Abstract

This study aimed to evaluate the prevalence of low health literacy in Hebei Province of China, and to investigate its socio-demographic risk factors.

This study was a community-based, cross-sectional questionnaire survey with a multiple-stage randomization design and a sample size of 10,560. Participants’ health literacy status was evaluated by a questionnaire based on the 2012 Chinese Resident Health Literacy Scale. Meanwhile, participants’ socio-demographic characteristics were also collected by the questionnaire.

A total of 9952 participants provided valid questionnaires and were included in the final analyses. The mean health literacy score was 63.1 ± 17.1 points; for its subscales, the mean basic knowledge and concepts score, lifestyle score, health-related skills score were 31.7 ± 9.0, 17.2 ± 4.8, 14.3 ± 4.1, respectively. Meanwhile, low health literacy prevalence was 81.0%; for its subscales, low basic knowledge and concepts prevalence (70.6%) was numerically reduced compared to low lifestyle prevalence (87.4%) and low health-related skills prevalence (86.1%). Further analyses showed that age, male, and rural area were positively associated, but education level and annual household income were negatively associated with low health literacy prevalence. Further multivariate logistic regression analyses showed that higher age, male, lower education level, lower annual household income, and rural area were closely correlated with the risks of low total health literacy or low health literacy in subscales in Hebei Province.

The prevalence of low health literacy is 81.0% in Hebei Province. Meanwhile, higher age, male, lower education level, lower annual household income, and rural area closely associate with low health literacy risk.

Keywords: China, health literacy, Hebei Province, risk factors, socio-demographic

1. Introduction

Health literacy is an emerging concept defined as “the cognitive and social skills which determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health” by the World Health Organization.[9] According to previous studies, low health literacy is closely correlated with an individual's worse self-management, inferior health status, more hospitalization and medical costs, which greatly influences his/her quality of life.[11,16] Moreover, since health literacy clearly reflects public health education and deeply affects health resource utilization, it has become a crucial public health concern and has raised extensive attention in the past few years.[1,3] Besides, the information on local low health literacy prevalence is critical for local government to formulate policy and to allocate resources.[3]

Although health literacy overview in several western countries has been reported by previous studies, the health literacy status among Chinese citizens is still far from clear.[8,17] According to the latest national survey of health literacy status among Chinese citizens in 2012, 91.2% of Chinese residents are of low health literacy.[10] However, given the imbalanced development among different regions of China, local health literacy status in different regions could vary greatly.[18,24] Indeed, 1 previous study illustrates that the prevalence of low health literacy status in Jiangsu Province is 47.5%, and another study reveals that the prevalence of inadequate health literacy status in Beijing is 59%; however, the cut-off of low health literacy differed a lot among different studies.[19,22] Therefore, it is critical to perform survey that acquires the local health status to help the local government polishing relevant policies and improve the overall health status of local residents.[2,12]

Hebei Province is a big inland province located in north China with a permanent resident population of 75.92 million. Typically, Hebei Province is considered as the representative regarding economy and culture of northern China.[23] However, the local low health literacy prevalence of Hebei province is not clear. Therefore, the aim of this study was to investigate health literacy in Hebei Province, and to explore its socio-demographic risk factors.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

This study was carried out in Hebei Province of China, where there were 75.92 million permanent residents in 2019. The study was conducted between January 2019 and December 2019, and a total of 10,560 residents in Hebei Province participated in this cross-sectional survey. All study populations were permanent residents with age between 16 and 75 years in Hebei Province, where the permanent resident was defined as the resident who had lived in the Hebei Province for more than 12 months, regardless of whether they had a local household registration or not. While the residents who collectively resided in military bases, hospitals, prisons, nursing homes, or dormitories, were not included in the study. This study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Hebei Provincial Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. All participants signed informed consents.

2.2. Sample size estimation

A multistage, stratified sampling method was used to select the study population. The core stratification factors included area (urban and rural), age (16–35 years, 36–55 years, 56–75 years), and gender (male and female). In each stratification, the sample size was calculated estimated using the formula[20]: , where the parameters were set as follows: prevalence P = .89 (based on national health literacy survey results, available at: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/), maximum permissible error δ = 0.1p, significance level α = 0.05, Z1-α/2 = 1.96, the design effect of complex sampling deff = 1.5, the required sample size in each stratification was N = 71.22. Considering a refusal rate of 10%, the actual sample size was increased to 71.22/0.9 = 79.13, rounded to 80. There were 11 province-governed municipalities in Hebei Province, as a result, the total sample size of this study was calculated as: N = 80 × 11 (municipalities) × 2 (area stratifications) × 3 (age stratifications) × 2 (gender stratifications) = 10,560.

