Abstract

COVID-19 which emerged in Wuhan, China has rapidly spread all over the globe and the World Health Organisation has declared it a pandemic. COVID-19 disease severity shows variation depending on demographic characteristics like age, history of chronic illnesses such as cardio-vascular/renal/respiratory disease; pregnancy; immune-suppression; angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor medication use; NSAID use etc but the pattern of disease spread is uniform – human to human through contact, droplets and fomites. Up to 3.5% of health care workers treating COVID-19 contact an infection themselves with 14.8% of these infections severe and 0.3% fatal. The situation has spread panic even among health care professionals and the cry for safe patient care practices are resonated world-wide. Surgeons, anesthesiologists and intensivists who very frequently perform endotracheal intubation, tracheostomy, non-invasive ventilation and manual ventilation before intubation are at a higher odds ratio of 6.6, 4.2, 3.1 and 2.8 respectively of contacting an infection themselves. Elective surgery is almost always deferred in fever/infection scenarios. A surgeon and an anesthesiologist can anytime encounter a situation where in a COVID-19 patient requires an emergency surgery. COVID-19 cases requiring surgery predispose anesthesiologists and surgeons to cross-infection threats. This paper discusses, the COVID-19 precautionary outlines which has to be followed in the operating room; personal protective strategies available at present; methods to raise psychological preparedness of medical professionals during a pandemic; conduct of anesthesia in COVID-19 cases/suspect cases; methods of decontamination after conducting a surgery for COVID-19 case in the operating room; and post-exposure prophylaxis for medical professionals.

KEYWORDS: Anesthesia, COVID-19, emergency surgery, novel coronavirus 2019

INTRODUCTION

Emerging and re-emerging diseases[1] pose a constant threat to public health and add to the work exigencies of health-care professionals worldwide. Among these, air-borne or droplet-borne infections are the most feared considering their contagious nature and fast transmission.[2,3,4,5,6] Influenza and parainfluenza virus,[7] respiratory syncytial virus,[8] Cytomegalovirus, hanta virus,[9] and coronavirus infections are among those re-emerging infections that predispose to predominantly to lower respiratory infections. These infections can be self-limited to a tracheo-bronchitis in healthy individuals, but immunocompromised patients, elderly with multiple disease comorbidities, and pregnant females are more likely to develop life-threatening pneumonitis and adult respiratory distress syndrome.[10,11]

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a novel pneumonia syndrome which was first identified clustered around the Huanan Seafood market in Wuhan, China, in December 2019.[12,13] The causative agent is identified as a beta-coronavirus named as severe acute respiratory syndrome-coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), which is one among the seven strains of this virus that causes human infection.[14] Most beta-coronaviruses are endemic ones that causes common cold, but the fatal strains of beta-CoV caused the 2002 SARS outbreak (case fatality 10%),[15] 2012 Middle East respiratory syndrome (case fatality 40%),[16] and the present COVID-19 (case fatality 2%).[17] The number of patients generated after exposure to one COVID-19 patient is estimated to be 2.2–3.6.[18] Phylogenetic analysis traced to bats and ant eaters as the original host of the causative agent of 2019-nCoV. Human–human transmission of SARS-CoV-2 through droplet, fomites, and contact was identified by January 2020.[19] The 2019-nCoV rapidly spread internationally to almost all countries and territories of the globe.[20] As of April 8, 2020, 1,353,361 patients are infected globally and 79, 235 patients sustained mortality. The Indian statistics reveal 5194 patients infected and 149 mortalities as of April 9, 2020.[17] Considering the rapid spread, unavailability of treatment/vaccine,[21] and lethality of disease in vulnerable population group, the Government of India has announced nationwide shutdown and “curfew.”[22]

Infected individuals of 2019-nCoV are the main source of COVID-19 transmission at present.[23] Doctors, especially surgeons, anesthesiologists and intensivists, nurses, and other health-care workers, are at higher risk of droplet infections while caring for COVID-19 patients. Early statistics based on the Wuhan experience have shown up to a 3.5% of health-care workers treating COVID-19 contracting an infection themselves, with 14.8% of these infections severe and 0.3% fatal.[13] Physician fatality after hospital-acquired COVID-19 has also been reported from Wuhan.[24,25] Surgeons, anesthesiologists, and intensivists, who very frequently perform endotracheal intubation, tracheostomy, noninvasive ventilation, and manual ventilation before intubation, are at a higher odds ratio of 6.6, 4.2, 3.1, and 2.8, respectively, of contracting an infection themselves.[26,27,28] In this review, we intend to examine the various methods of safely anesthetizing and providing intraoperative care to a COVID-19 patient. There has been an exodus of literature on COVID-19 ever since January 2020, and as the disease is still spreading in its full fury, we are afraid that our review can be “old” by the time it is published, though we have made our best efforts to keep abreast with the most recent recommendations in this field.

LITERATURE SEARCH

We performed a PubMed and Google Scholar literature search using single text word and combinations of MeSH terms “COVID-19,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “2019-nCoV,” “Anaesthesia,” “Corona virus,” and “Emergency Surgery” from the year 2000 to April 2020. Relevant articles were collected electronically, and the references of those were manually searched further. The recommendations of the Chinese Society of Anaesthesiology based on their Wuhan experience,[29] Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain,[30,31] and selected institutional guidelines[32] were imbibed into for preparing this review.

PSYCHOLOGICAL PREPARATION OF DOCTORS, NURSES, AND HEALTH-CARE WORKERS

Elective surgery is almost always deferred in fever/infection scenarios. A surgeon and an anesthesiologist can anytime encounter a situation wherein a COVID-19 patient requires an emergency surgery.[33] Appraisal programs for doctors; health-care worker training; teaching social distancing at society level and workplace; adherence to proper hand hygiene practice; and psychological preparation are etiquette to prevent self- and cross-contamination. Novel social media applications can be effectively used to promote motivational message and ensure that images/videos of good practice models reach all health-care professionals. This is more relevant in the context that in pandemics like COVID-19, almost all hospitals are operating with limited staff, and there are restrictions imposed by state machinery on gathering of people, which itself is a factor facilitating airborne disease spread. The institutional mental health guidelines can be framed and distributed to doctors and health-care workers using novel social media applications to help them cope up with the stressful work atmosphere. The mental health and stress management guidelines we use at our institution[34] are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Mental health guidelines circulated among doctors, nurses, and paramedical professionals during the pandemic that focuses on working in stressful environments

| Mental health statement |

|---|

| As health workers you are now facing considerable mental tension. In the present context, it is natural and it does not indicate that you are not capable to perform or you don’t have the ability to perform |

| At this time , maintaining your mental health is as important as your physical health |

| Focus on your basic needs and choose healthy ways to reduce your mental tensions. In between shifts at workplace, make sure to take rest, take adequate quantity of healthy food, give required exercise to the body, while feeling stress talk to your friends or relatives over phone; avoid cigarette smoking and alcohol |

| Think about how you have overcome similar if not exactly same stressful situations in the past and adopt ways which you have employed |

| It is likely that some of you may be facing exclusion or rejection from family or the society. This may contribute to intensify your tension. Maintain contact with friends, superiors, or subordinates at the workplace because they may be also undergoing similar situation |

| If anybody in your team is facing mental or intellectual challenges, try to converse in a manner easy for them rather than always insisting on written communication |

| In this situation, you can help your colleagues cope up with stress and improve their efficiency |

| Ensure that all the staff receive correct information in a proper way, interchange them from more stressful job to less stressful job, follow buddy system by deploying experienced with inexperienced staff |

| Community outreach workers as much as possible instead of going in singles go in two’s. Make sure that they get adequate rest breaks |

| Such staff who may be going through any kind of mental stress, give flexible work |

| If you are a team leader guide your staff on sources of mental health support. Even you may need it for your own sake too and become a role model |

