Abstract

Tillandsia is a genus belonging to the Bromeliaceae family, most of which are epiphytes. The flowers of some of the Tillandsia species are very fragrant, but the volatile composition has been scarcely reported. In this report, we studied the chemical composition of volatile compounds emitted by the flowers of Tillandsia xiphioides using the HS-SPME/GC-MS method. The extraction conditions (fiber, temperature, and time) were optimized using a multivariate approach, and the composition of the extracted volatiles was determined by gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS). In total, 30 extracted compounds were identified. Two extraction methods are necessary for the efficient extraction of the volatile compounds. These results were applied to profile two forms of T. xiphioides.

Introduction

Tillandsia is one of the 57 plant genera belonging to the Bromeliaceae family.1−3 Due to their characteristic appearance, Bromeliads are very important horticultural plants.4 Indeed, the Bromeliaceae is a well-known family of monocotyledons considered endemic to the Neotropics.5 It is divided into eight subfamilies.3,6,7 Considered to be the most diverse genus, Tillandsia comprises more than 700 species, of which the main ones are epiphytes.2,8,9Tillandsia genus has shown some potentialities in pharmacy as a medicinal plant.10

Regarding volatile compounds, the aromatic profile of the Tillandsia genus is described very little. Two species have been studied: Tillandsia macropetala and Tillandsia crocata. It is worth noting that T. macropetala has been moved to Pseudalcantarea genus from 2016.11 In 2014, nine volatile compounds (three fatty acid derivatives and six terpenoids) were identified inT. macropetala by Aguilar-Rodriguez et al.8 The extraction of the volatile compounds was carried out using the dynamic pull headspace method and analysis using gas chromatography with mass selective detection (GC-MSD). The presence of the compounds was correlated with pollination by bats.

In 1991, the extraction of volatile compounds in T. crocata was performed in headspace with adsorbent cartridges, and the analysis was done by gas chromatography coupled with a flame ionization detector (GC-FID) and gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (GC-MS). This allowed for the identification of seven volatile molecules.12 Pollination of T. crocata would be carried out by the Euglossine bees because of its very intense smell. Fragrances and their composition are very important in attracting pollinators playing a role in the reproductive cycle of flowering plants. Volatile compounds emitted by flowers are generally terpenoids, benzenoids, and phenylpropanoids.13 These compounds come from different biosynthesis pathways, their synergy leading to the floral fragrance.

Extraction is a very important step when studying the composition of floral volatiles of a plant. For this purpose, the methods frequently used are steam distillation, solvent extraction, and headspace trapping.14 In addition to being time-consuming, the first two techniques require the use of large quantities of solvents and can cause thermal artifacts.15 Therefore, headspace trapping methods such as headspace solid phase microextraction (HS-SPME) are increasingly used. Indeed, it is a technique that has several advantages, including the reduction of extraction time, the absence of the use of organic solvents, the possibility of automation, the facility of coupling with gas chromatography (GC), simplicity, sensitivity, and selectivity.16,17 It is a technique that was introduced in 1990 by Arthur and Pawliszyn18 to analyze pollutants in water. Since then, its field of application has developed enormously, particularly in the analysis of the odorous components of many flowers and other plant materials.19 The SPME is based on the ab/adsorption of the compounds on a fiber, coated with a polymer, also known as the extraction phase. Several polymers of different polarities are currently available, and desorption of compounds is generally achieved by a thermal method in GC. Indeed, polar compounds are sorbed on polar fibers and nonpolar compounds on nonpolar fibers. However, it is impossible to perform repeated injections when the whole sample is desorbed in the injector.20 For extraction, the fiber can be directly immersed in the liquid, in the presence of a liquid sample; in this case, it is called direct immersion (DI-SPME) or it can be exposed to the vapor phase in the presence of a solid, liquid, or gaseous sample, in which case it is called headspace SPME (HS-SPME).21 Apart from the nature of the fiber, several other parameters can affect the SPME method such as extraction temperature and duration, equilibration time, desorption time, and agitation.

As many factors influence system response, optimization can be performed using a multivariate approach. Indeed, whereas in univariate procedures each factor is studied separately and requires a large number of experiments, simultaneous multivariate approaches such as experimental designs allow to vary simultaneously all the factors studied in a predefined number of experiments and to highlight the interactions existing between them, which are not detectable with classical experimental methods.22

The aim of this work is to apprehend more deeply the diversity of the chemical composition of volatile compounds emitted by the flowers of Tillandsia species acclimatized in the Occitanie region (south of France), such as Tillandsia xiphioides. This species is known to present a strong and pleasant flower fragrance,23 but the composition has never been studied. T. xiphioides Ker Gawler is native to South America (Bolivia, Paraguay, Brazil, Uruguay, and Argentina) and allows for large variations differing from plant size, succulence, leaf arrangement, and pubescence.2,6,23,24

This study will enable us to describe for the first time the volatile compounds emitted by flowers of T. xiphioides. To achieve this, the HS-SPME/GC-MS method was used for the extraction and analysis of the volatile compounds. After selecting the type of fiber, a face-centered central composite design (FCCD) was carried out in order to study the influence of the main factors affecting the extraction of compounds. The selected method was applied to two forms of T. xiphioides, and chemometrics was used to verify if there was a difference between the volatile composition of the flowers of both forms of T. xiphioides.

Results and Discussion

Selection of the SPME Fiber

Three different fibers were tested in order to select the one that will allow for the maximum extraction of volatile compounds. For this, two flowers of T. xiphioides were used and, for each flower of Tillandsia, the extraction was carried out by using the three fibers successively.

