Abstract

The CACNA1A gene encodes the pore-forming α1A subunit of the voltage-gated CaV2.1 Ca2+ channel, essential in neurotransmission, especially in Purkinje cells. Mutations in CACNA1A result in great clinical heterogeneity with progressive symptoms, paroxysmal events or both. During infancy, clinical and neuroimaging findings may be unspecific, and no dysmorphic features have been reported. We present the clinical, radiological and evolutionary features of three patients with congenital ataxia, one of them carrying a new variant. We report the structural localization of variants and their expected functional consequences. There was an improvement in cerebellar syndrome over time despite a cerebellar atrophy progression, inconsistent response to acetazolamide and positive response to methylphenidate. The patients shared distinctive facial gestalt: oval face, prominent forehead, hypertelorism, downslanting palpebral fissures and narrow nasal bridge. The two α1A affected residues are fully conserved throughout evolution and among the whole human CaV channel family. They contribute to the channel pore and the voltage sensor segment. According to structural data analysis and available functional characterization, they are expected to exert gain- (F1394L) and loss-of-function (R1664Q/R1669Q) effect, respectively. Among the CACNA1A-related phenotypes, our results suggest that non-progressive congenital ataxia is associated with developmental delay and dysmorphic features, constituting a recognizable syndromic neurodevelopmental disorder.

Keywords: ataxia, cerebellar atrophy, dysmorphic traits, early-onset cerebellar ataxia, CACNA1A gene, CaV2.1 (P/Q-type) voltage-dependent calcium channel

1. Introduction

The CACNA1A gene, located on chromosome 19p13, encodes the pore-forming α1A subunit of the voltage-gated CaV2.1 (P/Q-type) Ca2+ channel, which mediates the intracellular entry of Ca2+ ions [1]. CACNA1A plays a major role in neurotransmitter release throughout the nervous system, especially in cerebellar Purkinje cells and in all brain areas involved in the pathogenesis of migraine [1].

The CaV2.1 (P/Q-type) Ca2+ channel is a high-voltage-activated channel consisting of a principal pore-forming subunit (α1A or CACNA1A), associated with auxiliary subunits [2,3]. α1A consists of four repeated homologous domains (DI–DIV), each with six transmembrane regions (S1-S6) that constitute two functional modules: a voltage sensor (S1-S4) and a Ca2+-selective pore (S5-P loop-S6) [2]. The movement of 5–6 positively charged residues located at the S4 helices (Arg+ or Lys+, every 3rd-4th amino acid (defined as R0-R5 gating charges)) induces the conformational changes required for pore opening in response to membrane depolarization [2].

Mutations in the CACNA1A gene result in great clinical heterogeneity, and present with chronic progressive symptoms or paroxysmal events (including sporadic and familial hemiplegic migraine (HM), epilepsy and migraine), or both [4]. Initially, mutations in the CACNA1A gene were identified in patients with familial hemiplegic migraine (FHM) (MIM#141500) or episodic ataxia type 2 (MIM#108500) [4], in that phenotypes acetazolamide may prevent recurrence and improve symptoms [5]. Triplet repeat mutations in the CACNA1A gene were associated with late onset-spinocerebellar ataxia type 6 (MIM#183086) characterized by late onset, slowly progressive cerebellar ataxia, due to toxic accumulation of an expanded polyQ [6]. Other mutations of CACNA1A were identified in patients with early onset epileptic encephalopathy (MIM#617106) [7]. Recently, single case reports and short case series have described patients with congenital (non-episodic) ataxia, with or without cerebellar atrophy, carrying missense CACNA1A mutations [8,9], located around pore regions, voltage-sensing regions and S4-S5 linkers connecting these two functional modules of CaV2.1 [8]. Therefore, CACNA1A mutations should be included in the differential diagnosis of both congenital ataxia and early onset epileptic encephalopathy [7,8]. Unfortunately, clinical findings may be unspecific at early stages, radiology may show normal findings and dysmorphic features that could be of help have not yet been reported. To complete the phenotype, cognitive dysfunction, including learning difficulties and autism, have been reported among the chronic neurological manifestations associated with CACNA1A point-mutations [4,10,11].

We present the neurological and radiological features of three patients with congenital ataxia, two of them with a previously reported CACNA1A mutation and one carrying a new CACNA1A variant. We propose a pattern of dysmorphic facial features to facilitate diagnosis. Clinical and neuroradiological evolution, pharmacological management, structural localization of variants and their expected functional consequences are also depicted.

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Description Of Patients

Patients’ molecular, clinical and radiological data are presented in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

GA: Gestational age; HELLP syndrome: hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, low platelet count, related with pregnancy; SD: standard deviation; OFC: occipito-frontal circumference; WIPPSI: Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence; ADHD: attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder; MPD: Methyphenidate; MVRD: Midsaggital vermis relative diameter. * Subscores: Language 77, socialization 80, coordination 75, postural 34.

| Patient/Gender | 1 Female | 2 Male | 3 Female |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 8 years | 20 years | 7 years |

| Molecular findings/ inheritance |

c.4182C>A p.Phe1394Leu/De novo |

c.4991G>A p.Arg1664Gln/De novo |

c.5006G>A p.Arg1669Gln/De novo |

| Pregnancy & delivery/GA | Twin pregnancy/HELLP syndrome/C-section/ 35 weeks | Normal/eutocic/41 weeks | Normal pregnancy/forceps/40 + 6 weeks |

| Somatometry at birth (SD) | Weight 2150 g (+1.0SD) Height 43.5cm (+0.7 SD) OFC 32 cm (+0.5 SD) |

Weight 3520 g (+0,1 SD) Height 51 cm (+0.1 SD) OFC 36 cm (+0.4 SD) |

Weight 3400 g (+0.3 SD) Height 51 cm (+0.6 SD) OFC 35 cm (+0.1 SD) |

| Somatometry at last evaluation (SD) | 19.5 kg (−1.5 SD) 1.16 m (−0.5 SD) OFC 52.5 cm (+0.5 SD) |

77.2 kg (+0.2 SD) 176 m (−0.2 SD) OFC 59 cm (+1.5 SD) |

22.6 kg (−0.89 9 SD) 1.23 m (−0.69 7 SD) OFC 53.5 cm (+1.2 SD) |

| Initial neurological symptoms | Hypotonia Severe developmental delay |

Hypotonia Developmental delay |

Hypotonia Development delay |

| Cerebellar syndrome | Truncal ataxia and stereotypes Strabismus, terminal nystagmus | Mild ataxia/Dysarthria Oculomotor apraxia Nystagmus |

