Abstract

Purpose:

Despite well-established substance use disparities between sexual and gender minority adolescents and their heterosexual, cisgender peers, there remain questions about whether there are developmental differences in the onset and progression of these disparities across adolescence. These perspectives are critical for prevention efforts. We therefore estimate age-based patterns of five substance use behaviors across groups of adolescents defined by sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI).

Methods:

Data are from the cycles of the California Healthy Kids Survey (n=634,454). Substance use was assessed with past 30-day e-cigarette use, combustible cigarette use, alcohol use, heavy episodic drinking, and marijuana use. Two- and three-way interactions were used to assess differences in age-specific prevalence rates of each substance by (1) sex and sexual identity; and (2) gender identity.

Results:

Across all substances, SOGI difference in past 30-day use were present by age 12 years. Most disparities persisted to age 18 years and older. SOGI disparities in combustible and e-cigarette use were wider in late adolescence. Analyses by sexual identity show that sexual minority girls reported the highest rates of substance use across age, followed by sexual minority boys.

Conclusions:

SOGI differences in substance use emerged in early adolescence and appeared to persist and accelerate by late adolescence. Sexual minority girls had the highest rates of substance use across all ages. The findings underscore the urgent need for screening and prevention strategies to reduce substance use for sexual and gender minority youth.

Keywords: LGBTQ youth, LGBT youth, Sexual minority youth, Gender minority youth, Sexual and gender minority, Substance use, Cigarette, E-cigarette, Marijuana, Alcohol, Adolescence, Disparities, Health disparities

Sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI)-related disparities in substance use are well established [1–3] and have been linked to the chronic stressors inherent to navigating heteronormative and cisnormative social contexts (e.g., stigma, family rejection, bullying, and victimization) [2,4—6]. Despite research that documents disproportionate substance use among sexual and gender minority (SGM) youth, studies rarely use age-based designs, which offer unique perspectives on when SOGI-related disparities emerge and progress during adolescence alongside gender and sexual identity development and expression [7,8]. Given that adolescence is a common time for substance use onset and acceleration and that substance use behaviors during adolescence set the stage for substance use and related problems later in the life course [9–11], age-based studies among youth are uniquely important for understanding SOGI-related substance use disparities. This is especially important for youth who are in the process of understanding and identifying minoritized sexual and gender identities, given that the unique stressors related to these stigmatized identities may increase the risk for maladaptive coping strategies, such as substance use [4,12,13]. These insights provide critical information about when prevention and intervention strategies may be most effective for combating SOGI-related disparities in substance use across the life course and the mechanisms that drive them.

Sexual orientation and gender identity differences in substance use and abuse

There is irrefutable evidence supporting heightened risk for substance use among SGM youth [3,4,14]. Studies consistently document elevated rates of alcohol use, heavy episodic binge drinking, high-intensity binge drinking, combustible and e-cigarette use, marijuana use, and other illicit drugs among sexual minority (SM) relative to heterosexual adolescents [7,15,16]. Substance use among transgender youth is less well understood. Available population-based cross-sectional studies find that gender minority youth show elevated rates of substance use relative to their cisgender peers. The 2017 Youth Risk Behavior Survey report found that transgender youth were more likely to report lifetime use of all substances relative to cisgender girls and boys (i.e., cigarettes, alcohols, cocaine, heroin, methamphetamines, ecstasy, inhalants, and prescription opioid misuse), with the exception of marijuana [17]. A study using state-representative data from California found that transgender youth had 2.33 times greater odds of past 30-day heavy episodic drinking, 1.79 greater odds of past 30-day cigarette use, 1.93 greater odds of marijuana use, and 2.35 greater odds of past 30-day polysubstance use than their nontransgender peers [2]. The findings from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Wave 3 data also found that transgender youth reported greater electronic, smokeless, and combustible tobacco use than their cisgender counterparts [18].

Unfortunately, SOGI differences in onset and trajectories of substance use have been hindered by a lack of data; longitudinal panel data have historically excluded measures of sexual orientation and to a greater extent gender identity. Many of the longitudinal studies available come from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health (Add Health) [7,19] and the Growing Up Today Study [8,20,21]. The findings from Add Health suggest that sexual orientation disparities in general substance use and individual substances are present at baseline (youth age 13–18 years) and continue into adulthood. Some longitudinal findings suggest accelerated use across the transition to adulthood among SM girls/women [7], whereas others suggest that heterosexual and SM youth show similar rates of change [19]. Studies from the Growing Up Today Study data similarly find sexual orientation disparities in substance use [20,21 ] but also earlier onset for alcohol use and consistent sexual orientation disparities in alcohol use behaviors between SM and heterosexual females, and, to a lesser extent, males [20]. Despite their importance, longitudinal assessments have largely focused on alcohol use or composite measures of substance use [7,8,19–21], limiting understanding of how trajectories may differ across substances. Furthermore, youth data from these sources are dated, start in mid-adolescence, and rely on measurement spaced multiple years apart.

