Abstract

Purpose:

Medically ill youth are at increased risk for suicide. For convenience, hospitals may screen for suicide risk using depression screening instruments, though this practice might not be adequate to detect those at risk for suicide. This study aims to determine whether depression screening can detect suicide risk in pediatric medical inpatients who screen positive on suicide-specific measures.

Methods:

A convenience sample of medical inpatients ages 10–21 years were recruited as part of a larger instrument validation study. Participants completed the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ), the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ/SIQ-JR), and the Patient Health Questionnaire – Adolescent Version (PHQ-A). Univariate and multivariate statistics were calculated to examine the relationship between screening positive for depression and suicide risk.

Results:

The sample consisted of 600 medical inpatients (59.2% female; 55.2% White; mean age 15.2±2.84 years). Of participants who screened positive for suicide risk (13.5%; 81/600), 39.5% (32/81) did not screen positive for depression, and more than half (45/81) did not endorse PHQ-A item 9, which queries for thoughts of harming oneself or being better off dead. Twenty-six participants (32%) who screened negative for depression and on PHQ-A item 9 were at risk for suicide.

Conclusions:

In this sample, depression screening alone failed to detect nearly a third of youth at risk for suicide. Although depression and suicide risk are strongly related, a significant portion of pediatric medical inpatients at risk for suicide may pass through the healthcare system unrecognized if depression screening is used as a proxy for identifying suicide risk.

Keywords: suicide risk screening, depression screening, pediatric medical patients

In 2018, 27% of all deaths for youth ages 10–24 in the United States were from suicide. In national efforts to lower the ever-increasing youth suicide rate, medical settings are being leveraged as important partners in suicide prevention efforts [1]. Nearly 40% of youth had contact with a general healthcare provider weeks before their death, and 80% within a year of death [2]. Young people with medical illnesses, such as epilepsy, cancer, and asthma, are also at greater risk for suicide [3–5]. Notably, more than 93% of youth in the US had contact with a healthcare professional in 2018, positioning the medical setting as an ideal venue to identify even physically healthy youth during routine primary care visits [6]. In addition, depression in young people is highly prevalent [7], yet often goes undetected until they are adults [8]. Early detection of risk through mental health screening in non-behavioral healthcare settings may have positive effects on mental health outcomes in adulthood for these young people.

There has been a surge in depression screening in medical settings as a result of the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommending depression screening at healthcare visits for all youth ages 12 and above [9, 10]. In particular, the 9-item Patient Health Questionnaire – Adolescent Version (PHQ-A) is currently used by many hospitals across the country to screen for depression due to its robust psychometric properties and ability to accurately detect significant depressive symptoms [11].

Concurrently, many hospitals have implemented suicide risk screening to meet the 2016 Joint Commission Sentinel Event Alert 56 recommendations for universal screening of all medical patients [12]. Suicide risk screening has the potential to substantially reduce the frequency of individuals who pass through the medical system with unidentified suicide risk, allowing for those at risk for suicide to be detected and provided further mental health care [13, 14]. With many medical settings already using the PHQ-A as a depression screener, some use the PHQ-A to also detect suicide risk, though evidence to support this practice is limited. Although depression is a well-established risk factor for suicide, it is estimated that 20–60% of youth who die by suicide did not have clinically significant depression at the time of attempt [15]. Although screening for depression is important and necessary, depression screeners may not be adequate for identifying medical patients at risk for suicide.

