Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) often results in pneumonia and can lead to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). ARDS is one of the most significant causes of death in patients with COVID-19. The development of a “cytokine storm” in patients with COVID-19 causes progression to ARDS. In this scoping review, we investigated the effect of pro-inflammatory cytokines in inducing moderate and severe ARDS outcomes. A comprehensive search was performed using PubMed and Google Scholar to implement a broad query that captured all the relevant studies published between December 2019 and September 2020.We identified seven studies that evaluated the immune response in COVID-19 patients with ARDS. The white blood cell counts (WBCs), CRP, and IL-6 were higher in the moderately presenting ARDS patients, critically ill patients, and those with more severe ARDS. This study may contribute to better patient management and outcomes if tailored immune marker interventions are implemented in the near future.

Keywords: Immunological response, ARDS, COVID-19, cytokines

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become one of the most common causes of death within the last year, especially among the elderly, immunocompromised patients, and patients with preexisting conditions, including cardiovascular disease and respiratory illnesses [1]. Further, there are a large number of COVID-19 patients who have presented with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [2]. ARDS causes alveolar injury in the lung tissue by forming hyaline membranes in the alveoli, which may lead to widening in the interstitial tissue, edema, and fibroblast activation [2]. COVID-19 causes the same pathological change consequences of ARDS, which may eventually lead to lung fibrosis [2].

Viral pneumonia and its progression toward the development of ARDS stands as one of the prominent causes of death [3,4]. A maladaptive immune response to COVID-19 has been labeled “cytokine storm” and is thought to present as a sudden, excessive production of pro-inflammatory cytokines during the disease course [5,6]. The several numbers of cytokines have been linked to development or progression of ARDS, which in-turn is associated with further systemic inflammation, multi-system tissue damage, multiple organ failure, and death [5,6].

The most common proposed COVID-19 pathogenesis is that the virus initiates the disease by entering the epithelial cells through the Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors. In response, immune cells recognize either the virus or its receptor through a pathogen-recognition receptor (PRR) that leads to the activation of cellular and humoral immunity [7,8]. Consequently, induction of various immune cells, such as macrophages, CD4+, and CD8+ cells, leads to the production of cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-1 β), which are predicted to be associated with the clinical outcome of the disorder [[9], [10], [11]]. The SARS-CoV-2 virus enters the cell through the Toll-like receptor-7 (TLR-7) in the endosomes, but this activates mainly IL-6, IL-12, IL-8, and TNFα, which induce CD8 and CD4 activation [12]. Finally, there is a lack of knowledge examining the effect of pro-inflammatory cytokines in inducing severe and moderate ARDS outcomes.

We know that immunological response in ARDS patients leads to an early exudative stage, causing alveolar damage and destruction of the epithelium and endothelium cells. We do not know how COVID-19 induces the immune response in critically ill patients across ARDS stages. Therefore, this review aims to explore the role of immune response in COVID-19 patients with ARDS.

Methods

This scoping review was performed based on Arksey and O’Malley’s five-stage framework [13] and includes the following stages: (1) specifying the research question, (2) identifying the related studies, (3) selecting the relevant studies, (4) charting the data, and (5) summarizing and reporting the findings. The research aim was to explore the immunological response in COVID-19 patients with ARDS (Table 1, Table 2 ).

Table 1.

Overview of the demographic characteristic of the included studies.

| Author | Country | Study design | Sample size/population | Age group | Sex |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dreher, 2020 | University hospital in Aachen, Germany) | Cross-sectional | 50 COVID-19 Patients | 58–76 (median 65) | Female: 17 (34%) |

| Male: 33 (66%) | |||||

| Chen, 2020 | Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology | Retrospective observational study | 21 confirmed COVID-19 cases | 50−65 | Female: 4 (19%) |

| Male: 17 (81%) | |||||

| Hou, 2020 | Tongji Hospital, Wuhan, China. | N/A | 389 hospitalized patients with COVID-19 | 61.3 ± 13.8 | Female: 189 (48.6%) |