Despite increased awareness of gender identity differences in substance use, there are few studies documenting developmental differences. One study of Californian youth found few age-of-onset differences between transgender and nontransgender students [2], suggesting that there may be a time of rapid acceleration of use for transgender youth that differ from comparisons between SM and majority youth.

The present study

The present study addresses several gaps in the current scholarship regarding substance use among SGM youth to inform the timing of prevention efforts aimed to address them. In particular, we are interested in assessing whether age-based differences in substance use vary by sexual and gender identity. Using a population-based sample, we identify age-specific prevalence rates of past 30-day e-cigarette use, combustible cigarette use, alcohol use, heavy episodic binge drinking, and marijuana use stratified by (1) sexual orientation; and (2) gender identity among a sample of middle and high school students (aged 12–18 years and older). The findings extend the current literature by providing a developmental perspective of when SOGI-related disparities in specific substance use behaviors emerge and how they differ by age across adolescence. The investigation is strengthened by our ability to estimate these differences independently for SGM youth, potentially illuminating differential patterns of substance use across adolescence for these populations.

Methods

Data source and sample

Data are from the 2013–2014 and 2014–2015 cycles of California Healthy Kids Survey (CHKS). A biennial, cross-sectional school-based survey administered to students in 7th, 9th, and 11th-grade classrooms, the CHKS is the largest statewide survey of middle and high school students in the U.S. Administered by WestEd, each cycle of the CHKS is administered over a 2-year period and tracks health risk and resilience among youth. Following direction from WestEd, we exclude youth whose data raise concerns of validity (1.32%) and youth aged <12 years. Decisions for age restrictions were twofold. First, there are smaller numbers of youth in CHKS aged <12 years. Second, self-reported substance use among youth aged <12 years was exceedingly low. Our sample is further limited to youth who provide valid responses for age (range 12–18 years and older), sex, sexual and gender identity, race/ethnicity, parent education, and outcomes of interest (N=634,454). The present study was approved by the institutional review board.

Measures

Substance use.

Past-month cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use was assessed by asking, “During the past 30 days, on how many days did you [use substance]? Heavy episodic drinking was assessed as “five or more drinks of alcohol in a row, that is, within a couple of hours.” Response options ranged from 0 days = 0 to 20–30 days = 6. Items were dichotomized to reflect recent use (yes = 1 and no = 0).

Sexual orientation and gender identity.

SOGI status was assessed with a single multiple response option item, which asked, “Which of the following best describes you? (Mark all that apply),” with response options of heterosexual (straight); gay, lesbian, or bisexual; transgender; not sure; and decline to respond. To measure sexual orientation, we coded dichotomous variables for youth who were heterosexual (nonheterosexual = 0 and heterosexual = 1), SM (non-SM = 0 and SM = 1), and unsure (non-unsure = 0 and unsure = 1). Heterosexual is omitted and thus serves as the reference category. We measured gender identity (nontrans boys = 0, nontrans girls = 1, and trans youth = 2) by constructing a variable from participants’ response to whether they were transgender and their sex [2].

Sex.

Participants were asked, “What is your sex?” Response options included male = 0 and female = 1.

Age.

Youth age was assessed with the item, “How old are you?” Responses ranged from 1 = 10 years old or younger to 9 = 18 years old or older.

Covariates.

Models were adjusted for youth race/ethnicity (white [ref], Black/African American, Hispanic, Asian American, Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, multiracial, and no race reported). Parental education was assessed by asking youth, “What is the highest level of education your parents completed?” (Did not finish high school [ref], graduated from high school, attended college but did not complete, graduated from college, and do not know). Given that youth could select multiple SOGI responses, models were also adjusted for youth who reported “not sure.” Similarly, sexual orientation models were adjusted for gender identity (in models testing sexual orientation differences) and sexual orientation among nontrans youth (when testing gender identity differences). Finally, models were adjusted for the school year during which data were collected (2013–2014 vs. 2014–2015).

Analytic approach

After the calculation of sample demographic characteristics, Rao-Scott chi-square test of independence was used to test SOGI differences in all substance use outcomes. Next, SOGI differences in age-specific prevalence of substance use were calculated using multivariate logistic regression models. Sexual orientation differences were estimated using three-way interactions between youth age, sex, and sexual orientation (age × sex × sexual orientation) adjusting for race/ethnicity, parental education, and school year. Gender identity differences were estimated using two-way interactions between age and gender identity (age × gender identity). Predicted probabilities were then calculated, which provide estimates that reflect the adjusted percentage of youth who report recent substance use for each age year per group (e.g., estimated prevalence of alcohol use among 12-year-old lesbian, gay, bisexual boys). All data management and analysis were conducted in Stata 15.1. [22].

