Abstract

We aimed to determine the association between the intensive care unit (ICU) model and in-hospital mortality of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock.

This was a secondary analysis of a multicenter prospective observational study conducted in 59 ICUs in Japan from January 2016 to March 2017. We included adult patients (aged ≥16 years) with severe sepsis and septic shock based on the sepsis-2 criteria who were admitted to an ICU with a 1:2 nurse-to-patient ratio per shift. Patients were categorized into open or closed ICU groups, according to the ICU model. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality.

A total of 1018 patients from 45 ICUs were included in this study. Patients in the closed ICU group had a higher severity score and higher organ failure incidence than those in the open ICU group. The compliance rate for the sepsis care 3-h bundle was higher in the closed ICU group than in the open ICU group. In-hospital mortality was not significantly different between the closed and open ICU groups in a multilevel logistic regression analysis (odds ratio = 0.83, 95% confidence interval; 0.52–1.32, P = .43) and propensity score matching analysis (closed ICU, 21.2%; open ICU, 25.7%, P = .22).

In-hospital mortality between the closed and open ICU groups was not significantly different after adjusting for ICU structure and compliance with the sepsis care bundle.

Keywords: ICU model, in-hospital mortality, sepsis, sepsis care bundle

1. Introduction

Sepsis, a common condition in patients admitted to intensive care units (ICU), is a leading cause of death during ICU and hospital stays. The prognosis for patients diagnosed with sepsis has improved, due to early recognition of sepsis and the development of sepsis care bundles, including fluid resuscitation, proper use of antibacterial drugs, and vasopressors. However, recent worldwide prospectively collected data revealed that hospital mortality in patients diagnosed with sepsis when admitted to the ICU was 30.3% (95% confidence interval (CI), 27.1–33.6%) and hospital mortality in patients with septic shock on ICU admission was 43.0% (95% CI, 39.9–46.2%).[1] Sepsis remains to be a burden for ICU patients. Therefore, we need to improve the quality of sepsis management and, consequently, sepsis prognosis.

The quality of medical care was assessed using three Donabedian concepts: structure, process, and outcome.[2] To improve sepsis prognosis, structure, and process are important. Most sepsis and septic shock patients are admitted to the ICU. Thus, the ICU structure might play a role in sepsis prognosis. In the ICU structure, the ICU model has influenced outcome of patients with critical illness and sepsis.[3–7] When considering the process, the proper use of treatments and devices including antibacterial drugs, renal replacement therapy and mechanical ventilation, and compliance with clinical practice guidelines for sepsis and septic shock are important.

Currently, there are only a few studies that focused on the ICU model in the structure when evaluating sepsis care.[7,8] Hence, this study aimed to investigate the association between the ICU model and the prognosis of patients with severe sepsis and septic shock.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study design, setting, and participants

In this study, the ICU model and outcome of patients with severe sepsis were evaluated using the database from the Focused Outcomes Research in Emergency Care in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Sepsis, and Trauma (FORECAST) study. The FORECAST study was a multicenter, prospective observational study that enrolled consecutive patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, and trauma who were admitted to 59 ICUs in Japan from January 2016 to March 2017, and the data was collected by physicians at each ICU. In this study, the sepsis part included adult patients (aged ≥ 16 years) with severe sepsis based on the 2003 sepsis-2 criteria.[9] The inclusion criteria were patients suspected to have or were diagnosed with new-onset infection based on the history of the present illness, patients who met ≥ 2 systemic inflammatory response syndrome criteria, and patients who had at least one occurrence of organ dysfunction. Also, the sepsis-2 criteria included systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg, mean arterial pressure (MAP) < 65 mmHg, or a decrease in blood pressure > 40 mmHg; serum creatinine > 2.0 mg/dL or diuresis (urine output < 0.5 mL/kg/h); total bilirubin > 2.0 mg/dL; platelet count < 100,000 cells/mm3; arterial lactate > 2 mmol/L; international normalized ratio > 1.5; and arterial hypoxemia (partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2)/fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) < 200 with pneumonia or PaO2/FIO2 < 250 without pneumonia).[9] The exclusion criteria included the limitation of sustained life care or post-cardiopulmonary arrest resuscitation status at the time of sepsis diagnosis. Details of the FORECAST study were published elsewhere.[10] For this study, patients admitted to ICUs with a 1:2 nurse-to-patient ratio per shift were included. Patients admitted to ICUs with a 1:4 nurse-to-patient ratio per shift were excluded to make ICU characteristics uniform. Patients with missing in-hospital mortality data were also excluded.

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of all participating institutions in the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (JAAM) study group (IRB No.014–0306 in Hokkaido University, the representative institution for FORECAST). The need for informed consent from study participants was waived under the approval of the ethics committees.

