Abstract

An iridium-catalyzed transfer hydrogenation of N-heteroarenes to access a series of substituted 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline derivatives in excellent yields is disclosed. This transformation is distinguished with water-soluble and air-stable iridium complexes as the catalyst, formic acid as the hydrogen source, mild reaction conditions, and broad functional group compatibility. Most importantly, a tentative chiral N,N-chelated Cp*Ir(III) complex-catalyzed enantioselective transfer hydrogenation is also presented, affording chiral products in excellent yields and good enantioselectivities.

Introduction

Reduction of N-heteroarenes to their partially or completely saturated congeners not only represents a promising method for organic synthesis for producing fine and bulk chemicals but also is a fundamentally important reaction in the petrochemical industry.1 Particularly, the reductive products 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline derivatives constitute ubiquitous motifs in an abundance of natural products, bioactive molecules, pharmaceuticals, and agrochemicals,2 for example, the natural product (−)-galipinine3 and (−)-cuspareine4 and the drug and biomolecules oxamniquine,5 paroxetine,2b and argatroban6 (Scheme 1).

Scheme 1. Representative Natural Products and Biomolecules that Contain Saturated N-Heteroarene Units.

Over the past few decades, great efforts have been devoted to develop an efficient method for synthesis of these useful 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline derivatives. Among the reported methods, the reduction of parent arenes, including catalytic hydrogenation7 and transfer hydrogenation,8 is one of the best direct strategies for synthesis of tetrahydroquinolines. Obviously, metal-participated catalytic hydrogenation, which is a fundamentally important reaction employed in industry and organic synthesis, has been widely used for the synthesis of tetrahydroquinoline derivatives, along with asymmetric hydrogenation. For example, various catalytic systems based on transition metals, such as Ru,9 Rh,10 Ir,11 Pd,12 Fe,13 and Co,14 have been applied in the hydrogenation of N-heteroarenes, which exhibit good reactivities and selectivities. However, the turnover number, turnover frequency, and substrate expansion have been considered to be important but still challenging.8f

Transfer hydrogenation has also received considerable attention due to the simple operations. In contrast to traditional hydrogenation, transfer hydrogenation makes use of alcohols,15 silane,16 hantzsch ester,17 and formic acid18 as hydrogen donors, which is widely employed in the reduction of C=O, C=N, and C=C bonds. In addition, formic acid, which is safe, accessible, and highly stable, has been used extensively.

Cyclometalated iridium complexes have been the most attractive and powerful catalysts for efficient transfer hydrogenation.19 In recent years, although tremendous achievements have been made in transfer hydrogenation of N-heteroarenes,20 the asymmetric transfer hydrogenation of N-heteroarenes displays a more difficult task due to the requisite enantiocontrol in the concurrent construction of chiral centers.21 Therefore, the development of a new and efficient catalytic system for highly enantioselective transfer hydrogenation of N-heteroarenes remains a highly desirable and challenging task.

With our continued interest in iridium complex-catalyzed transfer hydrogenation, we found that Ir–H complexes could be obtained by the decomposition of formic acid through iridium complexes.22 By designing and synthesizing a series of achiral and chiral iridium complexes, we envision that the reductive Ir–H complexes could contribute to the synthesis of tetrahydroquinolines.

Herein, we describe an efficient, practical, and convenient transfer hydrogenation of N-heteroarenes using formic acid as a hydrogen source and iridium complexes as a catalyst (Scheme 2b), providing a variety of substituted tetrahydroquinoline derivatives in excellent yields under mild reaction conditions. Meanwhile, a tentative asymmetric transfer hydrogenation is also conducted to access chiral products in excellent yields and good enantioselectivities.

Scheme 2. Reduction of N-Heteroarene Compounds.

Results and Discussion

Initial investigations began by evaluating the Ir complexes to study transfer hydrogenation of N-heteroarenes (Table 1). To our delight, TC-1 gave the desired product 2aa in the yield of 65% (entry 1). Then, different-substituted Tang’s catalysts had been screened for exploring better catalytic efficiency (entries 2–6). However, slightly decreased yields were afforded by employing TC-2–TC-618c in this catalytic system. Previous work also demonstrated that hydrogen sources played an important role in transfer hydrogenation. Next, we turned our attention to explore different hydrogen sources. As it is evident by the result compiled in Table 1, lower yields had been obtained using HCO2Na and HCO2H/NEt3 as hydrogen sources (entries 7–9). In the process of studying the reaction, we found that the substrates cannot dissolve well in the water, which may lead to low transformation in this catalytic system. Based on this, a rapid screening of organic solvents was performed. As shown in Table 1 (entries 10–15), only MeOH gave the desired product 2aa in moderate yields by evaluating the common organic solvents. A slightly increased yield of 73% was afforded by raising the temperature to 80 °C (entry 16). To further improve the reactivity of the catalyst, further optimized conditions were explored. Combining the excellent water solubility of these iridium catalysts and the good solubility of the substrates in organic solvents, we envisioned that the mixture of MeOH and H2O as a solvent can dissolve both the substrates and iridium catalyst, which may improve this catalytic efficiency. As expected, the mixed solvent was demonstrated as optimal medium (entry 17).

Table 1. Optimization of Reaction Parameters in the Iridium Complex-Catalyzed Transfer Hydrogenation of N-Heteroarenesa.

| entry | catalyst | hydrogen donor | solvent | yield/%b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | TC-1 | HCO2H | H2O | 65 |

| 2 | TC-2 | HCO2H | H2O | 60 |

| 3 | TC-3 | HCO2H | H2O | 54 |

| 4 | TC-4 | HCO2H | H2O | 58 |

| 5 | TC-5 | HCO2H | H2O | 52 |

| 6 | TC-6 | HCO2H | H2O | 53 |

| 7 | TC-1 | HCO2Na | H2O | 39 |

| 8c | TC-1 | HCO2H/Et3N | H2O | 44 |

| 9d | TC-1 | HCO2H/HCOONa | H2O | 45 |

| 10 | TC-1 | HCO2H | DMSO | <5 |

| 11 | TC-1 | HCO2H | toluene | 24 |

| 12 | TC-1 | HCO2H | THF | <5 |

| 13 | TC-1 | HCO2H | CH2Cl2 | 17 |

| 14 | TC-1 | HCO2H | MeCN | 21 |

| 15 | TC-1 | HCO2H | MeOH | 53 |

| 16e | TC-1 | HCO2H | H2O | 73 |

| 17f | TC-1 | HCO2H | H2O/MeOH | 95(92) |

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.25 mmol), solvent (2.0 mL), catalyst (1.0 mol %), and hydrogen donor (5.0 equiv) at room temperature under air for 12 h.

Determined by GC–MS using dodecane as the internal standard. The number in the parentheses is the isolated yield.

The reaction was carried out with 5.0 equiv of HCO2H and 2.0 equiv of Et3N.

The reaction was carried out with 5.0 equiv of HCOOH and 2.0 equiv of HCOONa.

The reaction was carried out at 80 °C.

H2O/MeOH = 1:1.

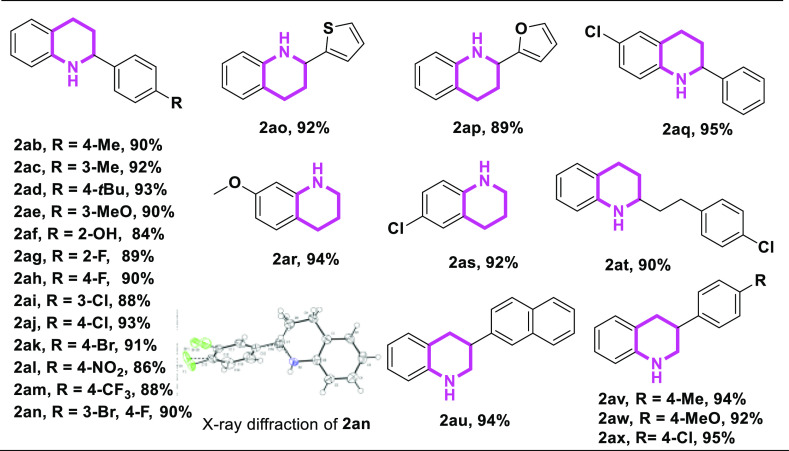

With the optimal catalytic system in hand, the substrate scope of transfer hydrogenation of N-heteroarenes was examined, the results of which are summarized in Scheme 3. Generally, various 2-aryl quinoline derivatives, including electron-donating or electron-withdrawing substituents on the phenyl group, were employed in this catalytic hydrogenation transfer reduction, affording the desired products in good to excellent yields (Table 2). For example, electron-donating substituents of methyl, methoxy, and hydroxy on the phenyl ring were well compatible in this system, delivering the corresponding products in the yields of 84–93% (2ab–2af). This catalytic system also demonstrated high activities in the halogen-substituted 2-aryl quinolines (1ag–1ak and 1an), which can achieve various N-heteroarenes through functional group transformation. In addition, strong electron-drawing substituents, such as −NO2 and −CF3, on the phenyl ring were selectively reduced to the corresponding products in the yield of 86 and 88%, respectively (2al and 2am). Notably, substrates with heterocyclic rings, such as 2-furyl and 2-thiophenyl, on quinoline conducted smoothly, delivering desired products 2ao and 2ap in high yields. Besides, different substituents on the ring of quinolines were next examined. Notably, both methoxy and chlorine groups were well tolerated (2aq–2as). At the same time, alkyl-substituted quinoline on the 2-position also worked well, leading to the reduction product 2at in 90% yield. Gratifyingly, 3-position-substituted quinoline substrates had been proven to be suitable candidates for this transformation. For instance, 1au–1ax were selectively converted to 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline products 2au–2ax in the yields of 92–95%.