| Male: 200 (51.4%) | |||||

| Huang, 2020 | Wuhan, China | Cross-sectional | 41 COVID-19 pts; 13 ICU vs. 28 non-ICU | 41−58 | Male: 30 (73%) |

| Female: 11 (27%) | |||||

| Liu, 2020 | Wuhan Union Hospital, China. | Retrospective observational study | All: 40 | 48.7 ± 13.9 | Male: 15 (37.5%) |

| Mild: 27 | Female: 25 (62.5%) | ||||

| Severe: 13 | |||||

| Wan, 2020 | Chongqing University, Three Gorges Hospital, China | Cross-sectional | All: 123 | 15−82 | Male: 15 (37.5%) |

| Mild: 102 | Female: 25 (62.5%) | ||||

| Severe: 21 | |||||

| Zheng, 2020 | tertiary teaching hospital in Hangzhou (Zhejiang Province, China) | Retrospective study | Total: 34 patients. | 51–83 (median 66) | Male: 23 (67.6%) |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV): 15. | Female: 11 (32.4%) | ||||

| Noninvasive ventilation (NIV): 19 |

Table 2.

Overview of the lab findings of the included studies.

| Author | Lab Findings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dreher, 2020 | All patients (N = 50) 6.7 (4.9–9.6) | Non-ARDS patients (N = 26) | ARDS patents (N = 24) | |

| WBC | 94 (28–173) | 5.8 (4.1–7) | 9.2 (6.3–11.6) | |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 122 (68–333) | 37 (15–113) | 110 (7–264) | |

| Interleukin-6 (pg/mL) | 10 (0–60) | 119 (47–338) | ||

| Chen, 2020 | All patients (N = 21) | Moderate patients (N = 10) | Severe patents (N = 11) | |

| WBC | 5.7 (4.6–8.3) | 4.5 (3.9–5.5) | 8.3 (6.2–10.4) | |

| C-reactive protein (mg/L) | 108.4(28–139.5) | 22 (14.7–119.4) | 139.4 (86.9–165.1) | |

| Interleukin-6 (pg/mL) | 26.6 (7.5−43.4) | 15.3 (6.2−29.5) | 41.5 (24.8−114.2) | |

| Hou, 2020 | Odd ratio for severe COVID-19 | OR (97·5% CI = 2·5%) | P-value | |

| IL-1β | 1·0379 | 0·9739 1·1062 | 0·2515 | |

| IL-2R | 0·9993 | 0·9983 1·0004 | 0·2078 | |

| IL-6 | 1·0000 | 0·9903 1·0097 | 0·9936 | |

| IL-8 | 0·9985 | 0·9929 1·0041 | 0·5934 | |

| IL-10 | 1·0163 | 0·9769 1·0573 | 0·4234 | |

| TNF-α | 1·0115 | 0·9443 1·0834 | 0·7450 | |

| Lymphocyte | 1·2623 | 0·7412 2·1499 | 0·3911 | |

| Neutrophil | 1·0638 | 0·9467 1·1953 | 0·2986 | |

| PCT | 2·5333 | 0·7287 8·8067 | 0·1437 | |

| IL-2R/lymphocytes | 1·0013 | 1·0005 1·0021 | 0·0020 | |

| CRP | 1·0085 | 1·0008 1·0163 | 0·0300 | |

| Ferritin | 1·0006 | 1·0001 1·0010 | 0·0206 | |

| Huang, 2020 | All patients (n = 41) | All patients (n = 41) | No ICU care (n = 28) | ICU care (n = 13) |

| White blood cell count, ×109 L−1 | 6·2 (4·1–10·5) | 5·7 (3·1–7·6) | 11·3 (5·8–12·1) | |

| Neutrophil count, ×109 L−1 | 5·0 (3·3–8·9) | 4·4 (2·0–6·1) | 10·6 (5·0–11·8) | |