2.3. Sampling procedures

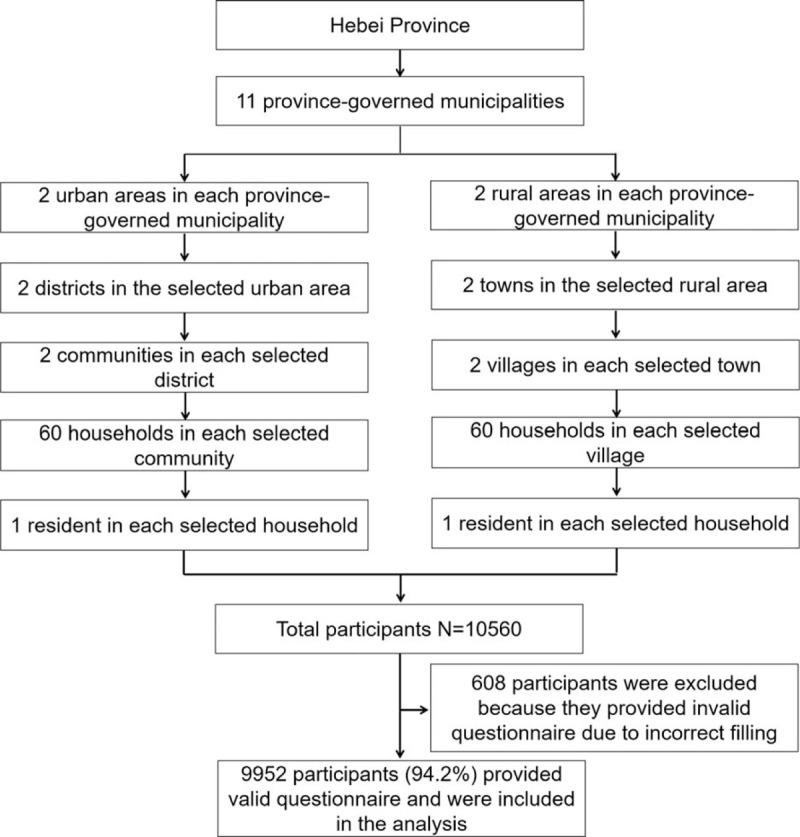

As shown in Figure 1, 2 urban areas and 2 rural areas in each province-governed municipality were randomly selected using Probability Proportionate to Size (PPS) sampling. In each chosen urban area, 2 districts were randomly selected with PPS sampling, then 2 communities were randomly selected with PPS sampling from each chosen district; next, 60 registered households were randomly selected from each chosen community using random number table, and 1 resident was selected from each chosen household with the use of Kish method. In each chosen rural area, 2 towns were randomly selected with PPS sampling, then 2 villages were randomly selected with PPS sampling from each chosen town; next, 60 registered households were randomly selected from each chosen village using random number table, and 1 resident was selected from each chosen household with the use of Kish method. As a result, 960 residents in each province-governed municipality were selected, and there were 11 province-governed municipalities in Hebei, resulting in total 10,560 residents were sampled. Finally, 608 participants were excluded from analysis because they provided invalid questionnaires due to incorrect filling, then 9952 participants (94.2%) provided valid questionnaires and were included in analysis.

Figure 1.

Study sampling process.

2.4. Data collection

A questionnaire was created for this study, and it consisted of 2 parts: part 1 was designed to collect participants’ socio-demographic characteristics including age, gender, education level, annual household income, and location; part 2 was the 2012 Chinese Resident Health Literacy Scale derived from the manual of “Chinese Resident Health Literacy-Basic Knowledge and Skills (trial edition)” published by the Chinese Ministry of Health in 2008[4] The questionnaire was completed by the participants themselves. If the participants were unable to fulfill the questionnaire independently due to low literacy level, the face-to-face interview method was adopted, during which the investigators were allowed to make appropriate explanations without the use of inductive or suggestive expression.

