Abstract

The nematode Haemonchus contortus (the barber’s pole worm) is an endoparasite infecting wild and domesticated ruminants worldwide. Widespread anthelmintic resistance of H. contortus requires alternative strategies to control this parasite. Neuropeptide signaling represents a promising target for anthelmintic drugs. Identification and relative quantification of nematode neuropeptides are, therefore, required for the development of such therapeutic targets. In this work, we undertook the profiling of the whole H. contortus larvae at different stages for the direct sequencing of the neuropeptides expressed at low levels in these tissues. We set out a peptide extraction protocol and a peptidomic workflow to biochemically characterize bioactive peptides from both first-stage (L1) and third-stage larvae (L3) of H. contortus. This work led to the identification and quantification at the peptidomic level of more than 180 mature neuropeptides, including amidated and nonamidated peptides, arising from 55 precursors of H. contortus. The differential peptidomic approach provided evidence that both life stages express most FMRFamide-like peptides (FLPs) and neuropeptide-like proteins (NLPs). The H. contortus peptidome resource, established in this work, could add the discovery of neuropeptide system-targeting drugs for ruminants.

Introduction

Haemonchus contortus is a very common endoparasite and one of the most pathogenic nematodes infecting wild and domesticated ruminants worldwide.1 It lives in the abomasum, causing hemorrhagic gastritis, anemia, edema, and even death of the infected animals.2

H. contortus exhibits a monoxenous life cycle that consists of a free-living phase in the external environment and a parasitic phase in the infested host animal.3 The life cycle begins with the laying of eggs by H. contortus females. The first-stage larvae (L1s) develops inside the eggs after their excretion in the host feces and molts to the second stage (L2s) and then into the third-stage larvae (L3s) within approximately 1 week. The infective L3s are then ingested by the host animal, undergo an exsheathment process to develop to become fourth-stage larvae (L4s) and then to dioecious adults within 3 weeks in the stomach. The last two stages feed on blood from capillaries of the abomasal wall.

Haemonchosis is mainly controlled by anthelmintics, which act by compromising the nematode motor function.4−6 However, the increase in resistance to existing chemotherapeutics warrants the identification of new parasiticides with novel modes of action.7−9 As neuropeptides and their receptors regulate many vital biological processes (such as development, behavior, movement, metabolism, and reproduction5,10), the nematode neuropeptide signaling system has been proposed as a promising target for novel drugs against helminths.11 Neuropeptides consist of short peptides that are derived from larger precursor proteins by the action of processing enzymes and are commonly subjected to post-translational modifications.12 Three large neuropeptide groupings occur in nematodes, two of which are defined by conserved structural features (the FMRFamide-like peptides (FLPs)12−15 and insulin-like peptides (INSs)).16 The FMRFamide-like peptides (FLPs) are a group of neuropeptides that are similar to the tetrapeptide FMRF-amide (H-Phe-Met-Arg-Phe-NH2), a cardioexcitatory peptide first isolated from the mollusk Macrocallista nimbosa.17 Neuropeptides sharing a C-terminal RFamide motif have been further identified from other organisms and were defined as FLPs. The third group comprises all other neuropeptides and includes diverse family groupings (the neuropeptide-like proteins NLPs.) Unlike FLPs and INSs that each comprise single families, the NLPs were originally defined as encompassing 11 distinct peptide families.18,19 The most studied neuropeptide family in nematodes is the FLP gene family: all contain a variation in the tetrapeptide motif X/Y-X-RF-amide where X is a nonpolar hydrophobic (L, I, M or V) residue and Y is aromatic.12,14,15,20

Detailed knowledge on neuropeptide sequences in parasitic nematodes and their post-translational modifications is required to help building an understanding of their in vivo biology and physiological role. The availability of genomic and transcriptomic data sets and the development of in silico mining tools have enabled the identification of neuropeptide genes and further prediction of neuropeptide sequences.21−23 However, these in silico discovery approaches suffer major drawbacks in that the end products are bioactive peptides that can be modified, nonclassically cleaved, or even mispredicted.24 The development and application of sensitive mass spectrometry-based peptidomic technologies25 have enabled the biochemical identification of many nematode neuropeptides.22,26,27 Of particular interest is the recent work performed on Caenorhabditis elegans in which a peptidomic analysis was performed to identify unprecedented 203 mature neuropeptides from C. elegans.28,29 Previous high-throughput peptidomic approaches on parasitic nematodes have been confined to the large gastrointestinal parasite of pigs, Ascaris suum.22,30 No such studies have been reported on other nematode parasites and only two FLP neuropeptides have been characterized biochemically from H. contortus.31,32 In this paper, we report on a comprehensive peptidomic study to biochemically monitor, identify, and quantify endogenous peptides from two larval stages (the first-stage larvae (L1s) and the third-stage larvae (L3s)) of H. contortus through a peptidomic workflow using the recent release of two genome assemblies for H. contortus.33,34

This study aimed at characterizing the whole-worm peptidome of L1 and L3 larval stages of H. contortus using a label-free peptidomic approach. Peptidome exploration of essential developmental stages of H. contortus will provide a valuable repository for a better understanding of this nematode at the biochemical level.

Results

Genomic and Transcriptomic Data Set Interrogation

The direct identification of bioactive peptides using a mass spectrometry (MS)-based strategy relies on mapping the peptide masses identified to a reference data set (predicted from genome and/or transcriptome). There are two genomic and transcriptomic data sets publicly available for H. contortus.33,34 The two versions of the genome and transcriptome presented in both publications are available on the WormBase site (https://wormbase.org) (BioProject PRJNA205202 and BioProject PRJEB506). The protein FASTA files for both BioProjects can be downloaded from the WormBase site. It is noteworthy that for the BioProject PRJEB506, the genome reported for H. contortus has been updated in the WormBase version 11.0, whereas all of the PRJNA205202 versions have remained unchanged.

Before submitting MS/MS data for database searching, we analyzed the two H. contortus draft genomes and transcriptomes, PRJNA205202 version 14 (WBPS14) and PRJEB506 version 14 (WBPS14) and version 10 (WBPS10), for the presence of potential FLPs using the H. contortus C-terminal FLP motifs and FLP-gene sequelogues identified by McCoy et al. in a pan-phylum bioinformatics study14 (Table 1).

Table 1. Presence of FMRFamide-like Peptide Encoding Genes (FLPs) in Genomic and Transcriptomic Data Sets of H. contortus.

From McCoy et al.14 gray shading indicates the presence of a gene. The number of copies of a predicted peptide is indicated as (no.×). Complete sequence of flp-32 was found in Atkinson et al.35 X0 denotes a hydrophobic amino acid. One peptide among the four amidated peptides predicted from the flp-11 precursor is not an flp peptide. This peptide is indicated in italics.

flp-19 sequence was present in previous PRJEB506 release (versions to 10) but not in versions 11–14.

Among the 32 FLP-encoding genes identified in 17 nematode parasites, 26 have been reported for H. contortus, highlighted in gray in Table 1.14,36 Each flp gene encodes one or several FLPs, up to 8, for a total of 62 different predicted FLPs. Eleven FLP sequences (flp-1, flp-5, flp-6, flp-14, flp-15, flp-17, flp-18, flp-21, flp-25, flp-33, and flp-34) were identified within both the H. contortus databases reported in PRJEB506 and PRJNA205202 (WormBase), with some discrepancies in sequences for flp-5, flp-14, and flp-18 (Table 1). Eleven flp transcripts (flp-2, flp-7, flp-8, flp-9, flp-11, flp-12, flp-13, flp-16, flp-19, flp-22, and flp-24) were found only in PRJEB506 with some discrepancies in sequence for flp-7 and flp-16. Flp-28 was only identified in PRJNA205202. Surprisingly, flp-19 was present in previous PRJEB506 releases (versions 1–10) but not in versions 11–14. Finally, three flp sequences (flp-20, flp-23, and flp-32) were not identified in either database (Figure 2); flp-32 was reported by Atkinson et al.35

Figure 2.

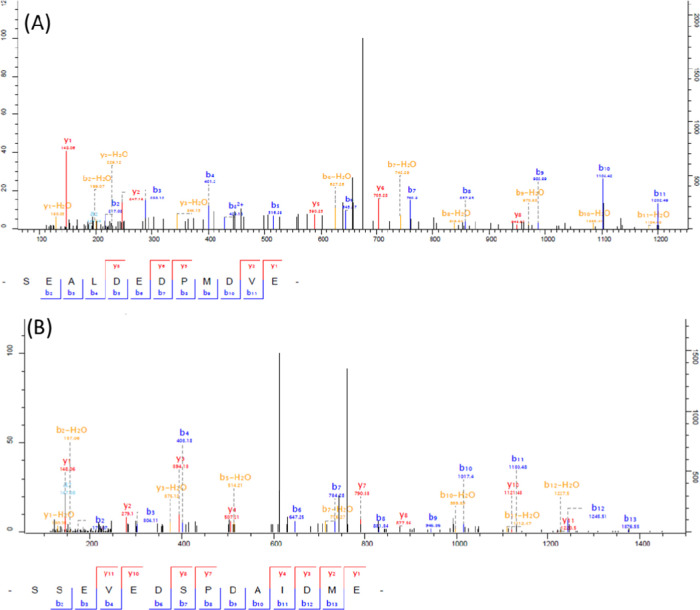

MS/MS spectra of two unmodified peptides of the H. contortusflp-6. The fragmentation schemes enabled the identification of the peptide SEALDEDPMDVE in the WormBase, PRJEB506.WBPS10 database analysis (A), and of the peptide SSEVEDSPDAIDME upon the analysis of both PRJEB506.WBPS14 and PRJNA205202.WBPS14 WormBase (B).