Mild ataxia |

| Neurodevelopment | Sitting position: 27 months Walk only with stroller: 5 years No speech (guttural sounds) Special schooling |

Sitting position: 8 months Independent walking: 30 months Language delay Occupational school |

Sitting position: 9 months Independent walking: 30 months Language Delay Ordinary school with support |

| Other neurological symptoms | Intellectual disability Autistic traits Attention deficit (treated with guanfacine) |

Mild intellectual disability Uncontrolled lateral head movements without consciousness abnormalities. | Mild intellectual disability Brunet−Lézine (30 months) 67 * WIPPSI IV (5.5 years): verbal IQ 70, performance IQ 68. ADHD (MPD) |

| Cranial magnetic resonance | 6 months: ventricular enlargement and increased extra−axial spaces. Normal posterior fossa structures. 16 months: cerebellar atrophy: increased interfolia spaces mainly in vermis. MVRD = 0.66 (mean for controls 0.77). 4 years 10 months: progression of generalized cerebellar atrophy. MVRD = 0.51 (mean for controls 0.80) |

6 years 10 months: cerebellar atrophy, with a MVRD = 0.76 (mean for controls 0. 82). 13 years 2 months: progressive generalized cerebellar atrophy. MVRD = 0.64 (mean for controls 0.87) |

15 months: no signs of cerebellar atrophy. 24 months: cerebellar atrophy: increase of interfolia spaces in the superior vermis |

| ICARS assessment | No collaboration, no comprehension | 17 years: 14/100 19 years: 12/100 |

4 years: 28/100 6 years: 19/100 |

| Acetazolamide therapy(at least during 8 months) | 12 mg/kg/day in two doses Improvement in muscle tone and communication intention. No objective positive response in the long term. |

250 mg /12 h Improvement in motor symptoms. Abolished stereotyped episodes. Withdrawn due to lithiasis |

12 mg/kg/day in two doses. No objective positive response |

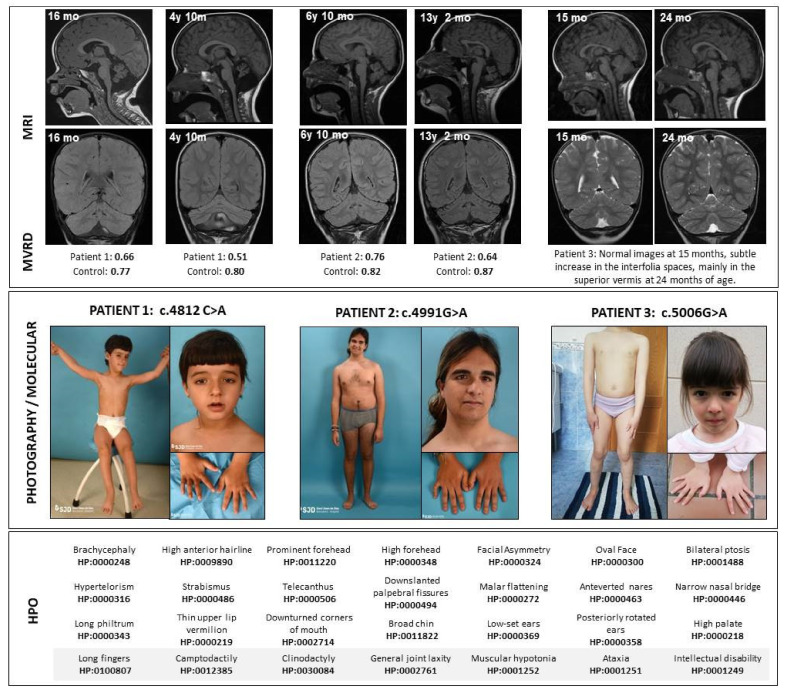

Figure 1.

Clinical and radiological features of patients. Above, the magnetic resonance sagittal and coronal images show a progression in the cerebellar atrophy in Patients 1 and 2, despite clinical stabilization. Immediately below the images, the midsagittal vermis relative diameter (MVRD) has been calculated in the sagittal sequences for patients 1 and 2. MVRDs are detailed and compared to controls’ values. In the middle, pictures from the patients are shown. In the bottom, Human Phenotype Ontology (HPO) codes are included. y: years; mo: months; MVRD: midsagittal vermis relative diameter.

Pregnancies were uneventful; all the patients showed developmental delay, with particularly marked speech delay in Patient 1. They all presented persistent cerebellar symptoms in different degrees of severity: global hypotonia, truncal and limb ataxia, dysarthria or slurred speech and oculomotor symptoms such as nystagmus, oculomotor apraxia and strabismus. Patients 2 and 3 walk independently and are able to maintain a conversation at 20 years and 7 years of age, respectively. Patient 1, the most severely affected, is able to walk only with a walking frame and has severe communication impairment at 8 years of age. They have not shown neurological regression at any time.

Acetazolamide was initiated in all three patients, applying a compassionate use formula, and maintained for at least 8 months. Responses are detailed in Table 1. In the case of Patient 2, at the age of 17 years he came into the emergency room because of subtle uncontrolled lateral head movements without consciousness abnormalities. A video EEG register during the episode ruled out epileptic activity, and the initiation of acetazolamide limited the episodes and improved the motor symptoms (three points in the ICARS). However, after 12 months of therapy he presented kidney lithiasis and the treatment was stopped. Subtle worsening in motor abilities was evident but no new abnormal movements appeared after the withdrawal.

The two younger patients showed abnormal executive functions and fulfilled attention deficit with hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), with positive response to guanfacine and methylphenidate, respectively.

The three patients show common dysmorphic traits (Figure 1) such as a mildly asymmetric and oval face with large and prominent forehead, mild bilateral ptosis, strabismus, hypertelorism, telecanthus, downslanting palpebral fissures and narrow nasal bridge. Patients 1 and 2 also show low-set ears. In the midface, patients 1 and 3 show a long philtrum and a high palate. They all present joint laxity, but also long fingers, with clinodactyly of fifth fingers combined with marked camptodactyly of fifth fingers in the oldest patient.

Concerning neuroimaging, cranial MRI characteristics are detailed in Table 1, and images are included in Figure 1. In sequential MRI studies a progression in the cerebellar atrophy is marked, with unspecific or no findings in the supratentorial structures. Their MVRD was compared with two sex- and age-matched controls.

