Abstract

Tryptophan-containing isoprenoid indole alkaloid natural products are well known for their intricate structural architectures and significant biological activities. Nature employs dimethylallyl tryptophan synthases (DMATSs) or aromatic indole prenyltransferases (iPTs) to catalyze regio- and stereoselective prenylation of l-Trp. Regioselective synthetic routes that isoprenylate cyclo-Trp-Trp in a 2,5-diketopiperazine (DKP) core, in a desymmetrizing manner, are nonexistent and are highly desirable. Herein, we present an elaborate report on Brønsted acid-promoted regioselective tryptophan isoprenylation strategy, applicable to both the monomeric amino acid and its dimeric l-Trp DKP. This report outlines a method that regio- and stereoselectively increases sp3 centers of a privileged bioactive core. We report on conditions involving screening of Brønsted acids, their conjugate base as salt, solvent, temperature, and various substrates with diverse side chains. Furthermore, we extensively delineate effects on regio- and stereoselection of isoprenylation and their stereochemical confirmation via NMR experiments. Regioselectively, the C3-position undergoes normal-isoprenylation or benzylation and forms exo-ring-fused pyrroloindolines selectively. Through appropriate prenyl group migrations, we report access to the bioactive tryprostatin alkaloids, and by C3-normal-farnesylation, we access anticancer drimentines as direct targets of this method. The optimized strategy affords iso-tryprostatin B-type products and predrimentine C with 58 and 55% yields, respectively. The current work has several similarities to biosynthesis, such as—reactions can be performed on unprotected substrates, conditions that enable Brønsted acid promotion, and they are easy to perform under ambient conditions, without the need for stoichiometric levels of any transition metal or expensive ligands.

Introduction

Among several thousand isoprenoid natural products, those containing a tryptophan core are well known for their significant biological activities. Evolutionary pathways in nature have created dimethylallyl tryptophan synthases (DMATSs) and aromatic indole prenyltransferases (PTs) that catalyze regio- and stereoselective prenylation of tryptophan (l-Trp) core leading to the biosynthesis of an array of complex alkaloids (Figure 1A).1

Figure 1.

(A) Biosynthesis of isoprenylated tryptophan alkaloids by DMATS or PTs. PPi = inorganic diphosphate; l-Trp = l-tryptophan; AA = amino acid other than l-Trp; DKP = 2,5-diketopiperazine. Isoprenylation pattern shown in (A) is generic and enzyme products with each of the seven positions undergoing prenyation are known. (B) Representative isoprenylated tryptophan natural products are presented with the Trp core shown in red and isoprenyl chains in blue. Sites of isoprenylation are shown in circle. Respective medicinal activities of these members underscore the significance of synthetic methods affording scalable access to their structures.

Regioselective methods that isoprenylate the tryptophan core leading to complex bioactive molecules are highly desirable. While prenylation is a process concerning incorporation of a C5-isoprene substrate (as in dimethylallyldiphosphate in biogenesis), isoprenylations generally refer to expanded multimers of the isoprene unit including geranyl, farnesyl, and related substrates. Either l-Trp or its corresponding DKP (l-Trp-AA) are typical substrates for these biochemical isoprenylation reactions. Beyond this early biosynthetic step, tailoring enzymes such as halogenases, methyltransferases, oxidases, cyclases, and others catalyze reactions that result in enormous structural diversity of the ultimate products (Figure 1B).1 DKP natural products consist of a vast array of biomedically significant compounds serving as leads for numerous therapeutics as well.2 These natural products continue to serve as a test bed for discovering new transition metal-catalyzed processes for achieving high regio- and stereoselectivities of products.3 Numerous studies have targeted indole C3-activation executing C–C bond formation resulting in allylation, isoprenylation, benzylation, crotylation, and various related alkylation products.4 Organocatalytic methods have also addressed the challenge of indole-C3-allylations in elegant ways.5 Total synthesis strategies and related biosynthetic investigations that target prenylated tryptophan scaffolds have enabled development of new chemistry and biochemistry.6

Among bioactive members of these natural products, nocardioazine A displays noncytotoxic inhibition of mammalian P-glycoprotein (P-gp)-mediated drug efflux7 and thereby is an important lead toward developing therapeutics with reduced toxicity of anticancer drugs. Considering that efflux pumps are one among the major contributors for emergence of resistance, natural compounds that inhibit mammalian ABCB1, ABCG2, and MDR1 types of ATP-dependent efflux pumps are urgently needed.8 Access to isoprenylated indole alkaloids, possessing P-gp inhibitory activities, via regioselective syntheses are therefore desirable.

The indole side chain of tryptophan presents a complex array of nucleophilic sites, presenting several competing modes of reactivity. Biosynthetic steps engineer selectivity based on the tertiary fold and active site of each enzyme to enforce catalysis through tightly controlled transition-state geometries yielding regioselective products that exclude other possibilities. However, native enzymes have highly specific substrates, and thereby, their synthetic scope is limited. Nonenzymatic methods to directly affect isoprenylation of indoles under aqueous conditions are challenging. We previously reported a solvent-dependent, biomimetic Cope rearrangement leading to C4-n-prenylation (n = normal) to access ergotamine scaffold regioselectively.9a Subsequently, in the context of studying nocardioazine biogenesis (a C3-n-prenylated marine alkaloid), we had reported an indole C3-n-prenylation methodology operating, under mild conditions, to access relevant nocardioazine biosynthetic intermediates.9b

Previously, Ishikawa et al. reported a bioinspired nonenzymatic prenylation method in water as the solvent (Figure 2A).10 In that study, l-Trp ethyl ester was exposed to carbocations, originating from either dimethylallyldiphosphate (DMAPP) or its corresponding alcohol. Strong acids such as sulfuric acid or hydrochloric acid were employed for generating the carbocation in order to effect a Freidel–Crafts alkylation of the indole core.

Figure 2.

(A) Summary of Ishikawa’s study (ref (10)) reported biomimetic prenylation reaction resulting in poor regioselectivity. (B) Current work: As an elaboration of previous report (ref (9b)), an expanded scope and utility of this regioselective method is presented.

Prenylation occurred at each nucleophilic site (except C4), of l-Trp, resulting in products 1–7. This study was illustrative of the innate complexity that exists in the form of diffuse nucleophilicities of the indole ring, wherein seven sites compete for a single electrophile, with varying rates. Consequently, eight products were obtained considering C3-prenylated pyrroloindolines (3), as exo and endo diastereomers, in minor yields. A multitude of reactive sites on the indole core leading to parallel reaction modes, resulting in low yields of each product (ranging from 2 to 24%), demonstrates the challenges toward the development of regio- and stereoselective methods. Consequently, a direct regioselective C3-alkylation of cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP, giving access to isoprenylated desymmetrized alkaloids, is unknown.

Herein, we extensively report on the Brønsted acid-promoted isoprenylation and benzylation conditions that were shown to work regioselectively on monomeric l-Trp methyl ester (l-Trp-OMe) earlier.9b We developed this strategy further to cyclodimeric DKP with stereoselectivity, leading to products such as 9 (Figure 2B). Under these conditions, the prenyl cationic activation strategy can be applied to several related allylic and benzylic electrophiles, resulting in a range of diversified isoprenylated, allylated, or benzylated products. The current methodology affords unprecedented regioselectivity and yields. Furthermore, we demonstrate this approach to be adaptable to the total syntheses of isoprenylated tryptophan alkaloids such as the nocardioazines, tryprostatin B/iso-tryprostatin B, and the predrimentines.

Results and Discussion

Ongoing and previous investigations into nocardioazine biosynthesis identified a prenyltransferase (NozC) that regio- and stereoselectively n-prenylates the indole C3-position of the cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP.9b,11 Specific acid and specific base residues are critical in the orchestration of selectivity of these prenyltransferases.12 Considering that nonenzymatic indole prenylations10 gave access to the l-Trp derivatives with diverse substitution patterns, thereby compromising selectivity and yield, we set out to explore the role of an appropriate general acid–general base system to promote regioselective C3-isoprenylations in a manner similar to that of the NozC PTs. Additionally, our recent discovery of cyclodipeptide synthases (CDPSs) that construct cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP aspired us to develop easy-to-use methods that desymmetrically functionalize this privileged core.11

Our screening conditions explored the effect of acetic acid as a Brønsted acid, NaOAc as its conjugate base, and prenyl bromide as the prenyl cation precursor on the regio- and stereoselectivity of n-prenylation of l-Trp-OMe, as listed in Table 1. When the reaction was attempted using a stoichiometric amount of NaOAc (2.0 equiv) in an acetic acid–water solvent system (pH = 3.6), at room temperature (RT), an initial homogeneous clear solution gradually became pale yellow over time (24 h), and three distinctly new spots were observed (monitored by TLC) along with significant amounts of unreacted starting material (Table 1, entry 1). NMR and HRMS analyses of isolated new products indicated mono-n-prenylation of l-Trp-OMe. The characteristic singlets at δ 4.92 and 4.82 correspond to the pyrroloindoline ring, and two distinct singlets of methyl protons (from the n-prenyl group) in the δ 1.5–1.7 region unambiguously confirmed the C3 n-prenylation pattern, as in 11 as exo and endo diastereomers (see the Supporting Information).

Table 1.

| S. No | solvent(s)b v/v | saltc | T (°C) and time (h) | % yieldd |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AcOH/H2O (1:5) | NaOAc | RT, 24 (h) | 30% total yield |

| 2 | AcOH/H2O/MeOH (1:5:1) | NaOAc | RT, 24 (h) | 23% total yield |

| 3 | AcOH | NaOAc | RT, 24 (h) | 70% C3-prenylation, 6% C2-prenylation |

| 4 | EtOAc/MeOH (1:1) | NaOAc | RT, 24 (h) | 69% N-prenylation |

| 5 | ACN/MeOH (1:1) | NaOAc | RT, 24 (h) | 65% N-prenylation |

| 6 | MeOH | RT, 24 (h) | 70% N-prenylation | |

| 7 | DMSO | 50 °C, 5 (h) | no reaction |

Reaction conditions: l-Trp-OMe (100 mg, 0.458 mmol, 1.0 equiv), prenyl bromide (10) (105 μL, 0.92 mmol, 2 equiv) in various solvents.