To maximize peptide identification using our approaches, we used a combination of the two transcriptome databases (PRJEB506 and PRJNA205202) with a homemade database that we constructed from the sequelogue sequences described14 (Supplementary Data 1).

Identification of Neuropeptides

To biochemically identify endogenous FLP peptides and other bioactive peptides of H. contortus, a peptide acidic/methanol extraction method was used (see the Methods section). Peptides extracted from both first-stage (L1) and third-stage larvae (L3) of H. contortus were analyzed by LC/MS/MS, and the results were processed in the MaxQuant environment implemented with the three FASTA databases described in the above paragraph. This way, we sequenced 181 endogenous peptides belonging to 55 different peptide precursor proteins.

FMRFamide-like Peptides

Among the 26 FLP genes described for H. contortus, there are 62 predicted FMRFamide-like peptides (Table 1). In addition, two peptides not strictly belonging to the FLPs can be found, the flp-11 peptide (YLATDDDYATAAAQG) described as a neuropeptide and the RYamide flp-34 peptide (SDLSDFASAINSAGRLRYG).

In this work, we isolated and identified 54 of the 62 predicted peptides (Table 2) across the two larval stages. Only two of these peptides were previously biochemically characterized, KHEYLRF.NH2 (flp-14) and KSAYMRF.NH2 (flp-6), by Keating et al.31 and Marks et al.32

Table 2. FLP-Amidated Peptides Identified in the First-Stage (L1) and Third-Stage Larvae (L3) of H. contortus.

| gene | precursor namea | database | sequence | modifications | mass | start position | end position |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| flp-1 | HCON_00103480; maker-scaffold1982-snap-gene-0.20-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | KPNFMRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 937.4956 | 70 | 77 |

| flp-1 | HCON_00103480; maker-scaffold1982-snap-gene-0.20-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GSDPNFLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1050.525 | 87 | 96 |

| flp-1 | HCON_00103480; maker-scaffold1982-snap-gene-0.20-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | NQPNFLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1033.546 | 98 | 106 |

| flp-1 | HCON_00103480; maker-scaffold1982-snap-gene-0.20-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AAGDPNFLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1105.567 | 118 | 128 |

| flp-1 | HCON_00103480; maker-scaffold1982-snap-gene-0.20-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GAGDPNFLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1091.551 | 130 | 140 |

| flp-1 | HCON_00103480; maker-scaffold1982-snap-gene-0.20-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GVDPNFLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1062.561 | 143 | 152 |

| flp-1 | HCON_00103480; maker-scaffold1982-snap-gene-0.20-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | KPNFLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 919.5392 | 154 | 161 |

| flp-2 | HCON_00188000 | PRJEB506 | FRGEPIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1019.567 | 39 | 47 |

| flp-2 | HCON_00188000 | PRJEB506 | VPREPIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1011.598 | 50 | 58 |

| flp-5 | HCON_00164350; maker-scaffold856-augustus-gene-0.7-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | APKFIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 876.5334 | 37 | 44 |

| flp-5 | HCON_00164350; maker-scaffold856-augustus-gene-0.7-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GGGAKFIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 950.545 | 46 | 55 |

| flp-5 | HCON_00164350; maker-scaffold856-augustus-gene-0.7-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506 | AAKFIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 850.5177 | 80 | 87 |

| flp-6 | HCON_00155670; augustus-scaffold18780-abinit-gene-0.3-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | KSAYMRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 900.464 | 32 | 39 |

| flp-7 | HCON_00164220 | PRJEB506 | TPMVRSSMVRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1308.68 | 42 | 53 |

| flp-7 | HCON_00164220 | PRJEB506 | APMDRSAMVRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1278.633 | 56 | 67 |

| flp-7 | HCON_00164220 | PRJEB506 | APMDRSSMVRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1294.627 | 97 | 108 |

| flp-8 | HCON_00180390 | PRJEB506 | KNEFIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 951.529 | 3 | 10 |

| flp-9 | HCON_00131250 | PRJEB506 | KPSFVRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 878.5127 | 69 | 76 |

| flp-11 | HCON_00176100 | PRJEB506 | AMRNALVRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1075.607 | 31 | 40 |

| flp-11 | HCON_00176100 | PRJEB506 | AGGSMRNALVRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1276.682 | 42 | 54 |

| flp-11 | HCON_00176100 | PRJEB506 | YLATDDDYATAAAQG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1486.658 | 57 | 71 |

| flp-11 | HCON_00176100 | PRJEB506 | NGAPQPFVRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1130.599 | 74 | 84 |

| flp-12 | HCON_00164300 | PRJEB506 | NKFEFIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1098.597 | 74 | 82 |

| flp-13 | HCON_00095850 | PRJEB506 | SFEENASPLIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1407.715 | 44 | 56 |

| flp-13 | HCON_00095850 | PRJEB506 | DLSGAPLIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1086.619 | 59 | 69 |

| flp-13 | HCON_00095850 | PRJEB506 | APEAHPLIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1148.646 | 71 | 81 |

| flp-13 | HCON_00095850 | PRJEB506 | APDSAPLIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1084.603 | 84 | 94 |

| flp-13 | HCON_00095850 | PRJEB506 | DPEASPLIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1142.608 | 96 | 106 |

| flp-13 | HCON_00095850 | PRJEB506 | SPAAPLIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 969.576 | 109 | 118 |

| flp-13 | HCON_00095850 | PRJEB506 | SPNASPLIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1099.614 | 120 | 130 |

| flp-14 | HCON_00084500; maker-scaffold19612-snap-gene-0.18-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | KHEYLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 990.5399 | 93 | 100 |

| flp-15 | HCON_00084140 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AGPQGPLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 940.5243 | 41 | 49 |

| flp-15 | HCON_00084140 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GPSGPLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 828.4606 | 53 | 61 |

| flp-16 | HCON_00035475 | PRJEB506 | AQTFVRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 866.4763 | 70 | 77 |

| flp-17 | HCON_00123460; maker-C469629-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | KSAFVRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 852.497 | 72 | 79 |

| flp-17 | HCON_00123460; maker-C469629-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | KSQYIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 939.529 | 112 | 119 |

| flp-18 | HCON_00164730; augustus-scaffold2866-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | DLDGGMPGVLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1274.644 | 54 | 66 |

| flp-18 | HCON_00164730; augustus-scaffold2866-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | EVPGVLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 914.5338 | 76 | 84 |

| flp-18 | HCON_00164730; augustus-scaffold2866-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SMPGVLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 904.4953 | 91 | 99 |

| flp-18 | HCON_00164730; augustus-scaffold2866-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SVPGVLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 872.5232 | 102 | 110 |

| flp-18 | HCON_00164730; augustus-scaffold2866-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | EMPGVLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 946.5059 | 113 | 121 |

| flp-18 | HCON_00164730; augustus-scaffold2866-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AMPGVLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 888.5004 | 124 | 132 |

| flp-18 | HCON_00164730; augustus-scaffold2866-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | TEIPGMMRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1079.526 | 135 | 144 |

| flp-18 | HCON_00164730; augustus-scaffold2866-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | NVPGVLRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 899.5341 | 161 | 169 |

| flp-19 | HCOI00587500b | PRJEB506.WBPS10 | WANQVRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 918.4824 | 50 | 57 |

| flp-19 | HCOI00587500a | PRJEB506.WBPS10 | ASSWASSIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1109.562 | 60 | 70 |

| flp-22 | HCON_00012150 | PRJEB506 | TPSAKWMRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1121.58 | 37 | 46 |

| flp-22 | HCON_00012150 | PRJEB506 | SPNAKWMRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1134.576 | 49 | 58 |

| flp-22 | HCON_00012150 | PRJEB506 | TPDAKWMRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1149.575 | 61 | 70 |

| flp-24 | HCON_00094680 | PRJEB506 | VPSAGDMMVRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1207.584 | 53 | 64 |

| flp-25 | HCON_00078750; maker-scaffold165-snap-gene-0.6-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | HYDFVRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 981.4821 | 47 | 54 |

| flp-25 | HCON_00078750; maker-scaffold165-snap-gene-0.6-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | ASYDYIRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1032.503 | 63 | 71 |

| flp-33 | HCON_00009870; maker-scaffold18501-snap-gene-0.8-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SIDEIQKPRFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1230.672 | 66 | 76 |

| flp-34 | HCON_00140260; maker-scaffold19714-augustus-gene-0.9-mRNA-1 | PRJNA205202 | SDLSDFASAINSAGRLRYG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1940.97 | 51 | 69 |

The precursor name corresponds either to the one reported in project PRJEB506 or to the one described in project PRJNA205202 on the WormBase site. When sequences are predicted by both databases, the peptide sequence start and end positions refer to the database indicated first.

Denotes identified sequences from the PRJEB506 release (versions previous version 10).

