Abstract

Platycodon grandiflorum is a perennial plant that has been used for medicinal purposes. Specifically, it is widely used in Northern China and Korea for the treatment of various diseases. Terpenoids belong to a group called secondary metabolites and have attracted a wide range of interest. Here, we determined the expressed sequence tag (EST) library of the methyl jasmonate (MeJA)-treated hairy root of P. grandiflorum. In total, 5760 ESTs were obtained, but after deleting the vector sequences and removing poor-quality sequences, a total of 2536 ESTs were attained. Of these, 811 contigs and 1725 singletons were annotated. The data were further analyzed with a focus on the gene families of the terpenoid biosynthetic pathway (TBP). We identified and characterized four TBP genes; among these were three full-length cDNAs encoding PgHMGS, PgMK, and PgMVD, whereas PgHMGR had a partial sequence based on the EST library database. Phylogenetic analysis and a pairwise identity matrix showed that these identified genes were closely related to those of other higher plants. Moreover, the tertiary structure and multiple alignment analysis showed that several distinct conserved motifs were present. Quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction results revealed that TBP genes were constitutively expressed in all organs of P. grandiflorum, while the expression of transcript levels of these genes varied distinctly among the organs. Additionally, the total amount of platycosides was highly detected in the root, accumulating in concentrations 7.8 and 2.6 times higher than in the hairy root and stem, respectively, and 1.4 times higher than in the leaf and flower. The highest amount of total phytosterols was found to accumulate in the leaves at 9.3, 9.1, 1.8, and 1.6 times higher than that of the stem, root, hairy root, and flower, respectively. After the hairy root was exposed to the MeJA treatment, the transcript levels of PgHMGS, PgHMGR, PgMK, and PgMVD had significantly increased. The highest level of transcript accumulation occurred at 3 h after initial exposure for most of the genes. Meanwhile, triterpene saponin accumulation increased with the increase in the time of exposure, and at 48 h after initial exposure, the total saponin content was the highest recorded.

Introduction

Platycodon grandiflorum A.DC. is a perennial plant that belongs to the family, Campanulaceae. It is a popular medicinal plant that has also been used as a foodstuff in Northern China and Korea. Specifically, this plant has been used as a folk remedy for the treatment of chest congestion, coughs, colds, pulmonary tuberculosis, sore throats, tonsillitis, and upper respiratory tract infections.1,2 Triterpenes such as glycoside and platycoside are the main compounds in P. grandiflorum, which possess numerous medicinal properties such as being antiallergy, antihyperlipidemia, and anti-inflammation. They are also considered to be antiobesity agents, contribute to antitumor activities, effectively augment immune responses, and stimulate apoptosis in skin cells.3−10 There are various types of triterpenoid saponin such as deapioplatycoside E, platycodin D, platyconic acid, platycoside E, polygalacin D, and polygalacin D2. Among these, platycodin D is abundantly present in P. grandiflorum and its function is well studied.2,11−15 In addition, a variety of other compounds such as phytosterols,16 polyacetylenes,17 and phenylpropanoid esters18 are also present in P. grandiflorum. Moreover, extracts of P. grandiflorum have also been found to be rich in α-spinasterol, which is a phytosterol.16 These compounds have various pharmaceutical properties which are anticarcinogenic19 and antigenotoxic,20 contribute to the antitumor activity,21 provide cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory effects,22 and also treat diabetic nephropathy.23

Terpenoids are the largest class of secondary metabolites derived from the two metabolic pathways in plants, namely, the initial pathway which is the mevalonate (MVA) pathway, and the latter which is the 2-C-methyl-d-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway. The initial step in the MVA pathway is the condensation of 3 acetyl-CoA to HMG-CoA with the help of enzymes acetoacetyl-CoA thiolase (AACT) and 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A synthase (HMGS). Second, the enzyme HMGR (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase) converts HMG-CoA into MVA. The next step is the conversion of MVA to mevalonate 5-phosphate (MVAP) via the enzyme mevalonate kinase (MK). Furthermore, mevalonate 5-diphosphate (MVAPP) is synthesized from MVAP with the aid of the enzyme 5-phosphomevalonate kinase (PMK) through the phosphorylation process. Afterward, the enzyme mevalonate diphosphate decarboxylase (MVD) helps to convert MVAPP into isopentenyl diphosphate (IPP) via the decarboxylation process. Finally, these triterpenes are derived from IPP and dimethylallyl diphosphate (DMAPP) in the cytosol via a condensation process (Figure 1). There are several gene encoding enzymes involved in the triterpenoid biosynthetic pathway (TBP) that have been identified in plants such as the Panax species,24−27P. grandiflorum,2 and Phlomis umbrosa (P. umbrosa).28 Ma et al.2 studied the transcriptome analysis of P. grandiflorum by using the root tissue. In doing so, they identified the TBP genes and analyzed the expression profile on different tissues. Recently, Kim et al.29 studied the whole-genome assembly and transcriptomic analysis of different organs such as leaves, stems, roots, petals, sepals, pistils, stamens, and seeds of Platycodon grandiflorus treated with methyl jasmonate (MeJA). However, the transcriptome analysis of the hairy root of P. grandiflorum exposed to MeJA, as well as the characterization of TBP genes, and its expression profile have not been studied. In addition, analysis of the platycoside and phytosterol contents in different organs of P. grandiflorum has not been done.

Figure 1.

Proposed TBP in P. grandiflorum. The enzymes corresponding to each enzymatic conversion reaction are shown in pink color. Asterisks denote the gene used for the gene expression.

MeJA plays a vital role in the regulation of plant growth and development.30,31 In the plant cells, MeJA can control the metabolic pathways and reaction rates through a sequence of signal transduction processes.32 MeJA also regulates the important key enzymes and the transcription factor in the biosynthetic pathway and enhances the accumulation of secondary metabolites in plants.33 A previous study reported that the effect of MeJA on TBP has been well documented in Panax ginseng. In that study, it was found that the higher expression of PgSE (squalene epoxidase) leads to a significant accumulation of ginsenoside content in the adventitious and hairy root culture of ginseng. Similarly, in Alisma orientale, the increased expression of TBP genes (AoSE1 and AoSE2) leads to a higher accumulation of 2,3-oxidosqualene and alisol B 2,3-acetate contents.34 Although these studies provide immense knowledge on the function of MeJA with respect to the gene expression and metabolic content, it remains unclear whether MeJA induces the TBP as well as terpenoid accumulation in P. grandiflorum.

To date, there is no sufficient information regarding the transcriptome analysis, the characterization of TBP pathway genes, the expression analysis, and the terpenoid accumulation of P. grandiflorum hairy root treated with MeJA, as it has not yet been studied.2,16 In addition, there was no information available regarding the contents of platycosides and phytosterols in different tissues, especially in the hairy root of P. grandiflorum under stress conditions. In the present study, we have identified, cloned, and characterized the MVA pathway genes from our expressed sequence tag (EST) data of the hairy root of P. grandiflorum treated with MeJA. In addition, to investigate the initial molecular changes that follow the exposure of P. grandiflorum hairy root to MeJA, we examined the alteration in the transcription profile of the MVA pathway genes. Meanwhile, the accumulation of valuable metabolites from various organs, particularly the hairy root of P. grandiflorum, was characterized. Our result might help us to examine the pathway in detail and stimulate further metabolic engineering-related study.