2.5. Health literacy evaluation

The 2012 Chinese Resident Health Literacy Scale comprised of 80 questions including 38 questions about basic knowledge and concepts, 22 questions about lifestyle, and 20 questions about health-related skills.[10] There were 4 types of questions in the scale: 15 true-or-false questions, 40 single-answer questions, 18 multiple-answer questions and 7 situation questions (including 5 single-answer questions and 2 multiple-answer questions). For true-or-false and single-answer questions, 1 point was assigned for a correct answer, and 0 points were assigned for an incorrect answer. For multiple-answer questions, 2 points were assigned if the response contained all correct answers without the wrong ones, and 0 points were given to wrong or omitted answers. The total basic knowledge and concepts score was 47 points, the total lifestyle score was 28 points, and the total health-related skills score was 25 points. The total health literacy score was the sum of the 3 scores, which was ranging from 0 to 100 points. Low health literacy was defined as the total health literacy score <80 points (80% of total health literacy score, which was in accordance with previous studies).[10,20] Low health literacy of basic knowledge and concepts was defined as the total basic knowledge and concepts score <38 points (which was 80% of total basic knowledge and concepts score). Low health literacy of lifestyle was defined as the total lifestyle score <23 points (which was 80% of total lifestyle score). Low health literacy of health-related skills was defined as the total health-related skills score <20 points (which was 80% of health-related skills score).

2.6. Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 24.0 (IBM, Chicago, IL), and figures were plotted using GraphPad Prism 8.01 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA). Socio-demographic characteristics and low health literacy prevalence were described as number and percentage. The distribution of total health literacy score was displayed by histogram, and the detailed scores including total health literacy score, basic knowledge and concepts score, lifestyle score, and health-related skills score, were described by mean with standard deviation (SD). Comparison of health literacy scores among subjects with different characteristics was determined by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Student t test. Comparison of low health literacy prevalence among subjects with different characteristics was determined by the Chi-Squared test. Factors related to low health literacy risk were analyzed by the univariate and forward stepwise multivariate logistic regression model. P value <.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Description of the participants’ characteristics

Among the 9952 analyzed participants, 3329 (33.5%) of them were 16 to 35 years old, 3327 (33.4%) of them were 36 to 55 years old, and 3296 (33.1%) of them were 56 to 75 years old. Meanwhile, there were 4887 (49.1%) females and 5056 (50.9%) males. As to education level, 2641 (26.5%) participants had primary school education level or below, 4011 (40.3%) participants had junior high school education level, 2180 (21.9%) participants had high school education level, and 1120 (11.3%) participants had university education level or above. Regarding annual household income, 818 (8.2%) participants had income below ¥10000, 5085 (51.1%) participants had income between ¥10,000 to¥29,999, 2470 (24.8%) participants had income between ¥30,000 to ¥49,999, and 1579 (15.9%) participants had income equal to or greater than ¥50000. As to resident location, 4883 (49.1%) participants were from rural area and 5069 (50.9%) participants were from urban area (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics.

| Characteristics | Participants (N = 9952) |

| Age, No. (%) | |

| 16–35 yr | 3329 (33.5) |

| 36–55 yr | 3327 (33.4) |

| 56–75 yr | 3296 (33.1) |

| Gender, No. (%) | |

| Female | 4887 (49.1) |

| Male | 5056 (50.9) |

| Education level, No. (%) | |

| Primary school or below | 2641 (26.5) |

| Junior high school | 4011 (40.3) |

| High school | 2180 (21.9) |

| University or above | 1120 (11.3) |

| Annual household income, No. (%) | |

| <¥10000 | 818 (8.2) |

| ¥10,000–¥29,999 | 5085 (51.1) |

| ¥30,000–¥49,999 | 2470 (24.8) |

| ≥¥50,000 | 1579 (15.9) |

| Location, No. (%) | |

| Rural | 4883 (49.1) |

| Urban | 5069 (50.9) |

3.2. Health literacy status

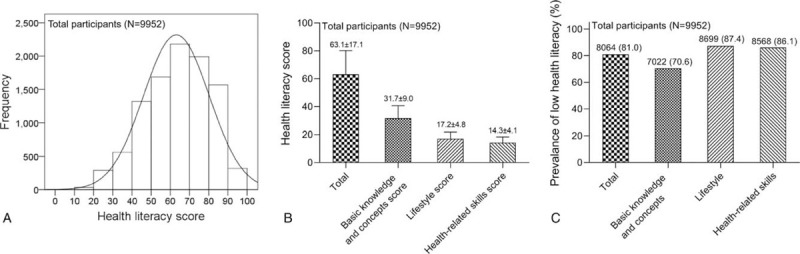

The health literacy score distribution of all participants was shown in Figure 2A. Specifically, there were 58 (0.6%) patients with score 10 to 20, 346 (3.5%) participants with score 21 to 30, 668 (6.7%) participants with score 31 to 40, 1287 (12.9%) participants with score 41 to 50, 1754 (17.6%) participants with score 51 to 60, 2154 (21.7%) participants with score 61 to 70, 1935 (19.4%) participants with score 71 to 80, 1474 (14.8%) participants with score 81 to 90, and 276 (2.8%) participants with score 91 to 100 (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Health literacy status in Hebei Province. A: The health literacy score distribution of all participants; B: The mean total health literacy score, basic knowledge and concepts score, lifestyle score, and health-related skills score; C: The prevalence of participants with low health literacy, as well as low health literacy in basic knowledge and concepts, health lifestyle and health-related skills.