All predicted FLP precursors were found except flp-20, flp-21, flp-23, flp-28, and flp-32. It is noteworthy that flp-20, flp-23, and flp-32 were not identified in either of the WormBase data sets, although the complete flp-32 sequence was previously reported.35 In the study performed on C. elegans by Van Bael et al.,28,29 the bioactive peptides issued from these precursors were either not detected or could not be confirmed using MS/MS. Peptides predicted to be encoded by flp-1, flp-2, flp-6, flp-8, flp-9, flp-11, flp-12, flp-13, flp-15, flp-17, flp-19, flp-24, flp-25, flp-33, and flp-34 transcripts, which had identical sequences between those reported in MacCoy et al.14 and both WormBase databases, were all unambiguously identified in this study, except for one peptide (APITSKLIQSLNEAERLRFG) arising from flp-34 (Table 1), not detected in this study. Peptides arising from flp-19 (WANQVRFG and ASSWASSIRFG) whose sequences were removed from the updated versions of PRJEB506 were unambiguously identified in this study.

For peptides showing sequence discrepancies across those reported14 and the WormBase data sets (Figure 1; Table 1), the use of a combination of all three data sets enabled sequence confirmation. For flp-5, flp-7, flp-16, and flp-18, the correct predicted sequences are those reported in the WormBase data sets. The peptide KHEYLRFSRG arising from flp-14 and predicted only by the sequelogue database was not detected in this study, whereas the other flp-14-predicted peptide (KHEYLRFG) was unambiguously identified. This raises the question of the occurrence of the undetected peptide.

Figure 1.

Presence of flp-gene sequences in the H. contortus databases reported in PRJEB506 (pink circle) and PRJNA205202 (blue circle) on WormBase (https://wormbase.org). Flp-20, flp-23, and flp-32 were described by McCoy et al.14 and flp-32 by Atkinson et al.35 * indicates discrepancies between sequences reported in McCoy et al.14 and databases from Wormbase. ** Flp-19 sequence was present in the previous PRJEB506 release (versions to 10) but not in versions 11–14.

In addition to the confirmation that peptides were all amidated at the C-terminus, we also searched for additional processed peptides as described for C. elegans.29 The authors looked for potential peptides derived from predicted neuropeptides precursors, which are flanked by (di)basic residues and which were not identified as mature peptides. Applying the same strategy to our H. contortus peptidomic data set, we could identify 14 additional peptides arising from 10 FLP precursors (Table 3). Here again, the interrogation of both worm databases led to the identification of the correct sequences for these additional peptides derived from flp-5, flp-6, flp-15, and flp-17.

Table 3. flp-Gene-Encoded Non-FLP Peptides Identified in the First-Stage (L1) and Third-Stage Larvae (L3) of H. contortus.

| gene | precursor namea | database | sequence | modifications | mass | start positionb | end positionb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| flp-2 | HCON_00188000 | PRJEB506 | GPMFEPYFDY | unmodified | 1264.511 | 61 | 70 |

| flp-5 | HCON_00164350 | PRJEB506 | SGTNTWDDDSSDITSYAHQDD | unmodified | 2328.889 | 57 | 77 |

| flp-6 | HCON_00155670; augustus-scaffold18780-abinit-gene-0.3-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SDPELADQMMME | unmodified | 1395.536 | 41 | 52 |

| flp-6 | HCON_00155670 | PRJEB506 | SEALDEDPMDVE | unmodified | 1348.534 | 65 | 76 |

| flp-6 | HCON_00155670; augustus-scaffold18780-abinit-gene-0.3-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SSEVEDSPDAIDME | unmodified | 1522.598 | 99 | 112 |

| flp-11 | HCON_00176100 | PRJEB506 | SGHLDHIHDILSTLQKLQLANYH | unmodified | 2652.377 | 86 | 108 |

| flp-13 | HCON_00095850 | PRJEB506 | VDTLSRES | unmodified | 905.4454 | 35 | 42 |

| flp-15 | U6PJU1 CBN-FLP-15protein GN=HCOI 01474400 | PRJEB506 | EIEDITDDSK | unmodified | 1163.519 | 22 | 31 |

| flp-15 | U6PJU1 CBN-FLP-15protein GN=HCOI 01474400 | PRJEB506 | STFDYPTVFDQQPYYYFV | unmodified | 2279.01 | 64 | 81 |

| flp-17 | HCON_00123460; maker-C469629-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AAEESAEIE | unmodified | 947.4084 | 82 | 90 |

| flp-17 | maker-C469629-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJNA205202 | SAAEFDMPE | unmodified | 995.3906 | 102 | 110 |

| flp-18 | HCON_00164730; augustus-scaffold2866-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | STYDTIPLELLD | unmodified | 1378.687 | 147 | 148 |

| flp-25 | HCON_00078750; maker-scaffold165-snap-gene-0.6-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SQIDSDDLNARFSPYQFL | unmodified | 2114.991 | 74 | 91 |

| flp-33 | HCON_00009870; maker-scaffold18501-snap-gene-0.8-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SPLEGFEDISSMM | unmodified | 1441.611 | 52 | 64 |

The precursor name corresponds either to the one reported in project PRJEB506 or to the one described in project PRJNA205202 on the WormBase site.

When sequences are predicted by both databases, the peptide sequence start and end positions refer to the database indicated first.

For example, we found two additional non-FLP peptides encoded on flp-17, with one (AAEESAEIE) correctly predicted by both databases and the other (SAAEFDMPE) arising from the PRJEB506 database only. Flp-6 gives rise to two additional non-FLP peptides (SDPELADQMMME and SSEVEDSPDAIDME) having the same predicted sequences on both databases: PRJEB506.WBPS14 and PRJNA205202.WBPS14. We also identified the peptide (SEALDEDPMDVE) predicted only by the database PRJEB506.WBPS10 (version before the update). The PRJEB506.WBPS14 database predicted the sequence (SEALEEDPMDVE), which was not identified in this study. Interestingly, the peptide (SSEVEDSPDAIDME) was wrongly predicted by the previous version, PRJEB506.WBPS10. Figure 2 shows the MS/MS spectra of the peptides SSEVEDSPDAIDME and SEALDEDPMDVE. Figure S1 illustrates different predicted flp-6 sequence alignments.

All FLP precursor sequences identified in this study were aligned with the corresponding C. elegans FLP gene precursors (Figure S1). These alignments emphasize the strong homologies of bioactive peptides and their mono- and di-basic cleavage sites across nematode species, as highlighted.14 This is illustrated in Figure 3 with the alignment of flp-11 precursors for both H. contortus and C. elegans. The four amidated peptides observed for C. elegansflp-11 were also detected for H. contortus, with one of them being amidated on a glutamine residue in both species. Compared to the studies of Van Bael et al.,28,29 we were able to sequence the C-terminal peptide (SGHLDHIHDILSTLQKLQLANYH).

Figure 3.

Sequence alignments of H. contortusflp-11 (sequence in the BioProject PRJEB506 protein fasta file, Wormbase source) with C. elegansflp-11 (UniProtKB source). Sequences were aligned using the Clustal Omega program (http://www.clustal.org). Predicted signal peptide is indicated in italics. Putative mono- and di-basic cleavage sites are shown in red. The potential C-terminal glycine residues for amidation are indicated in brown. C. elegans peptide data shown in the study of Van Bael et al.29 are highlighted in blue. H. contortus FLP peptide sequences identified in this study are shown in bold green with the sequence of the unmodified peptides being underlined. The amidated glutamine residues identified in both species are indicated in purple.

NLP Peptides

The identification of NLP peptides was carried out in association with the two PRJEB506 (version 10 and version 14) and PRJNA205202 WormBase data sets (there were no additional resources for NLP precursors as there was for FLP precursors). In addition, we performed a BLAST analysis of the 82 NLP precursors of C. elegans reported,28,29 against the PRJEB506 and PRJNA205202 data sets. In total, 42 nlpH. contortus genes could be found using this BLAST approach (Table S1). Among these 42 nlp genes, 20 were predicted by both PRJNA205202 and PRJEB506 BioProjects and 22 were found only in the PRJEB506 data set. As noticed for FLP precursors, some NLP precursors (those from nlp-1, nlp-19, nlp-35, and nlp-69) were only predicted by the PRJEB506 versions before the update (versions 1–10), whereas nlp-10, nlp-12, and nlp58 were found in the updated PRJEB506 versions (versions 11–14).

In this study, we clearly detected and identified 110 putative bioactive neuropeptides encoded by 33 of these 42 predicted NLP precursors (Table 4). We also identified three additional peptides arising from the precursor HCON_00135420 (PRJEB506 nomenclature), which could not be assigned by BLAST searches to any C. elegans precursor.