Reaction performed in 0.1 M solvent(s).

2.0 equiv of salt added.

Products isolated after purification by column chromatography: C3/C2/N-prenylation determined by NMR analyses.

For the minor side product 12, a characteristic broad singlet at δ 7.89 indicated an indole N–H signal, and a relatively upfield methylene carbon (δ 25.3) of the prenyl group attached to the sp2 hybridized C2 carbon of the indole ring indicated a C2 n-prenylation product. Disappearance of the C2 proton (of l-Trp-OMe at δ 7.20) signal correlated well with this observation. Moreover, by comparing the NMR spectra between the starting material and products, we verified that the C4–C7 positions of the indole nucleus were unperturbed throughout this prenylation reaction. This was evident through the preservation of phenyl C–H signals in all isolated products in the δ ∼6.5–8.0 region and their similar multiplicity patterns characterized by 1H NMR analysis. Interestingly, besides C3 and C2 n-prenylation modes, no other detectable prenylation pattern was observed. Further solvent screening ensued, and use of an additional protic solvent such as methanol did not improve the selectivity and yield of products (Table 1, entry 2). The use of glacial acetic acid as a solvent with excess NaOAc (2.0 equiv) was found to be beneficial and improved the overall yield of n-prenylation products 11 (C3) and 12 (C2) (76%, combined) (Table 1, entry 3). The ratio of C3/C2 prenylation favors the C3 product under these conditions, in contrast to those reported by Ishikawa et al. wherein use of much stronger Brønsted acids caused the C3/C2 ratio to reverse to 1:4, favoring the C2-prenylation pattern.10 Surprisingly, switching from acidic to nonacidic solvent conditions radically changed the regioselectivity of the reaction. Only the α-primary amine underwent n-prenylation to give product 13, which was evident from intact aromatic peaks (δ 7.06–7.60) and benzylic (multiplet, δ 3.09–3.25) proton peaks (Table 1, entries 4–6). On the other hand, polar aprotic solvents were found to be detrimental for the reaction (Table 1, entry 7). Interestingly, this report is the first that delineates the unusual prenylation patterns as a rigorous function of varying solvents. Employing prenyl acetate instead of the bromide shut down the reaction. Neither was the prenyl alcohol effective under these mild acid conditions. The halides employed in this study, including prenyl, crotyl, and benzyl halides, were structurally stable and did not disintegrate under prolonged reaction conditions, as observed by 1H NMR analyses.

A significant synergism between the acidic solvent and the metal acetate is essential for increased regioselectivity, favoring C3-prenylation of l-Trp-OMe. Having identified acetic acid as a suitable solvent for the transformation, we turned our attention to the possible use of various metal acetates to further increase the yield of the desired products, and to possibly improve diastereoselectivity in the C3 prenylating mode, as listed in Table 2. It was found that alkali metal acetates promote smooth C3 and (minor) C2 prenylation to give corresponding products 11 and 12, respectively, in good yields. The metal acetates were generated in situ from the acid–base reaction of acetic acid and corresponding metal bases. Because the equilibrium constant of the reaction between AcOH and LiOH is ∼1011, in all our experiments, we relied on generating acetates in situ. Trace amounts of water generated in the reaction mixture did not affect the reaction course in any significant manner.

Table 2.

| S. no | saltb | Brønsted acid promoter | solvent | T (°C) | total yield (%) (C2 yield)d | dre |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | NaOAc | AcOH | AcOH | RT | 50 (6) | 1:1 |

| 2 | NaOAc | AcOH | AcOH/MeOH (9:1) | RT | 47 (11) | |

| 3 | LiOAc | AcOH | AcOH | RT | 76 (9) | 1:1 |

| 4 | CsOAc | AcOH | AcOH | RT | 55 (6) | 1:1 |

| 5 | KOAc | AcOH | AcOH | RT | 55 (6) | 1:1 |

| 6 | AgOAc | AcOH | AcOH | RT | 25 (nd) | nd |

| 7 | AgOAc | AcOH | AcOH | RT | Decomp. | |

| 8c | LiOAc | (R)-BINOL | AcOH | RT | 70 (8) | 1:1 |

| 9c | LiOAc | (S)-BINOL | AcOH | RT | 70 (8) | 1:1 |

| 10c | LiOAc | (R)-BINOL phosphoric acid | AcOH | RT | 65 (8) | 1:1 |

| 11c | LiOAc | (S)-BINOL phosphoric acid | AcOH | RT | 65 (8) | 1:1 |

Reaction conditions: l-Trp-methyl ester (l-Trp-OMe) (220 mg, 0.916 mmol, 1.0 equiv), prenyl bromide (10) (212 μL, 1.83 mmol, 2.0 equiv) in acetic acid (0.1 M), 12 h.

2.0 equiv of salt added.

1.0 equiv of the Brønsted acid promoter added.

Isolated yield after purification by column chromatography and calculated based on recovered starting material: C3/C2-prenylation determined by NMR analyses.

dr-diastereomeric ratio between exo and endo isomers (by NMR). RT: room temperature; Decomp: substrates decomposed into unverifiable mixture; nd-not determined. Method is scaled up to 0.5 g of l-Trp-OMe, and no reduction in the isolated yield was observed.

With lithium acetate as the general base, and acetic acid as a general acid promoting C3 and minor C2 prenylation, we obtained a 76% total yield of products (11 + 12) with a 7.4:1 ratio between C3 to C2 prenylation patterns. The diastereoselectivity ratio was however 1:1 between exo and endo isomers of 11 (Table 2, entry 3). Based on isolated yields of products, use of cesium and potassium acetates was found to be slightly inferior to the lithium counterpart. Due to the fact that silver acetate was only sparingly soluble in the reaction mixture, despite its well-known ability to generate allyl cations, the reaction resulted only in modest yields of desired products. Attempts to increase the solubility of silver acetate by heating the reaction mixture (50 °C) caused decomposition of the starting material and products (Table 2, entries 6 and 7). To increase the stereoselectivity (exo/endo ratio) of C3 prenylation, we envisioned incorporating chiral Brønsted acid promoters alongside lithium acetate. Various C2-symmetric chiral Brønsted acid promoters (R and S-BINOL and R and S-BINOL phosphoric acid) were found to be futile to improve the stereoselectivity of indole C3-n-prenylation (Table 2, entries 8–11).

Varying prenyl bromides to their chlorides, alcohols, or their acetates resulted in practically no conversion. Under optimized reaction conditions (LiOH [2 equiv] in acetic acid [pKa = 4.76] at RT), the ratio between C3 and C2 prenylation products remained constant over the time. However, prenyl shift from the C3 to C2 position was accelerated under highly acidic conditions (e.g., addition of trifluoroacetic acid [pKa = 0.52])

|

1 |

Considering that C3-benzylated pyrroloindolines are structural cores in several pharmacologically active leads, the scope of this optimized prenylation method was extended to benzylation of l-Trp-OMe (eq 1). Insights drawn from regioselectivity of prenylation reactions were applicable to the C3-benzylation attempts. The crucial role of acetic acid in directing regioselectivity drove the search further for suitable metal cation donors (as conjugate bases) in order to attain better efficiency. For benzylation, after screening, we observed that increasing the temperature to 60 °C, with 2.0 equiv of lithium acetate, resulted in smoother conversion and better yields (Table S1). Similar to the prenyl bromide case, we found that benzyl bromide when treated with lithium or sodium acetate (independently) in acetic acid was also found to be stable even after a prolonged duration. The optimized benzylation condition displayed a trend similar to the prenylation of l-Trp-OMe, wherein the C3-benzylated pyrroloindoline diastereomers of 15 were formed as major products (exo and endo isomers in a 1:1 ratio), and the corresponding C2-benzylated tryptophan methyl ester 16 was the minor product in an overall yield of 60%. The C3-benzylated product (48%) dominated over the C2-benzylated product (12%) by a ratio of 4:1. Similar to the prenylation reactions, the synergism between the Brønsted acid solvent and the metal cation was a crucial driving force in regioselective benzylations as well. After initial C3 benzylation, subsequent C3 to C2 transfer of the benzyl group (through a benzyl chain migration mechanism) could account for observing minor C2-substituted products. Similar to the prenylation case, the N-benzylation product was not observed, probably due to the fact that the Brønsted acid provides sufficient protonation, thereby preventing alkylation at the α-N site.13 The presence of C3-benzylated 15 (as exo and endo isomers) was confirmed by NMR and HRMS analyses. The signature 1H NMR peaks of the newly formed pyrroloindoline ring (C2–H) were observed at δ 5.01 and at δ 5.02 for the C3 exo and endo isomers, respectively. In a correlating manner, two 13C peaks of pyrroloindoline sp3 carbons for the exo isomer were distinctly present at δ 81.8 and 52.3. For the endo isomer, similar peaks were identified at δ 82.3 and 52.3. As further confirmation, a peak that is usually relatively downfield, for example, the indole N–H (at δ 10.5 in l-Trp-OMe), was shifted upfield to δ 3.15 and 2.85 as broad singlets in 15-exo and 15-endo isomers, respectively. This alluded to the nonaromatic nature of this ring system. In contrast, for the C2-benzylation product, this indole N–H proton being preserved in product 16 is indicative as a broad singlet at δ 7.78. Furthermore, the sp2 carbons of the indole ring show up at δ 135.2 and 107.9 (at C2 and C3, respectively), confirming the presence of 16.