Meanwhile, the mean total health literacy score was 63.1 ± 17.1 points. As to subscales, the mean basic knowledge and concepts score was 31.7 ± 9.0 points, the mean lifestyle score was 17.2 ± 4.8 points, and the mean health-related skills score was 14.3 ± 4.1 points (Fig. 2B). Besides, the prevalence of total low health literacy was 81.0% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 80.1%–81.6%). The subscale analyses further revealed that the prevalence of low basic knowledge and concepts was 70.6% (95% CI: 69.5%–71.7%), the prevalence of low lifestyle was 87.4% (95% CI: 86.7%–88.1%), and the prevalence of low health-related skills was 86.1% (95% CI: 85.4%–86.8%) (Fig. 2C).

3.3. Correlation analysis between participants’ characteristics and low health literacy

As respect to health literacy score, age was negatively correlated, while female, education level, annual household income and resident in urban area were positively correlated with total health literacy score, as well as its subscales including basic knowledge and concepts score, lifestyle score and health-related skills score (all P < .001) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlation of participants’ characteristics with health literacy score.

| Total health literacy score | Basic knowledge and concepts score | Lifestyle score | Health-related skills score | |||||

| Characteristics | Mean ± SD | P value | Mean ± SD | P value | Mean ± SD | P value | Mean ± SD | P value |

| Age | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| 16–35 yr | 66.6 ± 16.1 | 33.3 ± 8.4 | 18.1 ± 4.6 | 15.1 ± 4.0 | ||||

| 36–55 yr | 63.4 ± 16.9 | 31.9 ± 8.8 | 17.2 ± 4.7 | 14.4 ± 4.0 | ||||

| 56–75 yr | 59.4 ± 17.6 | 29.8 ± 9.3 | 16.1 ± 4.9 | 13.4 ± 4.1 | ||||

| Gender | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| Female | 66.2 ± 15.9 | 33.2 ± 8.3 | 18.0 ± 4.5 | 15.0 ± 3.9 | ||||

| Male | 60.2 ± 17.7 | 30.2 ± 9.3 | 16.3 ± 4.9 | 13.6 ± 4.2 | ||||

| Education level | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| Primary school or below | 54.0 ± 17.8 | 27.1 ± 9.4 | 14.7 ± 4.9 | 12.2 ± 4.0 | ||||

| Junior high school | 63.0 ± 16.2 | 31.6 ± 8.5 | 17.1 ± 4.6 | 14.3 ± 3.9 | ||||

| High school | 69.2 ± 14.2 | 34.7 ± 7.5 | 18.8 ± 4.1 | 15.7 ± 3.5 | ||||

| University or above | 73.1 ± 12.9 | 36.7 ± 6.7 | 19.8 ± 3.7 | 16.6 ± 3.5 | ||||

| Annual household income | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| <¥10,000 | 52.6 ± 17.6 | 26.3 ± 9.2 | 14.3 ± 5.0 | 11.9 ± 4.0 | ||||

| ¥10,000–¥29,999 | 59.9 ± 17.2 | 30.0 ± 9.0 | 16.3 ± 4.8 | 13.6 ± 4.0 | ||||

| ¥30,000–¥49,999 | 67.6 ± 15.2 | 34.0 ± 8.0 | 18.3 ± 4.4 | 15.3 ± 3.7 | ||||

| ≥¥50,000 | 71.8 ± 13.1 | 36.1 ± 6.8 | 19.5 ± 3.8 | 16.3 ± 3.5 | ||||

| Location | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| Rural | 58.3 ± 17.5 | 29.2 ± 9.2 | 15.9 ± 4.9 | 13.2 ± 4.1 | ||||

| Urban | 67.7 ± 15.4 | 34.0 ± 8.1 | 18.4 ± 4.4 | 15.4 ± 3.8 | ||||

Regarding low health literacy prevalence, age was positively associated, but female, education level, annual household income and resident in urban area were negatively associated with low total health literacy prevalence, as well as its subscales low basic knowledge and concepts prevalence, low lifestyle prevalence and low health-related skills prevalence (all P < .001) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlation of participants’ characteristics with low health literacy prevalence.