The results obtained are shown in Figure S3. For the first method, the extraction was performed at 30 °C for a period of 20 min, and we obtain 18 compounds for the PDMS/DVB fiber, 21 compounds for the DVB/CAR/PDMS fiber, and 29 compounds for the CAR/PDMS fiber. For the second method, the extraction was performed at 45 °C for a period of 20 min, 18 compounds were extracted by the PDMS/DVB fiber, 18 compounds were also extracted by the DVB/CAR/PDMS fiber, and 29 compounds for the CAR/PDMS fiber.

The results of this screening showed that, in general, the extraction efficiency was better for the CAR/PDMS fiber. The CAR/PDMS fiber proved to be the most suitable for our study due to its broad specificity and sensitivity. Earlier studies of aromatic plants have already showed that a biphase fiber coating of polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) and carboxen (CAR) was the most effective for detection of plant volatiles.25,26 Therefore, CAR/PDMS was selected for the method optimization.

Identification

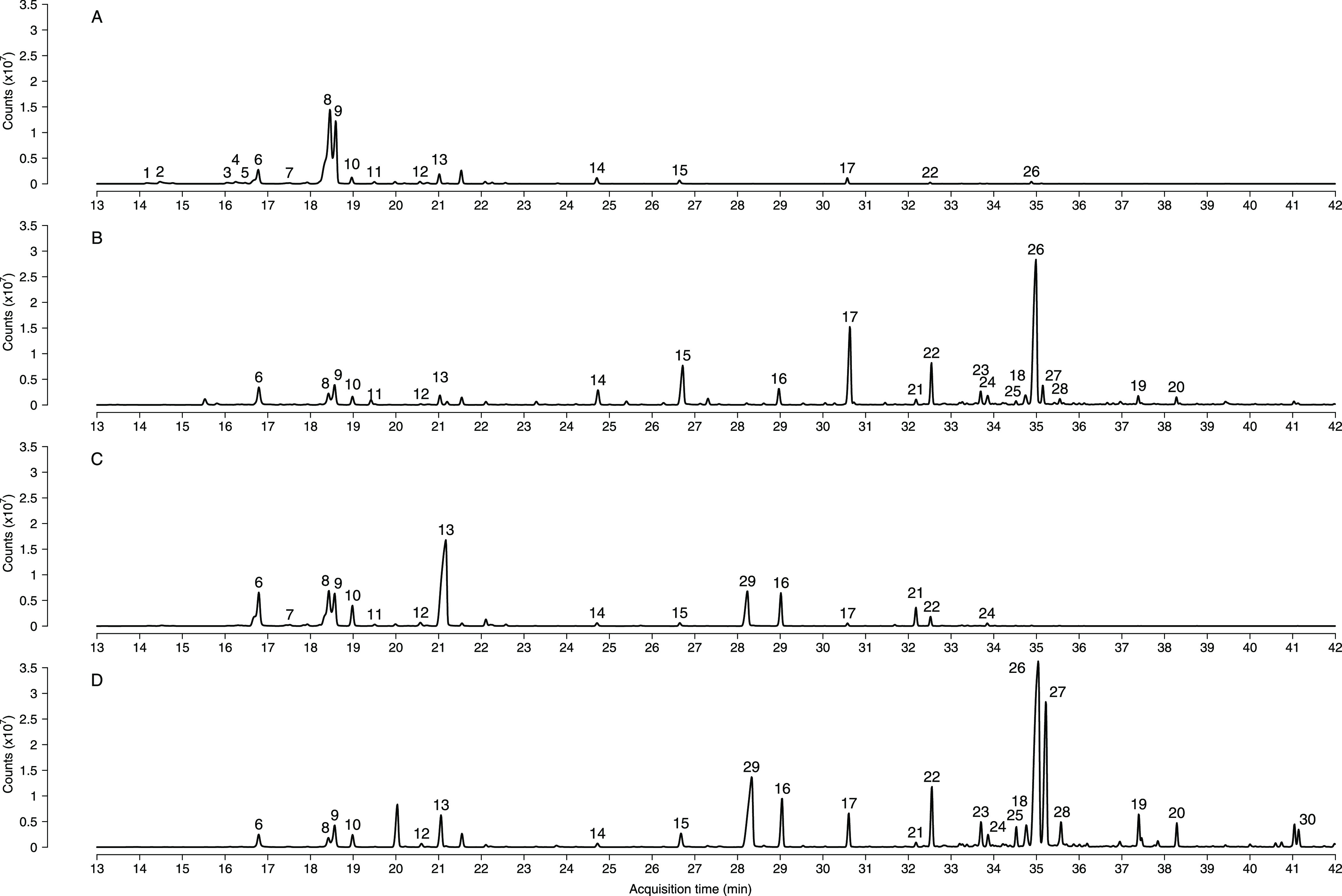

As shown in Table 1, a total of 30 volatile compounds extracted using CAR/PDMS coating fiber were identified for the first time from floral emissions of T. xiphioides (Figure 1). These included 20 monoterpenes, 8 sesquiterpenes, and 2 others compounds (1 nitrogen compound and 1 ester).

Table 1. Identification of Volatile Compounds Emitted by the Flowers of T. xiphioides.

| # | family | compound | RIa | m/z | retention time (min) | identificationb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | monoterpene | α-thujene* | 919.04 | 136.1 | 14.15 | MS + RI |