2.2. Molecular Characterization of Patients

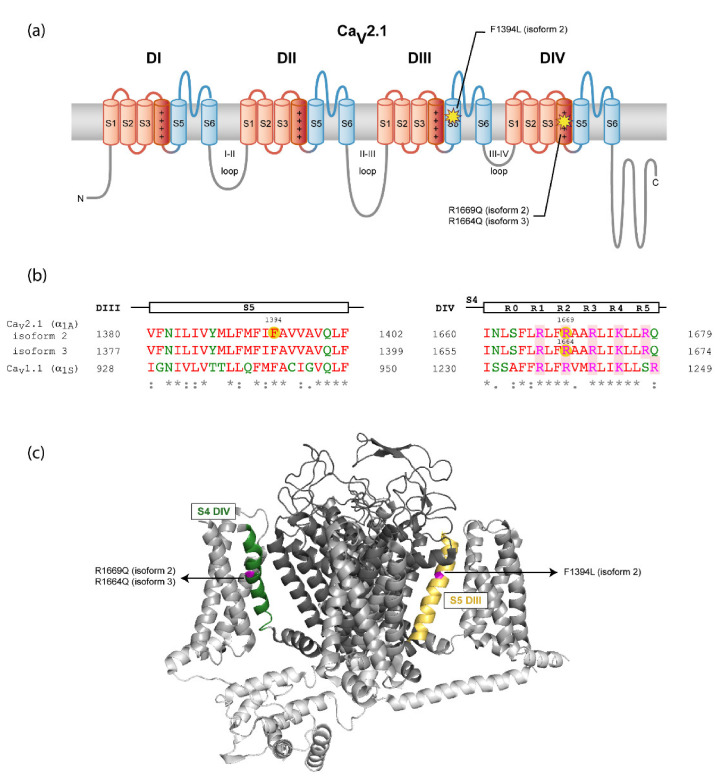

Regarding molecular findings, patient 1 had a likely pathogenic heterozygous missense mutation c.4182C>A (p.Phe1394Leu, F1394L) in the CACNA1A gene encoding α1A isoform 2, NM_023035.2. Patient 2 and 3 had a similar likely pathogenic heterozygous missense mutation with different nomenclature due to isolation from two different CACNA1A genes encoding α1A isoforms: c.4991G>A (p.Arg1664Gln, R1664Q) in the isoform 3 (NM_001127221.1) and c.5006G>A (p.Arg1669Gln, R1669Q) in the isoform 2 (NM_023035.2), respectively (Figure 2b and Figure 3, right).

Figure 2.

Location of the mutations in CaV2.1 α1A channel subunit. (a) Location of the variant residues of α1A channel subunit isoforms 2 and 3 in the secondary structure of the protein according to the cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) structure of the rabbit CaV1.1 complex, containing the pore-forming α1S and several regulatory subunits [12] (see also panel B). N- and C-termini and the intracellular loops are shown in gray, voltage-sensor modules (S1–S4) from the four domains are in red—with the S4 α-helixes colored in dark red—and Ca2+-selective pore modules (S5-P loop-S6) are in blue. (b) Sequence alignment of the regions affected by variants between the human α1A subunit isoforms 2 and 3 and rabbit CaV1.1 α1S subunit. The α1A subunit segment of each alignment is indicated at the top. Mutations are highlighted with yellow circles on the human CaV2.1 (hCaV2.1) sequences. The gating charged residues of S4 segments (labeled R0-R5) are shaded in red. Amino acids are colored depending on their physicochemical properties: small and hydrophobic are in red, acidic in blue, basic in magenta and G and amino acids containing hydroxyl, sulfhydryl or amine groups in green. Below, a consensus code indicates fully conserved residues (*), conservation between residues with strongly similar properties (:) or with weakly similar properties (.). The Uniport IDs of the sequences aligned are for hCaV2 (α1A): O00555-2 (isoform 2) and O00555-3 (isoform 3) and for rabbit CaV1.1 (α1S): P07293. The sequence alignments were made using Multiple Sequence Aligment Clustal Omega. (c) Three-dimensional location of the amino acid variants on a CaV channel model. The structure of the α1S subunit of the CaV1.1 channel (PDB 5GJV) [12] was used as a model considering their high level of homology (panel B). N- and C-termini and the intracellular loops are shown in light gray, voltage-sensor modules (S1–S4) are in gray and Ca2+-selective pore modules (S5-P loop-S6) are in dark gray. The two regions where mutations are located are highlighted in yellow for S5 helix of DIII and green for S4 helix of DIV. The residues of CaV1.1 (α1S) equivalent to those mutated in CaV2.1 (α1A) and identified in the patients, according to the sequence alignment on panel B, have been highlighted in magenta.

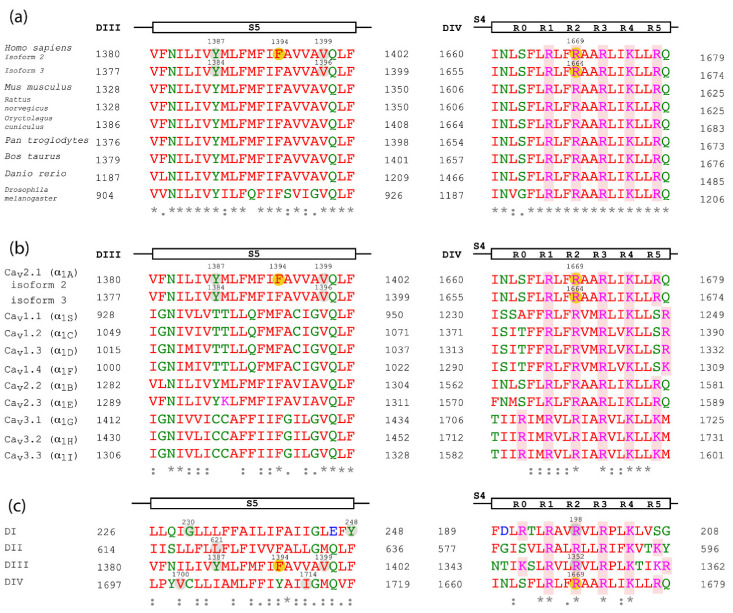

Figure 3.