| Low health literacy | ||||||||

| Characteristics | Total | P value | Basic knowledge and concepts | P value | Lifestyle | P value | Health-related skills | P value |

| Age, No. (%) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| 16–35 yr | 2507 (75.3) | 2140 (64.3) | 2776 (83.4) | 2716 (81.6) | ||||

| 36–55 yr | 2694 (81.0) | 2336 (70.2) | 2907 (87.4) | 2848 (85.6) | ||||

| 56–75 yr | 2863 (86.9) | 2546 (77.2) | 3016 (91.5) | 3004 (91.1) | ||||

| Gender, No. (%) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| Female | 3836 (78.5) | 3199 (65.5) | 4160 (85.1) | 4082 (83.5) | ||||

| Male | 4228 (83.5) | 3823 (75.5) | 4539 (89.6) | 4486 (88.6) | ||||

| Education level, No. (%) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| Primary school or below | 2395 (90.7) | 2278 (86.3) | 2502 (94.7) | 2499 (94.6) | ||||

| Junior high school | 3311 (82.5) | 2843 (70.9) | 3535 (88.1) | 3478 (86.7) | ||||

| High school | 1592 (73.0) | 1313 (60.2) | 1803 (82.7) | 1772 (81.3) | ||||

| University or above | 766 (68.4) | 588 (52.5) | 859 (76.7) | 819 (73.1) | ||||

| Annual household income, No. (%) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| <¥10,000 | 752 (91.9) | 723 (88.4) | 768 (93.9) | 784 (95.8) | ||||

| ¥10,000–¥29,999 | 4355 (85.6) | 3917 (77.0) | 4615 (90.8) | 4553 (89.5) | ||||

| ¥30,000–¥49,999 | 1827 (74.0) | 1503 (60.9) | 2065 (83.6) | 2025 (82.0) | ||||

| ≥¥50,000 | 1130 (71.6) | 879 (55.7) | 1251 (79.2) | 1206 (76.4) | ||||

| Location, No. (%) | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | <.001 | ||||

| Rural | 4248 (87.0) | 3882 (79.5) | 4464 (91.4) | 4446 (91.1) | ||||

| Urban | 3816 (75.3) | 3140 (61.9) | 4235 (83.5) | 4122 (81.3) | ||||

3.4. Risk factors related to low health literacy

Higher age (36–55 years vs 16–35 years, P < .001; 56–75 years vs 16–35 years, P < .001), male (male vs female, P < .001), lower education level (high school vs university or above, P = .005; junior high school vs university or above, P < .001; primary school or below vs university or above, P < .001), lower annual household income (¥30,000–¥49,999 vs ≥¥50,000, P = .093; ¥10,000–¥29,999 vs ≥¥50,000, P < .001; <¥10,000 vs ≥¥50,000, P < .001) and rural location (rural vs urban, P < .001) were risk factors for low health literacy. Further multivariate logistic regression showed that higher age (36–55 years vs 16–35 years, P < .001; 56–75 years vs 16–35 years, P < .001), lower annual household income (¥30,000–¥49,999 vs ≥¥50,000, P = .089; ¥10,000–¥29,999 vs ≥¥50,000, P < .001; <¥10,000 vs ≥¥50,000, P < .001) and rural location (rural vs urban, P < .001) were independent risk factors for low health literacy (Table 4).

Table 4.

Factors related to low health literacy risk.

| Logistic regression model | ||||

| Items | P value | OR | 95%CI | |

| Lower | Higher | |||

| Univariate logistic regression | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 16–35 yr | Reference | – | – | – |

| 36–55 yr | <.001 | 1.395 | 1.241 | 1.569 |

| 56–75 yr | <.001 | 2.168 | 1.907 | 2.464 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | Reference | – | – | – |

| Male | <.001 | 1.384 | 1.251 | 1.531 |

| Education level | ||||

| University or above | Reference | – | – | – |

| High school | .005 | 1.251 | 1.069 | 1.465 |

| Junior high school | <.001 | 2.186 | 1.881 | 2.540 |

| Primary school or below | <.001 | 4.499 | 3.751 | 5.397 |

| Annual household income | ||||

| ≥¥50000 | Reference | – | – | – |

| ¥30,000–¥49,999 | .093 | 1.129 | 0.980 | 1.301 |

| ¥10,000–¥29,999 | <.001 | 2.370 | 2.072 | 2.712 |

| <¥10000 | <.001 | 4.527 | 3.441 | 5.956 |

| Location | ||||

| Urban | Reference | – | – | – |

| Rural | <.001 | 2.197 | 1.978 | 2.440 |

| Forward stepwise multivariate logistic regression | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 16–35 yr | Reference | – | – | – |

