Abstract

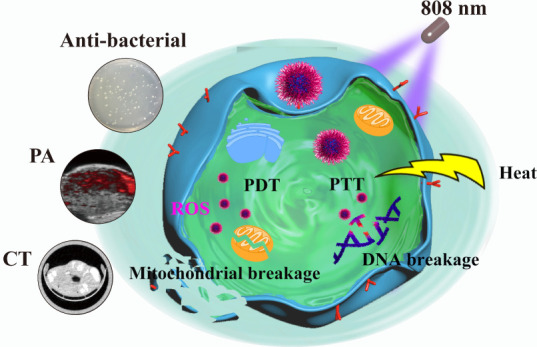

High-efficiency nanotheranostic agents with multimodal imaging guidance have attracted considerable interest in the field of cancer therapy. Herein, novel silver-decorated bismuth-based heterostructured polyvinyl pyrrolidone nanoparticles (NPs) with good biocompatibility (Bi-Ag@PVP NPs) were synthesized for accurate theranostic treatment, which can integrate computed tomography (CT)/photoacoustic (PA) imaging and photodynamic therapy/photothermal therapy (PDT/PTT) into one platform. The Bi-Ag@PVP NPs can enhance light absorption and achieve a better photothermal effect than bismuth NPs. Moreover, after irradiation under an 808 nm laser, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs can efficiently induce the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), thereby synergizing PDT/PTT to exert an efficient tumor ablation effect both in vitro and in vivo. Furthermore, Bi-Ag@PVP NPs can also be employed to perform enhanced CT/PA imaging because of their high X-ray absorption attenuation and enhanced photothermal conversion. Thus, they can be utilized as a highly effective CT/PA imaging-guided nanotheranostic agent. In addition, an excellent antibacterial effect was achieved. After irradiation under an 808 nm laser, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs can destroy the integrity of Escherichia coli, thereby inhibiting E. coli growth, which can minimize the risk of infection during cancer therapy. In conclusion, our study provides a novel nanotheranostic platform that can achieve CT/PA-guided PDT/PTT synergistic therapy and have potential antibacterial properties. Thus, this work provides an effective strategy for further broad clinical application prospects.

1. Introduction

As a highly malignant disease, cancer significantly threatens the health of human beings around the world. Although continuous efforts have been made by researchers to improve cancer treatment, the annual number of deaths from cancer remains high.1−3 Cancer treatment methods mainly include phototherapy, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, surgery, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy.4−11 Among these therapeutic approaches, phototherapy has attracted considerable interest from researchers due to its high specificity, low invasiveness, and negligible side effects.12−16 Phototherapeutic strategies include photodynamic therapy (PDT) and photothermal therapy (PTT). Due to various breakthroughs and its unique advantages, such as negligible invasiveness and spatiotemporal selectivity, PDT has been widely used for cancer therapy.17 PDT relies on photosensitizers. When the laser irradiates the photosensitizer, it can absorb laser energy to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS), which can cause tumor cell damage, necrosis, and apoptosis.18,19 However, traditional photosensitizers, such as chlorin e6 (Ce6) and photofrin, have some drawbacks, including poor photostabilities and visible light irradiation with low tissue penetration. Furthermore, they exhibit relatively insufficient antitumor effects because PDT can aggravate the hypoxic environment inside the tumor, resulting in an insufficient generation of ROS.20 Therefore, the investigation of photosensitizers with more effective antitumor effects, good photostabilities, and the usage of near-infrared (NIR) excitation is of great significance.

As another phototherapy strategy, PTT has attracted broad interest from researchers due to its high selectivity and minimal invasiveness,21 which requires photothermal agents (PTAs) to convert light energy into heat to kill tumor cells. Ideal PTAs can efficiently convert light into heat; thus, good light energy conversion is a prerequisite of PTAs.22 At present, indocyanine green (ICG) is the only PTA approved for clinical use.23 However, the insufficient photothermal conversion efficiency and poor solubility limit its therapeutic effect on malignant tumors. Hence, it is necessary to develop an effective PTA with a high luminous thermal efficiency.

Bismuth nanomaterials with low cost, good biocompatibility, and high atomic numbers have attracted considerable interest and can integrate PDT and PTT, overcoming their drawbacks described above. Recently, the development of nanomaterials with synergistic tumor ablation has attracted considerable interest of researchers. For instance, Zhang et al. have developed pH-responsive Ce6-conjugated gold nanorods (Ce6-PEG-AuNRs), which can achieve fluorescence-guided PTT/PDT ablation of tumors.24 Song et al. synthesized a Bi2Se3@HA-doped PPy/ZnPc nanodish complex using bismuth as a raw material, which could simultaneously exert photothermal and photodynamic effects and had an excellent tumor-growth inhibition ratio (96.4%).25 Liu et al. reported a novel Bi-based nanocomposite (UCNP@NBOF-FePc-PFA) that could not only enable the upconversion luminescence/CT bioimaging of living beings but also be applied for photothermal/photodynamic/radio synergistic tumor ablation.26 These materials have great antitumor effects and potential applications in biomedicine. However, there have been few investigations on high-content bismuth nanomaterials. It is worthwhile to develop biomedical theranostic applications of high-content bismuth nanomaterials. As is well known, the decoration of engineering structures can improve their photonic absorption properties; thus, the engineering decoration of nanomaterials is significant for enhancing photonic properties.

Herein, silver-decorated bismuth-based heterostructured polyvinyl pyrrolidone nanoparticles (Bi-Ag@PVP NPs) with nanoheterostructures were facilely synthesized via a two-step method. After modification of PVP, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs possessed low cytotoxicity and caused little damage to normal organs. Notably, under 808 nm laser irradiation, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs exhibited a better photothermal effect than single bismuth NPs (Bi@PVP NPs) in vivo and in vitro. Importantly, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs could employ NIR to generate ROS, thereby synergizing PDT and PTT to ablate tumor cells, achieving an enhanced therapeutic effect. Meanwhile, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs also possessed computed tomography (CT) and photoacoustic (PA) dual-modal imaging properties, enhancing the CT and PA contrast of tumor sites. Interestingly, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs could be effectively used to kill Escherichia coli, indicating that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs had an excellent antibacterial function and could be used to avoid bacterial infections during cancer therapy. In brief, the multifunctional Bi-Ag@PVP NPs could achieve an accurate theranostic effect; thus, they have a bright future in cancer therapy.

2. Experimental

2.1. Fabrication of Bi@PVP NPs

First, 1 mmol of Bi(NO3)3·5H2O was dispersed in 10 mL of HNO3 (1 M); then, the solution was added to 50 mL of ethylene glycol containing 0.8 g of PVP (Mw = 10000) and 0.2 g of NaOH. After vigorous mixing and ultrasonic treatment for 10 min, the reaction system was transferred to a 100 mL reaction vessel and heated for 3 h at 150 °C. When the reaction system cooled to room temperature, the samples were collected by centrifugation (8000 rpm, 5 min), washed with double distilled water (ddH2O) and alcohol to remove the residue, and finally frozen and dried to obtain Bi@PVP NPs.

2.2. Synthesis of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs

First, 25 mg of the above-synthesized Bi@PVP NPs was scattered in 20 mL of ddH2O. Subsequently, 5 mL of bovine serum album (BSA) solution (4 mg/mL) and 5 mL of AgNO3 (4 mg/mL) were slowly added to the above ddH2O solution. After stirring for 10 min at room temperature, 10 mL of NaOH solution (pH = 12) was slowly added into the ddH2O solution and stirred for 12 h at 37 °C. Finally, the solution was centrifuged to remove the unreacted sediments from the ddH2O and alcohol. After drying in an oven at a temperature of 65 °C, the final Bi-Ag@PVP NPs were obtained.

2.3. Characterization

The morphologies and particle sizes of the Bi-Ag@PVP and Bi@PVP NPs were observed and measured by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was also employed to observe the morphologies of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. The compositions of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs were determined by energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS) during the TEM, including mapping analysis. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was utilized to evaluate the surface properties of the products. The phase features of the Bi-Ag@PVP and Bi@PVP NPs were investigated by powder X-ray diffraction (XRD). The optical absorption spectra of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs and Bi@PVP NPs were obtained using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (South East Chemicals & Instruments Ltd, China). Finally, dynamic light scattering (DLS) was used to analyze the size distribution of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH = 7.4), acidic PBS (pH = 6.8), serum, and 1640 medium.

2.4. Animal Model

Female BALB/c nude mice were purchased from the Xiamen University Laboratory Animal Center (Xiamen, China). HepG2 cells (1.0 × 107/mL) were subcutaneously injected into the right hind legs of the mice to induce tumor formation. All animal experiments were performed according to the protocol approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Xiamen University.