Results

Illumina Sequencing and De Novo Assembly

Because the roots of this plant have been traditionally used for medicinal purposes, the hairy root of P. grandiflorum subjected to the MeJA treatment was used for de novo sequencing and analysis. An EST library was constructed from the RNA of the MeJA-treated hairy root of P. grandiflorum. The raw EST data are available at PESTAS, http://pestas.kribb.re.kr. Here, we obtained 5760 ESTs of P. grandiflorum cDNA. After deleting the vector sequences and removing the poor-quality sequences, we obtained a total number of 2536 ESTs. After assembly, we obtained 811 contigs (cluster of assembled ESTs) and 1725 singletons (sequence found only once) with an average read length of 852 base pairs (bp). Among the 2536 ESTs, 2299 ESTs passed the annotation.

Gene Ontology

The EST sequence of the MeJA-treated hairy root of P. grandiflorum showed that a variety of genes were involved in the plant’s biological process, molecular function, and cellular components (Figure 2). Regarding the gene ontology (GO) terms, among the genes involved in the biological process, the largest proportion was assigned to the metabolic process (19%), with the others comprised as follows: electron transport (7%) and translation (5%), whereas in the molecular function, the relative categories are as follows: catalytic activity (10%), oxidoreductase activity (7%), and binding (6%). In the category of cellular component, the intracellular component, ribosome, and nucleus showed the highest hits with the percentages of 23, 13, and 12%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Functional classification of the EST library obtained from the MeJA-treated P. grandiflorum hairy root according to GO analysis. According to the GO annotation, the P. grandiflorum genes were annotated into functional categories of (A) biological process, (B) cellular component, and (C) molecular function.

Analysis of EST Data

Most abundant ESTs from the MeJA-treated hairy root of P. grandiflorum were analyzed. For these, the ESTs were sought in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) online database using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLASTX) algorithm. First, the most abundant ESTs (15 ESTs) were encoded for the delta12-fatty acid acetylenase (Table S1). Afterward, the second largest group of ESTs was annotated for the flavonoid biosynthetic pathway genes, whereas the third-largest group encodes for TBP genes (Table S2).

Cloning, Identification, and Characterization of TBP Genes

The TBP genes of P. grandiflorum were identified from the EST library prepared in our laboratory, where the cDNA was sequenced by Macrogen, South Korea. The 3′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE PCR) was performed for the three full open reading frames (ORFs) (PgHMGS, PgMK, and PgMVD) by using each gene-specific primer pair (Table S3). All polymerase chain reaction (PCR) products were subcloned in a T-blunt vector (Solgent, Korea) and sequenced for further confirmation. The identified gene sequence was deposited in the GenBank with the following accession numbers: KC439366, KC439364, and KC439365, respectively, while the partial ORF, PgHMGR, was submitted to the GenBank with accession no. KC439367. The full ORFs of PgHMGS, PgMK, and PgMVD were 1401, 1167, and 1254 bp, respectively. Moreover, the ORFs of PgHMGS, PgMK, and PgMVD encoded a protein with 466, 388, and 417 amino acids (aa); a theoretical molecular weight (MW) of 51.39, 41.01, and a kDa; and an assumed isoelectric point value (pI) of 5.73, 5.51, and 5.95, respectively (Table 1). The partial ORF of PgHMGR was 720 bp, which encoded 240 aa with a theoretical MW of 25.73 kDa and an assumed pI of 8.08.

Table 1. Molecular Characterization of TBP Genes in P. grandiflorum.

Pairwise Identity Matrix, Phylogenetic Analysis, and Motif Analysis

Pairwise identity matrix showed that PgHMGS, PgHMGR, PgMK, and PgMVD shared 87.47, 82.92, 77.52, and 86.30% of the sequence identities with the Trachyspermum ammi (T. ammi), Gossypium arboretum, Quercus suber, and T. ammi amino acid sequences, respectively (Table 2). In addition, bacteria, chlorophyta, dinoflagellates, and heterokonts showed less sequence identity when compared to the TBP amino acid sequences of other higher plants.

Table 2. Percentage Identity Analysis (%) of Amino Acid Sequences between P. grandiflorum TBP Amino Acid Sequences and Other TBP Sequencesa.

| PgHMGS | PgHMGR | PgMK | PgMVD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher Plants | ||||

| P. grandiflorum | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| G. arboreum | 82.92 | |||

| Q. suber | 77.52 | |||

| T. ammi | 87.47 | 86.30 | ||

| Bacteria | ||||

| A. baumannii | 70.87 | |||

| B. bacterium | ||||

| C. kentron | 39.27 | |||

| P. bacterium | 44.31 | |||

| V. bacterium | 30.52 | |||

| chlorophyta | ||||

| C. subellipsoidea | 51.66 | |||

| Dinoflagellates | ||||

| S. microadriaticum | 25.62 | 26.01 | ||

| Heterokonts | ||||

| E. siliculosus | 51.26 | |||

| T. clavata | 48.16 | 34.44 | 48.50 | |

Accession numbers of the sequences and full genus names are shown in Figures S1–S4.

To investigate phylogenetic relationships between TBP genes from P. grandiflorum and the TBP genes of other bacteria, chlorophyta, dinoflagellates, heterokonts, and other higher plants, as well as to generate an evolutionary framework, an unrooted neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree was constructed based on the deduced amino acid sequence of the TBP genes. As expected, all the TBP genes showed a close evolutionary relationship with higher plants, but the farthest phylogenetic distance was observed from bacteria, chlorophyte, dinoflagellates, and heterokonts (Figures S1–S4). This suggests that the TBP genes of P. grandiflorum might be from the ancestors of higher plants. In addition, it is shown that in higher plants the TBP genes are highly conserved.

The TBP amino acid sequence of P. grandiflorum, along with the sequences of bacteria, chlorophyta, dinoflagellates, heterokonts, and higher plants, was submitted into Multiple Expectation maximizations for Motif Elicitation (MEME) software to determine the conserved motif. The result showed that five common motifs were present in most of the different plant species (Figures S1–S4). However, it was noted that there was a missing motif, and the position of the motif in the P. grandiflorum HMGR protein was different. This might be due to the partial amino acid sequence. From this result, it is predicted that TBP genes had conserved motifs 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, and their location is highly homologous in a variety of higher plant species. This supports the result of phylogenetic analysis.

Amino Acid Multiple Alignment, Structure Analysis, and Protein Localization Analysis

The first enzyme in the MVA pathway is PgHMGS, which consists of the HMGS active site (NTDIEGVDSTNACYGG) at 108–123 aa position. The second enzyme is PgHMGR, which possesses a conserved motif (EMPVGY), an HMGR signature motif (RFSCSTGDAMGMNMV), and NAD(P)H-binding domains (TGDAMGMNMVS) at 73–79, 191–205, and 196–206 aa, respectively. The third enzyme in the pathway is PgMK, which consists of a peroxisomal targeting signal 2 (PTS2)-related nonapeptide (KIILAGEHA) at 9–18 aa, GHMP kinase putative ATP-binding domain (LPLGAGLGSSAA) at 138–149 aa, and three conserved motifs: PGKIILAGEH at 8–17 aa, PLGSGLGSSAA at 139–149 aa, and KLTGAGGGGC at 332–341 aa. The final enzyme in the MVA pathway is PgMVD, which possesses a PTS2-related nonapeptide (SVTLDPDHL) at the residues of 42–50 aa, ATP-binding domain at the residues of 120–137 aa (NNFPTAAGLASSAAGLAC), and three conserved motifs at residues of 65–72 aa (DRMWLNGK), 80–89 aa (EFQSCLREIR), and 120–137 aa (NNFPTAAGLASSAAGLAC) (Figures 3 and S5–S8).