We then attempted to expand the scope of substrates undergoing regioselective alkylations on l-Trp-OMe by employing an array of prenyl and benzyl bromides as electrophiles (Table 3). As expected, each alkylation reaction with prenyl bromide, crotyl bromide, geranyl bromide, farnesyl bromide, benzyl, and p-methyl benzyl bromide occurred, confirming to the observed general pattern with diastereomers of C3-substituted regioisomers in a higher yield than the corresponding C2-substituted isomers. Each reaction was thoroughly monitored by TLC, and separable products were purified by column chromatography and further analyzed by NMR and HRMS techniques. Interestingly, in comparison to C3-n-prenylation (Table 3, entry 1), crotylation conditions (with 17) gave only C3-substituted products at a moderate yield of 51%, with a diastereomeric ratio of 4.5:1, favoring the C3 exo major diastereomer of 11b (entry 2). l-Trp-OMe underwent farnesylation with 19 (entry 4) and provided 11d at a 2.7:1 ratio of C3/C2 farnesylated heterocycles, with 45 and 17% isolated yields, respectively (62% total yield), in a near equimolar diastereomeric ratio of exo-11d: endo-11d (1.2:1). Surprisingly, identical conditions to geranyl bromide (18) gave a relatively lower yield (32% total, with a C3/C2 ratio of 4.3:1), as shown in entry 3. The major C3-geranylated product was in a diastereomeric ratio of 1.7:1 (exo/endo).

Table 3.

Reaction conditions: l-Trp-methyl ester (l-Trp-OMe) (200 mg, 0.916 mmol, 1.0 equiv), bromide (10, 14, 17–20) (1.84 mmol, 2 equiv) in acetic acid (0.1 M).

Isolated yield after purification by column chromatography; yield calculated based on the recovered starting material: C3 and C2-functionalistaion determined by NMR analyses.

dr-diastereomeric ratio between exo and endo isomers—calculated based on isolated yield and NMR analysis.

Benzylation and p-methyl benzylation reactions were carried out at elevated temperatures. Alike entry 5 (Table 3), p-methyl benzylation with 20 yielded a separable mixture of C3 (15f) and C2 (16f) regioisomers at a ratio of 4.3:1. A total isolated yield of 84% was obtained. The C3-alkylated products in a diastereomeric ratio of 1.4:1 were observed. In each case, the isoprenylated and benzylated products comprising the major exo isomer were found to be separable and isolable from their endo counterpart by column chromatography.

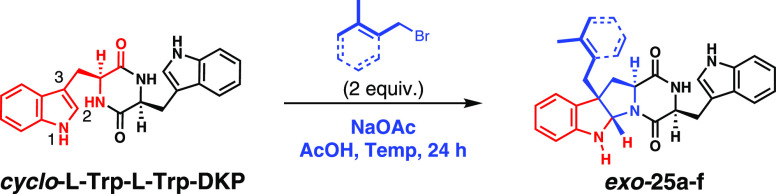

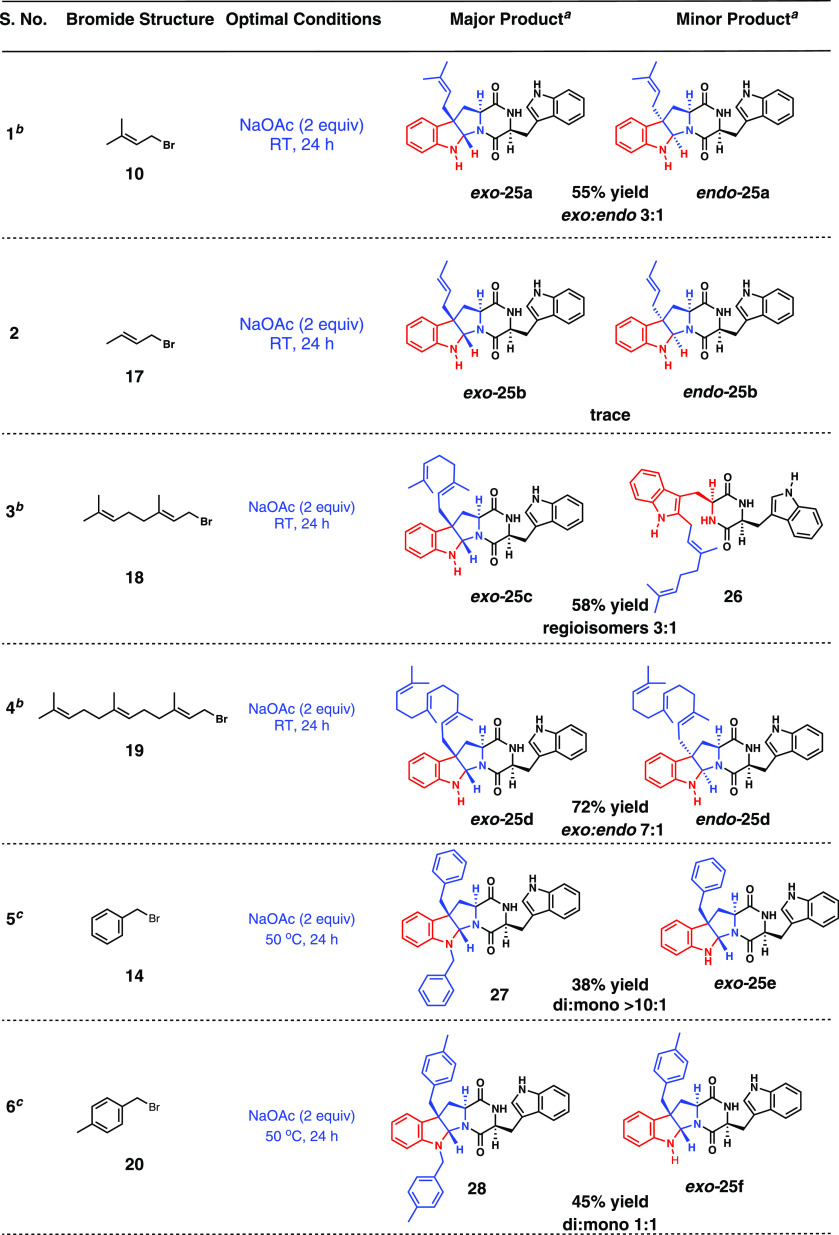

The scaffolds of C3- and C2-isoprenylated alkaloids such as the nocardioazines, tryprostatins, and drimentines demand isoprenylation methods that would work well ideally on a Trp–Trp or Trp-AA DKP core (where AA = Pro or other amino acids). Considering that our probe offered optimal conditions for direct regioselective isoprenylations of the tryptophan moiety, we then challenged the method to directly isoprenylate or alkylate the cyclic dimer cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP, as illustrated earlier in Figure 2B. In order to address this challenge, we first carried out synthesis as shown in Scheme 1. α-N of the amine portion of l-Trp was protected with the tbutyloxycarbonyl (Boc) group (21), and the other coupling partner was the l-Trp carboxymethyl ester hydrochloride (22). Coupling using 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) chloride with HOBt enabled the peptide bond-forming reaction in a clean manner with an easy workup procedure and a straightforward purification (column chromatography), yielding 23. Although we earlier reported the use of BOP-Cl for forming the peptide bond,9b it was resource-economic and efficient to employ EDC chloride. The formic acid-mediated deprotection of the Boc group was carried out smoothly and afforded the free 1° amine (24). The amine 24 was then subjected to an intramolecular cyclization event under a 12 h reflux reaction with methanolic ammonia (pH ∼ 10) furnishing the cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP in ∼88% yield without epimerization, which was evidenced through the 1H NMR of the product (showing characteristic peaks consistent with a single diastereomer).

Scheme 1. Synthesis of Cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP.

No literature precedent exists about conditions that could selectively diversify one of the indole rings in a homodimeric tryptophan containing a DKP unit. Although there is some work already done on functionalizing the tryptophan side chain in DKPs,14 the reported substrates were heterodimeric containing only one tryptophan unit, with the other half of the DKP presenting no competition to isoprenylation possibilities. Cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP presents two indole side chains with an array of possible reactive sites, which can compete for the Friedel–Crafts alkylation reaction, presenting a daunting challenge of regioselectivity. In theory, therefore, we expected to see reactivity profiles to result in a plethora of structurally diverse compounds.

Drawing inputs from our promising monomeric l-Trp-OMe isoprenylation results, we extended the method to cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP. Solubility of cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP in various organic solvents showed that highly polar solvents such as acetonitrile, methanol, or DMSO were required for preparing homogeneous solutions, and fortuitously, acetic acid was found to be effective as well. Initially, we tested the reaction with 2 equiv of prenyl bromide with cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP with acetic acid as the solvent. Although the reaction worked, the yields were unsatisfactory (Table 4, entry 1). Similar to monomeric functionalization, use of a salt that can act as a conjugate base proved to be beneficial, as evidenced by the use of NaOAc (2.0 equiv), causing the isolated yields to significantly improve from 30 to 55%, the best obtained yield thus far (entry 2). We further explored other salts such as CsOAc and LiOAc. Like the monomeric reaction optimization, we added hydroxide bases in acetic acid to generate the corresponding acetate salts in situ. Similarly, CsOAc was generated in situ by using CsCO3 as an additive (entry 4). Also, we experimented with tertiary amines such as DABCO and quinine as bases, only to get unsatisfactory yields despite minimal visible conversion (entries 7-8). A change of the solvent from acetic acid to dimethyl sulfoxide or dimethyl formamide effected no reaction (entries 8–11). Considering that we obtained two spots as major products, we set out to confirm their structures by NMR spectroscopy. A noticeable difference was evident between the 1H NMR spectra of the reactant and the monoprenylated cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp-DKP products, 25 (endo and exo). The 1H NMR spectra of the products (25, endo and exo) clearly indicated a successful desymmetrization of the C2-symmetric DKP core. The two methyl peaks at δ 1.53 and 1.71 (δ 1.7 and 1.62, for minor diastereomers), a triplet corresponding to alkene proton at δ 5.15 (at δ 5.1, for minor diastereomers), and a multiplet at δ 2.44–2.27 (δ 2.57–2.33, for minor diastereomers) are characteristic of the n-prenylated side chain (see Supporting Information). The characteristic sharp singlet at δ 5.33 (δ 5.36, minor diastereomer) is attributable to indole-to-indoline transformation.