Table 4. NLP Peptides Identified in the First-Stage (L1) and Third-Stage Larvae (L3) of H. contortus.

| NLP | precursor namea | database | sequence | modifications | mass | start positionb | end positionb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nlp-1c | HCOI00158100 | PRJEB506.WBPS10 | AVMFPRTFGALFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1354.722 | 31 | 43 |

| nlp-1c | HCOI00158100 | PRJEB506.WBPS10 | MDMKHYFVGLG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1238.594 | 82 | 92 |

| nlp-3 | HCON_00188680 | PRJEB506 | AINPFLDSMG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1005.495 | 28 | 37 |

| nlp-3 | HCON_00188680 | PRJEB506 | AVNPFLDSFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1007.508 | 40 | 49 |

| nlp-3 | HCON_00188680 | PRJEB506 | SSRYQPYYHLD | unmodified | 1427.647 | 52 | 62 |

| nlp-3 | HCON_00188680 | PRJEB506 | YFDSLAGQALG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1082.54 | 65 | 75 |

| nlp-5 | HCON_00046600; maker-C469189-snap-gene-0.14-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | ALSSFDTLGGIGLG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1248.671 | 42 | 55 |

| nlp-5 | HCON_00046600 | PRJEB506 | TQLSSIDSLGGLGLG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1358.741 | 46 | 60 |

| nlp-5 | HCON_00046600; maker-C469189-snap-gene-0.14-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SEDTAKKALSSFDTLGGIGLG | Gly-loss+Amide | 2008.048 | 123 | 143 |

| nlp-5 | HCON_00046600; maker-C469189-snap-gene-0.14-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | DDMLAGEKKSVSSFDTLAGIGLG | Gly-loss+Amide | 2252.136 | 146 | 168 |

| nlp-5 | maker-C469189-snap-gene-0.14-mRNA-1 | PRJNA205202 | SRLFSTYYYLPYRDSLEDMDQNAQE | unmodified | 3103.387 | 171 | 195 |

| nlp-5 | HCON_00046600 | PRJEB506 | SRLFSTYYYLPYRDSLEDMDQNVQE | unmodified | 3131.418 | 127 | 151 |

| nlp-7 | HCON_00165470; maker-C452207-snap-gene-0.3-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | LVIPSYLSSHYD | unmodified | 1392.693 | 32 | 43 |

| nlp-7 | HCON_00165470; maker-C452207-snap-gene-0.3-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | TLDFDDPRLFSTAFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1642.799 | 46 | 60 |

| nlp-7 | HCON_00165470; maker-C452207-snap-gene-0.3-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | NGLVTTTLNRPRFI | unmodified | 1600.905 | 63 | 76 |

| nlp-7 | HCON_00165470; maker-C452207-snap-gene-0.3-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SPFLGTNVGLAYI | unmodified | 1350.718 | 79 | 91 |

| nlp-7 | HCON_00165470; maker-C452207-snap-gene-0.3-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | ADMDPRFISNSFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1397.64 | 94 | 106 |

| nlp-7 | HCON_00165470; maker-C452207-snap-gene-0.3-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | STLYDFDDPRFASLSFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1878.879 | 109 | 125 |

| nlp-7 | HCON_00165470; maker-C452207-snap-gene-0.3-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SGFDFDDPRFSSMSFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1739.725 | 128 | 143 |

| nlp-7 | HCON_00165470; maker-C452207-snap-gene-0.3-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SGFDLEDPRFASMSFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1703.761 | 146 | 161 |

| nlp-7 | HCON_00165470; maker-C452207-snap-gene-0.3-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SGFN FEDPRFASLSFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1718.805 | 164 | 179 |

| nlp-7 | HCON_00165470; maker-C452207-snap-gene-0.3-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SGFDLDDPRFASMSFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1689.746 | 182 | 197 |

| nlp-7 | HCON_00165470 | PRJEB506 | SGSDLEDPRYWSMSFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1774.762 | 200 | 215 |

| nlp-8 | HCON_00010710; maker-scaffold14524-snap-gene-0.4-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AFDRIESN DFGLF | unmodified | 1529.715 | 49 | 61 |

| nlp-8 | HCON_00010710; maker-scaffold14524-snap-gene-0.4-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AFDRIEMADFGF | unmodified | 1417.634 | 69 | 80 |

| nlp-8 | HCON_00010710; maker-scaffold14524-snap-gene-0.4-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AFDRVGRTEFGFEGVL | unmodified | 1798.9 | 85 | 100 |

| nlp-8 | HCON_00010710; maker-scaffold14524-snap-gene-0.4-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | TEFGFEGVL | unmodified | 997.4757 | 92 | 100 |

| nlp-8 | HCON_00010710; maker-scaffold14524-snap-gene-0.4-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AADRLADIGFRN | unmodified | 1317.679 | 104 | 115 |

| nlp-9 | HCON_00136940; maker-scaffold10126-snap-gene-0.11-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GGARAFHGYFNMPSS | unmodified | 1597.71 | 48 | 62 |

| nlp-9 | HCON_00136940; maker-scaffold10126-snap-gene-0.11-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | LSGEYPYYLYE | unmodified | 1395.623 | 65 | 75 |

| nlp-9 | maker-scaffold10126-snap-gene-0.11-mRNA-1 | PRJNA205202 | GGGRAFFGGWQPYESLGARMD | unmodified | 2258.033 | 78 | 98 |

| nlp-9 | HCON_00136940; maker-scaffold10126-snap-gene-0.11-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SSSLWEFLEDRNAL | unmodified | 1665.8 | 127 | 140 |

| nlp-10 | HCON_00073270; maker-scaffold13486-augustus-gene-0.18-mRNA- | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AVMPFSGGLYG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1039.516 | 64 | 74 |

| nlp-10 | HCON_00073270; maker-scaffold13486-augustus-gene-0.18-mRNA- | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SEMPDDMYIERPVLPLSAGWQE | unmodified | 2562.177 | 90 | 111 |

| nlp-10 | HCON_00073270; maker-scaffold13486-augustus-gene-0.18-mRNA- | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AVMPFSGGLYGKRAVMPFSGGLYG | Gly-loss+Amide | 2403.223 | 114 | 137 |

| nlp-10 | HCON_00073270; maker-scaffold13486-augustus-gene-0.18-mRNA- | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AAMPFSGGLYG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1011.485 | 140 | 150 |

| nlp-10 | HCON_00073270; maker-scaffold13486-augustus-gene-0.18-mRNA- | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | ADRYIRSPMPISGGIFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1777.93 | 153 | 169 |

| nlp-10 | HCON_00073270; maker-scaffold13486-augustus-gene-0.18-mRNA- | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SPMPISGGIFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1003.516 | 159 | 169 |

| nlp-11 | HCON_00062360; augustus-C472037-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | LETELHPLVMGMYGFGPENNAY | unmodified | 2481.135 | 36 | 57 |

| nlp-11 | HCON_00062360; augustus-C472037-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | HISPSFDVEEDVGNMRTLMDIG | Gly-loss+Amide | 2403.12 | 67 | 88 |

| nlp-11 | HCON_00062360; augustus-C472037-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | QLSVADDVGRQMQMYHRLFEAG | Gly-loss+Amide | 2492.205 | 91 | 112 |

| nlp-11 | HCON_00062360; augustus-C472037-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AALSPSQDLQSAVELSNYLERAG | Gly-loss+Amide | 2360.197 | 116 | 138 |

| nlp-12 | HCON_00021180; maker-scaffold5805-snap-gene-0.2-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | DYRPLQFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 936.4818 | 31 | 38 |

| nlp-12 | HCON_00021180; maker-scaffold5805-snap-gene-0.2-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | DGYRPLQFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 993.5032 | 41 | 49 |

| nlp-12 | HCON_00021180; maker-scaffold5805-snap-gene-0.2-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SPLASAFLVPAL | unmodified | 1184.681 | 62 | 73 |

| nlp-13 | HCON_00136950; maker-C471727-snap-gene-0.19-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | NDFSRDIMHFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1279.577 | 33 | 43 |

| nlp-13 | HCON_00136950; maker-C471727-snap-gene-0.19-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AYGNGRLVAYGGPAFERDMMAFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 2391.125 | 46 | 68 |

| nlp-13 | HCON_00136950; maker-C471727-snap-gene-0.19-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SGGFEREMMSFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1275.538 | 71 | 82 |

| nlp-13 | HCON_00136950 | PRJEB506 | SPFEREFLSFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1256.61E | 85 | 95 |

| nlp-13 | HCON_00136950; maker-C471727-snap-gene-0.19-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GSEFDREMLSFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1315.587 | 98 | 109 |

| nlp-13 | HCON_00136950; maker-C471727-snap-gene-0.19-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | DEFERSMMAFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1260.527 | 112 | 122 |

| nlp-14 | HCON_00190000; maker-scaffold4554-snap-gene-0.8-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | ALDSLEGDGFGGLF | unmodified | 1396.651 | 52 | 65 |

| nlp-14 | HCON_00190000; maker-scaffold4554-snap-gene-0.8-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SLDSLEGDGFGFD | unmodified | 1357.567 | 68 | 80 |

| nlp-14 | HCON_00190000; maker-scaffold4554-snap-gene-0.8-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | ALNALDGTGFGFD | unmodified | 1296.599 | 83 | 95 |

| nlp-14 | HCON_00190000; maker-scaffold4554-snap-gene-0.8-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | ALNSLEGTGFGFD | unmodified | 1326.609 | 98 | 110 |

| nlp-14 | HCON_00190000; maker-scaffold4554-snap-gene-0.8-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SLNSIEGTGFGFD | unmodified | 1342.604 | 113 | 125 |

| nlp-14 | HCON_00190000; maker-scaffold4554-snap-gene-0.8-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SLDSTEGTGFGYRRG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1543.738 | 160 | 174 |

| nlp-14 | HCON_00190000; maker-scaffold4554-snap-gene-0.8-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | TLPQITGTHPYLRLY | unmodified | 1771.962 | 177 | 191 |