| 2 | monoterpene | α-pinene* | 927.24 | 136.1 | 14.46 | MS, RI and STD |

| 3 | monoterpene | sabinene* | 969.04 | 136.1 | 16.05 | MS, RI and STD |

| 4 | monoterpene | β-phellandrene* | 973.81 | 136.1 | 16.23 | MS + RI |

| 5 | monoterpene | β-pinene* | 979.87 | 136.1 | 16.46 | MS, RI and STD |

| 6 | monoterpene | β-myrcene* | 988.09 | 136.1 | 16.78 | MS, RI and STD |

| 7 | monoterpene | α-phellandrene* | 1007.47 | 136.1 | 17.51 | MS + RI |

| 8 | monoterpene | limonene* | 1033.5 | 136.1 | 18.52 | MS, RI and STD |

| 9 | monoterpene | eucalyptol* | 1036.85 | 154.1 | 18.66 | MS, RI and STD |

| 10 | monoterpene | β-ocimene* | 1045.1 | 136.1 | 18.98 | MS, RI and STD |

| 11 | monoterpene | γ-terpinene* | 1058.76 | 136.1 | 19.5 | MS, RI and STD |

| 12 | monoterpene | terpinolene* | 1086.34 | 136.1 | 20.57 | MS + RI |

| 13 | monoterpene | β-linalool* | 1097.68 | 154.1 | 21.02 | MS, RI and STD |

| 14 | monoterpene | α-terpineol* | 1196.01 | 154.1 | 24.71 | MS, RI and STD |

| 15 | monoterpene | geraniol* | 1249.72 | 154.1 | 26.64 | MS, RI and STD |

| 16 | monoterpene | methyl geranate+ | 1320.56 | 182.1 | 29.02 | MS + RI |

| 17 | monoterpene | geranyl acetate+ | 1378.72 | 196.1 | 30.59 | MS, RI and STD |

| 18 | monoterpene | geranyl butyrate+ | 1556.43 | 224 | 34.75 | MS + RI |

| 19 | monoterpene | geranyl tiglate+ | 1695.1 | 236 | 37.39 | MS + RI |

| 20 | monoterpene | geranyl hexanoate+ | 1748.19 | 252 | 38.27 | MS + RI |

| 21 | sesquiterpene | α-bergamotene+ | 1439.14 | 204.2 | 32.16 | MS + RI |

| 22 | sesquiterpene | β-farnesene+ | 1454.04 | 204.2 | 32.55 | MS + RI |

| 23 | sesquiterpene | α-farnesene+ | 1503.96 | 204.2 | 33.69 | MS + RI |

| 24 | sesquiterpene | β-bisabolene+ | 1512.37 | 204.2 | 33.86 | MS + RI |

| 25 | sesquiterpene | α-bisabolene+ | 1544.55 | 204.2 | 34.52 | MS + RI |

| 26 | sesquiterpene | nerolidol+ | 1567.82 | 222.2 | 34.98 | MS, RI and STD |

| 27 | sesquiterpene | denderalasin+ | 1577.22 | 218.2 | 35.17 | MS + RI |

| 28 | sesquiterpene | α-patchoulene+ | 1595.54 | 204.2 | 35.55 | MS + RI |

| 29 | other | indole+ | 1296.08 | 117.1 | 28.22 | MS + RI |

| 30 | other | methyl palmitate+ | 268.2 | 41.14 | MS |

Retention Index using a DB-5MS capillary column.

MS = by comparison of the mass spectrum with the NIST library. RI = by comparison of RI (retention index) with RI of published literatures and online library (https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/cas-ser.html). STD = by comparison of retention time and mass spectrum of the authentic standard. * = efficient extraction with the first method, low values of temperature and extraction time (30 °C and 20 min). + = efficient extraction with the second method, high values of temperature and extraction time (75 °C and 65 min).

Figure 1.

Chromatographic separation was carried out on a DB-5MS column. (A) TIC of LP-xiphi, the extraction being performed by CAR/PDMS for 20 min at an extraction temperature of 30 °C. (B) TIC of LP-xiphi, the extraction being performed by CAR/PDMS for 60 min at an extraction temperature of 75 °C. (C) TIC of HP-xiphi, the extraction being carried out by CAR/PDMS for 20 min at an extraction temperature of 30 °C. (D) TIC of HP-xiphi, the extraction being carried out by CAR/PDMS for 60 min at an extraction temperature of 75 °C. For complete chromatograms, see Figure S4 in the Supporting Information. The identification numbers correspond to those shown in Table 1.

Terpenoids

Terpenes are a group of natural products that are widely represented in the plant kingdom, with currently more than 40,000 terpenoids reported in natural products.27 The best-known biosynthetic pathway is that of mevalonic acid, although there is another independent pathway, that is, the pathway of 2-C-methyl-D-erythritol phosphate. Both pathways lead to the synthesis of isopentenyl pyrophosphate and dimethyl allyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP), which are fundamental precursors of terpenoids. From these, the action of different prenyltransferases is generated to produce by condensation the following prenylpyrophosphates: geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP), which is the precursor of monoterpenes, farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP), which is the precursor of sesquiterpenes and triterpenes, and geranyl pyrophosphate, which is the precursor of diterpenes and tetraterpenes.28,29

Monoterpenes

Monoterpenes are widely present in essential oils. Because of their natural and pleasant aroma, they find extensive use in food and fragrance industry and are used in aromatherapy. They are biologically active with antibacterial, antiseptic, and antioxidant properties, among others.30−32 In this study, 20 monoterpenes were identified in the flowers of T. xiphioides, including acyclic, monocyclic, bicyclic, and oxygenated monoterpenes.

For acyclic monoterpenes, their aroma thresholds tend to be lower than those of cyclic monoterpenes of the same molecular weight. In this study, β-myrcene (6) and β-ocimene (10) are the only linear monoterpenes identified in T. xiphioides flowers. β-Ocimene has already been identified in T. macropetala (5.6%)8 and T. crocata (48%).12

The monocyclic monoterpenes identified in this study are α-phellandrene (7), β-phellandrene (4), limonene (8), and γ-terpinene (11). Limonene is widely used as a flavoring agent in food and beverages because it has a pleasant lemon scent and is one of the most common and cheapest flavors used in cosmetic formulations.33 Limonene was found to be the major monocyclic monoterpene and has already been identified in T. macropetala (24,2%)8 and T. crocata (3%).12

Alpha-thujene (1), α-pinene (2), β-pinene (5), and sabinene (3) are the bicyclic monoterpenes identified in this study. They are present in small amounts and are chemically unstable due to a tight ring system. β-Pinene has already been identified in T. macropetala (8.3%).8