| 36–55 yr | <.001 | 1.442 | 1.279 | 1.625 |

| 56–75 yr | <.001 | 2.373 | 2.082 | 2.706 |

| Annual household income | ||||

| ≥¥50,000 | Reference | – | – | – |

| ¥30,000–¥49,999 | .089 | 1.132 | 0.981 | 1.307 |

| ¥10,000–¥29,999 | <.001 | 2.066 | 1.722 | 2.480 |

| <¥10,000 | <.001 | 4.768 | 3.458 | 6.574 |

| Location | ||||

| Urban | Reference | – | – | – |

| Rural | .043 | 1.187 | 1.005 | 1.402 |

3.5. Analyses of risk factors for low health literacy in basic knowledge and concepts, health lifestyle and health-related skills

Additionally, we had investigated the independent risk factors for low health literacy in subscales, which was shown in Table 5. Briefly, higher age, male, lower education level, lower annual household income and rural area were independent risk factors for low basic knowledge and concepts (all P < .05). Meanwhile, higher age, lower education level and rural area were independent risk factors for low lifestyle (all P < .05). Furthermore, higher age, lower education level, lower annual household income and rural area were independent risk factors for low health-related skills (all P < .05) (Table 5).

Table 5.

Independent factors related to the risk of low health literacy in basic knowledge and concepts, health lifestyle and health-related skills.

| Forward stepwise multivariate logistic regression | ||||

| Items | P value | OR | 95%CI | |

| Lower | Higher | |||

| Low health literacy of basic knowledge and concepts | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 16–35 years | Reference | – | – | – |

| 36–55 yr | <.001 | 1.304 | 1.165 | 1.460 |

| 56–75 yr | <.001 | 1.809 | 1.552 | 2.107 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | Reference | – | – | – |

| Male | .004 | 1.186 | 1.054 | 1.335 |

| Education level | ||||

| University or above | Reference | – | – | – |

| High school | .697 | 1.047 | 0.830 | 1.322 |

| Junior high school | .634 | 1.076 | 0.796 | 1.453 |

| Primary school or below | .021 | 1.583 | 1.072 | 2.336 |

| Annual household income | ||||

| ≥¥50,000 | Reference | – | – | – |

| ¥30,000–¥49,999 | .449 | 1.090 | 0.872 | 1.364 |

| ¥10,000–¥29,999 | .001 | 1.658 | 1.232 | 2.232 |

| <¥10,000 | <.001 | 2.913 | 1.856 | 4.570 |

| Location | ||||

| Urban | Reference | – | – | – |

| Rural | <.001 | 1.356 | 1.164 | 1.581 |

| Low health literacy of lifestyle | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 16–35 yr | Reference | - | - | - |

| 36–55 yr | .001 | 1.260 | 1.094 | 1.451 |

| 56–75 yr | <.001 | 1.592 | 1.350 | 1.877 |

| Education level | ||||

| University or above | Reference | - | - | - |

| High school | .001 | 1.345 | 1.122 | 1.614 |

| Junior high school | <.001 | 1.776 | 1.472 | 2.142 |

| Primary school or below | <.001 | 3.559 | 2.729 | 4.641 |

| Location | ||||

| Urban | Reference | - | - | - |

| Rural | <.001 | 1.376 | 1.184 | 1.601 |

| Low health literacy of health-related skills | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 16–35 yr | Reference | - | - | - |

| 36–55 yr | <.001 | 1.320 | 1.148 | 1.519 |

| 56–75 yr | <.001 | 2.196 | 1.799 | 2.681 |

| Education level | ||||

| University or above | Reference | – | – | – |

| High school | .383 | 1.140 | 0.850 | 1.528 |

| Junior high school | .419 | 1.165 | 0.805 | 1.686 |

| Primary school or below | .023 | 1.746 | 1.081 | 2.821 |

| Annual household income | ||||

| ≥¥50,000 | Reference | – | – | – |

| ¥30,000–¥49,999 | .101 | 1.274 | 0.954 | 1.700 |

| ¥10,000–¥29,999 | .005 | 1.735 | 1.180 | 2.552 |

| <¥10,000 | <.001 | 3.997 | 2.138 | 7.473 |

| Location | ||||

| Urban | Reference | – | – | – |

| Rural | .007 | 1.299 | 1.073 | 1.571 |

4. Discussion

This study was the first to explore the health literacy prevalence and its socio-demographic risk factors in Hebei Province, China to the best of our knowledge. Meanwhile, this study was province-based and had a relatively large sample size, which might assist the local health care workers and government to better understand the health literacy status in Hebei Province. In this study, we found that the mean total health literacy score was 63.1 ± 17.1 points, and the prevalence of low health literacy was 81.0%. Meanwhile, higher age, male, lower annual household income, lower education level and rural area were closely correlated with low health literacy or its subscales.