Table 4.

| S. no | saltb | solvent | time (h) | total yieldc (%) | drd |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AcOH | 12 | 30 | nd | |

| 2 | NaOAc | AcOH | 12 | 54 | 3:1 |

| 3 | LiOAc | AcOH | 12 | 48 | 3:1 |

| 4 | CsOAc | AcOH | 12 | 45 | 3:1 |

| 5 | LiBr | AcOH | 12 | 40 | 3:1 |

| 6 | nBu4NBr | AcOH | 12 | 35 | nd |

| 7 | nBu4NI | AcOH | 12 | decomp. | |

| 8 | DABCO | AcOH | 24 | 40 | 3:1 |

| 9 | quinine | AcOH | 24 | 38 | nd |

| 10 | NaOAc | DMSO | 24 | trace | |

| 11 | NaOAc | DMF | 24 | trace | |

| 12 | NaOAc | MeOH/EtOAc (1:1) | 48 | nd | |

| 13 | NaOAc | MeOH/ACN (1:1) | 48 | nd |

Reaction conditions: cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP (100 mg, 268.51 μmol, 1.0 equiv), 10 (62 μL, 537.02 μmol, 2.0 equiv) in solvent(s) (0.05 M) at room temperature (RT = 25 °C).

2.0 equiv of the salt/base added.

Isolated yield after purification by column chromatography.

dr-diastereomeric ratio between exo and endo isomers, calculated based on the isolated product and 1H NMR analysis. Decomp: substrates decomposed into unverifiable mixture; nd-not determined. The reaction was scaled up to 0.5 g of cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP, and there was no reduction in the isolated yield.

Significantly, this method does not lead to prenylation at any site other than the C3 position of a single Trp unit. Other alkylation products were not observed. Having identified the optimal reaction conditions, we expanded the substrate scope of desymmetric indole-DKP functionalization using various allyl and isoprenyl bromides (Table 5).

Table 5.

Reaction conditions: cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP (100 mg, 268.51 μmol, 1.00 equiv), bromide (10, 14, 17–20) (537.02 μmol, 2.0 equiv) in acetic acid (0.05 M).

Isolated yield after purification by column chromatography.

dr and regioisomeric ratio calculated yield and 1H NMR analysis.

Mono- and dibenzylation ratio determined by 1H NMR analysis. RT = 25 °C.

Crotylation was inefficient under these conditions (entry 2). Under optimized reaction conditions, cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp-DKP underwent geranylation to give a corresponding regioisomeric mixture of C3 (major) and C2 (minor) geranylated products exo-25c and 26, respectively, with moderate yield and selectivity (59%, C3/C2 = 3:1, entry 3). On the other hand, farnesylation of cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp-DKP gave a diastereomeric mixture of C3-farnesylation products exo-25d and endo-25d, with a good overall yield and diastereomeric ratio (exo/endo = 7:1, entry 4).

Under optimized conditions, benzyl bromide 14 and p-methyl benzyl bromide 20 formed turbid mixtures, which remained unchanged over the course of the reaction. Gratifyingly, elevated reaction temperature (50 °C) accelerated the rate of benzylations. Under these conditions, subsequent indoline N-benzylation was inevitable (resulting in over benzylated 27 and 28, respectively). At an elevated temperature, benzylation of cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp-DKP furnished the corresponding dibenzylation product 27 in moderate yield (entry 5). While, p-methyl benzylation furnished the inseparable equimolar mixture of C3 mono p-methyl benzylation product exo-25f and corresponding bis-p-methyl benzylation product 28 (entry 6). Although differential ratios of di-to monobenzylation products are obtained between these two cases, an exact reason as to why it is so remains a bit unclear. Nevertheless, access to the C3-benzyl desymmetrized DKP system bodes well for further exploration of their potential pharmacological effects.

Access to Tryprostatin and Drimentine Natural Product Scaffolds

Upon developing this isoprenylation method displaying regioselectivity to either C3 or C2 positions, we subsequently put these conditions to test in the context of a biomimetic entry to the tryprostatins and drimentines in addition to the nocardioazines we reported earlier.9b Results of our attempts are shown in Scheme 2. Tryprostatin B, consisting of a C2-n-prenyl motif on a l-Trp-l-Pro DKP core, is a potent bioactive natural product showing inhibition of tubulin polymerization through the action of arresting the mammalian cell cycle, targeting MAP-2 (microtubule-associated protein-2) pathways.14 Similar to our observations that gave minor amounts of the C2-regioisomer of prenylated l-Trp as described in Table 3 [entry 1], our attempt to access tryprostatin B involved siphoning the C3-prenylated pyrroloindoline (11) into its C2-isoprenyl isomer (12). Taking insights from the literature,15 we proposed adopting our C3-isoprenylating method as a reasonable path, although initially, the yields obtained for 12 were of concern. Accordingly, when cyclo-l-Trp-l-Pro DKP 32 (whose synthesis followed a scheme similar to cWW; see the Supporting Information) was subjected to our optimized C3-n-prenylation conditions, using prenyl bromide, we obtained a mixture of three identifiable compounds in 58% total yield. As shown in Scheme 2, bis-prenylated cyclo-l-Trp-l-Pro 33a, desired exo-34a and tryprostatin B (35a) were formed, formally completing the total synthesis of the natural product. Coincidentally, exo-34a and tryprostatin B (35a) formed an inseparable mixture due to their similar polarity characteristics. Interestingly, only the endo C3-prenylated isomer would undergo bis-prenylation at the N1 site additionally. In theory, the α-versus β-relative stereochemical orientation at the fused ring junction of the pyrroloindoline ring (in 36) is probably immaterial, to which the isomer could follow the prenyl-group migration, as shown in part B of Scheme 2, aided by the acid–acetate combination used in these conditions. This path illustrates the route we would like to optimize in future to increase the yield of 35a.

Scheme 2. Enantiospecific Access to C3/C2-Isoprenylated Trp Natural Products: Tryprostatin B, Drimentine C, and Nocardioazine B.

The drimentines are streptomyces-derived DKP-terpenoid natural products showing cytotoxicity against HTC cancer cells.16 The characteristic structural feature of these alkaloids is an indole-C3-farnesylation pattern of a cyclo-l-Trp-l-Pro DKP core. Biogenetically, the C3-farnesylated chain is further cyclized through the involvement of potential late-stage isoprenyl cyclization, reminiscent of classic terpenoid biogenesis. Similar to prenylations, we subjected cyclo-l-Trp-l-Pro 32 to farnesylation with 2 equiv of 19. This step followed our optimized conditions consisting of 2 equiv of NaOAc in acetic acid at RT for 12 h. Reaction monitoring through TLC revealed progress of the reaction to indicate formation of nonpolar spots relative to 32. Overall, we obtained a 55% total yield for the C3-farnesylated products as a mixture. Upon isolation of products via chromatography, we observe exo-34b, which is a probable precursor of drimentine C (which is one terpene cyclization away). Interestingly, the C3- to C2-farnesyl group migration was observed, similar to the tryprostatin case, and the reaction afforded an inseparable mixture of endo-34b and corresponding C2 product 35b. As revealed in the Supporting Information, structural confirmation for these products were obtained through 1H and 13C NMR and mass spectral studies. It is noteworthy that the isoprenylation conditions enable us to access analogues of drimentine alkaloids that are cyclic heterodimers with Trp–Pro/Val/Leu pairs as DKPs. These studies complement our earlier report9b on using the C3-prenylation method to access des-Me-nocardioazine-B. The intermediate cyclo-C3-Me-d-Trp-d-Trp shown in Scheme 3C underwent C3-n-prenylation under similar conditions, yielding the natural product congener in 67% yield. Collectively, multiple n-prenylated compounds were rigorously characterized using 1D, nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY), 2D NMR experiments as described below.

Scheme 3. Example of DMATS Prenylating Indole Core Regioselectivity.

Stereochemical Characterization of Isoprenylated DKPs

We resorted to a series of nOe correlations as well as 1H and correlation spectroscopy (COSY) NMR analyses through identification of the isolated spin systems, Hα1-Ha-Hb and Hα2-Ha′-Hb′, that bolstered our interpretation of relative stereochemistry for the desymmetric C3-isoprenylated cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp-DKP products obtained in this study (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

(A) nOe correlations for cyclic C3-isoprenylated pyrroloindolines reported herein; (B) 1H–1H COSY data and nOe correlations for cyclo-C3-Me-N1′-Me-d-Trp-d-Trp DKP reported in ref (9b).

To establish the relative stereochemistry of the major product (exo-25a), we analyzed 1D-NOE and 2D-NOESY correlations of the pyrroloindoline ring system (Figure 3A). Among normal but nondeterministic nOe correlations are seen between DKP α-proton (Hα1) with methylene Ha (1.13%) and that with Hb displayed 2.59% enhancement, indicating closer proximity for the latter case. Inversely, and more deterministically, the nOe correlation of Ha to Hα1 is 2.79% and that of Hb to Hα1 showed a decisive 6.55% signal enhancement. This observation was further supported by deterministic nOe correlations between Ha and Hd (2.29%), while no such enhancement was seen when Hb was pulsed. The signal seen for a correlation through space for the vinylic proton Hd interacting in closer proximity with Ha unambiguously confirms the exo stereochemistry of major 25a. Similarly, the nOe correlation between DKP core protons Hα1 and Hα2 indicated a cis DKP ring junction and that probably no epimerization occurred during the C3-n-prenylation reaction. We performed a series of such experiments, as illustrated by each example in Figure 3A for products such as exo-25c, exo-25d, endo-33, and exo-34b. To correlate these results with a different C3-substitution-patterned derivative, we referred to our earlier published report,9b wherein we synthesized cyclo-C3-Me-d-Trp-N1′-Me-d-Trp DKP. For establishment of relative stereochemistry of the ring fusion with respect to the α-amino acid stereogenic center, for the pyrroloindoline ring portions, we employed nOe and long-range (LR) 1H–1H–COSY pulse sequences.