2.2. Data collection and end point

Data compiled by FORECAST investigators were obtained from the FORECAST database. Facility information included the structure characteristics of the ICU, ICU beds, and the number of certified intensivists. Patient information included the demographic characteristics of the patients, admission source, comorbidities, Charlson comorbidity index score, activities of daily living (ADLs), suspected sites of infection at admission, organ dysfunctions, sepsis-related severity scores, details of antibiotic use, treatment for severe sepsis, septic shock, ICU-free days, ventilator-free days (VFDs), length of hospital stay (LOS), and in-hospital mortality. VFD was defined as the number of days within the first 28 days after enrolment during which a patient was able to breathe without a ventilator. Patients who died during the study period were assigned with a VFD of 0. ICU-free days were calculated in the same manner. In addition, data on compliance with sepsis care bundles proposed in the 2012 Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines (SSCG) were obtained. Compliance was described as evidence that all bundle elements were achieved within the appropriate time frame (i.e., 3 h or 6 h) and were adhered to the indications (i.e., septic shock or lactate level > 4 mmol/L). Data collection was performed as part of the routine clinical workup. The primary outcome was in-hospital mortality.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Patients were categorized into open ICU or closed ICU groups in accordance with the ICU model. Each ICU subjectively described its structure including the ICU model at the initiation of the FORECAST study.

Nonnormally distributed continuous data were presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs) and were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Categorical data were summarized as percentages and counts and were compared using Fisher's exact test or χ 2 test. For the primary outcome, a multilevel logistic regression analysis was conducted to adjust for differences in characteristics of the institutions. The variables applied to the multilevel logistic regression analysis were teaching facility, ICU beds, ICU beds per certified intensivist, age, gender, and BMI of patients, admission source, Charlson comorbidity index score, ADLs, suspected sites of infection, positive blood culture, septic shock, sepsis-related organ failure assessment (SOFA) score, and compliance rate for the entire 3-h bundle. Facility, patient background, and other variables associated with hospital mortality based on previous studies were selected.[7,8,11,12] For the sepsis care bundles, only the entire 3-h bundle was selected because the compliance rate of the entire 6-h bundle was very low. Data were presented as odds ratio (OR) with 95% CI. As a sensitivity analysis, a propensity score matching analysis with the same variables as the multilevel logistic regression analysis was performed. For the propensity score matching analysis, calipers of width equal to 0.2 of the standard deviation were used.

P values were two-sided and P < .05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., NC, USA) and STATA 14.0 (StataCorp, TX, USA).

3. Results

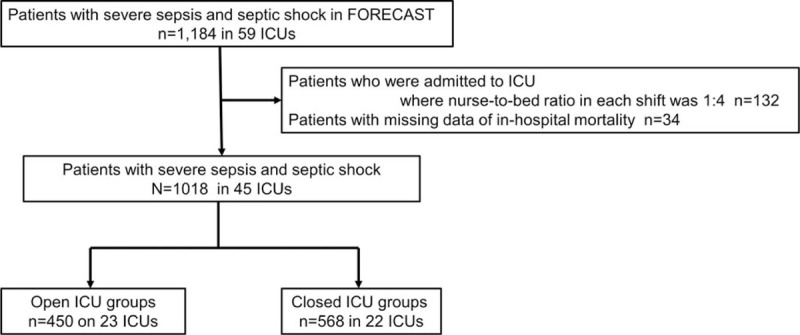

Of the 1184 patients registered in the FORECAST study, 132 patients who were admitted to ICUs with a nurse-to-bed ratio of 1:4 per shift and 34 patients with missing in-hospital mortality data were excluded. Thus, 1018 patients in 45 ICUs were included in this study. Among these patients, 450 patients in 23 ICUs were categorized to the open ICU group and 568 patients in 22 ICUs were categorized to the closed ICU group (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study participants. FORECAST = Focused Outcomes Research in Emergency Care in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Sepsis, and Trauma, ICU = Intensive Care Unit.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study facilities. Teaching facility, the number of ICU beds, ICU patients per year, the number of certified intensivists, and ICU beds per certified intensivist were not statistically different between the two groups. Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of study patients. All patient demographics, except gender, were not statistically significant between the two groups. The most common suspected site of infection in the closed ICU group was the abdomen, followed by the lung, whereas in the open ICU group, the most common suspected site of infection was the lung, followed by the abdomen. Incidence rates of positive blood culture (60.2 vs. 52.0%, P = .008) and septic shock (67.6 vs. 54.7%, P < .001) were higher in the closed ICU group than in the open ICU group. Regarding organ dysfunction upon arrival in the ICU, incidence rates of hypotension (53.4 vs. 44.9%, P = .007) and thrombocytopenia (32.9 vs. 24.4%, P = .003) were higher in the closed ICU group. As for the severity score, the closed ICU group had a higher SOFA score than the open ICU group (9 vs. 8, P = .009).

Table 1.

Characteristics of study facilities.

| Open ICU | Closed ICU | |||

| n = 23 | n = 22 | P value | ||

| Teaching facility | no (%) | 11 (47.8) | 16 (72.7) | .09 |

| ICU beds | Median (IQR) | 12 (8–16) | 13 (10–18) | .55 |

| ICU beds category | ||||

| 1–10 | no (%) | 9 (39.1) | 8 (36.4) | .87 |

| 11–20 | no (%) | 12 (52.2) | 11 (50.0) | |

| 21 - | no (%) | 2 (8.7) | 3 (13.6) | |

| ICU patients per year | Median (IQR) | 799 (550–1000) | 791 (420–988) | .61 |

| Certified intensivists | Median (IQR) | 1 (0–3) | 2 (1–3) | .17 |

| ICU beds per a certified intensivist | Median (IQR) | 3 (2–14) | 5 (2–9) | .08 |

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of study patients (n = 1018).