| nlp-15 | HCON_00024600; maker-C472057-snap-gene-0.5-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AFDSLSGSGLTPFN | unmodified | 1411.662 | 47 | 60 |

| nlp-15 | HCON_00024600; maker-C472057-snap-gene-0.5-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AFDSLAGSGFTGFD | unmodified | 1390.604 | 79 | 92 |

| nlp-15 | HCON_00024600 | PRJEB506 | SPIALNGGYYQPLREDALLL | unmodified | 2202.169 | 95 | 114 |

| nlp-17 | HCON_00114940 | PRJEB506 | NSLSN MMRLG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1063.527 | 44 | 49 |

| nlp-17 | HCON_00114940 | PRJEB506 | VDALKEQEPCVDCSLGNLMRLG | 2 Cys-Cys; Gly-loss+ | 2329.123 | 52 | 73 |

| nlp-18 | HCON_00035340; augustus-scaffold7830-abinit-gene-0.1-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SDEVVEDDGELE | unmodified | 1334.536 | 52 | 63 |

| nlp-18 | HCON_00035340; augustus-scaffold7830-abinit-gene-0.1-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SPYRQFAFA | unmodified | 1085.529 | 74 | 82 |

| nlp-18 | HCON_00035340 | PRJEB506 | GSPYGFAFA | unmodified | 915.4127 | 85 | 93 |

| nlp-19c | HCOI00354200 | PRJEB506.WBPS10 | IGMRLPNIIYM | unmodified | 1319.709 | 52 | 62 |

| nlp-20 | HCON_00131138 | PRJEB506 | DLDNSKKFSFA | unmodified | 1270.619 | 64 | 74 |

| nlp-20 | HCON_00131138 | PRJEB506 | FADRDDRLIR | unmodified | 1275.668 | 105 | 114 |

| nlp-21 | HCON_00067330; maker-C471673-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GGGRAFVPIEE | unmodified | 1130.572 | 27 | 37 |

| nlp-21 | HCON_00067330; maker-C471673-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GGARAFFGDE | unmodified | 1025.457 | 39 | 48 |

| nlp-21 | HCON_00067330; maker-C471673-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GGARAFVVDT | unmodified | 991.5087 | 51 | 60 |

| nlp-21 | HCON_00067330; maker-C471673-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GGGRAFLPVEE | unmodified | 1130.572 | 73 | 83 |

| nlp-21 | HCON_00067330; maker-C471673-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GGARAFFKDD | unmodified | 1082.515 | 85 | 94 |

| nlp-21 | HCON_00067330; maker-C471673-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GGARAFVPVKEEDEGQSFTDLE | unmodified | 2380.118 | 97 | 118 |

| nlp-21 | HCON_00067330; maker-C471673-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GGARAFFVP | unmodified | 920.4868 | 121 | 129 |

| nlp-21 | HCON_00067330; maker-C471673-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GGARAFFVPK | unmodified | 1048.582 | 121 | 130 |

| nlp-21 | HCON_00067330; maker-C471673-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GGGRAFLPIEE | unmodified | 1144.588 | 132 | 142 |

| nlp-21 | HCON_00067330; maker-C471673-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GGARAFFQEP | unmodified | 1078.52 | 144 | 153 |

| nlp-21 | HCON_00067330; maker-C471673-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GGARAFP | unmodified | 674.35 | 156 | 162 |

| nlp-21 | HCON_00067330; maker-C471673-augustus-gene-0.17-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GGGRAFVPQ | unmodified | 887.4614 | 165 | 173 |

| nlp-24 | HCON_00126360 | PRJEB506 | VNPLQGAMMGAMMGAMRG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1763.813 | 66 | 83 |

| nlp-31 | HCON_00105250 | PRJEB506 | PVVVERTIIYPG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1283.76 | 68 | 79 |

| nlp-35c | HCOI00356900; snap-scaffold16547-abinit-gene-0.6-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506.WBPS10; PRJNA205202 | DQLAFSGQNAYLRQLLQN LKPK | unmodified | 2544.381 | 46 | 67 |

| nlp-37 | HCON_00163850 | PRJEB506 | NNAEVVNHILKNFGTLDRLGDVG | Gly-loss+Amide | 2436.287 | 60 | 83 |

| nlp-40 | HCON_00017810.1; maker-C461709-augustus-gene-0.1-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | QLTAPTTMEKEEA | Gln->pyro-Glu | 1430.66 | 41 | 53 |

| nlp-40 | HCON_00017810.1; maker-C461709-augustus-gene-0.1-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | MVAWQPM | unmodified | 861.3877 | 67 | 73 |

| nlp-42 | HCON_00142640 | PRJEB506 | SAVGELSYPRRFL | unmodified | 1493.799 | 36 | 48 |

| nlp-42c | HCOI01162100 | PRJEB506.WBPS10 | SVDWHSLGWAWG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1341.626 | 57 | 68 |

| nlp-44 | HCON_00163905 | PRJEB506 | STLPLSSLLVPYPRVG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1639.966 | 34 | 49 |

| nlp-44 | HCON_00163905 | PRJEB506 | SFFTGDRNVYPPTSI | unmodified | 1699.821 | 52 | 66 |

| nlp-44 | HCON_00163905 | PRJEB506 | RYLYTARVG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1039.593 | 79 | 87 |

| nlp-54 | HCON_00096380 | PRJEB506 | GNM WGTPSKSYGYTN LA E | unmodified | 1974.878 | 43 | 60 |

| nlp-58 | HCON_00137190 | PRJEB506 | SLYGVDDGFTFKGFRGL | unmodified | 1877.931 | 41 | 57 |

| nlp-58 | HCON_00163905 | PRJEB506 | MPYMNLKGLRG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1220.652 | 62 | 72 |

| nlp-59 | HCON_00096380; maker-scaffold14296-augustus-gene-0.22-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | FEGLADYVALEDPNA | unmodified | 1622.746 | 63 | 77 |

| nlp-59 | HCON_00096380; maker-scaffold14296-augustus-gene-0.22-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | LAILSARGFG | Gly-loss+Amide | 945.576 | 85 | 94 |

| nlp-67 | HCON_00186320; maker-scaffold993-snap-gene-0.2-mRNA- | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | AVPVEVEQRE | unmodified | 1154.593 | 54 | 63 |

| nlp-67 | HCON_00186320; maker-scaffold993-snap-gene-0.2-mRNA- | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SYPRNCYFSPIQCLFT | 2 Cys-Cys | 1935.865 | 71 | 86 |

| nlp-68 | HCON_00070810; augustus-scaffold17454-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | LVREPPLI | unmodified | 935.5804 | 50 | 57 |

| nlp-68 | HCON_00070810; augustus-scaffold17454-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | GIDPFSIPTLIKEPPL | unmodified | 1735.976 | 60 | 75 |

| nlp-68 | HCON_00070810; augustus-scaffold17454-abinit-gene-0.0-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | DSYVYPSTNSQLSDRIPLREPPL | unmodified | 2646.329 | 82 | 104 |

| nlp-69c | HCOI01768700 | PRJEB506.WBPS10 | FYRTGGTILLG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1138.65 | 58 | 68 |

| nlp-71 | HCON_00122860 | PRJEB506 | ALNQFKNCYFSPIQCVLME | 2 Cys-Cys | 2245.037 | 62 | 80 |

| nlp-74 | HCON_00082180; maker-scaffold4879-augustus-gene-0.4-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA20222 | APQMYDDVQFV | unmodified | 1311.581 | 28 | 38 |

| nlp-74 | HCON_00082180; maker-scaffold4879-augustus-gene-0.4-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SNAELINGLIGMDLGKLSAVG | Gly-loss+Amide | 2013.093 | 41 | 61 |

| nlp-74 | HCON_00082180; maker-scaffold4879-augustus-gene-0.4-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | SNAELINGLLGMNLNKLSSAG | Gly-loss+Amide | 2057.094 | 64 | 84 |

| nlp-81 | HCON_00107730 | PRJEB506 | FTNGDFFVP | unmodified | 1101.524 | 48 | 56 |

| nlp-81 | HCON_00107730 | PRJEB506 | WIPSGGAGLVSGRG | unmodified | 1312.689 | 60 | 73 |

| nlp-81 | HCON_00107730 | PRJEB506 | DWRSAIAEPNF | unmodified | 1304.615 | 83 | 93 |

| HCON_00135420 | HCON_00135420; maker-scaffold6512-augustus-gene-0.7-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | ARNPYSWMVVDQS | unmodified | 1551.714 | 45 | 57 |

| HCON_00135420 | HCON_00135420; maker-scaffold6512-augustus-gene-0.7-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506 | SRNPYSWMVHSKG | Gly-loss+Amide | 1489.725 | 60 | 72 |

| HCON 00135420 | HCON_00135420; maker-scaffold6512-augustus-gene-0.7-mRNA-1 | PRJEB506; PRJNA205202 | ARNPYSWMNE | unmodified | 1266.545 | 101 | 110 |

The precursor name corresponds either to the one reported in project PRJEB506 or to the one reported in project PRJNA205202 on the WormBase site.

When sequences are predicted by both databases, the peptide sequence start and end positions refer to the database indicated first.