PERSONAL PROTECTIVE EQUIPMENT

The classification and user guidelines for personal protective equipment (PPE) are shown in Table 2. A level III scaled PPE is mandatory while anesthetizing any patient with COVID-19.[35,36] The merits of a positive pressure respirator or a powered air-purifying respirator (PPAR) over the N95/FFP2 mask are controversial at present.[37] In our scenario, the availability of PPAR is limited; hence, the use of N95/FFP2 mask gains an upper edge. Aerosol-generating clinical procedures such as endotracheal intubation have the highest risk of cross contamination. The anesthesiologist and the surgeon should understand that commonly performed clinical procedures can be cumbersome while using a PPE, and be psychologically prepared to meet the difficult situation. The PPE should be donned in the following sequence – put on scrubs and hair cover → perform hand wash → wear N95/FFP2 mask → wear inner gloves → wear coverall → wear eye protection (goggles/face shield) →wear foot protection → wear isolation gown → wear outer gloves → test the fit of the PPE components → ready to pass through. The PPE gowns may be prelabeled with the name of team member wearing it for ease of personal identification.[38] PPE should be donned in designated donning zone of the operation theater complex. The donning procedure needs to be monitored and can be assisted by an infection control nurse. Mock drills for donning and doffing of PPE should be conducted in anticipation as a part of hospital preparedness.[39,40,41,42]

Table 2.

Classification and user guidelines of personal protective equipment

| Type | Inclusions |

|---|---|

| Routine | Triple-layered medical maska, hand hygieneb, scrubs, glovesc ± |

| Level I | Triple-layered medical mask, Hand hygiene, scrubs, gloves, isolation gownd, disposable hair cover |

| Level II (for non-contact care of COVID-19/suspect patients) | N95/FF2/FFP3 maske, hand hygiene, scrubs, gloves, isolation gown, disposable hair cover, protective clothingf, shoe cover, eye protection± |

| Level III (direct contact with COVID-19/suspect patients) | N95/FF2/FFP3 mask, hand hygiene, scrubs, gloves, isolation gown, disposable hair cover, protective clothing, Shoe coverg, eye and face protectionh, head protection i(a positive pressure respirator may be used if available) |

±Use based on case to case basis. aA triple-layered medical mask is a disposable fluid-resistant mask, which provides protection to the wearer from droplets of infectious material emitted during coughing/sneezing/talking. The triple-layered mask has filtration efficacy of 99% for particles 3 µ and above, bAdhere to hand hygiene instructions published by the World Health Organization, cNitrile gloves are preferred over latex gloves because they resist chemicals, including certain disinfectants such as chlorine. There is a high rate of allergies to latex and contact allergic dermatitis among health workers. However, if nitrile gloves are not available, latex gloves can be used. Nonpowdered gloves are preferred to powdered gloves. Outer gloves should preferably reach mid-forearm, dcoverall/gowns are designed to protect torso of health-care providers from exposure to virus. Although coveralls typically provide 360-degree protection because they are designed to cover the whole body, including back and lower legs and sometimes head and feet as well, the design of medical/isolation gowns does not provide continuous whole-body protection (e.g., possible openings in the back, coverage to the mid-calf only). Light colors are preferable to better detect possible contamination, eAn N-95 respirator mask is a respiratory protective device with high filtration efficiency to airborne particles. To provide the requisite air seal to the wearer, such masks are designed to achieve a very close facial fit. Such mask should have high fluid resistance, good breathability (preferably with an expiratory valve), clearly identifiable internal and external faces, duckbill/cup-shaped structured design that does not collapse against the mouth. The N95 mask filters 95% of particles greater than 0.3 µ in size. FFP2 masks are the European Union-certified variants of N95 masks. The droplet filtration capability of FFP3 masks are greater (>99.95% for particles greater than 0.3 µ in size) than FFP2 masks, fBy using appropriate protective clothing, it is possible to create a barrier to eliminate or reduce contact and droplet exposure, both known to transmit COVID-19, thus protecting health-care workers working in close proximity (within 1 m) of suspect/confirmed COVID-19 cases or their secretions, gshoe covers should be made up of impermeable fabric to be used over shoes to facilitate personal protection and decontamination, hThe flexible frame of goggles should provide good seal with the skin of the face, covering the eyes and the surrounding areas and even accommodating for prescription glasses. Goggles should be fog and scratch resistant goggles with adjustable band to secure firmly so as not to become loose during clinical activity and there should be indirect venting to reduce fogging, iCoveralls usually cover the head. Those using gowns should use a head cover that covers the head and neck while providing clinical care for patients. Hair and hair extensions should fit inside the head cover. COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019

OPERATING ROOM PREPARATION

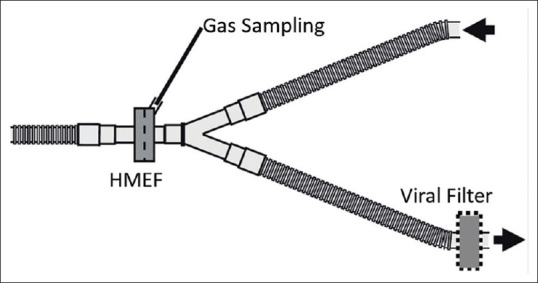

During the pandemic, dedicated operating room (OR) only for operating COVID-19 cases should be identified in the hospital. Such ORs should be labeled as “Septic OR” or “Infectious OR” with discretion of personnel entry inside. A summary of standard recommendations [Table 3] to be adhered to while undertaking a case of COVID-19 for surgery shall be pasted in multiple areas of the OR to facilitate easy recollection of each team member. Such pamphlets shall be a concise statement of institutional practice guidelines and are not be too extensive. The OR complex should have separate entry/exit area; donning and doffing area for PPE; and bath areas. Negative-pressure ORs[43,44] are ideally suited for COVID-19 cases, however the availability of such ORs is relatively scarce. Hence, positive pressure air circulation system in the septic OR is ideally to be kept off. The OR staff can easily get exhausted wearing the PPE in humid weathers and so the use of split air conditioners in the OR is at the discretion of the operating team subject to satisfactory decontamination of the OR after the surgery. The anesthesia machine dedicated for COVID-19 cases shall have a heat and moisture exchange (HME) filter at the patient end; and a high-quality bacterial and viral filter[45] should be attached to the machine end at expiratory port [Figure 1]. Gas sampling for capnography should be at the machine side of the HME filter. These filters need be replaced after every 3–4 h of use. High-quality filters offer a >99.99% viral filtration efficacy (VFE).[46,47] Adding another viral filter between the machine end and inspiratory port can be advised but not necessary to protect the machine from the patient nor to protect the patient if the machine is kept clean.[48,49]

Table 3.