| Open ICU | Closed ICU | ||||

| n = 450 | n = 568 | P value | Missing | ||

| Age | Median (IQR) | 73 (65–82) | 72 (62–81) | 0.05 | – |

| Gender | |||||

| male | no (%) | 292 (64.9) | 334 (58.8) | 0.048 | – |

| BMI | Median (IQR) | 21.6 (19.0–25.1) | 21.8 (19.0–24.4) | 0.66 | 7 |

| Admission source | |||||

| Emergency Department | no/total (%) | 258/450 (57.3) | 297/567 (52.4) | 0.06 | 1 |

| Transfer or other departments | no/total (%) | 185/450 (40.0) | 240/567 (42.3) | ||

| ICU | no/total (%) | 12/450 (2.7) | 30/567 (5.3) | ||

| Coexisting conditions | |||||

| Myocardial infarction | no (%) | 22 (4.9) | 29 (5.1) | 0.87 | – |

| Congestive heart failure | no (%) | 53 (11.8) | 56 (9.9) | 0.33 | – |

| Cerebrovascular disease | no (%) | 49 (10.9) | 66 (11.6) | 0.71 | – |

| Dementia | no (%) | 44 (9.8) | 36 (6.3) | 0.04 | – |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | no (%) | 31 (6.9) | 40 (7.0) | 0.92 | – |

| Diabetes mellitus | no (%) | 105 (23.3) | 138 (24.3) | 0.72 | – |

| Chronic kidney disease | no (%) | 31 (6.9) | 45 (7.9) | 0.53 | – |

| Malignancy (solid or blood) | no (%) | 72 (16.0) | 76 (13.4) | 0.23 | |

| Moderate to severe Liver disease | no (%) | 8 (1.8) | 15 (2.6) | 0.36 | – |

| Charlson comorbidity index | Median (IQR) | 1 (0–2) | 1 (0–2) | 0.40 | – |

| ADL | |||||

| dependent | no/total (%) | 106/449 (23.6) | 140/567 (24.7) | 0.69 | 2 |

| Medication | |||||

| Steroids | no (%) | 56 (12.4) | 77 (13.6) | 0.60 | – |

| Immunosuppressant | no (%) | 16 (3.6) | 23 (4.1) | 0.68 | – |

| Suspect site of infection | |||||

| Lung | no (%) | 177 (39.3) | 144 (25.3) | <0.001 | – |

| Abdomen | no (%) | 111 (24.7) | 161 (28.3) | ||

| Urinary tract | no (%) | 73 (16.2) | 108 (19.0) | ||

| Blood stream infection/endocardium/Catheter/Implant device | no (%) | 11 (2.4) | 29 (5.1) | ||

| Central nerve system | no (%) | 6 (1.3) | 13 (2.3) | ||

| Osteoarticular | no (%) | 4 (0.9) | 9 (1.6) | ||

| Skin/soft tissue | no (%) | 45 (10.0) | 59 (10.4) | ||

| Wound | no (%) | 3 (0.7) | 6 (1.1) | ||

| Other | no (%) | 20 (4.5) | 39 (6.9) | ||

| Positive blood cultures | no/total (%) | 234/450 (52.0) | 339/563 (60.2) | 0.008 | 5 |

| Septic shock | no (%) | 246 (54.7) | 384 (67.6) | <0.001 | – |

| Initial serum lactate | Median (IQR) | 3.1 (1.8–5.5) | 3.0 (1.9–5.2) | 0.59 | 73 |

| Organ dysfunction on arrival | |||||

| Hypotension | no/total (%) | 202/450 (44.9) | 303/568 (53.4) | 0.007 | – |

| Hyperlactatemia (> 2mmol/L) | no/total (%) | 291/450 (64.7) | 379/568 (66.7) | 0.49 | – |

| Acute kidney injury (Creatinine > 2.0mg/dl) | no/total (%) | 170/450 (37.8) | 217/568 (38.2) | 0.89 | – |

| Acute lung injury | no/total (%) | 54/401 (13.5) | 83/536 (15.5) | 0.39 | – |

| Hyperbilirubinemia (> 20. Mg/dL) | no/total (%) | 74/450 (16.4) | 102/568 (18.0) | 0.53 | – |

| Thrombocytopenia (< 100,000/μL) | no/total (%) | 110/450 (24.4) | 187/568 (32.9) | 0.003 | – |

| Coagulopathy (PT-INR > 1.5) | no/total (%) | 77/450 (44.2) | 114/568 (20.1) | 0.23 | – |