Denotes identified sequences from the PRJEB506 release (versions to 10).

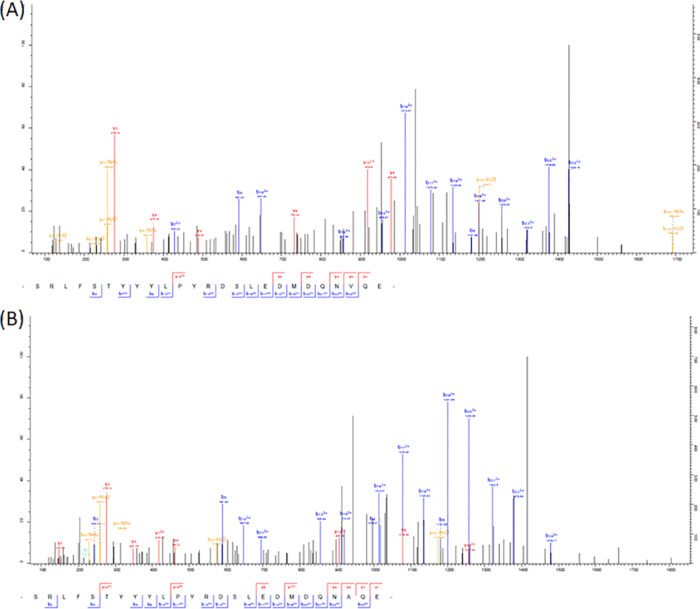

As seen for FLP peptides, the use of the two WormBase data sets (PRJEB506 versions 10 and 14, and PRJNA205202) yielded an increase in the number of identified NLP peptides and allowed us to inform the predicted sequences where discrepancies existed between databases, as shown for nlp-5, nlp-7, nlp-15, nlp-9, nlp-13, and nlp-18 (Table 4; Figure S2). Detection of the peptide GGGRAFFGGWQPYESLGARMD encoded on nlp-9 shows that the correct sequence was the one predicted in PRJNA205202, whereas for nlp-7, nlp-13, nlp-15, nlp-18, and one peptide of nlp-5, the correct sequences were predicted in PRJEB506. More surprising was the fact that we clearly identified both of the WormBase predicted sequences for the C-terminal peptide of nlp-5 (SRLFSTYYYLPYRDSLEDMDQNAQE, predicted in PRJNA205202, and SRLFSTYYYLPYRDSLEDMDQNVQE, predicted in PRJEB506); the corresponding MS/MS spectra are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

MS/MS spectra of two peptides of the H. contortus neuropeptide precursor encoded by nlp-5. The fragmentation schemes allowed the identification of the peptide SRLFSTYYYLPYRDSLEDMDQNVQE from the WormBase PRJEB506 data set analysis (A) and of the peptide SRLFSTYYYLPYRDSLEDMDQNAQE from analysis of the WormBase PRJNA205202 data set (B).

All H. contortus NLP sequences revealed in this study were aligned with their C. elegans homologues as shown in Figure S2. As reported for C. elegans,28,29 we also detected equivalent unrecorded H. contortus neuropeptides for nlp-3, nlp-9, nlp-10, and nlp-12 (these peptides are underlined in Figure S2). As already shown for FLP peptides, these alignments emphasize the similarity in neuropeptide sequences between both C. elegans and H. contortus with the identification of peptides bearing the C-terminal glycine residue for amidation and with peptides not modified but being flanked by di- or mono-basic residues. In this study, we were able to isolate and identify peptides arising from nlp-17, nlp-19, nlp-44, nlp-54, nlp-59, nlp-67, nlp-38, nlp-69, and nlp-71 that were not previously reported in similar studies on C. elegans. Of particular interest are the C-terminal peptides of nlp-17, nlp-67, and nlp-71, which were unambiguously identified with one disulfide bridge, as shown by their MS/MS spectra (Figure 5). The study on C. elegans(28,29) reported the homologous sequences with the prediction of disulfide bridges, but there was no biochemical isolation or characterization.

Figure 5.

MS/MS spectra of the C-terminal peptides of nlp-17 (A), nlp-67 (B), and nlp-71 (C) of H. contortus. The fragmentation schemes allow the unambiguous identification of the presence of a disulfide bridge between two cysteine residues for the three peptides.

Label-Free Quantification of Neuropeptides

Neuropeptide quantification was performed on four L1 and three L3 biological replicates. Normalized intensities measured for all identified peptides arising from predicted neuropeptide precursors are listed in Table S2.

Relative Abundance of Endogenous Peptides

Some of the detected peptides are shorter versions of the same peptide, likely reflecting the degradation of bioactive peptides during sample processing. We calculated the intensities of truncated forms and compared these to the intensity of the corresponding nontruncated bioactive peptides. On average, we found that these degraded forms represented less than 15% of the entire form, indicative of a low level of peptide degradation. It is noteworthy that for most amidated peptides, we also detected two other minor forms, representing less than 5% of the mature peptide, one corresponding to the nonamidated peptide and the second one corresponding to the substrate of the amidating enzymes, which act sequentially on C-terminal Glycine-extended immature peptides (Table S2).

The relative abundance of all endogenous peptides reported in Tables 2 and 4 is shown in Figure 7, spanning four orders of magnitude both in the L1 and L3 life stages. Among the 181 detected bioactive peptides, the most intense flp and nlp peptides quantified are indicated in Figure 6.

Figure 7.

Volcano plot showing peptides differentially expressed between L1 larvae and L3 larvae of H. contortus. The x-axis represents the log2 fold-change (FC) of L3 versus L1. The y-axis represents the p-value from a t test applied between four L1 biological replicates and three L3 biological replicates. All data are shown in Table S2. Peptides with FC < −3 and p-value <0.01, statistically more expressed in L1 stage, are highlighted in green and peptides with FC > 3 and p-value <0.01, statistically more expressed in L3 stage, are highlighted in red. For the purpose of clarity, peptides are only annotated by the precursor name.

Figure 6.

Relative abundance of flp-encoded (highlighted in blue) and nlp-encoded peptides (highlighted in red) in the L1 larvae stage (A) and L3 larvae stage (B) of H. contortus. The most intense peptides identified are indicated.

Differential Neuropeptide Expression between L1 Stage and L3 Stage Larvae of H. contortus

We compared the relative peptide expression in L1 (free-living stage) and L3 (infective) life stages for the 181 identified mature peptides (Table S3). All resulting individual boxplots are depicted in Figure S3. Based on an arbitrary fold-change of 3 and a p-value of 0.01, we found 29 peptides more highly expressed in L3s and 22 more highly expressed in L1s (Figure 7).

Data shown in Table S2 and Figure S3 highlight that peptides arising from the same precursor can either follow the same trend or vary greatly in expression between L1 and L3 worms. For example, all four nlp-3 peptides (AINPFLDSMG, AVNPFLDSFG, SSRYQPYYHLD, and YFDSLAGQALG) are more highly expressed in L3s (Figure 8A), whereas nlp-10 has two peptides (AVMPFSGGLYG and ADRYIRSMPISGGIFG) that show opposite trends in the two life stages, being lower in the L3 stage worms (Figure 8B).

Figure 8.

Relative label-free quantification of four nlp-3 encoded peptides (A) and of two nlp-10 encoded peptides (B) between the first-stage (L1) and third-stage larvae (L3) of H. contortus. The boxplots were obtained from four L1 biological replicates and from three L3 biological replicates. The zone below the inferior red line (value of 16.6) indicates very low or no expression. The zone between the two red lines corresponds to a low expression zone.

Discussion

The present study is the first whole-parasitic peptidome analysis of H. contortus. Previously, only two FLP neuropeptides have been directly sequenced for this nematode.31,32 These new findings enhance the understanding of nematode neuropeptide biology and enhance the FLP-activated G-protein coupler receptors profiling described in McCoy et al.14

This is also one of the most comprehensive neuropeptidome analyses of a nematode with a total of 181 peptides (68 FLPs and 113 NLPs) being identified biochemically using MS/MS. It can be compared with similar studies performed on C. elegans, which led to the identification of 203 neuropeptides based on mass matching,28,29 131 among them with sequenced levels using LC-MS/MS. In our study, all of the identified peptides were fully sequenced by MS/MS. However, five predicted FLP and nine NLP precursors remain undetected in this study. This can be due to various reasons. At first, it is not possible to anticipate which predicted peptides will be expressed and correctly processed into bioactive peptides. Another possibility is that some neuropeptides may be present in other developmental stages or may be expressed under certain conditions. In addition, we cannot exclude experimental bias like neuropeptide degradation during sample processing, leading to low-molecular-weight peptides not detectable by LC/MS. The stochastic precursor selection of DDA may also lead to inconsistent detection of peptides, and finally, some neuropeptides are certainly below the current detection threshold of MS due to their weak expression.

The results obtained from H. contortus larvae peptidomics profiling reveal and expand on the known complexity of neuropeptide expression in nematodes. These data are consistent with nematode parasites, displaying remarkable neuropeptide complexity despite their apparent nervous system simplicity.37 The data further confirm that peptide-based neuronal signaling in parasitic nematodes is similarly complex to that reported for free-living nematodes, at least in these clade V nematodes. This is not surprising considering that H. contortus has both free-living and parasitic stages and the L3 stage transitions from the free-living to a host-based environment.