| Lymphocyte count, ×109 L−1 | 0·8 (0·6–1·1) | 1·0 (0·7–1·1) | 0·4 (0·2–0·8) | |

| Liu, 2020 | No ICU care (n = 28) | Mild Cases | Severe Cases | |

| IL-6 (pg/mL) | 5·7 (3·1–7·6) | 25 | 75 | |

| IL-10 (pg/mL) | 4·4 (2·0–6·1) | 3 | 4 | |

| IL-2 (pg/mL) | 1·0 (0·7–1·1) | 1.8 | 2.3 | |

| IL-4 (pg/mL) | 1.7 | 2 | ||

| TNF-α (pg/mL) | 2 | 2 | ||

| IFN-γ (pg/mL) | 2 | 2 | ||

| Wan, 2020 | Mild (mean [SD]) | Severe (mean [SD]) | ||

| CD4 | (451∙3 [23∙0]) | (263∙2 [28∙83]) | ||

| CD8 | (288∙6 [14∙23]) | (179 [23∙87]) | ||

| B cell | (166 [11∙98]) | (125∙3 [13∙49]) | ||

| NK cell | (147 [10∙36]) | (119∙6 [16∙500]) | ||

| CD4/ CD8 | (1∙671 [0∙059]) | (1∙509 [0∙170]) | ||

| IL-4 | (1∙69 [0∙070]) | (1∙83 [0∙185]) | ||

| IL-6 | (13∙41 [1∙84]) | (37∙77 [7∙801]) | ||

| IL-10 | (2∙464 [0∙085]) | (4∙59 [0∙378]) | ||

| IL-17 | (1∙095 [0∙0226]) | (1∙16 [0∙0571]) | ||

| TNF-α | (4∙077 [1∙588]) | (2∙948 [0∙443]) | ||

| IFN-γ | (5∙132 [0∙841]) | (6∙904 [1∙247]) | ||

| Zheng, 2020 | All Patients (n = 34). | IMV (n = 15) | NIV (n = 19) | |

| WBC (4–10/nL) | 8.9 (5.3, 14.3) | 6.2 (4.4, 13.5) | 9.3 (6.6, 16.0) | |

| C-reactive protein (0–8 mg/L) | 48 (27, 88) | 50 (39, 52) | 46 (27, 103) | |

| Interleukin-6 (0–7 pg/L) | 47 (24, 81) | 65 (38, 202) | 38 (12, 72) | |

| IL-10 (0.0–2.3 pg/mL) | 6.7 (4.4, 9.0) | 7.0 (5.2, 9.7) | 5.5 (3.1, 8.8) | |

| Neutrophil count ((×109 L−1) 2.0–7.0) | 7.8 (4.3, 13.2) | 5.7 (3.6, 12.8) | 8.0 (5.5, 14.8) | |

| Lymphocyte count ((×109 L−1) 0.8–4.0) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.9) | 0.5 (0.4, 0.8) | 0.6 (0.5, 0.9) |