| ARDS | no/total (%) | 54/401 (13.5) | 83/536 (15.5) | 0.39 | 81 |

| APACHE II score | Median (IQR) | 22 (16–29) | 23 (17–30) | 0.11 | 108 |

| SOFA score | Median (IQR) | 8 (5–11) | 9 (6–12) | 0.009 | 160 |

Table 3 shows the sepsis care bundle, treatment, and outcome of study patients. The compliance rates for the entire 3-h bundle and each item of the 3-h bundle were higher in the closed ICU group than in the open ICU group. The compliance rate for the entire 3-h bundle was 71.3% in the closed ICU group and 54.8% in the open ICU group (P < .001). However, the compliance rate for the entire 6-h bundle was very low in both groups because the compliance rates for measurement of central venous pressure (CVP) and central venous oxygen saturation (ScvO2) were low. In contrast, compliance rates for vasopressor use and re-measurement of lactate in the 6-h bundle were high in both groups and the compliance rates were higher in the closed ICU group than in the open ICU group (88.8 vs. 81.5%, P = .001). Concerning mediations and interventions from diagnosis to within 72 h after diagnosis, the rates of noradrenaline, steroid, and recombinant human-soluble thrombomodulin use were higher in the closed ICU group than in the open ICU group. In contrast, the rates of protease inhibitor and sivelestat sodium use were lower in the closed ICU group than in the open ICU group. With regards to antibacterial drugs, the rates of carbapenem and anti-methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) drug use were higher in the closed ICU group than in the open ICU group. ICU-free days, ventilator-free days, and length of hospital stays were not significantly different between the two groups. The primary outcome, in-hospital mortality, was 25.0% in the closed ICU group and 23.1% in the open ICU and was not significantly different between the two groups (P = .48).

Table 3.

The sepsis care bundle, treatment, and outcome of study patients (n = 1018).

| Open ICU | Closed ICU | ||||

| n = 450 | n = 568 | P value | Missing | ||

| Sepsis care bundle | |||||

| Compliance with all applicable elements of sepsis 3-h resuscitation bundle | |||||

| Serum lactate obtained within 3-h of diagnosis of sepsis | no/total (%) | 426/449 (94.9) | 563/568 (99.1) | <0.001 | 1 |

| Broad-spectrum antibiotic given within 3-h of diagnosis of sepsis | no/total (%) | 357/448 (79.7) | 498/568 (87.7) | <0.001 | 2 |

| Blood cultures obtained before broad-spectrum antibiotic administration | no/total (%) | 388/447 (86.8) | 534/568 (94.0) | <0.001 | 3 |

| For hypotension or lactate concentration > 4 mmol/L, 30ml/kg crystalloid fluid bolus delivered within 3-h of diagnosis of sepsis | |||||

| Yes | no/total (%) | 192/444 (43.2) | 346/568 (60.9) | <0.001 | 6 |

| No | no/total (%) | 95/444 (21.4) | 88/568 (15.5) | ||

| Not indicated | no/total (%) | 157/444 (35.4) | 134/568 (23.6) | ||

| Entire 3-h bundle | no/total (%) | 246/449 (54.8) | 405/568 (71.3) | <0.001 | 1 |

| Compliance with all applicable elements of sepsis 6-h resuscitation bundle | |||||

| Vasopressors use followed initial fluid bolus if needed to maintain MAP ≧ 65 mmHg within 6-h of diagnosis of sepsis (yes/cases with indication) | |||||

| Yes | no/total (%) | 247/446 (55.4) | 391/568 (68.8) | <0.001 | 4 |

| No | no/total (%) | 35/446 (7.8) | 45/568 (7.9) | ||

| Not indicated | no/total (%) | 164/446 (36.8) | 132/568 (23.3) | ||

| Dopamine | no/total (%) | 43/247 (17.4) | 41/391 (10.5) | 0.01 | – |

| Dobutamine | no/total (%) | 18/247 (7.3) | 51/391 (13.0) | 0.02 | – |

| Noradrenaline | no/total (%) | 231/247 (93.5) | 374/391 (95.7) | 0.24 | – |

| For septic shock or lactate > 4 mmol/L, CVP measured within 6-h of diagnosis of sepsis (yes/cases with indication) | |||||

| Yes | no/total (%) | 64/446 (14.4) | 103/567 (18.2) | <0.001 | 5 |

| No | no/total (%) | 228/446 (51.1) | 330/567 (58.2) | ||

| Not indicated | no/total (%) | 154/446 (34.5) | 134/567 (23.6) | ||

| For septic shock or lactate > 4 mmol/L, ScvO2 measured within 6-h of diagnosis of sepsis (yes/cases with indication) | |||||

| Yes | no/total (%) | 24/446 (5.4) | 13/568 (2.3) | <0.001 | 4 |

| No | no/total (%) | 268/446 (60.1) | 420/568 (73.9) | ||

| Not indicated | no/total (%) | 154/446 (34.5) | 135/568 (23.8) | ||

| Re-measured lactate if initial lactate elevated | |||||

| Yes | no/total (%) | 309/446 (69.3) | 431/563 (76.6) | <0.001 | 9 |

| No | no/total (%) | 54/446 (12.1) | 21/563 (3.7) | ||

| Not indicated | no/total (%) | 83/446 (18.6) | 111/563 (19.7) | ||

| Entire 6-h bundle | no/total (%) | 16/358 (4.5) | 7/487 (1.4) | 0.007 | 173 |

| Vasopressors use and re-measured lactate in 6-h bundle | no/total (%) | 361/443 (81.5) | 500/563 (88.8) | 0.001 | 12 |

| Medications and interventions (from diagnosis to within 72 h after diagnosis) | |||||

| Time from diagnosis of sepsis to antibiotic use among patients who were given antibiotic within 3 h of diagnosis of sepsis | Median (IQR) | 80 (46–118) | 71 (34.0–118) | 0.15 | 5 |