The PHQ-A uses item nine as a proxy for detecting suicidal thoughts or self-harm by querying for feelings of being better off dead or hurting oneself. Research supporting use of this item to detect suicidal ideation is inconsistent. Some studies have shown that this item can identify large numbers of at-risk pediatric and adult patients [16, 17], but numerous other studies show that relying on this single item may fail to detect a large portion of individuals at risk for suicide [18–22]. Although previous research has shown depression screening may be inadequate for capturing medical patients at risk for suicide [21, 23], these studies primarily focus on adult populations. Therefore, the aim of this study is to determine if depression screening can accurately detect suicide risk in pediatric medical inpatients who screen positive on validated, suicide risk-specific measures.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Pediatric patients admitted to designated medical inpatient units at three large urban pediatric tertiary care hospitals were approached for participation in a larger instrument development study. To enroll, participants had to be admitted to one of the designated inpatient units, speak English, have an English-speaking parent/legal guardian (hereinafter referred to as “parent”) present (if 17 years old or younger), be between the ages of 10 and 21 years, and not have severe cognitive impairments based on clinician judgement. Exclusion criteria included: acute medical symptoms that precluded participation and presence of severe developmental delays, cognitive impairment, or communication disorder such that the patient was not able to comprehend questions or communicate their answers. The decision to exclude patients who did not speak English or did not have an English-speaking parents/guardians was due to several of the measures included in this study not being validated in languages other than English. This study was approved by the institutional review boards at each study site and the National Institute of Mental Health. Written informed consent was obtained from participants age 18 years and over and from parents of participants ages 17 and younger. Written assent was obtained from all participants under the age of 18 years.

After obtaining informed consent/assent, parents were asked to leave the patient’s treatment room during completion of the study materials, to ensure privacy. Participants were notified that their parent and medical team would be alerted if there were any safety concerns. Participants completed a battery of screening measures to assess suicide risk and depression, as well as a demographic questionnaire. Appropriate psychiatric follow-up care was provided for all participants deemed at risk for suicide and/or depression. Participant responses to study measures were evaluated by study staff in real time and all participants who screened positive on any measure received a follow-up brief suicide safety assessment by a clinician within 24-hours and patient safety was managed as clinically indicated and per standard of care for each institution [24]. Any participants who endorsed acute suicidal thoughts received an urgent, same-day psychiatric evaluation and standard of care safety measures, including a 1:1 safety observer.

Measures

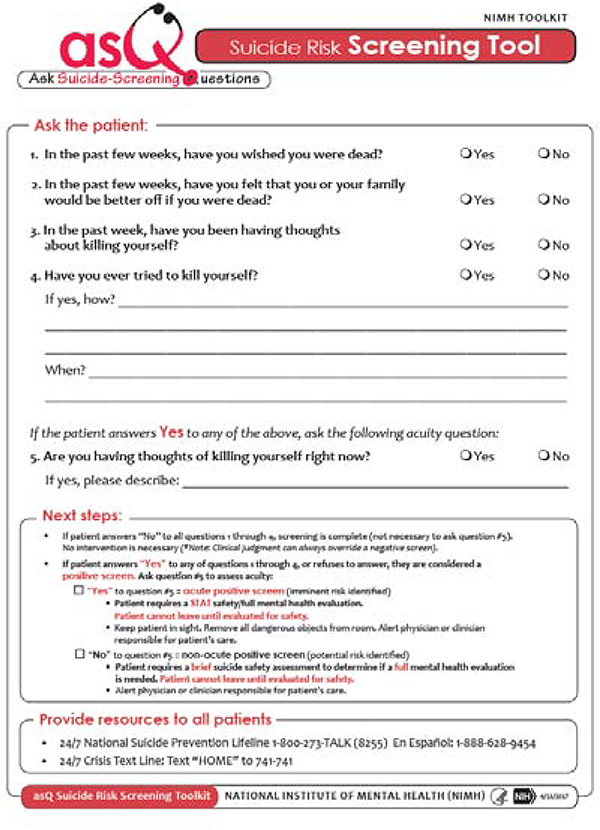

The Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) [25] is a 4-item brief screening questionnaire developed to assess recent suicidal ideation and lifetime suicidal behavior in pediatric medical patients (see Figure 1). All items use the response options of “yes” or “no.” Responding “no” to all items constituted a negative screen. A “yes” response or refusal to answer any question flagged the patient as a positive screen. Screening positive prompted a fifth question to assess acuity of suicidal thoughts. A “no” to the acuity question indicated a non-acute positive screen, while a “yes” response to the acuity item indicated an acute positive screen. The ASQ has strong psychometric properties among pediatric medical patients, with a sensitivity of 96.7%, a specificity of 91.1%, a negative predictive value of 99.8%, and a positive predictive value of 36.4% [24]. The ASQ has also been shown to have predictive validity for post-discharge suicidal behavior among pediatric emergency department patients [26].

Figure 1.

The Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ)

The Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire (SIQ/SIQ-JR) is a measure assessing the severity of suicidal ideation [27]. The 30-item SIQ was used for participants 15 years and above, while participants 14 years and younger were administered the 15-item SIQ-Junior (SIQ-JR). Both versions of the SIQ ask individuals to rate the frequency in which a given thought occurs on a 7-point Likert scale ranging from never to almost every day. The SIQ/SIQ-JR was included as the gold standard in the larger ASQ instrument validation study used for this sub-analysis and is included as an additional measure of suicide risk in the current sub-analysis. A score of 31 or higher on the SIQ-JR and 41 or higher on the SIQ is used to indicate clinically significant suicide risk and suggests a need for further assessment. For the purposes of this study, this cut off of 31 or greater on the SIQ-JR and 41 or higher on the SIQ was used to classify participants as positive for suicide risk. Participants with SIQ-JR scores lower than 31 or SIQ scores lower than 41 were considered negative for suicide risk on the SIQ. The SIQ has a high reliability (SIQ: r=0.97; SIQ-JR: r=0.94), validity, and predictive ability [27, 28].

The Patient Health Questionnaire – Adolescent Version (PHQ-A) [11] screens for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5) depressive symptoms over the past two weeks and is intended for use among adolescents. The 9-item version of the PHQ-A was used for the purposes of this study. Of note, item 9 of the PHQ-A asks specifically about “thoughts that you would be better off dead, or of hurting yourself in some way.” Individuals rate the frequency with which they experience each depressive symptom on a 4-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 1 = several days, 2 = more than half the days, 3 = nearly every day). A score of 11 or greater is considered clinically significant depression (moderate depression or above) and was used as the cut off score for a positive depression screen in this study. A score of 1 or greater for item 9 was considered endorsement of suicide risk for the purposes of this study. The PHQ-A has been shown to have a sensitivity of 75%, a specificity of 92%, and strong diagnostic agreement and accuracy for depression, as compared to a clinician interview [11].

Statistical Analysis

Univariate and multivariate statistics are reported to depict the relationship between screening positive for depression and screening positive for suicide risk. The results of an odds ratio with a 95% confidence interval are reported to describe the relationship between suicide risk and depression screening outcomes. A two-sample t-test was used to assess the difference between depression scores on the PHQ-A among individuals who screened positive for suicide risk compared to those who screened negative. Classification statistics of sensitivity and specificity, along with 95% confidence intervals were calculated to compare the performance of the PHQ-A item 9 in detecting suicide risk, relative to the gold standard SIQ/SIQ-JR. The decision was made to compare only item 9 of the PHQ-A to the SIQ/SIQ-JR as this item is intended to assess for suicide risk, whereas using the full PHQ-A is meant to identify depression. Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 25).

Results

Across the three study sites, 795 eligible pediatric medical inpatients were approached to participate in the larger study. Six hundred patients consented and completed the study measures, resulting in an enrollment rate of 75.5% (600/795). The sample was 59.2% female (355/600), 55.2% White (331/600), and had a mean age of 15.4 years (SD=2.8). Table 1 reports full demographics characteristics of the study participants.

Table 1.

Demographics of Study Participants (N =600)

| Gender | |

| Female | 355 (59.17%) |

| Male | 242 (40.33%) |

| Unknown | 3 (0.50%) |

| Race or ethnicity | |

| White | 331 (55.17%) |

| African American | 140 (23.33%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 59 (9.83%) |

| Asian | 10 (1.66%) |

| Multiple Races | 45 (7.5%) |

| Other | 11 (1.83%) |

| Unknown | 4 (0.66%) |

| Mean Age (SD) | 15.43 years (2.84) |

| 10–11 years | 55 (9.17%) |

| 12–17 years | 379 (63.17%) |

| 18–21 years | 163 (27.17%) |

| Unknown | 3 (0.50%) |

| Study Site | |

| BCH | 200 (33.33%) |

| CNMC | 200 (33.33%) |

| NCH | 200 (33.33%) |

BCH = Boston Children’s Hospital; CNMC = Children’s National Medical Center; NCH = Nationwide Children’s Hospital; SD = standard deviation