Eligibility criteria and search strategy

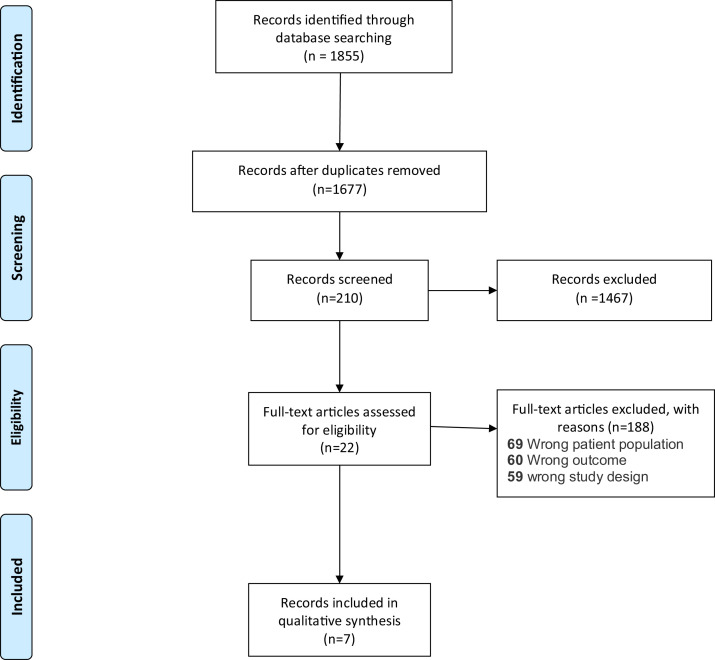

A comprehensive search was performed using PubMed and Google Scholar. Broad queries were used to capture all the relevant studies published between December 2019 and November 2020. We included studies that had the following criteria: patients infected with ARDS who have been infected with COVID-19 and have reported immune data (cells and markers) (see Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the selection process and the study search results.

From: Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med 6(7): e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097.

Study selection

Irrelevant studies were excluded after reviewing titles, abstracts, and the full test. Animal studies, non-original studies (reviews), and studies including children 14 years old and younger were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data extraction and synthesis were performed by using Covidence software. The EndNote reference file was imported first. Then, title and abstract screening and a full-text review were independently performed by two reviewers. Conflicts occurring during this phase were resolved by a third reviewer. The last phase was data extraction and synthesis of each of the eligible articles. We extracted and summarized information from the full text, including the primary bibliography, setting (country), study aims, research questions, study design, sample size/populations, age group, gender, ARDS stage, normal immune factor values, immune outcomes, lab findings, and finally, clinical findings (mortality, morbidity, length of stay, and mechanical ventilation). More information regarding all the information relevant to the data screening and extraction can be found in Table 1.

Results

This scoping review identified seven studies that evaluated the immune response in COVID-19 patients with ARDS. The age groups for the individuals who were included in the studies ranged from 15 to 83 years old. Of the seven studies analyzed, four studies were retrospective and three were cross-sectional. The sample sizes of the included studies ranged from 21 to 389 participants.

The included studies identified associations between elevated white blood cell counts (WBCs), C-reactive protein (CRP), neutrophils, IL-6, and TNFα levels in patients with severe ARDS acuity. Three studies indicated the WBC level was higher among those who were critically ill or were diagnosed with moderate or severe ARDS [[14], [15], [16]]. However, one study identified associations between low WBCs in patients requiring MV compared to those requiring noninvasive ventilation [17].

Three studies showed that elevated CRP levels in sever ARDS patients [[14], [15], [16]]. Moreover, six studies found that IL-6 was higher in moderate ARDS patients, critically ill patients, and those with more severe ARDS [14,[16], [17], [18], [19], [20]]. It also showed that IL-6 was higher among patients who were on MV compared to those who were on noninvasive ventilation [20]. Moreover, some studies have indicated a log fold noticeable increase in IL-2R with more severe ARDS participants on admission in comparison normal individuals [9,17,18].

Conversely, neutrophils counts were less in severe ARDS Patients. Patients requiring noninvasive ventilation (NIV) have higher levels of neutrophils than patients on invasive MV and those with more critical cases of ARDS [18,20]. On the other hand, IL-4 and IL-10 have been found to increase, from the time of hospital admission to discharge, in severe ARDS patients compared to non-severe ARDS patients [[18], [19], [20]].

Discussion

This review was conducted to explore the available literature on immunological response to the COVID-19 infection during ARDS severity. In a recent study, ARDS pathology has been investigated to show that ARDS can occur in three different stages. The first stage, also known as the acute phase, can be defined by the presence of alveolar edema. Furthermore, there is evidence that at this stage epithelial injury can occur that leads to the stripping of the alveolar epithelium. The subacute phase of ARDS is often associated with epithelial repair through proliferation of alveolar epithelial cells, while the chronic phase is distinguished by the attempts in repair and the loss of neutrophil infiltration. Further, within the chronic stage macrophages are present within the alveoli for ongoing epithelial repair, however there is evidence to show onset of fibrosis [21]. In our analysis, elevated WBCs, CRP, neutrophils, IL-6, and TNFα were associated with ARDS. Through cross examination of different studies conducted, this study can add valuable information for future studies that want to further investigate the immune response in COVID-19 patients with regard to the ARDS conditions.