Oxygenated terpenes consist mainly of alcoholic terpenes and terpene esters and ethers. Eucalyptol (9) and linalool (13) are the main compounds in this group. Eucalyptol, also known as 1,8-cineol, has already been identified in T. crocata (16%).12 Eucalyptol is present in the essential oils of Eucalyptus and is used in the treatment of respiratory diseases.34 Other oxygenated monoterpenes such as terpinolene (12), α-terpineol (14), geraniol (15), methyl geranate (16), geranyl acetate (17), geranyl butyrate (18), geranyl tiglate (19), and geranyl hexanoate (20) have been identified in the flowers of T. xiphioides. Geraniol (11.5%) and methyl geranate (11%) were also identified in T. macropetala.8

Sesquiterpenes

Sesquiterpenes are compounds with 15 carbon atoms that can be linear, acyclic, bicyclic, or tricyclic. In this study, 8 sesquiterpenes were identified: α-bergamotene (21), β-farnesene (22), α-farnesene (23), β-bisabolene (24), α-bisabolene (25), nerolidol (26), denderalisin (27), and α-patchoulene (28). Nerolidol and denderalisin are the majority of this group of compounds. Nerolidol is a fragrance ingredient used in many cosmetic products, but also in detergents and household cleaners. Its use worldwide is in the order of 10 to 100 tons per year.35

Others Compounds

Two other compounds have also been identified from the flowers of T. xiphioides, which are indole (29) and methyl palmitate (30). Methyl palmitate belongs to the class of fatty acid methyl ester organic compounds. Indole is an aromatic heterocyclic organic compound, which is produced in plants by the shikimate pathway. It is involved in several plant functions such as tryptophan production, yellow petal coloration (terpenoidindole alkaloid), and biosynthesis of defense and perfume metabolites.36

Optimization of the Method

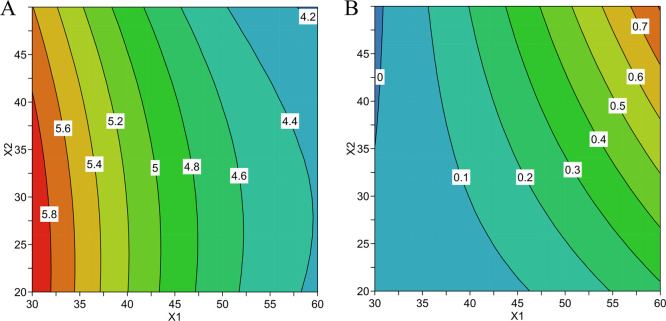

The results of the second-order polynomial model fitting showed a statistically significant influence of the extraction temperature (X1) and extraction time (X2) on the sum of the total peak areas and the peak area values of the 30 selected volatile compounds in contrast to the equilibrium and desorption times which were not statistically significant. However, with the realization of this first experimental design, a negative effect of temperature was observed on low molecular weight compounds such as eucalyptol (Figure 2A) and a positive effect of temperature on higher molecular weight compounds such as nerolidol (Figure 2B). The effect of extraction temperature was therefore evaluated by performing a second experimental design.

Figure 2.

Response Contour Plot showing the effect of temperature and extraction time on the extraction of (A) eucalyptol (R2 > 0.65) and of (B) nerolidol (R2 > 0.90).

A reduced central composite design was therefore performed with temperature and time of extraction as factors, with higher bounds for extraction temperature. The equilibrium and desorption times do not significantly affect the efficiency of SPME extraction, and for this reason, the values associated with these two parameters were set, in accordance with the ranges previously selected in Table S1, to 7.5 and 4 min, respectively. Optimal values for temperature and extraction time were evaluated on the peak area values of 30 selected volatile compounds on the total ion chromatogram. In general, it was observed on the response contour plot that the optimal conditions of temperature and extraction are affected by the volatility of the analyte. Indeed, the extraction efficiency of highly volatile compounds is negatively influenced by temperature and extraction time, while the opposite is observed for less volatile compounds. The results obtained with the first design of experiments are confirmed by the second design: the use of higher temperatures can enrich the volatile extract with less volatile metabolites, but at the same time, it can lead to a loss of more thermolabile metabolites. Martendal et al.37 also showed that the optimal temperature differs significantly for various volatile compounds; any compromise condition for extracting analytes from a certain group affects the extraction efficiency of the other groups. Indeed, when there is an increase in extraction temperature, two opposite phenomena occur: an increase in the rate of analyte transfer to the fiber and a decrease in the distribution constant of the analyte between the headspace and the fiber coating, and depending on the predominant phenomenon, a significant decrease in the sensitivity of the method could occur.

Based on these results, the use of two extraction methods is necessary to ensure that all analytes are extracted with good efficiency. A first method with low temperature and extraction time values (30 °C and 20 min) was therefore selected for the extraction of the first 15 molecules given in Table 1 (α-thujene to geraniol), and a second method with higher temperature and extraction time values (75 °C and 65 min) was used to extract the last 15 molecules given in Table 1 (methyl geranate to methyl palmitate). The methods selected will allow for a better understanding of the complexity of the composition of the floral perfume of T. xiphioides.