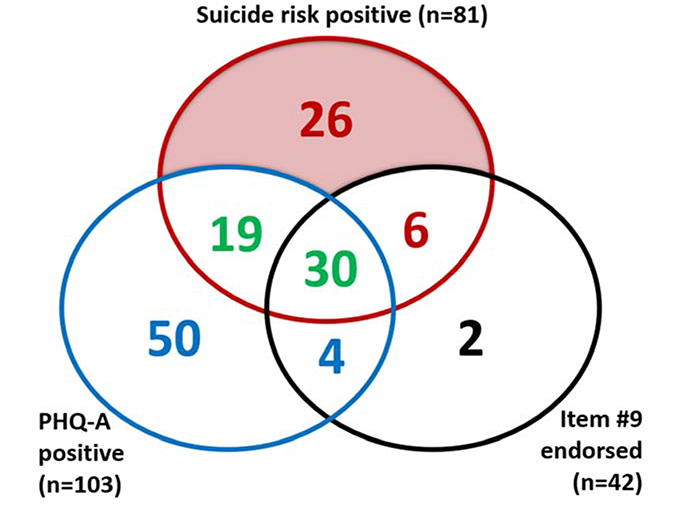

Eighty-one participants (13.5%; 81/600) screened positive for suicide risk on the ASQ and/or the SIQ/SIQ-JR. One hundred and three participants (17.2%; 103/600) screened positive for depression. Additionally, 42 participants (7.0%; 42/600) endorsed item 9 on the PHQ-A. A total of 137 participants (22.8%; 137/600) screened positive for depression and/or suicide risk. Figure 2 provides a visual representation of the relationship between positive screens for depression and suicide risk.

Figure 2.

Relationship Between Positive Screens for Depression and Suicide Risk

Almost 5% of participants (26/600) screened positive for suicide risk only, 9% of patients (54/600) screened positive for depression only, and 8.2% (49/600) screened positive for both depression and suicide risk. A total of 30 participants (5.0% 30/600) screened positive for all three conditions (depression, suicide risk, and endorsed item 9). A total of 42 patients endorsed item 9 on the PHQ-A, however two of them screened negative for depression and suicide risk (4.8%, 2/42).

Out of the 81 participants who screened positive for suicide risk, 39.5% (32/81) did not screen positive for depression, and 55.6% (45/81) did not endorse PHQ-A item 9. Of note, nearly one-third (32.1%; 26/81) of participants who were positive for suicide risk screened positive only on a suicide risk measure and were negative on the PHQ-A and did not endorse item 9 on the PHQ-A. Among the 26 participants who were at risk for suicide but did not screen positive for depression and did not endorse item 9, all 26 of them screened positive on the ASQ, specifically.

To further describe the relationships between suicide risk and depression in this sample, we assessed the association between suicide risk screening outcome and PHQ-A score. Participants who screened positive for depression were nearly 13 times more likely to screen positive for suicide risk compared to participants who screened negative for depression (OR: 12.9, 95% CI: 7.6 to 21.9, p <0.0001). Additionally, participants who screened positive for suicide had a mean PHQ-A score of 12.8 (SD = 6.2), while participants who screened negative had a mean PHQ-A score of 4.7 (SD = 4.1). Participants that screened positive for suicide risk had significantly higher PHQ-A scores compared to those who screened negative (t(597) = 14.9, p < .0001, d = 1.5).

Classification statistics were calculated to compare the performance of the PHQ-A item 9 in detecting suicide risk, relative to the gold standard SIQ. In relation to SIQ/SIQ-JR scores, item 9 had a sensitivity of 70% (95% CI = 51% to 85%) and a specificity of 96% (94% to 98%). Comparatively, in relation to the SIQ/SIQ-JR, the ASQ had a sensitivity of 97% (95% CI = 83% to 100%) and a specificity of 91% (95% CI = 88% to 93%) [24].