2.5. Photothermal Effect of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs In Vitro and In Vivo

Various concentrations (0.5, 1, and 2 mg/mL) of Bi-Ag@PVP and Bi@PVP NP suspensions and PBS solution were prepared and irradiated under an 808 nm laser (2 W/cm2) for 5 min. The infrared thermal imager (Joint Vision Technology Company Ltd, Ax5, China) was used to record the temperature changes every 10 s. Then, the photostability of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs was studied. First, 500 μg/mL of the Bi-Ag@PVP NP suspension was irradiated with an 808 nm laser (2 W/cm2). When the temperature reached the peak, the power was turned off and then the suspension was naturally cooled for three cycles. The temperature changes were recorded with the infrared thermal imager, as described above. To study the photothermal effect in vivo, the Bi-Ag@PVP and Bi@PVP NP suspensions (1 mg/mL, 100 μL) and the PBS solution were intratumorally injected. After anesthesia, the mice were irradiated with an 808 nm laser (2 W/cm2), and the corresponding temperature changes and infrared thermal images were recorded and captured.

2.6. Intracellular ROS Detection

The HepG2 cells were cocultured with or without 400 μg/mL of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs for 24 h. The HepG2 cells were cultured without Bi-Ag@PVP NPs as the control group. The remaining groups were irradiated with or without NIR (2 W/cm2, 5 min). A 2′-7′dichlorofluorescin diacetate (DCFH-DA) probe (Yeasen, China) was subsequently diluted with a serum-free medium (1:1000) and cocultured with the cells for 30 min. The HepG2 cells were then fixed with paraformaldehyde fixative for 10 min, and the nuclei were stained with Hoechst (Yeasen, China). Finally, the cells were observed via confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM, Nikon A1R, Japan).

2.7. Cytotoxicity Evaluation

The cytotoxicity of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs was evaluated by a CCK-8 assay. Various concentrations of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (0, 25, 50, 100, 200, 400, and 800 μg/mL) were added to the HepG2 cells and cocultured for 12 or 24 h. Subsequently, the CCK-8 Kit (Yeasen, China) was used to detect the cell viability according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer. The above experiment was repeated in triplicate.

2.8. In Vitro Tumor Cell Ablation

To study the tumor ablation ability of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs in vitro, the Live/Dead staining assay and CCK-8 assay were performed to detect the tumor cell ablation effect of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. The Bi-Ag@PVP NPs with concentrations ranging from 0 to 800 μg/mL were added to the cells and irradiated with an 808 nm laser (2 W/cm2, 5 min), after which they were cultured for additional 12 h. Subsequently, the CCK-8 assay was performed, as mentioned above. Finally, the relative cell viabilities at different concentrations were calculated. The Live/Dead staining assay was further performed to evaluate the antitumor effect of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs in vitro. In detail, the HepG2 cells were cocultured with or without 400 μg/mL of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. After the HepG2 cells were treated with or without an 808 nm laser (2 W/cm2, 5 min), the cells were stained with Calcein-AM and propidium iodide (PI) for 30 min. The cells were then observed via CLSM. The above experiments were also repeated in triplicate.

2.9. Cellular Uptake

First, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs were labeled with rhodamine through the NHS/EDC reaction. Then, the HepG2 cells were cocultured with the rhodamine-labeled Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (400 μg/mL) for different times (0.5, 1, 3, and 6 h) at 37 °C. The cells were then washed with PBS three times and fixed with paraformaldehyde fixative. The nuclei were stained with Hoechst solution at room temperature for 10 min. Finally, the fluorescence intensity of the cells was observed by CLSM.

2.10. Apoptosis Analysis

The HepG2 cells were cultured with Bi-Ag@PVP NPs at different concentrations (0, 100, 200, and 400 μg/mL) overnight, and then the cells were irradiated with or without an 808 nm laser (2 W/cm2) for 5 min. The cells were then collected and stained using the Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (Vazyme, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The apoptosis rate of the HepG2 cells was detected using a flow cytometer (Beckman, United States).

2.11. Mitochondrial Function Evaluation

The JC-1 mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) assay was used to detect whether the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs could damage the mitochondria after 808 nm laser irradiation. HepG2 cells were cocultured with or without Bi-Ag@PVP NPs for 6 h. The HepG2 cells were cultured without Bi-Ag@PVP NPs as a control group. The remaining groups were irradiated with or without 808 nm irradiation (2 W/cm2, 5 min) and then incubated for another 6 h. Finally, the cells were labeled using the JC-1 kit (MedChemExpress, China) according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer, and the fluorescence intensity of the cells was observed by CLSM.

2.12. Western Blot Assay

The HepG2 cells with different treatments (1, without Bi-Ag@PVP NPs or 808 nm laser; 2, with only 808 nm laser for 5 min; 3, with only Bi-Ag@PVP NPs; 4, 100 μg/mL Bi-Ag@PVP NPs + 808 nm laser; 5, 200 μg/mL Bi-Ag@PVP NPs + 808 nm laser; and 6, 400 μg/mL Bi-Ag@PVP NPs + 808 nm laser) were collected. The proteins were completely extracted, and their concentrations was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Yeasen, China). After electrophoresis and being transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (Millipore, Germany), 5% skimmed milk was used to block the nonspecific binding sites. Subsequently, the membranes were incubated with HSP 70, Bcl-2, caspase-3, and caspase-8 (1:500, ProteinTech, rabbit) at 4 °C while being shaken slowly overnight, after which they were washed with TBST three times and then incubated with secondary antibodies (antirabbit, ProteinTech) for 2 h. Subsequently, the PVDF membranes containing the protein of interest were analyzed using an automatic chemiluminescence imaging analysis system (Tanon, China).

2.13. In Vivo Tumor Ablation and Histological Assay

To study the in vivo tumor ablation effect of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs, 16 HepG2-bearing nude mice were randomly divided into four groups for different experimental purposes: (a) control, (b) 808 nm laser irradiation (2 W/cm2, 5 min), (c) Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (400 μg/mL), and (d) Bi-Ag@PVP NPs + 808 nm laser irradiation. Groups (c) and (d) were injected with Bi-Ag@PVP NPs, while the other two groups were injected with an equivalent amount of PBS solution. After groups (b) and (d) were irradiated under an 808 nm laser (2 W/cm2) for 5 min, the tumor volume and body weight of each group after treatment were calculated and recorded over 12 days. After 12 days, all the mice were sacrificed and dissected to extract the major organs (heart, liver, spleen, lungs, kidneys, and brain). Subsequently, hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining was performed following a previously reported procedure.27

2.14. CT Performance of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs

To study the in vitro CT performance of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs, different concentrations of Bi-Ag@PVP NP and Iohexol solutions (0, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, and 20 mg/mL) were prepared and transferred into 300-μL Eppendorf (EP) tubes. The images and CT values were captured and recorded using an X-ray CT machine (Siemense Inveon PET/CT, Germany) operated at 80 kV and 50 μA. The in vivo CT scans were performed as follows. The HepG2-bearing mice were intraperitoneally anesthetized, and the corresponding CT images before and after the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (100 μL, 1 mg/mL) were intratumorally administered and collected.

2.15. PA Performance of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs

The in vitro PA imaging was performed as follows. Different concentrations of Bi-Ag@PVP NP suspensions (0, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL) were prepared and transferred into 300 μL EP tubes. The PA images were then captured using an ultrasonic PA multimode imaging system (FUJIFILM VisualSonics, Japan). To study the in vivo PA performances of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs, the mice were intraperitoneally anesthetized and the corresponding preinjection and postinjection PA images with the Bi-Ag@PVP NP suspension (100 μL, 200 μg/mL) were obtained.

2.16. Antibacterial Capacity

The antibacterial properties of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs were explored by a coculture of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs with E. coli and 808 nm laser irradiation of the NPs to observe the effect on the bacterial growth. Briefly, the bacterial suspensions with concentrations of 107 cfu/mL were cocultured with the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (400 μg/mL), and the bacterial suspensions containing different concentrations of NPs (100, 200, and 400 μg/mL) were irradiated with an 808 nm laser (2 W/cm2, 5 min). The bacterial suspensions without NPs or with only laser irradiation were used as the controls. All the suspensions were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and then the bacterial suspensions were measured at 600 nm to obtain the corresponding optical density values. The bacterial suspensions were diluted and placed on Luria Broth Agar to observe the formation of bacterial colonies. Finally, SEM was used to observe the morphology of the bacteria after irradiation, as previously reported.28

2.17. Statistical Analysis

All the statistical significance values were analyzed via Student’s t-test and one-way analysis of variance using the Origin (version 9.0) software. All quantitative results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation, and *P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. The CT and PA signal intensities were quantified by the software that came with the instruments.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Fabrication and Physical Characteristics of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs

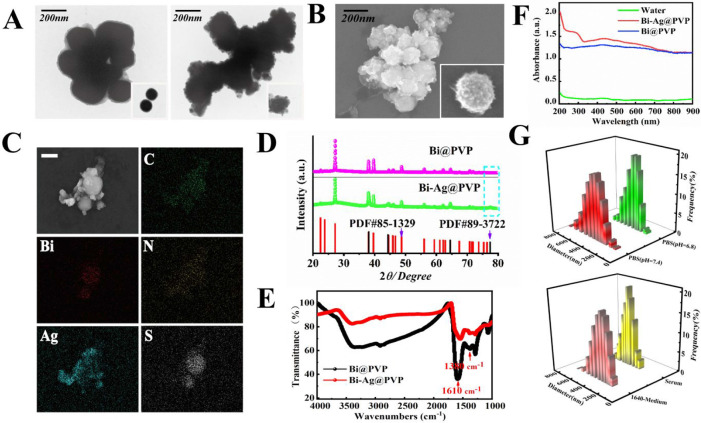

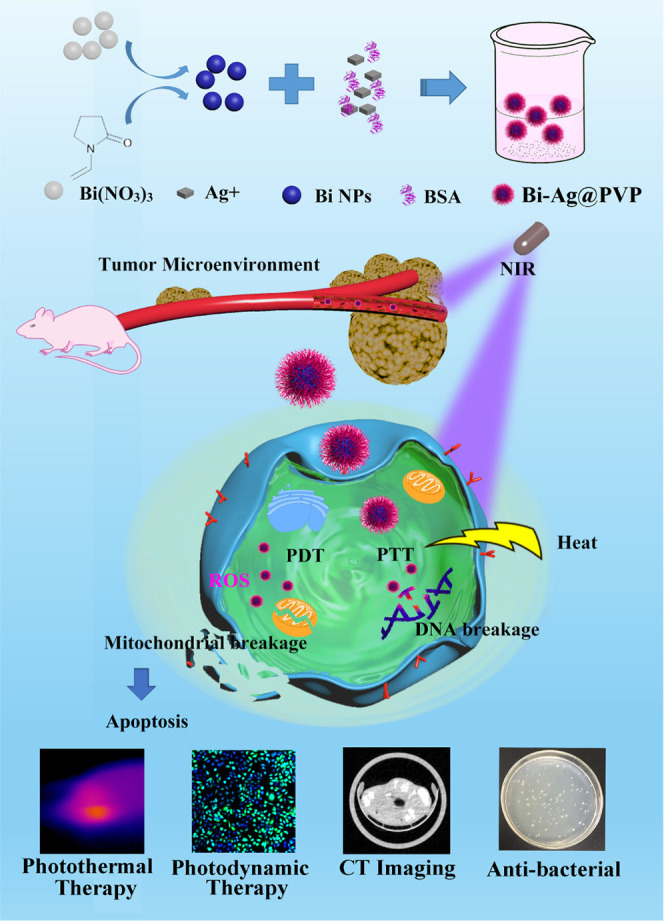

The fabrication process of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs is shown in Scheme 1. First, the Bi@PVP NPs were prepared via a facile solvothermal method, and then the BSA reduced AgNO3 into Ag+. Finally, the Ag+ was adsorbed on the surface of the Bi@PVP NPs by electrostatic adsorption to form Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. The TEM images (Figure 1A) reveal the morphologies and particle sizes of the Bi@PVP and Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. The Bi-Ag@PVP NPs exhibited nanoheterostructures, and compared with the Bi NPs, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs had a slightly larger particle size (272.2 ± 17.11 nm) than the Bi@PVP NPs (250.0 ± 16.36 nm). The SEM image of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs shows their nanoheterostructures (Figure 1B). The EDS (Figure 1C) spectra show that the samples contained C, Bi, N, Ag, and S. Based on the TEM, EDS, and SEM results, we concluded that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs were successfully prepared. Figure 1D shows the XRD patterns of the Bi@PVP and Bi-Ag@PVP NPs, and all peaks of the Bi@PVP NPs were well matched with the bismuth standard card (PDF#85-1329). The XRD pattern of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs is shown by a green line. All the peaks well matched with the Bi@PVP NPs, except for the characteristic peak of the blue line frame, which was consistent with the silver standard card (PDF#89-3722). This further indicated that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs were successfully synthesized. Previous studies demonstrated that PVP could improve the biocompatibility of NPs.29−31 Thus, the PVP was coated on the surfaces of the Bi@PVP NPs, improving the stability and biocompatibility of the final products. FTIR spectra were employed to verify the surface properties of the Bi and Bi-Ag NPs. Figure 1E shows that both the Bi and the Bi-Ag NPs possessed C=O and C–N groups with strong absorption peaks at 1610 and 1380 cm–1, respectively, which are the characteristic groups of PVP, indicating the presence of PVP on the surfaces of the NPs.32Figure 1F shows that both the Bi@PVP and Bi-Ag@PVP NPs exhibited a broad absorption peak in the ultraviolet (UV)–visible (vis)–NIR spectrum, suggesting that the as-prepared Bi-Ag@PVP NPs could have potential photothermal effects. In addition, the absorption wavelength of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs was similar to that of the Bi@PVP NPs. However, it is important to point out that there were subtle differences in their absorption spectra, which may have been due to the Ag of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. As is well known, a relatively uniform particle size distribution is a prerequisite for NPs in biological applications. Thus, DLS was used to analyze the size distributions of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs in different solutions. Figure 1G shows that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs had relatively concentrated particle size distributions in PBS (pH = 7.4), acidic PBS (pH = 6.8), serum, and 1640 medium, indicating that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs had good stability in the different solutions. Thus, they are suitable for biological applications.

Scheme 1. Schematic Diagram of the Synthesis Process and the Corresponding Functions of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs.

Figure 1.

(A) TEM images of Bi and Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. (B) SEM image of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. (C) Dark-field TEM image of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs and the corresponding TEM elemental mapping images of C, Bi, N, Ag, and S. (D) XRD patterns and (E) FTIR spectra of Bi@PVP and Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. (F) UV–NIR absorption spectra of water (green), Bi@PVP NPs (blue), and Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (red). (G) DLS histograms of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs in PBS (pH = 7.4), PBS (pH = 6.8), serum, and 1640 medium.

3.2. Photothermal Performances of Bi@PVP and Bi-Ag@PVP NPs

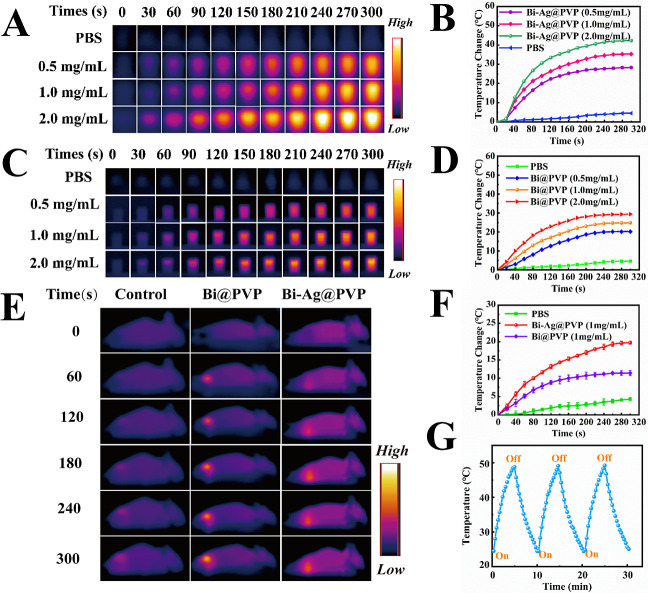

The photothermal performances of Bi@PVP and Bi-Ag@PVP NPs were measured by employing NIR irradiation (808 nm, 2 W/cm2). As shown in Figure 2B, the temperatures of the Bi-Ag@PVP suspensions of various concentrations (0.5, 1, and 2 mg/mL) increased rapidly from 0 to 120 s, and then the temperatures rose slowly from 120 to 300 s. Compared with the solution temperatures before irradiation, the temperatures of the Bi-Ag@PVP NP suspensions with concentrations of 0.5, 1, and 2 mg/mL increased by 30.6, 36.0, and 42.3 °C after irradiation, respectively. Meanwhile, the PBS group exhibited negligible temperature elevations (ΔT). The infrared thermal images for the Bi-Ag@PVP NP suspensions (0.5, 1, and 2 mg/mL) and PBS at different times were captured using a thermal imager (Figure 2A). Figure 2C,D shows that the ΔT of the Bi@PVP NP suspensions (0.5, 1, and 2 mg/mL) also increased and the corresponding temperatures at different intervals were also captured by the thermal imager. Compared with the Bi@PVP NP suspension at the same concentration, the Bi-Ag@PVP NP suspension exhibited more violent temperature changes. The ΔT values of the former were 20.2, 24.8, and 29.4 °C, respectively, lower than those of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. This phenomenon may have been related to the enhanced surface plasmon resonance derived from Ag.

Figure 2.