Application of the Method: Profiling with Both Forms of T. xiphioides

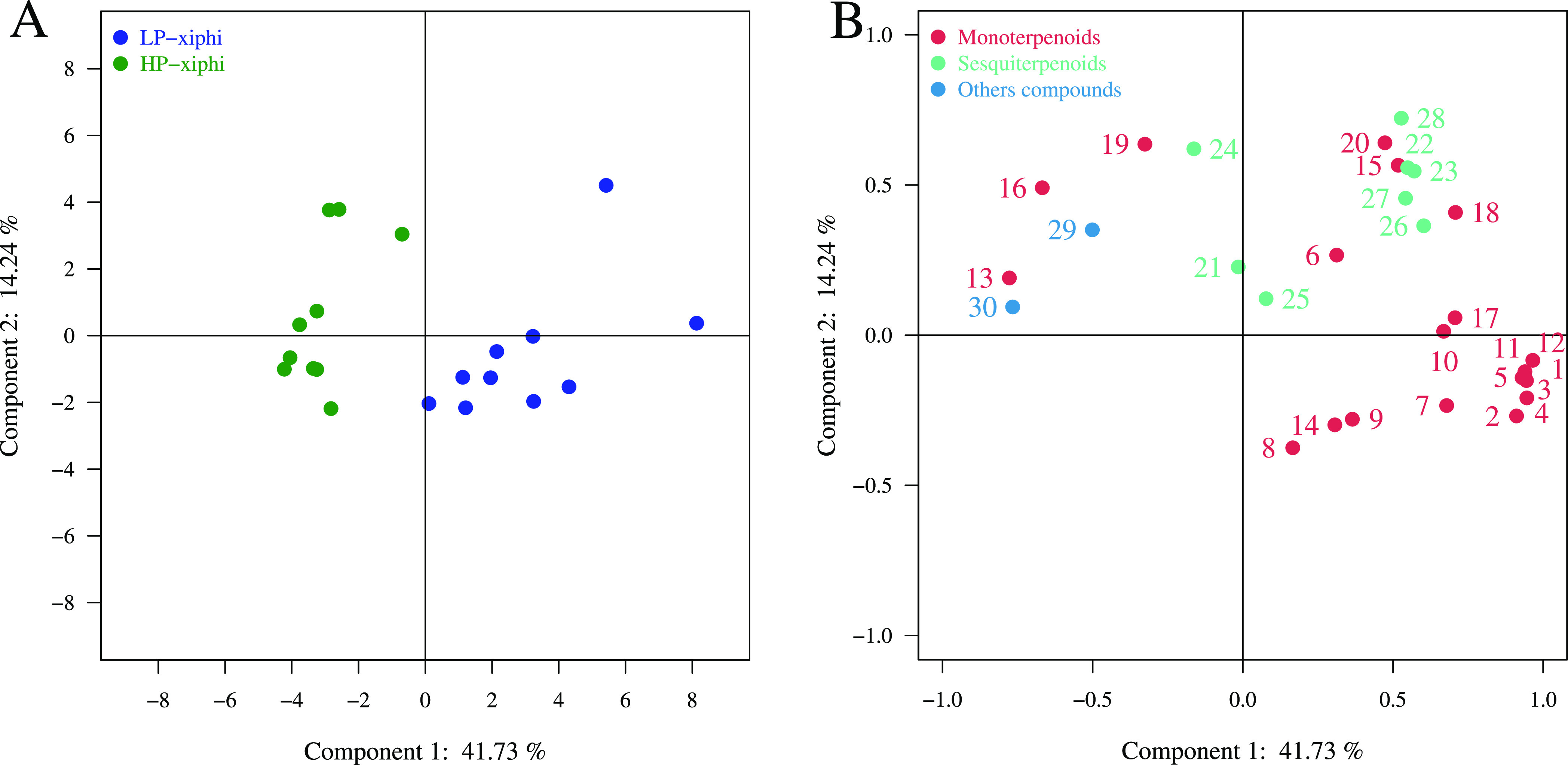

The selected methods were applied to two forms of T. xiphioides noted LP-xiphi and HP-xiphi. Principal component analysis (PCA) statistical processing was then performed to study the main sources of variability between both forms. PCA allows to synthesize the information contained in a data table, to identify possible similarities between individuals, and to visualize the main sources of variance.

PCA analysis led to the extraction of two principal components (PCs) that contributed to 41.73% of the total variance in the data set when volatile compounds from flowers have been used to characterize each plant form. We can see in Figure 3A that the plants of the LP-xiphi form are clearly separated from those of the HP-xiphi form all along the ordinate axis. Indeed, the flowers of LP-xiphi are on the right due to the different intensities of monoterpenoids and sesquiterpenoids with higher intensities of eucalyptol, limonene, and also monoterpene hydrocarbons such as α-thujene, α-pinene, β-pinene, β-phellandrene, β-myrcene, α-phellandrene, and γ-terpinene. All these compounds contribute well to the overall odor of LP-xiphi. Indeed, limonene and eucalyptol bring fresh citrus and mint notes, while the monoterpenes hydrocarbons have a spicy smell of wood and resin. On the other hand, flowers of HP-xiphi are grouped on the left because of the higher intensities of β-linalool, indole, methyl palmitate, methyl geranate, and geranyl tiglate (Figure 3B). Beta-linalool and esters provide that fruity, floral note, while indole has a mothball smell. Indole and methyl palmitate are marker compounds for HP-xiphi because they are not present in the other form of T. xiphioides. The volatile compounds located between the two forms of T. xiphioides show that their characteristics are an intermediate between the forms.

Figure 3.

PCA of LP-xiphi and HP-xiphi flowers, based on GC-MS data: (A) Score plot of PC1 versus PC2 scores. (B) Loading plot of PC1 and PC2 contributing volatile compounds.

Conclusions

The HS-SPME/GC-MS method has shown to be effective in extracting and identifying a total of 30 volatile compounds emitted by the flowers of T. xiphioides. It was determined that a two-phase SPME fiber, the CAR/PDMS fiber, was most suitable for the extraction of a larger amount of compounds. Two experimental designs were carried out to determine the factors that could influence the HS-SPME method as well as the optimal values of these factors to achieve a more efficient extraction. It was thus demonstrated that extraction temperature and extraction time were the most influential factors with a negative effect of temperature on the extraction of low molecular weight compounds and a positive effect of temperature on higher molecular weight compounds. This led to the use of two extraction methods in order to understand the complexity of the composition of volatile compounds emitted by the flowers of T. xiphioides. The selected methods were applied to two forms of T. xiphioides which presented, after the principal components analysis, a variation in the intensities of certain volatile compounds which could lead to a difference in their floral odor. Actually, a slight difference in fragrance has been observed by our partner and plant supplier Tillandsia PROD plant nursery.