Results

Sample demographic characteristics are presented in Table 1. The sample comprised 47.42% of non-SM boys, 47.11% of non-SM girls, 1.79% of SM boys, and 3.68% of SM girls. Overall, 1.11% of the sample were transgender. Bivariate analysis showed that, compared with non-SM boys and girls, SM boys and girls had about three times the prevalence of combustible cigarette use (4.77% vs. 13.36% for boys; 3.42% vs.14.52% for girls) and two times the prevalence of e-cigarette use (11.33% vs. 20.09% for boys; 9.30% vs. 22.99% for girls), respectively. SM boys and girls also had elevated rates of alcohol use (26.90% of SM boys, 35.07% of girls) and heavy episodic binge drinking (17.12% of boys, 20.17% of girls) when compared with their same-sex heterosexual peers (15.21% and 17.53% for alcohol use, and 8.79% and 8.36% for binge drinking for non-SM boys and girls, respectively). Approximately 12% of non-SM boys and 10.18% of non-SM girls reported marijuana use relative to 21.68% of SM boys and 28.82% of SM girls.

Table 1.

Sample Demographic Characteristics, California Healthy Kids Survey (2013–2014, 2014–2015)

| Overall Sample | Sexual Orientation | Comparison Sample | Gender Identity Comparison Sample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| non-SM Boys | SM boys | non-SM Girls | SM Girls | Nontrans boys | Nontrans girls | Trans youth | |||

| n | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | |

| Age | |||||||||

| 12 years old | 118,030 | 18.60 | 17.87% | 9.59% | 20.41% | 9.34% | 17.67% | 19.67% | 11.27% |

| 13 years old | 79,199 | 12.48 | 13.36% | 9.67% | 11.99% | 8.88% | 13.26% | 11.76% | 11.16% |

| 14 years old | 125,937 | 19.85 | 18.99% | 18.25% | 20.70% | 20.80% | 18.96% | 20.71% | 19.83% |

| 15 years old | 92,651 | 14.60 | 15.24% | 17.28% | 13.59% | 18.02% | 15.28% | 13.89% | 17.56% |

| 16 years old | 122,782 | 19.35 | 18.50% | 23.16% | 19.72% | 23.77% | 18.63% | 20.01% | 21.12% |

| 17 years old | 79,564 | 12.54 | 13.19% | 17.43% | 11.45% | 15.73% | 13.32% | 11.74% | 14.85% |

| 18 or older | 16,291 | 2.57 | 2.84% | 4.61% | 2.15% | 3.46% | 2.88% | 2.23% | 4.22% |

| Sex | - | - | |||||||

| Male | 312,197 | 49.21 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 62.09% |

| Female | 322,257 | 50.79 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 37.91% |

| Gender Identity | |||||||||

| Nontransgender | 627,409 | 98.89 | 99.32% | 79.47% | 99.56% | 94.19% | - | - | - |

| Transgender | 7,045 | 1.11 | 0.68% | 20.53% | 0.44% | 5.81% | - | - | - |

| Sexual Orientation | |||||||||

| Non-SM | 599,781 | 94.53 | - | - | - | - | 97.08% | 93.12% | 47.74% |

| SM | 34,673 | 5.47 | - | - | - | - | 2.92% | 6.88% | 52.26% |

| Not Sure Sexual Orientation | |||||||||

| Not marked | 593,275 | 93.51 | 94.82% | 80.15% | 93.05% | 89.04% | 94.81% | 92.95% | 62.11% |

| Marked | 41,179 | 6.49 | 5.18% | 19.85% | 6.95% | 10.96% | 5.19% | 7.05% | 37.89% |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||||||

| American Indian/Alaska Native | 25,945 | 4.09 | 4.40% | 4.36% | 3.76% | 4.13% | 4.39% | 3.79% | 4.63% |

| Asian/Asian American | 88,245 | 13.91 | 14.15% | 11.95% | 14.16% | 8.53% | 14.10% | 13.77% | 11.68% |

| Black/African American | 33,586 | 5.29 | 5.67% | 7.23% | 4.72% | 6.88% | 5.66% | 4.85% | 9.68% |

| Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander | 15,068 | 2.37 | 2.53% | 3.00% | 2.21% | 2.21% | 2.54% | 2.21% | 2.87% |

| White | 202,174 | 31.87 | 31.49% | 31.99% | 32.47% | 28.84% | 31.51% | 32.22% | 31.24% |

| Two or more races | 269,436 | 42.47 | 41.76% | 41.47% | 42.68% | 49.40% | 41.80% | 43.17% | 39.90% |

| Hispanic/Latino | |||||||||

| No | 350,906 | 55.31 | 56.16% | 55.99% | 54.67% | 52.09% | 56.12% | 54.50% | 56.32% |

| Yes | 283,548 | 44.69 | 43.84% | 44.01% | 45.33% | 47.91% | 43.88% | 45.50% | 43.68% |

| Parent Education | |||||||||

| Some high school | 76,444 | 12.05 | 10.62% | 13.28% | 13.12% | 16.16% | 10.67% | 13.32% | 14.42% |

| Finished high school | 99,279 | 15.65 | 15.46% | 15.58% | 15.62% | 18.39% | 15.49% | 15.82% | 14.68% |

| Some College | 81,805 | 12.89 | 11.84% | 13.59% | 13.64% | 16.58% | 11.89% | 13.85% | 13.48% |

| Graduated college | 259,125 | 40.84 | 41.73% | 41.01% | 40.55% | 33.10% | 41.71% | 40.04% | 39.29% |