Figure 3.

Predicted 3D structure of the TBP genes of P. grandiflorum. (A) PgHMGS, (B) PgHMGR (partial ORF), (C) PgMK, and (D) PgMVD structures were generated using Chimera 1.14 software.51 The amino (NH2) and carboxyl (COOH) ends are presented in blue and dark red, respectively. In addition, α-helices and β-strands are displayed in light sea green and hot pink, respectively. For the sequence alignment of each gene, see Figures S5–S8.

TBP sequences of P. grandiflorum were analyzed using CELLO2GO, ChloroP 1.1, Plant-PLoc, TargetP, and WoLF PSORT web-based programs to predict the subcellular location of these genes. Most of the P. grandiflorum TBP proteins were, through consensus, predicted to be targeted to the cytoplasm, whereas some of the TBP proteins were targeted to the chloroplast, endoplasmic reticulum, nucleus, plasma membrane, or to the mitochondrion (Table 3).

Table 3. Subcellular-Localization Predictions of P. grandiflorum TBP Genes.

| gene names | CELLO2GO | ChloroP 1.1 | plant-PLoc | targetP | WoLF PSORT | consensus prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PgHMGS | cytoplasm | other | cytoplasm | other | nucleus | cytoplasm/nucleus/other |

| PgHMGR | plasma membrane | other | endoplasmic reticulum | other | cytoplasm | cytoplasm/endoplasmic reticulum/plasma membrane/other |

| PgMK | chloroplast/cytoplasm | other | cytoplasm | other | chloroplast | chloroplast/cytoplasm/other |

| PgMVD | cytoplasm | other | chloroplast | other | nucleus | chloroplast/cytoplasm/nucleus/other |

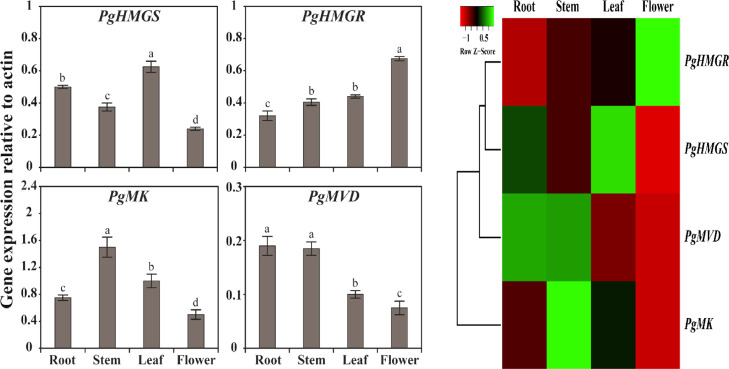

Tissue-Specific Expression of TBP Genes

The quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis result showed that all genes were constitutively expressed in all organs, while the expression of transcript levels varied distinctly among the organs. Among all the genes, PgHMGS, PgHMGR, PgMK, and PgMVD were highly expressed in the leaf, flower, stem, and root, respectively (Figure 4). PgHMGS showed the highest level of expression in the leaf, followed by the roots, stems, and flowers, which was 1.3, 1.7, and 2.6 times higher than the leaf, respectively. Interestingly, the expression level of the PgHMGR gene was significantly higher in flowers, while all the other TBP genes showed decreased expression levels in this organ. Furthermore, PgMK was upregulated in the stem, whereas decreased expression was achieved in the flower and the PgMVD gene showed the highest expression level in the root, followed by stem, leaf, and flower. From this result, it is suggested that the expression of transcript levels varies distinctly among the organs.

Figure 4.

(Left) Relative gene expression profiles of the TBP genes of P. grandiflorum. The transcriptional level of TBP genes was analyzed in different tissues including the root, stem, leaf, and flower using qRT-PCR analysis. The relative expression levels of TBP genes were normalized to actin, which was used as the reference gene. Results are given as the means of triplicates ± standard deviation. Letters a–d denote significant differences (p < 0.05). (Right) Heat map showing the expression profiles of TBP genes in different tissues. The heat map was generated using fold-change values obtained from qRT-PCR analysis. The tree view of hierarchical clustering was used to show the tissue-specific expression of TBP genes. A gradient color as the scale bar of Z-score at the top is used to illustrate the differences in transcript abundance such as high (green) and low (red).

Endogenous Metabolite Analysis

Tissue-specific accumulation of triterpenes was quantified from leaf, stem, flower, root, and also from the hairy root using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Six different platycosides were identified from the analysis of P. grandiflorum. Among these, the PGD2 content was higher than the other platycosides in all the organs. Interestingly, DPE and PE were found only in the root, while in the other organs they were not detected. Nevertheless, four compounds (PA, PD, PGD2, and PGD2) were found to accumulate in all the organs. Furthermore, among the platycosides, the accumulation of PA and PD was highest in the leaf, while the level of PGD2 and PGD was highest in the root and flower, respectively. Moreover, the hairy roots had the lowest concentrations of all the platycosides (Table 4). The total platycoside content was detected in high concentrations in the root, which was 7.8, 2.6, 1.4, and 1.4 times higher than in the hairy root, stem, leaf, and flower, respectively.

Table 4. Platycoside Contents in Different Organs, Including the Hairy Root of P. grandifloruma.

| mg/g DW | Root | Stem | leaf | flower | hairy root |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPE | 0.79 ± 0.08 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| PE | 0.61 ± 0.01 | nd | nd | nd | nd |

| PA | 0.10 ± 0.01 d | 0.02 ± 0.00 e | 0.17 ± 0.01 a | 0.16 ± 0.01 b | 0.09 ± 0.00 c |

| PD | 0.11 ± 0.00 b | 0.04 ± 0.00 e | 0.13 ± 0.00 a | 0.08 ± 0.00 c | 0.06 ± 0.00 d |

| PGD2 | 2.64 ± 0.17 a | 1.29 ± 0.05 d | 2.15 ± 0.20 b | 2.02 ± 0.31 c | 0.36 ± 0.02 e |

| PGD | 0.51 ± 0.02 c | 0.48 ± 0.01 d | 1.06 ± 0.03 b | 1.23 ± 0.02 a | 0.10 ± 0.00 e |

| Total | 4.76 ± 0.30 a | 1.83 ± 0.06 c | 3.50 ± 0.25 b | 3.48 ± 0.34 b | 0.61 ± 0.02 d |

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3). Letters a–e represent significant differences (p < 0.05). nd, not detected. DPE: deapio-platycoside E, PE: platycoside E, PA: platyconic acid, PD: platycodin D, PGD2: polygalacin D2, PGD: polygalacin D.

Phytosterol contents were measured by using gas chromatography–mass spectrometry (GC–MS), whose results indicated that the levels of β-sitosterol and β-amyrin accumulation were significantly higher in the leaf than in any other parts of the plant (Table 5). In addition, β-sitosterol and α-spinasterol were detected in all organs, but specifically, α-spinasterol was much higher than β-sitosterol in every organ. The concentration of α-spinasterol was the highest in the hairy root, followed by flower, leaf, root, and stem (Table 2). The highest amount of total phytosterols was accumulated in the leaves at levels 9.3, 9.1, 1.8, and 1.6 times higher than that of the stem, root, hairy root, and flower, respectively (Table 5).

