, DeVincenzo JP et al. Mechanisms of Severe Acute Influenza Consortium Investigators. Impaired Antibody-mediated Protection and Defective IgA B-Cell Memory in Experimental Infection of Adults with Respiratory Syncytial Virus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015. May 1;191(9):1040–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2256OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.