| Don’t Know | 117,801 | 18.57 | 20.35% | 16.54% | 17.07% | 15.76% | 20.23% | 16.97% | 18.13% |

| Past-month e-cigarette | |||||||||

| No | 564,927 | 89.04 | 88.67% | 79.91% | 90.70% | 77.01% | 88.56% | 89.83% | 74.39% |

| Yes | 69,527 | 10.96 | 11.33% | 20.09% | 9.30% | 22.99% | 11.44% | 10.17% | 25.61% |

| Past-month combustible cigarette use | |||||||||

| No | 605,000 | 95.36 | 95.23% | 86.64% | 96.58% | 85.48% | 95.10% | 95.88% | 82.84% |

| Yes | 29,454 | 4.64 | 4.77% | 13.36% | 3.42% | 14.52% | 4.90% | 4.12% | 17.16% |

| Past-month alcohol use | |||||||||

| No | 525,044 | 82.76 | 84.79% | 73.10% | 82.47% | 64.93% | 84.58% | 81.30% | 68.84% |

| Yes | 109,410 | 17.24 | 15.21% | 26.90% | 17.53% | 35.07% | 15.42% | 18.70% | 31.16% |

| Past-month heavy episodic binge drinking | |||||||||

| No | 576,364 | 90.84 | 91.21% | 82.88% | 91.64% | 79.83% | 91.12% | 90.88% | 77.19% |

| Yes | 58,090 | 9.16 | 8.79% | 17.12% | 8.36% | 20.17% | 8.88% | 9.12% | 22.81% |

| Past-month marijuana use | |||||||||

| No | 558,520 | 88.03 | 87.93% | 78.32% | 89.82% | 71.18% | 87.79% | 88.58% | 73.87% |

| Yes | 75,934 | 11.97 | 12.07% | 21.68% | 10.18% | 28.82% | 12.21% | 11.42% | 26.13% |

Transgender youth also showed elevated rates of each substance relative to nontransgender girls and boys. Approximately, 17% of transgender youth reported using combustible cigarettes relative to 4.90% of nontransgender boys, and 4.12% of nontransgender girls; transgender youth were also more likely to report e-cigarette use (25.61%) when compared with nontransgender boys (11.44%) and girls (10.17%). Transgender youth had higher prevalence rates for alcohol use (31.16%) and heavy episodic binge drinking (22.81%) than nontransgender boys (15.42% and 8.88%, respectively) and nontransgender girls (18.70% and 9.12%, respectively). Transgender youth also had over twice the rate of marijuana use (26.13%) compared with nontransgender boys and girls (12.21% and 11.42%, respectively).

Sexual orientation differences in substance use by age

Three-way interaction terms estimating differences by age, sex, and sexual identity were significant for each substance (Table 2). For ease, predicted probabilities and corresponding 95% confidence intervals are displayed as figures (Figure 1). With few exceptions (no statistical differences in alcohol use between SM boys and non-SM girls at age 16 and 17 years, heavy episodic binge drinking between SM boys and non-SM boys at age 17 years, and marijuana use between non-SM boys and SM boys at age 17 years), SM girls and boys had higher rates of substance use relative to non-SM boys and girls across all substance use outcomes and ages. SM girls had the highest rates of substance use across all ages and statistically differed from non-SM boys and girls across all outcomes and ages. Differences between SM girls and boys were not always significant; SM boys and girls showed fairly similar rates of combustible and e-cigarette use across age, whereas SM girls showed significantly higher rates of past-month alcohol and marijuana use relative to SM boys across most ages.

Table 2.

Wald’s F Test of Interaction Terms

| Sex x Sex Identity x Age | Gender x Age | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F (6, 2357) | p | F (12, 2351) | p | |

| E-cigarette use | 3.13 | .005 | 26.84 | >.001 |

| Combustible cigarette use | 6.72 | >.001 | 26.38 | >.001 |

| Alcohol use | 2.58 | .017 | 41.95 | >.001 |

| Heavy episodic binge drinking | 3.27 | .003 | 45.15 | >.001 |

| Marijuana use | 2.67 | .014 | 29.87 | >.001 |

Figure 1.

Age-specific predicted probabilities of sexual orientation differences in e-cigarette use, combustible cigarette use, alcohol use, binge drinking, and marijuana use. California Healthy Kids Survey (2013, 2015). Predicted probabilities were estimated from models testing three-way interactions between sex, sexual identity, and age.