Scheme 3. Gram-Scale Transformation.

Table 2. Scope of Monosubstituted N-Heteroarenes for Transfer Hydrogenationa.

Standard conditions: a solution of 1 (0.25 mmol), TC-1 (1.0 mol %), and HCOOH (5.0 equiv) in H2O (2.0 mL) and MeOH (2.0 mL) at room temperature under air for 12 h. Yield of the isolated product.

Encouraged by results with monosubstituted quinolines, we wonder whether this catalytic system could be extended to disubstituted N-heteroarenes (Table 3). Obviously, 2-aryl/alkyl and 3-aryl quinoline substrates featuring fluorine, methyl, and methoxy groups were successfully converted to the corresponding 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline congener in excellent yields (90–94%) (2ba–2bd). Except for quinolines, benzannulated quinolines, such as 1be–1bg, could also be applied in this catalytic transfer hydrogenation system, affording the corresponding hydrogenated products 2be–2bg in excellent yields.

Table 3. Substrate Scope of Disubstituted N-Heteroarenes for the Transfer Hydrogenationa.

Standard conditions: a solution of 1 (0.25 mmol), TC-1 (1.0 mol %), and HCOOH (5.0 equiv) in H2O (2.0 mL) and MeOH (2.0 mL) at room temperature under air for 12 h. Yield of the isolated product.

The relative stereochemistry of the major diastereomer was determined by NMR.

Chiral tetrahydroquinolines are prevalent scaffolds in bioactive natural products and pharmaceuticals.2 Encouraged by those promising results, we are interested in realizing the asymmetric hydrogen transformation. With abovementioned optimal reaction conditions in hand, we envisage whether chiral iridium complexes can be used as catalysts for the asymmetric catalytic conversion of this reaction. Based on this, we designed and synthesized a series of chiral iridium complexes Ir-1–Ir-5. The absolute configuration of the chiral iridium complexes Ir-1 is unambiguously confirmed by X-ray structure analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Single-crystal X-ray diffraction of chiral Ir-1 (CCDC Numbers: 2046295).

With these chiral catalysts Ir-1–Ir-5 in hand, optimization of chiral Ir catalysts was performed. Simple catalyst screening showed that the chiral catalyst Ir-1 was the optimal catalyst, which demonstrated that the introduction of the substituents into the pyridyl scaffold is unfavorable to improve the enantioselectivity (Table 4, entries 1–5). Next, an attempt of solvent screening did not have improvement on reactivities and enantioselectivities (Table 4, entries 6–9). It should be noted that when the reaction temperature was increased, the yield could be improved, but the enantioselectivity remained almost unchanged (Table 4, entries 10 and 11). To obtain better enantioselectivity, different hydrogen donors were also tested (Table 4, entries 12–14), which found that HCO2H was still the best hydrogen donor. Increasing HCO2H loading to the amount of 10.0 equiv did not improve enantioselectivity but significantly enhanced reactivity (Table 4, entry 12). Finally, evaluation of various parameters established methanol and water as optimal solvents, HCO2H as the optimal hydrogen ,donor and chiral Ir-1 as the best catalyst (Table 4, entry 15).

Table 4. Optimization of the Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of 2-Arylquinolinea.

| entry | catalyst | hydrogen donor | solvent | yield/%b | ee/%c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ir-1 | HCOOH | H2O | 71 | 65 |

| 2 | Ir-2 | HCOOH | H2O | 65 | 32 |

| 3 | Ir-3 | HCOOH | H2O | 63 | 54 |

| 4 | Ir-4 | HCOOH | H2O | 60 | 57 |

| 5 | Ir-5 | HCOOH | H2O | 54 | 10 |

| 6 | Ir-1 | HCOOH | CH3OH | 68 | 45 |

| 7 | Ir-1 | HCOOH | CH2Cl2 | 70 | 62 |

| 8 | Ir-1 | HCOOH | toluene | 54 | 60 |

| 9 | Ir-1 | HCOOH | MeCN | 45 | 59 |

| 10d | Ir-1 | HCOOH | H2O | 76 | 59 |

| 11e | Ir-1 | HCOOH | H2O | 80 | 61 |

| 12f | Ir-1 | HCOOH | H2O | 90 | 65 |

| 13 | Ir-1 | HCOONa | H2O | <5 | |

| 14g | Ir-1 | HCOOH/HCOONa | H2O | 21 | 61 |

| 15f,h | Ir-1 | HCOOH | H2O/MeOH | 95 | 66 |

Reaction conditions: 1a (0.25 mmol), solvent (2.0 mL), catalyst (1.0 mol %), and hydrogen donor (5.0 equiv) at room temperature under air for 12 h.

Determined by GC–MS using dodecane as the internal standard. The number in the parentheses is the isolated yield.

ee values were determined by HPLC with an OD-H column.

The reaction was carried out at 40 °C.

The reaction was carried out at 60 °C.

The reaction was carried out with 10.0 equiv of HCOOH.

The reaction was carried out with 5.0 equiv of HCOOH and 2.0 equiv of HCO2Na.

H2O/MeOH = 1.0/1.0 mL.

With optimal conditions in hand, the scope of the asymmetric transfer hydrogenation was examined, the results of which are summarized in Table 5. As can be seen in Table 5, all the 2-aryl-substituted substrates could be almost completely transferred into desired products with good enantioselectivities, regardless of the electronic properties of the C2 substituents, such as methyl, n-butyl, and chlorine (2ab, 2ad, 2ai, and 2aj). In addition, the thienyl on the 2-position of quinoline was compatible with this catalytic system, giving 2ao in the yield of 90 and 63% ee. However, the position of the substituent on quinoline is critical for enantioselectivity. For instance, all 3-substituted substrates afforded low enantioselectivities (1ba and 1av). It should be pointed out that 1H NMR analysis of Ir-1 in CDCl3 revealed that the diastereoselectivity of the chiral iridium center is 67:33, which definitely affected the enantioselectivity of this transfer hydrogenation reaction. Moreover, recrystallization and other strategies did not improve diastereoselectivity. More discussions and design of new chiral iridium catalysts are underway.

Table 5. Scope of the Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Substituted Quinolinea.

Standard conditions: a solution of 1 (0.25 mmol), Ir-1 (1.0 mol %), and HCOOH (5.0 equiv) in H2O (2.0 mL) and MeOH (2.0 mL) at room temperature under air for 12 h. Yield of the isolated product.

To explore the potential application, a gram-scale transformation to synthesize optical 2-(4-chlorophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2aj) was performed under standard conditions (Scheme 3). Interestingly, the optical purity of product 2aj can be increased to 99% ee by a simple recrystallization operation with CH2Cl2.

Based on the experimental results and previous study, we proposed a mechanism of 1,4-hydride addition (Scheme 4).8c,11b,23 Initially, protonation of quinolines by HCOOH was proceeded to give Int-I. Then, the Ir–H complexes, which were achieved by iridium-catalyzed decarbondioxidation of formic acid in rapid sequence, were delivered to the Int-II via a 1,4-addition fashion. Finally, protonation and 1,2-addition of isomerization quinoline gave the desired product. Notably, this mechanism explained why the asymmetric transfer hydrogenation occurred in 2-substituted quinoline to realize better enantioselectivities, compared to 3-substituted quinoline.

Scheme 4. Possible Reaction Pathways for the TH of Quinolines.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we have developed an iridium complex-catalyzed transfer hydrogenation of substituted quinolines, and a variety of highly functionalized and useful tetrahydroquinoline derivatives were afforded in excellent yields. The advantages of using an environmentally benign solvent and renewable hydride donor and purification provide great potential of practical synthesis. Moreover, this reaction can be applied to large-scale and asymmetric synthesis using chiral iridium complexes. Ongoing investigations on exploration of asymmetric transfer hydrogenation and application in the synthesis of optically active drugs with tetrahydroquinoline skeletons are in progress.

Experimental Section

General Information

1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded using a 400 MHz NMR spectrometer. Chemical shifts were reported in ppm from the solvent resonance as the internal reference (CDCl3 δH = 7.26 ppm, downfield from TMS, δC = 77.16 ppm). Gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS) was detected using electron ionization. TLC was performed using commercially prepared 100–400 mesh silica gel plates and visualization was affected at 254 nm. High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analyses were performed with an Agilent 1100 instrument using Chiralcel OD-H and Chiralpak AD-H or AS-H columns (0.46 cm diameter × 25 cm length). Optical rotations and MS spectra were recorded on a PerkinElmer polarimeter (model 341) and an ESI-ion trap mass spectrometer (Shimadzu LCMS-IT-TOF), respectively. Starting materials of all the organosilanes and alcohols were commercially available.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Substituted Quinoline Derivatives

To a stirred solution of 2-aminobenzaldehyde (1.21 g, 0.01 mol) and ketone (0.012 mol) in EtOH (20 mL) at room temperature was added KOH (2 g, 0.03 mol). The resulting mixture was then heated at reflux temperature overnight. After the mixture had cooled down to room temperature, the solvent was removed in vacuo. Then, ethyl acetate (20 mL) was added. The mixture was filtered, and the residue was washed with ethyl acetate (3 × 5 mL). The combined organic mixture was concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was purified by silica gel column chromatography (eluent: ethyl acetate/petroleum = 1/20) to give a white solid.