Experimental Section

Plant Material and Chemicals

All the flowers of T. xiphioides studied in this report come from the Tillandsia PROD plant nursery located in the commune of Le Cailar (Occitania, France). The plant nursery includes about 500,000 Tillandsia, of 350 species, varieties, forms, and hybrids. T. xiphioides is known to present many ecotypes differing on pubescence from lepidote mentose with dense wolly hairs, among other characteristics.23 For the PCA, two forms of T. xiphioides called in this paper Low-Pubescent T. xiphioides (LP-xiphi) and High-Pubescent T. xiphioides (HP-xiphi) according to, respectively, weak and strong morphological development of trichomes on the leaves, were used (see Figures S1 and S2 in Supporting Information). A total of 10 plants of each form providing 2–3 flowers each were harvested from February to May 2020.

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, USA): α-pinene (98.5% purity), sabinene (75%), β-pinene (98.5%), β-myrcene (90%), limonene (99%), eucalyptol (99%), β-ocimene (95.4%), γ-terpinene (98.5%), β-linalool (97%), α-terpineol (90%), geraniol (99%), geranyl acetate (99%), and nerolidol (98.5%). All have an analytical standard grade except for sabinene.

Selection of the SPME Fiber

Three different polymer-grafted SPME fibers were tested: divinylbenzene/polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS/DVB) 65 μm fiber, carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane (CAR/PDMS) 75 μm fiber, and divinylbenzene/carboxen/polydimethylsiloxane (DVB/CAR/PDMS) 50/30 μm Stableflex fiber. The SPME device and all fibers were purchased from Supelco (Bellefonte, PA, USA). Prior to use, the fibers were conditioned according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. All extractions were performed by inserting a flower into a 20 mL amber vial sealed with a PTFE-lined septum cap (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA).

For the choice of the nature of the polymer, two flowers of T. xiphioides were used and, for each Tillandsia flower, the extraction was carried out using the three fibers successively according to two methods: the first for an extraction time of 20 min with an extraction temperature of 30 °C and the second for an extraction time of 20 min with a temperature of 45 °C.

Optimization of the HS-SPME Extraction

Once the nature of the polymer was chosen, the optimization of the extraction method was achieved using two experimental designs: a first response surface design in order to know the most significant factors and a second response surface design in order to find the optimal conditions for the selected factors. Information about the levels and factors of the experimental designs is presented in the Supporting Information (Tables S1, S2, and S3).

As an initial step, a four-factor and three-level face-centered composite central design (FCCD) was performed (Table S1) with five replicates in the center of the design. This method is used because it will provide us secure information concerning the best conditions of analysis, the existence or absence of experimental errors, as well as any interaction that may exist between the factors involved. The factors chosen are extraction temperature, extraction time, equilibrium time, and desorption time. A field of study was previously defined from the literature in order to establish the bounds of the studied parameters. The FCCD was used to evaluate the significance of the variables and the interactions among them for reducing the number of experiments. In total, N = 30 experiments were performed on the same sample in a randomized manner. In addition, an empty vial used as a control was analyzed throughout the analysis sequence. The sum of the total peak areas and the peak area values of the 30 selected volatile compounds were used as response generating second order equations of type: Y = a0 +a1X1 + a2X2 +a3X3 + a4X4 +a11X12 + a22 X22 + a33X32 + a44X42 + a12X1X2 + a13X1X3 + a14X1X4 + a23X2X3 + a24X2X4 + a34X3X4. Each response (Y) was assessed as a function of main, quadratic and interaction effects of the extraction temperature (X1), extraction time (X2), equilibrium time (X3), and desorption time (X4).

Once the significant variables influencing the extraction method were determined, an additional experiment based on a reduced composite central design was performed considering only temperature and extraction time as factors (Table S2) and with higher bounding values for extraction temperature. In total, N = 14 experiments with 5 repetitions of the central point were performed on the same sample in a randomized manner. The peak area values of the 30 selected volatile compounds representing 95% of the chromatogram peaks were used as response.

Instrumentation and GC-MS Conditions

The analysis was performed on an Agilent 7890 B gas chromatograph coupled to an Agilent 5977 A mass spectrometer with an MPS autosampler, a thermal desorption unit (TDU), and a cooled injection system (CIS) (Gerstel). MSD Chemstation F.01.00 data acquisition software (Agilent) was used to program the GC-MS. After extraction, desorption is done thermally in the TDU according to the recommended temperatures for each fiber (270 °C for PDMS/DVB and 300 °C for CAR/PDMS and DVB/CAR/PDMS). After desorption, the injection is performed in split mode and the analytes were focused on the CIS at −10 °C for 2 min and then brought to 250 °C at a heating rate of 12 °C per second and maintained for 2.5 min. A DB-5MS apolar capillary column (30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, Agilent) was used, and the separation conditions were as follows: initial column temperature of 40 °C for 2 min; it was then increased by 4 °C/min to 130 °C for 1 min and then increased by 7 °C/min to 230 °C, where it was maintained for 4 min. High pure helium (99.999%) was used as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.2 mL per minute. The temperature of the transfer line has been set at 250 °C and the temperature of the ion source at 230 °C. The ions were generated by a 70 eV electron beam. The mass was scanned in the range from m/z 33 to 500 Da.

Profiling Methods

After the optimization of the HS-SPME extraction method, optimal values were obtained for the studied parameters, which are detailed in the Profiling methods section in the Supporting Information.