Sequence alignment of the α1A subunit regions affected by the amino acid variants. Sequence alignment of the α1A subunit regions affected by mutations, including α1A isoforms 2 and 3, between different species (a), between the human CaV channel family (b) and between the four domains of α1A subunit isoform 2 (c). The α1A region of each alignment is indicated at the top. CaV2.1 mutations are highlighted with yellow circles on the α1A subunit isoform 2 or 3. Other CaV2.1 residues affected by mutations mentioned in the text are indicated in gray circles. The gating charged amino acids of S4 segments (labeled R0-R5) and shaded in red. Residues are colored given their physicochemical properties: small and hydrophobic are in red, acidic in blue, basic in magenta and G and residues containing hydroxyl, sulfhydryl or amine groups in green. The consensus code below indicates fully conserved residues (*), conservative (:) or semi-conservative amino acid substitutions (.). The Uniport IDs of the aligned orthologous CaV2.1 sequences are: Mus musculus: P97445; Rattus norvegicus: P54282; Oryctolagus cuniculus: P27884; Pan troglodytes: A0A2I3T217; Bos taurus: F1N1E0; Danio rerio: E9QJF6; Drosophila melanogaster: P91645. The IDs of the human CaV channel family aligned are the following hCav1.1: Q13698; hCaV1.2: Q13936; hCaV1.3: Q01668; hCaV1.4: O60840; hCaV2.2: Q00975; hCaV2.3: Q15878; hCaV3.1: O43497; hCaV3.2: O95180; hCaV3.3: Q9P0X4. The sequence alignments were made using Multiple Sequence Aligment Clustal Omega. Here, residue numbers are indicated according to their position in α1A subunit isoform 2 and 3; however, some of them differ from the nomenclature of the mutations found in the literature: R1350Q/R1349Q corresponds to R1352Q in isoform 2, Y1385C to Y1387C in isoform 2 and Y1384C in isoform 3, V1396M is V1399M in isoform 2 and V1695I is V1700I in isoform 2.

By using the structure of the rabbit CaV1.1 complex [12], the localizations of CaV2.1 mutations can be predicted given their high level of homology. Thus, F1394L is located at the S5 segment of α1A domain III (DIII), a few amino acids downstream from the beginning of the pore-loop between S5 and S6 helices. R1664Q and R1669Q are the same mutation in α1A isoforms 3 and 2, respectively, and they affect the R2 gating charge at the voltage sensor S4 segment of domain IV (DIV) (Figure 2). The two affected residues, F1394 and R1664/R1669, are fully conserved throughout evolution (Figure 3a for comparison of orthologous CaV2.1 channels) and among all the human CaV channel family [4] (Figure 3b). Supplementary Table S1 encompasses previously CACNA1A variants linked to congenital ataxia.

3. Discussion

We present three patients with non-progressive congenital ataxia without HM or epilepsy and common dysmorphic traits. Facial dysmorphic features of all patients include a mildly asymmetric and oval face with large and prominent forehead, mild bilateral ptosis, strabismus, hypertelorism, telecanthus, downslanting palpebral fissures and narrow nasal bridge. We have identified only one previous article describing dysmorphic traits in a patient harboring a pathogenic variant in CACNA1A [13]. She had congenital ataxia with severe HM and dysmorphic facial features, including round face with high forehead and an OFC in the 90–97th centile, and carried a ΔF1502 gain-of-function variant (located at the inner pore vestibule of the CaV2.1 channel) [13]. Genetic diseases presenting congenital ataxia are frequently difficult to diagnose as cerebellar atrophy on the MRI may not be present at early stages of development and muscular hypotonia, weak deep tendon reflexes, and delayed motor milestones are unspecific neurological signs. However, a particular gestalt may help to identify genetic diseases, and, at the present time, new technologies of facial pattern recognition have demonstrated their usefulness in a wide number of genetic conditions [14].

The cerebellum expresses a variety of different functions in addition to motor action, including affective skills, working memory, response timing and attentional control, and many of the patients reported on in the literature show intellectual disability [15]. Moreover, the cerebellum is strongly associated with autism spectrum disorder (ASD); pathological studies have found consistent abnormalities in Purkinje cells in ASD patients; in addition, the cerebellum is involved in associative learning, cognition, and emotional function, which are altered in ASD [16]. Two of our patients show intellectual disability, and the most severely affected patient (patient 1) also shows autistics traits. The younger patients have ADHD with remarkable good response to methylphenidate and guanfacine, which might be explained by the impairment in cognitive executive functions and working memory described in cerebellar disorders [15].

The three patients showed an improvement in all neurodevelopmental areas, despite two of them showing a progressive cerebellar atrophy in sequential MRI. The most severe patient shows the greatest cerebellar atrophy, which suggests that there might be a correlation between the neurological impairment (including motor, speech and cognitive skills) and the degree of cerebellar atrophy (Figure 1).

Acetazolamide therapy showed clear benefit in patient 2, but not in patient 3 carrying the same CaV2.1 amino acid substitution; however, the development of renal calculi prompted us to stop the therapy. In patient 1, parents perceived a benefit in muscle tone and communication intention after acetazolamide treatment, but the lack of specific scales to evaluate cerebellar syndrome before and after the treatment limits our conclusions.