In 2010, Capon et al. reported the isolation of the nocardioazines,7 suggesting that the molecule harbors a cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp core. Subsequent total syntheses and accompanying spectroscopic analyses led to the revision of the stereochemical assignment to its cyclo-d-Trp-d-Trp core. Although the 1H and 13C spectra arising out of independent synthetic endeavors were in a full agreement with the natural product isolated by Capon et al., the optical rotation studies of the synthetic compound led to the reassignment of stereochemistry.17 As shown in Figure 3B, a nOe signal of 2.62% between C2–H and C3–Me indicated a cis relative stereochemistry at the B–C ring fusion (C2—C3). An exo relationship of the pyrroloindoline B–C ring system was confirmed through the protons at the C3–Me substituent, displaying a nOe signal of 2.62% with the α-proton at C8 (Ha) of the product. The diastereotopic β-proton at C8 (Hb) displayed no nOe correlations with the C3 methyl substituent. The l-Trp-derived stereocenter at C9 with a proton showed a 3.06% nOe correlation with the α-proton at C8. The protons at C2 and C9 displayed a nOe signal of 0.95%. Overall, these assignments were correlated with the COSY spectral assignment, indicating the relative stereochemical disposition of substituents in this product, as shown in Figure 3B. The proton NMR signals assigned to C9, C8 Ha, and C8 Hb were distinctly different from those at C9′H, C8′-Ha, and C8′-Hb, respectively. Overall, relative stereochemistries were consistent with those observed in nocardioazines A and B. The establishment of relative connectivities of substituents verified that cyclo-C3-Me-d-Trp-N1′-Me-d-Trp DKP possesses the 6–5–5–6 (A–B–C–D) ring system that is present both in nocardioazines A and B. nOe correlations shown with a Chem-3D rendered ball and stick model depict the relative stereochemistry of substituents across the central DKP ring. 1H–1H LR-COSY correlations shown for cyclo-C3-Me-d-Trp-N1′-Me-d-Trp DKP (measured at 600 MHz for the region between δ 1.2 and 5.2) further confirm the molecular connectivity and further add confidence to our assignments.

Biomimetic Nature of Indole Isoprenylations

As discussed earlier, the isoprenoid indole alkaloids are structurally complex molecules, displaying significant biological activity.18 In biosynthesis, regioselective indole prenylation effected by indole prenyltransferase enzymes (PTs) typically forces a prenyl cation as the electrophilic substrate to undergo indole alkylation.19 Many homologues of iPTs employ a monomeric l-Trp amino acid or its dimeric cyclo-l-Trp-l-AA DKPs as nucleophiles. The generally accepted mechanism for most indole prenyltransferase enzymes involves a regio- and stereospecific Friedel–Crafts alkylation of a selective site on the aromatic ring of the Trp motif (Scheme 3).20

By positioning the prenyl cation [generated from dimethyl allyl diphosphate] in close proximity to the C4 position of the indole side chain of l-Trp, an SN1-like nucleophilic substitution is initiated (on 38 leading to 39), eventually leading to a nonaromatic intermediate such as 40. Lys174 aids in rearomatization, resulting in 41. Lys174 and Glu89 provide specific acid and specific base catalysis at the active site of these prenyltransferases. Replacement of Lys174 and Glu89, even with functionally similar amino acids, abrogates the rate of the C4 prenylation. Enzymatic prenylation on each indole core (N1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, and C7) has been observed.21 Few select mutants of wild-type indole prenyltransferases have enabled interesting mechanistic alternatives to this general paradigm to involve Cope rearrangements of alternative intermediates.22 Similar to DMATS, we envisioned a general-acid–base-promoted regioselective isoprenylation on the Trp core.

As described in Scheme 4, we expected the C3 nucleophilic position to react with the prenyl bromide, followed by a concomitant pyrroloindoline cyclization by the DKP ring nitrogen. Ishikawa’s study prompted the fact that highly strong acids cause a diffusive, nonselective,10 addition of nucleophilic sites to prenyl cation. In this system involving acetic acid/metal acetate mixture, we projected a sequence, as illustrated in Scheme 4, through assembly of intermediate 42, resulting in des-N1-Me-nocardioazine B. The e– rich π-bond, between the C3–C2 sp2 hybridized carbons of the indole side chain, with C3 having higher relative e– density, pushes out the bromide anion from prenyl bromide, which pairs up with the metal cation. Concomitantly, the acetate ion helps deprotonate H from the indole N–H, further helping prenylation of cyclo-C3-Me-d-Trp-d-Trp, leading to 42. Overall, the conjugate base (metal acetate) probably functions as a general base and the presence of large excess of mild acid helps 42 cascades into the pyrroloindoline product through a general acid-promoted mode. Stereoselectivity could be explained by invoking a probable conformational orientation as represented by 43, wherein a re-face attack of the C3 position of indole on the prenyl cation could explain formation of 44. Diastereoselection of DKP N–H attacking the indolenium ion in 44 to result in cis pyrroloindolines is generally accepted.

Scheme 4. Biomimetic Pathway Illustrating the Similarity of General-Acid–General-Base-Promoted C3-Isoprenylations.

Conclusions

Herein, we present a bioinspired route that regioselectively isoprenylates cyclo-Trp-Trp in a DKP core in a desymmetrizing manner. Currently, a single-step method to regioselectively incorporate isoprenyl motif to cyclo-Trp-Trp in a DKP core is nonexistent, and such a method is highly desirable considering that they can afford direct late-stage functionalization of a privileged DKP core present in several natural products. At the outset, our biomimetic study started with comparisons of regioselectivity in product formation between use of strong Brønsted acids versus their milder alternatives in combination with their metal acetates as mixtures. A thorough search of optimal solvents and metal acetates conclusively shows that Li+ or Na+ is sufficiently capable to aid/facilitate the generation of isoprenyl cations with the acetate anion, helping in nucleophilic substitution selectively from C3 of the indole side chain of l-Trp. For monomeric l-Trp, we identify selective conditions that lead to divergent paths between C3-prenylations and N-prenylations. C2-prenylated products, arising from the C3-regioisomers, are the only side products formed. In almost all cases, although the reaction does not reach theoretical completion, recovery of the starting material is feasible. In dimeric reactants, only a single tryptophan unit is perturbed under these conditions, despite increasing the electrophile stoichiometry. Expanded substrate scope includes isoprenyl halides as well as crotyl, benzyl, and related electrophiles with diverse steric variations. Unlike uniform reactivity patterns that were observed for tryptophan monomer examples, the regio- and stereochemical outcomes of our attempts with cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP were a bit more complex.

This report outlines a methodology that regioselectively increases sp3 centers of a privileged bioactive DKP core.2 The method allowed us to access C3-n-isoprenylated or benzylated pyrroloindolines, as shown by the examples in Scheme 2. Because farnesylation also was shown to occur smoothly, we show that a direct access to predrimentine C (exo-38), a fungal bioactive natural product, is possible. Using a C3 to C2 prenyl migration mechanism, we show that the method also provides access to tryprostatin B and related C2-isoprenylated indole alkaloid natural products. The current work has several similarities to biosynthesis, such as—reactions can be performed on unprotected substrates, conditions enable Brønsted acid promotion and are easy to perform under ambient conditions.

Experimental Section

Reagents, Solvents, and Glassware

Unless otherwise stated, all reactions were carried out under a blanket of nitrogen or under regular atmospheric conditions, using a standard syringe or cannulation techniques. All amino acids and KOtBu were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. EDC chloride, HOBT, triethyl amine, and NaOAc were purchased from Spectrochem. Ethyl diisopropyl amine and LiOH were purchased from TCI chemicals. Glacial acetic acid was obtained from Rankem and used without further purification. Dichloromethane was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used without further purification. All other solvents were purified according to specific literature procedures, unless otherwise noted.

Chromatography

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed using silica gel 60 GF254 precoated aluminum backed plates (2.5 mm), specifically to monitor the progress of each chemical reaction and used as a guide for purification of the ensuing mixtures. Various combinations of ethyl acetate/hexane and methanol/dichloromethane were used as the eluent. Visualization of spots after TLC was accomplished by exposure to staining agents (iodine vapor, ninhydrin, and/or PMA) and/or UV light (254 nm). All compounds were purified using gravity column chromatography (silica gel grade: 100–200 mesh). Yields refer to compounds isolated to analytical purity after chromatography.

Analytical Characterization

NMR spectroscopic analyses (1H NMR, 13C NMR) were conducted for all new compounds. 1H (400 MHz) and 13C (100 MHz) spectra were recorded on a 400 MHz spectrometer. Pertinent frequency is specifically reported for each compound. Chemical shift values (δ) for NMR spectra are reported in parts per million (ppm) relative to the residual (indicated) solvent peak (CDCl3 or CD3OD). Additional peaks other than the compound in question, if any, are calibrated based on reported values for trace impurities. Coupling constants are reported in Hertz. Data for 1H NMR are reported as follows: chemical shift (δ, ppm), multiplicity (s = singlet, brs = broad singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, ddd = double double doublet, m = multiplet, cm = complex multiplet), integration corresponding to the number of protons followed by coupling constants in Hz. For 13C NMR spectra, the nature of the carbons (C, CH, CH2, or CH3) was determined by recording the distortionless enhancement by polarization transfer (DEPT) experiment, and notations are provided in parentheses. 13C NMR data are reported in parts per million (δ) relative to the residual (indicated) solvent peak. NOESY, 1H–1H–COSY. All melting points for solids were determined on a Büchi B-540 instrument and are reported uncorrected. pH determination was performed with a standard pH meter. Chiroptical measurements ([α]D) were obtained on a polarimeter in a 100 × 2 mm cell. Mass samples were analyzed by high-resolution mass spectrometry using an ESI TOF spectrometer.