Discussion

These results indicate that depression screening alone is not enough to capture suicide risk in young patients. Despite the strong association between depression and suicide risk, the PHQ-A failed to identify a significant portion of medical patients at risk for suicide. A salient finding of the current study was that solely relying on depression screening would have missed 32% of the participants at risk for suicide. Using the ASQ alone as a measure of suicide risk, even without the SIQ/SIQ-JR as an additional suicide risk detection measure, the ASQ was able to detect all participants who were missed by depression screening. Consequently, hospitals that only use depression screening tools, such as the PHQ-A, to detect suicide risk may miss a fair number of youth at risk for suicide that would have been detected had suicide risk specific measure been utilized.

Item 9 of the PHQ-A is often considered to be a proxy for self-injury and suicide ideation, yet more than half (56%) of the participants who screened positive for suicide risk did not endorse item 9. Additionally, in a direct comparison of item 9 of the PHQ-A to the SIQ/SIQ-JR, item 9 had a less than optimal sensitivity of 70%, yet a high specificity (96%), compared to the ASQ which had high sensitivity (97%) and specificity (91%). Using the SIQ as the criterion standard, these results suggest that the PHQ-9 may be inadequate for screening for suicide risk. Although depression and suicide often co-occur [29, 30], the current findings demonstrate that this may not always be the case, particularly in medical patients. For instance, past research by Recklitis and colleagues showed that out of 29 cancer patients at risk for suicide, only 11 met criteria for depression [23]. Future research should seek to better characterize young medical patients who screen positive for suicide risk but not depression. In addition, while it is tempting to assume that these data obtained from an inpatient medical surgical unit apply to all medical settings, replication of these findings is needed in other venues where children are frequently seen, like primary care settings.

Interestingly, two participants endorsed item 9 on the PHQ-A but did not screen positive for suicide risk nor depression. The item reads: “Thoughts that you would be better off dead, OR of hurting yourself in some way.” One main problem with utilizing item 9 as a suicide risk detection measure is that the question includes an “or” in the middle of the sentence. When a responder endorses this item, it is unclear if they are responding to the first or second part of the question. In addition, the item uses the term “hurting” instead of “killing.” Therefore, it is possible that these participants were responding “yes” due to non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) rather than a suicidal component of the question. Most patients do not disclose suicidal thoughts or plans unless they are asked directly about suicidal thoughts. Moreover, numerous studies have demonstrated that thoughts of NSSI and suicide are distinct [31–34]. Therefore, the best way to detect suicide risk among youth is to ask directly about suicide [35, 36].

Depression screening remains an essential component of mental wellness screening to detect depressive symptoms that warrant further mental health evaluation, with or without the presence of suicide risk [10]. Multi-step screening processes for depression and suicide risk are sometimes implemented whereby the PHQ-2 is utilized as a primary screen, then if positive, the PHQ-9 is administered, followed by a suicide risk screen, if the PHQ-9 is positive. While this practice is becoming more common, there is no empirical evidence to support this sequential manner of screening and most likely patients will find it tedious [37]. Thus, clinicians should assess both depression and suicide risk and utilize the best currently evidenced-based tools for both.

While there are not yet youth studies establishing that screening for suicide risk reduces suicide or suicide attempts, the ED-SAFE study of adult ED patients, did establish that screening paired with a brief intervention reduced suicidal behavior by 20% [38]. The ASQ is only the first step in a longer clinical pathway to reduce suicide and suicidal behavior [39]. Moreover, there is now evidence that the ASQ can predict future suicidal behavior [26].

The study findings should be interpreted with the following limitations in mind. First, each of the three study sites were in urban, academic hospitals. The study budget did not allow participation from families of non-English speakers thereby limiting generalizability. The use of one screening tool across individuals of all cultures may also limit generalizability, suggesting a need for future research studies to replicate current findings and validate depression and suicide risk screening tools across cultures. Second, use of a convenience sample may introduce selection bias into the findings and we were unable to obtain demographic information on the patients who declined to participate. Finally, as this study was cross-sectional in nature, no longitudinal data were collected, preventing assessment of any temporal relationship between the screens and the outcomes of interest.

Mental health concerns in young people are increasingly prevalent. Depression and suicide risk are highly related but are not equivalent. Importantly, they both lend themselves to early detection and intervention, but depression screening alone is not enough. Relying solely on depression screens to detect suicide risk among pediatric patients may fail to identify a significant number of medical patients at risk for suicide. Clinicians should screen for suicide risk with validated tools that ask youth directly about suicide to ensure that young people at risk do not pass through medical settings undetected.