Following infection of a host cell, sequential interactions with immune cells that include B/T cells, macrophages, and antigen presenting cells results in the release of cytokines which in turn activates more WBCs. Such activation through a positive feedback loop is accompanied by enhanced production of cytokines leading to pro-inflammatory conditions that can possibly induce systematic inflammation [22].

Recently, emerging schools of thought have sought to immunophenotype or endotype COVID-19 and its sequelae [5,6,[23], [24], [25]]. IL-6 represents a primary, upregulated pro-inflammatory cytokine in moderate and severe cases [9,14,17,18]. Our scoping review identified elevated IL-6 levels in cases with increased severity of ARDs in contrast to cases that have not progressed to ARDs, findings that are similar to other published results [14,16,17]. Several clinical trials have targeted IL-6 in COVID-19 using monoclonal antibody therapeutics including Tocilizumab and sarilumab [[26], [27], [28], [29]]. In a randomized controlled trial across 12 public and private Indian hospitals, Tocilizumab was administered to investigate whether this treatment would have an effect of COVID-19 progression. Patients were assigned to two groups that either received Tocilizumab with standard care or standard care alone. Recruited patients were studied for a 14-day period to determine if Tocilizumab had positive results compared to standard care that included the administration of corticosteroids and antiviral medication. Disease progression was monitored in the primary endpoint (up to day 14) and showed that administration of Tocilizumab with standard care did not have a positive effect and progression in both groups was not statistically significant. However, the study suggests that patients with severe disease manifestations at hospitalization that are treated with Tocilizumab could have a reduced disease progression that leads to death [28]. Interestingly, a similar study that investigated the efficacy of Tocilizumab treatment to monitor disease progression to mechanical ventilation was assessed among patients that were defined as high-risk groups as well as minority groups. Two groups were involved in the randomized trial that included Tocilizumab treatment or placebo treatment with standard care. This study differed from the previous study by the enrolment of patients from different countries that allowed this study is investigate Tocilizumab treatment globally. Following Tocilizumab treatment, it was suggested that disease progression to mechanical ventilation is reduced in Tocilizumab group compared to the placebo group [30]. Similarly, in a different study that included patients from different countries but utilized a different IL-6 inhibitor (Sarilumab), the randomized trail suggests that Sarilumab treatment did not positively affect disease progression [31]. The efficacy of IL-6 inhibitors as therapeutic treatment for COVID-19 is variable. Indeed, in a study that recruited patients from various hospitals in the Boston area randomly assigned patients to standard care and either Tocilizumab or placebo treatment. Disease progression was also monitored to assess the efficacy of this treatment to reduce intubation. Unfortunately, this study suggests that IL-6 blockade did not have an effect on the requirement for intubation. In addition, this study also suggests that Tolicizumab treatment did not have positive effect on disease progression, nor the patient need for supplemental oxygen [26]. As a result, the previous randomized trial studies have clear discrepancies that can provide clear evidence that Tolicizumab can be administered to COVID-19 patients to improve patient outcome. This can be related to the limitations within these studies that included different standard care protocols of which patients had already been treated with corticosteroids thus possibly masking positive effects of IL-6 blockade.