(A) Infrared thermal images of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs at different times and (B) the fitted curves. (C) Photothermal heating curves of the Bi@PVP NPs and (D) the corresponding infrared thermal images. (E and F) Infrared thermal images and the corresponding temperature–time curves of the Bi@PVP (purple) and Bi-Ag@PVP (red) NPs in HepG2-bearing mice. (G) Heating/cooling cycle curve of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs.

Encouraged by the excellent photothermal results of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs in vitro, we then compared the photothermal effects of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs with the Bi@PVP NPs in HepG2-bearing mice. Figure 2E,F shows that after intratumoral injection of the Bi-Ag@PVP and Bi@PVP NPs at the same concentration (100 μL, 1 mg/mL) and 808 nm laser irradiation (2 W/cm2, 5 min), the temperature at the tumor sites after the administration of the Bi-Ag@PVP and Bi@PVP NP solutions increased by 19.7 and 11.4 °C, respectively, corresponding to the final temperatures of 52.4 and 45.6 °C, respectively. However, the tumor site temperature of the mice administered with PBS did not increase significantly. The in vivo photothermal performance proved that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs could effectively convert the light into heat in vivo. Figure 2G shows that after rapid heating/cooling for three cycles, there was no apparent attenuation of the temperature–time curve, demonstrating that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs possessed great photostability properties. According to previous studies, when the cellular temperature is higher than 39 °C, protein denaturation begins.33,34 When the cellular temperature exceeds 41 °C, the cells will be inactivated for several hours, and when the temperature is greater than 48 °C for extended periods (4–6 min), the cell inactivation will become irreversible.35,36 Thus, the above results showed that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs could serve as a potential candidate for PTA. They possessed good photostability and could exert an excellent PTT effect.

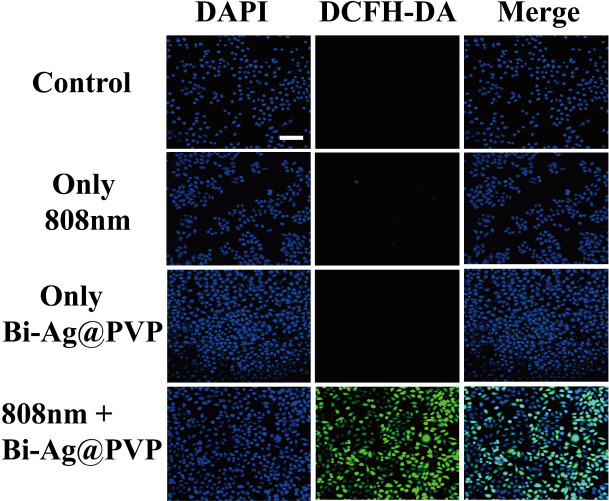

3.3. Intracellular ROS Generation

To monitor whether the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs can induce the formation of intracellular ROS in HepG2 cells, a DCFH-DA probe was used to detect the intracellular ROS production. Nonfluorescent DCFH-DA could enter a cell freely, and the intracellular esterase hydrolyzed the DCFH-DA into DCFH after penetrating the cell membrane. The DCFH then accumulated in the cells, and the intracellular ROS oxidized the DCFH to fluorescent DCF, showing green fluorescence, which was evident under CLSM. As shown in Figure 3, intense green fluorescence was detected after the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs were irradiated with the 808 nm laser (2 W/cm2) for 5 min, indicating the intracellular generation of ROS while the other three groups showed negligible fluorescence under CLSM. Thus, we concluded that after irradiation with the 808 nm laser, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs could induce intracellular ROS generation, which indicated that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs possessed PDT properties.

Figure 3.

Fluorescence images of intracellular ROS in HepG2 cells. Strong green fluorescence was observed in Bi-Ag@PVP NPs + 808 nm laser-irradiated sample (scale bar: 100 μm).

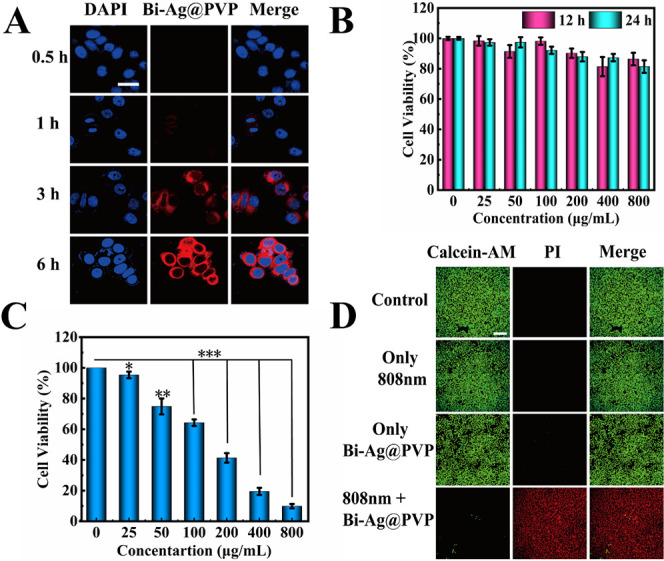

3.4. Biosafety and Tumor Destruction In Vitro

High biocompatibility and low cytotoxicity are indispensable for the biological application of NPs.37,38 Before evaluating biosafety and tumor destruction effects in vitro, the internalization behavior of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs was studied. Rhodamine-labeled Bi-Ag@PVP NPs were cocultured with HepG2 cells for different time periods (0.5, 1, 3, and 6 h). Figure 4A shows that a time-dependent enhanced red fluorescence occurred, indicating that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs could be effectively internalized into HepG2 cells in a relatively short time. After studying the cellular uptake process of NPs, we then studied the cytocompatibility of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs, Figure 4B reveals the cell viability of HepG2 cells incubated with various concentrations of NPs for different times. The experimental groups of HepG2 cells all had high cell viabilities from 81.4% to 98.4%. Furthermore, when the Bi-Ag@PVP NP concentration reached 800 μg/mL and cocultured with HepG2 cells for 24 h, the HepG2 cells retained high cell viability (81.4%). These results indicated that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs had favorable biocompatibility in vitro. Next, the tumor ablation effect in vitro was studied through CCK-8 and Live/Dead staining. The HepG2 cells were treated with different concentrations of Bi-Ag@PVP suspensions and irradiated under an 808 nm laser (2 W/cm2) for 5 min. Figure 4C shows that as the concentrations of Bi-Ag@PVP NP suspensions increased, the cell viability decreased significantly, and the cell survival rate decreased by only about 10% when the concentration of the Bi-Ag@PVP NP suspension reached 800 μg/mL. This result indicated that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs could exhibit synergistic PDT and PTT to exert excellent tumor ablation effects in vitro. Moreover, Live/Dead staining was also performed to prove the in vitro tumor destruction of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. Figure 4D shows that compared with the control group, there was little red fluorescence observed in the NIR-only group and the group with only the sample. This indicated that no apparent cell death occurred in the above two groups, which was consistent with the CCK-8 results. After the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs were irradiated with the 808 nm laser (2 W/cm2, 5 min), strong red fluorescence was observed. However, negligible green fluorescence was detected, which indicated that the HepG2 cells were almost completely ablated. The above-mentioned results indicated that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs had low cytotoxicity and great in vitro tumor ablation effects through synergistic PDT and PTT.

Figure 4.

(A) CLSM images of HepG2 cells cocultured with rhodamine-labeled Bi-Ag@PVP NPs at different times (0.5, 1, 3, and 6 h) (scalebar: 20 μm). CCK-8 assay results for cell viability after (B) different treatments in the dark and (C) under 808 nm laser (2 W/cm2) for 5 min. (D) CLSM images of HepG2 cells after different treatments and staining with Calcein-AM and PI (scale bar: 100 μm). Note: P < 0.05 was considered a significant difference; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