| Noradrenaline | no/total (%) | 270/450 (60.0) | 403/567 (71.1) | <0.001 | 1 |

| Continuous renal replacement therapy | no/total (%) | 118/449 (26.3) | 159/565 (28.1) | 0.51 | 4 |

| Intermittent renal replacement therapy | no/total (%) | 14/447 (3.1) | 21/566 (3.7) | 0.62 | 5 |

| Polymyxin B Hemoperfusion | no/total (%) | 43/450 (9.6) | 41/567 (7.2) | 0.18 | 1 |

| Protease inhibitor (without sivelestat sodium) | no/total (%) | 66/446 (14.8) | 6/565 (1.1) | <0.001 | 7 |

| Sivelestat sodium | no/total (%) | 28/447 (6.3) | 8/566 (1.4) | <0.001 | 5 |

| Intravenous immunoglobulin | no/total (%) | 86/446 (19.3) | 117/564 (20.7) | 0.56 | 8 |

| Selective digestive decontamination | no/total (%) | 6/447 (1.3) | 3/564 (0.5) | 0.17 | 7 |

| Enteral nutrition | no/total (%) | 202/446 (45.3) | 276/565 (48.9) | 0.26 | 7 |

| Steroid | no/total (%) | 123/448 (27.5) | 196/564 (34.8) | 0.01 | 6 |

| Antithrombin | no/total (%) | 92/448 (20.5) | 125/566 (22.1) | 0.55 | 4 |

| Recombinant human soluble thrombomodulin | no/total (%) | 69/448 (15.4) | 144/564 (25.5) | <0.001 | 6 |

| Antibacterial and antifungal drug | |||||

| Sulbactam/Ampicillin | no/total (%) | 39/450 (8.7) | 25/568 (4.4) | 0.005 | – |

| Tazobactam/Piperacillin | no/total (%) | 101/450 (22.4) | 106/568 (18.7) | 0.14 | – |

| Ceftriaxone/Cefotaxime | no/total (%) | 43/450 (9.6) | 34/568 (6.0) | 0.03 | – |

| Carbapenem | no/total (%) | 199/450 (44.2) | 356/568 (62.7) | <0.001 | – |

| Vancomycin | no/total (%) | 63/450 (14.0) | 123/568 (21.7) | 0.002 | – |

| Anti MRSA drug except Vancomycin | no/total (%) | 15/450 (3.3) | 50/568 (8.8) | <0.001 | – |

| Antifungal drug | no/total (%) | 18/450 (4.0) | 28/568 (4.9) | 0.48 | – |

| ICU-free days | Median (IQR) | 19 (10–24) | 19 (10–24) | 0.48 | 204 |

| Ventilator-free days | Median (IQR) | 20 (0–28) | 21 (0–27) | 0.22 | 10 |

| Length of hospital stay | Median (IQR) | 23 (12–46) | 24 (12–45) | 0.82 | – |

| Hospital mortality | no/total (%) | 104/450 (23.1) | 142/568 (25.0) | 0.48 | – |

Table 4 displays the results of the multilevel logistic regression analysis for in-hospital mortality. The OR for in-hospital mortality between the two groups was not statistically significant (OR 0.83 [95% CI: 0.52–1.32] in closed ICU group, reference in open ICU group, P = .43). As a sensitivity analysis, in the propensity score matching analysis, in-hospital mortality between the two groups was not statistically significant (closed ICU group, 21.2%; open ICU group, 25.7%; P = .22) (Table 5, and see Table S1, Supplemental Digital Content, which illustrates the comparison for variables between open ICU and closed ICU groups after propensity score matching analysis).

Table 4.

. The multilevel logistic regression analysis for hospital mortality (n = 846).

| Variables | Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value |

| ICU model | ||

| Closed ICU (vs Open) | 0.83 (0.52–1.32) | .43 |

| Teaching facility | 0.68 (0.40–1.14) | .14 |

| ICU beds category | ||

| 1–10 | reference | – |

| 11–20 | 0.54 (0.33–0.91) | .02 |

| 21– | 0.49 (0.23–1.02) | .06 |

| ICU beds per certified intensivist | 1.03 (0.99–1.05) | .07 |

| Age (per year) | 1.02 (1.01–1.04) | .003 |

| Gender | ||

| male | 0.72 (0.49–1.04) | .08 |

| BMI (per single point) | 0.99 (0.96–1.03) | .69 |

| Admission source | ||

| Emergency Department | reference | – |

| Transfer or other departments | 2.36 (0.99–5.59) | .05 |

| ICU | 1.22 (0.81–1.83) | .33 |

| Charlson comorbidity index (per single point) | 1.20 (1.08–1.34) | <.001 |

| ADL | ||

| Dependent | 0.91 (0.58–1.42) | .67 |

| Suspect site of infection | ||

| Lung | reference | – |

| Abdomen | 0.50 (0.31–0.81) | .004 |

| Urinary tract | 0.22 (0.11–0.44) | <.001 |

| Blood stream infection/endocardium/Catheter/Implant device | 0.79 (0.32–1.96) | .61 |

| Central nerve system | 2.30 (0.72–7.35) | .16 |

| Osteoarticular | 0.97 (0.17–5.47) | .97 |

| Skin/soft tissue | 0.81 (0.42–1.54) | .52 |

| Wound | 0.94 (0.12–7.29) | .95 |

| Other | 1.28 (0.61–2.68) | .51 |

| Positive blood culture | 1.15 (0.79–1.69) | .46 |

| Septic shock | 0.97 (0.61–1.54) | .90 |

| SOFA score | 1.19 (1.13–1.26) | <.001 |

| Compliance rate for the entire 3-h bundle | 0.97 (0.65–1.45) | .89 |

Table 5.