Summary of personal protection practice to be adhered to by operating room team while handling coronavirus disease-19 case/suspect cases in the operation theater

| Institutional recommendations |

|---|

| Inform the COVID-19 committee about arrival of a COVID-19 case to OR |

| Use PPE with N95 face mask and eye protection |

| Ensure hand hygiene with soap and water hand wash; and alcohol hand rub. |

| All COVID-19 case/suspect cases to be operated only in designated COVID-19 OR |

| COVID-19 case/suspect cases should be operated by a senior operating surgeon and anesthesiologist; only assigned trainee resident doctors to enter the SOR |

| No mobile phones inside the COVID-19 OR |

| Only rapid sequence intubation in all COVID-19 case/suspect cases presenting for surgery to minimize infective aerosol generation |

| Use Video-laryngoscope as the first-line tool for intubation |

| Intra-operative point of care/lab blood samples to be transported only in “COVID-19” labeled secondary containers |

| COVID-19 OR door to be closed until completion of case; no movement of personnel inside the OR permitted until completion of case |

| On completion of case - PPE should be doffed with care in designated containers provided by hospital authorities; mandatory hand wash after removing PPE |

| Use double-concentration sodium hypochlorite for surface disinfection, followed by Sterilization as appropriate for re-usable equipment |

| Mandatory fumigation of COVID-19 OR after completion of case |

| Send the image of PPE Adherence and Provider safety checklist to COVID-19 committee, by e-mail soon after shift-out of case from OR |

| Do not hesitate to seek assistance of COVID-19 committee if there was any accidental breach in PPE |

OR: Operating room, PPE: Personal protective equipment, COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019, SOR: Septic operating room

Figure 1.

Diagrammatic representation of assembly of heat moisture exchange filter, high-quality viral filter and capnography gas sampling port (courtesy Drager medical)

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

Clinical categorizations of cases during the COVID-19 pandemic based on clinical features of patients[34,50] are described in Table 4. Early research has shown that older age group COVID-19 patients have a higher viral load in their throat swab samples.[51] Younger individuals within 1 week of symptom onset also have higher viral loads.[52] Critically ill patients may act as viral “shedders,” which is directly related to their infective viral load. Sputum samples show higher viral load compared to throat samples. Anesthesiologists are likely to receive (a) laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 cases, (b) suspect cases, (c) high-, and (d) low-risk contacts of laboratory-confirmed cases to the emergency OR [Table 5]. The exact patient definition is to be confirmed with the hospital COVID-19 committee before shift-in of patient to the OR. At this point of time, it is unclear whether the precautions that are adhered to for laboratory confirmed COVID-19 cases and suspect COVID-19 cases need be extended for intraoperative care of asymptomatic high-risk and low-risk contact individuals on home quarantine, though it is prudent to practice adherence to PPE universally in all symptomatic contacts irrespective of laboratory test being negative.

Table 4.

Patient categorization based on clinical features during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic

| Category* | Definition |

|---|---|

| A# | Low-grade fever/mild sore throat/cough/rhinitis/diarrhea |

| B | High-grade fever and/or severe sore throat/cough or Category A plus one or more of the following: |

| Lung/heart/liver/kidney/neurological disease/blood disorders/uncontrolled diabetes/cancer/HIV-AIDS | |

| Patients on long-term steroids | |

| Pregnant woman | |

| Age >60 years | |

| C | Breathlessness, chest pain, drowsiness, fall in blood pressure, hemoptysis, cyanosis (known as red-flag signs) |

| Children with influenza-like illness and red flag signs | |

| Somnolence, inability to feed well, convulsions, high/persistent fever/dyspnea/respiratory distress etc. | |

| Worsening of underlying chronic conditions |

*Categories are re-assessed every 24-48 h, #Laboratory testing is not required for category A cases

Table 5.

Definitions of patients that can be received during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic to the emergency operating room

| Type of case | Definition | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory-confirmed case | A person with laboratory confirmation of COVID-19 infection, irrespective of clinical signs/symptoms | Categorized as A/B/C:such patients have to remain in home isolation for 14 days from the last negative result or 28 days from the date of admission to hospital, whichever is later |

| Suspect case | A patient with acute respiratory illness (fever and at least one sign/symptom of respiratory disease [e.g., cough, shortness of breath, or diarrhea) AND a history of travel to or residence in a country/area or territory reporting local transmission] [as per WHO updated list] of COVID-19 disease during 14 days prior to symptom onset) or A patient/health-care worker with acute respiratory illness AND having been in contact with a confirmed case of COVID-19 case in the last 14 days prior to onset of symptoms or A patient with severe acute respiratory illness (fever and at least one sign/symptom of respiratory disease (e.g., cough, shortness of breath) AND requiring hospitalization AND with no other etiology that fully explains the presentation or A case for whom testing for COVID-19 is inconclusive |

All suspect cases are categorized into Category A/B/C |

| High-risk contacts | Contact with a confirmed case of COVID-19 | All asymptomatic secondary contacts with high risk are instructed to remain under strict home isolation for a period of 28 days. No testing is required |

| Travelers who visited a hospital where COVID-19 cases are being treated | ||

| Travel to a province where COVID-19 local transmission is being reported as per WHO | ||

| Touched body fluids of patients (respiratory tract secretions, blood, vomitus, saliva, urine, or feces) | All symptomatic secondary contacts with high risk should be instructed to remain under strict home isolation for a period of 28 days, if their sample is negative | |

| Had direct physical contact with the body of the patient including physical examination without PPE | ||

| Touched or cleaned the linens, clothes, or dishes of the patient | ||

| Close contact within 3 feet (1 m) of the confirmed case | ||

| Co-passengers of an airplane/vehicle seated in the same row, 3 rows in front and behind of a COVID-19 case | ||

| Low-risk contacts | Shared the same space (same classroom/same room for work or similar activity and not having high-risk exposure the confirmed/suspected case) | All asymptomatic secondary contacts with low risk should beinstructed to avoid nonessential travel and community/social contact for 14 days. No testing is required |

| Travel in the same environment (bus/train) but not having high-risk exposure as cited above | ||

| Any traveler from abroad not satisfying high-risk criteria | ||

| All symptomatic secondary contacts with low risk should be instructed to remain under strict home isolation for a period of 14 days, if their sample is negative |

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019, PPE: Personal protective equipment

Only “lifesaving” or “limb-saving” emergency surgery should be undertaken in COVID-19 cases with active infection. COVID-19 infection is not an indication for emergency caesarean section or pharmacologic induction of labor. The decision to proceed with surgery should be after a joint decision of a “COVID committee” comprising of senior surgeons, anesthesiologists, and head of the institution. Time-sensitive surgery that can be postponed shall be done after the quarantine period of 14 days for cases with mild symptoms and 28 days for cases with severe symptoms, weighing the patient risk versus benefit by the “COVID committee.”