3.5. Bi-Ag@PVP-NP-Induced Apoptosis and Its Mechanisms

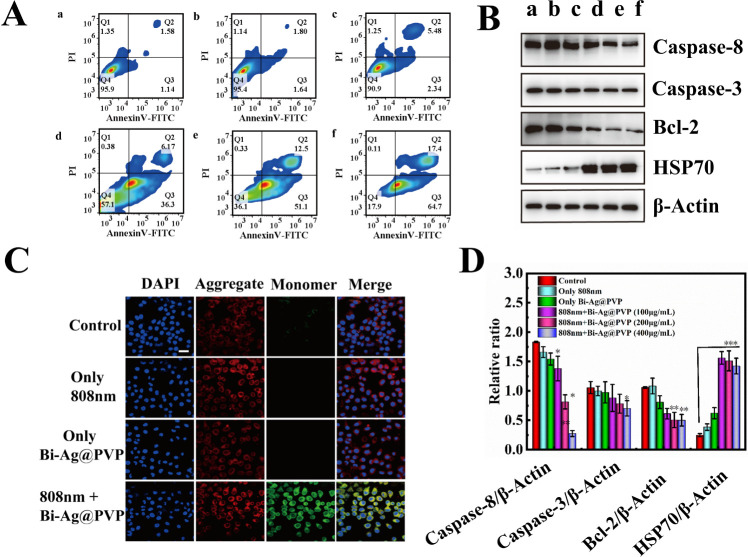

Encouraged by the above results, we next explored the effect of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs on HepG2 cell apoptosis and their mechanisms. Figure 5A shows that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs could efficiently induce cell apoptosis, and the rate of apoptosis gradually increased (from 42.47% to 82.1%) as the concentration of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs increased. However, the apoptosis induced by Bi-Ag@PVP NPs was mainly early apoptosis. We subsequently studied the mechanism of the Bi-Ag@PVP-NP-induced cell apoptosis. It is well known that mitochondrial dysfunction represents the early stages of apoptosis.39,40 Thus, the JC-1 MMP assay was used to detect whether the mitochondria were functioning normally. JC-1 aggregates could be detected in the form of red fluorescence, indicating that the mitochondria functioned well. When the MMP (ΔΨm) changed (ΔΨm is high in healthy cells and low in unhealthy cells), the JC-1 aggregates transformed into JC-1 monomers, which appeared as green fluorescence. As shown in Figure 5C, only slight green fluorescence was observed in different treatment groups (control, only 808 nm laser irradiation, and only Bi-Ag@PVP NPs). However, a large amount of green fluorescence was observed in the treatment group with the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs under 808 nm irradiation, indicating that the mitochondria were dysfunctional. As mentioned above, mitochondrial dysfunction can cause early cell apoptosis; hence, the mechanism through which the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs induced cell apoptosis may be attributed to the pathway of mitochondrial dysfunction. Two molecules are mainly responsible for regulating cell apoptosis: the caspase family and the Bcl-2 family.41,42 Both families are related to the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway. Thus, we tested the expression of the related proteins in HepG2 cells under different treatment conditions. Figure 5B shows that the decrease in the antiapoptotic Bcl-2 protein was detected, and the amount of protein expression gradually decreased with an increase in the Bi-Ag@PVP NP concentration. Meanwhile, the expression of caspase-3 and caspase-8 also gradually increased with an increase in the Bi-Ag@PVP concentration. Furthermore, the expression of HSP 70 was detected, which is synthesized by a cell to protect itself from hyperthermia or oxidative stress.43 After the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs were irradiated with the 808 nm laser, the expression of HSP 70 significantly increased, indicating that the HepG2 cells underwent thermal damage, which may have also caused mitochondrial dysfunction. The corresponding statistical analyses of the protein expression are given in Figure 5D. These results demonstrated that Bi-Ag@PVP NPs could induce HepG2 cells apoptosis, which may have occurred through the mitochondrial apoptosis pathway.

Figure 5.

(A) Cell apoptosis rate after different treatments (a: control, b: laser only, c: Bi-Ag@PVP NPs alone, d: Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (100 μg/mL) + laser, e: Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (200 μg/mL) + laser, and f: Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (400 μg/mL) + laser). (B) Caspase-8, caspase-3, Bcl-2, and HSP 70 protein levels in HepG2 cells after different treatments (a–f have the same meanings as in (A)). (C) CLSM images of HepG2 cells after different treatments and staining by the JC-1 kit. The blue fluorescence corresponds to 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI), the red fluorescence corresponds to JC-1 aggregates, and the green fluorescence corresponds to JC-1 monomers (scalebar: 20 μm). (D) Statistical analysis of protein expression (caspase-8, caspase-3, Bcl-2, and HSP 70).

3.6. In Vivo Tumor Ablation and Biocompatibility

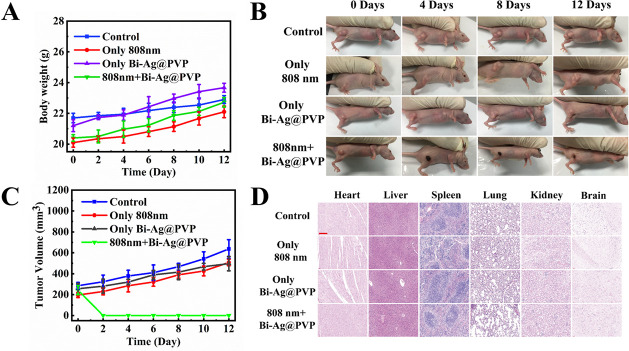

The in vivo tumor ablation effect of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs wase determined by intratumorally injecting the Bi-Ag@PVP NP suspension (100 μL, 400 μg/mL) into HepG2-bearing mice followed by NIR irradiation (808 nm, 2 W/cm2, 5 min). Figure 6B,C reveals that due to the high malignancy of hepatocellular cancer, the tumor volume without any treatment rapidly increased. The NP and 808 nm laser irradiation-alone groups could not exert PDT/PTT effects; thus, the tumor sizes increased rapidly. Surprisingly, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (100 μL, 400 μg/mL) + 808 nm irradiation group tumors were completely ablated (Figure 6B,C), demonstrating that the Bi-Ag@PVP-based PDT/PTT had great antitumor effects in vivo. Furthermore, the body weights (Figure 6A) in all groups slightly increased, and there was no significant difference, suggesting that the NIR and NPs have no significant influence on the health of the mice. After treatment, histological studies were performed to determine the biocompatibility of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. As shown in Figure 6D, there were no apparent histological changes in any group. More importantly, there was no significant damage to metabolic organs, indicating the outstanding biocompatibility of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. These results demonstrated that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs could achieve PDT/PTT synergy to exert outstanding antitumor effects, while causing no evident damage to normal organs.

Figure 6.

(A) Relative body weights after different treatments. (B) Images of HepG2-bearing mice after 12 days of treatment. (C) Tumor volume changes after 12 days of treatment. (D) H&E staining of major organs in different treatments groups (scalebar: 200 μm).

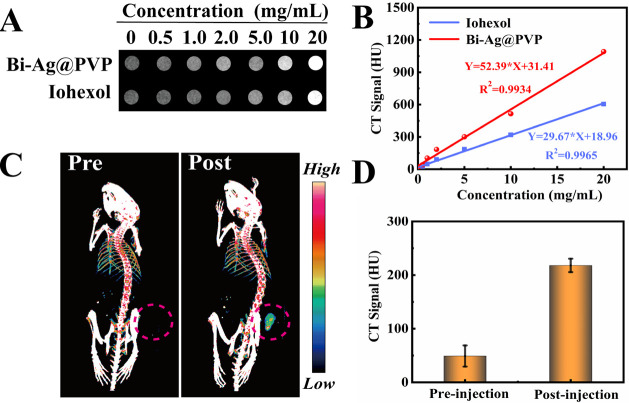

3.7. CT Performance of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs In Vitro and In Vivo

The ideal nanotheranostic platform should possess a multimodality of imaging and therapy. In particular, during the application of PTAs for treatment, accurate spatiotemporal change monitoring is required, which can guide the therapeutic process, monitoring the efficacy, avoiding damage to the surrounding tissue, and reducing the associated side effects.44 Due to the excellent X-ray attenuation coefficient of Bi,45−47 the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs were expected to be qualified for CT imaging. It is well known that as one of the commonly used noninvasive methods, CT has the ability to produce internal tissue and organ cross-sectional images with high resolution and low cost.48−51 Thus, it is an essential way to diagnose various clinical diseases, including tumors. Herein, we studied the CT performance of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. Figure 7A shows the corresponding CT images of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs and Iohexol. As the concentration of the suspension increased, the gray level of the image gradually changed from a black shade to a white shade. However, at the same concentration, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs produced a brighter shade than Iohexol because the X-ray attenuation coefficient of Bi is higher than that of I (the value for Bi is 5.74 cm2 kg–1 and that for I is 1.94 cm2 kg–1, at 100 keV).52Figure 7B shows the relationship between the CT values and the concentration of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs and Iohexol. The R2 values of the fitted curves were larger than 0.99, indicating the great fit between the concentration and CT values. Meanwhile, the slope of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs was 52.39, which was much higher than that of Iohexol (slope = 29.67). These results indicate that compared with Iohexol, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs produced a better CT contrast effect in vitro. Encouraged by the above results, we then evaluated the CT performance of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs in vivo. The HepG2-bearing mice were intraperitoneally anesthetized. Subsequently, the Bi-Ag@PVP suspension (1 mg/kg, 100 μL) was injected intratumorally into the HepG2-bearing mice. The images of the tumor sites pre and postinjection of the Bi-Ag@PVP NP suspension are shown in Figure 7C. There was no significant CT signal intensity at the tumor site before injection. After the administration of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs, the CT signal at the tumor site was greatly enhanced (shown by the red circle), and the CT signal intensities before and after injection are given in Figure 7D. The above results indicate that Bi-Ag@PVP NPs can be a promising candidate for in vitro and in vivo CT contrast agents.