Table 5. GC–MS Analysis of Phytosterol in Different Organs, Including the Hairy Root of P. grandifloruma.

| μg/100 mg DW | flower | leaf | stem | root | hairy root |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-sitosterol | 8.15 ± 1.00 c | 25.29 ± 5.95 a | 2.48 ± 0.71 d | 1.81 ± 0.30 e | 10.15 ± 0.18 b |

| α-spinasterol | 104.23 ± 14.70 b | 92.45 ± 0.31 c | 19.20 ± 4.42 e | 22.10 ± 4.88 d | 121.80 ± 2.32 a |

| β-amyrin | 43.6 ± 9.24 b | 125.10 ± 0.06 a | 4.52 ± 1.14 d | 2.89 ± 0.67 e | 6.52 ± 0.04 c |

| total | 156.02 ± 24.56 b | 242.84 ± 5.76 a | 26.20 ± 6.24 d | 26.80 ± 5.69 d | 138.47 ± 2.13 c |

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3). Letters a–e represent significant differences (p < 0.05).

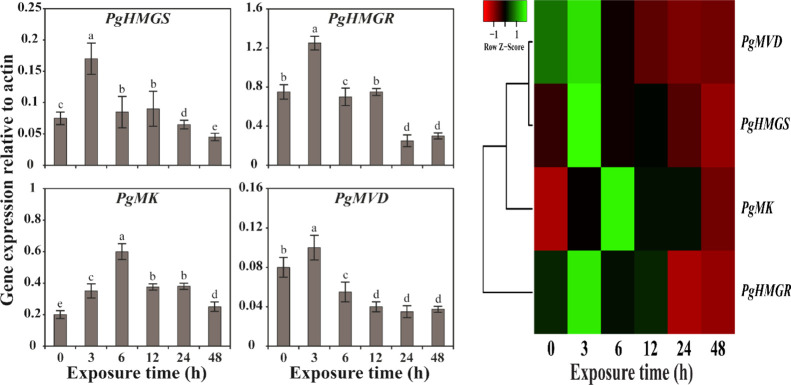

Effect of MeJA on the Gene Expression of TBP Genes in the Hairy Root of P. grandiflorum

To investigate the stress effects on the TBP gene expression, we treated the hairy root of P. grandiflorum with MeJA. The expression level of all TBP genes had increased after exposure to MeJA. In particular, the expression level of PgHMGS, PgHMGR, and PgMVD genes was highest at 3 h after initial exposure, whereas PgMK was highest at 6 h. However, the gene expression of all TBP genes had gradually decreased with the increase in exposure time (12, 24, and 48 h) (Figure 5). These results suggest that the activity of all TBP genes is positively involved in triterpene biosynthesis.

Figure 5.

(Left) Relative gene expression profiles of TBP genes of the hairy root of P. grandiflorum exposed to 100 μM MeJA. The hairy root was harvested at 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h after treatment. The relative expression levels of TBP genes were normalized to actin, which was used as the reference gene. Results are given as the means of triplicates ± standard deviation. Letters a–d denote significant differences (p < 0.05). (Right) Heat map showing the expression profiles of TBP genes in P. grandiflorum hairy root exposed to 100 μM MeJA. The heat map was generated using fold-change values obtained from qRT-PCR analysis. The tree view of hierarchical clustering was used to show the different time-course expressions of TBP genes. A gradient color as the scale bar of Z-score at the top is used to illustrate the differences in transcript abundance such as high (green) and low (red).

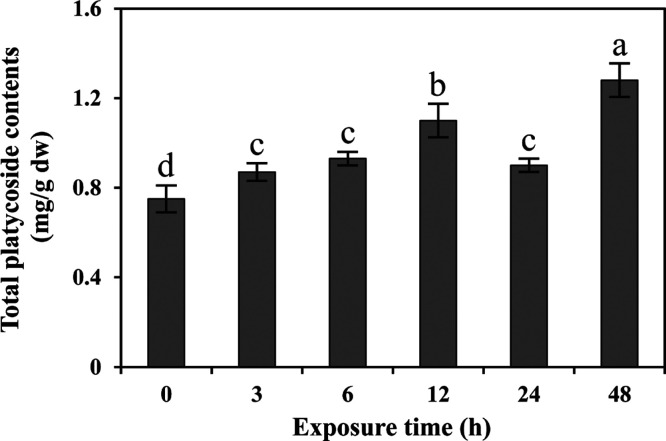

Effect of MeJA Treatment on Total Platycoside Contents in the Hairy Root of P. grandiflorum

For quantification of the total platycoside content, P. grandiflorum hairy root treated with 100 μM MeJA at different time intervals (3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h) was used. The total platycoside content gradually increased with the increase in exposure time up to 12 h and then decreased at 24 h and gradually increased at 48 h after initial exposure (Figure 6). The total platycoside contents were highest at 48 h after exposure, which was 1.7 times higher than that in the control.

Figure 6.

Total platycoside accumulation in P. grandiflorum hairy root exposed to 100 μM MeJA. Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3). Letters a–e represent significant differences (p < 0.05).

Discussion

Isoprenoids, also known as terpenoids, are one of the largest classes of natural compounds found in nature and their numbers are growing steadily.35 They consist of more than 40,000 different molecules that are biosynthetically related via the MVA pathway for the production of isoprenoids as a secondary metabolite. Triterpene saponin is the main compound in P. grandiflorum. However, the information regarding the terpenoid biosynthesis in P. grandiflorum is very scarce. Therefore, in the present study, we constructed an EST library of the hairy roots of P. grandiflorum treated with MeJA, which yielded 5760 ESTs and extensively characterized the TBP genes. In addition, we cloned, characterized, and analyzed the expression of the genes involved in the TBP.

TBP genes (PgHMGR, PgHMGS, PgMK, and PgMVD) were identified from the EST library of the MeJA-treated hairy root of P. grandiflorum. The TBP genes, which had been previously identified and characterized from higher plants, were used as queries to search against P. grandiflorum transcript databases using the BLASTN program. The identified TBP genes were submitted into the ORF finder program to recognize whether or not the gene consists of full ORF with the maximum nucleotide length. In this study, the full ORFs of PgHMGS, PgMK, and PgMVD were 1401, 1167, and 1254 bp, which encoded a protein with 466, 388, and 417 aa, respectively, whereas the partial ORF of PgHMGR was 720 bp, which encoded a protein with 240 aa. This result was consistent with the results of the previous study on the higher plant, P. umbrosa.28 In addition, multiple alignments and the three-dimensional (3D) structure of P. grandiflorum TBP amino acid sequences were found to possess highly conserved domains similar to those of the other higher plants. In P. umbrosa, PuHMGR1 and PuHMGR2 consisted of the conserved motif and NAD(P)H-binding domains, while PuMK possessed three conserved motifs in its structure. PuMVD had four conserved motifs and an ATP-binding domain was found.28 Similar conserved domains were also present in the P. grandiflorum TBP gene sequence. These results clearly illustrated that TBP genes might have a higher percentage of sequence identities with higher plants that initially theorized. This indicates that in higher plants, these TBP genes are highly conserved.

Among the four TBP pathway genes, PgHMGS was expressed at a higher level in the leaf than in the root, stem, and flower. Moreover, in the MeJA-treated hairy root of P. grandiflorum, the expression level was highest 3 h after exposure. In another study of P. grandiflorum, the highest level of PgHMGS expression was found in the leaf, followed by the stem, flower, and root.2 Moreover, in Salvia miltiorrhiza, SmHMGS showed higher expression levels in the stem than in the root, leaf, and flower; however, it did not show any significant expression in the plants treated with MeJA.36 Previous studies reported that SmHMGS might be involved in the biosynthesis of tanshinone.37,38 These results suggest that the HMGS gene might show different spatial and temporal expression patterns in various tissues. However, in the future, further studies are needed to investigate the role of HMGS in the other TBPs as it requires clarification.