The COVID-19 patient scheduled for emergency surgery should be wheeled directly to the OR and there shall be no waiting in the premedication room. A brief history and clinical and airway examination can be undertaken inside the septic OR so as to facilitate the most minimum contamination. The anesthesia implications of novel pharmacotherapy in COVID-19[53,54,55] is summarized in Table 6. Transportation of patient to OR shall be done only after a telephonic confirmation of “ready” message is passed on from “Septic OR” to the primary care area of the patient. The patient should be transported wearing a triple-layered medical mask or N95/FFP2 mask.[34,50,56] Anti-anxiety doses of benzodiazepines may be administered prior to patient transport. Patients on mechanical ventilation should be transferred with ventilation continued through a Bain's circuit with bacterial and viral filter at the patient end. Use of portable ventilators is not advised in view of their higher aerosol generation property.

Table 6.

Anesthetic implications of novel pharmacotherapy in coronavirus disease 2019 patients

| Drug used | Adverse effects | Drug interactions and anesthetic concerns |

|---|---|---|

| Hydroxychloroquine and chloroquine | Allergic reactions, long QT syndrome, ocular toxicity, neurotoxicity, precipitate porphyrias, aplastic anemia, liver failure | Increases serum digoxin levelsHepatotoxicity induced alteration in metabolism of anesthetic drugsCaution in dyselectrolytemia (hypokalemia) |

| Ritonavir, lopinavir | Nephrolithiasis, diarrhea, inhibition of liver enzymes, elevated triglycerides | Ritonavir both induces and inhibits hepatic enzyme, thus enhancing the effects of fentanyl by reducing the clearance and by increasing the active metabolitesProlonged effects of muscle relaxants have been observedPlasma levels of lignocaine may be increased due to enzyme inhibition |

| Remdesivir | Hepatic dysfunction | Interaction with clarithromycin and rifampicin |

| Tocilizumab | Injection site reactions, hypertension, increased liver enzymes, mouth ulcers, increased serum bilirubin, anaphylaxis | Interaction with statin therapy |

| Oseltamivir | Hyperglycemia, cardiac arrhythmias, hepatitis, seizures, predisposition to hypothermia | Reduced efficacy of diabetes mellitus therapyClopidogrel decreases serum concentrations of oseltamivirProbenecid increases serum oseltamivir levels |

CONDUCT OF ANESTHESIA

Interpersonal communication can be extremely difficult with the PPE donned, hence plan of anesthesia and critical steps need be discussed with the team members. Use of preaccepted sign languages for critical steps is also encouraged.[57] Named PPE gowns make personnel identification easy at this juncture. The surgical procedures that can be conducted under regional/spinal/epidural anesthesia can be conducted under the respective technique as aerosol generation is lesser. However, patient coughing or sneezing in-between the surgery should be prevented as much as possible with adequate sedation. In addition, placing a wet gauze piece in front of the patient's mouth and applying a surgical mask or N95 mask above it can reduce droplet spread. Supplemental oxygen can be delivered with the oxygen mask placed over the surgical/N95 mask.[58,59] Preemptive use of anti-emetic medications can reduce nausea and vomiting, thereby reducing the infective droplets inside OR. Monitoring leads such as electrocardiography, pulse oximetry, noninvasive blood pressure, and capnography should be single use and disposed off after the procedure.[60]

The World Health Organization surgical safety checklist needs be adhered to while conducting any surgical procedure. At present, there are no validated PPE adherence checklists available. In the interest of safety of doctors and paramedics, it is always prudent to follow an institutional PPE adherence and provider safety checklist intra-operatively [Table 7]. Such checklists aid in the surveillance of effectiveness to PPE adherence and shall be a benchmark in enhancing health-care provider safety.

Table 7.

Personal protective equipment adherence and provider safety checklist during the Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic

| Name: Age: Gender: ID no: Date: Diagnosis:- Choose patient type: Laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 case/suspect COVID-19 case/symptomatic high-risk contact/asymptomatic high-risk contact/symptomatic low-risk contact/asymptomatic low-risk contact COVID-19 category (for laboratory-confirmed or suspect case): A/B/C Location of primary isolation area in hospital: Procedure: Describe requirement of emergency surgery: Write all team member’s names: (surgeons, anesthesiologists, scrub nurse, infection control nurse, support staff) | |||

| Safety checklist entries | Concordant | Discordant | Corrective initiative done |

|---|---|---|---|

| Infection control precautions | |||

| All team members have participated in mock drills and COVID-19 training programs | |||

| All team members have adhered to strict hand hygiene | |||

| All team members have introduced each other | |||

| Surgery is undertaken in designated COVID-19 OR only | |||

| Infection control precautions displayed at various areas of the OR | |||

| Negative-pressure isolation system is available in OR else use of split air conditioner discussed among team members | |||

| Essential steps of surgery and plan of anesthesia discussed before donning PPE | |||

| No mobile phones/pagers/tablets/laptop computers inside OR | |||

| All team members have worn Level III PPE | |||

| PPE fit has been tested and found adequate by each team member | |||

| Wearing PPE has been monitored by an infection control nurse | |||

| Security system officers of the hospital informed prior to patient shift-in (at least 30 min prior) | |||

| Ready to shift patient message sent to primary care area of the patient | |||

| Patient received with N95/surgical face mask worn | |||

| Anaesthesia and intubation precautions | |||

| Dedicated anesthesia machine with bacterial and viral filters available | |||

| Disposable equipment used wherever possible | |||

| Rapid sequence induction used for general anesthesia induction | |||

| Video-laryngoscope used for intubation | |||

| In-line closed suction unit used if required | |||

| Patient wears surgical mask or N95 mask throughout if regional anesthesia is chosen | |||

| Backup anesthesiologist available in separate adjacent sterile area with advanced airway carts and resuscitation trolley | |||

| Only minimum number of most essential personnel enter the OR | |||

| Use disposable pens for data entry | |||

| Prophylactic anti-emetics administered and extubation done with minimal aerosol generation | |||

| OR conduct and disinfection precautions | |||

| Surgical specimens/blood samples collected are labeled in double covered containers carrying label “COVID-19” | |||

| Security system officers of the hospital informed prior to patient shift-out (at least 30 min prior) | |||

| Patient is NOT holded in the recovery area after surgery and directly shifted to isolation ICU/HDU | |||

| Each team member has doffed PPE only after patient shift-out | |||

| Doffing of each team member is monitored by an infection control nurse but NOT assisted | |||

| Disposable equipment used are discarded after the procedure | |||

| Adequate disinfection practices adhered to for disinfecting reusable machinery | |||

| CO2 absorbent of anesthesia machine discarded after the case | |||

| Anaesthesia machine has been dedicated for COVID-19 cases during the pandemic and not to be used for any other cases | |||

| Followed bio-containment regulations for waste disposal | |||

| All team members are debriefed after the surgery | |||

| No accidental breach in PPE use by any of the team member | |||

COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019, PPE: Personal protective equipment, ICU/HDU: Intensive care units/high-dependency units, OR: Operating room