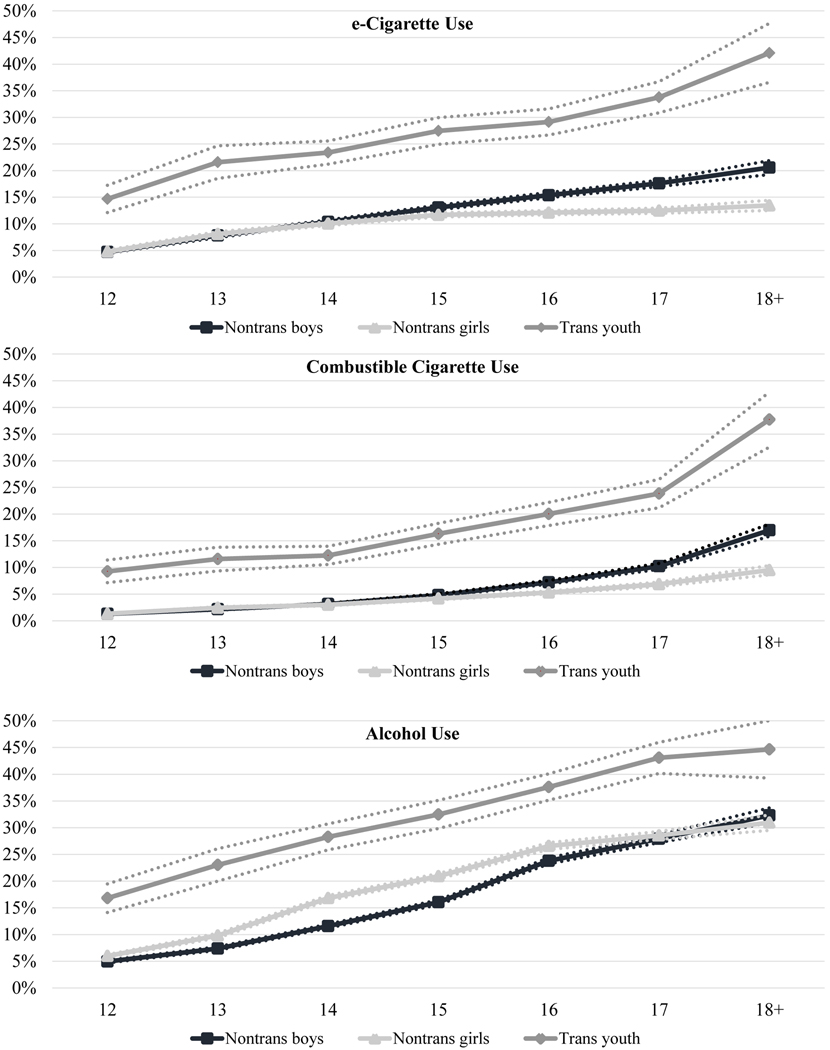

Gender identity differences in substance use by age

Two-way interaction terms testing substance use differences by age and gender identity were significant for each substance (Table 2). Predicted probabilities of these interactions are shown in Figure 2. Gender identity disparities in each of the five substance use behaviors were present by age 12 years and persisted across years. Although substance use increased for each gender identity subgroup, the rates of change varied by gender identity. For example, e-cigarette use disparities persisted and were wider among older adolescents: Among 12-year-olds, there was an ~10% difference between transgender youth and nontransgender boys and girls, but there was an ~30% difference in use between transgender youth and nontransgender girls and a ~20% differences between transgender youth and nontransgender boys among youth aged 18+ years. A similar pattern was present for combustible cigarette use and marijuana use. Gender identity differences in alcohol use were more narrow between transgender and nontransgender youth of older ages. Transgender youth were consistently more likely that nontransgender youth to report heavy episodic binge drinking, and the differences were particularly wide among youth aged 18+ years.

Figure 2.

Age-specific predicted probabilities of gender identity differences in e-cigarette use, combustible cigarette use, alcohol use, binge drinking, and marijuana use. California Healthy Kids Survey (2013, 2015). Predicted probabilities were estimated from models testing two-way interactions between gender identity and age.

Discussion

We sought to address the lack of developmental studies examining SOGI-related substance use disparities by assessing whether age-specific prevalence rates of cigarette, alcohol, and marijuana use varied by SOGI. Our findings show that across all substances, SOGI differences in substance use were present by age 12 years and for the most part persisted across adolescence. In many cases, we also found that differences in substance use between SGM and non-SGM youth were often wider among older adolescents, suggesting a potential acceleration of substance use among SGM youth as they age. The findings underscore the urgent need for screening and prevention strategies to reduce substance use for SGM youth and for these efforts to begin in early adolescence.

Perhaps, the most striking finding is that all SOGI differences in recent substance use were present by age 12 years. Although not specifically a measure of substance use onset, these findings are consistent with other studies that document earlier age of use for SM youth. Generally, the emergence of disparities early in adolescence suggests both earlier onset of substance use but, more importantly, greater engagement with substance use early on, which is a risk factor for substance use and abuse later in adulthood [9,11,23]. Although sexual orientation differences in the early onset of substance use are documented [11,14,24], there is much less research on whether gender minority youth are vulnerable to early onset. In one study looking at a representative subsample of the CHKS, transgender youth did not differ from nontransgender youth in early onset [2]. Although we do not directly assess age at first use, our findings suggest that disparities in general use for transgender youth start at young ages.