Health literacy critically reflects an individual's comprehensive ability in coping with health problems under different circumstances.[11] Previous studies showed that patients with low health literacy have worse outcomes and occupy more public health resource; they might have poor health status and are more likely to be hospitalized[18,24]; meanwhile, they may not fully understand the medical system and treatment strategies, and might be unable to follow the instructions to take medicines appropriately, which often leads to the increased occupation of public health resource.[13] Therefore, understanding the prevalence of local low health literacy could enable local government to make policies and allocate resources.[1,3]

Due to the differences in the cut-off of low health literacy, the prevalence of low health literacy varies in different studies.[19,20,22] In order to achieve a comprehensive evaluation, we adopted the standard of low health literacy published by the Chinese Ministry of Health in 2012,[10] which showed strong psychometric properties with minor measurement invariance.[14] In the present study, we found that the mean total health literacy score was 63.1 ± 17.1 points. Meanwhile. the prevalence of low health literacy was 81.0% in Hebei Province, which was numerically lower than the prevalence of low health literacy in China in 2012.[10] The difference in the prevalence of low health literacy between Hebei Province and China could be explained by the that: Hubei Province is more developed compared to other inland provinces, meanwhile, several developed areas are located beside Hebei Province, such as Beijing; thus, the average annual household income and education level of residents in Hebei Province might be higher than that of Chinese residents, which resulted in a lower prevalence of low health literacy in Hebei Province. However, our data indicated that low health literacy was still widely prevalent in Hebei Province and specific strategies should be made to ameliorate its prevalence.

Recognizing risk factors for low health literacy prevalence is critical for the government to modulate policies and strategies to improve local health literacy.[15] According to previous studies, the risk factors for low health literacy include race, resident area (rural or urban), the number of individuals in a household, age, physical exercise, education level, occupation, household income, health information access, etc.[5,7,19] In the present study, we found that increased age, male, decreased education level, reduced annual household income and resident in rural area were correlated with lower health literacy score, and higher prevalence of inadequate health literacy. Further logistic regression analyses revealed that age, gender, education level, annual household income and resident area were closely correlated with low health literacy. Possible explanations might be that:

-

1.

as the age increased, the eyesight and hearing of an individual might get worse, which might hinder his/her ability in receiving and utilizing information to promote and maintain good health.[6] Meanwhile, in China, people with higher age might have fewer chances to get literate due to historical reasons;

-

2.

according to a previous study, male face with higher occupational stress compared to female,[21] which might limit their time on absorbing key information on promoting health status;

-

3.

people with lower education level might have worse ability in utilizing relevant information to keep them in health;

-

4.

people with lower annual household income might have more stressful lives, which limited their time on considering about critical factors for health status;

-

5.

people in rural areas might have fewer chances to receive information about promoting and maintaining good health. Therefore, these factors were closely associated with low health literacy risk, which was consistent with the results of several previous studies.[5,19,22]

There were several limitations in this study. First of all, this study combined the 2012 Chinese Resident Health Literacy Scale derived from the manual of “Chinese Resident Health Literacy-Basic Knowledge and Skills (trial edition)” published by the Chinese Ministry of Health in 2008 with a multilevel sampling procedure, which could provide a considerable degree of accuracy in the health literacy of Hebei residents; however, this study was based on the questionnaire, which might exist bias in the evaluation of the health literacy status of an individual. Therefore, developing more objective evaluation methods might eliminate this bias. Secondly, in order to achieve higher visualization of the data, some of the continuous variables were converted into categorized variables for statistical analyses, which might cause information loss. Finally, this study was based on a cross-sectional survey, thus, the direct casual inferences and the direction of casualty could not be determined.

Collectively, low health literacy is still commonly prevalent in Hebei Province; meanwhile, higher age, male, lower education level, lower annual household income and rural area closely associate with the risk of low health literacy. The findings of this study may provide potential basis for the local government polishing relevant policies to improve health literacy status of local residents, thus enhancing their overall health conditions.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Changhong Wang.

Data curation: Qiuxia Yang, Shuli Yu, Linghui Lin.

Formal analysis: Qiuxia Yang, Changhong Wang, Qiang Feng, Guangxu Niu.

Investigation: Guoxiao Gu, Ziwen Yang, Yu Qiao.

Methodology: Shuli Yu, Ziwen Yang, Huihui Liu.

Project administration: Lijing Yu, Guangxu Niu.