In this study, the differentially expressed neuropeptides between two key developmental stages of H. contortus (the first-larval stage, L1, and the infective stage, L3) were investigated by comparative peptidomics. The free-living stage L1 is motile and exits the egg to feed on feces, while the L3 stage waits in water droplets on vegetation and enters a resting stage that relies on reserves, slows its metabolic rate, and stops actively feeding, prior to being ingested by the ruminant host. Despite these dramatic differences in life stage behaviors, which have been reflected previously through transcriptomic studies showing significant differences in protein-coding gene expression,34,38 both life stages appear here to express mostly similar FLP and NLP neuropeptides. Among the 181 quantified peptides in this study, 170 were detected in the L1 stage and 171 in the L3 stage. This is consistent with the fact that many of these neuropeptides, especially the FLPs, regulate diverse behaviors through the modulation of sensory and motor functions.

It appears that genes expressed in both life stages are overall upregulated in the L3 phase, with only peptides encoded on flp-2, flp-9, nlp-1, and nlp-7 being upregulated in the L1 stages. These changes in expression could be associated with the maturation of the nervous motor system observed in L3. It is also possible that the peptides upregulated in the L1s associate with feeding behaviors that differ dramatically between the L1 and L3 life stages. More interesting is that for some genes, individual peptides are differentially expressed in one of the life stages compared to the other, e.g., nlp-10, nlp-21, nlp-40, and nlp-81. These data are intriguing and suggest that nematodes can differentially regulate the levels of individual peptides from the same precursor protein. This could be done through more rapid degradation of some component peptides compared to others, which further demonstrates the complexity inherent in nematode neuropeptide signaling.

Furthermore, the ability to quantify neuropeptides between different samples allows the comparison of peptide profiles. For example, this quantitative strategy allowed the differential analysis of peptide amidation profiles and represents an efficient approach to the characterization of key neuropeptide processing enzymes of the neuropeptide processing pathway or, in the context of drug discovery, could inform target engagement and the efficacy of inhibitors or modulators of the neuropeptide signaling pathways or their processing enzymes. This repository of biochemically identified and quantified peptide sequences provides a unique resource to enable the discovery of compounds active at different developmental stages of the nematode.

In conclusion, the extensive neuropeptide database provided here is a first step toward the understanding of the fundamental biochemistry of H. contortus and can be exploited in further experimental studies aiming at developing new anthelmintics against H. contortus.

Methods

Parasite Collection

All H. contortus samples (L1 and L3 stages) were obtained from Boehringer Ingelheim Animal Health. Worms were pelleted (12 min, 1800g), resuspended in deionized water, and washed several times with water. At the end of the final wash, worms were resuspended in 30 μL of PBS prior to storage at −80 °C. The L1 samples had a similar biomass to the L3 stage samples, i.e., approximately 45 000 L1 and 20 000 L3 in a volume of 20 μL PBS.

Peptide Extraction and Purification

To extract the peptides, 150 μL of an acidic methanol (methanol/water/acetic acid (90/9/1)) solution was added to the larvae. The mixture was then stirred for 30 min at 4 °C, followed by a 10 s sonication step for L3 larvae. Samples were then centrifuged for 15 min at 10 000g at 4 °C. Supernatants were collected and concentrated under vacuum (Concentrator 5301, Eppendorf (SpeedVac)) to obtain a volume of approximately 10 μL. The peptides were purified and desalted using C18 columns (OMIX C18 pipette tips, Millipore, Molsheim, France) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, peptides were concentrated in vacuum and reconstituted in 0.2% formic acid for injection in LC-MS/MS.

Nano-HPLC/Nano-ESI Orbitrap-MS/MS

LC-MS/MS analyses were performed using a liquid chromatograph (LC) coupled to an Orbitrap Fusion Tribrid mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, San Jose, CA) using a Nano-spray Flex NG source. Reversed-phase chromatography was performed with a nano-ACQUITY Ultra-Performance LC system (Waters, Milford, MA) fitted with a trapping column (nano-Acquity Symmetry C18, 100 Å, 5 μm, 180 μm × 20 mm) at a 15 μL/min flow rate and an analytical column (nano-Acquity BEH C18, 130 Å, 1.7 μm, 75 μm × 250 mm) directly coupled to the ion source. The mobile phases for LC separation were 0.2% (v/v) formic acid in LC-MS grade water (solvent A) and 0.2% (v/v) formic acid in acetonitrile (solvent B). Peptides were separated at a 300 nL/min constant flow rate with a linear gradient of 5–85% solvent B for 85 min. A full MS1 survey scan was acquired with the Orbitrap for m/z 325–1200 at a 50 ms maximum filling time and 2 × 105 ions. The resolution was set to 120 000 at m/z 200. For MS/MS experiments, fragmentation was performed in HCD fragmentation cell (collision energy at 26%), with isolation of precursor ions in a quadrupole. Target ions previously selected for fragmentation were dynamically excluded for 50 s with a relative mass window of ±10 ppm. The MS/MS selection threshold was set to 5 × 103 ion counts. The detection was performed in an Ion Trap with an Automatic Gain Control (AGC) of 2 × 104 target value and a 50 ms maximum injection time. Each sample was injected twice (technical replicate).

Data Processing

Identification and quantification of peptides were performed using MaxQuant software (Ver. 1.5.3.8, Max-Planck Institute of Biochemistry, Department of Proteomics and Signal Transduction, Munich). Database searching was performed against the FASTA databases downloaded from the WormBase site (https://wormbase.org) (BioProject PRJNA205202 and BioProject PRJEB506). Interrogation of the databanks was based on the following criteria: precursor mass tolerance of 7 ppm, fragment ions mass tolerance of 0.6 Da, and 2 maximum missed cleavages with semi-trypsin as the enzyme. Search parameters for post-translational modifications were variable modifications of oxidation on methionine residues, N-terminal cyclization of glutamine/glutamic acid to pyroglutamate, disulfide bridge on cysteine residues, and glycine loss in combination with amidation (Gly-loss+Amide (C-term G)). The match between runs was performed with a match time window set to 0.7 min and an alignment time window set to 20 min. A false discovery rate of 1% was required for peptides with a minimum Andromeda score for accepting an MS/MS identification for modified peptides set to 40. All of the other parameters were MaxQuant default parameters. Peptides were retained as putative neuropeptides if they were surrounded by (di)basic residues and were kept only if their Andromeda score was higher than 60 or after manual inspection of their MS/MS spectra.

Differential Statistical Analysis

Peptide intensities were exported from the MaxQuant modificationSpecificPeptides file. Missing values were replaced by the minimum value of each acquisition. Intensities were transformed into their log2 values. Medians were calculated over the technical replicates. Data normalization was performed on the set of all identified and quantified peptides. The normalization coefficients thus obtained were applied to the initial intensities of all of the peptides detected. A two-tailed t test for each peptide was performed on the normalized medians to determine the statistical significance between L1 and L3 sample groups, assuming equal variance.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Veeranagouda Yaligara, Michel Didier, Jean-Luc Zachayus, and Anne Remaury for technical advice.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- FLPs

FMRFamide-like peptides

- NLPs

neuropeptide-like proteins

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- FDR

false discovery rate

- FC

fold-change

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c00650.

Sequence alignments of H. contortus FLP precursors predicted from the WormBase PRJNA205202 project and from the WormBase PRJEB506 with its homologs in C. elegans, UniProtKB source (Figure S1); sequence alignments of H. contortus NLP precursors predicted from the PRJNA205202 and from the PRJEB506.WBPS14 WormBase projects with their homologs in C. elegans, UniProtKB source (Figure S2); relative label-free quantification of FLP and NLP peptides between the first-stage (L1) and third-stage larvae (L3) of H. contortus (Figure S3); homemade database Fasta file (Supplementary Data 1) (PDF)

Blast analysis of C. elegans NLP precursors reported by Van Bael et al.,29 against H. contortus WormBase PRJEB506 and PRJNA205202 databases (Table S1); expressions of all FLP and NLP peptides in the L1 larvae stage and L3 larvae stage of H. contortus (Table S2); expressions of mature FLP and NLP peptides in the L1 larvae stage and L3 larvae stage of H. contortus (Table S3) (XLSX)

Author Contributions

A.B. wrote the paper with input from all other authors. A.B. and C.A. designed the experiments. J.-C.G. supervised the development of the whole analytical workflow. D.F.B. prepared the parasite samples for peptide extraction. C.A. performed the peptide extraction, the LC-MS/MS analysis, and the Database Searching. A.B. processed the data.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Besier R. B.; Kahn L. P.; Sargison N. D.; Van Wyk J. A. The Pathophysiology, Ecology and Epidemiology of Haemonchus contortus Infection in Small Ruminants. Adv. Parasitol. 2016, 93, 95–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasser R. B.; von Samson-Himmelstjerna G. Haemonchus contortus and haemonchosis– past, present and future trends. Adv. Parasitol. 2016, 93, 1–666.27238001 [Google Scholar]

- Veglia E. The anatomy and life history of the Haemonchus contortus. Rep. Dir. Vet. Res. 1915, 3–4, 347–500. [Google Scholar]