General Procedure for Transfer Hydrogenation of N-Heterocycles

To a 25.0 mL Schlenk tube was added the mixture of the quinolines (0.25 mmol), TC-1 catalyst (1.0 mol %, 1.4 mg), and HCOOH (5.0 equiv, 57 mg, 47 μL) in water (2.0 mL) successively. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h under air. After the reaction was completed, the mixture was diluted with H2O (15.0 mL), neutralized with NaHCO3, and extracted with EtOAc (10.0 mL × 3). The organic extract was washed with brine (10.0 mL × 3) and dried over anhydrous MgSO4. After removal of the EtOAc under vacuum, the crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel with hexanes or petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (5:1 to 50:1) to give the desired products.

General Procedure for Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of N-Heterocycles

To a 25.0 mL Schlenk tube was added the mixture of the quinolines (0.25 mmol), chiral Ir-1 catalyst (1.0 mol %, 1.7 mg), and HCOOH (10.0 equiv, 95 μL) in water (1.0 mL)/MeOH (1.0 mL) successively. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h under air. After the reaction was completed, the mixture was diluted with H2O (15.0 mL), neutralized with NaHCO3, and extracted with EtOAc (10.0 mL × 3). The organic extract was washed with brine (10.0 mL × 3) and dried over anhydrous MgSO4. After removal of the EtOAc under vacuum, the crude product was purified by column chromatography on silica gel with hexanes or petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (5:1 to 50:1) to give the desired products. The enantioselectivities were determined using an OD-H column.

General Procedure for the Synthesis of Chiral Ir-Catalysts

To a solution of ligand (4.5 mmol) in 50.0 mL of CH2Cl2 was added the powder of [Cp*IrCl2]2 (2.0 mmol). The resultant orange solution was stirred overnight. CH2Cl2 was removed under reduced pressure, and the resultant yellow solid was dissolved in a minimum amount of CH2Cl2. Then, a large amount of EtOAc slowly was added to precipitate an orange solid as the desired product, which was isolated by reduced-pressure filtration and further dried under vacuum at room temperature.

(R)-2-Phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2aa)

[α]D20 = +29.6 (c 0.43, CH2Cl2).24a Yield: 94% (49.6 mg) as a light-yellow oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.48 (ddd, J = 7.4, 5.2, 1.0 Hz, 4H), 7.43–7.36 (m, 1H), 7.17–7.07 (m, 2H), 6.78 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 1H), 6.64 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.57–4.47 (m, 1H), 4.10 (s, 1H), 3.04 (ddd, J = 15.9, 10.4, 5.2 Hz, 1H), 2.85 (dt, J = 10.2, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 2.28–2.18 (m, 1H), 2.17–2.06 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.7, 144.6, 129.2, 128.5, 127.3, 126.8, 126.5, 120.8, 117.1, 113.9, 56.1, 30.9, 26.3. The enantiomeric excess was determined by HPLC using the Daicel Chiralpak OD-H column, hexane/i-PrOH 90:10, flow rate 1.0 mL/min, UV detection at 220 nm, tminor = 9.161 min, tmajor = 11.721 min, and 63% ee.

2-(p-tolyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2ab)

[α]D20 = +2.7 (c 0.34, CH2Cl2).17a Yield: 90% (50.2 mg) as a light-yellow oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.33 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.22 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 7.05 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 6.70 (s, 1H), 6.57 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (dd, J = 9.4, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 4.32–3.75 (m, 1H), 2.95 (dd, J = 10.8, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 2.80 (dd, J = 12.8, 8.2 Hz, 1H), 2.41 (s, 3H), 2.19–2.11 (m, 1H), 2.09–1.97 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.9, 141.9, 137.1, 129.3, 129.3, 126.9, 126.5, 120.9, 117.2, 114.0, 56.1, 31.1, 26.6, 21.2. The enantiomeric excess was determined by HPLC using the Daicel Chiralpak OD-H column, hexane/i-PrOH 90:10, flow rate 1.0 mL/min, UV detection at 220 nm, tminor = 7.175 min, tmajor = 12.050 min, and 71% ee.

2-(m-Tolyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2ac)

Yield: 92% (52.3 mg) as a light-yellow oil;24c1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.31 (dd, J = 14.1, 6.3 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (dd, J = 16.5, 8.7 Hz, 4H), 6.88 (dd, J = 8.1, 2.4 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.59 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (dd, J = 9.4, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 4.36–3.90 (m, 1H), 3.85 (s, 3H), 2.97 (ddd, J = 16.3, 10.7, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 2.79 (dt, J = 16.3, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 2.16 (td, J = 8.4, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 2.10–1.96 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 159.9, 146.6, 144.7, 129.6, 129.3, 126.9, 120.9, 118.9, 117.3, 114.1, 112.8, 112.1, 56.3, 55.3, 31.0, 26.5.

2-(4-Butylphenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2ad)

[α]D20 = +5.0 (c 0.32, CH2Cl2).17a Yield: 93% (61.6 mg) as a light-yellow oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.36 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.23 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 7.07 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H), 6.71 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (dd, J = 9.4, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 4.07 (s, 1H), 2.99 (ddd, J = 16.3, 10.8, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 2.81 (dt, J = 16.3, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 2.75–2.61 (m, 2H), 2.28–2.13 (m, 1H), 2.12–1.97 (m, 1H), 1.73–1.62 (m, 2H), 1.49–1.36 (m, 2H), 1.01 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.9, 142.2, 142.0, 129.3, 128.6, 126.9, 126.5, 120.9, 117.1, 114.0, 56.1, 35.4, 33.8, 31.1, 26.6, 22.5, 14.1. The enantiomeric excess was determined by HPLC using the Daicel Chiralpak OD-H column, hexane/i-PrOH 90:10, flow rate 1.0 mL/min, UV detection at 220 nm, tminor = 5.909 min, tmajor = 6.853 min, and 80% ee.

2-(3-Methoxyphenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2ae)

Yield: 90% (53.8 mg) as a white solid (53–57 °C);24a1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.32 (t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.05 (dd, J = 16.7, 8.7 Hz, 4H), 6.95–6.82 (m, 1H), 6.70 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.45 (dd, J = 9.3, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 3.98 (dd, J = 24.6, 13.2 Hz, 1H), 3.84 (d, J = 10.8 Hz, 3H), 2.97 (ddd, J = 16.2, 10.7, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 2.79 (dt, J = 16.3, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 2.17 (ddd, J = 12.9, 8.6, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 2.05 (ddd, J = 9.3, 8.8, 4.3 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 159.9, 146.6, 144.7, 129.6, 129.4, 127.0, 120.9, 119.0, 117.3, 114.1, 112.9, 112.2, 56.3, 55.3, 31.1, 26.5.

2-(1,2,3,4-Tetrahydroquinolin-2-yl)phenol (2af)

Yield: 84% (47.2 mg) as a light-yellow oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.21 (td, J = 8.2, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.08 (ddd, J = 7.2, 4.6, 2.9 Hz, 3H), 6.96–6.81 (m, 3H), 6.71 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.40 (dd, J = 11.6, 2.7 Hz, 1H), 3.14–2.94 (m, 1H), 2.91–2.83 (m, 1H), 2.37 (ddd, J = 17.8, 12.8, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 2.14–2.05 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 156.4, 142.6, 129.8, 129.1, 128.3, 126.9, 126.7, 123.6, 120.9, 119.9, 117.4, 117.4, 57.9, 28.6, 26.7. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C15H16NO [M + H]+, 226.1232; found, 226.1232.

2-(2-Fluorophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2ag)

Yield: 89% (50.5 mg) as a colorless oil;17a1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ: δ 7.53 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.33–7.27 (m, 1H), 7.17 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 7.13–7.03 (m, 3H), 6.72 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.62 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.90 (dd, J = 8.1, 3.4 Hz, 1H), 4.42–3.69 (m, 1H), 2.99–2.89 (m, 1H), 2.74 (dt, J = 16.3, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 2.22 (ddd, J = 12.7, 9.2, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 2.11–2.02 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 160.0 (d, J = 244 Hz), 144.5, 131.7 (d, J = 13 Hz), 129.4, 128.6 (d, J = 8 Hz), 127.9 (d, J = 4 Hz), 127.0, 124.3 (d, J = 3 Hz), 120.9, 117.4, 115.3 (d, J = 22 Hz), 114.1, 48.8 (d, J = 3 Hz), 28.8, 25.7.

2-(4-Fluorophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2ah)

Yield: 90% (51.0 mg) as a colorless oil;11d1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.38 (dd, J = 8.3, 5.6 Hz, 2H), 7.05 (dd, J = 14.8, 8.0 Hz, 4H), 6.69 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.57 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (dd, J = 9.3, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 4.13 (dd, J = 111.1, 23.8 Hz, 1H), 2.95 (ddd, J = 16.2, 10.6, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 2.75 (dt, J = 16.4, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 2.12 (ddd, J = 13.0, 8.4, 4.7 Hz, 1H), 2.06–1.91 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 162.1 (d, J = 243 Hz), 144.6, 140.5 (d, J = 3 Hz), 129.4, 128.1 (d, J = 8 Hz), 127.0, 120.9, 117.4, 115.3 (d, J = 21 Hz), 114.1, 55.6, 31.2, 26.3.