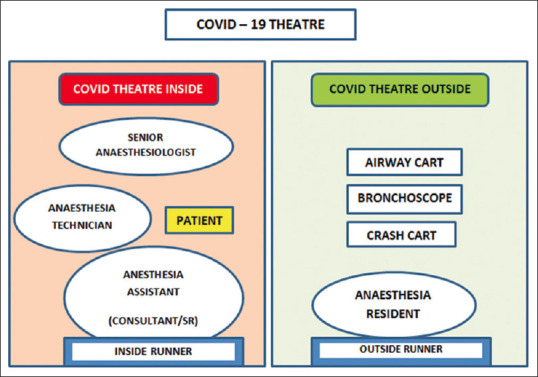

A vast majority of emergency surgical procedures require general anesthesia (GA). The conduct of GA requires mobilization of multiple machinery and airway aids. Unanticipated complications during GA such as difficult intubation/hemodynamic collapse/cardio-pulmonary arrest require multiple airway aids and resuscitation medications. Mobilizing the entire resuscitation machinery and difficult airway cart into the COVID-19 OR can be labor intensive and further decontamination expensive. We suggest that an experienced anesthesiologist with assistant conduct the procedure in COVID-19 OR, and another trainee anesthesiologist be ready donned in a PPE with advanced instrumentation devices and difficult airway cart in a sterile area adjacent to the COVID-19 OR [Figure 2].

Figure 2.

Representational image indicating working arrangement of a COVID-19 operating room. SR: Senior resident trainee doctor

Enhanced preoxygenation with 100% oxygen and a modified rapid sequence induction[61,62] and subsequent intubation is recommended in COVID-19 patients. Cricoid pressure and gentle positive pressure ventilation, in cases with poor pulmonary reserve, prior to intubation are optional depending on case-to-case basis. GA can be induced with 2–3 mg/kg of intravenous (IV) propofol in hemodynamically stable patients. IV etomidate (0.3–0.4 mg/kg) is preferred for GA induction in patients with cardiovascular comorbidities and hemodynamic instability. IV fentanyl 2–3 μg/kg and IV midazolam 0.01–0.05 mg/kg aid in analgesia and suppressing laryngeal reflexes, respectively. In patients with contraindication to succinyl choline, IV rocuronium is preferred, however the availability of IV suggumadex for rocuronium reversal[63] need be ensured in the unforeseen event of a “cannot ventilate” “cannot intubate” situation.

Use of a video-laryngoscope for intubation should be encouraged for COVID-19 cases[64] as anesthesia provider has restricted mobility with the PPE donned, which can convert otherwise simple procedure difficult. Video-laryngoscope also increase the distance between the patient and the anesthesiologist compared to conventional laryngoscopy, thereby offering protection from macro-droplets. Multiple ancillary methods are suggested for reducing macro-aerosol and droplet generation during laryngoscopy. A water-proof transparent plastic sheet that extensively covers from head to toe of the patient is applied, and the video-laryngoscopy is done below this sheet. This can be used only with video-laryngoscopes that have a separate display screen. One other method is to use a transparent aerosol-box to cover patients head during intubation. The efficacies of such techniques are yet to be ascertained, but those are certainly useful to prevent visible macro-droplets from dispersing.

Endo-tracheal intubation must be contemplated after sufficient depth of anesthesia and neuromuscular blockage so as to avoid any patient “coughing” or “bucking.”[65,66] Subsequently endotracheal tube cuff must be inflated prior to initiating positive pressure ventilation. Auscultation to confirm bilateral chest air entry to confirm endo-tracheal tube position is difficult with the PPE worn; hence, capnography can be used for confirmation. Most commercially available endo-tracheal tubes have a black marker line one inch proximal to the cuff, the level of which should be at the level of vocal cords after intubation. With the use of video-laryngoscope, the intubating anesthesiologist and his/her assistant can accurately position the endo-tracheal tube to maintain bilateral chest ventilation, thereby avoiding the need for chest auscultation. The anesthesiologist shall remove the outer gloves in a such a way as to wrap the blade of video-laryngoscope with it after confirming endotracheal tube position, following which a new pair of outer gloves can be worn. Total IV maintenance anesthesia or combined use of inhalational anesthetics is at the discretion of the anesthesiologist though adequate depth of anesthesia should be maintained to prevent patient movement.

Lung protective ventilation strategies[67,68,69,70] with target plateau pressure of <30 cmH2O, high PEEP, and low tidal volumes (6 mL/kg) should be used in patients with COVID-19 pneumonitis. In-line suction systems attached to the patient end of ventilator tubing perform better to prevent aerosol generation inside the OR in such cases.

Point-of-care ultrasound (USG) can be used for procedures such as central venous access or regional anesthesia after covering the USG probe and cables with waterproof endoscopy camera covers. Surface decontamination of the device and USG monitor should be done after the surgical procedure. Point-of-care devices such as USG also can be kept with the backup anesthesiologist [Figure 2] donned in PPE ready in the sterile area who shall enter the “COVID-19 OR” only if necessary.

Extubation of cases done under GA shall be done “deep plane” with anti-aspiration and anti-emetic prophylaxis.[64] Medications such as lignocaine IV and dexmedetomidine IV can also be considered to minimize coughing. A two-layered wet gauze placed over the patients mouth and nose without obstructing either can reduce aerosol generation during extubation. Extubated patients should not be “holded” in the postanesthesia care unit and directly transferred to the isolation high dependency unit (HDU). Patients received on mechanical ventilation can be sent to respective isolation ICU for postoperative mechanical ventilation with necessary precautions to reduce aerosol generation as much as possible. It is to be re-iterated that the anesthesia, surgical, and nursing team, who starts the procedure themselves completes it irrespective of change in duty shift timings, to minimize breach in personal protection during such handovers.