. Primary outcome between open ICU and closed ICU.

| Open ICU | Closed ICU | P value | |

| Hospital mortality by univariate analysis (n = 1018)no/total (%) | 104/450 (23.1) | 142/568 (25.0) | .48 |

| Hospital mortality by Multilevel logistic regression analysis (n = 846)Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | 1.00 | 0.83 (0.52–1.32) | .43 |

| Hospital mortality by propensity score matching analysis (n = 538)no/total (%) | 69/269 (25.7) | 57/269 (21.2) | .22 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Key findings

This study demonstrates that patients in the closed ICU group had a higher severity score and had more incidences of organ failures than patients in the open ICU group. In addition, the closed ICU group had a higher compliance rate for the 3-h bundle than the open ICU group. In-hospital mortality was not significantly different between the closed ICU and the open ICU groups based on the multilevel logistic regression analysis and propensity score matching analysis.

4.2. Relationship to previous studies

Before and after studies and a meta-analysis comparing open and closed ICUs for patients with critical illnesses showed that in-hospital mortality in the closed ICU was lower than that in the open ICU.[3–6,13] A single-center retrospective observational study showed that in-hospital mortality decreased from 25.7% to 15.8% (P = .01) after shifting from the open ICU to the closed ICU.[6] In a meta-analysis, mortality was significantly higher in the open ICU than in the closed ICU (OR 1.31 [95% CI: 1.17–1.48] in open ICU, reference in closed ICU, P < .001).[13] In sepsis patients, a prospective cohort study in Asian ICUs reported that in-hospital mortality was not significantly different between patients cared for in the open ICU versus closed ICU setting (open ICU vs. closed ICU, 42.4% vs. 46.1%; P = .19).[8] A nationwide observational study in Japan showed that in-hospital mortality was significantly lower in the closed ICU than in the open ICU (OR 0.63 [95% CI: 0.55–0.78], P < .001).[7] The study explained that high-quality care, including a high compliance rate to the guidelines, contributed to the lower in-hospital mortality in the closed ICU although there was no data concerning guideline compliance rates.

As for ICU structures, a multicenter prospective observational study conducted in Korea showed that a nurse-to-patient ratio of 1:2 was significantly associated with a lower 28-day mortality (hazard ratio (HR) 0.46 [95% CI: 0.21–0.99], P = .049) but not with in-hospital mortality.[14] Concerning compliance with the 2012 SSCG guidelines, previous studies reported that compliance with the 3-h sepsis bundle and 6-h bundle was statistically associated with lower in-hospital mortality.[11,12,15] This study showed that in-hospital mortality was not significantly different in the closed ICU versus open ICU groups after adjusting for the ICU structure and sepsis care bundle compliance. The reason for the difference in our findings compared to previous studies may be due to the rates of compliance with the sepsis care bundle, which were higher in both the closed ICU and open ICU settings compared to previous studies. Moreover, only ICUs with a 1:2 nurse-to-patient ratio per shift were included. Otherwise, each attending physicians in the open ICU might have consulted appropriately with intensivists for sepsis practice. Also, the severity of sepsis among patients admitted to the ICU was high; therefore, patients might have died even if they were treated appropriately.

4.3. Significance and implications

This study showed that in-hospital mortality was not significantly different between the closed and open ICU groups. However, the odds ratio for in-hospital mortality of the closed ICU group was lower (but not significantly different) based on the multilevel logistic regression analysis and propensity score matching analysis. These findings imply that in-hospital mortality in the closed ICU might be better than that in the open ICU.

As for the ICU model, ICU admission, discharge, and triage guidelines revealed that a high-intensity ICU model is recommended.[16] A high-intensity ICU model is characterized by the intensivist being responsible for the day-to-day management of the patient, either in a closed ICU (the intensivist is the patient's primary attending physician) or mandatory critical care consultation (the intensivist is not the patient's primary attending physician, but every patient admitted to the ICU receives a critical care consultation).[16,17] Sufficient human resources are needed to manage a high-intensity ICU. However, there are not enough intensivists in Japan.[18] Hence, the effective utilization of intensivists is important. In low-intensity ICUs, the development of a system that facilitates effective consultation to only a few intensivists and treats patients with them is important. Furthermore, the few intensivists need to educate physicians and ICU nurses about the guidelines for managing critical patients.

4.4. Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, the open ICU and closed ICU settings were not clearly defined in the FORECAST study and each ICU subjectively reported information about their ICU model. Hence, a misclassification bias might have occurred. However, no fundamental definitions of ICU models have been established by any professional intensive care society. Second, this study included only 45 ICUs, which comprise only about one-seventh of the total tertiary emergency facilities in Japan. Thus, sampling bias may have occurred. Furthermore, all ICU structures and processes for the management of sepsis and septic shock could not be investigated. For the ICU structures, the detailed engagement of intensivists in patient treatment in the open ICU, the time coverage (24 h a day or not) of intensivists, and the presence of certified nurses, clinical engineers, and pharmacists were not evaluated. With respect to the process, the compliance to guidelines, such as the ABCDEF bundle[19] and ventilator-associated pneumonia bundle,[20] which might be associated with the prognosis of patients with sepsis and septic shock were not assessed. These factors might have affected the outcomes of this study.