Implications and Contribution summary statement:

Depression screening failed to detect a significant portion of pediatric medical patients with suicide risk. Medical settings that are seeking to identify youth at risk for suicide should use suicide-specific screening tools to ensure that patients at risk for suicide do not pass through the healthcare system undetected.

Acknowledgements:

The authors would like to thank all the patients, nurses, mental health and medical teams for their participation. The authors would also like to acknowledge and thank the following people who were instrumental to the success of the study, including Sandra McBee-Strayer, Paramjit Joshi, Stephen J. Teach, Martine Solages, Sandra Rackley, Michael Lotke, Jichuan Wang, Adelaide Robb, Laura Nicholson, Nadirah Waites, Nicole Hedrick, Kerry Brodziak, Mariam Gregorian, Emory Bergdoll, Elizabeth Ballard, Deborah Snyder, Kathleen Merikangas, Mary Tipton, Jeanne Radcliffe, Ian Stanley, Julian Lantry, William Booker, Michael Schoenbaum, Jarrod Smith, Cristan Farmer, Sally Nelson, and Patricia Ibeziako. The views expressed in this abstract are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the National Institute of Mental Health, National Institutes of Health, or the Department of Health and Human Services.

Funding Source: This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIMH (Annual Report Number ZIAMH002922). This research was also supported in part by the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System (WISQARS). Accessed 2020 Oct 7.

- 2.Ahmedani BK, Simon GE, Stewart C, et al. Health care contacts in the year before suicide death. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(6):870–877. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2767-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuo CJ, Chen VC, Lee WC, et al. Asthma and suicide mortality in young people: a 12-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(9):1092–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thibault DP, Mendizabal A, Abend NS, et al. Hospital care for mental health and substance abuse in children with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;57:161–6. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nathan PC, Nachman A, Sutradhar R, et al. Adverse mental health outcomes in a population-based cohort of survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2018;124(9):2045–2057. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Summary Health Statistics: National Health Interview Survey, 2018. Available at: https://ftp.cdc.gov/pub/Health_Statistics/NCHS/NHIS/SHS/2018_SHS_Table_C-8.pdf. Accessed 2020 Dec 1.

- 7.Ghandour RM, Sherman LJ, Vladutiu CJ, et al. Prevalence and Treatment of Depression, Anxiety, and Conduct Problems in US Children. J Pediatr. 2019;206:256–267.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, & Ries Merikangas K (2001). Mood disorders in children and adolescents: an epidemiologic perspective. Biological psychiatry, 49(12), 1002–1014. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01129-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Siu AL, & US Preventive Services Task Force (2016). Screening for Depression in Children and Adolescents: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Pediatrics, 137(3), e20154467. 10.1542/peds.2015-4467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zuckerbrot RA, Cheung A, Jensen PS, Stein REK, Laraque D. Guidelines for Adolescent Depression in Primary Care (GLAD-PC): Part I. Practice Preparation, Identification, Assessment, and Initial Management. Pediatrics. 2018;141(3). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johnson JG, Harris ES, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The patient health questionnaire for adolescents: validation of an instrument for the assessment of mental disorders among adolescent primary care patients. J Adolesc Health. 2002;30(3):196–204. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00333-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Joint Commission. Detecting and treating suicide ideation in all settings. 2016. Available at: https://www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/SEA_56_Suicide.pdf. Accessed 2020 Oct 7.