DECONTAMINATION AFTER THE SURGERY

After transfer-out of the patient from the OR, the surgical and anesthesia team shall enter the doffing zone to remove the PPE. Doffing can be monitored at a safe distance by an infection control nurse but not assisted to avoid cross-infection. The ideal doffing sequence for PPE is as follows: shoe covers → gloves → hand hygiene → goggles/face shield → hand hygiene → the gown → hand hygiene → the protective mask → hand hygiene → the head cover → hand hygiene → whole-body shower with oral, nasal, and external auditory canal disinfection and change into personal clothing. Medical waste after a case is to be double-bagged and sent for disposal with labeling “COVID-19.”[71]

Disposable monitoring cables should almost always be used in droplet infection scenarios such as COVID-19. Fomites[72] such as writing pen, case records, and mobile phones that can carry the infective virus should be carefully attended to. It is almost always prudent to avoid personal equipment such as mobile phones/pagers/tablets/laptop computers inside the OR. The HME filter, high-quality bacterial/viral filter, reservoir bag, gas sampling tubing, water trap for gas sampling tubing, and the breathing circuits should be discarded after single use.[73]

There are no data testing the efficacy of breathing circuit filters for preventing transmission of SARS COV-2 to the anesthesia machine. A VFE of 99.99% means that only one particle in 10,000 will pass through the filter under standard test conditions that control flow rate (30 L/minute is a commonly used flow for adult condition testing. Increased flow rate reduces the VFE). The best available evidence at present show that the high-quality viral filter prevents the 2019-nCoV from contaminating the anesthesia machine.[74] Moreover, combining the viral filter and HME filter enhances the filtration efficacy. However, during pandemics such as now, it is always advisable that there is a dedicated anesthesia machine for COVID-19 patients.

Manufacturers imply that gas sampled from the machine side of an HME filter is not contaminated. None of the manufacturers at present recommend cleaning procedures that involve the internal components of the anesthesia machine as long as high-quality filters are used with each patient to prevent exhaled 2019-nCoV virus from entering the machine and gas sampling lines are connected to the machine side of the filter. Cleaning internal components of the anesthesia machine is required only if HME, and viral filters were not used during the procedure. Such opening and cleaning of the anesthesia machines are labor intensive, time consuming, and should be done by the manufacturer only.

Reusable equipment, surface of anesthesia machine, video-laryngoscope handles, and floors/walls of the OR should be washed with soap and water followed by surface disinfection with 2%–3% hydrogen peroxide/2–5 g/l chlorine disinfectant/more than 70% alcohol wiping/double concentration sodium hypochlorite (0.1%).[72] Single-concentration sodium hypochlorite and chlorhexidine solutions are infective in inactivation the virus. Respiratory circuit and bacterial/viral filters of the anesthesia machine are to be discarded after single use. The CO2 absorbent should be replaced after each case. The advanced airway aids, difficult airway cart, and resuscitation cart kept ready in the sterile area with the backup anesthesiologist, if unused need not be subject to disinfection had there had not been any contamination.

POSTEXPOSURE PROPHYLAXIS TO OR PROFESSIONAL

The surgical team should work together to obtain a concordant entry in all points of the PPE adherence and provider safety checklist used [Table 7]. The signed checklist needs to be retained in hospital records, and an electronic version of the completed checklist should be sent by electronic mail to the hospital infection control facility and COVID-19 committee. Any discordant entry shall be reviewed and will be reassessed to whether to be treated as a breach in personal safety. Incident tracing for accidental lapses in PPE use can be easily facilitated with the PPE Adherence and Provider Safety Checklist. The surgical team member should be psychologically supported and directed in person to the fever clinic for health-care persons of the hospital in case the “COVID-19 committee” deems it to be necessary on retrospective review. The health-care professional shall be provided accommodation in the quarantine facility for staff of the hospital or kept on home isolation. The health-care professional shall be tested for nCoV-19 using throat swab with reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction on day 5 and day 14 or early if symptomatic.

The present practice advisory by the National Task Force for COVID-19 of the Indian Council of Medical Research advises a postexposure prophylaxis with tablet hydroxychloroquine 400 mg (HCQ) twice a day on day 1 followed by 400 mg once weekly for next 7 weeks.[50] The drug is contraindicated in persons with retinopathy and allergy to 4-aminoquinone compounds. However, evidence of efficacy of this medication in prophylaxis is still in its infancy,[75,76,77] and such intake shall not instill a false sense of security against the disease. Besides this, the health-care worker shall be given an opportunity to participate in the randomized controlled trial on the role of HCQ in postexposure prophylaxis on an informed consent basis. Antiviral drugs such as remdesivir, lopinavir, ritonavir, oseltamivir, and tocilizumab are used for only for the treatment of COVID-19 cases[78,79,80,81,82,83] and not indicated for postexposure prophylaxis.

CONCLUSION

The COVID-19 as a pandemic emerged as a global threat all too suddenly that governments world over have found it unmanageable or difficult to contain. Disease severity shows variation depending on demographic characteristics such as age; history of chronic illnesses such as cardiovascular/renal/respiratory disease; pregnancy; immune-suppression; angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor medication use;[84] and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use, but the pattern of disease spread is uniform – contact, droplets, and fomites. Absence of an effective treatment or vaccine[85] is a major setback to contain the disease. As such, social distancing and hand hygiene are the norms to prevent transmission. Isolation of affected or suspected cases is the prevailing means of controlling spread. Considering that a case of COVID-19 can anytime require emergency surgery for lifesaving reasons and such a requirement is directly proportional to the number of cases in the community, it is imperative to design, develop, and adhere to precautionary outlines suggested here to keep the anesthetic and para-medical support staff away from chances of getting infected by this deadly virus.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Xu J, Xu J. Responses to emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases: One world, One health. Front Med. 2018;12:1–2. doi: 10.1007/s11684-018-0619-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu IT, Li Y, Wong TW, Tam W, Chan AT, Lee JH, et al. Evidence of airborne transmission of the severe acute respiratory syndrome virus. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1731–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scales DC, Green K, Chan AK, Poutanen SM, Foster D, Nowak K, et al. Illness in intensive care staff after brief exposure to severe acute respiratory syndrome. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1205–10. doi: 10.3201/eid0910.030525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muller MP, McGeer A. Febrile respiratory illness in the intensive care unit setting: An infection control perspective. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2006;12:37–42. doi: 10.1097/01.ccx.0000198056.58083.a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fowler RA, Lapinsky SE, Hallett D, Detsky AS, Sibbald WJ, Slutsky AS, et al. Critically ill patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. JAMA. 2003;290:367–73. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.3.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christian MD, Loutfy M, McDonald LC, Martinez KF, Ofner M, Wong T, et al. Possible SARS coronavirus transmission during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:287–93. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Riel D, Munster VJ, de Wit E, Rimmelzwaan GF, Fouchier RA, Osterhaus AD, et al. Human and avian influenza viruses target different cells in the lower respiratory tract of humans and other mammals. Am J Pathol. 2007;171:1215–23. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piedimonte G, Perez MK. Respiratory syncytial virus infection and bronchiolitis. Pediatr Rev. 2014;35:519–30. doi: 10.1542/pir.35-12-519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avšič-Županc T, Saksida A, Korva M. Hantavirus infections. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2019;21S:e6–16. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: A descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:727–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: Summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, Wang X, Zhou L, Tong Y, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, ofnovel Coronavirus infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1199–207. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christian MD, Poutanen SM, Loutfy MR, Muller MP, Low DE. Severe acute respiratory syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1420–7. doi: 10.1086/420743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Majumder MS, Rivers C, Lofgren E, Fisman D. Estimation of MERS-coronavirus reproductive number and case fatality rate for the Spring 2014 Saudi Arabia outbreak: Insights from publicly available data. PLoS Curr. 2014;6 doi: 10.1371/currents.outbreaks.98d2f8f3382d84f390736cd5f5fe133c. ecurrents.outbreaks.98d2f8f3382d84f390736cd5f5fe133c. doi:10.1371/currents.outbreaks.98d2f8f3382d84f390736cd5f5fe133c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Situation Reports. 2020. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/situation-reports .