General Procedure A for Indole-C3- or C2-n-Prenylation of l-Trp-OMe

To a magnetically stirred solution of l-Trp-OMe (200 mg, 0.916 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and LiOH (44 mg, 1.83 mmol, 2 equiv) in acetic acid (9 mL) were added prenyl bromide, 10 (212 μL, 1.83 mmol, 2 equiv), at RT. The resulting mixture was stirred at the same temperature overnight. After 12 h, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 99:1) to yield an isomeric mixture of C3-prenylated-l-Trp-OMe (exo-11a and endo-11a, in a 1:1 ratio, 117.6 mg, 0.41 mmol) and C2-prenylated-l-Trp-OMe (12a, 16 mg, 0.055 mmol) in 76% overall yield (based on the recovered starting material); 33% of unreacted l-Trp-OMe was recovered).

Procedure for α-Amino-Acid-N-n-Prenylation of l-Trp-OMe (13)

To a magnetically stirred solution of l-Trp-OMe (200 mg, 0.916 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and NaOAc (44 mg, 1.83 mmol, 2 equiv) in MeOH/EtOAc (1:1, 10 mL) was added prenyl bromide (212 μL, 1.83 mmol, 2 equiv) at RT. The resulting mixture was stirred at the same temperature overnight. After 12 h, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 98.5:1.5) to yield N-prenylated l-Trp-methyl ester, 13 (180 mg, 0.629 mmol) in 69% overall yield.

Half-a-Gram Prenylation of l-Trp-OMe

To a magnetically stirred solution of l-Trp-OMe (500 mg, 2.29 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and LiOH (109.7 mg, 4.58 mmol, 2 equiv) in acetic acid (45 mL) was added prenyl bromide, 10 (530 μL, 4.58 mmol, 2 equiv), at RT. The resulting mixture was stirred at the same temperature overnight. After 12 h, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 99:1) to yield an isomeric mixture of C3-prenylated-l-Trp-OMe (exo-11a and endo-11ain a 1:1 ratio, 262 mg, 0.41 mmol) and C2-prenylated-l-Trp-OMe (12a, 36.5 mg, 0.055 mmol) in 70% overall yield (based on recovered starting material; 35% of unreacted l-Trp-OMe was recovered).

Indole-C3-n-crotylation of l-Trp-OMe

Compound 11b was synthesized by following general procedure A, and the resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 99:1) to yield an isomeric mixture of C3-crotylated l-Trp-OMe, exo-11b, and a trace amount of the other isomer, endo-11b (in a 4.5:1 ratio, 74 mg, 0.270 mmol) in 51% overall yield based on the recovered starting material (42% of unreacted l-Trp-OMe was recovered).

Indole-C3-n-geranylation of l-Trp-OMe

Compound 11c was synthesized by following general procedure A, and the resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 93:7) to yield an isomeric mixture of C3-geranylated l-Trp-OMe, exo-11c, and endo-11c (in a 1.7:1 ratio, 42 mg, 0.144 mmol) and C2-geranylated l-Trp-OMe, 12c (12 mg, 0.034 mmol), in 32% overall yield, based on the recovered starting material; 48.2% of unreacted l-Trp-OMe was recovered.

Indole-C3-n-farnesylation of l-Trp-OMe

Compound 11d was synthesized by following general procedure A, and the resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 90:10) to yield a diastereomeric mixture of C3-farnesylated l-Trp-OMe, exo-11d, and endo-11d (in a 1.2:1 ratio, 52.5 mg, 0.124 mmol) and C2-farnesylated l-Trp-OMe, 12d (31.5 mg, 0.075 mmol) in 62% overall yield, based on 65% of the recovered starting material.

General Procedure B for Benzylation of l-Trp-OMe

Procedure

To a magnetically stirred solution of l-Trp-OMe (200 mg, 0.916 mmol, 1.0 equiv) and LiOH (44 mg, 1.83 mmol, 2 equiv) in acetic acid (10 mL) was added benzyl bromide (14) (218 μL, 1.832 mmol, 2 equiv) at RT. The resulting mixture was stirred at a temperature of 60 °C for overnight. After 12 h, the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure, and the resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 97.5:2.5) to yield a diastereomeric mixture of C3-benzylated l-Trp-OMeexo-15e and endo-15e (in a 1:1 ratio, 91 mg, 0.294 mmol) and C2-benzylated l-Trp-OMe 16e (23.7 mg, 0.076 mmol) in 60% overall yield, based on the (32.5%) recovered starting material.

4-Me-Benzylation of l-Trp-OMe

Compound 15f was synthesized by following general procedure B, and the resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 97:3) to yield a diastereomeric mixture of C3 derivatized 4-methyl benzyl l-Trp-OMeexo-15f and endo-15f (in a 1.4:1 ratio, 94 mg, 0.29 mmol) and C2 derivatized 4-methyl benzyl l-Trp-OMe 16f (40 mg, 0.124 mmol) in 84% overall yield based on the (46%) recovered starting material.

Synthesis Details for Isoprenylations of Cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP Substrates

l-Trp-N-Boc Carbamate (21)

To a magnetically stirred clear solution of l-Trp (5 g, 24.5 mmol, 1.00 equiv) in 250 mL of THF-H2O (1:1) were added Na2CO3 (6.15 g, 73.45 mmol, 3.00 equiv) and NaHCO3 (7.8 g, 73.45 mmol, 3.00 equiv). The resulting turbid solution (pH ∼10.5) was cooled to 0 °C (H2O/ice bath) and stirred for 15 min. To this mixture was added Boc anhydride (5.6 mL, 24.5 mmol, 1.00 equiv) dropwise. The resulting solution was stirred for 15–20 min at 0 °C, the ice bath was removed, and reaction was stirred at RT overnight. THF was evaporated by rotary evaporation, and the reaction mixture was acidified by addition of a 1 N aq. HCl solution. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was transferred to a separating funnel and washed and extracted three times with EtOAc. The combined organic phase was washed with brine, dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and filtered. Concentration under reduced pressure gave 6.95 g (93% yield, 22.85 mmol) of white solid, which was directly used for the next step without further purification.

l-Trp Methyl Ester Hydrochloride (22a)

Thionyl chloride (8.93 mL; 2.50 equiv, 123.0 mmol) was added dropwise to a cold (0 °C) solution of anhydrous methanol (excess) under magnetic stirring. The solution was stirred at 0 °C for 30 min, and then, l-Trp (10.0 g; 48.9 mmol, 1.00 equiv) was added, and the resulting solution was heated at 60 °C for 18 h. After evaporation of methanol in vacuo, a white residue of hydrochloride salt was obtained, which was used without further purification. Yield: 12.4 g, (48.6 mmol) 99% of l-Trp methyl ester hydrochloride. mp 91–93 °C.

Methyl-N-BOC-l-Trp-l-Trp Ester (23)

21 (5 g, 16.43 mmol, 1 equiv) and 22 (8.37 g, 32.86 mmol, 2 equiv) were suspended in anhydrous dichloromethane (250 mL). The suspension was cooled to 0 °C in ice–water bath. This was followed by addition of N,N-diisopropylethylamine (5.7 mL, 32.86 mmol, 2.00 equiv), which resulted in a clear solution. Subsequently, N-hydroxybenzotriazole monohydrate (2.77 g, 18.07 mmol, 1.1 equiv) was added to the reaction mixture, followed by addition of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide hydrochloride (3.78 g, 19.71 mmol, 1.2 equiv). The reaction was allowed to stir at 0 °C for 1 h and then at RT for 15 h. The reaction mixture was washed with saturated citric acid solution in a separating funnel, followed by washing with saturated sodium bicarbonate solution. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and was evaporated in vacuo. The compound 23 was purified using column chromatography with 35–40% EtOAc/hexanes as the eluent. mp 187–188 °C. 5.64 g, 68% yield, 11.17 mmol.

Methyl-l-Trp-l-Trp Ester–Formic Acid Salt (24)

To the magnetically stirred solution of 23 (5.64 g, 11.17 mmol, 1.00 equiv) in 50 mL of dichloromethane was added 50 mL of formic acid dropwise at RT. The reaction was allowed to stir overnight for 12 h. Subsequently, after the completion of the reaction, dichloromethane and formic acid were evaporated in vacuo, resulting in a reddish oil which was used for next step without further purification.

(3S,6S)-3,6-Bis((1H-Indol-3-yl)methyl)piperazine-2,5-dione (cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP)

A homogeneous solution (under stirring with a magnetic bar) of amine 24 was refluxed at 60 °C overnight in 14 M methanolic ammonia (pH ≈ 10, excess). The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was washed with ice-cold water and sonicated until it turned into a suspension. The suspension was vacuum-filtered and the solid was washed with ice-cold acetonitrile (10 mL), which furnished pure cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP as a white solid (3.66 g, 9.84 mmol) in 88% yield from 23.

General Procedure for n-Isoprenylation of Cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP

To the magnetically stirred solution of cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP (100 mg, 268.51 μmol, 1.00 equiv) in 5 mL of acetic acid was added NaOAc (44.1 mg, 537.02 μmol, 2.00 equiv) and prenyl bromide (62 μL, 537.02 μmol, 2.00 equiv) (or its equivalent) at RT. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir overnight, resulting in a dark-colored reaction mixture. After completion of the reaction, acetic acid was evaporated in vacuo. The resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 98:2) to yield a separable diastereomeric mixture of C3-prenylated cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP, exo-25a, and endo-25a (in a 3:1 ratio, 65.0 mg, 0.148 mmol) 55% overall yield.

Half-Gram Prenylation of Cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP (25)

To the magnetically stirred solution of cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP (500 mg, 1.34 mmol, 1.00 equiv) in 25 mL of acetic acid was added NaOAc (220.3 mg, 2.69 mmol, 2.00 equiv) and prenyl bromide (310 μL, 2.69 mmol, 2.00 equiv) at RT. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir overnight, resulting in a dark-colored reaction mixture. After completion of the reaction, acetic acid was evaporated in vacuo. The resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 98:2) to yield a separable diastereomeric mixture of C3-prenylated cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP, exo-25a, and endo-25a (in a 3:1 ratio, 307 mg, 0.698 mmol) 52% overall yield.