- 13.Horowitz LM, Bridge JA, Pao M, Boudreaux ED. Screening youth for suicide risk in medical settings: time to ask questions. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(3 Suppl 2);S170–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Horowitz LM, Roaten K, Pao M, Bridge JA. Suicide prevention in medical settings: The case for universal screening. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;63:7–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2018.11.009. Epub 2018 Dec 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cash SJ, Bridge JA. Epidemiology of youth suicide and suicidal behavior. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21(5):613–619. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32833063e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simon GE, Shortreed SM, Johnson E, et al. Between-visit changes in suicidal ideation and risk of subsequent suicide attempt. Depress Anxiety. 2017;34(9):794–800. doi: 10.1002/da.22623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simon GE, Rutter CM, Peterson D, et al. Does response on the PHQ-9 Depression Questionnaire predict subsequent suicide attempt or suicide death?. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(12):1195–1202. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201200587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Louzon SA, Bossarte R, McCarthy JF, Katz IR. Does suicidal ideation as measured by the PHQ-9 predict suicide among VA patients? Psychiatr Serv. 2016;67(5):517–522. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201500149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simon GE, Coleman KJ, Rossom RC, et al. Risk of suicide attempt and suicide death following completion of the Patient Health Questionnaire depression module in community practice. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(2):221–227. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15m09776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Corson K, Gerrity MS, Dobscha SK. Screening for depression and suicidality in a VA primary care setting: 2 items are better than 1 item. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt 2):839–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker J, Hansen CH, Butcher I, et al. Thoughts of death and suicide reported by cancer patients who endorsed the “suicidal thoughts” item of the PHQ-9 during routine screening for depression. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(5):424–427. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2011.02.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dueweke AR, Marin MS, Sparkman DJ, Bridges AJ. Inadequacy of the PHQ-2 depression screener for identifying suicidal primary care patients. Fam Syst Health. 2018;36(3):281–288. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Recklitis CJ, Lockwood RA, Rothwell MA, Diller LR. Suicidal ideation and attempts in adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(24):3852–3857. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.5409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Horowitz LM, Wharff EA, Mournet AM, et al. Validation and feasibility of the ASQ among pediatric medical and surgical inpatients. Hosp Pediatr. 2020;10(9):750–757. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2020-0087 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horowitz LM, Bridge JA, Teach SJ, et al. Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ): a brief instrument for the pediatric emergency department. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(12):1170–1176. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2012.1276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeVylder JE, Ryan TC, Cwik M, et al. Assessment of selective and universal screening for suicide risk in a pediatric emergency department. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(10):e1914070. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.14070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reynolds WM. Suicidal ideation questionnaire (SIQ). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Keane EM, Dick RW, Bechtold DW, Manson SM. Predictive and concurrent validity of the Suicidal Ideation Questionnaire among American Indian adolescents. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1996;24(6):735–747. doi: 10.1007/BF01664737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bachmann S Epidemiology of Suicide and the Psychiatric Perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(7):1425. Published 2018 Jul 6. doi: 10.3390/ijerph15071425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harris EC, Barraclough B. Suicide as an outcome for mental disorders. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:205–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brausch AM, Gutierrez PM. Differences in non-suicidal self-injury and suicide attempts in adolescents. J Youth Adolesc. 2010;39(3):233–42. doi: 10.1007/s10964-009-9482-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Claes L, Muehlenkamp J, Vandereycken W, et al. Comparison of non-suicidal self-injurious behavior and suicide attempts in patients admitted to a psychiatric crisis unit. Pers Individ Differ. 2010; 48:83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2009.09.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muehlenkamp JJ, Gutierrez PM. An investigation of differences between self-injurious behavior and suicide attempts in a sample of adolescents. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2004;34(1):12–23. doi: 10.1521/suli.34.1.12.27769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muehlenkamp JJ, Gutierrez PM. Risk for suicide attempts among adolescents who engage in non-suicidal self-injury. Arch Suicide Res. 2007;11(1):69–82. doi: 10.1080/13811110600992902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gould MS, Marrocco FA, Kleinman M, et al. Evaluating iatrogenic risk of youth suicide screening programs: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293(13):1635–43. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.13.1635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pan YJ, Lee MB, Chiang HC, Liao SC. The recognition of diagnosable psychiatric disorders in suicide cases’ last medical contacts. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31(2):181–184. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Horowitz L, Tipton MV, Pao M. Primary and Secondary Prevention of Youth Suicide. Pediatrics. 2020;145(Suppl 2):S195–S203. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-2056H [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller IW, Camargo CA Jr, Arias SA, et al. Suicide prevention in an emergency department population: The ED-SAFE Study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):563–570. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brahmbhatt K, Kurtz BP, Afzal KI, et al. Suicide risk screening in pediatric hospitals: Clinical pathways to address a global health crisis. Psychosomatics. 2019;60(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2018.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]