In this study, PgHMGR was most highly expressed in the flowers, followed by the leaves, stems, and roots, whereas in the hairy root treated with MeJA, the expression level of PgHMGR was significantly induced after 3 h of exposure. In another study of P. grandiflorum, the expression of HMGR was highest in the following order: flower, root, stem, and leaf.2 In the perennial plant S. miltiorrhiza, the expression level of the four different isoforms of SmHMGR revealed differential expression patterns in different tissues. Specifically, SmHMGR1, SmHMGR2, SmHMGR3, and SmHMGR4 were highly expressed in flowers, stems, stems, and flowers, respectively. In addition, they found that SmHMGR1, SmHMGR2, and SmHMGR3 were significantly induced in MeJA-treated plants, whereas the expression level of SmHMGR4 remained constant.36 A recent study reported that in P. umbrosa, the expression levels of PuHMGR1 and PuHMGR2 were significantly higher in the stem and root, respectively.28 Similarly, the expression levels of most of the MVA pathway genes were highly expressed in the stem of Valeriana fauriei.39 From these examples, it has been shown that different HMGR isoforms might be involved in the synthesis of different terpenoids.40,41 Furthermore, in this study, the expression of PgHMGR was found to be lowest in the root of P. grandiflorum, which leads to the lowest accumulation of phytosterol. Meanwhile, the accumulation of phytosterol was found to be significantly higher in the hairy root of P. grandiflorum than in the root. It has been reported that the main location for tanshinone biosynthesis is the root.36 However, in S. miltiorrhiza, the expression levels of SmHMGR2 and SmHMGR4 are very low in the root when compared to other tissues of the plant. Moreover, it has also been reported that the overexpression of SmHMGR2 in the hairy root of S. miltiorrhiza led to a significant accumulation of tanshinone production.40 From these overall results, it is shown that the expression of HMGR involved in the TBP of P. grandiflorum was in a tissue-specific manner. In addition, it illustrated that PgHMGS might be involved not only in the tanshinone biosynthesis but also in the phytosterol synthesis.

In Arabidopsis, the MK gene is specifically expressed in roots and inflorescences.42 However, PgMK was highly expressed in the stem, followed by the leaf, root, and flower, and it is highly expressed in the MeJA treatment at 6 h of exposure. In another study on P. grandiflorum, the expression of PgMVK was high in the leaf than in the flower, stem, and root.2 A similar result was obtained in S. miltiorrhiza where the highest expression of SmMK was obtained in the stems, followed by the roots, leaves, and flowers, while being significantly induced in the MeJA-treated plantlets.36 This was consistent with the results of a previous study, which reported that in P. umbrosa, the highest expression of the PuMK gene was observed in the following order: stem, root, and young leaf.28 These results suggest that the MK gene might have different spatial and temporal expression patterns in various tissues. Furthermore, in P. grandiflorum the expression level of PgMVD was highest in the roots, followed by the stems, leaves, and flowers. Meanwhile, in another study, the expression of PgMVD was highest in the leaf when compared to that in the flower, root, and stem. However, in S. miltiorrhiza the SmMCD showed a higher level of expression in the stem than in other plant tissues. In addition, the expression of MK and MDC was different in the MeJA-treated plants. The above results showed that PgMK and PgMVD are coordinately involved in the TBP. Moreover, PgMK and PgMVD possess a PTS2 motif in their structure. A similar motif was found in several plant species, such as Arabidopsis thaliana,43Catharanthus roseus (C. roseus),43P. umbrosa,28 and S. militiorrhiza.36 However, the presence of PTS2 in PgMK and PgMVD does not mean that these genes are targeted to the peroxisome. For example, the CrMDC and CrMK genes from C. roseus are targeted to the peroxisome and cytosolic, respectively, even though they consist of the PTS2 motif.43 Thus, in this study, PgMK might be targeted to either chloroplast/cytoplasm, whereas, PgMVK might be targeted to the chloroplast/cytoplasm/nucleus. Nevertheless, future subcellular localization studies should be carried out to confirm the exact localization of the target protein.

From our result, we found that platycosides existed in different organs (root, leaf, flower, stem, and hairy root) and the hairy root of P. grandiflorum had the highest concentration of α-spinasterol compared to the other organs. Nevertheless, platycosides and other phytosterols were commonly detected in all the organs. Several previous studies have been reported that an elicitor significantly increases the secondary metabolic content.44−46 Kim et al.47 reported that the exposure of the P. ginseng cell suspension culture to MeJA leads to a significant accumulation of ginsenoside content. These results were consistent with our result, showing MeJA-induced TBP gene expression and total platycoside accumulation in the hairy root of P. grandiflorum. These results also indicate that the elicitor (MeJA) significantly increased the TBP gene expression and terpenoid accumulation in P. grandiflorum.

In conclusion, transcriptomic analysis of the hairy root of P. grandiflorum, treated with MeJA, was performed by using the Illumina NextSeq500 platform and 2536 ESTs were obtained. After assembly, we obtained 811 contigs and 1725 singletons with an average read length of 852 bp. Additionally, the identification and characterization of four TBP genes in P. grandiflorum were done. Among these, three genes possess a full ORF, while one gene had partial ORF. The result of multiple alignments and tertiary structure analysis showed that the P. grandiflorum TBP gene sequence shared a high degree of similarity with other higher plants. The different expression patterns and subcellular localization prediction of TBP genes illustrate the complexity of TBP in P. grandiflorum. Furthermore, the highest accumulation of platycosides and phytosterols was observed in the root and flower, respectively, of P. grandiflorum. This shows that TBP is complex and does not simply change based on variations in the mRNA expression. Moreover, it is shown that the specific group of enzymes was helpful in the synthesis of a specific group of terpenoids, which indicates that the metabolic channels in the pathway are well organized. From another point of view, the enzyme might be involved in the synthesis of different terpenoids by inserting them into diverse metabolic units. These findings will provide immense knowledge on the transcription of genes involved in TBP, as well as on the levels of metabolites accumulated at different organs of P. grandiflorum. Furthermore, this study might be helpful for the improvements of triterpenoid saponins in P. grandiflorum and other species through genetic engineering.

Methods

Plant Material and cDNA Library Construction

The hairy roots were established using Agrobacterium rhizogenes strain R1000 following the protocol previously described by Park et al.48 These roots were cultured for 3 weeks in a 100 mL flask containing 30 mL of half-strength Murashige–Skoog medium and were maintained at 25 °C in a controlled growth chamber with shaking (100 rpm) under a 16/8 h light/dark cycle (fluorescent tubes, 35 μmol/s m). After that, the culture was treated with 100 μM MeJA (Sigma, USA) for 24 h. The hairy roots were collected using vacuum filtration.

The RNAs were extracted using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and the poly A+ RNA mixtures were purified using the PolyATtract mRNA isolation system (Promega, USA). Moreover, cDNA was synthesized using the cDNA synthesis kit (Stratagene, CA). The cDNA library was constructed using the Uni-ZAP XR vector following the manufacturer’s instruction (Stratagene, CA). Furthermore, an Illumina NextSeq500 platform was used to analyze the cDNA using the commercial service of the Korea Research Institute of Bioscience and Biotechnology (KRIBB), Daejeon, South Korea. Raw reads of the EST library sequence are available on the PESTAS web server, http://pestas.kribb.re.kr.