Figure 7.

(A) X-ray absorption capacity of Bi-Ag@PVP and Iohexol and (B) signal-concentration fitting curves. (C) In vivo CT imaging ability of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (the tumor site is highlighted by the red circle) and (D) the corresponding CT signal intensity.

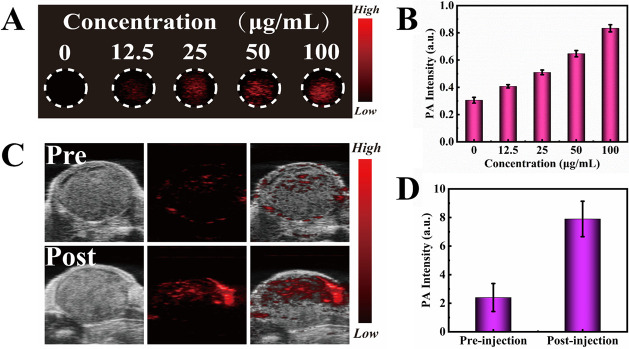

3.8. PA Performance of Bi-Ag@PVP NPs In Vitro and In Vivo

As another widely used and noninvasive biomedical method, PA imaging utilizes lasers to acoustically visualize biological tissue, providing relatively deep imaging penetration and good spatial resolution.45,53,54Figure 8A reveals that as the concentrations of the Bi-Ag@PVP NP suspensions gradually increased, greater red signal intensity was detected under 808 nm laser irradiation, and the quantitative analysis of the PA intensity is shown in Figure 8B, suggesting the great in vitro PA imaging capacity of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs.

Figure 8.

(A) PA images and (B) quantitative diagram of the PA intensity with different concentrations (0, 12.5, 25, 50, and 100 μg/mL). (C) PA images of the tumor site before and after intratumorally administering the Bi-Ag@PVP NP suspension (100 μL, 200 μg/mL). (D) Quantitative PA intensity of the tumor site before and after administering the Bi-Ag@PVP NP suspension (100 μL, 200 μg/mL).

The PA imaging ability of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs was further studied in vivo. Figure 8C shows that slight red PA signals were observed in the tumor site before administration, which may have been caused by tumor blood.44 In contrast, the PA signal was remarkably increased after the in situ administration of the Bi-Ag@PVP NP suspensions (100 μL, 200 μg/mL). The PA intensity after injection was approximately 4 times greater than that before injection (see Figure 8D). Thus, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs are expected to be a highly effective contrast agent for PA imaging. Based on the CT and PA imaging performances, we concluded that Bi-Ag@PVP NPs can be used as a highly effectively multimodal contrast agent for CT/PA imaging-guided PDT/PTT synergistic therapy.

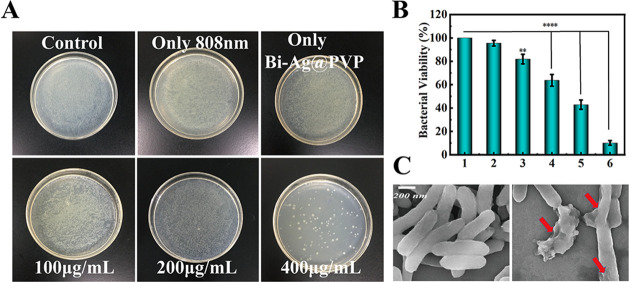

3.9. Antibacterial Ability

For most tumors, chemical drug-mediated chemotherapy is an effective treatment. However, most chemical drugs can damage the immune system, leading to decreased immune function in patients with or without defects.55−57 Therefore, bacterial infections have become a common complication in tumor treatment. Silver is an agent with a long history that has been widely used for controlling infections, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and E. coli infections.58,59 Recently, with the development of nanotechnology, silver-based NPs are commonly used to treat various infections and burn wounds due to their excellent antibacterial properties.60−64 Thus, we evaluated the antibacterial capacity of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs. Figure 9B shows that after coculturing with Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (400 μg/mL) for 6 h, the normalized bacterial viability of E. coli was reduced to 81.9%, which may have been related to the silver doping in NPs. When the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs were illuminated with NIR (808 nm, 2 W/cm2, 5 min) and then cocultured with E. coli for 6 h, the normalized bacterial viabilities of E. coli were 63.7%, 42.9%, and 10.2% at concentrations of 100, 200, and 400 μg/mL, respectively. Figure 9A shows that compared with the control, the number of bacterial colonies in experiment groups were significantly reduced. The morphological changes of E. coli after treatment (Bi-Ag@PVP NPs + 808 nm laser) were observed by SEM, and Figure 9C shows that compared with the control group, the E. coli was significantly damaged after treatment and the integrity of the bacteria was destroyed (shown by the red arrow). The above results indicate that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs have an outstanding antibacterial capacity, which can effectively reduce the infection risk during cancer therapy.

Figure 9.

(A) Images of E. coli colonies on different treatment groups. (B) Normalized bacterial viability after different treatments (1: control, 2: laser alone, 3: Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (400 μg/mL) alone, 4: Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (100 μg/mL) + laser, 5: Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (200 μg/mL) + laser, and 6: Bi-Ag@PVP NPs (400 μg/mL) + laser). (C) SEM images of E. coli before and after treatment (Bi-Ag@PVP NPs + laser). P < 0.05 was considered to be a significant difference; **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

These overall results indicate that the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs can be used to synergize PDT and PTT, exhibiting excellent antitumor effects, enhancing the CT/PA imaging contrast and demonstrating great antibacterial properties. However, the long-term biocompatibility of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs and the metabolic processes in vivo must be further studied. Furthermore, due to the lack of positive tumor targeting, modification of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs with tumor-specific targeting antibodies (such as anti-neuropilin antibodies)65 or targeting peptides66 can achieve precise tumor-targeted therapy and real-time CT/PA monitoring, thereby reducing the occurrence of side effects during tumor treatment in future work.

4. Conclusions

In summary, a smart nanotheranostic platform Bi-Ag@PVP NPs was constructed and can be employed for tumor PDT/PTT, CT/PA imaging, and antibacterial applications. The Bi-Ag@PVP NPs exhibited great biocompatibility and better photothermal performances than Bi@PVP NPs. Importantly, the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs can also cause tumor cells to produce ROS, producing excellent tumor ablation abilities in vitro and in vivo. Simultaneously, duo to the high CT and PA contrast properties of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs, they can achieve multimodal-guided PDT/PTT synergistic therapy. Finally, the antibacterial properties of the Bi-Ag@PVP NPs were also studied. The results demonstrated that Bi-Ag@PVP NPs can effectively ablated E. coli, which can minimize the infection risk during cancer therapy. Overall, our research provides a novel nanotheranostic platform for cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 81773770), the Science and Technology Department of Fujian Province, China (grant nos. 2018R1036-1, 2019R1001-2, and 2020R1001001), the Xiamen Medical and Health Project, China (grant no. 3502Z20194055), the Horizontal Project of Xiamen University, China (grant no. XDHT2019206A), and the Key Project of Medical Science and Technology Innovation Project of Nanjing Military Region, China (grant no. 14ZD33) for financial support.