Geranylation of Cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP (25c and 26)

Compound 25c and 26 were synthesized by following general procedure C, and the resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 98:2) to yield a separable regioisomeric mixture (3:1) of C3-geranylated cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp, 25c (59 mg, 0.116 mmol), and C2-geranylated cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp, 26 (20 mg, 0.039 mmol) in 58% overall yield.

Farnesylation of Cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP (25d)

A mixture of compounds exo-25d and endo-25d was synthesized by following general procedure C, and the resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 98:2) to yield an inseparable diastereomeric mixture of C3-farnesylated cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp and 25d (in 7:1 ratio-based on 1H NMR analysis, 111 mg, 0.192 mmol) in 72% overall yield.

General Procedure for Benzylation of Cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP (25e and 27)

To the magnetically stirred solution of cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP (100 mg, 268.51 μmol, 1.00 equiv) in 5 mL of acetic acid was added NaOAc (44.1 mg, 537.02 μmol, 2.00 equiv) and benzyl bromide, 14 (69 μL, 537.02 μmol, 2.00 equiv), at RT. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir overnight at 50 °C. After completion of the reaction, acetic acid was evaporated in vacuo. The resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 98:2) to yield C3- and N1-dibenzylated cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp, 27 (56 mg, 0.101 mmol) and C3-benzylated cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp exo-25e in 38% overall yield and in a >10:1 ratio.

4-Me-Benzylation of Cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp DKP

A mixture of compounds exo-25f and 28 was synthesized by following general procedure D: the reaction was carried out at 50 °C, and the resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 98:2) to yield an inseparable mixture of C3 4-Me-benzylated cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp exo-25f and C3 and N-indole 4-Me-benzylated cyclo-l-Trp-l-Trp 28 (≈1:1 mixture determined by 1H NMR analysis, 64 mg of the mixture) in 45% overall yield.

tert-Butyl (S)-2-(((S)-3-(1H-Indol-3-yl)-1-methoxy-1-oxopropan-2-yl)carbamoyl)pyrrolidine-1-carboxylate (30)

Boc-proline 29 (4 g, 18.58 mmol, 1 equiv) and HCl salt of l-Trp-OMe (7.10 g, 27.87 mmol, 1.5 equiv) were suspended in anhydrous dichloromethane (200 mL). The suspension was cooled to 0 °C in ice–water bath. This was followed by addition of N,N-diisopropylethylamine (6.5 mL, 37.18 mmol, 2.00 equiv), which resulted in a clear solution. Subsequently, N-hydroxybenzotriazole monohydrate (3.42 g, 22.30 mmol, 1.2 equiv) was added to the reaction mixture, followed by addition of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride (4.27 g, 22.30 mmol, 1.2 equiv). The reaction was allowed to stir at 0 °C for 1 h and then at RT for 15 h. The reaction mixture was washed with saturated citric acid solution in a separating funnel, followed by washing with saturated sodium bicarbonate solution. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate and was evaporated in vacuo. The compound 30 was purified using column chromatography with 35–40% EtOAc/hexanes as the eluent. Yield; 6.1 g, 79%.

Methyl l-Pro-l-Trp Formic Acid Salt (31)

To the magnetically stirred solution of 30 (6.0 g, 14.44 mmol, 1.00 equiv) in 50 mL of dichloromethane was added 50 mL of formic acid dropwise at RT. The reaction was allowed to stir overnight for 12 h. Subsequently, after the completion of the reaction, dichloromethane and formic acid were evaporated in vacuo, resulting in a reddish oil, which was used for the next step without further purification.

(3S,8aS)-3-((1H-Indol-3-yl)methyl)hexahydropyrrolo[1,2-a]pyrazine-1,4-dione (Cyclo-l-Trp-l-Pro DKP) (32)

A homogeneous solution (under stirring with a magnetic bar) of amine 31 was refluxed at 60 °C overnight in 14 M methanolic ammonia (pH ≈ 10, excess). The solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was washed with ice-cold water and sonicated until it turned into a suspension. The suspension was vacuum-filtered and the solid was washed with ice-cold acetonitrile (10 mL × 3), which furnished pure cyclo-l-Trp-l-Pro DKP (32) as a white solid (2.62 g, 9.24 mmol) in 64% yield from 30 as the starting material.

Prenylation of Cyclo-l-Trp-l-Pro DKP (32)

To the magnetically stirred solution of 32 (100 mg, 352.94 μmol, 1.00 equiv) in 5 mL of acetic acid was added NaOAc (58.0 mg, 705.90 μmol, 2.00 equiv) and prenyl bromide (82 μL, 705.90 μmol, 2.00 equiv) at RT. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir overnight, resulting in a dark-colored reaction mixture. After completion of reaction, acetic acid was evaporated in vacuo. The resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 99:1) to yield products 33 (52 mg, 0.124 mmol), 34a, and 35a (28 mg, 0.08 mmol) 58% overall yield.

Farnesylation of Cyclo-l-Trp-l-Pro DKP

To the magnetically stirred solution of 32 (100 mg, 352.94 μmol, 1.00 equiv) in 5 mL of acetic acid were added NaOAc (58.0 mg, 705.90 μmol, 2.00 equiv) and farnesyl bromide (191 μL, 705.90 μmol, 2.00 equiv) at RT. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir overnight, resulting in a dark-colored reaction mixture. After completion of the reaction, acetic acid was evaporated in vacuo. The resultant residue was purified by column chromatography (DCM/MeOH 99:1) to yield a mixture of the products exo-34b (40 mg, 0.08 mmol), endo-34b, and 35b (55 mg, 0.113 mmol) in 55% overall yield.

Acknowledgments

R.V. and A.L.L. thank financial support from the NSF Grant: CHE1709655; R.V. thanks the DST-SERB for a CRG Award [Org. Chem.]: CRG/2020/005008. R.V. thanks the IISER Tirupati for financial assistance; S.J. thanks the DST-India for the INSPIRE-SHE fellowship; K.A. thanks the CSIR-JRF (17/12/2017 (ii) EU-V) for the fellowship; Authors thank Dr. Sasikumar (IISER Tirupati) for NMR data and Satish Mutyam (IISER Tirupati) for ESI-MS data acquisition. Authors thank Dona Maria Vincent and Harish Pemmiraju for their helpful discussions.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c00515.