Data Processing and Statistical Analysis

All majority peaks, being above the analytical noise and representing 95% of the chromatogram peaks, were integrated using MassHunter Qualitative Analysis B.06.00 software (Agilent Technologies). This software allows for the deconvolution of the chromatograms by separating the co-eluted compounds. The identification of the volatile compounds was performed by comparing the retention indices (RI) relative to n-alkanes (C8–C20), run under identical conditions for GC-MS, with those of the compounds in the National Institute of Standard and Technologies (NIST) online library (https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/cas-ser.html), by comparing the mass spectra of the compounds with those of the compounds referenced in the NIST and Wiley7 databases (R > 800) and also by comparing the retention times and mass spectra of the compounds with those of the available standards (mentioned above). For the standard solution, 0.2 μL of each standard was added in 2 mL of hexane, and the solvent was subsequently evaporated with nitrogen. The analysis was performed under the same conditions as for the flowers.

For statistical analysis, peak area values of the total ion chromatograms were measured with MassHunter and transferred to Excel (Microsoft Excel 2013). The experimental designs (RSM: response surface methodology) were set up to evaluate the respective impact of factors using MODDE software (V12.1, Umetrics, Umea, Sweden). The data obtained after analysis of the flowers of both forms of T. xiphioides were subjected to PCA using SIMCA-P software (V 15.15, Umetrics, Umea, Sweden).

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by LA REGION OCCITANIE and UNIV. NIMES. We also gratefully acknowledge Tillandsia PROD (28 chemin du Cailar 30740 Le Cailar, France) plant nursery (Pierre Kerrand, Daniel Thomin, and Julien Vigo) for providing us the Tillandsia plants used in this study, for the picture of T. xiphioides for graphical abstract (Photograph courtesy of Daniel Thomin (Tillandsia PROD) and arranged by R.M.), for helpful discussions and for their interest in the project.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c00917.

Pictures of the plant material (taken by Mame-Marietou Lo); optimization of the HS-SPME extraction; selection of the SPME fiber; profiling methods; identification of the volatile compounds and complete chromatograms (PDF) (PDF)

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Estrella-parra E.; Flores-cruz M.; Blancas-flores G. The Tillandsia Genus: History, Uses, Chemistry, and Biological Activity. Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plant. Med. Aromat. 2019, 18, 239–264. [Google Scholar]

- Gouda E. J.Tillandsia BROMELIACEAE. In Monocotyledons; Eggli U., Nyffeler R., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2020; pp 1107–1164. [Google Scholar]

- Eggli U.; Gouda E. J.. Bromeliaceae. In Monocotyledons; Eggli U., Nyffeler R., Eds.; Springer Berlin Heidelberg: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2020; pp 835–847. [Google Scholar]

- Barfuss M. H. J.; Samuel R.; Till W.; Stuessy T. F. Phylogenetic Relationships in Subfamily Tillandsioideae (Bromeliaceae) Based on DNA Sequence Data from Seven Plastid Regions. Am. J. Bot. 2005, 92, 337–351. 10.3732/ajb.92.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manetti L. M.; Delaporte R. H.; Laverde A. Jr. Metabólitos secundários da família bromeliaceae. Quím. Nova 2009, 32, 1885–1897. 10.1590/s0100-40422009000700035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roguenant A.; Lecoufle M..; Raynal-Roques A.. Les Broméliacées : Approche Panoramique d’une Grande Famille “américaine”; Editions Belin: Belin: Paris, 2016, pp 62–115. [Google Scholar]

- Givnish T. J.; Barfuss M. H. J.; Van Ee B.; Riina R.; Schulte K.; Horres R.; Gonsiska P. A.; Jabaily R. S.; Crayn D. M.; Smith J. A. C.; Winter K.; Brown G. K.; Evans T. M.; Holst B. K.; Luther H.; Till W.; Zizka G.; Berry P. E.; Sytsma K. J. Phylogeny, Adaptive Radiation, and Historical Biogeography in Bromeliaceae: Insights from an Eight-Locus Plastid Phylogeny. Am. J. Bot. 2011, 98, 872–895. 10.3732/ajb.1000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aguilar-Rodríguez P. A.; MacSwiney G. M. C.; Krömer T.; García-Franco J. G.; Knauer A.; Kessler M. First Record of Bat-Pollination in the Species-Rich Genus Tillandsia (Bromeliaceae). Ann. Bot. 2014, 113, 1047–1055. 10.1093/aob/mcu031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butcher D.; Gouda E.. The New Bromeliad Taxon List; University Botanic Gardens: Utrecht, 2020. Http://Bromeliad.Nl/TaxonList/ (accessed Aug 3, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- Estrella-Parra E.; Flores-Cruz M.; Blancas-Flores G.; Koch S. D.; Alarcón-Aguilar F. J. The Tillandsia Genus: History, Uses, Chemistry, and Biological Activ. Bol. Latinoam. Caribe Plant. Med. Aromat. 2019, 18, 239–264. [Google Scholar]