Author Contributions

# Z.Z. and J.X. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Siegel R. L.; Miller K. D.; Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 2020, 70, 7–30. 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. L.; Miller K. D.; Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 7–30. 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. L.; Miller K. D.; Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2019. Ca-Cancer J. Clin. 2019, 69, 7–34. 10.3322/caac.21551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benitez Majano S.; Di Girolamo C.; Rachet B.; Maringe C.; Guren M. G.; Glimelius B.; Iversen L. H.; Schnell E. A.; Lundqvist K.; Christensen J.; Morris M.; Coleman M. P.; Walters S. Surgical treatment and survival from colorectal cancer in Denmark, England, Norway, and Sweden: A population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2019, 20, 74–87. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30646-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denduluri N.; Chavez-MacGregor M.; Telli M. L.; Eisen A.; Graff S. L.; Hassett M. J.; Holloway J. N.; Hurria A.; King T. A.; Lyman G. H.; Partridge A. H.; Somerfield M. R.; Trudeau M. E.; Wolff A. C.; Giordano S. H. Selection of Optimal Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Targeted Therapy for Early Breast Cancer: ASCO Clinical Practice Guideline Focused Update. J. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 36, 2433–2443. 10.1200/JCO.2018.78.8604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong N.; Zhang Y.; Teng X.; Wang Y.; Huo S.; Qing G.; Ni Q.; Li X.; Wang J.; Ye X.; Zhang T.; Chen S.; Wang Y.; Yu J.; Wang P. C.; Gan Y.; Zhang J.; Mitchell M. J.; Li J.; Liang X. J. Proton-driven transformable nanovaccine for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2020, 15, 1053–1064. 10.1038/s41565-020-00782-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H.; Takiguchi Y.; Minami H.; Akiyoshi K.; Segawa Y.; Ueda H.; Iwamoto Y.; Kondoh C.; Matsumoto K.; Takahashi S.; Yasui H.; Sawa T.; Onozawa Y.; Chiba Y.; Togashi Y.; Fujita Y.; Sakai K.; Tomida S.; Nishio K.; Nakagawa K. Site-Specific and Targeted Therapy Based on Molecular Profiling by Next-Generation Sequencing for Cancer of Unknown Primary Site: A Nonrandomized Phase 2 Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020, 6, 1931–1938. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.4643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Lovell J. F.; Yoon J.; Chen X. Clinical development and potential of photothermal and photodynamic therapies for cancer. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2020, 17, 657–674. 10.1038/s41571-020-0410-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sargos P.; Chabaud S.; Latorzeff I.; Magné N.; Benyoucef A.; Supiot S.; Pasquier D.; Abdiche M. S.; Gilliot O.; Graff-Cailleaud P.; Silva M.; Bergerot P.; Baumann P.; Belkacemi Y.; Azria D.; Brihoum M.; Soulié M.; Richaud P. Adjuvant radiotherapy versus early salvage radiotherapy plus short-term androgen deprivation therapy in men with localised prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy (GETUG-AFU 17): a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020, 21, 1341–1352. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30454-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing R.; Zou Q.; Yuan C.; Zhao L.; Chang R.; Yan X. Self-Assembling Endogenous Biliverdin as a Versatile Near-Infrared Photothermal Nanoagent for Cancer Theranostics. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2019, 31, e1900822 10.1002/adma.201900822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Xia D.; Liu J.; Huo D.; Jiang X.; Hu Y. Bypassing the Immunosuppression of Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells by Reversing Tumor Hypoxia Using a Platelet-Inspired Platform. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2020, 30, 2000189 10.1002/adfm.202000189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L.; Wang C.; Feng L.; Yang K.; Liu Z. Functional nanomaterials for phototherapies of cancer. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 10869–10939. 10.1021/cr400532z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu H.; Cheng P.; Chen P.; Pu K. Recent progress in the development of near-infrared organic photothermal and photodynamic nanotherapeutics. Biomater. Sci. 2018, 6, 746–765. 10.1039/C7BM01210A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P.; Hu C.; Ran W.; Meng J.; Yin Q.; Li Y. Recent Progress in Light-Triggered Nanotheranostics for Cancer Treatment. Theranostics 2016, 6, 948–968. 10.7150/thno.15217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo H.; Tao J.; Shi H.; He J.; Zhou Z.; Zhang C. Platelet-mimicking nanoparticles co-loaded with W18O49 and metformin alleviate tumor hypoxia for enhanced photodynamic therapy and photothermal therapy. Acta Biomater. 2018, 80, 296–307. 10.1016/j.actbio.2018.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Yan Q.; Li J.; Zhu Y.; Zhang Y. Nanoenabled Tumor Oxygenation Strategies for Overcoming Hypoxia-Associated Immunosuppression. ACS Appl. Bio Mater. 2021, 4, 277–294. 10.1021/acsabm.0c01328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Chen W.; Zhang T.; Jiang X.; Hu Y. Hybrid nanoparticle composites applied to photodynamic therapy: Strategies and applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2020, 8, 4726–4737. 10.1039/D0TB00093K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan M.; Zhao S.; Liu W.; Lee C. S.; Zhang W.; Wang P. Photosensitizers for Photodynamic Therapy. Adv. Healthcare Mater. 2019, 8, e1900132 10.1002/adhm.201900132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X.; Lee S.; Yoon J. Supramolecular photosensitizers rejuvenate photodynamic therapy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2018, 47, 1174–1188. 10.1039/C7CS00594F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Ren J.; Hua J.; Xia L.; He J.; Huo D.; Hu Y. Multifunctional Bi2WO6 Nanoparticles for CT-Guided Photothermal and Oxygen-free Photodynamic Therapy. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 1132–1146. 10.1021/acsami.7b16000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Zeng Y.; Zhang D.; Wu M.; Wu L.; Huang A.; Yang H.; Liu X.; Liu J. Glypican-3 antibody functionalized Prussian blue nanoparticles for targeted MR imaging and photothermal therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 3686–3696. 10.1039/C4TB00516C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia C.; Xie D.; Xiong L.; Zhang Q.; Wang Y.; Wang Z.; Wang Y.; Li B.; Zhang C. Nitroxide radical-modified CuS nanoparticles for CT/MRI imaging-guided NIR-II laser responsive photothermal cancer therapy. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 27382–27389. 10.1039/C8RA04501A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaafsma B. E.; Mieog J. S.; Hutteman M.; Van Der Vorst J. R.; Kuppen P. J.; Lowik C. W.; Frangioni J. V.; Van De Velde C. J.; Vahrmeijer A. L. The clinical use of indocyanine green as a near-infrared fluorescent contrast agent for image-guided oncologic surgery. J. Surg. Oncol. 2011, 104, 323–332. 10.1002/jso.21943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang C.; Cheng X.; Chen M.; Sheng J.; Ren J.; Jiang Z.; Cai J.; Hu Y. Fluorescence guided photothermal/photodynamic ablation of tumours using pH-responsive chlorin e6-conjugated gold nanorods. Colloids Surf., B 2017, 160, 345–354. 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2017.09.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y.; Wang J.; Liu L.; Sun Q.; You Q.; Cheng Y.; Wang Y.; Wang S.; Tan F.; Li N. One-Pot Synthesis of a Bismuth Selenide Hexagon Nanodish Complex for Multimodal Imaging-Guided Combined Antitumor Phototherapy. Mol. Pharm. 2018, 15, 1941–1953. 10.1021/acs.molpharmaceut.8b00106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Zhang J.; Huang F.; Deng Y.; Li B.; Ouyang R.; Miao Y.; Sun Y.; Li Y. X-ray and NIR light dual-triggered mesoporous upconversion nanophosphor/Bi heterojunction radiosensitizer for highly efficient tumor ablation. Acta Biomater. 2020, 113, 570–583. 10.1016/j.actbio.2020.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye D. X.; Ma Y. Y.; Zhao W.; Cao H. M.; Kong J. L.; Xiong H. M.; Mohwald H. ZnO-Based Nanoplatforms for Labeling and Treatment of Mouse Tumors without Detectable Toxic Side Effects. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 4294–4300. 10.1021/acsnano.5b07846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao C.; Xiang Y.; Liu X.; Cui Z.; Yang X.; Yeung K. W. K.; Pan H.; Wang X.; Chu P. K.; Wu S. Photo-Inspired Antibacterial Activity and Wound Healing Acceleration by Hydrogel Embedded with Ag/Ag@AgCl/ZnO Nanostructures. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 9010–9021. 10.1021/acsnano.7b03513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneda Y.; Tsutsumi Y.; Yoshioka Y.; Kamada H.; Yamamoto Y.; Kodaira H.; Tsunoda S.; Okamoto T.; Mukai Y.; Shibata H.; Nakagawa S.; Mayumi T. The use of PVP as a polymeric carrier to improve the plasma half-life of drugs. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 3259–3266. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara T.; Maeda T.; Sakamoto H.; Takasaki N.; Shigyo M.; Ishida T.; Kiwada H.; Mizushima Y.; Mizushima T. Evasion of the Accelerated Blood Clearance Phenomenon by Coating of Nanoparticles with Various Hydrophilic Polymers. Biomacromolecules 2010, 11, 2700–2706. 10.1021/bm100754e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabasum S.; Noreen A.; Kanwal A.; Zuber M.; Anjum M. N.; Zia K. M. Glycoproteins functionalized natural and synthetic polymers for prospective biomedical applications: A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 98, 748–776. 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.01.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J.; Chandrasekharan P.; Liu X. L.; Yang Y.; Lv Y. B.; Yang C. T.; Ding J. Manipulating the surface coating of ultra-small Gd2O3 nanoparticles for improved T1-weighted MR imaging. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 1636–1642. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepock J. R.; Cheng K. H.; Al-Qysi H.; Sim I.; Koch C. J.; Kruuv J. Hyperthermia-induced inhibition of respiration and mitochondrial protein denaturation in CHL cells. Int. J. Hyperthermia 1987, 3, 123–132. 10.3109/02656738709140380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepock J. R.; Frey H. E.; Rodahl A. M.; Kruuv J. Thermal-Analysis of Chl V79 Cells Using Differential Scanning Calorimetry—Implications for Hyperthermic Cell Killing and the Heat-Shock Response. J. Cell. Physiol. 1988, 137, 14–24. 10.1002/jcp.1041370103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J.; Wang W.; Xu X.; Lin Z.; Xie C.; Zhang Y.; Zhang T.; Li L.; Lu Y.; Li Q. AgBiS2 nanoparticles with synergistic photodynamic and bioimaging properties for enhanced malignant tumor phototherapy. Mater. Sci. Eng., C 2020, 107, 110324 10.1016/j.msec.2019.110324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaque D.; Martinez Maestro L.; Del Rosal B.; Haro-Gonzalez P.; Benayas A.; Plaza J. L.; Martin Rodriguez E.; Garcia Sole J. Nanoparticles for photothermal therapies. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 9494–9530. 10.1039/C4NR00708E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X.; Du B.; Huang Y.; Zheng J. Ultrasmall Noble Metal Nanoparticles: Breakthroughs and Biomedical Implications. Nano Today 2018, 21, 106–125. 10.1016/j.nantod.2018.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X.; Cao F.; Xiong L.; Yang Y.; Cao T.; Cai X.; Hai W.; Li B.; Guo Y.; Zhang Y.; Li F. Cytotoxicity, tumor targeting and PET imaging of sub-5 nm KGdF4 multifunctional rare earth nanoparticles. Nanoscale 2015, 7, 13404–13409. 10.1039/C5NR03374H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu P.; Ren J.; Xiong Y.; Yang Z.; Zhu W.; He Q.; Xu Z.; He W.; Wang J. Enhancing magnetic resonance/photoluminescence imaging-guided photodynamic therapy by multiple pathways. Biomaterials 2019, 199, 52–62. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Hernandez M.; Del Pino P.; Mitchell S. G.; Moros M.; Stepien G.; Pelaz B.; Parak W. J.; Galvez E. M.; Pardo J.; De La Fuente J. M. Dissecting the Molecular Mechanism of Apoptosis during Photothermal Therapy Using Gold Nanoprisms. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 52–61. 10.1021/nn505468v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk B.; Stoka V. Protease signalling in cell death: caspases versus cysteine cathepsins. FEBS Lett. 2007, 581, 2761–2767. 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.05.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams J. M.; Cory S. Bcl-2-regulated apoptosis: mechanism and therapeutic potential. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2007, 19, 488–496. 10.1016/j.coi.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmbrecht K.; Zeise E.; Rensing L. Chaperones in cell cycle regulation and mitogenic signal transduction: a review. Cell Proliferation 2000, 33, 341–365. 10.1046/j.1365-2184.2000.00189.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong Y.; Cheng X. J.; Bao T.; Zu M.; Yan L.; Yin W. Y.; Ge C. C.; Wang D. L.; Gu Z. J.; Zhao Y. L. Tungsten Sulfide Quantum Dots as Multifunctional Nanotheranostics for In Vivo Dual-Modal Image-Guided Photothermal/Radiotherapy Synergistic Therapy. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 12451–12463. 10.1021/acsnano.5b05825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X.; Li A.; Zhao C.; Yang K.; Chen X.; Li W. Ultrasmall Semimetal Nanoparticles of Bismuth for Dual-Modal Computed Tomography/Photoacoustic Imaging and Synergistic Thermoradiotherapy. ACS Nano 2017, 11, 3990–4001. 10.1021/acsnano.7b00476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Rivera M.; Kumar I.; Cho S. Y.; Cheong B. Y.; Pulikkathara M. X.; Moghaddam S. E.; Whitmire K. H.; Wilson L. J. High-Performance Hybrid Bismuth-Carbon Nanotube Based Contrast Agent for X-ray CT Imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2017, 9, 5709–5716. 10.1021/acsami.6b12768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.; Guo C.; Guo W.; Zhao X.; Liu S.; Han X. Multifunctional Bismuth Nanoparticles as Theranostic Agent for PA/CT Imaging and NIR Laser-Driven Photothermal Therapy. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2018, 1, 820–830. 10.1021/acsanm.7b00255. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lusic H.; Grinstaff M. W. X-ray-computed tomography contrast agents. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 1641–1666. 10.1021/cr200358s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N.; Choi S. H.; Hyeon T. Nano-sized CT contrast agents. Adv. Mater. (Weinheim, Ger.) 2013, 25, 2641–2660. 10.1002/adma.201300081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X. Y.; Sun L. D.; Zheng T.; Dong H.; Li Y.; Wang Y. F.; Yan C. H. PAA-capped GdF3 nanoplates as dual-mode MRI and CT contrast agents. Sci. Bull. 2015, 60, 1092–1100. 10.1007/s11434-015-0802-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J.; Wang P.; Zhang X.; Wang L.; Wang D.; Gu Z.; Tang J.; Guo M.; Cao M.; Zhou H.; Liu Y.; Chen C. Rapid Degradation and High Renal Clearance of Cu3BiS3 Nanodots for Efficient Cancer Diagnosis and Photothermal Therapy in Vivo. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 4587–4598. 10.1021/acsnano.6b00745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D.; Park S.; Lee J. H.; Jeong Y. Y.; Jon S. Antibiofouling polymer-coated gold nanoparticles as a contrast agent for in vivo X-ray computed tomography imaging [J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 7661–7665]. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 12585 10.1021/ja076341v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku G.; Zhou M.; Song S. L.; Huang Q.; Hazle J.; Li C. Copper Sulfide Nanoparticles As a New Class of Photoacoustic Contrast Agent for Deep Tissue Imaging at 1064 nm. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 7489–7496. 10.1021/nn302782y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.; Hu Y.; Miao Z.; Xu H.; Li C.; Zhao Y.; Li Z.; Chang M.; Ma Z.; Sun Y.; Besenbacher F.; Huang P.; Yu M. Dual-Stimuli Responsive Bismuth Nanoraspberries for Multimodal Imaging and Combined Cancer Therapy. Nano Lett. 2018, 18, 6778–6788. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.8b02639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozza C.; Cinausero M.; Iacono D.; Puglisi F. Hepatitis B and cancer: A practical guide for the oncologist. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2016, 98, 137–146. 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2015.10.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coussens L. M.; Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002, 420, 860–867. 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balkwill F.; Mantovani A. Inflammation and cancer: Back to Virchow?. Lancet 2001, 357, 539–545. 10.1016/S0140-6736(00)04046-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J. B.; Lam K.; Hansen D.; Burrell R. E. Efficacy of topical silver against fungal burn wound pathogens. Am. J. Infect. Control 1999, 27, 344–350. 10.1016/S0196-6553(99)70055-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah P. N.; Lin L. Y.; Smolen J. A.; Tagaev J. A.; Gunsten S. P.; Han D. S.; Heo G. S.; Li Y. L.; Zhang F. W.; Zhang S. Y.; Wright B. D.; Panzner M. J.; Youngs W. J.; Brody S. L.; Wooley K. L.; Cannon C. L. Synthesis, Characterization, and In Vivo Efficacy of Shell Cross-Linked Nanoparticle Formulations Carrying Silver Antimicrobials as Aerosolized Therapeutics. ACS Nano 2013, 7, 4977–4987. 10.1021/nn400322f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter A. P.; Brown J. S.; Bharti B.; Wang A.; Gangwal S.; Houck K.; Cohen Hubal E. A.; Paunov V. N.; Stoyanov S. D.; Velev O. D. An environmentally benign antimicrobial nanoparticle based on a silver-infused lignin core. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2015, 10, 817–823. 10.1038/nnano.2015.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai X.; Guo Q.; Zhao Y.; Zhang P.; Zhang T.; Zhang X.; Li C. Functional Silver Nanoparticle as a Benign Antimicrobial Agent That Eradicates Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria and Promotes Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2016, 8, 25798–25807. 10.1021/acsami.6b09267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao Y.; Ma F.; Liu C.; Zhou B.; Wei Q.; Li W.; Zhong D.; Li Y.; Zhou M. Near-Infrared Laser-Excited Nanoparticles To Eradicate Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria and Promote Wound Healing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10, 193–206. 10.1021/acsami.7b15251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahverdi A. R.; Fakhimi A.; Shahverdi H. R.; Minaian S. Synthesis and effect of silver nanoparticles on the antibacterial activity of different antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Nanomedicine 2007, 3, 168–171. 10.1016/j.nano.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khatoon N.; Alam H.; Khan A.; Raza K.; Sardar M. Ampicillin Silver Nanoformulations against Multidrug resistant bacteria. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 6848 10.1038/s41598-019-43309-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding Y.; Zhou J.; Wang S. Y.; Li Y.; Mi Y. J.; Gao S. H.; Xu Y.; Chen Y. Q.; Yan J. H. Anti-neuropilin-1 monoclonal antibody suppresses the migration and invasion of human gastric cancer cells via Akt dephosphorylation. Exp. Ther. Med. 2018, 16, 537–546. 10.3892/etm.2018.6234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J.; Li Q.; Hao X. F.; Ren X. K.; Guo J. T.; Feng Y. K.; Shi C. C. Multi-targeting peptides for gene carriers with high transfection efficiency. J. Mater. Chem. B 2017, 5, 8035–8051. 10.1039/C7TB02012K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]