2-(3-Chlorophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2ai)

[α]D20 = +13.8 (c 0.083, CH2Cl2).9a Yield: 88% (53.5 mg) as a light-yellow oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.44 (s, 1H), 7.31 (s, 3H), 7.06 (dd, J = 12.5, 7.4 Hz, 2H), 6.71 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.59 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.46 (dd, J = 9.1, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 4.40–3.41 (m, 1H), 2.95 (ddd, J = 16.0, 10.4, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 2.76 (dt, J = 16.4, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 2.15 (ddd, J = 13.3, 8.5, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.01 (ddd, J = 13.2, 9.1, 5.0 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 147.0, 144.3, 134.5, 129.9, 129.3, 127.6, 127.0, 126.8, 124.8, 120.8, 117.5, 114.1, 55.8, 31.0, 26.1. The enantiomeric excess was determined by HPLC using the Daicel Chiralpak OD-H column, hexane/i-PrOH 90:10, flow rate 1.0 mL/min, UV detection at 220 nm, tminor = 10.145 min, tmajor = 13.810 min, and 75% ee.

2-(4-Chlorophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2aj)

[α]D20 = +28.0 (c 0.17, CH2Cl2).17a Yield: 93% (56.5 mg) as a yellow solid (mp: 87–90 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.34 (s, 4H), 7.09–6.99 (m, 2H), 6.70 (d, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.57 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (dd, J = 9.1, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 4.29–3.61 (m, 1H), 2.91 (dd, J = 10.5, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 2.75 (dd, J = 13.1, 8.2 Hz, 1H), 2.16–2.07 (m, 1H), 1.99 (d, J = 4.6 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.4, 143.4, 133.0, 129.4, 128.7, 128.0, 127.0, 120.9, 117.5, 114.1, 55.6, 31.0, 26.2. The enantiomeric excess was determined by HPLC using the Daicel Chiralpak OD-H column, hexane/i-PrOH 90:10, flow rate 1.0 mL/min, UV detection at 220 nm, tminor = 10.435 min, tmajor = 18.268 min, and 81% ee.

2-(4-Bromophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2ak)

Yield: 91% (65.3 mg) as a yellow solid (mp: 83–87 °C);24a1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.50 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.30 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H), 7.12–6.97 (m, 2H), 6.70 (s, 1H), 6.59 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.45 (dd, J = 9.1, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 4.38–3.67 (m, 1H), 2.94 (ddd, J = 16.0, 10.4, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 2.75 (dt, J = 16.4, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 2.18–2.08 (m, 1H), 2.04–1.93 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.4, 143.9, 131.7, 129.4, 128.3, 127.0, 121.1, 120.8, 117.5, 114.1, 55.7, 31.0, 26.1.

2-(4-Nitrophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2al)

Yield: 86% (54.6 mg) as a colorless oil;24d1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.34–7.22 (m, 1H), 7.13–6.95 (m, 4H), 6.73 (s, 1H), 6.60 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.80 (dd, J = 9.1, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 4.31 (ddd, J = 148.3, 75.3, 43.0 Hz, 1H), 2.97 (dd, J = 10.4, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 2.85 (dd, J = 13.2, 8.2 Hz, 1H), 2.27 (dd, J = 8.9, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 2.15 (dd, J = 9.7, 4.9 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 149.0, 144.0, 129.4, 127.0, 126.7, 124.1, 123.6, 121.0, 117.8, 114.4, 52.0, 31.9, 26.2.

2-(4-(Trifluoromethyl)phenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinol-ine (2am)

Yield: 88% (60.9 mg) as a yellow oil;11d1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.60 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.50 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (dd, J = 13.4, 7.2 Hz, 2H), 6.68 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.57 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.52 (dd, J = 8.9, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (dd, J = 143.7, 32.5 Hz, 1H), 2.91 (ddd, J = 15.9, 10.2, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 2.71 (dt, J = 16.4, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.18–2.09 (m, 1H), 2.04–1.93 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 149.0, 144.3, 129.7 (q, J = 32 Hz), 129.4, 127.1, 126.9, 125.6 (q, J = 3 Hz), 124.2 (q, J = 271 Hz), 120.8, 117.6, 114.2, 55.8, 30.9, 26.0.

2-(4-Bromo-3-fluorophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2an)

Yield: 90% (69.3 mg) as a yellow solid (mp: 62–65 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.62 (dd, J = 6.6, 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.37–7.27 (m, 1H), 7.16–6.97 (m, 3H), 6.71 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.42 (dd, J = 9.2, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 4.19 (ddd, J = 115.1, 48.5, 43.5 Hz, 1H), 2.93 (ddd, J = 16.1, 10.5, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 2.74 (dt, J = 16.4, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 2.12 (ddd, J = 13.2, 8.4, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 2.02–1.91 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.2 (d, J = 254 Hz), 144.10, 142.22 (d, J = 4 Hz), 131.5, 129.2, 127.0 (d, J = 7 Hz), 126.9, 120.7, 117.6, 116.3 (d, J = 22Hz), 114.1, 108.9 (d, J = 11 Hz), 55.1, 31.0, 26.0. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C15H14NBrF [M + H]+, 306.0294; found, 306.0294.

2-(Thiophen-2-yl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2ao)

[α]D20 = +9.3 (c 0.41, CH2Cl2).11d Yield: 92% (48.4 mg) as a light-yellow oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.28 (d, J = 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.06 (dt, J = 8.6, 5.9 Hz, 4H), 6.74 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 4.80 (dd, J = 9.1, 3.2 Hz, 1H), 4.64–3.27 (m, 1H), 3.06–2.91 (m, 1H), 2.84 (dt, J = 16.4, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 2.27 (td, J = 8.2, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 2.20–2.10 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 148.9, 144.0, 129.4, 127.0, 126.7, 124.1, 123.6, 121.0, 117.8, 114.4, 52.0, 31.9, 26.2. The enantiomeric excess was determined by HPLC using the Daicel Chiralpak OD-H column, hexane/i-PrOH 90:10, flow rate 1.0 mL/min, UV detection at 220 nm, tminor = 10.191 min, tmajor = 13.024 min, and 63% ee.

2-(Furan-2-yl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2ap)

Yield: 89% (44.3 mg) as a colorless oil;9a1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ: δ 7.46–7.35 (m, 1H), 7.07–6.98 (m, 2H), 6.69 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 6.37 (dd, J = 2.9, 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.24 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 4.57 (dd, J = 8.2, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 4.45–3.23 (m, 1H), 2.90 (ddd, J = 15.3, 9.2, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 2.79 (dt, J = 16.3, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 2.27–2.14 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 157.0, 143.8, 141.7, 129.3, 126.9, 121.0, 117.6, 114.4, 110.2, 105.2, 49.7, 26.9, 25.6.

6-Chloro-2-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2aq)

[α]D20 = −6.1 (c 0.06, CH2Cl2).24e Yield: 95% (57.7 mg) as a colorless oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.44–7.28 (m, 5H), 7.11–6.88 (m, 2H), 6.47 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.44 (dd, J = 9.1, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 4.36–3.20 (m, 1H), 2.89 (ddd, J = 16.0, 10.4, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 2.71 (dt, J = 16.5, 4.9 Hz, 1H), 2.17–2.08 (m, 1H), 2.03–1.92 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.4, 143.3, 128.9, 128.7, 127.6, 126.7, 126.5, 122.4, 121.5, 115.0, 56.1, 30.5, 26.2. The enantiomeric excess was determined by HPLC using the Daicel Chiralpak OD-H column, hexane/i-PrOH 90:10, flow rate 1.0 mL/min, UV detection at 220 nm, tminor = 10.147 min, tmajor = 16.881 min, and 75% ee.

7-Methoxy-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2ar)

Yield: 94% (38.3 mg) as a colorless oil;24f1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 6.64–6.53 (m, 2H), 6.46 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 3.73 (s, 3H), 3.29–3.22 (m, 2H), 3.08 (s, 1H), 2.76 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 1.93 (dt, J = 11.9, 6.1 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 151.9, 138.8, 123.0, 115.7, 114.9, 112.9, 55.8, 42.4, 27.2, 22.5.

6-Chloro-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2as)

Yield: 92% (38.4 mg) as a light-yellow oil;24b1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 6.93 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 2H), 6.41 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (s, 1H), 3.35–3.26 (m, 2H), 2.75 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 1.98–1.89 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 143.3, 129.0, 126.5, 122.9, 121.2, 115.1, 41.9, 26.9, 21.8.

2-(4-Chlorophenethyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2at)

Yield: 90% (60.9 mg) as a light-yellow oil;24g1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.29 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.17 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.00 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 6.65 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.40–3.23 (m, 1H), 2.89–2.71 (m, 4H), 2.07–1.98 (m, 1H), 1.88–1.80 (m, 2H), 1.76–1.67 (m, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.4, 140.3, 131.7, 129.7, 129.3, 128.6, 126.8, 121.3, 117.2, 114.2, 51.0, 38.2, 31.5, 27.9, 26.2.