Our findings also highlight important sex/gender differences in SOGI-related substance use disparities across age. With the exception of alcohol use, non-SM boys and girls were either similar or boys had higher rates of substance use. Conversely, SM girls had the highest rates of use across all substances and ages. It is well documented that sexual orientation differences in substance use are most consistent among girls/women, relative to boys/men [3,25]. Still, our findings extend this literature in two important ways. First, we were able to compare the rates of use across groups defined by both sex and sexual identity. Our findings show that SM girls not only show larger disparities when compared with non-SM girls but also elevated rates relative to heterosexual and SM boys. Second, we observed sex differences in the degree to which SM and non-SM youth differ in substance use across adolescence. That is, sexual orientation differences among girls were larger and tended to widen across ages, whereas differences among boys were less pronounced and were typically more narrow among older youth. Despite well-documented sex differences in sexual orientation—related substance use disparities [3,26], knowledge on why this disparity exists is still nascent. The findings of this study encourage future research to consider the early experiences that place SM youth at risk and how experiences related to sex/gender uniquely impact the risk for substance use.

Substance use research on transgender youth has lagged relative to SM youth [14]. Our results suggest that transgender youth are also vulnerable to early and persistent risk for alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use. First and foremost, irrespective of age, we observed appreciable differences in substance use between transgender and nontransgender youth. For example, transgender youth had prevalence rates of alcohol, tobacco, and marijuana use that were two, three, and four times greater than their cisgender peers, respectively. Similar to SM youth, gender identity disparities were already present by age 12 years and, for the most part, persisted and widened across all ages. For example, gender identity differences in substance use were 5%—10% among 12-year-olds. By age 18+ years, transgender youth showed twice that difference—a 20%—30% gap in use across substances. In line with findings among SM youth, the results for transgender youth demonstrate a need for early and ongoing preventive intervention strategies to address substance use and additional insight into the mechanisms that contribute to gender identity disparities during adolescence.

More generally, SGM-related disparities in substance use and other health conditions are often attributed to interpersonal and enacted minority stressors such as victimization and discrimination. However, there are likely other developmental and cognitive processes that converge with minority stress to contribute to elevated substance use among SGM youth. For example, the developmental timing of SGM identity formation processes may contribute to the early and progressing substance use disparities observed in the present study [12]. Recent data suggest that SM people increasingly develop and disclose SM identities during adolescence [27], a developmental context characterized by peers’ rigid surveillance of sexuality and gender, taxing pubertal processes, and often unreliable support from educators and family. Thus, SGM identity development and disclosure may expose youth to unique minority stressors, including victimization, rejection, and concealment [28,29], which may spark substance use as a maladaptive coping strategy [4] or as a way to fit in with peers [30]. Similarly, a recent study showed that gender minority youth were less likely to perceive substance use as risky compared with their nongender minority peers [2]. Such differences in perceptions of risk across subgroups may be a distinct pathway that elevates the risk for transgender youth and a targetable mechanism for prevention and intervention. These data encourage a broader research perspective on how SGM youth come to use substances and consider how normative ontological process collides with distinct developmental experiences for SGM youth—approaches that may offer fruitful strategies for prevention and intervention.

Despite the growing number of studies that highlight SGM youth substance use vulnerability, a recent meta-analysis only identified two interventions for LGBTQ-specific substance use interventions [31 ]. There is pressing need for increased screening and the development of prevention and intervention programs designed to address substance use among SGM youth and at developmentally appropriate times. This includes learning about the factors that influence the experiences of LGBT youth as children [32] and potentially distinct and targetable mechanisms of substance use for subgroups of SGM youth. For example, SM girls in our sample showed the highest rates of substance use across ages relative to SM boys and non-SM boys and girls. It would be helpful to understand what unique experiences or strategies might be addressed to mitigate use for this population at this critical period of the life course. Similarly, the implementation of developmentally sensitive policies, programs, and practices that protect and support transgender youth throughout adolescence may help dampen the accelerated substance use that we observe in these data. Early intervention is a major component to combating SOGI-related health inequities, given the ties between substance use, mental health, and resulting comorbidity across the life course. Thus, investments in early prevention and intervention would support population health goals outlined by the National Institutes of Health [33], the Center for Disease Control and Prevention [34], and other Health and Human Service bodies [35].

Limitations and opportunities for future research

There are limitations to note. First and foremost, the CHKS data are not longitudinal, and we are therefore limited in our ability to generalize these trends to intraindividual changes in substance use across adolescence; future work will be necessary to assess this. Second, the CHKS measure of SOGI is limited. Because of the measurement approach that allowed youth to select any response from a specific list that included both sexual and gender identity labels, it is not possible to compare substance use differences across different SOGI subgroups. It is not possible, for example, to distinguish the experiences of lesbian/gay compared with bisexual youth or youth with other SM identities [36]. Given the elevated rates of substance use among bisexual youth, future studies that are able to test developmental trends among SM subgroups are necessary. Similarly, the current data do not allow for comparisons among transgender youth who identify as transmasculine, transfeminine, or nonbinary. Given preliminary research that highlights differences in substance use across these identities [36], future research would benefit from exploring developmental trends by gender identity subgroups.