5. Conclusions

This secondary analysis of a multicenter prospective observational study on sepsis in Japan showed that the in-hospital mortality was not statistically different in the closed ICU versus open ICU setting after adjusting for different structure and process elements associated with the management of sepsis. To improve sepsis prognosis, the optimal structure and process for the management of sepsis and septic shock should be explored.

Acknowledgments

We thank the JAAM FORECAST Study Group for their contribution to this study (JAAM FORECAST Study group e-mail address: jaam-6@bz04.plala.or.jp). Investigators of the JAAM FORECAST Study Group: Nagasaki University Hospital (Osamu Tasaki); Osaka City University Hospital (Yasumitsu Mizobata); Tokyobay Urayasu Ichikawa Medical Center (Hiraku Funakoshi); Aso Iizuka Hospital (Toshiro Okuyama); Tomei Atsugi Hospital (Iwao Yamashita); Hiratsuka City Hospital (Toshio Kanai); National Hospital Organization Sendai Medical Center (Yasuo Yamada); Ehime University Hospital (Mayuki Aibiki); Okayama University Hospital (Keiji Sato); Tokuyama Central Hospital (Susumu Yamashita); Fukuyama City Hospital (Susumu Yamashita); JA Hiroshima General Hospital (Kenichi Yoshida); Kumamoto University Hospital (Shunji Kasaoka); Hachinohe City Hospital (Akihide Kon); Osaka City General Hospital (Hiroshi Rinka); National Hospital Organization Disaster Medical Center (Hiroshi Kato); University of Toyama (Hiroshi Okudera); Sapporo Medical University (Eichi Narimatsu); Okayama Saiseikai General Hospital (Toshifumi Fujiwara); Juntendo University Nerima Hospital (Manabu Sugita); National Hospital Organization Hokkaido Medical Center (Yasuo Shichinohe); Akita University Hospital (Hajime Nakae); Japanese Red Cross Society Kyoto Daini Hospital (Ryouji Iiduka); Maebashi Red Cross Hospital (Mitsunobu Nakamura); Sendai City Hospital (Yuji Murata); Subaru Health Insurance Society Ota Memorial Hospital (Yoshitake Sato); Fukuoka University Hospital (Hiroyasu Ishikura); Ishikawa Prefectural Central Hospital (Yasuhiro Myojo); Shiga University of Medical Science (Yasuyuki Tsujita); Nihon University School of Medicine (Kosaku Kinoshita); Seirei Yokohama General Hospital (Hiroyuki Yamaguchi); National Hospital Organization Kumamoto Medical Center (Toshihiro Sakurai); Saiseikai Utsunomiya Hospital (Satoru Miyatake); National Hospital Organization Higashi-Ohmi General Medical Center (Takao Saotome); National Hospital Organization Mito Medical Center (Susumu Yasuda); Tsukuba Medical Center Hospital (Toshikazu Abe); Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine (Hiroshi Ogura, Yutaka Umemura); Kameda Medical Center (Atsushi Shiraishi); Tohoku University Graduate School of Medicine (Shigeki Kushimoto); National Defense Medical College (Daizoh Saitoh); Keio University School of Medicine (Seitaro Fujishima, Junichi Sasaki); University of Occupational and Environmental Health (Toshihiko Mayumi); Kawasaki Medical School (Yasukazu Shiino); Chiba University Graduate School of Medicine (Taka-aki Nakada); Kyorin University School of Medicine (Takehiko Tarui); Kagawa University Hospital (Toru Hifumi); Tokyo Medical and Dental University (Yasuhiro Otomo); Hyogo College of Medicine (Joji Kotani); Saga University Hospital (Yuichiro Sakamoto); Aizu Chuo Hospital (Shin-ichiro Shiraishi); Kawasaki Municipal Kawasaki Hospital (Kiyotsugu Takuma); Yamaguchi University Hospital (Ryosuke Tsuruta); Center Hospital of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (Akiyoshi Hagiwara); Osaka General Medical Center (Kazuma Yamakawa); Aichi Medical University Hospital (Naoshi Takeyama); Kurume University Hospital (Norio Yamashita); Teikyo University School of Medicine (Hiroto Ikeda); Rinku General Medical Center (Yasuaki Mizushima); Hokkaido University Graduate School of Medicine (Satoshi Gando). Furthermore, the authors would like to thank Enago (www.enago.jp) for the language review.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Isao Nagata, Toshikazu Abe.

Data curation: Isao Nagata.

Formal analysis: Isao Nagata, Toshikazu Abe.

Investigation: Isao Nagata, Toshikazu Abe.

Methodology: Isao Nagata, Toshikazu Abe.

Writing – original draft: Isao Nagata, Toshikazu Abe.