3-(Naphthalen-2-yl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline(2au)

Yield: 94% (60.8 mg) as a colorless oil;24h1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 8.19 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.90 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 7.77 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.50 (ddd, J = 15.4, 13.7, 7.1 Hz, 3H), 7.36 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 7.07 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 6.70 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.62 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.01 (td, J = 10.4, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 3.63 (d, J = 11.1 Hz, 1H), 3.50 (t, J = 10.7 Hz, 1H), 3.16 (qd, J = 16.0, 7.7 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.0, 139.7, 133.9, 131.6, 129.6, 129.1, 127.1, 126.2, 125.7, 125.6, 123.0, 122.8, 121.7, 117.3, 114.3, 48.2, 34.6, 33.4.

3-(p-Tolyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2av)

Yield: 94% (52.4 mg) as a colorless oil;24b1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.26–7.19 (m, 4H), 7.09 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 6.73 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.62 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 3.81 (dd, J = 104.5, 26.1 Hz, 1H), 3.54–3.46 (m, 1H), 3.38 (t, J = 10.7 Hz, 1H), 3.25–3.14 (m, 1H), 3.06 (t, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 2.43 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.1, 140.9, 136.3, 129.6, 129.4, 127.2, 127.0, 121.5, 117.1, 114.1, 48.5, 38.3, 34.8, 21.1.

3-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2aw)

[α]D20 = +6.5 (c 0.09, CH2Cl2).24b Yield: 92% (55.0 mg) as a colorless oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.20 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 7.05 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H), 6.93 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 2H), 6.69 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 3.84 (s, 3H), 3.49–3.42 (m, 1H), 3.32 (t, J = 10.7 Hz, 1H), 3.14 (tdd, J = 10.1, 6.2, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 3.05–2.94 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.4, 144.1, 136.0, 129.59, 128.16, 127.00, 121.45, 117.12, 114.08, 114.07, 55.33, 48.62, 37.83, 34.82. The enantiomeric excess was determined by HPLC using the Daicel Chiralpak OD-H column, hexane/i-PrOH 90:10, flow rate 1.0 mL/min, UV detection at 220 nm, tminor = 11.696 min, tmajor = 14.063 min, and 9% ee.

3-(4-Chlorophenyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2ax)

Yield: 95% (57.7 mg) as a white solid (mp: 104–107 °C);24b1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.33 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.20 (d, J = 8.3 Hz, 2H), 7.09–6.99 (m, 2H), 6.69 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 3.76 (dd, J = 101.8, 29.7 Hz, 1H), 3.46 (dd, J = 11.1, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 3.32 (t, J = 10.6 Hz, 1H), 3.21–3.09 (m, 1H), 3.00 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 143.9, 142.4, 132.4, 129.6, 128.8, 128.6, 127.1, 121.0, 117.3, 114.2, 48.2, 38.1, 34.5.

3-(4-Fluorophenyl)-2-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinol-ine (2ba)

[α]D20 = −11.4 (c 0.035, CH2Cl2). Yield: 94% (71.2 mg) as a colorless oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ: δ 7.13 (ddd, J = 10.6, 6.2, 2.3 Hz, 5H), 6.89–6.70 (m, 7H), 6.64 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.72 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.51 (td, J = 7.1, 4.2 Hz, 1H), 3.06 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 162.0 (d, J = 244 Hz), 144.0, 141.0, 137.4 (d, J = 3 Hz), 129.6, 129.1 (d, J = 8 Hz), 128.7, 127.9, 127.3, 126.6, 120.5, 117.5, 114.4 (d, J = 21 Hz), 113.7, 59.7, 43.4, 29.4. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C21H19NF [M + H]+, 304.1502; found, 304.1505. The enantiomeric excess was determined by HPLC using the Daicel Chiralpak OD-H column, hexane/i-PrOH 90:10, flow rate 1.0 mL/min, UV detection at 220 nm, tminor = 11.678 min, tmajor = 12.925 min, and 12% ee.

3-(4-Methoxyphenyl)-2-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquino-line (2bb)

Yield: 93% (73.2 mg) as a colorless oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.18 (dd, J = 5.0, 1.7 Hz, 3H), 7.10 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 2H), 6.86 (dd, J = 6.5, 2.8 Hz, 2H), 6.73 (dd, J = 12.4, 5.3 Hz, 3H), 6.65 (dd, J = 12.2, 8.3 Hz, 3H), 4.69 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 1H), 4.57–3.96 (m, 1H), 3.76 (s, 3H), 3.52 (td, J = 7.1, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 3.08 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.7, 144.4, 141.4, 133.9, 129.5, 128.9, 128.7, 127.8, 127.2, 126.5, 120.6, 117.2, 113.7, 113.0, 59.8, 55.2, 43.5, 29.7. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C22H22NO [M + H]+, 316.1701; found, 316.1696.

2-Phenyl-3-(p-tolyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2bc)

Yield: 90% (67.2 mg) as a yellow solid (mp: 118–121 °C); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.24–7.08 (m, 5H), 6.99 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 2H), 6.85 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H), 6.76 (dd, J = 7.2, 5.4 Hz, 3H), 6.65 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 4.74 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H), 4.66–3.98 (m, 1H), 3.67–3.44 (m, 1H), 3.22–2.92 (m, 2H), 2.33 (s, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 144.4, 141.9, 138.2, 136.0, 129.6, 128.6, 128.5, 127.7, 127.6, 127.2, 127.1, 120.7, 117.3, 113.7, 60.4, 43.0, 29.8, 21.1. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C22H22N [M + H]+, 300.1752; found, 300.1753.

2-Benzyl-3-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinoline (2bd)

Yield: 92% (54.5 mg) as a colorless oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.34 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 2H), 7.30–7.25 (m, 1H), 7.21 (d, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 7.04 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.96 (d, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.67 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 6.54 (d, J = 7.9 Hz, 1H), 3.57 (qd, J = 6.5, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 2.82–2.72 (m, 2H), 2.55 (ddd, J = 19.8, 15.0, 8.5 Hz, 2H), 2.34–2.22 (m, 1H), 1.26 (d, J = 6.6 Hz, 3H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 143.9, 140.9, 129.9, 129.2, 128.4, 126.8, 125.9, 119.9, 117.1, 114.1, 49.3, 38.1, 35.7, 30.1, 17.6. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C17H20N [M + H]+, 238.1596; found, 316.1594.

6a,7,12,12a-Tetrahydro-6H-chromeno[4,3-b]quinoline (2be)

Yield: 89% (52.8 mg) as a colorless oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.26 (dd, J = 13.9, 6.6 Hz, 2H), 7.02 (t, J = 7.3 Hz, 2H), 6.97–6.86 (m, 2H), 6.66 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.50 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H), 4.43 (d, J = 3.4 Hz, 1H), 4.16 (dd, J = 12.7, 8.3 Hz, 2H), 3.19 (dd, J = 17.0, 6.4 Hz, 1H), 2.69 (dd, J = 17.0, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 2.54 (ddd, J = 10.2, 6.6, 3.8 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 153.9, 141.7, 129.4, 129.4, 129.1, 127.2, 124.0, 120.4, 118.1, 117.4, 116.9, 113.8, 66.3, 48.4, 29.4, 27.5. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C16H16NO [M + H]+, 238.1232; found, 238.1238.

4-Benzyl-1,2,3,4,4a,9,9a,10-octahydroacridine (2bf)

Yield: 90% (62.3 mg) as a colorless oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.29 (dd, J = 10.5, 4.0 Hz, 2H), 7.22 (d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 7.17 (d, J = 7.0 Hz, 2H), 6.98 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 2H), 6.61 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 1H), 6.42 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 3.19 (dd, J = 6.8, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 2.98 (dd, J = 13.4, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 2.74 (dd, J = 9.2, 7.1 Hz, 2H), 2.51 (dd, J = 13.3, 9.1 Hz, 1H), 2.32–2.24 (m, 1H), 1.88 (dd, J = 7.1, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 1.72 (ddd, J = 14.1, 7.2, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 1.66–1.50 (m, 4H), 1.15 (ddd, J = 13.7, 8.0, 4.4 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 143.4, 141.0, 129.5, 129.1, 128.3, 126.7, 125.9, 119.9, 116.4, 113.3, 55.6, 41.0, 38.6, 31.5, 30.5, 30.2, 28.7, 20.4. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C20H24N [M + H]+, 278.1909; found, 278.1912.

7-Chloro-1,2,3,4,4a,9,9a,10-octahydroacridine (2bg)

Yield: 91% (50.3 mg) as a colorless oil; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 6.92 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H), 6.42–6.35 (m, 1H), 3.54–3.49 (m, 1H), 2.89 (dd, J = 16.4, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 2.50 (dd, J = 16.4, 3.9 Hz, 1H), 1.96 (d, J = 3.8 Hz, 1H), 1.67 (ddd, J = 18.2, 8.7, 6.1 Hz, 4H), 1.47–1.36 (m, 4H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 142.5, 129.2, 126.4, 120.9, 120.6, 114.2, 50.0, 32.6, 32.5, 31.6, 27.1, 24.7, 20.6. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C13H17NCl [M + H]+, 222.1050; found, 222.1059.