RACE PCR and Cloning of Mevalonate Pathway Genes

MVA gene sequences were retrieved from the P. grandiflorum EST library which was prepared in our laboratory. To perform RACE PCR, RNA was extracted using a trireagent (MRC, USA) and a RNase plant mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For real-time PCR, cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of each organ’s total RNA using the SuperScript II First-Strand Synthesis kit (Life Technologies, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol while using an oligo (dT)20 primer. One microgram of total RNA was transcribed to cDNA using a GeneRacer Kit (Life Technologies, USA) while following protocol. The 3′ RACE PCR was performed for the full-length gene by using gene-specific primers (Table S1). Subsequent to this, all PCR products were subcloned in a T-blunt vector (Solgent, Korea) and sequenced.

In Silico Identification and Sequence Analysis of CBP Genes

Retrieved sequences were then analyzed using in silico BLAST in the NCBI database. In addition, sequences were analyzed by using PFAM (http://pfam.xfam.org/search) and the Conserved Domain Database (CCD) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) to predict putative protein signature motifs. Signal peptide analyses were analyzed by using SignalP 4.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/). Subcellular locations of the TBP proteins were identified using a public online program such as CELLO2GO (http://cello.life.nctu.edu.tw/cello2go/), ChloroP 1.1 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ChloroP/), Plant-PLoc (http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/plant/), TargetP 1.1 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TargetP-1.1/index.php), and WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/). The molecular weight and isoelectric point values of the protein were then calculated by using the ExPASy platform (http://ca.expasy.org/tools/pi_tool.html).

Structural Analysis of TBP Genes

Multiple sequence alignment was done using BioEdit 7.2.5.49 TBP protein sequences were then submitted to the Phyre2 online web server50 for homology modeling and 3D structures were generated by using Chimera 1.14 software.51 Conserved signature motifs among the TBP genes were found using the MEME tools.52

Phylogenetic Analysis and Percent Identity Matrix

The phylogenetic tree was constructed using MEGA7 software53 and the neighbor-joining (NJ) method.54 The robustness of the trees was estimated by performing 1000 bootstrap replicates.55 The percent identity matrix between the TBP amino acid sequences was calculated using Clustal Omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/), and identities were calculated from the pairwise and multiple sequence alignments.56

Collection of Different Organs and Hairy Root Stress Treatment

P. grandiflorum plants were grown at the experimental field of Chungnam National University (Daejeon, Korea). Samples from these plants (root, stem, leaf, and flower) were harvested at the flowering stage of the plant growth. For hairy root stress treatment, a 3-week-old hairy root culture was treated with 100 μM MeJA solution, and the samples were collected using vacuum filtration at different time intervals (0, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h). The collected samples were quickly frozen by being immersed in liquid nitrogen at −196 °C for 5 min and later stored at −80 °C until further analysis. Each treatment was carried out in triplicate.

Gene Expression Using Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Expression levels were measured by qRT-PCR. The gene-specific primer used for qRT-PCR is shown in Table S2. The PCRs were carried out in a Mini Opticon (Bio-rad, USA) using the QIAGEN QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR system. The qRT-PCR cyclic condition was similar to the protocol described by Kim et al.16Actin was used as a housekeeping gene, and the transcription levels were calculated relative to actin.

Total Saponin Extraction and HPLC Analysis

Each tissue sample (root, stem, leaf, flower, and hairy root) underwent extraction of total saponins, and HPLC analysis was performed as described by Kim et al.16 Finely powdered samples of 500 mg were mixed with 10 mL of 100% MeOH before being sonicated for 30 min. From this crude extract, 4 mL was taken and concentrated by using a speed vacuum. To this, 200 μL of MeOH was added, and the entire mixture was filtered with a 0.45 μm poly(tetrafluoroethylene) syringe filter. The filtrate was then injected into the HPLC system (NS-4000, Futecs Co., Daejeon, Korea) coupled with an evaporation light-scattering detector for the analysis of six platycosides (i.e., Deapio-platycoside E, platycodin D, platyconic acid, platycoside E, polygalacin D, and polygalacin D2). HPLC conditions, gradient programs, and flow rate were used according to the protocol described by Kim et al.16 Furthermore. saponin identification and quantification were done by comparing the retention times and the HPLC peak areas, respectively, with reference to a standard or by the spike test. All samples were analyzed in triplicate.

Extraction, Derivatization, and GC-TOF MS Analysis

Sterol extraction was performed according to the method previously described by Du and Ahn57 with a slight modification. Sterol components were extracted from the 100 mg fine-powdered samples. To this, 3 mL of ethanol consisting of 0.1% ascorbic acid (w/v) and 0.05 mL of 5α-colestane (10 μg/mL) was added and thoroughly vortexed for 20 s before being immediately incubated at 85 °C for 5 min in a water bath. After incubation, 120 μL of 80% potassium hydroxide was added, and then, the mixture was vortexed for 20 s before being incubated once more at 85 °C for 10 min in a water bath. Afterward, the samples were immediately kept on ice, and then 1.5 mL of sterile deionized water was added. Subsequently, 1.5 mL of hexane was added into the above mixture, which was then vortexed for 20 s and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 5 min. The resulting supernatant was transferred into a separate Eppendorf tube, and then, the remaining pellet was re-extracted by using hexane. Using the hexane fraction, derivatization was done according to the protocol previously described by Du and Ahn.57 The injection volume, injector temperature, flow rate, temperature program, transfer line temperature, ion-source temperature, scanned mass range, and detector voltage were similar to those of the protocol described by Kim et al.16

Statistical Analysis

In this study, all results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 3), and all data were all analyzed using the Statistical Analysis System version 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA, 2009). Duncan’s multiple range test, a method to make comparisons between groups of means at α < 0.05, was carried out.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the funds from the Incheon National University Research grant in 2019.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.1c01202.

Phylogeny of deduced PgHMGS, PgHMGR, PgMK, and PgMVD amino acid sequences along with other HMGS sequences; conserved protein motif 1–5 present in the variable region of PgHMGS, PgHMGR, PgMK, and PgMVD genes; amino acid alignment of deduced PgHMGS, PgHMGR, PgMK, and PgMVD with selected corresponding genes; RACE PCR primers used in this study; qRT-PCR primers used in the gene expression; most abundant unigenes obtained from the EST library of MeJA-treated P. grandiflorum hairy root; and unigenes encoding for flavonoid and TBP genes obtained from the EST library of MeJA-treated P. grandiflorum hairy root (PDF)