TNFα is a potent pro-inflammatory cytokine produced by macrophages, monocytes, lymphocytes, neutrophils, and smooth muscle, and classically, has played a critical role in cytokine storm [15]. Our findings that elevated TNFα was associated with ARDS severity in COVID-19 mirror findings by other investigators [6,[15], [16], [17], [18], [19],22,23]. However, the targeting of TNFα as a treatment to alleviate the cytokine storm may not be beneficial. Despite the association of TNFα with ARDS, the treatment to neutralize TNFα could prove deadly. Indeed, in a study that utilized the neutralization of TNFα through a fusion protein (TNFR:Fc) suggested that this treatment was associated an increased mortality rate. Further, the study suggests that fusion protein treatment to neutralize TNFα could actually elongate the inflammation response the fusion protein could act as an intravascular carrier of TNFα [32]. Thus, although our study and previous studies identifies TNFα is associated with ARDS, treatment against would not prove beneficial for COVID-19 patients. This does not suggest that TNFα should be overlooked, but rather investigated further.

Our study also identified IL-2 and IL-17 cytokines were elevated in COVID-19 with ARDS in comparison to COVID-19 without ARDS [9,15,18,22,23]. Following induction of an immune response and through activation of CD4+ T cells, IL-2 secretion by activated T cells allows for expansion of effector T cells. Furthermore, IL-2 is also involved in the maintenance of regulatory T cells through low concentrations of IL-2 [33]. IL-17, a cytokine that has been implicated in innate immunity, plays an important role in the mobilization and activation of neutrophils. As such, this cytokine is suggested to have both positive and negative effects by either providing immunity to pathogens or complicating inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis [34]. Indeed, IL-17 production has been implicated to affect downstream pro-inflammatory molecules, that include IL-6, as well as promote production of neutrophil chemoattractants [35], thus IL-17 can be implicated in facilitating the cytokine storm. As mentioned previously with IL-6, cytokines can be targeted for therapeutic treatment. Secukinumab has been used to target IL-17A and has been used to treat moderate psoriasis [36]. Proving to be effective against psoriasis, Secukinumab treatment in COVID-19 patients with ARDS can prove beneficial to stop downstream production of inflammatory cytokines as well as stop recruitment of neutrophils.

IL-10 is an anti-inflammatory cytokine produced by many immune cells, including lymphocytes and macrophages. One study suggested that IL-10 plays a significant regulatory role in respiratory infections [37]. This correlates with our findings [9,18,19], except in noninvasive ventilation in a Zheng et al. study group [20]. Other studies reported that IL-10 increased with the disease progression [6,15,22,24] and have noted cellular changes in COVID-19 cases [6,22].

Some of our reviewed papers have reported an increase in WBCs in severe in comparison to non-severe cases [14,17,18], whereas Zheng et al. reported lower WBC levels in MV in comparison to NIV [20]. Lymphopenia was shown to occur in the majority of COVID-19 cases [6,9,14,15,18,22]. This may be explained by T cell exhaustion in which prolonged antigen stimulation results in the loss of function in effector cells [20].

We acknowledge several limitations in our scoping review that encompassed seven studies. First, our study was limited to using only two databases (Google Scholar and PubMed). Second, we were not able to capture all articles published because of the delay caused by the indexing. Also, because our retrieval period was only through November 2020, articles published or posted after this date, of which there have been many, were not included. Further, our study was limited to articles published in English only, which may have resulted in publication bias.

In conclusion, this study adds to our understanding of the immune responses that are associated with ARDS in COVID-19. It is clear that there is considerable heterogeneity with individual biomarkers in ARDS as well as the severity of lung injury due to SARS-CoV-2 infection. This study reinforces the importance of the complex nature of dysregulated cytokine and inflammatory mediator pathways in planning future studies targeting specific molecular pathways. Also, this study assessed the nature of the immune response in COVID-19 patients who have ARDS and identified specific cytokine targets that could be further researched to prevent ARDS. Furthermore, this study includes a comprehensive examination of the literature to assess the state of research and identify research gaps related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, this study findings corroborated with the previous drug clinic trials that demonstrated that though cytokines associated with ARDS can be therapeutically targeted, some treatments proved to be not.