Chiral Ir-1

Yield solid (mp: 252–256 °C), 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 10.99 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 9.32 (dd, J = 22.2, 6.6 Hz, 1H), 8.79 (dd, J = 43.2, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 7.96 (d, J = 6.4 Hz, 1H), 7.71 (s, 1H), 7.39–7.14 (m, 10H), 5.26–4.71 (m, 4H), 1.34 (d, J = 12.3 Hz, 15H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.4, 168.9, 151.5, 151.3, 147.6, 146.7, 141.8, 140.9, 140.2, 140.0, 139.2, 138.4, 130.0, 129.6, 129.1, 129.0, 128.8, 128.6, 128.5, 128.3, 128.1, 128.0, 126.9, 126.6, 126.3, 88.2, 87.7, 79.2, 79.0, 72.1, 72.0, 53.6, 9.2, 9.0. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C31H35N3ClIr [M + H]+, 677.2141; found, 677.2149.

Chiral Ir-2

Yield solid. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 10.64 (s, 1H), 8.83 (s, 1H), 8.01 (s, 1H), 7.25 (d, J = 17.9 Hz, 13H), 4.93 (d, J = 81.0 Hz, 2H), 4.10 (s, 3H), 1.35 (d, J = 16.7 Hz, 16H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.6, 163.7, 144.5, 143.8, 140.1, 138.9, 129.1, 128.4, 127.7, 126.6, 120.9, 112.1, 88.4, 87.5, 79.6, 71.6, 71.1, 58.9, 58.0, 10.0, 9.7. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C32H37N3OClIr [M + H]+, 707.2254; found, 707.2254.

Chiral Ir-3

Yield solid (mp: 241–253 °C). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 10.76 (s, 1H), 9.14 (d, J = 29.6 Hz, 1H), 8.56 (dd, J = 45.2, 5.1 Hz, 1H), 7.51–7.11 (m, 13H), 5.08–4.97 (m, 1H), 4.86 (dd, J = 41.5, 7.0 Hz, 1H), 2.43 (d, J = 24.5 Hz, 3H), 1.32 (d, J = 13.2 Hz, 15H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.5, 169.0, 153.2, 152.9, 150.5, 150.3, 147.0, 146.2, 141.7, 140.9, 139.2, 139.1, 138.5, 130.6, 130.3, 129.1, 129.0, 128.9, 128.8, 128.7, 128.5, 128.5, 128.2, 126.8, 126.5, 126.2, 87.9, 87.5, 79.2, 78.9, 72.0, 9.2, 9.0. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C32H37N3ClIr [M + H]+, 691.2307; found, 691.2305.

Chiral Ir-4

Yield solid (mp: 272–278 °C). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 11.07 (d, J = 14.5 Hz, 1H), 9.50 (d, J = 39.3 Hz, 1H), 8.84 (dd, J = 68.1, 5.0 Hz, 1H), 7.84 (dd, J = 17.7, 5.4 Hz, 1H), 7.49–7.05 (m, 12H), 5.16–5.02 (m, 1H), 4.99–4.84 (m, 1H), 1.37 (d, J = 13.1 Hz, 15H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 168.8, 168.3, 152.7, 152.2, 148.6, 148.5, 148.1, 147.7, 141.5, 140.8, 139.0, 138.4, 130.5, 130.2, 129.1, 128.8, 128.6, 128.5, 128.4, 126.9, 126.5, 126.3, 88.4, 88.0, 79.4, 79.0, 72.2, 72.1, 9.3, 9.1. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C31H34N3Cl2Ir [M + H]+, 711.1761; found, 711.1759.

Chiral Ir-5

Yield solid (mp: 196–208 °C). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 11.23 (s, 1H), 9.37 (d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 8.46 (dd, J = 35.0, 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.96 (d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.88–7.82 (m, 1H), 7.73 (t, J = 6.8 Hz, 1H), 7.38–7.18 (m, 13H), 5.28 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 5.04 (d, J = 10.0 Hz, 1H), 1.34 (s, 15H). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3): δ 169.4, 147.5, 145.6, 141.7, 139.7, 138.2, 132.2, 130.7, 130.2, 130.1, 129.2, 129.2, 128.6, 128.5, 128.5, 128.0, 126.4, 122.8, 88.0, 79.1, 71.0, 9.4. HRMS-ESI (m/z): calcd for C35H37N3ClIr [M + H]+, 727.2308; found, 727.2305.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (21962004 and 21562004), Jiangxi provincial department of science and technology (20192BAB203004), the emergency research project for Gannan Medical University (YJ202027), and the Fundamental Research Funds for Gannan Medical University (QD201810) for financial support.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c00868.

NMR spectra for all products (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- a Topsoe H.; Clausen B. S.; Massoth F. E.. Hydrotreating Catalysis, Science and Technology; Springer-Verlag: Heidelberg, Germany, 1996; [Google Scholar]; b Toshiaki K.; Atsushi I.; Weihua Q.. Hydrodesulfurization and Hydrodenitrogenation: Chemistry and Engineering; Wiley-VCH: Tokyo, 1999; [Google Scholar]; c Rylander P.The Catalytic Hydrogenation in Organic Syntheses; Academic Press: London, 1979; pp 213–234; [Google Scholar]; d Nishimura S.Handbook of Heterogeneous Catalytic Hydrogenations for Organic Synthesis; Wiley: New York, 2001; pp 497–571. [Google Scholar]