Third, given the complexity of the current analysis, we were unable to assess how other relevant social identities may impact substance use. For example, there are well-established racial/ ethnic differences in youth substance use, and these differences likely vary in unique ways when SOGI are also considered. Similarly, youth live in vastly different social and policy contexts that may alter both their substance and SOGI-related stressors and resources. Future research should investigate how these patterns vary for youth on the basis of race/ethnicity and social context, among other factors. These investigations are necessary to uncover heterogeneity of risk for substance use among SGM youth and the factors that might influence these differences. For example, we may find smaller disparities and less acceleration of substance use among youth who are in more SGM-affirmative contexts, or where specific policy profiles are particularly efficient at delaying or dampening substance use across adolescence for SGM youth.

Fourth, estimates for youth who were aged 18+ years had wider confidence intervals than estimates of other ages and should be interpreted with caution. Not only were there smaller numbers of youth aged 18 years and older in the sample but also given that the CHKS sampling strategy limits recruitment to youth in 7th, 9th, and 11th-grade classrooms, youth from the age group are unusual among students in high school. Similarly, our age-based design captures the experiences of younger adolescents, who may be less likely to identify or disclose a SOGI identity than older adolescents. This may impact findings for these younger age groups. If, in fact, younger adolescents are less likely to disclose a SOGI identity, we would expect that disparities might actually be greater at younger ages than what we report here. The CHKS’s grade-based sampling design also means that we had sufficient but differential data coverage across ages, and this may explain (in part) why the percentage of SM youth varies by age. For example, there was almost a 6% difference in SM males aged between 16 and 17 years. If not an artifact of the sampling design, these differences could be related to academic delays or school pushout that have accumulated among older SM youth who experience more hostile learning environments [37].

Finally, given the nature of the data (i.e., cross-sectional and school-based), we are not able to strategically assess why SGM youth are displaying disparities at such a young age. Although we can rely on the broader literature to help contextualize and explain these findings, there is a dire need for research that seeks to understand how childhood experiences—across various contexts—converge to elevate substance use risk for this population. These investigations also need to include an exploration of who SGM youth socialize with and how peer experiences and networks influence risk for substance use among SGM youth [38,39]. These types of investigations have the potential to reveal new and unique information about substance use risk for SGM youth but remain underexplored [15].

Despite these limitations, this study offers new perspectives on SGM youth substance use that underscore the importance of early intervention, given that precursors to SOGI-related disparities in substance use are likely experienced in childhood. Future research is needed to better understand the early experiences that contribute to SOGI-related health disparities in adolescence [40], as these early differences in substance use have been shown to persist across the life course [11,41]. In the meantime, researchers, practitioners, and community members need to work together to develop strategies that identify and address SOGI-related risk for substance use in early adolescence. Programs and policies that address substance use during adolescence are a necessary cornerstone to mitigating SOGI-related health disparities and ensuring health and well-being across the life course for this population.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTION.

Sexual orientation and gender identity differences in tobacco, alcohol, and marijuana use are present by age 12 and persist across adolescence. Disparities in combustible and e-cigarette use were wider at older ages. Sexual minority girls had the highest rates of substance use across all ages.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

The California Healthy Kids Survey was developed by WestEd under contract to the California Department of Education. J.N.F. acknowledges support from the University of Maryland Prevention Research Center cooperative agreement U48DP006382 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and P2CHD041041, awarded to the Maryland Population Research Center by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. M.D.B. gratefully acknowledges support from two grants awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin (P2CHD042849 and T32HD007081) by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. S.T.R. acknowledges support from the Priscilla Pond Flawn Endowment at the University of Texas at Austin and P2CHD042849, awarded to the Population Research Center at The University of Texas at Austin.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Disclaimer: The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- [1].Corliss HL, Wadler BM, Jun H-J, et al. Sexual-orientation disparities in cigarette smoking in a longitudinal cohort study of adolescents. Nicotine Tob Res 2013;15:213–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Day JK, Fish JN, Perez-Brumer A, et al. Transgender youth substance use disparities: Results from a population-based sample. J Adolesc Health 2017;61:729–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, et al. Sexual orientation and adolescent substance use: A meta-analysis and methodological review. Addiction 2008;103:546–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Goldbach JT, Tanner-Smith EE, Bagwell M, Dunlap S. Minority stress and substance use in sexual minority adolescents: A meta-analysis. Prev Sci 2014;15:350–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Ryan C, Huebner D, Diaz RM, Sanchez J. Family rejection as a predictor of negative health outcomes in white and Latino lesbian, gay, and bisexual young adults. Pediatrics 2009;123:346–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Reisner SL, Greytak EA, Parsons JT, Ybarra ML. Gender minority social stress in adolescence: Disparities in adolescent bullying and substance use by gender identity. J Sex Res 2015;52:243–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Marshal MP, Friedman MS, Stall R, Thompson AL. Individual trajectories of substance use in lesbian, gay and bisexual youth and heterosexual youth. Addiction 2009;104:974–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Coulter RWS, Jun H-J, Calzo JP, et al. Sexual-orientation differences in alcohol use trajectories and disorders in emerging adulthood: Results from a longitudinal cohort study in the United States. Addiction 2018;113: 1619–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Brown SA, McGue M, Maggs J, et al. A developmental perspective on alcohol and youths 16 to 20 years of age. Pediatrics 2008;121:S290–310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Schulenberg JE, Patrick ME, Kloska DD, et al. Substance use disorder in early midlife: A national prospective study on health and well-being correlates and long-term predictors. Subst Abuse Res Treat 2016;9(Suppl 1):41–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Schuler MS, Collins RL. Early alcohol and smoking initiation: A contributor to sexual minority disparities in adult use. Am J Prev Med 2019;57:808–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Russell ST, Fish JN. Sexual minority youth, social change, and health: A developmental collision. Res Hum Dev 2019;16:5–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Russell ST, Fish JN. Mental health in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) youth. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2016;12:465–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Talley AE, Gilbert PA, Mitchell J, et al. Addressing gaps on risk and resilience factors for alcohol use outcomes in sexual and gender minority populations. Drug Alcohol Rev 2016;35:484–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mereish EH. Substance use and misuse among sexual and gender minority youth. Curr Opin Psychol 2019;30:123–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Dai H. Tobacco product use among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adolescents. Pediatrics 2017;139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Johns MM, Lowry R, Andrzejewski J, et al. Transgender identity and experiences of violence victimization, substance use, suicide risk, and sexual risk behaviors among high school students—19 states and large urban school districts, 2017. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2019;68:67–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Johnson SE, O’Brien EK, Coleman B, et al. Sexual and gender minority U.S. youth tobacco use: Population assessment of tobacco and health (PATH) study wave 3, 2015–2016. Am J Prev Med 2019;57:256–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Needham BL. Sexual attraction and trajectories of mental health and substance use during the transition from adolescence to adulthood. J Youth Adolesc 2012;41:179–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, et al. Sexual orientation disparities in longitudinal alcohol use patterns among adolescents: Findings from the growing up today study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162:1071–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Corliss HL, Rosario M, Wypij D, et al. Sexual orientation and drug use in a longitudinal cohort study of U.S. adolescents. Addict Behav 2010;35:517–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schulenberg JE, Maslowsky J, Jager J. Substance use and abuse during adolescence and the transition to adulthood are developmental phenomena: Conceptual and empirical considerations. In: Alcohol use disorders: A developmental science approach to etiology. Oxford University Press; 2018:199–222. [Google Scholar]