- 18.Zhao S, Lin Q, Ran J, Musa SS, Yang G, Wang W, et al. Preliminary estimation of the basic reproduction number of novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in China, from 2019 to 2020: A data-driven analysis in the early phase of the outbreak. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;92:214–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.01.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.The Novel Coronavirus Pneumonia Emergency Response Epidemiology Team: The epidemiological characteristics of an outbreak of 2019 novel Coronavirus diseases (COVID-19) – China, 2020. China CDC Wkly. 2020;2:113–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bogoch II, Watts A, Thomas-Bachli A, Huber C, Kraemer MUG, Khan K. Potential for global spread of a novel coronavirus from China? J Travel Med. 2020;27:taaa011. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa011. doi:10.1093/jtm/taaa011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prompetchara E, Ketloy C, Palaga T. Immune responses in COVID-19 and potential vaccines: Lessons learned from SARS and MERS epidemic. Asian Pac J Allergy Immunol. 2020;38:1–9. doi: 10.12932/AP-200220-0772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.The New York Times. [Last accessed on 2015 May 14]. Available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/24/world/asia/india-coronavirus-lockdown.html. ()

- 23.Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH, To KK, Chu H, Yang J, et al. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: A study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–23. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brest M. Wuhan Doctor Treating Coronavirus Patients Dies after Contracting Disease. Washington Examiner. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 30]. URL: Available from: https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/news/wuhan-doctor-treatingcoronavirus-patients-dies-after-contracting-disease .

- 25.Buckley C. Chinese Doctor, Silenced After Warning of Outbreak, Dies from Coronavirus. The New York Times. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 30]. URL: available from: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/02/06/world/asia/chinesedoctor-Li-Wenliang-coronavirus.html .

- 26.Tran K, Cimon K, Severn M, Pessoa-Silva CL, Conly J. Aerosol generating procedures and risk of transmission of acute respiratory infections to healthcare workers: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Caputo KM, Byrick R, Chapman MG, Orser BJ, Orser BA. Intubation of SARS patients: Infection and perspectives of healthcare workers. Can J Anaesth. 2006;53:122–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03021815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fowler RA, Scales DC, Ilan R. Evidence of airborne transmission of SARS. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:609–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen X, Liu Y, Gong Y, Guo X, Zuo M, Li J, et al. Perioperative management of patients infected with the novel coronavirus: Recommendation from the joint task force of the Chinese society of anesthesiology and the Chinese association of anesthesiologists. Anesthesiology. 2020;132:1307–16. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000003301. doi:10.1097/ALN.0000000000003301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cook TM, El-Boghdadly K, McGuire B, McNarry AF, Patel A, Higgs A. Consensus guidelines for managing the airway in patients with COVID-19: Guidelines from the Difficult Airway Society, the Association of Anaesthetists the Intensive Care Society, the Faculty of Intensive Care Medicine and the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:785–99. doi: 10.1111/anae.15054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shanthanna H, Strand NH, Provenzano DA, Lobo CA, Eldabe S, Bhatia A, et al. Caring for patients with pain during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consensus recommendations from an international expert panel. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:935–44. doi: 10.1111/anae.15076. doi:10.1111/anae.15076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Suresh V. The 2019 novel corona virus outbreak - An institutional guideline. Indian J Anaesth. 2020;64:242–3. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_104_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tien HC, Chughtai T, Jogeklar A, Cooper AB, Brenneman F. Elective and emergency surgery in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) Can J Surg. 2005;48:71–4. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Health Mission Kerala. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: http://www.arogyakeralam.gov.in/index.php/corona/corona-guidelines .

- 35.Zamora JE, Murdoch J, Simchison B, Day AG. Contamination: A comparison of 2 personal protective systems. CMAJ. 2006;175:249–54. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zuo MZ, Huang YG, Ma WH, Xue ZG, Zhang JQ, Gong YH, et al. Expert recommendations for tracheal intubation in critically ill patients with novel coronavirus disease 2019. Chin Med Sci J. 2020 doi: 10.24920/003724. 10.24920/003724. doi:10.24920/003724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chughtai AA, Seale H, Rawlinson WD, Kunasekaran M, Macintyre CR. Selection and Use of Respiratory Protection by Healthcare Workers to Protect from Infectious Diseases in Hospital Settings. Ann Work Expo Health. 2020;64:368–77. doi: 10.1093/annweh/wxaa020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen X, Shang Y, Yao S, Liu R, Liu H. Perioperative care provider”s considerations in managing patients with COVID-19 infections. Transl Perioper Pain Med. 2020;7:216–24. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheng ZJ, Shan J. 2019 Novel coronavirus: Where we are and what we know. Infection. 2020;48:155–63. doi: 10.1007/s15010-020-01401-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carinci F. Covid-19: Preparedness, decentralisation, and the hunt for patient zero. BMJ. 2020;368 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m799. bmj.m799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Agarwal A, Nagi N, Chatterjee P, Sarkar S, Mourya D, Sahay RR, et al. Guidance for building a dedicated health facility to contain the spread of the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak. Indian J Med Res. 2020;151:177–83. doi: 10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_518_20. doi:10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_518_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alavi-Moghaddam M. A novel coronavirus outbreak from Wuhan City in China, Rapid need for emergency departments preparedness and response; a Letter to Editor. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2020;8:e12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li Y, Huang X, Yu IT, Wong TW, Qian H. Role of air distribution in SARS transmission during the largest nosocomial outbreak in Hong Kong. Indoor Air. 2005;15:83–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0668.2004.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Loutfy MR, Wallington T, Rutledge T, Mederski B, Rose K, Kwolek S, et al. Hospital preparedness and SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:771–6. doi: 10.3201/eid1005.030717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilkes AR. Measuring the filtration performance of breathing system filters using sodium chloride particles. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:162–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2044.2002.02328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilkes AR. Heat and moisture exchangers and breathing system filters: Their use in anaesthesia and intensive care. Part 1 - History, principles and efficiency. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:31–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06563.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilkes AR. Heat and moisture exchangers and breathing system filters: Their use in anaesthesia and intensive care. Part 2 - practical use, including problems, and their use with paediatric patients. Anaesthesia. 2011;66:40–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.2010.06564.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sprung CL, Zimmerman JL, Christian MD, Joynt GM, Hick JL, Taylor B, et al. Recommendations for intensive care unit and hospital preparations for an influenza epidemic or mass disaster: Summary report of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine's Task Force for intensive care unit triage during an influenza epidemic or mass disaster. Intensive Care Med. 2010;36:428–43. doi: 10.1007/s00134-010-1759-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heuer JF, Crozier TA, Howard G, Quintel M. Can breathing circuit filters help prevent the spread of influenza A (H1N1) virus from intubated patients? GMS Hyg Infect Control. 2013;8:Doc09. doi: 10.3205/dgkh000209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Indian Council for Medical Research. New Delhi: [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: https://icmr.nic.in/content/covid-19 . [Google Scholar]