- a Pica-Mattoccia L.; Cioli D. Studies on the Mode of Action of Oxamniquine and Related Schistosomicidal Drugs. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 1985, 34, 112–118. 10.4269/ajtmh.1985.34.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Katzman M. A. Current Considerations in the Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder. CNS Drugs 2009, 23, 103–120. 10.2165/00023210-200923020-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Naoi M.; Maruyama W.; Nagy G. M. Dopamine-Derived Salsolinol Derivatives as Endogenous Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors: Occurrence, Metabolism and Function in Human Brains. Neurotoxicology 2004, 25, 193–204. 10.1016/s0161-813x(03)00099-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Katritzky A. R.; Rachwal S.; Rachwal B. Recent Progress in the Synthesis of 1,2,3,4,-Tetrahydroquinolines. Tetrahedron 1996, 52, 15031–15070. 10.1016/s0040-4020(96)00911-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Scott J. D.; Williams R. M. Chemistry and Biology of the Tetrahydroisoquinoline Antitumor Antibiotics. Chem. Rev. 2002, 102, 1669–1730. 10.1021/cr010212u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sridharan V.; Suryavanshi P. A.; Menéndez J. C. Advances in the Chemistry of Tetrahydroquinolines. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 7157–7259. 10.1021/cr100307m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houghton P. J.; Woldemariam T. Z.; Watanabe Y.; Yates M. Activity Against Mycobacterium tuberculosis of Alkaloid Constituents of Angostura Bark, Galipea officinalis. Planta Med. 1999, 65, 250–254. 10.1055/s-1999-13988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filho R. P.; de Souza Menezes C. M.; Pinto P. L. S.; Paula G. A.; Brandt C. A.; da Silveira M. A. B. Design, Synthesis, and in vivo Evaluation of Oxamniquine Methacrylate and Acrylamide Prodrugs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2007, 15, 1229–1236. 10.1016/j.bmc.2006.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann M.; Baxendale I. R. An Overview of the Synthetic Routes to the Best Selling Drugs Containing 6-Membered Heterocycles. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2013, 9, 2265–2319. 10.3762/bjoc.9.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang D.-S.; Chen Q.-A.; Lu S.-M.; Zhou Y.-G. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Heteroarenes and Arenes. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 2557–2590. 10.1021/cr200328h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b He Y.-M.; Song F.-T.; Fan Q.-H. Advances in Transition Metal-Catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Heteroaromatic Compounds. Top. Curr. Chem. 2013, 343, 145–190. 10.1007/128_2013_480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Glorius F. Asymmetric hydrogenation of aromatic compounds. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2005, 3, 4171–4175. 10.1039/b512139f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Zhou Y.-G. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Heteroaromatic Compounds. Acc. Chem. Res. 2007, 40, 1357–1366. 10.1021/ar700094b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Wang D.-S.; Chen Q.-A.; Lu S.-M.; Zhou Y.-G. Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Heteroarenes and Arenes. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 2557–2590. 10.1021/cr200328h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Giustra Z. X.; Ishibashi J. S. A.; Liu S.-Y. Homogeneous metal catalysis for conversion between aromatic and saturated compounds. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2016, 314, 134–181. 10.1016/j.ccr.2015.11.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Brieger G.; Nestrick T. J. Catalytic transfer hydrogenation. Chem. Rev. 1974, 74, 567–580. 10.1021/cr60291a003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Bäckvall J.-E. Transition Metal Hydrides as Active Intermediates in Hydrogen Transfer Reactions. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002, 652, 105–111. 10.1016/s0022-328x(02)01316-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Gladiali S.; Alberico E. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation: Chiral Ligands and Applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 226–236. 10.1039/b513396c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Samec J. S. M.; Bäckvall J.-E.; Andersson P. G.; Brandt P. Mechanistic Aspects of Transition Metal-Catalyzed Hydrogen Transfer Reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2006, 35, 237–248. 10.1039/b515269k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Wang D.; Astruc D. The Golden Age of Transfer Hydrogenation. Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 6621–6686. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Talwar D.; Li H. Y.; Durham E.; Xiao J. A Simple Iridicycle Catalyst for Efficient Transfer Hydrogenation of N-Heterocycles in Water. Chem.—Eur. J. 2015, 21, 5370–5379. 10.1002/chem.201500016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Grozavu A.; Hepburn H. B.; Smith P. J.; Potukuchi H. K.; Lindsay-Scott P. J.; Donohoe T. J. The Reductive C3 Functionalization of Pyridinium and Quinolinium Salts Through Iridium-Catalysed Interrupted Transfer Hydrogenation. Nat. Chem. 2019, 11, 242–247. 10.1038/s41557-018-0178-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Wang Y.; Huang Z.; Leng X.; Zhu H.; Liu G.; Huang Z. Transfer Hydrogenation of Alkenes Using Ethanol Catalyzed by a NCP Pincer Iridium Complex: Scope and Mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 4417–4429. 10.1021/jacs.8b01038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Cabrero-Antonino J. R.; Adam R.; Junge K.; Jackstell R.; Beller M. Cobalt-Catalysed Transfer Hydrogenation of Quinolines and Related Heterocycles Using Formic Acid under Mild Conditions. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 1981–1985. 10.1039/c7cy00437k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; j Alshakov I. D.; Gabidullin B.; Nikonov G. I. Ru-Catalyzed Transfer Hydrogenation of Nitriles, Aromatics, Olefins, Alkynes and Esters. ChemCatChem 2018, 10, 4860–4869. 10.1002/cctc.201801039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang T.; Zhuo L.-G.; Li Z.; Chen F.; Ding Z.; He Y.; Fan Q.-H.; Xiang J.; Yu Z.-X.; Chan A. S. C. Highly Enantioselective Hydrogenation of Quinolines Using Phosphine-Free Chiral Cationic Ruthenium Catalysts: Scope, Mechanism, and Origin of Enantioselectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 9878–9891. 10.1021/ja2023042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Kuwano R.; Ikeda R.; Hirasada K. Catalytic Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Quinoline Carbocycles: Unusual Chemoselectivity in the Hydrogenation of Quinolines. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 7558–7561. 10.1039/c5cc01971k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ma W.; Zhang J.; Xu C.; Chen F.; He Y.-M.; Fan Q.-H. Highly Enantioselective Direct Synthesis of Endocyclic Vicinal Diamines through Chiral Ru(diamine)-Catalyzed Hydrogenation of 2,2′-Bisquinoline Derivatives. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 12891–12894. 10.1002/anie.201608181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang C.; Li C.; Wu X.; Pettman A.; Xiao J. pH-Regulated Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Quinolines in Water. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6524–6528. 10.1002/anie.200902570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wen J.; Tan R.; Liu S.; Zhao Q.; Zhang X. Strong Brønsted acid promoted asymmetric hydrogenation of isoquinolines and quinolines catalyzed by a Rh-thiourea chiral phosphine complex via anion binding. Chem. Sci. 2016, 7, 3047–3051. 10.1039/c5sc04712a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wu J.; Barnard J. H.; Zhang Y.; Talwar D.; Robertson C. M.; Xiao J. Robust Cyclometallated Ir(iii) Catalysts for The Homogeneous Hydrogenation of N-Heterocycles under Mild Conditions. Chem. Commun. 2013, 49, 7052–7054. 10.1039/c3cc44567d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b John J.; Wilson-Konderka C.; Metallinos C. Low Pressure Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Quinolines using an Annulated Planar ChiralN-Ferrocenyl NHC-Iridium Complex. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2015, 357, 2071–2081. 10.1002/adsc.201500105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Kuwano R.; Hashiguchi Y.; Ikeda R.; Ishizuka K. Catalytic Asymmetric Hydrogenation of Pyrimidines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 2393–2396. 10.1002/anie.201410607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wang S.; Huang H.; Bruneau C.; Fischmeister C. Iridium-Catalyzed Hydrogenation and Dehydrogenation of N-Heterocycles in Water under Mild Conditions. ChemSusChem 2019, 12, 2350–2354. 10.1002/cssc.201802275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X.-F.; Huang W.-X.; Chen Z.-P.; Zhou Y.-G. Palladium-catalyzed Asymmetric Hydrogenation of 3-Phthalimido Substituted Quinolines. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 9588–9590. 10.1039/c4cc04386c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Sahoo B.; Kreyenschulte C.; Agostini G.; Lund H.; Bachmann S.; Scalone M.; Junge K.; Beller M. A Robust Iron Catalyst for the Selective Hydrogenation of Substituted (iso)Quinolones. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 8134–8141. 10.1039/c8sc02744g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chakraborty S.; Brennessel W. W.; Jones W. D. A Molecular Iron Catalyst for the Acceptorless Dehydrogenation and Hydrogenation of N-Heterocycles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 8564–8567. 10.1021/ja504523b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Xu R.; Chakraborty S.; Yuan H.; Jones W. D. Acceptorless, Reversible Dehydrogenation and Hydrogenation of N-Heterocycles with a Cobalt Pincer Catalyst. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 6350–6354. 10.1021/acscatal.5b02002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Sorribes I.; Liu L.; Doménech-Carbó A.; Corma A. Nanolayered Cobalt-Molybdenum Sulfides as Highly Chemo- and Regioselective Catalysts for the Hydrogenation of Quinoline Derivatives. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 4545–4557. 10.1021/acscatal.7b04260. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Adam R.; Cabrero-Antonino J. R.; Spannenberg A.; Junge K.; Jackstell R.; Beller M. A General and Highly Selective Cobalt-Catalyzed Hydrogenation of N-Heteroarenes under Mild Reaction Conditions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 3216–3220. 10.1002/anie.201612290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yang F.; Chen J.; Shen G.; Zhang X.; Fan B. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation Reactions of N-Sulfonylimines by Using Alcohols as Hydrogen Sources. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 4963–4966. 10.1039/c8cc01284a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Pan H.-J.; Zhang Y.; Shan C.; Yu Z.; Lan Y.; Zhao Y. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Imines using Alcohol: Efficiency and Selectivity are Influenced by the Hydrogen Donor. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 9615–9619. 10.1002/anie.201604025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Garg N.; Paira S.; Sundararaju B. Efficient Transfer Hydrogenation of Ketones using Methanol as Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carrier. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 3472–3476. 10.1002/cctc.202000228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Sloane S. E.; Reyes A.; Vang Z. P.; Li L.; Behlow K. T.; Clark J. R. Copper-Catalyzed Formal Transfer Hydrogenation/Deuteration of Aryl Alkynes. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 9139–9144. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c03632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Clark E. R.; Ingleson M. J. N-Methylacridinium Salts: Carbon Lewis Acids in Frustrated Lewis Pairs for σ-Bond Activation and Catalytic Reductions. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 11306–11309. 10.1002/anie.201406122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Luo N.; Liao J.; Ouyang L.; Wen H.; Zhong Y.; Liu J.; Tang W.; Luo R. Highly Selective Hydroxylation and Alkoxylation of Silanes: One-Pot Silane Oxidation and Reduction of Aldehydes/Ketones. Organometallics 2020, 39, 165–171. 10.1021/acs.organomet.9b00716. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Aboo A. H.; Bennett E. L.; Deeprose M.; Robertson C. M.; Iggo J. A.; Xiao J. Methanol as Hydrogen Source: Transfer Hydrogenation of Aromatic Aldehydes with a Rhodacycle. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 11805–11808. 10.1039/c8cc06612d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Qiao X.; Bao Z.; Xing H.; Yang Y.; Ren Q.; Zhang Z. Organocatalytic Approach for Transfer Hydrogenation of Quinolines, Benzoxazines and Benzothiazines. Catal. Lett. 2017, 147, 1673–1678. 10.1007/s10562-017-2061-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Pastor J.; Rezabal E.; Voituriez A.; Betzer J.-F.; Marinetti A.; Frison G. Revised Theoretical Model on Enantiocontrol in Phosphoric Acid Catalyzed H-Transfer Hydrogenation of Quinoline. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 2779–2787. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b03248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c He R.; Cui P.; Pi D.; Sun Y.; Zhou H. High Efficient Iron-Catalyzed Transfer Hydrogenation of Quinolines with Hantzsch Ester as Hydrogen Source under Mild Conditions. Tetrahedron Lett. 2017, 58, 3571–3573. 10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.07.101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Cai X.-F.; Guo R.-N.; Feng G.-S.; Wu B.; Zhou Y.-G. Chiral Phosphoric Acid-Catalyzed Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Quinolin-3-amines. Org. Lett. 2014, 16, 2680–2683. 10.1021/ol500954j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Murayama H.; Heike Y.; Higashida K.; Shimizu Y.; Yodsin N.; Wongnongwa Y.; Jungsuttiwong S.; Mori S.; Sawamura M. Iridium-Catalyzed Enantioselective Transfer Hydrogenation of Ketones Controlled by Alcohol Hydrogen-Bonding and sp 3 -C–H Noncovalent Interactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 362, 4655–4661. 10.1002/adsc.202000615. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Liu J.-T.; Yang S.; Tang W.; Yang Z.; Xu J. Iridium-Catalyzed Efficient Reduction of Ketones in Water with Formic Acid as a Hydride Donor at Low Catalyst Loading. Green Chem. 2018, 20, 2118–2124. 10.1039/c8gc00348c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Yang Z.; Zhu Z.; Luo R.; Qiu X.; Liu J.-T.; Yang J.-K.; Tang W. Iridium-Catalyzed Highly Efficient Chemoselective Reduction of Aldehydes in Water Using Formic Acid as The Hydrogen Source. Green Chem. 2017, 19, 3296–3301. 10.1039/c7gc01289f. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Smith J.; Kacmaz A.; Wang C.; Villa-Marcos B.; Xiao J. Chiral Cyclometalated Iridium Complexes for Asymmetric Reduction Reactions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2020, 19, 279. 10.1039/D0OB02049D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Pan Y.; Luo Z.; Xu X.; Zhao H.; Han J.; Xu L.; Fan Q.; Xiao J. Ru-Catalyzed Deoxygenative Transfer Hydrogenation of Amides to Amines with Formic Acid/Triethylamine. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2019, 361, 3800–3806. 10.1002/adsc.201900406. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Tan Z.; Fu Z.; Yang J.; Wu Y.; Cao L.; Jiang H.; Li J.; Zhang M. Hydrogen Transfer-Mediated Multicomponent Reaction for Direct Synthesis of Quinazolines by a Naphthyridine-Based Iridium Catalyst. iScience 2020, 23, 101003. 10.1016/j.isci.2020.101003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang R.; Han X.; Xu J.; Liu P.; Li F. Transfer Hydrogenation of Ketones and Imines with Methanol under Base-Free Conditions Catalyzed by an Anionic Metal-Ligand Bifunctional Iridium Catalyst. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 85, 2242–2249. 10.1021/acs.joc.9b02957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Garg N.; Paira S.; Sundararaju B. Efficient Transfer Hydrogenation of Ketones using Methanol as Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carrier. ChemCatChem 2020, 12, 3472–3476. 10.1002/cctc.202000228. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Albrecht M. Cyclometalation Using d-Block Transition Metals: Fundamental Aspects and Recent Trends. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 576–623. 10.1021/cr900279a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Michon C.; MacIntyre K.; Corre Y.; Agbossou-Niedercorn F. Pentamethylcyclopentadienyl Iridium(III) Metallacycles Applied to Homogeneous Catalysis for Fine Chemical Synthesis. ChemCatChem 2016, 8, 1755–1762. 10.1002/cctc.201600238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Stüker T.; Beckers H.; Riedel S. A Cornucopia of Iridium Nitrogen Compounds Produced from Laser-Ablated Iridium Atoms and Dinitrogen. Chem.—Eur. J. 2020, 26, 7384–7394. 10.1002/chem.201905514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Chen F.; Sahoo B.; Kreyenschulte C.; Lund H.; Zeng M.; He L.; Junge K.; Beller M. Selective Cobalt Nanoparticles for Catalytic Transfer Hydrogenation of N-Heteroarenes. Chem. Sci. 2017, 8, 6239–6246. 10.1039/c7sc02062g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Cabrero-Antonino J. R.; Adam R.; Junge K.; Jackstell R.; Beller M. Cobalt-Catalysed Transfer Hydrogenation of Quinolines and Related Heterocycles using Formic Acid under Mild Conditions. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2017, 7, 1981–1985. 10.1039/c7cy00437k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Guan R.; Zhao H.; Cao L.; Jiang H.; Zhang M. Ruthenium/acid co-catalyzed reductive α-phosphinoylation of 1,8-naphthyridines with diarylphosphine oxides. Org. Chem. Front. 2020, 8, 106. 10.1039/D0QO01284J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhou G.; Aboo A. H.; Robertson C. M.; Liu R.; Li Z.; Luzyanin K.; Berry N. G.; Chen W.; Xiao J. N,O- vs N,C-Chelation in Half-Sandwich Iridium Complexes: A Dramatic Effect on Enantioselectivity in Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Ketones. ACS Catal. 2018, 8, 8020–8026. 10.1021/acscatal.8b02068. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Li S.; Meng W.; Du H. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenations of 2,3-Disubstituted Quinoxalines with Ammonia Borane. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 2604–2606. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Barrios-Rivera J.; Xu Y.; Wills M. Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Unhindered and Non-Electron-Rich 1-Aryl Dihydroisoquinolines with High Enantioselectivity. Org. Lett. 2020, 22, 6283–6287. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wang C.; Li C.; Wu X.; Pettman A.; Xiao J. pH-Regulated Asymmetric Transfer Hydrogenation of Quinolines in Water. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 6524–6528. 10.1002/anie.200902570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Li J.; Li J.; Zhang D.; Liu C. DFT Study on the Mechanism of Formic Acid Decomposition by a Well-Defined Bifunctional Cyclometalated Iridium(III) Catalyst: Self-Assisted Concerted Dehydrogenation via Long-Range Intermolecular Hydrogen Migration. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 4746–4754. 10.1021/acscatal.6b00564. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Mellmann D.; Sponholz P.; Junge H.; Beller M. Formic acid as a hydrogen storage material - development of homogeneous catalysts for selective hydrogen release. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2016, 45, 3954–3988. 10.1039/c5cs00618j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wang Z.; Lu S.-M.; Li J.; Wang J.; Li C. Unprecedentedly High Formic Acid Dehydrogenation Activity on an Iridium Complex with anN,N′-Diimine Ligand in Water. Chem.—Eur. J. 2015, 21, 12592–12595. 10.1002/chem.201502086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Luo N.; Liao J.; Ouyang L.; Wen H.; Liu J.; Tang W.; Luo R. Highly pH-Dependent Chemoselective Transfer Hydrogenation of α,β-Unsaturated Aldehydes in Water. Organometallics 2019, 38, 3025–3031. 10.1021/acs.organomet.9b00353. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Ouyang L.; Xia Y.; Liao J.; Luo R. One-Pot Transfer Hydrogenation Reductive Amination of Aldehydes and Ketones by Iridium Complexes “on Water”. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2020, 2020, 6387–6391. 10.1002/ejoc.202001097. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Dobereiner G. E.; Nova A.; Schley N. D.; Hazari N.; Miller S. J.; Eisenstein O.; Crabtree R. H. Iridium-Catalyzed Hydrogenation of N-Heterocyclic Compounds under Mild Conditions by an Outer-Sphere Pathway. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 7547–7562. 10.1021/ja2014983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Casey C. P.; Johnson J. B.; Singer S. W.; Cui Q. Hydrogen Elimination from a Hydroxycyclopentadienyl Ruthenium(II) Hydride: Study of Hydrogen Activation in a Ligand–Metal Bifunctional Hydrogenation Catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 3100–3109. 10.1021/ja043460r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Privalov T.; Samec J. S. M.; Bäckvall J.-E. DFT Study of an Inner-Sphere Mechanism in the Hydrogen Transfer from a Hydroxycyclopentadienyl Ruthenium Hydride to Imines. Organometallics 2007, 26, 2840–2848. 10.1021/om070169m. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Nova A.; Balcells D.; Schley N. D.; Dobereiner G. E.; Crabtree R. H.; Eisenstein O. An Experimental–Theoretical Study of the Factors That Affect the Switch between Ruthenium-Catalyzed Dehydrogenative Amide Formation versus Amine Alkylation. Organometallics 2010, 29, 6548–6558. 10.1021/om101015u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Li X.; Tian J. J.; Liu N.; Tu X. S.; Zeng N. N.; Wang X. C. Spiro-Bicyclic Bisborane Catalysts for Metal-Free Chemoselective and Enantioselective Hydrogenation of Quinolines. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 4664–4668. 10.1002/anie.201900907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang Y.; Dong B.; Wang Z.; Cong X.; Bi X. Silver-Catalyzed Reduction of Quinolines in Water. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 3631–3634. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b01055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Paria S.; Pirtsch M.; Kais V.; Reiser O. Visible-Light-Induced Intermolecular Atom-Transfer Radical Addition of Benzyl Halides to Olefins: Facile Synthesis of Tetrahydroquinolines. Synthesis 2013, 45, 2689–2698. 10.1055/s-0033-1338910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Iosub A. V.; Stahl S. S. Catalytic Aerobic Dehydrogenation of Nitrogen Heterocycles Using Heterogeneous Cobalt Oxide Supported on Nitrogen-Doped Carbon. Org. Lett. 2015, 17, 4404–4407. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b01790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Carter N.; Li X.; Reavey L.; Meijer A. J. H. M.; Coldham I. Synthesis and Kinetic Resolution of Substituted Tetrahydroquinolines by Lithiation then Electrophilic Quench. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 1352–1357. 10.1039/c7sc04435f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Chatterjee B.; Kalsi D.; Kaithal A.; Bordet A.; Leitner W.; Gunanathan C. One-pot Dual Catalysis for the Hydrogenation of Heteroarenes and Arenes. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 5163–5170. 10.1039/d0cy00928h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; g Yang C.-H.; Chen X.; Li H.; Wei W.; Yang Z.; Chang J. Iodine catalyzed Reduction of Quinolines under Mild Reaction Conditions. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 8622–8625. 10.1039/c8cc04262d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Zhao X.; Xiao J.; Tang W. Enantioselective Reduction of 3-Substituted Quinolines with a Cyclopentadiene-Based Chiral Brønsted Acid. Synthesis 2017, 49, 3157–3164. 10.1055/s-0036-1589012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.