Resources: Guoxiao Gu, Huihui Liu, Linghui Lin, Yu Qiao, Lijing Yu, Qiang Feng.

Writing – original draft: Qiuxia Yang, Shuli Yu, Guoxiao Gu, Ziwen Yang, Huihui Liu.

Writing – review & editing: Changhong Wang, Linghui Lin, Yu Qiao, Lijing Yu, Qiang Feng, Guangxu Niu.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ANOVA = analysis of variance, CI = confidence interval, PPS = Probability Proportionate to Size, SD = standard deviation.

How to cite this article: Yang Q, Yu S, Wang C, Gu G, Yang Z, Liu H, lin L, Qiao Y, Yu L, Feng Q, Niu G. Health literacy and its socio-demographic risk factors in Hebei: a cross-sectional survey. Medicine. 2021;100:21(e25975).

QY and SY contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

¥ = RMB.

¥ = RMB, SD = standard deviation.

¥ = RMB.

¥ = RMB, CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

¥ = RMB, CI = confidence interval, OR = odds ratio.

References

- [1].Bailey SC, Brega AG, Crutchfield TM, et al. Update on health literacy and diabetes. Diabetes Educ 2014;40:581–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Berkman ND, Sheridan SL, Donahue KE, et al. Low health literacy and health outcomes: an updated systematic review. Ann Intern Med 2011;155:97–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Eichler K, Wieser S, Brugger U. The costs of limited health literacy: a systematic review. Int J Public Health 2009;54:313–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].H LY. Introduction of 2012 Chinese residents health literacy monitoring program. Chin J Health Educ 2014;30:563–5. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Hosking SM, Brennan-Olsen SL, Beauchamp A, et al. Health literacy in a population-based sample of Australian women: a cross-sectional profile of the Geelong Osteoporosis Study. BMC Public Health 2018;18:876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Liu YB, Chen YL, Xue HP, et al. Health literacy risk in older adults with and without mild cognitive impairment. Nurs Res 2019;68:433–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Liu YB, Liu L, Li YF, et al. Relationship between health literacy, health-related behaviors and health status: a survey of elderly Chinese. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:9714–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Magnani JW, Mujahid MS, Aronow HD, et al. Health literacy and cardiovascular disease: fundamental relevance to primary and secondary prevention: a scientific statement from the american heart association. Circulation 2018;138:e48–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Marmot M. Commission on social determinants of H. Achieving health equity: from root causes to fair outcomes. Lancet 2007;370:1153–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Nie XQ, Li YH, L L. Statistic analysis of 2012 Chinese residents health literacy monitoring. Chin J Health Educ 2014;30:178–81. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med 2008;67:2072–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Rudd RE. Health literacy: insights and issues. Stud Health Technol Inform 2017;240:60–78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Samerski S. Health literacy as a social practice: social and empirical dimensions of knowledge on health and healthcare. Soc Sci Med 2019;226:01–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Shen M, Hu M, Liu S, et al. Assessment of the Chinese Resident Health Literacy Scale in a population-based sample in South China. BMC Public Health 2015;15:637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Smith SG, Jackson SE, Kobayashi LC, et al. Social isolation, health literacy, and mortality risk: findings from the English longitudinal study of ageing. Health Psychol 2018;37:160–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Sorensen K, Van den Broucke S, Fullam J, et al. Health literacy and public health: a systematic review and integration of definitions and models. BMC Public Health 2012;12:80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Taylor DM, Fraser S, Dudley C, et al. Health literacy and patient outcomes in chronic kidney disease: a systematic review. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2018;33:1545–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wang C, Lang J, Xuan L, et al. The effect of health literacy and self-management efficacy on the health-related quality of life of hypertensive patients in a western rural area of China: a cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health 2017;16:58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Wang X, Guo H, Wang L, et al. Investigation of residents’ health literacy status and its risk factors in Jiangsu Province of China. Asia Pac J Public Health 2015;27:N2764–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Wu Y, Wang L, Cai Z, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of low health literacy: a community-based study in Shanghai, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2017;14:628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Yang XW, Wang ZM, Jin TY. Appraisal of occupational stress in different gender, age, work duration, educational level and marital status groups. Wei Sheng Yan Jiu 2006;35:268–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Zhang D, Wu S, Zhang Y, et al. Health literacy in Beijing: an assessment of adults’ knowledge and skills regarding communicable diseases. BMC Public Health 2015;15:799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zhang R, Dong S, Li Z. The economic and environmental effects of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei collaborative development strategy taking Hebei Province as an example. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int 2020;27:35692–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Zheng M, Jin H, Shi N, et al. The relationship between health literacy and quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2018;16:201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]