- Barfuss M. H. J.; Till W.; Leme E. M. C.; Pinzón J. P.; Manzanares J. M.; Halbritter H.; Samuel R.; Brown G. K. Taxonomic Revision of Bromeliaceae Subfam. Tillandsioideae Based on a Multi-Locus DNA Sequence Phylogeny and Morphology. Phytotaxa 2016, 279, 1–97. 10.11646/phytotaxa.279.1.1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gerlach G.; Schill R. Composition of Orchid Scents Attracting Euglossine Bees. Bot. Acta 1991, 104, 379–384. 10.1111/j.1438-8677.1991.tb00245.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stashenko E. E.; Martínez J. R. Sampling Flower Scent for Chromatographic Analysis. J. Sep. Sci. 2008, 31, 2022–2031. 10.1002/jssc.200800151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Báez D.; Pino J. A.; Morales D. Floral Scent Composition inHedychium coronariumJ. Koenig Analyzed by SPME. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2011, 23, 64–67. 10.1080/10412905.2011.9700460. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.-J.; Kim K.; Kim N.-S.; Lee D.-S. Determination of floral fragrances of Rosa hybrida using solid-phase trapping-solvent extraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A 2000, 902, 389–404. 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)00863-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadhosseini M. Chemical Composition of the Volatile Fractions from Flowers, Leaves and Stems ofSalvia mirzayaniiby HS-SPME-GC-MS. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2015, 18, 464–476. 10.1080/0972060x.2014.1001185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adam M.; Juklová M.; Bajer T.; Eisner A.; Ventura K. Comparison of Three Different Solid-Phase Microextraction Fibres for Analysis of Essential Oils in Yacon (Smallanthus Sonchifolius) Leaves. J. Chromatogr. A 2005, 1084, 2–6. 10.1016/j.chroma.2005.05.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur C. L.; Pawliszyn J. Solid Phase Microextraction with Thermal Desorption Using Fused Silica Optical Fibers. Anal. Chem. 1990, 62, 2145–2148. 10.1021/ac00218a019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Almeida V.; Gonçalves V.; Galego L.; Miguel G.; Costa M. Volatile Constituents of Leaves and Flowers of Thymus Mastichina by Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction. Acta Hortic. 2006, 723, 239–242. 10.17660/actahortic.2006.723.30. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tholl D.; Boland W.; Hansel A.; Loreto F.; Röse U. S. R.; Schnitzler J.-P. Practical Approaches to Plant Volatile Analysis. Plant J. 2006, 45, 540–560. 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2005.02612.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejıas R. C.; Marin R. N.; Moreno de V. G.; Barroso C. G. Optimisation of Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction for Analysis of Aromatic Compounds in Vinegar. J. Chromatogr. A 2002, 953, 7–15. 10.1016/s0021-9673(02)00122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dejaegher B.; Vander Heyden Y. Experimental Designs and Their Recent Advances in Set-up, Data Interpretation, and Analytical Applications. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2011, 56, 141–158. 10.1016/j.jpba.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouda E. J. Notes on the Polymorphic Tillandsia Xiphioides Ker Gawler. J. Bromel. Soc. 2015, 65, 111–121. [Google Scholar]

- Roguenant A.Les Tillandsia et les Racinaeaa; Belin: Paris, Belin, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bicchi C.; Drigo S.; Rubiolo P. Influence of Fibre Coating in Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction-Gas Chromatographic Analysis of Aromatic and Medicinal Plants. J. Chromatogr. A 2000, 892, 469–485. 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)00231-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song G.; Xiao J.; Deng C.; Zhang X.; Hu Y. Use of Solid-Phase Microextraction as a Sampling Technique for the Characterization of Volatile Compounds Emitted from Chinese Daffodil Flowers. J. Anal. Chem. 2007, 62, 674–679. 10.1134/s1061934807070118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmann J.; Keeling C. I. Terpenoid Biomaterials. Plant J. 2008, 54, 656–669. 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2008.03449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohlmann J.; Meyer-Gauen G.; Croteau R. Plant Terpenoid Synthases: Molecular Biology and Phylogenetic Analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998, 95, 4126–4133. 10.1073/pnas.95.8.4126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarvey D. J.; Croteau R. Terpenoid Metabolism. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 1015–1026. 10.1105/tpc.7.7.1015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alipour G.; Dashti S.; Hosseinzadeh H. Review of Pharmacological Effects ofMyrtus communisL. and its Active Constituents. Phytother Res. 2014, 28, 1125–1136. 10.1002/ptr.5122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zorzetto C.; Sánchez-Mateo C. C.; Rabanal R. M.; Lupidi G.; Petrelli D.; Vitali L. A.; Bramucci M.; Quassinti L.; Caprioli G.; Papa F.; Ricciutelli M.; Sagratini G.; Vittori S.; Maggi F. Phytochemical Analysis and in Vitro Biological Activity of Three Hypericum Species from the Canary Islands (Hypericum Reflexum, Hypericum Canariense and Hypericum Grandifolium). Fitoterapia 2015, 100, 95–109. 10.1016/j.fitote.2014.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi F.; Fortuné Randriana R.; Rasoanaivo P.; Nicoletti M.; Quassinti L.; Bramucci M.; Lupidi G.; Petrelli D.; Vitali L. A.; Papa F.; Vittori S. Chemical Composition andin vitroBiological Activities of the Essential Oil ofVepris macrophylla(Baker)I.Verd.Endemic to Madagascar. Chem. Biodiversity 2013, 10, 356–366. 10.1002/cbdv.201200253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira A. J.; Beserra F. P.; Souza M. C.; Totti B. M.; Rozza A. L. Limonene: Aroma of Innovation in Health and Disease. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 2018, 283, 97–106. 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhowal M.; Gopal M. Eucalyptol: Safety and Pharmacological Profile. RGUHS J. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 5, 125–131. 10.5530/rjps.2015.4.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chan W.-K.; Tan L.; Chan K.-G.; Lee L.-H.; Goh B.-H. Nerolidol: A Sesquiterpene Alcohol with Multi-Faceted Pharmacological and Biological Activities. Molecules 2016, 21, 529. 10.3390/molecules21050529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cna’ani A.; Seifan M.; Tzin V. Indole Is an Essential Molecule for Plant Interactions with Herbivores and Pollinators. J. Plant Biol. Crop Res. 2018, 1, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Martendal E.; de Souza Silveira C. D.; Nardini G. S.; Carasek E. Use of Different Sample Temperatures in a Single Extraction Procedure for the Screening of the Aroma Profile of Plant Matrices by Headspace Solid-Phase Microextraction. J. Chromatogr. A 2011, 1218, 3731–3736. 10.1016/j.chroma.2011.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.