- 51.To KK, Tsang OT, Leung WS, Tam AR, Wu TC, Lung DC, et al. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARSCoV-2: An observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020:pii: S1473-3099(20)30196-1. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30196-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zou L, Ruan F, Huang M, Liang L, Huang H, Hong Z, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Viral Load in Upper Respiratory Specimens of Infected Patients. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1177–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2001737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dong L, Hu S, Gao J. Discovering drugs to treat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Drug Discov Ther. 2020;14:58–60. doi: 10.5582/ddt.2020.01012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoffman RM, Currier JS. Management of antiretroviral treatment-related complications. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2007;21:103–32, ix. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2007.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmitt C, Kuhn B, Zhang X, Kivitz AJ, Grange S. Disease-drug-drug interaction involving tocilizumab and simvastatin in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2011;89:735–40. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2011.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jin YH, Cai L, Cheng ZS, Cheng H, Deng T, Fan YP, et al. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version) Mil Med Res. 2020;7:4. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Myatra SN, Patwa A, Divatia JV. Critical language during an airway emergency: Time to rethink terminology? Indian J Anaesth. 2020;64:275–9. doi: 10.4103/ija.IJA_214_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leung CC, Joynt GM, Gomersall CD, Wong WT, Lee A, Ling L, et al. Comparison of highflow nasal cannula versus oxygen face mask for environmental bacterial contamination in critically ill pneumonia patients: A randomized controlled crossover trial. J Hosp Infect. 2019;101:84–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheung TM, Yam LY, So LK, Lau AC, Poon E, Kong BM, et al. Effectiveness of noninvasive positive pressure ventilation in the treatment of acute respiratory failure in severe acute respiratory syndrome. Chest. 2004;126:845–50. doi: 10.1378/chest.126.3.845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Peng PW, Wong DT, Bevan D, Gardam M. Infection control and anesthesia: Lessons learned from the Toronto SARS outbreak. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50:989–97. doi: 10.1007/BF03018361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kamming D, Gardam M, Chung F. Anaesthesia and SARS. Br J Anaesth. 2003;90:715–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeg173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nicolle L. SARS safety and science. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50:983. doi: 10.1007/BF03018360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Keating GM. Sugammadex: A review of neuromuscular blockade reversal. Drugs. 2016;76:1041–52. doi: 10.1007/s40265-016-0604-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wax RS, Christian MD. Practical recommendations for critical care and anesthesiology teams caring for novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) patients. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:568–76. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01591-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Raboud J, Shigayeva A, McGeer A, Bontovics E, Chapman M, Gravel D, et al. Risk factors for SARS transmission from patients requiring intubation: A multicentre investigation in Toronto, Canada. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10717. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cheung JC, Ho LT, Cheng JV, Cham EY, Lam KN. Staff safety during emergency airway management for COVID-19 in Hong Kong. Lancet Respir Med. 2020:pii: S2213-2600(20)30084-9. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30084-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Fan E, Del Sorbo L, Goligher EC, Hodgson CL, Munshi L, Walkey AJ, et al. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine/Society of critical care medicine clinical practice guideline: Mechanical ventilation in adult patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195:1253–63. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0548ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Griffiths MJ, McAuley DF, Perkins GD, Barrett N, Blackwood B, Boyle A, et al. Guidelines on the management of acute respiratory distress syndrome. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2019;6:e000420. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2019-000420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Griffiths M, Fan E, Baudouin SV. New UK guidelines for the management of adult patients with ARDS. Thorax. 2019;74:931–3. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Matthay MA, Zemans RL, Zimmerman GA, Arabi YM, Beitler JR, Mercat A, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5:18. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yu H, Sun X, Solvang WD, Zhao X. Reverse logistics network design for effective management of medical waste in epidemic outbreaks: Insights from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in Wuhan (China) Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:1770. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17051770. doi:10.3390/ijerph17051770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kampf G, Todt D, Pfaender S, Steinmann E. Persistence of coronaviruses on inanimate surfaces and their inactivation with biocidal agents. J Hosp Infect. 2020;104:246–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2020.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ti LK, Ang LS, Foong TW, Ng BS. What we do when a COVID-19 patient needs an operation: Operating room preparation and guidance. Can J Anaesth. 2020;67:756–8. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01617-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Drager Medical. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www.draeger.com/en_in/Hospital/Products/Accessories-and-Consumables/Ventilation-Accessories/Breathing-System-Filters-and-ME/Filter-and-Heat-and-moisture-exchanger .

- 75.Guastalegname M, Vallone A. Could chloroquine/hydroxychloroquine be harmful in Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2020:pii: Ciaa321. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhou D, Dai SM, Tong Q. COVID-19: A recommendation to examine the effect of hydroxychloroquine in preventing infection and progression. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2020:pii: Dkaa114. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkaa114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sahraei Z, Shabani M, Shokouhi S, Saffaei A. Aminoquinolines against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): Chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine? Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105945. 55105945.doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, Yang X, Liu J, Xu M, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020;30:269–71. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-0282-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Vincent MJ, Bergeron E, Benjannet S, Erickson BR, Rollin PE, Ksiazek TG, et al. Chloroquine is a potent inhibitor of SARS coronavirus infection and spread. Virol J. 2005;2:69. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-2-69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chu CM, Cheng VC, Hung IF, Wong MM, Chan KH, Chan KS, et al. Group HUSS: Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: Initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax. 2004;59:252–6. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lim J, Jeon S, Shin HY, Kim MJ, Seong YM, Lee WJ, et al. Case of the index patient who caused tertiary transmission of COVID-19 infection in Korea: The application of lopinavir/ritonavir for the treatment of COVID-19 Infected pneumonia monitored by quantitative RT-PCR. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35:e79. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lu H. Drug treatment options for the 2019-new coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Biosci Trends. 2020;14:69–71. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01020. doi:10.5582/bst.2020.01020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lewis SR, Pritchard MW, Thomas CM, Smith AF. Pharmacological agents for adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;7:CD004477. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004477.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fang L, Karakiulakis G, Roth M. Are patients with hypertension and diabetes mellitus at increased risk for COVID-19 infection? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8:e21. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30116-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Myint A, Jones T. Possible method for the production of a COVID-19 vaccine. Vet Rec. 2020;186:388. doi: 10.1136/vr.m1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]