Author Contributions

# Y.-K.K. and R.S. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Lee E. B. Pharmacological studies on Platycodon grandiflorum A.DC.IV. A Comparison of experimental pharmacological effects of crude platycodin with clinical indications of Platycodi radix. Yakugaku Zasshi 1973, 93, 1188–1194. 10.1248/yakushi1947.93.9_1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma C.-H.; Gao Z.-J.; Zhang J.-J.; Zhang W.; Shao J.-H.; Hai M.-R.; Chen J.-W.; Yang S.-C.; Zhang G.-H. Candidate genes involved in the biosynthesis of triterpenoid saponins in Platycodon grandiflorum identified by transcriptome analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 673. 10.3389/fpls.2016.00673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn K. S.; Noh E. J.; Zhao H. L.; Jung S. H.; Kang S. S.; Kim Y. S. Inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase II by Platycodon grandiflorum saponins via suppression of nuclear factor-κB activation in RAW 264.7 cells. Life Sci. 2005, 76, 2315–2328. 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S.-S.; Han E.-J.; Lee T.-H.; Han K.-J.; Lee H.-K.; Suh H.-W. Antinociceptive profiles of platycodin D in the mouse. Am. J. Chin. Med. 2004, 32, 257–268. 10.1142/s0192415x04001916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han L.-K.; Zheng Y.-N.; Xu B.-J.; Okuda H.; Kimura Y. Saponins from platycodi radix ameliorate high fat diet-induced obesity in mice. J. Nutr. 2002, 132, 2241–2245. 10.1093/jn/132.8.2241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. Y.; Hwang Y. P.; Kim D. H.; Han E. H.; Chung Y. C.; Roh S. H.; Jeong H. G. Inhibitory effect of the saponins derived from roots of Platycodon grandiflorum on carrageenan-induced inflammation. Biosci., Biotechnol., Biochem. 2006, 70, 858–864. 10.1271/bbb.70.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.; Choi C. Y.; Chung Y. C.; Kim Y. S.; Ryu S. Y.; Roh S. H.; Jeong H. G. Protective effect of saponins derived from roots of Platycodon grandiflorum on tert-butyl hydroperoxide-induced oxidative hepatotoxicity. Toxicol. Lett. 2004a, 147, 271–282. 10.1016/j.toxlet.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.-H.; Jeong J.-H.; Seo J.-W.; Shin C.-G.; Kim Y.-S.; In D.-C.; Yi J.-S.; Choi Y.-E. Enhanced triterpene and phytosterol biosynthesis in Panax ginseng overexpressing squalene synthase gene. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004b, 45, 976–984. 10.1093/pcp/pch126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C.; Schuller Levis G. B.; Lee E. B.; Levis W. R.; Lee D. W.; Kim B. S.; Park S. Y.; Park E. Platycodin D and D3 isolated from the root of Platycodon grandiflorum modulate the production of nitric oxide and secretion of TNF-α in activated RAW 264.7 cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2004, 4, 1039–1049. 10.1016/j.intimp.2004.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao H. L.; Cho K.-H.; Ha Y. W.; Jeong T.-S.; Lee W. S.; Kim Y. S. Cholesterol-lowering effect of platycodin D in hypercholesterolemic ICR mice. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2006, 537, 166–173. 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu W.-W.; Dou D.-Q.; Shimizu N.; Takeda T.; Pei Y.-H.; Chen Y.-J. Studies on the chemical constituents from the roots of Platycodon grandiflorum. J. Nat. Med. 2006a, 60, 68–72. 10.1007/s11418-005-0008-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu W.-W.; Shimizu N.; Dou D.-Q.; Takeda T.; Fu R.; Pei Y.-H.; Chen Y.-J. Five new triterpenoid saponins from the roots of Platycodon grandiflorum. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 2006b, 54, 557–560. 10.1248/cpb.54.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He Z.; Qiao C.; Han Q.; Wang Y.; Ye W.; Xu H. New triterpenoid saponins from the roots of Platycodon grandiflorum. Tetrahedron 2005, 61, 2211–2215. 10.1016/j.tet.2004.12.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii H.; Tori K.; Tozyo T.; Yoshimura Y. Structures of polygalacin-D and -D2, platycodin-D and -D2, and their monoacetates, saponins isolated from Platycodon grandiflorum A. DC., determined by carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1978, 26, 674–677. 10.1248/cpb.26.674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W.; Xiang L.; Zhang J.; Zheng Y. N.; Han L. K.; Saito M. A new triterpenoid saponin from the roots of Platycodon grandiflorum. Chin. Chem. Lett. 2007, 18, 306–308. 10.1016/j.cclet.2007.01.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.-K.; Kim J. K.; Kim Y. B.; Lee S.; Kim S.-U.; Park S. U. Enhanced accumulation of phytosterol and triterpene in hairy root cultures of Platycodon grandiflorum by overexpression of Panax ginseng 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A reductase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 1928–1934. 10.1021/jf304911t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahn J. C.; Hwang B.; Tada H.; Ishimaru K.; Sasaki K.; Shimomura K. Polyacetylenes in hairy roots of Platycodon grandiflorum. Phytochemistry 1996, 42, 69–72. 10.1016/0031-9422(95)00849-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.-Y.; Yoon J.-W.; Kim C.-T.; Lim S.-T. Antioxidant activity of phenylpropanoid esters isolated and identified from Platycodon grandiflorum A. DC. Phytochemistry 2004c, 65, 3033–3039. 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villaseñor I. M.; Domingo A. P. Anticarcinogenicity potential of spinasterol isolated from squash flowers. Teratog., Carcinog., Mutagen. 2000, 20, 99–105. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villaseñor I. M.; Lemon P.; Palileo A.; Bremner J. B. Antigenotoxic spinasterol from Cucurbita maxima flowers. Mutat. Res., Environ. Mutagen. Relat. Subj. 1996, 360, 89–93. 10.1016/0165-1161(95)00071-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeon G.-C.; Park M.-S.; Yoon D.-Y.; Shin C.-H.; Sin H.-S.; Um S.-J. Antitumor activity of spinasterol isolated from Pueraria roots. Exp. Mol. Med. 2005, 37, 111–120. 10.1038/emm.2005.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong G.-S.; Li B.; Lee D.-S.; Kim K. H.; Lee I. K.; Lee K. R.; Kim Y.-C. Cytoprotective and anti-inflammatory effects of spinasterol via the induction of heme oxygenase-1 in murine hippocampal and microglial cell lines. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2010, 10, 1587–1594. 10.1016/j.intimp.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S. I.; Kim K. J.; Choi M. K.; Keum K. S.; Lee S.; Ahn S. H.; Back S. H.; Song J. H.; Ju Y. S.; Choi B. K.; Jung K. Y. α-Spinasterol isolated from the root of Phytolacca americana and its pharmacological property on diabetic nephropathy. Planta Med. 2004, 70, 736–739. 10.1055/s-2004-827204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S.; Luo H.; Li Y.; Sun Y.; Wu Q.; Niu Y.; Song J.; Lv A.; Zhu Y.; Sun C.; Steinmetz A.; Qian Z. 454 EST analysis detects genes putatively involved in ginsenoside biosynthesis in Panax ginseng. Plant Cell Rep. 2011, 30, 1593. 10.1007/s00299-011-1070-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C.; Zhu Y.; Guo X.; Sun C.; Luo H.; Song J.; Li Y.; Wang L.; Qian J.; Chen S. Transcriptome analysis reveals ginsenosides biosynthetic genes, microRNAs and simple sequence repeats in Panax ginseng C. A. Meyer. BMC Genomics 2013, 14, 245. 10.1186/1471-2164-14-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo H.; Sun C.; Sun Y.; Wu Q.; Li Y.; Song J.; Niu Y.; Cheng X.; Xu H.; Li C.; Liu J.; Steinmetz A.; Chen S. Analysis of the transcriptome of Panax notoginseng root uncovers putative triterpene saponin-biosynthetic genes and genetic markers. BMC Genomics 2011, 12, S5. 10.1186/1471-2164-12-s5-s5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C.; Li Y.; Wu Q.; Luo H.; Sun Y.; Song J.; Lui E. M. K.; Chen S. De novo sequencing and analysis of the American ginseng root transcriptome using a GS FLX Titanium platform to discover putative genes involved in ginsenoside biosynthesis. BMC Genomics 2010, 11, 262. 10.1186/1471-2164-11-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang S.-Y.; Lee S.-H.; Lee Y.-S.; Han S.-H.; Song B.-H.; Reddy C. S.; Kim Y. B.; Park S. U. Molecular characterization of terpenoid biosynthetic genes and terpenoid accumulation in Phlomis umbrosa Turczaninow. Hortic 2020, 6, 76. 10.3390/horticulturae6040076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J.; Kang S.-H.; Park S.-G.; Yang T.-J.; Lee Y.; Kim O. T.; Chung O.; Lee J.; Choi J.-P.; Kwon S.-J. Whole-genome, transcriptome, and methylome analyses provide insights into the evolution of platycoside biosynthesis in Platycodon grandiflorus, a medicinal plant. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 112. 10.1038/s41438-020-0329-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji Y.; Liu J.; Xing D. Low concentrations of salicylic acid delay methyl jasmonate-induced leaf senescence by up-regulating nitric oxide synthase activity. J. Exp. Bot. 2016, 67, 5233–5245. 10.1093/jxb/erw280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou M.; Memelink J. Jasmonate-responsive transcription factors regulating plant secondary metabolism. Biotechnol. Adv. 2016, 34, 441–449. 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.-S.; Yeung E. C.; Hahn E.-J.; Paek K.-Y. Combined effects of phytohormone, indole-3-butyric acid, and methyl jasmonate on root growth and ginsenoside production in adventitious root cultures of Panax ginseng CA Meyer. Biotechnol. Lett. 2007, 29, 1789–1792. 10.1007/s10529-007-9442-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves S.; Romano A.. Production of Plant Secondary Metabolites by Using Biotechnological Tools. Secondary Metabolites, Sources, and Applications; IntechOpen, 2018; pp 81–99. [Google Scholar]