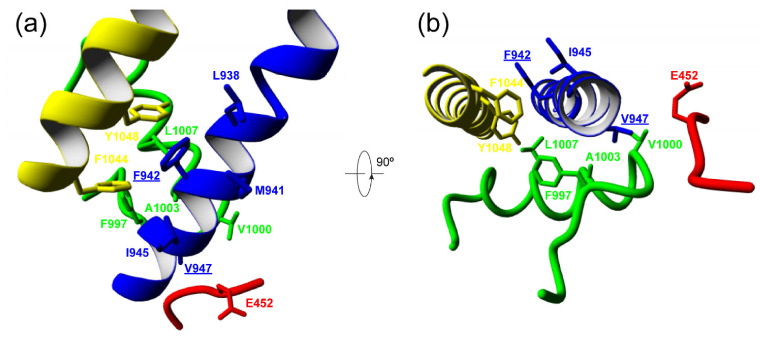

Knowledge of the mutation’s effect on protein function is important to improve our understanding of the phenotype of patients with CACNA1A-related disease and to contribute to the development of new treatment approaches. In this respect, no functional studies are available for the previously unreported F1394L variant. Still, the affected residue is located in a region of the S5 segment at DIII contributing to the channel pore. This region includes invariant amino acids conserved in the rabbit CaV1.1 (Figure 2), in CaV2.1 through evolution (Figure 3a, left) and in all human CaV channels (Figure 3b, left), which suggests high functional relevance. In this sense, two other amino acid substitutions in the same S5 pore segment where F1394L is located, Y1385C (corresponding to Y1387C in α1A isoform 2 and Y1384C in isoform 3) and V1396M (corresponding to V1399M in α1A isoform 2), have been reported in association with congenital ataxia with cerebellar atrophy, psychomotor delay, intellectual disability, epilepsy (including different kinds of refractory generalized seizures), HM and acute coma (Figure 3, left) [17,18,19]. For mutation V1396M/V1399M (five residues upstream of F1394L in α1A isoform 2), the functional analysis of the heterologously expressed murine CaV2.1 ortholog carrying the equivalent variant (V1347M) (Figure 3a, left) shows gain-of-function effects due to higher current density and lower voltage threshold for channel activation, when compared to the wild-type (WT) channel [18]. Such increase in channel activity is consistent with the close proximity of the affected residue to the initial pore-loop region that contributes to both the entrance of Ca2+ into the selectivity filter vestibule and into the docking site for the regulatory α2δ subunit [12], which is essential for the proper functional expression of the pore-forming α1A subunit at the plasma membrane [3]. Residues V1396/V1399 and F1394 are in fact fully conserved in the pore-forming α1S subunit of the rabbit CaV1.1 channel for which structural data are available [12], where they correspond to residues V947 and F942, respectively (Figure 2b). Therefore, we can evaluate whether the changes of these amino acids to methionine and leucine, respectively, and linked to cerebellar dysfunction may modify structural features of the channel subunit. According to Yasara calculation of amino acid interactions on the rabbit CaV1.1 structure, V947 mainly stablish hydrophobic contacts with three residues at the P-loop of domain III (F997, V1000 and A1003) and with the amino acid E452 at the extracellular loop between S1 and S2 of domain II (Figure 4 and Table 2 top). All these residues are conserved or semiconserved in human CaV2.1, except E452 (the equivalent amino acid is a valine) (see Table 2 Legend). By using the Amino Acid Interactions (INTAA) web server, we also estimated pairwise interaction energy (kJ/mol) between the side-chain of V947 and its neighbor residues and found that mutation V947M worsen all hydrophobic interactions, in particular with E452 (even when this amino acid is substituted by a valine as found in human CaV2.1). This may alter the correct conformation of the voltage sensor, thus explaining the increase in voltage sensitivity reported for the VM mutant channel [18].

Figure 4.

Internal CaV1.1 channel amino acid interactions affected by mutations F942L and V947M. Structure of the rabbit CaV1.1 channel showing the side-chains of F942 and V947 and Yasara-identifed interacting residues from side (a) and top (b) views. Residues L938 and M941 are hidden in panel B for visualization purposes. DII S1-S2 loop and DIII S5, P-loop and S6 are colored in red, blue, green and yellow, respectively.

Table 2.

Calculation of pairwise interaction energy (kJ/mol) between the side-chains of residues V947 (top) or F942 (bottom) (and their corresponding methionine and leucine mutants, respectively) and Yasara-calculated interacting residues. The values have been obtained with the Amino Acid Interactions (INTAA) web server using the WT or mutant rabbit CaV1.1 models, as indicated (PDB id: 5gjv). All residues interacting with V947 and F942 are conserved or semiconserved in human CaV2.1, except E452. Thus, V947 corresponds to V1396, F997 to Y1443, V1000 to V1446, A1003 to A1449 and E452 to V507 (the numbering of these CaV2.1 residues are referred to isoform 3). In the same way, F942 corresponds to F1394, L938 to F1390, M941 to I1393, I945 to V1397, L1007 to L1456, F1044 to F1493 and Y1048 to Y1497 (in this case, the numbering of the CaV2.1 amino acids are referred to isoform 2). As residue E452 is not conserved in human CaV2.1 (where the corresponding residue is a valine), we also evaluated how V947M mutation could affect the energy interaction with a valine at the same position (V452) by exchanging the sequence of the DII loop S1–S2 of rabbit CaV1.1 for that of human CaV2.1.

| E452 | V452 | F997 | V1000 | A1003 | ||

| V947 | −3.98 | −3.96 | −2.02 | −3.06 | −2.08 | |

| M947 | 47.27 | 30.3 | −1.09 | −1.93 | −0.67 | |

| Δ | +51.25 | +34.26 | +0.93 | +1.13 | +1.41 | |

| L938 | M941 | I945 | L1007 | F1044 | Y1048 | |

| F942 | −5.54 | −8.22 | −4.72 | −2.96 | −2.34 | −9.41 |

| L942 | −3.74 | −3.30 | −3.71 | −2.94 | 7.26 | 37.47 |

| Δ | +1.8 | +4.92 | +1.01 | +0.02 | +9.6 | +46.88 |

In the case of F942, Yasara identifies the interactions with other residues located at regions delineating the channel pore in domain III: L938, M941 and I945 at the S5 segment, L1007 at the P-loop, and F1044 and Y1048 at the distal half of S6 segment that faces the cytosolic side and line the inner pore vestibule of the channel (Figure 4). Again, all these interactions, specially between F942 and Y1048 (corresponding to F1394 and Y1497 in CaV2.1), are expected to be energetically worse by mutation F942L (Table 2), in this case caused by the loss of the aromatic ring and consequently the interaction. This may prevent the proper 3D arrangement of the channel inner pore. Although further research, including electrophysiological analysis, is required to confirm this hypothesis, interestingly, a gain-of-function CaV2.1 genetic variant in that precise S6 pore area (ΔF1502) associated to congenital ataxia and hemiplegic migraine, has been reported to improve voltage-dependent gating of CaV2.1 by strongly decreasing the voltage threshold for channel opening, fastening activation kinetics, and slowing down both the deactivation and the inactivation of the channel [13,20].

The functional consequences of a third mutation at the S5 segment of CaV2.1 domain III, Y1385C, has been recently reported and both gain- and loss-of-function effects have been observed [21]. As found for V1396M, Y1385C also favors channel opening by voltage (gain-of-function) [21]. However, Y1385C has the contrary effect on CaV2.1 current density, which is strongly reduced by the mutation without alteration of channel trafficking to the cell membrane (loss-of-function) [21]. Besides, Y1385C also reduces the voltage threshold for channel inactivation (loss-of-function). Nevertheless, the combination of all these alterations results in a global gain-of-function due to higher persistent activity when compared to WT channels, which can lead to a greater Ca2+ influx into cells over a physiologically relevant window of membrane potentials near the resting potential [21]. This is consistent with the association of Y1385C to HM, which is produced by CACNA1A gain-of-function mutations [1].

In the same F1394 position, a single nucleotide deletion (c.4182delC) that resulted in a putative truncated protein due to premature termination, was found in several members of an EA2 family showing variation of clinical symptoms among the carriers, ranging from severe early-onset (at the age of 1-2) weekly episodes to less severe phenotype with first attacks occurring in childhood and prolonged attack-free periods [22,23]. As all CaV2.1 truncations, it is expected to produce channel loss-of-function that is the cause of the majority of EA2 cases [1].