1H and 13C NMR spectral copies for all new compounds and additional spectroscopic data (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- For a review chapter, see: Williams R. M.; Stocking E. M.; Sanz-Cervera J. F.. Biosynthesis of Prenylated Alkaloids Derived from Tryptophan. In Biosynthesis: Aromatic Polyketides, Isoprenoids, Alkaloids; Leeper F. J., Vederas J. C., Eds.; Springer: Germany, 2000; Vol. 195, pp 97–173. and [Google Scholar]; Wallwey C.; Li S.-M. Ergot alkaloids: structure diversity, biosynthetic gene clusters and functional proof of biosynthetic genes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 496–510. 10.1039/c0np00060d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borthwick A. D. 2,5-Diketopiperazines: Synthesis, Reactions, Medicinal Chemistry, and Bioactive Natural Products. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 3641–3716. 10.1021/cr200398y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For state-of-the-art methods, see:; a Trost B. M.; Bai W.-J.; Hohn C.; Bai Y.; Cregg J. J. Palladium-Catalyzed Asymmetric Allylic Alkylation of 3-Substituted 1H-Indoles and Tryptophan Derivatives with Vinylcyclopropanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 6710–6717. 10.1021/jacs.8b03656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tu H.-F.; Zhang X.; Zheng C.; Zhu M.; You S.-L. Enantioselective dearomative prenylation of indole derivatives. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 601–608. 10.1038/s41929-018-0111-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Zheng C.; You S.-L. Catalytic asymmetric dearomatization (CADA) reaction-enabled total synthesis of indole-based natural products. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2019, 36, 1589–1605. 10.1039/c8np00098k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Hang Q. Q.; Liu S. J.; Yu L.; Sun T. T.; Zhang Y. C.; Mei G. J.; Shi F. Design and Application of Indole-Based Allylic Donors for Pd-Catalyzed Decarboxylative Allylation Reactions †. Chin. J. Chem. 2020, 38, 1612–1618. 10.1002/cjoc.202000104. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; e Gao F.; Zhang Y.-C.; Shi F.; Lan J.-P.; Lu Y.-N.; Chen K.-W.; Jiang F. Catalytic Asymmetric Substitution Reaction of 3-Substituted 2-Indolylmethanols with 2-Naphthols. Synthesis 2020, 52, 3684–3692. 10.1055/s-0040-1707237. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; f Zhang Y.-C.; Jiang F.; Shi F. Organocatalytic Asymmetric Synthesis of Indole-Based Chiral Heterocycles: Strategies, Reactions, and Outreach. Acc. Chem. Res. 2020, 53, 425–446. 10.1021/acs.accounts.9b00549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Neto J. S. S.; Zeni G. Recent Advances in the Synthesis of Indoles from Alkynes and Nitrogen Sources. Org. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 155–210. 10.1039/c9qo01315f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Sheng F.-T.; Wang J.-Y.; Tan W.; Zhang Y.-C.; Shi F. Progresses in organocatalytic asymmetric dearomatization reactions of indole derivatives. Org. Chem. Front. 2020, 7, 3967–3998. 10.1039/d0qo01124j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; i Cheng Y.-Z.; Zhao Q.-R.; Zhang X.; You S.-L. Asymmetric Dearomatization of Indole derivatives with N-Hydroxycarbamates enabled by photoredox catalysis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 18069–18074. 10.1002/anie.201911144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Wan X.; Sun M.; Wang J.-Y.; Yu L.; Wu Q.; Zhang Y.-C.; Shi F. Regio- and enantioselective ring-opening reaction of vinylcyclopropanes with indoles under cooperative catalysis. Org. Chem. Front. 2021, 8, 212–223. 10.1039/d0qo00699h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- a Representative examples:Ruchti J.; Carreira E. M. Ir-Catalyzed Reverse Prenylation of 3-Substituted Indoles: Total Synthesis of (+)-Aszonalenin and (−)-Brevicompanine B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 16756–16759. 10.1021/ja509893s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Di Gregorio G.; Mari M.; Bartoccini F.; Piersanti G. Iron-Catalyzed Direct C3-Benzylation of Indoles with Benzyl Alcohols through Borrowing Hydrogen. J. Org. Chem. 2017, 82, 8769–8775. 10.1021/acs.joc.7b01603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhang H.; Hu R.-B.; Liu N.; Li S.-X.; Yang S.-D. Dearomatization of Indoles via Palladium-Catalyzed Allylic C-H Activation. Org. Lett. 2016, 18, 28–31. 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ye Y.; Kevlishvili I.; Feng S.; Liu P.; Buchwald S. L. Highly Enantioselective Synthesis of Indazoles with a C3-Quaternary Chiral Center Using CuH Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142, 10550–10556. 10.1021/jacs.0c04286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Mitchell M. O.; Le Quesne P. W. Total synthesis of (+) pseudophrynaminol. Tetrahedron Lett. 1990, 31, 2681–2684. 10.1016/s0040-4039(00)94671-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For a seminal report, see:Austin J. F.; Kim S.-G.; Sinz C. J.; Xiao W.-J.; MacMillan D. W. C. Asymmetric Catalysis Special Feature Part I: Enantioselective organocatalytic construction of pyrroloindolines by a cascade addition-cyclization strategy: Synthesis of (-)-flustramine B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2004, 101, 5482–5487. 10.1073/pnas.0308177101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Representative total syntheses and related studies are listed in Supporting Information: Section S4 (Additional Refs.). Representative biosynthetic studies:; a Wallwey C.; Li S.-M. Ergot alkaloids: structure diversity, biosynthetic gene clusters and functional proof of biosynthetic genes. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 496–510. 10.1039/c0np00060d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Coyle C. M.; Cheng J. Z.; O’Connor S. E.; Panaccione D. G. An Old Yellow Enzyme Gene Controls the Branch Point between Aspergillus fumigatus and Claviceps purpurea Ergot Alkaloid Pathways. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 3898–3903. 10.1128/aem.02914-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Ding Y.; Williams R. M.; Sherman D. H. Molecular Analysis of a 4-dimethylallyltryptophan Synthase from Malbranchea aurantiaca. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283, 16068–16076. 10.1074/jbc.m801991200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Li S.-M. Prenylated indole derivatives from fungi: structure diversity, biological activities, biosynthesis and chemoenzymatic synthesis. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2010, 27, 57–78. 10.1039/b909987p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Jakubczyk D.; Cheng J. Z.; O’Connor S. E. Biosynthesis of the ergot alkaloids. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2014, 31, 1328–1338. 10.1039/c4np00062e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Edwards D. J.; Gerwick W. H. Lyngbyatoxin Biosynthesis: Sequence of Biosynthetic Gene Cluster and Identification of a Novel Aromatic Prenyltransferase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 11432–11433. 10.1021/ja047876g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Geissen T. W.; von Tesmar A. M.; Marahiel M. A. A tRNA-dependent two-enzyme pathway for the generation of singly and doubly methylated ditryptophan 2,5-diketopiperazine. Biochemistry 2013, 52, 4274–4283. 10.1021/bi4004827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Liu J.; Xie X.; Li S.-M. Guanitrymycin biosynthetic pathways imply cytochrome P450 mediated regio- and stereospecific guaninyl transfer reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 11534–11540. 10.1002/anie.201906891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Li H.; Qiu Y.; Guo C.; Han M.; Zhou Y.; Feng Y.; Luo S.; Tong Y.; Zheng G.; Zhu S. Pyrroloindoline cyclization in tryptophan-containing cyclodipeptides mediated by an unprecedented indole C3 methyltransferase from Streptomyces sp. HPH0547. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 8390–8393. 10.1039/c9cc03745d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raju R.; Piggott A. M.; Huang X.-C.; Capon R. J. Nocardioazines: A novel bridged diketopiperazine scaffold from a marine-derived bacterium inhibits P-glycoprotein. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 2770–2773. 10.1021/ol200904v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Koh J.; Itahana Y.; Mendenhall I. H.; Low D.; Soh E. X. Y.; Guo A. K.; Chionh Y. T.; Wang L.-F.; Itahana K. ABCB1 protects bat cells from DNA damage induced by genotoxic compounds. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 2820. 10.1038/s41467-019-10495-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Robey R. W.; Bates S. E.; Gottesman M. M.; et al. Revisiting the Role of ABC Transporters in Multidrug-Resistant Cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 452–464. 10.1038/s41568-018-0005-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Thandavamurthy K.; Sharma D.; Porwal S. K.; Ray D.; Viswanathan R. Regioselective Cope Rearrangement and Prenyl Transfers on Indole Scaffold Mimicking Fungal and Bacterial Dimethylallyltryptophan Synthases. J. Org. Chem. 2014, 79, 10049–10067. 10.1021/jo501651z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Alqahtani N.; Porwal S. K.; James E. D.; Bis D. M.; Karty J. A.; Lane A. L.; Viswanathan R. Synergism between Genome Sequencing, Tandem Mass Spectrometry and Bio-Inspired Synthesis Reveals Insights into Nocardioazine B Biogenesis. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015, 13, 7177–7192. 10.1039/c5ob00537j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S.; Shiomi S.; Ishikawa H. Bioinspired Indole Prenylation Reactions in Water. J. Nat. Prod. 2017, 80, 2371–2378. 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James E. D.; Knuckley B.; Alqahtani N.; Porwal S.; Ban J.; Karty J. A.; Viswanathan R.; Lane A. L. Two Distinct Cyclodipeptide Synthases from a Marine Actinomycete Catalyze Biosynthesis of the Same Diketopiperazine Natural Product. ACS Synth. Biol. 2016, 5, 547–553. 10.1021/acssynbio.5b00120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebler J. C.; Poulter C. D. Purification and characterization of dimethylallyl tryptophan synthase from Claviceps purpurea. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1992, 296, 308–313. 10.1016/0003-9861(92)90577-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bocchi V.; Casanati G.; Marchelli R. Insertion of isoprene units into indole and 3-substituted indoles in aqueous systems. Tetrahedron 1978, 34, 929–932. 10.1016/0040-4020(78)88141-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Representative example:Caballero E.; Avendaño C.; Menéndez J. C. Brief Total Synthesis of the Cell Cycle Inhibitor Tryprostatin B and Related Preparation of Its Alanine Analogue. J. Org. Chem. 2003, 68, 6944–6951. 10.1021/jo034703l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mari M.; Lucarini S.; Bartoccini F.; Piersanti G.; Spadoni G. Synthesis of 2-substituted tryptophans via a C3- to C2-alkyl migration. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2014, 10, 1991–1998. 10.3762/bjoc.10.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Che Q.; Zhu T.; Keyzers R. A.; Liu X.; Li J.; Gu Q.; Li D. Polycyclic Hybrid Isoprenoids from a Reed Rhizosphere Soil Derived Streptomyces sp. CHQ-64. J. Nat. Prod. 2013, 76, 759–763. 10.1021/np3008864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wang M.; Feng X.; Cai L.; Xu Z.; Ye T. Total Synthesis and absolute configuration of Nocardioazine B. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 4344–4346. 10.1039/c2cc31025b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wang H.; Reisman S. E. Enantioselective total synthesis of (-)-Lansai B and (+)-Nocardioazine A and B. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 6206. 10.1002/anie.201402571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Shen X.; Zhao J.; Xi Y.; Chen W.; Zhou Y.; Yang X.; Zhang H. Enantioselective Total Synthesis of (+)-Nocardioazine B. J. Org. Chem. 2018, 83, 14507–14517. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b02329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Scholz U.; Winterfeldt E. Biomimetic synthesis of alkaloids (1980 to 1999). Nat. Prod. Rep. 2000, 17, 349–366. 10.1039/a902278c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Schardl C. L.; Panaccione D. G.; Tudzynski P.. Ergot alkaloids—Biology and Molecular Biology. In Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology; Cordell G. A., Ed.; Academic Press, Elsevier: Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2006; Vol. 63, pp 45–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- For classic study, see:Tsai H. F.; Wang H.; Gebler J. C.; Poulter C. D.; Schardl C. L. The Claviceps purpurea Gene Encoding Dimethylallyltryptophan Synthase, the Committed Step for Ergot Alkaloid Biosynthesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 216, 119–125. 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebler J. C.; Woodside A. B.; Poulter C. D. Dimethylallyltryptophan synthase. An enzyme-catalyzed electrophilic aromatic substitution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992, 114, 7354–7360. 10.1021/ja00045a004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- For key studies and seminal reviews:; a Walsh C. T. Biological Matching of Chemical Reactivity: Pairing Indole Nucleophilicity with Electrophilic Isoprenoids. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014, 9, 2718–2728. 10.1021/cb500695k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Li S.-M. Evolution of aromatic prenyltransferases in the biosynthesis of indole derivatives. Phytochemistry 2009, 70, 1746–1757. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2009.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mahmoodi N.; Qian Q.; Luk L. Y. P.; Tanner M. E. Rearrangements in the mechanisms of the indole alkaloid prenyltransferases. Pure Appl. Chem. 2013, 85, 1935–1948. 10.1351/pac-con-13-02-02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; b Tanner M. E. Mechanistic studies on the indole prenyltransferases. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2015, 32, 88–101. 10.1039/c4np00099d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Rudolf J. D.; Wang H.; Poulter C. D. Multisite Prenylation of 4-Substituted Tryptophans by Dimethylallyltryptophan Synthase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 1895–1902. 10.1021/ja310734n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Zhou K.; Zhao W.; Liu X.-Q.; Li S. -M. Saturation mutagenesis on Tyr205 of the cyclic dipeptide C2-prenyltransferase FtmPT1 results in mutants with strongly increased C3-prenylating activity. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 9943–9953. 10.1007/s00253-016-7663-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.