In conclusion, this study adds to our understanding the mechanism in which the immune system responds to COVID-19 infection and the process that leads to ARDS. It is clear that there is considerable heterogeneity with individual biomarkers in ARDS as well as the severity of lung injury. This study reinforces the importance of the complex nature of dysregulated cytokine and inflammatory mediator pathways in planning future studies targeting specific molecular pathways. Additionally, this study adds to our existing knowledge about biomarkers in COVID-19 by underpinning the need to conduct randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trials to truly test the relevance of biomarkers reported in observational and retrospective studies. We highlight that the randomized clinical trials in COVID-19 to date that selectively targeted biomarkers (and biological pathways) of interest proved to be not effective. Finally, this scoping review discuss the effectiveness of targeting multiple the upregulated cytokines among different phases of COVID-19 Patients with ARDS, and further indicated IL-17 and IL-6 therapeutic targets for COVID-19.

Funding

No funding sources.

Disclosure

None declared.

Ethical approval

Not required.

Author contributions

AA, MA, and HA equally did the literature review, data collection, study design, analysis of data, and manuscript preparation and writing. AA, FA, HN, NA, MW, AA did contribute to the literature search, and manuscript preparation and editing.

References

- 1.Ncfh S. CDC; 2020. Weekly updates by select demographic and geographic characteristics. Provisional death counts for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibson P.G., Qin L., Puah S.H. COVID-19 acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS): clinical features and differences from typical pre-COVID-19 ARDS. Med J Aust. 2020;213(2):54–56.e51. doi: 10.5694/mja2.50674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Woolf S.H., Chapman D.A., Sabo R.T., Weinberger D.M., Hill L. Excess deaths from COVID-19 and other causes, March–April 2020. Jama. 2020;324(5):510–513. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.11787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu C., Chen X., Cai Y., Zhou X., Xu S., Huang H., et al. Risk factors associated with acute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):934–943. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fan E., Beitler J.R., Brochard L., Calfee C.S., Ferguson N.D., Slutsky A.S., et al. COVID-19-associated acute respiratory distress syndrome: is a different approach to management warranted? Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(8):816–821. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30304-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ragab D., Salah Eldin H., Taeimah M., Khattab R., Salem R. The COVID-19 cytokine storm; what we know so far. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1446. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Thiel V., Weber F. Interferon and cytokine responses to SARS-coronavirus infection. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2008;19(2):121–132. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2008.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu W., Yen Y.T., Singh S., Kao C.L., Wu-Hsieh B.A. SARS-CoV regulates immune function-related gene expression in human monocytic cells. Viral Immunol. 2012;25(4):277–288. doi: 10.1089/vim.2011.0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang C., Wang Y., Li X., Ren L., Zhao J., Hu Y., et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Le Bon A., Tough D.F. Links between innate and adaptive immunity via type I interferon. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14(4):432–436. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(02)00354-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Z., Guo X., Hao W., Wu Y., Ji Y., Zhao Y., et al. The relationship between serum interleukins and T-lymphocyte subsets in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Chin Med J (Engl) 2003;116(7):981–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daily Updates of Totals by Week and State . CDC; 2020. Provisional death counts for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arksey H., O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dreher M., Kersten A., Bickenbach J., Balfanz B.P., Hartmann B., Cornelissen C., et al. The characteristics of 50 hospitalized COVID-19 patients with and without ARDS. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2020;117(16):271–278. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2020.0271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hu B., Huang S., Yin L. The cytokine storm and COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1002/jmv.26232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu F., Li L., Xu M., Wu J., Luo D., Zhu Y., et al. Prognostic value of interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin in patients with COVID-19. J Clin Virol. 2020;127 doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen G., Wu D., Guo W., Cao Y., Huang D., Wang H., et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020;130(5):2620–2629. doi: 10.1172/JCI137244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hou H., Zhang B., Huang H., Luo Y., Wu S., Tang G., et al. Using IL-2R/lymphocytes for predicting the clinical progression of patients with COVID-19. Clin Exp Immunol. 