- Brown L. A.; Jones A. K.; Buckingham S. D.; Mee C. J.; Sattelle D. B. Contributions from Caenorhabditis elegans functional genetics to antiparasitic drug target identification and validation: nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, a case study. Int. J. Parasitol. 2006, 36, 617–624. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R. J.; Robertson A. P. Control of Nematode Parasites with Agents Acting on Neuro-Musculature Systems: Lessons for Neuropeptide Ligand Discovery. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 692, 138–154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousley A.; Marks N. J.; Halton D. W.; Geary T. G.; Thompson D. P.; Maule A. G. Arthropod FMRFamide-related peptides modulate muscle activity in helminths. Int. J. Parasitol. 2004, 34, 755–768. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2004.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotze A. C.; Prichard R. K. Anthelmintic Resistance in Haemonchus contortus: History, Mechanisms and Diagnosis. Adv. Parasitol. 2016, 93, 397–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maule A. G.; Mousley A.; Marks N. J.; Day T. A.; Thompson D. P.; Geary T. G.; Halton D. W. Neuropeptide signaling systems - potential drug targets for parasite and pest control. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2002, 2, 733–758. 10.2174/1568026023393697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousley A.; Polese G.; Marks N. J.; Eisthen H. L. Terminal nerve-derived neuropeptide y modulates physiological responses in the olfactory epithelium of hungry axolotls (Ambystoma mexicanum). J. Neurosci. 2006, 26, 7707–7717. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1977-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mousley A.; Novozhilova E.; Kimber M. J.; Day T. A.; Maule A. G. Neuropeptide physiology in helminths. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2010, 692, 78–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVeigh P.; Atkinson L.; Marks N. J.; Mousley A.; Dalzell J. J.; Sluder A.; Hammerland L.; Maule A. G. Parasite neuropeptide biology: Seeding rational drug target selection?. Int. J. Parasitol.: Drugs Drug Resist. 2012, 2, 76–91. 10.1016/j.ijpddr.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVeigh P.; Geary T. G.; Marks N. J.; Maule A. G. The FLP-side of nematodes. Trends Parasitol. 2006, 22, 385–396. 10.1016/j.pt.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.; Nelson L. S.; Kim K.; Nathoo A.; Hart A. C. Neuropeptide gene families in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1999, 897, 239–252. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb07895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy C. J.; Atkinson L. E.; Zamanian M.; McVeigh P.; Day T. A.; Kimber M. J.; Marks N. J.; Maule A. G.; Mousley A. New insights into the FLPergic complements of parasitic nematodes: Informing deorphanisation approaches. EuPa Open Proteomics 2014, 3, 262–272. 10.1016/j.euprot.2014.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peymen K.; Watteyne J.; Frooninckx L.; Schoofs L.; Beets I. The FMRFamide-Like Peptide Family in Nematodes. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 90. 10.3389/fendo.2014.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gahoi S.; Gautam B. Identification and analysis of insulin like peptides in nematode secretomes provide targets for parasite control. Bioinformation 2016, 12, 412–415. 10.6026/97320630012412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price D. A.; Greenberg M. J. Structure of a molluscan cardioexcitatory neuropeptide. Science 1977, 197, 670–671. 10.1126/science.877582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVeigh P.; Alexander-Bowman S.; Veal E.; Mousley A.; Marks N. J.; Maule A. G. Neuropeptide-like protein diversity in phylum Nematoda. Int. J. Parasitol. 2008, 38, 1493–1503. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathoo A. N.; Moeller R. A.; Westlund B. A.; Hart A. C. Identification of neuropeptide-like protein gene families in Caenorhabditis elegans and other species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001, 98, 14000–14005. 10.1073/pnas.241231298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.; Kim K. Family of FLP Peptides in Caenorhabditis elegans and Related Nematodes. Front. Endocrinol. 2014, 5, 150. 10.3389/fendo.2014.00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie A. E.; Nolan D. H.; Garcia Z. A.; McCoole M. D.; Harmon S. M.; Congdon-Jones B.; Ohno P.; Hartline N.; Congdon C. B.; Baer K. N.; Lenz P. H. Bioinformatic prediction of arthropod/nematode-like peptides in non-arthropod, non-nematode members of the Ecdysozoa. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 2011, 170, 480–486. 10.1016/j.ygcen.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarecki J. L.; Frey B. L.; Smith L. M.; Stretton A. O. Discovery of neuropeptides in the nematode Ascaris suum by database mining and tandem mass spectrometry. J. Proteome Res. 2011, 10, 3098–3106. 10.1021/pr2001176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koziol U.; Koziol M.; Preza M.; Costabile A.; Brehm K.; Castillo E. De novo discovery of neuropeptides in the genomes of parasitic flatworms using a novel comparative approach. Int. J. Parasitol. 2016, 46, 709–721. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy C. J.; Atkinson L. E.; Robb E.; Marks N. J.; Maule A. G.; Mousley A. Tool-Driven Advances in Neuropeptide Research from a Nematode Parasite Perspective. Trends Parasitol. 2017, 33, 986–1002. 10.1016/j.pt.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards S. L.; Mergan L.; Parmar B.; Cockx B.; De Haes W.; Temmerman L.; Schoofs L. Exploring neuropeptide signalling through proteomics and peptidomics. Expert Rev. Proteomics 2019, 16, 131–137. 10.1080/14789450.2019.1559733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husson S. J.; Clynen E.; Baggerman G.; De Loof A.; Schoofs L. Discovering neuropeptides in Caenorhabditis elegans by two dimensional liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 335, 76–86. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Husson S. J.; Landuyt B.; Nys T.; Baggerman G.; Boonen K.; Clynen E.; Lindemans M.; Janssen T.; Schoofs L. Comparative peptidomics of Caenorhabditis elegans versus C. briggsae by LC-MALDI-TOF MS. Peptides 2009, 30, 449–457. 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bael S.; Edwards S. L.; Husson S. J.; Temmerman L. Identification of Endogenous Neuropeptides in the Nematode C. elegans Using Mass Spectrometry. Methods Mol. Biol. 2018, 1719, 271–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Bael S.; Zels S.; Boonen K.; Beets I.; Schoofs L.; Temmerman L. A Caenorhabditis elegans Mass Spectrometric Resource for Neuropeptidomics. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 2018, 29, 879–889. 10.1007/s13361-017-1856-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yew J. Y.; Dikler S.; Stretton A. O. De novo sequencing of novel neuropeptides directly from Ascaris suum tissue using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight/time-of-flight. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2003, 17, 2693–2698. 10.1002/rcm.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keating C. D.; Holden-Dye L.; Thorndyke M. C.; Williams R. G.; Mallett A.; Walker R. J. The FMRFamide-like neuropeptide AF2 is present in the parasitic nematode Haemonchus contortus. Parasitology 1995, 111, 515–521. 10.1017/S0031182000066026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks N. J.; Sangster N. C.; Maule A. G.; Halton D. W.; Thompson D. P.; Geary T. G.; Shaw C. Structural characterisation and pharmacology of KHEYLRFamide (AF2) and KSAYMRFamide (PF3/AF8) from Haemonchus contortus. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1999, 100, 185–194. 10.1016/S0166-6851(99)00057-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laing R.; Kikuchi T.; Martinelli A.; Tsai I. J.; Beech R. N.; Redman E.; Holroyd N.; Bartley D. J.; Beasley H.; Britton C.; Curran D.; Devaney E.; Gilabert A.; Hunt M.; Jackson F.; Johnston S. L.; Kryukov I.; Li K.; Morrison A. A.; Reid A. J.; Sargison N.; Saunders G. I.; Wasmuth J. D.; Wolstenholme A.; Berriman M.; Gilleard J. S.; Cotton J. A. The genome and transcriptome of Haemonchus contortus, a key model parasite for drug and vaccine discovery. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, R88. 10.1186/gb-2013-14-8-r88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz E. M.; Korhonen P. K.; Campbell B. E.; Young N. D.; Jex A. R.; Jabbar A.; Hall R. S.; Mondal A.; Howe A. C.; Pell J.; Hofmann A.; Boag P. R.; Zhu X. Q.; Gregory T.; Loukas A.; Williams B. A.; Antoshechkin I.; Brown C.; Sternberg P. W.; Gasser R. B. The genome and developmental transcriptome of the strongylid nematode Haemonchus contortus. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, R89. 10.1186/gb-2013-14-8-r89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson L. E.; Miskelly I. R.; Moffett C. L.; McCoy C. J.; Maule A. G.; Marks N. J.; Mousley A. Unraveling flp-11/flp-32 dichotomy in nematodes. Int. J. Parasitol. 2016, 46, 723–736. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.; Kim K.; Nelson L. S. FMRFamide-related neuropeptide gene family in Caenorhabditis elegans. Brain Res. 1999, 848, 26–34. 10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01972-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrushin A.; Ferrara L.; Blau A. The Si elegans project at the interface of experimental and computational Caenorhabditis elegans neurobiology and behavior. J. Neural Eng. 2016, 13, 065001 10.1088/1741-2560/13/6/065001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma G.; Wang T.; Korhonen P. K.; Ang C. S.; Williamson N. A.; Young N. D.; Stroehlein A. J.; Hall R. S.; Koehler A. V.; Hofmann A.; Gasser R. B. Molecular alterations during larval development of Haemonchus contortus in vitro are under tight post-transcriptional control. Int. J. Parasitol. 2018, 48, 763–772. 10.1016/j.ijpara.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.