Several mutations affecting residues located at other CaV2.1 S5 segments have also been linked to neurological disorders, including episodic ataxia type 2 (EA2) and HM (Figure 3c, left). Two mutations affecting the Y248 residue at the S5 helix of domain I (DI) (Y248C and Y248N) and mutation L621R at the S5 helix of domain II (DII) were found in association with EA2 [24,25], a disease mostly due to CaV2.1 null or reduced activity [1]. Only mutation L621R has been studied at the functional level after heterologous expression. Unfortunately, no significant effect on CaV2.1 channel function was found to corroborate the expected loss-of-function effect. Thus, L621R did not alter CaV2.1 current density, nor channel rate of activation or inactivation [26]. Among the mutations linked to HM (mainly produced by CaV2.1 gain-of-function) are G230V at S5-DI [27], V1695I (referred to α1A isoform 3 and corresponding to V1700I in α1A isoform 2) [28] and I1710T (also referred to as I1709T and corresponding to I1714T in α1A isoform 2) [29], both at S5-DIV. Functional study of the heterologously expressed murine CaV2.1 ortholog carrying the equivalent G230V mutation (G232V) suggests a loss-of-function effect due to reduced channel expression at the cell surface [18]. Whether this effect occurs only after heterologous expression in mammalian cells but not in patients’ neurons remains controversial. Indeed, most HM-linked CACNA1A mutations show decreased density of functional CaV2.1 channels in the plasma membrane depending on the cell expression system [1], making it difficult to evaluate both the consequences of this effect in vivo and its relevance for the associated clinical phenotype, if any. In contrast, functional analysis of mutation V1695I/V1700I reveals increased channel activity due to reduced voltage threshold for CaV2.1 activation (by ~4 mV), slowed channel inactivation, and lessened direct G protein-mediated inhibition [30,31].

Regarding the R1664Q/R1669Q mutation affecting the second gating charge (R2) at DIV S4 voltage-sensing helix, it has been previously found to be linked to different ataxic phenotypes, such as EA2 and congenital ataxia [32,33,34]. In some cases, carriers present cerebellar atrophy and other symptoms, such as psychomotor delay, intellectual disability, and migraine without focal deficits. Studies performed in transgenic Drosophila flies show that the introduction of the R1664Q/R1669Q variant in the equivalent CaV2.1 (cacophony calcium-channel) does not allow rescue of synaptic transmission in a CaV2.1-deficient background, as happens with the WT channel [33]. This suggests that R1664Q/R1669Q is a loss-of-function variant, which is consistent with its linkage to EA2, mainly produced by CACNA1A loss-of-function mutations.

Other mutations of clinical relevance also modify R2 residues, as occurs with the R1664Q/R1669Q variant. This is the case with R198Q, linked to EA2 and affecting the R2 gating charge at the DI S4 segment, (Figure 3c, right), and a gain-of-function mutation linked to congenital ataxia, psychomotor delay, intellectual disability, febrile seizures, and HM (R1350Q, named as R1349Q by some authors and corresponding to R1352Q in α1A isoform 2) that locates at the equivalent R2 gating charge of DIII S4 helix (Figure 3c, right) [4,35,36,37,38].

4. Materials and Methods

Patients with a molecular confirmation of de novo variants in CACNA1A, attended at the Neurology Department of Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, and presenting with early onset ataxia were eligible. Evaluations from November 2017 to November 2020 were included. Patients with CACNA1A variants showing early epileptic encephalopathy or those with familial antecedents of HM were excluded.

For measuring cerebellar syndrome, neurological exam and assessment through ICARS, recently been validated in children with cerebellar syndrome, were performed [39]. Regarding dysmorphic evaluation, patients’ measures were compared with age and gender-related reference values from the Hall’s Handbook of Normal Physical Measurements [40].

Brain MRI exams included T1- and T2-weighted, diffusion-weighted and FLAIR sequences. To evaluate MRI cerebellar images, 2D analysis was performed using the midsagittal vermis relative diameter (MVRD) already validated in children with cerebellar atrophy [41]. This is calculated using a midsagittal section and measuring total posterior cranial fossa diameter in a linear segment from the posterior commissure to the opisthion and the largest sagittal diameter of the cerebellum parallel to the previous linear segment. The MVRD was compared to two sex- and age-matched controls from a historical cohort [41]. Lower indices denote greater cerebellar atrophy.

For molecular studies genomic DNA was isolated from venous whole blood. Mutational analysis was performed by genomic DNA analysis both in patient’ and parent samples. In the three patients a targeted gene panel of ataxia-causing genes was run. The identified likely pathogenic heterozygous variants were confirmed by Sanger sequencing in the proband and the parents, ratifying a de novo condition.

For analysis of interaction energies, calculations were performed using the rabbit CaV1.1 model (PDB id: 5gjv) and the F942L and V947M mutants, which were generated using Chimera’s rotamers tool [42]. We used Yasara’s algorithm [43] to minimize energy of models and identify interactions between residues of interest. The INTAA web server [44], which uses Lennard-Jones potential and point charges electrostatics, was used to calculate pairwise side chain interaction energies.

5. Conclusions

In conclusion, our results suggest that among the broad spectrum of CACNA1A-related phenotypes, non-progressive congenital ataxia is associated with cognitive impairment and dysmorphic features, constituting a recognizable syndromic neurodevelopmental disorder. Further studies in larger series of patients are needed to establish whether the recognition of this pattern in patients with nonspecific motor and/or cognitive impairment and cerebellar atrophy might aid in early diagnosis of CACNA1A-related disease, thereby allowing a targeted management and care of the patients and their families. Deepening of our knowledge of the effect of each mutation on protein function, to distinguish between both gain- and loss-of-function, is required to advance in the development of new personalized therapies.

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and their families for their collaboration.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijms22105180/s1, Table S1: Previously reported CACNA1A variants linked to congenital ataxia (CA) including functional consequences and molecular localization (protein domain).

Author Contributions

Conception and design of study: A.F.M.-M., D.C.-A., A.E., M.I.-S., J.M.F.-F. and M.S. Acquisition and analysis of data: all authors. Critical revision of manuscript: all authors. Drafting manuscript and figures: all authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Consumer Affairs and Social Welfare, the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, the State Research Agency (AEI, Agencia Estatal de Investigación), and FEDER Funds (Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional): Grants RTI2018-094809-B-I00 to J.M.F.F. and CEX2018-000792-M through the “María de Maeztu” Programme for Units of Excellence in R&D to “Departament de Ciències Experimentals i de la Salut”. M.S. is supported by the Generalitat de Catalunya (PERIS SLT008/18/00194) and National Grant PI17/00101 from the National R&D&I Plan, cofinanced by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Subdirectorate-General for Evaluation and Promotion of Health Research) and FEDER (European Regional Development Fund).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964, as revised in October 2013 in Fortaleza, Brazil.