Writing – review & editing: Toshikazu Abe, Hiroshi Ogura, Shigeki Kushimoto, Seitaro Fujishima, Satoshi Gando.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ADL = activities of daily living, CI = confidence interval, CVP = central venous pressure, FIO2 = fraction of inspired oxygen, FORECAST = Focused Outcomes Research in Emergency Care in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome, Sepsis, and Trauma, HR = hazard ratio, ICU = intensive care unit, IQR = interquartile range, LOS = length of hospital stay, MAP = mean arterial pressure, MRSA = methicillin resistant staphylococcus aureus, OR = odds ratio, PaO2 = partial pressure of arterial oxygen, ScvO2 = central venous oxygen saturation, SOFA = sepsis-related organ failure assessment, SSCG = Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines, VFD = ventilator-free days.

How to cite this article: Nagata I, Abe T, Ogura H, Kushimoto S, Fujishima S, Gando S. Intensive care unit model and in-hospital mortality among patients with severe sepsis and septic shock: A secondary analysis of a multicenter prospective observational study. Medicine. 2021;100:21(e26132).

The authors have no funding to disclose.

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Availability of data and materials: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee of all participant institutes in the Japanese Association for Acute Medicine (JAAM) study group, Japan. (IRB number 014–0306 on Hokkaido University, the representative for FORECAST).

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the present study are not publicly available, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article.

ICU = intensive care unit, IQR = interquartile range.

ADL = Activities of daily living, APACHE = Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation, BMI = body mass index, ICU = intensive care unit, IQR = interquartile range, PT-INR = Prothrombin Time-International Normalized Ratio, SOFA = Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment.

CVP = central venous pressure, ICU = intensive care unit, IQR = interquartile range, ScvO2 = Central venous oxygen saturation.

ADL = Activities of daily living, BMI = body mass index, CI = confidence interval, ICU = intensive care unit, SOFA = Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment.

ICU = intensive care unit.

References

- [1].Sakr Y, Jaschinski U, Wittebole X, et al. Sepsis in intensive care unit patients: worldwide data from the intensive care over nations audit. Open Forum Infect Dis 2018;5:ofy313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q 1966;44:166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Carson SS, Stocking C, Podsadecki T, et al. Effects of organizational change in the medical intensive care unit of a teaching hospital: a comparison of ’open’ and ’closed’ formats. JAMA 1996;276:322–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chittawatanarat K, Pamorsinlapathum T. The impact of closed ICU model on mortality in general surgical intensive care unit. J Med Assoc Thai 2009;92:1627–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hackner D, Shufelt CL, Balfe DD, Lewis MI, Elsayegh A, Braunstein GD. Do faculty intensivists have better outcomes when caring for patients directly in a closed ICU versus consulting in an open ICU? Hosp Pract 2009;37:40–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].van der Sluis FJ, Slagt C, Liebman B, et al. The impact of open versus closed format ICU admission practices on the outcome of high risk surgical patients: a cohort analysis. BMC Surg 2011;11:18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Ogura T, Nakamura Y, Takahashi K, Nishida K, Kobashi D, Matsui S. Treatment of patients with sepsis in a closed intensive care unit is associated with improved survival: a nationwide observational study in Japan. J Intensive Care 2018;6:57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Phua J, Koh Y, Du B, et al. Management of severe sepsis in patients admitted to Asian intensive care units: prospective cohort study. BMJ 2011;342:d3245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med 2003;31:1250–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Abe T, Ogura H, Shiraishi A, et al. Characteristics, management, and in-hospital mortality among patients with severe sepsis in intensive care units in Japan: the FORECAST study. Crit Care 2018;22:322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Rhodes A, Phillips G, Beale R, et al. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign bundles and outcome: results from the International Multicentre Prevalence Study on Sepsis (the IMPreSS study). Intensive Care Med 2015;41:1620–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Prasad PA, Shea ER, Shiboski S, Sullivan MC, Gonzales R, Shimabukuro D. Relationship between a sepsis intervention bundle and in-hospital mortality among hospitalized patients: a retrospective analysis of real-world data. Anesth Analg 2017;125:507–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yang Q, Du JL, Shao F. Mortality rate and other clinical features observed in open vs closed format intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine 2019;98:e16261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kim JH, Hong SK, Kim KC, et al. Influence of full-time intensivist and the nurse-to-patient ratio on the implementation of severe sepsis bundles in Korean intensive care units. J Crit Care 2012;27:414.e411–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Leisman DE, Doerfler ME, Ward MF, et al. Survival benefit and cost savings from compliance with a simplified 3-hour sepsis bundle in a series of prospective, multisite, observational cohorts. Crit Care Med 2017;45:395–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Nates JL, Nunnally M, Kleinpell R, et al. ICU admission, discharge, and triage guidelines: a framework to enhance clinical operations, development of institutional policies, and further research. Crit Care Med 2016;44:1553–602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Pronovost PJ, Angus DC, Dorman T, et al. Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: a systematic review. JAMA 2002;288:2151–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Committee on ICU Evaluation JSoICM. The Health Labour Science Research group for “DPC”, the Ministry of Health, Labour, and, Welfare., influence of staffing and administrative policy of, ICU., on patient, outcome. J Jpn Soc Intensive Care Med 2011;18:283–94. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ely EW. The ABCDEF bundle: science and philosophy of how ICU liberation serves patients and families. Crit Care Med 2017;45:321–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].McCannon CJ, Schall MW, Calkins DR, et al. Saving 100,000 lives in US hospitals. BMJ 2006;332:1328–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.