2020;201(1):76–84. doi: 10.1111/cei.13450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wan S., Yi Q., Fan S., Lv J., Zhang X., Guo L., et al. Relationships among lymphocyte subsets, cytokines, and the pulmonary inflammation index in coronavirus (COVID-19) infected patients. Br J Haematol. 2020;189(3):428–437. doi: 10.1111/bjh.16659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zheng Y., Sun L.J., Xu M., Pan J., Zhang Y.T., Fang X.L., et al. Clinical characteristics of 34 COVID-19 patients admitted to intensive care unit in Hangzhou, China. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2020;21(5):378–387. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B2000174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matthay M.A., Zemans R.L. The acute respiratory distress syndrome: pathogenesis and treatment. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:147–163. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fara A., Mitrev Z., Rosalia R.A., Assas B.M. Cytokine storm and COVID-19: a chronicle of pro-inflammatory cytokines. Open Biol. 2020;10(9) doi: 10.1098/rsob.200160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sarzi-Puttini P., Giorgi V., Sirotti S., Marotto D., Ardizzone S., Rizzardini G., et al. COVID-19, cytokines and immunosuppression: what can we learn from severe acute respiratory syndrome? Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2020;38(2):337–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tang Y., Liu J., Zhang D., Xu Z., Ji J., Wen C. Cytokine Storm in COVID-19: the current evidence and treatment strategies. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1708. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shah V.K., Firmal P., Alam A., Ganguly D., Chattopadhyay S. Overview of immune response during SARS-CoV-2 infection: lessons from the past. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1949. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stone J.H., Frigault M.J., Serling-Boyd N.J., Fernandes A.D., Harvey L., Foulkes A.S., et al. Efficacy of tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(24):2333–2344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Y., Zhou F., Zhang D., Zhao J., Du R., Hu Y., et al. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of intravenous remdesivir in adult patients with severe COVID-19: study protocol for a phase 3 randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial. Trials. 2020;21(1):422. doi: 10.1186/s13063-020-04352-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soin A.S., Kumar K., Choudhary N.S., Mehta Y., Kataria S., Govil D., et al. Tocilizumab plus standard care versus standard care in patients in India with moderate to severe COVID-19-associated cytokine release syndrome (COVINTOC): an open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00081-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lundh A. Tocilizumab in patients hospitalized with Covid-19 pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021 doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2100217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salama C., Han J., Yau L., Reiss W.G., Kramer B., Neidhart J.D., et al. Tocilizumab in Patients hospitalized with covid-19 pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(1):20–30. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2030340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lescure F.X., Honda H., Fowler R.A., Lazar J.S., Shi G., Wung P., et al. Sarilumab in patients admitted to hospital with severe or critical COVID-19: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00099-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fisher C.J., Jr., Agosti J.M., Opal S.M., Lowry S.F., Balk R.A., Sadoff J.C., et al. Treatment of septic shock with the tumor necrosis factor receptor:Fc fusion protein. The Soluble TNF Receptor Sepsis Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(26):1697–1702. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606273342603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abbas A.K., Trotta E., D R.S., Marson A., Bluestone J.A. Revisiting IL-2: biology and therapeutic prospects. Sci Immunol. 2018;3(25) doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aat1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zenobia C., Hajishengallis G. Basic biology and role of interleukin-17 in immunity and inflammation. Periodontol 2000. 2015;69(1):142–159. doi: 10.1111/prd.12083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pacha O., Sallman M.A., Evans S.E. COVID-19: a case for inhibiting IL-17? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(6):345–346. doi: 10.1038/s41577-020-0328-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reich K., Blauvelt A., Armstrong A., Langley R.G., Fox T., Huang H.J., et al. Secukinumab, a fully human anti-interleukin-17A monoclonal antibody, exhibits minimal immunogenicity in patients with moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176(3):752–758. doi: 10.1111/bjd.14965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakagome K., Nagata M. Involvement and possible role of eosinophils in asthma exacerbation. Front Immunol. 2018;9:2220. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]