- Tian R.; Gu W.; Gu Y.; Geng C.; Xu F.; Wu Q.; Chao J.; Xue W.; Zhou C.; Wang F. Methyl jasmonate promote protostane triterpenes accumulation by up-regulating the expression of squalene epoxidases in Alisma orientale. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 18139. 10.1038/s41598-019-54629-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis E. M.; Croteau R.. Cyclization Enzymes in the Biosynthesis of Monoterpenes, Sesquiterpenes, and Diterpenes. Biosynthesis Aromatic Polyketides, Isoprenoids, Alkaloids; Springer: Berlin, Heidelberg, 2000; pp 53–95. [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; Yuan L.; Wu B.; Li X. e.; Chen S.; Lu S. Genome-wide identification and characterization of novel genes involved in terpenoid biosynthesis in Salvia miltiorrhiza. J. Exp. Bot. 2012, 63, 2809–2823. 10.1093/jxb/err466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G.; Huang L.; Tang X.; Zhao J. Candidate genes involved in tanshinone biosynthesis in hairy roots of Salvia miltiorrhiza revealed by cDNA microarray. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 38, 2471–2478. 10.1007/s11033-010-0383-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L.; Yan X.; Wang J.; Li S.; Liao P.; Kai G. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of a new putative gene encoding 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase from Salvia miltiorrhiza. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2011, 33, 953–961. 10.1007/s11738-010-0627-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y.; Arasu M.; Al-Dhabi N.; Lim S.; Kim Y.; Lee S.; Park S. Expression of terpenoid biosynthetic genes and accumulation of chemical constituents in Valeriana fauriei. Molecules 2016, 21, 691. 10.3390/molecules21060691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai Z.; Cui G.; Zhou S.-F.; Zhang X.; Huang L. Cloning and characterization of a novel 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase gene from Salvia miltiorrhiza involved in diterpenoid tanshinone accumulation. J. Plant Physiol. 2011, 168, 148–157. 10.1016/j.jplph.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao P.; Zhou W.; Zhang L.; Wang J.; Yan X.; Zhang Y.; Zhang R.; Li L.; Zhou G.; Kai G. Molecular cloning, characterization and expression analysis of a new gene encoding 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase from Salvia miltiorrhiza. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2009, 31, 565–572. 10.1007/s11738-008-0266-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lluch M. A.; Masferrer A.; Arró M.; Boronat A.; Ferrer A. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of the mevalonate kinase gene from Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 2000, 42, 365–376. 10.1023/a:1006325630792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin A. J.; Guirimand G.; Papon N.; Courdavault V.; Thabet I.; Ginis O.; Bouzid S.; Giglioli-Guivarc’h N.; Clastre M. Peroxisomal localisation of the final steps of the mevalonic acid pathway in planta. Planta 2011, 234, 903. 10.1007/s00425-011-1444-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundlach H.; Müller M. J.; Kutchan T. M.; Zenk M. H. Jasmonic acid is a signal transducer in elicitor-induced plant cell cultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992, 89, 2389–2393. 10.1073/pnas.89.6.2389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi H.; Huang P.; Inoue K. Up-regulation of soyasaponin biosynthesis by methyl jasmonate in cultured cells of Glycyrrhiza glabra. Plant Cell Physiol. 2003, 44, 404–411. 10.1093/pcp/pcg054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki H.; Reddy M. S. S.; Naoumkina M.; Aziz N.; May G. D.; Huhman D. V.; Sumner L. W.; Blount J. W.; Mendes P.; Dixon R. A. Methyl jasmonate and yeast elicitor induce differential transcriptional and metabolic re-programming in cell suspension cultures of the model legume Medicago truncatula. Planta 2005, 220, 696–707. 10.1007/s00425-004-1387-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y.-K.; Kim Y. B.; Kim J. K.; Kim S.-U.; Park S. U. Molecular cloning and characterization of mevalonic acid (MVA) pathway genes and triterpene accumulation in Panax ginseng. J. Korean Soc. Appl. Biol. Chem. 2014, 57, 289–295. 10.1007/s13765-014-4008-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park N. I.; Tuan P. A.; Li X.; Kim Y. K.; Yang T. J.; Park S. U. An efficient protocol for genetic transformation of Platycodon grandiflorum with Agrobacterium rhizogenes. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2011, 38, 2307–2313. 10.1007/s11033-010-0363-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall T. A.BioEdit: A User-Friendly Biological Sequence Alignment Editor and Analysis Program for Windows 95/98/NT, Nucleic Acids Symposium Series; Information Retrieval Ltd.: London, c1979-c2000, 1999; pp 95–98.

- Kelley L. A.; Mezulis S.; Yates C. M.; Wass M. N.; Sternberg M. J. E. The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2015, 10, 845–858. 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pettersen E. F.; Goddard T. D.; Huang C. C.; Couch G. S.; Greenblatt D. M.; Meng E. C.; Ferrin T. E. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004, 25, 1605–1612. 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey T. L.; Boden M.; Buske F. A.; Frith M.; Grant C. E.; Clementi L.; Ren J.; Li W. W.; Noble W. S. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. 10.1093/nar/gkp335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S.; Stecher G.; Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016, 33, 1870–1874. 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitou N.; Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1987, 4, 406–425. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evol 1985, 39, 783–791. 10.2307/2408678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madeira F.; Park Y. M.; Lee J.; Buso N.; Gur T.; Madhusoodanan N.; Basutkar P.; Tivey A. R. N.; Potter S. C.; Finn R. D.; Lopez R. The EMBL-EBI search and sequence analysis tools APIs in 2019. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, W636–W641. 10.1093/nar/gkz268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du M.; Ahn D. U. Simultaneous analysis of tocopherols, cholesterol, and phytosterols using gas chromatography. J. Food Sci. 2002, 67, 1696–1700. 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2002.tb08708.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.