Informed Consent Statement

Parents gave their written informed consent and the adolescent gave his assent for publication.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to protection data laws protecting personal medical information.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Pietrobon D. CaV2.1 channelopathies. Pflügers Arch. Eur. J. Physiol. 2010;460:375–393. doi: 10.1007/s00424-010-0802-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Catterall W.A. Ion channel voltage sensors: Structure, function, and pathophysiology. Neuron. 2010;67:915–928. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dolphin A.C. Voltage-gated calcium channels and their auxiliary subunits: Physiology and pathophysiology and pharmacology. J. Physiol. 2016;594:5369–5390. doi: 10.1113/JP272262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumkin L., Michelson M., Leshinsky-Silver E., Kivity S., Lev D., Lerman-Sagie T. congenital ataxia, mental retardation, and dyskinesia associated with a novel CACNA1A mutation. J. Child Neurol. 2010;25:892–897. doi: 10.1177/0883073809351316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calandriello L., Veneziano L., Francia A., Sabbadini G., Colonnese C., Mantuano E., Jodice C., Trettel F., Viviani P., Manfredi M., et al. Acetazolamide-responsive episodic ataxia in an Italian family refines gene mapping on chromosome 19p13. Brain. 1997;120:805–812. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.5.805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhuchenko O., Bailey J., Bonnen P., Ashizawa T., Stockton D.W., Amos C., Dobyns W.B., Subramony S., Zoghbi H.Y., Lee C.C. Autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia (SCA6) associated with small polyglutamine expansions in the α1A-voltage-dependent calcium channel. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:62–69. doi: 10.1038/ng0197-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Myers C.T., McMahon J.M., Schneider A.L., Petrovski S., Allen A.S., Carvill G.L., Zemel M., Saykally J.E., LaCroix A.J., Heinzen E.L., et al. De novo mutations in SLC1A2 and CACNA1A are important causes of epileptic encephalopathies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2016;99:287–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riant F., Lescoat C., Vahedi K., Kaphan E., Toutain A., Soisson T., Wiener-Vacher S.R., Tournier-Lasserve E. Identification of CACNA1A large deletions in four patients with episodic ataxia. Neurogenetics. 2009;11:101–106. doi: 10.1007/s10048-009-0208-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bertini E., Zanni G., Boltshauser E. Nonprogressive congenital ataxias. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018;155:91–103. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-444-64189-2.00006-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Humbertclaude V., Riant F., Krams B., Zimmermann V., Nagot N., Annequin D., Echenne B., Tournier-Lasserve E., Roubertie A., Bonnemains C., et al. Cognitive impairment in children with CACNA 1A mutations. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2020;62:330–337. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.14261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Indelicato E., Nachbauer W., Karner E., Eigentler A., Wagner M., Unterberger I., Poewe W., Delazer M., Boesch S. The neuropsychiatric phenotype in CACNA1A mutations: A retrospective single center study and review of the literature. Eur. J. Neurol. 2018;26:66.e7. doi: 10.1111/ene.13765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu J., Yan Z., Li Z., Qian X., Lu S., Dong M., Zhou Q., Yan N. Structure of the voltage-gated calcium channel Cav1.1 at 3.6 Å resolution. Nat. Cell Biol. 2016;537:191–196. doi: 10.1038/nature19321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Segarra N.G., Gautschi I., Mittaz-Crettol L., Zetchi C.K., Al-Qusairi L., Van Bemmelen M.X., Maeder P., Bonafe L., Schild L., Roulet-Perez E. Congenital ataxia and hemiplegic migraine with cerebral edema associated with a novel gain of function mutation in the calcium channel CACNA1A. J. Neurol. Sci. 2014;342:69–78. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2014.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gripp K.W., Baker L., Telegrafi A., Monaghan K.G. The role of objective facial analysis using FDNA in making diagnoses following whole exome analysis. Report of two patients with mutations in the BAF complex genes. Am. J. Med. Genet. Part A. 2016;170:1754–1762. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tavano A., Grasso R., Gagliardi C., Triulzi F., Bresolin N., Fabbro F., Borgatti R. Disorders of cognitive and affective development in cerebellar malformations. Brain. 2007;130:2646–2660. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitney E.R., Kemper T.L., Bauman M.L., Rosene D.L., Blatt G.J. Cerebellar Purkinje cells are reduced in a subpopulation of autistic brains: A stereological experiment using calbindin-D28k. Cerebellum. 2008;7:406–416. doi: 10.1007/s12311-008-0043-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vahedi K., Denier C., Ducros A., Bousson V., Levy C., Chabriat H., Haguenau M., Tournier-Lasserve E., Bousser M.G. CACNA1A gene de novo mutation causing hemiplegic migraine, coma, and cerebellar atrophy. Neurology. 2000;55:1040–1042. doi: 10.1212/WNL.55.7.1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang X., Raju P.K., D’Avanzo N., Lachance M., Pepin J., Dubeau F., Mitchell W.G., Bello-Espinosa L.E., Pierson T.M., Minassian B.A., et al. Both gain-of-function and loss-of-function de novo CACNA1A mutations cause severe developmental epileptic encephalopathies in the spectrum of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. Epilepsia. 2019;60:1881–1894. doi: 10.1111/epi.16316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Travaglini L., Nardella M., Bellacchio E., D’Amico A., Capuano A., Frusciante R., Di Capua M., Cusmai R., Barresi S., Morlino S., et al. Missense mutations of CACNA1A are a frequent cause of autosomal dominant nonprogressive congenital ataxia. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2017;21:450–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2016.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bahamonde M.I., Serra S.A., Drechsel O., Rahman R., Marcé-Grau A., Prieto M., Ossowski S., Macaya A., Fernández-Fernández J.M. A single amino acid deletion (ΔF1502) in the S6 segment of CaV2.1 domain III associated with congenital ataxia increases channel activity and promotes Ca2+ influx. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0146035. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gandini M.A., Souza I.A., Ferron L., Innes A.M., Zamponi G.W. The de novo CACNA1A pathogenic variant Y1384C associated with hemiplegic migraine, early onset cerebellar atrophy and developmental delay leads to a loss of Cav2.1 channel function. Mol. Brain. 2021;14:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s13041-021-00745-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Van den Maagdenberg A.M., Kors E.E., Brunt E.R., van Paesschen W., Pascual J., Ravine D., Keeling S., Vanmolkot K.R., Vermeulen F.L., Terwindt G.M., et al. Episodic ataxia type 2. Three novel truncating mutations and one novel missense mutation in the CACNA1A gene. J. Neurol. 