- [24].Talley AE, Hughes TL, Aranda F, et al. Exploring alcohol-use behaviors among heterosexual and sexual minority adolescents: Intersections with sex, age, and race/ethnicity. Am J Public Health 2014;104:295–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ploderl M, Tremblay P. Mental health of sexual minorities. A systematic review. Int Rev Psychiatry 2015;27:367–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Hughes TL, Wilsnack SC, Kantor LW. The influence of gender and sexual orientation on alcohol use and alcohol-related problems. Alcohol Res Curr Rev 2016;38:121–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bishop MD, Fish JN, Hammack PL, Russell ST. Sexual identity development milestones in three generations of sexual minority people: A national probability sample. Dev Psychol 2020;56:2177–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Friedman MS, Marshal MP, Stall R, et al. Gay-related development, early abuse and adult health outcomes among gay males. AIDS Behav 2008;12: 891–902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Spivey LA, Edwards-Leeper L. Future directions in affirmative psychological interventions with transgender children and adolescents. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol 2019;48:343–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Bos H, van Beusekom G, Sandfort T. Drinking motives, alcohol use, and sexual attraction in youth. J Sex Res 2016;53:309–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Coulter RWS, Egan JE, Kinsky S, et al. Mental health, drug, and violence interventions for sexual/gender minorities: A systematic review. Pediatrics 2019;144:e20183367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Clark CM. Reducing heterosexist attitudes toward relationships in young children. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [33].National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Sexual and gender minorities formally designated as a health disparity population for research purposes. NIMHD. Available at: https://www.nimhd.nih.gov/about/directors-corner/messages/message_10-06-16.html. Accessed October 3, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [34].Center for Disease Control and Prevention. LGBT youth: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/youth.htm. Accessed June 30, 2020.

- [35].Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: Healthy people. 2020. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-health?topicid=25. Accessed September 22, 2019.

- [36].Wheldon CW, Kaufman AR, Kasza KA, Moser RP. Tobacco use among adults by sexual orientation: Findings from the population assessment of tobacco and health study. LGBT Health 2018;5:33–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Snapp SD, Hoenig JM, Fields A, Russell ST. Messy, butch, and queer: LGBTQ youth and the school-to-prison pipeline. J Adolesc Res 2015;30:57–82. [Google Scholar]

- [38].Hussong AM, Ennett ST, McNeish D, et al. Teen social networks and depressive symptoms-substance use associations: Developmental and demographic variation. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 2018;79:770–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Montgomery SC, Donnelly M, Bhatnagar P, et al. Peer social network processes and adolescent health behaviors: A systematic review. Prev Med 2020;130:105900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Martin-Storey A, Fish J. Victimization disparities between heterosexual and sexual minority youth from ages 9 to 15. Child Dev 2019;90:71–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].McCabe SE, Hughes TL, Bostwick WB, et al. Sexual orientation, substance use behaviors and substance dependence in the United States. Addiction 2009;104:1333–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]