2002;249:1515–1519. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0860-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jaudon F., Baldassari S., Musante I., Thalhammer A., Zara F., Cingolani L.A. Targeting alternative splicing as a potential therapy for episodic ataxia type 2. Biomedicines. 2020;8:332. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines8090332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zafeiriou D., Lehmann-Horn F., Vargiami E., Teflioudi E., Ververi A., Jurkat-Rott K. Episodic ataxia type 2 showing ictal hyperhidrosis with hypothermia and interictal chronic diarrhea due to a novel CACNA1A mutation. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2009;13:191–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Choi K.-D., Kim J.-S., Kim H.-J., Jung I., Jeong S.-H., Lee S.-H., Kim D.U., Kim S.-H., Choi S.Y., Shin J.-H., et al. Genetic variants associated with episodic ataxia in Korea. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-14254-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rajakulendran S., Graves T.D., Labrum R.W., Kotzadimitriou D., Eunson L., Davis M.B., Davies R., Wood N.W., Kullmann D.M., Hanna M.G., et al. Genetic and functional characterisation of the P/Q calcium channel in episodic ataxia with epilepsy. J. Physiol. 2010;588:1905–1913. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.186437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yang Y., Muzny D.M., Xia F., Niu Z., Person R., Ding Y., Ward P., Braxton A., Wang M., Buhay C., et al. Molecular findings among patients referred for clinical whole-exome sequencing. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2014;312:1870–1879. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.14601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ducros A., Denier C., Joutel A., Cecillon M., Lescoat C., Vahedi K., Darcel F., Vicaut E., Bousser M.-G., Tournier-Lasserve E. The clinical spectrum of familial hemiplegic migraine associated with mutations in a neuronal calcium channel. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001;345:17–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200107053450103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kors E.E., Melberg A., Vanmolkot K.R.J., Kumlien E., Haan J., Raininko R., Flink R., Ginjaar H.B., Frants R.R., Ferrari M.D., et al. Childhood epilepsy, familial hemiplegic migraine, cerebellar ataxia, and a new CACNA1A mutation. Neurology. 2004;63:1136–1137. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000138571.48593.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Müllner C., Broos L.A.M., van den Maagdenberg A.M.J.M., Striessnig J. Familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 mutations K1336E, W1684R, and V1696I alter CaV2.1 Ca2+ channel gating: Evidence for β-subunit isoform-specific effects. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:51844–51850. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408756200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garza-López E., Sandoval A., González-Ramírez R., Gandini M.A., Van Den Maagdenberg A., De Waard M., Felix R. Familial hemiplegic migraine type 1 mutations W1684R and V1696I alter G protein-mediated regulation of CaV2.1 voltage-gated calcium channels. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1822:1238–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2012.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denier C., Ducros A., Durr A., Eymard B., Chassande B., Tournier-Lasserve E. Missense CACNA1A mutation causing episodic ataxia type 2. Arch. Neurol. 2001;58:292–295. doi: 10.1001/archneur.58.2.292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luo X., Rosenfeld J.A., Yamamoto S., Harel T., Zuo Z., Hall M., Wierenga K.J., Pastore M.T., Bartholomew D., Delgado M.R., et al. Clinically severe CACNA1A alleles affect synaptic function and neurodegeneration differentially. PLoS Genet. 2017;13:e1006905. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tonelli A., D’Angelo M.G., Salati R., Villa L., Germinasi C., Frattini T., Meola G., Turconi A.C., Bresolin N., Bassi M.T. Early onset, non fluctuating spinocerebellar ataxia and a novel missense mutation in CACNA1A gene. J. Neurol. Sci. 2006;241:13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miki T., Zwingman T.A., Wakamori M., Lutz C.M., Cook S.A., Hosford D.A., Herrup K., Fletcher C.F., Mori Y., Frankel W.N., et al. Two novel alleles of tottering with distinct Ca(v)2.1 calcium channel neuropathologies. Neuroscience. 2008;155:31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.05.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Blumkin L., Leshinsky-Silver E., Michelson M., Zerem A., Kivity S., Lev D., Lerman-Sagie T. Paroxysmal tonic upward gaze as a presentation of de-novo mutations in CACNA1A. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2015;19:292–297. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpn.2014.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tantsis E.M., Gill D., Griffiths L., Gupta S., Lawson J., Maksemous N., Ouvrier R., Riant F., Smith R., Troedson C., et al. Eye movement disorders are an early manifestation of CACNA1A mutations in children. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 2016;58:639–644. doi: 10.1111/dmcn.13033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Camia F., Pisciotta L., Morana G., Schiaffino M.C., Renna S., Carrera P., Ferrari M., Baglietto M.G., Veneselli E., Siri L., et al. Combined early treatment in hemiplegic attacks related to CACNA1A encephalopathy with brain oedema: Blocking the cascade? Cephalalgia. 2016;37:1202–1206. doi: 10.1177/0333102416668655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serrano M., De Diego V., Muchart J., Cuadras D., Felipe A., Macaya A., Velázquez R., Poo M.P., Fons C., O’Callaghan M.M., et al. Phosphomannomutase deficiency (PMM2-CDG): Ataxia and cerebellar assessment. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2015;10:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0358-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gripp K.W., Slavotinek A.M., Hall J.G., Allanson J.E. Handbook of Physical Measurements. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Diego V., Martínez-Monseny A.F., Muchart J., Cuadras D., Montero R., Artuch R., Pérez-Cerdá C., Pérez B., Pérez-Dueñas B., Poretti A., et al. Longitudinal volumetric and 2D assessment of cerebellar atrophy in a large cohort of children with phosphomannomutase deficiency (PMM2-CDG) J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2017;40:709–713. doi: 10.1007/s10545-017-0028-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Couch G.S., Greenblatt D.M., Meng E.C., Ferrin T.E. UCSF Chimera—A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krieger E., Vriend G. YASARA View—Molecular graphics for all devices—From smartphones to workstations. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2981–2982. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Galgonek J., Vymětal J., Jakubec D., Vondrášek J. Amino Acid Interaction (INTAA) web server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W388–W392. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to protection data laws protecting personal medical information.